Display large image of Figure 1

JEANNE KLEIN

To explore a continuum model of empathy, 88 children in grades one, three, and five were interviewed about their emotional responses to Crying to Laugh, a québécois play designed to demonstrate emotional expression. Girls and older children empathized and sympathized by feeling and thinking from female characters' perspectives more than boys and younger children. Boys distanced themselves more than girls by focusing on their personal desires and expectations. Theatrical signs of presentational plays may interfere with empathy bydistracting young children from identifying intended themes.

Afin d'explorer un modèle d'empathie en continuum, 88 élèves de première, troisième et cinquième année du primaire ont été interviewés sur leurs réactions émotionnelles à Pleurer pour rire, une pièce québécoise conçue pour montrer l'expression des émotions. Ce sont lesfillettes et les enfants plus aggs, et non les garçons et les enfants plus jeunes, qui ont manifesté de l'empathie et de la sympathie en pensant et en ressentant à partir du point de vue des personnages féminins. Les garçons, plus que les filles, se sont distancés en se concentrant sur leur propres désirs et leurs attentes personnelles. Les éléments de théâtralisation des spectacles dit de présentation peuvent contrer les manifestations d'empathie en empêchant les jeunes enfants de s'identifier aux thèmes traités.

Young spectators show how they feel honestly through overt, behavioral responses which affect actors' performances and directors' assumptions about what children enjoy and understand (Klein 1992). Audience reception studies can counter adults' misconceptions about children's desires for comedy, fast paced action, "easy" entertainment, and whether they empathize or identify with characters and themes (e.g., Deldime; Hagnell). Such research in the last two decades integrates performance and social science theories to illuminate theatre's communication process with actual not hypothetical readers (e.g., Schoenmakers; cf. Bennett). Cognitive developmental theories and methods have informed my ongoing investigations of the theatrical signs children rely upon to construct meanings from selected productions at the University of Kansas Theatre for Young People (Klein 1987, 1993; Klein and Fitch).

When children watch theatre, they actively explore its visual and aural signs and search for familiar, meaningful ideas based on their schematic concepts of stories and theatre conventions. As selective attention develops, they learn to focus more on central actions and critical dialogue than on distracting, incidental activities to identify main themes in plays. Before the age of six or seven, young children tend to focus on actual, physical appearances until they recognize the need to make inferences about the internal minds of others (e.g., Flavell et al.). Older children infer and compare characters' thoughts and traits against their own self-concepts, while scrutinizing the probability of fictive events (e.g., Damon and Hart). Around the age of eight or nine, an understanding of metaphors and irony develops as they recognize and discriminate literal from symbolic meanings (e.g., Winner). They judge social realism or verisimilitude by how characters and dramatic events compare and apply to their cultural experiences (e.g., Doff). Though children prefer realism from their years of avid television viewing, expressionistic plays may stimulate emotional memories more than realistic styles (Deldime and Pigeon).

According to social cognitive theory, children who empathize or identify with stage heroes will model their behaviors. Psychologists define empathy as sharing vicariously another person's emotions and thoughts, and they distinguish empathy (feeling with) from sympathy (feeling for) by whether viewers focus more on others than on themselves (Eisenberg and Strayer 3-10). The ability to empathize increases with age because older children not only feel with characters' emotions contagiously but they also imagine and think from within characters' perspectives (Hoffman; Strayer). Because feeling sad for someone does not mean that an observer will necessarily help another in distress, empathy may stimulate more cooperative attitudes and helpful behaviors than sympathy. Empathetic predispositions may also be influenced by parents' child-rearing practices and how boys and girls are socialized to express and talk about their emotions (Eisenberg). Thus, empathy may lie at one end of a continuum opposite distancing with sympathy in the middle. These theoretical frameworks and definitions may be used to analyze children's emotional responses to characters in situations.

An Empathy Study with a Québécois Play1

The purposes of this developmental study were to explore a continuum of empathy by: 1) observing and listening to whole group responses in relation to actors' emotions during performances; 2) determining whether individual differences in empathetic and dramatic predispositions before theatre attendance are related to how children think and feel about characters after performances; and, 3) examining children's recall of a play's plot, theme, characters, and actors' emotional situations. Most importantly, to what extent would boys and girls of different grade levels empathize, sympathize, or distance themselves from characters' emotions and cognitive perspectives? Given the nature of children's minds and their socialized experiences and a play whose female protagonists demonstrate free emotional expression both visually and verbally, I expected older girls to empathize more than younger boys.2

A Play About Emotional Expression

Crying to Laugh (Pleurer pour rire) was written for children ages five to eight by Marcel Sabourin and translated into English by John Van Burek. 3 For the present study, I directed the first U.S. production of this québécois play at the University of Kansas Theatre for Young People in February, 1992. It was performed and designed by undergraduate students for approximately 600 spectators at each of five school performances in a large campus auditorium.

Crying to Laugh uses direct address, role-modeling, and theatrically fantastic devices to show youngsters that they should cry and get angry whenever they feel the need to release physical stress. Its story revolves around Mea (Me, the ego), a little girl who lives in a big adult world with its gigantic bed, mirror, and shower. She breaks "the fourth wall" immediately by introducing the audience to her best friend, Shado, her dog (a hand puppet). Yua (You, the superego), her smiling caretaker dressed immaculately in white, fakes his adult superiority on tall, theatrical stilts. When Shado accidently drowns in his bath (initiating conflict), Yua admonishes Mea not to cry or she won't grow up big like him (obstacle). However, Mea suffers from aches and pains until her Seluf (her Self, the id), her reflection, enters from a mirror and teaches her how to cry and get angry against Yua's rules (goal). Seluf shows Mea how stress is like balloons stuffed inside her body which must be popped (solution). When Seluf removes Yua's stilts (turning point), Mea screams at his hypocrisy (climax), cries, and releases her emotions by popping colorful balloons which fall from above (resolution). She learns that it's okay to cry and to express herself, despite grown-ups who restrict her emotions and self-expression (theme).

