Women in Theatre:

Here, There, Everywhere, and Nowhere

Rebecca BurtonUniversity of Toronto

Reina Green

Mount Saint Vincent University

Abstract

This article examines the status of women in theatre in the early twenty-first century and determines that while there has been some improvement in Canada in the last twenty-five years, women still lag behind men in terms of employment in key creative positions Studies show that only 30-35% of the nation’s artistic directors are female and that this limits the production of work by female playwrights and the hiring of female directors. Problems are further exacerbated where there is limited provincial and corporate funding, as in Atlantic Canada. Little money, combined with a greater likelihood that work by female playwrights will be defined as risky and less attractive for sponsors and mainstream theatres, further restricts opportunities for women in theatre. Women also identify traditional hierarchical practices in the theatre industry and social policies, which fail to provide parental leave for self-employed workers or adequate publicly-funded daycare, as barriers to their participation. While increased government funding would help all theatre professionals, including women, and women can support one another through networking and mentorship, the theatre community must actively identify and change the practices that lead to gender inequity.Resume

Le présent article porte sur le statut des femmes en théâtre au début du XXIe siècle. Burton et Green constatent que s’il y a eu une certaine amélioration au Canada au cours des vingt-cinq dernières années, les femmes qui œuvrent dans ce secteur accusent encore un retard par rapport aux hommes en termes d'emplois dans des positions-clés en création. En effet, des études démontrent que la direction artistique des compagnies canadiennes n’est confiée à une femme que dans 30 à 35 % des cas, ce qui limite la production d’œuvres signées par des dramaturges de sexe féminin et l’embauche de metteures en scène. L’inégalité est d’autant plus exacerbée là où les subventions accordées par l’administration provinciale et issues du secteur privé sont limitées, comme c’est le cas au Canada atlantique par exemple. Le peu de financement, de paire avec l’impression qu’une œuvre signée par une dramaturge constitue un plus grand risque et donc un moins grand attrait pour les subventionnaires et les théâtres populaires, sont des obstacles supplémentaires que doit surmonter la femme en théâtre. On cite également à titre d’obstacles les pratiques traditionnelles hiérarchisantes à l’œuvre au sein du secteur et les politiques sociales qui ne prévoient pas de congé parental pour les travailleurs autonomes ou un service de garderie subventionné adéquatement par l’État. Tous les professionnels du théâtre, tant masculins que féminins, bénéficieraient d’un plus grand financement public; quant aux femmes en théâtre, elles peuvent s’appuyer entre elles par l’entremise du réseautage et du mentorat. Ceci dit, la communauté théâtrale doit cerner et modifier activement les pratiques qui mènent à l’inégalité des sexes.1 The beginning of the twenty-first century has heralded a reassessment of a number of social issues and artistic endeavors, as witnessed, for example, by the anti-poverty and Africa-awareness campaigns initiated by various musical artists in recent years.1 These campaigns often raise public awareness of social conditions that have shown little improvement in the last quarter century. In theatre, there has also been a growing awareness of limited change in the last few decades, especially regarding the status of women.2 While women in Canadian university theatre programs dramatically (no pun intended) outnumber men, they are much less visible in the country’s professional theatres. Indeed, as this article will show, women currently outnumber men in all aspects of theatre except employment in key creative positions. Given that this inequality exists in a country that has had a charter of rights barring gender discrimination for more than twenty years, and in an era of affirmative action programs, it prompts the question of why this gender gap still exists.What challenges face women in Canadian theatre and prevent their full participation in all aspects of the industry? And what can be done to address this inequity? What follows is a consideration of some of these challenges, with particular reference to the experience of women working in theatre in Atlantic Canada in order to highlight the challenges shared by women across the country and to identify those specific to working in some of the more rural, less central provinces.

The Status of Women in Canadian Theatre: Then

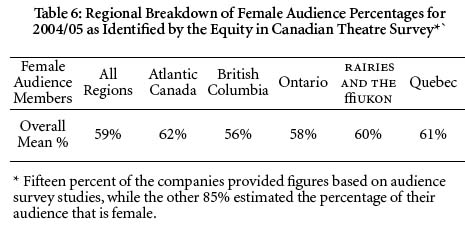

2 Despite the increased visibility of women in the dominant culture and the federal government’s official commitment to gender equity during the late 1970s and early 1980s, women in Canadian theatre often felt discriminated against, marginalized, and outright excluded. Their impressions were based solely on observation and personal experience, so they were easily dismissed as unfounded allegations; that is, until the Status of Women Canada office contracted Rina Fraticelli to assess the situation of women in Canadian theatre for the Applebaum-Hébert Review.3 Released in 1982, Fraticelli’s report, "The Status of Women in the Canadian Theatre," focused specifically on playwrights, directors, and artistic directors, the "triangle" by which "dramatic culture is determined for Canadian audiences–especially in the mainstream" ("Status" vi). Surveying 1,156 productions staged in Canada between the years 1978 and 1981, Fraticelli discovered that women accounted for a paltry 11% of the country’s artistic directors, a mere 13% of its directors, and only 10% of its produced playwrights, as illustrated in Table 1 below (5). The report also revealed that between the years 1972 and 1980, women were awarded one third of the Canada Council’s Theatre Section grants and only 30% of the total funds disbursed (1).Statistics such as these made it painfully clear that the reality for women in Canadian theatre had "fallen far short of the rhetoric" and, all popular perceptions aside, in no way had equality been achieved in the industry (v).

