Articles

Lycopsida from the lower Westphalian (Middle Pennsylvanian) of the Maritime Provinces, Canada

ABSTRACT

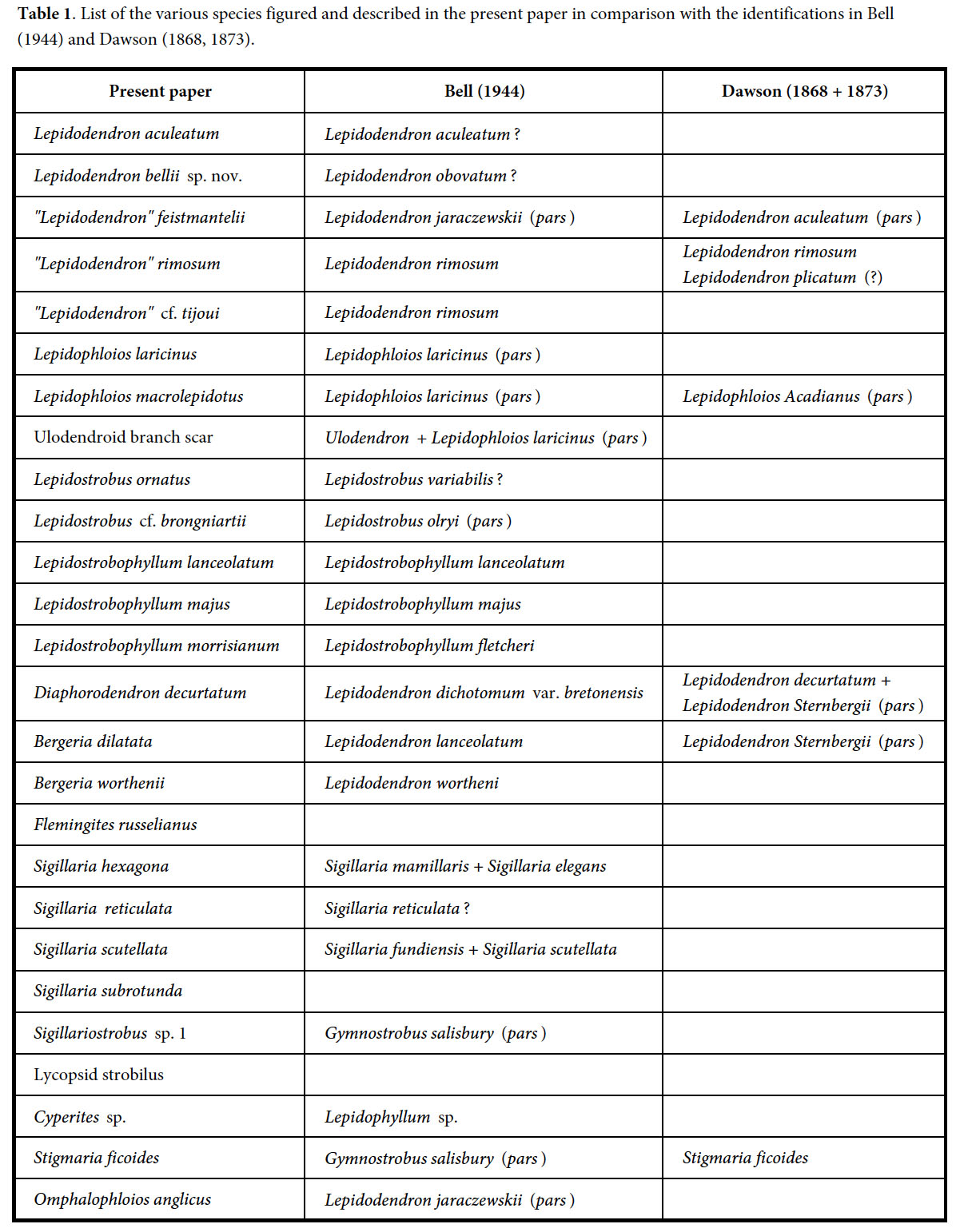

A taxonomic revision of lycopsids is presented as part of a reassesment of lower to middle Westphalian adpression floras from the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Being elements of the swamp flora their record reflects sedimentary bias. Systematic collecting from the “Fern Ledges” at Saint John (New Brunswick) has yielded only a few lycopsid remains as a result of the allochthonous facies. Most records (mainly by W.A. Bell in the twentieth century) correspond to sporadic collecting by Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) personnel. Their specimens are kept in GSC Ottawa. Additional remains are in museums at Montréal (Quebec), Joggins (Nova Scotia) and Saint John (New Brunswick). We introduce a new species (Lepidodendron bellii), and reinstate another (Diaphorodendron decurtatum) described by Dawson in the 19th century. Altogether, 26 taxa are described, including stem and branch remains as well as roots, leaves, strobili and sporophylls. Three specimens are illustrated from localities outside Canada so as to clarify specific characters. A copy of Lindley and Hutton’s illustration of the type of Lepidodendron dilatatum (here recorded as Bergeria dilatata) is figured in the context of a redefinition of the genus Bergeria for stem remains with false leaf scars. Problems surrounding the morphological interpretation of arborescent lycopsids of Pennsylvanian age are discussed, and the stratigraphic and paleogeographic distribution are recorded for the different taxa. The identity of the Pennsylvanian flora of the Canadian Maritimes with that of the British Isles and western Europe in general is emphasized by the synonymies discussed. Paleogeographic proximity and a similar paleolatitude justify the identity of floras.

RÉSUMÉ

Une révision taxonomique des lycopsides est présentée dans le cadre d’une réévaluation des compressions- impressions des flores du Westphalien inférieur et moyen des Provinces maritimes canadiennes. Comme membres de la flore marécageuse, leur enregistrement est conditionné par l’environnement. Le prélèvement systématique dans les « Fern Ledges » à Saint John (Nouveau-Brunswick) n’a permis que récupérer des quelques fragments indeterminables de lycopsides en raison du faciès allochtone. La plupart des enregistrements (principalement par W. A. Bell au XXe siècle) correspondent au prélèvement sporadique effectué par le personnel de la Commission géologique du Canada (CGC). Leurs spécimens sont conservés à CGC-Ottawa. Les autres échantillons sont dans des musées à Montréal (Québec), à Joggins (Nouvelle-Écosse) et à Saint John (Nouveau-Brunswick). Nous introduisons une nouvelle espèce (Lepidodendron bellii) et nous revalidons une autre (Diaphorodendron decurtatum) décrite par Dawson au XIXe siècle. En tout, 26 taxons sont décrits, y compris des échantillons de tige et de branche, de même que les racines, les feuilles, les strobiles et les sporophylles. Trois spécimens de localités situées hors du Canada sont illustrés dans le but de clarifier leurs caractéristiques spécifiques. Une copie de l’illustration de Lindley et Hutton du type de Lepidodendron dilatatum (ici répertorié sous le nom de Bergeria dilatata) est incluse dans le contexte d’une redéfinition du genre Bergeria pour des tiges présentant de fausses cicatrices foliaires. Les problèmes entourant l’interprétation morphologique des lycopsides arborescents du Pennsylvanien sont analysés, et les distributions stratigraphiques et paléogéographiques sont enregistrées pour les différents taxons. Il est mise en évidence que la flore pennsylvanienne des Provinces maritimes canadiennes est identique avec celle des Îles Britanniques et de l’Europe occidentale en général et les listes de synonymie en sont le témoin. La proximité paléogéographique et une paléolatitude similaire justifient l’identité entre les flores.

[Traduit par la redaction]

INTRODUCTION

1 This paper forms part of a series of taxonomic revisions of upper Namurian and, more particularly, lower Westphalian floras of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. This study was undertaken with the active support of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) and the New Brunswick Museum, as well as other institutions in Nova Scotia. John Utting of the GSC was the prime mover to effect this revision, which should lead to a synthesis of paleobotanical and palynological data for the stratigraphy and paleogeography of the Pennsylvanian in eastern Canada. Geologically, the material is from the so-called Maritimes Basin, an entity which has been subject to structural controls of various kinds, leading to separate areas of downwarp that may be regarded as subsidiary basins, an example of which is the Cumberland Basin. Although a paper dealing with a taxonomic revision of part of the flora is not the place to go into geological detail, it is useful to observe that the Pennsylvanian floras of the Maritime Provinces of Canada compare most closely with those of the British Isles, a fact recognized by previous authors such as M.C. Stopes and W.A. Bell. Thus, Nova Scotia, linked to Newfoundland, may have been in continuity with the Midland Valley and the adjacent Southern Uplands of Scotland, a possibility important in a floral context and to be discussed in a later, more general paper. Our revisions commenced with a paper on extrabasinal floral elements (Wagner 2001) and was continued in Wagner (2005a, b), Wagner (2008) and Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2008).

2 Most of the present paper, the largest contribution to date in the series of revisions, involves material described by Walter A. Bell in the early part of the twentieth century. In order to place Bell’s work in its proper perspective, the enormous range of his investigations is noted not only with regard to the time intervals covered, but also the number of fossil floras and faunas recorded and the stratigraphic conclusions that were drawn. In this context, it is understandable that an in-depth revision of fossil identifications reveals gaps in the consideration of taxa and the consequent introduction of unneccesary species. This may be ascribed in part to incomplete consultation of the literature in German and French. Wartime conditions may have been partly responsible by cutting his links with continental Europe.

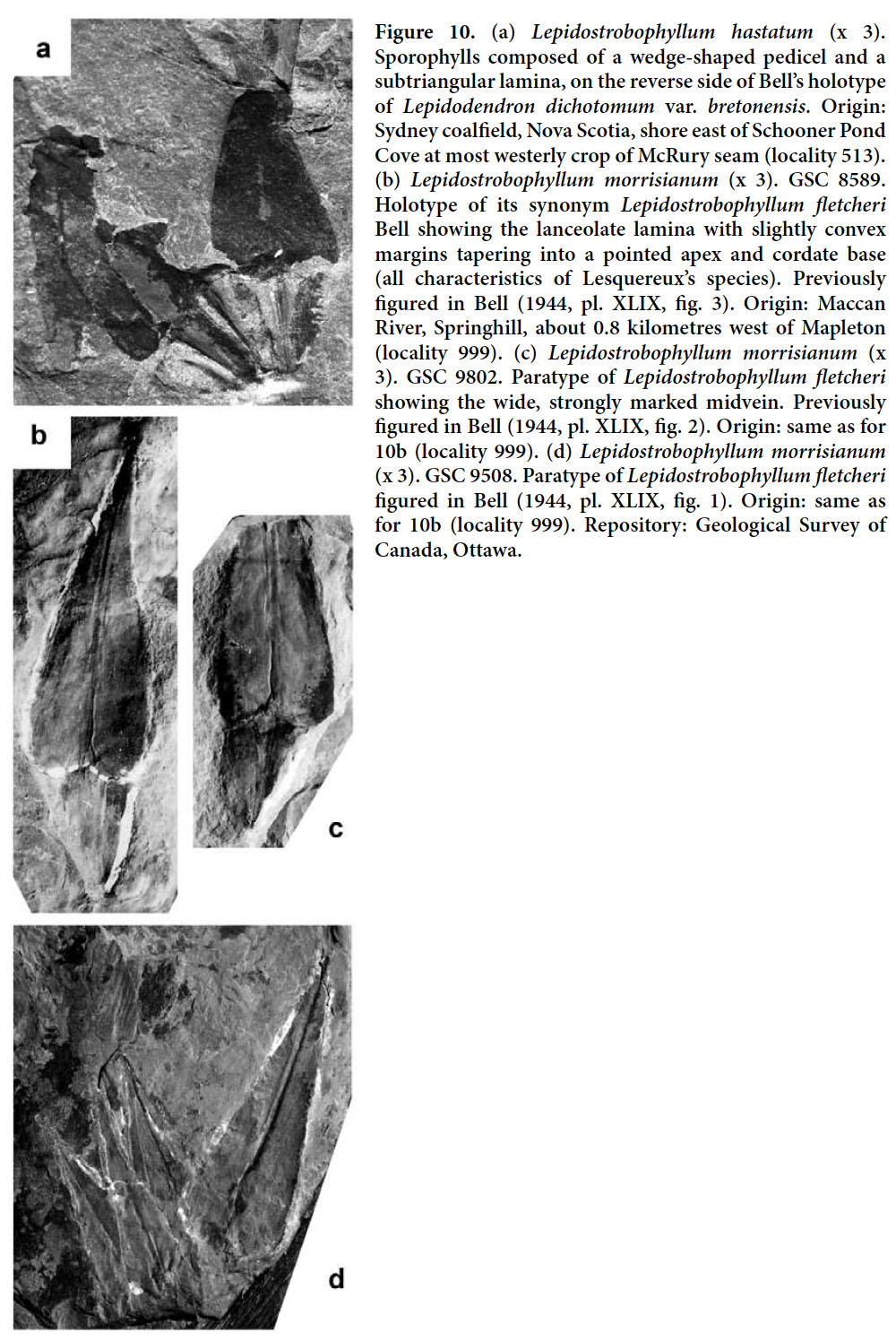

3 The Cumberland Basin in Nova Scotia includes the world-famous Joggins section on Chignecto Bay, an inner arm of the Bay of Fundy. This section has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO (Calder 2007, 2009). Early work at Joggins includes that of Dawson (1868), who also described a number of fossil plant species from the Fern Ledges locality at Saint John, New Brunswick, on the northwestern side of the Bay of Fundy. The Fern Ledges flora was redescribed by Stopes (1914), and the Cumberland Basin flora was recorded in a memoir by Bell (1944), supplemented by selected illustrations in Bell (1966). In 1940, Bell also reported on material from the Pictou coalfield, representing deposits in the Stellarton Basin, a small pull-apart basin in northern Nova Scotia. The present revision is restricted almost entirely to material from the lower Westphalian of the Cumberland Basin, with occasional specimens from the Stellarton Basin. No material from Saint John is included in the present paper as lycopsid remains are virtually absent from Fern Ledges. Stopes (1914) commented on the few scraps of lycopsid leaves and decorticated branch and stem fragments, which she correctly regarded as indeterminable. She figured a fragment recorded previously as Sigillaria palpebra (Dawson 1862), calling it Sigillaria sp. (indeterminable) (Stopes 1914, pl. V, fig. 8). We concur with its designation as “indeterminable”. The plant fragments preserved at Fern Ledges are drifted remains that include a large proportion of comminuted plant debris. Falcon-Lang and Miller (2007) also mention rooted vegetation, but their description of plants in growth position (p. 952) conflicts with personal observation by one of the present writers (RHW) and with an examination of a rock specimen that was kindly made available by Dr R.F. Miller. The fact that the Fern Ledges material represents an allochthonous assemblage explains the virtual absence of lycopsid remains, as well as the poor preservation of the few (drifted) specimens recorded.

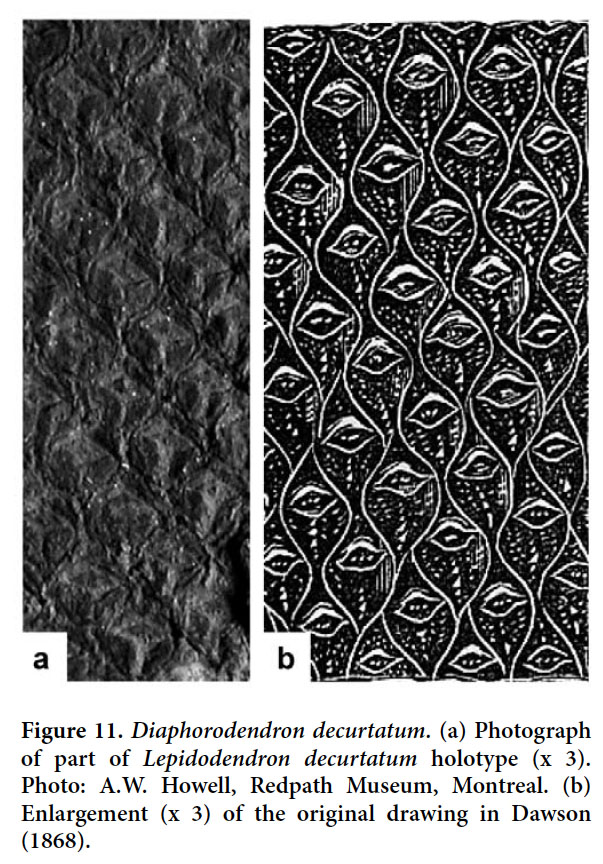

4 Bell (1944) distinguished Riversdale and Cumberland groups, but recent authors have incorporated Riversdale strata in the Mabou Group. Several formations are now recognized in the Joggins section, which is the principal area of outcrop in the Cumberland Basin (Gibling et al. 2008). These can be dated on plant megafossils as ranging from possible Yeadonian to possible Bolsovian, but most of this classic section corresponds to the Langsettian according to the present authors and subject to consultation with palynological colleagues. Coal workings in Nova Scotia provided a large number of the plant megafossils of Langsettian age in the collections of the Geological Survey of Canada in Ottawa. We have had access to this collection, which includes all the material recorded by Bell (1944, 1966) as well as some additional specimens that were unrecorded by Bell. The Dawson Collection at the Redpath Museum, McGill University, Montreal, has been examined as well, albeit more succinctly.

