Foliar forms of Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri (Pennsylvanian, Sydney Coalfield, Nova Scotia, Canada)

Ervin L. ZodrowDepartment of Geology, University College of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada B1P 6L2

<erwin_zodrow@uccb.ca>

Date received: February 20, 2003 ¶ Date accepted: May 23, 2003

ABSTRACT

Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri has been extensively figured and called by many different names, particularly in the European literature, since the species was erected in 1699. Much of the nature of this arborescent-medullosalean tree still remains to be documented, i.e., fructification, trunk, root, and frond architecture, but its heterophyllous foliage is well known. Based on the large macrofossil collections from the Pennsylvanian Sydney Coalfield, Nova Scotia, Canada, it is possible to present an overall view of the diverse foliar nature of this remarkable medullosalean tree. Suggestions are offered as to how the many foliar forms fit into the bipinnate frond of Laveine and Brousmiche (1982).RÉSUMÉ

Le Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri a été abondamment décrit et a été appelé de nombreux noms différents, en particulier dans la documentation européenne, car l'espèce a été établie en 1699. Il reste encore à documenter une vaste part de la nature de cet arbre arborescent-médullosaléen, c.-à-d. la fructification, le tronc, les racines et l'architecture des frondes, mais on connaît bien son feuillage héterophylle. Il est possible, en se basant sur les grandes collections de macrofossiles du terrain houiller pennsylvanien de Sydney, Nouvelle-Écosse, Canada, de présenter un aperçu de la nature foliaire diversifiée de ce remarquable arbre médullosaléen. Des hypothèses sont avancées sur la façon dont les nombreuses formes foliaires s'insèrent dans la fronde bipennée de Laveine et Brousmiche (1982).INTRODUCTION

1 Presented are different foliar forms of the concept of the morphospecies Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri Cleal, Shute and Zodrow, 1990, since the species was erected by Luyd (1669) under the name of Phyllites mineralis (see Scheuchzer 1709, 1723, pl. X, p. 48; Laveine 1967; Fischer 1973; Andrews 1980). One hundred years later, after the death of the Swiss naturalist Scheuchzer in 1733, Hoffmann (in Keferstein 1826) renamed P. mineralis as Neuropteris scheuchzeri to honour the Swiss naturalist.

2 Bunbury (1847) was the first to recognize N. scheuchzeri from North America amongst fossil collections shipped to him by Richard Brown Sr. of Sydney Mines, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Bunbury's hand-written records of 1850: Part 1, Ferns and Lycophytes, preserved at Cambridge University, show unequivocally that the fossils originated from the Sydney Coalfield, likely from the Sydney Mines strata that today are considered Westphalian D (Cleal et al. 2003). In retroview, Bunbury's recognition of N. scheuchzeri was not by direct morphological comparison, but by synonymous equivalency: he compared his new variety that he named Neuropteris cordata var. angustifolia (1847) with Brongniart's species Neuropteris angustifolia (1831, p. 231, pl. 64, figs. 3 and 4). Then with considerable insight Bunbury (1847, p. 424) emphatically stated that Brongniart's species of N. angustifolia and N. acutifolia, and Hoffmann's species of N. scheuchzeri were conspecific. This taxonomic claim is still maintained today (Laveine 1967; present paper). Bunbury's new species of Odontopteris subcuneata (1847, p. 427, pl. XXIII, figs. 1A,B) was recognized by Bell (1938) as a synonym of N. scheuchzeri which is confirmed by taxonomic studies by Laveine (1967), Kotasowa (1973), and the present paper.

3 The concept of N. scheuchzeri was taxonomically refined by Cleal and Zodrow (1989) through epidermal work (see also Barthel 1961). Based on that work, Cleal et al. (1990) proposed changing the generic designation of Neuropteris pro parte to Macroneuropteris Cleal, Shute and Zodrow gen. nov. with Macroneuropteris macrophylla (Brongniart) (Cleal et al. 1990) as type species while still regarding the new combination Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri as a morphogenus.

4 M. scheuchzeri was also one of three medullosalean species whose biochemical make-up was probed, the results of which led to hypothesizing that pteridophylls in general can be separated and determined by their spectral characteristics (functional-carbon groups and certain ratios derived therefrom, and hydrocarbon compounds: see Lyons et al. 1995; Zodrow and Mastalerz 2000). In effect, this work introduced chemotaxonomic utility into Carboniferous plant determinations, and it is currently extended to cordaites as well, with encouraging results (Zodrow et al. 2003),

GEOLOGICAL SETTING: SYDNEY COALFIELD

5 The Carboniferous evolution of Nova Scotia was most recently summarized by Calder (1998). Sydney Basin is part of the Maritimes Basin that encompassed nearly all of the Canadian Atlantic Provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and southwestern Newfoundland (Calder 1998, fig. 2). Basin-fill sediments were deposited in distinct intervals that can be regionally correlated. During the Westphalian D and early Cantabrian, basin subsidence diminished and widespread coal-forest peats accumulated on near-costal plains (Ryan et al. 1991; Gibling and Bird 1994; Calder 1998).

6 The ca. 2200 m of the Morien Group (Bell 1938) that comprise Sydney Coalfield (on-shore portion of the Sydney Basin) were recently subdivided into three formations (Boehner and Giles 1986): Sydney Mines, Waddens Cove and South Bar formations (Fig. 1), where the first-named formation contains the mineable coal measures of Sydney Coalfield.

7 The biostratigraphy of the Morien Group was revised by Zodrow and Cleal (1985), and most recently by Cleal et al. (2003). This entailed relocating Bell's (1938) Westphalian D and "C" stage boundaries downwards, and at the same time intercalating the Cantabrian Stage at the Lloyd Cove (Zodrow 1985; see Fig. 1). Carboniferous nomenclature proposed by Menning et al. (1991) is followed in this paper.

Fig 1 Stratigraphy of Sydney Coalfield, Morien Group, Nova Scotia, Canada, and co-ordinated positions of study specimens identified by accession number (e.g., 984-265) of the Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax.SAMPLE DEPOSITORY

8 The 17 figured specimens from the Sydney Mines Formation, represent critical selections to illustrate diverse forms from a total of ca. 300 M. scheuchzeri specimens collected from the entire Morien Group. These are an integral part of the documented ca. 15000 macrofloral specimens retrieved by the author from the Sydney Coalfield since 1973. These collections are housed at the University College of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada, with the author being the curator.

