The High School Theatre Enhancement Project in Newfoundland and Labrador with Special Focus on the Labrador Creative Arts Festival

Helen PetersMemorial University of Newfoundland

Note: the majority of the information reported here was first presented at the Shifting Tides conference in Toronto in March 2004; an update on the ongoing development of the project is included in the final section of this essay.

Résumé

Cet article décrit un projet élaboré par Lois Brown et Ruth Lawrence, des praticiennes avec qui l’auteure a collaboré à la dramaturgie et la mise en scène de textes pour la scène écrits par des enseignants et des élèves dans le cadre d’un festival de dramaturgie des écoles secondaires de Terre-Neuve et Labrador. L’auteure a été amenée à collaborer à ce projet entre autres grâce à une participation fréquente, sur une période de dix ans, au Labrador Creative Arts Festival et à une association avec des membres du Primus Theatre Company de Winnipeg (Manitoba). Une grande partie des travaux de fond sur l’anthropologie et le théâtre autochtone du Labrador effectué entre 1975 et 1992 ont été présentés dans une communication par l’auteure intitulée « Innuinuit Theatre Company: Postcolonial Aboriginal Voices in Labrador, Canada », lors de la 12e conférence de la Fédération internationale pour la recherche théâtrale (« Représentations passées et présentes : Tendances de la recherche théâtrale ») à l’institut de théâtre russe de Moscou en juin 1994.1 The High School Theatre Enhancement Project in Newfoundland and Labrador has come into being as an initiative of Lois Brown and Ruth Lawrence, two professional theatre practitioners based in St. John’s who have adjudicated various high school theatre festivals province-wide.1 Both adjudicators reported that in sub-regional, regional, and provincial theatre festivals student performance was invariably more engaging when the actors were working on locally written or collective plays because the material was speaking directly to, and was firmly grounded in, their own experiences, concerns, and interests. The writing also possessed a specific sense of humour understood by the students and audiences.

2 My personal experience in the project has been gained through participating in the Creative Arts Festival in Goose Bay, Labrador on six occasions between 1992 and 2002. In this festival, which began in 1975, all plays are written locally, either by a teacher, a student, a parent of a student, or collectively by student actors working with a teacher.

3 Based on our experiences, Lois, Ruth, and I formulated the high school project to try to accomplish two goals:

- To encourage more high school students to perform locally-written plays in their theatre festivals.

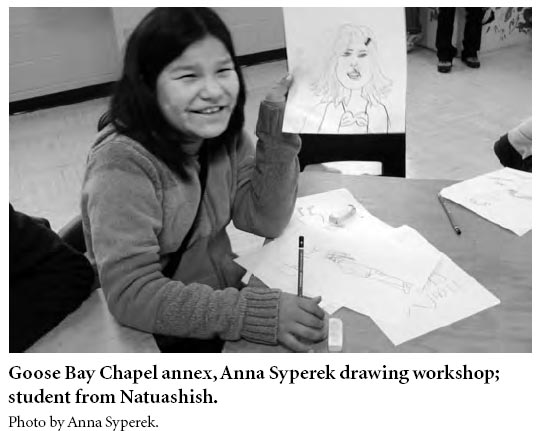

- To try to facilitate student and teacher creation of original plays.

We try to accomplish these aims by making selected theatre texts, which have been created in schools throughout the province, available to those teachers currently involved in directing student plays and their students as examples of what can be created in a school environment. The project has been supported by Memorial University of Newfoundland, which has made student assistance available for the editing process, and by the provincial Department of Education, which has provided dissemination of this work both in hard copy and on its website. Our proposal had two interrelated components:

- To produce a collection of six "How-To" essays on

creating theatre in high school. This material will be

available to the 191 high school teachers who are

currently involved in provincial theatre competition in

Newfoundland and Labrador via the Department of

Education website. We envisaged essays written by

teachers on such subjects as the following:

- • writing plays for small schools;

- • guidelines for collective creation;

- • individual (teacher or student) creation;

- • direction of such works;

- • other related topics, which may arise.

- To edit a selection of ten scripts that teachers choose to send to us that they consider to be best artistically and which they find to be most useful developmentally. These scripts will be available on the Department of Education website, where they can be downloaded for use by theatre teachers and their groups throughout the province.

We believe that the aim should be to distribute former and current teachers’ and students’ work throughout the high school system so that it can be performed again, perhaps far from where it originated. It should be possible for teachers and their students to perform each other’s texts or to adapt them for their own situations—to be able to say, "We can do this too."We hope this project will lead to an increase in Newfoundland and Labrador content at all levels of future provincial theatre festivals.