Scenographic effects, inspired by Daniel Castonguay's original designs (Beauchamp 1992, 16), were intended to induce audiences to imagine and enter into Mea's fantastical world from her small perspective. A huge brown bed, mirror, and muslin-draped shower were built in proportion against an eight-foot tall Yua for a large proscenium stage (40' x 31'). Black lines on the pale blue floor and raked platform helped to force a depth of perspective, and clear plastic billowing from the battens clouded Yua's sterile and stifling environment. Lighting followed Mea's moods by shifting from stark brightness in Yua's presence to dimmer light whenever Mea tried to express her inner feelings. New Age music also underscored her emotions with piano and flute themes. Seluf's yellow and orange jumpsuit, a reflection of Mea's blue and green jumpsuit, stood out from Yua's immaculately white suit. During Mea's catharsis, the stage exploded into more vibrancy with flashing, saturated lights, colored balloons and pillow feathers, and a mirror ball.

Observing Behaviors During Performances

At each school performance, I took running notes of youngsters' general behaviors from the back of the orchestra or mezzanine by observing and listening to whole group vocal responses. As audience members were seated, they marvelled at the unusually large size of the setting. During the play, musical underscoring and lighting shifts seemed to control many group behaviors and moods.

Children were especially attentive and quiet during sad moments (e.g., Shado's death and when Seluf gently urges Mea to tell her sad feelings to someone she loves), angry arguments (e.g., when Mea and Seluf fight over their differences and when Mea screams at Yua for lying), and suspenseful moments before critical discoveries (e.g., when Seluf enters from the miffor and Mea recognizes her separate persona; when Seluf raises Yua's pant leg to see his stilts, and when she removes his stilts from under the bed). They giggled or laughed at references to "kissing" (usual triggers of nervousness or sarcasm), humorous sight gags, actors' facial and physical antics, the chase scene, and jubilant victories. Restlessness or shifting in seats occurred primarily during transitions between episodes and during explanatory conversations when actors' energies dropped. Spontaneous applause and enthusiastic screaming broke out during Mea's exuberant emotional release when balloons fell and the mirror ball cast "balloons" of moving lights around the auditorium.

Actors reported feeling invigorated and charged by these overt responses as they adjusted their energies in tune with noise levels. Aural behaviors matched actors' emotional rhythms and concentrated energies moment by moment as intended by respective actions. The play's visualized metaphors and explicit thematic dialogue appeared to communicate successfully. I was thrilled crying through tears of joy! Surely everyone must have empathized with Mea's experience! But children's verbal responses in subsequent interviews would challenge my intuitive interpretations of the extent to which "everyone" empathized.

Procedures for the Study

For the actual study, 33 first graders (mean age 7), 28 third graders (mean age 9), and 27 fifth graders (mean age 11) (44 boys and 44 girls) participated from three schools in various socio-economic class neighborhoods. Twelve to fifteen days before theatre attendance, they answered a 35-item questionnaire by circling "yes" or "no" to statements they felt were "like me" or "not like me" (e.g., "Seeing someone who is crying makes me feel like crying" and "When I am acting out a story in drama, I feel like I am the character"). This commonly used Empathy Index (Bryant) and the Self-Evaluation of Drama Skills (Wright) measured respective predispositions to see whether personal traits would relate to their emotional recall of the play.

One day after theatre attendance, children were interviewed individually for fifteen minutes at their respective schools. They were asked to recall freely "what the play was about" and the play's theme (i.e., "what Mea learned"). First graders were encouraged to simulate the play's actions with three photographed character "dolls" and proportional scenic models of the bed, shower, and mirror, made available to all children. From long-shot photo prompts and referential facial diagrams of basic emotions, they were asked how they felt during six situations (i.e., OK/neutral, happy, sad, afraid, angry, surprised, or disgusted), how much ("a lot" or "a little"), and what made them feel that way (i.e., attributions). These chronologically ordered situations were selected from what actors reported as their six most intensely felt emotions during the play. Next, children were asked how targeted characters felt in these situations, how much, and how they knew these emotions to determine salient visual and verbal signs. They also reported their uses of imagination and whether and how they were like each character to determine perceived similarities or identification.

Analyzing Emotional Responses

Transcriptions from audiotaped interviews were coded by three raters for reliability which ranged from 89% to 100%.4 Responses were scored by the presence and frequency of core categories or themes which emerged from the data for descriptive statistical analysis (Strauss). For example, perceived similarities with characters were scored by the number of various physical, behavioral, emotional, and social traits mentioned.

Attributions for emotions were scored once per situation as either empathy, sympathy, distancing, or no attributions, and then added across the six situations to create respective scores. Using generally accepted definitions from psychology, empathy and sympathy represented reasons recalled from inside the characters' Perspectives, while distancing referred to personal reasons made outside the play's fiction. No attributions indicated possibly contagious emotions, but the child repeated the situation as stated (e.g., "I felt sad because Mea's dog died") or was unable to verbalize reasons for his or her feelings.