SAMPLE MATERIAL AND METHODS

9 The study material is stratigraphically documented in Fig. 1, bearing accession numbers of the Nova Scotia Museum, e.g., 977(GF)-408. The fossils are preserved by compression in silty-shale and shale rocks, and invariably yielded intact cuticles (Cleal and Zodrow 1989; Lyons et al. 1995). A recent survey (unpublished data, January 2003) demonstrated that 45 specimens, representing the entire Morien Group (Fig. 1), all tested positive for intact cuticles. From a 6-cm long "ultimate pinna" of the "Odontopteris subcuneata" form of M. scheuchzeri, 14 slide-mounted preparations of adaxial and abaxial cuticles (unpublished data, 1991) document the epidermis from different positions along the ultimate rachis.

10 Chemical methods for extracting the cuticles are detailed in Cleal and Zodrow (1989).

HETEROPHYLLOUS NATURE OF M. SCHEUCHZERI

Specific definition

11 M. scheuchzeri (Order Trigonocarpales Meyen, Satellite morphogenus Macroneuropteris) is defined by gross morphology and epidermal characteristics (Cleal et al. 1990). The latter include large, irregularly shaped polygonal cells, 220 µm long and 60 µm wide on the adaxial surface, and somewhat smaller cells on the abaxial surface that also shows brachyparacytic stomata (two subsidiary cells); trichomes bases are present on both surfaces (Cleal and Zodrow 1989, text-fig. 3; Cleal et al. 1990).

12 The frond is bipinnate and has a basal dichotomy (Laveine 1967; Laveine et al. 1977; Laveine and Brousmiche 1982; Laveine et al. 1998). A comprehensive proposal for the reconstruction of the plant M. scheuchzeri is forthcoming (pers. comm. J.-P. Laveine, February, 2003).

Distribution

13 M. scheuchzeri is one of the very few azonal macrofossil plants in the Morien Group, as it ranges from the lowest strata at the Shoemaker Seam (Bolsovian) to the highest strata at the Point Aconi Seam (lower Cantabrian), see Bell (1938, Fig. 1). This is similar to the range in the Cantabrian in NW Spain (Wagner 1983, fig. 4). This contrasts with the distribution of the species in the Late Carboniferous Period of West and Central Europe, where it ranges from the Duckmantian to the top of the Westphalian D as an index for the Stephanian (summary: Josten 1991). In general, the species has a global distribution over palaeoequatorial tropical, Late Carboniferous, coal forests, and spans a time interval conservatively estimated to be at least 15 Ma, or three Westphalian Stages.

Palaeobiology

14 To date, organically attached male and female fructifications of M. scheuchzeri havenot been documented. From Sydney Coalfield, one pteridosperm seed attached to foliage of Neuropteris flexuosa is known (Zodrow and McCandlish 1980) which emphasizes the rarity of attached female organs to determinable foliage. However, Bell (1938) thought that the large, detached seeds of Trigonocarpus (Schizospermum) noeggerati Sternberg could represent ovules of the species. Ovules of this type are ubiquitous and are found throughout the strata of the Sydney Coalfield (see Zodrow 2002, Fig. 16c), and commonly in physical association with M. scheuchzeri foliage. Laveine (1967, fig 1d) suggested that Codonotheca caduca Sellard is the male organ.

Descriptions of foliar forms from Sydney Coalfield

15 In its most typical form in Sydney Coalfield, M. scheuchzeri (Fig. 2a) has large, lanceolate pinnules that reach a length of 12 cm or more and a width of 2.5 to 3.0 cm, rarely 5 cm, with a slightly round or acuminate apex. These measurements are larger than West and Central European measurements of 2 to 9 cm length and 0.6 to 2.5 cm width (summary: Josten 1991, p. 331). The pinnule base is cordate, or stalked, and the margin entire. The midvein is prominent and extends for most of the pinnule length. Venation is dense; lateral veins fork 3 to 5 times, and broadly arch to reach the lateral margin at an oblique angle, 70 to 80 degrees. Over most of the pinnule, abundant epicuticular hair (Fig. 2b) is present that can reach a maximum length of 2 mm. Hair is cross-aligned to the venation pattern, imparting a prominent pseudohexagonal pattern, and presents an important taxonomic feature (e.g., Bunbury 1847, pl. XXI; Laveine 1967; Kotasowa 1973; Cleal and Zodrow 1989;Josten 1991; present paper) for differentiating M. scheuchzeri from all of the other macroneuropterid species (Cleal et al. 1990; Josten 1991).

Fig 2 Typical M. scheuchzerifoliage. a) Upper surface of a broadly-shaped lanceolate pinnule, round apically, with cordate base. 977-408, Lloyd Cove Seam. b) Illustrating copious, epicuticular hair growth on a pinnule; mid section is shown. 997-230; Bouthilier Seam.

Display large image of Figure 2

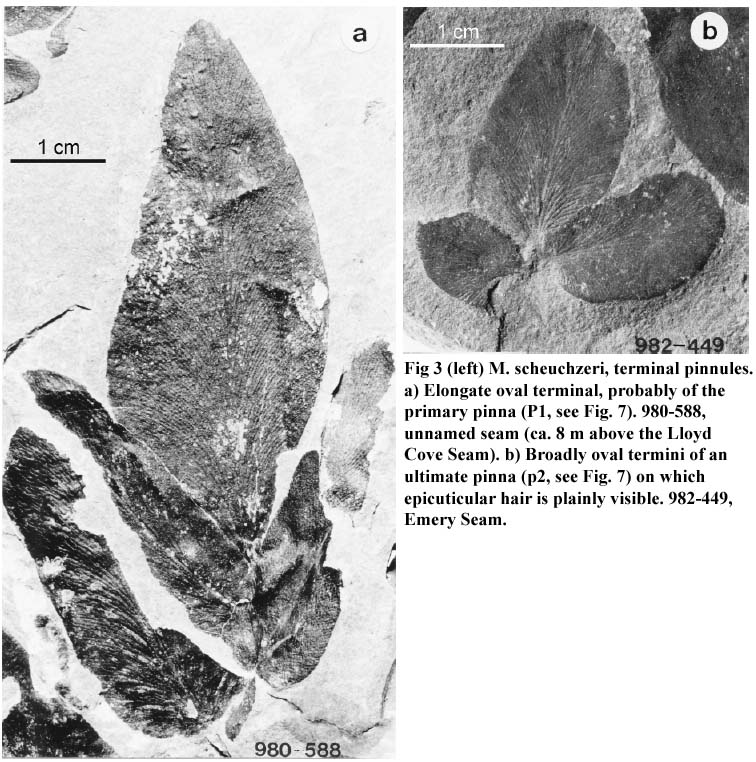

16 M. scheuchzeri bears large terminal pinnules that reach a length of over 6 cm, a width of 2.5 cm, are elongate (Fig. 3a), or broadly oval (Fig. 3b), and are typically profusely covered with long, epicuticular hair.

