ARTICLES

The Lesbian Rush:

Making Time in The Magic Hour

Through a close analysis of the temporal shifts in Jess Dobkin’s The Magic Hour, this article considers how a refusal to submit to a gendered expectation to rush, might offer not only a means of illuminating the disciplining logic of normative temporality, but also provide a performative space of healing and resistance. Grounded in theories on queer trauma and queer temporality, Zisman Newman introduces a concept of the “lesbian rush,” to consider how those with less support must multitask and rush to achieve economic stability and perceived success. Part of the work that naming this rush commits to is revealing how conceptualizations of “straight time”—a temporal logic invested in reproductive futurities and naturalized milestones—is both heterosexist and patriarchal; that is to say, straight time is not just straight, but also androcentric.

Considering Dobkin’s experiences in the theatre industry, alongside the production’s focus on “trauma and transformation,” this article discusses how expectations to keep pace may be combated through performance. Grappling with gendered systemic inequities which shape our experiences of time, alongside personal narratives of trauma, this article tells a story of one performance over and over again: The story of an artist; the story of slowing down; the story of the past and future melting into the present; and the story of repetition. Each story refuses to rush the narrative, coming back to the beginning of the production and taking a new perspective on what it means to refuse the lesbian rush.

Au moyen d’une fine analyse des changements de vitesse dans The Magic Hour de Jess Dobkins, Laine Zisman Newman se demande comment un refus de se soumettre aux attentes genrées liées à l’empressement pourrait nous permettre non seulement de mieux comprendre la logique d’une temporalité normative qui impose sa discipline, mais aussi de créer un espace performatif dans lequel une guérison et une résistance peuvent avoir lieu. Zisman Newman présente également l’« empressement lesbien », un concept qu’elle analyse à partir des théories du traumatisme et de la temporalité homosexuels pour voir comment ceux qui ont moins de ressources et de soutien sont contraints à mener plusieurs tâches de front et à se précipiter afin d’atteindre une stabilité économique et donner l’impression d’avoir réussi. Une partie du travail effectué en nommant l’empressement lesbien consiste à montrer que les moyens de conceptualiser le « temps hétéro »—cette logique temporelle investie dans les avenirs reproductifs et les jalons naturalisés—sont à la fois hétérosexistes et patriarcaux. Autrement dit, le temps hétéro n’est pas qu’hétéro, il est aussi androcentrique.

En tenant compte des expériences vécues par Dobkin dans l’industrie théâtrale et de l’importance accordée par la production au « traumatisme et [à] la transformation », cet article examine comment la performance peut nous aider à lutter contre nos attentes quant à l’obligation de suivre le rythme. Luttant contre les inégalités systémiques qui façonnent nos expériences du temps et présentant des récits personnels de traumatismes, Zisman Newman raconte l’histoire d’une performance qui se répète sans cesse. C’est l’histoire d’une artiste; l’histoire d’un ralentissement; l’histoire du passé et de l’avenir qui se fondent dans le présent; et l’histoire d’une répétition, d’un refrain auquel on revient inlassablement : « Bienvenue. Merci à tous d’être venus. Je suis tellement contente que vous soyez tous là. » Chaque histoire refuse de précipiter le récit et fait marche arrière pour revenir au début de la production et prendre du recul sur ce que signifie le refus de l’empressement lesbien.

1 In the final moment of Jess Dobkin’s 2017 solo performance, The Magic Hour, we hear at growing volumes, the upbeat sounds of pop music playing in the lobby. We have spent just over an hour in the theatre space watching Dobkin, a performance artist and theatre creator, unravel a story of her childhood. Through episodic movements, she has tried and then tried again and again to tell us a story. We never seem to know exactly what it is she is trying to say. The narrative is jumbled. But, the spectacle is magic. The Magic Hour, developed and produced at The Theatre Centre in Toronto, Ontario, is comprised of monologues, dance, and “tricks,” not quite the convincing illusions we might expect from a magic show, but nonetheless enthralling. Dobkin takes her time to try to tell us something; to remove us from the speedy pace of the everyday; to impart upon us trauma and tragedy, humor, and joy, and a sometimes-familiar confusion of temporal disorientation. The music in the lobby grows louder. We hear Captain & Tennille’s well-known lyrics from 1975: “Love, love will keep us together…” Dobkin moves, from her place inside a circle of chairs where we, her audience, sit, and walks towards the theatre doors, motioning for us to leave the theatre. We collect our things and get up to leave. The lobby has transformed during the course of the production. The walls are adorned with retro decorations, and there are tables with snacks and a bowl of punch. A record player sits on a shelf, with milk crates of curated vinyls. While the music continues to play, two young girls, dressed in clothing from the 1970s, dance beneath a giant revolving vulva disco ball. This is what Dobkin describes as “our final trick” (Dobkin, Interview). It is a soft ending, a choose-your-own-adventure, where you might eat, you might dance, or you might choose to leave the lobby and exit the performance, perhaps unsure if it has truly finished.