Specifically, empathy was defined as identical matches with protagonists' emotions and spoken reasons for each of the six situations. For example, when Mea's dog drowned, "I felt sad because she lost her best friend"; or, when Mea saw Yua's stilts, "I was mad because she found out that Yua lied to her." Sympathy was defined as plausible emotions with reasons different from the targeted characters as the following examples demonstrate:

Personal distress - "I felt sad because Yua didn't care about Mea's feelings."

Projection - "If someone threw my dog away, I would be mad."

Emotional contagion - "I felt happy because Mea was happy having fun jumping on the bed."

Role-taking - "If I were Mea and my dog died, I'd be sad."

Distancing was also defined as plausible emotions, but the child focused on him or herself, the staged event, or outside knowledge as in these examples:

Performance signs - "I felt happy because I laughed at her funny face" or"I felt OK because I knew it was a fake dog."

Script expectations - "I was surprised because I didn't think Yua was on stilts" or "I felt OK because I knew Seluf would come out of the mirror eventually."

Personal associations or experiences - "I was happy because I like jumping on beds" or "I felt sad when my pet died."

Moral prescriptions - "I was mad because I thought Yua should have buried Shado or taken him to the vet."

Summarizing Results

Results confirmed other empathy studies by indicating how gender and grade level differences were based on cognitive developmental strategies, socialization, and individual expectations. Though girls had higher scores than boys on the Empathy and Drama Indices, which correlated highly especially with imaginal variables, there were no significant relationships between these scores and attributions or perceived similarities. For example, favorable evaluations of drama skills did not relate directly to uses of role-taking in attributions. In other words, individual personal traits, as measured by these indices, had little bearing on types of emotional and cognitive responses.

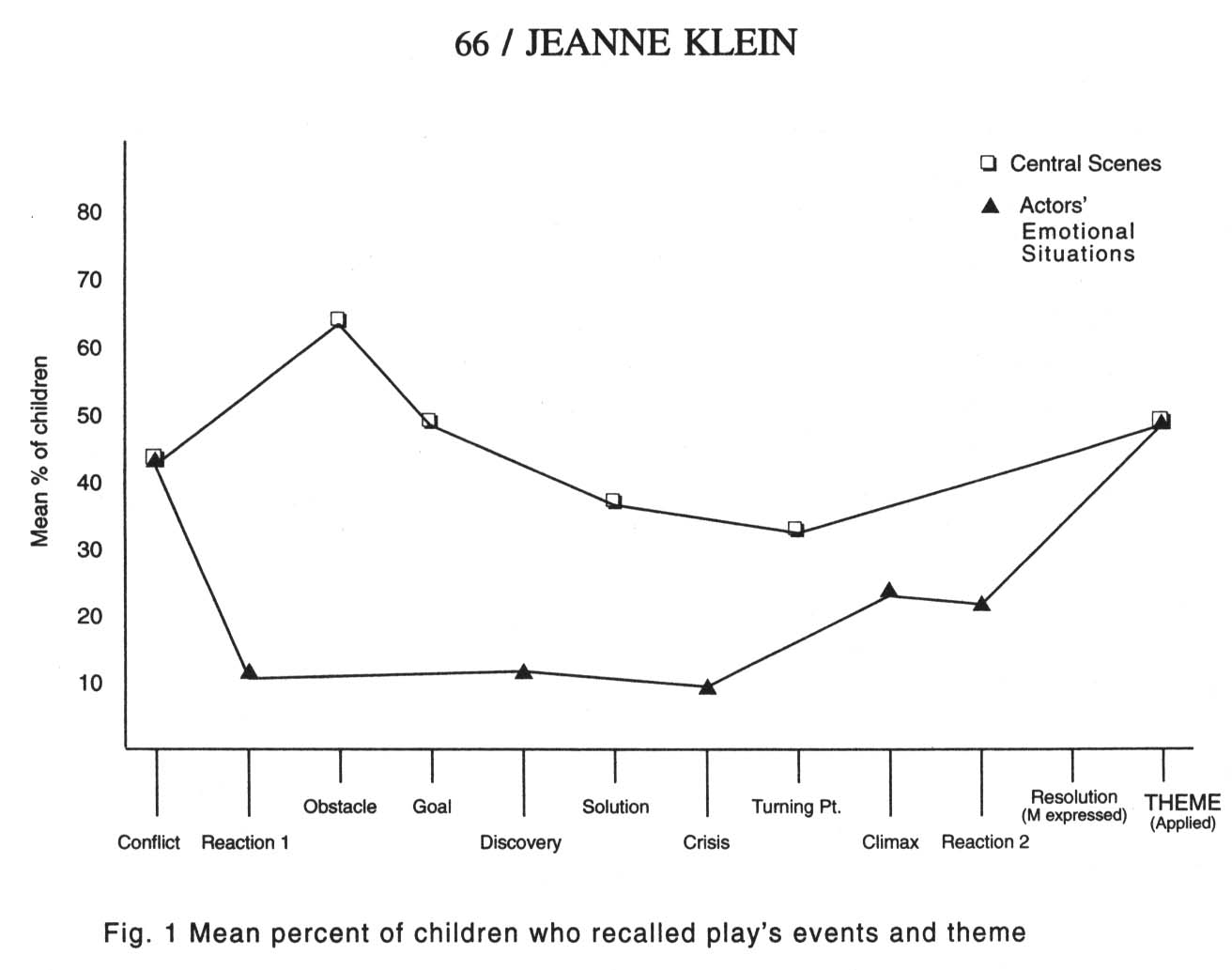

Most children (85%) identified actors' emotions accurately with high intensities by relying on characters' visual and aural behaviors (53%) more than on their verbalized thoughts (37%). However, most recalled the play's central scenes and theme more than the actors' most emotional situations (see Figure 1). In other words, comprehension of the play's central dramatic events was more memorable than the actors' interpretations of their most intensely felt experiences. Most children (60% to 74%) said they imagined and perceived themselves as the protagonists, especially Seluf, in this dramatic situation; though a few boys (27%) who imagined or perceived themselves as Yua tended to distance themselves most often.