Fig 3 M. scheuchzeri, terminal pinnules. a) Elongate oval terminal, probably of the primary pinna (P1, see Fig. 7). 980-588, unnamed seam (ca. 8 m above the Lloyd Cove Seam). b) Broadly oval termini of an ultimate pinna (p2, see Fig. 7) on which epicuticular hair is plainly visible. 982-449, Emery Seam.

Display large image of Figure 3

17 Based on the aforementioned gross morphological features, typical M. scheuchzeri is a most-easily recognizable species in the Late Carboniferous, worldwide.

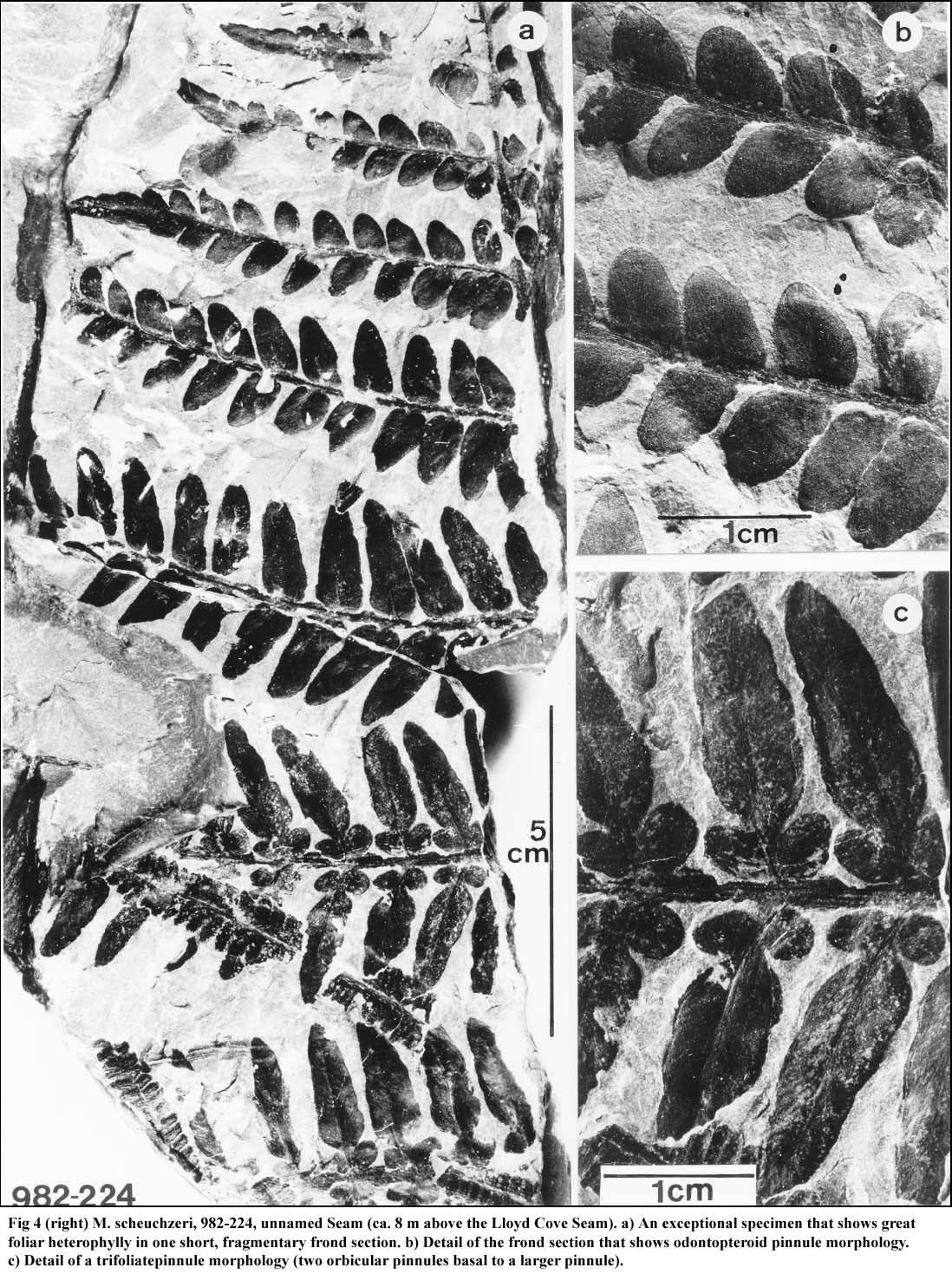

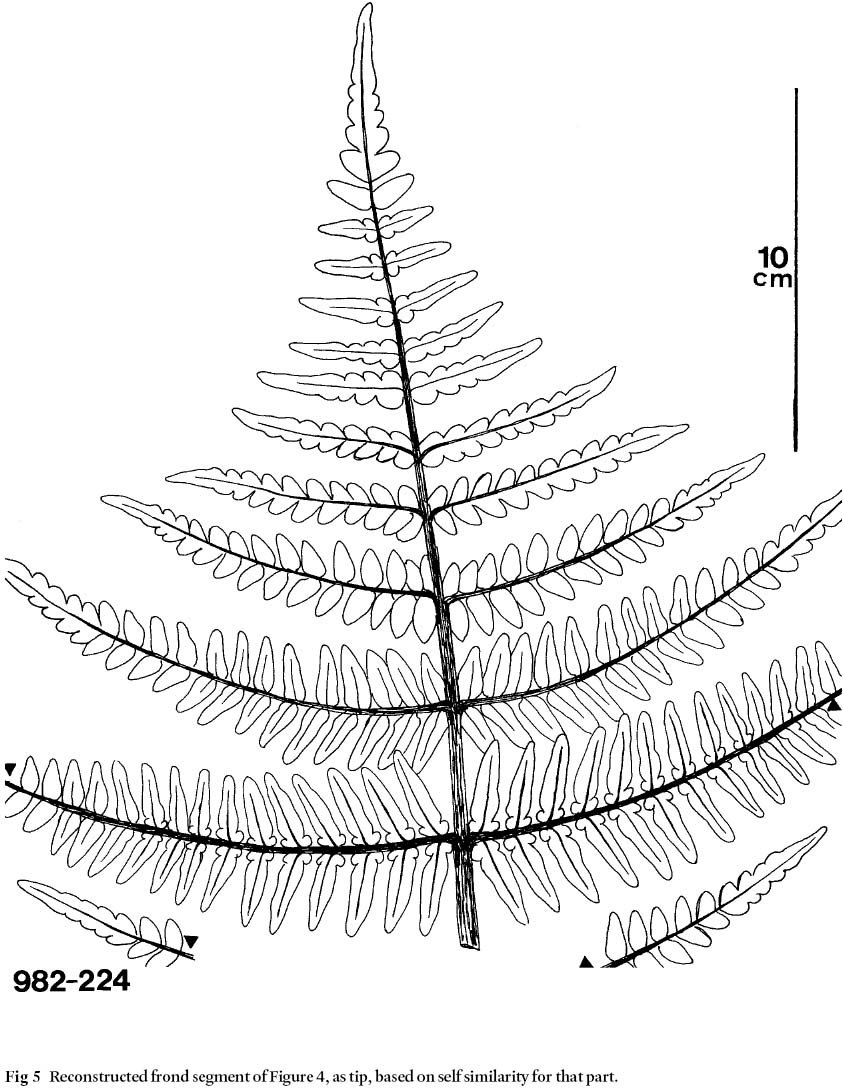

18 Figures 4 and 5 illustrate a specimen of great interest in this discussion because it shows considerable morphological changes over its axial length of 30 cm. Its near-tip section is odontopteroid in form (Fig. 4a, detail 4b). These pinnules are attached to a rachis by their entire base, lateral veins are parallel to each other (no midvein is present), and they originate directly from the rachis. Neuropteroid morphology follows and pinnules have a cordate base, and are stalked-attached to a rachis. This morphology changes to the trifoliate form (Fig. 4c), with some transitional elements. In general, trifoliate pinnules are composed of a main pinnule of various lengths to which are basally attached two symmetrically-placed, smaller, orbicular pinnules, maximally 3 cm in length. Hair is absent in these pinnules, as confirmed in part by cuticular analysis. However, cuticular analysis of material illustrated in Fig. 4 reveals a stomatal structure, distribution of stomata, and shape of epidermal cells that are similar to those of M. scheuchzeri (see Cleal and Zodrow 1989, pl. 106). It is observed that trifoliate pinnules that reach a minimum length of 4 cm grew abundant hair, including on the orbiculars (Fig. 6; see also Bunbury 1847). Unless it can be demonstrated that the morphologies in Fig. 5 are reproducible over the distal parts of the frond, the usual assumption of self similarity (Heggie and Zodrow 1994) is called into question for M. scheuchzeri.

Fig 4 M. scheuchzeri, 982-224, unnamed Seam (ca.8 m above the Lloyd Cove Seam). a) An exceptional specimen that shows great foliar heterophylly in one short, fragmentary frond section. b) Detail of the frond section that shows odontopteroid pinnule morphology. c) Detail of a trifoliatepinnule morphology (two orbicular pinnules basal to a larger pinnule).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