2 I begin with an end because time in The Magic Hour is not quite linear. Dobkin moves between past, present, and future, embodying a gendered queer temporality and implicitly refusing what I refer to throughout this article as a “lesbian rush,” or the distinct ways in which women might encounter queer temporality. This is a rush which comes as a consequence of the lack of time and ongoing space available to queer and lesbian women—both in performance and more broadly in social and political life—and the increased amount of labour necessary to tackle this dearth. I use the term rush rather than urgency because of what the double meaning affords: We experience the rush of politics, the rush of killing joy, and the rush to “U-Haul” and share a bedroom with our lovers, but the precarity of our activism and our lives, and the lack of support and resources we have access to as women, often cause us to be in a rush. Without the necessary artistic resources and secure spaces to work productively through our projects, queer and lesbian women artists must rush to do our creative work. The politics of naturalization normalize rushing as if we should anticipate it, accept it, and expect it.

3 To experience this double sensation of the rush in our lives is to feel empowered, if only for a moment within the hurry of the everyday. We receive accolades for succeeding despite what we are up against: “I don’t know how you do it!” “You are super woman!” “How do you get it all done?” Such responses work to reward women for existing within a system of inequitable practices. It does not dismantle these structures, but instead justifies them by praising those privileged (primarily straight white) women who are most capable of existing and thriving within an oppressive environment. In this article, I analyze the temporal shifts in Jess Dobkin’s The Magic Hour, to consider how a refusal to submit to a normalized temporal rush might offer a space of healing and resistance, particularly in relation to lesbian and queer women’s experiences of trauma. Here I ask, how trauma further complicates queer and lesbian women’s relationship to time and how we recall and articulate the past. How might performance not only provide a means to resist the need to rush through a traumatic past, but also to demand the time to name it, begin to confront it, and share it?

4 Following Ann Cvetkovich, I employ both the terms lesbian and queer throughout this article. While the theories I employ are “queer,” that term alone erases the identities and experiences of women (Cvetkovich 10). Thus, alongside the term queer—to denote instability and disruption of naturalized ideologies—I use the term lesbian, to identify the distinct ways in which women who sleep with women might experience time and space. I further employ both terms “[…] to resist any presumption that they are mutually exclusive—that the queer, for instance, is the undoing of the identity politics signified by the category lesbian, or that lesbian culture is hostile to queer formations” (Cvetkovich 11). For queer and lesbian women, both (or neither) labels might describe and reflect how we experience the world. And here, I should note too that the “we” of this article, is an attempt to centralize queer women and lesbian audiences and readers. While I do not assume a monolithic or universal experience amongst us, following Sara Ahmed’s call in Living a Feminist Life, I use “we,” as a “hopeful signifier of a feminist collectivity” (2). This is a we that unapologetically centralizes feminists, lesbians, and queer women, who are defined by the differences within that collective; and a we which also recognizes privilege that animates the way the collective moves and who is most visible within it.

5 I ground my discussion of the “lesbian rush” in queer and feminist theorizations of temporality,2 which demonstrate how the expectations of queer and lesbian women’s time ultimately result in a different way of experiencing time from dominant (read: straight white male) Western conceptions of temporality. Who is awarded time and seen as worthy of taking their time directly correlates to who and what is valued within a patriarchal capitalist paradigm. Those with fewer resources and less support are forced to multitask and rush to achieve economic stability and perceived success. Elizabeth Freeman notes that temporality is itself a disciplining structure (we may think immediately of a child’s experience of a “time-out”), which functions as:

Inequitable power distribution, resources, and access may seem not simply ordinary, but also inevitable through the repetition of routines and temporal rhythms. As Freeman further explains, “we achieve comfort, power, even physical legibility to the extent that we internalize the given cultural tempos and time lines” (160-61). Thus, there is a vested interest to keep up and keep pace. With that said, I also stress how keeping pace is made easier for some than others. Rushing might be a gendered reaction to oppressive patriarchal expectations, but rushing too requires privilege. It is therefore essential to emphasize how settler colonialism, whiteness, and normalized abilities, among other locations of privilege, inescapably impact our distinct orientations within time and space.