Display large image of Figure 1

The special effects and spectacle of the play's resolution may have distracted young children from identifying the central theme. Just over half (57%) of the first graders (and 71% of the third graders) recalled or inferred either literally, that Mea learned to express her feelings (27%), or abstractly that "It's OK to cry" (30%). Fifth graders (93%) inferred and applied the play's theme (e.g., "You should express your feelings") more than younger children in that they recalled more central actions than incidental activities. Children relied on visual and verbal signs equally when inferring what Mea learned "because Seluf taught Mea to cry."

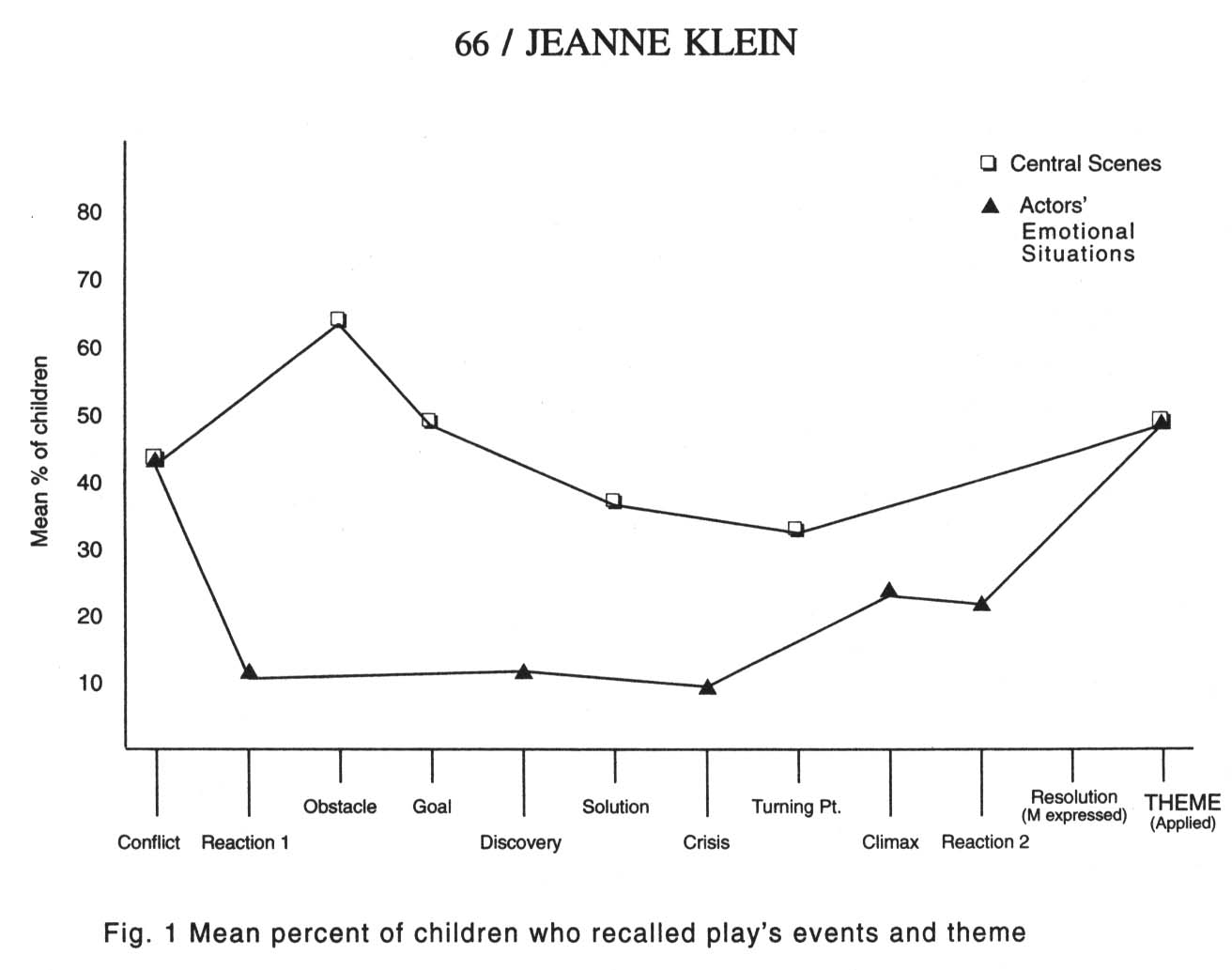

As shown in Figure 2, most children (88%) sympathized and distanced themselves through objective perspectives, and only half (53%) empathized by feeling and thinking the protagonists' or actresses' subjective perspectives. Most sympathized for Mea during her crisis (42%) (when Seluf was trapped in the mirror) by directing their anger against Yua's unjust treatment of Seluf, and during the climax (48%) (when Mea saw Yua's stilts) when they felt happy for Mea's belief in Seluf's truth by anticipating the "happy ending." They reported sympathetic personal distress or contagious sadness when Shado died (conflict) (35%) and when Yua mistreated Shado (reaction 1) (36%), though Shado's death also triggered recall of similar personal experiences or associations because children liked dogs and disliked death (33%).

