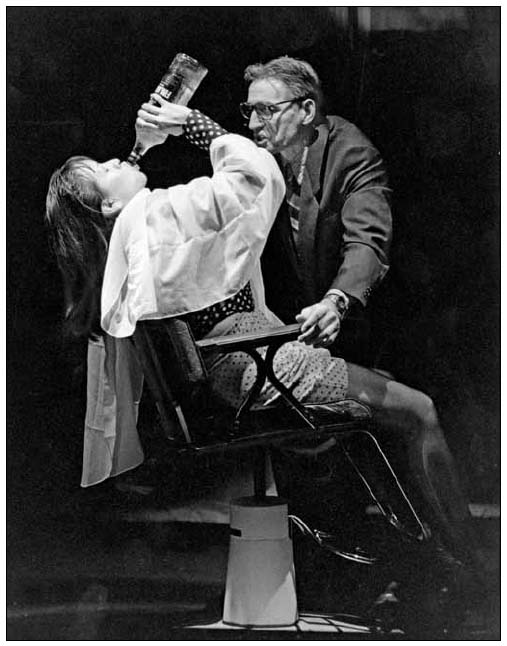

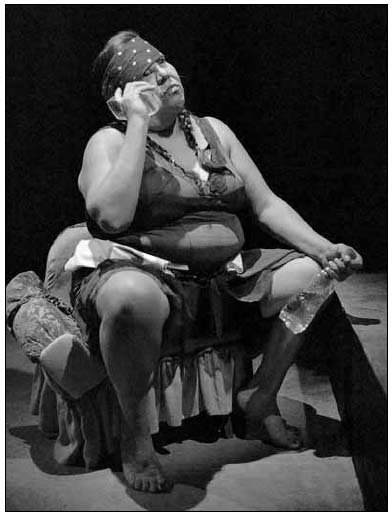

“...no evidence of violence or suspicion of foul play....”

(Performers: Adele Kruger and Peter Hall; Firehall Arts Centre

Production,Vancouver, 2000) Photo by Andrée Lanthier, courtesy of the

Firehall Arts Centre.

REID GILBERT

Cet article décrit brièvement la notion provisoire de l’auteur sur la «sheer theatre» et l’applique à une pièce de Marie Clements sur le meurtre en série de femmes autochtones, intitulée The Unnatural and Accidental Women. En montrant comment la pièce se sert d’éléments textuels non verbaux (mouvement, effets sonores, éclairages et projection d’images), Gilbert propose une série de graphèmes physiques et examine comment l’«écriture» «immatérielle» peut servir à dénaturaliser la reception. Un tel déraillement de la réaction prévue au genre conventionnel sert à traumatiser la réception, à établir des liens entre les déchirures opérées au tissu de la représentation et les vies brisées des personnages désenchantés de la pièce. Il incite également les spectateurs à «lire» le récit des personnages à travers le filtre de leur propre expérience, de sorte à produire une réponse essentiellement théâtrale pouvant mener à une évolution sur le plan social.

What are the stabilizing [. . .] features that characterize these texts? What are the destabilizing features? What are the values and beliefs instantiated within a set of practices? Who can or cannot use this genre? How does this genre affect its users? (Catherine F. Schryer 108)

A foundational characteristic of theatre, noted by Derrida and (re)marked by Peggy Phelan, is that “Theatre continually marks the perpetual disappearance of its own enactment” (Unmarked 115). I have elsewhere attempted to discuss the incision point of this disappearance, the infinitely thin blade of representation that carves a liminal edge between theatrical performance and its residue in the cognition of spectators.1

Any such consideration of audience reception also requests consideration of the role of genre in the institutionalization of power and the place of theatre (in all its forms) in such regimes. Working from earlier theories of Kenneth Burke and others, and focusing “not [only] on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish”(Miller 24), North American scholars engaged in what they term The New Rhetoric and Australian scholars of the “Genre Pedagogy” School consider genres to be “‘functional’ social processes,” which – while they admit “heteroglossia and play in local, contested ways” (Luke viiiix) – nonetheless halt such play, fixing signification by repetition within a broad scheme of social performativity. Allan Luke is concerned that these rhetorical projects run the risk of

‘writ[ing] over’ culture as given [. . .] to assume that [. . .] particular [. . .] sites are benign, consensual social bodies where (mostly monocultural and patriarchal) discourse norms, ‘common goals’, ‘motive strategies’ and ‘private intentions’ occur naturally and unproblematically. The danger here is that failure to acknowledge the material sources of ‘difference’ and power, marginality and exclusion naturalizes these as [merely] ‘context’ variables. (ix)

Luke warns that such analysis “risks the same old psychological romanticism,” risks cutting off “questions of discourse and power”(ix).

Such regulating and containing strategies are particularly dangerous in any analysis of plays such as Marie Clements’s The Unnatural and Accidental Women.2 To approach such a “site for struggle” (Schryer 1083) with theories that arise within the very colonizing cultures against which a First Nations playwright may react threatens to perpetuate the hegemony or to assume a monolithic spectatorship. I register as problematic the fact that, throughout this paper, I mainly employ theorists who discuss issues such as memory, language, and theatricality from non-Aboriginal perspectives. 4 Interestingly, however, the use of Aboriginal performance criteria such as Ric Knowles employs in his analyses of the “new historical and artistic forms emerging from historical and contemporary Native life, culture and experience” (Theatre 145) flag efforts very similar to those I observe in Clements’s aim to destabilize genre (as in Knowles’example of Daniel David Moses’s Almighty Voice and His Wife [146]), and to employ a “Carnivalesque cacophony of stylistic and generic materials first to foreground metatheatrically [.. . any] stabilizing inscription,” as in Knowles’ example of Monique Mojica’s Princess Pocahontas and the Blue Spots (147).

