Photo: Jupiter Theatre's Founders

RICHARD PARTINGTON

The Jupiter Theatre (1951-54) was founded by actors Lorne Greene and John Drainie, and writer Len Peterson, who sought to establish a fully professional company in Toronto dedicated to the encouragement of Canadian playwrights, and the "emergence of a truly Canadian voice in the theatre." Their ideals were shared by the nationalist local radio critic Nathan Cohen. Of the fifteen plays produced during Jupiter's brief but significant lifetime four were Canadian-written: Socrates and The Blood Is Strong by Lister Sinclair, The Money Makers by Ted Allan and Blue Is for Mourning by Nathan Cohen. I will attempt to assess Jupiter's contribution to the development of that "Canadian voice" by looking at the plays themselves, their authors and, as far as can be deduced, their theatrical presentation by Jupiter. I shall measure my own response to the plays as texts against the responses of the contemporary Toronto critics, principally Herbert Whittaker of the Globe and Mail and Nathan Cohen on CJBC Views the Shows, a perusal of whose reviews formed the bulk of my investigation. Conversations with Jupiter alumni have helped to place these responses in a meaningful historic context. I shall also consider the subsequent contributions, if any, of the three playwrights to the Canadian theatre.

Le Jupiter Theatre (1951-1954), fondé par les comédiens Lorne Greene et John Drainie et l'écrivain Len Peterson, visait létablissement d'un théâtre entièrement professionnel à Toronto voué à l'encouragement des dramaturges canadiens et à « 1'avènement d'une voix véritablement canadienne dans le milieu théâtral.» Leurs idées étaient partagées par le critique radiophonique nationaliste Nathan Cohen. Des quinze pièces montées pendant l'histoire courte mais significative du Jupiter, quatre pièces étaient écrites par des Canadiens: Socrates et The Blood Is Strong de Lister Sinclair, The Money Makers de Ted Allan et Blue Is for Mourning de Nathan Cohen. J'analyserai la contribution du Jupiter à la création de cette « voix canadienne» par un examen des textes énumérés, leurs dramaturges et, dans la mesure du possible, les productions. Je comparerai mes impressions de ces textes avec celles des critiques torontois de l'époque, plus spécifiquement Herbert Whittaker du Globe and Mail et Nathan Cohen de CJBC Views the Shows dont les écrits composent la partie la plus importante de mon corpus. Des entrevues avec des anciens membres de Jupiter ont aussi aidé à placer mes impressions dans un contexte historique valable. J'évaluerai ensuite les contributions subséquentes, s'il y en a eu, de ces trois dramaturges au théâtre canadien (de langue anglaise).

Introduction

Theatre in English Canada began a slow but steady move towards professionalism during a general upsurge of cultural activity after the Second World War. Certain theatre practitioners, some from the amateur world, others from University groups and programs, still others already professionalized to some degree by their employment in the field of radio drama, sought to establish the conditions whereby they and their colleagues could earn, or at least attempt to earn, a living through their work. To this end Dora Mavor Moore, for example, set up her New Play Society in Toronto (1946), and Donald and Murray Davis inaugurated the Straw Hat Players in Muskoka (1948), one of several professional or semi-professional summer stock companies that came into being at the time. Later, while the Stratford Festival was rapidly establishing itself as a flagship professional operation (1953), the Davises opened the Crest Theatre, a comparatively long-lived Toronto company (1954-1966) which nurtured the careers of many important Canadian theatre practitioners and, it could be argued, provided an impetus for the many other regional professional theatres which were to spring up across Canada during the 1950s and 1960s.

As a concomitant ideal, the professionalization of theatre in this country strengthened a desire for its essential Canadianization, its development of writers, directors, actors and designers expressing indigenous sensibilities rather than those, say, of London or New York. The playwright, needless to say, represented a key figure in the equation. True, the amateur Dominion Drama Festival (1932-1978) annually encouraged the production of new works, though largely, until 1950, in the form of one-act plays, and amateur institutions such as the Toronto Arts and Letters Club, the Ottawa Drama League, the Peterborough Little Theatre, the Montreal Repertory Theatre and Toronto's venerable Hart House had indeed given voice over the years to such diverse and prolific playwrights as Merrill Denison, John Coulter, Herman Voaden, Gwen Pharis Ringwood and Robertson Davies. But not until Dora Moore's proto-professional New Play Society (NPS) mounted five full length Canadian plays in their 1949-50 season was the possibility strongly reinforced that indigenous playwrights could claim equal stage time with their international counterparts, and that a professional arena was the proper place for this to happen.

Though the NPS was never to mount another such banner season, their extraordinary feat challenged others of the dramatic arts sector to do their own part to propel the Canadian professional theatre into a viable next phase. Responses emerged from the world of CBC radio, long a developer and producer of Canadian scripts: one from a critic in the form of a nationalist diatribe, another, a short-lived, little-remembered theatre company known as the Jupiter.(1)

The Birth of the Jupiter Theatre

On June 17, 1951, over the air-waves of Toronto radio station CJBC, critic Nathan Cohen, even more enraged and depressed about the state of Toronto theatre than usual, thundered a blunt denunciation:

For us to be deprived of the great dramatic offerings of a dozen European countries while we are subjected to the commercial American inanities that infest the play catalogue around here is to me the most outrageous kind of blasphemy.

Decrying those forces he saw to be preventing the development of a local, professional "dramatic movement of substance and virility," such as the proliferation of "third-rate" movies, lack of rehearsal and performance spaces, the "myopia" of business and funding bodies, and "amateur organizations that view real drama and professional theatre with a hatred that verges on the psychopathic," he nevertheless included among these "stultifying pressures" the inertia, despair and lack of sincere commitment of the would-be professionals themselves. To these he issued what amounted to a ringing challenge:

What we need in Toronto in the realm of drama are a few tenacious persons of high standards and firm convictions, imbued with a knowledge of what they want and a determination to succeed, no matter how adverse the conditions. Do we have any such supermen? ... it's time for them to overcome their shyness and come out of hiding. There is urgent need of them. (qtd. in Edmonstone 195-7)

A scant three months later, in actor John Drainie's living room, Jupiter Theatre Inc. was born: "a non-profit organization chartered by the Canadian government to establish a permanent Canadian professional theatre."(2)

Photo: Jupiter Theatre's Founders

While there is no evidence to suggest that the Jupiter's founders were responding to Cohen's provocative challenge, the theatre's initial seven-member board were sufficiently well-connected to make such an enterprise work.(3) They included: chairman John Drainie, then arguably Canada's foremost radio actor; Len Peterson, prolific script-writer during radio drama's Golden Age, author of the acclaimed Burlap Bags(4) Lorne Greene, wartime news broadcaster, founder of the Academy of Radio and Television Arts (Toronto's only professional training school of the time); the character actor Paul Kligman, alumnus of many productions; writer George Robertson; business and entertainment executive Edna Slatter, Lome Greene's assistant at the Academy; and Glen Frankfurter from the world of advertising.

Drainie, Peterson and Frankfurter formed Jupiter's core directorate, responsible for securing directors and, in consultation with the latter, casting the plays, whereas the entire board was collectively responsible for play selection and sharing various production and administrative duties. Drainie, for example, would often take the job of writing the program notes and press releases, but he also involved himself with sets, costumes, lights and the endless task of raising money (Drainie 158).(5)

Funds were scarce from the beginning. Two thousand dollars in "seed money" was raised by $ 100 donations from all the board members, and from the "Friends of Jupiter," a group which would eventually include actors Budd Knapp and Bernard Cowan, director Esse Ljungh, theatre and media musicians Lucio Agostini, Lou Applebaum and Howard Cable, philanthropists Mrs. Arthur Gottlieb and Mrs. H.R. Jackman, and the poet E.J. Pratt.(6) According to a note appearing in all the Jupiter programs this select group of people would "endeavour to promote a mature stage in Canada," and audience members were invited to join them in their "desire to see a permanent and established Canadian professional theatre."

