Article

Investigation of Sheriff Stuart’s black granite quarries in Charlotte County, southwestern New Brunswick, Canada:

implications for the source of the Titanic headstones in Halifax, Nova Scotia

doi: 10.4138/atlgeol.2020.008

Abstract

Robert Albert Stuart, the High Sheriff of Charlotte County, deserves credit for establishing the black granite monument industry in New Brunswick. In the late 19th to early 20th centuries, he opened three quarries in mafic plutonic rocks in the vicinity of the Chickahominy Mountain, north of St. Andrews: the Bocabec black granite quarry (1893), the Steen Lake black granite quarry (1895), and the Glenelg porphyry quarry (1906). Much of the information in brief articles in local newspapers lacks sufficient detail to gain a full understanding of the historical development of these quarries. To obtain a clearer timeline for production of stone from the quarries, the rock type in each was examined and compared to black granite monuments in nearby cemeteries known to be sourced from these specific quarries. Previous investigations did not entirely rule out the possibility that the Stuart quarries may have been a source for the headstones placed in the Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to mark the graves of some of those who were lost when the Titanic sank in 1912. Our detailed analysis of rock textures and production histories leads us to conclude that none of the Stuart quarries could have been a source for the Titanic headstones and supports the previous assessment that they came from Charles Hanson quarry.

Résumé

Robert Albert Stuart, haut-shérif du comté de Charlotte, mérite d’être reconnu comme celui qui implanté l’industrie des monuments en granite noir au Nouveau-Brunswick. Vers la fin du 19e siècle et le début du 20e, il a ouvert trois carrières dans des roches plutoniques mafiques des environs du mont Chickahominy, au nord de St. Andrews : la carrière de granite noir de Bocabec (1893), la carrière de granite noir du lac Steen (1895) et la carrière de porphyre de Glenelg (1906). La vaste part des renseignements fournis dans les brefs articles parus dans les journaux locaux ne fournit pas suffisamment de détails pour permettre une compréhension complète de la mise en valeur passée de ces carrières. Pour obtenir des données chronologiques plus claires sur la production de la pierre provenant des carrières, nous avons examiné le lithotype de chacune et l’avons comparé aux monuments en granite noir dans les cimetières voisins que nous savons alimentés de ces carrières particulières. Les études antérieures n’avaient pas entièrement éliminé la possibilité que les carrières de Stuart pouvaient avoir constituer une source des stèles funéraires placées dans le cimetière Fairview Lawn à Halifax , Nouvelle-Écosse, pour marquer les fosses de certains des passagers qui avaient disparu lorsque le Titanic a sombré en 1912. Notre analyse détaillée des textures des roches et des historiques de production nous amène à conclure qu’aucune des carrières de Stuart n’a pu constituer une source des stèles du Titanic et elle appuie l’évaluation antérieure qu’elles provenaient de la carrière de Charles Hanson.

[Traduit par la redaction]