As well, in using the term “genre” broadly I do not mean to overlook the internal conflicts within any genre. If utterance spins with both centripetal and centrifugal force, so does genre. While, for example, the categories “feminist writing” and “Métis story-telling,” may be present in Clements’s work, these separate “genres” are not linked, nor are they necessarily mutually supportive. Indeed, where they collide would be a powerful point of intersection to analyze and a laboratory site of identity politics. Such is not, however, the purpose of this paper, which aims to explore the process of rupture – the mechanics of trauma – rather than to define the complex categories I take as given regulators of identity and expression. I will later suggest that a spectator (or, more exactly, a spectator trained in European reception) will attempt to suture any rupture and this includes the tears caused by conflict within and between genres as much as by the panic of unfamiliar genre. This is the hypothesis, I think, of Marie Clements’s earlier revision of Greek myth in The Age of Iron.5 While the coding of this play calls upon knowledge of native iconography and the play fits in a genre of “native tragedy” (like The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, for example, by George Ryga), it also assumes audience familiarity with the founding Greek myths. What the play demonstrates is that the genre of the mythic story of male dominance seeks still to contain First Nations women even as it sought to contain Cassandra and Hecuba. The Unnatural and Accidental Women, on the other hand, aims to disrupt perception and to refuse a bringing-forward of the traditional narrative boundaries of control.

As always, any discussion of audience reception is fraught. Every audience differs and it is easy to suggest coterie audiences who might receive this play quite differently from others, including the two identity-categories just mentioned as examples. The play’s first production was at a commercial theatre with no especial invitation for viewers. However, the Firehall Arts Centre Theatre in Vancouver does have a mandate to produce plays from non-mainstream voices, so its audience could be assumed to be different from those of a large subscription house. Although Firehall spectators may have more interest in issues of alterity and social action than those at larger, uptown theatres, there is no reason to assume that their literary and theatrical training is substantially different or their familiarity with commonplace fiction any less. Certainly Clements appears to assume a set of responses since she works specifically to upset them. Hers is not a play which employs non-standard acting styles in an unusual story, but one which strives to complicate and rupture the expected, to tweak audience perception by overlapping and complicating what is, at base, a standard plot-based, western detective and revenge fiction (albeit with a First Nations intertext of the wilderness and its link to spirituality). Indeed, her somewhat prosaic plot should be familiar to a wide range of spectators, so recognizable is it from popular fiction, theatre, film, and television.The play, however, works against the “discourse norms” which a majority of the audience, especially in a commercial house, may assume “occur naturally”(to repeat Luke’s warning [ix]). These “goals”exercise imperial control over those very cognitive powers upon which the disappearing moment of theatre flickers.

But that moment does, nonetheless, flicker; the theatrical still urges response under and beyond the plot that seeks to domesticate it to the conventions of genre. It is for this reason that I wish to move behind genre (either broadly or specifically defined). If the goal of a playwright is actually to effect change, it is necessary that the writer derail reception – at the site of primary perception – at least enough to “denaturalize” its hidden assumptions and reveal the “differences” which call for action. If assumptions lurk within all genres of written and oral communication, it is necessary to appeal to a more ancient communication between rhetor and auditor.

I have elsewhere explored at length the notion of what I tentatively call “sheer theatricality,” an admittedly romantic and dangerous term that I have applied to the non-verbal theatre pieces of Morris Panych and Wending Gorling.6 To repeat myself in a brief definitional note: in coining the term, I want to avoid the moral implications of the adjective pure (though its second OED definition does make it synonymous with sheer). Instead, I am attempting to apply the OED definitions, “of light: clear or pure” (OED 3A.4; 4.2), and, “Of an immaterial thing: Taken or existing by itself [. . .] alone” (3A.7b), and, again, “Completely, absolutely, altogether, quite” (3B.1). By interrogating the effect of the “absolutely; quite” theatrical, I am suggesting a kind of “writing” whose text is constructed through a coining of physical and sensory “graphemes,”7 which arises in a mise-en-abyme, and which exists outside, but lends itself to, the spectator’s desire for presence – including her psychological need to locate her own presence in space-time. In interrogating the effect of the “absolutely [. . .] quite” theatrical, I attempt to describe a special kind of “writing.” What interests me here is not the actual theory of the “sheer,” but the power of such “immaterial” “writing” to denaturalize reception.

To use the term “writing” in this manner – to apply it to a physical and sensory language carried in bodies, sound and apparatus – is to allow the entire semiotic field to register meaning as a complex of “graphemes,” foregrounding “writing” over speech, and enacting a Derridian différance. Such “writing” remains dynamic, resisting unitary meaning: as it undulates in and out of various genres and in and out of the various responses of spectators, it exposes its own hybridity, its dialogism. More important, it also harkens far back for citation. By moving to a place before calligraphy and even before orality, it moves to a space without imperial signification.8

To move to a pre-linguistic “writing” is to move from conscious notation as the servant of metaphysical presence toward the unconscious, toward the beforehand as suggested by the Lacanian concept of the Imaginary.9 Derrida “admit[s] the necessity of going through the concept of the arche-trace” (Of Grammatology 62), but points out that it was “never constituted except reciprocally by a nonorigin” (Of Grammatology 61). Similarly, the Lacanian Imaginary does not exist outside the spectator or the drama (in some fixed “arche” or “telos” or “transcendentality,” to use Derrida’s terms [Of Grammatology 61]), or outside presence in a negative theology, but already within the psyche of the spectator. A spectator who has moved through Lacan’s mirror stage (which is to say all adult viewers) desires to translate these arcane and voiceless arche-traces into the signifiers of the Symbolic Diaspora of language (Lacan, Seminar 79),10 to assign one of the “psychophysical and linear conceptions of character, motivation, and action which are already culturally privileged and deeply inscribed in theatrical discourse” (Knowles, “Shakespeare” 21511) in order not only to “understand” the play, but to discipline it, to affix genre or style and – most important – to locate herself in space-time. The “sheer” must necessarily work with this impulse, but also works against it, offering a different mechanism of “reading,” and, therefore, a different set of understandings.

