TheatrePEI:

The Emergence and Development of a Local Theatre

George BelliveauUniversity of British Columbia

Josh Weale

Graham Lea

Résumé

Dans le premier volet de cet article, Belliveau et Weale expliquent les circonstances qui ont mené à la formation du premier organisme de théâtre officiellement consacré à la création d’une dramaturgie propre à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard. Formé en 1981, TheatrePEI doit son existence à une jonction propice de l’histoire du théâtre canadien et des activités politiques de l’IPE. Dans le deuxième volet de l’article, les auteurs présentent quelques-unes des productions de TheatrePEI et examinent le contexte dans lequel ces oeuvres sont nées, pour ensuite se pencher sur la réception de quelques-unes d’entre elles. Leur objectif est d’examiner l’influence de TheatrePEI à l’échelle de la province.1 Despite the province’s long history of theatrical production and the presence of a major Canadian theatre festival (The Charlottetown Festival), TheatrePEI—which was inaugurated in 1980—was the first formal theatre organization dedicated to the development of distinctly local theatre on Prince Edward Island (PEI). The history of its creation lies in an opportune synergy between Canadian theatre history and PEI political activity. In this article we explore how a shared interest in localism among theatre artists and an activist Progressive Conservative government led to the creation of TheatrePEI in the early 1980s. In the context of this essay we define localism as the expression of issues relevant to a particular community.1 In examining specific PEI productions, as well as the conditions from which these productions emerged (and in certain cases the reception of the work), we explore the possible impact and meaning of TheatrePEI within the province.

2 In Reading the Material Theatre, Ric Knowles presents a desire to develop "modes of analysis that consider performance texts to be the products of a more complex mode of production that is rooted, as is all cultural production, in specific and determinate social and cultural contexts" (10). Knowles’s theoretical lens is informed by a combination of cultural materialism and semiotics. Robert Wallace, for his part, uses feminist and postcolonial theories in Producing Marginality to develop a framework to study theatre and social history by looking at "ways in which theatre both responds to and affects cultural and political imperatives in communities" (29). These two Canadian scholars emphasize the importance of understanding and studying the social, historical, and political contexts from which the theatre under investigation emerges—rather than solely focusing on, or analyzing, the resulting productions. As we investigate the emergence and development of TheatrePEI in this essay, a close analysis of the social, historical, and political conditions guides our exploration of the company’s various initiatives and productions. Specifically, we examine how the socio-political context largely shaped the creation of the company, and then how particular productions, with local themes and issues, were deliberately aimed to create relevant theatre for PEI communities.

The years leading up to the creation of TheatrePEI

3 Looking through the theatre archives at the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown, it becomes quite clear that until the 1970s theatre on PEI existed almost solely in the form of out-of-province touring companies or foreign plays (mainly from the U.S. and England) produced by local theatre groups.2 There was a decrease in touring after the 1970s, yet productions of scripts from outside of Canada continue(d) to take place in PEI. Nonetheless, a noticeable shift began to emerge in PEI, as in other parts of Canada, during the 1970s (and earlier in some regions) when a growing interest in producing theatre with local themes took place, moving from "colonialism to cultural autonomy" (Filewod vii). According to scholars, this national cultural shift in theatre was in part prompted by a change in the political climate, which saw "a groundswell of interest in Canadian history, culture, and institutions" (Benson & Conolly 85). The ‘Alternative theatre movement,’ as it came to be called, was named as such "because it was perceived to oppose the system of publicly subsidized civic theatres established across Canada in the late 1950s and early 1960s" (Filewod vii). This important movement in Canadian theatre history "may be said to have begun with [George] Luscombe’s founding of Theatre Workshop Productions in 1959" (20). Over the next decade it progressively gained momentum and arguably peaked in the early 1970s when in "the 1972-73 season nearly 50% of the plays produced by subsidized theatres in both English and French were in fact Canadian" (Wasserman 18).

4 As has been extensively documented, the Alternative theatre movement in Canada was assisted by new federal funding models, such as the Local Initiative Program and Opportunities for Youth grants. These funding sources encouraged artists to explore regional identities, and, as a result, theatre groups writing and producing plays about political, social, and historical issues rooted in local Canadian contexts emerged in various parts of the country. On the production side, dramatic techniques such as documentary storytelling and collective creation became staples of this theatre movement, partly as a reaction to the general lack of indigenous playwrights and/or plays, but also because these methods were ideal for the telling of stories grounded in the history of a local community.