INTRODUCTION

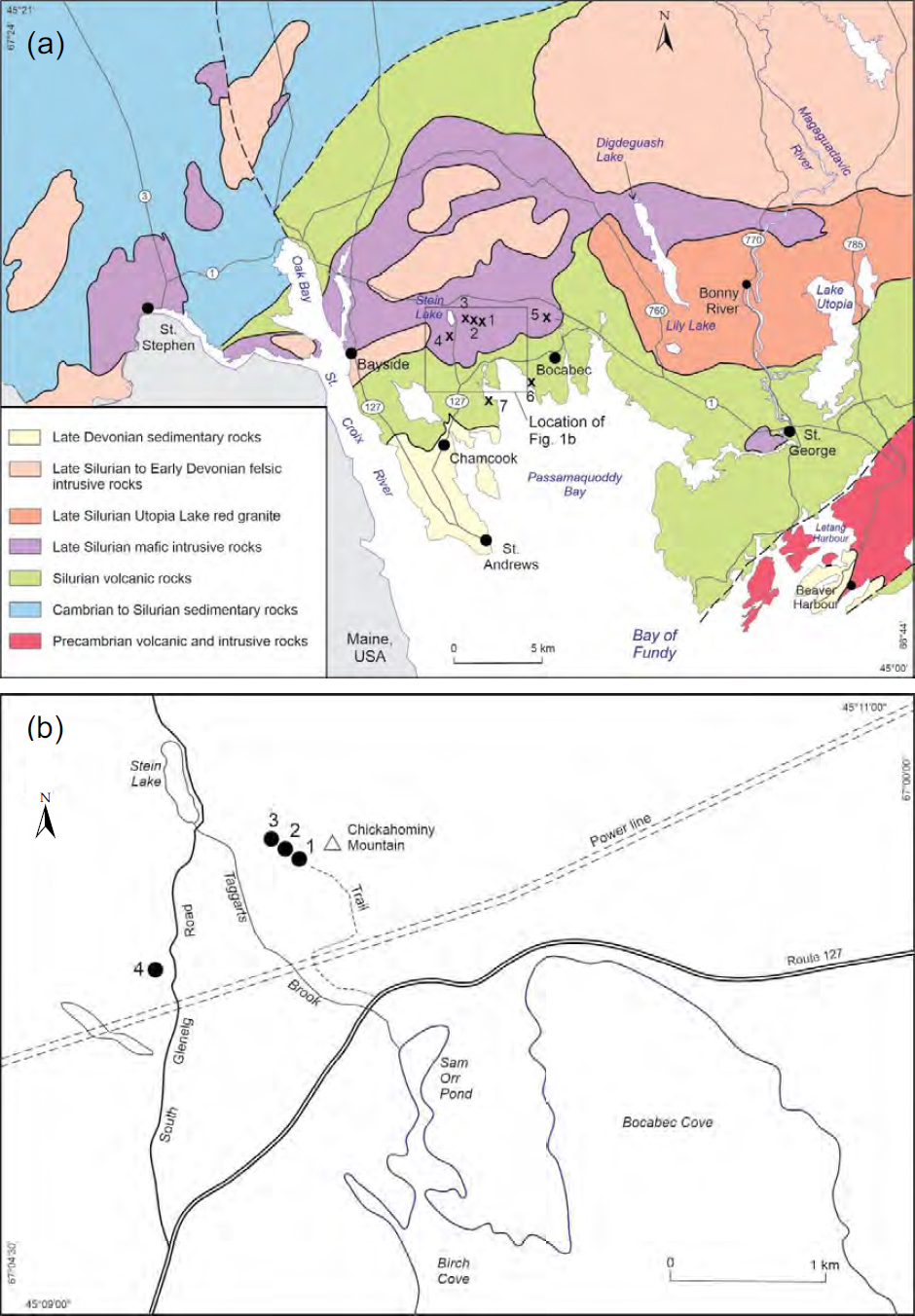

1 Little has been written about the development of the black granite industry in Charlotte County, southwestern New Brunswick (Fig. 1a), in comparison to that of the well-documented red granite industry (Martin 2013, and references therein). Such was the importance of red granite production to the region, that St. George became known as ‘Granite Town’. In 1873, two granite manufacturing companies were incorporated in the St. George District of Charlotte County: the Saint George Red Granite Co. by Peter Cormack from Aberdeenshire, Scotland; and the Bay of Fundy Red Granite Co., by Charles Ward, a Saint John businessman and artist. These were followed by the establishment of several other granite works in the St. George District over the next three decades, including Epps, Dodds & Co. (1883); Tayte, Meating & Co. (1885); Milne, Coutts & Co. (1896), successor to the Bay of Fundy Red Granite Company; and H. McGrattan & Sons (1900). Credit for establishing the black granite (technically known as a gabbro) industry in the Bocabec District belongs to Robert Stuart, the High Sheriff of Charlotte County, who opened his first quarry on Orrs Mountain (now Chickahominy Mountain), northwest of Bocabec (Fig. 1b), in 1893 [St. Andrews Beacon, 19 Oct. 1893] (Gardiner 2015). Stuart’s tireless effort to promote this industry over the following four decades is the subject of this paper. (Note that references to newspaper articles are marked in the text with square brackets and are not included with other references at the end of the paper; these newspaper articles are available on microfilm held in the Charlotte County Archives in St. Andrews and in the Saint John Public Library).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

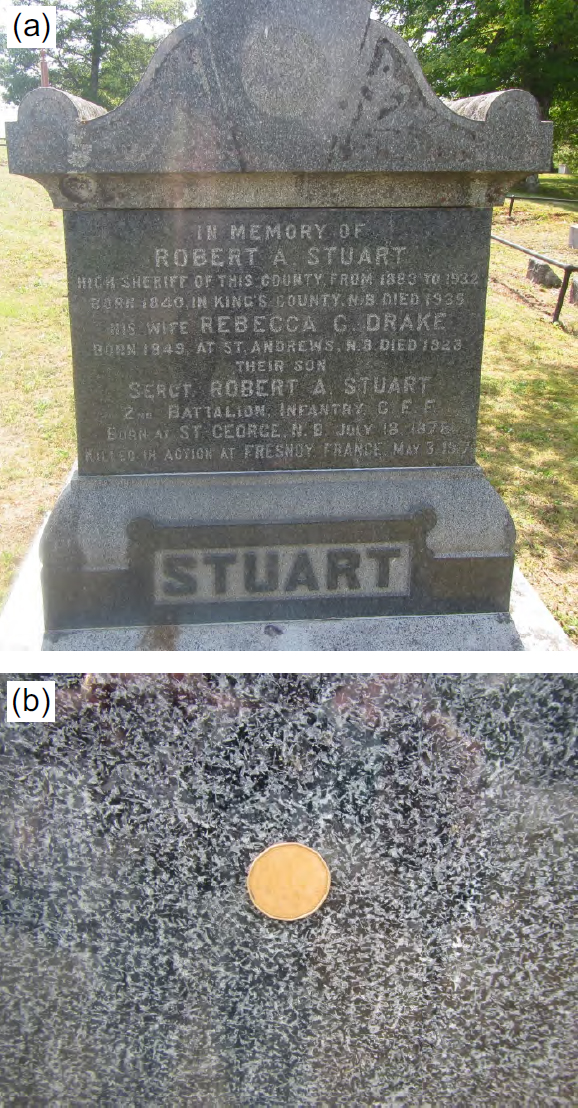

2 Robert Albert Stuart (Fig. 2) was born on the 20th July, 1840 (Canadian Census 1901), to Caleb Stuart and Amy Golding, farmers living in the French Village – Hampton area of Kings County, New Brunswick (Canadian Census 1851). At age 22, Robert’s occupation is listed as a teacher (Canadian Census 1861). Ten years later he is listed as a merchant living in St. George, Charlotte County, New Brunswick (Canadian Census 1871), and married to Rebecca Catherine Drake, daughter of Captain Samuel Drake, a master mariner, and Rebecca C. Brown [St. Croix Courier, 9 Dec. 1869]. Presumably, Stuart’s interest in stone quarries was piqued while living in ‘Granite Town’.

3 Following his appointment as High Sheriff of Charlotte County in 1883, Robert and his family moved from St. George (Canadian Census 1881) to St. Andrews (Canadian Census 1891), where the Charlotte County Court House was located. The retired Sheriff died on the 18th March 1935, at the home of his son, Heber, in Baltimore, Maryland, and his body was returned to New Brunswick for burial in the St. George Rural Cemetery. According to his obituary, he held the position of High Sheriff of Charlotte County from 1883 to 1931 [St. Andrew Courier, 20 March 1935].

4 Quarries owned by Sheriff Stuart include the Bocabec black granite (gabbro) quarry, the Steen Lake black granite (gabbro) quarry on Chickahominy Mountain, and the Glenelg porphyry (diorite) quarry, all located on a 1 kmlong ridge trending west-northwesterly from Chickahominy Mountain to Stein Lake (Fig. 1b). Historical information on the development and operation of these quarries is in geological reports by Parks (1914) and Wright (1934); and in newspaper articles, mainly published in the St. Andrews Beacon and St. Andrews Courier. However, most of these sources tend to be brief and lack details concerning rock composition and location of the quarries. However, some newspaper articles did record the date of placement of headstone monuments in local cemeteries together with the name of the specific quarry from which the black granite was extracted. These well - documented monuments, located in the St. George, St. Andrews, and Chamcook cemeteries, were examined and photographed, to help in deciphering the timeline for the development of individual quarries. One monument manufactured from black granite extracted from the H. McGrattan & Sons Charles Hanson quarry, located north of the community of Bocabec, was examined in this study to compare with those in the vicinity of Chickahominy Mountain (Table 1). It is noted that the term ‘Bocabec’ is associated both with Stuart’s quarry near the peak of Chickahominy Mountain (Quarry No. 1, Fig. 1a) (Table 1, this report) and with the Charles Hanson quarry north of Bocabec (Quarry No. 5, Fig. 1a) (Table 7 of Clarke et al. 2017).

BOCABEC BLACK GRANITE QUARRY

5 Sheriff Stuart’s discovery of a black granite resource on Orrs Mountain was reported in the fall of 1893 [St. Andrews Beacon, 14 Sept. 1893]. Orrs Mountain (now Chickahominy Mountain) is located about 5 km west of Bocabec and about 1 km north of Rte. 127 in Charlotte County, New Brunswick (Quarry No. 1, Fig. 1a, b). Stuart tells the (perhaps apocryphal) story in a later newspaper article, describing how a porcupine played a major role in the unexpected discovery. As summarized here, the Sheriff and his friend, Jeremiah Munn Hanson, had gone hunting in search of game on Orrs Mountain, when they came across a porcupine’s lair among the boulders at the base of a cliff. They were unable to get at the animal so Sheriff Stuart returned a day or two later bringing with him a package of sulphur to be used in an attempt to smoke the porcupine out of its hiding place. However, on making his way to the cliff, Stuart banged his knee on a boulder causing him to suffer considerable pain. Taking revenge on the boulder, he took a swing at it with his axe and recognized immediately that he had broken off a large piece of high quality, black granite [St. Andrews Beacon, 7 Dec. 1883]. Interestingly, Epps, Dodds & Co., in a submission to the St. Andrews Board of Trade regarding opportunities for further development of the black granite industry in Charlotte County, refers to Orrs Mountain as Porcupine Mountain [St. Andrews Beacon, 2 April 1896].