Display large image of Figure 2

Yua's unjust treatment of Shado (42%) and Seluf (23%) triggered distancing by inducing anger and moral prescriptions about what he should or shouldn't have done from social norms. Few children made moral judgments, though they were less likely to sympathize if they focused on Yua's immoral actions. Seluf's discovery of Yua's stilts caused the most distancing (57%) as children's expectations were met or thwarted by this surprising theatrical use of his stilts as an integral plot device. Some were jarred out of their fictive representational frameworks by this new knowledge, while others felt "OK" because they already knew about this obvious convention from their presentational frameworks here and when Mea saw his stilts (climax) (31 %).

Empathy increased during the play as viewers grew familiar and more emotionally involved with Mea's drama. Toward the end of the play, children empathized with Mea during her crisis (22%) by sharing the sad loss of her best friend trapped within the mirror; and during the climax (17%) when they shared her indignation over Yua's deception. Attributions converged during reaction 2 or the thematic resolution (when Mea jumped on the bed to express her feelings) as her jubilant victory induced the most empathy (28%) of all situations and much projected sympathy (31 %) for her pleasurable experience (e.g., "Because Mea was having fun making a mess and not listening to Yua anymore"). However, this spectacle also diverted attention and distanced viewers (36%) as they associated their personal desires (e.g., "I like jumping on beds and popping balloons"). A few wanted to break the fourth wall entirely by participating with Mea directly on stage.

