Article

Alethopteris and Neuralethopteris from the lower Westphalian (Middle Pennsylvanian) of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Maritime Provinces, Canada

doi:10.4138/atlgeol.2020.005

Abstract

A systematic revision of Alethopteris and Neuralethopteris from upper Namurian and lower Westphalian (Middle Pennsylvanian) strata of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, eastern Canada, has demonstrated the presence of eight species: Alethopteris bertrandii, Alethopteris decurrens, Alethopteris cf. havlenae, Alethopteris urophylla, Alethopteris cf. valida, Neuralethopteris pocahontas, Neuralethopteris schlehanii and Neuralethopteris smithsii. Restudy of the Canadian material has led to new illustrations, observations and refined descriptions of these species. Detailed synonymies focus on records from Canada and the United States. As with other groups reviewed in earlier articles in this series, it is clear that insufficient attention has been paid to material reposited in Canadian institutions in the European literature. The present study emphasizes the similarity of the North American flora with that of western Europe, especially through the synonymies.

Résumé

Une révision systématique des Alethopteris et Neuralethopteris des strates du Namurien supérieur et du Westphalien inférieur (Pennsylvanien moyen) de la Nouvelle-Écosse et du Nouveau-Brunswick, dans l’est du Canada, a démontré la présence de huit espèces : Alethopteris bertrandii, Alethopteris decurrens, Alethopteris cf. havlenae, Alethopteris urophylla, Alethopteris cf. valida, Neuralethopteris pocahontas, Neuralethopteris schlehanii et Neuralethopteris smithsii. L’étude du matériel canadien a mené à de nouvelles illustrations, observations et descriptions raffinées de ces espèces. Les listes détaillées de synonymes se concentrent sur les documents du Canada et des États-Unis. Comme pour les autres groupes examinés dans les articles précédents de cette série, il est clair qu’une attention insuffisante a été accordée aux documents déposés dans les institutions canadiennes dans la littérature européenne. La présente étude souligne la similitude de la flore nord-américaine avec celle de l’Europe occidentale, notamment à travers les synonymies.

[Traduit par la redaction]

INTRODUCTION

1 This study is the ninth part of a revision of upper Namurian and lower Westphalian flora of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Maritime Provinces, Canada, begun in 2000 by R.H. Wagner at the request of John Utting, then of the Geological Survey of Canada. The reports began with a series of short papers (Wagner 2001, 2005a, b, 2008; Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008), and continued with more extensive contributions on lycopsids (Álvarez-Vázquez and Wagner 2014), the sphenopsid genera Annularia and Asterophyllites (Álvarez-Vázquez and Wagner 2017), and ferns (Álvarez- Vázquez 2019). The revision is based on examination of specimens and a critical re-evaluation of illustrations and descriptions in publications by Dawson (1862, 1863, 1868, 1871), Matthew (1910), Stopes (1914) and Bell (1938, 1944, 1962, 1966).

2 The specimens involved are mainly preserved as impressions. Most are reposited in the collections of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) in Ottawa (catalogue numbers preceded by GSC). They are mostly fragmentary specimens collected in the course of field mapping by Geological Survey of Canada personnel at the end of the Nineteenth Century and the beginning of the Twentieth Century; the collection was initially studied by Walter A. Bell in the mid-Twentieth Century. Bell’s (1944) memoir is very comprehensive, but his use of photographs commonly at natural size makes it often difficult to see the details necessary for an accurate identification — perhaps one of the reasons why Bell’s work has not been used extensively. In addition to the collections already mentioned, several specimens from the New Brunswick Museum at Saint John, New Brunswick (14 specimens designated with catalogue numbers with the prefix NBMG), and the Donald Reid Collection, Joggins Fossil Institute, Joggins, Nova Scotia (four specimens designated with catalogue numbers with the prefix DRC), have also been reviewed for the present study.

3 For more complete information about the localities associated with the GSC material, the reader is referred to the memoirs published by Bell (1938, pp. 108–115; 1944, pp. 111–118).

SYSTEMATIC PALEOBOTANY

4 As in previous papers in this series (Álvarez-Vázquez and Wagner 2014; Álvarez-Vázquez and Wagner 2017; Álvarez-Vázquez 2019), selective synonymy lists refer mainly to the published records from North America. Only the most significant records from elsewhere and specimens in the collections of the Paleobotanical Centre, Botanical Garden of Córdoba, Spain, are cited where required for a better understanding of the revised taxa. The synonymy lists are thus incomplete, but all old and new synonyms accepted in this study are included. The reader is referred to the Fossilium Catalogus Plantae (Jongmans 1957; Jongmans and Dijkstra 1961; Dijkstra and Amerom 1981, 1983) for additional, but uncritical, records.

5 Annotations in the synonymy lists are as follows: * = protologue; § = first publication of currently accepted combination; T = other illustrations of the holotype; ? = affinity questionable due to poor illustration or preservation; cf. (confer) = compare; p (pars) = only part of the specimens published belong to the species; v (vide) = the author has seen the specimen(s); k = reference includes cuticular evidence; acc. to = according to.

6 Also provided are: descriptions and/or comparisons and remarks on published specimens; stratigraphic occurrences in accordance with the western European regional chronostratigraphic subdivisions of the Pennsylvanian Subsystem; and geographic distribution of taxa in Canada and the USA.

7 Names of taxa at generic and lower rank cited herein are listed with full authorship in the Appendix.

Order Medullosales Corsin 1960

Family Alethopteridaceae Corsin 1960 emend. Cleal and Shute 2003

Genus Alethopteris Sternberg 1825 emend. Zodrow and Cleal 1998

- 1825 Alethopteris Sternberg, p. 21.

- 1910 Johannophyton Matthew, p. 83–84 (acc. to Stopes 1914).

- 1912 Alethopteris Sternberg; Franke, p. 1–13.

- 1955 Alethopteris Sternberg; Crookall, p. 6–8.

- 1957 Alethopteris Sternberg; Jongmans, p. 89–90 (including synonymy).

- 1961 Alethopteris Sternberg; Buisine, p. 65–74 (including synonymy).

- 1968 Alethopteris Sternberg; Wagner, p. 22–30 (including synonymy).

- 1996 Alethopteris Sternberg; Šimůnek, p. 6–7.

- 1998 Alethopteris Sternberg; Zodrow and Cleal, p. 70–71 (emended diagnosis).

8 Type. Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim 1820 ex Sternberg 1825.

9 Diagnosis. Bipartite fronds. Primary pinna tripinnate, with no intercalated pinnules or pinnae on the primary or secondary rachises, which are usually striate. Pinnules asymmetric, fused at the base, decurrent on the basiscopic side, straight or slightly constricted on the acroscopic side. Pinnule lamina thick, giving a vaulted aspect to the pinnules. Venation characterized by a well-marked and strongly decurrent midvein and numerous, non-anastomosed laterals that meet the pinnule margin at about right-angles or somewhat obliquely. Lateral veins fork at irregular intervals, mostly once, sometimes by a tripartite division, and occasionally each fork divides again. (Shortened from the emended diagnosis by Zodrow and Cleal 1998 — cuticular characteristics excluded.).

10 Remarks. Although also recorded in upper Mississippian strata and extending into the lowermost Permian, Alethopteris is essentially a Pennsylvanian genus. The selection of the type as Alethopteris lonchitica has given rise to taxonomic problems, as discussed by Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2008). Extensive synonymies can be found in Jongmans (1957), Buisine (1961) and Wagner (1968).

11 Alethopteris is widespread and fairly closely circumscribed morphologically, forming a natural grouping with Lonchopteris (Brongniart 1828) and Lonchopteridium (see Gothan 1909, who established Lonchopteridium as a “subgroup” of Lonchopteris; and Guthörl 1958 who raised Lonchopteridium to generic rank). The three genera have pinnules of similar shape and size, with confluent, decurrent bases and are separated by different types of venation: free lateral veins in Alethopteris, pseudoanastomosed lateral veins in Lonchopteridium, and fully anastomosed veins forming polygonal meshes in Lonchopteris. Available evidence on reproductive organs suggests that Neuralethopteris, which has pinnules that have stalked to slightly decurrent base and free veins, also belongs to the same natural grouping (Buisine 1961; Goubet et al. 2000).

12 The size of Alethopteris fronds seems to have been very substantial, based on the 1.2-m-long fragment recorded by Laveine (1986), who calculated a total frond length of more than 7 m. Laveine et al. (1992) figured and described a probably bipartite frond with quadripinnate primary pinnae and without intercalary pinna elements on the rachises. Ovules are of the Trigonocarpus type (when preserved as casts or adpressions) and the Pachytesta-type (when anatomically preserved); and pollen producing organs are of the Whittleseya type (when adpressions) and the Bernaultia-type (when anatomically preserved).