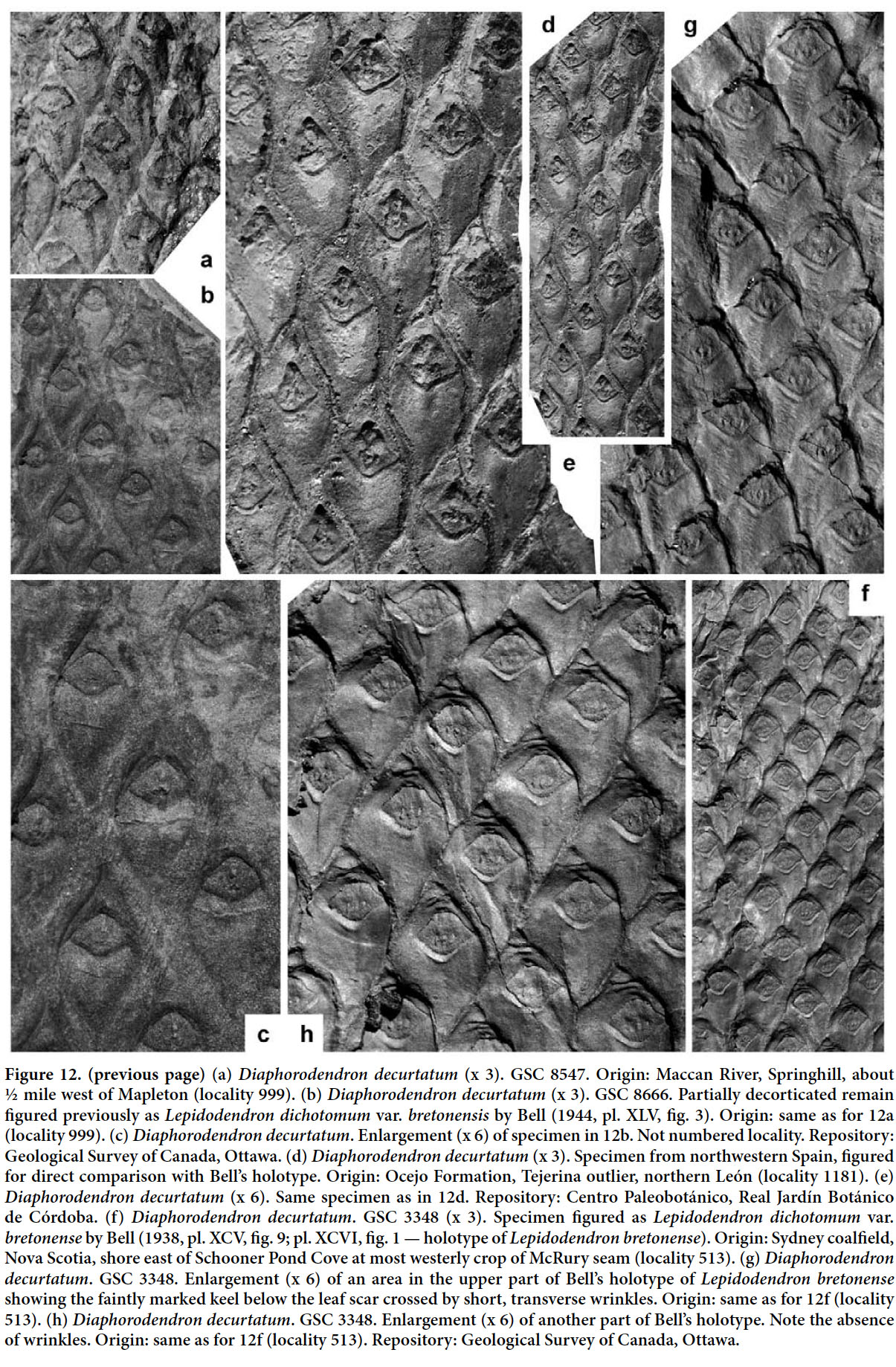

5 In the present paper, all the lycopsid taxa previously described from the Cumberland and Stellarton basins are revised, thus facilitating a full comparison with the same taxa in western Europe. A few lower Westphalian lycopsid remains from western Spain are figured for comparison in cases where the Canadian material is too poorly preserved or very fragmentary. Walter Bell was keenly aware of the close similarity of Carboniferous plant taxa from the Maritimes with those of western Europe, especially the British Isles. The Carboniferous floras of Great Britain have been documented comprehensively by Kidston (e.g., 1893, 1903, 1916) and Crookall (1964, 1966). Bell seemed less familiar with the paleobotanical literature in French and German, a factor that may have imposed limitations on his identifications. Although Bell collected many specimens himself, most of the material he recorded was collected during field mapping by other geologists. Inevitably, this resulted in more sporadic records and, often, fragmentary remains. There is little evidence from Bell’s work of large-scale collecting from single localities. Assiduous collecting from the Joggins shore by Donald Reid has yielded some of the lycopsid remains recorded in the present paper.

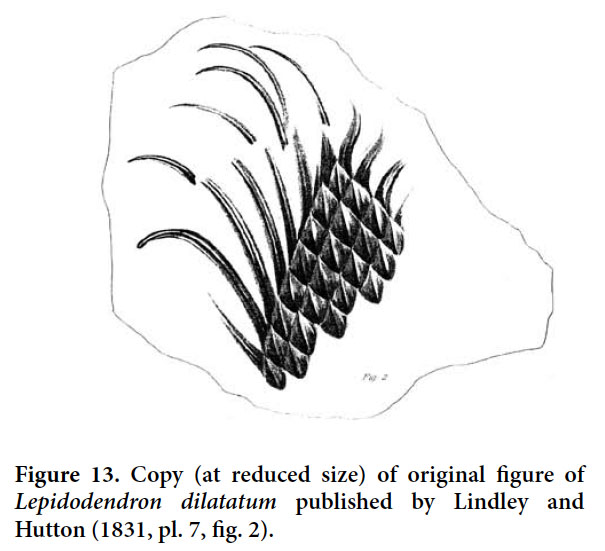

6 The lycopsids are generally regarded as swamp elements adapted to a high water table and, in a few cases, some degree of salinity. With a few exceptions, their biostratigraphic value seems limited. This may be due to evolutionary conservatism as well as the limited range of morphological characters preserved in impression floras.

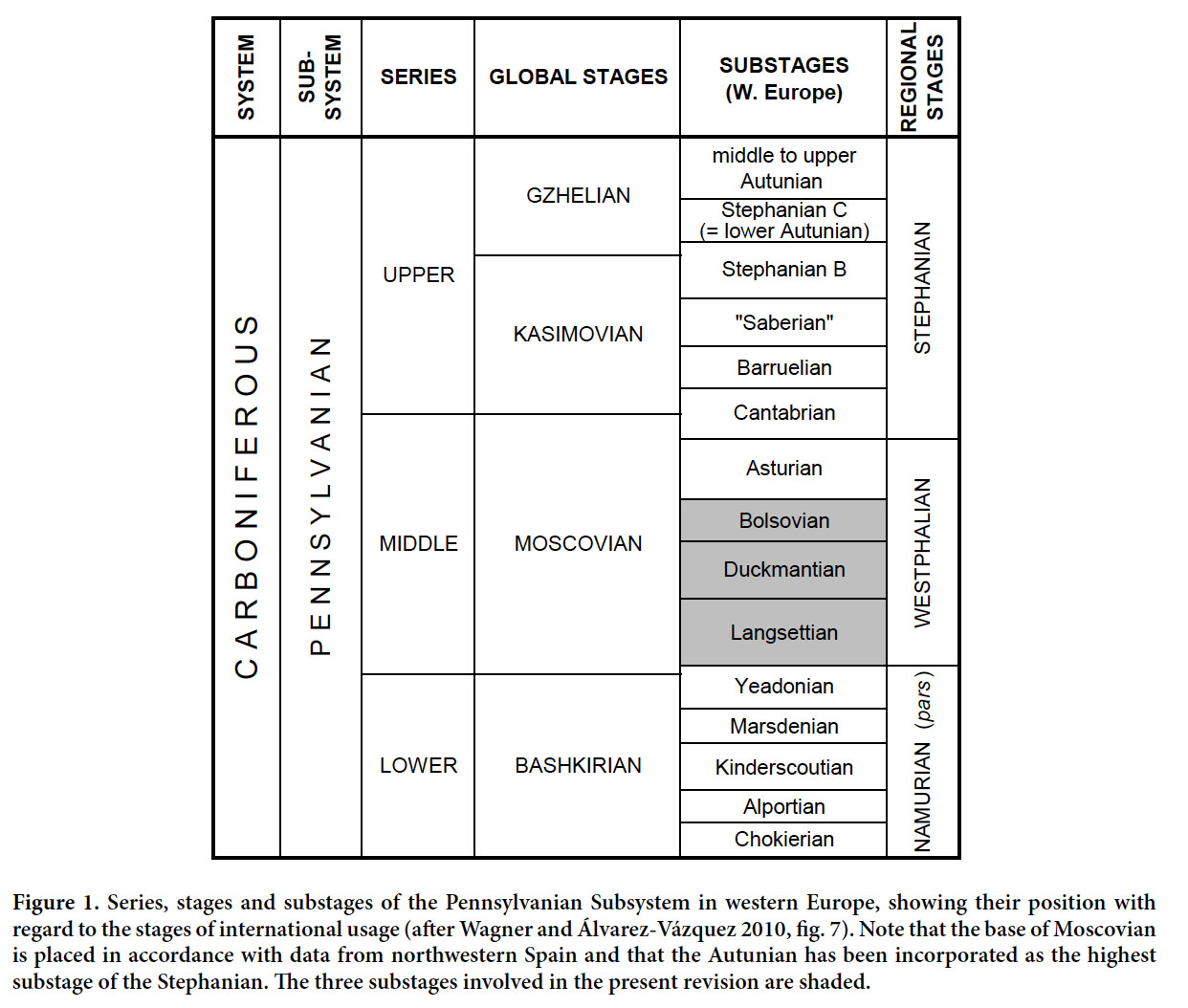

7 Stratigraphic occurrences are given in accordance with the western European regional chronostratigraphic subdivisions of the Pennsylvanian Subsystem (Fig. 1). Mention of international stages linked to eastern European marine records is avoided due to discrepancies in the correlation with the western European regional scale.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1LATE CARBONIFEROUS (PENNSYLVANIAN) ARBORESCENT LYCOPSIDS: A GENERAL COMMENTARY

8 The remains of large, arborescent lycopsids in coal-bearing deposits of Pennsylvanian age have generally fascinated paleobotanists and coal geologists. The predominant role of lycopsids in coal formation is generally acknowledged (e.g., DiMichele and Phillips 1985), and is particularly obvious from palynological data (e.g., Peppers 1996). Large external impressions of lycopsid trees caught the eye of the early paleobotanists, particularly those connected with coal mining (e.g., Graf Kaspar von Sternberg, whose last resting place, near Radnice in Bohemia, is adorned by a superb specimen of Lepidodendron aculeatum). The internal anatomy of these plants was studied later, when coal balls were collected. The different kinds of preservation, primarily of external morphology versus anatomical detail, gave rise to a parallel taxonomic treatments, which has been integrated only to a certain extent (e.g., DiMichele 1983) because of the incomplete overlap of characters.

9 The reconstruction of lycopsid trees has been problematical. Stem impressions only rarely have leaves attached, whereas leaves are common on the remains of smaller branches. Thus, older reconstructions by Hirmer (1927), Eggert (1961), as well as more recent ones (e.g., Opluštil 2010), show stems devoid of leaves, while the upper parts of trees, profusely branched or not, are depicted with single-veined leaves of various lengths and densities of arrangement. The general assumption has been that lycopsids would have shed leaves from the lower part of the trees as they grew, their former presence being shown by leaf scars on protruding parts of the leaf cushions. However, this assumption needs to be questioned in several cases, if not generally. Lycopsids are characterized by a wide area of cortical tissue surrounded by a thick-walled periderm. These trees had only a very small wood cylinder. When trees fell, this overall structure resulted in tissue collapse and flattening of trunks before entombment, processes that may have taken place quite quickly. Indeed, it is common to find totally flattened remains of lycopsid tree trunks, the imprints of both sides separated by only a few millimetres of sediment, with or without a coaly substance representing the collapsed tissue. In the case of sizeable stem and branch remains, the only possibility of finding clearly attached leaves preserved as adpressions is on the margins of the flattened remains (even though careful preparation may also reveal the presence of attached leaves below, in a position external to the compression). The larger the original stem or branch diameter, the less likely it becomes to actually find such margins preserved, taking into account that the remains are always fragmentary. Indeed, flattened slabs of large tree trunk impressions generally show only leaf scars, not the actual leaves. Recognition of this preservational character is important, because it means that the apparent absence of leaves from major stem remains does not necessarily mean their absence before fossilization. The discovery of occasional larger specimens with attached leaves confirms the validity of this statement. There is also no apparent reason why these trees, living in a tropical swamp environment should have had a caducous habit. This does not mean, of course, that some of the larger trees would not have shed their leaves in the lower part of the more sizeable tree trunks. W.A. DiMichele (personal communication 2013) makes a clear distinction between certain groups (including Omphalophloios, Polysporia, Paralycopodites = Bergeria) with permanent leaves and others (including Diaphorodendron, Sigillaria) that may have shed their leaves during their lifetime. This distinction may be a valid one, and the evidence should be carefully examined for each particular case. We merely point out that the reconstructions showing large tree trunks devoid of leaves except for a small area in the top of the tree may have to be reconsidered in the light of taphonomic processes and preservational aspects. Coal ball material is not free from these considerations. However, we are not able to contribute to a solution of these problems because the material is subject to the usual preservational restrictions.

10 Another problem lies in the reconstruction of the shape and size of lycopsid trees. Virtually unbranched trees, such as Sigillaria and Omphalophloios, show a columnar shape — a broadly rounded stem apex and a stem diameter that remains more or less the same throughout. However, more conical shapes have also been observed for monopodial lycopsid trees. A different situation exists for lycopsid trees with profusely branched crowns, as in many lepidodendrids, Bothrodendron and Lepidophloios. How tall were these trees? Their mechanical strength may have been quite limited, and reconstructions of 30 to 35 m tall trees as for Diaphorodendron and Synchysidendron (see DiMichele and Bateman 1992) may be excessive, although these heights were inspired by the trunks up to 21.5 m long recorded by Wnuk (1985). The tree trunks figured by Wnuk show lateral branches produced by anisotomous forking. A similar structure is also suggested by the holotype of Lepidodendron dichotomum (refigured as Lepidodendron mannebachense by Opluštil 2010, fig. 5). Wnuk (1985) postulated that trees up to 40 to 45 m tall might have been present. Several different kinds of branching may have occurred, including the strictly dichotomous branching of the terminal parts of profusely branched Lepidodendron trees, as depicted in the reconstruction by Hirmer (1927, fig. 200). Recent evidence has revealed the presence of deciduous lateral branches in Synchysidendron (DiMichele et al. 2013) and perhaps in the Diaphorodendraceae in general, showing a richness of variety in lycopsid branching systems that have not always been acknowledged.

11 The constitution of lycopsid forests is another issue. Wnuk (1985) assumed the intermingling of different kinds of lycopsid tree. Indeed, he speculated on different canopy heights for forests containing different well-branched lycopsid trees. On the other hand, DiMichele and DeMaris (1987) found that a lycopsid forest as represented by standing and fallen tree trunks belonging, most likely, to a single species, Lepidodendron hickii, and occurring in roof shales of the Herrin (nº 6) coal seam in Illinois, apparently represented a monospecific association of nearly even-aged individuals. Monospecific stands may reflect an ecological dependence. The nature of the geological record plays an important role. Wnuk (1985) investigated an assemblage of drifted plant remains of diverse provenance. The assumption that all these plants lived in close proximity thus cannot be taken for granted. An assemblage of in-situ tree stumps providing contradictory evidence was recorded by DiMichele and DeMaris (1987). Similarly, Wagner and Diez (2007) and Wagner et al. (2012) described a large sandstone surface with the imprints of Sigillaria-tree bases at a lower Cantabrian locality in northwestern Spain that shows the colonization of a single kind of tree with two successive generations. An adjacent forest of a woody tree (Cordaites) at the same locality shows a separate development of trees with little intermingling at the border between the different stands. It is possible that the absence of the remains of smaller plants (undergrowth, lianas) at this locality may have been the result of catastrophic flooding, removing part of the floral association; but this is conjectural. In contrast, Opluštil et al. (2009) recorded a considerable diversity of floral elements in volcanic-ash deposits associated with the Radnice coals of Bolsovian age in the Czech Republic. They distinguished canopy, understorey, lianas and ground cover/climbers. Although volcanic-ash fall guarantees instant burial, it is not clear to what extent these assemblages were in situ and not subjected to transport and intermingling prior to burial. The data presented by DiMichele and DeMaris (1987) and Wagner et al. (2012) suggest that separate stands of trees were subjected to different environmental conditions. Ecological control on the presence of different kinds of arborescent lycopsids is also suggested by the link between Omphalophloios and brackish conditions (Wagner et al. 2003).