6 Part of the work that naming the lesbian rush commits to is revealing how conceptualizations of “straight time”—a temporal logic invested in reproductive futurities, which ascribes particular milestones to our lives (Muñoz 25)—is both heterosexist and patriarchal; that is to say, straight time is not just straight, but also androcentric. Therefore, I work to name the queer feeling of being unstable within culturally ascribed heteronormative temporal structures,3 alongside gendered expectations to complete both paid labour and domestic and caring responsibilities.4 Femininized work, Sara Ahmed notes, such as domestic and caring responsibilities, often result in “the lack of time for oneself or for contemplation” (Queer Phenomenology 31). If leisure is fragmented or interrupted for women, and they are forced to multi-task to complete their unpaid and paid labour, their experience of time in everyday life can feel more rushed, particularly in regards to quality of time spent, rather than quantity (Bittman and Wajcman 172). Just as women’s temporal experiences may be disadvantaged by patriarchal ideals embedded within normalized social clocks, so too queer temporalities cannot remain in steady synch with normative heterosexual temporality. As José Esteban Muñoz argues “within straight time the queer can only fail” (173). Queer temporalities can productively reveal the ways in which temporal expectations are based on normative understandings of power and productivity, and simultaneously challenge the false notion of a universal desire to follow social scripts. However, it is problematic to view queer time as a monolithic or singular temporal orientation. In accounting for queer and lesbian women’s experience of time, I am less interested in essentializing a singular gendered temporal rhythm, and more compelled to open space for a multitude of experiences that are affected and shaped through intersecting social locations and experiences. I therefore note that lesbian and queer women’s experience of time differ based on their distinct experiences and social locations, and ask here how these temporal orientations might be combated or defied through performance.

7 In her refusal to simplify the temporal logic of The Magic Hour, Dobkin both critiques straight time and also implicitly challenges the universalization and limitations of linear conceptions of time, pointing to the ways the past creeps constantly into the present. Like Jaclyn Pryor’s conception of “time slips” in queer performance, time in The Magic Hour is “given permission to do those deviant things it is not supposed to—move backward, lunge foreword, loop, jump, stack, stop, pause, linger, elongate, pulsate, slip” (332). Through such moments, as Pryor writes “normative conceptions of time fail, or fall away, and the spectator or artists experiences an alternative or queer temporality” (332). Queers might fail within the linear logic of straight time, yet such failure, as Muñoz explains “can be productively occupied by the queer artist for the purpose of delineating the bias that underlies straight time’s measure” (174). Where the title of The Magic Hour makes clear that temporality is essential to the production, the length of the performance, which runs approximately eighty-five minutes, quite literally demonstrates how normative time fails. The production makes, even expands, time. Directed by Stephen Lawson, The Magic Hour extends beyond the boundaries of time that are originally set in the production’s title. If rushing is a normalized gendered practice, then this is one form of rebellion: intentionally expanding the duration of time beyond the limited amount allocated to women’s work in the theatre industry. Throughout the production, it is not simply sexual orientation or gender that inform Dobkin’s articulation of time, but also how these positionalities are shaped by and intersect with experiences of trauma.

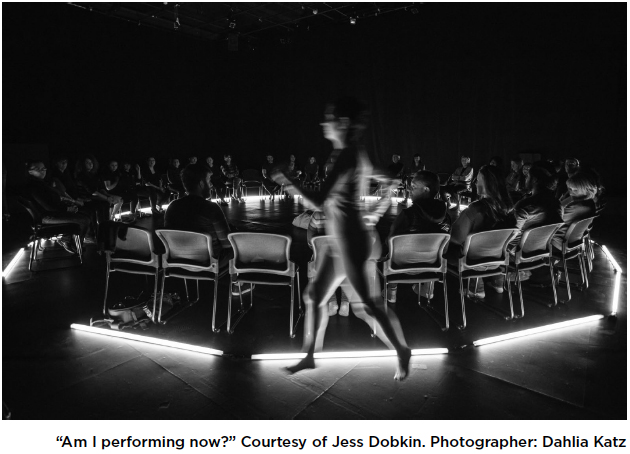

8 The production’s auto-biographical focus on “trauma and transformation” (“The Magic Hour”) inform and complicate the temporal rhythm of the performance. Here, the refusal to rush through the disorientation of the everyday becomes a recitation of traumatic histories, as well as a means of healing and transformation. In her discussion of lesbian sites of trauma in her introduction to An Archive of Feelings, Ann Cvetkovich5 conveys her process of narrativizing a history of incest and trauma: “the story itself couldn’t be articulated in a single coherent narrative—it was much more complicated than the events of what happened, connected to other histories that were not my own” (2). She notes that “these lesbian sites [of trauma] give rise to different ways of thinking about trauma and in particular to a sense of trauma as connected to the textures of everyday experience” (3-4). Similarly, in The Magic Hour repeated (arguably failed) attempts to tell a story refuse linearity and completion. We never quite grasp exactly what it is Dobkin is trying to share. It is not that one story or representation will ultimately be the “correct” articulation of isolated traumatic events, all the multiple sequences are necessary to understand how these events shape our daily orientation in the world and impact our present moment in the theatre.