Alethopteris bertrandii Bouroz 1956

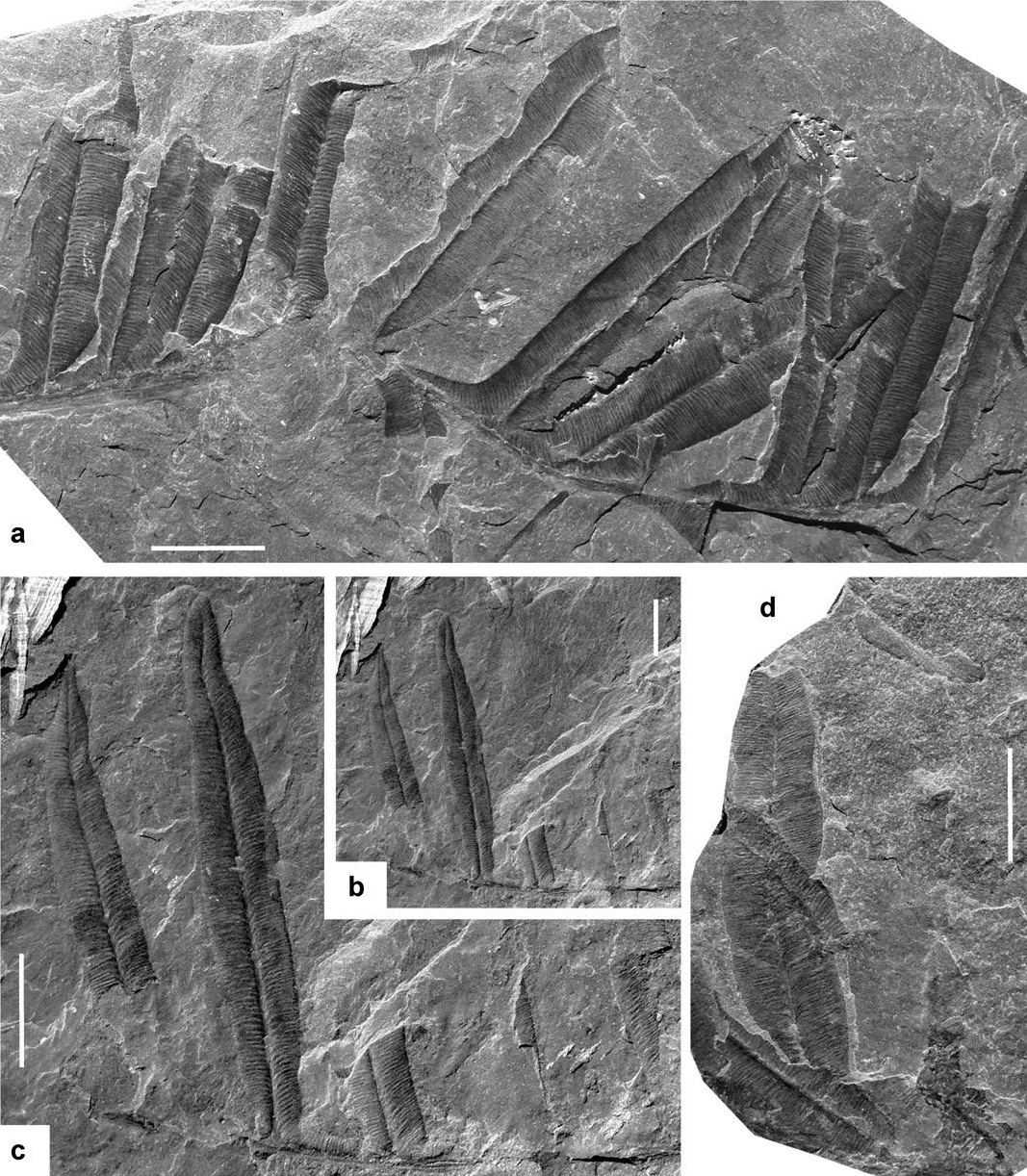

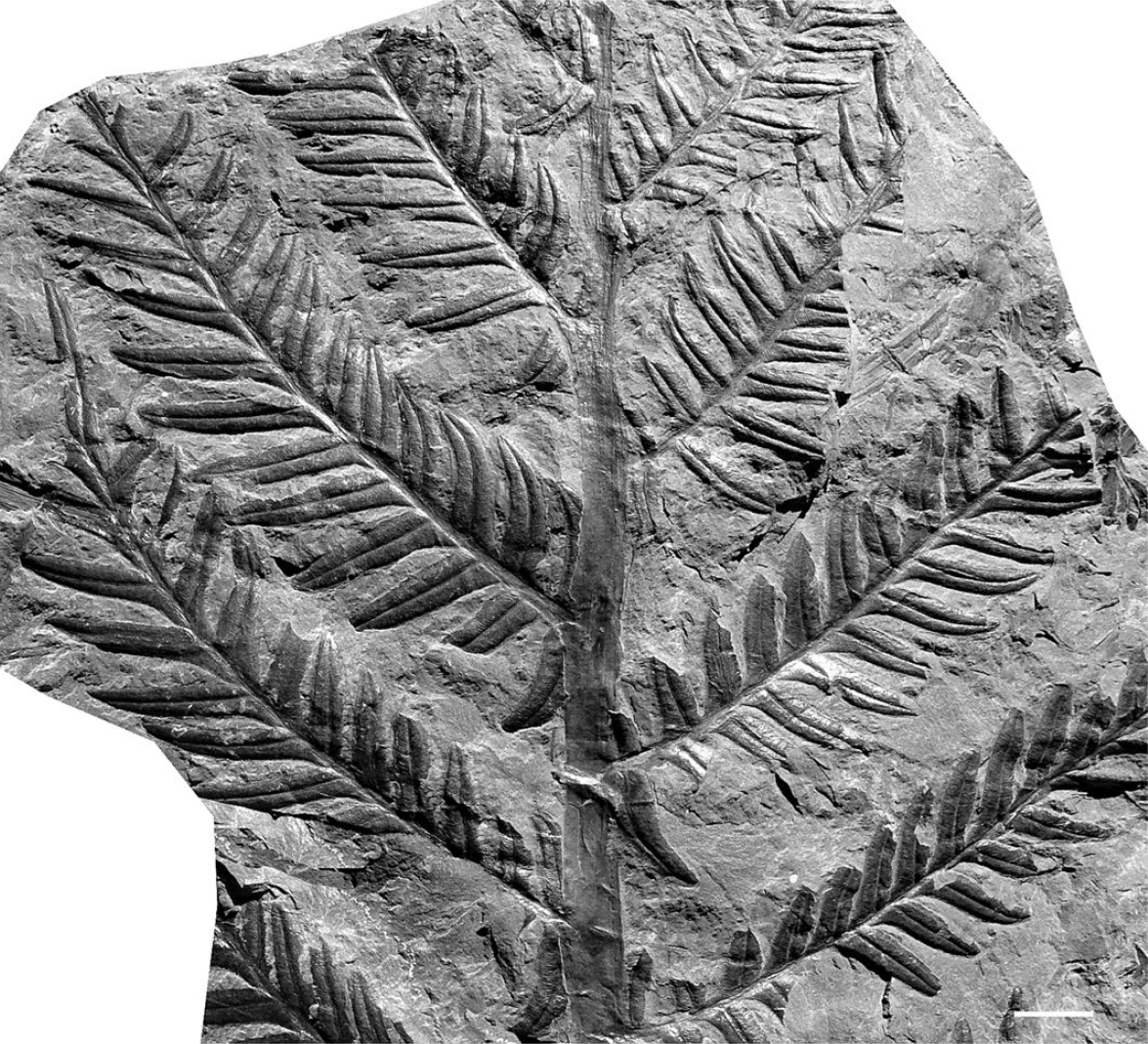

(Figs. 1a–b; 2a–d)

- p 1871 Alethopteris discrepans Dawson, p. 54, pl. XVIII, fig. 203; pl. XVIII, figs. 204–204c; non pl. XVIII, fig. 205 (this schematic figure cannot be properly judged, but it is comparable with both Alethopteris decurrens and Alethopteris urophylla).

- ? 1879–80 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Lesquereux, p. 177–179, pl. XXVIII, figs. 7–7a (included in Alethopteris lancifolia by Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- p 1910 Johannophyton discrepans Matthew, p. 83–85, pl. II, fig. 7 (included in Alethopteris lancifolia by Wagner 2005b); pl. III, fig. 1 (same as Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, fig. 203); pl. III, figs. 2, 4–6 (same as Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, figs. 204–204c — Alethopteris urophylla acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008); non pl. II, figs. 8–9 (sporangia); non pl. III, fig. 3 (resemble Alethopteris urophylla); non pl. III, figs. 7, 9 (= Alehtopteris urophylla); non pl. III, figs. 8, 10 (sporangia).

- v p 1914 Alethopteris lonchitica (= Alethopteris discrepans) Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Stopes, p. 47–53, pl. XIII, fig. 31 (photographic illustration of Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, fig. 204 — wrongly cited as fig. 240); pl. XIII, fig. 32 (poorly illustrated); non, pl. XII, fig. 30 (= Alethopteris urophylla); non pl. XIII, fig. 33 (fragmentary specimen, here included in Alethopteris decurrens); non pl. XVIII, fig. 46 (sporangia and pinnule fragments that may belong either to Alethopteris sp. or Neuralethopteris sp.); non pl. XXII, fig. 57A (= Alethopteris sp. indet. acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008); non text-figs. 8A–C (diagrammatic drawings — Alethopteris urophylla).

- p 1953 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Gothan, Taf. 4, fig. 1 (as Alethopteris lonchitica forma Serli in the plate); non p. 16–18, Taf. 4, figs. 2, 5 (= Alethopteris urophylla), fig. 3 (= Alethopteris urophylla?), fig. 4 (= Alethopteris westphalensis acc. to Wagner 1968); non Taf. 5, figs. 1, 4, 5 (= Alethopteris urophylla), figs. 2–2a (comparable with Alethopteris westphalensis acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008), fig. 3 (= Alethopteris pseudograndinioides acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008); non Taf. 6, fig. 1 (comparable with Alethopteris westphalensis acc. to Wagner 1968), figs. 2–4 (= Alethopteris urophylla).

- p 1955 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Crookall, pl. V, fig. 1; non p. 22–26, pl. V, fig. 2 (= Alethopteris urophylla); non pl. X, figs. 1, 3 (= Alethopteris urophylla); non text-fig. 7 (reproduction of Schlotheims’s original illustration); non text-fig. 14H (venation drawing).

- * 1956 Alethopteris Bertrandi Bouroz; p. 137–141, pl. VII, figs. A–C; pl VIII, figs. D–F; pl. IX, fig. G.

- T 1961 Alethopteris Bertrandi Bouroz; Buisine, p. 130–137, pl. XXVIII, fig. 1; pl. XXIX, fig. 1 (same as Bouroz 1956, pl. VII, fig. A), figs. 1a–1c (enlargements); pl. XXX, fig. 1 (same as Bouroz 1956, pl. VIII, fig. D), figs. 1a–1b; pl. XXXI, fig. 1 (same as Bouroz 1956, pl. IX, fig. G), figs. 2–2a; pl. XXXII, figs. 1–1a, figs. 2–2a (same as Bouroz 1956, pl. VII, fig. B); text-fig. 12 (drawing).

- * 1961 Alethopteris lancifolia Wagner, p. 6–8, pl. 1, figs. 1–4; pl. 2, figs. 5–8; pl. 3, figs. 9–11; pl. 4, figs. 12–13a.

- 1983 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Josten, p. 128–129, Taf. 47, figs. 1–1a; text-fig. 91 (venation drawing).

- 1987 Alethopteris discrepens latus Matthew; Miller, p. 20, fig. 19 (photographic illustration of Matthew 1910, pl. II, fig. 7).

- 1988 Alethopteris discrepens latus Matthew; Miller and Buhay, p. 223, fig. 5 (same as Miller 1987, fig. 19).

- v 2005b Alethopteris lancifolia Wagner; Wagner, p. 16–18, figs. 1a–b (partial counterpart of the specimen figured by Matthew 1910, pl. II, fig. 7).

- 2006 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Calder et al., p. 180, 183, fig. 11A (two specimens, part and partial counterpart; the one on the lower part refigured herein as Figs. 1a–b).

13 Description. Frond at least bipinnate. Penultimate order rachis straight, longitudinally striate, about 1 mm wide. Last order pinnae closely spaced or slightly overlapping laterally, apparently subrectangular, with subparallel margins tapering in the distal part. Dimensions: 80 mm long (incomplete) and 30–100 mm wide. Last order rachis straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.5–0.75 mm wide. Pinnules well spaced, inserted at 45–80º, united by a narrow band of lamina; they are large, sturdy, parallel-sided to slightly biconvex, with bluntly acuminate to obtuse apex, constricted acroscopic side and decurrent basiscopic. Dimensions: more than 55 mm length (longest, incomplete, pinnules) and 8–12 mm width; 12–18 mm length and 3–4 mm width the smaller. Lamina thick, vaulted. Venation clearly marked. Midrib straight, well marked and deeply imprinted in the lamina, extending to the apical part. Lateral veins relatively thin, close, sub-parallel and nearly perpendicular to both the midrib and pinnule margins, single or once forked near the midrib or at one third of the width. Subsidiary veins simple or, occasionally, once forked. Vein density = 36–40 per centimetre on the pinnule border.

14 Remarks. I include in Alethopteris bertrandii several specimens from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick previously figured as Alethopteris discrepans, Alethopteris lancifolia and Alethopteris decurrens.

15 Matthew (1910) referred Dawson’s (1871) illustration of Alethopteris discrepans to the new genus Johannophyton on the basis of associated seed capsules (Sporangites acuminatus) (note that Dawson’s “true” Pecopteris discrepans is synonymous with Alethopteris urophylla — see below). However, a direct connection between pinnae and seeds is nowhere visible, and Stopes (1914) and Bell (1944) rightly synonymized Johannophyton with Alethopteris. Together with new illustrations of the seeds, Matthew (1910) refigured Dawson’s (1871) original illustrations, adding drawings of additional specimens, including a pinna fragment with large pinnules showing a dense venation (Matthew 1910, pl. II, fig. 7). A photograph of this specimen was published by Miller (1987) and Miller and Buhay (1988) as Alethopteris discrepens (sic) latus Matthew, a manuscript name that appeared on the specimen label. The partial counterpart of this specimen was figured as Alethopteris lancifolia by Wagner (2005b).

16 Alethopteris lancifolia was described by Wagner (1961) from upper Langsettian strata from the Limburg coalfield, Netherlands. Although Wagner (2005b) noted that the Canadian specimens are more ribbon-shaped and the pinnules are somewhat larger, he assumed that this material was at one extreme of a range of variation of Alethopteris lancifolia. I herein regard Alethopteris lancifolia as a later taxonomic synonym of Alethopteris bertrandii, a species that Wagner apparently overlooked.

17 Comparisons. Alethopteris bertrandii is an easily recognizable species due to its large, sturdy, broadly lanceolate pinnules united by a narrow band of lamina. Only Alethopteris jankii shows pinnules with similar morphology, but they are even larger, up to 120 mm long, and have a more rounded apex. In addition, vein density is lower, ca. 25–30 veins per centimetre. Alethopteris jankii is, like Alethopteris bertrandii, a rarely cited species. However, I think that there are some other examples in the literature that should be included in it: e.g., two of the six specimens figured by Wittry (2006, figs 1, 5) as Alethopteris serlii from Mazon Creek. Lastly, Alethopteris urophylla, the most abundant and widespread species of Alethopteris in the Maritime Provinces (see below), possesses shorter pinnules with a considerable higher vein density, ca. 48–55 veins per centimetre, and it rarely shows unforked lateral veins.

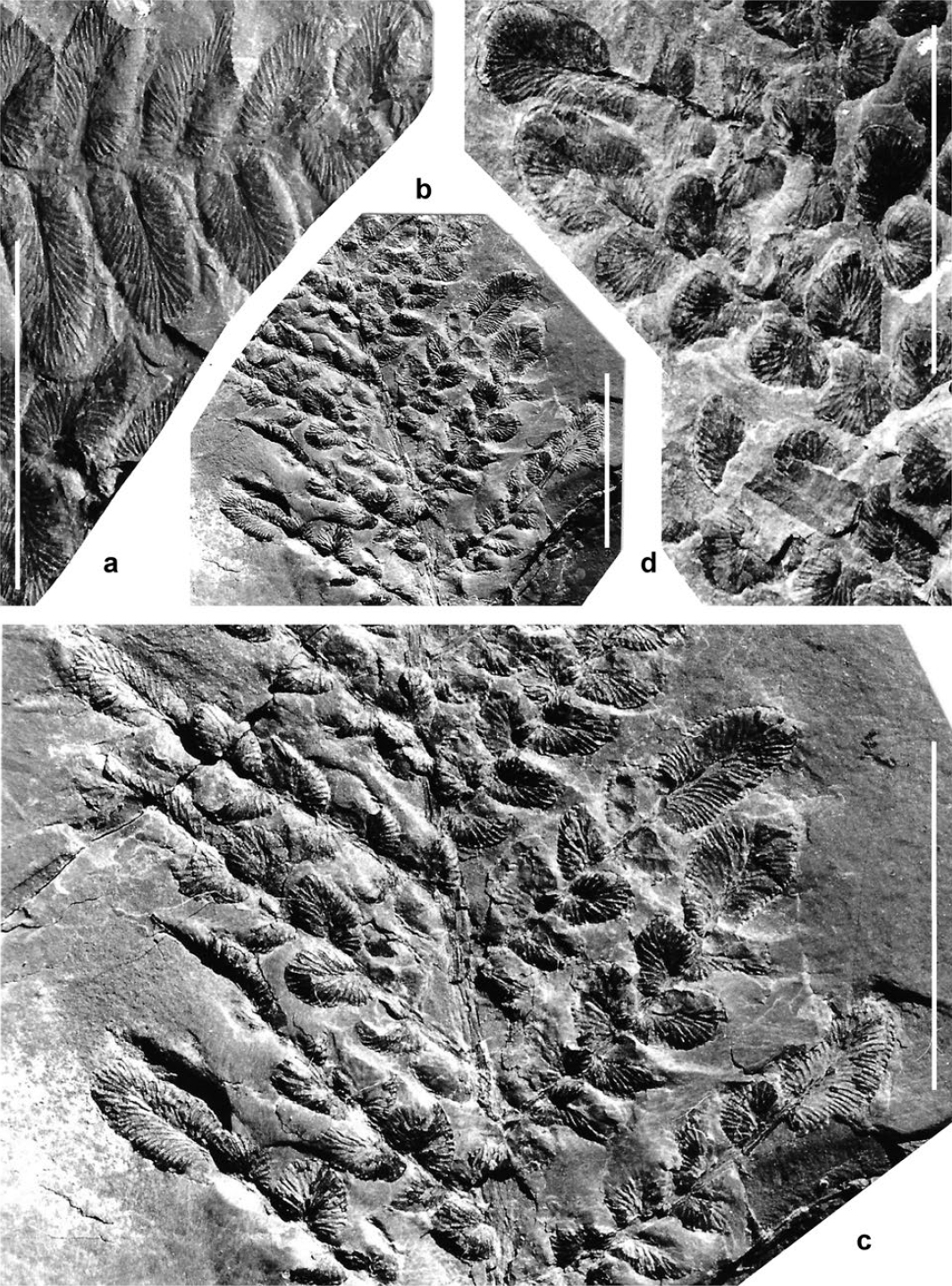

18 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Alethopteris bertrandii has not been cited as such outside its type area, the Nord/Pas-de-Calais basin, France. I have tried here to compose a complete synonymy list. The type material is from lower Westphalian C (Bolsovian) strata. The type material of the synonymous Alethopteris lancifolia is from upper Westphalian A (Langsettian) strata of the South Limburg Coalfield in the Netherlands. Crookall’s (1955) specimen, figured as Alethopteris lonchitica, originated from lower Duckmantian strata of the Yorkshire Coalfield, England; the specimen figured by Josten (1983) came from upper Namurian B strata of the Ruhr basin, Germany; and that published by Gothan (1953) came from an indeterminate locality in the Westphalian of the same basin.

