"The Beauty of Holiness:"

Politics and Allegory in Mary Kinley Ingraham’s Acadia

Kym BirdMcGill-Queen’s University Press

Résumé

Cet article examine la pièce Acadia de Mary Kinley Ingraham en sa qualité de pièce baptiste et féministe. Dans un premier temps, l’auteure situe l’œuvre dans le contexte d’une tradition baptiste néoécossaise, une dénomination protestante dont l’histoire évangélique repose sur la création de mouvements de réforme sociale axés sur l’évangile et la morale. Celle-ci aurait d’ailleurs appuyé les premières présences de femmes dans les milieux professionnels et les premières revendications féminines pour le droit à l’enseignement post-secondaire, entre autres. Dans un deuxième temps, Bird inter-prète la vie personnelle et professionnelle d’Ingraham comme étant représentative de ses influences baptistes. En effet, Ingraham était issue de la classe moyenne anglo-canadienne et était la fille d’un ministre baptiste. Grâce à son privilège social et professionnel, armée de son zèle évangélique, elle a lutté pour obtenir des livres pour des centaines d’avant-postes des Maritimes et a fait du métier des bibliothécaires une véritable profession. Ingraham était une candidate toute désignée pour la Baptist University, et c’est son amour manifeste pour cette institution qui lui a inspirée quatre livres et une pièce de théâtre. Acadia fait partie d’un cycle d’allégories politiques et religieuses écrites par des dramaturges canadiennes au début du vingtième siècle. La pièce remet en question certaines idéologies patriarcales omniprésentes en investissant les revendications de femmes à l’action et au pouvoir social d’un esprit chrétien et en célébrant la maternité comme étant la condition sine qua non d’une culture chrétienne. La pièce Acadia, surtout, présente une quête baptiste pour la connaissance de soi dont les moments symboliques sont liés à l’histoire libérale de la Acadia University, accordant une importance toute particulière à la voix de l’égalité dans le débat sur l’intégration des femmes. Elle présente également au féminin la lutte allégorique pour l’édification spirituelle et politique, concepts qui sont à la base de la représentation baptiste du monde, en l’imaginant comme lutte entre mère et fille. Il s’agit donc en un sens d’une allégorie du féminisme domestique, dans laquelle la supériorité morale de la femme est représentée par Acadia qui vit une conversion spirituelle et connaît la Vérité.Above them all the Truth did call to me,

"O daughter, rise and be.

In lowly Scotian vales my people pray;

Arise, and gather them to me;

Gather my people to their ancient fold." (3)

1 These opening lines of Mary Kinley Ingraham’s 1920 verse drama Acadia describe a momentous birth. In the poetry and passion of a Baptist revival, the deity and mother Truth calls into being the figure of Acadia, the daughter of the Second Great Awakening, progeny of New Birth and the desire for intellectual increase. Perhaps these lines also allegorize Ingraham’s own call to serve God.

2 This paper considers Acadia as a Baptist and a feminist play. It situates the play in the context of the Nova Scotia Baptist tradition, a Protestant denomination whose evangelical history had much to do with creating the social gospel and moral reform movements that supported women’s first forays into the professional world and their earliest demand for rights, including their right to a college education. It reads Ingraham’s personal and professional life as representative of these influences. She was middle-class, Anglo-Canadian, and the daughter of a Baptist minister. She combined her social and professional privilege with her evangelical zeal in an educational crusade that brought books to hundreds of Maritime outposts and formed librarians into a profession. She was a perfect fit for a Baptist University and it was her obvious love of the institution that inspired four books and her play.

3 Acadia is one of a group of allegorical plays written by Canadian women at the beginning of the twentieth century. In a period that was dominated by a philosophy and artistry of realism, why was this genre preferred by some women dramatists? Allegory is associated with religious symbolism as well as having a long history as a political strategy in times of social and state repression. Turn-of-the-twentieth century allegories like those by Edith Lelean Groves, Elspeth Moray, Lucile Vessot Galley, Josephine Hammond, Sister Mary Agnes, and Mary Kinley Ingraham challenge pervasive patriarchal ideologies by animating women’s claims to agency and social power with a Christian spirit.1 At a time when women’s second-class status was the rule rather than the exception, these plays celebrate maternity as the sine qua non of a Christian culture. Acadia, in particular, enacts a Baptist journey of self-knowledge, the symbolic moments of which are linked to a liberal history of Acadia University, giving particular importance to the voice of equality in the debate on women’s acceptance into it. It also feminizes the allegorical struggle for spiritual and political enlightenment at the centre of the Baptist conception of the world by imagining it as one between a mother and daughter. It is in this way an allegory for domestic feminism, in which women’s moral superiority is embodied in the character of Acadia who undergoes the spiritual conversion and Truth who crowns her.

4 The Baptists of Nova Scotia grew out of the English Wesleyan and New England Newlight traditions of the late eighteenth century and profoundly shaped Maritime Protestant religious culture and Maritime historical development (Rawlyk, Champions 32; Levy 7). They were formed in the wake of the social dislocation of the Loyalists who came to Nova Scotia, which at the time included the province of New Brunswick, immediately following the American War of Independence. Early North American Baptists, and their New Light predecessors like Henry Alline and Freeborn Garrettson, provided a displaced population, cut loose from its geographic and cultural moorings, "a special sense of collective identity and a powerful sense of mission" (Rawlyk, Champions 6). Early Baptists were evangelical in practice and followed a revivalist paradigm that advocated Free Will (as opposed to Calvinist Predestination), piety, religious revivals, religious emotionalism, ecstatic conversion, New Birth, and education.

5 According to G.A. Rawlyk, foremost expert in the field of Maritime Baptist history and religion, by the early twentieth century when Ingraham was writing, the Baptist faith had abandoned spontaneous revivals and religious emotionalism and become an altogether more institutionalized and middle-class Protestant denomination: a religion more of the head than the heart ("Introduction" xvi). One of the primary motivating forces in the institutionalization of the Baptist faith was the education movement, at the heart of the Second Great Awakening. It led to the foundation of Horton Academy (est. 1829), forerunner of Acadia College and then University (Longley 15).2 The Baptists, nevertheless, "developed as a denomination by challenging some of the orthodoxies of both church and state," and through most of the nineteenth century had "no collective orthodoxy of their own": a Christian education involved feeling "free to revel in the new intellectual realms that had opened up for them with the establishment of Acadia College" (Moody,"Breadth" 28). The Institutionalization of the faith did not mean abandoning its dissenting roots, but using them to support a broadly based Christian education that "accommodate[d] so many ideas, [and] incorporate[d] such a wide diversity of opinion, that it was probably better prepared than many such colleges to withstand the challenge[s]" of nineteenth-century science, secular thought, and women’s rights (28).

6 From the Alline-Garrettson ministries to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women in the Baptist tradition in Nova Scotia were provided with opportunities to expand their social and professional purviews. Lorraine Coops contends that Baptist women "participated equally [with men] in the religious life of many communities throughout the Maritimes" (113). Historically, women, like men, had their own, personal relationship with Christ and this empowered them to act in several central loci of religious and social life. In the Second Awakening they played a key role in "bringing about various local revivals and also in affecting their emotional and ideological substance" (Rawlyk, Ravished 121). Women could "assert their own intrinsic value, test their spiritual gifts, embellish their preacher’s gospel, and attempt to change their communities’ values." Historically, women took the initiative in exhortation, which was a key factor in bringing about revivals. This, in turn, provided them with the"opportunity to participate fully, creatively, and as equals" (112). Indeed, the community would listen to their voices with the same authority as any man: sometimes "they broke through the hard shell of deference to express deeply felt feelings and to criticize their husbands" (119).