To some extent, of course, any audience member at any play undergoes something like this process of recognition. As Harry Elam reminds us, the performative aspect of theatre is always “something that is beyond writing.” What I am proposing, however, is not only “beyond writing,” but somehow before it. It is a different brand of “writing.” The “sheer” does not circumvent writing: it assigns different meaning to graphemes which, incidentally,may simultaneously be read within any number of standard writing schemes – and therefore within the regulatory practise of any number of genres – or be seen to perform into being any one of a number of available hailings. It writes onto the physical and sensory and onto bodies. The “sheer” does not rely upon the spectator’s “thinking out loud” silently – a metaphor of speech. That would be a performative “speaking into being” related to Austin’s speech acts. The “sheer” calls upon the spectator to “read” what is always anyway written within a complex theatrical field – to “read” chthonic postural, auditory, and visual signs from a pre-intellectual place within the Imaginary. I wish to employ my provisional notion of “sheer theatricality,” as I consider how elements of the theatrical operate to open out perception in The Unnatural and Accidental Women and to reveal Luke’s markers of “difference” and “power, marginality and exclusion”(ix).

Writings from political subject-positions – as Susan Bennett has reminded us in reference to the re-inscription of female bodies – often “endeavour to destabilize the complacency of spectators” (39). They also open out spectatorship at the point of reiteration where genre seeks to assign meaning by containing the Imaginary in the Symbolic (to use Lacan’s terms), by diverting attention to the performance text and, as a result, exposing the theatrical at a “sheer” moment. Any manoeuvre that unbalances or deflects reception may tear a hole in the familiarity of genre and, hence, in the fabric of representation.

As Lacan alerts us, and I earlier mentioned, western spectators will generally attempt to suture over any such rippage by locating what Laclau and Mouffe have called a “‘nodal point,’ (the Lacanian point de capiton) which ‘quilts’ [floating or broken signifiers], stops their sliding and fixes their meaning” (Žižek 87). Genre plays a particular role in such repair since it is within known genres that spectators can find the models already located in the Lacanian Big Other (A)12 which they need to apply Lacan’s “effect of retroversion” (Žižek 87) in order to read back meaning onto signs they wish to inscribe and contain – or worse, to abject. Derrida has observed that the Western spectator is trained “to deplore a metaphysical vacuum” (Writing 289) and Žižek warns that “capitonnage is successful only in so far as it effaces its own traces” (102), so a playwright wishing to offer radical inscription must work against these regulatory impulses, somehow preventing spectators from applying the easy solution of the familiar that offers a ready means to fill any empty space in perception and a means to forget that one has done so. Catherine F. Schryer notes that an audience has “a rich repertoire of [such genre-based] utterances at its disposal” (108); it is for this reason that “spectators [. . . have been] terrifyingly well trained to conduct their own silent surveillance” (Bennett 39) and to enforce accepted hailings and interpretations. Genre is deeply ingrained, devious, and insistent: it will resist slippage even when theme and characterization propose new readings.

The Unnatural and Accidental Women concerns the murders of many women (most of whom were middle-aged Native women) by a serial killer in Vancouver during the 1980s. Gilbert Paul Jordan, a barber, killed his victims by forcing them to drink alcohol to the point of toxicity. The coroner’s reports found the deaths “unnatural and accidental,” but found “no evidence of violence or suspicion of foul play” (Rose and Sarti). Many critics of these judicial findings argue that investigation was hampered by attitudes to the victims – Native and non-white women, prostitutes and alcoholics living in the poorest region of the city. (In light of the ongoing investigation of an even more gruesome set of murders and the disappearance of more than sixty women from this borough, the play becomes an important call for social action.)

“...no evidence of violence or suspicion of foul play....”

(Performers: Adele Kruger and Peter Hall; Firehall Arts Centre

Production,Vancouver, 2000) Photo by Andrée Lanthier, courtesy of the

Firehall Arts Centre.

Against this backdrop, Clements proposes new readings of binaries that control much in Canadian society: male/female, Native/Non-native, rich/poor, powerful/abjected, lonely/embraced, police/citizenry, technologically connected/disenfranchised by technology, urban/northern, victim/victimizer, material in a Marxist sense/material in a spiritual sense, agent of cathartic revenge/agent of feminist transformation.

Notwithstanding her revisionary politic, however, such binaries are easily subsumed under conventional genres and this play – on the surface – works within such forms. At the same time, however, The Unnatural and Accidental Women vivifies the kind of Derridian “free play of signification” I have been discussing; it is an example of the derailing of the anticipated and familiar and the intrusion of the unfamiliar – that which is always barred from, but always implicit within genre. The play urges spectators to admit multiple and altered inscriptions. The non-verbal action, set design, lighting, visuals and soundscape – elements of the “theatrically sheer” – work in support of, and in opposition to, the straightforward plot, complicating any easy interpellation of the characters by overlaying a second, more complex performativity, by enriching the semiosis, and by marking tensions in and between genre. The play’s design works against expectation even when the dramatic genre cunningly halts itself in what Catherine F. Schryer has called a “stabilized-for-now or stabilized-enough site [. . .] of social and ideological action” (108), a space that permits spectators to understand the political message while deferring it. Schryer points out “genres come from somewhere and are transforming into something else. Because they exist before their users, genres shape their users, yet users and their discourse communities constantly remake and reshape them” (108). In The Unnatural and Accidental Women, spectators are encouraged to “remake and reshape” because Clements crafts a “discourse community” that participates imaginatively in the making. The audience does not simply receive fictional or thematic information, but works with the theatrical to build an aesthetic experience that exists outside the conventions of the “well-made” play or, perhaps, in “perverse” variation of known dramatic forms (borrowing Ric Knowles’ use of the adjective [Theatre 32; 69]), or at least at the contemporary edges of form. In this way, the play itself becomes metonymic of the process of theatrical myth-making and the potential of the theatre to disrupt and remake at the moment of its disappearance, at the moment it slices into the psyches of its spectators.