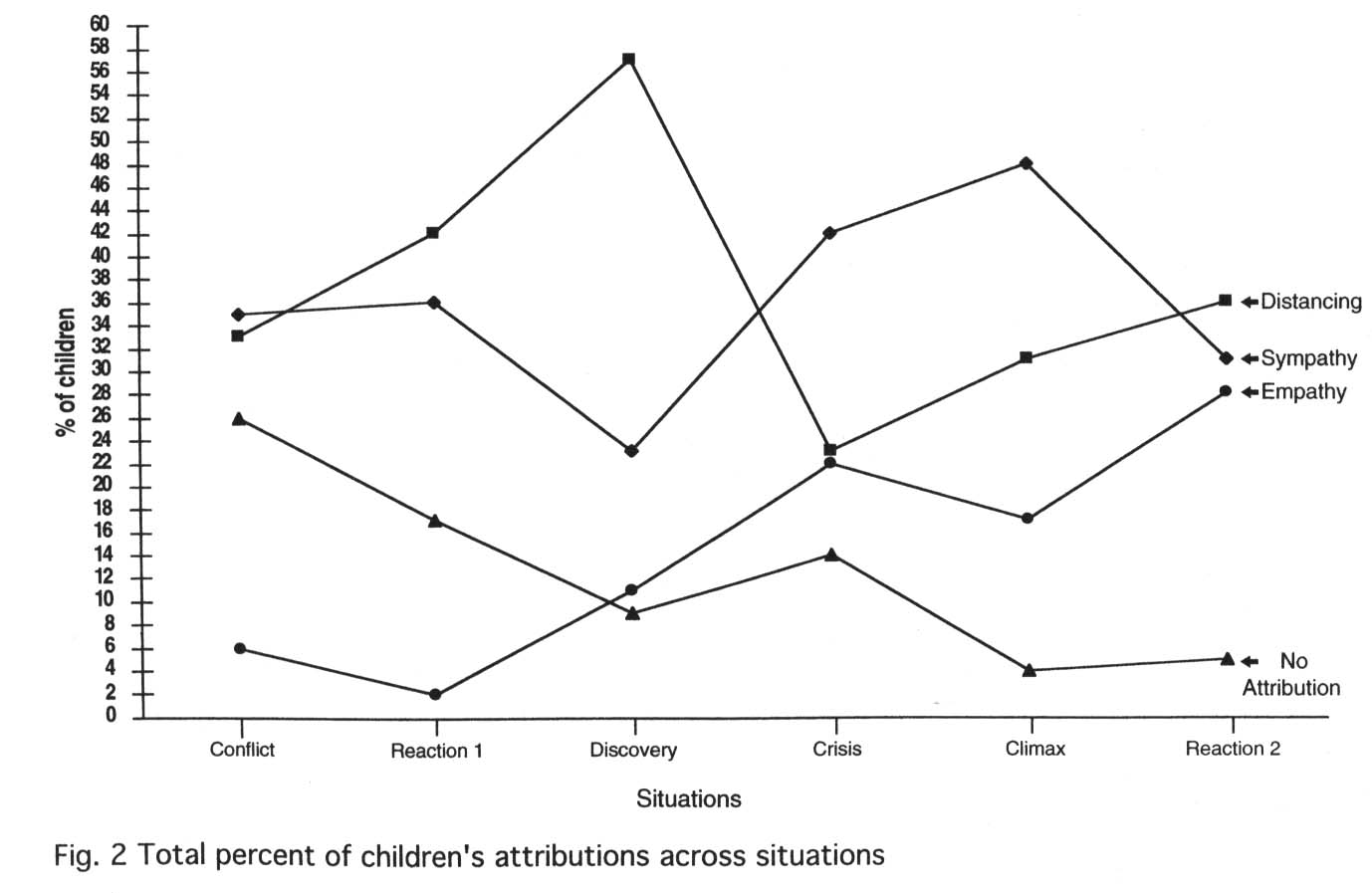

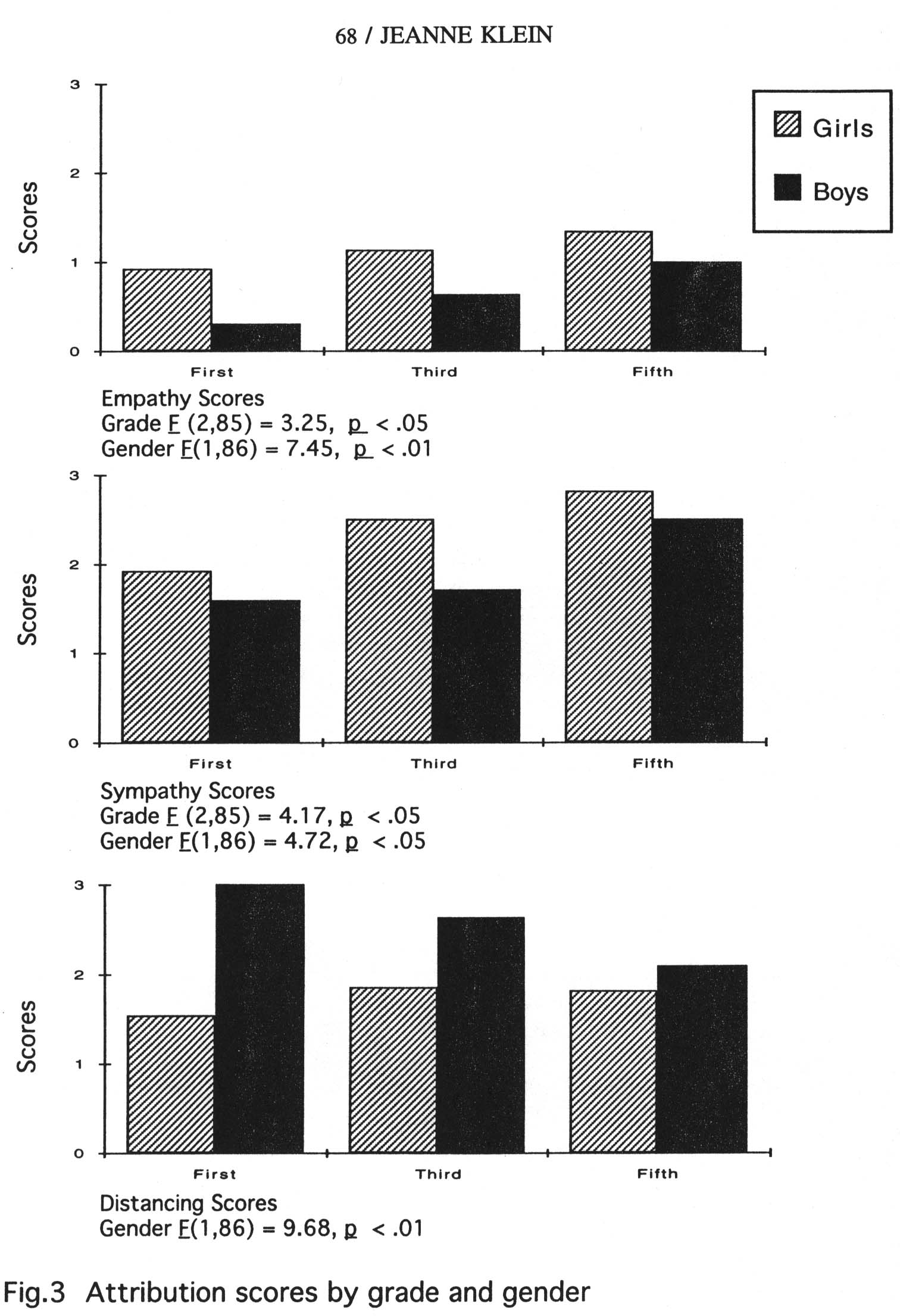

Figure 3 summarizes attribution scores to show how significant age and gender differences interacted with actors' performances across the six situations. As expected, girls and older children more than boys and younger children empathized and sympathized by sustaining characters' perspectives within a representational framework. Such children were more likely to perceive themselves ideally as Seluf by comparing themselves against her emotional traits. Fifth grade girls admitted not expressing their feelings like Mea more than all boys combined. Similarly, more girls (75%) recalled the play's obstacle (not to cry) more frequently than boys (50%), and they reported feeling sad more intensely for half of the situations. In contrast, first and third grade boys, in particular, tended to distance themselves more frequently than girls, primarily by associating staged activities with personal desires and by holding expectations about dramatic situations and Yua's stilts. Third graders marked the developmental gender shift as first grade girls empathized nearly as often as fifth grade boys.

Display large image of Figure 3

Interpreting Results

These results may be explained by performance and social cognitive factors which interacted interdependently to generate high sympathy and distancing and low empathy. If empathy determines subsequent helping behaviors, then empathetic tendencies and sympathetic strategies may have been thwarted and enhanced respectively by audiences' conventional inability to assist Mea and Seluf directly on stage in this non-participatory production. The uses of direct address and "strange," non-realistic objects (e.g., dog puppet and stilts) may have weakened empathy further by keeping audience members aware of watching live actors rather than fictive characters. The play's surprising events, staged activities, and its expressionistic use of stilts, song, and spectacle, combined with the actors' humorous exhibition of skills, triggered personal expectations or associations from social experience and knowledge.

