Articles

The geology and hydrogeology of buried bedrock valley aquifers on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia:

an overview

ABSTRACT

Buried bedrock valley aquifers are common across Canada, where multiple glaciations have buried both pre-glacial and Pleistocene valleys. These aquifers are becoming increasingly important as a supply of potable groundwater, for supporting aquatic habitat, and as part of strategies in adapting to a changing climate. However, in Canada, there are considerable knowledge gaps at national, regional, and local scales, such that many buried bedrock valleys remain unidentified or underexplored. Cape Breton Island provides a hydrogeological view into the roots of an ancient mountain range, now exhumed, glaciated, deglaciated, and tectonically inactive. Since the Cretaceous, a variety of geological processes have formed several buried bedrock valley aquifers over the island. These aquifers are important in providing municipal and commercial groundwater supplies, controlling mine dewatering, protection of salmonids, design and monitoring of waste disposal sites, and geotechnical investigations for infrastructure design. Of 150 sites assessed, 61% provided evidence of buried aquifers comprising unconsolidated sand and gravel of Cretaceous, Pleistocene, and Holocene ages. These sites provided the basis for five conceptual, 3-D hydrogeological block models. Three hydrogeological case studies provided further insight into the functioning of two of these models. Future studies should identify and characterize aquifers in high demand areas and/or those that support important riverine ecosystems. Research should focus on aquifer properties, groundwater-stream interaction, and the impact of changing climate with sea-level rise.

RÉSUMÉ

Les vallées aquifères enfouies dans le substrat rocheux sont répandues partout au Canada, où plusieurs glaciations ont enfoui à la fois des vallées préglaciaires et des vallées du Pléistocène. Ces aquifères deviennent de plus en plus importants comme sources d’alimentation en eau souterraine potable, pour le soutien de l’habitat aquatique et dans le cadre des stratégies d’adaptation à un climat changeant. Au Canada, toutefois, des lacunes considérables subsistent dans les connaissances qu’on en a à l’échelle nationale, régionale et locale, nombre de vallées n’ayant pas encore été localisées ou demeurant sous-explorées. L’île du Cap Breton présente un aperçu hydrogéologique des racines d’une ancienne chaîne de montagnes, maintenant exhumée, érodée par la glaciation et tectoniquement inactive. Depuis le Crétacé, divers processus géologiques ont formé plusieurs vallées aquifères enfouies dans le substrat rocheux sur l’île. Ces aquifères sont importants, car ils représentent des réserves d’eau souterraines municipales et commerciales, permettent le contrôle de l’assèchement des puits de mines, assurent la protection des salmonidés et servent à la conception et à la surveillance des sites d’enfouissement ainsi qu’aux études géotechniques réalisées pour la conception des infrastructures. Soixante et un pour cent des 150 emplacements évalués ont fourni une preuve d’existence d’aquifères enfouis constitués de sable et de gravier non consolidés remontant au Crétacé, au Pléistocène et à l’Holocène. Ces emplacements ont servi de fondement à cinq modèles conceptuels tridimensionnels de blocs hydrogéologiques. Trois études de cas hydrogéologiques ont permis de comprendre plus en détail le fonctionnement de deux des modèles. Les études futures devraient tenter avant tout de localiser et caractériser les aquifères dans les secteurs à forte demande ou ceux soutenant des écosystèmes riverains importants. Les recherches devraient être axées sur les propriétés des aquifères, l’interaction entre l’eau souterraine et les cours d’eau, ainsi que l’incidence des changements climatiques et de la hausse du niveau de la mer.

[Traduit par la redaction]

INTRODUCTION

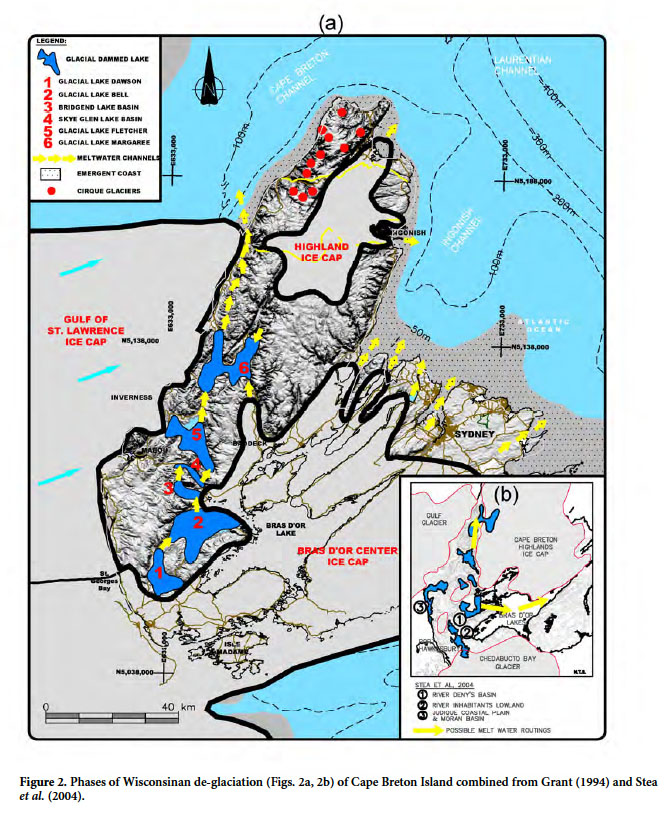

1 Buried bedrock valley (BBV) aquifers are common across the formerly glaciated terrain of North America (Grasby et al. 2014) and Europe (King 1980), created by multiple glaciations, and formed in pre-glacial and Pleistocene valleys (Upson and Spencer 1964; Denne et al. 1984; Faunt et al. 2010; Pugin et al. 2014; Russell et al. 2004; Seyoum and Eckstein 2014). This type of aquifer is commonly high yielding and readily recharged by rapid infiltration from precipitation and permeable streams. As such it forms an important supplier of potable groundwater to many cities in North America and Europe, but it is also highly susceptible to contamination (Springer and Blair 1992). The importance of channel-aquifer interactions is recognized in supporting benthic invertebrates and salmonids, as well as in controlling large-scale hyporheic floodplain corridors (Stanford and Ward 1993).

2 Recognition of the importance of BBV aquifers in Canada prompted their mapping in Alberta (Beaney and Shaw 2000; Morgan et al. 2008; Cummings et al. 2012; Atkinson et al. 2013), Saskatchewan (van der Kamp and Maathuis 2012), the Canadian Prairies (Pugin et al. 2014), Ontario (Flint and Lolcama 1986; Kor et al. 1991; Brennand and Shaw 1994; Russell et al. 2001; Meyer and Eyles 2007; Cole et al. 2009; Gao 2011), British Columbia (Hickin et al. 2008), the Northwest Territories (Rampton 2000), and eastern Canada (Randall et al. 1988; Butler et al. 2004; Tawil and Harriman 2001; Rivard et al. 2008).