Portrait of Ingraham as a girl, circa 1890. Courtesy of Acadia University Archives.

Display large image of Figure 1

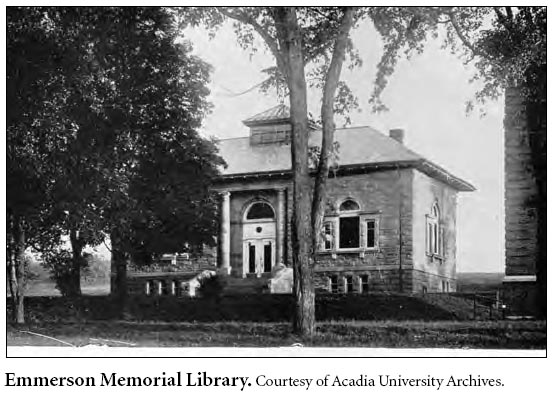

7 Baptist women’s missionary societies were the first Protestant organizations to provide women with opportunities to organize, form associations, hold conferences, speak in public, and travel as single, professional women. The first women’s missionary board in Canada was established in 1870 by Miss Hanna Norris, a graduate, like Ingraham, of the Ladies Seminary in Wolfville: she set up thirty-two missionary "circles" in two months (Ross 92). In "1885, there were 123 Baptist woman’s missionary aid societies in small towns and villages across the Maritimes" (Prentice et al. 171). By the 1890s, according to Miriam Ross, overseas missions sought out women who were educated, single, and professionally trained as teachers, nurses, or physicians (Ross 96). These societies were of great interest to Ingraham, who made their history the subject of her 1947 volume, Seventy-Five Years: Historical Sketch of the United Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union in the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

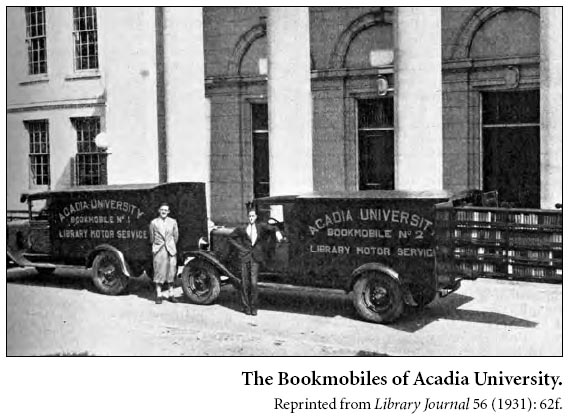

8 Baptist women missionaries understood their job as "bringing Christianity to depraved heathens;" however problematic it appears to us today, to them it was as an entirely righteous activity which expanded their own horizons and those of their sisters at home (96).3 Missionary women drew strength from believing, like some nineteenth-century American evangelical theologists, that the conversion of mothers had special significance: it is "the most efficient means of Christianizing heathen lands; […] no culture could be successfully Christianized" until the message of the Gospel had reached women (96f). Baptist missionaries, including men, understood them as best suited to the task of educating themselves and children: it was the business of "‘Bible women’ […] to read the Scriptures to those of their own sex … and to impart religious instruction to women" (90).

Acadia Ladies Seminary. Reprinted from Longley.

Display large image of Figure 2

9 According to Terrence Murphy, "the conspicuous role women played in the evangelical revival helped to reinforce the notion that women were ‘naturally religious.’ Exemplary piety was part of an idealized conception of womanhood that also included purity, submissiveness, and domesticity" (145). As the nineteenth century moved to a close, the evangelical model of womanhood was solidified by an industrialized economy that increasingly separated the spheres of home and work, elevated the importance and moral status of children, and identified women with the domesticity, maternity, and nurture (145). Women claimed their own, unique status based on ideas of natural maternity and moral superiority. They argued that their"special experience and value would be crucial to society," to families, and the nation if only they were allowed to participate in the public sphere (Prentice et al. 189). This ideology became known as domestic feminism and it infused the social gospel and moral reform movements in which Baptist women participated.

10 Women’s access to education was among the earliest social issues to inspire Baptist women. Although Mount Allison, in Sackville, was the first post-secondary institution to open its doors to them in 1872, women’s education in Nova Scotia was spear-headed by Baptists. In some ways, it was a latter century expression of the educational movement, the first school for "young ladies" having opened in 1858 (Longley 93).4 As in the movement for men’s education, Baptist women were inspired by women’s educational gains in Scotland and the United States; they were influenced by Scottish born Frances Wright, abolitionists in the U.S., and by events in New England (Longley 92; Moody,"Breadth"21).

11 By 1914, when Ingraham was an undergraduate, women were in the throws of great social and professional change brought about by years of political struggle and galvanized by industrialization and World War One. In the general period that spanned the years between Ingraham’s birth and the publication of Acadia a swell of educated women recognized the need for public action and participated in what became known as the Woman Movement. In varying parts of Canada women fought for and won the right to vote in municipal, provincial, and national elections, enter higher education, stand for the bar, act as judges, own and bequeath property, bring law suits, and homestead. Famous women activists like Susan B. Anthony from America and Emile Pankhurst from Britain came to Canada to lecture. But Canada also produced its own crop of influential, outspoken feminists: women like Emily Murphy (1868-1933), Nelly McClung (1873-1951), Francis Marion Beynon (1884-1951), Lillian Beynon Thomas (1874-1961), E. Cora Hind (1861-1942), Mary Ann Shadd (1823-1893), Flora MacDonald Denison (1867-1921), Kathleen ("Kit") Coleman (1864-1915), Emily Stowe (1831-1903), Augusta Stowe-Gullen (1857-1943), and Sarah Ann Curzon (1833-1898). A great many of its eventual proponents (one estimate claims one in eight) became involved in women’s organizations that initiated a wide array of social, economic, and political reforms (Prentice et al. 210). These included the local missionary societies founded by the Baptists and national organizations like The Girl’s Friendly Society, Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Y.M.C.A., The National Council of Women, and The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, all of which promulgated domestic feminist politics. Women in these societies developed Christian reform agendas that focussed public attention on a broad range of social and political issues that arose out of an economy transformed from rural and agrarian to urban and industrial. They also underwent their own large-scale transition from working at home to the paid labour force: the fortunate middle-class joined the professions of teaching, nursing, social work, journalism, law, and medicine.

12 At Acadia, upper-middle class women who lived in residence comprised almost one third of the student population (Moody, "Esther" 39f). Esther Clark, a contemporary of Ingraham’s, also belonged to this group, and describes the liberal feminist culture of New Womanhood in which women students were immersed: they changed their dress and . . . activities to suit the new circumstances [and] enjoyed a freer, more physically-active life style than did [their] mother's generation" (44). Their social and political consciences were raised by debates on women’s suffrage and women’s history (46).

13 Like Ingraham, they had been brought up on the social gospel at home. At Acadia, they listened to lectures discussing true womanhood and women’s social responsibility (Moody, "Esther" 45): the university invested their ideas and their work with an intellectual dimension, "which strengthened their commitment" (46). In residence, they lived with "female missionaries home on furlough" who were brought in "as role models for students" of evangelical womanhood (45). For the women of Acadia, liberal feminism, grounded in equality, was interwoven with the more conservative views of domestic feminism that galvanized the social gospel and based their intervention into the public sphere upon their superior Christian morality.