4 We acknowledge the value of existing published works that disseminate Newfoundland and Labrador theatre texts, such as Ed Kavanagh’s The Cat’s Meow: The Longside Players selected plays; Denyse Lynde’s Voices from the Landwash; Gordon Ralph’s Boneman: An Anthology of Canadian Plays and Collected Searchlights and other plays; Tim Borlase and Carol Bolt’s Who Asked Us Anyway?2; and Helen Peters’ The Plays of CODCO and Stars in the Sky Morning: Collective Plays of Newfoundland and Labrador. Our aim is not another book, but rather a web-based distribution of teacher and student theatre texts through the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Education.

5 We selected ten scripts from those submitted for the first collection of plays: five from Newfoundland and five from Labrador. Given the demographic and geographic distribution of our province, this equal weighting might require some explanation. Of our fewer than 540,000 remaining residents, fewer than 30,000 live in Labrador. Labrador’s theatrical creativity derives from the annual Creative Arts Festival, which began in 1975 and has fostered school theatre from grades three to twelve in Labrador schools.

The Labrador Creative Arts Festival

6 The Labrador Creative Arts Festival is the major venue for student theatre in Labrador. It is well supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, the Newfoundland and Labrador Arts Council, and businesses and individuals in Labrador. The event, which is a non-competitive but adjudicated festival, allows students from various communities in Labrador to make their situations known through theatre. This ability is important in this large and sparsely populated region where it is all too easy for people from distant communities to remain isolated. The important role which theatre now plays in Labrador did not come about accidentally. It is the result of an organized effort to involve school students, ranging in age from eight to eighteen, in collective theatre creation. Since 1975, the Creative Arts Festival founded by Tim Borlase and Noreen Heighton has been held annually in Goose Bay, Labrador during the third week in November to showcase student performing and visual arts. The Festival was established on two principles that ensure communication and involvement in the life of the region:

- That there is an expressed need for young people resident in Labrador—be they Innu, Inuit, Settler or Newcomer3—to know their past and their role in the developing Labrador community, to be active in the preservation of their heritage, and to be arbiters of their future.

- That there is a need to provide individuals with an opportunity to come together and share their creative experience. Through such a gathering, the geographical and social isolation of Labrador can be overcome and the participants can become aware of the varied and composite lifestyles in Labrador.4

The plays are meant to be original works. The students try to reflect in their performance—whether they are set in the past, present, or future—their perceptions of themselves, their home communities, and the wider community of Labrador in the world.

7 There are now more than 362 extant plays that have been performed in the Creative Arts Festival. In the 30 years during which the Festival has run, more than 3,176 students and 362 teachers, from as many as 16 communities in Labrador, have directly participated in the process of collectively creating and acting in plays. This represents almost 15% of the population of Labrador. Many student actors today are the children and grandchildren of earlier participants.

8 The Festival does not operate in isolation; rather, visiting artists from Newfoundland, the Maritimes, and across Canada are brought to Labrador for a week to share their skills and visions with students. These visitors include writers, visual artists, musicians, clowns, theatre practitioners, publishers, choreographers, photographers, illustrators, etc. Typically there are between 20 and 25 visiting artists at each Festival. They give workshops to students in singing, art, mime, dance, writing, puppetry, improvisation, etc., and they also give public presentations and performances of their own work following the nightly student plays. Not all visiting artists remain in Goose Bay for their entire week in Labrador; several are sent to give workshops for a day or two to those students who remain in school in their communities on the coast or in western Labrador.

9 The Festival has remained fairly constant in its organization and size, although there have been some losses as declining populations have forced school closures. Also, the Festival’s influence has spread throughout Labrador partly because of visiting artists but mostly because of the sense of family and community involvement that the students’ plays have generated. Before any plays are performed in the Festival, they are performed to packed houses in the communities to which their creators belong and whose stories they tell. (It should be noted that when many of the students perform at the Festival, their audiences are close to the size of the populations of the communities to which they belong.) The young actor/playwrights, particularly in the predominantly aboriginal communities, undertake responsibility for not offending their community elders. Again change can occur and occasionally the young actors will gently push the "ancestral envelope" where they feel it necessary.