Jupiter, moreover, was to be a theatre devoted to the promotion and production of Canadian plays. While he deplored in his June 17 broadcast a dearth of the "great dramatic offerings of a dozen European countries," Nathan Cohen emphasized that the "basic need" was for Canadian plays, 11 preferably with Canadian themes and settings . . . but at least by Canadians." Citing Joseph Schull, Lister Sinclair and John Coulter as local dramatists worthy of production, he continued in an extravagantly hopeful vein: "We need to have as many plays by Canadians put on as possible." Allowing, nevertheless, that some of these many plays might be risky or even bad, he made a cogent point when he declared:

The playwright, the crucial member of the drama, is the most neglected in the country. As long as he is blocked, stifled, and not allowed to be productive, the Canadian Theatre will be insignificant. (qtd. in Edmonstone 198)

It is with the same nationalistic aspirations for theatre in this country, stated perhaps less vehemently than the irascible Cohen, that Jupiter's founders enunciated the first of their principal aims: "To promote the production of plays by Canadian writers, to assist the emergence of a truly Canadian voice in the theatre" (qtd. in Kotyshyn 159).

Of the fifteen plays which Jupiter offered during its three seasons of existence (see Appendix A)-more aptly described as one full season (1952-53) sandwiched between two half-seasons (1951-52 and 1953-54) -- four were Canadian-written: Lister Sinclair's Socrates and The Blood Is Strong, Ted Allan's The Money Makers and Nathan Cohen's own Blue Is for Mourning. Two more were slated for the second half of the 1953-54 season -- Len Peterson's Never Shoot a Devil and another by Ted Allan, Answer to a Question -- which would have represented a relatively impressive three Canadian plays out of a projected eight for that season,(7) but Jupiter, alas, was forced to suspend operations before it could bring them into production.

Socrates

By the time Jupiter was assembling its inaugural season Lister Sinclair was an important and well-known contributor to Andrew Allan's Stage series on CBC radio (1944-55), both as an actor and as a writer. A handful of his works had been published in A Play on Words, one of the few such collections of Canadian radio scripts in existence. Since the early 1940s CBC had broadcast several thousand radio dramas, some from the international repertoire, classic and modem; but many, perhaps half, were original Canadian scripts. Socrates had been produced twice on the Stage program in February 1947 and January 1948.(8) Given its resultant level of polish and proven track-record, it is not surprising that of the more than a dozen Canadian plays apparently submitted to Jupiter for consideration Socrates was chosen to be the first homegrown offering. That it was the sole play deemed of sufficiently high calibre to "warrant production" is explained by the play selection policy laid out in the Jupiter's first press release, September 29, 1951:

Jupiter Theatre doesn't intend to produce plays just because they are by Canadians. Every play, Canadian or foreign, must meet a certain high standard, and we try to judge every play on the same basis. in this way, we are able to place our production of Canadian plays alongside the finest from any other country, without apology. We feel that's the only way Canadian playwrights will reach a level comparable with the world's best-and we're confident that if the writers know their plays will be well produced, that day isn't too far away.(9)

Jupiter placed Socrates, without apology, alongside Jean Paul Sartre's Crime of Passion, Dalton Trumbo's comedy The Biggest Thief in Town, and Charles Laughton's adaptation of Galileo by Bertolt Brecht-which launched the theatre on December 14, 195 1.(10)

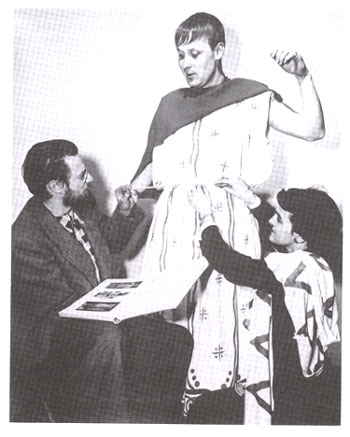

Photo: Socrates. A Poetry Contest

Socrates, which Sinclair derived from the writings of Plato and Xenephon, could be said to represent his version of Brecht's Galileo: a many-charactered dramatic exploration of an exemplary historic figure in conflict with authorities and the established order, a theme which accorded well with Jupiter's image of itself.'(11) The play charts the events of the last few days of Socrates' life: a conservative faction, in league with Athenian authorities, conspires to entrap, arrest, try and condemn him to death for sedition and the corruption of youth, while a group of his friends attempts to spirit him away from the danger. Socrates refuses to escape, claiming flight to be a weaker option than dying for his principles. Of a more centrist leaning than Brecht's piece, the play extols the virtues of innocence, purity, truth, justice and beauty (Socrates 91) without necessarily reducing itself to inconsequential platitudes:

Socrates: ... we won't think of life and family and property first, and justice next, if ever; but of justice first and always. (88)

As Sinclair's program notes reveal, Socrates is very much a product of its era, bearing an implicit condemnation of the Cold War's "two great rival orthodoxies." He has also pointed out a vein of anti-McCarthyism running throughout (telephone conversation July 21, 1996). A certain virtuosity of poetic-dramatic diction, moreover, firmly locates the play in the age of Christopher Fry, then the leading British dramatist and a favourite with Toronto audiences.(12) Poetry and anti-McCarthyism combine in the taut chorus-like passage of the first scene when Alcibiades and his friends, all supporters of Socrates, watch a flock of crows attack an owl in broad daylight, a horrifying sight emblematic of Socrates' fate at the hands of his detractors:

Alcibiades: Blood and feathers along the breeze.

He's drooping!

Lycon: Stooping!

Phaedo: Stopping!

He'll drop in the trees!

Alcibiades: Toss off a miracle, Pallas Athene!

Don't let your mascot

fall to the enemy!

Meletus: Are they ravens or rooks?

Phaedo: They're carrion crows.

Alcibiades: The scavengers' chorus! He's beaten! He's boarded!

Phaedo: They've got him.

Lycon: They'll gut him!

0 look at him bleed!

Meletus: Why can't he fight them? He's bigger than they are.

Alcibiades: Eyes made for moonlight are dazzled by daytime. In any case

now, they're pecked out by crows. (Socrates 14-15)

Directed by veteran radio producer Esse Ljungh, with sets by Larry McCance and excellent costumes by Barbara McNabb, Socrates was a huge success.(13) According to Bronwyn Drainie, almost a thousand people were turned away in the last two days of its run (February 22-March 1, 1952), enough to have filled the Museum Theatre three times over (16). Globe and Mail critic Herbert Whittaker proclaimed that Jupiter, with its production of Socrates, had at last "stirred the breath of greatness . . . This clever, even brilliant work ... reaches a note of high pathos in its final scene which is by far and away the greatest achievement of the new theatrical enterprise." Praising a cast which "bristles with excellent men,"(14) he singled out Frank Peddie as Socrates -- an "ugly old Athenian ... a gargoyle of humanity" for his skill at imparting naturalness and simplicity to the long speeches of "Socratian wisdom," and for his ability to elicit great audience sympathy (February 23, 1952).

Cohen was not so impressed. On CBJC Views the Shows (February 24, 1952)(15) he pointed out what he saw to be a few of the play's dramaturgical weaknesses: the lack of a clearly defined political source for the fears of Socrates' enemies; the fact that Socrates' talents as a teacher and "thorn" in the side of the establishment are rarely demonstrated dramatically but, rather, attested to by others; that Socrates seems more like an "absent-minded professor" than a great teacher; that his adversaries at the trial become so rapidly demoralized by him that they seem "mentally incapacitated," thus depriving the scene of an intellectually stimulating and dramatically effective argument. These criticisms are all largely justifiable. But, in citing director Esse Ljungh's skill at bringing out a "lyrical expression far beyond anything in the play itself," he suggested that the piece lacks lyricism which it demonstrably does not. (At one point, for example, there is a contest of love poetry, nicely undercut by a cynical Aristophanes.) Again at the author's expense, Cohen praised Ljungh for "unerringly" exploiting the theme of comradeship, manly affection, courage and respect, designating it as "the one theme in the play where Sinclair, the creative poet and artist, gets the upperhand on Sinclair, the peddler of shopworn cerebral cogitations." Here Cohen -- unfairly, if we are to give Socrates its full due -- dealt the erudite and intellectually accomplished playwright a nasty critical jab. This had karmic repercussions a year later when Sinclair had the opportunity to review Cohen's Blue Is for Mourning.