The Unnatural and Accidental Women takes place in many short scenes on a complicated set. Clements calls for a number of recurring theatrical elements: acting areas, slide projections, sound effects, lighting effects, rhythms.

In the Firehall Theatre production in Vancouver, the skid-row Beacon Hotel was suggested in a box-like vertical construction in which the characters Aunt Shadie (a Native mother figure) and Rose, the “English immigrant [. . .] switchboard operator” (60) occupy their “own spaces and places. They are in their own world. Happy hunting ground and/or heaven” (60). Other acting spaces included the bar where the predator, Jordon, picked up his victims; Jordon’s barber shop; various cheap hotel rooms where the women lived before their deaths; and the apartment of Rebecca, a woman of mixed blood, “a writer searching for the end of a story,” the daughter of one of the victims and the revenge heroine (60). Slide projections added space behind and above the human action, and a sound effect score added voices and sounds that both accompanied the action and worked in counterpoint to it.

Clements’s stage directions and secondary scores are highly poetic and announce the theatrical layers that operate with and against the police story and revenge plot, opening up these standard fictional genres. Some examples may help to illustrate her methodology, though the play is hard to capture in summary. The initial setting note provides the following description:

Scenes involving the women should have the feel of a black and white picture that is animated by the bleeding in of colour as the scene and their imaginations enfold. Colours of personality and spirit, life and isolation paint their reality and activate the particular landscape within each woman’s own particular hotel room and world. [. . .] Levels, rooms, views, perspective, shadow, light, voices, memories, desires. (60)

Such directions are difficult to stage within any performance style.13 Nonetheless, the aim of the play is to intermingle short biographies of the women with their individual death scenes, with family memories and dreams, with social comment, with political and economic history, with a contemporary love story, with a fictional and utopian revenge, and with native dreams of a redemptive North. The play is extremely complex. Its complexity, however, is exactly my point. By mixing elements and overwhelming the audience by their variety, the play requests its spectators to “see” the theatrical apparatus at work, to allow the “sheer” to write itself into cognition.

In the opening scene, for example, Clements calls for “Elements: Trees falling, falling of women, earth, water flowing, transforming” (60). These notes are acting and design prompts, but they are also meant somehow to be “read” by the scriptless audience who must discern them in the layered semiosis of theatrical signs. A slide reads “Timber” (60), but the “lights fade up on Rebecca” at a bar table. “Behind her, a forest of West Coast trees grows in lushness on a backdrop,” accompanied by a sound effect of “trees moving in the wind”(60). A logger enters – a male character who reappears in various forms – and fells trees to another sound effect over Rebecca’s historical account of the rape of the first-growth forest which turns into Skid Row in Vancouver. The trees themselves turn into “a blizzard of sawdust chips” which “swarms the backdrop until one by one the trees have been carved into a row of hotels” (61). Rebecca mouths “Honey, I love you” to the man as she speaks of the loggers and their lovers,“the trees,”the men now reduced to remembering a time “when cutting down a tree was an honest job”and “the women, oh the women, strolled by and took in their young sun-baked muscles” (61). The material world of trees and labour contrasts an immaterial world of memory, desire, and a landscape “beyond precise articulation or realist representation,” to apply Sherrill Grace’s description of a Southern reading of “North as the Other” (150). The material world of Skid Row is built in the imagination from its binary opposite, the immaterial world of female desire and Native spirituality to which the final scene will return, though now within a revenge motif. (There are, in fact, at least four genres at play here, each with links into the others and each resistant to the others: audience reception is entangled within these representations that, as I earlier noted,“undulate”between registers and “rewrite” themselves.)

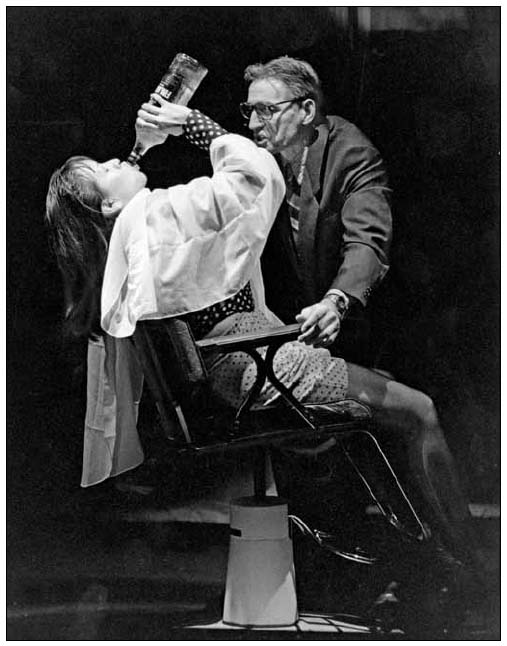

In the penultimate scene, Rebecca seduces the barber into his own chair and “braces” herself to “cut his throat” (88). The act of vengeance, however, is performed not by the “real”Rebecca (or, at least, not by her alone), but by Aunt Shadie and a chorus of the dead women now revealed as trappers.