5 One of the seminal examples of this form of collective and consciously local theatre is, of course, Theatre Passe Muraille’s 1972 production of The Farm Show. This show was viewed as groundbreaking from the perspectives of both dramatic technique and subject matter. According to Don Rubin, artistic director Paul Thompson turned Passe Muraille into a "Canadian experimental house, [in that of] the 50 or so productions done at Passe Muraille between 1970 and 1973, about 90 percent were new plays by new writers from various parts of the country" (315). The collective creation process in The Farm Show required the creators to study local characters, to listen to local stories, and to work the land. In some ways The Farm Show turned localism into art, in that Thompson saw this development of indigenous theatre through exploration of place as a means of asserting local autonomy in the face of colonial influences. Thompson suggested in an interview that The Farm Show was a conscious exploration of localism as a defence against cultural imperialism (Johns 31).

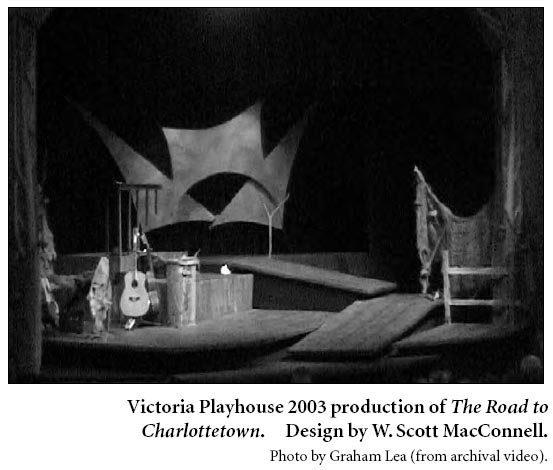

6 During the 1970s on PEI the most significant examples of this

type of collective style of theatre with local themes came in the

form of two significant dramas: The Chappell Diary (1973) and

The Road to Charlottetown (1977). The Road to Charlottetown was

the product of a collaboration between PEI poet Milton Acorn and

actor/musician Cedric Smith. Although initially produced in

Ontario for a prison tour, the play was brought to the

Confederation Centre of the Arts in the summer of 1977. Through

the poetry of Acorn, The Road to Charlottetown is thoroughly

grounded in the land and people of PEI. Co-creator Smith had

been involved in a number of collaboration projects with

Luscombe at Toronto Workshop Productions, which had included

composing the music for the documentary drama Ten Lost Years

(1974) based on the book by Barry Broadfoot. Smith’s experience with collective creations, and the agrarian sensibilities he shared

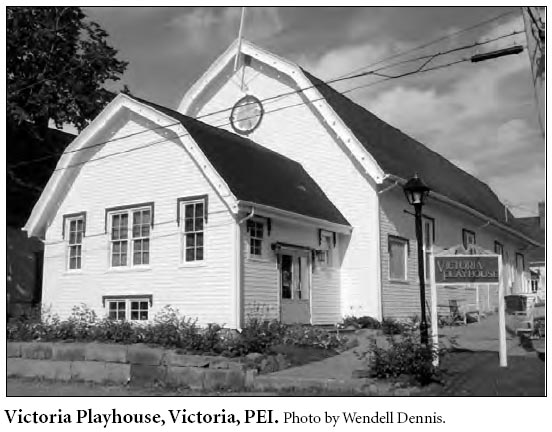

with Acorn, helped foster a non-linear drama that weaves back and

forth in historical time. Described by Smith as a "People’s Passion

Play," The Road to Charlottetown "is a fantasy based on the tumultuous truth of the Island Land Struggle, by tenants victimized by

landlordism." The play tells the story of Islanders, working on the

land, who had to pay hefty rents to often absentee landlords.

Through a series of 20 vignettes, the heroism of everyday Islanders

against the promises of "eternal tenantry and toward socialist

ideals is played out" (Acorn, Program notes). The chorus written

by Smith that bookends the show and is sung by the entire cast

suggests this relationship between character and place:We came from the sea, we were swept to the shore,

And we cling to the land like our ancestors before,

And we work with the nets, and we work with the plough

As the seasons pass and the centuries bow.