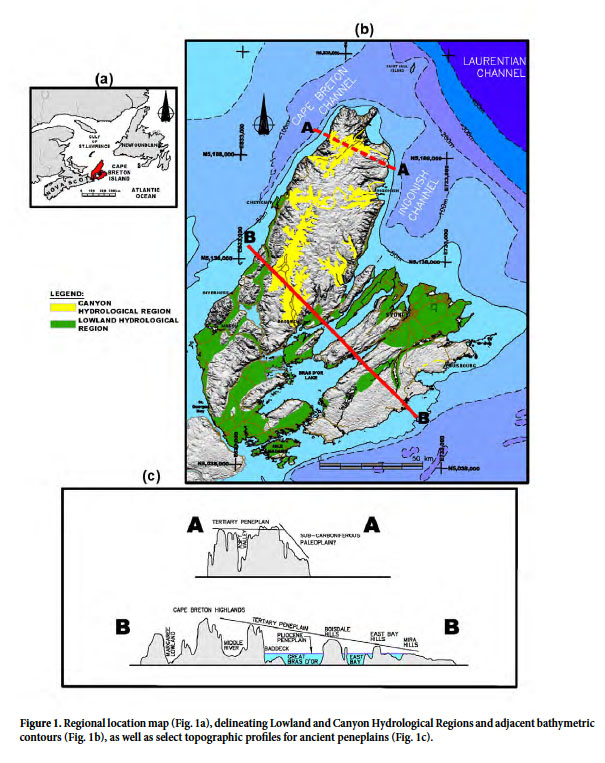

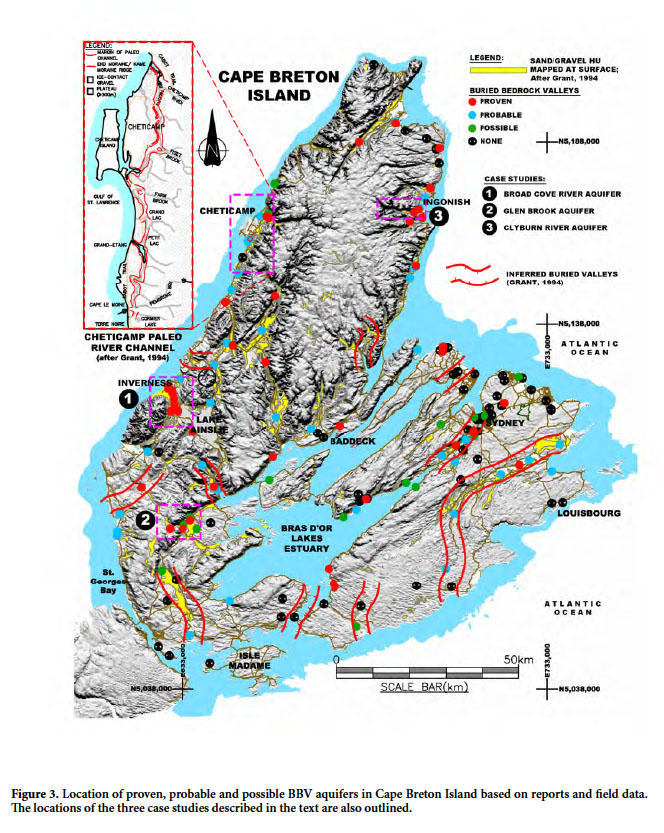

3 Cape Breton Island forms the northeastern part of the Province of Nova Scotia, along the Atlantic seaboard of Canada (Fig.1a). It encompasses an area of approximately 11 700 km2 and faces the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the north and west (Fig.1b). Although BBV aquifers have not been comprehensively mapped on Cape Breton Island, the author’s experience indicates that they have played a role in: (1) developing potable groundwater supplies for towns and commercial ventures, (2) providing irrigation waters for golf courses, (3) design of disposal sites, (4) regional water resource evaluations, (5) investigating groundwater stream interaction as it influences salmonid habitat, (6) environmental impact assessments, (7) predicting and controlling inflows to mines, and (8) geotechnical investigations for transportation corridors, infrastructure, and dams. The valleys they underlie have, for over 100 years, provided lands for farming, aggregate extraction, major traffic corridors, and suburbanization.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

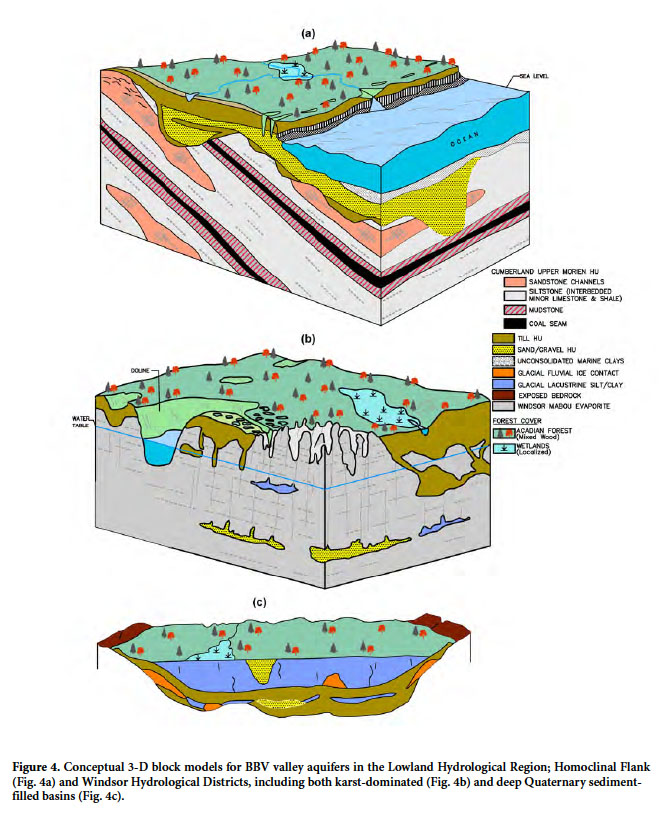

4 This paper is the fifth in a series that describes what is presently understood about Cape Breton Island’s fresh water resources to aid in their effective management. A review of Cape Breton Island’s paleohydrology, outlining the timing and formation of BBV aquifers, a description of the present hydrological setting of the island, and a description of known BBV aquifers, including three detailed hydrogeological case studies are presented. Much of the data provided in the case studies comes from over 130 consultant studies which, for the most part, constitute privately funded work carried out for a variety of municipal, industrial, mining, transportation, and commercial clients over the past 40 years. While the associated reports are referenced, they have been submitted to clients, and in some instances to Provincial regulatory agencies in support of permit applications. This “grey’ literature is not available in peer-reviewed journals, nor for the most part available to the reader. Nevertheless, the importance of this applied research is becoming recognized in establishing a base for groundwater knowledge management (Holysh and Gerber 2014).

GEOLOGY AND PALEOHYDROLOGY

5 Cape Breton Island’s ca. 1 Ga geological history created a complex lithological and structural terrain through plate collision, mountain building, regional scale faulting, sedimentary basin formation, karstification, the opening of the Atlantic Ocean, prolonged exhumation, multiple glaciations, and variable sea levels, which is now molded by a maritime climate. Exhumation and glaciation over approximately 140 Ma since the Early Cretaceous is of particular relevance to the formation of BBV aquifers.

6 Mesozoic erosion created a broad, lowland peneplain of the Appalachian mountain chain within which Cape Breton Island is located (Pascucci et al. 2000). The deposition of Cretaceous sediments in fault-bound basins and karstified paleosurfaces (Stea and Pullan 2001; Falcon-Lang et al. 2007) indicates that most of the present topography is a Mesozoic structural remnant and provides for one type of BBV aquifer on Cape Breton Island.

7 During the Cenozoic, sea level declined at times to at least 200 m below present level and the Mesozoic peneplain was uplifted and tilted to the east (Nova Scotia Museum 1997). During the subsequent erosional cycle, resistant crystalline basement rocks became more prominent on the landscape, while the softer sedimentary rocks created the lowlands. Grant (1994) noted that this exhumation provided the present island landscape with two major planation surfaces (Fig. 1c). The Paleogene/Neogene (Tertiary) peneplain slopes southeast and maintains its identity as a geomorphic feature across the entire island from the western Cape Breton highlands at over 500 m to the east coast at 30 m. It is incised by a system of “V”-shaped gorges and “U”-shaped canyons that likely predate the last glacial maximum (Grant 1994). A younger Pliocene peneplain comprises a network of interconnected lowlands ranging from 10 to 200 m elevation, developed mainly on Carboniferous sedimentary rocks (Grant 1994).

8 Approximately 16 major glacial periods have been estimated for Cape Breton Island over the past ca. two million years (Stea et al. 2003), affording ample opportunity for further development of BBV aquifers. The island’s Wisconsinan glacial history is complex and under repeated refinement. It comprised interaction between the Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) and an independent Appalachian Ice Complex (AIC). The interplay of sea-level change, ice-sheet stability, and isostatic/eustatic variations within a lithologically and topographically diverse terrain facilitated creation of BBV aquifers. The glacial history pertinent to BBV aquifer formation is summarized below from Grant (1994), Stea et al. (1998, 2003, 2006), Shaw et al. (2002), and Shaw (2005).

