THE MUSICAL SETTING OF LA CONVERSION D'UN PÊCHEUR DE LA NOUVELLE-ÉCOSSE

Timothy J. McGee

Considering the importance of La Conversion in the history of French-Canadian theatre, and the high quality of the libretto, the musical setting comes as a

disappointment.

The composer, Jean-Baptiste Labelle (b Plattsburgh, N.Y. 1828- d Montreal 1897), was a pianist, organist, and composer well trained and widely regarded

during his lifetime. He studied in Paris with the piano virtuoso Sigismund Thalberg, and toured the cities of North and South America as a soloist. For most of

his career he held the post of organist at Montreal's Notre-Dame Cathedral, and he taught at a number of convents and colleges in or near Montreal. From time

to time Labelle produced concerts, for example the Grand Operatic Concert in 1857, in which he presented excerpts from works by a number of the finest

19th-century composers such as Bellini, Donizetti, and Schubert.

His compositions include a number of large and small works: ballads, patriotic songs (including '0 Canada! mon pays, mes amours!', words by G.-É. Cartier),

piano compositions (some with patriotic titles, such as 'Marche canadiennel), and at least two cantatas, La Confédération and Cantate aux zouaves pontificaux.

He compiled Le Répertoire de l'organiste, a Gregorian anthology with accompaniments by him (10 editions beginning in 1851); a collection of popular songs,

Les Chansons les plus populaires; and in 1887, Échos de Notre-Dame, a collection of his own choral pieces. 1

With Labelle's training and background one would expect a high calibre of music composed for La Conversion d'un pêcheur de la Nouvelle-Écosse. That we are

disappointed suggests that the state of the art of musical composition in Canada in the middle of the 19th century allowed for some amateurish products along

with respectable works.

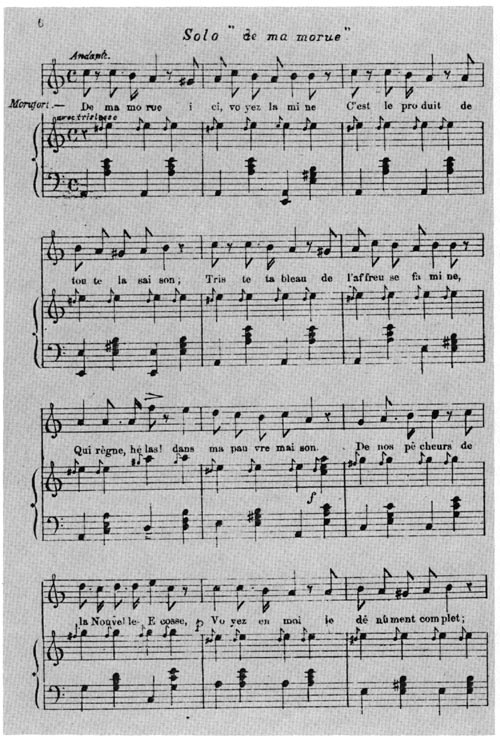

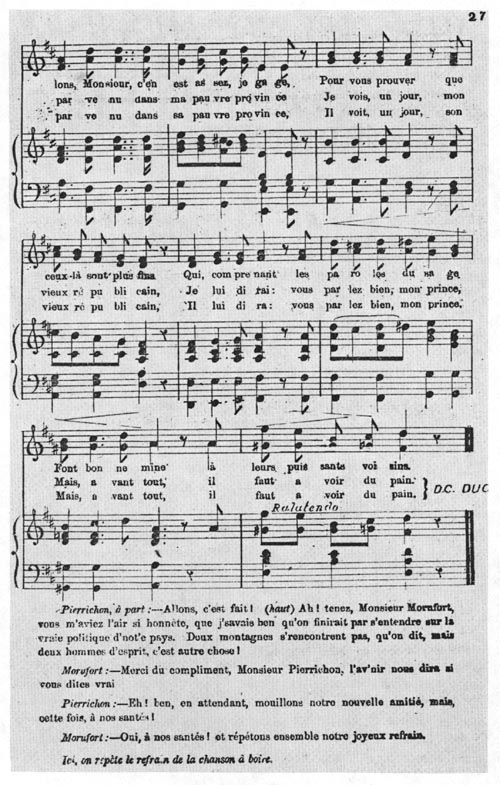

To set the text for La Conversion, Labelle provides an overture, seven songs (two of them duets), and a recitative, all with piano accompaniment. The form of all

songs is determined by the text: that is to say that Labelle wrote melodic phrases to mirror the metre and rhyme of the poetic texts. The style of the song writing

is quite simple, involving a limited demand on singers and pianist - clearly a work intended to be performed by amateur musicians. The most important element in

La Conversion is obviously the text, and the music does not intrude: there are no florid vocal passages, for example, that might distract the listener. The melodies

have the simplicity of folk songs, although they do not sound like folk songs and do not have that kind of quality. In fact, with the exception of a single song, the

music is quite non-descript and does not appear to be related to the text in any way except for the number correspondance between notes and text syllables. The

exception is the setting for 'Quel est cet homme qui m'écoute?', in which Pierrichon wonders about the identity of Morufort. For this song the accompaniment of

the first melody includes the repeated interval of an open 5th in. the bass, suggesting the sound of a bagpipe. In this case Labelle appears to be indulging in a

rather sophisticated communication with the audience - informing them of the identity of Morufort while Pierrichon does not yet know. (Richard Wagner

employs this device in his operas.)

