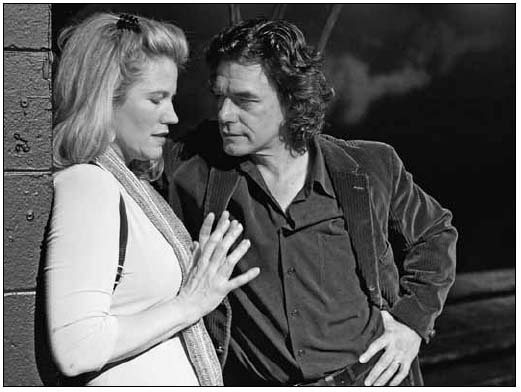

Jerry and Dodge (Performers:Randi Helmers and Tom McCamus; Tarragon Theatre Production,Toronto, 2004) Photo by Nir Bareket, courtesy of Tarragon Theatre.

ROBYN READ

Cet article explore le fonctionnement du monstrueux – plus précisément, la transmutation et le processus de transformation en monstre – dans le discours théâtral de la pièce Capture Me de Judith Thompson. La sixième pièce de Thompson, dont la première a eu lieu en janvier 2004 au Tarragon Theatre à Toronto, transcende le simple binaire «bien vs. mal» pour se demander si nous sommes tous des versions de monstres; dans nos rôles de mari, ami, père ou mère, la rage est en nous tous. Cet article est né de la lecture des écrits de Susan J. Brison (Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of a Self) et Margrit Shildrick (Embodying the Monster: Encounters with the Vulnerable Self), exposés de faits qui facilitent l’examen des procédés par lesquels Capture Me déconstruit et reconstruit les frontiers qui entourent et séparent à la fois le soi et le monstre, et l’observation des conditions et des lieux dans lesquels le monstrueux est présent dans la société occidentale contemporaine.

“I felt like a pawn – a helpless, passive victim – caught up in a ghastly game in which some men ran around trying to kill women, and others went around trying to save them” (Brison 90). This statement was made by philosophy professor Susan J.Brison in her book Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of a Self, a “personal narrative of recovery and a philosophical exploration of trauma,” written ten years after she went on a morning walk while in the south of France and was “attacked from behind, severely beaten, sexually assaulted, strangled to unconsciousness, and left for dead” (back cover). When her lawyer met with her while she was still in the hospital recovering, he gave her this advice: “[D]on’t think of your assailant as a human being. Think of him as a wild animal, a beast, a lion” (Brison 86).

By encouraging Brison to imagine a “wild animal” or “beast,” her lawyer was associating her assailant with the “so-called monstrous races” (Shildrick 15). Margrit Shildrick, in Embodying the Monster: Encounters with the Vulnerable Self, examines early records of “monsters, marvels and meanings” in Western history (8). In these instances, the boundaries dividing the different categories of monster are fluid. In the sixteenth century, for example, Stephen Bateman grouped “fabulous creatures ofmythology” together with “hybrid human forms” and “strange animals of land and sea” in the “medieval tradition of bestiaries” (Shildrick 15)1. However, Brison’s lawyer makes one distinction: he identifies a specific species of monstrous animal, the “lion,” a creature that figures prominently in the plays of Judith Thompson.

Susan Brison’s aftermath philosophy and Margrit Shildrick’s postmodern study of the monster motivated and facilitated my study of Judith Thompson’s latest play, Capture Me. Thompson creates characters who struggle to reconcile their separate selves, “to bridge [the] persistent gulf between the self that speaks and the self represented in the discourse as the subject, the ‘I’”(Knowles 8). After her attack, Brison struggled to remake her self and also make sense of her surroundings. She felt that she had “ventured outside the human community, landed beyond the moral universe, beyond the realm of predictable events and comprehensible actions”(x). I wish to examine Capture Me as a bridge between two communities: one which is real and one that can only be imagined. There is a society where violence has come to be expected, and an unknown domain where a kind of trauma exists that cannot be anticipated. Thompson’s choices as a playwright, and the ways in which Capture Me deconstructs and reconstructs the boundaries surrounding, and separating, the self and the monster, reveal how and where the monstrous may be present within contemporary Western culture.

