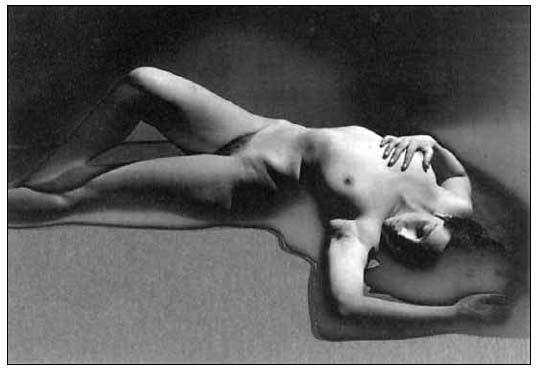

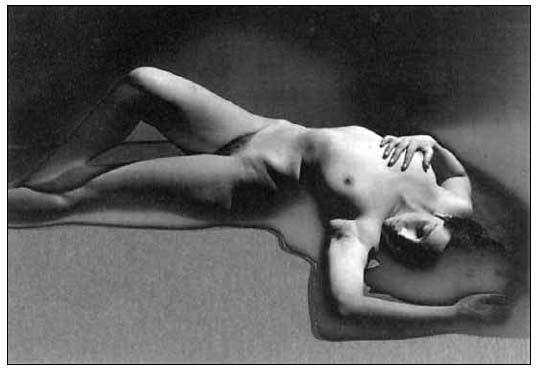

Man Ray, The Primacy of Matter over Thought (1929) © 2004 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

LAURA LEVIN

Cet article examine l’expérimentation avec la forme naturaliste que l’on retrouve dans les pièces de Judith Thompson. L’auteur suggère plusieurs moyens par lesquels Thompson radicalise l’esthétique naturaliste et expose les aspects du genre qui sont habilitants sur le plan politique. L’oeuvre de Thompson fait ressortir les affinités refoulées entre le naturalisme et le surréalisme, deux mouvements qui mettent à l’épreuve les limites poreuses de l’égo et de l’environnement. Raymond Williams y voyait une caractéristique clé du naturalisme de haute intensité dans lequel l’environnement «sature» la vie des personnages. Les pièces de Thompson donnent une forme littéraire à ce naturalisme «imprégné» à l’excès en présentant des personnages qui deviennent sursaturés sur le plan linguistique et physique par leur environnement. Explorant les possibilités de la «représentation du terrain» en faisant du corps une co-extension de son entourage matériel, Thompson imagine une autre éthique de la rencontre entre le soi et le monde. En même temps, elle complique l’acte de la représentation du terrain en montrant comment la figure féminine est devenue synonyme de l’espace lui-même.

Many students shudder when they hear the term: “Naturalism.” It is the dirty word uttered at the beginning of modern drama courses, stirring up feelings of boredom and resistance. These knee-jerk reactions stem from a contemporary North American bias, promoted by academics and artists, which aligns naturalism with the static, the unthinking, and the un-dialectic. When approached from this critical perspective, naturalism often fails to make the cut-off for membership in the twentieth-century avantgarde. In fact, the very idea of an “avant-garde” comes into being through a repudiation of naturalism and its reactionary conventions. Presented as the antecedent to a century of modernist and postmodernist innovation, naturalism has become the scapegoat for the standard dramatic literature syllabus. It is the foil needed to understand Brecht, or the topic that must be suffered through before getting to the “good stuff” – to the plays that invite artistic, political, and philosophical transformation.

Since its inception in the nineteenth century, playwrights have experimented vigorously with the forms and conventions of naturalism. A number of stylistic variants immediately come to mind: the super-naturalism of Eugene O’Neill, the feminist and symbolist naturalism of Susan Glaspell, and the absurdist naturalism of Sam Shepard. While extraordinarily diverse in form, these works often unsettle common assumptions about the meaning of naturalism and its intrinsic conservatism. Judith Thompson’s plays offer some of the most striking examples of this kind of theatrical innovation. In this essay, I will suggest several ways in which Thompson radicalizes the naturalist aesthetic, exposing the experimental and politically enabling aspects of the genre. Specifically, through her use of space and visual form, she draws out disavowed affinities between the naturalist project and that of the early surrealist avant-garde. I hope to illuminate the feminist implications of locating Thompson’s work within this twinned lineage, marking the ways in which she genders key spatial concepts in surrealist art. Instead of viewing her plays as yet another departure from naturalism, I will explore the theoretical advantages of positioning them within the naturalist rubric. When read from this perspective, not only do Thompson’s plays expand our understanding of the naturalist project, but they also serve as powerful attempts to draw out naturalism’s unrecognized possibilities. Naturalism emerges as a dramatic form with significant ethical potential, one capable of reimagining traditional self-environment relations.