At the time Labelle was setting the text of La Conversion the current style of ballad writing - both in North America and Europe - involved a harmonic

vocabulary more adventurous than what is found in these pieces. The more advanced style included a harmonic language that had been expanding since the early

years of the century. That the modern style was known in Canada at the time of Labelle's writing is witnessed by literally hundreds of songs imported and written

by (mostly amateur) Canadians, including, for example, 'The Lays of the Maple Leaf, or Songs of Canada' by James P. Clarke, published in 1853. The very best

of the mid-19th century style can be seen in the songs of Calixa Lavallée, especially in his 1880 ballad opera 'The Widow'. The music for La Conversion

resembles more a very conservative writing style, similar to that found in Joseph Quesnel's Colas et Colinette of some 80 years earlier, although Labelle's songs

are not nearly as charming as those of Quesnel.

It may have been that Labelle consciously chose to write the music for this operetta in a simple and extremely conservative style. His reason for doing so may

have been aesthetic and / or practical: in order to portray the simple origins of the Nova Scotia fisherman and the Quebec farmer; or in order that the work could

be performed easily by amateurs. Whatever the reason, the unfortunate result is that the music is neither up-to-date nor a charming reference to an earlier style.

Labelle's setting is not offensive: it is merely uninspired and amateurish, and does not approach the quality of the text.

1. Biographical information taken from Helmut Kallmann, Gilles Potvin, Kenneth Winters, eds., Encyclopedia of Music in Canada Toronto, Buffalo, London,

1981, p 510

Return to Article

EDITOR'S NOTES

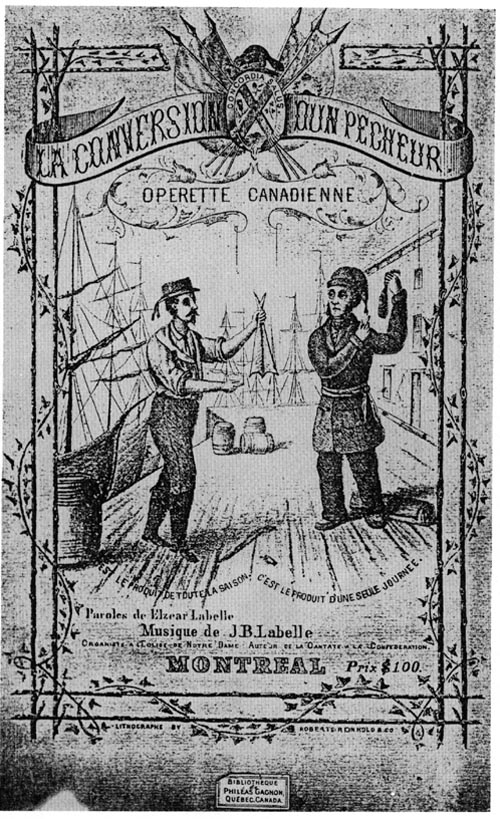

The text here reproduced is that of the first, undated edition, La Conversion d'un pêcheur. Opérette canadienne. Paroles de Elzéar Labelle, musique de J. B.

Labelle, organiste a I'Eglise de Notre Dame, Auteur de la Cantate à la Confédération. Montréal. I am indebted to M. Daniel Olivier and to the Collection

Gagnon of the Bibliothique de la Ville de Montréal for this copy and permission to reprint it.

This is a rare edition, not easily accessible to researchers. Its printing was not completed until sometime after 29 May 1869, for on that date a handsome

advertisement appears in La Minerve, along with the information that 'l'opérette, "La Conversion d'un pêcheur", paroles de M. Elzéar Labelle, musique de J.B.

Labelle, actuellement sous presse, sera jouée pour la dernière fois avant sa publication.' I have been unable to determine the date of first performance, despite

careful examination of, Montreal newspapers for 1867-69; obviously the performance announced here (it was to take place on June 10) was not the first.

The few notes we provide refer to page numbers in the edition here reproduced. The only other edition (text only: no music) is in the posthumous volume, Mes

Rimes, edited by A.-N. Montpetit (Qu6bec: Delisle, 1876), pp 117-148. Apart from the musical score, there is little significant difference between the two texts.