Capture Me is the sixth play by Judith Thompson to premiere at the Tarragon Theatre in Toronto. It is the story of Jerry Joy Lee (played by Randi Helmers in the Toronto production), a kindergarten teacher who is stalked by her ex-husband Dodge Kingston (Tom McCamus). A former university professor, Dodge reforms troubled youths at the local jail. By giving seminars on violence, he attempts to rehabilitate children while philosophizing about, and fighting against, his own evil instincts.

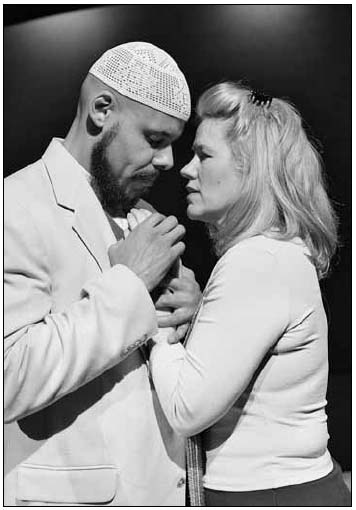

Jerry has an obsession of her own; after many attempted phone calls where she is unable to speak, she at last makes contact with her biological mother, Dr. Delphine Moth (Nancy Palk). However, Jerry is a woman both pursued and abandoned; her mother refuses to form a relationship with her daughter. The responsibility of restoring Jerry’s faith is left in the hands of her acerbic friend and fellow teacher Minkle (Chick Reid), and the father of one of her students, Aziz Dawood (Maurice Dean Wint), with whom she falls in love. Aziz has fled an unidentified Arabic nation after witnessing the massacre of his entire family except for his daughter Sharzia, who has come with him. He does not speak of his past.

Before discussing Judith Thompson and Capture Me, it is necessary to establish how the terms “monster” and “monstrous” are defined and utilized within the context of this essay. Shildrick states, “[M]onsters of course show themselves in many different and culturally specific ways [. . .] what is monstrous about them is most often the form of their embodiment” (9). Traditionally, it is the monster’s body that places it in opposition to that which is intact, human, and “natural.” Over time, the image associated with the monster has become a composite, an accumulation of the many shapes and forms it has taken both historically and currently in popular culture. The inability to associate just one figure or sign with the monster perpetuates its instability. However, when concerns are extended beyond solely the corporeality of the monster, when the monstrous is interpreted as a concept rather than a thing, one can start to analyze how it functions within philosophical and theatrical discourse. The contributors to Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s anthology Monster Theory: Reading Culture, whose essays on monsters range from Frankenstein’s creation to the raptors of Jurassic Park, are united by this “insistence that the monster is a problem for cultural studies [as] a code or a pattern or a presence or an absence that unsettles what has been constructed to be received as natural, as human” (ix, emphasis in original).

Part of the puzzle is that, when studied as a theoretical concept rather than an image, the monster’s deformities may not be as visible, or as tangible, as once thought. The paradox is that a monster is recognized as a being that has features that are unrecognizable. Jacques Derrida states that the future is “necessarily” monstrous because it is unrecognizable: “[T]he figure of the future, that is, that which can only be surprising, that for which we are not prepared, you see, is heralded by a species of monsters” (qtd. in Weber 386-7). The performance of the monstrous in Capture Me is unpredictable; it is not always obvious which characters will give in to their rage and lose their human shape. Thompson was inspired to explore the theme of becoming monstrous after questioning whether rage might “simmer just under the surface of all people, especially here, in our sheltered world” (“Inspiration”). Dodge muses how, “Evil is like a riptide . . . Like a current you can’t fight,” that it is like “being pulled out to the middle of a dark sea” (11). Capture Me shows the process of becoming monstrous, instead of presenting an already established monster, in an effort to understand how transmogrification functions and why it happens.