There is already a large body of work that offers a range of rich perspectives on Thompson’s plays. Critics tend to begin by situating Thompson’s plays in relation to naturalist traditions. Few critics, however, are content to define her work as simply naturalist. For some, this definition falls short since Thompson continually puts reality in quotations. Julie Adam calls her work anti-naturalist, pointing to Thompson’s persistent use of anti-illusionist and Brechtian devices. Thompson’s anti-naturalism brushes up against “the ostensible subject matter of her plays – human suffering, both physical and psychological, especially of the so-called underprivileged” (22). This subject matter, Adam argues, leads spectators to mistake her plays for “slice of life studies”(22). Critics like Robert Nunn and Jennifer Harvie define Thompson’s work less in terms of an artistic break than as an expressive form of naturalism. This style opens the texture of realism to surrealism, and to the realm of fantasy and dream. Ric Knowles uses the term “poetic” naturalism to define Thompson’s technique, pointing to the lyrical style that she has cultivated in residence at Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre (7). Thompson privileges this latter frame, describing her style in similar terms as an “emotional naturalism” (Fletcher 39). The word “emotional” gestures toward the outpouring of psychic and bodily contents in the typical Thompson play. Approaching the terrain of expressionism, emotional naturalism suggests a blurring of internal and external reality staged across the sensate body.

In many readings of Thompson’s work, especially those offered by critics that call her plays anti-naturalist, the “real” serves as the most prominent index of the naturalist aesthetic. These interpretations rely, in other words, on the widely popularized definition of naturalism as an artistic method of truthfully reproducing reality. This definition is influenced by the traditional alliance of naturalism with nineteenth century methods of scientific empiricism. In his essay on the form, Raymond Williams argues that the dominant usage of the word naturalism – as the “accurate or lifelike reproduction of character, action, or scene” (205) – is both limited and limiting. He contends that it has allowed artists “to claim that they have abandoned, ‘gone beyond’, naturalism, when it is clear […] that many ‘non-naturalist’ plays are evidently based on naturalist philosophy” (222). This enduring naturalist tendency might be better understood if we attend to what Williams sees as the less elaborated sense of naturalism – a profound interaction between character and environment. The presence of an environment that forcefully influences character goes well beyond the definition of naturalism as the presentation of “‘permanent’ human characteristics in an accurately reproduced natural or social ‘setting’” (205). Describing the symptomatic relationship between human and environment in high naturalism, he writes:

It is a question of a way of perceiving physical and social environment, not as setting or background through which, by other conventions, of providence, goodwill, freedom from prejudice, the characters may find their own ways. In high naturalism the lives of the characters have soaked into their environment. Its detailed presentation, production, is thus an additional dramatic dimension, often a common dimension within which they are to an important extent defined. Moreover, the environment has soaked into the lives. The relations between men and things are at a deep level interactive, because what is there physically, as a space or a means for living, is a whole shaped and shaping social history (217; emphasis added).

In this passage, Williams offers a particularly suggestive reading of the environmental processes that are often at work in naturalist drama. These processes are too easily overlooked when critics move to dismiss naturalism as an inherently conservative genre. Williams presents us with a naturalism that undermines the traditional boundaries of the individual – the bourgeois figure that dominates this form. Character is imagined as a decidedly porous entity, making the individual’s claims of personal distinction a significant problem.

Williams’ articulation provides another way into the naturalist world of Thompson’s plays. If her work approaches the style of naturalism, it does so most evocatively through its presentation of environment. As in many conventional naturalist dramas, Thompson presents the meeting of individual and environment as a site of complex entanglement. In fact, Thompson takes Williams’ definition one step further by literalizing his idea of a “soaked” naturalism, presenting us with characters that become linguistically and physically oversaturated in their environments. Her plays extend the naturalist project by showing us that the separation between human and environment, figure and ground, cannot be perceptually sustained.