14 Mary Tryphosa Kinley was born at Cape Wolfe, Prince Edward Island on March 6th, 1874. She was one of six children and the second daughter of Elizabeth Kinley (nee Wilkinson) and the Reverend Robert Bruce Kinley, whose father James Francis had emigrated from England to Canada in the 1820s.5 Her father was ordained a Baptist minister in October of 1881 and began his first pastorate at East Point P.E.I: Mary, her mother, and three siblings were among the first to be baptized by him.6 By the end of the century, education, even for girls, was important in the Baptist tradition. It is not surprising, therefore, that Mary was sent to Charlottetown to the long established Prince of Wales College for her high school education and then to the provincial Normal School. She was studying to become a teacher. In the early 1890’s, Mary and her family moved from the island to Paradise, Nova Scotia, which was a stronghold of Baptist activity at the end of the nineteenth century. There, she accepted her first teaching assignment. She was engaged in the public school system from 1891 to 1896 and again from 1899 to 1905. In the interim, she graduated from Ladies Seminary at Acadia University in Wolfville, the famous Baptist girls’ school on the East Coast. In 1905 she met her future husband, Reverend John A. Ingraham of Margaree, Cape Breton. As was conventional for middle-class women of the time, Mary resigned her teaching post in preparation for her marriage the following year. However, in 1910, after only four short years, John died and her life took a dramatically different course.

Mary Kinley Ingraham, when she received her Bachelor degree in 1915. Courtesy of Acadia University Archives.

Display large image of Figure 3

15 At thirty-five, Ingraham was widowed and without children. She was also smart, educated, and had a substantial teaching career behind her. This career and her rather spontaneous decision to quit Nova Scotia expressed a confidence and an independence of spirit that was fostered by her Baptist faith. She remained abroad for two years, first living in Mansfield, Massachusetts, teaching at Green School (1911), and then at Spelman Seminary, an African American Baptist institution in Atlanta, Georgia (1911-1913). When she returned to Wolfville, it was to embark on a new, creative, and scholarly journey. After a brief appointment to her alma mater, the Ladies Seminary, she enrolled in Acadia University.

16 In 1915 Ingraham received her Bachelor of Arts with honours in Classics and English; in 1916 she was awarded her Masters, with a thesis on the pastoral elegy.Over the next months she professionalized her literary degree.Again she leftWolfville, this time for Boston, where she took Library Science at Simmons All Women’s College. She was back inWolfville a year later in the position of Chief Librarian ofAcadia University (1917); it was a post she held for 27 years.

17 At Acadia Ingraham enjoyed the professional latitude to employ her evangelical zeal in a crusade that changed the educational landscape of the Maritimes and opened a profession to women. Over the course of her career, she oversaw an unprecedented acquisition of 60,000 new volumes in Acadia’s Library collections: the greatest expansion of the library since its founding in 1854. She initiated the profession of Library Science in the Maritimes by organizing its libraries into their first collective, called the Maritime Library Association, for which she was Secretary-Treasurer for most years between 1918 and 1944. In 1936, she accepted the first editorship of its new publication arm, the Bulletin, a position she also occupied until her retirement (Sexty n.p.). She designed and taught the first library course in the region at Acadia; it ran during her entire tenure.According to her assistant Helen Beals, women who graduated from her classes (and they were almost exclusively women) held positions in libraries throughout Canada and the United States.

Emmerson Memorial Library. Courtesy of Acadia University Archives.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

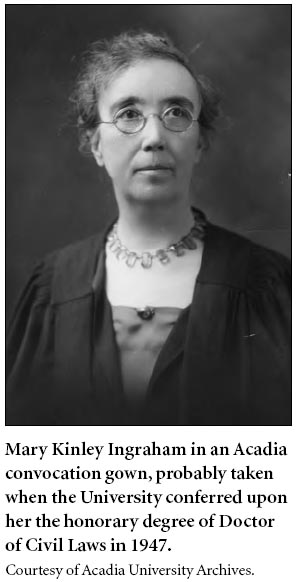

18 Ingraham once said that "a developing civilization needs books as much as it needs railways and automobiles because the instinct for a sound, strong mental culture is in the best of our people, and may presumably lie dormant in the worst" (Sexty n.p.). She spear-headed a traveling library system, the precursor to the contemporary regional library system: Acadia sent two trucks, holding two thousand five hundred books, to one hundred and seventy-six locations in Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island.A letter she sent to newspaper editors on the 30th of June, 1922 asks for assistance in helping the library association to "put libraries […] in every city, town and hamlet in [the region]" (Sexty n.p.). By 1931 her "bookmobiles" served eight hundred and fifty subscribers, substantially more than the university library itself (Longley 131). At the end of her career, Beals states, "[Ingrahm] made an outstanding contribution not only to the University but […] the library profession in all parts of the Maritime Provinces" (486). The importance of her work was recognized most significantly by Acadia University in 1947, when it conferred upon her the honourary degree of Doctor of Civil Laws (Blanchard 153). After her retirement, Ingraham moved to Livermore, Maine, where her brother, Farrar, was pastor of the Baptist Church in Livermore Falls. There "she became the operator of a mail order book room and lending library" (Sexty n.p.). She died in Livermore on the 19th of November, 1949.

Mary Kinley Ingraham in an Acadia convocation gown, probably taken when the University conferred upon her the honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Laws in 1947. Courtesy of Acadia University Archives.

Display large image of Figure 6

19 Mary Ingraham was a member of the Canadian Author’s Association and edited and published works related to her interests in women, the Baptist faith, Library Science, and Acadia. From 1924-1929 she edited Book Parlance, her own cultural magazine. She compiled a Preliminary List of the Published Writings of Women Graduates of Canadian Colleges and Universities (1943). Her four books on Acadia include Isaac Chipman (1925), The Library of Acadia University, its Past and Present (1938), Acadia’s Library, the Heart of the University (1925), and Many Early Printed Books in the Library of Acadia (1940). She published her own book of poetry entitled A Month of Dreams (1932). Acadia (1920) is her only extant drama.

20 Allegory is a form that lends itself to both religious and political sentiments. A Greek term meaning "other-speaking," allegory uses a variety of literary tropes such as synecdoche, metonymy, prosopopoeia, and personification, but according to Angus Fletcher, its most significant feature is hyponoia or a "hidden underlying meaning of a story or myth […]. In the simplest terms, allegory says one thing and means another" (2). Allegory usually has a literal level of meaning that forms a coherent story on its own, but this literal surface also suggests a particular doubleness of intention, something Northrop Frye calls a "contrapuntal technique" (90). While its roots lie in the study of classical myths and rhetoric, allegory is largely associated by scholars of Western drama with the Medieval Morality plays of the fifteenth century and is "closely identified with religious ritual and symbolism" (Rollinson 3; Fletcher 20). One of the "oldest idea[s] about allegory [is that] it is a human reconstitution of divinely inspired messages, a revealed transcendental language which tries to preserve the remoteness of a properly veiled godhead" (Fletcher 21). Allegory has an equally important political tradition.7 "That allegory refers to political discourse," according to Gordon Teskey, "is suggested to the ancients by its rootedness in the vers agoreuo (‘to speak publicly, to harangue’) and ageiro (‘to gather’). Allegory speaks in the agora, the gathering place, but in an ‘other’ way, mysteriously, disclosing a secret to the initiated while keeping away the profane" (123). It has been frequently employed in political subversion and propaganda. Joel Fineman has remarked that"allegory seems regularly to surface in critical or polemical atmospheres, when for political or metaphysical reasons there is something that cannot be said" (qtd. in Kelley 43).