In Thompson’s earlier work, the monster was buried within the psyche of her characters. The beast was within, but hidden. Lion in the Streets shows just “glimpses of the lions of anger and fear, repression and denial that lie in wait not just in the streets but in the abysses of the human heart” (Wasserman 259). In I Am Yours, the lion torments the imagination of the character Dee, but according to the stage directions, she wills the animal to “stay behind the wall, and not enter her being” (119). This animal is imagined to be unnatural and uncivilized. The pertinent question that Dee’s sister Mercy asks her is, “Aren’t you afraid of what your ANIMAL might do?” (144). But where the creatures in I Am Yours and Lion in the Streets haunt those plays from the edges, the monster in Capture Me does not keep a distance. According to Jerry Wasserman, Thompson’s characters have “an obsessive need to reconcile the innate violence of their unconscious life – the animal, the dark side, or whatever other metaphors she uses for the Freudian id – with their equally profound pull toward some unnameable, transcendent pole of experience” (257). Capture Me is a play about “becoming what we most fear” (Nestruck 2), as well as that “profound pull” towards an unknown experience: an encounter with the monstrous.

When Dodge asks,“Who here in this room believes in EVIL?,” it is a rhetorical question (11). One of the play’s themes is the prevalence of violence in Western society, something that is seen on the news every day (51). Therefore it is crucial to acknowledge not just that the monster is seen in Capture Me, but where the monster is presented, within human characters rather than on the periphery as an animal. Dodge philosophizes, “Radical Evil is within US. It is us.Within you and me and every human being on this earth in fact EVIL is what MAKES us human” (11). This reflects Shildrick’s statement that “monsters” or “strangers in general [. . .] may not be outside at all” (4). The monster is no longer kept outside in Capture Me, as Julie Adam writes of Thompson’s previous plays, “hovering around the periphery of civilization” (23). Instead, the monster manifests itself within the human characters on stage.

Given that Capture Me deconstructs the binary between what is human and what is monster, it is interesting to consider the transformation that Thompson herself goes through for her profession:

To write, I have to become, basically, a child who is a wild animal. The rest of the time, I am an ordinary, rather slow-witted but good-humoured woman, the kind of mother who falls asleep in front of CBC documentaries at ten fifteen every night, and does two loads of laundry before waking the kids at eight in the morning. (“Classroom” 27)

Thompson has said, “I am written in my plays, whether I want to be or not. My breath is their breath” (Turcott viii). In an interview with Judith Rudakoff, she stated that sometimes the only way for her to write characters is to act the parts out: “For instance, in I Am Yours there was a male character I was having trouble with and I thought, ‘Well, why not inhabit him for a while?’ And then I realized, suddenly, how everything should be” (“Judith Thompson” 92). However, when I asked Thompson if she had to inhabit Dodge in order to understand the type of monster that he could become, she responded, “I only inhabited the good part of him. I inhabited him during his talks [his seminars on violence] because I learned a little about Kant and radical evil and I thought,what would I like to say to these boys if I really wanted to help them and help make the world better?” (“Witnessing” 97). It was as a creative artist that Thompson found a means to cross the threshold into a monstrous state of mind:

I’ve been in states where I’ve been irrational or unreasonable. You get in an argument with someone, even a friend, and that friend asks you to just stop, you know, let’s go for a walk or something, but you’re in that mode where you can’t stop. It’s this weird altered state you get into when arguing, and it’s like you have to almost break a spell to get out of it. And I think that’s what [Dodge is] in. (“Witnessing” 97)

A “spell” is a device that Thompson uses to write about the monstrous. In order to write about transmogrification, seen as a problem in literary studies because it is a pattern with certain unrecognizable elements, she allows her creative thought process to not only incorporate, but be determined by irrational instincts. Thompson saw Dodge’s experience of becoming a monster as similar to losing a battle with alcoholism. After establishing a foundation for Dodge – his historical determination, his past fueled by his hatred for women – Thompson developed his character by allowing herself to think in a “spell,” an altered state. She thought about the forces of dependency and addiction, and how they would determine Dodge’s mood and actions.

