Forum

“In Sundry Languages”:

Pleasure and Disorientation through Multilingual Melange

1 Now in the development phase of its third iteration, “In Sundry Languages” by Toronto Laboratory Theatre presents the language struggles of both new and established Toronto residents in eight different languages. Following rehearsals on and off throughout its year-long evolution, I have found it fascinating to see the progression from its initial workshop phase to its current period of refinement. The piece is based on the actual immigration or international experiences of its performing members. Each of their stories has contributed to the dramaturgical content of a series of twelve vignettes, which play with linguistic quirks, difficulties, and stereotypes. I initially participated as an actor-dramaturg in the earliest rehearsals (in April 2015) and had the opportunity to dabble in Russian, Cantonese, Mandarin, Persian, Korean, and Portuguese. Due to a scheduling conflict I was only part of the project for the first three weeks of a six-week development stage, which resulted in a public performance on May 15, 16 2015. I later caught up with director Art Babayants for an interview in February 2016 to learn about the second iteration of “In Sundry Languages” scheduled to run in early March, 2017 at the Luella Massey Studio Theatre (Toronto).

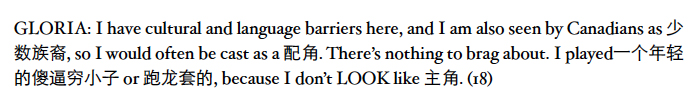

2 The first development phase consisted of working with translations of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince, personal language-centered anecdotes about life in Toronto, cultural gestures, and multilingual scenes between two or more performers. It was a trial-and-error peregrination that eventually led to a selection of scenes that were sequenced together. More than the dramaturgical content, what struck me most about working with Toronto Laboratory Theatre was the pleasure of working multilingually—a surprisingly rare experience in multicultural Toronto. Personally, I found working in other languages liberating, as one is free to make mistakes, and, because everyone is blundering at one point or another, all performers are in equal states of exploration and discovery. There are always gaps in translation and the confusion that arises is used to dramaturgical effect. The printed script—written in multiple languages—conveys this perplexity well. In one Cantonese monologue, for instance, Ziying Gloria Gao explains how she is often typecast as a sidekick, based on her minority status:

No translation is provided for the audience, so not only do the actors experience confusion in workshop, but the audience does as well. Though most audience members were in fact multilingual, few people would know enough languages to be able to follow the entire performance, creating disorientation for each person for at least some points in the show. The show thus promotes a sense of empathy by deliberately placing everyone in a position of ignorance and vulnerability.

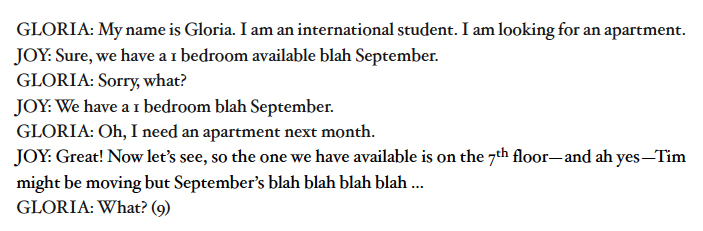

3 The stories performed in “In Sundry Languages” present some of the everyday challenges experienced by the actors due to a lack of language skills or because of their cultural background. A number of different stage setups are used to show multiple perspectives. In one scene, titled ‘Blah-blah-blah,’ for example, words unfamiliar to Gloria are replaced by ‘blahs’:

This scene, early in the performance, presents a relatively simple linguistic premise. However, as “In Sundry Languages” progresses, the situations become more complex. In one of the most linguistically confusing scenes in the play, various performers attempt to order coffee in languages other than English from two Chinese-speaking vendors. English translations are not provided, so the audience will only usually understand one side of the conversation (if that). The rest must be derived from the performers’ body language. At this point in the performance, the audience has become accustomed to the increasingly confounding scenarios, and linguistic incomprehension has become the norm—a source of pleasure akin to the grammelot often used in modern commedia dell’arte. (A grammelot is a form of gibberish or onomatopoeia often used to simulate an actual language and usually for comedic ends.)

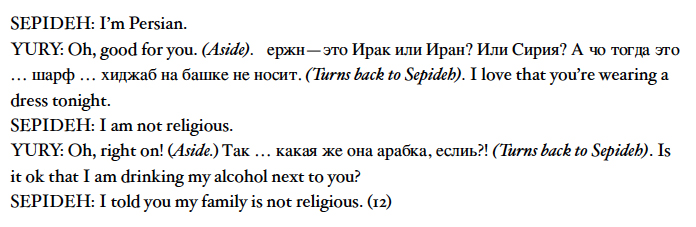

4 The confusion in “In Sundry Languages” extends beyond a basic monologue/dialogue structure as the performance also explores inner monologues. Marking their inner monologues with asides to a video camera, performers Yury Ruzhyev and Sepideh Shariati converse at a party scene:

The presence of the camera creates an almost Brechtian distance for the audience, as they contemplate both the actors in dialogue on stage and their individually projected asides. The fragmentation in such scenes not only puts into question the language of our thoughts, but also recalls one of the source inspirations for the piece: Ludwig Wittgenstein’s idea that the limits of a person’s world are the limits of his or her language (5.6 in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus). The audience cannot fully know the characters on stage without access to both their inner and outer languages. By reading the body language of each performer in association with the spoken language, both performers and audience can gradually expand their worlds, one word at a time.