Curiously, the first edition is generally more correct: the second has several typographical errors, some of them serious ('c'est modiquer' instead of 'c'est moi qui'

as on p 15 of our edition), and occasional omissions (the last response of the recitative-duo, p 15, 'De mon côté, c'est déjà fait', is missing in the 2nd edition). The

1876 edition, however, provides useful initial information as to setting: La scène se passe chez un logeur (hôtel) de la rue Saint-Paul, en face du Marché

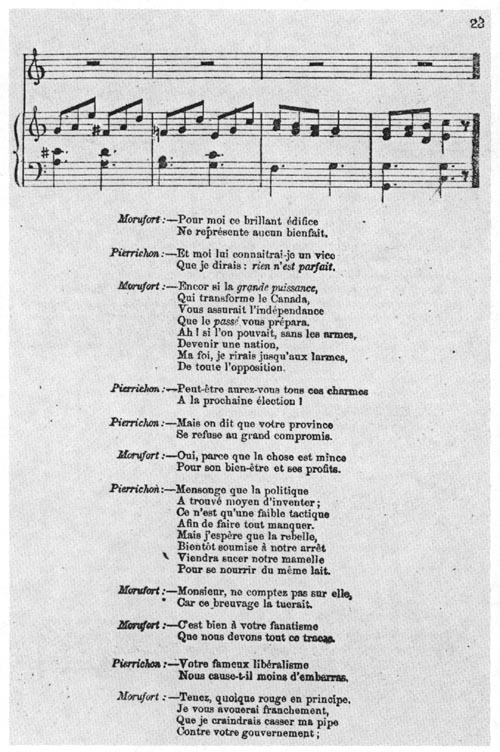

Bonsecours, à Montréal' (p 117), and corrects the attribution to Morufort of the verses at bottom of p 23 in the 1st edition ('C'est bien a votre fatalisme / Que

nous devons tout ce tracas'). The 2nd edition seems correct in ascribing them to Pierrichon, with Morufort responding, 'Votre fameux libéralisme / ... C'est le

moyen de parvenir.'

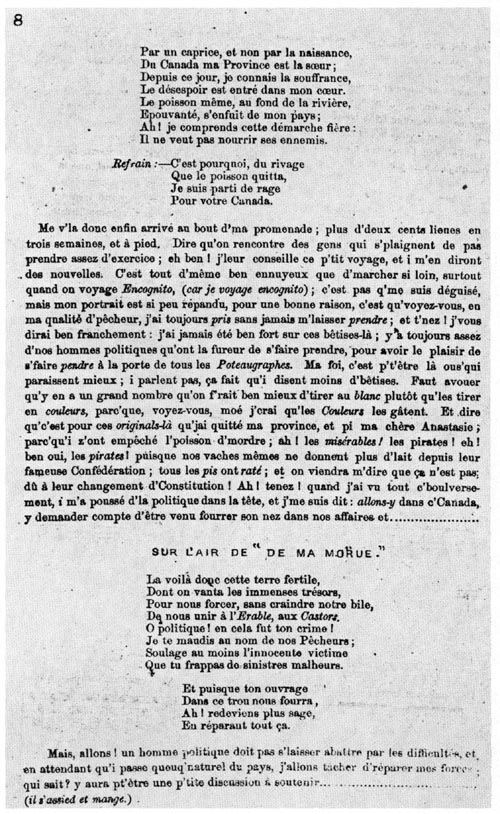

p 8. The text spoken by Morufort is picturesque, full of popular locutions, overflowing with concatenated puns. It is certainly not Acadian French, however; in

fact, it is much closer to that of Pierrichon than to that of Acadia.

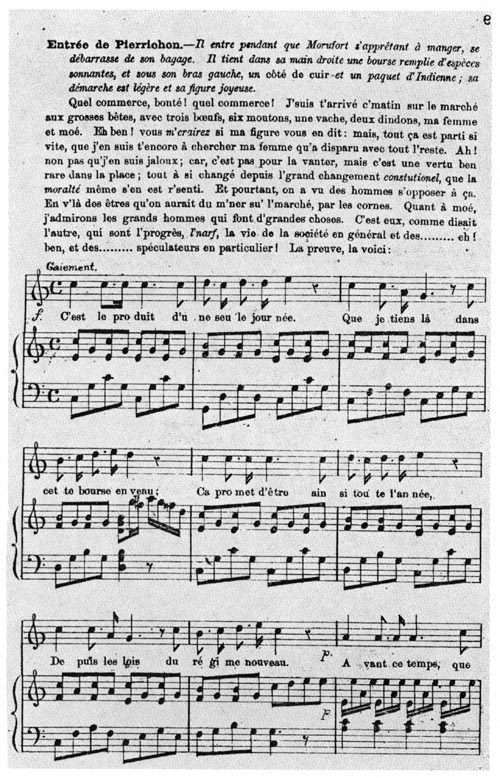

p 9. line 3, 'côté de cuir' c. f. Glossaire du parler français au Canada: 'côté de cuir: moitié d'une peau tannée'. 'paquet d'Indienne': a roll of calico print.

