Forum

Navigating the Rapids:

Teaching Bilingual Theatre Courses in Canada

1 In April 2016, we attended the final presentations of our students in a first-year acting course at Glendon College, which is the bilingual faculty of York University.1As a part of the course evaluation, the instructor, Jennifer Heywood, asked the students a variety of informal questions about what they had and had not found helpful during the semester. Amongst these was whether or not the bilingual format (English / French) was a good idea. Of the nineteen students, seventeen answered “yes” and two voted “no.” This experience renewed our interest in examining the joys and complexities of a bilingual education in drama and theatre.

2 This forum piece proposes to start a conversation about teaching bilingual theatre classes in Canada. We focus on post-secondary institutions that offer bilingual theatre, drama, and performance courses in English and French. We are aware, however, that these are not the only languages spoken in classrooms and on stages around the country, and that a course can be bilingual (or multilingual) in more than one way. What follows, however, primarily discusses courses where the instructors systematically navigate between English and French, and it centers around the experiences of four colleagues. These are Daniel Mroz, Associate Professor in the Department of Theatre at the University of Ottawa; Louis Patrick Leroux, Associate Professor of Playwriting and Dramatic Literature in the French and English departments of Concordia University and instructor of a bilingual course at the National Circus School in Montreal; Guillaume Bernardi, Associate Professor in the Drama Studies program at Glendon College of York University; and François St-Aubin, Director of the Set and Costume Design / Scénographie program at the National Theatre School of Canada.2

3 We interviewed these individuals between March and June 2016 over Skype. Les entrevues se sont déroulées en français et ont été enregistrées. Voici les questions que nous avons posées :

- Pourquoi votre institution offre-t-elle des cours bilingues? Why does your institution offer bilingual courses?

- What are the courses and who takes them? Quels sont ces cours et qui y participe?

- Comment enseignez-vous un cours bilingue? What is it like for you to teach a bilingual course?

- How do your students respond to such a course? Comment vos étudiants réagissent-ils à un tel cours?

As our interviewees have shared their rich experience with us, we will first introduce them, and then we will take a back seat and quote from them extensively.

Université d’Ottawa / University of Ottawa (U of O)

4 Daniel Mroz, who has taught in the Department of Theatre at the University of Ottawa since 2005, spoke to us about bilingual courses as they existed both before and after 2008, when the department reformed its curriculum. Avant cette refonte, plusieurs cours de premier cycle, dont des cours obligatoires, étaient bilingues. The linguistic make-up of these groups would vary from year to year, but the one common thread Mroz noticed was that generally Francophone students spoke English more proficiently than Anglophone students spoke French.

5 Quand le département a modifié son curriculum, on a décidé que les cours obligatoires ne seraient plus bilingues. « Ce qu’on a constaté, » explique Mroz, « [ … ] c’est que le bilinguisme était souvent un défi quand le cours était obligatoire, et le plus grand défi c’était que le cours était bilingue et pas le contenu du cours lui-même. » Le département a alors créé des sections parallèles des cours obligatoires en anglais et en français pour offrir aux étudiants la possibilité de les suivre dans la langue de leur choix. C’est ce que Mroz appelle une approche « co-lingue ». De nouveaux cours bilingues ont toutefois été créés « pour, justement, offrir aux étudiants la possibilité [ … ] de côtoyer l’autre groupe linguistique. » (Mroz, interview).

6 In the bilingual MFA program, the practical courses on the fundamentals and techniques of directing are bilingual. The more theoretical courses however are offered separately in both English and French, mainly because they contain a great deal of reading and are also offered to students in the MA, where they can take courses in either language. The MFA accepts two to three applicants each year, and since students have specifically selected a bilingual program, comprehension of both languages is assumed. MFA students can present their works in English or French, but must be able to receive feedback in the language of their instructor’s choosing.

École nationale de cirque (National Circus School)

7 The course Louis Patrick Leroux teaches at the National Circus School is titled “Arts du cirque : contexte et influences.” It takes place on a weekday evening from six to nine o’clock. His students are between eighteen and twenty-five years old. They are high-performance athletes who, for the most part, are not used to a conventional academic school setting: « Toute l’adolescence a été passée à faire des compétitions de gymnastique [ou] de patin, par exemple » (Leroux, interview). Previous instructors have taught this course in French, but as Leroux saw the need, and with the accord of his administration, he now teaches it bilingually. Of the twenty-eight students he taught in Fall 2015, about half understood English and French, a quarter did not speak English, and a quarter did not speak French (Leroux, e-mail).

Glendon College / Collège universitaire Glendon, York University / Université York

8 Le Programme d’études d’art dramatique (DRST) du Collège Glendon offre des cours en français, en anglais, des cours bilingues (français / anglais) et quelques cours en espagnol menant à l’obtention d’un diplôme universitaire de premier cycle.3Guillaume Bernardi, qui y enseigne depuis 2004, soutient que cette diversité linguistique ouvre la porte à « toute une palette de pratiques [d’enseignement] » (Bernardi, interview). The student body across the campus is culturally diverse, and while DRST students’ competency in English and French varies greatly, most of them have English as their language of everyday use.4

École nationale de théâtre du Canada / National Theatre School of Canada (NTS)

9 As a design graduate from the class of 1984, François St-Aubin returned to NTS on several occasions as a teacher before he became Director of the Set and Costume Design / Scénographie program in 2014. Our conversation thus centered on his spattered twenty years of experience teaching in a bilingual setting.