19 Occurrence in the Maritime Provinces, Canada. Donald Reid collection, Joggins, Nova Scotia (1999): DRC– 997–72 (here Figs. 1a–b ― previously figured by Calder et al. 2006 as Alethopteris decurrens). Fern Ledges, New Brunswick: locality 135 (two pieces without catalogue number ― together with Psygmophyllum sp.); locality 351 (one piece without catalogue number). New Brunswick Museum collection: NBMG 3397 (specimen figured by Matthew 1910 as Johannophyton discrepans; as Alethopteris discrepens latus by Miller 1987 and Miller and Buhay 1988; and as Alethopteris lancifolia by Wagner 2005b). Fern Ledges, New Brunswick: Stopes (1914): McGill University collection 3314 (photographic illustration of Daw-son 1871, pl. XVIII, fig. 204).

20 Occurrence in the United States. Pennsylvania: Lesquereux (1879–1980).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Alethopteris decurrens (Artis 1825) Frech 1880

(Figs. 3a–f, 4d–e)

-

- * 1825 Filicites decurrens Artis, pl. xxi.

- * 1833 Pecopteris Mantelli Brongniart, p. 278–279, pl. 83, figs. 3–4 (acc. to Zeiller 1888).

- * 1876 Alethopteris gracillima Boulay, p. 33–34, pl. II, fig. 5 (acc. to Zeiller 1888).

- § 1880 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech, Taf. 1a, fig. 3.

- 1886-88 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Zeiller, p. 221–224, pl. XXXIV, figs. 2–3; pl. XXXV, fig. 1; pl. XXXVI, figs. 3–4.

- v p 1914 Alethopteris lonchitica (= Alethopteris discrepans) Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Stopes, pl. XIII, fig. 33 (fragmentary); non p. 47–53, pl. XII, fig. 30 (= Alethopteris urophylla); non pl. XIII, fig. 31 (= Alethopteris bertrandii — same as Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, fig. 204); non pl. XIII, fig. 32 (= Alethopteris bertrandii); non pl. XVIII, fig. 46 (sporangia and pinnule fragments that may belong to either Alethopteris sp. or Neuralethopteris sp.); non pl. XXII, fig. 57A (= Alethopteris sp. indet. acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008); non text-figs. 8A–C (diagrammatic drawings of Alethopteris urophylla).

- ? 1934 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Arnold, p. 195, pl. II, figs. 1, 3, 7.

- * 1938 Alethopteris scalariformis Bell, p. 69–70, pl. LXII, fig. 5; pl. LXV, figs. 4–7; pl. LXVI, fig. 3 (acc. to Crookall 1955).

- v 1944 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Bell, p. 87, pl. XL, fig. 1; pl. XLI, figs. 2–3; pl. XLII, fig. 5; pl. XLV, figs. 5–6.

- ? 1949 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Arnold, pl. XIX, fig. 4, fig. 7 (same as Arnold 1934, pl. II, fig. 7) (difficult to judge from the illustration — the fragmentary specimens also resemble Alethopteris urophylla).

- * 1952a–53 Alethopteris tectensis Stockmans and Willière, p. 241, pl. LVI, figs. 8–8a (the single fragment figured and described by Stock-mans and Willière shows the characteristic pinnules of Alethopteris decurrens: flexible, narrow, parallel-sided, decurrent and slightly contracted at the acroscopic side).

- * 1952a–53 Alethopteris Edwardsi Stockmans and Willière, p. 240, pl. LVI, figs. 9–9a (the only fragmentary figured specimen came from the same locality as that described as Alethopt eris tectensis).

- T 1955 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Crookall, p. 26–29 (including synonymy and a reproduction of Artis’s illustration), pl. II, figs. 1–3a; pl. VI, figs. 3–3a.

- 1955 Alethopteris decurrens var. gracillima Crookall, p. 29–30, pl. II, figs. 4–7; text-fig. 9 (reproduction of Boulay’s 1876 holotype of Alethopteris gracillima).

- 1957 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Janssen, p. 144, fig. 130.

- 1961 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Buisine, p. 155–167 (including synonymy), pl. XLI, figs. 1–1c; pl. XLII, figs. 1–3a; pl. XLIII, figs. 1–2a; pl. XLIV, figs. 1-5; text-figs. 14a–c.

- 1964 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Read and Mamay, p. 7, pl. 5, fig. 4.

- 1966 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Bell, p. 10, pl. IV, fig. 4.

- 1968 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Basson, p. 69–70, pl. 12, fig. 1 (figures poor).

- ? 1976 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Gillespie and Pfefferkorn, pl. I, fig. H (also resembles Alethopteris urophylla).

- ? 1977 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Pfefferkorn and Gillespie, pl. 2, fig. Q (same as Gillespie and Pfefferkorn 1976, pl. I, fig. H).

- ? 1978 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Gillespie et al., p. 98, pl. 36, fig. 1 (probably correctly identified, but lacking detail of venation).

- 1984 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Jennings, p. 307, pl. 4, fig. 2.

- 1985 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Gillespie and Rheams, pl. II, fig. 3 (figures poor).

- ? 1996 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Cross et al., p. 412, fig. 23–21.2 (difficult to judge — also resembles Alethopteris urophylla).

- k 1996 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Šimůnek, p. 7–8, pl. II, figs. 1–7; pl. III, figs. 1–2, figs. 3–9 (cuticles); pl. IV, figs. 1–3 (cuticles); text–figs. 4–7.

- 2014 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Bash-forth et al., p. 247, pl. III, fig. 10.

- Excludenda:

-

- 1963 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Wood, p. 48–49, pl. 5, fig. 9 (= Alethopteris urophylla).

- 1982 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Oleksyshyn, p. 94–95, figs. 19B, C (resembles Alethopteris missouriensis).

- 2002 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Blake et al., p. 264, 268, 291, pl. XVIII, fig. 2 (= Alethopteris urophylla acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- 2006 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Calder et al., p. 180, 183, fig. 11A (= Alethopteris bertrandii — see above).