line 13. It is curious that Pierrichon should be the first to use the form 'j'admirons" more usually associated with acadien than with québécois speech.

p 16, line 12ff. In Morufort's long account the author seems to remember the association of the 'je sommes' form characteristic of most Acadian French; but the

'-âmes' form of preterite used here is not characteristic: 'étonnassîmes' (line 25) is closer to it.

line 15-16.Since he netted his Anastasie on 'le premier avril 1850', she is also his 'poisson d'avril': hence, no doubt, the italics.

line 18. The word 'pécheresse' highlights the implicit pun in the title of Labelle's play, since the association between 'pêcheur': fisherman, and 'pêcheur': sinner,

particularly when conjoined with the 'conversion', is unavoidable.

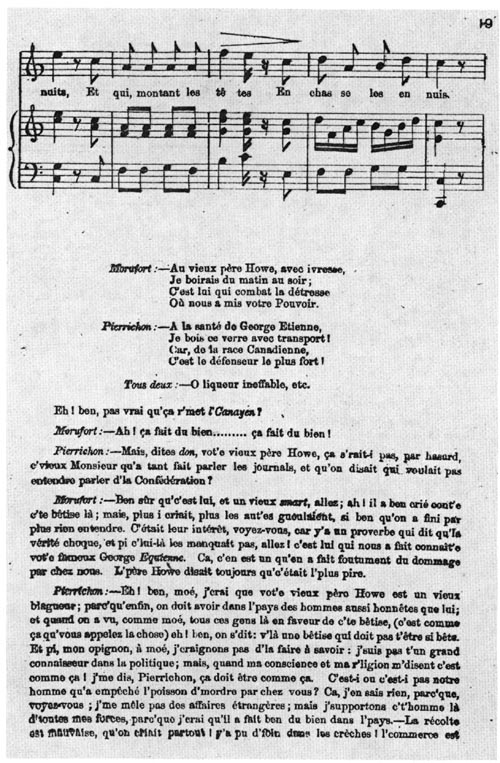

p 19, line 11. 'ca r'met l'Canayen': a pun, the first level of which is a québécois expression equivalent to 'that hits the spot' or perhaps 'that wets one's whistle.'

p 24 line 28.'l'filbleu est Siré': reference to Sir É.-P. Taché, Sir G.-É. Cartier and so many other French-Canadians honoured by the British Crown ('Siré, with

the pun on 'cirer') for their services.

p 25, note at bottom.. The 1876 edition updates: 'Monsieur Howe est devenu un des membres du ministère, puis il a été nommé lieutenant-gouverneur de la

Nouvell-Écosse, sous le régime tant décrié par lui,' then adds the same Parthian shot, 'Qu'on vienne nous dire que Pon n'est pas prophète dans son pays!' (p 143).