The brooding hills at our back, the swollen sea in our face,

We have carved a slender hold in this unprotected place,

And we harvest hills and harvest the swollen sea,

To our sons leave a trace of where we used to be.

And we came from the sea. (10)

The 1977 production of The Road to Charlottetown offered Prince

Edward Islanders one of the first examples of theatre’s potential for

bringing to life a distinctly Island story grounded in the local landscape. Unfortunately, it proved to be a disappointment at the box

office,3 and according to Ron Irving this dissuaded the

Charlottetown Festival from further experimentations with this

style of local documentary theatre. A re-mounting of The Road to

Charlottetown at the Victoria Playhouse in 2003 will be discussed

later in the article.

7 Work on The Chappell Diary began in 1973 as a collaboration between Island theatre artist Ron Irving, Island historian/activist Harry Baglole, and a group of actors who, for a number of years, were referred to as the Hall Players. (The actors took on that name because this show and others they worked on were designed to tour across PEI, playing in various small community halls.) Irving led the group of actors to create a drama based on the diaries of early Island settler Benjamin Chappell. The historical subject matter was complemented by the collective approach, and the drama explored the struggle of eighteenth-century British settlers engaged in the creative act of transforming a wild landscape on PEI’s north shore into a pastoral one.

8 What becomes quite apparent after analyzing both The Road to Charlottetown and The Chappell Diary is the sense of nostalgia within the texts, a romanticized and idealized view of local history (particularly in The Chappell Diary). This approach differs from The Farm Show where artists in the Passe Muraille collective were in a number of ways creating history by interviewing locals and then theatrically representing and documenting their lives and stories on the stage. The PEI plays were based on documented, archived research, and in the case of The Chappell Diary the actors were primarily from the local area re-telling and re-imagining their history. In the case of The Farm Show, the actors were largely from urban Toronto and they were trying to capture the lives of rural farmers. As a result, a certain anxiety permeated the creative processes—as they tried to ‘get it right’—as becomes quite evident in Michael Ondaatje’s documentary film The Clinton Special: A Film about The Farm Show (1974). Through various scenes in the film it becomes apparent that the actors seemed desperate to have "the farmers ‘like’ the show" (Harrison 1). Because the play was meant to be both about and for the farmers, a pressure to please, versus a critique of the farmers’ lives, was placed upon the actors. The Chappell Diary and The Road to Charlottetown depict non-living characters, and as a result the actors/creators were given freedom to re-imagine and creatively construct idealized characters. Consequently, these PEI plays inherently hold a nostalgic perspective, with a certain romanticized depiction of the past for their contemporary audience.

The genesis of TheatrePEI: socio-political climate

9 Throughout the 1970s, when PEI theatre artists and activists were beginning to explore the stories of their agrarian past, the abandonment of this way of life was being accelerated by the 15-year development program of modernization introduced by the Liberal government of Alec Campbell. While many aspects of this program, such as the development of infrastructure, were seen in a positive light, by the late 1970s a backlash was beginning to mount against the social reorganization that had accompanied this modernization. In general, this backlash focused on the amalgamation of services, the centralization of power, and the industrialization of agriculture and fisheries. This process was widely seen to be manifesting itself in the weakening of traditional local communities (MacLean 230).

10 Throughout the 1970s an activist group known as the Brothers and Sisters of Cornelius Howatt began protesting this centralizing program. They were named after Island politician/ farmer Cornelius Howatt, who had vehemently opposed PEI’s entrance into Confederation and the loss of local autonomy it would precipitate. This group of farmers, artists, and activist constituted a political wedge that would lead to full blown political backlash by the end of the 1970s. In 1980 former MP and blueberry farmer Angus MacLean’s Progressive Conservatives came to power on a platform of "Rural Renaissance." His campaign, which was supported by several members of the Brothers and Sisters, was based on fiscal responsibility, self-sufficiency, and reinvigorated local communities (MacLean 238). In regards to cultural development, MacLean’s government favored a decentralized approach and saw the province as a community of communities.