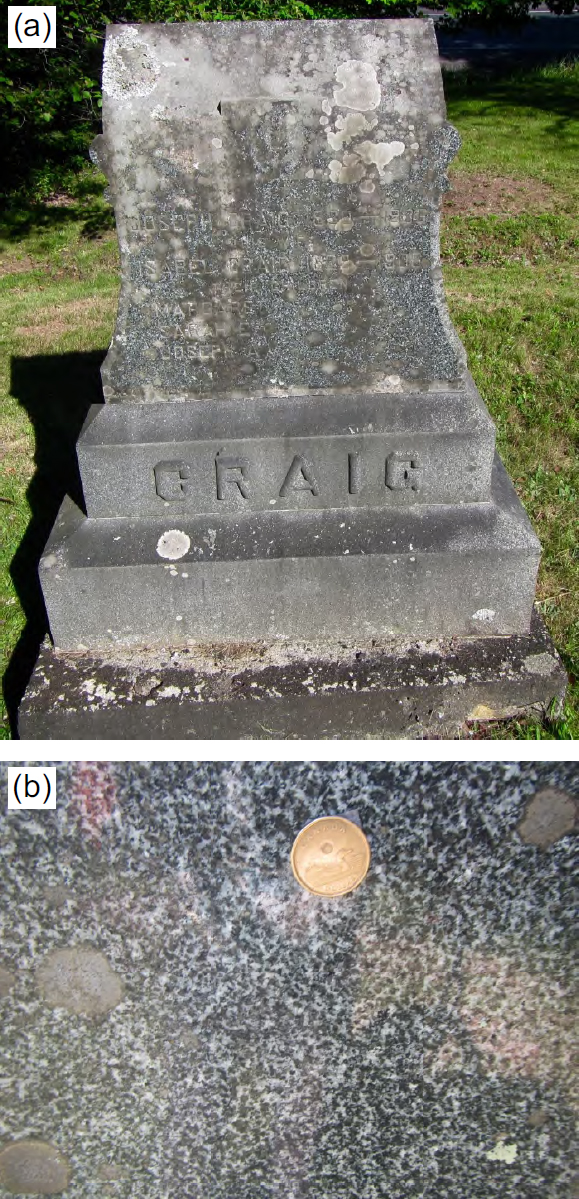

6 A month after his discovery, Sheriff Stuart was acquiring land in the area to develop his quarry [St. Andrews Beacon, 12 Oct. 1893]. He bought that portion of Joseph Craig’s farm, lying to the east of South Glenelg Road (Fig. 1b), which included Orrs Mountain and Steen (now Stein) Lake; and obtained a 99-year lease from Samuel Orr’s heirs for running privileges over their property [St. Andrews Beacon, 7 Dec. 1893]. After showing samples of his black granite around St. George, orders soon came in from Tayte, Meating & Co., and Epps, Dodds & Co., for several tons of the stone [St. Andrews Beacon, 2 Nov. 9, Nov. 1893]. William Gibson, a merchant and lumberman from Benton, Carleton County, had seen a sample of the polished stone, and was very enthusiastic over its possibilities. Gibson was invited by Sheriff Stuart and his friend, Jeremiah Munn Hanson, a shoemaker in St Andrews, to form a partnership to finance development of the Bocabec black granite quarry [St. Andrews Beacon, 7 Dec. 1893]. Plans included laying a tramway to carry the rough stone down the mountainside and to build a wharf so that the stone could be loaded on vessels and taken to St. George for finishing. Each partner contributed $5 000 to the firm to be known as ‘Gibson, Stuart & Hanson’. The period of partnership was for 10 years, extending from the first day of December, 1893, to the first day of December, 1903.