For those attempting to fight addiction, as well as those trying to overcome trauma, the benefit of group therapy is the presence of active listeners. Susan Brison believes that in order for survivors to recover from the aftermath of violence they require an audience to listen to what they have endured. However, after her own attack, Brison discovered that although people listened to her they were unable to consistently remember what had happened to her. She came to realize that this was not a result of “ignorance or indifference, but [. . .] an active fear of identifying with those whose terrifying fate forces us to acknowledge that we are not in control of our own” (x). In rehearsals for Capture Me, the traumatic scenes were heavily workshopped in order to “articulate [the] ideas clearly, balance the play, refine and cut the ‘music’ of each scene” (“Witnessing” 98). The scenes in Capture Me are composed like music, a mnemonic method for presenting the monstrous. As Ric Knowles argues, Thompson’s work is not “conventionally naturalistic” (8). The traumatic events are recreated and reconstructed in a way that may be “fragmented and discontinuous” (8), but which is memorable. The monstrous is presented in a way that begs to be acknowledged and analyzed, and neither simplifies nor denies its mysterious chemistry.

Judith Thompson’s inspiration for Capture Me is discussed in her article “‘I Will Tear You to Pieces’: The Classroom as Theatre.” It started with a storytelling session in one of her classes. A student decided to share a story about bullying another adolescent to drastic measures, giving graphic and violent details in an attempt to entertain, or perhaps merely provoke a reaction from, his colleagues. Thompson sensed, “He was proud of what he had done.There was not a hint of any kind of regret,” and her response to this student was, “That was an excellent story; it tells us a lot about our culture” (“Classroom” 31-2). Professor and therapist Gregory K.Moffatt discusses not just violent acts in Western society, but also the language of violence, in Violent Heart: Understanding Aggressive Individuals. This is a language that may show itself in the form of “tantrums, foul language, sexual harassment, vandalism, throwing of objects, abuse of children or spouses, aggressive driving,”but also, he suggests,“perhaps merely in aggressive thinking” (viii).

When this student played the title role in a scene from Othello that they were rehearsing, Thompson recalls:

He scared the student playing Iago, and he scared me. It was as if there was lightning coursing through his body; his eyes were those of an attacking animal; his voice was like an exploding building.At one point in the scene, he, who had never broken the “fourth wall,”looked out at me, the only other person in the room, and said his line: “I will tear her to pieces.” (“Classroom” 33)

It is possible that this student was unaware of the implications of breaking the fourth wall. It is possible that this student thought if he scared Thompson, the only other person in the room and therefore his entire audience, he would be demonstrating his capability as an actor. The result was that Thompson felt like an “outsider” rather than an “authority” in her own classroom (“Classroom” 32). There was something about the element of the monstrous that resided inside him, which became visible to spectators when he was dramatizing or retelling acts of violence, that alarmed Thompson. When the student was telling the story of breaking another boy’s jaw, he became, according to Thompson,“excited by the blood” (“Classroom”31).This student left such a strong impact on Thompson that she integrated this scene from Othello into Capture Me. When Dodge encounters Jerry on her walk home from school, he describes to her how Othello “explodes with this most wonderful phrase, full of real muscular intention, ‘I will tear her all to pieces.’ So simple” (23).

Lee Strasberg, in his article “The Actor and Himself,”discusses how an actor can accomplish a great performance while insisting, “I don’t know how I do it” (623). However, Strasberg contends, an actor must find control, a balance between what is planned and what is instinctual. Strasberg refers to Jacques Copeau’s theory that an actor’s challenge has to do with “his blood.” In order to learn her characters’ thoughts, natures, and human limits, Thompson “inhabits her characters – or, as she herself has said, she stands in their blood” (Kareda 11). Thompson uses blood as a trope for one’s personality. The “battle with the blood of the actor” is a struggle between who the actor really is and the character he or she is portraying, an attempt to perform actions that he or she normally would not with a certain “ease and warmth” (Strasberg 624). Copeau brings to Strasberg’s attention a quote from Hamlet that connects acting with the idea of the monstrous: “Is it not monstrous that this player here,/ But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,/ Could force his soul so to his own conceit”? (2.2.551- 553). Hamlet further questions, “What would he do/ Had he the motive and cue for passion/ That I have?” (2.2.560-562). Is acting the ability to be excited by the thought of another’s blood, a struggle of instincts, or a monstrous thing?