Nevertheless, Cohen, like Whittaker, perceived a compelling power in the play's final scene, the death of Socrates. While less convinced than the other critic of the merits of Frank Peddie's performance, complaining that his cosy manner undermined the believability of Socrates' "sagacity and impregnable valor" and that he became rather carried away by the verbal excesses of both Plato and Sinclair in the trial scene (Peddie was himself a practising lawyer), Cohen commended him for his "quiet humor" and "unblemished dignity" and thanked him for a tasteful death.

Cohen's eloquent encapsulation of the final scene's effect betrays, I think, a critic more moved by the play than he would fully admit:

It was a whole sequence of nobility and genuine spiritual exaltation. A loud shout of absolute silence announces the gadfly of Athens is gone, and the others resume life in a world that has become rudderless, bleak and appalling[ly?] cold.

It is hard to reconcile this heartfelt response with Cohen's later comment

that Jupiter, for all its first season's success, had yet to "provide us

with Canadian plays with something dramatically tangible to say" (CJBC

April 20, 1952). Later, when assessing the Toronto theatre season as a

whole, he was to deem Jupiter's second offering, Trumbo's The Biggest

Thief in Town, one of the highlights of the whole theatrical year (CJBC

July 27, 1952).(16)

According to a subsequent fund-raising letter, however,

Jupiter considered Socrates to have been their season's biggest hit (Kotyshyn

165). Cohen otherwise lauded the fledgling company for its determined professionalism,

"marked by a consciousness that theatre is a creative art," and declared

the "little theatre mentality" to be "fading [in Toronto], despite drama

festivals."

He averred that the Jupiter's founders had "every right to be proud

of their achievements, and to expect a long life for their company"-ironic,

in light of its early demise.

Photo: Socrates. Playwright Lister Sinclair (l.) And Barbara McNabb (r.)

Fit David Gardner into his costume.

The Money Makers

Jupiter's second and only full season, 1952-53, offered two Canadian plays out of a slate of seven (see Appendix A), the first being Ted Allan's The Money Makers. Allan, celebrated for his recently published biography of Dr. Norman Bethune, The Scalpel and the Sword (1952), had written scripts for radio and film. His first stage play proved to be a great success for Jupiter. Inspired by Allan's two-year experience as a writer in Hollywood, The Money Makers -- originally called The Glittering Wilderness(17) -- is a "comedy drama" (Allan, title page) about a green but ambitious young Canadian writer struggling with his conscience in the venal back-rooms of McCarthy-era Hollywood. Lured by cash and a thoroughly corrupt producer's vague promises to get his script about William Lyon Mackenzie onto the screen, Michael Bedford finds himself tricked into allowing his name to be substituted for that of a blacklisted writer in a film's credits. But, given his moral and professional outrage at this entrapment, the course of action he opts for is ethically dubious:

Bedford: I hate it here. It's a filthy jungle. But I want to get what I can out of it now that I'm here. I can't stand the idea of going back [to Canada] unless I've made a lot of money. How in God's name else would it be worth staying here, being here? (II 2 p.6)

As Cohen deftly put it, Bedford wants to have "his cake and his conscience," unlike Finch, the producer, who "knows that to get the one the other must be unconditionally abandoned" (CJBC November 16, 1952). Bedford's highly-principled wife is shocked by his corrupted integrity but is unable to persuade him to surrender the money he received improperly to the blacklisted writer, to whom in all rights it belongs. She leaves him to return to a morally saner Canada. A comment in Allan's program notes suggests that the play bears elements of a medieval Morality,(18) and, certainly, it is possible to view Finch as the Devil and Julie Bedford as Good Deeds engaging the everyman Bedford in a secular, modern-day psychomachia.

The Money Makers addresses issues of cultural difference between the United States and Canada which remain current today. Bedford, face to face with Finch's American ethnocentricity, cries "There's a big big world outside the United States and we who live there don't necessarily call your way our way" (112 p. 12), reminding one, for example, of the ongoing culture versus commerce issue at the heart of Canada's lopsided relations with the American film distribution industry. True, the play descends at times into the simplicities of "the venal Americans and the virginal Canadians," as Bronwyn Drainie puts it, but she also suggests that the work represents "perhaps the first overt exploration of the cultural tug-of-war between Canada and the United States that has obsessed so many Canadian artists and performers in the succeeding decades" (162).(19)

Directed by the New Yorker Aaron Frankel -- who likened Ted Allan to a young Clifford Odets (Whittaker November 13, 1952) -- The Money Makers starred John Drainie and Kate Reid as the writer and his wife, with Lome Greene as the devilish Paul Finch. The Toronto Star's Jack Karr felt that Greene gave the most accomplished performance of the cast, managing, as he did to convey the producer's corruption "without completely submerging a sort of raffish good fellowship" (November 15, 1952). Whittaker, however, in an aphorism worthy of Oscar Wilde, pointed out a danger inherent to the play as a result of Finch's outrageous villainy:

Mr. Allan may cry out in despair that this Evil persists, that Finch is not one whit overdrawn. But in art there is always proportion. One doublecross shocks our sense of decency; five appeal to our sense of indecency. (November 17, 1952)

While he praised Greene for creating a "richly comic and fascinating monster," a "flaming Mephisto" in the face of which John Drainie's performance as Bedford paled, Whittaker feared that the latter character's dramatic interest and moral force were undermined by our delight in the "gamut of plots, counter-plots and blackmail tricks" to which the villain resorts. This could represent a legitimate dramaturgical concern. However, from a medieval perspective again, though devils and evil-doers invariably provide rich sources entertainment, the appeal of their indecencies serves as much to warn us of the sheer attractiveness of evil. Allan equates this appeal with capitalist American rugged individualism in this exchange between the blacklisted writer and Finch:

Nicky (almost admiringly): You're without a doubt the lowest insect in a town famous for being below sea-level. You're such an unprincipled, unscrupulous, vicious, verminous low-life.

Paul (has been nodding to each word in the last sentence. Now looks grim and serious): Call me rat. Call me worm. Call me unprincipled, unscrupulous, vicious, verminous. Call me a thief. Call me a degenerate. Say I rape little children. Steal from my mother's grave. Call me anything .... (He grins now) But you can't call me unAmerican!

(Delighted with his speech Paul now pushes the candy box toward Nicky offering him candy. Nicky is amused despite himself and walks to the door but as his hand touches the door knob, Paul shouts out)

Nicky!

(Nicky turns. Paul holds up a clenched fist, grinning)

Regards to the comrades!

(Nicky stares for a moment then smiles and shakes his head in amused contemplation)

Nicky: You know what the difference between you and a Ralph Sherman is?

Paul (smiling most affectionately): Tell me.

Nicky: Sherman and his kind get to the top of the dung-heap and try to cover it up. They sprinkle it with perfume. Then they say, "This is a pile of roses." But you get there and you rub your hands in it. You revel in it. You say, "Smell it everybody, doesn't it smell wonderful?" That's why I prefer you to a Ralph Sherman. You know what you are. You know where you are, and you never try to pass off manure for essence of roses. You're almost refreshing.

Paul (sweetly): That's the sweetest thing anybody ever said to me. (starry-eyed) Topa the dung-heap ... (pointing heavenward) That's where I'm headed for. (The Money Makers 15-16.)

Cohen, too, had reservations about the leading characters' relative weights declaring Bedford to be a "stilted delineation" and Finch to be "the one member of the story with dramatic life," though he approved of both Greene's and Drainie's performances.(20) Praising director Frankel for investing the action with "the crackle of excitement," he went on to conclude that "in Ted Allan we have a new and stimulating playwright."