10 L’École nationale de théâtre admet généralement huit étudiants à son programme de design / scénographie chaque année. Il s’agit d’un programme de trois ans menant à l’obtention d’un certificat de l’école. La majorité des étudiants est canadienne, mais la réputation grandissante de l’école attire maintenant plusieurs étudiants internationaux. Cette augmentation de la population étudiante internationale se retrouve également chez les instructeurs qui viennent partager leur expertise, et dont le niveau de français et d’anglais varie énormément. Les enseignants peuvent être là pendant toute une année, une session, une semaine, un projet ou parfois même un seul cours. En 2015-16, c’est près de cinquante différents professionnels auxquels ont eu accès les vingt-trois étudiants en design et scénographie5(St-Aubin, interview).

Navigating within the bilingual classroom

11 A main question that arose in our discussions with Mroz, Leroux, Bernardi, and St-Aubin is how, precisely, they navigate between two languages in one course. While they differed in specifics, there were some similarities in their approaches. We noted, for example, that one of the underlying principles of all four educators was a willingness to alter their pedagogical practices to their students’ needs.

12 When Daniel Mroz first began teaching bilingual classes at U of O, he carefully divided the course content and time between the two languages.

Mroz quickly realized that this pattern of having to repeat everything was problematic because it took time and was boring for students. His experience teaching in the MFA, however, is different. Lorsqu’il enseigne le cours de fondement de la mise en scène, Mroz se permet beaucoup de souplesse et passe constamment d’une langue à l’autre « selon la situation et l’objet à l’étude. » Il admet : « J’essaie de me surveiller pour donner un cours équilibré qui ne verse pas complètement vers l’anglais ou vers le français » (Mroz, interview). He notices that this is more easily done in the context of the MFA because of the small class size and the advanced level of students. En effet, il soutient que « c’est la maturité personnelle et l’expérience académique et artistique [des] étudiants qui rend la communication dans l’environ-nement bilingue plus aisée » (Mroz, e-mail).

13 Like Mroz in his graduate courses, Louis Patrick Leroux performs linguistic “slaloms” during his class at the National Circus School (Leroux, interview). He is keenly aware that his is one of the few academic courses the students have within one of the best technical training schools in their field. He has learned to navigate the linguistic components of the class around a rather unusual classroom situation:

Leroux also negotiates the languages around the topics of the course. As each student has their own circus specialty, some terms are common to all, but others are not. He explains:

In addition, as the class make up is international, the students’ understanding of culture is as varied as their mother tongues.

14 Leroux’s willingness to open up the linguistic components of the class appears to have been a model for the students when they presented their own research to their peers.

15 Parfois, quelqu’un choisissait de présenter en français alors qu’il était plus confortable en anglais. Souvent, les Québécois choisissaient de présenter en anglais pour être compris [rire]. [ … ] Dans certains cas, je pense à un Allemand en particulier, [un étudiant] passait de l’anglais au français et ne s’en rendait même pas compte [rire]. Toutes les présentations pouvaient être en français ou en anglais. La plupart ont été dans les deux langues et les questions [qui suivaient] étaient vraiment dans les deux langues. On était [ … ] dans un environnement véritablement bilingue. (Leroux, interview)

16 We found that Guillaume Bernardi had similar flexibility in his pedagogical approach. In the officially bilingual courses at Glendon College, he too plays it by ear.

Due in large part to his own ability with languages (he is fluent in French, English, Italian, and Spanish), Bernardi has also found himself teaching in a bilingual way within officially unilingual courses.

The same practice occurs in classes that are taught in English, but where the students’ own skills and intellectual curiosities, along with Bernardi’s ability to meet them linguistically, end up creating a bilingual milieu.

17 The design / scénographie program at NTS is also fully aware that not all students are bilingual. François St-Aubin describes an expectation that the students work from an open “attitude,” not necessarily a linguistic “aptitude” (St-Aubin, interview). He finds students are clear if they have comprehension issues. While linguistic obstacles do not alter course content, the program will bring in whatever resources are necessary to ensure that everyone is understood and understands. As St-Aubin explains:

St-Aubin also remarked on how often, in such a small and focused group, students will assist each other. In addition, unlike in many university classrooms where technology can distract students, St-Aubin commented on how helpful personal devices such as cellphones and laptop computers can be in crossing language barriers. He admits it: they use Google.7

18 Overall, an attitude of admiration for his students seems to underlie the lengths to which St-Aubin will go to encourage linguistic openness.

Why travel a bilingual stream?

19 While it may seem a given that Canadian institutions should be able to function bilingually, we began this investigation with more pragmatic artistic questions. We wondered whether bilingual classrooms actually have an effect on the formation of artists. While each person interviewed outlined definite hurdles that they had to surmount in order to teach in such environments, they were each clear about what advantages the students derived from a bilingual education.