Strasberg’s theory, that there are both unconscious and subconscious elements to the art of acting, suggests that theatre is a forum that has the ability to inform spectators about the monstrous. Thompson’s student addressed her with aggression, in a veiled manner, and his projects and presentations in class were always spontaneous, unprepared, and thus unpredictable. However, what she maintains is that his work “was theatre at its best. It was simply brilliant and ready for any professional stage” (“Classroom” 32). The monster, as a theatrical concept or project with both recognizable and unrecognizable elements, is compelling.

The relationship between Thompson and her student displaced her from the position of authority and upset the roles of teacher and student.When we have lost control to another, Thompson states, “we hate for our future to be in their hands” (“Classroom” 31) — a future that is, as previously noted, unpredictable, “heralded by a species of monsters”(Weber 387).This disturbing dynamic is part of “the perplexing relationships between parents and children” that “remain a central organizing principle in the deployment of [Thompson’s] characters”(Kareda 9). Capture Me is both a dramatization of the monstrous and a story of quests for parental figures gone unfulfilled. After seven years of separation, Dodge returns to Jerry with a renewed desire for her to love him, unconditionally, and care for him even though he is at his worst. Once Dodge has given in to his rage, he cannot accept a life without Jerry. But it seems that his need for a woman in his life is connected to childhood.At one point Dodge addresses his students:

I look at you and I see the perfect little boys that you once were. Perfectly sweet to your mothers, your sisters; see, the trouble is, we need them. We NEED the fair sex, not just because we need sex, but because they civilize us, don’t they? They make us better people . . . but we NEED them and that pisses us off, and so we are sometimes unfair to the women in our lives we are sometimes even … brutal. (29)

Dodge feels that he is physically dependent on Jerry, and that he needs Jerry in order to function as a human being. His desire for her to “civilize” him seems to be a yearning for discipline; Dodge wants Jerry to mother him.

Although Delphine says that she “would not be human if [she] did not respond in some way” (59) to Minkle’s request for her to meet with her daughter, she tells Jerry “I cannot bring you, fold you into my life like egg yolks into sugar, it just would not be possible” (60). Delphine asserts that she is not responsible for Jerry. She cannot anticipate how close Jerry is to danger and leaves her alone in the dark. As Shildrick states, “at the very simplest level, the monster is something beyond the normative, that stands against the values associated with what we choose to call normality […].” This is a cause of cultural anxiety, and “mothers, as a highly discursive category, have often represented both the best hopes and the worst fears of societies faced with an intuitive sense of their own instabilities and vulnerabilities” (29-30). However, the reason that Delphine is subverting the fundamental assumptions of what it is to be a mother is that she herself is transmogrifying.

A monster, in the form of cancerous cells, enters Delphine’s body and leaves her mutilated, one-breasted. This monster has taken over parts of Delphine; the “rust has spread to the brain”(52). When she refuses to accept her role as Jerry’s mother, that refusal is accompanied by the thought, “don’t think for a minute you’re going to tell her you’re dying of Cancer to get yourself a long lost loving daughter to smear Vaseline on your lips when they are cracked to to change the bed pan . . . to to sit by the bed through the night as you struggle to breathe” (52). She sees her body, itself, as monstrous. When Jerry breaks down, knows she is in danger, and screams her rage, she calls for “Mother,” the only person present and capable of saving her (62). But Dodge is able to take Jerry’s life because the monstrous is not only manifested in him, as a recognizable evil, but is in Delphine as well.