AUNT SHADIE. I used to be a real good trapper when I was young. You wouldn’t believe it now that I’m such a city girl, but before when my legs and body were young and muscular I could go forever. Walking those trap lines with snow shoes. The sun coming down, sprinkling everything with crystals some floating down and dusting that white comforter with magic […]. (88)

Rebecca repeats key lines of Aunt Shadie’s memory speech, transforming herself also into a trapper, taking the image of the northern Native woman into herself even as the audience is invited to meld the binary images of young woman and old, city woman and Northern native, predator and victim, which render Jordon “an animal caught” (88). While any play can suggest that a character has changed, the “sheer” here allows Rebecca literally to transform, to “write” herself into the semiosis as (what I will term) a “bio-grapheme,” to “write” the set of binaries and “rewrite” them on her body and the collective body of the dead women. After the collective “woman” kills the murdering barber, Aunt Shadie simply states, “Red,” a single word of dialogue that has no fictive purpose, one that Rebecca repeats – and to which I will return.

Trapper Women (Performers: Muriel Miguel and Ensemble, Native Earth Production,Toronto, 2004) Photo by Nir Bareket, courtesy of Native Earth Performing Arts.

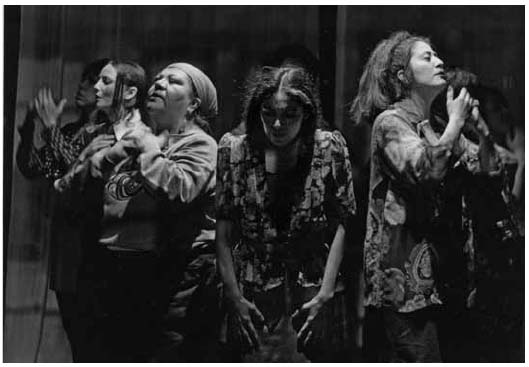

As the lights come up again on the closing scene, the dead women, transformed into trappers, sit at a long table under a slide that announces “The First Supper. Not to be confused with The Last Supper.” The Sound Effect of “trees moving in the wind” returns and progresses to the sound of “a tree, falling” (88). The slide changes to “Timber”once again as the “Barbershop area” is lit, revealing the murderer now murdered while, in the “Apartment area,” Rebecca and her policeman boyfriend are seen having a “somewhat romantic dinner.” The sound effect is of a “tree, falling”; “Barber lights swirl red and white throughout the barbershop. The red light intensifies and takes over the room.” The final sound effect is that of “a tree hitting the ground with a loud thud.” The thematic conclusion within the revenge genre is clear: the murdering man is dead – “thud.” The women have found resolution in the “happy hunting ground and/or heaven” promised in the opening. Rebecca has freed herself from mourning and found a possible future with Ron. The fictional world fades; the theatrical moment seems to disappear, the revenge genre closes, the feminist and Native stories end in transformation, the urban love story hints at a happy ending. The various strands carried in the theatrical text, however, are much less clearly concluded and the affect on the spectator is not yet finished; the simple themes become more complex as the “sheer” “occults”14 itself at the edge of perception.

The final image of Rebecca and Ron seems to suggest that a loving relationship between men and women is possible if male violence can be overcome, but the theatrical text is less tidy. The play ends in red light which, moments earlier, Aunt Shadie has linked to male blood and death. Aunt Shadie has both simply described the blood seeping out of Jordon’s corpse in a literary synecdoche and – from within the theatrical – spoken a sensory “grapheme” into being, ordering the set to redden itself and the spectators to admit the new light waves into their eyes. Red overwhelms white; the male pattern of a barbershop pole bleeds its violence onto the romantic tableau; a last tree falls victim, hitting the ground with an audible thud.

These purely sensory stimuli question the political thematics: can women gain power without perpetuating the violence of power itself? Can an urban landscape be returned to a spiritual landscape once the urban is built from the destruction of the natural? Indeed, is such a landscape anyway only what Grace calls a North turned into an “aesthetic object removed from the welter of social realities and problems” (150)? Surely, here, the landscape reveals itself as aesthetic object projected and lit expressionistically. The chorus of dead women, like women in the plays Grace analyses, “go North to find themselves – in death and in a promise of rebirth that lies beyond the end of the play, in symbol and myth” (150), but the red light bathes the remaining living woman and her audience, and the tree falls into the “social realities” of the South, of the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. Two registers collide: a mystified North embodied in spiritualized women and a realistic world which, in the Vancouver production, was just outside the door of the theatre, part of a larger performativity the spectator will continue to “write” as he searches for his car after the performance, hoping there has been no damage done to it in this very rough part of town.

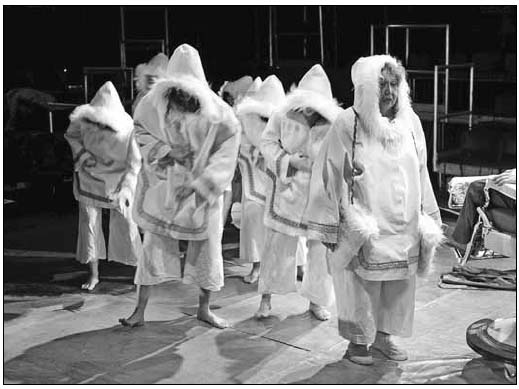

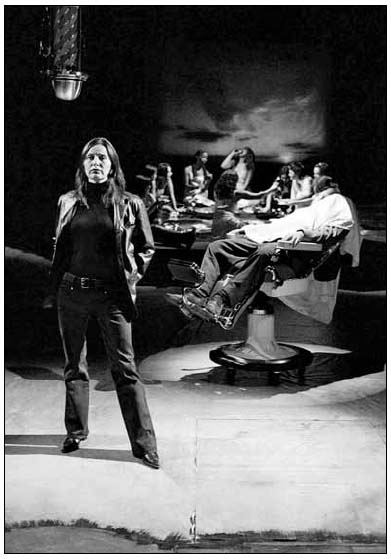

“Exploring ‘the potential of the theatre to disrupt and remake

at the moment of its disappearance [...]’.”