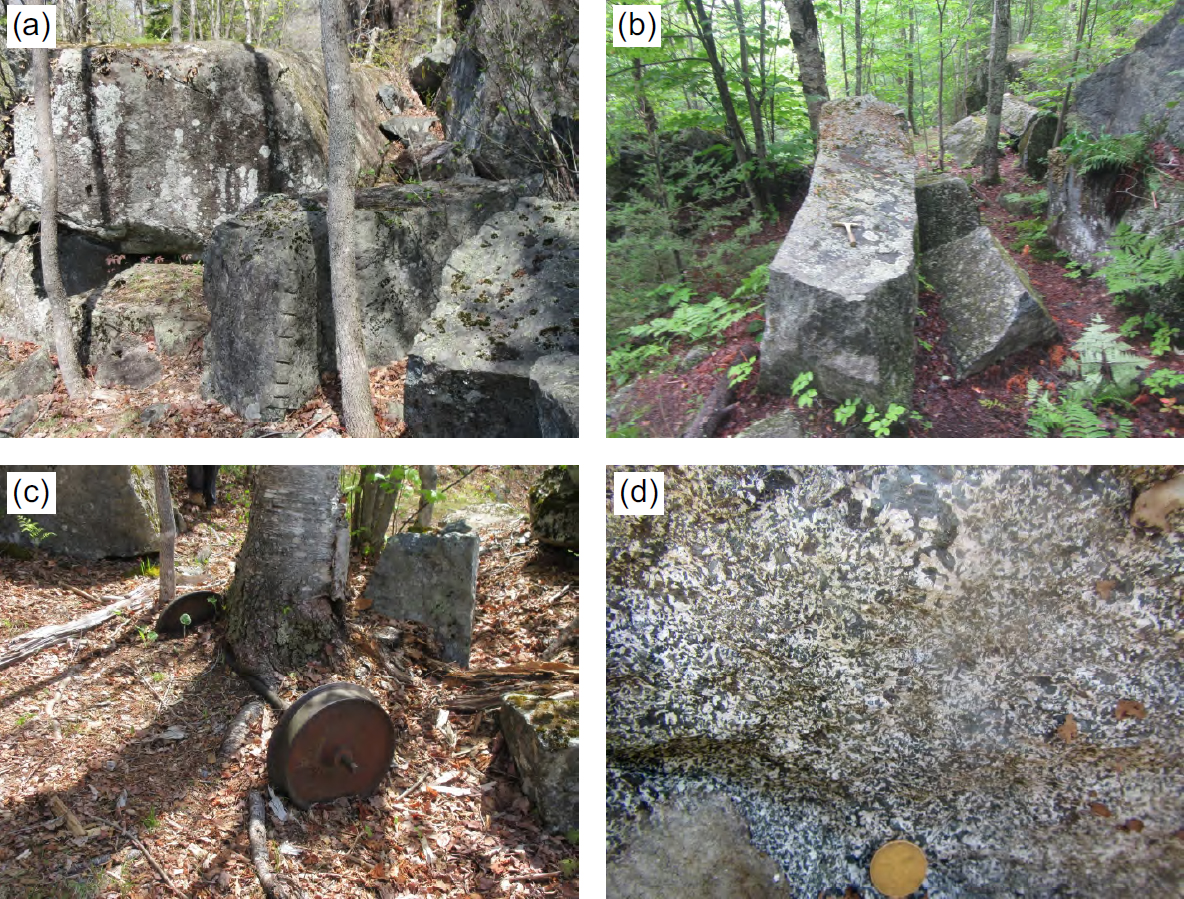

7 By the spring of 1884, the Bocabec black granite quarry owned by Gibson, Stuart & Hanson had been opened (Figs. 3a, b) and a 1 km-long haulage road was constructed up the side of Orrs Mountain from the Saint John road (now Rte. 127). (Today, this haulage road can be accessed from the parking lot at the entrance to the Taggarts Brook nature trail on Rte. 127.) Plans to lay a tramway were soon abandoned (Fig. 3c), presumably because of the cost. A wharf was constructed on Bocabec Cove (No. 6, Fig. 1a) so that the rough stone could be taken by boat to granite works in St. George. A small temporary polisher was set up in Jeremiah Hanson’s shoe factory in St. Andrews to prepare samples and small orders [St. Andrews Beacon, 5 April 10 May 1894]. However, this polishing work was suspended after operating for only two months [St. Andrews Beacon, 26 July 1894].

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

8 The gabbro in the Bocabec quarry displays an ophitic texture of intergrown, randomly oriented, light-coloured plagioclase feldspar largely enclosed in dark-coloured mafic minerals (Fig. 3d). Parks (1914, p. 148) described the mafic minerals in a sample that he collected from the Bocabec quarry in 1911, as mainly unaltered augite. Holt (1968, p. 15) in her memoirs likened the ophitic texture of the gabbro to a snowflake pattern - “The Black Granite is all over this part of Bocabec. The hillside rock in front of my house takes a beautiful black polish with little white flakes like snowflakes, much prettier than Red Granite.” Pegmatitic pods in the ophitic gabbro exposed in the quarry wall are cored by black hornblende (Fig. 3d).

9 In the fall of 1894, the first monument made from Gibson, Stuart & Hanson’s Bocabec black granite was erected in the St. Andrews Rural Cemetery in memory of Claude M. Lamb and his spouse Annie Stevenson [Saint John Daily Sun, 15 Sept. 1894]. It was manufactured and polished by Douglas Bros. of St. Stephen, Charlotte County, and consists of a grey granite base and a black granite (gabbro) pedestal and shaft, with a total height of 12 feet (Fig. 4a). The heterogeneous texture of the Lamb monument (Figs. 4b, c) exhibits scattered pods of very coarse-grained, gabbroic pegmatite in a medium-to-coarse-grained, ophitic gabbro. The heterogeneous texture of this monument matches closely with that of the black granite in the Bocabec quarry on top of Chickahominy Mountain (Fig. 3d), indicating that this quarry is most likely the original discovered by Sheriff Stuart and owned by Gibson, Stuart, & Hanson (Table 1). Another monument in the St. Andrews Cemetery in memory of Reginald, eldest son of Jeremiah M. and Mary Hanson, is made of similar, coarse-grained gabbro (Fig. 5).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

10 Late in 1884, a syndicate, known as the Bocabec Black Granite Co., was formed in Portland Maine, to raise funds towards acquiring and developing Gibson, Stuart & Hanson’s black granite quarry. Company directors were Samuel N. Mayo, banker, and George C. Irvin, both of Boston, Massachusetts, and C. E. Mitchell, real estate capitalist, of Bangor, Maine. Initial capitalization of $250 000 was divided into twenty-five thousand shares of $10 each [St. Andrews Beacon, 22 Nov. 1894]. The Bocabec Black Granite Co. renewed its option with Gibson, Stuart & Hanson in 1895 but was having difficulty raising funds because of the economic depression in the United States [St. Andrews Beacon, 9 May 1885]. A deal to sell the Bocabec Black Granite Co. in 1897 to an American syndicate headed by Hiram Oldershaw of New Britain, Connecticut, apparently did not go through [St. Andrews Beacon, 9 Sept. 25 Nov. 1897].