9 In this article, I follow Dobkin’s lead. I tell a story about refusing to rush as queer and lesbian women trying to grapple with our place in and our experiences of time. I tell the story of one performance over and over again: The story of an artist; the story of slowing down; the story of the past and future melting into the present; and the story of repetition, a refrain we keep coming back to: “Welcome. Thank you all for coming. I’m so glad you are all here.” Each story I tell refuses to rush the narrative, pushing against a desire to too neatly recall a performance that unravels time. In each section, I take a new perspective on what it means to refuse the lesbian rush.

“I’ve never had that before”: This is a Story About an Artist

10 Since the 1990s Dobkin’s performances and public interventions have had a significant impact on the landscape of queer and lesbian performance in Canada and the United States.6 However, before securing the three-year residency to develop and produce The Magic Hour at the Theatre Centre, no major theatre had ever programmed a full-length production of Dobkin’s work as part of an annual season. As Moynan King outlines in “The Foster Children of Buddies,” Dobkin came closest to securing a mainstage slot in a major theatre’s season, as she prepared to stage her first full length production, a one-person show entitled Everything I’ve Got, at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in 2010. However, the performance was switched to a festival slot at the Rhubarb! Festival at the last minute (King 200). While festival productions and one-off events provide opportunities for performance, they also limit the longevity of the development process and offer fewer resources for production, as well as less publicity, and less likelihood to be included in theatre archives.

11 The limited time and space allocated to Dobkin’s performance reflects broader systemic inequities in the industry. Recent statistics on equity in theatre noted that women are underrepresented in leadership roles (MacArthur 5); account for only 26% of playwrights on professional stages (Playwrights Guild); earn 31% less than their male counter parts in the industry (Hill 5); and, despite making up over half of the arts industry, receive fewer awards, comprising only 39% of recipients from 1992-2015 (Beer). I use these statistics to note the quantifiable, but I am also wary of what is not quantified. I have found no national statistics that account for the additional marginalization that women of colour or transgender women experience in the industry, nor any statistics on queer theatre practitioners or non-binary artists. Though quantitative studies might demonstrate precarious access to funds, resources, and visibility, we see from these studies and statistics not only a body count, but also whose bodies count.

12 As I contemplate this concept of a lesbian rush and the possibilities for performative resistance, I note too the privilege that permits certain bodies to resist oppression more easily than others. My own need to rush as a white queer Ashkenazi woman, though present, has fewer consequences than that of other lesbian and queer women, whether Black, PoC, Indigenous, transgender, disabled, or people who inhabit multiple social locations of marginalization. Likewise, as a white theatre performer, Dobkin’s experiences are undeniably influenced by the privileged social locations she inhabits. I name this privilege not to minimalize experiences, nor to detract from the analysis of the production that follows, but rather to note that the power to subvert temporal expectations is easier for some to manipulate than others. So, while it may be clear that time for all women is precarious, simultaneously and inescapably whiteness enables the mobility and transience necessary to move through space relatively unsurveilled.

“Am I performing now?”: This is a Story About Slowing Down

13 The Magic Hour begins in the lobby of the Theatre Centre. Dobkin walks towards a microphone already set up in the centre of the room, and welcomes her guests. After a brief introduction, followed by her first “magic trick,” she invites the audience to follow her inside the theatre, where a circle of forty chairs has been placed for the audience to sit. Once every person is seated, Dobkin glances around the room and walks to the theatre doors, closing them, thus in effect closing the circle. She retrieves a long bamboo stick with chalk fastened tenuously to the end and stands, not moving, at the edge of the circle. Anticipation builds through Dobkin’s stillness; this moment feels extended. Dobkin stares into the circle and slowly begins to walk to its centre. Once inside the circle of chairs, dragging the chalk against the ground, she draws a spiral on the black floor of the theatre.

14 The line begins as a singular thread, and then becomes disjointed, as she dots the ground with short individual segments. Dobkin explains this is “a bit of my map for the performance […] a mapping of what is going to come, setting the space” (Dobkin, Interview). Her slow and deliberate steps moving into the centre of the spiral is both enthralling and unnerving. The motion is much slower and more carefully enacted than the casual welcome outside in the lobby. The unanticipated change in pace and style of the performance makes us more aware of the quality of time passing. It is not simply that she takes her time, but also that she shapes and changes our perception of time. If performance must “take place,” so too it must take time. The careful and slow mapping of space maps time as something that we can take and demand. Dobkin notes that the spiral points to a cyclical temporality: “We are working with this idea of time as spiral or circle: that there isn’t necessarily a distinct starting place or ending space” (Dobkin, Interview). Combating the expectation to rush through explicitly slow movements maps not only the spatiality of imagined place on stage, but also its durationality. Unashamedly taking her time to set up the space, Dobkin directly combats a rush—drawing attention to its force and an internalized need to speed up, by taking her time to enclose and encircle the audience. Yet, this pause and pace is brief.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