So what does this over-saturation look like, and what alternate interpretive lenses does it offer? Thompson’s plays usually specify particular Canadian environments as their settings. These sites range from the urban slums in Kingston to small towns like Marmora to posh neighborhoods in Toronto. Guided by the first sense of naturalism – naturalism as objectivist verisimilitude – we might read these environments as reproductions of everyday locales familiar to Canadian spectators. Read this way, the environment remains merely a recognizable setting in which the action takes place. There is nothing here that is remotely destabilizing to the spectator’s habits of perception. But Thompson’s plays seem somehow closer to Williams’s definition, with the environment refusing to stay in the background. It aggressively seeps into the lives of the characters, disallowing the expected delineation of human from surroundings.

This over-saturation is figured through Thompson’s exorbitant references to local detail. Revealing what Williams calls a deep interactivity between people and things, her characters constantly engage with the minutiae of Ontario consumer culture: “Horny Tim’s” or Tim Hortons donut shops, Timbits (miniature round donuts made from donut “holes”), Coffee Time stores, Export A cigarettes, the Eaton’s Centre, Mapleview Lanes (a fusion of Ontario’s shopping malls Mapleview Centre and Hazelton Lanes). In this landscape of commodities, the consumption of brands is conflated with the gratification of physical needs. Making a connection between Williams’s “saturation” and bodily satiation, the local is literally consumed, or taken into the body. Characters engage in excessive bouts of donut eating at local stores (Theresa in The Crackwalker, Rhonda in Lion in the Streets) and, even more tellingly, satisfy other appetites at the same franchises (Joe in Crackwalker: “we’d […] pick up some juicy pie down at Lino’s or Horny Tim’s, drive it out to middle road, fuck it blind, and have em home by one o’clock,” 36). Commodities become stand-ins for individual characters, casting doubt on their singularity and the originality of their desires.

References to the geographic particular perform a hyperlocality that disrupts the conventional separation of figure and ground. According to Rem Koolhaas, the “hyper-local”manifests itself in overly literalized depictions of local culture. Koolhaas sites the hyper-local in places like airports, where encounters with “a drastic perfume demonstration, photomurals, vegetation, [and] local costumes give a first concentrated blast of the local identity” (1251). Thompson presents us with a similarly concentrated blast of the local through obsessive and repetitive descriptions of environment that linguistically produce setting as a field of unmitigated excess. This technique structures Habitat, Thompson’s recent play about the opening of a group home for troubled adolescents in the wealthy neighborhood of Mapleview Lanes. Consider, for example, this exchange between two of the home’s new residents, Sparkle and Raine, which offers a superabundance of environmental detail:

SPARKLE. What’s the name of this street anyway? It’s like something out of fucking Pleasantville.

RAINE. Mapleview Lanes…

SPARKLE. (laughs hysterically) That’s hilarious! MAPLEVIEW LANES!! AGHHHH! I love it. I just LOVE those NAMES of any development built from the sixties on? Like ahhh ‘Fairfield Estates’ or Winchester Woods or or Birchmeadow Crescent All EXCLUSIVE LIFESTYLE LIVING EXCLUDING the likes of US, right? (37)

Sparkle’s rant moves in and out of capitalization, in and out of punctuation, mirroring the negotiations of self in relation to the environmental field. As in Koolhaas’ hyper-local airport displays, references to “Pleasantville” and to cookie-cutter housing developments for the elite point to the simulacral realm of consumer culture. To rephrase Williams’s claim slightly, the environment becomes an entity that humans consume and in which they are consumed. More importantly, we are not presented with an authentic reproduction of an upper class Toronto neighborhood. Just as the costumes displayed in Koolhaas’ airport rarely resemble those worn by city locals, Sparkle’s description yields no “true” picture of Toronto. The setting is rather like Pleasantville, a site of mimetic and capitalist excess.