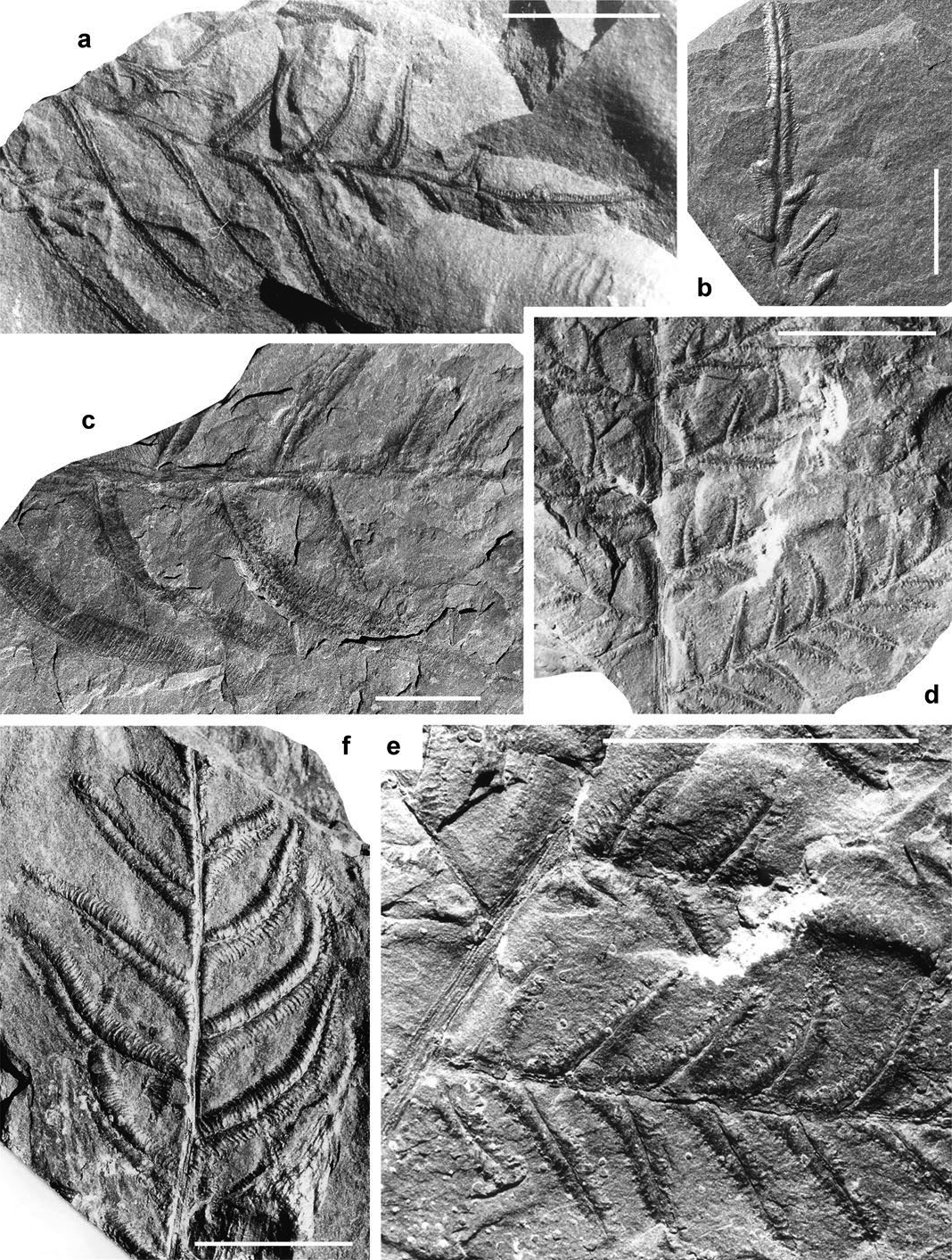

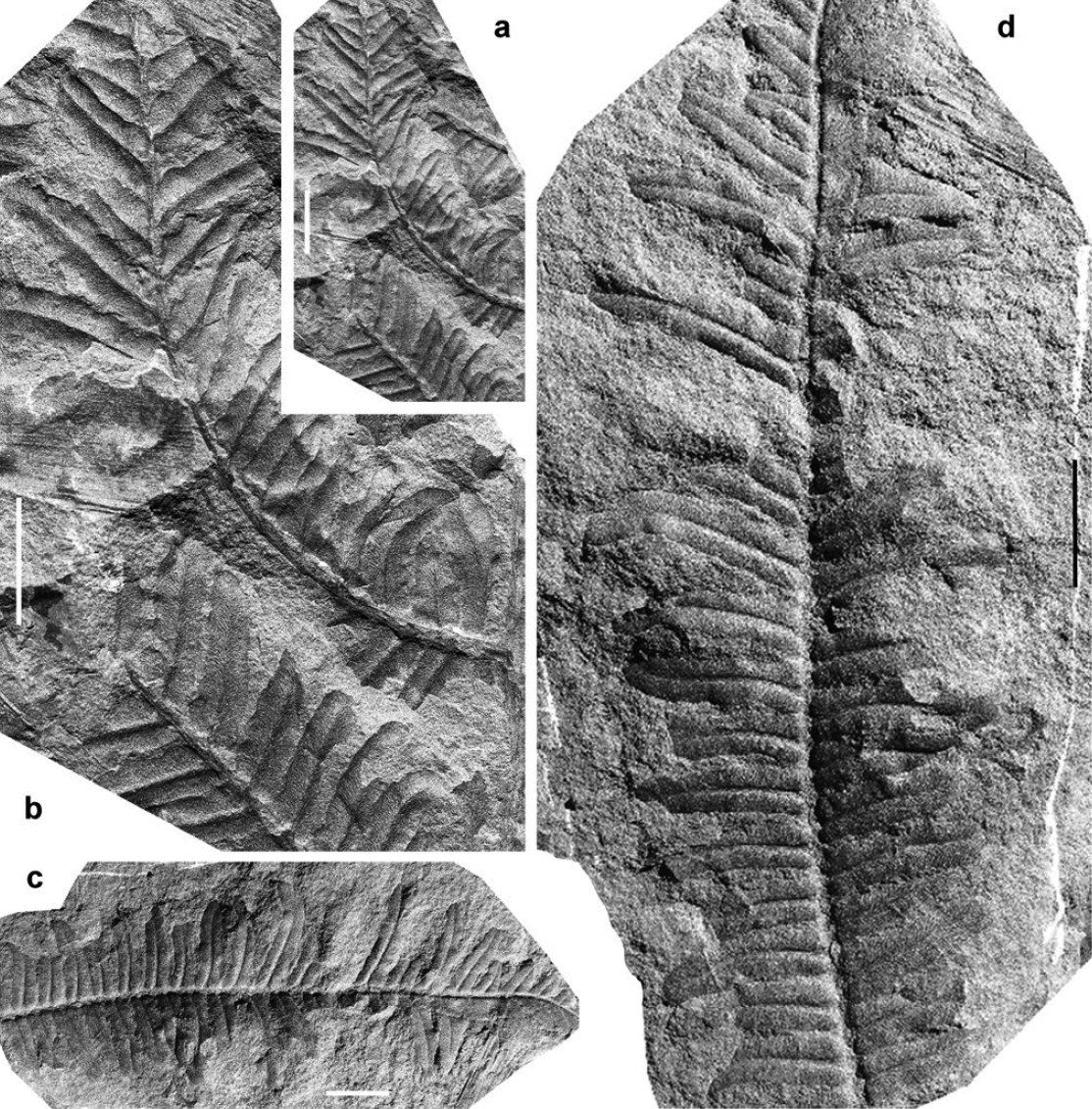

21 Description. Frond at least bipinnate. Penultimate order rachis straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.5–0.75 mm wide. Last order pinnae closely spaced or slightly touching laterally, elongate, with subparallel margins tapering in the distal part to form an acute angle; apical pinnule well-individualized, elongate, parallel-sided, with a sharply pointed apex, up to 19 mm in length. Dimensions: 60 mm long (incomplete) and 10–40 mm wide. Last order rachis straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.25–0.50 mm wide. Pinnules set well apart (3–5 mm), oblique to the rachis (30–60º), decurrent, confluent, slightly contracted at the acroscopic side. Variation in length is considerable, but the approximate width is consistent. Shorter pinnules straight, subtriangular, with bluntly pointed apex; longer pinnules narrow, parallel-sided and only tapering in the near-apical part, either arched or flexuous. Dimensions: 6–20 mm long and 2.5–3 mm wide; length/breadth ratio = 2.5–6.5. Lamina thick, convex, with a compression border not always visible. Venation characterized by a midrib straight, slightly decurrent, well marked in the vaulted lamina and visible up to the apex. Lateral veins closely spaced, relatively thick, almost perpendicular to both the midrib and pinnule margins, single or once forked at variable distances from the midrib; veins are, on the whole, fairly regularly disposed. Vein density = ca. 30–40 veins per centimetre.

22 Remarks. Crookall (1955, text-fig. 8) reproduced Artis’s original illustration of Alethopteris decurrens from Alverthorpe, Yorkshire, England (as reported by Cleal et al. 2009, most of Artis's specimens are lost). The holotype is a fragment of pinna of antepenultimate order with relatively strong rachises and widely spaced, confluent, oblique, narrow, almost parallel-sided (“linear”) pinnules that tend to become elongate in the terminal part of pinnae. The most extensive documentation of Alethopteris decurrens was published by Buisine (1961), who figured material from northern France. Previously, Boulay (1876) had introduced a new species, Alethopteris gracillima, also from northern France, which appears identical to Alethopteris decurrens. Although some authors consider Alethopteris gracillima to be a variety of Alethopteris decurrens (e.g., Crookall 1955), I follow Zeiller (1888) and Buisine (1961) in considering Alethopteris gracillima a junior synonym of Alethopteris decurrens.

23 Bell (1944, 1966) illustrated several, very characteristic, specimens of Alethopteris decurrens from Nova Scotia showing the widely spaced, elongate and narrow pinnules with strongly marked, fairly regularly disposed lateral veins, most of which are once forked. Previously, Bell (1938) described a new species, Alethopteris scalariformis, from the Sydney coalfield, as closely resembling Alethopteris decurrens. Bell noted closer and non-decurrent pinnules (except near the apical parts) in Alethopteris scalariformis, and more widely spaced veins that are dichotomized at wider angles. I agree with Crookall (1955) that these superficial differences do not appear to be of specific value and thus consider Alethopteris scalariformis to be a taxonomic junior synonynm of Alethopteris decurrens.

24 Comparisons. Alethopteris decurrens is a distinctive species, identified without much difficulty. Only Alethopteris davreuxii could pose problems, but it possesses more rigid pinnules that are subtriangular and tend to become slightly more tapering. Most characteristic of Alethopteris davreuxii is its wide venation characterized by once to twice forked veins of flexuous, almost anastomosing aspect. Vein density in Alethopteris decurrens is also distinctive, with some 30–45 veins per centimetre according to Buisine (1961). Although Alethopteris urophylla shows generally larger and broader pinnules with a tendency to have a biconvex shape and, particularly, a well-marked constriction at the base on the acroscopic side, occasional specimens occur with narrower pinnules that resemble those of Alethopteris decurrens. But Alethopteris urophylla possesses higher vein density (48–55 veins per centimetre), and it rarely shows unforked lateral veins.

25 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Alethopteris decurrens is relatively widespread. The holotype is from lower Westphalian strata of the Yorkshire Coalfield, England. According to Crookall (1955), the species ranges in Great Britain from Westphalian A to C (Langsettian to Bolsovian), being most common in Westphalian B (Duckmantian) and sporadic in Westphalian C (Bolsovian). Šimůnek (1996) recorded it from Namurian C and Westphalian A (Langsettian) strata of the Upper Silesian Basin, and from the Namurian C to the Westphalian B (Duckmantian) of the Intrasudetic Basin. Both Alethopteris tectensis and Alethopteris edwardsii originated from the same (undetermined) locality in the Assisse d’Andenne, upper Namurian (Yeadonian) of Belgium ― although Stockmans and Willière (1953) did not rule out the possibility that the specimens came from the Assise de Chokier. In Donbass, Alethopteris decurrens ranges from middle Bashkirian (C21) to lower Moscovian (C26) (Namurian C to Bolsovian) (see Fissunenko in Solovieva et al. 1996).

26 Occurrence in the Maritime Provinces, Canada. Cumber-land Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 1070 (one piece without catalogue number ― together with Cordaites sp.); locality 1338 (GSC 11000); locality 1420 (GSC 9313 ― here Figs. 3d–3e); locality 1435 (GSC 9315 + GSC 9320 + GSC 9323 + six pieces without catalogue number ― together with Renaultia sp., Bergeria dilatata and Annularia ramosa); locality 1450 (three pieces without catalogue number); locality 1982 (fragmentary ― one piece without catalogue number); locality 2982 (one piece without catalogue number). Bell (1966): locality 1450 (GSC 14995). Donald Reid collection, Joggins, Nova Scotia (1999): DRC–997–55. Saint John (New Brunswick): Bell (1944): locality 2573 (one piece without catalogue number). New Brunswick Museum: NBMG 3403 (labelled as the type of Alethopteris discrepans var. arctus, an unpublished name). Sydney Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1938): locality 752 (GSC 2640 + GSC 2642 + GSC 2647 ― holotype of Alethopteris scalariformis + GSC 2668).

27 Occurrence in the United States. Alabama: Gillespie and Rheams (1985). Illinois: Janssen (1957), Read and Mamay (1964), Jennings (1984). Michigan: Arnold (1934), Arnold (1949). Missouri: Basson (1968). Ohio: Cross et al. (1996). West Virginia: Gillespie and Pfefferkorn (1976), Pfefferkorn and Gillespie (1977), Gillespie et al. (1978).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Alethopteris cf. havlenae Šimůnek 1996

(Figs. 5a–e)

- 1970 Alethopteris lonchitica f. serlii Brongniart; Havlena, p. 97, pl. II, fig. 5.

- cf. 1977 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Leary and Pfefferkorn, p. 25–27, pl. 9, figs. 1–6 (specimens previously mentioned in Leary 1976, p. 4); text-figs. 9A–D (acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- * 1984 Alethopteris densinervosa Wagner; Havlena, p. 370–371, pl. I, figs. 2, 3 (designated by Šimůnek 1996 as the holotype of Alethopteris havlenae); pl. II, figs. 2, 3 (same as Alethopteris lonchitica f. serlii, Havlena 1970, pl. II, fig. 5).

- T k 1996 Alethopteris havlenae Šimůnek, p. 10–11, pl. V, figs. 5, 7–8, fig. 6 (cuticle); pl. VI, fig. 1, figs. 2–3 (holotype), figs. 4–5, 7, figs. 6, 8 (cuticles); text-figs. 11–13.

- ? 2014 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert; Bashforth et al., p. 247, pl. III, figs. 3, 4, 6–7, 9 (fragmentary).

28 Description. Frond at least bipinnate. Last order pinna apparently subrectangular (always incomplete), with parallel margins. Last order rachis straight, ca. 0.5–1 mm wide. Pinnules inserted obliquely (50–60º), closely placed; asymmetrical, tongue-shaped, with convex margins, rounded apex, narrowly confluent on the basiscopic side and with a marked constriction on the acroscopic. Apical pinnule not preserved. Dimensions: 4–12 mm long and 2–5 mm broad; length/breadth ratio = 2–2.5. Lamina relatively thick, vaulted. Venation composed by a midrib straight, relatively wide, extending to near the pinnule apex. Lateral veins thin, leaving the midrib almost at right angle and reaching the pinnule margin at 80–85º on the basiscopic side and at 55–85º on the acroscopic one; generally once forked near the midrib, rarely twice. Subsidiary veins once forked. Vein density = 55–60 veins per centimetre.

29 Remarks. Alethopteris havlenae is characterized by closely spaced, tongue-shaped, asymmetrical pinnules with rounded apex and the narrowly confluent base on the basiscopic side. The species was introduced by Šimůnek (1996) to accommodate specimens from the Upper Silesian Basin previously determined as Alethopteris serlii by Šusta (1928) and Alethopteris densinervosa by Havlena (1984).

30 I include in Alethopteris havlenae two previously unfigured specimens stored in the New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, and another two from the collections of the Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa; these specimens came from Fern Ledges. Also included as Alethopteris havlenae are five specimens figured as Alethopteris urophylla by Bashforth et al. (2014) from the Tynemouth Creek Formation, New Brunswick. All these specimens are fragmentary, which is why I include them questionably in Alethopteris havlenae.

31 Comparisons. Alethopteris serlii has pinnules of similar shape, but with more convex margins and a bluntly acuminated apex; vein density is also different, 30–35 veins per centimetre in Alethopteris serlii compared with 55–60 in Alethopteris havlenae. Alethopteris densinervosa shows clearly biconvex and more closely spaced pinnules that have a slightly higher ratio (2.5–3 times longer than broad); in addition, the midrib is not as thick as in Alethopteris havlenae, and lateral veins are fine and less numerous, about 40–45 veins per centimetre according to Wagner (1968). Alethopteris valida is characterized by its thick lamina and large, subtriangular pinnules connected by a broadly confluent lamina, about 2–3 mm wide; moreover, vein density is lower, about 25–30 veins per centimetre in the pinnule margin.

32 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Alethopteris havlenae is rarely reported. The holotype is from Namurian C strata of the Karviná Formation in the Upper Silesian Basin. Šimůnek (1996) reported the species in the Namurian C and the Westphalian A (Langsettian) of this basin.

33 Occurrence in the Maritime Provinces, Canada. Saint John (New Brunswick): Bell (1944): locality 2214 (one piece without catalogue number ― together with Rhacopteris sp.); locality 2254 (one piece without catalogue number ― together with Neuropteris obliqua). New Brunswick Museum: NBMG 1740 + NBMG 7559. Bashforth et al. (2014): NBMG 15440 + NBMG 15441 + NBMG 16210 + NBMG 16729 + NBMG 16730.

34 Occurrence in the United States. Illinois: Leary (1976); Leary and Pfefferkorn (1977).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart 1834) Göppert 1836

(Figs. 1c, 4a–c, 6)

-

- * v 1834 Pecopteris urophylla Brongniart, p. 290–291, pl. 86.

- § 1836 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert, p. 300.

- * 1848 Pecopteris multiformis Sauveur, pl. XXXVI, fig. 1 (acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- * 1862 Pecopteris (Alethopteris) decurrens sp. nov. Dawson (non Artis), p. 322, pl. XV, figs. 40a–c (diagrammatic drawings of fragmentary specimens).

- * 1862 Pecopteris (Alethopteris) ingens sp. nov. Dawson, p. 322, pl. XV, figs. 41a–b (see comments in Stopes 1914, p. 95–96).

- * 1863 Pecopteris discrepans Dawson, p. 468 (name change on the basis of the homonymy of Dawson’s 1862 Pecopteris (Alethopteris) decurrens with Lesquereux’s 1858 Pecopteris decurrens. However, the real homonym is Artis’s Filicites decurrens = Alethopteris decurrens).

- 1865 Alethopteris discrepans Dawson, p. 136–137.

- 1868 Alethopteris discrepans Dawson, p. 552–553, fig. 192I (same of Dawson 1862, pl. XV, fig. 40a).

- p ? 1871 Alethopteris discrepans Dawson, pl. XVIII, fig. 205 (this schematic figure cannot be properly judged; it can be also compared with Alethopteris decurrens); non p. 54, pl. XVIII, fig. 203 (= Alethopteris bertrandii); non pl. XVIII, figs. 204–204c (= Alethopteris bertrandii).

- p 1910 Johannophyton discrepans (Dawson) Mat-thew, pl. III, fig. 3; pl. III, figs. 7, 9; non pl. II, fig. 7 (= Alethopteris bertrandii); non pl. III, fig. 1 (= Alethopteris bertrandii — same as Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, fig. 203); non pl. II, figs. 8–9 (sporangia); non pl. III, figs. 2, 4–6 (same as Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, figs. 204–204c); non pl. III, figs. 8, 10 (sporangia).