10 These aboriginal students also create and perform among their peers, many of whom are more interested in becoming assimilated into the dominant white culture than in searching for and recreating their own cultural identity and spiritual traditions. The actors, then, feel that they are playing an ambassadorial role, and some of them report publicly to their Festival audiences the various combinations of dismissive indifference and youthful scorn they can encounter at home.5 However, in each of these young people who is dedicated to the process he or she has embarked on, there is a quiet sense of pride, a love of place, family and traditional values, and a commitment to carry on because they realize the value of what they do for their communities and for themselves. Their plays, over the years, have theatricalized the damage that "white men’s ways" have inflicted on their people, but now there is determination to put that behind and work out new empowered interrelationships (see Appendix).

11 The role that the Festival has played in the lives of those who have participated in it is large and calculable. Through their work, the young playwright/actors have developed significant theatrical expertise, and they have done so in a mix of races and nationalities, such as has been described by Homi Bhabha as an"emergence of the interstices—the overlap and displacement of domains of difference—[where] the intersubjective and collective experiences of nationness, community interest, or cultural value are negotiated" (2). Further, the Festival organization produces annual collections of student scripts for distribution to participating schools.6

Inuit Students’ Play Development

12 Inuit students have been involved in the Labrador theatre process since the Festival began in 1975. The traditional outlet for creativity in Inuit culture is storytelling and legends, not theatre, so narratives became the basis of Inuit student plays. Working within this tradition, students in Nain became participants in the first Festival. The scripts for the first three years have not been preserved, so the first extant play performed by the Inuit and students of mixed Inuit-white parentage in Nain is the 1978 play Okak Spanish Flu, 1917. This play tells how influenza, carried by sailors on a Moravian supply ship, the Harmony, reduced the Inuit population at the mission at Okak from 263 to 59 and destroyed forever the once thriving community of 350 Moravian, other Caucasian, and Inuit people.

13 In the years that followed, plays created by the students of northern Labrador in Nain and Hopedale focus primarily on the loss of spiritual values among the Inuit, increase of economic hardship, and introduction of social instability and family breakdown brought on by the spread of white settlement. However, attempts to bridge native and settler cultures have also been performed; in 1987 traditional drumming—outlawed for over 200 years by the Moravian missionaries—was used as a means of cultural exchange. The students began to use the Labrador dialect of Inuktitut together with English in their plays, and more plays began to deal with the resolution of Inuit problems caused by intercultural conflicts. Eventually, schools in the more southerly Inuit communities of Makkovik, Rigolet, Postville, and Black Tickle joined the festival.

Innu Student Acting and Innuinuit Theatre Company

14 Legend, which plays a large role in Innu culture, was theatricalized in One Summer’s Dream, the first play presented by students of Nukum Mani Shan School from Davis Inlet in 1987. The Innu students participated at the encouragement of Newfoundland teacher Lou Byrne. At this festival Byrne met Bill Wheaton (originally from Manitoba), who was teaching and directing student actors in Hopedale, Labrador (Wheaton later moved to Nain). Both teachers realized that working collaboratively could be a powerful and rewarding experience for their students. Innu and Inuit could compare their legends and their interactions with white people, and the Innu could learn from the experienced Inuit actors. Innu students from Davis Inlet acted with Inuit students from first Hopedale and later Nain during the years 1988 to 1993. They performed as Innuinuit Theatre Company and their productions dealt primarily with native legend and historical and contemporary native-white relations.

15 With the cooperation between Innu and Inuit students, the Innu language, Innu-aimun, also began to be used in performance with English and Inuktitut, rendering the works of Innuinuit Theatre Company trilingual. Innu, even young Innu, speak English only as a second language. The staging and costuming in Innuinuit Theatre productions involved extensive use of both aboriginal dress and period settler costumes. In addition, sets, lighting, sound, and use of contemporary aboriginal music became much more elaborate and effective. Proficient, enthusiastic traditional and contemporary dance was frequently used. In short, the productions became increasingly sophisticated, setting new and exciting standards.

16 Innuinuit Theatre Company performed six plays. Their last and best known is Kaiashits: The Boneman, which was performed in the Festival de Théâtre des Amériques in Montreal in June 1993 after touring in Labrador and Newfoundland in 1992. It directly and daringly portrays native-white relations resulting in the Innu people’s loss of their traditional hunting lifestyle and independence, and in the destruction of their aboriginal spirituality. This is a passion play in which Kaiashits, or the Boneman, the shaman who apportions caribou marrow to the people, is crucified by the white priest and settlers. In the play, Innu actors represent the Inuit, and Inuit actors their white antagonists. Speaking thoughtfully and sadly, in formal discussion with audience members following the performance of Kaiashits in St. John’s, Inuit students said that they felt uncomfortable playing the roles of hostile and controlling white people.