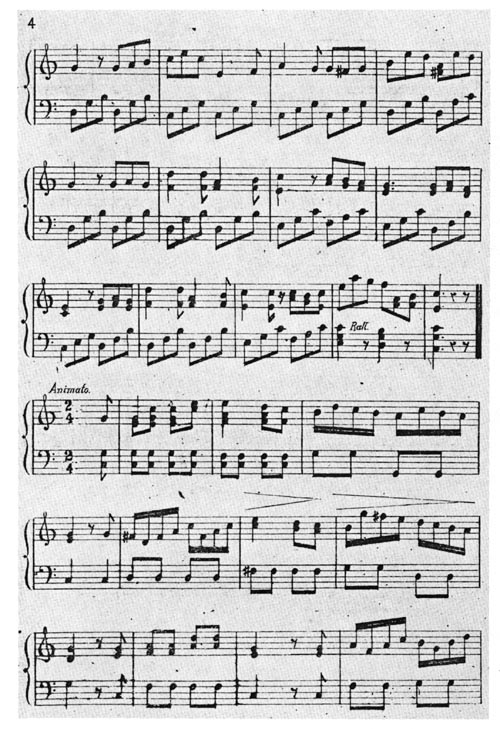

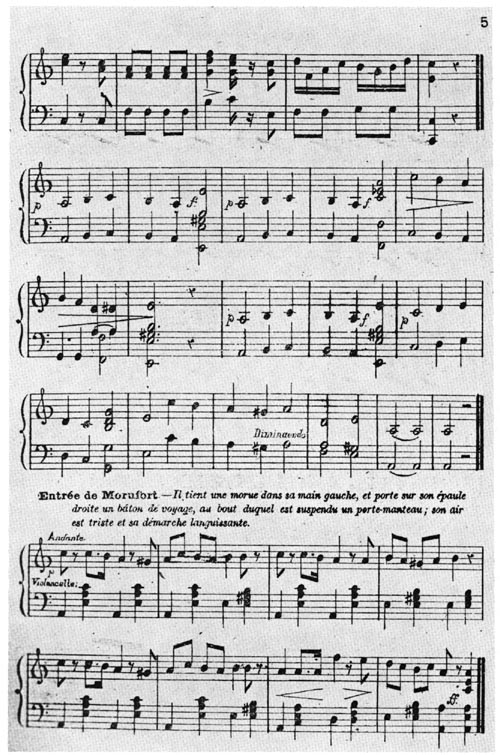

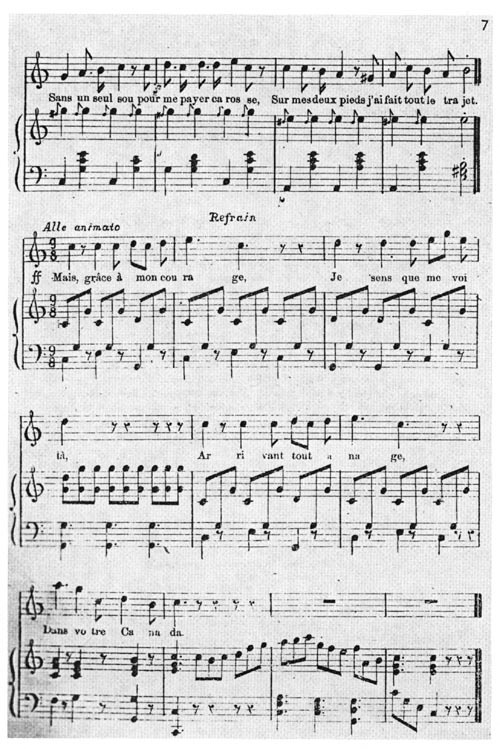

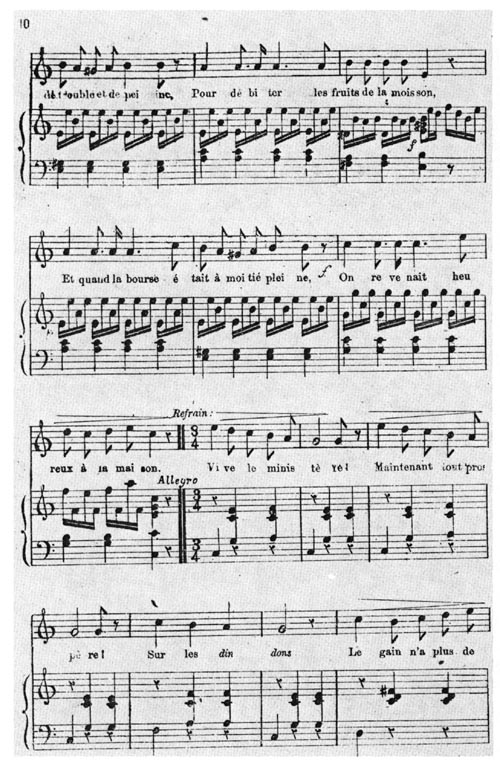

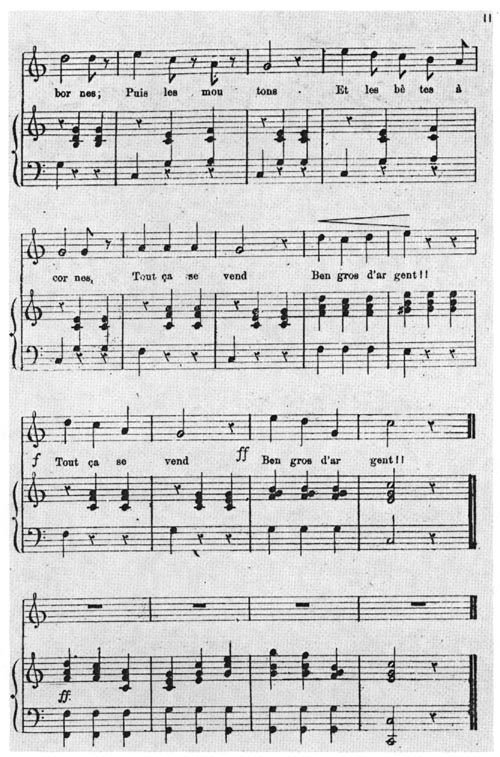

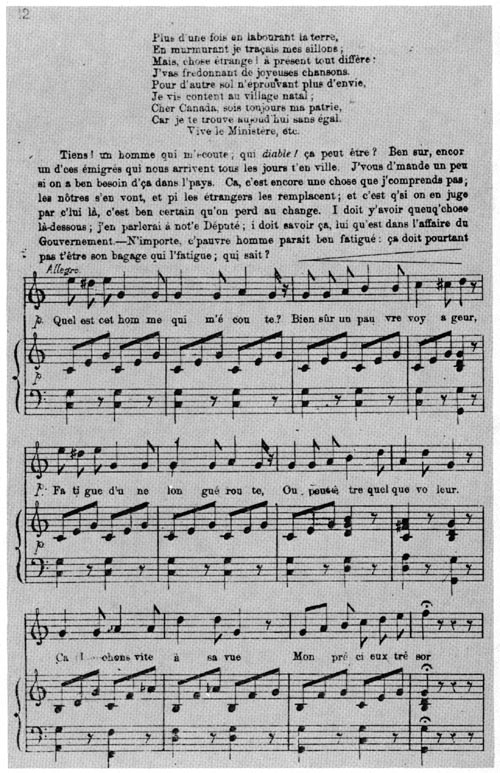

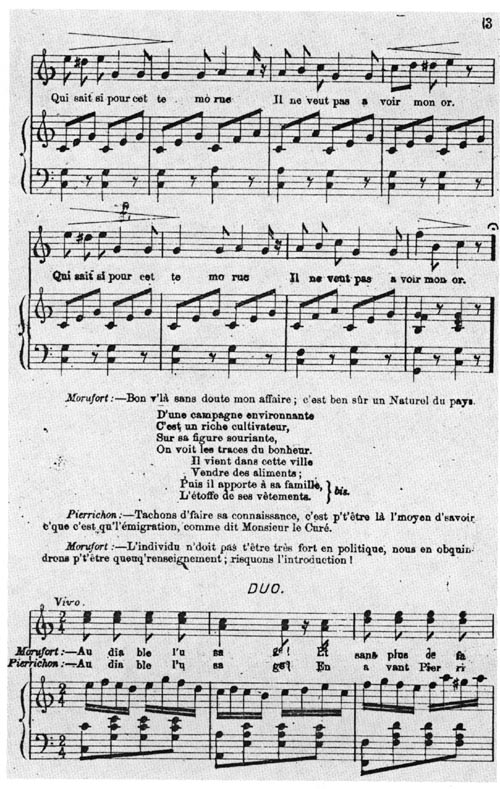