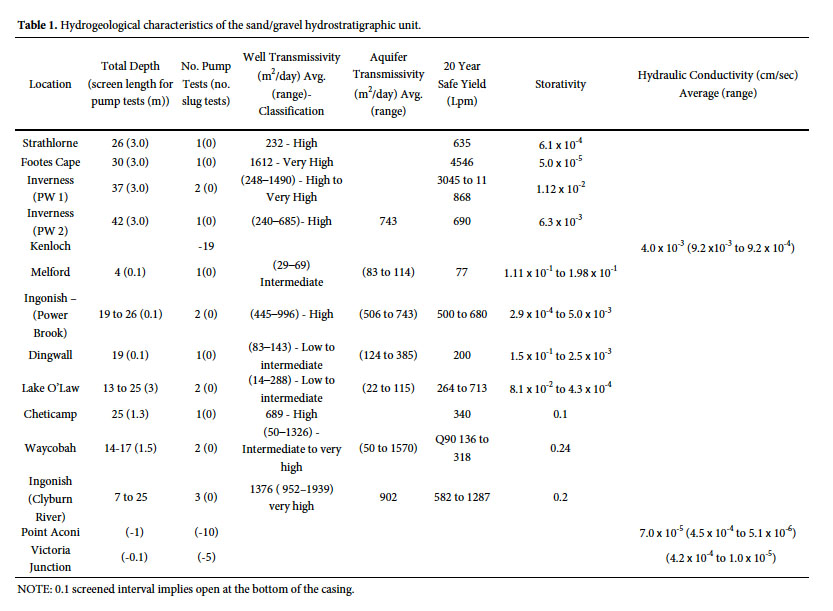

9 Initially an ice cap formed over the Cape Breton Highlands, followed by a northeastward flow from the AIC over the southern lowlands (75 to 40 ka), during which time sea level was placed at approximately -100 m (Grant 1994). From 22 to 15 ka a dominant ice sheet moved southeastward over the Island covering the highlands and extending onto the continental shelf. By 13.5 ka the LIS ice stream retreat in the Laurentian Channel caused re-organization to local centers including the Bras d’Or, Highlands, and Gulf of St. Lawrence (Fig. 2a). The latter ice sheet intermittently blocked westward meltwater drainage creating six proglacial lakes with interconnected, north-draining, meltwater spillways to Lake Margaree, and then through the Cheticamp meltwater channel to the ocean (Figs. 2a, 3). The period 12.5 to 10 ka saw both retreat and reactivation of the Bras d’Or and Highlands ice caps, creating outlet glaciers and spillway channels down major Canyon valleys such as the Aspy, Clyburn, Ingonish, Middle, Margaree, and Cheticamp. Localized cirque glaciers were developed in the northern highland peneplain. Lobes of the Bras d’Or ice centre extended north through St Anns Bay, the Great Bras d’Or, St. Andrews Channel, East Bay, and the Mira River after 10,300 BP. Blockage by southern ice lobes and Gulf ice created proglacial lakes Dawson and Bell (Fig. 2b), as well as the Moran-Hawthorne basin and Judique coastal plain (Fig. 2b). At 9 ka the emergent areas reached their greatest aerial extent with a sea level of approximately -50 m. This was followed by sea level rise which, after 6000 BP, resulted in inundation of drainage systems (Shaw et al. 2002) and presently continues to rise at 0.36 m/100 years (Grant 1994). Therefore, present-day streams represent the upper headwaters of large drainage systems whose channels and valleys now extend offshore.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

10 The formation of BBV aquifers is a topic of debate (Gray 2001; Boulton et al. 2007, 2009; Creyts and Schoof 2009; Kehew et al. 2012; Van der Vegt et al. 2012). During glacial advance the former subaerial groundwater flow systems are combined into a single, confined, sub-glacial system, creating flow from the interior to the ice margin (Lemieux et al. 2008; Kehew et al. 2012). The sub-glacial drainage system integrates channels and groundwater flow (Person et al. 2007; Kehew et al. 2012; Atkinson et al. 2013) through R channels, where meltwaters erode upward into the ice forming eskers, as well as N channels incised downward into poorly consolidated strata. During glacial retreat proglacial meltwater channels downstream of the ice terminus can infill existing valleys. The sedimentological processes active within these channels, coupled with localized glacial overriding and proglacial lakes, can create a wide variety of facies within the BBV aquifers (Upson and Spencer 1964; Kehew and Boettger 1986; Sharpe 1988; Broster and Pupek 2001; Rivard et al. 2008; Cummings et al. 2012). This complexity can create longitudinal and transverse hydraulic barriers and contrasting hydraulic responses (Kehew and Boettger 1986; Shaver and Pusc 1992; Russell et al. 2004; Weissmann et al. 2004; Van der Kamp and Maathuis 2012).

11 The three types of Quaternary aquifers, as defined by Wei et al. (2014), that are the most relevant for Cape Breton Island are: Type 1 (aquifers in unconfined fluvial or glaciofluvial sands and gravels), Type 3 (aquifers which occur in alluvial or colluvial deposits positioned near the base of mountain slopes), and Type 4 (pre-glacial or glacial-origin aquifers that occur at the surface or are buried under till or glaciolacustine deposits).

12 Regional surficial geological mapping of Cape Breton Island by Grant (1994) and Stea et al. (2006) identified glaciofluvial and ice-contact sands and gravels created by Wisconsinan glaciation, covering approximately 6.5 % of the Island (Fig. 3). These deposits are principally associated with large outwash plains in the Margaree, Baddeck, Middle, Mira, Aspy, Denys, and Inhabitants river valleys. Grant (1994) inferred the potential presence of 11 major buried valleys (Fig. 3) over the island. He also noted that the number of buried valleys, which can be seen and reasonably inferred in the heavily drift-covered areas of the island, point to the likelihood of others being found. Stea et al. (2006) identified localized sand and gravel in deep, drift-covered, lowland basins, confined between glacial tills and lacustrine clays. Submarine extensions of these features occur on the adjacent continental shelf and beneath the Bras d’Or Lake (Shaw 2005; Shaw et al. 2006, 2009; MacRae and Christians 2013).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

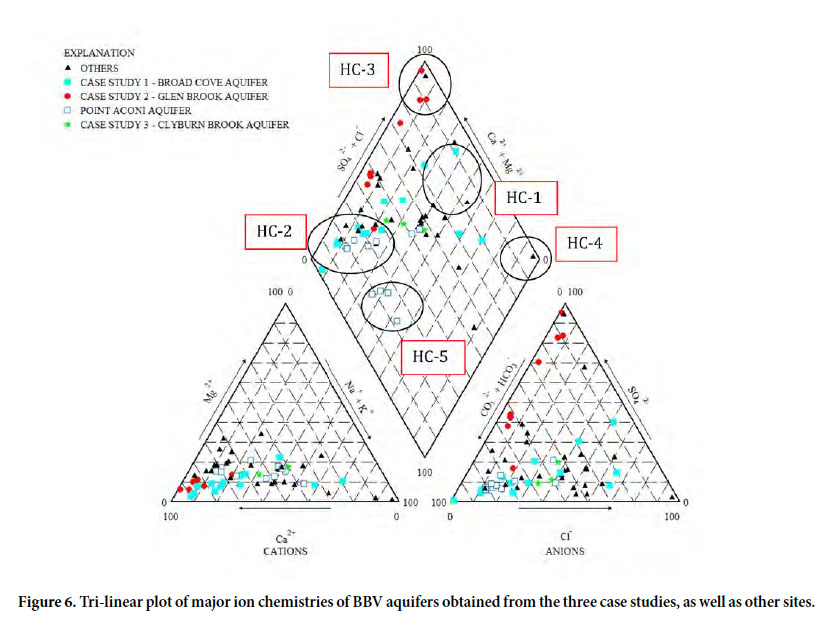

MODERN HYDROLOGICAL SETTING

13 Cape Breton Island has a temperate, humid, continental climate, with a 30-year normal (1981 to 2010) annual precipitation of 1517 mm, and mean annual temperature of 5.9° C. These conditions provide for an estimated annual water surplus and deficit using the method of Thornthwaite (1948) of 987 and 21 mm, respectively. Sharpe et al. (2014) positioned Cape Breton Island nationally in both the Appalachian and Maritimes Basin hydrogeological regions. Baechler and Baechler (2009) developed a regional classification, which mapped six hydrological regions over the island by defining areas with characteristic types, numbers and orientations of hydrostratigraphic units (HUs), coupled with climate, topographic relief, and forest cover.