12 In-situ lycopsid trees have been recorded commonly (DiMichele and Falcon-Lang 2011), although perhaps not as commonly as might be expected in view of the frequent occurrence of casts of standing trees in cliff faces (e.g., Lyell and Dawson 1853; Scott and Calder 1994; Calder et al. 1996), quarries, and opencast sites. In every case it appears that only one kind of tree is represented in such cross-sections of fossil forests. Spectacular examples include the 7-m-tall Sigillaria trees found standing upright in sandstones overlying the Angelika and Sonnenschein coal seams in Westphalian A (Langsettian) strata of the Ruhr District, western Germany (Klusemann and Teichmüller 1954; Teichmüller 1955, Abb. 11). These well-figured columnar tree trunks, 3 to 5 m apart, show that the periderm cylinder may have allowed the remains to stay upright for the time necessary to deposit the sand now preserved as 7 m of bedded sandstones. This is quite a feat, requiring virtually instant sedimentation. Teichmüller’s figure suggests that a single generation of trees, presumably all of the same kind, was represented. Upright tree trunks, particularly those attributed to Sigillaria, are quite common in the geological record. However, although records of lycopsid forests in two-dimensional cliff and quarry faces are relatively common, records of stands of trunks in three-dimensions are rare. Observation of such stands requires either consecutive phases of two-dimensional outcrop in quarries and/or coal mines and the opportunity to follow the workings (e.g., DiMichele et al. 1996), or a different kind of preservation.

13 In the present paper only arborescent lycopsids of early Westphalian (middle Pennsylvanian) age are described from specimens preserved as adpressions. Thus we include not only classic genera like Lepidodendron, Lepidophloios and Sigillaria, but also some less-often-recorded taxa such as Bergeria (= Ulodendron sensu Thomas), Diaphorodendron and Omphalophloios. The uncommon but widespread genus Bothrodendron is an arborescent lycopsid not recorded from Canada (possibly due to limited collecting rather than absence). All of the genera included here are based on stem remains (including branches in genera that had repeatedly branched crowns or produced deciduous lateral branch systems). Where strobili have been found in connection or association, these are noted, as are parts of strobili (sporophylls) known to belong to named taxa. Lycopsid leaves are normally found detached, but where they are occasionally part of a branching system they are also mentioned.

REPOSITORY OF SPECIMENS, LOCALITY AND CATALOGUE NUMBERS

14 Most of the specimens revised in the present paper are in the collections of the Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa (catalogue numbers preceded by GSC). More complete information about localities is provided in the memoirs published by Bell (1938, pp. 108–115; 1940, pp. 133–139; 1944, p. 111–118; 1962, pp. 63–64). Three additional specimens have been studied from the Donald Reid collection (DRC), Joggins Fossil Centre, Joggins, Nova Scotia. A taxon list is provided in the Appendix.

15 Note that we do not cover lycopsids from the Fern Ledges locality of New Brunswick. Stopes (1914, p. 124) commented on “the extraordinary scarcity of both Sigillaria and Lepidodendron” at this locality. This scarcity is undoubtedly due to depositional circumstances. Although rooted vegetation has been reported from Fern Ledges by Falcon-Lang and Miller (2007), the evidence is unconvincing. All plant-bearing strata in the Fern Ledges section show drifted remains, including a high proportion of comminuted plant debris, and it is likely that shallow marine facies are represented. This would largely explain the absence of lycopsid tree fragments there. The records of Lepidodendron sp. and Sigillaria sp. by Stopes (1914) are all questionable.

SYSTEMATICS

16 In this section, partial synonymy lists are provided with special emphasis on types and illustrated records from North America. All synonyms (old and new) accepted by the present authors are included. European illustrations and/or specimens in the possession of the present writers are only cited where they provide a better understanding of the taxa involved. The system of annotations follows that of Cleal et al. (1996 — simplified/modified): * = protologue; § = first publication of currently accepted combination; T = other illustrations of the type specimen(s); ? = reference to doubtful specimens due to poor illustration or preservation; p (pars) = only part of the published specimens belong to the species; v (vide) = specimen(s) that the authors have seen; k = reference that includes cuticular evidence.

17 Descriptions and/or comparisons and remarks on published specimens are given as well as the stratigraphic and geographic distribution of taxa and their occurrence in Canada and the United States.

Order Lepidodendrales

Family Lepidodendraceae

Genus Lepidodendron Sternberg 1820

18 TYPE. Lepidodendron aculeatum Sternberg 1820

19 GENERIC CHARACTERIZATION. Lepidodendron is one of the most cited and figured Carboniferous genera of arborescent lycopsid stem remains. It is characterized by vertically elongate, rhomboidal to fusiform leaf cushions, generally without leaves. Leaf scars are situated in the upper half of the cushion. Within the leaf scar are three foliar markings, a central one corresponding to the vascular bundle and two lateral parichnos strands. A ligule pit is present above the leaf scar and two infrafoliar parichnos markings occur below the scar, i.e., on the cushion surface. Stems of Lepidodendron with attached leaves have been figured only rarely (e.g., Kosanke 1979, figs. 1, 4; Leary and Thomas 1989, figs. 5–8; Josten and Amerom 2003, Taf. 26, fig. 1; Opluštil 2010, figs. 1A, 2A, 4A,B; and Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2010, pl. XI, fig. 1).

Lepidodendron was discussed by DiMichele (1983) based on the anatomically preserved species Lepidodendron hickii, which he regarded as equivalent to the adpression species Lepidodendron aculeatum. DiMichele (1983, 1985) noted the rather indiscriminate use of the name Lepidodendron; he thus endeavoured to distinguish several more closely circumscribed genera based primarily on anatomical detail, as found in permineralized remains. Although anatomical detail is reflected only to a limited extent in compressions/impressions of the stem surface, certain characters permit correlation between the different preservational modes.

Relatively few of the 414 species of Lepidodendron named in the Fossilium Catalogus (Jongmans 1929, 1936; Jongmans and Dijkstra 1969; Dijkstra and Amerom 1991, 1994) should remain in Lepidodendron sensu stricto. The large number of named taxa also includes several synonyms. Rather surprisingly, the oft-quoted Lepidodendron aculeatum, generally regarded as synonymous with Lepidodendron obovatum, is not as common as the published records suggest.

The following genera have been separated from Lepidodendron in recent decades (see reviews by DiMichele 1980; Bateman and DiMichele 1991; Bateman et al. 1992; and Phillips and DiMichele 1992): Anabathra /Paralycopodites, Diaphorodendron, Synchysidendron, and Hizemodendron.

In the present paper, three little-known species are recorded here as Lepidodendron sensu lato, acknowledging that they do not belong in Lepidodendron, but recognizing that an exact attribution is not possible at present.

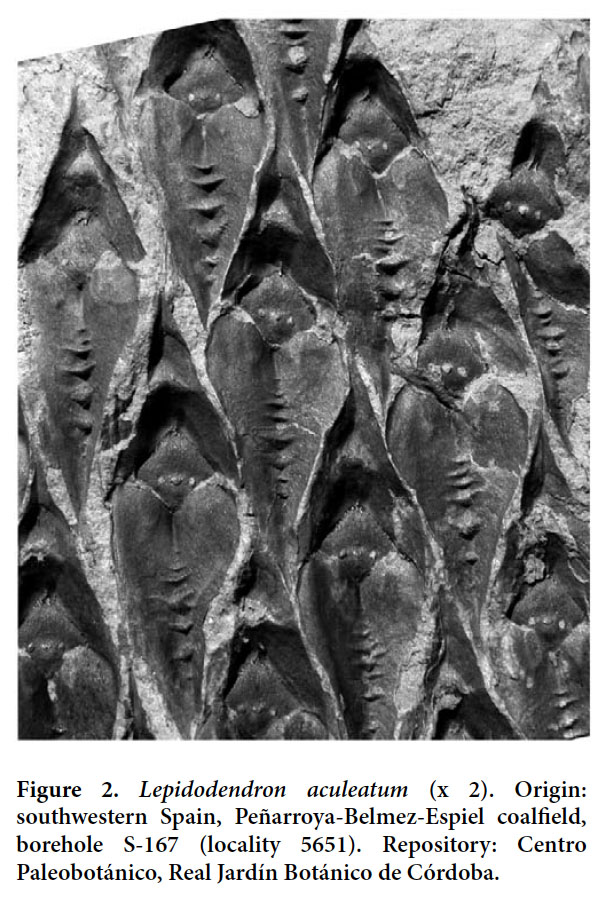

Lepidodendron aculeatum Sternberg 1820 (Fig. 2)

- * 1820 Lepidodendron aculeatum Sternberg, p. 20, Taf. VI, fig. 2; Taf. VIII, figs. 1Ba, b.

- * 1820 Lepidodendron obovatum Sternberg, p. 20, Taf. VI, fig. 1; Taf. VIII, figs. 1Aa,.b.

- * 1820 Lepidodendron crenatum Sternberg, p. 21, Taf. VIII, figs. 2Ba, b (acc. to Kidston 1886).

- * 1822 Sagenaria coelata Brongniart, p. 209, pl. I, fig. 6 (acc. to Kidston 1886).

- * 1838 Sagenaria caudata Presl in Sternberg, p. 178, Taf. LXVIII, fig. 7 (acc. to Lesquereux 1880).

- * 1858 Lepidodendron conicum Lesquereux, p. 874, pl. XV, fig. 3 (acc. to Kidston 1893, albeit with doubt).

- * 1858 Lepidodendron giganteum Lesquereux, p. 874, pl. XV, fig. 2 (acc. to Fairchild 1877).

- * 1858 Lepidodendron modulatum Lesquereux, p. 874, pl. XV, fig. 1 (acc. to Fairchild 1877).

- * 1858 Lepidodendron obtusum Lesquereux (non Sauveur), p. 875, pl. XVI, fig. 6 (acc. to Fairchild 1877).

- * 1860 Lepidodendron venustum Wood, pp. 239-240, pl. 5, fig. 2 (included by Lesquereux 1880 in Lepidodendron obtusum).

- * 1860 Lepidodendron mekiston, Wood, p. 239, pl. 5, fig. 3 (acc. to Wood 1869, p. 345).

- * 1860 Lepidodendron Lesquereuxi Wood, p. 240, pl. 5, fig. 4 (acc. to Lesquereux 1880).

- * 1860 Lepidodendron Bordae Wood, p. 240, pl. 6, fig. 3 (included by Wood 1869 in Lepidodendron obovatum, regarded as a synonym of Lepidodendron aculeatum).

- * 1860 Lepidodendron magnum Wood, pl. 6, fig. 4 (acc. to Fischer 1905a, who included this species in Lepidodendron obovatum, as a synonym of Lepidodendron aculeatum).

- * 1869 Lepidodendron uraeum Wood, pp. 343–344, pl. IX, fig. 5 (acc. to Lesquereux 1880).

- 1879-80 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Lesquereux, p. 371, pl. LXIV, fig. 1.

- 1934 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Arnold, p. 188, pl. VI, fig. 6.

- 1934 Lepidodendron obovatum, Arnold, p. 189, pl. VI, fig. 1.

- v 1944 Lepidodendron aculeatum?, Bell, p. 90, pl. XLIX, fig. 5 (decorticated); pl. L, fig. 3.

- 1949 Lepidodendron obovatum, Arnold, pp. 161–162, pl. III, fig. 1 (decorticated), fig. 2.

- 1949 Lepidodendron modulatum, Arnold, pp. 170–171, pl. III, fig. 3.

- 1957 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Janssen, pp. 38–39, fig. 15.

- 1959 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Canright, p. 28, pl. 1, fig. 6.

- 1959 Lepidodendron obovatum, Canright, p. 20, 28, pl. 1, fig. 2.

- 1959 Lepidodendron modulatum, Canright, p. 20, 28, pl. 1, fig. 3.

- 1962 Lepidodendron sp., Gillespie and Clendening, p. 129, pl. 3, fig. 5.

- 1963 Lepidodendron modulatum, Wood, p. 35, pl. 1, fig. 6 (same as Canright 1959, pl. 1, fig. 3).

- 1963 Lepidodendron obovatum, Wood, pp. 35–36, pl. 1, fig. 7.

- ? 1963 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Wood, pp. 33–34, pl. 1, fig. 2.

- T 1963 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Němejc, Tab. XII, fig. 4; Tab. XIII, fig. 3 (partial illustration of the holotype).

- 1966 Lepidodendron, Gillespie et al., p. 24, 52, pl. 6, fig. 5.

- 1967 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Tidwell, p. 19, pl. 1, fig. 5 (poorly preserved).

- 1969 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Darrah, p. 181, pl. 30, fig. 1.

- T k 1970 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Thomas, p. 146, pl. 29, fig. 1 (photograph of the specimen illustrated in Sternberg 1820, Taf. VI, fig. 2), fig. 2 (Lepidodendron obovatum Sternberg 1820, Taf. VI, fig. 1a), fig. 3 (Sagenaria rugosa Presl in Sternberg 1838, Taf. LXVIII, fig. 4), fig. 4 (Sagenaria caudata Presl in Sternberg 1838, Taf. LXVIII, fig. 7); pl. 30, fig. 1 (Lepidodendron crenatum Sternberg 1820, Taf. VIII, fig. 2B), fig. 5; pl. 31, figs. 1–3; text-figs. 2A–F, 3A–E.

- 1974 Lepidodendron lanceolatum sensu Noé, Tidwell et al., pp. 126–128, pl. 4, fig. 2.

- 1978 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Gillespie et al., p. 46, 52, 53, pl. 11, fig. 1 (same as Gillespie and Clendening 1962), fig. 2 (drawing).

- 1978 Lepidodendron cf. wortheni, Gillespie et al., p. 46, 52, 53, pl. 11, fig. 7.

- 1979 Lepidodendron obovatum var. grandifolium Kosanke, p. 431, fig. 1, fig. 2 (drawing), fig. 3 (leaves), fig. 4.

- 1980 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Zodrow and McCandlish, p. 79, pl. 114, fig. 2; pl. 115, fig. 1, fig. 2 (poorly figured).

- p 1981 Lepidodendron aculeatum, DiMichele and Dolph, pl. 2, fig. 13; non pl. 2, fig. 14 (= Lepidodendron bellii as introduced in the present paper).

- 1982 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Oleksyshyn, pp. 11–13, fig. 7A (poorly figured).

- p 1984 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Jennings, p. 304, 307, pl. 3, fig. 1; non pl. 1 fig. 4 (decorticated — resembles Lepidodendron veltheimii).

- 1985 Lepidodendron cf. wortheni, Gillespie and Crawford, p. 252, pl. II, fig. 2.

- 1989 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Leary and Thomas, figs. 3, 4, 6, 8.

- 1989 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Gillespie et al., p. 5, pl. 1, fig. 11.

- 1992 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Tidwell et al., p. 1014, figs. 2.2, 2.3.

- T 1992 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Kvaček and Kvaček, Tab. I, fig. 1 (part of Sternberg’s 1820 holotype).

- 1995 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Willard et al., p. 81, 82, fig. 8E.

- 1996 Lepidodendron cf. aculeatum, Calder et al., p. 292, fig. 8a.

- p 1996 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Cross et al., p. 402, fig. 23-5.2; non p. 401, fig. 23-4.5 (poorly figured and difficult to assign specifically, but definitely not Lepidodendron aculeatum).

- T 1997 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Kvaček and Straková, p. 27, pl. 2, fig. 1 (photograph of holotype).

- 1997 Lepidodendron obovatum, Kvaček and Straková, p. 112, pl. 39, fig. 5 (photograph of holotype).

- 1997 Lepidodendron crenatum, Kvaček and Straková, p. 57, pl. 17, fig. 1 (photograph of holotype).

- 1997 Sagenaria caudata, Kvaček and Straková, p. 47, pl. 10, fig. 6 (photograph of holotype).

- 2005 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Dilcher et al., p. 155, figs. 1.1, 1.2.

- 2005 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Dilcher and Lott, pl. 117, figs. 2, 4, fig. 3 (same as Dilcher et al. 2005, fig. 1.1).

- T 2005 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Cleal et al., p. 46, fig. 4 (lower) (copy of Sternberg’s figure).

- 2005 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Cleal et al., p. 46, fig. 4 (upper) (copy of Lepidodendron obovatum holotype).

- 2006 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Calder et al., p. 180, 182, figs. 10B, C.

- p 2006 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Wittry, pp. 104–105, figs. 1, 2 (same as Lequereux’s Lepidodendron modulatum 1879, pl. XLIV, figs. 13, 14), fig. 3, figs. 4–7 (drawings after Thomas 1970); non fig. 8 (= Diaphorodendron decurtatum).

- p 2006 Lepidodendron rimosum, Wittry, fig. 3; non p.107, fig. 1 (copy of Lepidodendron simplex Lesquereux 1866, a synonym of “Lepidodendron” rimosum); non fig. 2 (copy of Lesquereux 1879, pl. LXIV, fig. 11).

- p 2009 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Lucas et al., p. 237, 239, 240, figs. 3C, 5A–5D; non figs. 5E, 5F (= Lepidodendron dichotomum).

- v 2010 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez, p. 257, 262, 264, 266, 270, 273, pl. XI, fig. 1 (specimen with attached leaves).

- v 2012 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Álvarez-Vázquez and Wagner, p. 1234, fig. 3 (same specimen as figured here as Fig. 2).

- p 2013 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Lucas et al., p. 45, fig. 5.2.; non fig. 5.1. (= Lepidodendron bellii).

- 1873 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Dawson, p. 24, pl. V, figs. 37, 37a (decorticated and indeterminable specifically); p. 32, pl. IX, fig. 75 (= “Lepidodendron” feistmantelii); pl. IX, figs. 75a–75c (diagrammatic drawings that cannot be judged properly).

- 1949 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Arnold, pp. 160–161, pl. II, figs. 1, 3, 4 (possibly referable to Bergeria dilatata).

- 1958 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Langford, p. 65, fig. 101 (same specimen as in p. 23, fig. 14) (to be compared with “Lepidodendron” fusiforme).

- 1966 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Bell, p. 26, pl. XII, fig. 2 (Lepidodendron bellii — holotype).