11 Seizing the opportunity that this political development represented for theatre artists, a group of Island citizens, including Harry Baglole (who had been active in both the Brothers and Sisters of Cornelius Howatt and MacLean’s election campaign), submitted a proposal for the creation of a Community Theatre Program on PEI. Throughout the proposal the authors consciously appealed to the desire of the government to foster a more localized sense of community. The proposal, written by Baglole in 1980, began by appealing directly to the stated mandate of the new government:We believe this program to be precisely in line with the cultural policy of the present Island Government, as articulated before, during, and since last year’s election. There have, for example, been commitments to decentralize the arts by encouraging the revival of cultural activity in small halls and community centres in all parts of the Island, and to encourage the celebration of the Island spirit in traditional music, dancing, literature, and other forms of cultural expression. (1)

12 This mandate to stimulate activity in small halls and community centres was one that bore a resemblance to the localized focus of the Alternative theatre movement. It was therefore a mandate that the promotion of this brand of theatre could help to fulfill. In this spirit, the proposal also attempted to differentiate theatre as a medium from mass media in terms of both commercialism and social organization:We live in a passive age. For entertainment, most of us depend on slick, innocuous (or sometimes not so innocuous) media programs concocted mostly in the United States and delivered to us courtesy of Anacin, General Motors, Coca Cola, and the purveyors of assorted deodorants and breath sweeteners. We no longer very often gather with friends and neighbours to share stories; less often do we perform plays for each other; almost never do we attempt to create our own dramas, telling of our own lives and communities. (1)In making a case for the creation of a Community Theatre Program, Baglole differentiated the more participatory nature of the theatrical medium from the passive, consumptive mass media. He also invoked the anti-American nationalism that was near the heart of the Alternative theatre movement of the 1970s. The explicit arguments were that theatre is a form of communication more conducive to localized social organization than the mass media of film or television. The proposal also went on to describe the types of theatre productions and activities envisioned by its authors. In general, these could be divided into two groups: telling their own stories and solving their own problems. In describing the need for Islanders to tell their own stories Baglole appealed to the new government’s agrarian sensibilities:We Islanders are a strangely inarticulate people. This past generation has seen the passing almost of an entire way of rural life, and although there has been much anguish, the experiences of those thousands of families who moved from farms has not found expression in a single highly memorable play, novel, poem, or short story. We anticipate that the Community Theatre Program will help Islanders to find their own individual and unique voices; to speak and to act. (1-2)

13 Similarly, in outlining the activist uses of theatre, the proposal also described the desire to enable small communities a forum for engaged localized communication:Dramatic techniques are powerful tools of communication. The resources of the Community Theatre Program will be available to community groups who may wish to educate and inform about issues such as drug abuse, land use, the problems of the handicapped, etc. (3)The proposal was accepted and the Island Community Theatre was incorporated in 1980. Ron Irving accepted the position of executive director and would serve as advocate, educator, and artistic director in fulfillment of the organization’s diverse mandate. The name of the organization would soon be changed from Island Community Theatre to TheatrePEI in order to avoid being viewed as an amateur theatre group when seeking Canada Council funding. In the role as artistic director, Irving and his successors Elizabeth Muir and Rob MacLean (son of premier Angus MacLean) produced a body of work that focused on both telling Island stories and creating a forum to discuss social problems.

TheatrePEI: Productions and Initiatives

14 During its twenty years of producing theatre—from 1981 to 2001—TheatrePEI mounted dozens of original theatre productions and served as the only year-round producer of professional theatre on PEI. The company staged several productions on educational topics ranging from racism to environmentalism, with the majority of them touring PEI schools. Some of these touring plays included Mother Earth Blues (1982), Water Wise (1984), May the Forest be with You (1985), and Racist! Who me? (1995). Practically all of these shows were collective creations and offered young, local actors a first opportunity in writing and acting for the stage. The collective approach was also used to create special interest shows including The Venerables (premiered 1984), a long-running play performed by seniors about the foibles of aging, The Postal Show (1992), which dealt with cutbacks to Canada Post’s rural service, and The Patronage Show (1998).

15 TheatrePEI also produced mainstream shows that dealt with issues pertinent to the community. One example was a production of David Mamet’s Oleanna in 1995, which played in the midst of a highly publicized case of sexual assault that occurred on the University of Prince Edward Island campus. This production invited the community to participate in the dialogue initiated by the presentation by holding mediated discussions with the audience, actors, and director after each performance.