- v p 1914 Alethopteris lonchitica (= Alethopteris discrepans) Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Stopes, pl. XII, fig. 30; text-figs. 8A–C (diagrammatic drawings); non p. 47–53, pl. XIII, fig. 31 (photographic illustration of Dawson 1871, pl. XVIII, fig. 204 — here Alethopteris bertrandii); non pl. XIII, fig. 32 (fragmentary and poorly illustrated — compared with Alethopteris corsinii by Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008 and here included in Alethopteris bertrandii); non pl. XIII, fig. 33 (comparable with Alethopteris decurrens); non pl. XVIII, fig. 46 (sporangia and pinnule fragments that, acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008, may belong either to Alethopteris sp. or Neuralethopteris sp.); non pl. XXII, fig. 57A (= Alethopteris sp. indet. acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- 1932 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Corsin, p. 18, pl. VIII, figs. 1–1a; text-fig. 7.

- 1935 Alethopteris grandifolia Newberry; Arnold, p. 280, fig. 1 (last order pinna with associated seed), fig. 3 (last order pinna with attached seed).

- 1937 Alethopteris grandifolia Newberry; Arnold, p. 46, fig. 1 (drawing of the fragment of last order pinna figured in Arnold 1935, fig. 3).

- 1944 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Bell, p. 86–87.

- 1949 Alethopteris Helenae Lesquereux; Arnold, p. 188–189, pl. XIX, figs. 5–6.

- p 1961 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Buisine, p. 99–115, pl. XIII, fig. 1; pl. XIII, figs. 2–2b; pls. XIV–XVI; pl. XVII, fig. 2, 4; pl. XVIII, figs. 1–1b; pls. XIX, XX; text-figs. 9a–c; non pl. XVII, figs. 1, 3 (= Alethopteris densinervosa acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008); non pl. XVIII, fig. 2 (= Alethopteris densinervosa acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- p 1961 Alethopteris serli (Brongniart) Göppert; Buisine, pl. VIII, figs. 2–2a (= Alethopteris urophylla acc. to Wagner 1968); non pls. I– VII, non pl. VIII, figs. 1–1a (= Alethopteris densinervosa acc. to Wagner 1968); non pl. IX, figs. 1–1a (= Alethopteris westphalensis acc. to Wagner, 1968); non pl. X, figs. 1–1a, 3-4 (= Alethopteris densinervosa acc. to Wagner 1968); non pl. IX, figs. 1–1a, pl. X, figs. 2–2a, pl. XI, figs. 1–2, pl. XII, figs. 1a–1c (= Alethopteris westphalensis acc. to Wagner 1968).

- 1963 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Wood, p. 48–49, pl. 5, fig. 9.

- v 1966 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Bell, p. 16, pl. VII, fig. 4.

- p 1985 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Gillespie and Rheams, p. 194, 199, pl. II, fig. 2; non pl. I, fig. 3 (Alethopteris valida acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- 1989 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Gillespie et al., p. 5, pl. 2, fig. 7.

- p 1996 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert; Šimůnek, p. 13–16, pl. X, figs. 1, 4 (after Šusta 1928, Taf. XXXIV, fig. 3), fig. 6 (trichome); pl. XI, fig. 1 (after Purkyňová 1990, Tab. II, fig. 4), figs. 2–7 (cuticles); pl. XII, fig. 1 (fragmentary; difficult to judge), figs. 2–4, fig. 5 (?), figs. 6–10 (cuticles); pl. XIII, figs. 1–8 (cuticles); pl. XIV, fig. 1; text-figs. 18–23; non pl. X, figs. 2–3 (resemble Alethopteris decurrens); non pl. X, fig. 5 (difficult to judge, but resembles Alethopteris havlenae); non text-fig. 17 (possibly Alethopteris havlenae).

- 1997 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Blake, p. 84, 85, pl. 2, figs. 1–3.

- 2002 Alethopteris decurrens (Artis) Frech; Blake et al., p. 264, 268, 291, pl. XVIII, fig. 2.

- ? 2002 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert; Blake et al., p. 264, 269, 291, 292, pl. XVIII, figs. 3, 5.

- ? 2006 Alethopteris discrepans (cf. A. lonchitica) Dawson; Calder et al., fig. 11B (difficult to judge from the illustration at less than natural size).

- 2006 Alethopteris Sternberg; Falcon-Lang, p. 44, fig. 10C (only an isolated pinnule but showing the slightly biconvex margins, bluntly acuminated apex and the constriction on the acroscopic side characteristic of the species).

- v T 2008 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert; Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez, p. 166–177 (including synonymy), fig. 1 (copy of Brongniart 1834, pl. 86), figs. 2–4 (photograph of the holotype), figs. 5–7d, figs. 8a–10 (same specimen as in Buisine 1961, pl. XIII, fig. 1), figs. 11a–12.

- v 2010 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert; Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez, p. 257, 258, 261 262, 266, 307, pl. IX, fig. 1 (together with Paripteris gigantea — same as Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008, fig. 11a).

- Excludenda (including Alethopteris lonchitica autorum):

-

- 1879-80 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Lesquereux, p. 177–179, pl. XXVIII, figs. 7–7a (= Alethopteris lancifolia acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- 1938 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Bell, p. 67, pl. LXI, fig. 5 (refigured by Zodrow and Cleal 1998, pl. 2, fig. 3 — acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008, it may be attributed to the Alethopteris lonchitifoliawestphalensis complex).

- 1939 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Janssen, p. 143, fig. 129 (mentioned in Leary 1976) (difficult to judge from the illustration; Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008 compared with Alethopteris lonchitifolia).

- 1958 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Langford, p. 241, figs. 438–439 (mentioned in Leary 1976) (Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008 compared with Alethopteris lesquereuxii).

- 1962 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Bell, pl. XLII, fig 4. (= Alethopteris cf. davreuxii? acc. to Wagner and Álvarez- Vázquez 2008).

- 1977 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Leary and Pfefferkorn, p. 25–27, pl. 9, figs. 1–6 (previously mentioned in Leary 1976, p. 4); text-fig. 9A–D (comparable with Alethopteris havlenae acc. Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- 1978 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Gillespie et al., p. 100, pl. 35, fig. 3 (venation diagram); pl. 36, fig. 7 (acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008, pointed pinnules tending to a lanceolate shape not suggestive of Alethopteris urophylla).

- 1982 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Olekyshyn, p. 98–99, figs. 19F–H (acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008 resembles Alethopteris missouriensis).

- 1985 Alethopteris cf. lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Lyons et al., pl. XI, fig. b (fragmentary and difficult to judge — either Neuralethopteris sp. indet. or Alethopteris sp. indet. acc. to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

- 2014 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Stern-berg; Moore et al., p. 38, 39, pl. VII, figs. 7–8 (fragmentary; comparable with Alethopteris lesquereuxii).

- 2014 Alethopteris urophylla (Brongniart) Göppert; Bashforth et al., p. 247, pl. III, figs. 3, 4, 6–7, 9 (although fragmentary, comparable with Alethopteris havlenae).

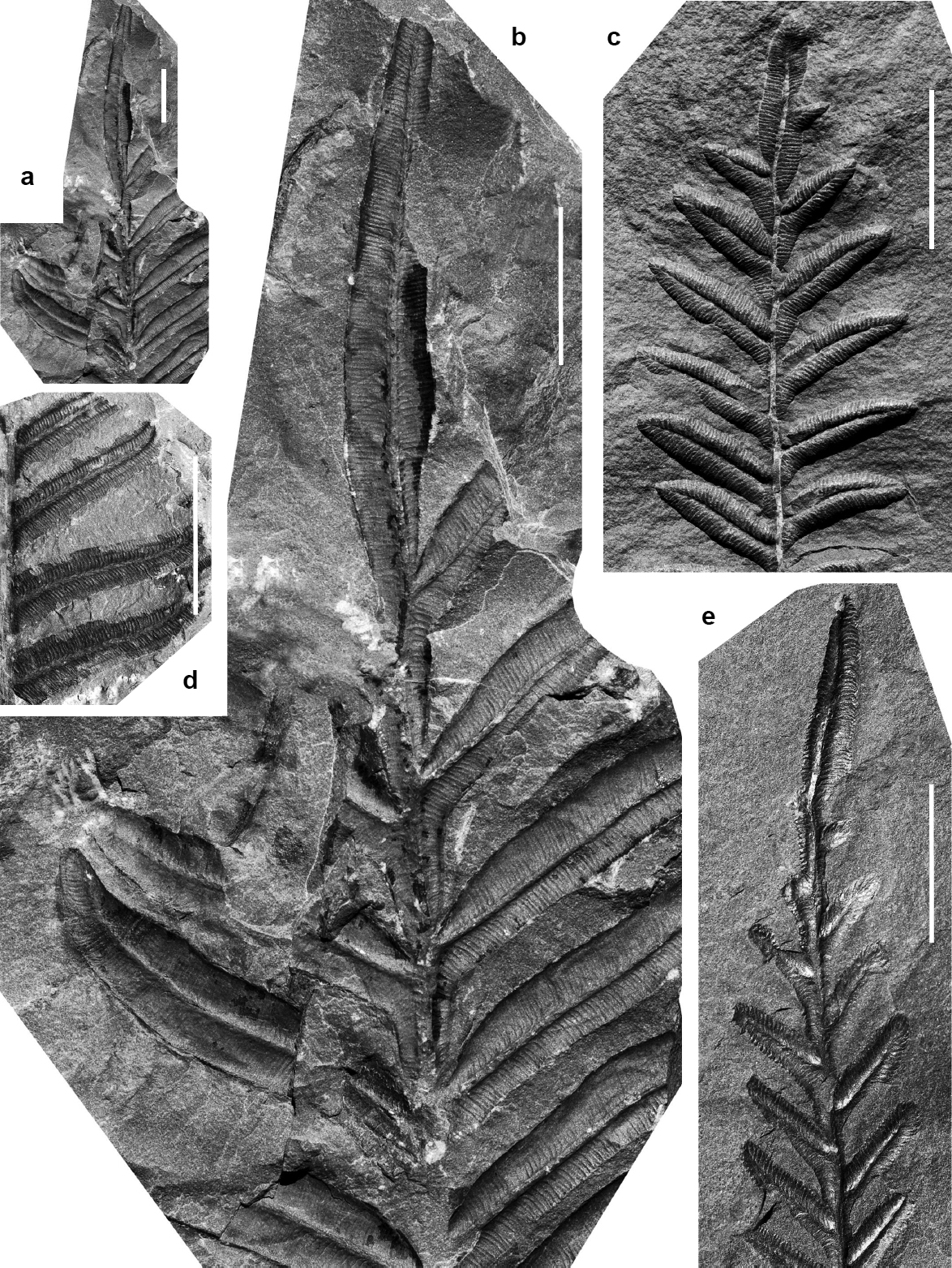

35 Description. Frond at least tripinnate. Penultimate order rachis strong, flat, straight, longitudinally striate, up to 10 mm wide. Last order pinnae alternate, close or slightly touching laterally; subrectangular, parallel-sided, tapering only in the distal part; lateral pinnules in the terminals only slightly shorter than the other laterals; apical pinnule well-individualized, elongate, parallel-sided, with a sharply pointed apex, up to 35 mm long. Dimensions: up to 130 mm long (incomplete) and 20–60 mm broad. Last order rachis inserted at 45–80º, straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.5–1.5 mm wide. Lateral pinnules spaced (3–5 mm), oblique to the rachis (at 45–80º), decurrent, with narrowly confluent bases and a constriction on the acroscopic side. Pinnule length variable depending on the position in the frond, whilst retaining the approximate width. Shorter pinnules straight, subtriangular, with bluntly pointed apex; longer pinnules parallel-sided to slightly biconvex, tapering in the near-apical part to a bluntly acuminate to rounded apex, either arched or flexuous. Dimensions: 9–27 mm long and 2.5–5 mm wide; length/ breadth ratio = 3.6–5.4. Lamina thick, convex, with a compression border not always clearly visible. Venation well marked, characterized by a midrib straight, very slightly decurrent, deeply imprinted in the lamina and extending up to near pinnule apex. Lateral veins thin, regularly disposed and closely spaced, slightly curved near the midrib and reaching the pinnule margin at right angles; generally once forked at variable distances from the midrib, rarely simple or with a second bifurcation. Subsidiary veins simple or once forked. Vein density = 48–55 veins per centimetre.

36 Remarks. Alethopteris urophylla was discussed by Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2008), who refigured and described the holotype (Brongniart 1834, pl. 86) and provided a full synonymy list. Comments on the synonymy are repeated herein if relevant to the Canadian and American material.

37 Originally described from Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales (Brongniart 1834), Alethopteris urophylla has been recorded widely from the Pennsylvanian paleoequatorial belt as represented in North America and Europe. Records have been mostly under the name of Alethopteris lonchitica, a Stephanian species that Zodrow and Cleal (1998) showed to be different from Alethopteris urophylla (see also Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008).

38 Buisine (1961) discussed Alethopteris discrepans, a substitute name provided by Dawson (1863) for Pecopteris (Alethopteris) decurrens, which was introduced by Dawson (1862) (see comment in the synonymy list); this species is based on diagrammatic drawings of very fragmentary specimens. In agreement with Stopes (1914), Buisine, included Alethopteris discrepans as a taxonomic junior synonym of Alethopteris lonchitica (meaning Alethopteris lonchitica auctorum = Alethopteris urophylla). This synonymy is supported by the illustration of material from Dawson’s original locality, the Fern Ledges at Saint John, New Brunswick, as well as other fragmentary remains from the Joggins section, Nova Scotia (see Stopes 1914).

39 Although Bell (1944, p. 87) mentioned Alethopteris lonchitica as the most abundant and widespread species in the Cumberland Group (he recorded it from 57 localities), he gave only a short description and no illustrations. Only at a later date did he figure a large and well-preserved specimen from Springhill (Bell 1966, pl. VII, fig. 4 — herein Fig. 6). The present restudy of the collections of the Geological Survey of Canada and the Joggins Fossil Institute confirms the abundance of Alethopteris urophylla in the Maritime Provinces.