- 1968 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Abbott, p. 7, pl. 12, fig. 8 (very diagrammatic drawing that is difficult to judge but unlikely to be Lepidodendron aculeatum).

- 1974 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Jennings, p. 460, pl. 1, fig. 1 (to be compared with Lepidodendron bellii).

- 1974 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Tidwell et al., p. 121, pl. 1, fig. 3 (to be compared with “Lepidodendron” fusiforme).

- 1982 Lepidodendron aculeatum, DiMichele in Eggert and Phillips, p. 20, pl. 2, fig. B (= Diaphorodendron decurtatum).

- 1985 Lepidodendron cf. aculeatum, Gastaldo, p. 292, pl. 3, fig. A (difficult to judge from illustration, but clearly not Lepidodendron aculeatum; resembles Diaphorodendron decurtatum).

- 1987 Lepidodendron aculeatum, DiMichele and DeMaris, p. 149, fig. 3 (decorticated — similar to specimen figured by Bell 1944), figs. 4, 5 (= “Lepidodendron” jaraczewskii acc. to DiMichele personal communication 2013).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 220 REMARKS. The list above includes all names generally recognized as synonyms of the widely reported Lepidodendron aculeatum, as well as all figured North American remains. The holotypes of Lepidodendron aculeatum (Sternberg 1820, Taf. VI, fig. 2) and Lepidodendron obovatum (Sternberg 1820, Taf. VI, fig. 1) both originated from the Radnice Member (Bolsovian), Kladno Formation, Bohemia, Czech Republic. Although most authors accept that these two species are synonymous, there has been no agreement on a preferred specific epithet. Andrews (1955, p. 178) mentioned that Lepidodendron dichotomum was the first species of Lepidodendron figured by Sternberg, implying that this would be the type species. However, he suggested that Lepidodendron obovatum might be a better type. On the other hand, Chaloner and Boureau (in Boureau 1967) pointed out that the problems surrounding the use of Lepidodendron obovatum made this species unsuitable. They regarded Lepidodendron aculeatum as more appropriate. We concur considering that Lepidodendron aculeatum has been used in a consistent manner, whereas the use of Lepidodendron obovatum has been more controversial. [We acknowledge that by admitting the synonymy of Lepidodendron aculeatum with Lepidodendron obovatum but not following Andrews’ choice of the latter as the correct name, we are contravening rules of priority (ICBN Article 11.5; http:// www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php?page=art11).]

From the Cumberland Basin, Bell (1944) figured as Lepidodendron aculeatum? two specimens representing quite substantial tree trunks. One of these specimens (Bell 1944, pl. XLIX, fig. 5) was available for us to study. Unfortunately, this is the least well preserved. It is the cast of a decorticated specimen that, although it shows the outline of the leaf cushions reasonably well, provides little detail of the leaf scar. It lacks a leaf trace and shows only vague parichnos markings. Only one leaf scar is clearly visible, at about one third the height of the elongate rhombic leaf cushion. Although preservation is poor, the size and shape of the keeled leaf cushions and the position of the relatively small leaf scar suggest that the Lepidodendron aculeatum determination by Bell is correct. The second specimen figured by Bell (1944, pl. L, fig. 3), although also poorly preserved, even more clearly belongs to this species.

21 In order to facilitate comparison with Lepidodendron bellii (= Lepidodendron obovatum sensu Presl in Sternberg 1838, non Sternberg 1820), we figure a well-preserved specimen of Lepidodendron aculeatum from most Langsettian strata in the Peñarroya Basin, southwestern Spain (Fig. 2).

22 COMPARISONS. Leaf cushions of Lepidodendron bellii are rhomboidal, with a marked horizontal asymmetry. The upper and lower ends of leaf cushions in this species are only slightly inflected in opposite directions, whereas in Lepidodendron aculeatum the cushions are fusiform, symmetrical and with acuminate apex and base that are distinctly inflected in opposite directions. The leaf scar is rhomboidal in both species, but is located in the upper third in Lepidodendron bellii, and a little above the middle in Lepidodendron aculeatum. Also, the length/breadth ratio of the leaf cushion is 3–4 in Lepidodendron aculeatum and up to 2.5 in Lepidodendron bellii. However, this ratio might vary depending on the position on the stem and is thus an unreliable character for species distinction.

23 STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. This is one of the most commonly (albeit not always correctly) cited species of Pennsylvanian Lepidodendraceae, with a range that includes most of the Namurian (from Chokierian upwards) as well as the entire Westphalian, where it is most frequent.

24 OCCURRENCE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES, CANADA. Cumberland Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 1983 (GSC 8562 — decorticated); Springhill (GSC 8558). Calder et al. (2006). Sydney Basin (Nova Scotia): Zodrow and McCandlish (1980). Calder et al. (1996).

25 OCCURRENCE IN THE UNITED STATES. Alabama: Gillespie and Rheams (1985, unfigured), Dilcher and Lott (2005), Dilcher et al. (2005). Arizona: Tidwell et al. (1992). Georgia: Gillespie and Crawford (1985), Gillespie et al. (1989). Illinois: Lesquereux (1879–1880), Janssen (1957), Langford (1958), Darrah (1969), Jennings (1984), Leary and Thomas (1989), Wittry (2006). Indiana: Canright (1959), Wood (1963), DiMichele and Dolph (1981), Willard et al. (1995). Michigan: Arnold (1934, 1949). New Mexico: Lucas et al. (2009), Lucas et al. (2013). Ohio: Cross et al. (1996). Pennsylvania: Wood (1860, 1869), Lesquereux (1858), Lesquereux (1879–1880), Oleksyshyn (1982). Rhode Island: Lesquereux (1879–1880). Utah: Tidwell (1967), Tidwell et al. (1974). West Virginia: Gillespie and Clendening (1962), Gillespie et al. (1966), Gillespie et al. (1978); Kosanke (1979).

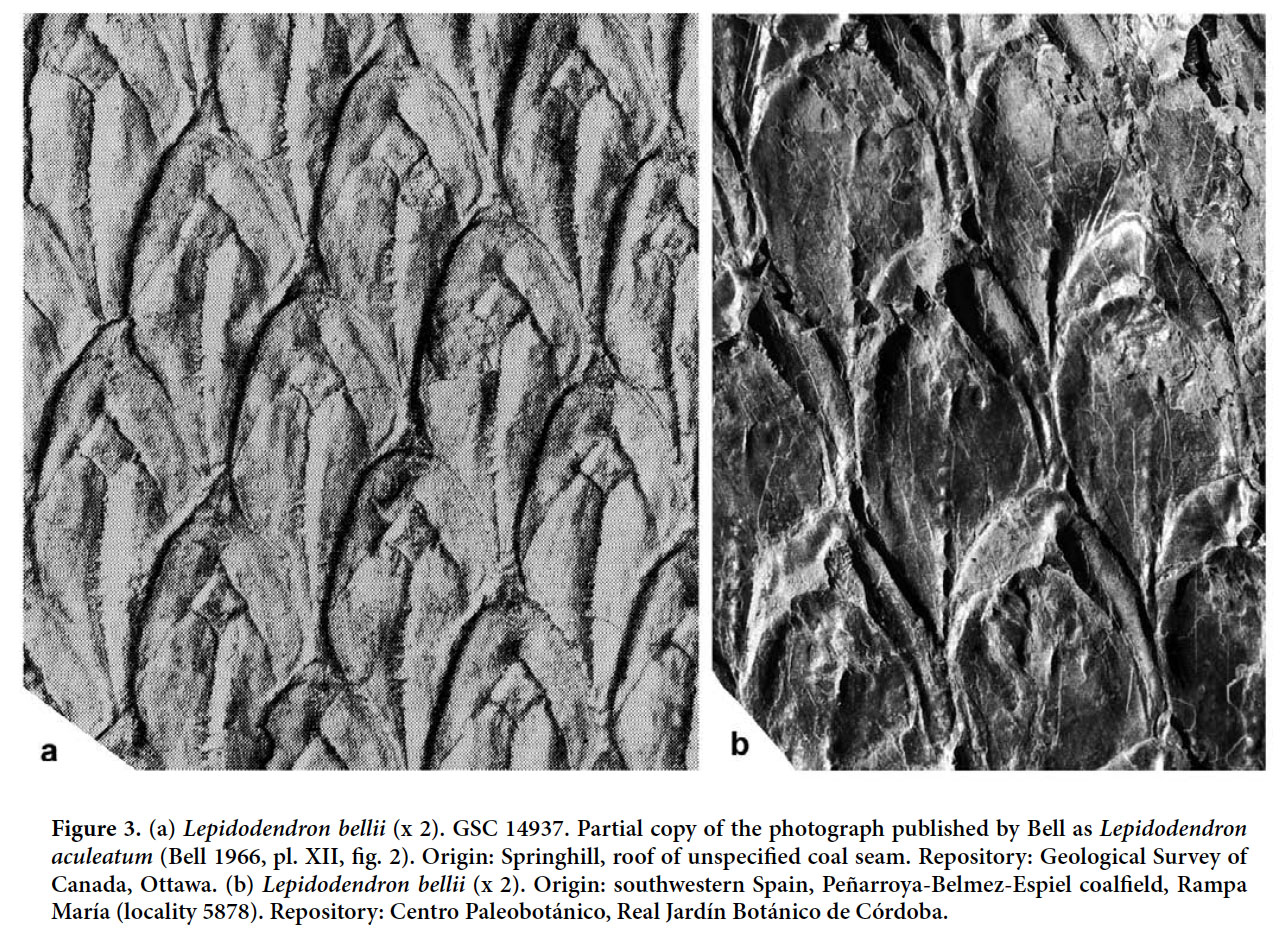

Lepidodendron bellii sp. nov. (Figs. 3a–b)

- 1838 Sagenaria obovata Presl in Sternberg, p. 178, Taf. LXVIII, fig. 6.

- ? * 1848 Lepidodendron costaei Sauveur, pl. LXI, fig. 1.

- ? * 1848 Lepidodendron obtusum Sauveur, pl. LXI, fig. 2.

- ? * 1858.Lepidodendron carinatum Lesquereux (non Brongniart), p. 875, pl. XV, fig. 4 (see Jongmans, 1929) (homonym of Lepidodendron carinatum Brongniart).

- ? * 1858 Lepidodendron clypeatum Lesquereux, p. 875, pl. XV, fig. 5; pl. XVI, fig. 7 (decorticated).

- ? * 1858 Lepidodendron vestitum Lesquereux, p. 874, pl. XVI, fig. 3.

- p 1879-80 Lepidodendron clypeatum, Lesquereux, p. 380, pl. LXIV, figs. 16–16b; non pl. LXIV, figs. 17, 18 (drawing of leaf cushion).

- p 1937 Lepidodendron obovatum, Jongmans, p. 404, pl. 24, fig. 61; non p. 403, pl. 23, fig. 55 (= Bergeria dilatata).

- ? 1944 Lepidodendron obovatum?, Bell, p. 89, pl. LII (poorly preserved).

- ? 1957 Lepidodendron obovatum, Janssen, p. 39, 41, fig. 16 (poorly preserved).

- ? 1963 Lepidodendron vestitum, Wood, p. 36, pl. 1, fig. 9 (leaf cushions laterally squashed).

- 1963 Lepidodendron obovatum, Němejc, Tab. XII, fig. 3 (photograph of part of the specimen figured by Presl in Sternberg 1838 as Sagenaria obovata).

- p 1964 Lepidodendron obovatum, Crookall, pp. 239–242, pl. LX, fig. 4; text-fig. 77B (drawing of leaf cushion); non pl. LX, fig. 3 (to be compared with Diaphorodendron decurtatum); non text-fig. 78 (copy of Hirmer’s 1927 reconstruction of the tree).

- * 1966 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Bell, p. 26, pl. XII, fig. 2 (reproduced partially herein as holotype of Lepidodendron bellii).

- ? 1967 Lepidodendron obovatum, Tidwell, p. 19, pl. 2, fig. 6 (difficult to judge from illustration; presence of leaf scars unclear).

- p k 1970 Lepidodendron mannabachense (sic), Thomas, pl. 30, fig. 3 (photograph of the specimen figured as a drawing of Sagenaria obovata); non pp. 157–159, pl. 30, fig. 4 (same specimen as Lepidodendron mannebachense Presl in Sternberg 1838, Taf. LXVIII, fig. 2); pl. 32; pl. 34, figs. 1, 2, 7, 8; text-figs. 7, 8.

- 1974 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Jennings, p. 460, pl. 1, fig. 1.

- ? 1974 Lepidodendron mannabachense (sic), Tidwell et al., p. 123 (as Lepidodendron obovatum in Tidwell 1967).

- 1978 Lepidodendron obovatum, Gillespie et al., p. 52, pl. 11, figs. 3 (drawing), 5; pl. 11, fig. 6.

- p 1981 Lepidodendron aculeatum, DiMichele and Dolph, pl. 2, fig. 14; non pl. 2, fig. 13 (= Lepidodendron aculeatum).

- 1985 Lepidodendron obovatum, Gillespie and Rheams, p. 194, 196, pl. III, fig. 6.

- 1989 Lepidodendron obovatum, Gillespie et al., p. 5, 6, pl. 2, fig. 5.

- 1996 Lepidodendron cf. obovatum, Calder et al., p. 292, fig. 8b.

- 1997 Sagenaria obovata, Kvaček and Straková, p. 163, pl. 64, fig. 2 (photograph of specimen figured as a drawing by Presl in Sternberg 1838, Taf. LVIII, fig. 6).

- 2005 Lepidodendron obovatum, Dilcher et al., pp. 155–156, figs. 1.3, 1.4.

- 2005 Lepidodendron obovatum, Dilcher and Lott, pl. 117, fig. 1 (same as Dilcher et al. 2005, fig. 1.3); pl. 118, fig. 4.

- v 2010 Lepidodendron mannebachense, Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez, p. 257, 262, 266.

- p 2013 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Lucas et al., p. 45, fig. 5.1.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 326 HOLOTYPE. Pl. XII, fig. 2 of Bell 1966 (partially copied here as Fig. 3); Springhill Mines, Cumberland Basin, Nova Scotia.

27 DERIVATION OF NAME. After Walter A. Bell, in recognition of his fundamental contributions to Carboniferous paleobotany in Canada.

28 DIAGNOSIS. Leaf cushions rhomboidal, higher than wide, with rounded lateral angles and acute base and apex; upper part of area above the leaf scar relatively small, and that below large and with a keel. Leaf scars rhomboidal and situated high on the cushion. Infrafoliar parichnos small, vertically elongate.

29 DESCRIPTION (based on the specimen figured by Bell 1966). Leaf cushions rhomboidal, higher than wide, horizontally asymmetrical, with rounded lateral angles and an acute base and apex that are very slightly inflected in opposite directions. Dimensions: 28–30 mm long and 11–12 mm broad; ratio = 2.5. Leaf scars rhomboidal, placed in the upper third of the cushion and occupying less than one-third of cushion width; rhomboidal, with rounded margins and three small, rounded cicatricules arranged in a line. Dimensions: 3–4 mm long and 4–5 mm broad; ratio = 0.7–0.8. Infrafoliar parichnos vertically elongate, elliptical, small, but distinct. Keel well-marked below the leaf scar, with short (less than 1 mm) transverse markings. Upper part of the field small, with a short, poorly marked keel.

30 REMARKS. Although the holotype of Lepidodendron obovatum (as photographed by Němejc 1963, Thomas 1970 and Kvaček and Straková 1997) is conspecific with Lepidodendron aculeatum, other specimens figured as Lepidodendron obovatum are not. Jongmans (1929, p. 225–244) provided the first exhaustive synonymy of Lepidodendron obovatum. Of subsequent work, most important is Němejc’s (1947, p. 53) opinion that the specimen figured as Sagenaria obovata by Presl (in Sternberg 1838, Taf. LXVIII, fig. 6), does not belong to Lepidodendron aculeatum. Presl’s specimen was refigured by Thomas (1970, pl. 30, fig. 3 — erroneously cited in his plate caption as Presl in Sternberg 1838, pl. LXVIII, fig. 2), who assigned it, incorrectly, to Lepidodendron mannebachense. The holotype of Lepidodendron mannebachense (as photographed by Thomas 1970, pl. 30, fig. 4 and Kvaček and Straková 1997, pl. 33, fig. 6) possesses almost isodiametric leaf cushions, shown by Thomas (1970, fig. 7A) to lack infrafoliar parichnos. This specimen, originating from the Lower Rotliegend (Autunian) of Manebach in Thuringia (Germany), is different from the other remains attributed to Lepidodendron mannebachense by Thomas (1970). The latter, of Westphalian age, are characterized by more elongate leaf cushions showing infrafoliar parichnos.

The magnificent specimen from the roof of an unspecified coal seam at Springhill, Nova Scotia, figured by Bell (1966, pl. XII, fig. 2) as Lepidodendron aculeatum is regarded as conspecific with the specimen figured as Lepidodendron obovatum by Presl in Sternberg (1838, pl. LXVIII, fig. 6), and which we regard as different. The specimen from Springhill is here selected as the holotype of Lepidodendron bellii.

The possible synonyms in the list above refer to specimens (holotypes) that are poorly figured and which require revision of material not available to us.

31 STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. Presl’s specimen is from the Bolsovian of the Radnice Member, Kladno Formation, Bohemia. Crookall (1964) recorded this species (as Lepidodendron obovatum) throughout the Westphalian.

32 OCCURRENCE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES, CANADA. Cumberland Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): Springhill (GSC 5813 — decorticated). Bell (1966): Springhill (GSC 14937 — holotype). Sydney Basin (Nova Scotia): Calder et al. (1996).