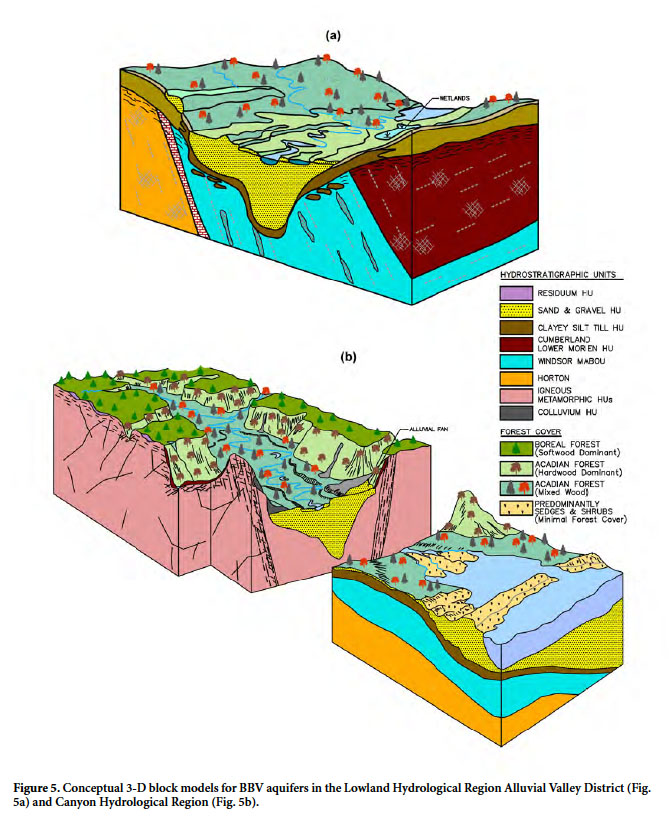

14 The Lowland and Canyon regions (Fig 1b) are relevant to the discussion of BBV aquifers. Representative 3-D block conceptual models (Figs. 4, 5) combine the approaches outlined by LeGrand and Rosen (2000), Bredhoeft (2005), Hill (2006), and Savard et al. (2014), which utilize generalizations and inferences with existing geological information to draw conclusions from imprecise and incomplete information. The models focus on the active groundwater flow system down to approximately 200 m depth, as defined by Mayo et al. (2003). The models are designed to meet the three goals of simplicity, refutability, and transparency. They should not be regarded as immutable and surprises will be inevitable as new concepts require refinements or a complete paradigm shift.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

15 The Lowland Hydrological Region (Fig. 1b) covers approximately 24% of Cape Breton Island. It comprises four hydrological districts developed over the Pliocene peneplain, including:

- The Sedimentary Plain and Homoclinal Flank Districts (Fig. 4a), are underlain by a variety of clastic sedimentary bedrock. The relief in this district is generally bedrock controlled with a thin veneer of glacial till, resulting in a smooth, undulating terrain with low relief knolls and valleys, covered by a mixed deciduous, coniferous Acadian Forest. Given the high water surplus, first-order flow systems (Toth 1962) dominate.

- The Windsor District (Fig. 4b) is found in the lowest relief areas, comprising easily erodible argillaceous clastics, evaporites and limestones. Karst is present in various stages of hydrologeological development (Baechler and Boehner 2014), including channels at depth infilled with sand and gravel (Fig. 4b). Underlying the deeper drift controlled lowlands of the River Denys, Inhabitants and Hawthorne/ Moran basins are isolated channel fills and/or eskers surrounded by thick sequences of fine grained tills and lacustrine clays (Fig. 4c).

- The Alluvial Valley District includes large river valleys which may be underlain by evaporite rocks and argillaceous clastic or arenaceous clastic sedimentary rocks (Fig. 5a).

- The Canyon Hydrological Region (Fig. 5b), which encompasses 8% of Cape Breton Island, is incised into the highland Paleogene/Neogene peneplain along large-scale fault systems in various stages of exhumation and hydrogeological development (Baechler 2015). The valley floors tend to be underlain by crystalline basement bedrock, while down valley and under estuaries this can transition to clastic sedimentary rocks and/or evaporite rocks. Coarse, unconsolidated sediments associated with colluvium, talus cones, and alluvial fans locally overlie the valley floor along steep valley flanks.

METHODS

16 The data compiled and presented in this study came from 150 sites distributed across Cape Breton Island (Fig. 3). A total of 2555 well records were reviewed, 30% of which were drilled for hydrogeological purposes, 25% for geotechnical studies, 3% for geological delineation, and 42% from the Nova Scotia Department of Environment’s (NSE) provincial water well database (http://novascotia.ca/natr/meb/download/dp430.asp). Additional data included results from 17 pumping tests, 46 slug tests, 240 grain-size analyses and 126 water chemical analyses within these aquifers. It is important to note that the spatial distribution of this database is not random. Wells were drilled on specific targets and can include clusters around select sites. Geotechnical investigations supporting bridge designs focus at the edge of present-day channels, which may not be positioned over any buried channel.

17 For the purposes of this paper BBVs are defined where previous drilling has indicated a depth to bedrock in excess of 10 m, regardless of the nature of infill. Sand and gravel aquifers were defined in these valleys using the following nomenclature: (1) “proven” where detailed lithological logs were available; (2) “probable” where domestic water wells with poor lithologic logs showed completion in overburden at depths exceeding 10 m; and (3) “possible” where shoreline exposures suggested the presence of such conditions, where detailed lithological logs intercepted localized sand and gravel units at depth in deep Quaternary basin fills but lateral continuity was unknown, and where thin, sheet-style sand and gravel units were documented with drilling to depth in bedrock, but an associated deeper channel was not found. Aquifer materials include Cretaceous unconsolidated fluvial deposits, Pleistocene glaciofluvial deposits and/or Holocene fluvial, colluvial, and alluvial fan sequences.

18 The data sets developed for this paper have been provided to the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources for inclusion in their water resources data base.

RESULTS

19 Of the 150 sites investigated, 61% exhibited evidence for a BBV aquifer, of which, 28% were “proven”, 24% “probable” and 9% “possible” (Fig. 3). Approximately 90% are associated with major river systems within the Canyon and Lowland Hydrological regions. Of the remaining sites, 5% are within deep Quaternary basin lowland fills, 2% are exposed along shorelines, and 3% are associated with infilled karst channels at depth in limestone, gypsum, and anhydrite. This information suggests that more BBV aquifers may exist than presently mapped.

20 A summary of transmissivities, storativity, 20-year safe yields from pumping tests, and hydraulic conductivities from slug tests are provided in Table 1. The classification of transmissivity follows Krasny (1993). Records for 17 pump tests were available for wells ranging from 4 to 37 m deep. Well transmissivity ranged from “low” to “very high” (14 to 1939 m2/d). A total of seven hydraulic tests had one or more observation wells, allowing calculation of an aquifer transmissivity, which ranged from 22 to 1570 m2/d. Generally, the “high” to “very high” range (232 to 1939 m2/d) is associated with gravel-dominated aquifers. Storage coefficients ranged from 2.0 x 10-1 to 5.0 x 10-3 with three semi-confined values ranging from 6.1 x 10-4 to 5.0 x 10-5. Thirty-four slug tests provided a range in hydraulic conductivity from 9.0 x 10-3 to 5.1 x 10-6 cm/sec. The lower end of the range is associated with N channels compacted by glacial overriding and interbedded till layers.

Display large image of Table 1NOTE: 0.1 screened interval implies open at the bottom of the casing.