40 Comparisons. Alethopteris lonchitica also shows parallel- sided pinnules of similar size, but they are slender and have a more broadly rounded apex. In addition, pinnules in Alethopteris lonchitica tend to be more pecopteroid and perpendicular to the rachis, and the midrib is wider and lateral veins more widely spaced. Alethopteris decurrens has narrower and more-parallel-sided pinnules that are much more spaced out; additionally, longer pinnules are arched or flexuous, vein density is lower, ca. 30–40 veins per centimetre, and lateral veins seem to be more irregular. Althopteris corsinii has pinnules of similar shape and size, but they are broader and more broadly confluent, with less marked constriction on the acroscopic side; venation is wider, only 30–35 veins per centimetre on the pinnule margin, and lateral veins are simple or fork once close to the midrib. Alethopteris bertrandii possesses larger, stiff, lanceolate pinnules. In addition, venation is wider, with about 40–45 veins per centimetre on the pinnule margin (Buisine 1961), and the elongate last order pinna terminals are very characteristic. Alethopteris solutifolia also possess decurrent, parallel-sided pinnules with rounded apex, narrowly confluent bases and a constriction on the acroscopic side; but the pinnules in that species are longer and narrower. Additionally, lateral veins are forked up to three times and are more widely spaced, with about 35 veins per centimetre in the pinnule margin.

41 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Alethopteris urophylla is widespread in the paleoequatorial belt, from Michigan in the west to the Donbass in the east. The holotype is from from lower Westphalian horizons at Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales. According to Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2008), the species ranges from middle Namurian (Kinderscoutian) to lower Bolsovian, with most records from Langsettian and Duckmantian strata. Pecopteris multiformis was described originally from an unknown horizon in the lower Westphalian of Belgium.

42 Occurrence in the Maritime Provinces, Canada. Cumberland Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 999 (GSC 7562 — together with Calamites carinatus + GSC 8586 — together with Diaphorodendron decurtatum + GSC 9556 + GSC 9575 + eight pieces without catalogue number — together with Zeilleria avoldensis); locality 1031 (GSC 10084 + five pieces without catalogue number — with Cordaites sp. and seeds); locality 1052 (GSC 9879 ― fragmentary but characteristic; together with Sphenophyllum cuneifolium, Cordaites sp. and Trigonocarpus sp.); locality 1070 (GSC 10192); locality 1081 (one piece without catalogue number); locality 1085 (two pieces without catalogue number— together with cf. Zeilleria hymenophylloides); locality 1089 (GSC 10164 + one piece without catalogue number— fragmentary); locality 1339 (one piece without cata-logue number); locality 1363 (one piece without catalogue number — fragmentary); locality 1491 (one piece without catalogue number — fragmentary and poorly preserved; with cf.); locality 1495 (one piece without catalogue number from a borehole — fragmentary and poorly preserved); locality 1498 (two pieces without catalogue number from a borehole — fragmentary); locality 2986 (three pieces without catalogue number); locality 2991 (one piece without catalogue number — poorly preserved). Bell (1966): locality 205 (GSC 14994 — Fig. 6 herein + six pieces without catalogue number, three of them figured in Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez 2008, figs. 7a–d ― together with Calamites cistii and Sphenophyllum cuneifolium). Donald Reid collection, Joggins, Nova Scotia (1999): DRC–149–99 + DRC–153– 99 ― together with Sigillaria scutellata and Lepidostrobophyllum lanceolatum. Fern Ledges, New Brunswick: Stopes (1914): McGill University collection 3312. New Brunswick Museum: NBMG 1805 (figured by Falcon-Lang 2006) + NBMG 12056. Prince Edward Island: locality 4454 (two pieces without catalogue number).

43 Occurrence in the United States. Alabama: Gillespie and Rheams (1985). Georgia: Gillespie et al. (1989). Indiana: Wood (1963). Michigan: Arnold (1949). Ohio: Arnold (1935, 1937). West Virginia: Blake et al. (2002).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Alethopteris cf. valida Boulay 1876

(Fig. 7)

-

- * 1876 Alethopteris valida Boulay, p. 35, pl. I, fig. 8.

- * 1884 Alethopteris Evansii Lesquereux, p. 834–835 (name and description only — acc. to Blake 1997, p. 82).

- 1886-88 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Zeiller, p. 231–233, pl. XXXIII, figs. 1–2A; pl. XXXIV, figs. 1–1A.

- 1900 Alethopteris Evansii Lesquereux; White, p. 887, pl. CXCII, figs. 7–8a.

- 1932 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Corsin, p. 19–20, pl. XI, figs. 1–1a; text-fig. 8 (same as Zeiller 1886, pl. XXXIII, figs. 1A–2A).

- 1951 Alethopteris nov. sp.?; Stockmans and Willière, pl. D, figs. 3–3a.

- T 1955 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Crookall, p. 13–17, pl. I, figs. 3–4, figs. 5–5a (same as Crookall 1932, pl. VI, fig. 3); text-figs. 5A–B (drawings); text-fig. 5C (reproduction of Boulay’s illustration).

- ? 1957 Alethopteris davreuxi (Brongniart) Göppert; Janssen, p. 145, fig. 132 (difficult to judge from the illustration).

- 1959 Alethopteris (Callipteridium) sullivanti (Lesquereux) Fontaine and White; Canright, pl. 4, fig. 11.

- T 1961 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Buisine, p. 168– 179 (including synonymy), pl. XLV, figs. 1–1b (reillustration of the holotype), figs. 2–2a; pl. XLVI, fig. 1; pl. XLVII, figs. 1a–2b; pl. XLVIII, figs. 1–1b (same as Corsin 1932, pl. XI, fig. 1), fig. 2; text-figs. 15a–c.

- 1963 Alethopteris grandini Brongniart; Wood, p. 49, pl. 6, fig. 3.

- 1963 Callipteridium sullivanti (Lesquereux) Weiss; Wood, p. 50, pl. 6, fig. 6.

- p 1978 Alethopteris evansi Lesquereux; Gillespie et al., pl. 36, fig. 5; non pl. 36, fig. 3 (= Alethopteris davreuxii).

- p 1985 Alethopteris lonchitica Schlotheim ex Sternberg; Gillespie and Rheams, p. 196, pl. I, fig. 3; non p. 194, 199, pl. II, fig. 2 (= Alethopteris urophylla).

- 1985 Alethopteris serli forma lonchitifolia Bertrand; Lyons et al., p. 228, 238, pl. XIII, figs. c–d.

- ? 1985 Alethopteris cf. integra (Gothan) Kidston; Gillespie and Crawford, p. 255, pl. III, fig. 4 (fragmentary).

- k 1996 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Šimůnek, p. 18–20, pl. XV, figs. 7–8; pl. XVI, figs. 1–6; pl. XVII, figs. 1–3, figs. 4–7 (cuticles); pl. XVIII, fig. 1, figs. 2–8 (cuticles); text-figs 27–31.

- 1997 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Blake, p. 82, pl. 2, figs. 4–5.

- 1997 Alethopteris davreuxii (Brongniart) Göppert; Blake, p. 82, pl. 7, fig. 4; pl. 11, fig. 5.

- 2002 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Blake et al., p. 268, 290, pl. XVI, fig. 3.

- 2005 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Dilcher et al., p. 161, fig. 4.3.

- 2005 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Dilcher and Lott, pl. 131, fig. 1 (same as Dilcher et al. 2005, fig. 4.3), figs. 2–3.

- Excludenda:

-

- 1938 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Bell, p. 68–69, pl. LXIV; pl. LXV, figs. 1–3; pl. LXVII, fig. 1 (Zodrow and Cleal 1998, p. 103 included all these specimens in Praecallipteridium cf. jongmansii).

- 1968 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Basson, pp. 72–73, pl. 11, fig. 2 (comparable with Alethopteris grandinii).

- 1982 Alethopteris valida Boulay; Oleksyshyn, pp. 104–105, figs 20G–H (the fragmentary specimens resemble Alethopteris lesquereuxii).

44 Description. Frond at least bipinnate. Last order rachis relatively straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.5 mm. Pinnules spaced, slightly obliquely inserted, decurrent, with a broadly confluent lamina (3 mm); these are subtriangular, with a bluntly pointed apex. Dimensions: 10–12 mm long and 5 mm broad; length/breadth ratio = 2–2.4. Lamina thick, vaulted. Midrib thin, clearly marked, visible in two third or more of the pinnule; lateral veins well spaced, one to twice forked, reaching the pinnule margin with a oblique angle. Vein density = ca. 30 veins per centimetre.

45 Remarks. Alethopteris valida is a very distinctive species that has been regularly recorded from upper Namurian to middle Westphalian strata, although generally as fragmentary specimens and single records. The species was originally described by Boulay (1876) from northern France, from where it was documented extensively by Buisine (1961). Although specimens of this species have been figured from several basins in the United States, Bell (1944, 1966) did not record Alethopteris valida from the Maritmes. Figured and described here is a fragment of last order pinna; although fragmentary and not well preserved, it is sufficiently characteristic to be assigned tentatively to the species as Alethopteris cf. valida.

46 Comparisons. Alethopteris valida is a distinctive species, easily separated from members of the genus by its thick lamina and large, subtriangular pinnules united by a broadly confluent lamina. It resembles Lonchopteridium eschweilerianum, but the subreticulate venation of the latter are distinctive.

47 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Alethopteris valida ranges from (Marsdenian?) Yeadonian to lower Bolsovian. In the Nord de la France, Buisine (1961) recorded it from upper Namurian (Yeadonian) to upper Westphalian B (Duckmantian), being most abundant in Westphalian A (Langsettian) strata. In Great Britain it is mostly confined to Westphalian A and B (Langsettian and Duckmantian; see Crookall 1955). In the Intrasudetic Basin, Šimůnek (1996) recorded this species from Namurian C to Westphalian B.

48 Occurrence in the Maritime Provinces, Canada. Cumber-land Basin (Nova Scotia): locality 1178 (GSC 10852).

49 Occurrence in the United States. Alabama: Gillespie and Rheams (1985), Lyons et al. (1985), Dilcher and Lott (2005), Dilcher et al. (2005). Georgia: Lesquereux (1884), Gillespie and Crawford (1985). Illinois: Janssen (1957). Indiana: Canright (1959); Wood (1963). Tennessee: Lesquereux (1884). West Virginia: Gillespie et al. (1978), Blake (1997), Blake et al. (2002).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

Genus Neuralethopteris Cremer 1893 emend. Laveine 1967

- 1893 Neuralethopteris Cremer, p. 32–33.

- 1965 Neuralethopteris Cremer; Wagner, p. 38, 39, 40.

- 1967 Neuralethopteris Cremer; Laveine, p. 97–102.

- 1995 Neuralethopteris Cremer; Cleal and Shute, p. 10, 12.

- 2000 Neuralethopteris Cremer; Goubet et al., p. 14–15.

- 2010 Neuralethopteris Cremer; Tenchov and Cleal, p. 300–301.

50 Type. Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur 1877) Cremer 1893.

51 Diagnosis. Pinnules tongue-shaped, with a cordate base, occasionally stalked in the proximal part, and more or less attached by the entire base in the distal part of the pin-nae; apex more or less rounded. Terminal pinnule strongly varying in shape and size depending on the species: ovate, lanceolate or linear. Venation of alethopteroid type with a midvein strong, reaching nearly to the apex of the pinnule. Lateral veins departing at an acute angle, reaching the margin perpendicularly, forking two or three times, with first bifurcation close to the midvein, and the second about half way between the midvein and the margin, often directly following the major curvature of the veins; the third, if present, near the margin. (Shortened from Goubet et al. 2000, p. 14.)

52 Remarks. Neuralethopteris is a widely distributed and biostratigraphically important genus that has been recorded from middle Namurian to lower Westphalian strata. The presence of pinnules with alethopterid venation in combination with basally constricted bases caused most species to be initially assigned to Neuropteris.

53 Laveine (1967) and Tenchov and Cleal (2010) summarized the historical development of the concept of Neuralethopteris; and Goubet et al. (2000) documented the genus for the first time in North America, including five species not found in Europe. Furthermore, Laveine et al. (1992) recorded the presence of a bipartite frond without intercalary pinna elements on the rachises, as in Alethopteris, and indicated that the frond would be about 5 m long. Associated ovules are of the Trigonocarpus-type and pollen organs are of the Aulacotheca/Boulayatheca/Whittleseya-types.

54 According to Wagner (1984), Neuralethopteris is common and characteristic in both the Neuralethopteris larischii–Pecopteris aspera (Chokierian to Yeadonian) and Lyginopteris hoeninghausii–Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Langsettian) macrofloral zones. Although some records occur in the basal Duckmantian (e.g., Tenchov and Cleal 2010), the extinction of Neuralethopteris is usually placed at the end of the Langsettian Substage.

Neuralethopteris pocahontas (White 1900) Goubet et al. 2000

(Figs. 8a–d)

- * 1900 Neuropteris Pocahontas White, p. 888–890, pl. CLXXXIX, figs. 4–4a; pl. CXCI, figs. 5–5a (holotype).

- 1900 Neuropteris Pocahontas var.inæqualis White, p. 890–892, pl. CLXXXVIII, figs. 5–5a; pl. CXC, fig. 7; pl. CXCI, figs. 1–4 (acc. to Goubet et al. 2000).

- 1937 Neuropteris Pocahontas White; Jongmans, p. 396, 397, 398, 400, 412; pl. 13, figs. 15–15a; pl. 14, figs. 16–20a; pl. 16, fig. 27; pl. 17, fig. 30.

- v 1944 Neuropteris smithsi Lesquereux; Bell, p. 79–80, pl. XXIX, fig. 2; pl. XXX, fig. 2 (reproduced partially herein as Fig. 8d); pl. XXXI, fig. 1 (Figs 8b–c herein), fig. 4; pl. XXXIII, fig. 3 (Fig. 8a herein), fig. 4; pl. LXVII, fig. 4.