17 In the original performance of the play at the Creative Arts Festival, the two groups rehearsed separately until a couple of days before the performance, when the students arrived in Goose Bay. The play deals with the magic of Innu belief and nature. It uses dance, mime, music, and a style that is largely presentational. Kaiashits was written by Lou Byrne with assistance from Bill Wheaton after both teachers had worked with the students who improvised dialogue; it has subsequently been published by Byrne as the title play in the collection Boneman: An Anthology of Canadian Plays, edited by Gordon Ralph.7 The demise of Innuinuit Theatre Company in 1993 is regrettable, as it initiated a gap in Innu student theatre production in Davis Inlet that lasted until 2002.8

PRIMUS Theatre in Labrador, 1994 and 1995

18 In 1994 the organizers of the Creative Arts Festival invited PRIMUS Theatre Company of Winnipeg as visiting artists to perform and give workshops at the festival in Goose Bay. Members of PRIMUS Theatre at that time were artistic director (and former teacher) Richard Fowler; actors Donald Kitt, Tannis Kowalchuk, Stephen Lawson, Karin Randoja, and Ker Wells; and stage producer Laura Astwood.

19 This experience with PRIMUS demonstrated to the festival organizers that there was a fit between, on the one hand, the company’s dedication to its creative processes, practice, and priorities and, on the other, a creative need to be filled in the young Labrador actors. PRIMUS actors were graduates of the National Theatre School of Montreal who, upon graduation, joined Fowler to collectively create original theatre that was musical, physically challenging, beautiful, humorous, and provocative through the use of their talents, training, and life experience. As Fowler put it, "[M]ost of all I have tried to instil in them the belief and the understanding that the theatre can be a way to re-define inherited reality, be that reality political, physical, or psychological, and that through it we can create an alternative model for social—that is, human—interaction" (54). The young students on the Labrador coast want to make theatre out of their own experience effectively. However, they are influenced throughout the year by television as a model for their productions—not the best example for these isolated students with their heart-felt social responsibility, living so far and so differently from mainstream Canadian life. As a distinct alternative, PRIMUS Theatre was invited to Labrador for two weeks prior to the 1995 festival in order to work with students on their productions on site in three coastal towns: Hopedale, Rigolet, and Makkovik.

20 Six actors in pairs joined the three groups in their hometowns for the last two weeks of rehearsal, and they had to deal with the realities and constraints of all entrants in the Creative Arts Festival. The necessity of flying theatre companies to Goose Bay in propeller driven Twin Otters limits each cast to eight members and one or two directors, normally teachers. Only costumes, portable scenery, and small, light-weight props can be brought along. A list of other props required has to be submitted to the Festival Committee two weeks in advance.

21 Makkovik’s play, A Trip Through Time, deals with the Norwegian and Inuit ancestries of many Labradorians and the difference, not only between past and present, but also between the present-day reality of life in Labrador and external perceptions of that life. It combines the magic of a colourful, cardboard time machine with twinkling fairy lights, a "nerdy" operator, and the incongruous humour of a young time traveller, who dresses in the height of early-teen fashion from the local shopping mall as she meets her ancestors who live off the land in nineteenth-century Labrador.

22 Rigolet’s play, All That Glitters Is Not Gold, deals with increasing pressures to develop the natural resources of Labrador and the humorous but frightening conflict that arises between the big city developers and concerned local people over development of the Voisey’s Bay nickel deposit. The action is performed both on stage and in the auditorium and it conveys the vastness and the beauty of the threatened countryside. Conventional theatre lighting illuminates the action of the community on stage, but when local lads abduct the developer’s teenage daughter and hold her for ransom in a cave the only light comes from a single candle on the dark stage. The girl and one of her captors fall in love.As the young couple walk back toward the town the candlelight of the cave becomes magnified into a diffused golden glow, a sign of hope that grows into a new dawn to encompass the entire town.