20 The first overt gain is that students become more proficient in another language. As educators, we are often left not knowing if students ever use what we have taught them. Yet Louis Patrick Leroux told us of a chance encounter that confirmed that they do.

21 For François St-Aubin, the benefits of studying in a bilingual environment are not only something that he gives, but that he also received. He sees his bilingual education as the element that opened another part of the world to him.

Indeed, the broad range of St-Aubin’s artistic career proves this.8

22 Everyone we interviewed found that students gained confidence from their experiences in a bilingual learning environment. Recognizing that he may be speaking in generalities, Daniel Mroz observed that because many Francophone students tend to come from smaller schools, and Anglophones from larger ones, their relationship to the theatre, upon entering his program, is different, but will change as they mingle with one another. « [ … ] Normalement, nos étudiants francophones arrivent d’écoles secondaires qui sont plus petites et où le théâtre a été rattaché à l’importance de la langue minoritaire. » They engage more openly with the material Mroz’s teaches; they are perhaps as naive as a twenty-year-old can be, but they act and play more easily, they try new things more willingly, and they tend to be less shy than their peers coming from larger English-language high schools. « [Les étudiants anglophones issus de grandes écoles] se protègent, » constate Mroz, « ils font semblant d’être cyniques, ils participent moins facilement, moins ouvertement et moins rapidement. Dès qu’ils voient le résultat de l’ouverture des étudiants francophones, les étudiants anglophones ont un très bon exemple de possibilités. » « Là, » poursuit-il, « c’était très intéressant d’avoir des groupes plus intégrés [i.e. bilingues] » (Mroz, interview).

23 Guillaume Bernardi also noticed a clear change of attitude in his students who perform in a second language. « [Les étudiants] souffrent pas mal durant le processus, mais à la fin, le sentiment de succès est fort. Ils pensent qu’ils ne vont pas pouvoir [monter un spectacle dans une autre langue], mais quand ils l’ont fait, je pense que c’est très gratifiant » (Bernardi, interview). François St-Aubin expressed a similar process at NTS. « Des fois, » il explique, « ça prend un petit peu plus de temps pour se faire comprendre. De temps en temps, c’est un peu plus délicat au niveau du choix des mots, mais [apprendre dans un environnement bilingue] ça donne une confiance aux gens » (St-Aubin, interview).

24 Significantly, each of the people interviewed was passionate about the benefits of bilingual learning. Some noted how it contributes to the opening of the mind:

Some remarked on how it expanded students’ artistic horizons:

But bilingual learning was also seen as essential for the future of our theatre:

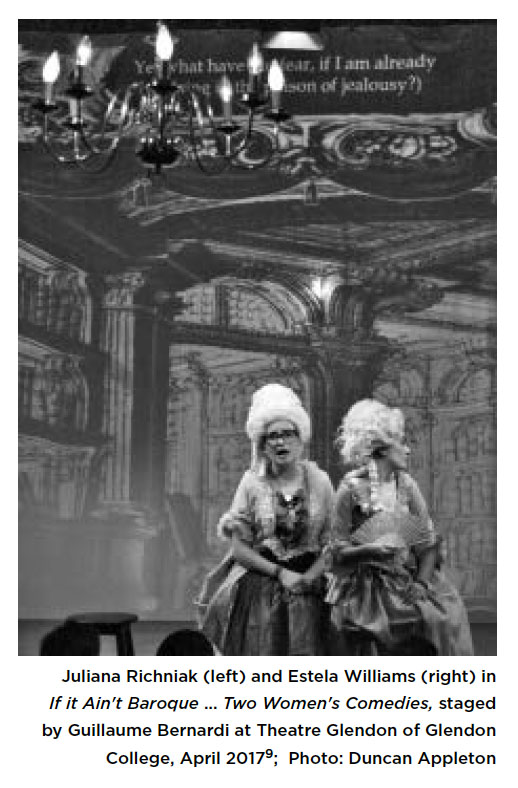

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Conclusion

25 These four conversations have highlighted for us the fact that teaching in a bilingual format is about far more than just language. Technically, its implementation depends in part on students’ level of bilingualism but also on the linguistic agility of the professors in charge. It also depends on how attuned professors are to the students’ abilities and even on what topic is being discussed. Significantly for us, learning in more than one language appears to open students’ minds and to broaden their artistic practices. This has confirmed for us that navigating between French and English in the classroom is a worthwhile journey.

26 We are aware, of course, that this forum piece only brushes the surface of a complex topic that deserves to be further developed. Toutefois, comme nous l’avons indiqué plus haut, notre objectif était avant tout d’entamer une discussion sur l’enseignement de cours de théâtre bilingues au Canada. Nous espérons que notre survol du sujet à partir des expériences de quatre collègues au Québec et en Ontario soulèvera davantage de questions et ouvrira la porte à de nouvelles discussions entre chercheurs, enseignants, étudiants et praticiens des arts de la scène.