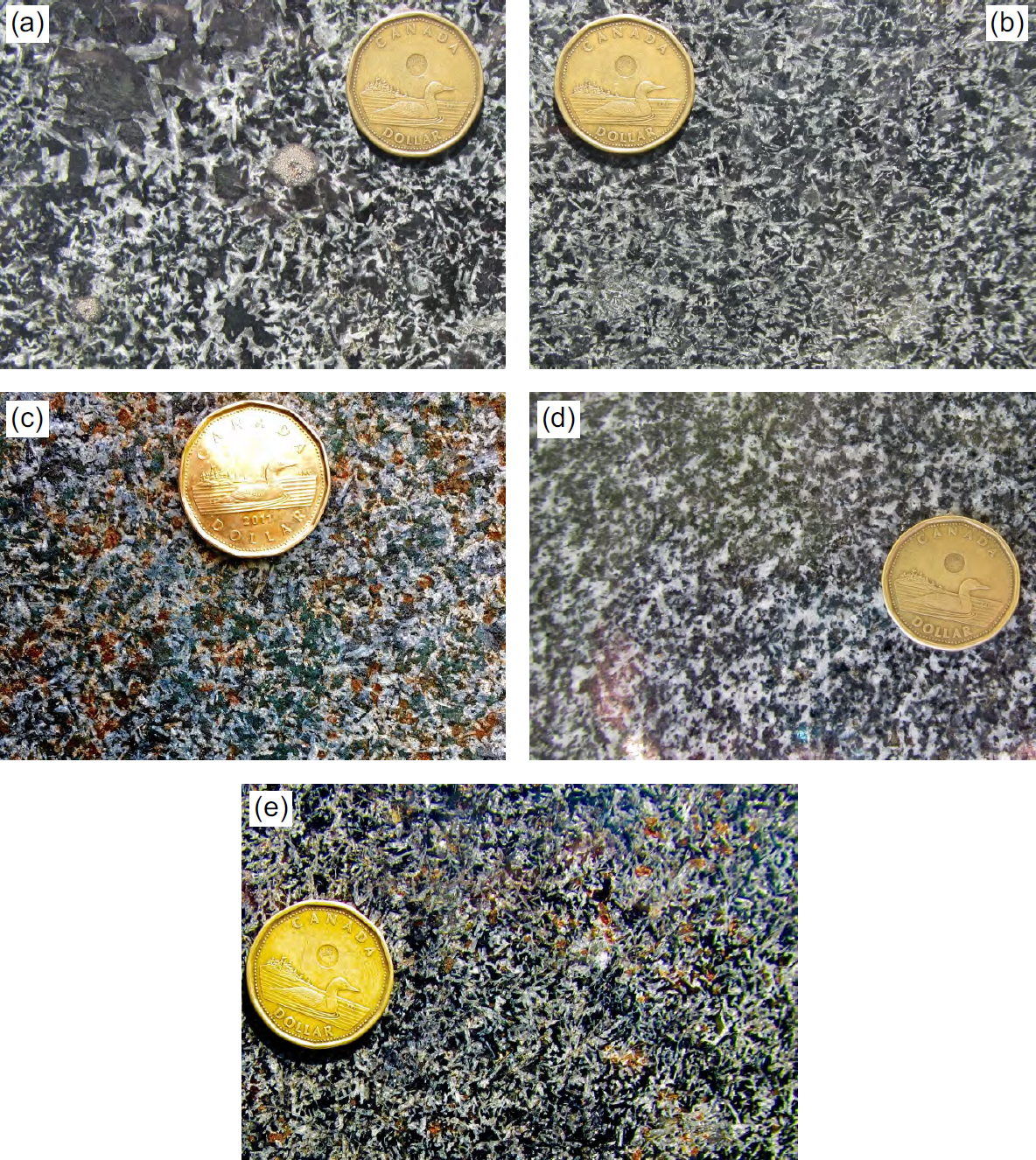

11 The partnership of Gibson, Stuart & Hanson was due to expire at the end of 1903. By this time, Jeremiah Munn Hanson, had sold his shoe store and moved his family to California, where he died in 1918 (Hanson 1918). William Gibson had died in Benton, Carleton County, in 1902 (Fowler 1902), leaving Sheriff Stuart to carry on the quarry business on his own.

STEEN LAKE BLACK GRANITE QUARRY

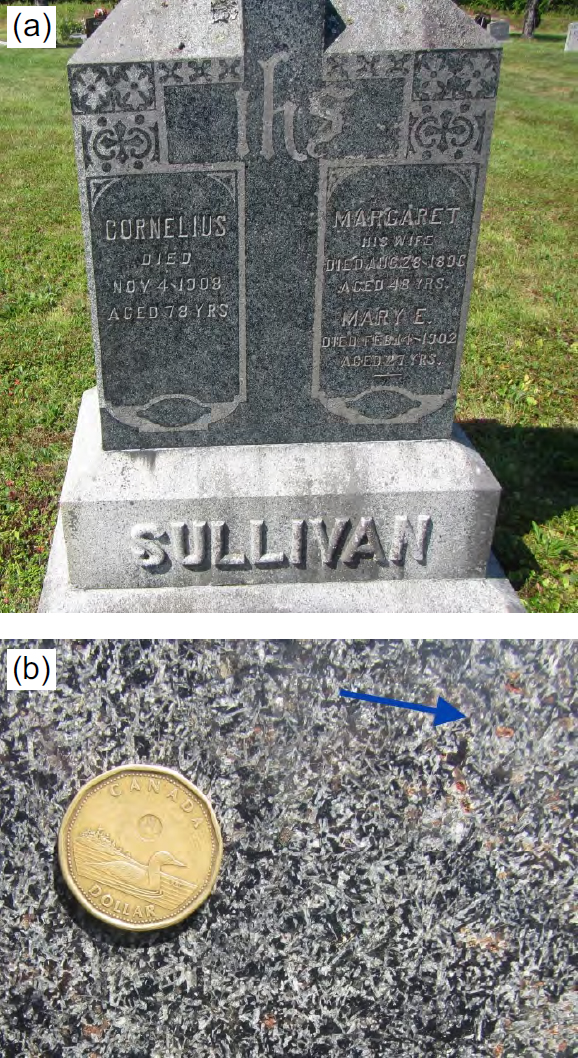

12 Stuart was presumably not happy with the slow progress being made in the development of the Bocabec black granite quarry on Chickahominy Mountain (under option to the Bocabec Black Granite Co.), so R. A. Stuart Co. opened a new quarry (Quarry No. 2, Figs. 1a, b) in the summer of 1895 on the hillside east-southeast of Steen Lake [Saint John Daily Sun, 27 June 1895]. Stein Lake (present-day spelling) is located on the South Glenelg Road about 2.5 km north of its junction with Rte. 127 (Fig. 1b). Note that the Glenelg Road once link St. Andrews to Saint John before being cut off by construction of Hwy 1 and separated into the South and North Glenelg roads (Fig. 1a). The newly opened Steen Lake quarry was accessed from the South Glenelg Road by a haulage road (no longer visible) likely beginning near the south end of Stein Lake [St. Andrews Beacon, 3 Sep. 1896].

13 The exact location of the new Steen Lake black granite quarry is not known with certainty. Parks (1914, p. 146–148) compared a sample of black granite from Stuart’s original Bocabec quarry on Chickahominy Mountain with a sample from the nearby Pine Tree quarry and concluded that “ For all practical purposes the two stones may be regarded as identical”. These samples were collected in 1911 and it is possible that the Pine Tree quarry was the name then being used for the former Steen Lake quarry, which was last active in 1906 (see below). Parks (1914, p. 146) gives the location of the Pine Tree quarry as “Lower on the hillside”, than the Glenelg quarry (Quarry No. 3, Figs. 1a, b). A rubble pile lower on the ridge can be clearly seen on aerial photographs about 100 m west-northwest of the original Bocabec quarry on Chickahominy Mountain (Quarry No. 1, Figs. 1a, b). Examination of this rubble pile during our research showed that the blocks consisted of gabbroic rocks very similar to those in the Bocabec quarry but no evidence was found of actual quarrying at this site during our brief visit. The GPS coordinates given in Table 1 for the Steen Lake quarry (Quarry No. 2, Figs. 1a, b) are from this rubble pile.

14 Tayte, Meating & Co. began taking stone out of the quarry at Steen Lake in the winter of 1895 and transporting it by boat from the wharf on Birch Cove (No. 7, Fig. 1a) to St. George [St. Andrews Beacon, 7 Nov. 1895], where the Steen Lake black granite was made into monuments [Saint John Daily Sun, 7 Dec. 1895]. In the spring of 1896, Epps. Dodds & Co. took stone from the quarry to fill orders they had on hand [St. Andrews Beacon, 21 May 1896]. A derrick was erected in the quarry in the fall of 1896 [St. Andrews Beacon, 1 Oct. 1896]. The following month, Milne, Coutts & Co. had a consignment shipped aboard Captain Marshal Stinson’s boat to their granite works in St. George [St. Andrews Beacon, 19 Nov. 1896]. Twelve tons of black granite were taken from the quarry in the summer of 1897 to be polished in St. George [St. Andrews Beacon, 22 July 1897].