33 OCCURRENCE IN THE UNITED STATES. Alabama: Lesquereux (1879–1880), Gillespie and Rheams (1985), Dilcher and Lott (2005), Dilcher et al. (2005). Georgia: Gillespie et al. (1989). Illinois: Lesquereux (1879–1880), Janssen (1957), Jennings (1974), Wittry (2006). Indiana: Wood (1963), DiMichele and Dolph (1981). New Mexico: Lucas et al. (2013). Pennsylvania: Lesquereux (1879–1880). Utah: Tidwell (1967), Tidwell et al. (1974). West Virgina: Jongmans (1937); Gillespie et al. (1978).

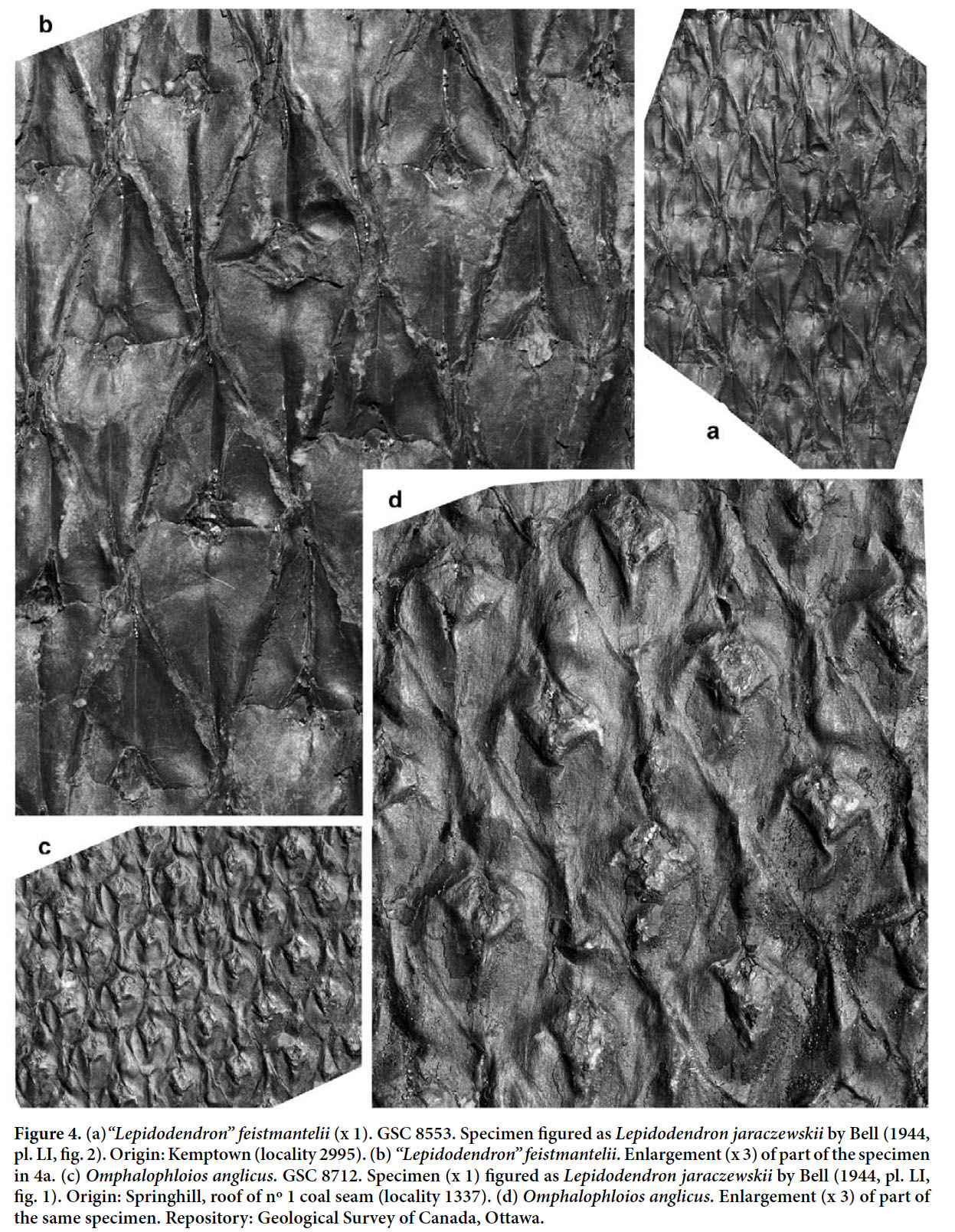

“Lepidodendron” feistmantelii Zalessky 1904 (Figs. 4a–b)

- p 1873 Lepidodendron aculeatum, Dawson, p. 32, pl. IX, fig. 75; pl. IX, fig. 75b (?); non pl. IX, figs. 75a (drawing of a decorticated specimen that seems indeterminable); non pl. IX, fig. 75c (drawing of leaf scar with presumed ligule pit (?) that does not seem to belong to “Lepidodendron” feistmantelii); non p. 24, pl. V, figs. 37, 37a (rough drawings of a lepidodendrid with characteristics different from “Lepidodendron” feistmantelii).

- * 1904 Lepidodendron Feistmanteli Zalessky, pp. 20–21, 93, pl. IV, figs. 6, 10.

- p 1904 Lepidodendron Veltheimi, Zalessky, pp. 21–23, 94, pl. IV, fig. 9; pl. VIII, fig. 8; non pl. IV, figs. 3–5 (to be compared with Lepidodendron jaraczewskii Zeiller); non pl. IV, fig. 12 (decorticated); non pl. IV, fig. 8 (decorticated).

- 1907 Lepidodendron Veltheimi, Zalessky, pp. 436–437, Tab. XXIII, fig. 13.

- 1913–14 Lepidodendron Jaraczewskii, Bureau, pp. 113–115, pl. XL, figs. 1, 1A; pl. XXXIX, figs. 2, 2A (?), figs. 3, 3A (?).

- vp 1944 Lepidodendron jaraczewskii, Bell, p. 89, pl. LI, fig. 2 (refigured here as Figs. 4a, b); non pl. LI, fig. 1 (= Omphalophloios anglicus; see Figs. 4c,d of the present paper).

- k 1970 Lepidodendron feistmanteli, Thomas, p. 155, pl. 33, fig. 3; pl. 34, fig. 5 (cuticle); text-figs. 6A–E.

- 1994 Lepidodendron feistmantelii, Cleal and Thomas, p. 63, pl. 4, fig. 5 (same as Thomas 1970, pl. 33, fig. 3); text-figs. 30C, 30D (same as Thomas 1970, text- figs. 6A, 6B).

- 1974 Lepidodendron feistmanteli, Tidwell et al., p. 131, pl. 3, figs. 1, 5 (shows small, equidimensional leaf cushions with a distinct leaf scar; to be compared with Lepidodendron dichotomum).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 434 DESCRIPTION. Leaf cushions smooth, only slightly raised, spirally arranged, and separated from one another by narrow grooves (c. 1 mm width); elongate rhomboidal, bilaterally symmetrical, with a very prominent keel (in the impression), present both above and below the leaf scar; upper and lower angles of cushions acute, with almost straight margins that are only very slightly inflected in opposite directions; lateral angles more rounded. Dimensions: 30–35 mm long and 11–13 mm broad, with the maximum breadth about the middle; length/breadth ≈ 2.7. Leaf scar situated a little above the middle of cushion, prominent, 3.5–4.5 mm broad, occupying one third of cushion width; its lateral angles prolonged into two well-marked straight, horizontal lines reaching the cushion margin. Vascular bundle prints and infrafoliar parichnos lacking. Ligule scar present at 2–3 mm above the leaf scar.

35 REMARKS. Bell (1944) figured and described as Lepidodendron jaraczewskii two very different specimens. One of these (Bell 1944, pl. LI, fig. 1) may be attributed to Omphalophloios anglicus (see below). The other specimen (Bell 1944, pl. LI, fig. 2 — Figs. 4a–b of the present paper) shows leaf cushions with a prominent keel both above and below the leaf scar and strongly marked straight lines from the edges of the leaf scar to the cushion margin. Lepidodendron jaraczewskii also possesses rhomboidal, elongate leaf cushions, but keels are less prominent and the lateral lines from the leaf scars curve downwards to reach the cushion margin. This is quite different to the pattern observed in the specimen from Nova Scotia.

Thomas (1970) assigned both of Bell’s specimens to Lepidodendron feistmantelii, an identification that we support only for one (Bell 1944, pl. LI, fig. 2 — Figs. 4a–b herein). Zalessky (1904, pl. IV, figs. 6, 10) based Lepidodendron feistmantelii on two specimens from the Donets Basin that show well-marked, rhomboidal, isodiametric, smooth leaf cushions with a marked keel and a centrally placed leaf scar. Zalessky (1904, pl. IV, fig. 9; pl. VIII, fig. 8) also figured two specimens under the name Lepidodendron veltheimii that show the same characters albeit with more elongate leaf cushions. This is regarded here as being within the intraspecific variation Zalessky (1904) considered Lepidodendron jaraczewskii, the specific name later used by Bell (1944), as conspecific with Lepidodendron veltheimii. However, the holotype of Lepidodendron veltheimii as photographed (upside down) by Kvaček and Straková (1997, pl. 54, fig. 4) has smaller leaf cushions with proportionately larger, transversally elongate leaf scars occupying most of the cushion width. Also, the arched lines that meet the cushion margin from the lateral sides of the leaf scar in Lepidodendron jaraczewskii are not present in Lepidodendron veltheimii.

36 STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. “Lepidodendron” feistmantelii is very rare. Zalessky’s material is from two different horizons in the Upper Bashkirian of the Donets Basin (C23) and Middle Moscovian (C26). In Great Britain, the species ranges from Langsettian to lower Bolsovian (see Thomas 1970). Bureau’s (1913) specimens come from the Namurian (Serpukhovian?) of Basse Loire, southern France.

37 OCCURRENCE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES, CANADA. Pictou Coalfield (Stellarton Basin, Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 2995 (GSC 8553) (Bell 1944, p.89 recorded the specimen from this locality as possibly originating from the Pictou Group).

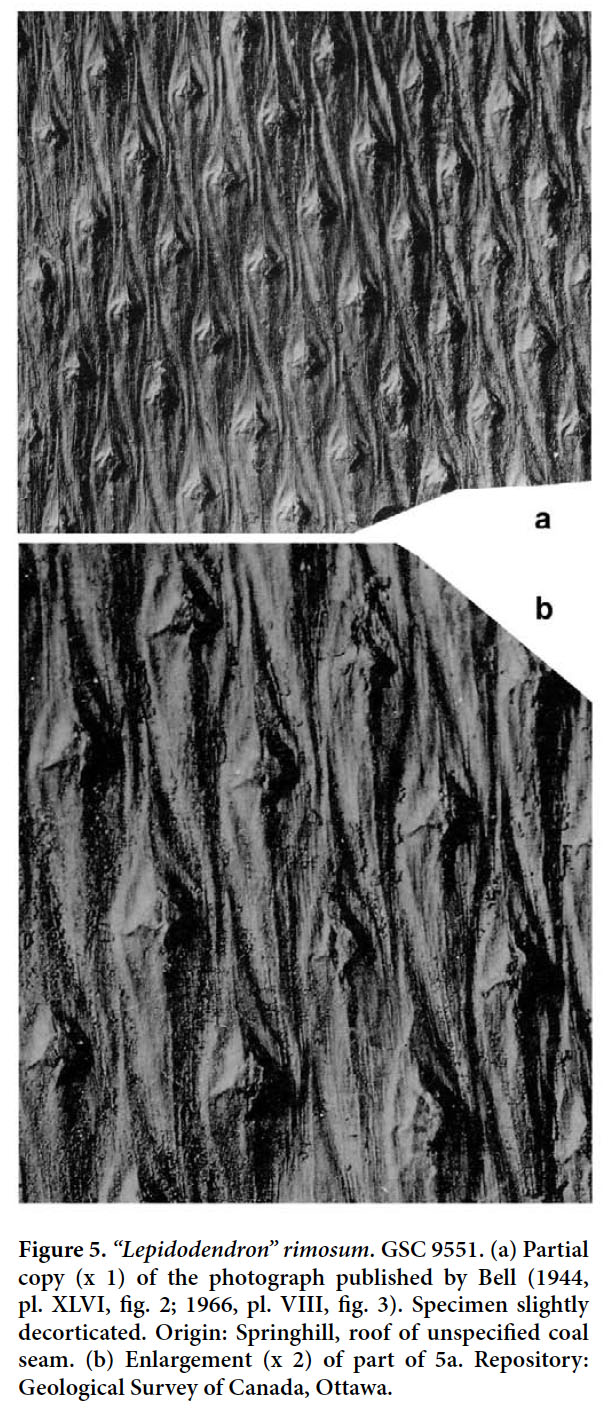

“Lepidodendron” rimosum Sternberg 1820 (Figs. 5a–b)

- * 1820 Lepidodendron rimosum Sternberg, Taf. X, fig. 1.

- * 1860 Lepidodendron dikrocheilus Wood, p. 239, pl. 6, fig. 1 (acc. to White 1899).

- * 1866 Lepidodendron simplex Lesquereux, p. 454, pl. XLV, fig. 5 (acc. to Lesquereux 1880).

- 1868 Lepidodendron rimosum, Dawson, p. 487, fig. 169D.

- * ?1868 Lepidodendron plicatum Dawson, p. 488, fig. 169C (acc. to Kidston 1911).

- 1869 Lepidodendron dicrocheilum Wood, p. 346, pl. IX, figs. 6, 6a (spelling corrected from Wood 1860).

- 1879-80 Lepidodendron rimosum, Lesquereux, pp. 392–394, pl. LXIV, fig. 11.

- p 1899 Lepidodendron rimosum var. retocorticatum White, pp. 196–198, pl. LIV, figs. 4–4a; non pl. LIV, figs. 3–3b (photograph unclear, but two drawings show well-defined leaf scars containing a leaf trace as well as parichnos markings; this specimen is different from that figured in pl. LIV, figs. 4, 4a, lacking cicatricules. White’s pl. LIV, figs. 3, 3a–b resembles “Lepidodendron” tijoui).

- T 1935 Lepidodendron rimosum, Stockmans, p. 4, pl. II, fig. 4 (photograph of the holotype).

- 1944 Lepidodendron rimosum, Bell, p. 90, pl. XLVI, fig. 2 (see Figs. 5a, b).

- 1958 Lepidodendron rimosum, Langford, p. 66, fig. 104.

- 1958 Lepidodendron veltheimi, Langford, p. 66, fig. 103.

- * 1960 Lepidodendron taxandricum Stockmans and Willière, p. 306, 308, pl. XIII, fig. 9; pl. XIV, fig. 6.

- p ?1962 Lepidodendron bretonense Bell, pl. XLVII, fig. 6 (decorticated); pl. XLVIII, fig. 6 (specimen with elongate, fusiform cushions comparable with “Lepidodendron” rimosum); non p. 53–54, pl. XLVII, fig. 5 (= Diaphorodendron decurtatum); pl. XLVIII, fig. 4 (= Diaphorodendron decurtatum); non pl. XLIX, fig. 2 (small leafy branches from same locality as others figured as Lepidodendron pictoense).

- 1966 Lepidodendron rimosum, Bell, pl. VIII, fig. 3 (same as Bell, 1944, pl. XLVI, fig. 2).

- ? 1974 Lepidodendron rimosum, Tidwell et al., p. 124, 126, pl. 2, fig. 1 (poorly preserved); pl. 5, fig. 6 (difficult to judge).

- T 1997 Lepidodendron rimosum, Kvaček and Straková, p. 130, pl. 44, fig. 4 (photograph of the holotype, which Kvaček and Straková regarded as a decorticated stem to be included in “Lepidodendron sp. indet. (Aspidiaria)”.

- p 2006 Lepidodendron rimosum, Wittry, p. 107, fig. 1 (copy of Lepidodendron simplex Lesquereux, 1866); fig. 2 (same as Lesquereux 1879–1880, pl. LXIV, fig. 11); non fig. 3 (= Lepidodendron aculeatum).

- 1957 Lepidodendron rimosum, Janssen, p. 43, fig. 21 (difficult to judge, but almost certainly not “Lepidodendron” rimosum).

- 1982 Lepidodendron cf. rimosum, Oleksyshyn, pp. 14–15, fig. 7C (decorticated specimen, indeterminable).

- 1985 Lepidodendron cf. rimosum, Gillespie and Crawford, p. 250, pl. I, fig. 6 (difficult to judge, but comparable to Bergeria dilatata).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 538 REMARKS. A single specimen showing the imprint of the bark of what seems to have been a large tree was figured by Bell (1944, 1966) as Lepidodendron rimosum. We have not re-examined this specimen, but the rhomboidal, elongate leaf cushions, with rounded lateral angles and sharp bases and apices, slightly inflected in opposite directions, closely resemble those of Sternberg’s type (photographed by Stockmans 1935 and Kvaček and Straková 1997; see also the copy of Sternberg’s figure in Crookall 1964). The prominent, relatively small, rhomboidal leaf scars, placed a little above the middle of a cushion are also similar. Although the holotype of “Lepidodendron” rimosum has much larger interareas than the Canadian specimen, this is not necessarily significant for a specific distinction. The amount of separation between leaf cushions (i.e., the width of interareas) depends largely on their position on the stem, with the older parts commonly showing larger interareas. Indeed, the wide separation between leaf cushions in the holotype made Němejc (1947, p. 62) consider that it merely represented a developmental stage in the lower part of an old tree and that this character was useless for specific distinction. This species is too poorly understood for a precise generic attribution. Therefore, we retain it provisionally in Lepidodendron.