3 Fraticelli’s findings were startling,and ironic perhaps,given that "women form[ed] the vast majority of theatre school graduates as well as the vast majority of amateur (unpaid), volunteer and community theatre workers" (Fraticelli, "Any Black" 9), not to mention the majority of theatre-going audiences (Fraticelli,"Status" 8).As Fraticelli stated in her report:"On the basis of such evidence,[. . .] if [women’s] participation in the profession were to directly reflect their participation as its students, volunteers, consumers and handmaidens, we should expect women to comprise not 51%, but between 2/3 and three-quarters of the theatre employment figures" (9-10). Obviously this was not the case, and as Fraticelli further commented, "where there is low status and little or no money, women are present in great numbers. Elsewhere we are, statistically, nearly invisible" ("Any Black" 9). Fraticelli’s report demonstrated that the alarmingly low numbers were not the result of women avoiding theatre professions, rather they indicated "the small number of women theatre artists who were employed by, and whose work was visible in, the professional [. . .] Canadian theatres" ("Status" 5). Fraticelli coined this phenomenon the "Invisibility Factor"; that is "the absence of women from significant roles in the work of producing a national culture," a tendency particularly prevalent at the larger mainstream theatrical institutions (47).

4 According to Fraticelli’s report,"the worst offenders in terms of the employment of women"were"The Group of 18"(27), a category established on financial grounds to separate out Canada’s most prestigious theatres, specifically those receiving more than $150,000 in government subsidy from the Canada Council (42). Fraticelli’s investigation found that in these theatres, for the years 1978-81, only 7% of the plays produced were written by women and only 9% were directed by women. In the same period, only two of these theatres had artistic directors who were women (27). In contrast, at the other end of the prestige and government subsidy spectrum, children’s theatre and/or theatre for young audiences had a significant number of female artistic directors (29), twice the number of women employed in theatre in general, and three times the number of women found in The Group of 18 theatres (28). In the Maritime Provinces (Nova Scotia,New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island), the picture of women’s employment was even more depressing than the national scenario. Theatre New Brunswick did not employ a single woman as playwright, director, or artistic director, and there were no female artistic directors in Nova Scotia during the three-year period under study (Fraticelli,"Status"Table 13). In the twenty-two years between its inception in 1963 and 1985, Neptune Theatre, Nova Scotia’s regional theatre, produced only two plays directed by women, and only nine plays written by women, and of those, three were co-written with men (Cowan 100). At the time, professional theatre in Prince Edward Island was limited to the Charlottetown Festival, famous for its summer productions of Anne of Green Gables, but it predominantly featured the work of male practitioners. In comparison to the other Atlantic Provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador offered the nation’s most hopeful picture for gender equity, as the region garnered the highest percentage of female artistic directors at 33% (Fraticelli, "Status" Table 13), the greatest number of female directors at 30% (Table 15), and the second highest rate of productions by female playwrights at 13% (Ontario ranked first at 16%) (Table 14).

Table 1: Fraticelli’s National Survey of 1,156 Productions staged by 104 Canadian Theatres between 1978 and 1981

Display large image of Table 1

5 Fraticelli’s study was an important, first-of-its-kind undertaking that provided a number of recommendations, though the report itself was marginalized, falling on deaf ears in both the theatre community and the mainstream, and remaining unpublished to this day (Lushington 9-10). The Applebaum-Hébert Report contained only three references to the plight of women in Canadian culture: it recognized their inadequate representation; it acknowledged that the current situation deprived Canadians "of a vital dimension and artistic experience"; and it noted that poverty was a critical issue for female artists ("Applebert"). Lip service aside, no concrete government assistance or mandated equity resulted from either the Applebaum-Hébert Review or the Canada Council. Despite the ineffectualness of Fraticelli’s report in the mainstream, it was, nonetheless, an extremely important document for women in Canadian theatre. Not only did the report validate their experiences, but it also galvanized the community and led to a number of initiatives. Additional studies were conducted, theatre companies were formed, dramaturgical support groups were established (to challenge the notion that women were not writing "good" plays), service organizations were founded, and women’s conferences and festivals sprang into being.4 This kind of pro-active organizing brought a range of artists together, creating strategies for a strong women’s arts community, effecting change, and providing a tangible female presence in the cultural landscape. Aside from this legacy, Fraticelli’s report is important today because it provides a benchmark for measuring subsequent developments in the status of women in Canadian theatre.

The Status of Women in Theatre: Now

6 In recent years there has been increasing suspicion that women have made little concrete progress since the 1980s, and this perception resulted in calls to re-open Fraticelli’s report. To this end, Equity in Canadian Theatre: The Women’s Initiative was formed with the two-fold mandate of assessing the current status of women in Canadian theatre and developing social action plans to redress any remaining barriers in the industry.5 To collect the necessary information and generate current statistical data, a survey was devised that focused on employment and production practices for the years 2000/01 to 2004/05 which was sent to theatre companies across Canada in the summer of 2005.6 The results of the survey demonstrate that incremental improvement has been made since the release of Fraticelli’s report, with an equivalent increase of 10% per decade in the numbers of women represented, but this advancement is not sufficient to constitute genuine equality in the theatre sector.