21 Arguably, this is why women playwrights in Canada between 1911 and 1920 wrote allegories: at a time of great social and political change in their lives, it was a way to speak in the "agora or forum," that is, in a public place, to other women (Teskey 123). These allegories allowed women to express their feminist politics to those who were able to hear a story in which the female and feminine were the apotheosis of a Christian society. On the exegetical level the plays celebrate the nation, and praise industry, capital, and a Christian world view. On the literal level, they proceed in similar fashions: an iconographic hero presides over a procession involving an agon between virtue and vice (Fletcher 41); characters—often personified abstractions or representative types— embody various aspects of the body politic. In all of them, a sequence of virtues or vices or figures of topical interest proceed to the stage where they engage in formalized dramatic interplay, interspersed with songs and dances. Many of these plays are engaged in a metaphysical program that links the nation-state and God with women: Canada is dramatized in female terms and women, often in the role of mothers, as its saviour. In a resolutely patriarchal context, all of the plays present feminine worlds, populated largely by women and focused on their issues and politics.

22 Several of these allegories are written to inculcate feminist values into children, particularly those associated with maternal feminism. Edith Lelean Groves’s Canada Calls (1918) is a self-proclaimed "patriotic play." Its main character (and her side-kick the good fairy, Thrift) receives a procession of minions—the soldiers, foresters, miners, farmers, nurses—which represents Canada’s burgeoning economy during the War. Its finale is comprised of a chorus of mothers who invoke the importance of the"thrift and conservation campaign"that became one of women’s most important contributions to Ontario’s war effort; they promise, now and forever, to forsake the bad fairy Waste and fight for God, King, and country at home and abroad (Wilson xciii).

23 The Festival of the Wheat (1918) by Elspeth Moray is also a war-time play for children. In it, Canada is comprised of a young, strong, vigorous nation of farmers under "God’s Almighty hand" (5). Its scenes are set up as a series in a great rhythmic cycle that represent the life of the nation: first comes the blacksmith who shoes the horses that pull the plough; then comes the farmers to sow seeds, the reapers who harvest the grain, and the millers who grind it. The last to be introduced is mother. Because she feeds the country’s children, she links the beginning and the end of the cycle: her domesticity, maternity, and piety are the sine qua non of Canada's existence and the insurance it will continue.

24 Sister Mary Agnes wrote almost all of her more than seventy plays at St. Mary’s Academy, a long-established Catholic girls’ school in Winnipeg. Many were written for occasions, as is the case for her allegories the "Harvest of Years" (1924), performed for the 50th anniversary of St. Mary’s Academy, and Arch of Success (1919), given several times at Commencement ceremonies. Their fidelity to the Academy serves the same function as the nationalism in the plays by Groves and Moray. In the former, the Spirit of St. Mary’s, Queen of the Golden Jubilee, is its central allegorical agent.Assisted by the Spirit of the Past, she oversees a procession of characters that include History, Art, Poesy, Science, Music, Religion, and Vocation. More recitation than drama, the play’s cumulative effect is to represent a culture of education beyond the traditional feminine arts in which female strength and self-reliance is the strongest, underlying message. The Arch of Success allegorizes the life of a Christian"Everygirl"as a battle between Christian good and evil. "1stGirl" presides over a parade of personified attributes that comprise her "character." Industry, Purpose, Courage, Will, Sincerity, Perseverance, and Duty battle their sinful counterparts Idleness, Pleasure, Cowardice, Day-Dreams, and Fun. In the end, each attribute takes its rightful place within the Arch of Success that stretches across the stage and encloses the life of an intelligent, industrious, and moral Catholic girl.

25 Famous Women (1916) by Lucile Vessot Galley and Everywoman’s Road: A Morality of Woman: Creator, Worker, Waster, Joy-Giver, and Keeper of the Flame (1911) by Josephine Hammond are plays written for adult women. The first of these has an all female cast comprised of a possible thirty-seven characters—old and young, rich and poor, real and mythological—from across the globe and throughout history. Included among them are queens and peasants, ladies and maids, military and civil heroes, reformers and radicals. Each presents herself before a female judge to argue why she should be crowned the "true ideal" of womanhood. The winner in this contest, "the bravest and the truest of them all," is, not surprisingly, Mother, for she is the apotheosis of home, the heart, and Christian grace (Galley n.p.).

26 Hammond’s Everywoman’s Road also has a huge number of characters representing women from all corners of the earth.8 Like Ingraham’s Acadia, Everywoman is awakened by Truth and, assisted by her votary, comes to know her "highest" self or selves: the Spirit of Creative life, Nature, the Body and Heart, Society, Mind and Hand, Art and Society. The play expresses a maternal feminism in the embodiment of the "spirit of motherhood," but also announces an ethic of equality, an"equal heritage of goal with [everyman]" (51f).

27 Ingraham’s Acadia forms one of this number of allegorical plays and it is by far the most complex of the group. Although it is Ingraham’s only extant drama, Isabel Horton claims she did write others plays for both the Wolfville Baptist Church and the Baptist Convention. It was never performed, but one cannot help wonder if Ingraham hoped it would be taken up by the University Dramatic Society, established one year earlier in 1919 (Longley 122). Acadia is a Baptist and feminist allegory of the history of Acadia University. Like all allegory, it has two levels of meaning. On the exegetical level, it is a dramatization of the early years of Acadia College, its liberal humanist roots, and the debate on female education. On the literal level, like the plays discussed above, its symbolic action is structured as a progress. Acadia enacts a Baptist journey of self-knowledge, comprised of moments of symbolic "invention," including New Birth, suffering, conversion, war, and salvation (151). Central to a feminist understanding of the play is the fact that it feminizes the allegorical struggle for spiritual and political enlightenment that George Marsden claims is shared by all fundamentalist Christians, by representing it as one between a mother and daughter (qtd. in Rawlyk, Champions 30).

28 Acadia is very short, despite its five acts. Written in irregular rhyme, the play opens with an invocation of its eponymously named main character whose journey we follow. Confused as to who and where she is, Acadia is called into the landscape of pastoral Wolfville where she sees its breathtaking view of the Blomidon cliffs. She is awakened by her votaries Learning, Science, Art, and Theology, as well as Man and Woman, who want her to make them a "home." But, above all, she is bidden by Truth who demands that she"arise and […] gather my people to their ancient fold"(3). Act II imagines time has elapsed, that Acadia is separated from Truth and conflict rages about her, especially in the altercation between Science, Theology, and Learning. As the act closes, Truth returns and brings God back to the university (10). Act III is Acadia’s lesson in women’s rights. She is approached by Woman, who pleads to be allowed"the steep ascent to Learning sweet"(12). Acadia refuses, but Truth overrules her authority and robes Woman in the scholar’s gown. In Act IV she is called upon by War to sacrifice her sons"to battle for the right," for home and for Truth (16). Bereft of them, she languishes, Woman’s head in her lap, her supplicants ringed round in "attitudes of sorrow" (17). Act V celebrates Acadia’s victory in a redemptive peace. Men have been killed, but the war was holy and women have taken up the burden of learning. In the end, all bow at Learning’s knee and Truth crowns Acadia.