39 COMPARISONS. Bell’s (1944, 1966) specimen of “Lepidodendron” rimosum may be compared with the rare species “Lepidodendron” fusiforme (as figured by Crookall 1964). That species has elongate leaf cushions that are similar to those of “Lepidodendron” rimosum, but lack the very wide interareas in specimens of equivalent size (representing the older part of the tree). Also, the lateral angles of the cushions are more acute or only very slightly rounded in “Lepidodendron” fusiforme. The discussions presented by Němejc (1947) and Crookall (1964) show that “Lepidodendron” fusiforme and “Lepidodendron” rimosum have often been confused or regarded as synonyms.

40 STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. According to Crookall (1964), the species, although uncommon, is recorded throughout the entire Westphalian of Great Britain. Sternberg’s holotype originated from the Bolsovian of the Radnice Member, Kladno Formation, Bohemia. Lepidodendron taxandricum, which is regarded as a synonym, originated from the upper Westphalian A (upper Langsettian) of the Campine (Kempen) coalfield in Belgium.

41 OCCURRENCE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES, CANADA. Cumberland Basin (Nova Scotia): Dawson (1868). Bell (1944): Springhill (GSC 9551). Bell (1966): Springhill (GSC 9551 — same as Bell, 1944). Pictou Coalfield (Nova Scotia): Bell (1962): locality 948 (GSC 810 — cf.); locality 990 (GSC 811 — cf.). Sydney Basin (Nova Scotia): Dawson (1868).

42 OCCURRENCE IN THE UNITED STATES. Illinois: Lesquereux (1866), Lesquereux (1879–1880), Langford (1958), Wittry (2006). Missouri: White (1899). Pennsylvannia: Wood (1860, 1869). Utah: Tidwell et al. (1974).

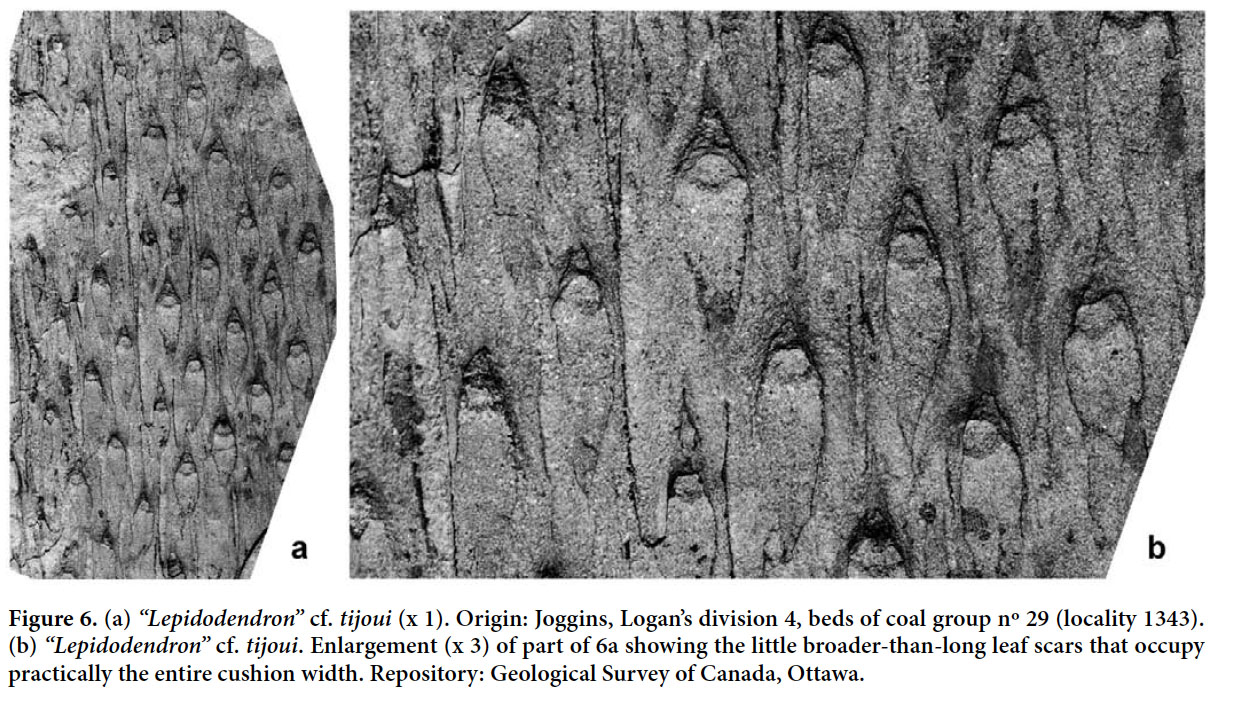

“Lepidodendron” cf. tijoui Lesquereux 1870 (Figs. 6a–b)

- * 1870 Lepidodendron Tijoui Lesquereux, p. 431, pl. XXIV, figs. 1–3b.

- ?p 1899 Lepidodendron rimosum var. retocorticatum White, pl. LIV, figs. 3–3b; non pl. LIV, figs. 4–4a.

- p 1940 Lepidodendron rimosum, Janssen, pp. 17–19, pl. III, fig. 2 (photograph of holotype of Lepidodendron tijoui, which Janssen regarded as synonymous with Lepidodendron rimosum, in agreement with Jongmans 1929); non pl. IV (holotype of Ulodendron elongatum, the ulodendroid condition of Lepidodendron rimosum according to Janssen).

- ? 1985 Lepidodendron rimosum, Wnuk, pp. 158–169, pl. 1, figs. 1–6; pl. 3, fig. 11 (branch system); text-fig. 2; text-fig. 12 (tree reconstructions).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 643 DESCRIPTION. Leaf cushions spirally arranged and separated by relatively large, unornamented interareas. They are fusiform, elongate and longitudinally symmetrical, with pointed upper and lower angles that are only very slightly inflected in opposite directions; lateral angles rounded. Dimensions: 15–20 mm long and 3–3.5 mm broad, with maximum width in the upper third; length/breadth ratio ≈ 5. Leaf scar prominent, rhomboidal, broader than long, with rounded upper and lower angles and acute lateral angles, occupying nearly the entire cushion width, 1.5–2 mm long and 2.8–3 mm broad; the three punctiform prints are placed in line, near the middle of the scar.

44 REMARKS. A single specimen from the Joggins section (locality 1343), cited as Lepidodendron rimosum by Bell (1944), but not figured, is included here as “Lepidodendron” cf. tijoui (Figs. 6a, b). Unfortunately, this specimen is not very well preserved due to the coarse grain size of the containing sediment. The elongate shape of the fusiform leaf cushions with acuminate, slightly inflected apex and base, and the position of the small leaf scars in the upper one-third of the cushion, as well as the presence of wide interareas, allow a general comparison with “Lepidodendron” rimosum. However, Bell’s specimen has smooth, apparently unornamented interareas, whereas the type material of “Lepidodendron” rimosum has more or less continuous, clearly marked lines parallel to the cushion margins. Bell’s specimen also shows a leaf scar that is a little broader than long and which occupies virtually the entire cushion width. In “Lepidodendron” rimosum it is longer than broad and occupies a little over one-third of the width. This suggests that “Lepidodendron” tijoui may be the better identification. Due to the relatively large size of both cushions and leaf scars in the holotype of “Lepidodendron” tijoui and the presence of interareas in the present specimen, we make the species attribution only tentatively.

Although the apparent absence of infrafoliar parichnos and relatively flat leaf cushions suggest a possible attribution to Diaphorodendron, we consider that this specimen shows insufficient detail for a precise generic attribution.

45 STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. The holotype of “Lepidodendron” tijoui is from St. Johns, Illinois.

46 OCCURRENCE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES, CANADA. Cumberland Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 1343 (one specimen without catalogue number).

47 OCCURRENCE IN THE UNITED STATES. Illinois: Lesquereux (1870), Janssen (1940). Missouri: White (1899). Pennsylvania: Wnuk (1985).

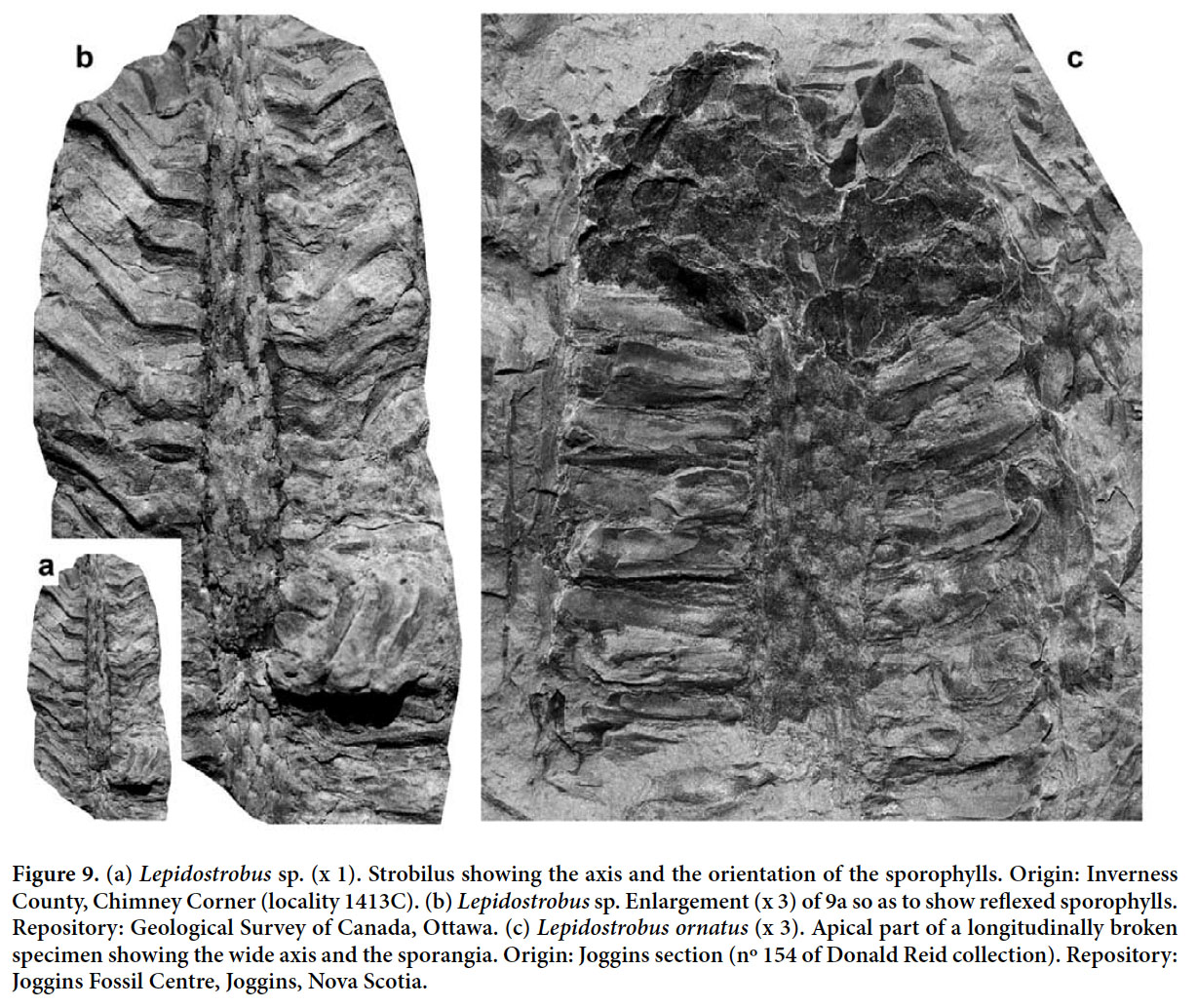

Genus Lepidophloios Sternberg 1825

48 TYPE. Lepidophloios laricinus (Sternberg 1820) Sternberg 1825

49 DIAGNOSIS. Arborescent lycopod stems covered with spirally arranged, protruding and partially overlapping leaf cushions of rhomboidal shape, contiguous, and broader than long. Leaf scars situated at or near the base of the cushion, transversely oval or rhomboidal, with a vascular trace and two lateral adjacent markings situated usually below the middle. Ligule pit above the leaf scar.

50 REMARKS. Lepidophloios is an arborescent lycopod genus introduced for stem impressions by Sternberg (1820). This genus of tree is apparently similar to Lepidodendron in size and general construction, with a profusely branched crown constituted by several consecutive dichotomies. The main distinguishing feature is the strongly protruding, downwards directed leaf cushions, overlapping partially on compression, with each cushion showing more or less rounded lateral and basal angles. The protruding leaf scar area is wider than long. Thomas (1977) was the first to record cuticles of Lepidophloios; and DiMichele (1979) described anatomically preserved material showing two kinds of branching, lateral branches and branches produced by successive isotomous dichotomy. He also reconstructed the crown of the tree.

Lepidophloios laricinus (Sternberg 1820) Sternberg 1825 (Figs. 7, 8d–g)

- * 1820 Lepidodendron laricinum Sternberg, pp. 21–23, Taf. XI, figs. 2–4.

- § 1825 Lepidofloyos laricinum, Sternberg, p. xiii.

- * 1837 Sigillaria Serlii Brongniart, pp. 433–434, pl. 158, figs. 9, 9A (upside down) (acc. to Goldenberg 1862).

- * 1866 Lepidophloios obcordatus Lesquereux, p. 457, pl. XLI, figs. 1, 2 (acc. to Kidston 1886).

- p 1884 Lepidophloios dilatatus Lesquereux, pl. CV, fig. 4; non pp. 781–783, pl. CV, fig. 2 (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus Goldenberg); non pl. CV, fig. 1 — this specimen appears to represent a lycopsid strobilus with sporangia and megasporangia), fig. 3 (decorticated).

- p 1897 Lepidophloios Acadianus Dawson, pls I, II; non pp. 63–64, pl. IV, fig. above; non pl. III (stem with attached leaves); non pl. IV below (strobili); non pl. V (stems with branch scars); non pl. VI (transverse sections); non pl. VII (poorly preserved stems with branch scars); non pl. VIII (poorly presrved stem with branch scars).

- p 1899 Lepidophloios Van Ingeni White, pl. LVI, figs. 1–2b; non pp. 205–210, pl. LVI, figs. 3–8 (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. LVII, figs. 1, 1a (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. LXI, fig. 1c (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. LXII, fig. f (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. LXIII, fig. 5 (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. LVIII, fig. 1 (leafy branches).

- 1937 Lepidophloios laricinus, Jongmans, p. 400, pl. 16, fig. 29.

- 1938 Lepidophloios laricinus, Bell, p. 102, pl. CI, fig. 4.

- 1940 Lepidophloios laricinus, Bell, p. 126, pl. VIII, figs. 3, 4.

- 1940 Lepidophloios laricinus, Janssen, pp. 20–21, pl. III, fig. 3 (photograph of the holotype of Lepidophloios obcordatus).

- v p 1944 Lepidophloios laricinus, Bell, pp. 93–94, pl. L, fig. 1; pl. LVI, fig. 1 (upside down); pl. LVIII, fig. 1, fig. 4 (refigured here as Fig. 8g); pl. LXI, fig. 1 (refigured here as Fig. 7); non pl. LVII, fig. 4 (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. LVIII, fig. 3 (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus — figured also by Bell 1966, pl. VIII, fig. 2); non pl. LX, fig. 5 (stem with ulodendroid branch scar).

- 1957 Lepidophloios laricinus, Janssen, pp. 47–48, fig. 26.

- 1957 Ulodendron or Lepidophloios, Janssen, p. 52, fig. 32 (upside down).

- 1958 Lepidophloios laricinus, Langford, p. 78, fig. 132 (poorly figured).

- 1959 Lepidophloios laricinus, Canright, p. 20, 28, pl. 1, fig. 13 (poorly preserved).

- v p1966 Lepidophloios laricinus, Bell, pl. XXVIII, fig. 4 (terminal part of branch with attached leaves); non pl. VIII, fig. 2 (= Lepidophloios macrolepidotus); non pl. XII, fig. 1 (forma Halonia tortuosa — decorticated stem with halonial scars).

- 1968 Lepidophloios van-ingeni, Basson, pp. 46–48, pl. 2, fig. 4.

- 1974 Lepidophloios laricinus, Tidwell et al., pp. 132–134, pl. 3, fig. 2.

- 1974 Lepidophloios cf. larcinus, Jennings, p. 462, pl. 1, fig. 3 (as Lepidophloios sp. in plate explanation).

- 1975 Lepidophloios cf. L. laricinus, Boneham, p. 96, pl. 1, fig. 2 (upside down).

- ? 1977 Lepidophylloides laricinus (sic), Gastaldo, p. 136 (assigned to Lepidophloios in text), fig. 9 (poorly figured).

- k 1977 Lepidophloios laricinus, Thomas, pp. 275–278, pl. 33, fig. 3, figs. 4–6 (cuticles); pl. 34, figs. 1–3 (cuticles); text-figs. 2–3A-F.

- 1978 Lepidophloios laricinus, Gillespie et al., p. 47, 52, pl. 16, fig. 1, fig. 6 (with Halonia strobilar scars).

- 1980 Lepidophloios laricinus, Jennings, p. 150, pl. 1, fig. 1.

- p 1980 Lepidophloios laricinus, Zodrow and McCandlish, p. 82, pl. 123, fig. 3; non pl. 123, fig. 2 (decorticated); non pl. 124, fig. 1 (= Diaphorodendron decurtatum).