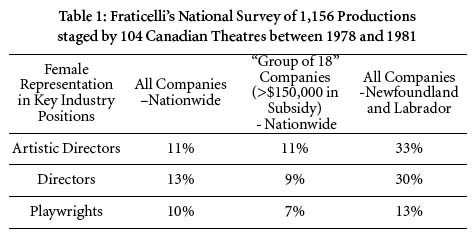

7 The Equity Survey found that in 2004/05, 42% of the surveyed companies had female artistic directors (ADs) and 58% had male ADs (Burton 11). These statistics are skewed in relation to the larger population, however, due to the comparatively higher survey return rate of companies run by female (as opposed to male) ADs. In reality, women constitute 30-35% of the nation’s ADs, as evidenced by informal surveys and provincial studies.7 A cursory look at theatre companies in the Maritime Provinces presents a comparable picture. Of the twenty-nine ADs identified for the 2004/05 season, ten (34%) were women, a number in keeping with the figures found in other provinces.8 Newfoundland and Labrador, however, stand in contrast as the"vast majority"of artistic directors in that province are women (Lynde). Still, as Fraticelli noted years earlier, women are less likely to obtain an artistic leadership role in the larger theatres, regardless of location (Bradley 3). Naomi Campbell and Yvette Nolan found that for the 2003/04 season only six (21%) of twenty-eight"sizable theatres"had female ADs; and only one of those was situated in the Atlantic region.9 Campbell repeated the study the following year, examining the 2004/05 season of twenty-six highly resourced theatres, and discovered that five (19%) of the theatres had female ADs, none of which were located in Atlantic Canada.10 While women have not fared well at the larger mainstream institutions, the increase of approximately 20% in the total percentage of female ADs since Fraticelli’s report is cause for celebration. Nonetheless, the current reality is that women and men are not yet represented in equal numbers as artistic directors. Since artistic directorship is probably the single most influential position in the industry, given the authority exercised over playwright and production decisions as well as hiring practices (see Table 2 above), the relatively low rate of female participation is significant.11

Table 2: Playwright, Director, and Staff Hiring Decisions, 2004/05 as Identified by the Equity in Canadian Theatre Survey

Display large image of Table 2

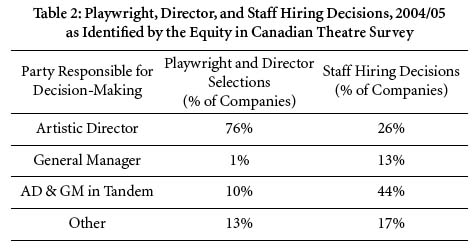

8 The influence of the gender imbalance in artistic directorship is immediately apparent when one examines the number of productions by female playwrights. As reported in the Equity Survey, for the years 2000/01 to 2004/05, 113 companies staged a total of 1,945 productions: 27% of these were written by women, 68% by men and 4% were devised by collectives of men and women (see Table 3 below) (Burton 14).12 While the number of female playwrights having their work produced improved from 10% in 1982 to 28% in 2006, the figure still falls short of equal representation. Moreover, as Table 3 illustrates, the percentage of female playwrights (35% overall) produced by companies with female ADs is 12% higher than at companies with male ADs,where only 23% of the plays are written by women. Given that the majority of Canada’s ADs are male, and that they program work by male playwrights on average 76% of the time (see Table 5), it is not diffi-cult to understand why female playwrights experience difficulties accessing the nation’s stages.An examination of theatre companies in the Maritimes reveals a similar gender imbalance in the realm of playwriting. Of 128 productions presented in 2004/05 (including those in the various theatre festivals), 100 (70%) were written by male playwrights, 29 (23%) by female playwrights, and 10 (8%) by collectives. Looking at the offerings of the three regional theatres, the percentages for female playwrights drop dramatically, with only two productions by female playwrights, neither of whom was Canadian. In other words, Canadian female playwrights were completely shut out of the largest theatres in the Maritimes in 2004/05. The picture was slightly better in these theatres for the 2005/06 season with four plays written by women, three of them Canadian. Despite this improvement, however, an assessment of women’s involvement in Maritime theatre suggests that, as playwrights, they are represented in numbers slightly below the national average.

Table 3: Production and Playwright Percentages for 2000/01–2004/05 as Identified by the Equity in Canadian Theatre Survey*