Although Jerry is abandoned by her biological mother, Aziz is a character in Capture Me who also has the potential to rescue her from her history of being an adopted child and her cycle of loneliness. He communicates his affection by telling Jerry, “I would die for you. Without question” (41), just as a parent would protect his or her young. He also scolds and lectures her in the same section of dialogue, telling Jerry to stop behaving like a child. It is established early on that theirs is not a sexual relationship; Aziz is not filling the void left by the absence of a husband, but by the absence of a mother, for whom Jerry had an “overwhelming yearning” (9). Aziz becomes glorified in Jerry’s eyes. However, the destinies of both Aziz and Delphine are defined by monologues about catastrophe. Though each finds shelter in a tree (Aziz and his daughter escape the war zone by climbing an actual tree and Delphine experiences a moment of peace reading a poem about a tree), the feeling of security is temporary, the branches are breaking.

From Aziz’s introduction, his difference is established: he comes from a place full of extreme violence; unlike most of the other parents of Jerry’s students, he works three jobs; and, he has left his country to come “knocking on the door of [Jerry’s] country”( 13). To Jerry, he is the “handsomest man [she has] ever seen in her life” (16), and he is presented to the audience as a loving parent. It is Dodge who attempts to manipulate Jerry’s perception of Aziz. When Aziz leaves her, Jerry assumes it is to “find the murderers [of his family] and bring them to justice” (45). It is Dodge who makes Aziz out to be a monster: “What do you wanna bet he got the call and he’s going to go and blow himself up.You’ll see it on the news any day Jerry. You’ll see he is NOT the SAINT you think he is” (51). Shildrick suggests:

[Once the Other] begins to resemble those of us who lay claim to the primary term of identity, or to reflect back aspects of ourselves that are repressed, then its indeterminate status – neither wholly self nor wholly other – becomes deeply disturbing. In short, what’s at stake is not simply the status of those bodies which might be termed monstrous, but the being in the body of us all. (3)

The monstrous is like a disease, and the human cannot be seen in opposition to the monster: the two bodies are not distinct. Whether it is a mental affliction or a physical illness, the monstrous is both a mutation and a mutiny, within and against the bodies and minds of Delphine, Aziz, and Dodge.When Jerry lets Dodge back into her bed one night, after Aziz has left her, it blurs the corporeal border that separates human and monstrous body; Dodge assumes that he and Jerry can blend together, like “cream and coffee,” although she tells Dodge the encounter was “a terrible fall” (54). Capture Me stages the monstrous first by showing transmogri- fication, and then ultimately by showing that what opposes the monstrous is not humanness, but forgiveness – specifically, pure forgiveness. Derrida defines “pure forgiveness” as follows: “One can only truly forgive that which is unforgiveable. If one forgives what is easily forgiven, one does not really forgive. One must forgive what is unforgiveable, and so do the impossible” (qtd. in Kirby and Kofman). To distinguish who is the monster, to dramatize where the monstrous resides, Thompson does not establish poles of good and evil, but rather emphasizes who is capable of pure forgiveness.

Jerry tells Minkle, “What Aziz and I have is pure. It’s all about [his daughter] Sharzia and poetry and here and now”(25). Although Aziz shies away from Jerry’s touch, his faith allows him to see the beauty inside her: “I don’t care about the outside. That is Western Corruption, Illusion. You have a pure and a beautiful soul” (40). Aziz’s faith continuously ties him to his home country, and segregates him from Western culture. Faith is the rationale behind everything Aziz does, but the moment that his “purity” establishes his difference is when Aziz is not able to forgive the unforgiveable; Aziz is not able to feel “pure forgiveness.” If connections are to be drawn between Dodge and Aziz, it should be acknowledged that the men are not capable of the same kind of violence. The rage that fuels Aziz is of a religious and a righteous nature; he suggests he is planning to avenge his family’s deaths, not gain revenge against a previous spouse. However, unable to rest until he does “what he must do” (49), Aziz is inextricably linked to the act of revenge which ultimately connects him to Dodge. It is Jerry, not Aziz, who attempts to forgive the unforgiveable, and who reaches out to the man who is about to kill her, insisting that she is able to love him as her friend.