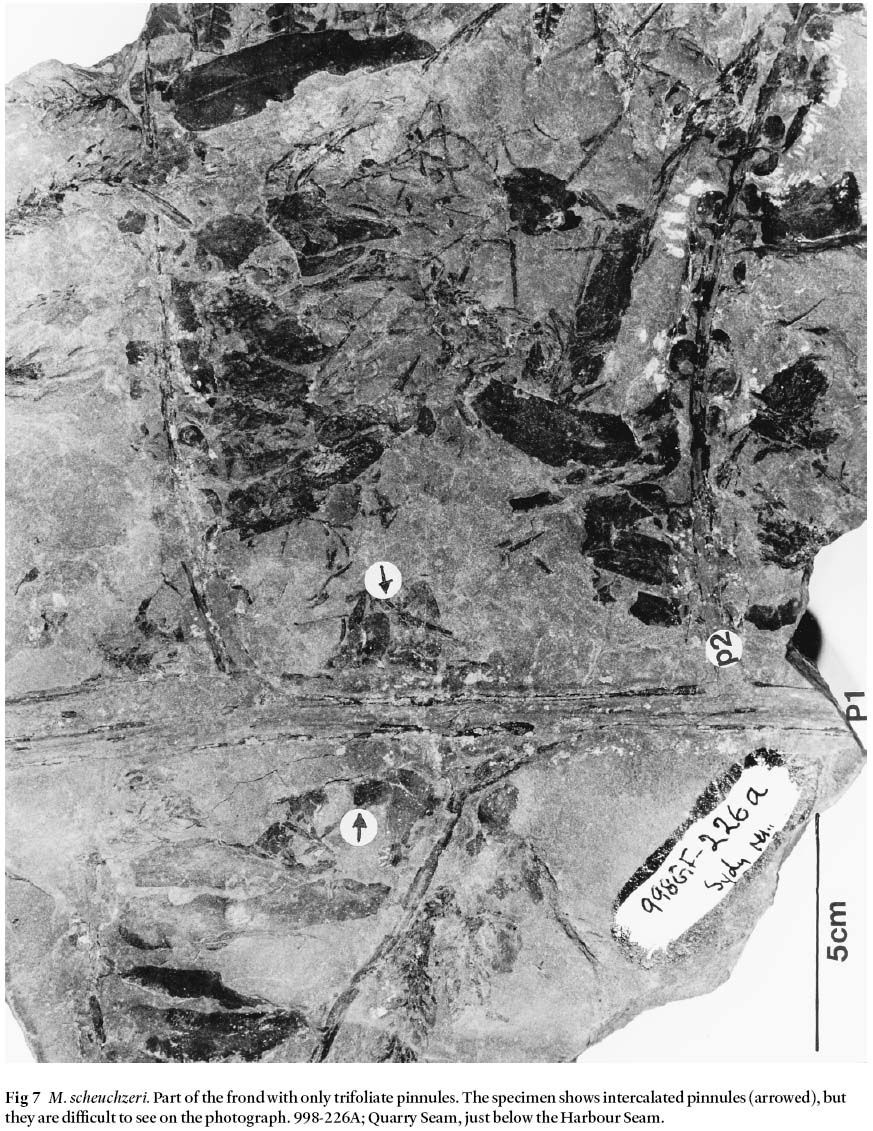

19 The largest specimen of M. scheuchzeri (Fig. 7) from the Canadian Pennsylvanian originated from the historical coal-mining town of Sydney Mines, Sydney Coalfield. The primary rachis is preserved for a length of 22 cm, and is 1 cm wide with longitudinal striations that represent medullosalean sclerenchymatous fibres (imparting strength to the frond structure). The rachis also shows intercalated pinnules, as is typical for M. scheuchzeri (Bertrand 1930, pl. IX). Oppositely-placed ultimate rachides, 0.5 cm wide and striated, are preserved for a length of 17 cm, and are spaced ca. 11 cm apart; terminal pinnules are eroded. The fragmentary frond only bears trifoliate pinnules that are up to 6.5 cm long and 1.5 cm wide, and axially spaced at ca. 2 cm intervals. Abundant hair is present on all of the pinnules and orbiculars. This specimen fits Bunbury's (1847, pl. XXI, figs. 1A and 1B) concept of N. cordata var. angustifolia. The largest M. scheuchzeri specimen known with such morphology is 1 meter long, 50 cm wide, and is figured by Bertrand (1930, pl. IX).

Fig 7 M. scheuchzeri. Part of the frond with only trifoliate pinnules. The specimen shows intercalated pinnules (arrowed), but they are difficult to see on the photograph. 998-226A; Quarry Seam, just below the Harbour Seam.

Display large image of Figure 7

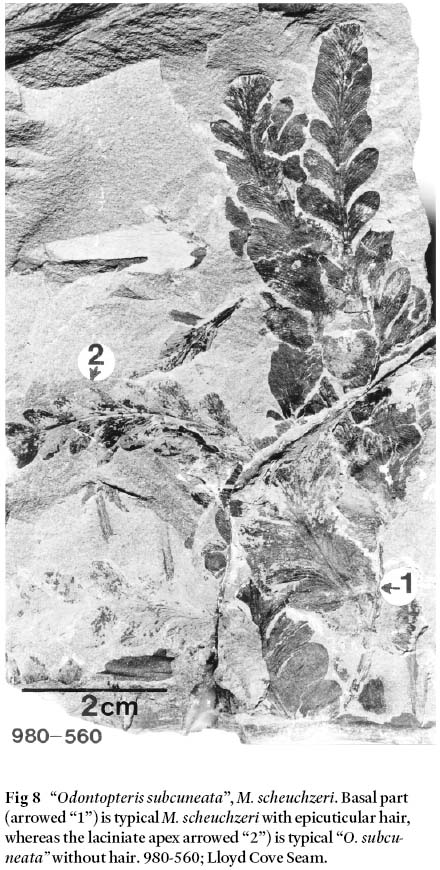

20 Apart from these forms, foliage of the M. scheuchzeri frondis furthermore characterized by laciniate, or deeply cut leaves that additionally show odontopteroid morphology (but it is not true odontopterid!). Bunbury (1847, pl. XXIII, fig. 1A, 1B) figured "Odontopteris subcuneata" from Sydney Mines, but he did not mention the presence of epicuticular hair on the holotype [that Bell in 1938 had recognized as being a synonym of M. scheuchzeri]. However, epidermal features of the 6-cm specimen of Bunbury's laciniate species include irregular, cluster-distributed trichomal bases on adaxial and abaxial surfaces, and on intercostal and costal fields. Epidermal cells are also similar in shape and size to those described by Cleal and Zodrow (1989) for M. scheuchzeri. Fig. 8 is one example of laciniate "O. subcuneata" that at the same time is the contiguous apical part of an otherwise typical M. scheuchzeri complete with epicuticular hair. This direct evidence confirms conspecifity between Bunbury's "O. subcuneata" and Hoffmann's species M. scheuchzeri, a proposition which Bell (1938) assumed all along.

Fig 8 "Odontopteris subcuneata", M. scheuchzeri. Basal part (arrowed "1") is typical M. scheuchzeri with epicuticular hair, whereas the laciniate apex arrowed "2") is typical "O. subcuneata" without hair. 980-560; Lloyd Cove Seam.