Display large image of Table 3

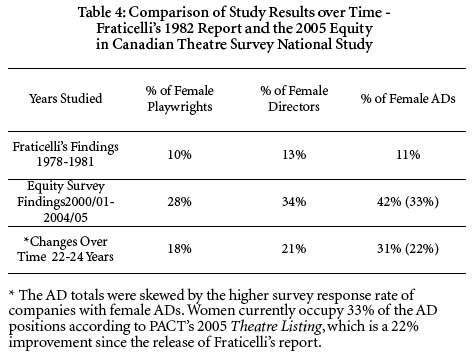

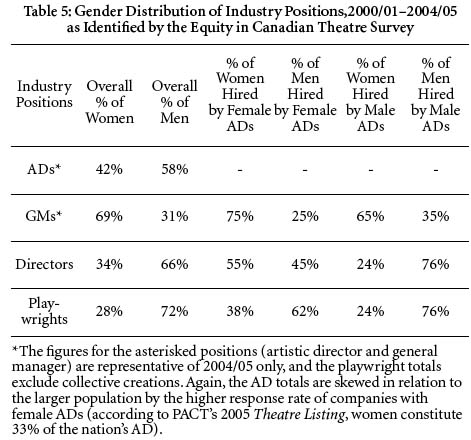

9 The statistics pertaining to directors are a little better than those for female playwrights, though the impact of the gender imbalance in artistic directorship is once again apparent. According to the Equity Survey results,women directed 34% of the productions and men directed the other 66% (see Table 5), with the percentage of female directors in Atlantic Canada sitting slightly higher than the national average at 36%.13 While the figures show marked improvement in the representation of female directors over time, going from 13% in the early 1980s to 34% at the beginning of the twenty-first century (see Table 4), they are still not indicative of gender equity. What is particularly noticeable is the major discrepancy (of 32%!) between the number of female directors hired by companies with female ADs and the number hired by companies with male ADs (see Table 5), which reveals a clear statistical correlation between the gender of a company’s AD and the rate of hire for female directors (Burton 21).

Table 4: Comparison of Study Results over Time -Fraticelli’s 1982 Report and the 2005 Equity in Canadian Theatre Survey National Study

Display large image of Table 4

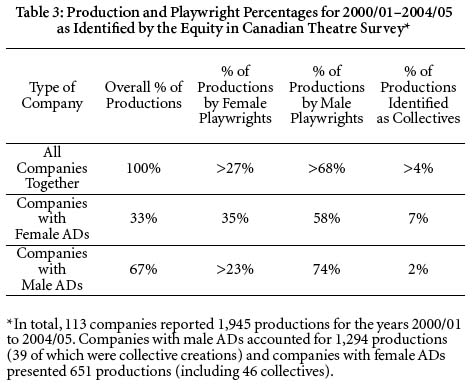

10 These numbers reveal that the comparatively low participation rates of women, particularly as artistic directors, have a definite impact on the number of productions by female playwrights and directors, and by extension, on what and who appears on the nation’s stages. The gap between what appears on stage and who is watching is emphasized further by the predominance of women in theatre audiences. In keeping with Fraticelli’s earlier findings, the Equity Survey found that, on average, 59% of the theatre companies’ audiences are female (see Table 5), a figure supported by other research studies (Burton 20).14 Since women form the majority of theatre-going audiences, it seems logical, particularly from a marketing perspective, that companies offer programming choices that reflect and appeal to the majority of their (mostly female) constituents. Doing so could potentially improve audience attendance figures, and it could help to offset the industry’s gender imbalances, as there would likely be increased opportunities available to women seeking work in theatre.15

11 There are certainly many women interested in a career in theatre and women still comprise the majority of Canada’s theatre students in the twenty-first century. The ratio of female to male students has held steadily at 3:1 at the theatre department at York University (York 1), a ratio comparable to that found in the theatre department at Dalhousie University, the largest theatre program in the Maritimes.16 Not surprisingly, the situation is similar at Newfoundland’s Memorial University, though male students outnumber female students in the new Diploma in Performance and Communications Media Program (Lynde).17 Even at the graduate level, there is a high involvement of women. In the arts and communications sector, female students comprised 61.4% of PhD candidates, in comparison to the 45.6% marker established for overall female PhD enrollment in 2003 (Robbins and Ollivier). While the majority of theatre students are women, they often graduate with less experience than their male counterparts,particularly as actors, because many of the plays produced in such programs have few roles for women (Taylor). Tessa Mendel, director, educator, and founder of Halifax’s Women’s Theatre and Creativity Centre, recalls her own experience teaching in university theatre programs in the late 1990s when she encountered female students who wanted to be professional actors, and who, after three years of study, had never had a part in a play. With less experience and presumably concomitant confidence, and facing an industry that clearly employs men more often than women, it is hardly surprising, as Fraticelli commented back in the early 1980s, that "graduation seems to mark the end (rather than the beginning) of most of our professional careers" ("Any Black" 9).

Table 5: Gender Distribution of Industry Positions,2000/01–2004/05 as Identified by the Equity in Canadian Theatre Survey

Display large image of Table 5

12 Evidently, the gender imbalance in the employment patterns of the Canadian theatre sector revealed by Fraticelli’s 1982 study are still embedded and reflected in the findings of the 2005 Equity Survey as well as other corroborating source materials. Yes, there has been improvement in the overall numbers of women working in the sector in the twenty-first century, but barriers to full and equal access remain, preventing women from fully contributing to Canada’s theatrical culture. As Avis Lang Rosenberg theorized for the visual art world (and as quoted by Fraticelli to describe the plight of women in Canadian theatre in the early 1980s), women encounter a"gap between aspiration and legitimation"("Status"5). Women train and aspire to work in the theatre industry in signifi-cant numbers,yet the number of women who manage to access key creative positions is comparatively low, particularly at the more mainstream theatres, thus demonstrating the presence of a persistent and significant barrier, or gap, that must be overcome by women in order to achieve actual realization, or as Rosenberg phrases it,"legitimation."