In the Tarragon production of Capture Me, the other characters were separated from Jerry by a scrim at the back of the stage as the monster approached her. They existed as figments of Jerry’s dream or imagination, shouting to her in poetic, fragmented dialogue. Minkle begs Jerry to “tear [Dodge’s] fucking throat out or die trying”(65). Instead, Jerry attempts to save Dodge; she tells him that she loves him, as her friend, and she offers him her hand. Forgiveness has appeared in the final scenes of previous plays by Thompson. In I Am Yours, “Toilane and Dee search and beg for forgiveness in the final scenes [. . .] and are rewarded with transfiguration” (Kareda 13). Similarly, at the end of Lion in the Streets, Isobel forgives Ben and “ascends, in her mind, to heaven” (288). Like Jerry, who demonstrates that she is capable of both rage and compassion, Isobel ultimately “resolves the battle between ‘the forces of vengeance and forgiveness warring inside her’”by offering love to her aggressor (259). In Capture Me, Jerry forgives Dodge at the very moment that he is about to kill her and therefore before he is able to commit the unforgiveable act. She is still able to see him as human: “You are not the devil there is no devil there is you” (65). Thompson explains:

If you force yourself to see the monster within the human, then the theory is [he] becomes human, like in a fairy tale. Like kissing the frog. But the trouble is, that’s what we wish could happen, but that’s not the immediate reality. Now, we can talk about dead bodies on stage, but this is a redemptive moment, because in a way it’s our only hope for the world. If we can all see each other as human. (“Witnessing” 99)

After Jerry’s death, the play ends with a scene in which Jerry and Minkle are in a car, driving away. Jerry speculates to Minkle, “maybe I am dead. And that this is the dream, like a dream right before I putrefy” (67). Capture Me is a dramatization of this moment, right before the body transforms, becomes or transmogrifies. It is a play that problematizes the standard definition of monster by revealing the disadvantages of a society that is conditioned to believe that we can see, or recognize, a boundary that protects the self from the monster. When Thompson deconstructs the categories of victim and perpetrator, she shows that both good and evil can exist, and perhaps do exist, in everyone. In an interview with Eleanor Wachtel, Thompson said,“I think each character in my play is a sort of microcosm for the whole culture, because there is evil and good warring in the culture at all times. And I do think it’s in every human being” (“An Interview” 39). As well, as Cynthia Zimmerman states, the work of Judith Thompson presents “what our unconscious already knows: that much of what there is to be afraid of resides in our own human nature” (190). When she is writing, Thompson may turn into a wild animal, but she is also a mother and a teacher who questions how to keep calm and order, and she is also a theatre practitioner striving to produce the most dramatic outcome. Capture Me communicates the monstrous by staging transformation. According to Susan Brison: “[B]earing witness to traumatic events not only transforms traumatic memories into narratives that can then be integrated into the survivor’s sense of self and view of the world, but it also reintegrates the survivor into a community, re-establishing bonds of trust and faith in others” (Brison xi).

Capture Me explores whether stopping transmogrification is as simple as maintaining one’s human shape, not becoming like “playdoh” when in the hold of an emotion (57). Dodge says to his young male students, “You poor guys, you are nothing but pawns; your violence is so over-determined you didn’t have a chance” (45). But in the “ghastly game”in which Brison found herself,“in which some men ran around trying to kill women, and others went around trying to save them,” it was she, the victim, who felt like a pawn (Brison 90).Her body sustained multiple head injuries and a fractured trachea, the visible symptoms of a much deeper and lasting shattering of the self. What Shildrick claims one can learn from the study of the monstrous is “not a matter of denying that the medium of the body has reality, but of affirming that there is no essential corpus upon which meaning is inscribed” (120). Brison’s body would heal, but she had to remake her sense of identity in the aftermath of trauma. Capture Me theatricalizes, in a series of seminars, spells, and confrontations, the language and practice of the monstrous, transmogrification rather than an established monster. If the reality, as Dodge puts it, is that,“every person in this world has become a monster at one time or another” (45), then the perpetrator and the victim, the human and the monster, the separate pieces of the “ghastly game” in which Brison found herself, are not in opposition. As in the very earliest records of monsters and their meanings, the boundaries are blurred, the lines on the game board are not definitive. The monstrous is a problem to which the philosopher, the scholar, and the playwright can only respond with more questions, rather than definitive solutions. One question, rather than who should be captured, is what to counsel within ourselves, in order to end the game.