- 1985 Lepidophloios laricinus, Gillespie and Rheams, p. 194, 200, 201, pl. III, fig. 7, fig. 8 (? — long leaves).

- 1985 Lepidophloios cf. laricinus, Lyons et al., p. 212, 220, 238, pl. IV, fig. D.

- 1985 Lepidophloios laricinus, Gillespie and Crawford, p. 250, 252, pl. I, fig. 5.

- 1989 Lepidophloios laricinus, Gillespie et al., p. 5, pl. 1, fig. 12.

- T 1992 Lepidodendron laricinum, Kvaček and Kvaček, Tab. I, fig. 2 (photograph of part of specimen illustrated by Sternberg 1820, Taf. XI, fig. 2).

- p 1996 Lepidophloios laricinus, Cross et al., p. 403, fig. 23-4.4; non fig. 23-4.3 (to be compared with Lepidophloios acerosus Lindley and Hutton).

- T 1997 Lepidofloyos laricinum, Kvaček and Straková, pp. 93–94, pl. 29 (photograph of specimen in Sternberg 1820, Taf. XI, fig. 3); pl. 31 (Sternberg 1820, Taf. XI, fig. 2).

- 2005 Lepidophloios laricinus, Dilcher et al., p. 157, figs. 1.5–1.7.

- 2005 Lepidophloios laricinus, Dilcher and Lott, pl. 118, fig. 1, fig. 2 (decorticated), fig. 3; pl. 119, fig. 1 (same as Dilcher et al. 2005, fig. 1.5), fig. 3, fig. 4 (poorly preserved).

- ? 2006 cf. Lepidophloios laricinus, Calder et al., p. 180, 182, fig. 10D (difficult to judge from illustration).

- 2006 Lepidophloios sp., Wittry, p. 109, figs. 1, 2; fig. 3 (same as Janssen 1957, fig. 32).

- 1968 Lepidophloios larcinus (sic), Abbott, p. 9, pl. 12, fig. 6 (sketch of Sigillaria brardii); pl. 19, fig. 4 (= Sigillaria brardii).

Display large image of Figure 7

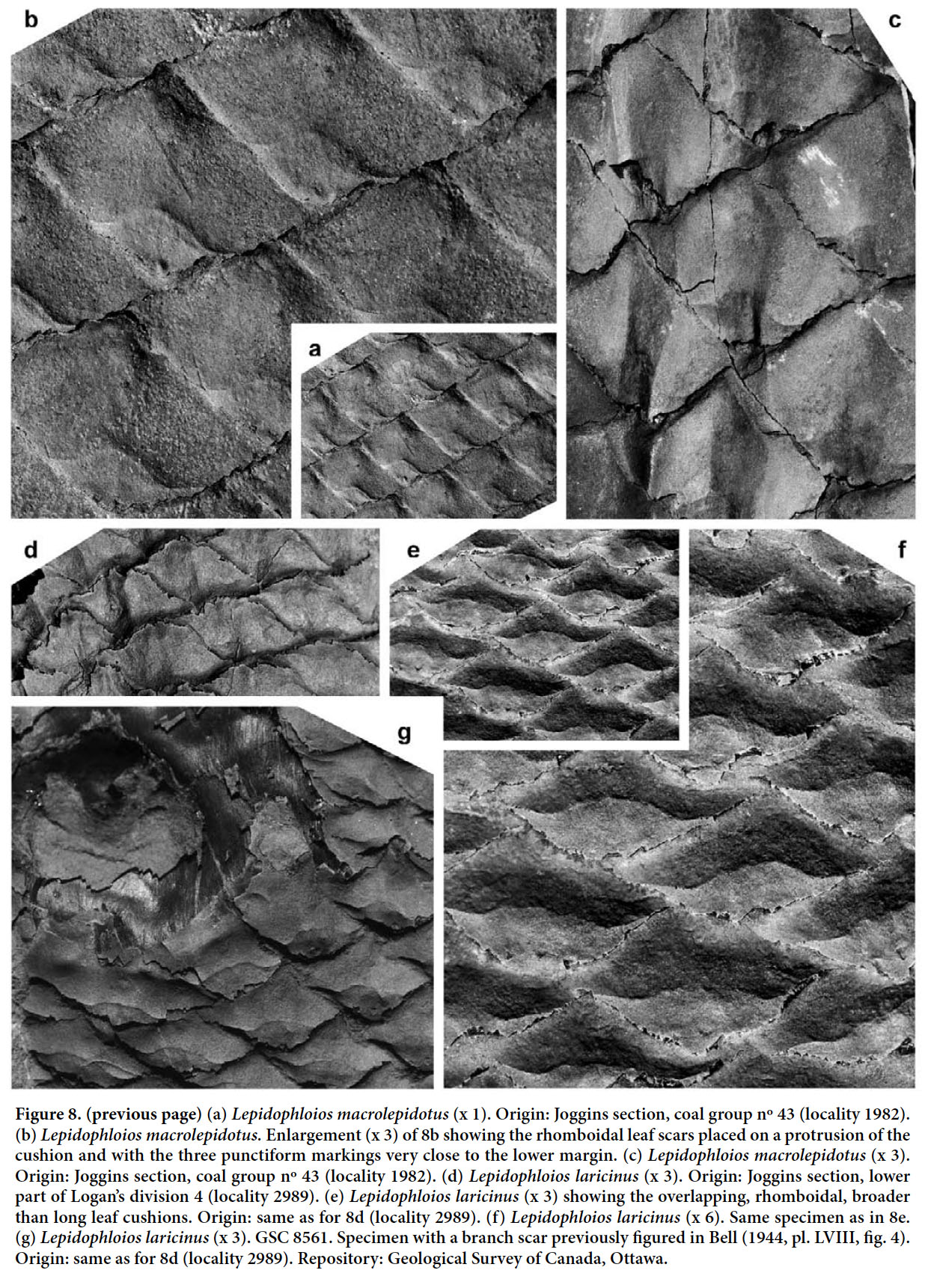

Display large image of Figure 751 DESCRIPTION. Leaf cushions overlapping, rhomboidal in outline, much broader than long, with acute lateral angles, obtuse upper angle, and a rounded lower angle. Keel absent. Dimensions: 4–5 mm long and 6–10 mm broad; ratio = 0.5–0.6. Leaf scars occurring near the cushion apex, strongly protruding and squashed downwards on compression, transversely rhomboidal, elongate, with lateral angles very sharp and the upper and lower angles rounded, occupying approximately one third of cushion area. Dimensions: 2–3.5 mm long and 3–7 mm broad. In its lower part, the leaf scar bears three small rounded markings in line; only the central, larger cicatricule (vascular trace) is clearly visible in the leaf scar.

52 REMARKS. Bell (1944) figured several specimens from the Cumberland Basin as Lepidophloios laricinus, but two different species seem to be represented. One is characterized by the small leaf cushions and scars of Lepidophloios laricinus, whereas the other displays larger leaf cushions similar to those of Lepidophloios acadianus (a synonym of Lepidophloios macrolepidotus — see later). Bell (1944, 1966) also figured several specimens with ulodendroid and halonial (branch and strobilar) scars. Specimen GSC 4503 (Bell 1944, pl. LXI, fig. 1 — refigured here in Fig. 7) is a stem fragment with subcircular scars in a helicoidal pattern. It has transversely elongate leaf cushions, thus allowing its identification as Lepidophloios. This specimen is only slightly flattened, preserving most of its three dimensional aspect and thus allowing the helicoidal pattern of scars to be followed around the branch. These subcircular scars are set on protuberances. This is the Halonia condition that Jonker (1976), following Renier (1910), interpreted as slight elevations of cortical tissue supporting pedunculate strobili. This interpretation agrees with the reconstruction by Hirmer (1927, fig. 263). A central depression on the subcircular protuberance would mark the place of insertion of the strobilar stalk. Bell (1966, pl. XII, fig. 1) figured a similar specimen with halonial scars, but more poorly preserved. Both the latter specimen and the one figured here are from the same locality (1388) at Joggins.

A different, larger kind of scar of more elliptical shape and forming a depression on large branches or stems is exemplified by the negative print of a branch surface as figured by Bell (1944, pl. LVIII, fig. 4 — refigured here in Fig. 8 g). This kind of scar was interpreted by Renier (1910) and Jonker (1976) as corresponding to an adventitious branch. Adventitious branch scars seem uncommon, but they have been found on several different kinds of lycopsid stems, e.g., on Bothrodendron (Crookall 1964, pl. LXXIII, fig. 5) and Bergeria (Kidston 1893, pl. III, fig. 9, fig. 10, as Lepidodendron landsburgii — refigured as Lepidodendron ophiurus by Crookall 1964, pl. LXIII, fig. 1), as well as in Lepidophloios.

Some of the stem remains with ulodendroid scars are not clearly identifiable as Lepidophloios laricinus. For instance, specimen GSC 8556 (Bell 1944, pl. LX, fig. 5), which is unidentifiable either generically or specifically (see later), is a decorticated, poorly preserved stem fragment with rhomboidal leaf cushions, longer than wide, and an ulodendroid branch scar.

53 COMPARISONS. The leaf cushions of Lepidophloios macrolepidotus are much larger, up to four times the size of those of Lepidophloios laricinus. Also, the leaf cushions of Lepidophloios macrolepidotus are more equidimensional and do not protrude as much as those of Lepidophloios laricinus. The leaf scars of Lepidophloios macrolepidotus are more rhomboidal and occur at the extreme base of cushions. Moreover, the ligule pit in Lepidophloios macrolepidotus is more clearly separate from the leaf scar. According to Thomas (1977), the stomatal frequencies also differ, with 250 per mm2 in Lepidophloios laricinus and 130 per mm2 in cuticle preparations of material from the Joggins section. Thomas attributed the latter material to Lepidophloios acadianus (a synonym of Lepidophloios macrolepidotus).

Lepidophloios acerosus also possesses small, rhomboidal leaf cushions, but these are longer than broad, with a distinct keel (a feature absent in Lepidophloios laricinus); also its ligule pit occurs immediately above the leaf scar (in contrast to 1–1.5 mm above the leaf scar in Lepidophloios laricinus). According to Thomas (1977, p. 284), the cuticles of these two species are also different.

54 STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. Lepidophloios laricinus is quite common in Westphalian strata. It has been reported most often from the Langsettian and Duckmantian substages, and much more rarely from the (upper) Namurian (fide Crookall 1964). The type material is from the Radnice Member, Kladno Formation in Bohemia, of Bolsovian age. According to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2010), this species ranges from Langsettian to Cantabrian in the Iberian Peninsula, a longer range than is commonly accepted.

55 OCCURRENCE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES, CANADA. Cumberland Basin (Nova Scotia): Dawson (1897). Bell (1944): locality 636 (GSC 8601); locality 1045 (GSC 8567 + one piece without number with cf.); locality 1386 (one piece without catalogue number); locality 1388 = 2990 (GSC 4503); locality 1982 (three pieces without catalogue number); locality 2989 (GSC 8561 + three pieces without catalogue number). Bell (1966): locality 1388 = 2990 (GSC 14930). Zodrow and McCandlish (1980). Minas Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 77 (GSC 8216). Sydney Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1938): locality 498 (GSC 3373). Bell (1966): locality 1331 (GSC 14935). Minto Coalfield (Nova Scotia): Bell (1940): locality 2656 (GSC 10360); locality 2746 (GSC 10364).

56 OCCURRENCE IN THE UNITED STATES. Alabama: Gillespie and Rheams (1985), Lyons et al. (1985), Dilcher and Lott (2005), Dilcher et al. (2005). Colorado: Jennings (1980). Georgia: Gillespie and Crawford (1985), Gillespie et al. (1989). Illinois: Lesquereux (1866), Janssen (1940, 1957), Langford (1958), Jennings (1974), Boneham (1975), Gastaldo (1977), Wittry (2006). Indiana: Canright (1959). Missouri: White (1899), Basson (1968). Ohio: Cross et al. (1996). Utah: Tidwell et al. (1974). West Virginia: Jongmans (1937), Gillespie et al. (1978).

Lepidophloios macrolepidotus Goldenberg 1862 (Figs. 8a–c)

- 1855 Lomatophloyos macrolepidotum Goldenberg, p. 22 (nomen nudum).

- * 1862 Lepidophloios macrolepidotum Goldenberg, pp. 37–40, Taf. 14, fig. 25 (upside down) (as Lomatophloyos macrolepidotum in plate explanation).

- * 1862 Lomatophloios intermedium Goldenberg, pp. 28–29, Taf. XV, figs. 3, 4.

- p 1862 Lepidophloios laricinum, Goldenberg, Taf. XVI, fig. 1; non Taf. XVI, figs. 2–6A (= Lepidophloios laricinus), fig. 7 (strobili), fig. 8 (Cyperites-type leaves).

- *p 1868 Lepidophloios Acadianus Dawson, p. 489, text-fig. 171B, M (sketch of a leaf cushion); non text-fig. 171A (reconstruction), figs. C–E (branch with halonial scars), fig. F (strobilus), fig. G (leaf), figs. H–L (cross section).

- * 1870 Lepidophloios? auriculatum Lesquereux, p. 439, pl. XXX, fig. 1 (upside down).

- 1879–80 Lepidophloios macrolepidotus, Lesquereux, p. 424, pl. LXVIII, fig. 2 (upside down).

- 1879–80 Lepidophloios auriculatus, Lesquereux, pp. 421–422, pl. LXVIII, fig. 3 (same as Lesquereux, 1870, pl. XXX, fig. 1), fig. 4.

- *p 1884 Lepidophloios dilatatus Lesquereux, pp. 781–783, pl. CV, fig. 2; non pl. CV, fig. 1 (indeterminable strobilar fragment of lycopsid with sporangia and megaspores — possibly attributable to Omphalophloios?), fig. 3 (decorticated), fig. 4 (= Lepidophloios laricinus).

- p 1897 Lepidophloios Acadianus Dawson, pp. 63–64, pl. IV, fig. above; non pls I, II (= Lepidophloios laricinus); non pl. III (stem with attached leaves); non pl. IV lower part (strobili); non pl. V (stems with branch scars); non pl. VI (cross sections); non pl. VII (poorly preserved stems with branch scars); non pl. VIII (poorly preserved stem with branch scars).

- * p 1899 Lepidophloios Van Ingeni White, pp. 205–210, pl. LVI, figs. 3–8; pl. LVII, figs. 1, 1a; pl. LXI, fig. 1c; pl. LXII, fig. f; pl. LXIII, fig. 5; non pl. LVI, figs. 1–2b (= Lepidophloios laricinus); non pl. LVIII, fig. 1 (small branches with attached leaves).

- v p 1944 Lepidophloios laricinus, Bell, pl. LVII, fig. 4; pl. LVIII, fig. 3; non pp. 93–94, pl. L, fig. 1 (Lepidophloios laricinus); pl. LVI, fig. 1 (Lepidophloios laricinus — upside down); pl. LVIII, fig. 4 (Lepidophloios laricinus); pl. LXI, fig. 1 (Lepidophloios laricinus); non pl. LVIII, fig. 1 (poorly figured but possibly Lepidophloios laricinus); non pl. LX, fig. 5 (ulodendroid branch scar).

- 1959 Lepidophloios macrolepidotus, Remy and Remy, p. 103, Abb. 81.