16 Plays by established PEI writers such as Adele Townshend, Michael Hennessey, and David Weale were also produced by TheatrePEI. Notable examples include Townshend’s For the Love of a Horse, which had received a glowing review by Dora Mavor Moore in the 1968 Canadian Playwriting competition, yet had not received a full scale production until it was mounted by TheatrePEI in 1986. Michael Hennessey’s Trial of Minnie McGee, which tells the story of the last woman sentenced to death on PEI (and bears a strong resemblance to Sharon Pollock’s Lizzie Borden play, Blood Relations) was successfully produced by TheatrePEI in 1983. Island folk historian David Weale’s drama A Long Way from the Road was produced by TheatrePEI in 1994.Weale’s production spawned a revival of local storytelling across PEI, and in many ways encouraged other artists to share local stories through this long-time tradition on the island. TheatrePEI also developed the New Voices Playwriting contest, through which it encouraged and workshopped new theatre pieces, some of which were eventually developed into full productions. These various TheatrePEI initiatives encouraged theatre activity within the province, and the subject matter of the productions frequently fulfilled one of the organization’s stated mandates, that of telling our own stories. It should be noted that the cited productions are not an exhaustive list; instead they represent the type of themes represented in TheatrePEI productions.4

17 Despite the apparent success of TheatrePEI in the fulfillment of its mandate, the organization’s budget was severely cut in the late 1990s, which, coupled with an accumulated debt, forced the organization to stop acting as a producer (Binkley).5 While TheatrePEI continues to promote new play development through playwriting contests, staged readings, community festivals, and workshops, it is hard to see the end of production as anything but a major setback to the organization’s vitality. Fortunately, among the final plays that TheatrePEI staged before they ended production, were perhaps two of the most effective new works in terms of its founders’ desire to address issues relevant to the community: Rough Waters by Melissa Mullen and Horse High, Bull Strong, Pig Tight by Kent Stetson.

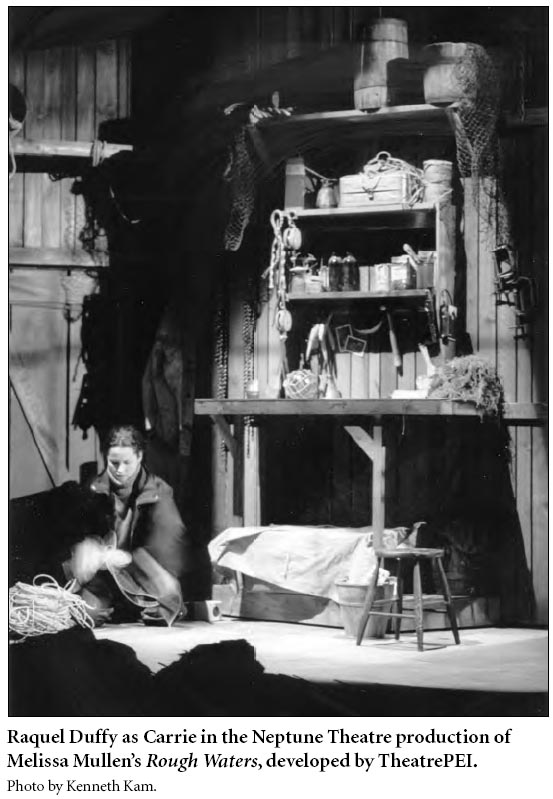

18 Rough Waters was initially workshopped in 1997 during an intensive three-week play development program within the auspices of TheatrePEI’s New Voices competition. With the guidance of Bruce Barton as dramaturge and the actors who participated in the workshop, Mullen refined her family drama for its 1998 semi-professional Charlottetown production and an eventual PEI tour. Less than three years later Rough Waters was part of Neptune Theatre’s main season, and the Halifax, N.S. production received "strong reviews and even stronger public response" (Barton 342).