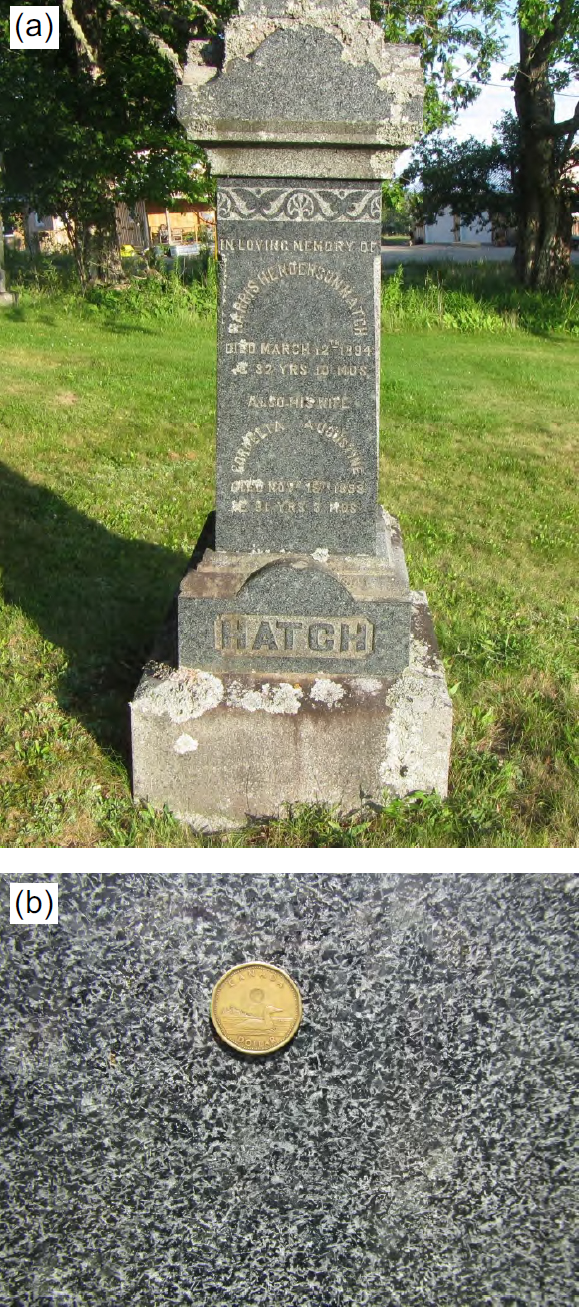

15 Two black granite monuments, known to be taken from the Steen Lake quarry, were erected in the St. George Rural Cemetery in the winter of 1897 (Table 1) [St. Croix Courier, 2 December, 1897]. The monuments, in memory of Harris Henderson Hatch and his spouse (Fig. 6a), and Walter G. Stinson (Fig. 7a), were manufactured by Milne, Coutts & Co. Both monuments are composed of medium-grained, black gabbro exhibiting a uniform ophitic ‘snowflake’ texture, consisting of plagioclase feldspar crystals intergrown with mafic minerals (Figs. 6b, 7b). Pegmatitic pods are absent from these monuments, indicating that the Steen Lake quarry contained more homogeneous stone than the irregularly textured material in the Bocabec black granite quarry at Chickahominy Mountain.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

16 The R. A. Stuart Co. continued to take stone out of the Steen Lake quarry over the next two years to be finished into monuments by Milne, Coutts & Co. [St. Andrews Beacon, 3 November, 1898; Saint John Daily Sun, 26 May 1899]. In 1902, Epps, Dodds & Co. purchased all of the loose stone at the Steen Lake quarry to work into monuments [St. Andrews Beacon, 14 December, 1902], and were still taking stone from there in the spring of 1906 [St. Andrews Beacon, 8 March 1906].

GLENELG PORPHYRY QUARRY

17 In the spring of 1906, Sheriff Stuart gave Epps, Dodds & Co. the right to cut stone in the vicinity of his Steen Lake black granite quarry (Quarry No. 2, Figs. 1a, b). According to an extensive newspaper article “Samples that they (Epps, Dodds & Co.) have cut from the new quarry (Quarry No. 3, Fig. 1), which they have opened near the top of the hill, are of the finest description, the color being uniform and the stone easily worked. A reporter of the Beacon visited the quarry on Monday and noted the operations that were going on. The stone is being taken from a point about a quarter of a mile up the hill from the (South Glenelg) road. A horse-powered derrick has been erected to move the stone as it is cut. The great blocks will be hauled to the wharf a few miles below, and from there shipped to St. George” [St. Andrews Beacon, 22 March 1906]. Later in the summer of 1906, “a sample of polished Glenelg granite” described as a “beautiful black and white mottled stone” was on display in the R. A. Stuart & Son store in St. Andrews [St. Andrews Beacon, 30 Aug. 1906]. Still later, Stuart refers to his “Glenelg greenstone porphyry quarry” [St. Andrews Beacon, 14 Feb. 28 Feb. 1907], suggesting that the new quarry was likely being developed at the site of the ’green and yellow porphyry’ previously discovered by Sheriff Stuart, while prospecting in the vicinity of his Steen Lake quarry [St. Andrews Beacon, 11 Nov. 1897]. By 1908, R. A. Stuart & Son, in a newspaper advertisement, appear to have settled on the trade name Glenelg Porphyry for their product [St. Andrews Beacon, 16 Jan. 1908].

18 Late in 1907, monuments made of Glenelg porphyry were brought to St. Andrews from St. George by Epps, Dodds & Co. to be placed in local cemeteries [St. Andrews Beacon, 21 Nov. 1907]. One of these was erected in the Chamcook Anglican Cemetery in memory of Joseph Craig (Fig. 8a), and another in the St. Andrews Rural Cemetery in memory of Captain John Stinson (Fig. 9a ) (Table 1). In the summer of 1908, R. A. Stuart & Son announced a clearance sale at their clothing and furnishings store so that Sheriff Stuart could devote more time to the development of his Glenelg porphyry quarry [St. Andrews Beacon, 11 June 1908]. Monuments placed in the St. Andrews Rural Cemetery by Epps, Dodds, & Co. in memory of John Pye in 1912 (Fig. 10a), and Captain David Green in 1913 (Fig. 11a), are also of made of Glenelg stone (Figs. 10b, 11b) [St. Andrews Beacon, 24 Oct. 1912; 21 July 1913].

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

19 Several monuments made from Glenelg stone are generally similar in texture and composition, and are quite distinct from the gabbroic rocks taken from Bocabec and Steen Lake quarries. The colour of the Glenelg stone is grey rather than black, crystal shapes are generally poorly developed, the proportion of plagioclase feldspar to mafic minerals is higher, and minor quartz is present (Figs. 8b, 9b, 10b, 11b). Based on their mineral proportions, the four monuments described above from the Chamcook and St. Andrews cemeteries are made up of rocks of dioritic composition, which technically fall in the category of black granites.