29 Acadia’s opening is symbolic of the regeneration that was fundamental to Baptist conversion experience (Moody, "Breadth" 6). It harkens back to the revivalist tradition of the College during the nineteenth century, when Baptist "religious revivals […] swept the campus [and] were [understood as] clear proof of God’s seal of approval" (13). Its awakening recalls a time when the success of the institution"was measured not in the Cicero memorized or the theorems learned but in the souls won for Christ"(13); a time when"what one profoundly experienced in the core of one’s being, not what one learned rationally in the classroom, was the essence of the idea of a ‘Christian education’" at Acadia (14). It is a play of its age. Although religious revivals of the kind described by Rawlyk had abated, during the First World War, when the Baptists abandoned their historical position of neutrality and lent their support to the union government and conscription, "recruitment rallies" at Acadia "took on many of the trappings of a revival meeting" (Moody, "Acadia" 148). The play captures the spirit of this patriotic revivalism.

30 Acadia is the spirit of education. She is called into being by her mother Truth so that she may "gather my people""out of this dark land" (3). She is light and knowledge and her awakening also represents the Baptist intellectual awakening of mid-nineteenth century Nova Scotia, "which swept over the British American Colonies after the war of 1812 [and led to the founding of] schools, libraries, newspapers, magazines, and books" (Longley 15). Acadia is what Fletcher calls a "cosmic image" (70). She is formed of several minions who represent elements of an institution, the ideological roots of which are, broadly speaking, Christian in character and liberal in curriculum (Moody"Breadth"11). Art has a small voice, but insists that "The people will love me / So I may live in thee" (4). "Theology"represents the College’s emphasis on a type of moral and religious instruction that was non-sectarian: despite being a Baptist institution, the founders did not require its professorate to be Baptist. "Science" asserts, "My way is hard, but tis a holy way," alluding to the polarization between science and theology among the faculty. "Man"is everyman and representative of the important liberal precept in Acadia’s early development that education ought to be within the reach of "every male" and the "ordinary intellect" (Moody "Breadth" 11).9 "Woman" is both the attendant of the domestic sphere and a voice of the disenfranchized who aspire to the same right to college acceptance. "Learning" is the leader of the Chorus which, in this context, is the larger university community. The Chorus makes the college cheer, or "yell," as it was called, that opens and closes the play and celebrates the great reconciliation between Science and Theology with "a rollicking college song" (11).

31 The play immortalizes the origins of Acadia University by invoking six of its first seven Presidents, all Baptist ministers, and the men who gave the institution its nineteenth and early twentieth century liberal character. In it, Man says to Acadia: "Think of the men who toil and live for thee, […] / The names of Pryor, Cramp, and Crawley live; / Yea, let them live forever; let all give / Due meed of praise to them; and let thy son / Sawyer, the scholar sweet, / Let him complete / Their work so well begun. / Live, Acadia!"(8).10 No man in the nineteenth century did more for Acadia University than Edmund A. Crawley.

32 Crawley was the founder of the Baptist Education Society that called for the establishment of Horton Academy, and author of its first liberal articulation as a theological seminary, designed to "assist indigent young men who felt called to the Gospel ministry" (Longley 21). He created a curriculum that was non-sectarian, "adapted to the needs of the people" and "open to students regardless of their religious denomination"(21).11 Having been refused a position as professor at Dalhousie for reasons of sectarian prejudice, Crawley approached John Pryor, friend and second principal of Horton Academy, and together they led the political campaign to establish Acadia college "under the same government as the Academy [with] no restrictions of a denominational character […] imposed on professors or students" (31). Crawley and Pryor were also Acadia’s first two professors, the former of Philosophy and Mathematics, the latter of Greek and Latin.

33 Dr. John Mockett Cramp was called the "‘second founder of Acadia’" because when he "assumed office in 1851 the College had one professor, few students, and no Endowment" and upon his retirement there were five professors, an endowment fund of thirty thousand dollars, and forty students in an expanded curriculum that included "the Christian ministry, […] education, law, business and medicine" (Longley 81). Artemus W. Sawyer was the president under whom women’s admission to the College was effected; he oversaw the transition of the College into a University (1891). Thomas Trotter and George Barton Cutten, also mentioned in the play, brought Acadia’s liberal philosophy into the twentieth century. Trotter solidified the institution’s finances, opened up the department of Theology, created a degree of Bachelor of Science, and introduced the first course in Household Science for women (Longley 105; 110). George Barton Cutten continued to elaborate the curriculum, augment the professoriate, and expand its buildings in an unprecedented manner. He also took classes of boys to war (Moody, "Acadia" 143f). The play names these Presidents to conjure up the general "breadth of vision" and "breadth of mind" that characterizes Acadia’s first leaders and enacts how their"remarkably"tolerant views are tested by the challenges of science, the debate over the higher education of females, and the First World War (Moody,"Breadth" 28).

34 The"Penury and Fear"that racks Acadia in Act II refers generally to the years between 1842 and 1869 when the college met crisis after crisis, at one point nearly losing its charter: its sources of income dried up, major endowment funds were lost, and professors were asked to forfeit their salaries, resigned, and were rehired (Longley 64).12 Her suffering, however, is also related to the dissension within the College between Christian views and the scientific discoveries of the age that challenged them, like Darwin’s 1859 publication The Origin of the Species. "Learning doth flout Theology, / And Science looks on both with scornful eye, / While Art, the beautiful, doth sleep,"Acadia tells the Chorus (8). "Faction hath torn" Acadia and "Ignorance hath harmed, / And Pettiness had sway," Truth observes (10). To end the distress, Man pleads to "let Sawyer complete his work," recalling Sawyer’s report to the Baptist Convention in 1874 in which he argued that if we "make religion the foundation of the structure and all branches of human knowledge the materials […] science and religion should not be considered as antagonistic forces, but rather as different methods of reading and understanding the purposes of God" (qtd. in "Moody," Breadth 28). When Truth returns, dissension gives way to contrition. Learning apologizes to Theology—"I crave thy grace, austere Theology / If I have flouted thee." Science reconciles with Theology: "Is it that thou and I, Theology, / Must ever be at variance? Oh, dear / To holy Truth are both, I ween; / The Truth shall be our queen" (9). While Theology still has a slight tone of superiority, it defers, finally, to"ever follow"Science. Science, in its turn, submits to Theology and both agree to be ruled by Truth.

35 The struggle of "Woman" to enter Acadia is given prominence in the play in its own, separate Act. This struggle represents the second obstacle in Acadia’s journey: her recognition of Woman’s equality is a type of conversion experience on her progress toward self-knowledge. It is initiated when Woman pleads to be admitted and Acadia refuses:"For Man I came; / For Woman, save in him / I have no place as yet" (12). The struggle is elaborated by the standard arguments that many critics of higher education leveled against women at the time: it will dull their beauty and cause them to neglect their children and grow irascible with their husbands.13

36 "Content thyself in home, and there abide" rails Acadia (12); and later, "[O]n thy hearth let holy fires burn, / Let little children love upon thy knee, / Else go forever far from me" (14). Acadia fears that if she "stay[s] with Art and Science" her "children well may miss a mother’s care" (12). While Woman receives some support from Learning, who recognizes she has shown strength in "every age" and insists that Man "humbly fall / In penitential prayer for wronging thee!" (13), her struggle for acceptance is also met with resistance by Science, who ironically uses scripture to denounce her pleas and side with Man: "Thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee" (13). Man wants to "shame […] the Woman who will say / Tis not her fairest crown / To love and honour and obey"(13). As was often the case historically, Woman’s struggle for equality is refuted by the discourse of natural submission borrowed from St. Paul. Woman is similarly dismissed by War: he demands to know if she "wilt […] also share my love with Man?" (12).Acadia answers that she has always done so.