19 Rough Waters is a family drama that uses the gradual abandonment of a traditional way of life in the fisheries as its backdrop. The story’s central conflict is between a father and son. The father, Gordon, has inherited his own father’s conservative approach to fishing, while the son, Jamie, hopes to start a fish farming business with his more entrepreneurial uncle Wayne. Within this generational divide we see the progression from viewing the fisheries as a way of life to its status as an industry. Further, we see the inner conflict within the father between his desire to preserve this way of life, which his daughter Carrie so admires, and his desire to provide the financial security for his family that his brother Wayne enjoys. While the play does not seek to pass any finite judgment on this notion of progress, it does portray the tension that this type of profound cultural shift inevitably precipitates.

20 Although the play contains a sense of nostalgia in terms of what the fishing industry ‘used to be like,’ Mullen refrains from sensationalism in that there are "no extended political manifestos or declarations on the plight of beleaguered fishers" (Barton 343); as a result, the play distinguishes itself from other works from the Maritime provinces that often sensationalize the hardships of fishing, farming, or mining communities. Instead of creating a romanticized depiction of a fishing community, Mullen manages to depict characters in Rough Waters who possess "an earnest engagement with the personal, social, and cultural forces that shape a significant portion of rural Maritime lives" (Barton 343).

Raquel Duffy as Carrie in the Neptune Theatre production of Melissa Mullen’s Rough Waters, developed by TheatrePEI. Photo by Kenneth Kam.

Display large image of Figure 1

21 In internationally acclaimed playwright Kent Stetson’s Horse High, Bull Strong, Pig Tight we get a more one-sided, yet no less complex perspective on the abandonment of agrarian life. Stetson’s one-person show, which received the Wendell Boyle Award for theatre and heritage in PEI, premiered in 2001 in Charlottetown before touring parts of PEI, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Despite its limited productions to date, the play was well received in Charlottetown according to critic Sarah Crane, as "the audience was left roaring several times" by the phrases and self-recognition (8). Stetson invites the audience to witness the abandonment of agrarian life through the eyes of one Peter Stewart. Over the course of the play, Stewart displays an almost holy reverence for the work of the farmer. And, most interesting, Stetson consciously counter-balances contemporary life with a nostalgic sense of the past.

Young Jimmy—The Fool’s boy—

Steps away from his computer screen,

Walks out the door...

He might as well be on Mars

For all he knows of the red Island soil

Them ‘made in Japan’ sneakers lands on.

"The kids is born here," says Harry.

"They eat and sleep and go to school here.

But their souls are made in America.

The almighty dollar is their Heavenly Father these days.

Their father which art in Washington."

Harry was not fond of the Yanks.6

He’d make you wonder.

Our own Island youngsters,

Threatenin’ to blow up Colonel Grey,

And shoot each other for wearin’ the wrong brand name.

Like they seen on the T.V.

America’s Most Wanted?

I think it’s the souls of our children

God bless America, wha?

My soul grew in the fields and barns and kitchens.

My computer was a one room school.

My television was a fiddle or a card party.

Or Harry Muttart’s store Saturday night after barn work.

I knew the same songs and stories as my neighbors.

I knew their children, and their parents.

And their parents.

I knew every house and who was in it for miles in each direction.

Our Heavenly Father lived in St. Columba’s Presbyterian Church.

Right there.

And He was a farmer.

A good farmer just like us. (399)

22 Throughout the above passage (and the play) Stetson creates a

character in Peter Stewart who has developed an uncompromising

belief in the connection between the land and the "soul." Stewart

clings to the past with roots so deeply connected to the land that he

would rather die than sever the link. In one of the most memorable passages of the play Stewart quotes his beloved Lily, who

actually describes the connection in physical terms:When you’re born on the Island

The second they cut your umbilical,

Another cord sprouts out ‘a your navel.

Shoots right out and plants itself in the soil

Takes root in the bedrock.

You’re attached to P.E.I. forever.

It’s made outa’...well, ah...light.

Golden-red light.

It’s right-flexible, eh? Tough. Right elastic.

You can go pretty much anywhere on the earth

And it’s still there,

Sprouting outa’ yer belly

Attached to the red rocks of home.

Anywhere but Toronto.