13 The marginalized status of women in theatre is not unique to Canada, but indicative of a larger global problem. In the United Kingdom, a 1994 study revealed that women held 34% of the industry’s senior posts, which constituted a minimal (1%) increase over a ten-year period. Productions written, devised, or adapted by women or from books by women accounted for only 20% of all work performed in 1994 (a 2% decrease from ten years previously) and, shamefully, women controlled only 8% of the allocated Arts Council Funds (Long 103). The UK statistics indicate slim improvement–stagnation even–from the 1980s to the 1990s, and in the case of staged productions, actual regression. Studies conducted in the United States indicate similar trends, with figures lagging behind the Canadian statistics and suggesting only marginal growth as in Britain. Once again, the increase in the number of women in the US industry is less apparent in the larger mainstream theatres (Jonas and Bennett, "Statistical Findings"). Clearly there are still many challenges to overcome for women in the theatre industry worldwide.

Challenges

14 The challenges facing women in theatre in Canada and elsewhere must be considered within the context not only of gender disparity, but also of the difficulties faced by everyone in the theatre sector, regardless of gender or location. In general, to work in theatre is synonymous with being overworked and underpaid. While artists worldwide suffer from limited funding, arts funding in Canada is lower than in many countries (McCaughey 1),18 and while the Canada Council for the Arts recently increased funding for specific projects, there has been little new support for theatre companies for several years.19 In addition, the Canada Council’s emphasis on projects at the expense of people leaves emerging artists, in particular, struggling to make a living in theatre.20 While access to funding is limited nationwide, the impact is felt more acutely in areas where provincial governments also chronically under-fund the arts community.21 The lack of government funding, combined with the emphasis on raising corporate monies, has also made it increasingly difficult to produce work perceived as innovative or "risky" (Farfan 60). Work that fails to fit neatly into defined categories doesn’t stand a chance (Mendel).22 Moreover, there is less private funding of theatre in Atlantic Canada than in other areas of the country.23 In addition to the challenges caused by under-funding, theatre artists in Nova Scotia struggle with a regional theatre unsupportive of local talent.24

15 The chronic under-funding of the arts that is particularly acute in Atlantic Canada causes hardship for all artists, but it magnifies the issues for women working in theatre in the region. Wendy Lill, playwright and former NDP Critic for Culture and Communications, declares that, "in Atlantic Canada [. . .] we feel like we are being screwed by everyone else!"and points to the"deep anger" felt against the federal government and large corporations, as well as the media stereotyping of the region as"being kept afloat by [. . .] central Canada."While Lill suggests that this sense of battle fuels the literature of the Atlantic Provinces, the struggle, as Mendel argues, still means that"everything is so much harder."The struggle may also, ironically, raise the profile of women in certain areas.25 As already noted, in Newfoundland and Labrador, the majority of artistic directors are women (Lynde), and they predominate as theatre managers throughout Atlantic Canada. The Equity Survey found that 69% of the nation’s general managers are female (Burton 35), and a 2004 Ontario Arts Council study determined that women comprised 67% of general managers, managing and executive directors, regardless of the size of the theatre (Bradley 4). In the same year in the Maritimes, women held the position in eleven of twelve companies that specifically identified a general manager, and in the same season in Newfoundland and Labrador, all theatre administrators were female (Keiley and Brophy 15). One explanation for this regional anomaly is that these positions are so poorly paid that lack of remuneration discourages men from applying.In places with more resources, there is more competition for those resources.26 As one participant in the Newfoundland roundtable on the status of women in theatre succinctly noted, "When things get really competitive, that’s when women get shoved out" (Lynde).

16 While women are underrepresented in many areas of paid employment in the theatre industry, the numbers are even more dismal for older women. One explanation for the lack of older female actors is that few canonical plays have roles for them: women are forced to leave the stage long before the usual retirement age. This may account for the lack of women on the stage, but other factors must explain their absence behind the scenes. Repeatedly, women identify the problem of juggling family responsibilities with a theatre career that demands long hours (Farfan 63-64). Theatre founder and manager Kate Holt believes that this struggle to work, make a living wage, and "have a life," whether that includes a family or not, explains why many women leave the theatre; she warns that even more women will leave if things don’t change (17). For those who choose to stay, there is often the challenge of coping with increasing family demands at the very time when women should be (and men are) furthering their careers (Banks).27 Mendel is blunt about the effect of motherhood for women in theatre, believing it to be the "biggest impediment" to their work. Certainly, there is a lack of support for women trying to juggle family demands and career; one entrenched in social policies that fail to provide parental leave for self-employed workers or adequate publicly-funded daycare (White 4-5). In addition, the very work that women do in theatre may exacerbate the problem. The role of general manager—a position for which women are disproportionately hired—frequently requires the multi-tasking at which many women are adept (Lynde), but exerts incredible demands. Furthermore, there is the perception, even by the women themselves, that taking an administrative position is an indication that they somehow lack a certain creative spark.28 It is little wonder that these women, overworked, underpaid, under-appreciated, and now with damaged self-confidence, throw in the towel.