37 Women’s admission into Acadia, according to Longley, was a kind of natural evolution: the geographical location, administration, and governance of what began as the Grand Pre Seminary (est.1858) became the Female Department of Horton Academy, which in 1865 came under the control of the Acadia College. After 1872 women’s classes were conducted on Acadia campus and governed by the College Board. "Soon […] a number of women asked permission to attend classes at the College"and the President gave them permission to do so (93). When the time came and the first degree was granted to a woman, it did not cause a political ripple.

38 Moody dates the first debates on female education among the professoriate at Acadia to the late 1840s, after gains for women had been made in New Brunswick and New England. By the 1850s, these discussions had dissipated, even though, "[i]n the minds of many, the education of women became closely allied with […] all other aspirations and designs of the Baptist body" (Moody, "Breadth"21).He cites much print evidence in which the support of women's education is considered "of overwhelming importance," "the birth-right of [a] woman," and which urges the society to "teach [women] everything man needs to know" ("Breadth" 22f); Crawley and Sawyer both favoured it. Prentice et al. refer to the question of women as the "most vociferous and lengthy debate" in education (158); though the fact that they had to wait more than a generation for acceptance, according to Moody, was less a matter of politics than money ("Breadth"21).

39 In the play, the feminist politics of the debate are liberal: Woman argues her equality with Man in the world when she insists,"I only ask that I with [Man] compete"and"God […] alone will rule me" (12). She declares that she "will not be the slave of Man" but his loving helpmate, "For only in an equal love may he rule me" (13). And later, "The little Man of earth / Will never rule me, / Save as the sheltering wing of God his love will be; / And Man hath failed me utterly" (13). As in Sarah Ann Curzon’s Sweet Girl Graduate (1882), at the heart of the liberal feminism of the play is women’s equal right to study and this right is partly defended through an allusion to women’s history that evidences women’s ongoing part in the public world. "I long have shared [war with man]," woman argues. "Judge me those who can. / Did Joan of Arc not follow thee in all? Yea, to the burning" (12). Equality is at the heart of her refusal to accept his demand for submission. She reminds him that he is also subject to the disapprobation of Acadia’s votaries: "Art flouts thee, and e’en Learning turns from thee; / Science doth scorn thee oft; her jealous eye / Loves not thy leaning to Theology." Equality is achieved when Truth commands Acadia to "open now her door" and declares Woman a servant not of Man or his prejudices, but of God. It is a political idealism that has less to do with the 1880s, when women actually entered Acadia, than the years during and immediately after the Great War that produced the play, when "women were left in almost sole possession of […] the campus" (Moody, "Acadia" 153). It evokes the spirit of Ingraham’s undergraduate years when women were galvanized by a sense of mission and responsibility for moral and social reforms that they knew would require education (153). This is indicated at the close of the play, when peace has been gained, and Woman’s equal responsibility is honoured by Acadia, who tells us that in the absence of Man, "loving Woman, humbled now, / Took Learning’s burden with a chastened brow" (18).

40 War, comprising Act IV, is an allegorical rendition of the call to serve in the Great War. It commemorates the new unity of church and state, two institutions that had historically been separated at Acadia; it considers Man’s participation in the War a Christian responsibility; it honours the sacrifice made by the student body at Acadia for God and country. According to Moody, at Acadia, "it was not the call of Mother England but Christian conscience that was loudest" (Moody, "Acadia" 152). Thus, in Act IV, when War tells Acadia to"Call thy sons," Man understands he is engaged in a "battle for the right" (16); Truth proclaims the war godly and one that must continue "till blood-stained Earth be purged of her offence / And in the bosom of our God I rest" (17). Act IV invokes "manly" George Barton Cutten, Acadia’s President who in 1916 went to war. Written in apocalyptic, quasi-biblical verse, it recalls the rhetoric of recruitment rallies cum revival meetings, a rhetoric that was also used by professors and ministers to convince six hundred students and alumni to enlist (Moody, "Acadia" 148, 152; Longley 119).

41 The Canadian Baptist tradition is in many ways different from that of the United States, but it nevertheless participates in the grand allegory that George Marsden claims is at the heart of the Baptist conception of the world. This allegory imagines that"[w]e live in the midst of contests between great and mysterious spiritual forces, which we understand only imperfectly […] frail as we are, we do play a role in this history, on the side of either the powers of light or of the powers of darkness. It is crucially important then, that, by God’s grace, we keep our wits about us and discern the vast difference between the real forces for good and the powers of darkness disguised as angels of light" (qtd. in Rawlyk, Champions 30). In Baptist allegory, among "the real forces for good" is a spiritual guide who inspires a mystical conversion for the hero-believer in which time and space collapse and, through Christ’s love, she is transformed and she transforms her community into something "cosmic and heavenly" (34).

42 The domestic feminism of Acadia is enacted in the woman-centred version of the Baptist allegory articulated by Marsden. It stages a battle for the soul of Acadia and her conversion by Truth. Its focus is the spiritual and political awakening of a daughter and her redemption by a divine mother: like God and Christ they redeem the individual and the society.

43 In the "great spiritual contest" that unfolds in the play, the "powers of darkness," the evil forces against which the characters must fight, are not tangible; they are not properly drawn agents or given a corporeal form in the same way that Science, Theology, and Learning are. The "powers of darkness" are historical moments that hover around the edges and in the interstices of the text. They occur as ages without the light of knowledge and God. They are the time of "fear" and "penury" that occurs between Act I and Act II and the period of "pain" that is inflicted upon Acadia in her separation from Truth during Woman’s struggle. The allegorical powers of good are "a human reconstitution of divinely inspired messages" (Fletcher 21). Truth and Acadia embody the word of God. Acadia is both the agent of God and the subject of divine struggle in this spiritual contest. Like Christ, she strives to do right but is racked with doubt and wayward thoughts. The contest is won, in the end, because she is individually saved and because she revives her community.

44 The divine struggle that is the subject of the literal level of the play takes the form of a Baptist conversion. Drawing on Victor Turner, Rawlyk argues that conversions "openly challenged" the constraints of conventional behavior (Champions 27). They were the site of "all sorts of complex and hitherto internalized and sublimated desires, dreams, hopes, and aspirations" and they entailed aberrant activities "such as women and children exhorting publicly," and became "rituals of status reversal" (Ravished 119). In the divine struggle of the play, Truth, like a preacher-woman, effects Acadia’s conversion into a feminist consciousness.14

45 Baptist adherents frequently renewed and revitalized their faith through conversion. Thus, in the play Acadia is three times reborn (Champions 28). Her first birth takes place extradiagetically. As the play opens she has vague recollections of this birth, distilled in symbols like the "cross and flame," emblem of Christ and the Pentecost. Like Christ, she has died and is reborn: "Death had a venomed sting / The grave had victory, / but life again and once again would call, / ‘Awake, my child, and sing’" (4). "Singing," "the rhythmic dancing of the spheres," and the "holy sacrament of tears," have Baptist associations: they conjure up the musical and emotional tenor of the faith as it relates to conversion. Another conversion occurs in the second act: Truth is absent and Acadia’s world has turned upside down. When Truth reappears and tells Acadia "I was never far from thee!" and it will "dwell in thee forevermore," we are to understand that Acadia is converted a third time (10). Her conversion is consolidated in her recognition that women are the social equals of Man under God and that her place "in all" is at his side (15). At the behest of all her citizens, Truth banishes "Ignorance and Blasphemy" and Acadia receives her blessing: "the blessings of the God of my Fathers […] shall be upon the head of Acadia" (6).