Starts to fray the minute you get off the bus in Toronto. (413)

23 Indeed, Stewart is so thoroughly connected with the land— and, in particular, his land—that in the end his very life is connected with the fate of the farm. When all hope seems to be lost, and doom to both Stewart and his land seem inevitable, Stetson, in a wonderful act of optimistic imagination, has Stewart’s grandson use his computer and the interactive powers of the Internet to save the family farm from the clutches of the agri-business corporation Margate Farms. The complexity of Stetson’s tale largely results from the redemption of this new media that Stewart had blamed for his son’s and grandson’s alienation from the land.

24 Stetson’s play differs from Mullen’s in its depiction of nostalgia, in that Horse High, Bull Strong, Pig Tight romanticizes, to a certain extent, ‘the way it used to be.’ The overt political statements in Stetson’s play on current commercial enterprises overtaking small PEI farms directly addresses the plight of contemporary farmers. The protagonist is presented as an individual caught between "the modest, Island way of life he used to know, and the threatening encroachment of technology, big business"—particularly large agricultural enterprises that overtake smaller farms (Crane 8). This depiction of Stewart, rooted in an idealized past, differs from the characters in Rough Waters, who seem to defy the stereotypical portrayal of the‘long lost days of the past.’ The romanticized history alluded to in Stetson’s play through Stewart’s clutching of a semi-idealized past reflects the notion of a created stereotypical culture which serves to sell (to tourist audiences in particular) a romanticized view of PEI.

25 While agriculture remains a significant portion of PEI’s

economy, "tourism […] seem[s] set to overtake agriculture as the

province’s economic leader. The working rural landscape that had

defined Prince Edward Island for Islanders [is] now equally important as a tourist attraction"(MacDonald 382). In an article in 1986,

Elizabeth Mair commented that the work of TheatrePEI had

enabled "Island theatre […] to emerge at last from the shadow of

the Charlottetown Festival, and to be finding a genuine island

audience. But as long as theatre stays dependent on tourist tastes

[…] there will remain a split in focus"(22). The increasing importance of the tourist trade to rural PEI is perhaps best highlighted in

The Road to Charlottetown. In the scene entitled"Tourist,"a tourist

is confronted by a group of ‘land activists’ who are posing as road

workers.OLD JOHN. Tell me, sir, would The Island be quaint enough

for ye, then?

ANGUS. Ah, the blessings of fresh ocean air! A place of leisure

and contentment.

DAVEY. Where the sun shines every day and tomorrow’s

problems never arrive.

OLD JOHN. A dreamy never never land (31).

With this, the ‘Islanders’ have summarized much of the

manner in which PEI has been marketed to tourists. This

idyllic version of "The Island" is not completely accurate,

as the tourist soon discovers:TOURIST. [But the brochure] also said that the Islanders were

a gentle, friendly people.

OLD JOHN. Indeed, for the most part, sir. But we keeps a few

around what ain’t for when the situation needs it!!! (31)

The contrast between what is shown for tourists and the actual

lives of people takes on a heightened meaning when presented in

PEI communities where this takes place. This short scene recognizes the dual existence of the local audience as they struggle to live

their own lives and to accommodate the tourists who help drive

the economy. At the same time, the scene reminds the tourist audience of the sanitized view of reality presented to them.

Residual effects of TheatrePEI

26 Although TheatrePEI no longer directly produces theatre, its impact and legacy continue to be felt in the development of new works, along with an audience eager for local theatre. There has been a great deal of theatrical activity resulting both directly and indirectly from the organization’s existence, and there continues to be interest in telling and hearing local stories. In the years since TheatrePEI slowed its production, a number of independent producers have sought to capture a local audience through indigenous productions. For instance, the Victoria Playhouse, which traditionally produced a typical mix of light summer stock fare, has had at least one locally created play in each year since TheatrePEI stopped producing. Since the late 1990s, they have staged two comedies by Island writer Pam Stevenson (Conjugal Rites in 2000, The Haunting of Reverend Hornsmith in 2001), a period drama by Lars Davidson (Adrift in 2002), a storytelling show by artistic director Erskine Smith (The Most Amazing Things in 2000), and two runs of New Brunswick playwright Charlie Rhindress’s Maritime Way of Life in 1999 and 2001.7

27 As part of its goal to produce more local theatre, The Victoria Playhouse remounted Acorn and Smith’s The Road to Charlottetown in 2003, directed by Cedric Smith himself. The theatre’s setting in the tiny fishing and farming village of Victoria, PEI offered a beautiful compliment to the play’s agrarian themes. Smith gave the play an added touch of localism by using props scavenged from the village’s shoreline: driftwood served as prop pistols, pitchforks, benches, and shillelaghs, sandstone served as coins, costumes were sewn with shells and seaweed. The show opened with the blowing of a conch shell that had served as a doorstop in a Victorian home for close to a century.