Display large image of Figure 8

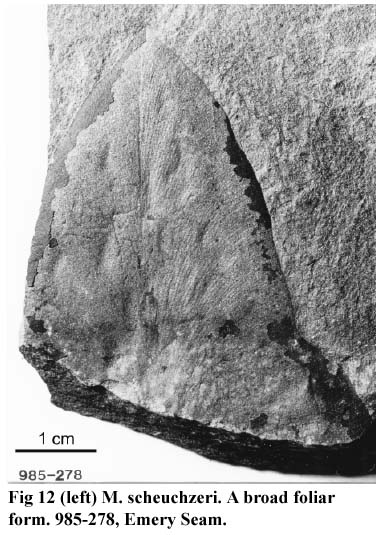

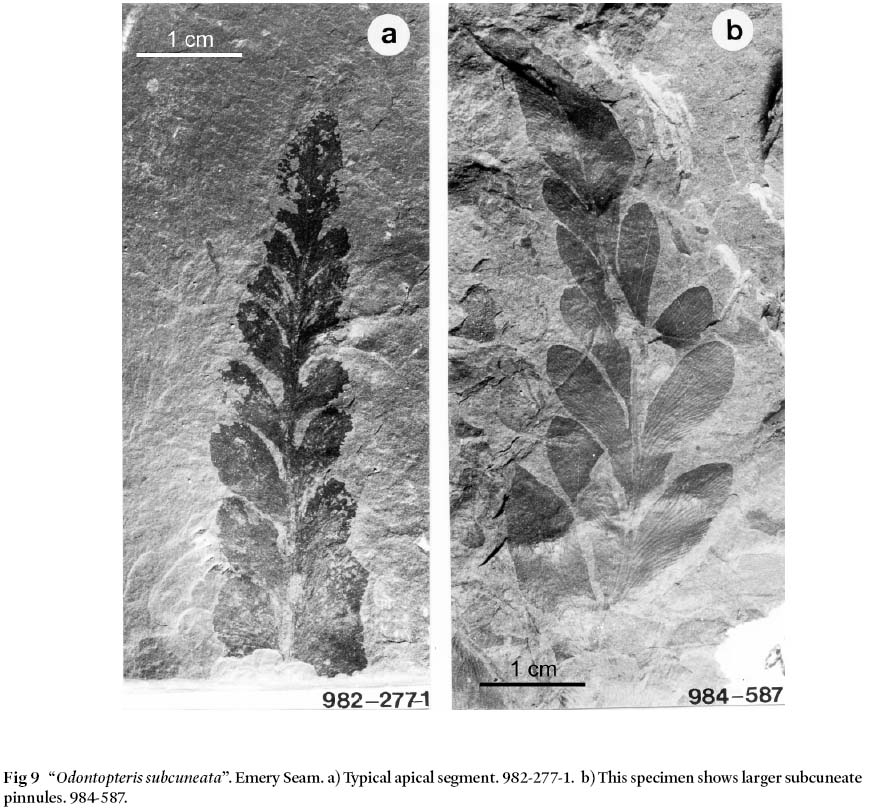

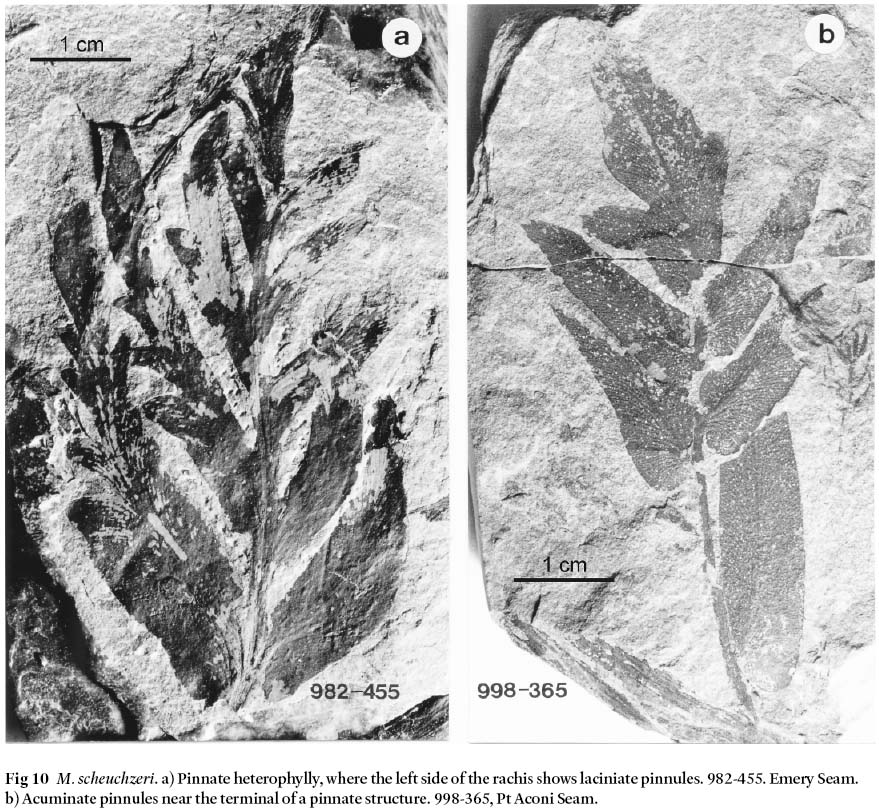

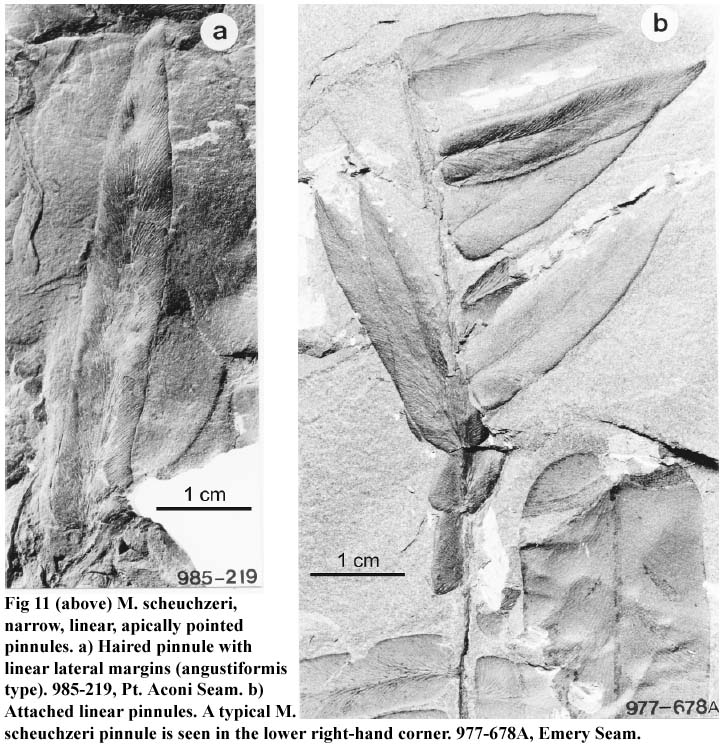

21 Detached "O. subcuneata" forms are shown in Fig. 9a, b. A deeply cut laciniate form, different from Bunbury's "O. subcuneata", is shown in Fig. 10a, whereas Fig. 10b compares with pl. XII of Bertrand (1930). Fig. 11a illustrates yet another atypical foliar form, haired, by its comparatively narrow, long and linear pinnule, without basal orbicular pinnules, and with a conspicuous acuminate tip. Smaller foliar versions of this form are shown in Figure 11b. This form is figured as Neuropteris angustifolia by Brongniart (1831, pl. 64, figs. 3 and 4), or as N. cordata var. angustifolia by Bunbury (1847). Fig. 12 documents a rather broad and short pinnule (compare with typical M. scheuchzeri, Fig. 2a). Transitional forms between being laciniate and typical pinnules are documented in Fig. 13 a,b; the lower parts of these leaflets are haired, whereas the apical parts are not.