(Performers: Adele Kruger, Odessa Shuquaya, Gloria May

Eshkibok, Sophie Merasty, and Columpa Bobb; Firehall Arts

Centre Production, Vancouver, 2000) Photo by Andrée Lanthier, courtesy

of the Firehall Arts Centre.

Does the fictional ending “naturalize” (Luke ix) the material condition of these women and similar women in the Vancouver Downtown East Side yet to come? If so, the theatrical ending refuses any such expectation of catharsis and closure. The repeated slide, the red glow, the “thud” each raise important ongoing questions: need this cycle of violence against women repeat itself; must the action come round again to the opening scene? Is the hope that the poor, the homeless, and the lonely can be reclaimed from alterity only a reassuring trope, another imperial manoeuvre of genre to forestall political action? (Why did these murders still occur after the staging of The Ecstasy of Rita Joe to a mainstream audience at the Vancouver Playhouse in 1967-68 and at the National Arts Centre in 1969?15) Is the ending merely another example of Schryer’s observation that genres “embody the unexamined or tacit way of performing some social action. [. . .] the ways that a dominant élite does things” (108)? If so, does the cruel glare of red light discomfort the spectator enough to problematize this sinister tactic? These are the sorts of questions that the theatrical elements whisper to the spectator at the moment of reception – or, more accurately “write forth” to her in pre-linguistic markings. The spectator may register them and, if she does, the naturalizing regime falters, at least for an instant.

Another set of examples: in nuanced characterizations, Clements has shown that these women love and desire (gentle)men, even as they live in a world of loneliness, exploitation, prostitution, and murder. Again, the set and props carry these characterizations far beyond what is spoken in the text.

In the scene called “Room 23, When You’re 33 – Clifton Hotel,” Valerie first has a conversation with a “small and battered” three drawer dresser. This scene is full of puns and sexual innuendo on the literary level (much joking about “drawers” and “knobs”); it is also essentially theatrical since it involves choreography between a human being and a piece of furniture. Such personification recurs throughout the play. It will be useful to note two other examples that compliment this central example of Valerie and the Dresser (to which I will return) – examples that underline the conscious use of this technique by Clements.

The agoraphobic Mavis repeatedly tries to speak to her sister on the telephone, but her drunken and technically inept attempts are always intercepted by the British-born telephone operator or the North American mechanization of answering machines (technologically connected/disenfranchised by technology). She sinks into alcohol, into depression, and into a chair she fantasizes as “Johnny,” a gentle man who enfolds her in his upholstered arms. Finally, however, Chair/Johnny transforms into a real Man who is, of course, the horrific foreshadowing of Jordon:

MAN. Can I get you a drink?

MAVIS. Where is John?

MAN. John who? (74)

For the audience, this moment is carried not only in the prosopopoeia, in which they hear a chair speak as human, but in a metonymic experience in which the themes of man-as-lover and man-as-killer coalesce. So, too, do motifs of chair-as-domestic and chair-as-broken-down-refuge-of-the-drunk. So, too, do inscriptions of old furniture as accoutrements of cozy homes and detritus of cheap hotel rooms (as Freud might suggest, and I earlier observed, it is a coming together of the heimlich and the unheimlich in the barred other. As Freud points out, the heimlich “becomes increasingly ambivalent, until it finally merges with its antonym [. . .]. The uncanny [. . .] is in some way a species of the familiar [. . .]” [134].) As the sound effect of another disembodied electronic voice comes up – “If you need assistance, just hang up and dial your operator [. . .]” (74) – a slide announces Mavis’s death.

Mavis (Performer: Gloria May Eshkibok; Native Earth Production,Toronto, 2004) Photo by Nir Bareket, courtesy of Native Earth Performing Arts.

In “Four Days: Day 3 – Glenaird Hotel,” the actor portraying Marilyn stumbles around her “drinking room”without speaking. A male Voice Over seduces a female Voice Over, as Marilyn’s fantasy actualizes itself on stage. As the mute actor “loses her balance,” and looks down to regain her footing, the audience sees “The silhouette of a deer’s legs and hooves” projected on the floor beneath her. [. . .] The pillow becomes a man dressed like a pillow. [. . .] Lights Out” (68).

That another woman is about to fall victim to the murdering barber is announced in the plot line, but, more powerfully, this amalgam of auditory and visual images creates an entirely theatrical “acting forth.” The motifs of trapper/Native/Northerner and animal/Native/Southerner come together with the themes of manas- lover and man-as-murderer, but come together collectively in theatrical images and movement, not serially in dramatic dialogue. And, again, the stage goes dark at the moment the audience “sees” the group of graphemes; the play “disappears”; the meaning is assembled in the mind of the spectator and read back into the semiosis.

Such “acting forth” is pivotal in the two scenes with Valerie to which I now return.

As the dresser makes lewd suggestions in the first scene, Valerie is attracted to it while attempting to maintain control. Because, in fact, she does want “to see what’s in [its] drawers,” she risks proximity and is assaulted – a hand comes out of the drawer and squeezes her breast. Despite the insult, she wants the dresser, whose mirror has begun to show a man’s face, to desire her, and she needs to affirm that despite the fact that “I had two sons you know” she still has “great tits” (65). At the end of the scene, she “kicks him in the drawers”and they “fall on the floor wrestling” (65).

On the political level the scene is clear: this woman desires male company but will not allow herself to be called a “whore”(65) or to be violated. On a social level, the scene, and others like it, reproduce the hallucinations these women experience while suffering the DTs. Yet, on the theatrical level, more is happening.