Gender and age differences resulted from social cognitive factors, perhaps because adults tend to allow girls and younger children to cry more often than boys and older children who are socialized to suppress their emotions and to control themselves. First graders may have had less need to focus on the causes and consequences of Mea's crying behaviors. Though many first and third grade boys did find that "It's OK to cry," girls were more likely to tell an interviewer about their sad feelings to release tension, just as Seluf advised Mea. The inability to express emotions freely and the loss and gain of female friendship figured highly in older girls' attributions.

As found in my previous studies, children described or interpreted literal actions rather than grasping the symbolic significance behind theatrical signs, even though Crying to Laugh was written and designed from intrinsic metaphors. Few children applied the figurative meanings behind characters' names and relationships to their own emotional lives. Few recalled how the balloons signified Mea's physical stress, though Seluf demonstrated this metaphor explicitly; and no one reported that Mea's balloon popping during the resolution signified her emotional release. Granted, interview questions may not have addressed such symbolic concepts directly, but these findings highlight the ongoing need to question young audiences' metaphoric knowledge of theatrical conventions.

In sum, Crying to Laugh reinforced what children already knew about emotional expression by age and gender, contrary to adult assumptions that youngsters need to learn the physical importance of crying. True to the play's ironic title, children laughed and enjoyed themselves very much-without crying (or trying to), unlike some adults. They were entertained, indeed, but one can only speculate through blind faith or cynical doubt whether they will recall the ideas of this performance when they feel the future need to cry.

Implications for Theatre Producers and Educators

Though presentational performances trigger distancing effects, young audiences continue to sympathize for characters from objective perspectives within assumed or expected representational frameworks. Children certainly care and feel compassion for characters, but young ones often distance themselves easily from characters' perspectives when dramatic activities, theatrical signs, and "awesome" special effects divert attention away from metaphoric themes and provoke superficial pleasures. Because primary grade children focus on physical appearances and sometimes laugh at rather than with actors' emotions, directors need to ensure that conceptual themes are fully integrated with characters' actions, dialogue, and scenography so that actors' behaviors and spectacular effects do not overwhelm or distract youngsters from underlying meanings. Pacing abstract ideas in tune with the slower speed of young minds also ensures better communication while breaking the myth that "fast actions hold weak attention spans."

There are no artistic formulas for creating meaningful productions for young audiences. Each play and production holds its own unique challenges in communicating themes visually to young children who are learning how to focus on characters' actions, thoughts, and emotions through new and unfamiliar theatrical conventions. Finding familiar behaviors and favorite objects is part of the joy youngsters feel with each new theatre experience, but making children laugh at actors' behaviors for the sake of "easy" entertainment is not the primary goal of theatre. Young audiences deserve to be entertained by plays which confront rather than deny the seriousness of their personal problems created by adults.

Does Crying to Laugh reverberate more strongly to adolescents and adults, especially parents and teachers, who have lived the stressful, internal consequences of not crying in a society that perceives crying as a sign of weakness? Contrary to artistic intentions, the play's scenographic design may have inadvertently induced adults more than children to enter into its ageist significance. As one woman confirmed, "this production was meant for grown-ups to see how at times they as big people make children feel small."5 Crying to Laugh may be part of a growing trend to produce theatre for "family" audiences of mixed age groups rather than from children's social cognitive perspectives. While plays for all age groups enhance a sense of community, key differences exist between plays which empathize with children's lives and those which project adults' childhood fantasies sympathetically. Inducing young audiences to view expressionistic plays from the protagonist's perspective challenges artists to invent further techniques which stretch children's minds.

Young audiences may also represent "novice" adult audiences who are not educated formally in theatre's symbolic conventions by frequent attendance. The need for theatre education at all elementary, secondary, and university levels serves to remind educators that theatre appreciation must be nurtured consistently over time. Because young boys focus more on performance features and older girls focus more on character relationships, these two essential modes of comprehension need to be integrated in elementary theatre curricula. Teachers might stress how visual signs signify aural texts as crucial thematic metaphors by encouraging students to search for underlying subtexts and multiple meanings beneath the surface appearance of actors' actions and visual designs. Paradoxically, teaching audiences to analyze performance texts may encourage more objective viewing and weaken empathetic tendencies unless spectators suspend and withhold critical analyses during performances.

Audience reception studies which test artistic intentions directly against spectators' meaning-making strategies and cultural expectations can inform performance theories about the function of emotions in theatre. By empathizing with children through their developmental minds, artists may enhance meaningful experiences which encourage young audiences to return to theatre as adults. In these ways, structuralist studies grounded firmly in cognitive science methods and contextualized artistic practices may illuminate theatre's emotional effects with more realistic and practically realized cultural benefits.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank participating children, parents, teachers, and administrators in the Lawrence Public Schools for their cooperation; research assistants who interviewed children and coded data; and the cast, crew, staff, and faculty of Kansas University Theatre.

NOTES

1 For more complete details about methods and results, see Jeanne M. Klein, "The Nature of

Empathy in Theatre: Crying to Laugh," a 407-page technical report submitted to the ERIC

Document Reproduction Service in Urbana, IL.