Fig 9 "Odontopteris subcuneata". Emery Seam. a) Typical apical segment. 982-277-1. b) This specimen shows larger subcuneate pinnules. 984-587.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Palaeoecological aspects

22 M. scheuchzeri has all of the characteristics of a water-retaining, drought-adapted, arborescent pteridospermous plant which includes having a very thick cuticle, densely distributed trichomes and sunken stomata (observed on the cuticle; Cleal and Zodrow 1989), and epicuticular hair. Its larger leaf size presumably dissipated heat at a slower rate (summary: Wing and DiMichele 1992).

Foliar forms in the frond structure of M. scheuchzeri

23 The rachial architecture of the M. scheuchzeri frond is demonstrably bipinnate (Laveine and Brousmiche 1982), with intercalated pinnate structures (Bertrand 1930; this paper). The frond furthermore possesses the basal dichotomy of the neuropteroid-frond structure, and an apical bifurcation (Laveine and Brousmiche 1982, pl. 1, fig. 3; Laveine et al. 1998). Laveine (1967, 1989, p. 44) interpreted the frond as being retarded structurally, i.e., the typical or trifoliate pinnule is actually homologous to an imparipterid ultimate pinna that normally is composed of a number of lateral pinnules with one definite terminal pinnule.

24 Bertrand's largest specimen (1930, pl. IX) shows remarkable invariant-pinnule morphology in the proximal part of the one-meter long primary rachis. By contrast, Figs. 4 and 5 show remarkable variability in proximal-pinnule morphology in a 30-cm long specimen to suggest that it originated from the distal part of the bipinnate frond where morphology changes very rapidly. It is material schematized in Fig. 5 that would fit into a position above an apical bifurcation of a neuropteroid frond (see also Zodrow and Cleal 1988) which does not bear intercalated pinnate structures and whose terminal pinnules are comparatively smaller (compare Fig. 3a). Figure 7 would fit into the more central part of the bipinnate frond.

25 What is still poorly understood is the position of the many illustrated laciniate pinnule forms within the frond structure of M. scheuchzeri. In the first instance, Sydney Coalfield is characterized by an abundance of atypical, laciniate forms, originating particularly from the stratigraphical level of the Emery Seam (Fig.1), mid-Westphalian D. At an equivalent stratigraphical horizon in the Saarland, Germany (Cleal and Zodrow 1989; Josten 1991), these forms are absent, nor do they occur to such a level of abundance in the French Late Carboniferous (Laveine 1967; 1989). Either the significance of the differences has never been properly understood, or it could simply be sample bias! Laveine (1967) explained that these laciniate pinnule forms were attached near the base of the frond, below the frond dichotomy (such attachments are normal for medullosalean fronds). However, if such is the case, the evidence presented in this paper points to highly variable forms occupying the segment below the main dichotomy of the frond. An alternative explanation would be that some of these forms are actually intercalated on a primary pinna rachis.

CONCLUSION

26 Macroneuropteris scheuchzeri, taken as a whole-plant species of a pteridospermous tree, is a remarkable species from several perspectives:

- the frond is bipinnate which differs from all other dichotomizing medullosalean fronds that are, by contrast, tripinnate

- foliar diversity is considerable, as recognized already by Bunbury when in 1847 he stated that the N. scheuchzeri plant well deserves to be called heterophylla. Subsequently, about 25 synonyms (see Laveine 1967) underpin Bunbury's insight

- hair grew on laciniate forms such as "Odontopteris subcuneata", although much more sparingly than on typical leaves, i.e., it's a developmental feature

- hair that is so abundantly present on the compressions of typical M. scheuchzeri is commonly obliterated by the maceration process, leaving bases as evidence

- apparently the usual assumption of self similarity is called into question for M. scheuchzeri which would be a remarkable exception

- only Macroneuropteris macrophylla (Brongniart) approaches the size of M. scheuchzeri thatundoubtedly has one of the largest "pinnule" structure of arborescent medullosalean plants of the Late Carboniferous Period

- future collections will be required to identify the as yet unknown reproductive organs, trunk and root structures of M. scheuchzeri, and

- M. scheuchzeri has a disparate vertical distribution in the Canadian Pennsylvanian, compared with the Spanish and Central and West European Late Carboniferous Period.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges Prof. Emeritus J.-P. Laveine for constructive advice to improve the technical content of the manuscript. The journal referees, Drs. H. Falcon-Lang and R. F. Miller, are cordially thanked for suggestions to improve both content and style. Funds for the study came from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.REFERENCES

Andrews, H.N. 1980. The fossil hunters. In search of ancient plants. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y., 421 p.

Barthel, M. 1961. Der Epidermisbau einiger oberkarbonischer Pteridospermen. Geologie, 10, pp. 828– 849.

Bell, W.A. 1938. Fossil flora of Sydney Coal Field, Nova Scotia. Geological Survey of Canada, Memoir 215, 334 p.

Bertrand, P. 1930. Neuroptéridées. Flore Fossile. Études des Gîtes Minéraux de la France. Bassin houiller de la Sarre et de la Lorraine. L. Danel, Lille, 58 p. plus pls. I– XXX.

Boehner, R.C., & Giles, P.S. 1986. Geological map of Sydney Basin, Nova Scotia Department of Mines and Energy, Map 86-1, scale 1:50,000.

Brongniart, A. 1831. Histoire des végétaux fossiles. Vol. 1, livraison 6: 249-294, pls. 59-60, 63, 69, 72, 74-75, 77, 78– 82. Réimpression A. Asher & Co. Amsterdam, 1965.

Bunbury, C.J.F. 1847. On fossil plants from the Coal Formation on Cape Breton. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, London, 3, pp. 423– 438.

Calder, J.H. 1998. The Carboniferous evolution of Nova Scotia. In Lyell: the Past is the Key to the Present. Edited by D.J. Blundell and A.C. Scott. Geological Society, London, Special Publication, 143, pp. 261– 302.

Cleal, C.J., & Zodrow, E.L. 1989. Epidermal structure of some medullosan Neuropteris foliage from the Middle and Upper Carboniferous of Canada and Germany. Palaeontology, 32, pp. 837– 882.

Cleal, C.J., Shute, C.H., & Zodrow, E.L. 1990. A revised taxonomy for Palaeozoic neuropterid foliage. Taxon, 39, pp. 486– 492.

Cleal, C.J., Dimitrova, T.K.H., & Zodrow, E.L., 2003. Macrofloral and palynological criteria for recognising the Westphalia-Stephanian Boundary. Newsletter on Stratigraphy, 39, pp. 181– 208.