Valerie’s sexual frustration is apparent in the flirtatious dance with the dresser, but her loneliness and self-loathing and the link between these psychological conditions and her abjection by men are more poignant in a later scene when the dresser broadcasts the voices of her children trapped in its drawers. While the boys are invisible on stage, the fear of the abandoned child and the anger of the world-weary older son are revealed as products of Valerie’s own longing and fear, and are the more powerful for being conjured only in the spectator’s imagination:

TOMMY. When are you coming home?

EVEN. Probably never.

[…]

VALERIE. It’s hard to come right now, but soon . . . I’m gonna get this job and soon ...

TOMMY. How soon?

EVEN. Soon. Liar. (72)

Valerie tells her sons she can “picture [them] in [her] head,” and so can the spectator, who cannot, however, assign this cartoon action a suitable genre label. This is not the playful, personified furniture of Mary Poppins, and it doesn’t offer the humorous escape possibly offered to some viewers by the sexual badinage of the earlier dresser scene. This is a theatrical amalgam of drunken hallucination, self-repudiation, desperate loneliness, and sadism. The viewer links these male children, described by their sad mother as “my two little men,”with the male-as-aggressor symbolized by the dresser. Just as the adult male furniture assaults Valerie, her older son is learning already to despise her, or she has learned to assume he does. The dresser attacks her with its drawers, knocking her in head, stomach, and legs; “it buckles her” (73). As she falls, semi-conscious, the “Tommy drawer” opens and a voice calls, “Mommy?” (73). As she tries to answer her younger son’s call, the dresser “slams her in the head. She slumps down, her head on the Tommy drawer. The dresser’s hand comes out of the top drawer and reaches down across her chest, fondling her breasts. Lights out”(73).

Valerie and the Dresser (Performer:Michaela Washburn; Native Earth Production,Toronto, 2004) Photo by Nir Baraket, courtesy of Native Earth Performing Arts.

The image disappears in darkness; the theatrical moment slides away, but the spectator makes connections, perhaps judging the mother who has abandoned her children for a life of drink, but more likely suffering with the woman who has been taken from her children and the hope of a loving partner by economic and social subjugation. Moreover, the spectator remembers the previous fleeting images of the dresser scene and other related theatrical semes in similar personifications throughout the play, sorting and linking them, picking up their “rhythms,” textures, and wave lengths: those invisible – those “sheer” – nuances which Clements stipulates and which, it appears, the scriptless audience can, in fact, “read.”

Consider, in a final example, how the spectators “read” even in a language most do not speak since all, in fact, are reading in the mute language of the “sheer.” In the swirling red and white light of Jordon’s barbershop, the character Penny sees the faces of her children in the mirror and Chinese lettering emerging “from the swirls” (68). Chinese music comes up and Penny sings, accompanied by the voice of Marilyn, killed in the previous scene. Some lines are sung in Chinese; some in English. The audience, then, sees and hears a theatrical mélange which makes no realist sense, but again connects the women, their love of children, their nonwhite status, their drinking addiction, and their inevitable deaths. Again, the comment is made in both dramatic and theatrical terms, but the nuanced characterization is made only on the theatrical level.

These few examples begin to illustrate a methodology throughout the play. By employing rather simple and well-known western literary genres, Marie Clements lulls an audience into observing a number of social evils and celebrating their overturn – that in itself is a laudable achievement. But, at the same time, she has designed a complex theatrical web of representation which tears at received Western, non-Native, and phallologocentric dramatic conventions: “[S]uch intersemiotic ‘translation’ will inevitably [. . .] dis/place [. . .] and hybridize [. . .] conventions, [. . . posing] a challenge [. . .by positing] the word as a process of knowing, provisional and partial, rather than as revealed knowledge itself, and aim[ing] to produce texts in performance that would create truth as interpretation” (Godard 184). The trauma of such rupture will remain in the psyche of the viewers, precisely because it is, in fact, a tear in their own cognitive screens. Peggy Phelan notes in Mourning Sex: Performing Public Memories that “Trauma [. . .] cannot be represented. The symbolic cannot carry it; trauma makes a tear in the symbolic network itself” (5) – and so this play demonstrates. In another context, Phelan hopes “a performative psychoanalysis of [. . .] trauma might begin to inscribe a different political history, a history written with and through the bodies of women as they appear and disappear in the discursive narratives of both law and psychoanalysis” (Mourning 105). It is not on the surface of the symbolic network of genre that The Unnatural and Accidental Women incises its complex, original message, but into the perception of its spectators. Momentary and ever-disappearing, the theatrically “sheer” has once again written itself into being,“denaturalizing” any colonial attempt to draw boundaries in genre, and calling for change.

Death of the Barber (Performers: Lisa C.Ravensbergen, Ensemble, Gene Pyrz; Native Earth Production, Toronto, 2004) Photo by Nir Bareket, courtesy of Native Earth Performing Arts.

NOTES

1 See my “‘Sheer’ Texts ‘Written’ in(to) Perception.”

Return to Aritcle

2 I quote the play’s first publication in Canadian Theatre Review (2000)

because it is the text with which I am most familiar. The play is

included in Staging the Pacific Province: An Anthology of British

Columbia Plays, 1967-2000. Ed. Ginny Ratsoy and James Hoffman.

Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 2001, and, most recently in Staging

Coyote’s Dream: An Anthology of First Nations Drama in English. Ed.

Monique Mojica and Ric Knowles. Toronto: Playwrights Canada,

2003.

Return to Aritcle

3 Here, Schryer is employing Bakhtin’s notion of the centripetal and

centrifugal within utterance; see Bakhtin 60-102.

Return to Aritcle

4 In editing the script for its publication in Canadian Theatre Review,

for example, I discussed with Marie Clements the long opening to the

second act in which the women-in-memory discuss Ron’s male body.