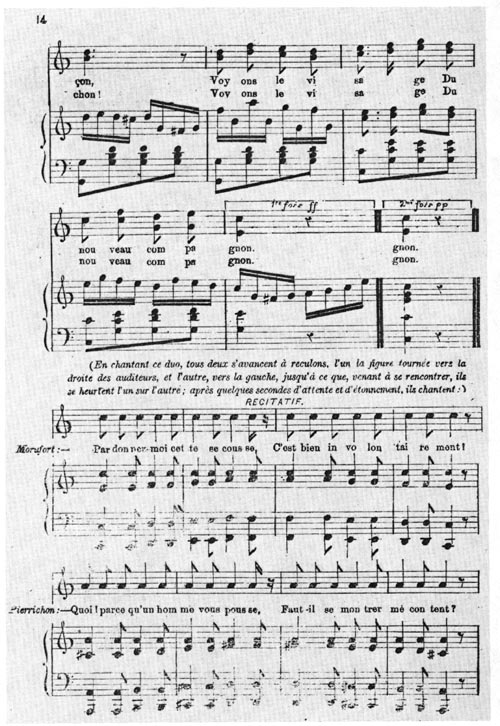

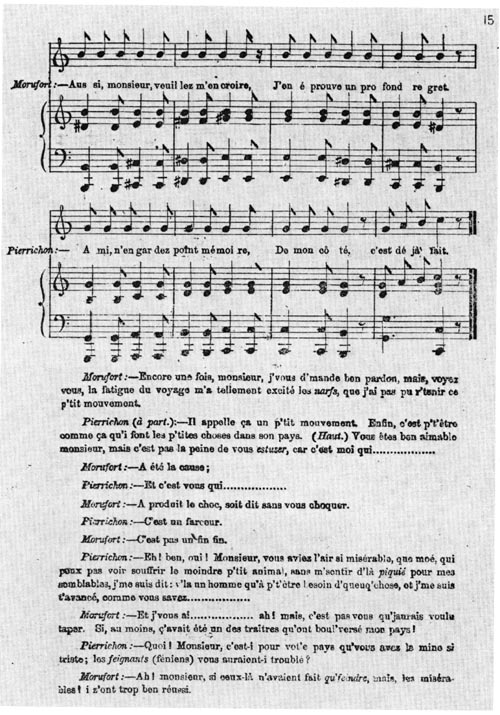

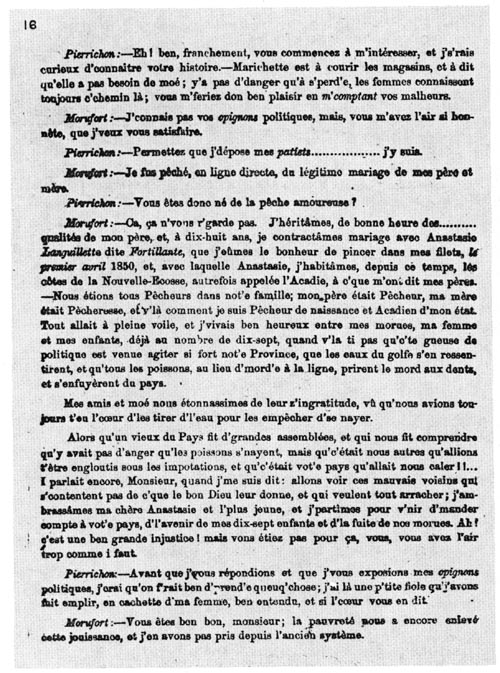

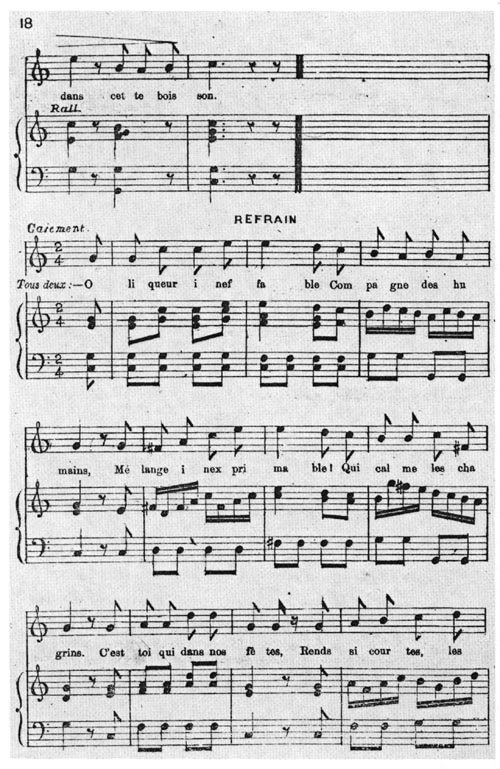

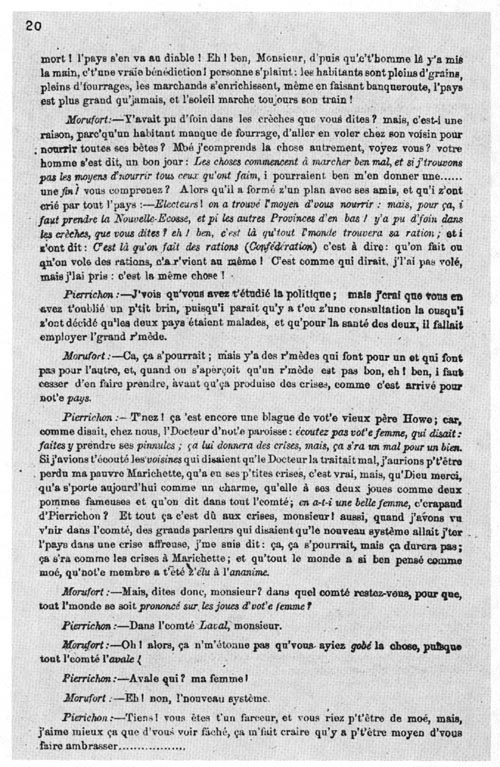

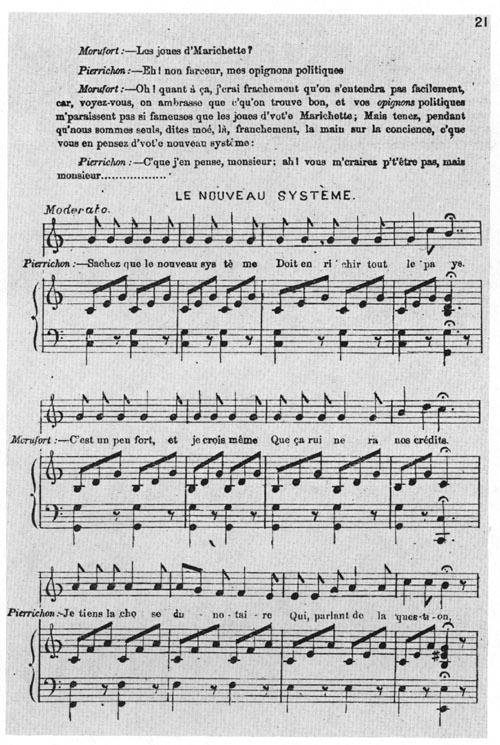

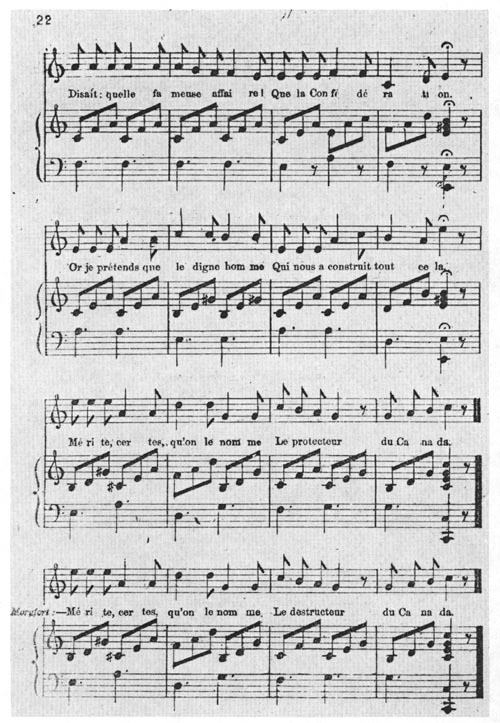