17 Other barriers identified by women working in theatre are traditional hierarchical practices and the increasingly corporate environment that, to quote Robert Wallace, "equates culture with institutions and art with business" (49). Women, overburdened with responsibility and lacking authority, may feel silenced and unable to bring about beneficial change (Holt 18). As a result, entrepreneurial women often create their own opportunities outside of mainstream theatre. Indeed, many theatre companies were co-founded by women following the activism of the seventies and, while the contribution of women to these companies is inestimable, such work may also isolate and marginalize them.29 Women who have formed companies to work on their own terms commonly complain of self-subsidy, isolation, marginalization, and the feeling that they are single-handedly re-inventing the wheel each time around.30 In addition, working outside of the mainstream may not effect the necessary change. Citing Virginia Valian’s research, Susan Jonas and Suzanne Bennett note that, "because women operate outside of the mainstream, they tend to ‘reform’ it less quickly than they could from within" ("Challenges"). The entrepreneurial spirit that prompts the founding of theatre companies may also lead women to move from one role to another within the theatre industry. The difficulty of finding roles to play, and particularly roles that explore female experience in a non-stereotypical fashion, has led some actors to turn to directing and writing. Playwright Natasha MacLellan readily admits,"[P]art of the reason I write is so I have parts to play." She goes on to say,"I feel that strong roles for women are sorely lacking from the stage and screen, and I see a role for myself in creating characters that represent the female well. We have to write these roles. It’s our responsibility."

18 Unfortunately, turning to writing does not automatically resolve the challenge of being a woman in theatre. Though there are certainly successful female playwrights, such as Sharon Pollock, Judith Thompson, and Ann-Marie MacDonald, in general, the situation of women playwrights in Canada is downright heartbreaking. The statistics demonstrate that they are not accessing Canada’s stages, particularly the mainstages, and second productions are reportedly virtually impossible to come by. Saskatchewan playwright Dianne Warren (author of Serpent in the Night Sky, short-listed for a Governor General’s Award in 1992) is no longer writing for the theatre, as her plays are not being produced,and she is currently focusing on fiction instead.Even the distinguished author and feminist playwright Margaret Hollingsworth (author of Poppycock, Ever Loving and other plays) has not had a fully staged professional production of her work in many years. In neither case is this situation due to a lack of effort on the playwright’s part. Hollingsworth has started to send her work abroad to Europe where she is finding a more receptive market than at home, an indicator perhaps of another persistent problem: the perception of the work by female playwrights.

19 Despite the significant body of plays by women in all provinces, Canada’s mainstage theatres still view plays by women as too risky and unpopular to produce on a regular basis. Sadly, even women buy into this negative attitude towards women’s stories (Mendel), which possibly explains why, even where there is a high proportion of female artistic directors such as in Newfoundland and Labrador, few plays by women playwrights are produced. The belief that women’s plays are risky or unpopular may be aggravated by the critical reception given to the work of male and female playwrights. Critic Jonathan Kalb notes that when male playwrights challenge traditional ideas of form, they are considered innovative risk-takers; when women do it, "‘they are often treated as though . . . they don’t know what they are doing’" (qtd. in Jonas and Bennett "Challenges"). Susan Stone-Blackburn suggests that female playwrights must choose"between writing for the large audiences that want plays that fit comfortably into our traditional phallocentric theatre practices and writing for the small audiences that are receptive to plays that portray a woman’s perception of women’s experiences" (46). Nova Scotian playwright Catherine Banks says that she does not think about what will sell— otherwise she would not have written Three Storey, Ocean View with its large cast of ten women and two men.31 Banks goes on to note that in regions such as Atlantic Canada that lack a small press which publishes plays, playwrights are further challenged because when plays go unpublished, they are often not considered for awards, research, or inclusion in school curricula.

20 The challenges faced by women in theatre, both in Atlantic Canada and elsewhere, are not simply a result of individual situations, though the isolation many women encounter often prevents this realization. Too often, women who attempt to articulate their experience are silenced; their complaints are dismissed as lacking credibility, or the women are labeled feminist, which, in popular conception, brands them as"aggressive and‘exceptional’"(Godard 22). Unfortunately, the difficulties faced by these women are not exceptional, but systemic to the theatre sector. However, even when women’s concerns are voiced, the expression is often confined to the margins, such as in special print issues focusing on women. While these collections may be a useful way of gathering together a more substantial body of work, they also contain and remove that work from the mainstream (Bennett 145). Despite the twenty-plus years since Fraticelli noted that the difficulties encountered by women could not be attributed to a "single closed door" but rather to a "series of diverse and deeply systemic obstructions which define the exclusion of women from the Canadian theatre" ("Status"26), conditions have changed little. It is time to amend the situation. The question is how.

Solutions

21 Given the complexity of the challenges facing women in theatre, there is no easy solution to increasing their presence so that there is true employment equity in the industry. There are, however, a number of levels at which action can and should be taken to encourage women in the theatre community. Without question, increased government funding for the arts would help all theatre professionals, including women. Unfortunately, the support of governments at all levels and of all political persuasions is frequently limited to lip service and token increases. Neither will government funding alone solve the problem, as the findings of the Equity Survey suggest, for practices within the industry itself add to the challenges faced by women. The theatre community must, in the words of Andy McKim, past-President of PACT,"work to raise the profile of women artists and it is not enough to settle for token efforts in this regard" (2). The Equity Survey reveals that the influence wielded by artistic directors, along with the disproportionate number of male ADs, contributes to gender imbalance in other areas, most notably in the hiring of female directors and the production of plays written by female playwrights. Aware of the role played by institutional practice, the Equity project plans to further explore production practices and employment patterns in Canadian theatre to provide the most thorough gender-based analysis of the Canadian theatre sector to date.32 Still, increasing the number of female ADs is statistically most likely to boost the number of female directors hired and the number of productions by female playwrights.