In Habitat, as in other Thompson plays, the hyper-local is often produced through textual form. It surfaces in overdrawn and redundant lists of names and adjectives,which enmesh the speaker in illuminated context and present the setting as more than background. This technique appears in the first speech delivered to Mapleview residents by Lewis Chance, the director of the group home. Providing more context than is needed (or desired) by his audience, Lewis refers to Mapleview Lanes as “exclusive,” as “fantastically beautiful [and] tree-lined,” and, more emphatically, as “one of the finest neighborhoods in Etobicoke, a neighborhood of accomplished and distinguished and really well-dressed, well shod people” (10). This uncanny use of repetition and over-saturation in environmental detail is profoundly unsettling to the stable frame of reference through which we try to comprehend the play. When watching conventional naturalistic dramas, we turn to the context to gain a sense of narrative coherence. Here, however, the context seems somehow too contextual, denying us stable grounding in relation to it.

Thompson’s approach, which replays the naturalist orientation in excess, recalls a similar set of operations at work in the aesthetics of surrealism. This movement, unlike naturalism, is still considered experimental and avant-garde. Thompson’s spatial techniques remind us of those surrealists who attempted to break down perceptual boundaries between self and environment, between the ego and external objects. To achieve this end, they created numerous images in which bodies merge with their natural or built environments. Some famous examples of this motif can be found in the work of surrealist photographer, Man Ray. In Man Ray’s The Return to Reason (1923) we are presented with a female torso that is formally drawn into its setting. A series of shadows, emanating from furnishings in the room, are cast onto the woman’s body. In another image, The Primacy of Matter over Thought (1929), a reclining nude recedes into the floor, her physical extremities melting into a thick liquid.

The negotiation between body and environment is especially pronounced in works created by women affiliated with the surrealist movement. In her self-portrait Roots (1943) Frida Kahlo presents her body as an extension of the earth, her arteries affixed to the roots in the ground. In this reciprocal exchange, the environment becomes a character in its own right, assuming human-like traits. Lenora Carrington’s Self-Portrait (1938) provides another example of this phenomenon. In this image, the artist mimics the forms of her furnishings and the furnishings mimic her in turn. As Helaine Posner explains, Carrington shows us “a curiously anthropomorphic chair [which] sprouts the delicate hands and booted feet of its striking artist-occupant” (158). Later surrealist artists, including Francesca Woodman, continue in this tradition, experimenting with visual processes that disperse the subject within an environmental field. In her photograph House #3 (1975-76), Woodman uses a long exposure to generate a blurry image of her body that creates the impression that she is dissolving into her domestic surroundings.

Like Thompson’s plays, these images can be read in relation to surrealist theories of space. They recall, first of all, the writings of Roger Caillois, who explored the processes by which organisms blend into their natural environments. Through camouflage, he explained, an insect mimics the forms of its physical setting. Responding excorporatively to the formal patterns of its background, this being can no longer claim to be “the origin of [its] coordinates, but one point among others”(Caillois 28). Rosalind Krauss notes the effects of this spatial mimicry on human and animal subjects: “The life of any organism depends on the possibility of its maintaining its own distinctness, a boundary within which it is contained, the terms of what we would call self-possession. Mimicry, Caillois argues, is the loss of this possession, because the animal that merges with its setting becomes dispossessed, derealized”(“Corpus”74).

Caillois’ theory of spatial mimicry points to a fundamental concept of surrealism: the notion of the informe, usually translated as the “formless”or the “un-formed.” Coined by Georges Bataille, the informe resists the circumscription of matter within a definite form. “All of philosophy has no other goal,” Bataille writes, “it is a matter of fitting what is there into a formal coat, a mathematical overcoat” (qtd. in Hollier 16). The informe, however, cannot be understood as the opposite of form. As Hal Foster argues, the informe is a set of operations, a process through which “significant form dissolves because the fundamental distinction between figure and ground, self and other, is lost” (112). In this sense, the informe is posed as a challenge to dualistic Cartesian thinking, which positions man as a delineated figure standing over and against his environment in a relation of disembodied and vertical mastery.