20 A large rubble pile at the historically reported site of the Glenelg quarry [St. Andrews Beacon, 22 March 1906] is clearly visible on aerial photographs to the east of Stein Lake. This rubble pile is located along a steep ridge about 400 m east-southeast of the south end of Stein Lake (Quarry No. 3, Figs. 1a, b) and 150 m west-northwest of the suspected site of the Steen Lake quarry (Quarry No. 2, Figs. 1a, b). Examination of loose blocks along the lower part of the ridge revealed that they were composed predominantly of grey diorite comparable to the monuments taken from the Glenelg quarry. Red granite dykes about a metre wide were observed to transect some of the diorite blocks. No actual quarry workings were observed but may exist on the difficult-to-reach, higher parts of the ridge.

21 Diorite locally intruded by granite dykes is sporadically exposed in the roadbed of the South Glenelg Road for about a kilometre southward from Stein Lake to the powerline crossing. A relatively new quarry, located on the west side of the South Glenelg Road about 250 m north of the powerline (Quarry No. 4, Figs. 1a, b), was developed by Fundy Contractors to provide riprap for the construction of breakwaters along the coast of the Bay of Fundy (Martin 2013, p. 88; Clarke et al. 2017, p. 104). An example of such a seawall using material from the South Glenelg Road quarry can be seen at the St. Andrews Biological Station.

22 The textural features of the so-called Glenelg porphyry are well displayed in the working face of the South Glenelg Road riprap quarry (Figs. 12). The predominant rock-type in the quarry is a medium-grained, grey, equigranular diorite. The characteristics of the feldspar in the diorite varies gradationally within the quarry. Diorite with clear white plagioclase (Fig. 13a) closely resembles the texture seen in the monuments taken from the Glenelg quarry (Figs. 8b. 9b. 10b, 11b). Elsewhere in the quarry, plagioclase in the diorite displays a dull waxy luster (Fig. 13b) that may be related to more intense alteration of the rock. The main mafic mineral in the diorite is black hornblende; remnants of augite may also be present as identified in a sample taken from the ‘Glenley’ quarry (Quarry No. 3, Figs. 1a, b) in 1911 by Parks (1914, p. 146). The diorite in the South Glenelg Road quarry is transected by greyish pink granitic veins (Fig. 13c) and a metre-wide, red granite dyke (Fig. 13d).

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12

23 Stuart’s designation of the Glenelg stone as a ‘porphyry’ is somewhat misleading in that conspicuous larger-sized crystals are not present in the diorite. The term may have been used in reference to the dominance of slightly larger, subhedral, white feldspar crystals over black mafic minerals in the rock. It should also be noted that feldspar crystals in some of the finer grained varieties of diorite seen in outcrop do display a seriate, porphyritic texture. Stuart’s earlier mention of his discovery of a ‘green and yellow porphyry’ may have been in reference to the presence of altered mafic minerals and feldspars that would have given the diorite a mottled greenish and waxy appearance similar to that described above in the South Glenelg Road quarry.

24 Dioritic rocks like those underlying the area east of Stein Lake also occur to the south of Gibson, Stuart, & Hanson’s Bocabec black granite quarry on Chickahominy Mountain (Quarry No. 1, Figs. 1a, b). There, blocks of diorite used to build up the road base about 150 m southeast of the quarry pit were derived from a cliff face on the east side of the haulage road. A medium-grained, greyish pink, biotite - hornblende, quartz monzonite is exposed another 100 m farther down the haulage road just off its east side. Dioritic rocks were also recognized by Hay (1967) during his mapping along the margin of the Bocabec plutonic complex in the St. Andrews - St. George area. Fyffe (1971) suggested that rocks of intermediate composition in the plutonic complex were formed by mixing of mafic and felsic magmas along the contact between Bocabec gabbro and Bayside monzogranite (Fig. 1).

GLENELG BLACK GRANITE LTD.

25 Ever the promoter, Sheriff Stuart sent a letter on the 17th November, 1913, to the Mayor and council of St. Andrews, outlining a business opportunity that arose after tariffs were reduced on manufactured granite entering the United States. In his letter, Stuart proposed that American investors could be induced to locate a granite manufacturing plant in St. Andrews by offering them free land owned by the town, an exemption from taxes for a number of years, and a cash sum of one thousand dollars per year, for three consecutive years. Establishing such a plant, he suggested, would provide permanent employment for 40 or 50 skilled artisans. Furthermore, a tramway could be constructed at small expense from the Glenelg quarry to the present wharf at Birch Cove (Fig. 1a). The rough stock would then be transported from there to the plant at St. Andrews, at a fraction of the cost of taking it to St. George, where the stone was presently being manufactured [St. Andrews Beacon, 20 Nov. 1913]. Although the St. Andrews councillors reacted favourably to the proposal, nothing came of it, perhaps in part, because of the outbreak of the First World War.

26 On the 15th January, 1926, a company with the name ‘Glenelg Black Granite Ltd.’ was incorporated to quarry, cut, and manufacture stone from the Glenelg quarry (Table 1). Its capital stock totalled $20 000 and its head office was located in Chamcook, Charlotte County, New Brunswick (Fig. 1a). Heber Stuart of Baltimore, Maryland, and Amy Mowat of Portland, Oregon, the son and daughter of Sheriff Stuart, each contributed $5 000 to the venture. Directors of the company were Heber Stuart; Donald Murray, who contributed $3 000; and Woolford Griffith, who contributed $2 000 [St. Croix Courier, 26 Jan. 1926], (Glenelg Black Granite Ltd. 1926, New Brunswick Provincial Archives). The goals of the company – “ To carry on and promote a general stone business in all its branches, including quarrying, cutting, polishing, sawing, and manufacturing in every way shipping, buying and selling stone in all business both wholesale and retail, and to do all things as are incidental to such objects, with power, to build, erect, establish, maintain and operate mills, mill buildings and erections, necessary or convenient for the carrying out of the various purposes of the Company” – would appear to be overly ambitious given the market condition of the time.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

27 Although Wright (1934, p. 29) did not visit the Glenelg porphyry quarry during his trip to Charlotte County in 1932, he did examine two varieties of the stone at the company’s headquarters at Chamcook. He noted that one variety has a distinctly greenish tinge whereas the other variety is much darker in colour, suggesting that both Glenelg porphyry (diorite) and Steen Lake black granite (gabbro) were being quarried at this time. The monument in memory of Sheriff Stuart (1840–1935) placed in the St. George Rural Cemetery (Figs.14a, b) has a texture indistinguishable from Steen Lake black granite (compare with Figs. 6b, 7b).

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14

COMPARISON OF THE ROBERT STUART AND CHARLES HANSON QUARRIES

28 H. McGrattan & Sons of St. George opened a black granite quarry on Charles Hanson’s property, north of the community of Bocabec, on the hillside just west of the Bocabec River (Quarry No. 5, Fig. 1a) [St. Andrews Beacon, 8 March 1906]. The stone was marketed as Egyptian Black (Park 1914). The landowner, Charles Eliphalette Hanson, was a cousin of Jeremiah Munn Hanson, who was a partner in the firm of Gibson, Stuart & Hanson (Maltby 2003). Clarke et al. (2017) proposed that the Charles Hanson quarry provided the headstones placed in the Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to mark the graves of passengers lost when RMS Titanic sank in the Atlantic on the 15th April 1912. However, these authors could not rule out the possibility that Sheriff Stuart’s quarries may have been a source of the headstones (see their Table 7). Given the more detailed account of the development of the Stuart quarries documented in this paper, we conclude that his quarries were not the source of the Titanic headstones.