23 Hopedale’s play, IkKaumajannik—Memories, dramatizes the way in which a teenaged girl comes to appreciate the culture and values of her grandmother—her annansiak. The play takes place near and in a graveyard, indicated by three simple, white wooden crosses that are moved as required by the actors. Three teenagers encounter the spirits of deceased annansiaks, silently miming actions that represent traditional Inuit women’s occupations and activities (building a cache for meat, sewing, playing cat’s cradle, etc.) The rebellious teenager is brought to value her Inuit roots by interacting with her annansiak’s spirit. Mutual acceptance is shown when both perform together the mimed actions, tasks, and games of the past and when the annansiak places her red plaid shawl around her granddaughter’s shoulders. Near the end of the play the girl spontaneously drapes the red shawl on the central cross. The theatre lighting focuses to a spot on the draped cross, presenting a powerful image.

The Theatre Enhancement Project

24 IkKaumajannik—Memories (1995) and Remember When (2002), another play from Amos Commenius School in Hopedale, are included in the collection. Remember When deals with Inuit people taking charge of their own affairs and facing up to problems common in all cultures, such as senile dementia. Both plays were directed by Norma Denney in their first productions. Also included is Something to be Proud of (2002), a play from B. L. Morrison School, Postville. Originally directed by Nancy Hall and Brandy Gillette, the play deals in a hilarious manner with central Canadian stereotyping of Labrador natives—and their resistance to that stereotyping. There are also two beautifully choreographed and highly sophisticated plays on youth: Jacob’s River (1998), which deals with life choices, and Corner of Jarvis and Queen (2002), a tribute by street people to the events of September 11, 2001, set in Toronto. These plays were performed by students of Goose High School, Happy Valley/Goose Bay, and directed by Dorrie Brown.

25 Our selections from Newfoundland are no less impressive: the St. John’s collective, The Twenty-Minute Psychiatric Workout (1986) from Prince of Wales College, which was directed by Lois Brown, is the mad-cap romp of a television psychiatrist and his patients. The Incident at Dusty Falls (1995) is a western romance with a dastardly villain written in English pantomime style, and Convergence (2002) dramatizes the co-existence in an old house of new residents and the ghosts of past owners. Both plays, written and originally directed by Levi Curtis, featured students of St. Joseph’s Academy, Lamaline. Deep Down (2003), originally performed by St. Anne’s School, South East Bight and written and directed by Elana Whyte, deals with the tragedy and heartbreak of the miners from St. Lawrence fluorspar mine who died of lung cancer.

26 Lois Brown and Ruth Lawrence’s roles in this project have included soliciting scripts, vetting of material received, assisting with the editing, and sharing their theatrical wisdom. My role is to edit the scripts into a uniform, complete format and to provide synopses of the plays, cast lists in order of appearance, brief character descriptions, stage descriptions, etc. In this work I have been ably assisted by Erin Murphy and Stephanie Short, senior honours English students who have worked with me through the support of MUCEP (Memorial Undergraduate Career Experience Program) grants. When we have edited the texts as completely as possible we will send then back to their teacher-directors for any necessary corrections, additional comments, and other information that they may care to provide. I am hopeful that receiving these texts will encourage some teacher-directors to submit an essay to us that will provide guidelines to help new teachers and their groups remount and indeed create their own plays.

27 My collaborators and I see this as a start. At the time of the Shifting Tides conference in Toronto, nine of the ten plays we had selected had been computerized and more than half of them had been through three or four stages of correction and standardization. We felt that it was realistic to aim to have the plays and essays available for the 2004-05 high school theatre festival season. We have also looked at different types of plays that can be added to the website, once the initial ten plays are completed: for example, Beni Malone’s adaptation of Goldoni’s classic Servant of Two Masters (1983); the collective adaptation of Peter Pan, Oh, Grow Up (1999), coordinated by Bruce Brenton and featuring two versions—one with a male Pan (with Wendy) and one with a female Pan (with Wendall); Natuashish resident Christine Poker’s play Orphan Boy (2002), which consists of narration and mime and shows an ill-treated orphan finding his rightful place in Innu society, first performed by Nukum Mani Shan School, Davis Inlet; and Bully Wise (2002), a play with no spoken text from the students of St. Michael’s School in Happy Valley/Goose Bay, on the widespread problem of bullying among the young.

28 We hope this project will allow the teachers and students who have created these plays to take pride in their accomplishments.We also hope it will lead to an increase in Newfoundland and Labrador content in sub-regional, regional, and provincial theatre festivals. We hope too that it will lead ultimately to the writing of more creative theatre texts in the province.