By reading Williams’s account back through surrealist conceptions of space, a different picture of Thompson emerges, one that resists the simplistic alliance of surrealism with anti-naturalism. Thompson’s play I Am Yours provides the clearest example of the surrealist approach to environment. The informe is represented scenically through the dissolution of physical and psychic boundaries. A series of architectural borders are erected to keep the human subject separate from external entities that threaten self-disaggregation. The central character, Dee, senses that there is an animal hiding behind the wall, which periodically breaks free and inhabits her body. As Robert Nunn points out, the divisions that Dee establishes between internal and external worlds, between self and desire (the animal),were built into the designs for the Tarragon productions (1984, 1987). As in other stagings of Thompson’s plays, these sets were “multileveled,” calling attention to “vertical and horizontal dimensions and to walls and partitions between one part of the set and another” (4). Like the surrealists, Thompson reveals these divisions to be illusory. Dee can no more restrict her desires than she can control which elements from the outside world filter into her body. She makes this clear when confiding in her sister: “It’s like [the animal] got out of the wall. Like a shark banging at a shark cage and sliding out. Out of the wall and inside me. I feel something taking over” (140).

Thompson presents character as a porous scrim, one which is not only, as others suggest, open to the forces of desire, but is also open to the nonhuman environment. This porosity makes sense in I Am Yours. It is arguably Thompson’s most overtly surrealist play, its action wavering in and out of dream. But a porous dramaturgy also emerges in plays that seem more naturalist, reminding us that the co-saturation of self and world is a shared preoccupation of these stylistic approaches. Sled, one of Thompson’s “grittiest” plays, immediately comes to mind. In Sled, the deep snow of the Canadian North appears to consume the characters. The snow has not only soaked into the characters’ lives; the characters are actually sinking into the landscape.

In the first scene, Annie is immersed in the wilderness of northern Ontario. The stage directions describe this spatial enmeshment: “White birches, snow, a Great Snowy owl, and a trail, with a hill, running around behind or through the audience. ANNIE appears walking fast and hard, out of breath through deep snow and birches” (19). Unlike Dee, Annie seeks out a connection between her body and the landscape, even to the point of courting her own erasure. “Oh heavenly time of day,” she sings, “the snow and the quiet/ the birch/ white pine/ so high and so high/ Shall I sink in the snow and just lie there for hours/ alone there for hours/ till dark night erases me?” (19). As part of her bond with the external world, Annie develops strong relationships with non-human entities. Recalling Kahlo’s famous image in which she presents herself as part woman and part deer (The Little Deer, 1946), Annie identifies with the animals that she encounters. In her performance at the lodge, she tells a story of exchanging knowing glances with a fox. At a formal level, her body sympathizes with this animal. Her “beautiful red dress with long red velvet gloves”(23) mirrors the fox’s luxurious and velvety red coat.

The interconnectedness of human and environment is almost always registered in ethical terms. In Sled, Annie’s openness to the physical world is opposed to the brutalization and objectification of women, animals, and nature. Conversely, qualities of goodness and affect are metaphorized through unions of the human and the nonhuman. In Habitat, Lewis compares his devotion to the group home residents with the loving actions of a maple tree. Reminding us of Khalo’s Roots, he tells Raine that his house is the tree trunk: “strong and firm holdin’ all of you, my family, my girls and boys, all of you up, and the roots? The roots they go deep deep into the ground, right? And they spread far and wide and they drink of the groundwater the groundwater is the love we all have for each other, eh?”(27).

Of course, as is characteristic of Thompson’s writing, which works to undo philosophical binaries, her plays track contradictions and anxieties produced by this ethical position. The collapse of human-nature distinctions is attended by a range of potential dangers that she does not attempt to explain away. Annie, for example, is killed when two men are hunting for moose. At first, they are unable to distinguish Annie from the landscape. The stage directions read: “The snowmobile’s light beams on her. There are birches between her and the snowmobile. There is a stand of birches blocking their view of her” (37). Even when a clear view of Annie emerges, Kevin chooses to see her as a “she-moose,”and shoots her down (a possible act of revenge for his humiliation by her husband). Indeed, violence is often the result of behaviors that threaten to do away with self/other distinctions altogether. Lewis’ attempt to shelter his children flips over into a stubborn authoritarianism when confronted with the unruly actions of individual residents or, more specifically, when his idyllic image of the group home fails to cohere. In such cases, the words used in his maple tree analogy – “strong and firm holdin’ all of you” – accrue a disturbing double-meaning.