Display large image of Table 1NOTE: 0.1 screened interval implies open at the bottom of the casing. 21 Representative water chemistries were available for 34 wells ranging in depth from 2 to 32 m. The inorganic chemical signature is summarized in a piper plot (Fig. 6). The groundwater chemistry exhibits wide variability in five hydrochemical (HC) facies. The initial input from recharge (HC-1) is similar to rainwater, encompassing shallow groundwater with a thin unsaturated zone, no overlying till, and/or in proximity to a stream channel. This grouping is characterized by relatively low total dissolved solids (TDS) ranging from 20 to 70 mg/L, a sodium chloride to sodium/calcium - chloride/bicarbonate type water, with slightly acidic pH (5.8 to 6.2). HC-1 transitions into the dominant core (HC-2) calcium bicarbonate type. This is characterized as a fresh (TDS ranging between 70 to 316 mg/L), hard (hardness as CaCO3 ranging between 40 and 225 mg/L), primarily corrosive water, with predominately alkaline pH (6.9 to 8.1) and alkalinity (as CaCO3) of 35 to 160 mg/L. There is a gradual transition from the core group to three other HCs. HC-3 and HC-4 are related to the influence of higher TDS (1000 to 3390 mg/L) waters in the deeper portion of the aquifers within regional groundwater discharge zones. They are influenced by underlying evaporite sequences, including calcium sulfate (HC-3) and sodium chloride-types (HC-4). HC-5 exhibits a trend toward a sodium bicarbonate, naturally softened water, associated with underlying mudstone-shale-coal sequences. Three hydrogeological case studies are outlined below to exemplify conceptual models for one of the Lowland Regions (Fig. 5a) and the Canyon Region (Fig. 5b).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

CAPE BRETON ISLAND HYDROGEOLOGICAL CASE STUDIES

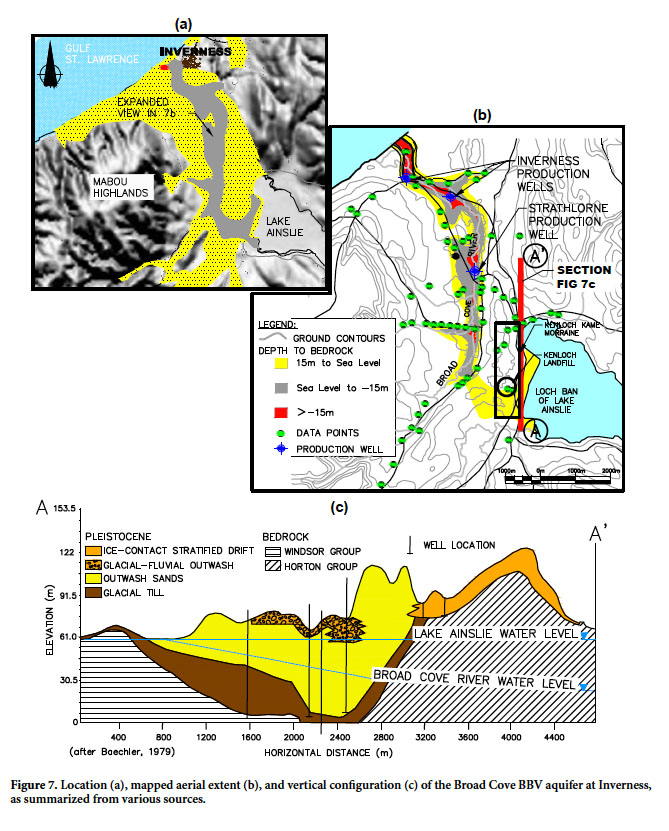

Case study 1: Broad Cove River Aquifer

22 The Broad Cove River Aquifer (Figs. 3 and 7) exemplifies an unconfined, Type I, BBV aquifer underlying a valley floor within the Lowland Hydrological Region, Alluvial Valley District (Fig. 5a). The mapped surface expression (Fig. 7a) ranges from 1 to 3 km in width and 13 km in length (Grant 1994). Its 37 km2 area is confined by smooth, low-slope valley flanks, which rise to uplands reaching 100 to 250 m above the valley floor. Land use historically comprised forestry and agriculture, and is now augmented by transportation corridors, commercial, suburban and rural use, a municipal landfill, a forest nursery, and a golf course. The Broad Cove River BBV aquifer is the largest, and arguably the second most heavily utilized, on Cape Breton Island.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

23 Hydrogeological investigations were originally undertaken to develop a groundwater supply for the Village of Inverness (Pinder 1966; ADI Ltd. 2002a) and the Strathlorne Forest Nursery (Baechler 1980). Hydrogeological investigations for the Kenloch landfill were undertaken by Baechler (1979), Nolan Davis Ltd. (1990), ADI Ltd. (2002b) and Exp Services Inc (2014). Kennedy (2014) provided a preliminary outline of the hydrogeology of the aquifer. The data comprised logs from 81 wells of which, 69% were detailed logs from groundwater, geotechnical, and geological studies and 31% were domestic water wells. Associated studies provided information from five pump tests, 19 slug tests, 32 grain size analyses, and 64 representative groundwater chemistries. Production wells (PW1 and PW2) for the Village of Inverness have been operating within this aquifer for 50 and 14 years, respectively; the Strathlorne Nursery well has been operational for 35 years (Fig. 7b). The narrowly incised bedrock channel (Fig. 7b) is positioned generally in the centre of the valley. The base of the channel at Inverness extends to depths of between 20.1 m (-14.5 m geodetic) and 40.0 m (-10 m geodetic).

24 The aquifer is sand dominated, with thin (1 to 2 m), localized beds of sand and gravel. No glacial till, lacustrine/ marine clays, or diamictons have been noted. The 3 km long, 0.5 to 0.9 m wide Kenloch kame moraine (Figs. 7b and 7c) overlies the buried channel and attains an elevation of some 60 m above the valley floor (Baechler 1979). The moraine is sand dominated with a diamicton and/or glacio-lacustine deposits positioned above the bedrock. Gravels locally overlie the sand under ridge knolls, with a sandy diamicton draped over the surface. Nineteen grain size analyses noted a slightly calcareous, fine sand with a distribution of gravel 0%, sand 70% (range 15–97%) and silt clay 30% (range 3–85%).

25 Production wells at depths of 26 to 30 m near Strathlorne screened in gravels provided transmissivities of 232 to 1612 m2/d, with storativity in the semi-confined range from 6.1 x 10-4 to 5.0 x 10-5. Further down valley the Inverness production wells at depths of 35 to 40 m, positioned in the centre of the channel, exhibited transmissivities of 248 to 1490 m2/d (PW1), and 240 to 685 m2/d (PW 2); with an aquifer transmissivity of 743 m2/d. The storativity ranged from 1.12 x 10-2 to 6.3 x 10-3. The hydraulic conductivity for kame moraine sand from 19 sites provided an average of 4.0 x 10-3 cm/sec, ranging from 9.2 x 10-3 to 2.0 x 10-4 cm/sec.

26 The water table is relatively shallow, (1 to 6 m) supporting the perennial streams, and a number of wetlands. However, the water table has been recorded at depths of 15 to 30 m below the crest of the adjacent kame moraine. This configuration allows Lake Ainslie to direct groundwater outflow through the BBV aquifer under the kame moraine (Fig. 7c) (Baechler 1979).

27 Groundwater stream interaction maintains the perennial Broad Cove River. At Strathlorne the 35.8 km2 watershed has created a 8 to 10 m wide, 101st Shreve stream order channel with a gradient of 0.2 to 0.3 %. At a Rosgen Level 1 (Rosgen and Silvey 1998), it is qualitatively classed as a C4 to C5 channel, exhibiting a riffle-run-pool morphology. The channel is incised generally 1 to 3 m into the aquifer.

28 Shallow groundwater chemistry below a 6 to 7 m unsaturated zone generally exhibits a fresh (TDS 20 to 30 mg/L), soft (3 to 8 mg/L as CaCO3), corrosive, sodium chloride-type water (Fig. 6), with a low pH (4.9 to 5.9) and total alkalinity (as CaCO3) ranging between <1 to 10 mg/L.

29 With an increase in unsaturated zone of up to 20 m, the chemistry exhibits an increase in TDS (97 to 260 mg/L) and hardness (70 to 140 mg/L as CaCO3), while changing to a calcium bicarbonate type water (Fig. 6) with a rise in pH (7.4 to 8.1) and total alkalinity (77 to 160 mg/L). Inverness PW2, positioned from near the base of the incised channel in a regional discharge zone, exhibits a fresh (TDS 445 mg/L), very hard (310 mg/L), encrusting calcium chloride-type water with a pH of 7.8 and total alkalinity of 118 mg/L.