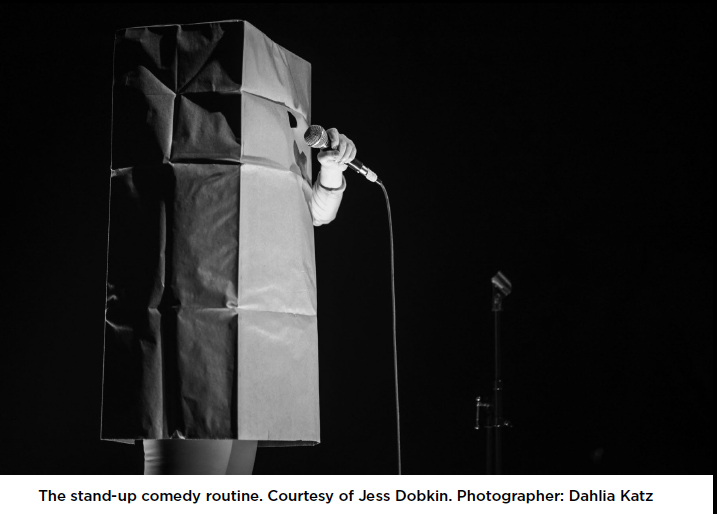

15 Following this opening sequence of the performance, Dobkin begins to run outside the circle of audience members, gradually increasing speed as she moves around the space—literally running laps around the audience. As Dobkin runs she opens up a line of questioning: “Am I performing now?…Now am I performing?…Now am I a performance artist?…Are we there yet?” Then, as her hands rise mid-stride, KC and the Sunshine Band’s sensational 1975 disco pop hit “Get Down Tonight” begins to pulse through the space and fog machines placed at either end of the theatre shoot smoke into the centre of the circle. As she runs, she continues to bellow the same questions over the loud music, with what sounds like increasing exhaustion from the sprint. “Now am I performing? Am I a performance artist now? Are we there yet?” The labour of running, the speed of the movement, and the forceful push towards exhaustion are seemingly necessary actions that characterize and qualify Dobkin to be a “performance artist.” The slow pace of the previous sequence, with Dobkin mapping the space, directly juxtaposes the running, loud music, and exertion of energy in this movement.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

16 Sara Ahmed argues that privilege is an “energy-saving device” that allows certain bodies to pass through space with less effort. Those who are not born into or do not acquire privilege, via settler-colonialism, race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, or class, must work harder to assert their right to space, to belonging, and indeed to mere existence. Ahmed utilizes the analogy of a lock. She writes:

Privilege allows us to take our time because of the ease and confidence with which we pass through space. We do not worry about running low on energy; we take the hours, days, and weeks needed to complete the task. We take up space. We take up time. For queer women, and more specifically those who experience additional marginalization such as trans and cisgender queer women of colour, time is precarious because energy is depleted when fewer resources are available to complete tasks. In this sequence, Dobkin’s pace travelling around the performance space points to an internalized expectation to move quicker, to run, and inevitably to push towards exhaustion.

17 As the music ends, Dobkin continues to lap the circle in silence. She runs until she reaches the southernmost point of the circle and kneels on the ground. In a race to get to where we are going, only to start the next task, we stand until we fall. The loud music, the fog, and the pace of her run require us, the audience members, to turn in our seats to follow Dobkin’s accelerating movements. It is a sensational rush insofar as it engages each of our senses: the lights, the sounds, the smell from the fog, which literally envelopes us. Yet, as Dobkin continues to circle us, the rush (and here, the double meaning of the word manifests again) starts to feel overwhelming. When she finally kneels, out of breath in the circle, we share the exhaustion. We, like Dobkin, are grateful for the silence and finally to get one uninterrupted slow and deep breath. We can sense in this moment, without words, what Dobkin is “up against” through her depletion.

“You can play my mother”: This is the Story About the Coalescence of Time

18 We find ourselves again and again slipping through time throughout the production, uncertain if this moment exists in the present, some distant memory, or an imagined future. Prior to beginning a “reenactment,” Dobkin starts to situate her spectators within a narrative. Rather than asking them to suspend their disbelief and imagine her past, she asks instead for active participation in staging a memory. As Dobkin begins to put on a purple gymnastics leotard she says:

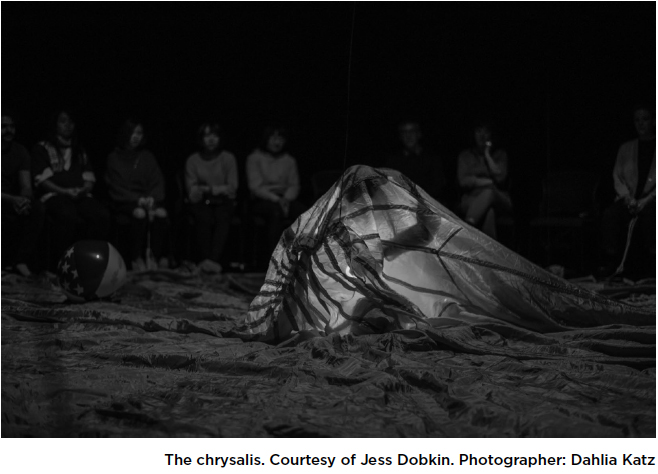

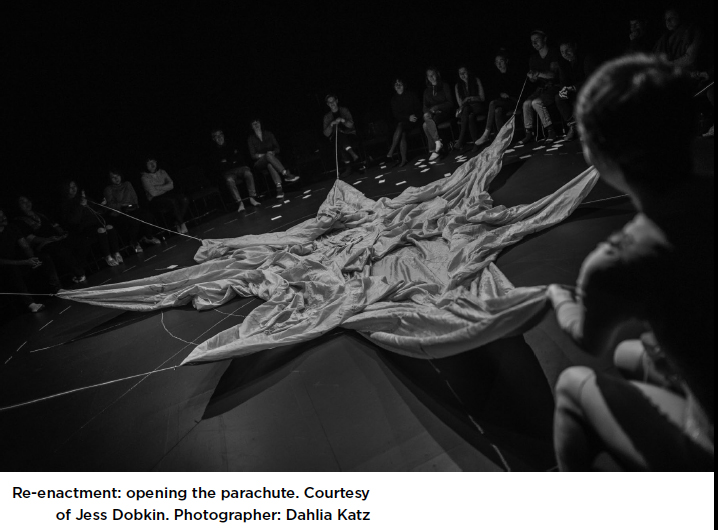

She then begins to hand out small toys from the 1970s, (a troll, a Sesame Street character, a Ronald McDonald doll…) to seven audience members around the circle. Each toy is attached to a string, tied to a prone parachute, folded in the centre of the circle. With each toy she distributes, Dobkin casts the audience member in the reenactment:

Dobkin keeps the final string, with a Kermit the Frog puppet attached to it, for herself; she is playing herself. The strings create a physical link between past and present, and through the material ephemera and Dobkin’s memory, the past is brought into the performance space.

19 For Tavia Nyong’o, queer performers may be drawn to reenactments because of the potentialities that exist within the medium (44), which allow us to confront a “now,” no longer here, through a tenacious return to a “presencing of the past” (Nyong’o 46). In this sequence, Dobkin’s past is almost but not quite reenacted, through the casting of familial characters and the distribution of symbolic representations. But, we don’t get to see the story we are actively participating in telling. The reenactment at once announces and evades the narrative we are here to consume. Yet, the role each audience member plays while holding their string is active, and connects the audience to Dobkin’s ephemeral past.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

20 After distributing each of the seven items, Dobkin instructs the audience members to pull “hand over hand” at the string the toy is attached to. Thick folds of pink fabric slowly open, as they pull the parachute strings, blanketing the floor in the inner circle of chairs. The seven audience members still hold the attached toys, left holding an unknown and unnamed memory in their hands. Citing Linda Alcoff, Laura Gray, and Vicki Bell, Ann Cvetkovich notes a distinction between confession and witnessing, stating that the latter “requires a kind of participation on the part of the listener that is not merely voyeuristic” (94). Here, the narrative is not told at the expense of the storyteller, but rather the audience is asked to participate in a story in which Dobkin refuses simplistic disclosure, focusing instead on the performative power of gesture and performance to reconstruct memory on her own terms.

21 Unlike a linear notion of time, which positions a static past as disconnected from the present, queer temporality actively disrupts the compartmentalizing of past, present, and future. Elizabeth Freeman explains that queer temporality’s interruptions resist “seamless, unified, and forward moving” time and instead “propose other possibilities for living in relation to indeterminately past, present and future others: that is, of living historically” (Time Binds xxii). Dobkin’s radical temporal reorganization—almost reenacting a past, but refusing to ultimately perform it in the present—facilitates a reading of these memories as inextricable from an imagined future and persistent past, and at the same time refuses to oversimplify its reach and impact through linear performance. This blending of past, present, and future contributes to a tradition of feminist artists’ articulation of experience “using dialectical images to bring past and present into collision […] [that] turn performance time into a nowtime of insight and transformation” (Diamond 149). Such a temporal organization can be perceived as a response to a naturalized rush—a refusal to move too quickly through what has been and what could be. When there is less “down” or leisure time afforded to us, we are forced to deemphasize the past and the future. If there are always tasks yet to be completed, the foreseeable future is not only seemingly unattainable, but also perpetually further out of reach. Yet, as queer subjects, we also remain unsteady within the temporal expectations of the present. For queers—and even more so for queer women and marginalized queer peoples—as Muñoz so eloquently articulates:

With this in mind, The Magic Hour destabilizes an expectation to live within a singular moment, asserting instead an inability to isolate one moment from the last/next, an extension of time beyond the present moment.