As human figures become enmeshed in complex ways with their environments, the background insistently takes on a life of its own. Here we might say, following Williams, that Thompson’s environments do not appear as “illustrative settings” (217), but rather as “integral parts of the dramatic action, indeed, in a true sense, [as] themselves actors and agencies” (205). This is most apparent in The Crackwalker, in which the menacing urban environment encroaches upon the domestic space. Alone in her apartment, Sandy stays up nights in terrible fear listening to the sounds of the street (cats screaming, the thud of footsteps). At times the background is transformed into a figure: Charlie Manson, the monster she calls the Crackwalker, and the “Indian Man” roaming the streets.Vomiting and bleeding, this aboriginal character literalizes – not unproblematically – the condition of the informe and embodies the landscape of desperation in the play. In effect, he becomes synonymous with the environmental ground itself. The stage directions call for the Man to sit in a ground-ed position; he is situated on the “warm air vent” that is a central feature of the street space (68). Adam reports that in the 1990 Tarragon staging the Man “sprawled diagonally” on the set and remained in this position “for some time after one of his encounters with Alan”(20). Physically tied to the material properties and horizontal axis of the street, the Man is presented as a morphological extension of the urban space.

Yet the formal treatment of this raced and emphatically feminized figure points towards a more complex strategy in Thompson’s works, one that has not adequately been accounted for. As I have suggested, Thompson presents the interpolation of self into setting as politically and ethically enabling. In this respect, the process of backgrounding serves to undermine the individual subject’s will to mastery and claims of self-possession. However, Thompson complicates this process by illuminating the ways in which women and other feminized persons have historically been obliterated as background or have been made synonymous with space itself. As Shannon Jackson argues, female characters are all too often represented as “the place” and men as “the people.” In such cases, women become the “providers of ‘ground’ on which male self-figuration occurs” (700). Jackson explains: “To perform ‘ground’ in [a] theatrical scenario is to engage in a repetitive and circumscribed network of motions (in kitchens, in station wagons, in gardens) that are essential to the cultivation of spatial comfort” (700). While “performing ground” may be a feminized act, it is not particular to women. As Thompson illustrates in her formal treatment of the Man in The Crackwalker, non-white, queer, and lower class characters frequently stand in as background as well.

In Thompson’s plays, acts of performing ground take place along vertical and horizontal axes, reminding us of the spatial operations of the informe. Rosalind Krauss contends that the informe counters the logic of the vertical – the gravitational pull of figure away from ground or the moment when man stands up and separates himself from the brute materiality of nature. In a Lacanian sense, the vertical plane has been associated with “the hanging together or coherence of form […] the very drive of vision to formulate form, to project coherence in a mirroring of the body’s own shape” (“Cindy”130). The informe, however, envisions a different organizational and bodily schema. Its figures are perpetually “falling from the vertical into the horizontal” (Optical 156), from self-cohesion into self-dissolution.

Thompson uses this vertical/horizontal axis as the basis for her environmental imagining. Unlike Krauss, however, she draws out its gendered and classed implications. In Crackwalker, for example, Sandy is tied to the horizontal space of her apartment. Labouring to fit the role of the traditional housewife, Sandy is obsessed with the cleanliness and orderliness of the domestic space. She is in contact with the ground when we first meet her, “scrubbing the floor furiously” (20). Later on, we find that Sandy is still preoccupied with the ground. A stage direction tells us: “She picks something up off the floor and starts to take it into the kitchen” (30). Almost immediately afterwards, she finds herself falling back into the horizontal. The next direction reads: “JOE [her abusive husband] grabs her as she tries to pass him and throws her to the floor” (30). Standing over her, he screams: “You CUNT” (30). As in other Thompson scenes, falling into the horizontal is tied explicitly to violence against women (often to rape) and the phallocentric definition of woman-as-body.