Cohen's opinion that the ending of The Money Makers was "quite untenable" (CJBC November 16, 1952) points, I suspect, to a certain desperation on Allan's part as to how to finish the piece.(21) He had apparently delivered to the actors an entirely rewritten third act the night before opening (Drainie, 162), which could explain Whittaker's being "haunted by the unshakeable impression that everybody was making up lines as they went along."Karr, though he too experienced this sense of collective improvisation, asserted that the audience gave a "big ovation" and called for the author. Allan, however, "for reasons unexplained"-perhaps exhaustion and terror-did not appear. The production went on to be a hit. And apart from a talky, moralizing didacticism here and there (Julie in II 2 pp. 18-19, Finch in III 3, for example) and a peculiar running gag of silent burping (which, in any case, may not have survived from the extant draft) The Money Makers reads quite well today, especially in light of a persistent American cultural hegemony. Interestingly, much of the play's most lively political discussion takes place between three women,-- unusual, I would say, for the period.(22) On December 4, 1952 The Money Makers had the honour of becoming the first Canadian stage play telecast by the newborn CBC Television.(23)

Blue Is for Mourning

Jupiter's second Canadian offering of the 1952-53 season was, unfortunately, not as successful as The Money Makers. Nathan Cohen's Blue Is for Mourning, opened on the inauspicious date of Friday the 13th of February to almost universal condemnation. According to Glen Frankfurter of the original core directorate it was the one script produced by Jupiter which had not been collectively selected (telephone conversation July 21, 1996). Apparently their business manager, Matt Saunders, after aggressively promoting Cohen's play to the board, had proceeded on his own to offer contracts to director Jerome Meyer and lead actor Donald McKee, both of New York. Peterson recalls that when members of the board read the piece they were dismayed. Given the "sudden presence" of Meyer and McKee in Toronto, however, and a promise of rewrites, they felt they had no choice but to commit themselves to it (July 22, 1996). Frankfurter remembers that the final run-through before opening depressed the board utterly, but the terms of their "tight" contract with the Museum Theatre (then run by the University of Toronto) did not allow them to cancel the show.

Photo: Blue Is for Mourning. Donald McKee (Blue), Jane Graham (Cora)

and Barbara Cummings (Sarah)

Blue Is for Mourning, set in a mining town in Cape Breton (where Cohen, incidentally, was born and raised) depicts the domestic events tangential to a local miners' strike, and is set in the home of union leader Jesse Baker. The strike has turned violent, Baker is arrested for inciting a riot, and suffers a serious head injury from a rock thrown at the police by one of his supporters. He is brought home, where, by the play's end, he dies. Baker, however, never appears on stage. His actions and predicaments are conveyed by a pair of newspapermen sent from Toronto to report on the strike. His character is revealed by these reporters and the members of his household-his mother Emma, his wife Sarah, his sister Cora and his crusty old grandfather, "Blue" McGregor. The principal actions we see are those of the characters trying to go about their daily lives while being intruded upon by the reporters, the younger of whom, Walsh, develops both a love relationship with Cora and a staunch admiration for Baker. A neighbour, old Molly Harris, provides comic relief with her wry commentary and bibulous ways-she and Emma, for example, polish off a mickey of gin under the guise of an arthritis cure. She also claims to have the gift of sight and, in an amusing sequence, reads Blue's palm.

Blue bears the burden of the play's message, forever holding up his grandson Jesse as a saintly paragon, and at several points quoting his fervent ideals verbatim:

MCGREGOR: ... that's the way it is with me, Blue. I'm climbing a mountain too. All of us spend our lives climbing mountains-but I know what's up there on top of mine. Oh, so you know? Yes-he said, calm as you please-I know. Well, tell me what's up there. Why it's as obvious as A-B-C-, Blue, I'll find happiness.

CORA: (contemptuously) Words. Words he read in a book. Big, fat stupid words that dont mean anything.

MCGREGOR: Happiness, he said, and then he said something else. Blue -- he said -- I dont like this world. Not one bit. It's a bad place-too many things wrong with it-too many people who cant afford to go to a hospital when they're sick-too many kids who wear hand-me-downs and have to share a meal not big enough for one with others-too many people who cant afford to buy a house for themselves, no matter how long they work, no matter how hard -- too many old people who dont know where their next meal will come from.

CORA: Did he mean you? He must have meant you there!

MCGREGOR: -- too many people who havent even saved enough money to pay for their own funeral expenses. It's no good, Blue-he said to me. It's wrong. There's no sense to it-no need for things to be that way . (Blue Is for Mourning III 22-23)

While it is hard to fault the sentiments expressed here it is harder still to credit it as living dialogue or escape the preachiness of tone. Just as Cohen had accused Lister Sinclair of peddling "shopworn cerebral cogitations" in Socrates, Cohen could be accused of purveying shopworn socialist cogitations. More seriously, this passage demonstrates the dramaturgical problems of leaving the main character offstage: Cohen is forced to displace the action onto the eccentric, story-telling Blue, a character which, for all its colourful crankiness, remains static and narrational, unable to generate the authentic dynamics Jessy Baker as an onstage character could potentially have generated. Cohen rationalizes his choice by subtitling his play as "A Comedy of Inaction," but such comedies, it would seem, are best left to Beckett or Chekhov.

Blue Is for Mourning was a critical disaster. The well-mannered Whittaker opened his review with "It is a courageous critic who writes a play, but nobody has ever accused Nathan Cohen of lacking courage." He gave credit, and I think justly so, to its "sincerity, its truth of background, its nice balance between humor and seriousness" and the "real warmth" of Cohen's writing when he is "snuffling out a bit of warm humor here, a snatch of folklore there," but nevertheless discerned something wrong with the play which made it "difficult to accept as a dramatic entity." He located the fault, as I have above, in the awkward centrality of Blue McGregor, a "chorus" figure who had "moved right down-stage to dominate the action," thereby contributing to a failure to make the "portrait" of the hero, Jesse Baker, "come completely alive." While he commended most of the performers, including Eric House as Walsh, he castigated Meyer for failing to provide the collaborative dramaturgical assistance which a director must when mounting a new play.

As Wayne Edmonstone amusingly suggests, Jack Karr summoned up an almost Cohen-like tone in his Toronto Star review: ". . . seldom, it seems to us, has any play worked so hard to make a point, only to discover, at the final curtain, that there was actually very little point to be made in the first place" (Karr qtd. in Edmonstone 206). Allowing that there were "one or two scenes of genuine theatrical merit," that the dialogue was "generally well handled" (Whittaker had called it "utilitarian") and that Cohen had avoided the "self-conscious nationalism which plagues most Canadian playwrights," Karr complained that the characters "spend their time wrangling over details which have no clear connection with the main theme" and termed the character of Blue a "distracting windbag" (February 16, 1953: 11).(24)

Perhaps the unkindest cut of all came from Lister Sinclair on Cohen's customary entertainment review beat CJBC Views the Shows (February 15, 1953?): "Nathan Cohen has announced that his new play . . . is to be the first of a trilogy. Let us hope he will reconsider this terrible threat" (Sinclair qtd. in Drainie 163). Whether this was the review's opening salvo or parting shot is unclear,(25) but his devastating comments apparently had the Jupiter board members howling with laughter on John Drainie's living room floor, despite the unpleasant reality that they stood to lose a lot of money with the production's failure (Drainie 163; Frankfurter, July 21, 1996 and Peterson July 22, 1996).

There is conflicting evidence of a contentious relationship between the critic-playwright and the production. According to Len Peterson, the Jupiter board member responsible for producing Blue Is for Mourning, Cohen "felt hurt that they should find a single fault with it," made few and inadequate revisions, failed to attend rehearsals and was not in evidence on opening night. He is of the opinion that director Meyer and actor Donald McKee did "the best they could with what they had" (July 22, 1996). On the other hand, Gloria Cohen, Nathan's widow, asserts that her husband refrained from attending rehearsals because he feared that, as a critic, it would be unprofessional of him to "interfere." She assures me he was present on opening night, as was she, and that neither of them cared for Donald McKee's performance at all. Cohen, apparently, had written the part with a specific actor in mind (she cannot remember who), and could not reconcile himself to McKee as Blue (telephone conversation July 29, 1996). The designer, Sydney Newman, whose realistic two-level set was, according to Herbert Whittaker, "extraordinarily well-handled" (Globe and Mail February 14, 1953), feels that the play was directed in too "downbeat" a fashion (telephone conversation July 21, 1996). This may reflect Cohen's opinion, given their later close association at CBC Television.(26)

Whatever the history of the production, Cohen apparently took the resulting criticisms of his play gracefully. A rough player on the critical ice, he obviously accepted that in the struggle for excellence a few body checks were inevitable. This is evident from his positive review of Jupiter's last Canadian offering, Lister Sinclair's The Blood Is Strong, which opened December 2, 1953 at a converted hall in the old Ontario Normal School, then part of Ryerson Technical Institute.