For reasons of length, we together cut much of this business, but

Clements reintroduced it in the production I discuss and in the later

published version. Clements is working in an Aboriginal genre that

differs from western notions of narrative and memory and differs

from Eurocentric performance regimes. Cf. Monique Mojica’s radio

play, Birdwoman and the Suffragettes; see Knowles, 147.

Return to Aritcle

5 For a fuller discussion of this play, see my “‘Shine on us, Grandmother

Moon’: Coding in Canadian First Nations Drama.”

Return to Aritcle

6 See my “Panych and Gorling’s The Overcoat: Silent remnants; new

genres.”

Return to Aritcle

7 In Glas, Derrida meditates: “I do not say either the signifier GL or the

phoneme GL, or the grapheme GL. Mark would be better, if the word

were well understood, or one’s ears were open to it; not even mark

then” (119).

Return to Aritcle

8 In the context of a native play, the proposal of a stage of “pre-writing”

may appear to suggest implicitly that the pre-contact native oral tradition

was uninflected or did not contain its own boundaries of genre

and social power; such was surely not the case. My notion of the

“sheer” requires a theoretical acceptance of a pre-lapsarian moment

though held only as a barred marker of the Effect of Retroversion, as

the next paragraph attempts to suggest.

Return to Aritcle

9 Toward the place of the “je” before it deflects identity to the “moi” of

the mirror stage. See Lacan,“The Mirror Stage.” Écrits. 1-7.

Return to Aritcle

10 As Kaja Silverman sums up the concept: “it is only in the guise of the

ego that the subject can lay claim to a ‘presence’ [. . .]; the mise-en-scène

of desire can only be staged [. . .] by drawing upon the images through

which the self is constituted” (5).

Return to Aritcle

11 Interestingly, Knowles’ comments are in relation to the Stratford

Festival. He suggests such conceptions are “reinforced” by the

Stratford Festival’s corpus of eight voice-and-movement coaches, so

standard productions, it seems,work to contain even the physical and

audible, placing them into known registers of Symbolic discourse.

Return to Aritcle

12 See “Graph II” in Lacan’s Écrits. 306.

Return to Aritcle

13 A judgement of the success of this first production is, however,

fraught. To say whether the play was successful in production is to

apply particular performance criteria and to evaluate performance in

particular ways. Since the play aims to present reality from within

both Native and female perspectives, it would be incorrect to apply

traditional Western and patriarchal performance measures to it. I am

indebted to a question at the conference of the Association for

Canadian Theatre Research in June 2003 for opening up this issue for

debate.

Return to Aritcle

14 See Derrida, Of Grammatology 47.

Return to Aritcle

15 The image of Chief Dan George from this original show is still

featured on the history page of the Vancouver Playhouse website. The

Internet, of course, extends exponentially the ability of genre to draw

borders of control and to normalize alterity under the rubrics of

liberal humanism or conservative privilege.

Return to Aritcle

WORKS CITED

Bakhtin, M. M. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Trans. V.W. McGee. Ed. C. Emerson and M. Holquist.Austin, TX: U of Texas P, 1986. 60- 102.

Bennett, Susan. “Radical (Self-) Direction and the Body.” Canadian Theatre Review 76 (1993): 37-41.

Rose, Chris, Kim Pemberton and Robert Sarti. “Bodies in the Barber Shop.” The Vancouver Sun Oct 22, 1988: A12.

Burke, Kenneth. On Symbols and Society. Ed. Joseph R.Gusfield. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1989.

Clements, Marie. The Accidental and Unnatural Women. Canadian Theatre Review 101 (2000): 53-88.

Derrida, Jacques. Glas. Trans. John P. Leavey, Jr. and Richard Rand. Lincoln and London: U of Nebraska P, 1986.

–––. Of Grammatology. Trans. Gayatari Sprivak. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 1976.

–––. Writing and Difference. Trans. D. B. Allison. Evanston: NorthWestern UP, 1973.

Elam, Harry. Email to the writer. June 28, 2003.

Freedman, Aviva, and Peter Medway, eds. Genre and the New Rhetoric. Critical Perspectives on Literacy and Education ser. London: Taylor, 1994.

Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny. Trans. David McLintock. Intro. Hugh Haughton. London: Penguin, 2003. 121-62.

Gilbert, Reid. “‘Shine on us, Grandmother Moon’: Coding in Canadian First Nations Drama.” Theatre Research International 21(1996): 24- 32.

–––. “Panych and Gorling’s The Overcoat: Silent remnants; new genres.” Siting the Other. Ed.Marc Maufort and Franca Bellarsi. Brussels: PEI-Lang, 2002.

–––. “‘Sheer’ Texts ‘Written’ in(to) Perception.” Modern Drama 45 (2002): 282-97.

Godard, Barbara. “The Politics of Representation: Some Native Canadian Women Writers.” Canadian Literature 124-125 (1990): 183-225.

Grace, Sherrill. Canada and the Idea of North. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2002.

Knowles, Ric. The Theatre of Form and the Production of Meaning: Contemporary Canadian Dramaturgies. Toronto: ECW, 1999.

–––. “Shakespeare, 1993, and the Discourses of the Stratford Festival, Ontario.” Shakespeare Quarterly 45 (1994): 211-25.

Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977. 1-7; 306.

–––. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book I: Freud’s Papers on Technique, 1953-1954. Trans. John Forrester. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988.

Luke, Allan. Series Editor’s Preface. Freedman and Medway. vii-xi.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Freedman and Medway 23- 42.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

–––. Mourning Sex: Performing public Memories. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.

Schryer, Catherine F. “The Lab vs. the clinic: Sites of Competing Genres.” Freedman and Medway 105-24.

Silverman, Kaja. Male Subjectivity at the Margins. New York and London: Routledge, l992.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London and New York: Verso, 1989.