22 Improving the number of female ADs is not simply a matter of encouraging theatres to adopt policies designed to promote employment equity, however. Change must occur both at the institutional and individual levels, and women must be encouraged to apply for positions of authority within theatre. Gay Hauser, co-founder of Mulgrave Road and Eastern Front theatres and current General Manager of Live Art Productions, maintains that women tend to undervalue their work and therefore often fail to apply for positions of greater authority as they do not believe they have the necessary experience or qualifications. In an industry that increasingly requires artists to market themselves, women must do just that. Even though it may be contrary to the way many women have been socialized, "they need to toot their own horn" (Banks). Moreover, women need to recognize that there is strength in working collectively, rather than individually, and supporting each other. Recently, the emphasis—for projects and funding organizations—has been on the exploration and celebration of diversity, and while this is crucial, it can also result in separation and further marginalization. ahdri zhina mandiela notes that there has been much discussion "about issues around silencing, about issues around appropriation, around…access… And in all these discussions the biggest loss is [our] collectivity, that we seem to constantly be searching for, that women’s voice. How do our voices come together?" (Peerbaye 23)33 The answer to this question can perhaps be found through women in theatre creating their own supportive community. Hauser states that we need to "reinstitutionalize some of our feminist notions." Lill agrees, "[I]f we want women working in theatre—women playwrights, actors, directors, art directors, set designers—then we have to support them. We have to seek them out and support them." Women at the Halifax Women in Theatre workshop identified two methods by which that support can be realized: networking and mentorship. These practices have traditionally aided men in their careers and have often excluded women, but some women are now exploring ways of developing these methods of support. Mentorship, in particular, has been identified by women in business as"the single most influential factor in career advancement" (Jonas and Bennett, "Strategies").

23 To conclude, the low number of women visible on and behind the professional stages in this country is not an aberration, but a result of traditional hierarchical practices and devaluation of women’s contributions to the theatre industry. These challenges are frustrating for women working in theatre, and disheartening for the new graduates who hope to have a career in the industry. They also have a detrimental effect on the theatre sector itself. Tired of being unable to find work that is sufficiently challenging and financially secure, women move into other areas of employment and take their talent and vision with them. The loss of their potential contribution to theatre in Canada and elsewhere is immeasurable. Change is possible, but it must be initiated on several levels. Women need to have the confidence to market themselves; they need to support one another through networking and mentorship; and the theatre community needs to actively identify and change practices that cause gender inequity. Given that the conditions which work against women in theatre likely reflect conditions elsewhere in society, we can hope that eventually, when real change is achieved in the theatre community, the same will be realized in society at large. [ornament20]

Table 6: Regional Breakdown of Female Audience Percentages for 2004/05 as Identified by the Equity in Canadian Theatre Survey*

Works Cited

"Applebert." Broadside 4.3 (December 1982/January 1983): 7.

Banks, Catherine. Personal Interview. 17 May 2005.

Bennett, Susan. "Feminist (Theatre) Historiography/Canadian (Feminist) Theatre: A Reading of Some Practices and Theories." Theatre Research in Canada/Recherches théâtrales au Canada 13.1-2 (Spring/Fall 1992): 144-51.

Berland, Jody. "Applebaum-Hébert Report." The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2005. Historica Foundation of Canada. 20 February 2007 http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com Path: Encyclopedia of Music in Canada/Publications/ Applebaum-Hébert Report.

Bradley, Pat, Research Manager, Ontario Arts Council/Conseil des Arts de L’Ontario."The Status of Women in Theatre: The Ontario Experience." ArtFacts/Artifaits 8.1 (January 2004): 1-4.

Burton, Rebecca."Adding It Up: The Status of Women in Canadian Theatre – A Report on the Phase One Findings of Equity in Canadian Theatre: The Women’s Initiative." October 2006. Professional Association of Canadian Theatres. 2006. 20 February 2007 http://www.pact.ca. Path: Services/ Communications/Publications.

Campbell, Naomi. "Unscientific Poll of Canadian 2004-2005 Theatre Season." Unpublished.

Campbell, Naomi and Yvette Nolan. "The Shocking Results Discovered at the Hysteria Festival’s Panel Discussion: Reopening the Rina Fraticelli Report on the Status of Women in Canadian Theatre, An Un-Scientific Straw Poll of the 2003-2004 Mainstage Seasons Across Canada." Unpublished Table.

Cowan, Cindy. "Messages in the Wilderness." Canadian Theatre Review 43 (Summer 1985): 100-10.

Czernis, Loretta. "President’s Column: Envisioning a Family Friendly Campus." CAUT Bulletin Online. December 2004. 20 February 2007 http://www.caut.ca/en/bulletin/issues/ 2004_dec/pres_mess.asp.

Equity in Canadian Theatre: The Women’s Initiative. "Equity in Canadian Theatre Survey." 2005. Unpublished.

Farfan, Penny, ed. "Women Playwrights in Regina: A Panel Discussion with Kelley Jo Burke, Connie Gault, Rachael Van Fossen and Dianne Warren." Canadian Theatre Review 87 (Summer 1996): 55-64.

Fraticelli, Rina."‘Any Black Crippled Woman Can!’ or A Feminist’s Notes from Outside the Sheltered Workshop." Room of One’s Own 8.2 (1983): 7-18.

—-. "The Status of Women in the Canadian Theatre." A Report Prepared for the Status of Women Canada. June 1982. Unpublished.