The Blood is Strong

Like Socrates, The Blood Is Strong began life as a radio play. Directed by Andrew Allan, the half-hour piece went to air February 2, 1945 on This Is Our Canada, featuring Frank Peddie as the Cape Breton-dwelling Scot Murdoch MacDonald, Ruth Springford as his wife, Bernard Braden as son James and Lister Sinclair himself as another son, Alan, who tells the story (Play on Words 27-46).

For the 1952 stage version Sinclair turned son Alan into daughter Kate and eliminated the role's narrative function. He expanded son James's dramatic and comic potential and fleshed out the cast with colourful local characters such as the taciturn native, Joe Threefingers, and charismatic Barney Hannah, a Cape Breton backwoodsman Cohen drily designated as "Sinclair's retaliation against James Fenimore Cooper" (CJBC December 6, 1953). Sinclair further transformed his somewhat barebones radio play into one of charming theatricality by adding songs, recitations, a dance, a wedding reception and, improbably, a bear hunt through the house, and provided love interest and family conflict by creating an increasingly amorous relationship between Kate and Barney. He also gave more scope to the part of Mary, the mother, by investing her with both comedy (the dandelion root tea episodes) and the poignancy of self-sacrifice (the kitchen pump episodes).

Whittaker aptly described The Blood Is Strong as "a series of vignettes rather than a play with any great shape" (Globe and Mail December 3, 1953) and indeed the plot, which Cohen dubbed a "sketchy tracery" (CJBC December 6, 1953) is largely a life-line from which to hang a few events from the lives of a 19th century immigrant family: homesick Murdoch MacDonald buys boat tickets for his family to return to Skye; his wife, Mary, at first resistant, resigns herself to the upheaval; daughter Kate who, while teaching Barney to read has fallen in love with him, does not want to go, nor does her brother James, who aspires to a life of high adventure on the sea; Murdoch delays departure for months in order to benefit from a good farm deal; Barney embarks on a campaign to win the disapproving Murdoch's permission for Kate's hand in marriage; he succeeds; Barney and Kate are wed; word arrives at the wedding festivities that James has drowned at sea; an epilogue reveals that Kate and Barney (now a lawyer) settled in Upper Canada and have produced children; Mary MacDonald has died prematurely; Murdoch has resigned himself to life in Cape Breton.

The principal theme of the play is a universal one: the immigrant's longing to return to a homeland which may, however, loom rosier in memory than in reality. Murdoch yearns for the Skye he sharecropped, but forgets the harsh life there and their eviction from it by ruthless landlords. He ignores the fact that the New World represents an improvement of their living conditions, to which his wife has happily adjusted, and that Cape Breton, not Skye, is now his children's homeland. At the risk of being labelled a "reductive nationalist,"(27) I Will venture to say that it is this theme of the immigrant which also makes The Blood Is Strong the most quintessentially Canadian play of Jupiter's output. Socrates, set in ancient Greece, has a universal rather than parochial significance; The Money Makers, though intensely Canadian in its attempts to delineate Canada-U.S. cultural distinctions, takes place in Hollywood, its most entertaining character a flamboyant American; Blue Is for Mourning, while thoroughly imbued with the spirit of its Cape Bretoners, looks outward to more international, socialist concerns. The issues of immigration and homeland permeate the history of Canada -- indeed they continue today in the melting pot/multiculturalism controversy, for example -- as they permeate The Blood Is Strong. At the play's end a chain of immigration becomes apparent in the three different homelands of the family's successive generations: Skye, Cape Breton and Upper Canada.

The play's lively, characterful dialogue -- mercifully not written in stage "Highlandese" (they would have been Gaelic-speakers)-"plays even better than it reads," according to actor Liz Gordon, who performed Mary MacDonald in the most recent professional production. "The audience especially identifies with Murdoch and Mary's wry interactions."(28) Poetry infuses sections of the piece, plangent with the ache of nostalgia. Murdoch's words to his son, delivered in a soft highland lilt, could not fail to move even the sternest of critics:

It's not a year since you left the old home with the men and women weeping on the jetty, and the pipers playing the old Laments. Is that not adventure: to hear the curlews crying, and see the mist curling round the land of your fathers, and know that you're not to see them again? And then to cross the green water with the men and women dying on the ship all round you, and sewn up in canvas with shot at the heels, and slipped into the cold sea to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body when the sea shall give up her dead. You've seen all this with your own eyes, and still you talk of adventure. (33)

Cohen, hailing Sinclair as "our most adventurous dramatic poet," declared The Blood Is Strong to be a "gentle fiction which takes us into a sea of domestic joys and sorrows" (CJBC December 6, 1953); Whittaker deemed the second act to be "human and friendly, and full of kindly observation of a proud folk"; Rose MacDonald of The Telegram seemed relieved that Sinclair had "set aside his high-toned style and ... acid wit to write with unselfish charm . . . a kindly, still keen sense of humour and . . . a simple, touching pathos" (December 3, 1953). All three detected niggling dramaturgical problems, mostly related to awkwardness in the first and third acts, but were unanimous in praising Sinclair's depiction of the principal characters and lauded Frank Peddie and Ruth Springford for their strong interpretations.(29) Cohen, however, in his review of The Blood Is Strong, sei zed the opportunity to deliver another jab at Socrates. Reminding his listeners that he alone of the "local reviewing brotherhood" had not "applauded" it, he dismissed Socrates as "solemn nonsense," pronouncing The Blood Is Strong to be its superior, both structurally and dramatically, with greater authenticity of conflict and character. And, having credited Esse Ljungh with saving Socrates, so, too, he commended director Leonard White and the production team for "giving substance to Mr. Sinclair's lean theme," elaborating the "sketchy tracery of plot with sound theatrical acumen."(30) With this veiled accusation of insubstantiality, he reinforced, not unjustifiably, his basic assessment that the play, though it "always moves in an authentic vein," was best suited for "summer theatre companies and amateur groups combing the trail for popular Canadian plays." Given Cohen's disdain for the amateur scene this was no great recommendation, and implied that The Blood Is Strong did not deserve to be ranked among the works of "O'Casey, Henri Becque, Chekhov, Brecht, Lorca, André Obey, Sternheim, Edmund Wilson, Strindberg," those playwrights he once had urged Jupiter to produce for its audience of "taste and intelligence" (CJBC May 24, 1953). It could be said that he had aimed toward a more substantial theme than Sinclair with Blue Is for Mourning -- the death of a hero fighting for human rights is arguably more worthy of the serious modern stage than mere scenes from domestic life -- but then he had turned his play into just that by eliminating the hero from the action, and The Blood Is Strong's domesticities had beguiled the audience where Blue Is for Mourning's had not. The Blood Is Strong was a critical and financial hit(31) -- Jupiter's last, it turned out, for the theatre was to cease operations by February of 1954.

The Death and Legacy of Jupiter

The ambitious moves into the Royal Alexandra and the Ryerson space, coupled with a flight of their sponsors to the recently inaugurated, more establishment-oriented Stratford Festival and Crest Theatre enterprises (Peterson), conspired to balloon Jupiter's deficit to ten thousand dollars. The active board members were exhausted and, according to Glen Frankfurter too many artists from their "talent pool" were heading to the United States (July 21, 1996). Cohen, who in spite of the tongue-lashings he occasionally administered admired the Jupiter and shared its ideals (Peterson, qtd. in Drainie 156), ascribed the theatre's collapse to a nexus of causes: "dilettantism," mismanagement, the "clashing personalities" of an "unwieldy" board, a "shocking irresponsibility of judgment" and the forsaking of their original aim to present "drama critical and interpretive of the social temper of our age" (CJBC June 13, 1954).