30 Base metals at detectable concentrations in 13 samples included iron (0.02 to 0.45 mg/L), manganese (0.01 to 0.77 mg/L), barium (0.02 to 0.38 mg/L), copper (0.01 to 0.05 mg/L), zinc (0.01 to 0.18 mg/L), and strontium (0.01 to 0.4 mg/L). Arsenic was not detectable.

31 Historical forestry and agricultural land use has not impacted nutrient concentrations, as noted with nitrogen (nitrite +nitrate as N) at <0.05 to 0.58 mg/L. Radiologicals monitored at PW2 as represented by uranium (<0.0001 mg/L), gross alpha and beta (<0.1 Bq/L), and radon gas (18 Bq/L) were at low concentrations (ADI Ltd. 2002a). Although the “oil fields” of Cape Breton Island have been reported in the Inverness and Lake Ainslie areas (McMahon et al. 1986), hydrocarbons have not been detected at two background sites.

32 Ongoing monitoring of baseline hydrogeological conditions within this buried valley aquifer is localized and infrequent. Monitoring of background conditions (Exp Services Inc. 2017) once per year during late summer for 27 years (Fig. 8) has indicated no qualitatively, long-term trends in either water level or four indicator chemical parameters.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Case study two: Glen Brook Aquifer

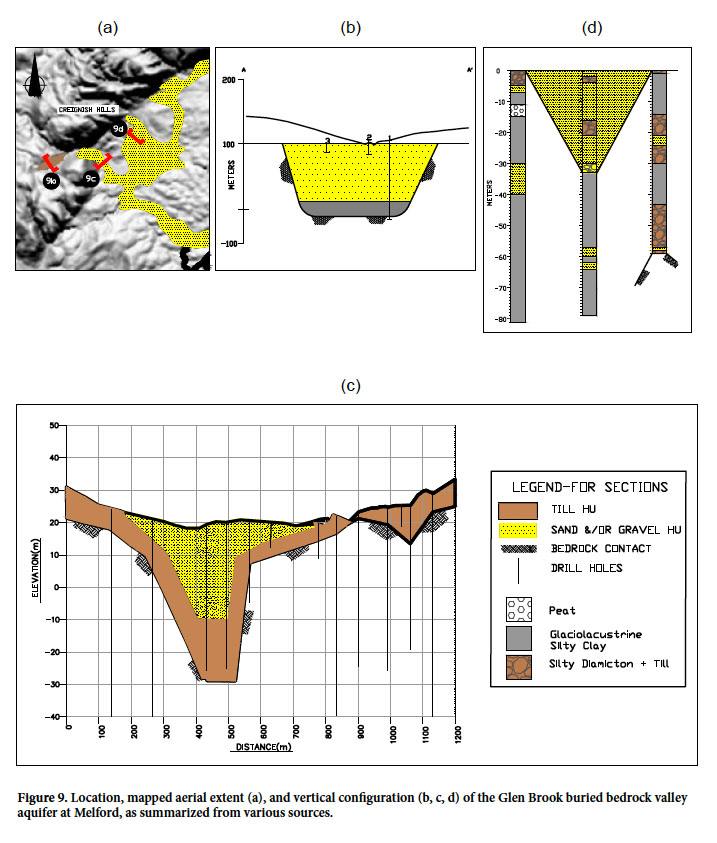

33 The Glen Brook Aquifer (Figs. 3 and 9) is similar to the Broad Cove River aquifer as it exemplifies a surficially mapped (Grant 1994; Stea et al. 2006), unconfined, Type 1 bedrock valley aquifer underlying a regional valley floor in the Lowland Hydrological Region, Alluvial Valley District (Figs. 5a and 9a). It is the most intensively studied BBV aquifer on the island. Its distinctive nature accommodates both Type 1 glaciofluvial deposits as well as Type 4 Cretaceous sands and clays. Upward regional flow into the base of the aquifer originates from evaporite deposits. Groundwater stream interaction provides critically important habitat for salmonids (ADI Ltd. May 2000). The Glen Brook Aquifer has provided an adjacent gypsum mine with its water supply for 14 years. Land usage above the aquifer was historically farming and forestry, but now includes mining, with headwaters in the Bornish Hills Nature Reserve.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

34 A 2.7 km reach of the Type 1 deposit was investigated as a salmonid management zone associated with development of an adjacent gypsum mine by Georgia Pacific Canada LP (ADI Ltd. 1999, 2000, 2001; Henley et al. 2009). The findings from this study comprise 69 well logs associated with groundwater, geotechnical, and geological studies, data from one pump test, 10 slug tests, 32 grain-size analyses, and representative groundwater chemistries. It also includes 19 years of interdisciplinary studies providing 177 stream discharge/stage and head levels at five wells, as well as 188 surface water chemistries.

35 The Type 4 deposit covers 0.14 km2 at the base of a steep-sided, V-shaped gorge (Fig. 9b). The deposit is approximately 700 m long by 200 m wide and up to 120 m deep, comprising 96 m of silica sand, underlain by 25 m of clay (Fig. 9b). The Type 1 deposit occurs beneath a broad valley floor, ranging in width from 100 to 800 m and some 2.2 km in length (Fig. 9c), covering approximately 0.9 km2. The northeast side of this broad valley is shallow, rising to approximately 25 m above the valley floor, exhibiting glacial till overlying karstdominated evaporite rocks. To the southwest, the valley is steep, rising to approximately 225 m above the valley floor and underlain by faulted sandstone and conglomerate. The aquifer reaches a depth of at least 30 m (-10 m geodetic), where it is underlain by at least an additional 15 m of till (Fig. 9c). The Type 1 deposit extends southeastward downstream of the study site, into the Denys Basin lowland, where an unconfined, sand-dominated channel (Fig. 9d), up to 30 m deep and bounded by a thick sequence of tills and lacustrine deposits, was mapped by Stea et al. (2006).

36 The glaciofluvial deposits are predominately well sorted, very fine sand with numerous, thin (1 to 30 cm) silt/clay lenses throughout. Sixteen grain size analyses indicate <0.5% gravel (ranging from 0 to 2%), 65% sand (3 to 99%) and 35% fines (1 to 97%). A near-surface gravel facies is on average, 2.0 m thick, ranging from 1 to 4 m, based upon 41 test pit locations. It generally comprises poorly sorted compact sand and gravel with no apparent stratification. A total of 11 grain-size analyses indicate 46% gravel (0 to 26%), 50% sand (30 to 70%) and 4% fines (4 to 12%). Hydraulic testing of a dug well within the gravel facies provided well transmissivities ranging from 29 to 69 m2/day and aquifer transmissivities ranging from 83 to 114 m2/d. Storativity ranged from 1.14 to 1.98 x 10-1. Three hydraulic conductivity values for the sand averaged 1 x 10-3 cm/sec. (ranging from 2 x 10-3 to 3 x 10-4 cm/sec). Seven hydraulic conductivity values for the gravel averaged 1.2 x 10-3 cm/sec (1.9 x 10-3 to 5.3 x 10-4 cm/sec).