46 Acadia’s conversion is also associated with a "God Personal," just as it was in the time of Alline when "a personal ‘interest in Christ’ created by the New Birth […] was the means whereby threatened relationships would be strengthened" (Rawlyk Champions 14). "All pain is past," we are told, reproducing the "instant satisfaction, solace, and intense relief of a real conversion experience" (27). It is both individual and involves "spontaneous communitas," in which the whole of the society is transformed (27). This element of her conversion ends the play: Truth commands all characters, including War, to kneel before her and encircle Acadia, whom she calls "child of love" (7).

47 Truth orchestrates the conversion of Acadia. She is "a special

instrument […] of the Almighty" and a type of Baptist preacher,

"trigger[ing] religious revivals into existence" (Rawlyk,

Champions 13). She is also responsible for intense spiritual relief.

She transforms doubt into agony and agony into renewal and

regeneration. She is a divine and a prophet and God’s "chosen

messenger." She guides Acadia, blesses her, and predicts her

battles and her righteousness in rejecting Woman (6). Like the

great Baptist orators of the ninteenth-century, Truth is enthusiastic, impassioned, and emotional, and her character uses an

orator’s tropes and poetic language, as in this exhortation to

Acadia in the New Birth of Act II:Come with thy sons and daughters unto me,

Come and cosmic be!

Come in the light of all enscrolled

On the tablets of infinity;

Come and affrayed be!

Come in the thought O thy sin unrolled

To Truth’s pure judging eyes,

Come and weep in my bosom’s fold,

Come and ashaméd lie! (10)15

Truth’s rhythmic, musical repetition of "come" to draw in her

followers makes use of a familiar oratorial technique that, like song,

"helped drill the fundamental Christian beliefs into the inner

consciousness" of Baptists (Rawlyk, Champions 8). She also uses

metaphors of "light" and of the cosmos that one conventionally

associates with God. Truth gathers together her band of disciples

and has them "bow at Learning’s knee," in this way demonstrating

their fidelity to Acadia and the new social order she represents (19).

48 Truth feminizes the spirit of God. This is suggested in the first words she speaks to Acadia, who has knelt before her for her blessing. Drawing on the Psalm of David 110:3, in which God is addressing Christ, she says, "‘In the beauty of holiness, from the womb of the morning, thou hast the dew of thy youth’" (6). Truth anticipates the crowning of Acadia at the end of the play by referring to a Psalm of coronation, in which Christ is instructed by God to "sit […] at my right hand" and receive the sceptre. She also tells Acadia that she is divinely called, clothed in the "beauty of holiness" like Christ himself; she is youthful and the"fruit of morning’s womb," which associates her with the Truth. Truth also suggests that Acadia’s journey revisions the story of Joseph (Genesis 49:26): "‘the blessings of the God of my Fathers’," instead of being "on the head of Joseph […] that was separate from his brethren," will "be upon the head of Acadia, and upon the crown of the head of her who is now separate unto me" (6).

49 War presents Acadia’s final test on her spiritual journey toward God and it is only in peace (although she predicts the Second World War!) that Truth crowns her. It provides a culminating moment in Acadia’s conversion experience, when she realizes that the battle of rhetoric and ideas has become real, practical, and deadly. War tests Acadia’s fidelity to Truth and God and the powers of good by requesting that she sacrifice her sons to the Christian cause. Although she laments her loss deeply, she believes that War is good and his cause is holy: "[H]oly was the word He whispered there to me,—/‘my rod and staff / Will comfort thee’"(18). War, in Acadia’s conversion experience is Baptism by fire—"my soul was scorched with demons breath"—that causes her to realize the strength of mothers and women generally. It is "the valley of the shadow of death!" and her soul has been purified through the sacrifice to God and Country of her sons through it (18). In war, Acadia has experienced her own strength, the strength of Woman, and gained the fidelity of Truth that allows her to ascend to a higher state of being in the celestial world and be crowned.

50 The Chorus is a group of characters who represents the presence of the community in the spiritual contest. On the exegetical level, they are the larger student body; but in interpretation of the story of the gods, they are the devout collective of religious adherents which believe in Truth and Christianity. They have a stake in Acadia’s conversion and are saved by her. They are the congregation of the faithful which sings and supplicates in musical verse. Like the participants of a real, historical revival, the Chorus exhorts, prays, and breaks into song, adding emotional substance to the performance text (Rawlyk, Ravished 117). Sometimes their verse is intensely poetic and invocational like a trance—"Truth whose eyes have seen the viewless, / Truth, who bore Eternity! / How we love thee! / Mother of all things that be!" (6). Sometimes their songs are a balm to the anguished spirit of Acadia, as when they sing to her the eighteenth century hymn "Our God, Our Help in Ages Past" (8). They are the collective voice on the side of right and good, at every turn guiding and supporting Acadia and Woman and the values of Truth, to whom they encourage the characters to reach out.

51 Acadia is a play that honours Baptist history, particularly the history of Acadia University, its acceptance of women, and its contribution to the First World War. It is one of several plays, written after the turn of the century, that signal both the positive change in women’s social and political lives and the recognition that they were still living in a period of entrenched patriarchy.

52 Like all allegory, it is constituted by both religious and political sentiments. Its uses the veil of personification and hyponoia to tell a story that adapted Baptist religious experiences like New Birth, religious revivalism, and conversion to a feminist politics. The play makes liberal feminism one of its most important discussions. By placing a mother and daughter at its centre, it feminizes the spiritual agon at the heart of the Baptist conception of the world and enacts the domestic feminist social consciousness of many Maritime Baptist women.

53 Mary Kinley Ingraham’s political views in Acadia are the culmination of two generations of Protestant women struggling for their social rights. When she was born in 1874, women in Canada had virtually no rights. Between 1880 and 1920, the year Acadia was published, Protestant women reformers, including Baptist women, had changed the consciousness of the culture. The liberal humanist ideal that represented an important philosophy driving equality feminism was perhaps no more clearly realized than in the United Baptist Convention of 1921, which adopted a nineteen-point program that was self-consciously race, class, and gender neutral (Rawlyk, Champions 35). Ingraham’s work, including her pedagogical, professional, and creative endeavours, made her part of that struggle.

Works Cited

Acadia University Associated Alumni. The Acadia Record, 1838-1953. Acadia University: Wolfville, Nova Scotia, 1953.

Agnes, Sister Mary. "A Harvest of Years." N.p. N.d. —. The Arch of Success. Winnipeg: St. Mary’s Academy, 1919.

Beals, H. D. "Mary Kinley Ingraham of Acadia Retires." Ontario Library Review 28 (Nov. 1924): 486. Also published in Library Journal 69 D 1(1944): 1061.

Bell, D.G. "Allowed Irregularities: Women Preachers in the Early 19th Century Maritimes." Acadiensis. 30.2 (2001): 3-39.