A perusal of Jupiter's list of plays produced might quickly put to rest Cohen's latter accusation. Besides, the company had indeed subscribed, as best it could, to the first of its principal aims-"to promote the production of plays by Canadians, to assist the emergence of a truly Canadian voice in the theatre"-devoting more than a quarter of its output to Canadian works, and this before the Canada Council was set up to fund such indigenous development (1957). If we consider that Dora and Mavor Moore's coeval New Play Society produced eleven mainstage Canadian plays out of seventy during its twenty-five-year history (1946-1971) (Sperdakos 13), the Jupiter ratio represents a significant improvement. Jupiter's successor, the Crest Theatre, managed to achieve only half that ratio over their thirteen-season existence, with nineteen Canadian-written shows out of nearly one hundred and fifty produced.(32) Moreover, as we have seen, three of Jupiter's Canadian plays were among its most successful ventures. While it is true that, of these, only The Blood Is Strong could lay claim to have entered the "Canadian Canon," with subsequent productions over the years, both The Money Makers and Socrates were picked up for broadcast on television.

It is also true that neither Ted Allan nor Lister Sinclair went on to create significant bodies of work for the stage. Allan is the better represented of the two, however, but worked principally abroad. The Secret of the World was produced in London, England in 1962 (featuring Al Waxman, among others), and My Sister's Keeper, first presented in 1969, also in London, under the title I've Seen You Cut Lemons, was revised and revived with its present title in a production directed by William Davis at Festival Lennoxville in 1974, starring Patricia Hamilton and Roland Hewgill. Allan was to achieve a great success with the screenplay for Lies My Father Told Me (1975), a tender, moving film which received international acclaim. He later adapted it for the stage as "a play with music," which was produced in Los Angeles in 1983 directed by expatriate Canadian Arthur Hiller. He also wrote the screenplay for the late Philip Borsos' controversial film Bethune: The Making of a Hero, which premiered at Cannes in 1990. Although, according to the Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre (15-16), Allan always laid claim to the essential authorship of Joan Littlewood's Oh What a Lovely War! (1964), his only other published playscripts are Chu Chem: a Zen-Buddhist-Hebrew Musical Comedy (1966), and Double Image (1957), written with Roger MacDougall, and produced by the Crest in April 1958, directed by Malcolm Black.(33)

Lister Sinclair has concentrated on the documentary side of his catholic interests and, among other accomplishments, has hosted the CBC Radio program Ideas for many years. He claims, however, that his subsequent film script for The Blood is Strong represents "much the best version of the piece" (July 26, 1996), but no-one as yet has taken it up.

Nathan Cohen attempted no more plays. He went on to write prolifically, first for the Toronto Telegram and then, from 1959, for the Toronto Star, establishing a reputation both here and abroad as Canada's pre-eminent entertainment critic. Conveyed in a rich, authoritative prose, his incisive perceptions and opinions, sometimes harsh and denunciatory, never partial simply because a work was Canadian-made, earned him the respect, if not the affection, of the Toronto theatre community. His dream of a significant place for Canadian playwrights in a vital Canadian theatre was to remain only fitfully realized during his lifetime and, unmitigatedly disastrous though his own dramatic assay with the theatre had been, Jupiter formed part of that realization. A more fully fledged embodiment of his dream-and that of the Jupiter's founders-was not to arise until after his untimely death, at age 47, in 1971. The contributions of playwrights during the next two decades David French, James Reaney, Sharon Pollock, David Fennario, Michel Tremblay, George F. Walker, Michael Ondaatje, John Murrell, Judith Thompson, Anne-Marie MacDonald, to name but a few of the most celebrated-were to represent not merely the "emergence" of a Canadian voice in the theatre but an outright explosion.

NOTES

1. For more information about this era and the

issues of playwrighting and nationalism in Canadian theatre see Richard

Plant's entry "Drama in English" in The Oxford Companion to Canadian

Theatre (153-159). For more about the New Play Society's 1949-1950

season see Paula Sperdakos, Dora Mavor Moore: Pioneer of the Canadian

Theatre (185-192), and Mavor Moore, Reinventing Myself (173-179).

Return to article

2. From a press release reproduced in an appendix

to Terry Kotyshyn's MA thesis "Jupiter Theatre Inc.: the life and death

of Toronto's first professional full-time theatre." University of Alberta

Department of Drama, Edmonton, Alberta, 1986. Copy in the Metropolitan

Toronto Reference Library (hereafter referred to as MTRL). Other Jupiter

materials there include a vertical file of sundry documents and reviews,

a microfiche of newspaper reviews, a complete collection of theatre programs,

and bound typescripts of Ted Allen's The Money Makers and Nathen

Cohen's Blue is for Mourning.

Return to article

3. Len Peterson suggests that Cohen, younger

than the Jupiter founders, had more or less "sat at their knees" during

his early years in Toronto, learning about theatre and their aspirations

for it (telephone conversation, July 22, 1996).

Return to article

4. Among his published plays, many for young

adults, are The Great Hunger (1958), Billy Bishop and the Red

Baron (1972), Women in the Attic (1972), Almighty Voice

(1974), and They're All Afraid (1981). He has mentioned an unpublished

playscript, Daffidowndilly, as one of which he is particularly proud

(telephone conversation September 21, 1997). In his own estimation, he

was the first Canadian playwright to earn his living exclusively as such

(telephone conversation, July 22, 1996).

Return to article

5. This egalitarian division of labours was,

in practice, not to be. The core directorate ultimately shouldered most

of the burden of keeping the theatre going.

Return to article

6. This list is derived from the complete collection

of Jupiter programs at the Performing Arts desk of the MTRL.

Return to article

7. See the handsome brochure of the ambitious

1953-54 subscription season in the vertical files of the MTRL.

Return to article

8. Directed by Andrew Allan, this radio programme

of Socrates featured Mavor Moore in the title role, with Frank Peddie

as Anytus, Lome Greene as Lycon and Sinclair himself as a soldier (information

from Linda Partington at CBC Radio Archives).

Return to article

9. In the vertical files of the MTRL.

Return to article

10. The latter production was designed and directed

by Globe critic Herbert Whittaker. See also Whittaker's Theatricals

(18ff). The cover of this book features Whittaker's design for the 1951

production of Galileo.

The American writer Dalton Trumbo (later to pen the screenplay of Spartacus)

had recently been released from a 10 month jail-term, incurred during the

McCarthy witchhunts. The Jupiter wished to show solidarity with blacklisted

Trumbo by producing a play of his (Peterson, telephone conversation July

22, 1996). See also next note.

Return to article

11. Len Peterson: "We were not establishment.

We were considered radical and not quite safe. Sartre? Dalton Trumbo? Brecht?

Lister Sinclair? Ted Allan?" (qtd. in Kotyshyn 107). Gloria Cohen, Nathan

Cohen's widow, disputes their radicalism, however, pointing to Toronto's

earlier Theatre of Action (1936-1940) as a more authentic manifestation

of an anti-establishment consciousness (telephone conversation July 29,

1996).

Return to article

12. Jupiter was to mount two Fry plays, to great

acclaim: The Lady's Not for Burning (which they remounted at Hart

House) and A Sleep of Prisoners. They also produced Ring Round

the Moon, Fry's adaptation of a play by Anouilh.

Return to article

13. A few photographs of Socrates and

several other Jupiter productions, including Blue Is for Mourning,

collected by Herbert Whittaker, are currently held by the Special Collections

of the MTRL. They are also appended to Kotyshyn. The published text of

the play, furthermore, is illustrated with delightful sketches of the cast

done by Kay Ambrose (Agincourt: The Book Society of Canada, 1957).