Return to article

2 Unfortunately, I was not able to test another hypothesis that boys might empathize with a male

protagonist as much as girls because it was not possible to cast a short male actor from the

largely female talent pool.

Return to article

3 Winner of the 1982 Canadian Chalmers Children's Play Award, Pleurer pour rire was first

produced by Le Théâtre de la Marmaille (now Les Deux Mondes) in Montreal in 1981. La

Marmaille toured the play extensively in French and English throughout Canada, Europe,

Australia, and the United States until 1988 when rights were released to other producing

groups (Beauchamp 1985, 256; Klein 1986).

Return to article

4 Reliability means how often different raters consistently agree that a respondent's answer meets

the definitions for a particular category. For example, if two people agree on one coding

category but a third person disagrees, then reliability for that respondent's answer would be

66%.

Return to article

5 Twelve university students (eight women and four men) from a children and drama course

answered an analogous questionnaire for this study. For the most part, they responded much

like fifth graders. However, unlike children, they reported feeling characters' emotions less

intensely, and they sympathized and distanced themselves more often with adult expectations

about this children's play. Only half the women and one man empathized with Mea, significantly

less than fifth graders. Most perceived themselves "a little" like Mea because all the men and

half the women reported that they did not express their emotions freely. All adults perceived

they were like Seluf and most believed they were not like Yua.

Return to article

WORKS CITED

Beauchamp, Hélène. Le théâtre pour enfants au Québec: 1950-1980. LaSalle, PQ: Hurtubise HMH, 1985.

"Forms and Functions of Scenography: Theatre Productions for Young Audiences in Quebec." Canadian Theatre Review, 70 (1992): 15-19.

Bennett, Susan. Theatre Audiences: A Theory of Production and Reception. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Bryant, Brenda K. "An Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents." Child Development 53 (1982): 413-425.

Damon, William, and Daniel Hart. Self-Understanding in Childhood and Adolescence. New York: Cambridge UP, 1988.

Deldime, Roger. L'enfant au théâtre. Bruxelles: Cahier JEB, 1978.

Deldime, Roger, and Jeanne Pigeon. "The Memory of the Young Audience." Trans. Robert Anderson. Youth Theatre Journal 4.2 (1989): 3-8. (Originally, "La mémoire du jeune spectateur," in Jeu 46 (1988): 88-100.)

Dorr, Aimée. "No Shortcuts to Judging Reality." Children's Understanding of Television. Eds. Jennings Bryant and Daniel R. Anderson. New York: Academic, 1983. 199-220.

Eisenberg, Nancy. The Caring Child. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992.

Eisenberg, Nancy, and Janet Strayer, eds. Empathy and Its Development. New York: Cambridge UP, 1987.

Flavell, John H., Patricia H. Miller, and Scott A. Miller. Cognitive Development. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993.

Hagnell, Viveka. "Children as Spectators: Audience Research in Children's Theatre." New Directions in Audience Research. Ed. Willmar Sauter. Utrecht: Instituut voor Theaterwetenschap and ICRAR, 1988. 53-62.

Hoffman, Martin. "Interaction of Affect and Cognition in Empathy." Emotions, Cognition, and Behavior. Eds. Carroll Izard, Jerome Kagan, and Robert Zajonc. New York: Cambridge UP, 1984. 103-131.

Klein, Jeanne. "Applying Research to Artistic Practices: This Is Not a Pipe Dream." Youth Theatre Journal 7.3 (1993): 13-17.

_______. "Children's Processing of Theatre as a Function of Verbal and Visual Recall." Youth Theatre Journal 2.1 (1987): 9-13.

________. "'Getting Into the Head' of the Children's Theatre Actor." New England Theatre Journal 3.1 (1992): 97-104.

________. "Le Théâtre de la Marmaille: A Québécois Collective Founded on Research." Children's Theatre Review 35.1 (1986): 3-8.

Klein, Jeanne, and Marguerite Fitch. "First Grade Children's Comprehension of Noodle Doodle Box." Youth Theatre Journal 5.2 (1990): 7-13.

________. "Third Grade Children's Verbal and Visual Recall of Monkey, Monkey." Youth Theatre Journal 4.2 (1989): 9-15.

Sabourin, Marcel. Pleurer pour rire (Crying to Laugh). Montréal: VLB Éditeur, 1980.

Schoemnakers, Henri. "Aesthetic and Aestheticised Emotions in Theatrical Situations." Performance Theory, Reception and Audience Research. Ed. Henri Schoenmakers. Amsterdam: Tijdschrift voor Theaterwetenschap and ICRAR, 1992. 3958.

________. "Pity for Nobody: Identifactory Processes with Fictional Characters During the Reception of Theatrical Products." Revue Internationale de Sociologie du Théâtre (1993): 33-43.

________. "To Be, Wanting To Be, Forced To Be: Identification Processes in Theatrical Situations." New Directions in Audience Research. Ed. Willmar Sauter. Utrecht: Tijdschrift voor Theaterwetenschap and ICRAR, 1988. 138-163.

Strauss, Anselm L. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. New York: Cambridge UP, 1987.

Strayer, Janet. "Children's Concordant Emotions and Cognitions in Response to Observed Emotions." Child Development 64 (1993): 188-201.

Winner, Ellen. The Point of Words: Children's Understanding of Metaphor and Irony. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1988.

Wright, Lin. "Grade Three Self-Evaluations of Drama." K-6 Drama/Theatre Curriculum. National Arts Education Research Center. Tempe: Arizona State University, 1990.