29 In Newfoundland and Labrador, new local play production flourishes in St. John’s, with the longstanding RCA Theatre operating out of the LSPU Hall; the year-round, prolific Artistic Fraud; and the new Rabbittown Theatre. Around the island, new plays, written by both established and beginning playwrights, are performed in established summer festivals such as Rising Tide Theatre’s Festival in the Bight in Trinity, the Stephenville Festival, and the Theatre Newfoundland and Labrador (TNL) Festival in Cow Head. In addition, new summer festivals come on stream annually with the mandate to stage new plays of relevance to the host community. We hope that our simple project will contribute to this dynamic and help to foster, at an early stage, the future development of our next generation of playwrights, actors, directors, and other theatre professionals.

Update on the project (2006)

30 The Newfoundland and Labrador High School Theatre Enhancement Project, consisting of an introduction, descriptions, teachers’ essays, and 14 plays has been available since January 2005 on the Newfoundland and Labrador government website (www.ed.gov.nl.ca/edu, follow links"K-12"and"Drama/Theatre").

31 It is difficult to say precisely what success the project has achieved. We know that months before the material was available online, several teachers asked for the essays and various play scripts. These were photocopied and mailed to the interested teachers via the Department of Education. The Servant of Two Masters was performed by an amateur theatre company in East London in the spring of 2005. A counter added to the project in January 2006 recorded 142 hits in January, 110 in February, 114 in March, and 99 in April.

32 I have recently returned from adjudicating the 30th annual Newfoundland and Labrador Provincial High School Theatre Festival in Grand Falls-Windsor, May 11-13, 2006. All students involved are given a certificate of participation, and, in addition, some thirty certificates of merit are awarded for superior acting, directing, costumes, lighting, sound, etc. In this provincial festival the ten best plays from the province’s ten regions are performed. Each regional festival features a competition involving six or seven plays. Of the ten winning plays showcased at the 2006 provincial festival, one play was collectively created by the cast, one was written by two students who also performed in the work, and a third was adapted in Goose Bay, Labrador from The Skid, a radio play by Thomas Lackey previously broadcast on CBC Radio. Lackey was also at the festival to see the stage premiere of his work and to give workshops to students and teachers. The remaining seven plays came from a variety of playbooks for young people; these were all published in the United States.

33 One local play, Out of Eden, was collectively created by students of Baie Verte Collegiate and explored the relations of "fem" and "malefem" (instead of man and woman), with God as a woman. This play is stylized, choreographed, and features a provocative fem Jocko and her put-upon partner malefem Adam—who, in a later scene in the play, is seen discussing his sense of inadequacy and unhappiness with a psychiatrist. In another, hilarious scene, the seductive barmaid Serpent tries to encourage a hopelessly inert couple to become interested in sex. She concludes that this human race is doomed to early extinction.

34 The other local play was 10 ½ Easy Rules, by Meghan Greeley and Mitchell McGee Herritt (Playwrights for Dummies Or Ten and a half Easy Rules for Putting Off the Perfect Play in Ten and a Half Not-So-Easy-Days with Ten and a Half Not-So-Easy-to-Come-By-Dollars). The play was performed by students of Regina High School, Corner Brook; Greeley and McGee-Herritt co-directed the production and acted as anonymous narrators manipulating their fellow actors, who (in the piece) are labouring to select a play that interests the students, complies with the dictates on subject matter of a fussy principal, and is feasible, given that there is no budget. Both Greeley and McGee-Herritt graduate this year and will attend the Theatre Program at Memorial’s Grenfell College in Corner Brook.

35 The fact that 30% of the plays that advanced to the Provincial High School Theatre Festival were of local provenance strikes me as being significant, as each was awarded the right to be there. The quality of both Out of Eden and 10 ½ Easy Rules is so strong that Lois Brown, Ruth Lawrence, and I believe that today’s teachers and students will themselves further the goals we set when we began the process of trying to enhance our provincial high school theatre.

Appendix

Adopting the Christian religion and settling in communities has affected both Inuit and Innu in Labrador. Both aboriginal groups were discouraged from retaining their own spiritual values and practices, encouraged to adopt Christianity as the true faith, and led into living in communities run by white people. However, the interactions of the two aboriginal peoples with their white religious and economic leaders were very different, even though the results for both groups have been unfortunately similar.