This visual scheme, which sutures feminine and feminized bodies to the horizontal floor space, is a central dramatic element of Habitat. Janet, one of the wealthy residents of Mapleview Lanes, fears that her widowed mother is slowly being consumed by the mounds of dirt piling up in her house. She warns her mother that her body will disappear into the ground:

MUM. Really. Just… I mean… look around you. Please. These floors – you have not swept the floors since he died. Have you? I mean ... what is this white dust? That is you, your skin, all over the floor, as if you were, I don’t know, ROTTING in here, and one day, I’ll come in and you will be just dust.(15)

Since Janet is a called a feminist, we might read this statement as a plea directed towards her mother, and to women in general, to move from the position of ground to figure. But Thompson complicates this solution by showing us how this move would only leave the figure/ground binary intact. It does little to register the ways in which all scenes are structured through infinitely receding backgrounds. In Habitat, that other “ground” is the working class. Janet counsels her mother to liberate herself from the home while, at the same time, consigning other women to the status of ground: “you need, you DESERVE a cleaning lady, Mum. Listen, Peggy Creese does wonderful work for me – she gets down on her hands and knees . . . and and scrubs till you can see your face in the FLOOR” (14).

By showing us the hidden ground-work of maintenance, Thompson draws out and politicizes another aspect of naturalism. As August Strindberg once wrote, “the true naturalism […] seeks out those points in life where the great conflicts occur, [and] rejoices in seeing what cannot be seen every day” (qtd. in Williams 213). Thompson reveals what might be called the environmental unconscious, showing the lower classes to be the invisible constitutive ground that props up the affluent of Mapleview Lanes. Margaret and Janet turn a blind eye to this ground as they engage in a legal battle to have their underprivileged neighbors removed from their community. These adolescents are treated as mere extensions of the amorphous and non-figural class that maintains the property value of Mapleview Lanes and provides the conditions for “spatial comfort” (Jackson 700). In Sparkle’s words, the group home teens are “the writhing seething k-mart masses, who mow your lawns and clean your floors and do your hair and your nails and sew your hems” (68). Once again, an obsessive list of domestic details appears, making clear what is so deeply troubling about this form of contextuality. As Naomi Schor reminds us, the “most threatening [thing] about the detail” is “its tendency to subvert an internal hierarchic ordering of the work of art which clearly subordinates the periphery to the center, the accessory to the principal, the foreground to the background” (20).

This hierarchical reordering was visualized in the set created for the Canadian Stage Company’s production of Habitat, which featured a large area of grass, with Margaret’s living room located in one corner and Lewis’s group home at another (Hoile). By situating Lewis and Margaret’s homes on the shared grass area (an element of the set which itself had few spatial demarcations), the design signaled the artificiality of classed boundaries and established a visual connection between the geographies of their respective social spheres. The set thus withheld those visual cues that would, in a traditional naturalist (or bourgeois) set, demarcate the margins from the centre and the private from the public. In a more general sense, I want to suggest that the formal openness of this kind of design can allow for a use of space in naturalist theatre that foregrounds the complex entanglements of self and other, figure and ground, that I have been trying to trace. Not only are these categories shown to be formally interdependent, but their separation also appears socially contingent, predicated upon a range of gendered, classed, and raced fictions.

Ultimately, it is this intrinsic spatial dependency that serves as a basis for the radical ethics opened up by Thompson’s work. This environmental relation is not defined by individualistic self-delineation and Cartesian self-possession. Rather, following the explorations of naturalist and surrealist artists, it embraces the possibilities of breaking down divisions between body and external world. The notion of “world” that operates in Thompson’s plays is necessarily expansive; it encompasses all of those environments – natural, commercial, social – in which we are implicated and to which we are ethically responsible. Using a dramatic form that often pits the individual in antagonistic relation to its environment, Thompson re-figures the naturalist character as a being that is sensuously linked to the bodies of its neighbors. The failure of self/environment distinctions is signaled throughout her plays in the deliquescence of physical forms and boundaries.We hear of amniotic fluid trickling, honey pouring, snow falling, and stone walls breaking apart. This imagery of oozing, of liquid emission and spatial collapse, hints at an inescapable porosity of self to world. Unlike Posner, who reads the porous as an example of the surrealist impulse to “dissolve difference” (158), Thompson shows this formalist maneuver to be untenable and undesirable, reminding us that social differences are in fact the precondition for an ethical encounter with the other. In her porous approach to character, Thompson respects alterity by permitting us to imagine selfworld relations as an incessant transference between separate yet indistinct entities.