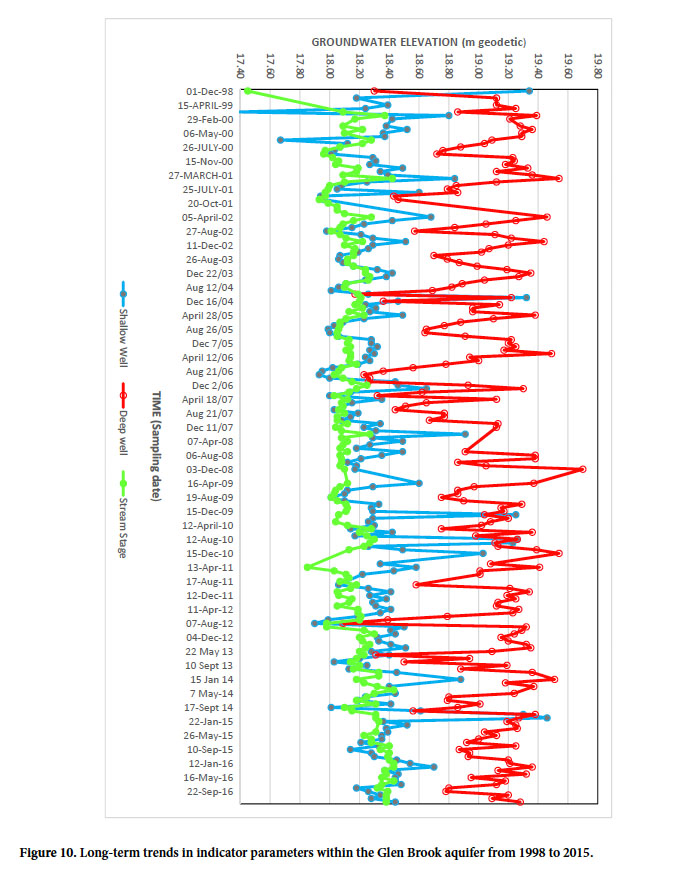

37 Groundwater-stream interaction is maintained by a high water table within the gravel facies, altered locally by beaver dams. One shallow well within 10 m of the main channel noted an effluent reach with continuous water levels above the stream channel (Fig. 10). The 16.8 km2 watershed has created a perennial, 8 to 12 m wide, 10th Shreve stream order channel with a gradient of 0.4 to 0.5%. At a Rosgen Level 1 (Rosgen and Silvey 1998) it is qualitatively classed as a C4 to C5 channel exhibiting a riffle-run-pool morphology with localized braided reaches. The large width/depth ratio (12 to 26) channel is incised 1 to 4 m into the aquifer. Groundwater discharge into effluent reaches of the channel ranged from 2 x 10-3 to 1 x 10-4 cm/sec per unit area of stream; with influent reaches also present (Henley et al. 2009). Active channel migration facilitates erosion of a gravel facies of the aquifer for re-distribution by bedload transport into riffle, runs, and pools, creating excellent habitat for benthic invertebrates to support salmonids (ADI Ltd. May 2000).

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

38 A total of seven representative groundwater chemistries collected at the water table indicated a fresh (TDS 70–454 mg/L), soft to hard (46 to 353 mg/L as CaCO3), corrosive to encrusting, mixed calcium-bicarbonate/sulfate-type water (Fig. 6), with a slightly alkaline pH (6.3 to 7.7) and total alkalinity of 44–131 mg/L. Near the base of the aquifer, the chemistry was altered by underlying evaporites creating a brackish (1060–1420 mg/L), very hard (803–935 mg/L), encrusting calcium sulfate-type water, with a slightly alkaline pH (7.7 to 7.8) and elevated total alkalinity (111– 120 mg/L). Base metals were above detection in most samples and included iron (<0.2 to 0.71 mg/L), manganese (<0.02 to 1.3 mg/L), zinc (<0.02 to 0.03 mg/L), aluminum (<0.01 to 0.46 mg/L), barium (<0.03 to 0.12 mg/L), boron (<0.05 to 0.51 mg/L), and strontium (0.16 to 4100 mg/L). Arsenic was consistently non-detectable. Nitrogen (nitrite+nitrate as N) as an indicator of previous agricultural and forestry practices was characterized by non-detectable to low concentrations (<0.05 to 0.10 mg/L). Uranium, as an indicator of radiologicals, was consistently detectable, but at low concentrations (0.0002 to 0.0016 mg/L). Total petroleum hydrocarbons have not been detected within stream channel under baseflow conditions during the 19-year monitoring period.

39 No monitoring occurs within the Type 4 Cretaceous deposit. Monitoring of the Type 1 glaciofluvial aquifer is localized and frequent (monthly). Nineteen years of monitoring has indicated no notable change in head level within the aquifer (Fig. 10).

Case Study 3 – Clyburn River Aquifer

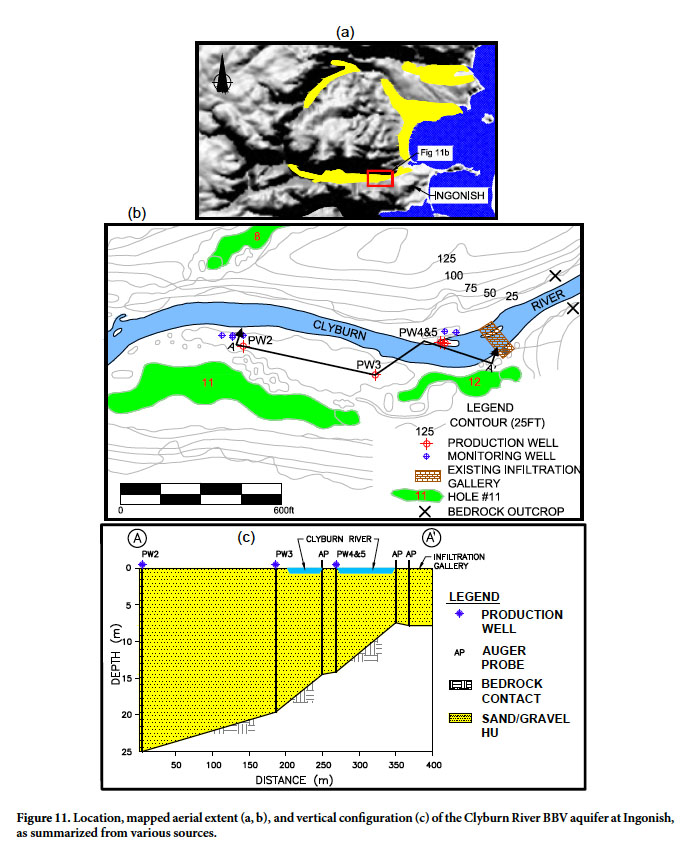

40 The Clyburn River Aquifer (Figs. 3 and 11) exemplifies an unconfined, BBV aquifer within the Canyon Hydrological Region (Fig. 5b). This aquifer is distinctive in that: (1) the valley flanks are steep, rising to a canyon rim some 250 to 430 m above the valley floor; (2) the aquifer is bounded by low permeability crystalline bedrock; (3) the canyon received drainage from the Highland ice cap through to its demise around 10 ka (Grant 1994), providing for longer-duration glacial melt flows and coarser sediment transport, creating a gravel dominated aquifer; (4) the steep valley flanks exhibit coarse, permeable sediments associated with colluvium, talus cones, and alluvial fans, and (5) the low permeable highland headwaters generate peak storm flow events, which enhances channel migration and flooding. The land surface and contributing watershed are protected within the Cape Breton Highlands National Park. A hardwood Acadian Forest dominates the aquifer and valley flanks, transitioning into Boreal softwood and Taiga forests with wetlands and rock barrens over the highland peneplain headwaters. The Highlands Links golf course surrounds the extraction site.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

41 Hydrogeological investigations developed the irrigation supply for the Cape Breton Highlands golf course (CBCL Ltd. 1995a, 1995b, 1996). This was supported by geotechnical investigations for bridge and route alignments associated with the Cabot Trail (ADI Ltd. 2005; SNC Lavelin 2015). The reach of channel underlain by this BBV aquifer provides for salmonid habitat (ADI Nolan Davis Ltd. 1993). Channel training procedures have been implemented to protect pumping facilities and the golf course, as well as to maintain habitat (ADI Nolan Davis Ltd. 1993; Newbury Hydraulics 2011). The resultant data set included four production wells, one infiltration gallery, 24 groundwater monitoring wells and boreholes, 25 geotechnical holes, 41 domestic water supply wells, three pump tests, three grain-size analyses, and three representative water chemical analyses. The irrigation supply for the golf course has been in operation for over 19 years from production wells and for approximately 50 years from an infiltration gallery.

42 The 7 km-long aquifer within the Clyburn River Canyon (Fig. 11a) ranges from 200 to 500 m in width, covering approximately 2.0 km2. It appears to be truncated just downstream of the extraction site by narrowing of the valley to 50 m and a bedrock sill under the present-day channel (Fig. 11 b). The valley widens and the buried channel reappears downstream of the sill. The Type 1 aquifer is locally overlain by Type 3 permeable coarse gravel, cobble, and boulder sequences within colluvium, talus cones and alluvial fans resulting from Holocene erosion, creating influent, ephemeral tributary streams over its surface.