The Inuit were educated by Moravian missionaries who became resident in Labrador in the late eighteenth century. Historian James Hiller writes of how the missionary zeal of the Moravians to spread their faith was matched with a desire on the part of the British government and its Newfoundland representatives to confine the Inuit to Northern Labrador so that they would not interfere with, or be influenced by, white fishermen who were engaging (in increasing numbers) in the valuable fishery off the coast of Southern Labrador. Fluent in Inuktitut from their missionary experience in Greenland, the Moravians were able to speak to the Inuit in their own language. When the first mission was built in Nain in 1771 (it is still extant), the missionaries found that "Eskimo society was fluid, consisting of nomadic bands, apparently formed on a loose kinship basis. A band was usually led by an angakok (shaman)"; his prestige depended on the effectiveness of his spells in dealing with hunting success and curing sickness (78). Over time the Moravians provided for the economic and spiritual needs of the Inuit—ending their former roaming existence and their adherence to shamanism. The Inuit, who regarded the Moravians as a kind of angagkok and Jesus as similar to their major spirit Torngarsuk, wanted to worship in both camps, but over time they were convinced to see shamanism as wicked and Christianity as the true faith. The missions—Okak, founded in 1776 (closed in 1918) and Hopedale, founded in 1782 (still extant)—traded with the Inuit, both converted and heathen: "The Moravians kept tight control over the convert groups, and in doing so, disrupted the social solidarity of Eskimo society" (86). Continuing to erode faith and increase economic dependence, by the early nineteenth century the Moravians saw "[s]treams of Eskimos [come] to the missionaries to confess their sins, and many took the [heathen] ornaments off their clothing" (86). Native drumming, chanting, and throat singing were replaced by brass bands and church choirs.Over time alcohol and alcoholism became severe problems. Today, many Inuit are trying to recover spiritual values and practices from their pre-missionary past.

The Innu were ignored by the Moravians. Anthropologist Georg Henriksen writes that the Naskapi (who now refer to themselves as the Mushuau Innu) were not much affected by the white economy on the Labrador coast because they were not really integrated into the eighteenth and nineteenth century fur trade (Hunters 11). In the twentieth century, too, the Innu had little contact with white people until a Roman Catholic Oblate priest who could speak Innu-aimun visited the Davis Inlet area in 1924. From 1927 this missionary made annual visits to the Innu, who gathered to meet him at Davis Inlet in the summers. In 1952 the first resident priest took up residence there (13). During this period the Innu migrated west to hunt caribou on the central barrens in the fall and winter. In central Labrador, where they met only occasionally with white trappers, they trapped animals, hunted caribou, and practiced their tradition of mokoshan (sharing of bone marrow) to honour the caribou spirit in hope of continued success in the hunt. Henriksen writes, "An important point here, of course, is that nature and society coalesce in Innu cosmology. The spirits are everywhere in nature, and the Innu interact with the spirits all the time. The animal spirits sanction not only Innu behaviour toward the animals, but also how they let the animals enter human relationships through sharing, various rituals, and so on" (Life and Death 6).

In 1967 the Newfoundland government moved the Innu community from its summer location at old Davis Inlet to an island three miles away. The Innu call the new Davis Inlet "Utshimassit," which means in English "the place of the boss."They were encouraged to remain in the community full time, to try to fit into the Canadian-style economy, and to send their children to school. Schooling, Henriksen writes, created"a divide between the children and their parents and grandparents, the school made the older, ‘lost’ generation feel even more lost and powerless to effect any changes in their situation" (8). Feeling spiritually powerless, "they used alcohol in combination with drumming, singing and dancing in order to communicate with the animal spirits. However, the church forbade these practices and did its best to suppress them" (8). The church was not successful. In her M.A. thesis (Dalhousie University), Mary Ellen Macdonald writes, "When European religion finally did make a lasting impression, it was still not accepted unconditionally […] Animals, especially the caribou, were included in the Montagnais-Naskapi versions of Christianity, as were their communal values and anti-hierarchical, anti-authoritarian ethics"(23). Still, life was difficult for the Innu of Davis Inlet.

The Innu Nation and Mushuau Band Council held an enquiry in 1993 into the tragic deaths of six Innu children in a house fire in Davis Inlet on February 14th, 1992.At its conclusion the Innu resolved to make peace with the animal spirits and to stop"listening to the church telling us these beliefs were evil" (Innu Nation 167). However, during the mid 1990s there was extensive gas sniffing among young Innu.A move for the entire community to the mainland 16 km west of Davis Inlet on a traditional summer gathering place called Natuashish (Fork in the River) was negotiated with the federal government. The results of the move, which occurred over the winter and spring of 2002-03, are uncertain (Cooper 53).

Like their Inuit compatriots, the Innu are trying to regain some control over themselves, their lives, their beliefs, and their values. Neither group has an easy task.