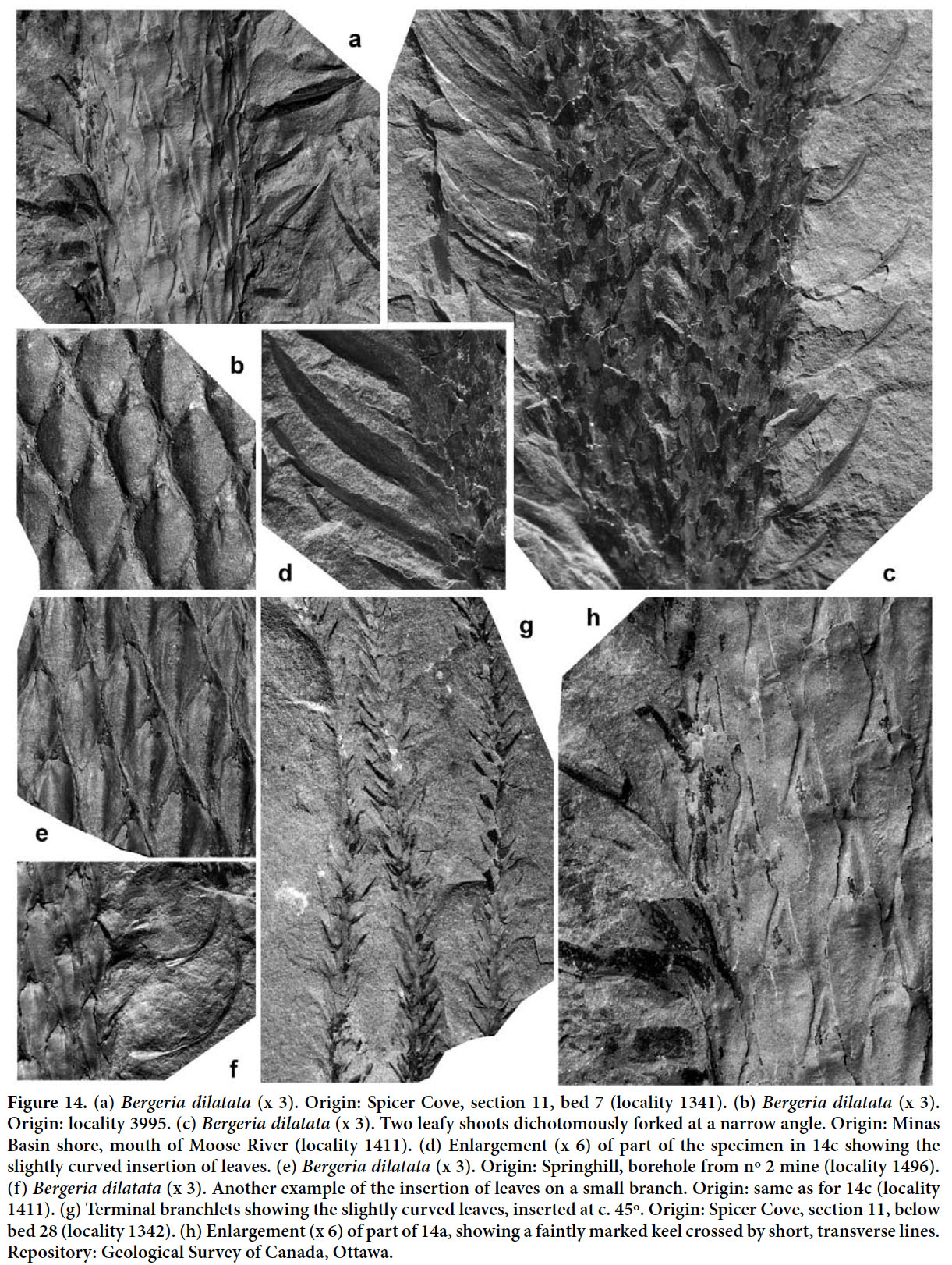

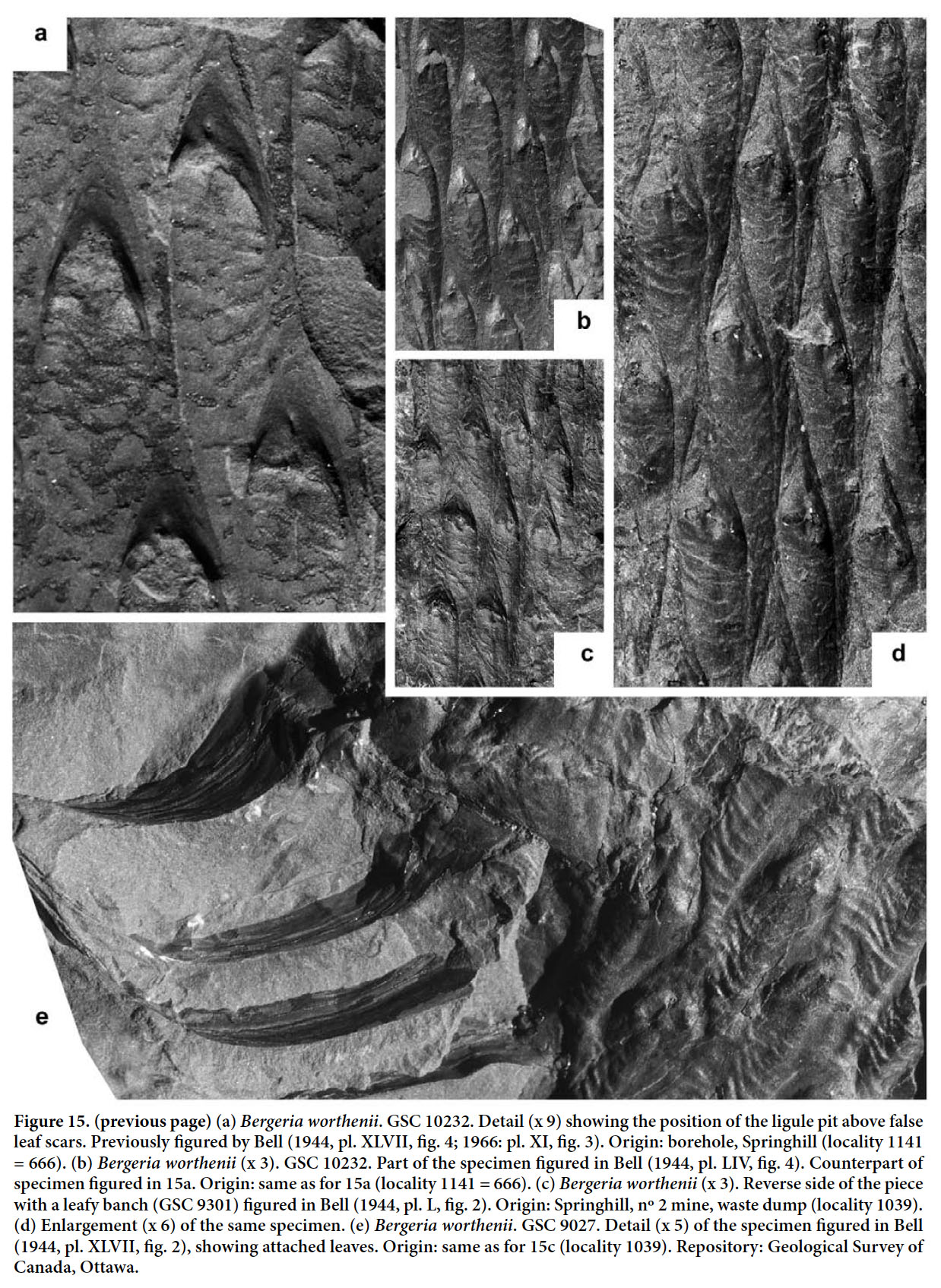

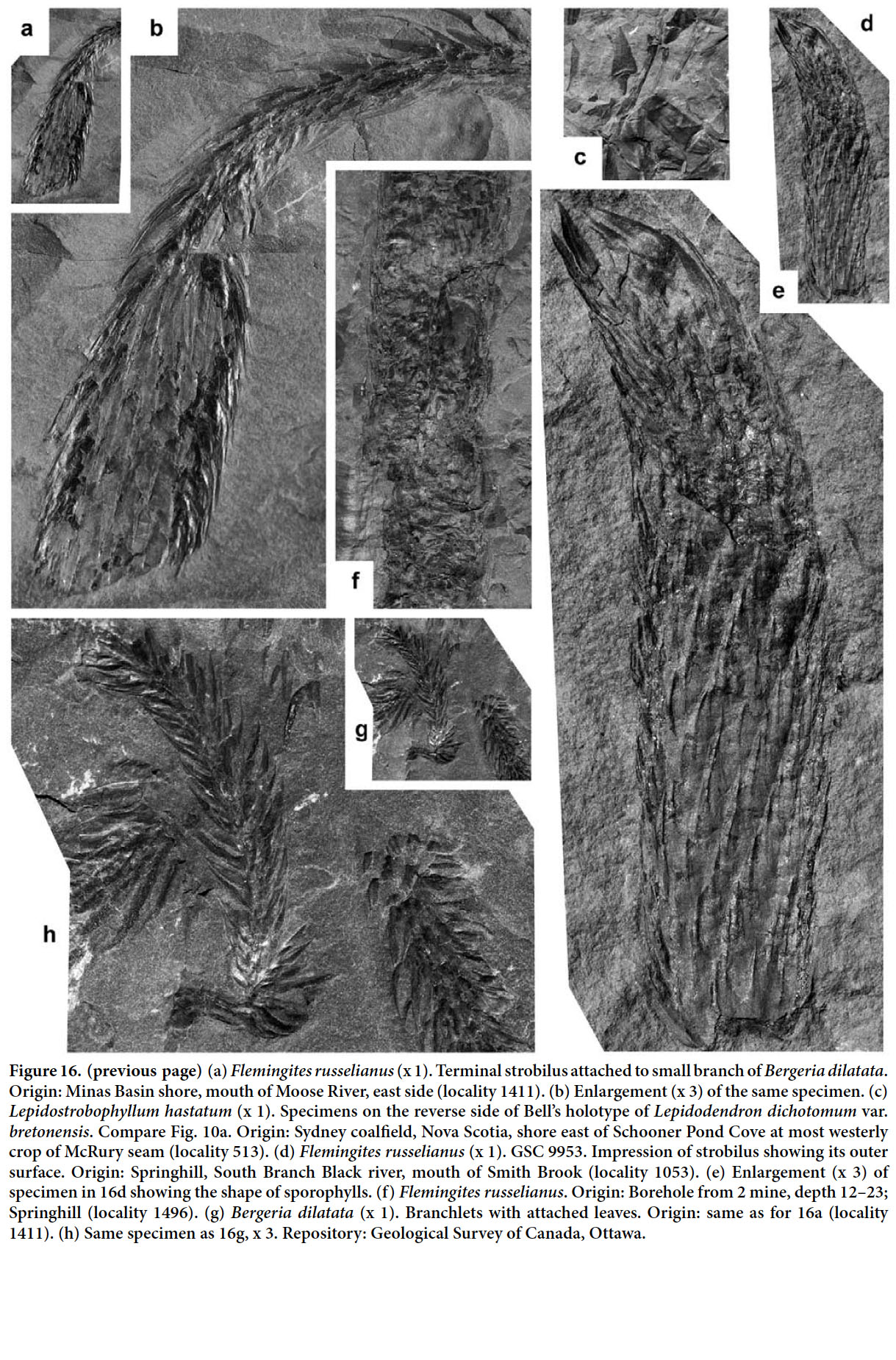

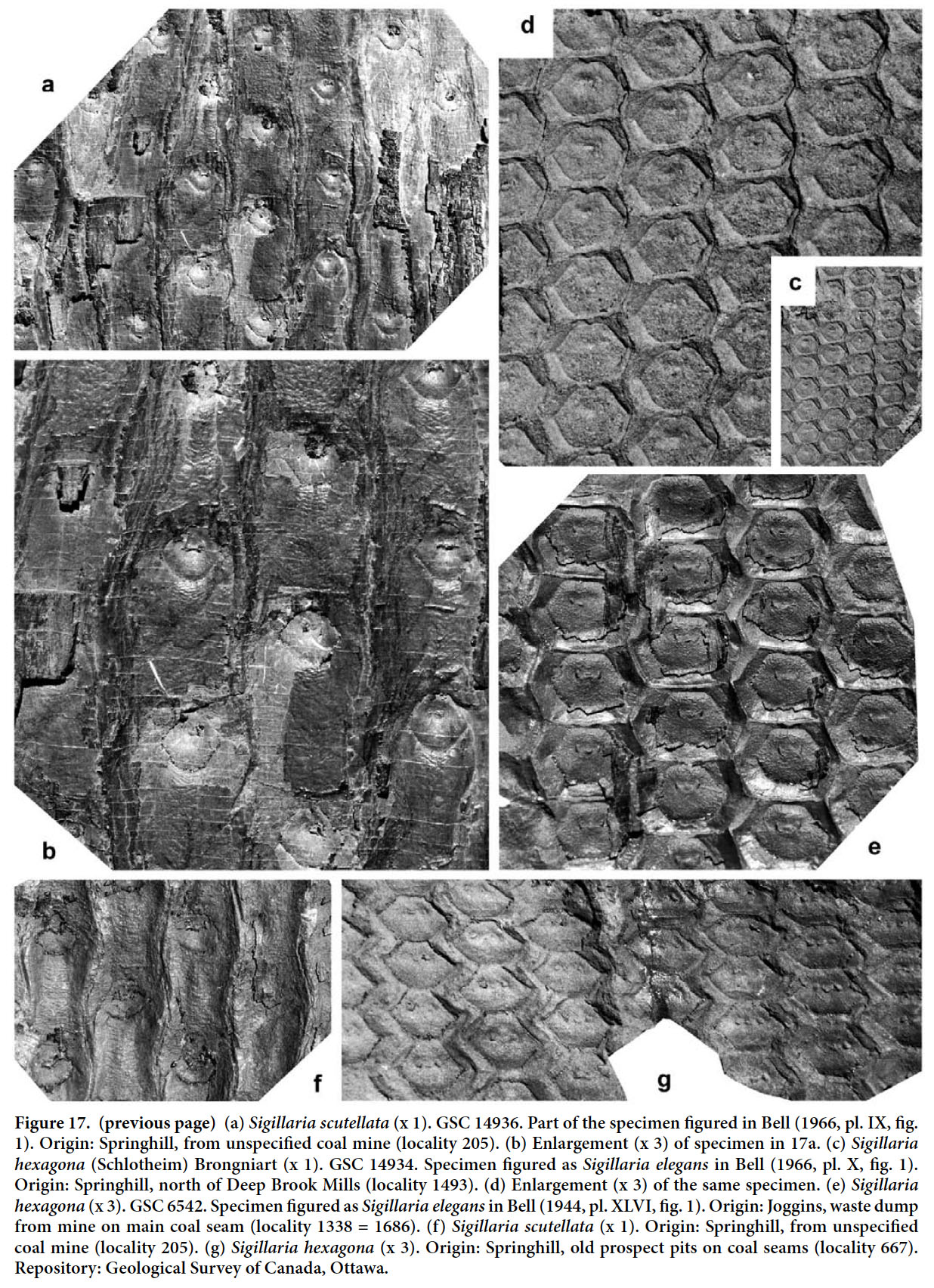

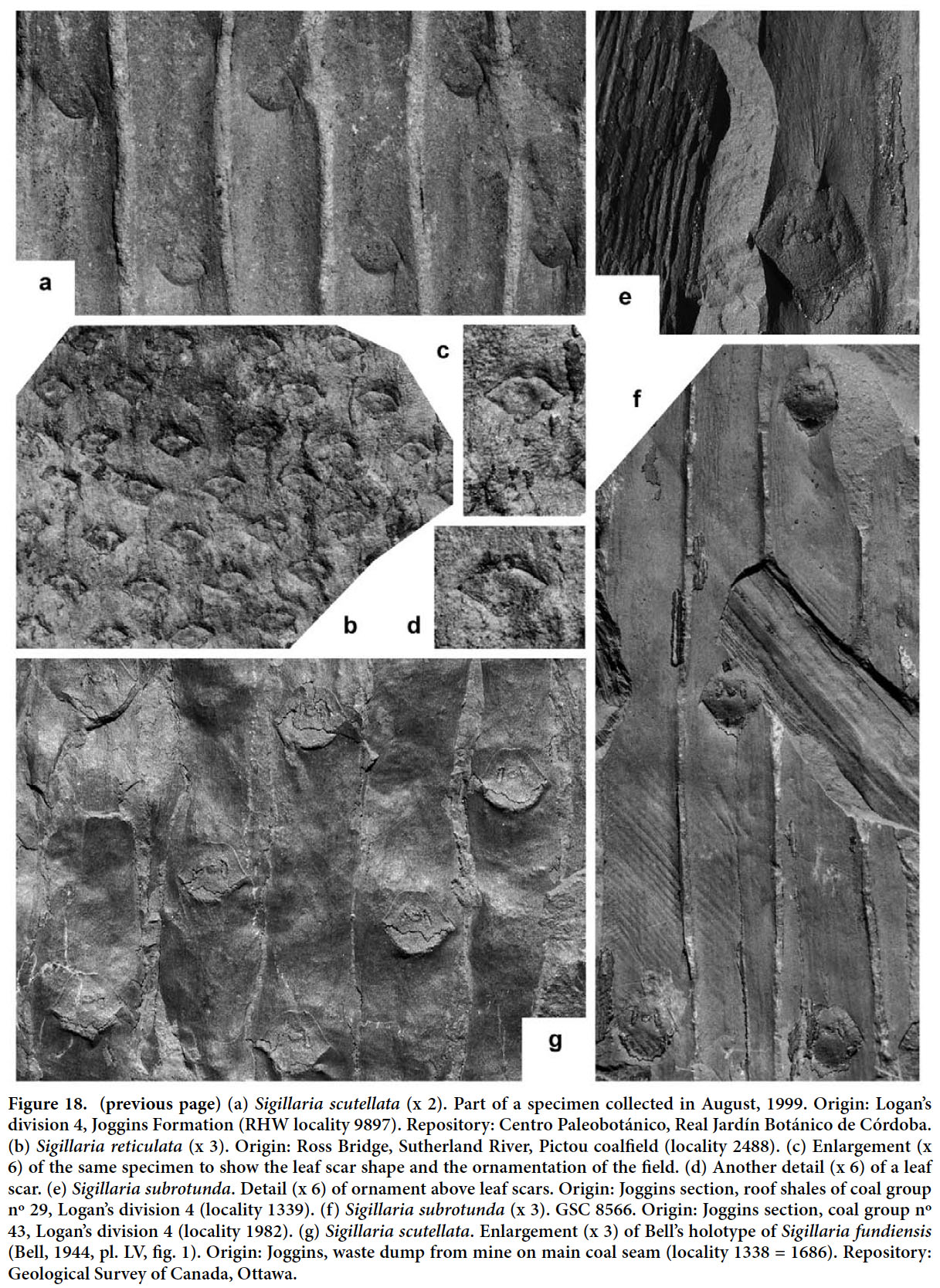

- p 1964 Lepidophloios laricinus, Crookall, pl. LXXVIII, fig. 1 (upside down); pl. LXXIV, fig. 6 (? — poorly preserved); non pp. 307–313, pl. LXXIV, fig. 2 (strobili), figs. 3–5 (poorly figured); non pl. LXXV, fig. 6 (Lepidophloios laricinus); non pl. LXXVIII, fig. 6 (upside down — Lepidophloios laricinus); non text-figs. 98 (copy of one of Sternberg’s 1820 syntypes), 100c (drawing).