43 Hydrogeological studies for the water supply focused on a 0.4 km reach of channel immediately upstream of the bedrock sill. The depth of the aquifer increased upstream from 5.5 to 7.9 m near the sill to 14 to > 25 m towards the west (Fig. 11c). The deposit is poorly sorted sand and gravel, which locally becomes siltier below 5 m depth. Grain-size analyses indicated a range of gravel (26 to 49%), sand (47 to 68%) and silt (4 to 19%). Geotechnical drilling 0.8 km downstream from the extraction site noted the buried valley was incised into crystalline basement to 25 m and infilled with a sand/gravel aquifer, which became coarser with depth. No till, lacustrine/marine clays or diamictons are present over, under or within the aquifer.

44 Testing of a 7 m-deep infiltration gallery (Figs. 11b and c) exhibited well transmissivity ranging from 1112 to 1236 m2/day and aquifer transmissivity of 902 m2/d; with storativity of 2.0 x 10-1 . A seven-day duration pumping test of PW2 and 3-day duration test of PW5 provided well transmisivities of 952 and 1939 m2/d, respectively. The resultant 20 year safe yields ranged from >582 Lpm for PW 5 to 1284 Lpm for the infiltration gallery and >1287 Lpm for PW2.

45 Groundwater stream interaction is maintained by a high water table. At the groundwater extraction site, the 69.8 km2 watershed has created a perennial, 30 to 35 m wide, 30th Shreve stream order channel with a gradient of 0.3 to 0.5 %. The large width/depth ratio (5 to 10) channel is incised only 1 to 2 m into the aquifer, with no signs of terracing. At a Rosgen Level 1 (Rosgen and Silvey 1998) it is qualitatively classed as a C3 to C4 channel, exhibiting a riffle-run-pool morphology; with localized braided reaches. This has created four salmon pools within 2 km around the extraction site (ADI Nolan Davis Ltd. 1993).

46 The infiltration gallery and production wells provide a fresh (TDS 30–92 mg/L), soft (10.8–14.8 mg/L as CaCO3), generally calcium-bicarbonate type water (Fig. 6). The shallow infiltration gallery exhibited a sodium/calcium bicarbonate-type water. The pH was slightly acidic (6.1–6.9) with an alkalinity of 11–32 mg/L. Metal indicators of iron (<0.01–0.15 mg/L), manganese (<0.01 mg/L), and aluminum (<0.01 to 0.06 mg/L) were at non-detectable to low concentrations.

47 The natural forest cover and numerous wetlands in the headwaters of the Clyburn River Aquifer have resulted in nutrients characterized by non-detectable to low concentrations of nitrogen as nitrite +nitrate (as N) (<0.05 to 0.16 mg/L).

MANAGEMENT ISSUES

48 The need for managing BBV aquifers on Cape Breton Island is strengthened by the variety of ways they are presently utilized. They provide potable groundwater supplies for five municipal and three commercial/industrial ventures, as well as irrigation for four golf courses. They can be critical as surficial aquifers for domestic supplies in areas underlain by evaporite bedrock aquifers with poor water quality. They are critical in supporting salmonids and other fresh water, estuarine and possible near shore, coastal ecosystems. The design, monitoring, and remedial strategies for three waste disposal sites has been influenced by their presence, as has geotechnical designs for 21 bridge structures and dewatering control for four large construction sites on the Island. One BBV aquifer has, for the most part, already been removed to supply construction aggregate. These aquifers do not necessarily follow underfit surface streams and can divert groundwater flow under surface watershed divides. Depending upon the impact of changing climate the large storage capacity and permeability of these aquifers may play a critical future role in developing adaptation strategies for groundwater withdrawals, protecting fresh water aquatic ecosystems, as well as providing emergency response to natural disasters.

49 Low frequency, manual monitoring at two sites on Cape Breton Island indicates no notable changes in head levels or select indicator chemistry over the past 17 years (Glen Brook Aquifer) and 27 years (Broad Cove Aquifer). This suggests that these sites remain unaffected to date by historical land use, acid rain, and changing climate. Impacts from base-metal mineralization, radon gas, and natural oil/gas have not been detected within the three case study aquifers.

50 To support effective management of these BBV aquifers on Cape Breton Island, interdisciplinary research should incorporate six issues:

- The focus of research should be on characterizing hydrogeological conditions within BBV aquifers in areas of enhanced land use, existing large groundwater withdrawals, and/or important aquatic ecosystems. This will aid in managing the aquifer for diverse uses such as water supply, aggregate extraction, and/or supporting river, estuarine, and near-shore coastal ecosystems.

- Understanding the influence of channel-aquifer interactions in supporting benthic invertebrates, salmonids, sediment transport, channel morphology, and hyporheic zones would aid in developing effective groundwater withdrawal permitting.

- There is a need to understand the impacts of changing climate on groundwater levels within the BBV aquifers of Cape Breton Island. Any notable water table declines could have resultant impacts on creating ephemeral reaches within surface channels and may alter the presence and persistence of vernal pools and wetlands, with subsequent impacts on aquatic ecosystems.

- The unconsolidated nature of the aquifer materials which form the surface channel allows for active meandering. This constantly modifies the aquifer, alters riparian forest cover, provides good habitat for salmonids and beavers, and alters the extent of floodplains and vernal pools. A more comprehensive understanding of these issues will aid in positioning groundwater extraction points, developing channel erosion control procedures, identifying groundwater under direct influence (GUDI) situations, and developing well head protection strategies.

- Five of the present municipal water supplies have wells within 0.5 to 2.7 km of brackish to saline waters along the coast, with wells bottomed approximately 5 and 15 m below sea level. A means of monitoring the impact of pumping on the saltwater lens, especially given predicted sea-level rise scenarios, should be developed.

- The provincial groundwater observation well monitoring program should be integrated and enhanced with wells positioned within select BBV aquifers, in proximity to surface water flow gauging stations.

CONCLUSIONS

51 Cape Breton Island provides a hydrogeological view into a tectonically ancient, exhumed, glaciated, now tectonically inactive, deep crustal terrain, with BBV aquifers comprised of Cretaceous, Pleistocene, and Holocene deposits. Buried bedrock valley aquifers were found at 92 (61%) of 150 sites studied on the island. Of these 28% were “proven”, 24% were “probable” and 9% “possible”. Their architecture is varied, including: (1) sand-dominated, localized, narrow, subglacial channels carved into sedimentary bedrock and semi-confined by and interbedded with tills; (2) broad, sand- and/or gravel-dominated alluvial valley deposits covering incised bedrock channels at depth; and (3) ice contact features buried at depth within thick lacustrine clay and till deposits.

52 The BBV aquifers presented in this paper generally exhibit intermediate to very high transmissivities, relatively large safe yields, and potable water chemistry. The water quality in deeper portions of the aquifers is controlled by the underlying bedrock, which in localized areas can be influenced by underlying evaporite rocks. No notable metal mineralization, radon gas, and natural oil/gas has been found to date within the aquifers studied. These characteristics have allowed seven aquifers to provide potable water for eight municipal, industrial, and commercial purposes for between 13 and 50 years.

53 All physical and chemical data on the 150 sites investigated have been provided to the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources for inclusion in their digital water resources data base; to be made public at their discretion.

54 Future research is required to identify and characterize these aquifers in select high priority areas. These include areas experiencing enhanced pumping, altered land use (e.g. suburbanization, agriculture and forestry), and/or aggregate extraction, as well as those with rivers important to aquatic ecosystems. This approach is especially relevant considering potential impacts arising from changing climate and rising sea level.

The discussion provided in this paper evolves from the author’s experience and that of Lynn Baechler on Cape Breton Island over the last 40 years. Numerous discussions over the years with Dr. D. Grant, Dr. John Shaw and Dr. R. Stea proved greatly beneficial in understanding the geological base for this assessment. Appreciation is extended to the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resource’s library staff for their diligent help in locating historical geological data, and use of their water-well data base. Appreciation is also extended to the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation and Infrastructural Renewal for geotechnical reports on bridge structures, as well as Georgia Pacific Canada LP and Parks Canada for their relevant documents. The paper was significantly improved by comments from anonymous reviewers and the editor Dr. Chantel Nixon. The author would like to gratefully acknowledge and thank all those that assisted in this endeavor. Messrs. Neil Bach, Cory Youden and Bill Jones of Exp Services Inc. are greatly acknowledged for aid in drafting the figures and developing the associated GIS data base which facilitated the analysis.