- 1964 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Read and Mamay, p. 6, pl. 4, fig. 2.

- v 1966 Crossotheca pinnatifida (Gutbier) Potonié; Bell, p. 16, pl. IV, fig. 1.

- p 1966 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie et al., p. 90, 91, pl. 25, fig. 4; non pl. 25, figs. 2–3 (comparable with Neuralethopteris sergiorum).

- ? 1967 Neuropteris cf. pocahontas White; Tidwell, p. 43, pl. 5, figs. 4, 6.

- 1976 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie and Pfefferkorn, pl. I, figs. A, B.

- 1977 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Pfefferkorn and Gillespie, p. 23, pl. 2, fig. J (same as Gillespie and Pfefferkorn 1976, pl. I, fig. A), pl. 2, figs. K–L.

- 1978 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie et al., p. 6, 7, 102–103, 115, 128, pl. 2, fig. 1 (same as Pfefferkorn and Gillespie 1977, pl. 2, fig. L); pl. 47, fig. 1 (same as Gillespie et al. 1966, pl. 25, fig. 4), fig. 2 (same as Pfefferkorn and Gillespie 1977, pl. 2, fig. K), fig. 3 (same as Gillespie and Pfefferkorn 1976, pl. I, fig. A, and Pfefferkorn and Gillespie 1977, pl. 2, fig. J), fig. 5 (same as Pfefferkorn and Gillespie 1977, pl. 2, fig. L), figs. 7–8.

- 1979 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie and Pfefferkorn, pl. 1, fig. 1.

- 1981 “Neuropteris pocahontas” White; Pfefferkorn and Gillespie, p. 160, 162, pl. 2, figs. 1–4.

- ? 1985 Neuropteris (Neuralethopteris) pocahontas White; Gastaldo, p. 292, pl. 3, fig. C (poorly figured).

- 1986 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie and Pfefferkorn, p. 127, 128, pl. 3, fig. 1 (same as Pfefferkorn and Gillespie 1981, pl. 2, fig. 3), pl. 3, fig. 2 (same as Gillespie and Pfefferkorn 1979, pl. 1, fig. 1).

- 1989 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie et al., p. 5, 6, pl. 1, fig. 3 (same as Gillespie and Pfef ferkorn 1976, pl. I, fig. A, and Gillespie et al. 1978, pl. 47, fig. 3).

- 1997 Neuropteris (Neuralethopteris) pocahontas White; Blake, p. 81, 83, 84, pl. 4, figs. 1–2; pl. 6, fig. 5; pl. 7, fig. 1.

- § T 2000 Neuralethopteris pocahontas (White) Goubet et al., p. 18–19 (including synonymy), figs. 5.3–5.6; fig. 6 (drawing); fig. 7.3 (photograph of White’s holotype); figs. 7.4–7.5 (same as White 1900, pl. CLXXXVIII, figs. 5–5a); figs. 7.6–7.7; fig. 17.10 (associated with seeds).

- 2002 Neuralethoperis pocahontas (White) Goubet et al.; Blake et al., p. 268, pl. XIV, figs. 3–4; pl. XV, fig. 9 (same as Pfefferkorn and Gillespie 1977, pl. 2, fig. L, and Gillespie et al. 1978, pl. 47, fig. 5).

- 2005 Neuralethopteris pocahontas (White) Goubet et al.; Dilcher et al., p. 163, fig. 4.5.

- 2005 Neuralethopteris pocahontas (White) Goubet et al.; Dilcher and Lott, pl. 134, fig. 2 (same as Dilcher et al. 2005, fig. 4.5); pl. 135, fig. 3; pl. 136, fig. 3 (difficult to judge from the illustration).

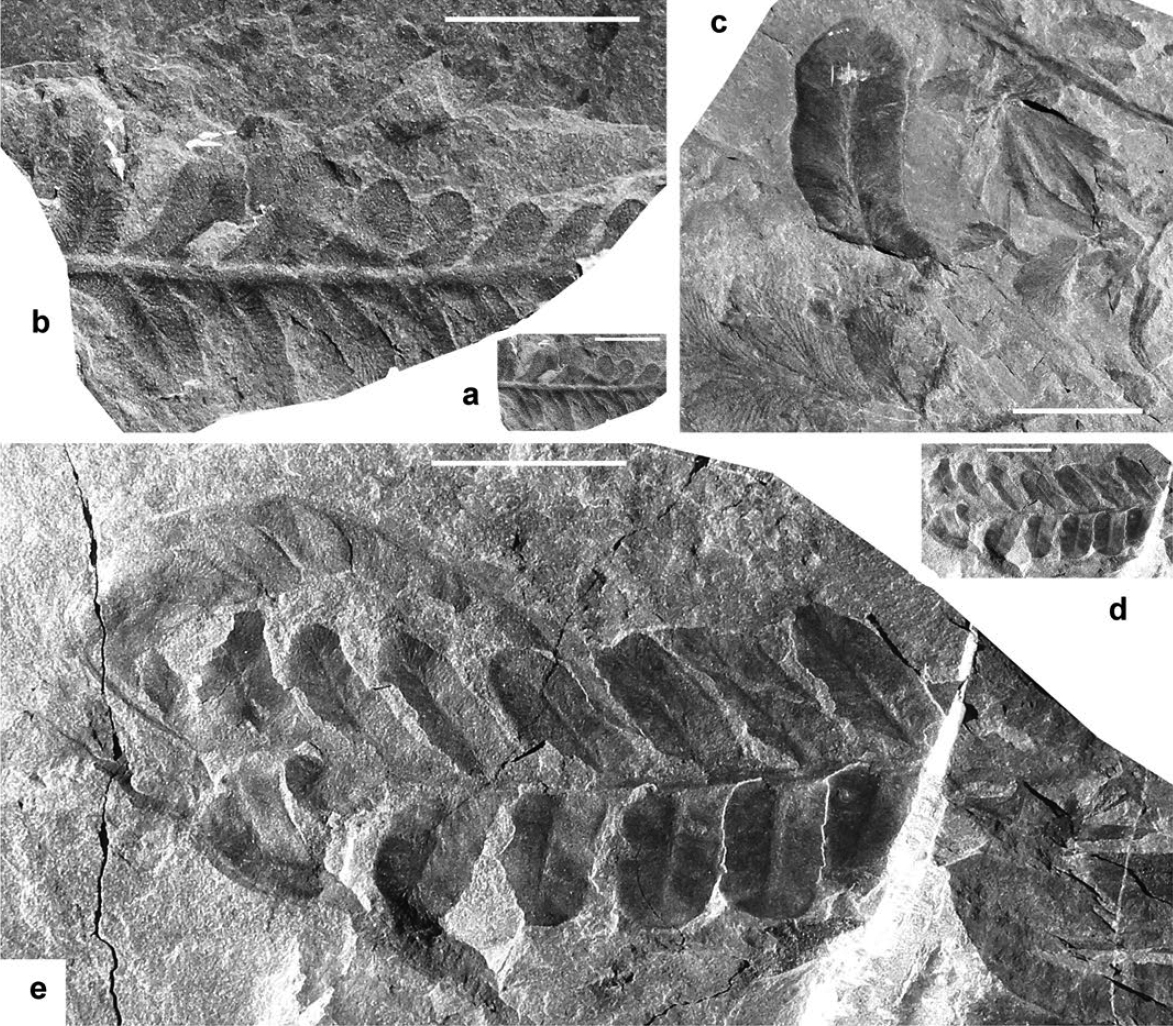

55 Description. Frond at least bipinnate. Penultimate order rachis straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.75 mm wide. Last order pinnae subrectangular, inserted at 60–80º. Last order rachis straight, rounded, longitudinally striate, ca. 0.25 mm wide. Pinnules alternate, closely spaced, either oblong, with cordate base, or rounded and broadly attached to the rachis. Dimensions: up to 30 mm long and 6–8 mm broad. Lamina thick, vaulted. Venation well-marked; in the smaller pinnules the midrib is not clearly differentiated and lateral veins, up to two times forked, depart directly from the rachis; in larger, more elongate pinnules the straight midrib extends in the lower two thirds of the pinnule and lateral veins are two (rarely three) times forked. Vein density = ca. 55 veins per centimetre.

56 Remarks. Neuralethopteris pocahontas is a very variable species that, according to Gillespie et al. (1978), grades morphologically into Neuralethopteris smithsii. Although Goubet et al. (2000) also noted that it is difficult to distinguish these two species in eastern North America, they did not follow Williams’s (1937) proposal to synonymize the two taxa (along with Neuralethoperis schlehanii), citing stratigraphic and geographic differences.

57 I include in Neuralethopteris pocahontas all the specimens from Nova Scotia previously figured and described by Bell (1944) as Neuropteris smithsii and that figured by Bell (1966) as Crossotheca pinnatifida (= Remia pinnatifida ― an upper Stephanian species). Bell (1944) records Neuralethopteris smithsii from 18 localities, but all his figured specimens are from locality 1392, Inverness County, Cape Breton Island. This focus is possibly due to poor and/or fragmentary preservation in all other localities, an explanation supported by the fact that most of the material that I have reviewed is very fragmentary.

58 Neuralethopteris pocahontas is usually recorded from fragmentary ultimate or penultimate order pinnae, thus preventing an understanding of its frond architecture.

59 Comparisons. Larger, more elongate pinnules of both Neuralethopteris pocahontas and Neuralethopteris smithsii have similar size and shape; but lateral veins in the latter reach the pinnule margin at approximate right angles, in contrast to an obtuse angle in Neuralethopteris pocahontas. In addition, the smallest pinnules of Neuralethopteris pocahontas do not show a clearly differentiated midrib, and veins emanate directly from the rachis. Neuralethopteris pocahontas has superficial similarities with some specimens of the recently described Wagneropteris minima. The latter also has ovoid to subrectangular pinnules, commonly attached by a short, broad stalk; but the first anadromous and catadromous pinnules of last order pinnae are shorter than the standard laterals, allowing space for intercalary pinnules on the penultimate rachis.

60 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Goubet et al. (2000) recorded Neuralethopteris pocahontas as very common in lower Langsettian strata of the Pocahontas Formation in West Virginia, occurring in nearly all known plant fossil localities. The type material is from Pottsville, Southern Anthracite Field, Appalachian Basin, where Blake et al. (2002) reported the species as endemic. Prior to the present work, Neuralethopteris pocahontas has been reported only from the United States.

61 Occurrence in the Maritime Provinces, Canada. Cumber-land Basin (Nova Scotia): Bell (1944): locality 1392 (GSC 3089 + GSC 9361 + GSC 9362 + GSC 9363 + GSC 9365); New Brunswick: Bell (1966): locality 887 (GSC 6627 + GSC 6632 + GSC 6638 + GSC 6639 + GSC 6643 + GSC 6644 + GSC 15040).

62 Occurrence in the United States. Alabama: White (1900), Gastaldo (1985), Gillespie and Rheams (1985), Dilcher and Lott (2005), Dilcher et al. (2005). Georgia: Gillespie and Pfefferkorn (1976), Pfefferkorn and Gillespie (1977), Gillespie et al. (1978), Gillespie et al. (1989). Pennsylvania: White (1900), Goubet et al. (2000). Utah: Tidwell (1967). Virginia: Pfefferkorn and Gillespie (1977), Gillespie et al. (1978), Gillespie and Pfefferkorn (1979), Pfefferkorn and Gillespie (1981), Gillespie and Pfefferkorn (1986), Blake et al. (2002). West Virginia: White (1900), Read and Mamay (1964), Gillespie et al. (1966), Pfefferkorn and Gillespie (1977), Gillespie et al. (1978), Pfefferkorn and Gillespie (1981), Gillespie and Pfefferkorn (1986), Blake (1997), Goubet et al. (2000).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur 1877) Cremer 1893

(Figs. 9a–d)

-

- * ? 1871 Neuropteris Selwyni Dawson, p. 50, pl. XVII, fig. 198 (schematic drawing — synonymy first proposed by Stopes 1914).

- * 1877 Neuropteris Schlehani Stur, p. 289 [183], Taf. XI [XXVIII], figs. 7–8c.

- * 1877 Neuropteris Dluhoschi Stur, p. 289 [183]–290 [184], Taf. XI [XXVIII], fig. 9 (acc. to Zeiller 1888).

- 1877 Neuropteris microphylla Brongniart; Heer, p. 24, Taf. V, fig. 6a; Taf. VI, figs. 1–9.

- * p 1879–84 Neuropteris Elrodi Lesquereux, p. 107–108, pl. XIII, fig. 4 (acc. to Zeiller 1888); non p. 735–736, pl. XCVI, figs. 1–2 (= Neuralethopteris biformis acc. to Goubet et al. 2000).

- § 1893 Neuralethopteris Schlehani (Stur) Cremer, p. 33.

- ? 1914 Neuropteris Selwyni Dawson (? Neuropteris Schlehani Stur); Stopes, p. 64–66, pl. XV, fig. 37 (photograph of Dawson’s holotype — fragmentary and poorly preserved); text-fig. 12 (drawing).

- 1934 Neuropteris dluhoschi Stur; Read, p. 81, 83–84, pl. 17, fig. 5.

- 1937 Neuropteris Schlehani Stur; Jongmans, p. 402, 403, 412, pl. 21, fig. 44; pl. 22, figs. 48–49 (together with Aulacotheca).

- 1941 Neuropteris Dluhoschi Stur; Arnold, p. 59, pl. I, figs. 3–4.

- v 1944 Neuropteris schlehani Stur; Bell, p. 79, pl. XXX, fig. 3; pl. XXXII; pl. XXXIII, figs. 5–6. 1947 Neuropteris Schlehani Stur; Arnold, p. 220, fig. 105B.

- 1949 Neuropteris Schlehani Stur; Arnold, p. 199–201, pl. XXIV, fig. 7 (same as Arnold 1947, fig. 105B), figs. 8, 9; pl. XXIV, fig 10.