NOTES

1 Bateman, Stephen. The Doome Warning All Men to the Iudgemente:

Wherein are contayned for the most parte all the straunge Prodigies

hapned in the Worlde. London: Ralph Nubery, 1581.

Return to article

WORKS CITED

Adam, Julie. “The Implicated Audience: Judith Thompson’s Anti- Naturalism in The Crackwalker, White Biting Dog, I Am Yours and Lion in the Streets.” Women On the Canadian Stage: The Legacy of Hrotsvit. Ed. Rita Much. Winnipeg: Blizzard Publishing, 1992. 21-29.

Brison, Susan J. Aftermath:Violence and the Remaking of a Self. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2002.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome, ed. Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minneapolis: U ofMinnesota P, 1996.

Dick,Kirby, and Kofman, Amy Ziering, dirs. Derrida. New York: Zeitgeist Films Ltd, 2002.

Kareda, Urjo. Introduction. The Other Side of the Dark. By Judith Thompson.Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 1989. 9-13.

Knowles, Ric. Introduction: “The Fractured Subject of Judith Thompson.” Lion in the Streets. By Judith Thompson. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 1992. 7-10.

Moffatt, Gregory K. A Violent Heart: Understanding Aggressive Individuals. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2002.

Nestruck, J.Kelly. “Dark lady: Judith Thompson’s plays take on the flip side of sweetness and light.” The National Post. 3 January 2004. Canada.com News. 5 January 2004. http://www.canada.com/components.html

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare Complete Works. Eds. Richard Proudfoot, Ann Thompson and David Scott Kastan. London: Thomson Learning, 2001. 291-332.

Shildrick, Margrit. Embodying the Monster: Encounters with the Vulnerable Self. London: SAGE Publications, 2002.

Strasberg, Lee. “The Actor and Himself.” Actors on Acting. New York: Crown Publishers, 1970. 623-28.

Capture Me. By Judith Thompson. Dir. Judith Thompson. Perf. Randi Helmers, Tom McCamus, Nancy Palk, Chick Reid and Maurice Dean Wint. Tarragon Theatre, Toronto, ON. 30 December to 8 February 2004.

Thompson, Judith. Capture Me. Tarragon Theatre, Toronto, ON. Unpublished Script. 10 January 2004.

---. “‘I Will Tear You To Pieces’: The Classroom as Theatre.” How Theatre Educates: Covergences and Counterpoints. Eds. Kathleen Gallagher and David Booth.Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003.

---.“Inspiration for Capture Me.” E-mail to Robyn Read. 22 Oct. 2003.

---. “Judith Thompson Interview.” By Judith Rudakoff. Judith Rudakoff and Rita Much. Fair Play: 12 women speak: Conversations with Canadian Playwrights. Toronto: Simon and Pierre, 1990. 87-104.

---. “An Interview with Judith Thompson.” By Eleanor Wachtel. Brick: A Literary Journal 41 (Summer 1991): 37-41.

---. “I Am Yours.” The Other Side of the Dark. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 1989. 115-176.

---. “Lion in the Streets.” Modern Canadian Plays Volume Two. Edited by Jerry Wasserman.Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2001. 261-288.

---. Personal Interview. 24 March 2004. University of Guelph, Guelph, ON.

Turcott, Iris. Introduction. Habitat. By Judith Thompson. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2001. viii.

Wasserman, Jerry. “Judith Thompson.” Modern Canadian Plays Volume Two. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2001. 257-260.

Weber, Elizabeth, ed. Points . . . : interviews, 1974-1994. Jacques Derrida. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1995.

Zimmerman, Cynthia. “Judith Thompson: Voices in the Dark.” Playwriting Women: Female Voices in English Canada. Toronto: Simon and Pierre, 1994. 176-209.