Fischer, H. 1973. Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, Naturforscher und Arzt. Neujahrsblatt d. Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, Zürich, 168 p.

Gibling, M.R., & Bird, D.J. 1994. Late Carboniferous cyclothems and alluvial palaeovalleys in the Sydney Basin, Nova Scotia. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 106, pp. 105– 117.

Heggie, M., & Zodrow, E.L. 1994. Fractal lobatopterid frond (Upper Carboniferous marattialean tree fern). Palaeontographica Abteilung B, Festband Schweitzer, 2. Teil. 232, pp. 35– 57.

Josten, K.-H. 1991. Die Steinkohlen-Floren Nordwestdeutsch-lands. Band 36, Geologische Landesamt Nordrhein-West-falen, Krefeld, 434 p. plus Atlas.

Keferstein, C. 1826. Teutschland geognostisch dargestellt. Band 4. Über die Pflanzenreste des Kohlengebirges von Ibbenbühren und von Piesberg bei Osnabrück, Weimer, 11 p.

Kotasowa, A. 1973. Przyczynek do znajomosci gatunka Neuropteris scheuchzeri Hoffmann. Kwartalnik Geolgiczny, 17, pp. 423– 429. In Polish, English summary.

Laveine, J.-P. 1967. Les Neuroptéridées du Nord de la France. Études Géologiques pour l' Atlas de Topographie Souterraine. Service Géologique des Houillères du Bassin du Nord et du Pas-de-Calais, 1(5):1– 344, plus Atlas I to LXXXIV pls.

Laveine, J.-P. 1989. Guide paléobotanique dans le terrain houiller Sarro-Lorrain. Houillères Du Bassin De Lorraine, texte pp. 154, pls. 1– 64.

Laveine, J.-P., & Brousmiche, C. 1982. Documents pour servir à la reconstitution de la fronde chez certaines Neuroptéridées. Géobios, 15, pp. 243– 247

Laveine, J.-P., Coquel, R., & Loboziak, S. 1977. Phylogénie générale des Calliptéridiacées (Pteridospermopsida). Géobios, 10, pp. 757– 847.

Laveine, J.-P., Legrand, L., & Duquesne, H. 1998. Morphological analysis of the "bifurcate semi-pinnate" frond architecture of the Carboniferous pteridosperm Laveineopteris rarinervis, with the support of some recently discovered specimens. Revue Paléobiologie, Genève: 17, pp. 381– 443.

Luyd, E. 1699. Lithophylacii Britannici Ichonographica. London, 144 p., plus pls. I– XVII.

Lyons, P.C., Orem, W., Mastalerz, M., Zodrow, E.L., Vieth-Redemann, A., & Bustin, M. 1995. 13CNMR, micro-FTIR and fluorescence spectra, and pyrolysis-gas chromatograms of coalified foliage of late Carboniferous medullosan seed ferns, Nova Scotia, Canada: implications for coalification and chemotaxonomy. International Journal of Coal Geology, 27, pp. 227– 248.

Menning, M., Belka, Z., Chuvashov, B., Engel, B.A., Jones, P.J., Kullmann, J., Utting, J., Watney, L., & Weyer, D. 2001. The optimal number of Carboniferous series and stages. Newsletter on Stratigraphy, 38, pp. 201– 207.

Ryan, R.L., Boehner, R.C., & Calder, J.H. 1991. Lithostrati-graphic revision of the Upper Carboniferous to Lower Permian strata in the Cumberland Basin, Nova Scotia, and the regional implications for the Maritimes Basin in Atlantic Canada. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 39, pp. 289– 314.

Scheuchzer, J.J. 1709. Herbari Diluviani. pp. 1– 44, pls. I– X.

Scheuchzer, J. J. 1723. Herbari Diluviani. Editio novissima. Petri Vander, Lugduni Batavorum, Utrecht, 14 pls. 119 p.

Wagner, R.H. 1983. Late Westphalian D and early Cantabrian floras of the Guardo Coalfield. In Geology and Palaeontology of the Guardo Coalfield (NE Leon – NW Palencia), Cantabrian MTS. Edited by R.H. Wagner, L.G. Fernández García, & R.M.C. Eagar Instituto Geologica y Minero de España, Madrid, pp. 57– 93, plus 48 pls.

Wing. S.L., & DiMichele, W. A., rapporteurs. 1992. In collaboration with Mazer, S.J., Phillips, T.L., Spaulding, W.G., Taggart, R.E., & Tiffeney, B.H. Ecological characteristics of fossil plants. In Terrestrial Ecosystems through Time. Edited by A.K. Behrensmeyer, J.D. Damuth, W.A. DiMichele, R. Potts, H.-D. Sues, & S.L. Wing University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 139– 180, plus appendix.

Zodrow, E.L. 1985. Odontopteris Brongniart in the upper Carboniferous of Canada. Palaeontographica Abteilung B, 196, pp. 79– 110.

Zodrow, E.L. 2002. The "medullosalean forest" at the Lloyd Cove Seam (Pennsylvanian, Sydney Coalfield, Nova Scotia). Atlantic Geology, 38, pp. 177– 195.

Zodrow, E.L., & Cleal, C.J. 1985. Phyto- and chronostrati-graphical correlations between the late Pennsylvanian Morien Group (Sydney, Nova Scotia) and the Silesian Pennant Measures (south Wales). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 22, pp. 1465– 1473.

Zodrow, E.L., & Cleal, C.J. 1988. The structure of the Carboniferous pteridosperm frond Neuropteris ovata Hoff-mann. Palaeontographica, Abteilung B. 208, pp. 105– 124.

Zodrow, E.L., & Mastalerz, M. 2000. Is cuticular functional carbon biochemistry genetically dependent in Carboniferous pteridophyllous foliage? Newsletter on Carboniferous Stratigraphy, International Union of Geological Sciences, 18, pp. 33– 35.

Zodrow, E.L., & McCandlish, K. 1980. On a Trigonocarpus species attached to Neuropteris (Mixoneura) flexuosa from Sydney Coalfield, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 30, pp. 57– 66.

Zodrow, E.L., Mastalerz, M., & Šmunek, Z. 2003. FTIR-derived characteristics of fossil gymnosperm leaf remains of Cordaites principalis and C. borassifolius (Pennsylvanian, Maritimes Canada and Czech Republic). International Journal of Coal Geology, 55, pp.95– 102.

Editorial responsibility: Ron K. Pickerill