- * 1952a–53 Neuropteris schlehanoides Stockmans and Willière, p. 233, pl. XXXI, figs. 3–3a, 7y; pl. XXXVI, fig. 2 (acc. to Cleal and Shute 1995).

- 1957 Neuropteris schlehani Stur; Leggewie and Schonefeld, p. 13–15, Taf. 4, Abb. 1–5; Taf. 5, Abb. 1–4; Taf. 6, Abb. 1–4; Taf. 7, Abb. 1.

- 1960 Neuropteris parvifolia Stockmans; Jongmans, p. 61, Taf. 23, figs. 127–127a (photograph of Heer’s 1877, Taf. VI, fig. 3), figs. 128–128a (same as Heer, 1877, Taf. VI, fig. 4), figs. 129–130a.

- v 1966 Neuropteris schlehani Stur; Bell, pl. IV, fig. 7 (counterpart of Bell 1944, pl. XXXIII, fig. 5), fig. 12; pl. V, fig. 9; pl. VI, fig. 5 (same as Bell 1944, pl. XXXII).

- 1967 Neuralethopteris schlehani (Stur) Cremer; Laveine, p. 113–120 (including synonymy), pl. V, figs. 1–3b; pl. VI, figs. 1–4; pl. VII, figs. 1–3a; pl. VIII, figs. 1–4a; text-fig. 18.

- * 1977 Neuropteris rectinervis f. obtusa Tenchov, p. 59–60, Taf. XX, figs. 3–4 (acc. to Cleal and Shute 1995).

- * 1977 Neuropteris lata Tenchov, p. 60, Taf. XXI, figs. 2–3 (acc. to Cleal and Shute 1995).

- * 1977 Neuropteris longifolia Tenchov, p. 61, Taf. XXI, figs. 4–7, 9 (acc. to Cleal and Shute 1995) (all specimens figured and described by Tenchov as Neuropteris rectinervis f. obtusa, Neuropteris lata and Neuropteris longifolia originated from localities where that author also records Neuralethopteris schlehanii).

- 1984 Neuropteris schlehani Stur; Jennings, p. 307, pl. 4, fig. 1.

- p 1985 Neuralethopteris schlehani (Stur) Cremer; Lyons et al., p. 232, pl. VI, figs. c–d; pl. XI, fig. d; non pl. XIV, fig. c (= Neuralethopteris biformis acc. to Goubet et al. 2000).

- 1985 Neuralethopteris schlehani (?) (Stur) Cremer; Lyons et al., p. 232–233, pl. X, fig. c.

- 1985 Neuropteris pocahontas cf. var. inaequalis White; Lyons et al., p. 219, pl. VI, fig. g (acc. to Goubet et al. 2000).

- 1985 Neuropteris cf. schlehani Stur; Gillespie and Crawford, p. 252, 255, pl. III, fig. 7.

- 1985 Neuropteris pocahontas White; Gillespie and Rheams, p. 194, 196, 199, pl. II, fig. 7 (acc. to Goubet et al. 2000).

- 1995 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Cleal and Shute, p. 24 (including synonymy), fig. 8 (p. 13).

- 1996 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Brousmiche Delcambre et al., p. 83, pl. 3, figs. 3–6a; pl. 7, figs. 1–8; pl. 8, figs. 1–3; pl. 10, fig. 11.

- 1997 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Blake, p. 84, 85, 90, pl. 3, fig. 8; pl. 8, figs. 1–2; pl. 9, fig. 5; pl. 10, fig. 2.

- 1998 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Brousmiche Delcambre et al., p. 106–107, pl. 12, figs. 1–12; pl. 13, figs. 1–4.

- 2000 Neuralethopteris schlehani (Stur) Cremer; Goubet et al., p. 15–18 (including synonymy), figs. 4.1–4.2; figs. 5.1–5.2, 5.7–5.8.

- 2002 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Blake et al., p. 264, 268, 269, pl. XV, figs. 7–8.

- p 2002 Neuropteris bulupalganensis Zalessky; Blake et al., p. 263, 289, pl. XIII, fig. 9; non p. 288, pl. XIII, fig. 3 (= Senftenbergia aspera).

- 2010 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Tenchov and Cleal, p. 301, 303, pl. I, figs. 1–2.

- v 2010 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez, p. 254, 257, 258, pl. VI, fig. 1.

- 2014 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Bashforth et al., p. 247, pl. III, figs. 2, 5, 8.

- 2018 Neuralethopteris schlehanii (Stur) Cremer; Lyons and Sproule, p. 319, figs. 3a–b.

- Excludenda:

-

- 1985 Neuropteris schlehani Stur; Gillespie and Rheams, p. 194, 196, 199, pl. II, figs. 9–10 (= Neuralethopteris biformis acc. to Goubet et al. 2000).

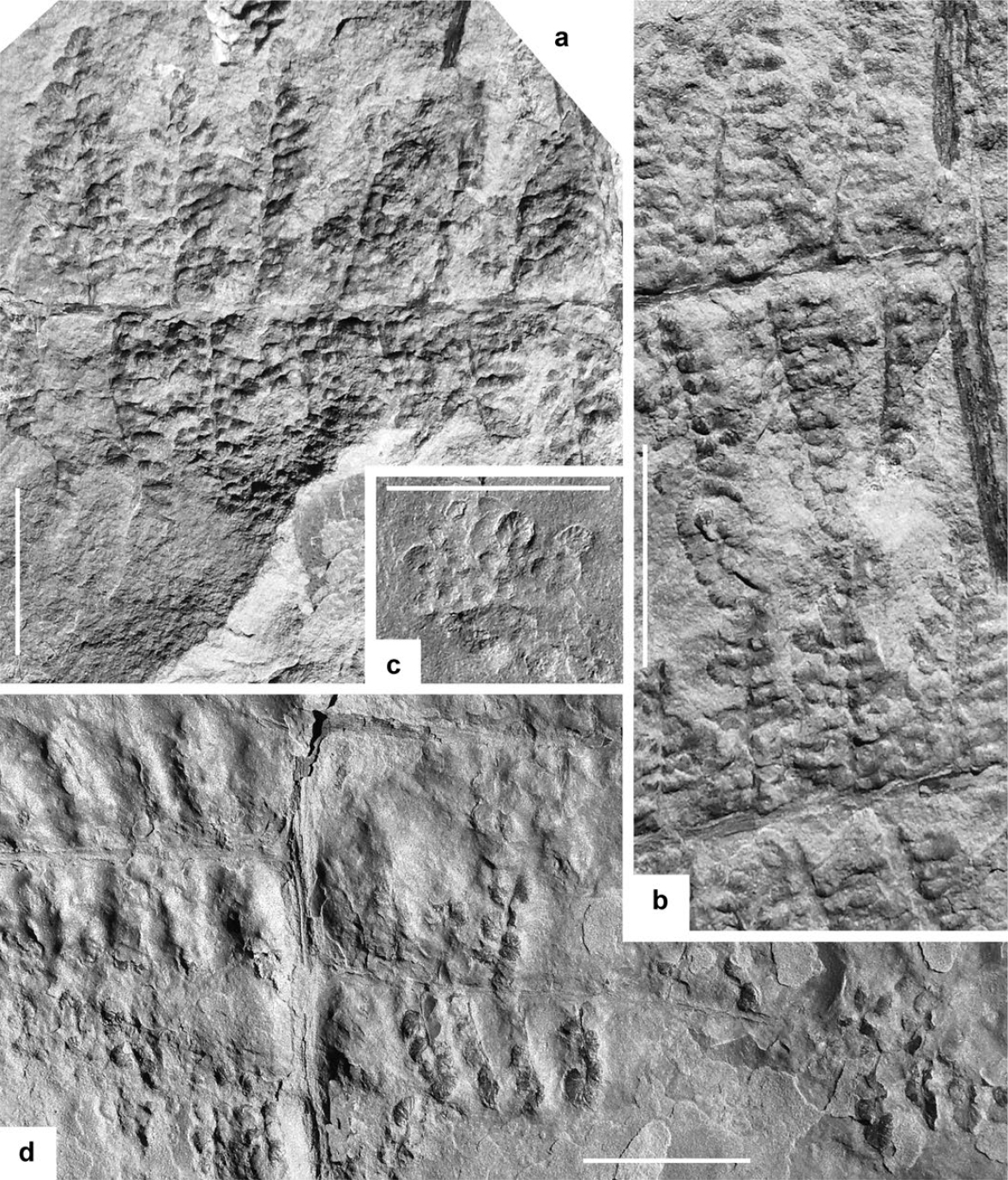

63 Description. Frond at least bipinnate. Penultimate order pinnae apparently lanceolate, with an approximately constant width in the lower three quarters, then quickly tapering to form an acute apex. Dimensions: up to 160 mm long and 150 mm wide. Penultimate order rachis straight, longitudinally striate, ca. 1.25–1.50 mm wide. Last order pin-nae alternate, closely spaced or slightly touching each other by their margins; subrectangular, elongate, with subparallel margins; apical pinnule lanceolate to oval, small but longer than the adjacent laterals. Dimensions: 30–110 mm long and 6–15 mm wide; length/breadth ratio = 5–6.5. Last order rachis inserted at 50–75º, longitudinally striate, rounded, ca. 0.5–0.75 mm. Pinnules alternate, close, subperpendicular or obliquely inserted (45–60º), of fairly constant size along the pinna; the larger ones are subrectangular, elongate, with subparallel margins, obtuse apex and cordate base, attached to the rachis throught a short stalk; smaller pinnules are subtriangular to ovoid, with cordate base, except in the apical parts of pinnae where they are more broadly united to the rachis. Dimensions: 4–14 mm long and 1.5–3.5 mm broad; length/breadth ratio = 2.5–4. Lamina thick, vaulted. Venation clearly marked. Midrib thick, straight, distinct in the lower three quarters of the pinnule length. Lateral veins thin, usually twice forked, the first fork occurring near the midrib, the second about half-way between the midrib and the margin; lateral veins reaching the pinnule margin with 75–85º. Vein density = 40–50 veins per centimetre.

64 Remarks. Specimens figured as Neuropteris schlehanii by Bell (1944, 1966) confirm the presence of this species in the Maritime Provinces. This is particularly the case for the well-preserved terminal of antepenultimate order pinna figured from the roof shales of coal nº 1 at Springhill, Nova Scotia (Bell 1944, pl. XXXII; Bell 1966, pl. VI, fig. 5), which shows the characteristic medium-sized pinnules with cordate base, broadly rounded apex and subparallel margins. Neuralethopteris schlehanii is found also in association with White’s Whittleseya brevifolia (male synangium) in several localities.

65 Dawson’s (1871) fragmentary type of Neuropteris selwynii, a poorly preserved fragment of last order pinna show-ing only four pinnules, was photographically illustrated by Stopes (1914, pl. XV, fig. 37), who suggested its synonymy with Neuropteris schlehanii. This synonymy was accepted by Bell (1944) who stated that Dawson’s Neuropteris selwynii is merely an “aberrant” form of Neuropteris schlehanii. Bell (1944) also included Kidston’s Neuropteris rectinervis (= Neuralethopteris rectinervis) in synonymy with Neuropteris schlehanii. In contrast, Laveine (1967) includes Stopes’s illustration of Neuropteris selwynii in the synonymy of Neuralethopteris rectinervis; and Tenchov and Cleal (2010) compare the venation pattern of Neuropteris selwynii with that of Neuralethopteris jongmansii.

66 I have not been able to review Dawson’s holotype of Neuropteris selwynii, so it is only questionably included in the synonymy of Neuralethopteris schlehanii. If it were proved that Neuropteris selwynii and Neuralethopteris schlehanii are cospecific, Dawson’s name would take priority. Although Stur’s type material of Neuropteris schlehanii is also fragmentary, consisting three fragments of last order pinnae without apical pinnules, the use of the name Neuralethopteris schlehanii should justify the proposal for conservation of the latter name should the synonymy be confirmed (see also Tenchov and Cleal 2010).

67 Comparisons. The larger pinnules of both Neuralethopteris pocahontas and Neuralethopteris schlehanii are similar. However, the smaller pinnules ― rounded, broadly attached to the rachis and without clearly differentiated midvein ― are common and characteristics in Neuralethopteris pocahontas but absent in Neuralethopteris schlehanii. Neuralethopteris jongmansii has longer and broader pinnules and more regular venation, both in terms of curvature and density. Pinnules of Neuralethopteris biformis are more subtriangular, with margins gradually tapering in the distal two thirds. In addition, the venation Neuralethopteris biformis is coarse, with lateral veins twice or occasionally three-times forked, reaching the margin at an angle of about 60°.

68 Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Neuralethopteris schlehanii is the most abundant and widely distributed species of Neuralethopteris over the paleoequatorial belt. It ranges in age from upper Namurian A to basal Duckmantian. The type material is from Vítkovice, Upper Silesian Basin, Czech Republic (Stur 1877). The species is common in Langsettian strata of Great Britain (Crookall, 1955). In France, Laveine (1967) recorded it from Westphalian A (Langsettian) strata of Nord/Pas-de-Calais, and Brousmiche Delcambre et al. (1996, 1998) from the Namurian B and C of Briançon. The species was recorded in Belgium from the upper part of the Namurian A up to the top of Westphalian A (Langsettian; Stockmans and Willière 1952a–53, 1952b). In the Iberian Peninsula, Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2010) recorded Neuralethopteris schlehanii from middle Namurian strata of the central Pyrenees, from the upper Namurian of La Camocha Coalfield of northwestern Spain, from the Langsettian of different localities in the Cantabrian Mountains of northwestern Spain, and from upper Langsettian strata of the Peñarroya-Belmez-Espiel Coalfield of southwestern Spain. Tenchov and Cleal (2010) reported the species in Langsettian and basal Duckmantian strata of the Dobrudzha Coalfield of Bulgaria.