Porosity, of course, does not come without dangers. Openness to the other can lead to asphyxiation, penetration, and even engulfment. This is intimated in the German poem found in I Am Yours: “You are locked in my heart/ The key is lost/ You will always have to stay inside it…/ For always” (157). Yet, as the play’s title makes clear, this position is reversible. The words I Am Yours signal both the threat of captive possession and a productive relinquishing of self-mastery. Even more poignantly, it points to the risks and promise inherent in the naturalist project. The naturalist model of environment has, after all, operated in a similarly possessive mode, claiming the subject within a deterministic schema that squashes the prospect of social change. Yet, as Thompson’s plays make clear, the co-saturation of subject and setting need not always be understood in deterministic terms. In applying this reading, we frequently misrecognize as determinism moments in a text that might otherwise be seen as a fruitful interconnection of human and environment. By experimenting with the formal parameters of naturalism, Thompson allows a more productive self-world relation to come into view, one which counters the traditional exclusion of the subject from the material world. Thompson’s work, finally, asks us to locate ourselves inside naturalism and vigilantly embrace our enmeshment in a matrix of worlds that we can make and of which we are made.

WORKS CITED

Adam, Julie. “The Implicated Audience: Judith Thompson’s Anti- Naturalism in The Crackwalker, White Biting Dog, I Am Yours, and Lion in the Streets.” Women on the Canadian Stage: The Legacy of Hrotsvit. Ed. Rita Much. Winnipeg: Blizzard Publishing, 1992. 21-29.

Caillois, Roger. “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia.” Trans. by John Shepley. October 31 (1984): 17-32.

Fletcher, Jennifer. “The Last Things in the Sled: An Interview with Judith Thompson.” CTR 189 (Winter 1996): 39-41.

Foster, Hal. “Obscene, Abject, Traumatic.”October 78 (Fall 1996): 107-124.

Harvie, Jennifer. “(Im)Possibility: Fantasy and Judith Thompson’s Drama.” Onstage and Off-stage: English Canadian Drama in Discourse. Eds. Albert-Reiner Glaap and Rolf Althof. St. John’s Newfoundland: Breakwater Books, 1996. 240-256.

Hoile, Christopher. “Habitat is a Shambles.” Stage Door. 2001. http://www.stage-door.org/ reviews/misc2001g.htm

Hollier, Denis. Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1989.

Jackson, Shannon. “Partial Publicities and Gendered Remembering.” Cultural Studies (Fall 2003): 692-712.

Knowles, Richard Paul. “Introduction: The Fractured Subject of Judith Thompson.” Lion in the Streets. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 1992. 7-10.

Koolhaas, Rem and Bruce Mau. S,M,L,XL. OMA. New York: The Monacelli Press, 1998.

Krauss, Rosalind. “Cindy Sherman: Untitled.” Cindy Sherman: 1975-1993. New York: Rizzoli International, 1993. 101-159.

–––. “Corpus Delicti.” L’Amour fou: Photography and Surrealism. Eds. Rosalind Krauss and Jane Livingston. New York: Abbeville Press, 1985. 55-112.

–––. The Optical Unconscious. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1998.

Nunn, Robert. “Spatial Metaphor in the Plays of Judith Thompson.” Theatre History in Canada 10. 1 (Spring 1989): 3-29.

Posner, Helaine. “The Self and the Word: Negotiating Boundaries in the Art of Yayoi Kusama, Ana Mendieta, and Francesca Woodman.” Mirror Images: Women, Surrealism, and Self-Representation. Ed. Whitney Chadwick.Cambridge,MASS and London: The MIT Press, 1998. 157-171.

Schor, Naomi. Reading in Detail: Aesthetics and the Feminine. New York and London:Methuen, 1987.

Thompson, Judith. Habitat. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2001.

–––. “I Am Yours.” The Other Side of the Dark: Four Plays By Judith Thompson. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 1989. 115-176.

–––. Sled. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 1997.

–––. “The Crackwalker.” The Other Side of the Dark: Four Plays By Judith Thompson. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 1989. 15-72.

Williams, Raymond. “Social Environment and Theatrical Environment: The Case of English Naturalism.” English Drama: Forms and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977. 203- 223.