Bird, Kym. Redressing the Past: the Politics of Early, English-Canadian Women’s Drama 1880-1920. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2004.

Blanchard, J. Wilmer. Islanders Away. Charlottetown, P.E.I.: J.W. Blanchard, 1992.

Canadian Who’s Who. Vol. 1938-9. "Ingraham, Mrs. Mary Kinley."

Coops, P. Lorraine. "That Small Still Voice: The Allinite Legacy and Maritime Baptist Women." Ed. Daniel C. Goodwin. Revivals, Baptist & George Rawlyk. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Acadia Divinity College, 2000. 113-31.

Deweese, Charles W. "Church Covenants and Church Discipline Among Baptists in the Maritime Provinces." Ed. Barry M. Moody. Repent and Believe: The Baptist Experience in Maritime Canada. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Lancelot P, 1980. 27-45.

Fletcher, Angus. Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode. Ithaca, New York: Cornell UP, 1964.

Ford, Anne Rochon. A Path Not Strewn With Roses: One Hundred Years of Women at the University of Toronto 1884-1984. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1985.

Frye, Northrop. The Anatomy of Criticism. New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1971.

Galley, Lucile Vessot. Famous Women: Character Representation, and Historic Entertainment. Ottawa: Minister of Agriculture, 1916.

Groves, Edith (Lelean). Canada Calls. Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1918.

Haliburton, Edith. "History of the Vaughan: The Way We Were . . .Acadia’s Library Through the Years." June 28, 1996. http://library.acadiau.ca/about/history.html. Last accessed March 14, 2004.

Hammond, Josephine. Everywoman’s Road. A Morality of Woman: Creator–Worker–Waster, Joy-Giver and Keeper of the Flame. n.p.: n.p., 1911.

Highlights of Our Baptist Work in Springfield West, O’Leary and Alma Churches 1852–1981. (1977). The Public Archives and Records Office, Charlottetown, P.E.I., Accession # 3733/3.

Horton, Isabel. Personal interview. 13 January 2005.

Ingraham, Mary Kinley. Acadia. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Davidson Bros., 1920.

—. Acadia’s Library, the Heart of the University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: n.p., 1925.

—. Book Parlance. Vol. 1. no. 1 (1924) Vol. 4. no. 1 (1929). Wolfville, Nova Scotia: n.p.

—. Concerning the Pastoral Elegy. M.A. Thesis, Acadia University, 1916.

—."The Bookmobiles of Acadia University." Library Journal. 56 (1931): 62.

—. Isaac Chipman. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: n.p. 1925.

—. The Library of Acadia University, its Past and Present. n.p.: n.p., 1938.

—. A Month of Dreams. Wolfville, Nova Scotia, n.p.,1932.

—. Many Early Printed Books in the Library of Acadia. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Davidson Bros, 1940.

—. Preliminary List of the Published Writings of Women Graduates of Canadian Colleges and Universities. The Committee: Wolfville, N.S., 1943.

—. "Robert Bruce Kinley and His Family" (1941). The Public Archives and Records Office, Charlottetown, P.E.I., Accession # 3733/3.

—. Seventy-Five Years: Historical Sketch of the United Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union in the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Kentville, Nova Scotia: Kentville Publishing, 1947.

Kelley, Theresa M. Reinventing Allegory. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997.

Kirkconnell, Edward Watson. The Acadia Record 1838-1953. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Acadia University, 1953.

Kinley."Notes." The Public Archives and Records Office, Charlottetown, P.E.I., Accession # 3733/3.

Longley, Ronald Stewart. Acadia University, 1838-1938. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Kentville Publishing, 1939.

Levy, George, Edward. The Baptists of the Maritime Provinces 1753-1946. Saint John, New Brunswick: Barnes-Hopkins, 1946.

Marsden, George. Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. Oxford, New York: Oxford UP, 1982.

Mikolaski, Samuel J. "Identity and Mission." Ed. Jarold K. Zeman. Baptists in Canada: Search for Identity Amidst Diversity. Burlington, Ontario: G.R.Welch, 1980. 1-19.

Moody, Barry, M. "Acadia and the Great War."Ed. Paul Axelrod and John G. Reid. Youth, University and Canadian Society: Essays in the Social History of Higher Education. McGill-Queen’s UP, 1989. 143-60.

—. "Breadth of Vision, Breadth of Mind: The Baptists and Acadia College." Ed. G.A. Rawlyk. Canadian Baptists and Christian Higher Education. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queens UP, 1988. 3-29.

—. "Esther Clark Goes to College." Atlantis. 20.1 (1995): 39-48.

—. "The Maritime Baptists and Higher Education in the Early Nineteenth Century. " Ed. Barry M. Moody. Repent and Believe: The Baptist Experience in Maritime Canada. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Lancelot P, 1980. 88-102.

Moray, Elspeth. The Festival of the Wheat: A Play for the Little Folk. Toronto: McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart, 1918.

Morgan, Henry James. Canadian Men and Women of the Time: a Handbook of Canadian Biography. Toronto: Briggs, 1898.

Murphy, Terrence. "The English-Speaking Colonies to 1854." A Concise History of Christianity in Canada. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1996. 88-102.

Prentice, Alison, Paula Bourne, Gail Cuthbert Brandt, Beth Light, Wendy Mitchinson, and Naomi Black. Canadian Women: A History. Toronto: Thompson Nelson, 2004; Toronto: Harcourt, 1988

Priestley, David T., ed. "Introduction: Strands of One Cord." Memory and Hope: Strands of Canadian Baptist History. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier P, 1996. 108-89.

Rawlyk, G.A., ed. "Introduction." Aspects of the Canadian Evangelical Experience. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1997.xiii-xxv.

—. Champions of the Truth: Fundamentalism, Modernism, and the Maritime Baptists. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1990.

—. "From Newlight to Baptist: Harris Harding and the Second Great Awakening in Nova Scotia."Ed. Barry M. Moody. Repent and Believe: The Baptist Experience in Maritime Canada. Wolfville, Nova Scotia: Lancelot P, 1980. 1-26.

—. Ravished by the Spirit: Religious Revivals, Baptists, and Henry Alline. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1984.

Rollinson, Philip. Classical Theories of Allegory and Christian Culture. Pittsburgh: Duquesne UP, 1981.

Ross, Miriam H. "Shaping a Vision of Mission: Early Influences on the United Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union." Ed. Robert S. Wilson. An Abiding Conviction: Maritime Baptists and their World. St. John: Acadia Divinity College and the Baptist Historical Committee of the United Baptist Convention of the Atlantic Provinces, 1988. 83-107.

Schwab, Arnold T. Canadian Poets: Vital Facts on English-Writing Poets Born from 1730 Through 1910. Halifax, N.S.: Dalhousie University, School of Library and Information Studies, 1989.

Sexty, Suzanne. "Fire, Brimstone, and a Spot of Tea: the Beginnings of APLA." Annual Conference of the Atlantic Provinces Library Association in Charlottetown, P.E.I. June 1, 2001. <http://www.ucs.mun.ca/~ssexty/fire.html>. Last accessed 20 January 2005.

Teskey, Gordon. Allegory and Violence. Ithaca, New York and London: Cornell UP, 1996.

Wilson, Barbara M. Ontario and the First World War: A Collection of Documents. Toronto: University of Toronto P, 1977.

Notes