"Funding." The People. Canada e-Book. Statistics Canada. 26 May 2003. Revised 22 April 2004. 20 February 2007 http://142.206.72.67/02/02f/02f_010_e.htm

Gilbert, Mallory and Nancy Webster."On the Evolution of Theatre Administration." impact! 16.1 (Winter 2005): 10-14.

Godard, Barbara."Between Repetition and Rehearsal: Conditions of (Women’s) Theatre in Canada in a Space of Reproduction." Theatre Research in Canada/Recherches théâtrales au Canada 13.1-2 (Spring/Fall 1992): 18-33.

Group of Concerned Artists. "The Neptune Retrograde." Letters. The Coast 12.36 (10-17 February 2005). 20 February 2007 http://www.coastclassic.ca/issues/100205/letters.html

Hauser, Gay. Personal Interview. 17 May 2005.

Hill Strategies Research Inc. "Performing Arts Attendance in Canada and the Provinces–Detailed Tables." Research Series on the Arts 1.1 (January 2003). Hill Strategies Research Inc. 20 February 2007 http://www.hillstrategies.com/resources_ details.php?resUID=1000067&lang=0

—-. "Donors to Arts and Culture Organizations in Canada." Research Series on the Arts 2.2 (January 2004). Hill Strategies Research Inc. 20 February 2007 http://www.hillstrategies.com/resources_details.php?resUID=1000032&lang=0

Holt, Kate. "Why Some Women Love & Leave Theatre— Questions, Answers and Tales from the Front." impact! 16.1 (Winter 2005): 17-18.

Jonas, Susan and Suzanne Bennett."New York State Council on the Arts Theatre Program Report on the Status of Women: A Limited Engagement?" AmericanTheatre Web. January 2002. 20 February 2007 http://www.americantheaterweb.com /nysca/opening.html Sections: "Statistical Findings," "Strategies," and"Challenges."

Keiley, Jillian, and Ann Brophy. "On Being an Artistic Director— and a Newfoundlander." impact! 16.1 (Winter 2005): 14-16.

Lill, Wendy. "Politics and Theatre." Women in Theatre: The Maritime Experience. Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax. 19 March 2005. Unpublished.

Long, Jennie."What Share of the Cake Now? The Employment of Women in the English Theatre (1994)." The Routledge Reader in Gender and Performance. Ed. Lizbeth Goodman with Jane de Gay. London: Routledge, 1998. 103-107.

Lushington, Kate. "Notes Towards the Diagnosis of a Curable Malaise—Fear of Feminism." Canadian Theatre Review 43 (Summer 1985): 5-11.

Lynde, Denyse."Equity—A Newfoundland Snap Shot."Women in Theatre: The Maritime Experience. Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax. 19 March 2005. Unpublished.

MacLellan, Natasha. "Re: Women in Theatre." Email to Reina Green. 17 January 2005.

McCaughey, Claire. "Comparison of Arts Funding in Selected Countries: Preliminary Findings." Canada Council for the Arts. 28 October 2005. 20 February 2007. http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e/research#4/

McKim,Andy."President’s Report."impact! 16.1 (Winter 2005): 2-3.

Mendel, Tessa. Personal Interview. 17 May 2005.

Nova Scotia Department of Tourism, Culture, and Heritage. "Annual Accountability Report for the Fiscal Year 2003-04." Government of Nova Scotia. 20 February 2007 http://www.gov.ns.ca/dtc/pubs/AccReport04.pdf.

O’Brien, Gisela. "Re: Looking for Information." Email to Reina Green. 18 May 2005.

Professional Association of Canadian Theatres. The Theatre Listing: A Directory of Canadian Professional Theatre, 2005. PACT: Toronto, 2004.

Peerbaye, Soraya, ed. "Look to the Lady: Re-examining Women’s Theatre." Canadian Theatre Review 84 (Fall 1995): 22-25.

Robbins, Wendy and Michèle Ollivier. "Ivory Tower 2: Feminist and Equity Audits 2006 – Selected Indicators for Canadian Universities." Canadian Association of University Teachers. PAR-L, with assistance from CAUT and CFHSS. 17 May 2006. 20 February 2007 http://www.caut.ca/en/issues/women/ ivorytowers2006.pdf.

Stone-Blackburn, Susan. "Recent Plays on Women’s Playwriting." Essays in Theatre/Études théâtrales 14.1 (November 1995): 37-48.

Taylor, Kate. "Systemic Problem Smothers Half the Talent." Globe and Mail. 8 December 2004: R1.

"Today’s Voices." impact! 17.1 (Winter 2006): 4-7.

Union des artistes, en collaboration avec Mmes Francine Descarries et Nadine Raymond de L’Alliance de recherché IREF, UQAM. "Résumé du Rapport du Comité des Femmes Artistes Interprètes de L’UDA." June 2004.

Wallace, Robert. Producing Marginality: Theatre and Criticism in Canada. Saskatoon: Fifth House, 1990.

White, Lucy."Executive Director’s Report: Don’t Stop Yet!" impact! 16.1 (Winter 2005): 4-5.

Women’s Task Force, Canadian Actor’s Equity Association. "Opportunities for Women in 32 Toronto Theatres, From 1980 – 1983." Table. University of Ottawa, Canadian Women’s Movement Archive. X10-1, box 133,"Women in Theatre" file.

Notes