Return to article

14. Among the cast were Christopher Plummer as

Alcibiades, David Gardner as Agathon, Paul Kligman as Aristophanes, and

Murray Westgate as Lycon. (While some may remember Westgate as the Esso

man on the old Hockey Night in Canada he also starred as "Jake"

in the CBC TV series Jake and the Kid in the early 1960s.)

Return to article

15. I am indebted to Gloria Cohen who very kindly permitted me access to her husband's radio scripts, collected on microfilm at The Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Special Collections department, as are the rest of the Cohen papers. (The originals are held in the Public Archives in Ottawa.) General access to the Cohen papers is restricted until Gloria Cohen's death.

We cannot be one hundred percent certain that these typescripts represent

what Cohen finally said on-air. There are frequent revisions in fountain

pen and occasionally pencil (which seems to have been used for the last

minute changes), and Cohen was in a position, as reader, to make changes

extempore if the occasion suited him. I trust, however, judging

by the great care with which he amended his typescripts and their high

level of eloquence, that what we see is what the listeners got.

Return to article

16. Starring Budd Knapp (Norman Jewison appeared

in it!) the production was directed by Montreal-based American Roeberta

Beatty, of the Montreal Repertory Company. The next season she staged Anna

Christie for Jupiter (featuring the young Timothy Findley), with considerably

less critical approval from Cohen, however.

Return to article

17. The typed title of the script in MTRL --

The Glittering Wilderness -- is scratched out and The Money Makers

substituted in pencil. Certain character names differ from those in the

produced play; most significantly, in the typescript the young writer and

his wife are named David and Diane Wright, not Michael and Julie Bedford

(see Kotyshyn 141 and reviews of Whittaker, Karr and Cohen). Given the

overloaded significance of "David Wright" as a name ie. "David," as in

"David and Goliath," and "Wright," as in "playwright ... .. writer," and

"right versus wrong," the name "Michael," as in "archangel with a sword"

("pen" implicit) coupled with the neutral "Bedford" would seem to represent

a fortunate rethink on Allan's part.

Return to article

18. "A medieval writer ... might have set the

stage in Hell. Times change. I have set it in Hollywood."

Return to article

19. I would suspect, however, that research would

prove her "perhaps" to be quite justified.

Return to article

20. He gave top "acting honors" to David Gardner,

however, for his "full length, intricately detailed portrait" of Finch's

fellow producer and rat in the race, Ralph Sherman. Of the 149 actors hired

by Jupiter during its period of operation, Gardner was by far the most

frequently engaged, appearing in six out of the fifteen plays produced,

plus the remount of The Lady's Not For Burning (information derived

from Kotyshyn's list of the actors who performed for Jupiter 153-7).

Return to article

21. I have been unable to track down the actual

performed version. The one in the library, given its variant (original?)

title and character names, seems to be an earlier draft. Its ending is

no more than adequate but not, in my estimation, "untenable."

Return to article

22. Sample line: "MARGE: I concede it's quite

possible for a person not to be a Marxist and not fully understand what's

happening yet still do what has to be done" (11 1, 33).

Return to article

23. Adapted and produced live by Silvio Narizzano

on CBC Television Theatre (information supplied by Linda Partington,

CBC Radio archives). The play was later produced at the Arts Theatre Club

in London, England in 1955, re-titled The Ghost Writers (Oxford Companion

to Canadian Theatre 15).

Return to article

24. Out of mercy for Cohen's ghost I will quote

only sparingly from the review in the Varsity: "critics who throw

stones shouldn't write plays." The reviewer, Malcolm MacKinnon, like Whittaker,

praised Sydney Newman's set: "It certainly should be preserved in case

someone some day writes a play worthy of it" (February 16, 1953: 4).

Return to article

25. My attempts to track down the full text of

the review have failed, having appealed to CBC Radio Archives, Lister Sinclair,

Robert Weaver (the producer) and Bronwyn Drainie. The latter, according

to her book, indicates that the by now legendary quote began the review.

Sinclair, in a recent phone conversation (July 21, 1996) claims that it

ended it. In any case, Drainie explained to me (phone message July 25,

1996) that the quote came from Peterson and that there is probably no surviving

text, simply oral tradition.

Return to article

26. The Toronto-born and educated Sydney Newman, who went on to success in England as a producer-director for British television, creating such programs as The Avengers, Dr. Who, The Forsyte Saga and a Hamlet at Elsinore with Christopher Plummer, began his career as a designer for Toronto's Theatre of Action and for Jupiter. He also designed Ring Round the Moon for them in 1953 at the Royal Alexandra (see the Herbert Whittaker collection of Jupiter photographs in the Special Collections of the MTRL, also appended to Kotyshyn's thesis).

Cohen worked as a script editor for Newman at CBC Television from 1954-58. Newman has called him a "brilliant, strong arm to me," declaring himself "indebted to him" (telephone conversation July 21, 1996).

One might cautiously substantiate an opinion that Cohen felt Jupiter

had ill-served Blue Is for Mourning by inspecting a crossed-out

section of the typescript for CJBC Views the Shows, May 24, 1953 in which

he refers to Anna Christie, Galileo and his own play as being

among Jupiter's "blatant production fiascos." The mimeographed typescript

of Blue Is for Mourning in MTRL, moreover, has been handsomely bound in

red morocco, with its title lettered and decorated in gold leaf, perhaps

indicating that Cohen hoped future generations would better appreciate

the misunderstood work.

Return to article

27. Mavor Moore brands Nathan Cohen as such when

discussing the latter's remark about the New Play Society's production

of Lister Sinclair's Man in the Blue Moon, i.e. "There is nothing

Canadian about it, neither in content, characters nor atmosphere" (Canadian

Jewish Weekly May 8, 1947; Moore 165-6).

Return to article

28. Personal conversations, July-August, 1996.

The production in which Ms. Gordon appeared was mounted at Cullen Barns

Dinner Theatre in Markham, Ontario, directed by Mamie Walsh, with Alan

Price as Murdoch, January 20-April 9, 1988. Sinclair approved very much

of this production and attended it three times.

Return to article

29. Others praised in the cast, though with less

unanimity of opinion, were Margaret (Nonnie) Griffin as Kate, Hugh Webster

as James, and James Doohan (later of Star Trek fame) as Barney.

Return to article

30. Leonard White, who had directed and performed

in A Sleep of Prisoners for Jupiter (with Don Harron in the cast),

later worked as a director and producer under Sydney Newman on The Avengers

for Thames TV, which staffed two former Jupiter actors: Patrick Macnee

(A Sleep of Prisoners, The Lady's Not For Burning [remount])

and Honor Blackman (Crime of Passion) (Newman July 21, 1996).

Return to article

31. The Blood Is Strong was televised

twice in the mid-fifties on CBC, with Peddie, Springford, Doohan and Griffin;

Robert Allen the producer and director, especially admired Peddie, and

considers the script "very warm" (personal conversation, June 1996).

Return to article

32. The figures regarding the NPS's Canadian productions seem to conflict wildly. Richard Plant, in his article "Drama in English" in The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre (158) claims forty-seven between 1946 and 1956, as does David Gardner, from whose "Dora Mavor Moore (1888-1979)" Plant got his information. Gardner informed me that the discrepancy with Sperdakos may be explained by whether or not one includes in the count such output as their yearly review Spring Thaw, of which there were 14 produced by NPS, some thirteen or so shorter works, and nine original plays produced as part of Dora Moore's work with psychiatric patients (telephone conversation September 16,1997). Paula Sperdakos concurs with this explanation: her count includes only full-length plays given a mainstage production (telephone conversation September 16 1997).

Information on the Crest's Canadian output is derived from the "Crest

Chronology" in Canadian Theatre Review 7 (Summer 1975): 45-50.

Return to article

33. Actor-director Donald Davis, one of the Crest

Theatre's founders, tells me that their production of Double Image

was decidedly not a success and that the difficulties he encountered playing

the double central role, coupled with his onerous managerial duties, drove

him from acting on the Crest stage for many years (personal interview,

August 20, 1997). The play apparently had enjoyed a seven month run in

1956 at the Savoy Theatre in London, starring Richard Attenborough.

Return to article

WORKS CITED

Allan, Ted. The Money Makers. Bound mimeographed ts., 1952. Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library.