22 From her place at the centre of the parachute, Dobkin announces that she will perform her next trick: the “show-stopping cutting-the-lady-in-half-trick.” Her arms rise and the parachute is lifted, over her head. The title of the trick brings violence to the representation of the past, both captivating in its beauty and violent in its representation of severing a woman’s body. The past is not articulated in words and the movement from childhood toys to the violence of “cutting the lady in half” is not explicitly described. Simplicity is refused in the representation. During the production, several audience members were visibly confused, unsure if they were meant to release the toys they clutched, as the parachute was lifted above them. Without instruction on how to perform, the audience-reenactors too were tethered to Dobkin’s past. The uncertainty of how to hold tight to the past—or when to let it go— becomes a shared, embodied question.

23 From beneath the canopy of the parachute’s suspended fabric hanging over the audience’s heads, Dobkin shares a new kind of fairytale:

Dobkin’s story constructs and predicts a collective temporality of shared and divergent futurities that exists not “just in a ‘space of time,’ but in colliding temporalities” (Diamond 150). Just as Muñoz instructs, the field of utopian possibility is one in which we must insist on the potentiality of the “not-quite-conscious […] if we are ever to look beyond the pragmatic sphere of the here and now, the hollow nature of the present” (21). At first, Dobkin’s narrative seems to rely on normative reproductive futurities. However, the repetition of “the child that might have a child,” a utopian performative which complicates and exceeds a reproductive imperative, removes the necessary generational succession from the anticipated lineage. Though the child could have a child, or might have a child, the final child who can see into the future is ultimately not contingent on her predecessors’ reproduction—we reach the child who sees the future, predicted on the might have,not the requirement to have. The child that comes, is thus not dependent on the child that was (though they might have been). This queer genealogy, which moves through the past to envisioned futurities, is not ultimately contingent on man and woman fucking. It is contingent on time passing towards a utopian future. Thus, refusing to rush, taking time to conceptualize a future not yet here becomes a way to question normative cycles of reproduction and kinship. Through the ghosts of her own past, Dobkin encourages us to hold the future as a question. Embracing excess in possibility, the tentative and ambiguous child who might have a child queers heteronormative generational structures. Within the lineage of children who “fuck to make children” we may read the presence of the child from the 1976 reenactment—the incarnation of Dobkin’s own memory of traumatic pasts. That child, whose story is told from the distance of a scrambled unformed narrative; who might seem like the unsolved illusive secret in each magic trick Dobkin performs; that child might be the child who might have a child, who brings us to the future. Rather than rushing towards the future or recreating a linear past, Dobkin slows time through its unbinding, enabling her audience access to temporal shifts from within the confines of their embodied experience in this moment and in this space.

“Welcome, I am so happy you came. Thank you for being here”: This is a Story About a Story That Keeps Repeating a Story

24 In the opening sequence of The Magic Hour, before being welcomed into the theatre where the majority of the performance is staged, Dobkin welcomes us in the lobby. She approaches a microphone stand in the centre of the space and speaks directly to the audience. “Welcome. Thank you all for coming. I am so glad you are here […] This is the performance art presentation of theatrical convention to break the artifice and spoil all the fun.” She steps up to a platform beside the microphone, forcing it awkwardly to rotate as she swivels her knees with evident effort. A flash of fire bursts from her hands, before she steps down and walks towards the theatre doors and holds them open for us. We enter the theatre.

25 Similar greetings, “Welcome. Thank you all for coming. I am so glad you are here,” happen repeatedly throughout the production, each with a different style and timbre. It is not that the show is comprised of false-starts, but rather, that time is cyclical in the production. Each new welcome and salutation is the introduction of a new affective embodiment of memory: a development rather than a correction. Dobkin returns and repeats her introduction, slipping out of the rhythm of normalized temporality and slowing the progression of time, refusing the conditioned compulsion to rush through. Like Pryor’s “time slips,” which demonstrate how repetition in performance queers linear temporal expectation, the repeated welcomes in The Magic Hour expose the myth of an objective or easily expressible past.

26 In the second “welcome” sequence, which takes place shortly after Dobkin’s ecstatic and exhausting run around the circle, Dobkin stands on a stage, completely concealed underneath an oversized brown paper bag. From inside the bag she cuts holes for her arms and mouth, and then reaches out to feel for the microphone, unable to see its place from beneath the bag. She finds it in front of her and welcomes the audience again. Hello, thank you all for coming. I am so glad you are here. She performs an intentionally awkward stand-up comedy routine: “What kind of cake makes you cough? A Coffee cake. Why did the chewing gum cross the road? Because it was stuck to the chicken’s foot.” There is a marked shift in presentation style and in expression. The comedy, at first poorly delivered knock knock jokes and riddles, shifts quickly to humour that is not simply dark, but painfully violent:

Silence. Dobkin takes a moment then: “Umm. Ok…Why did the? Umm…How did the… umm” each beginning of a joke stops short. “Umm…Knock, knock.” Slowly, Dobkin releases the microphone from her hand and lets the cord slip slowly through her fingers. So we wait, watching it descend and anticipating the reverberations, before the microphone hits the floor. This comedy sequence, again, beginning with a similar “welcome” greeting and direct address to the audience, begins to tell a more explicit narrative, welcoming us to a seemingly new, if not familiar story. Much of Dobkin’s previous work has started to tell a similar history of trauma. Started to, but never quite finished.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

27 Cathy Caruth notes that the traumatized become “the symptom of a history that they cannot entirely possess” (5). In these repeated welcomes, Dobkin tries tirelessly (literally running to exhaustion) to possess that which she cannot return to. Childhood trauma and memory is not recollected in an explicit narrative. However, we are collectively a part of the discovery through a bending of time and cyclical repetition. It, like the repeated opening sequences weaves through history and memory, constructing them through affective movements; we come to experience how memory might feel, but not what the memories are of. We may think of the repeated starts in the production as attempts to articulate trauma and memory through different performance styles and narrative approaches. The inability to use one linear narrative form to capture the past as a singular cohesive story and the repeated sequences staged to articulate this past demonstrate a pursuit to convey the complexities of that which has been and that which is not yet here. It complicates an understanding of history and trauma as a singular event. Dobkin explains:

Multiple starting points enable threads of history to be considered simultaneously, to slowly and assuredly take up time. The show keeps restarting, but never erasing the previous moments. In this way, while The Magic Hour extends beyond the promised hour of the show’s title, it also never reaches its full duration, as each sequence that restarts is less than an hour in length. The complexity of this temporal representation points to an explicit refusal to rush and simultaneously the persistence of the everyday experience of trauma, extending past the traumatic event itself. We experience an hour of magic, which perhaps is so magical in part because of its ability to extend the hour and to take up space for just a little bit longer.

“Exit through the dance party”: This is a Story Refusing to End

28 Dobkin’s work is testimony that refuses to straighten a crooked and cyclical timeline of trauma. We see through repetition and temporal swerves an explicit rejection of the isolation of past from present, a queering of straight time, in favour of a kind of lesbian pause. How might this pause be a queer refusal to rush, if only for a moment? At the end of The Magic Hour, when the audience moves back into the lobby space, the two young girls dancing seem to indicate that the performance is not quite complete—but at the same time, Dobkin has stopped “performing” a text or determined script. She explains,

In their final moments, the audience too is invited to take pause, to slow down, and to question what it means for a performance to refuse to end. We enter a new space, with new actors, a new kind of welcome, to propel us into a new performance. Here too, time feels malleable. The audience returns to the lobby where the show began, and it is unclear whether this space of performance is enacting a fictional re-creation of the past or representing an imagined future. Through the young girls’ presence, “the past is in the present as a form of a haunting” (Freccero 194). Such hauntings remind us, as Carla Freccero asserts, “that the past and the present are neither discrete nor sequential” (196). Childhood simultaneously is used as a look back and a look forward. The two young girls slip between incarnations of Dobkin’s past and the “child who might have a child” in the future. In this ’70s styled space of celebration, accented with streamers, a bowl of punch, and a pile of carefully selected vinyls from that time period, there is something familiar and strange. It is as if we are gaining access to fragments of memories that, like the generational succession of the child, might have been, but irrespective of their actual existence, culminate in a future. This queer look backwards towards what might be and what might have been rejects the compulsion to rush and allows us to take time to consider the layering of time: the ways in which an image of the past may also be a vision of the future.

29 As Dobkin explains “Asking when something is starting is also about asking when something ends,” (Dobkin, Interview). There is what seems like unlimited time for the performance to continue and an intentional uncertainty around what comes next. The repetition of greetings, varied genres, and attempts to articulate memory, shift to an ending that never quite ends. A look towards what the next greeting might be. This fluidity also shifts the performance to a performative, subverting the spatial thresholds and temporal expectations that normally dictate our roles as spectators in the theatre. We return to Dobkin questioning, “Am I performing now?” and turn the question on ourselves as we walk through the lobby. Muñoz asserts that, like Alain Badiou’s concept of “that which follows the event,” queerness should be thought of as “the thing-that-is-not-yet-imagined” (21). For Dobkin, that final return to the lobby is a space of potentiality—one that is conjured through the ritual of performance: “In my mind, there is this idea that the audience, or we, can create these spaces. What was a lobby can be something else. And that party room is my proposal for this imagined world.” As we exit the performance, we enter a world we do not quite know how to navigate. In order to leave, we must ourselves engage with an incomprehensible past, brought into the present through two little girls dancing in the centre of the room. The performance’s soft ending further extends an embodied refusal to rush and ultimately a repeated attempt to articulate trauma and sexual violence results in a dance party, a kind of celebration of how far we did not yet come. How very very queer.