Score of LA CONVERSION D'UN PÊCHEUR DE LA NOUVELLE-ÉCOSSE

Score Page 1

Score Page 2

Score Page 3

Score Page 4

Score Page 5

Score Page 6

Score Page 7

Score Page 8

Score Page 9

Score Page 10

Score Page 11

Score Page 12

Score Page 13

Score Page 14

Score Page 15

Score Page 16

Score Page 17

Score Page 18

Score Page 19

Score Page 20

Score Page 21

Score Page 22

Score Page 23

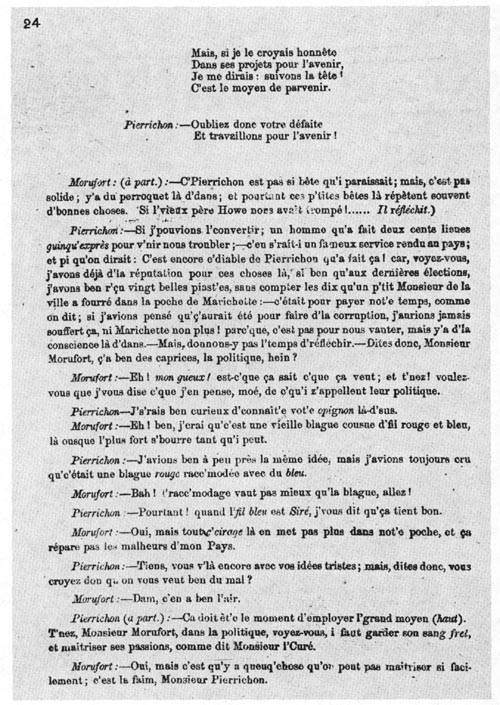

Score Page 24

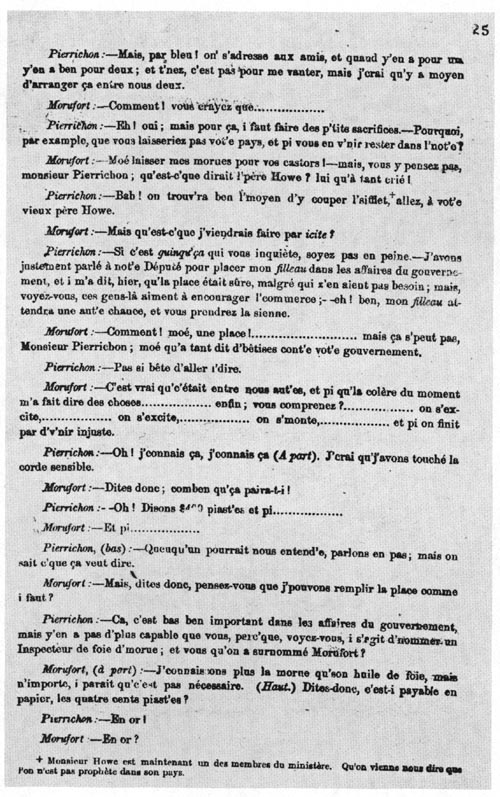

Score Page 25

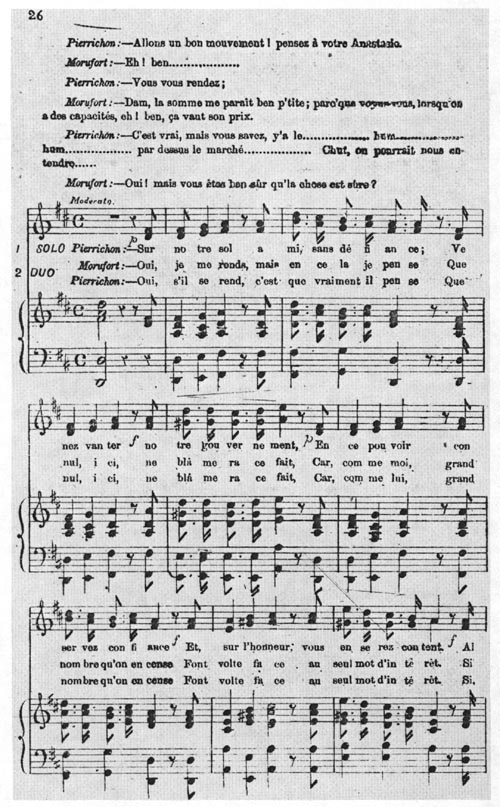

Score Page 26