Benson, Eugene, L.W. Conolly, eds. The Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre. Toronto, New York: Oxford UP, 1989.

Cohen, Gloria. Telephone conversation. July 29, 1996.

Cohen, Nathan. Blue Is for Mourning. Bound mimeographed ts., 1953. Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library, Toronto.

________. "CJBC Views the Shows." CBC. CJBC, Toronto. Tss. on microfilm. The Nathan Cohen Papers. Special Collections, Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library:

________. Rev. of The Blood Is Strong by Lister Sinclair. Jupiter Theatre at Theatre-at-Ryerson. December 6, 1953.

________. Rev. of Crime of Passion by Jean-Paul Sartre. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. April 20, 1952.

________. Rev. of The Lady's Not For Burning by Christopher Fry. Jupiter Theatre at Hart House. May 24, 1953.

________. Rev. of The Money Makers by Ted Allan. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. November 16, 1952.

________. "Professional Theatre in Toronto." June 13, 1954.

________."Season in Retrospect." July 27, 1952.

________. Rev. of Socrates by Lister Sinclair. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. February 24, 1952.

"Crest Chronology." Canadian Theatre Review. 7 (Summer 1975): 45-50.

Davis, Donald. Personal interview. August 20, 1997.

Drainie, Bronwyn. Living the Part: John Drainie and the Dilemma of Canadian Stardom. Toronto: Macmillan, 1988.

________. Telephone communication. July 25, 1996.

Edmonstone, Wayne E. Nathan Cohen: The Making of a Critic. Toronto: Lester and Orpen, 1977.

Frankfurter, Glen. Telephone conversation. July 21, 1996.

Gardner, David. "Dora Mavor Moore (1888-1979)." Theatre History in Canada / Histoire du théâtre au Canada. 1. 1 (Spring 1980): 5-11.

________. Telephone conversation. September 16, 1997.

Karr, Jack. "Showplace." Rev. of Blue Is for Mourning by Nathan Cohen. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. Toronto Daily Star February 16, 1953: 11.

.________. Rev. of The Money Makers by Ted Allan. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. Toronto Daily Star November 15, 1952: 19.

Kotyshyn, Terry. Jupiter Theatre Inc.: the life and death of Toronto's first professional full-time theatre. MA thesis. Edmonton: University of Alberta, Dept. of Drama, 1986.

MacDonald, Rose. "Even Flow of Wit, Charm, Pathos." Rev. of The Blood Is Strong by Lister Sinclair. Jupiter Theatre, Theatre-at-Ryerson. Toronto Telegram December 3, 1953: 5.

MacKinnon, Malcolm. "Blue is for Nathan." Rev. of Blue Is for Mourning by Nathan Cohen. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. Varsity February 16, 1953: 4.

Moore, Mavor. Reinventing Myself. Toronto: Stoddart, 1994.

Newman, Sydney. Telephone conversation. July 21,1996.

Peterson, Len. Telephone conversation. July 22,1996 and September 21, 1997.

Sinclair, Lister. The Blood Is Strong. Agincourt: The Book Society of Canada, 1952.

________. A Play on Words & Other Radio Plays. Toronto: J.M. Dent, 1948.

________. Socrates. Agincourt: The Book Society of Canada, 1957.

________. Telephone conversation. July 21,1996.

Sperdakos, Paula. Dora Mavor Moore: Pioneer of the Canadian Theatre. Toronto: ECW, 1995.

.________. Telephone conversation. September 16, 1997.

Whittaker, Herbert. "Show Business." Globe and Mail November 13, 1952: 21.

________. "Show Business." Rev. of The Blood Is Strong by Lister Sinclair. Jupiter Theatre. Theatre-at-Ryerson. Globe and Mail December 3, 1953: 28.

. "Jupiter Production of Socrates Stirs Breath of Greatness." Rev. of Socrates by Lister Sinclair. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. Globe and Mail February 23, 1952: 11.

. ________. "Show Business." Rev. of The Money Makers by Ted Allan. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. Globe and Mail November 17, 1952: 16.

________. "Study of Cape Breton Life Not Quite a Dramatic Entity." Rev. of Blue Is for Mourning by Nathan Cohen. Jupiter Theatre at the Museum. Globe and Mail February 14, 1953: 10.

________. Whittaker's Theatricals. Toronto: Simon and Pierre, 1993.

APPENDIX A: Productions of Jupiter Theatre

| Opening Date | Play | Author | Director |

| 14/12/1952 | Galileo | Bertolt Brecht | Herbert Whittaker |

| 25/01/1952 | The Biggest Thief in Town | Dalton Trumbo | Roeberta Beatty |

| 22/02/1953 | Socrates | Lister Sinclair | Esse Ljungh |

| 18/04/1953 | Crime of Passion | Jean-Paul Sartre | Edward Ludlum |

| 17/10/1953 | Anna Christie | Eugene O'Neill | Roeberta Beatty |

| 14/11/1953 | The Money Makers | Ted Allan | Aaron Frankel |

| 16/01/1953 | The Lady's Not for Burning | Christopher Fry | John Griffin |

| 13/02/1953 | Blue Is for Mourning | Nathan Cohen | Jerome Meyer |

| 13/03/1953 | Summer and Smoke | Tennessee Williams | Henry Kaplan |

| ?/04/1953 | A Sleep of Prisoners | Christopher Fry | Leonard White |

| 17/04/1953 | The Show-off | George Kelly | Robert Christie |

| 15/05/1953 | The Lady's Not for Burning (remount) | Christopher Fry | John Griffin |

| 11/11/1953 | Right You Are | Luigi Pirandello | Joseph Furst |

| 02/12/1953 | The Blood Is Strong | Lister Sinclair | Leonard White |

| 19/10/1953 | Ring Round the Moon | Anouilh/Fry | Leonard Crainford |

| 11/01/1954 | Relative Values | Noel Coward | Leonard White |

APPENDIX B: Cast Lists of Jupiter's Canadian Plays

Socrates

Fisherman Jack Northmore

Meletus Doug Haskins

Aristophanes Paul Kligman

Agathon David Gardner

Megillus Doug Master

First Farmer Ivor Murillo

First Woman Alice Mather

Second Farmer Jack Mather

Second Woman Margot Lassner

Lycon Murray Westgate

Crito Donald Glen

Anytus Robert Christie

Alcibiades Christopher Plummer

Phaedo Ivan Thomley-Hall

Herald Ed Holmes

Philip Colin Eaton

Triptolemus John Atkinson

Cyrus Alex McKee

Xanthippe Muriel Cuttell

Socrates Frank Peddie

Apollodorus Ed Holmes

Prinides Jack Mather

Sergeant Ivor Murillo

Kratmos John Maddison

First Officer Jack Northmore

Second Officer Jack Mather

Farm Women Lois Ould, Hazeldine Hall

The Children Sharon and Ronald Kristjanson

The Money Makers

Paul Finch Lorne Greene

Maggie June Duncan

Michael Bedford John Drainie

Nicholas Lovell Roy Partridge

Ralph Sherman David Gardner

Manicurist Mary Lou Collins

Barber Rex Sevenoaks

Bootblack Cal Whitehead

Marge Lovell Joanne Stout

Secretary Billi Tyas

Blue is for Mourning

Tom Walsh Eric House

Fred Sharkey Douglas Master

Molly Harris Cosette Lee

Angus "Blue" McGregor Donald McKee

Cora Baker Jane Graham

Emma Baker Doris Gill

Sarah Baker Barbara Cummings

The Blood Is Strong

Joe Threefingers Robert Barclay

Barney Hannah James Doohan

Mary MacDonald Ruth Springford

Kate MacDonald Margaret Griffin

Murdoch MacDonald Frank Peddie

James MacDonald Hugh Webster

Mrs. Reading Christine Thomas

Mrs. Morrison Madeline Hussey

Hector Morrison John Atkinson

Mr. Reading Cec Linder

A Sailor Jonathan White

Guests Stephanie Wellin, Ann Shipman, Walter Plinge, Ty Crawford