Victoria Playhouse,Victoria, PEI. Photo by Wendell Dennis.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

28 In exploring the emergence and eventual development of TheatrePEI from a social, political, and historical perspective, this essay has aimed to offer insights and perspectives on an important theatre initiative on Prince Edward Island. In discussing the political climate that led to TheatrePEI and examining particular productions, we have tried to demonstrate how the company’s intended mandate was partially realized. The intentions of TheatrePEI remained closely focused on creating theatre about and for local audiences. How these intentions were received and the impact the localist approach has had on communities in PEI is beyond the scope of this essay (although worthy of further inquiry). To conclude, we turn to Knowles once again. He proposes that we consider "theatrical performances as cultural productions which serve specific cultural and theatrical communities at particular historical moments"(10). TheatrePEI emerged at a time when theatre in many parts of Canada was expanding and (re)inventing itself, when the Conservative PEI government wished to look at ways to celebrate the small and capitalize on the strengths of its individual communities. Given these conditions, it seems reasonable to consider TheatrePEI’s cultural legacy as a theatre that aimed, developed, fostered, and produced work relevant and meaningful about and for locals on PEI.

Works Cited

Acorn, Milton. Program Notes for The Road to Charlottetown. Reprinted as an insert into the 2003 Victoria Playhouse program, 1977.

Acorn, Milton and Cedric Smith. The Road to Charlottetown. Ed. James Deahl. Hamilton: UnMon Northland P, 1998.

Baglole, Harry. "Community Theatre Proposal." PEI Department of Community Affairs, 1980.

Barton, Bruce, ed. Marigraph: Gauging the Tides of Drama from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. Toronto: Playwrights Canada P, 2004.

Benson, Eugene and L.W. Conolly, English-Canadian Theatre. Canada: Oxford UP, 1987.

Binkley, Dawn. Personal interview. July 2004.

Crane, Sarah."Meaning of Island Life: Review of Horse High, Bull Strong, Pig Tight." The Buzz. January 2001: 8.

Filewod, Alan. Collective Encounters: Documentary Theatre in English Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1987.

Harrison, Flick."Review of ‘The Clinton Special: A film about the Farm Show.’" <http://www.vivelecanada.ca/article.php/20031022111115356/print> Last accessed 7 May 2006.

Irving, Ron. Personal interview. July 2004.

Johns, Ted. "An Interview with Paul Thompson." Performing Arts in Canada 10.4 (1973): 31-33.

Knowles, Ric. Reading the Material Theatre. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2004.

MacDonald, Edgar. If You’re Stronghearted: Prince Edward Island in the Twentieth Century. Charlottetown: Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, 2000.

MacLean, Angus. Making It Home. Charlottetown: Ragweed P, 1999.

Mair, Elizabeth."Theatre: Who’s it For?" Canadian Theatre Review 48 (Fall 1986): 19-22.

Mullen, Melissa. Rough Waters. Barton 341-88.

Ondaatje, Michael. The Clinton Special: A Film about The Farm Show. Toronto: Mongrel Media, 1974.

Peake, Linda M."Establishing a Theatrical Tradition: Prince Edward Island, 1800-1900." Theatre Research in Canada 2.2 (Fall 1981): 117-32.

Rubin, Don, ed. Canadian Theatre History: Selected Readings. Toronto: Playwrights Canada P, 1996.

Smith, Cedric. Director’s Notes for The Road to Charlottetown. Printed as an insert into Victoria Playhouse program, 2003.

Stetson, Kent. Horse High, Bull Strong, Pig Tight. Barton 393-423.

Wallace, Robert. Producing Marginality: Theatre and Criticism in Canada. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Fifth House, 1990.

Wasserman, Jerry. Modern Canadian Plays, Volume 1. 4th edit.Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2000.

Notes