29 One of the most striking features of the Titanic headstones is the presence of the so-called ‘snowflake’ texture (Holt 1968; Clarke et al. 2017). The similar textures in several photographs of these headstones (two of which are shown in Figs. 15 and 16), illustrate the ubiquity of this feature, and suggests that all the Titanic headstones in the Fairview Lawn Cemetery came from the same source. Clarke et al. (2017) have made a strong case for the Charles Hanson quarry being that source and further evidence presented below lends support to their proposal.

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16

30 Although black granite monuments from the Gibson, Stuart, & Hanson Bocabec quarry at the top of Chickahominy Mountain, and from Stuart’s Steen Lake black quarry also display a well-developed ‘snowflake’ texture (Figs. 4b, 6b, 7b), they do not appear to have been in production around the time that the Titanic went down. The Bocabec quarry was up for sale in 1897 with apparently no buyers, and the last report of stone being taken from the Steen Lake quarry was in 1906. Stuart’s Glenelg porphyry quarry was active over the time period from 1906 to 1913, but mostly produced a grey stone (diorite) that lacked the distinctive ‘snowflake’ texture (Figs. 8b, 9b, 10b, 11b) of the black granite (gabbro) taken from the Steen Lake quarry.

31 It could be argued that around the time of the Titanic’s sinking, Epps, Dodds & Co. had a stockpile of suitable black granite, collected over previous years when it worked the Steen Lake quarry, or that the company had access to black granite blocks from the Steen Lake quarry when it was taking stone from the adjacent Glenelg porphyry quarry in 1912–13. However, another line of evidence indicates that there is a subtle difference in texture between the black granites taken from the Steen Lake and Charles Hanson quarries. In the spring of 1909, H. McGrattan & Sons, who owned the Charles Hanson quarry, placed a monument in the new Catholic cemetery in St. George in memory of Cornelius Sullivan and his spouse [Granite Town Greetings, 26 May 1909]. This monument was described as standing about five feet high with a base of hammered grey granite surmounted by a die of black granite on which a cross is engraved (Fig. 17a). The stone has the distinctive ‘snowflake’ texture but is also dotted with an abundance of reddish brown spots that were likely formed by alteration of olivine (Fig. 17b). These spots are absent in known monuments from the Steen Lake quarry (Figs. 6b, 7b), but are a common feature of the Titanic headstones (Figs. 15, 16).

Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17

DISCUSSION

32 Heavy American tariffs, cheaper overseas imports, and decline in the popularity of red granite as a monument and building stone, led to the merger and eventual closure of the once prosperous granite manufacturing works in St. George, New Brunswick (Martin 2013). Epps, Dodds & Co. and Tayte, Meating & Co. merged in 1916 to form the Meating, Epps Co. The Saint George Red Granite was sold to Meating, Epps Co. in 1933. Milne, Coutts & Co. bought the Meating, Epps Co. in 1945 and closed down in 1953. H. McGrattan & Sons, owners of both red and black granite quarries, ceased operation in 1953. Little is known of the success or failure of Stuart family’s latest business venture, Glenelg Black Granite Ltd., established in 1926.

33 The extent to which the granite industry had declined in Charlotte County, following the Second World War, is illustrated by the business dealings of Warren Cottrelle of Montreal, Quebec. Cottrelle had established an office in Saint John, New Brunswick, to promote the revival of granite manufacturing in the St. George and Bocabec districts [Telegraph Journal, Dec. 5, 1946], (Patterson 1948). Cottrelle’s stated plans in 1946 included the purchase of Milne, Coutts & Co.’s granite works in St. George and a red granite quarry near Lake Utopia, and to secure operating rights for some black granite quarries in the Bocabec area. However, the financial situation within the business was unclear and little in the way of development was accomplished over the next two years. In the meantime, Cottrelle’s promotional methods were being questioned by the Ontario Securities Commission and the Office of the Attorney General of New Brunswick, and soon thereafter, he left the province to take up residence in British Columbia (Cottrelle 1947– 48). The black granite industry in New Brunswick did undergo a successful resurgence in 1962, when Nelson’s Monuments Ltd. re-opened the Spinney black granite quarry on the west side of Digdeguash Lake in Charlotte County (Fig. 1a). The quarry operated for six years and produced a high-quality stone marketed as Atlantic Black Granite (Martin 2013). It is perhaps fitting that this company, based in Sussex, Kings County, New Brunswick, was the last to carry on the legacy of Sheriff Robert Stuart, who had grown up a hundred years ago only 30 km down the road on a farm near Hampton.

34 Textures of representative headstones taken from each of the black granite quarries examined in the Bocabec area of Charlotte County, New Brunswick, are compared to a representative Titanic headstone from Halifax, Nova Scotia, in Figure 18. Headstones from the Gibson, Stuart & Hanson’s Bocabec (Fig. 18a), R.A. Stuart’s Steen Lake (Fig. 18b), and H. McGrattan & Sons’ Charles Hanson (Fig. 18e) quarries all possess a ‘snowflake’ texture comparable to that of the Titanic headstone (Fig. 18c), whereas this texture is lacking in the headstone from the Glenelg quarry (Fig. 18d). The headstone from Charles Hanson quarry, located north of the community of Bocabec, has both texture and mineralogical composition closely resembling the Titanic headstone (Figs. 18e and 18c). Up to 1% olivine in wall-rock of the Charles Hanson quarry (No. 5, Fig. 1a) and in the Titanic headstones has been identified by Clarke et al. (2017), whereas no olivine was reported by Parks (1914) in his limited microscopic examination of samples from quarries in the vicinity of Chickahominy Mountain (No. 1 2, and 3, Fig. 1b). Our qualitative analysis of the textural and mineralogical variations in black granite monuments from cemeteries in the St. Andrews - St. George area thus provides strong supportive evidence that the Charles Hanson quarry is the only suitable source for the Titanic headstones.

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Barrie Clarke of Dalhousie University for discussions on the texture of the Titanic headstones in the Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, for providing photographs of some of these stones, and for reviewing an earlier draft of the manuscript.. Journal reviewer Andy Kerr provided comments that helped improve the presentation of the paper. Terry Leonard drafted the map of the Bocabec area. The assistance of staff from the Charlotte County Archives in St. Andrews and Province of New Brunswick Archives in Fredericton is greatly appreciated. Les Fyffe would like to acknowledge Dr. George E. Pajari (1936–2017), former professor of petrology at the University of New Brunswick, for his support of field mapping projects in the Bocabec area many years ago.

REFERENCES

Editorial responsibility: Sandra M. Barr