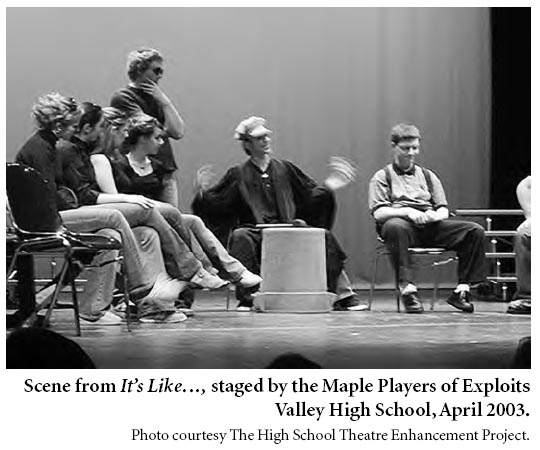

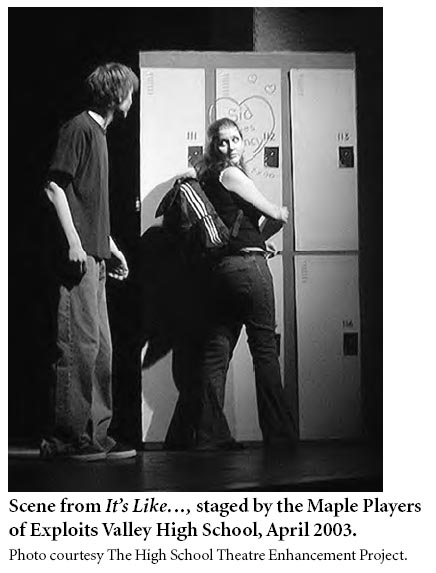

Images from The Labrador Creative Arts Festival

Scene from It’s Like…, staged by the Maple Players of Exploits Valley High School, April 2003. Photo courtesy The High School Theatre Enhancement Project.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

Bolt, Carol and Tim Borlase, eds. Who Asked Us Anyway? Goose Bay: Labrador School Board. Printed by Goose Lane, 1998.

Cheeks, Marion, prod. and dir. Now It’s Our Turn: The Spirit of the Labrador Creative Arts Festival. St. John’sWaterLandSky Productions, 2001.

Cooper, Bill. "Natuashish: Living the Move." Newfoundland Quarterly 96.2 (Summer 2003): 52f.

Creative Arts Festival. Annual Collection of Student scripts. Goose Bay, 1978-2005.

—."Handbook." Goose Bay, 1988-2005.

Fowler, Richard."Epilogue: Why Did We Do It." CTR 88 (Fall 1996): 54-55.

Henriksen, Georg. Hunters in the Barrens: The Naskapi on the Edge of the White Man’s World. Newfoundland Social and Economic Studies No. 12. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1973.

—. Life and Death Among the Mushuau Innu of Northern Labrador. St. John’s: ISER Research and Policy Papers No. 17. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1993.

Hiller, James K."Early Patrons of the Labrador Eskimos: The Moravian Mission in Labrador 1764-1805."Ed. Robert Paine. Patrons and Brokers in the East Arctic. Social and Economic Papers No. 2. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1971. 74-97.

Innu Nation and Mushuau Innu Band Council. Gathering Voices/Mamunitau Staianimuanu: Finding Strength to Help our Children. Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre, 1995.

Kavanagh, Edward. The Cat’s Meow: The Longside Players selected plays. St. John’s: Creative, 1990.

Lynde, Denyse, ed. Voices from the Landwash. Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 1993.

Macdonald, Mary Ellen. "The Mushuau Innu of Utshimassit: Paths to Cultural Healing and Revitalization." MA Thesis, Dalhousie University, 1995.

Peters, Helen, ed. The Plays of CODCO. New York: Peter Lang, 1992.

—. Stars in the Sky Morning: Collective Plays of Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John’s: Killick, 1996.

—. "Northern Lights – Labrador’s Creative Arts Festival 2002." Newfoundland Quarterly. New Series. December 2002. 45-47.

Plaice, Evelyn. The Native Game: Settler Perceptions of Indian/Settler Relations in Central Labrador. Social and Economic Studies No. 40. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1990.

Ralph, Gordon, ed. Boneman: An Anthology of Canadian Plays. St. John’s: Jesperson, 1995.

—. Collected Search Lights and other plays. Toronto: Irwin, 2002.

Notes