5 There were a number of other inspirations for the conception of “In Sundry Languages”. In our interview, Art Babayants cites three major motivations for devising the piece. Firstly, he drew on his interest in using drama for teaching second languages. Working multilingually allowed Babayants to observe the benefits and pitfalls involved in playing with language and drama. The freedom to make mistakes in the workshop phase certainly supports the application of drama to language learning. The play also provides a means of recounting learning experiences, and perhaps even venting. In this way, it works as a piece of applied theatre, or even as drama therapy. Sepideh’s monologue, for example, presents her struggle with English interdental consonants, and is spoken along with (or against) the voiceover of a correcting ESL teacher (performed by Clayton Gray):

Many of the performers’ stories concern the dual challenges of learning a second language and adapting to life as a minority in Toronto. The piece becomes a vehicle for language exchange, but also for sharing the various challenges each performer has experienced with language learning and, more generally, with life in Toronto.

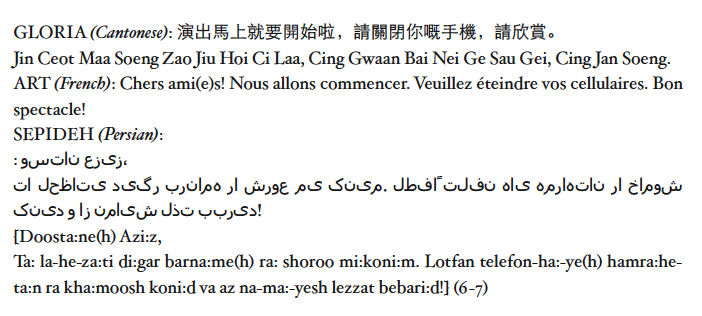

6 The second inspiration Babayants points to is a famous 1954 letter from Samuel Beckett to translator Hans Naumann in which the playwright explains the reason for writing in his second language (French) as arising from “le besoin d’être mal armé” (the need to be poorly equipped; also a pun on the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé). Similar to Mallarmé and Beckett, the cast of “In Sundry Languages” is playing with creating new forms. Working in a second (or third) language allows great potential for discovery. The artist learns the second language, but also becomes aware of what is taken for granted in the first language, in both form and content. This can be seen in the first scene of the show, titled “Turn off your Cellphones.” The actors are given full license to play for the audience various conventional pre-show messages asking them in various languages and with differing gestures to turn off their cellphones. The actors worked with transliterated versions of each message, as exemplified below:

In rehearsal, the performers played with multiple variations of this scene. Babayants noted that it was much easier for the actors to morph the words and syntax of languages that were not dominant. The confluence of languages amassed into a multilingual gibberish that was most effective when the performers spoke in their “weak” languages. Often, dominant languages (usually the first, but not always) are so ingrained that the path taken to learn them is forgotten. Consequently, it is difficult to recognize their inherent structural elements in order to break them down. It is far easier to tinker with a second language, which can frequently allow us to rediscover the structural elements of our mother tongue that are taken for granted.

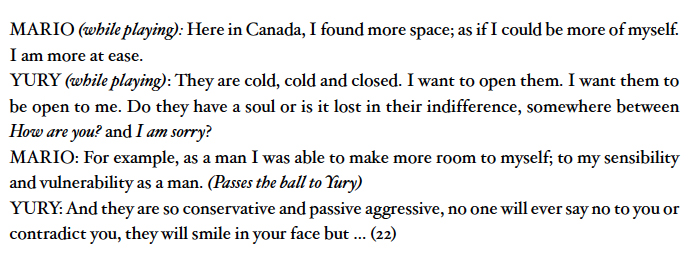

7 The final reason Babayants started work on “In Sundry Languages” was in response to Toronto’s general segregation of communities. Babayants expresses disappointment that the city is “obsessed” with its communities, yet scarcely represents them on stage and rarely explores the intersections between its communities. “In Sundry Languages” became a means for people from different cultural backgrounds to meet, both artistically and linguistically. A scene between Mario Lourenço and Yury illustrates such an encounter. In a mock futbol match, the two actors spar, exchanging different views of life in Canada:

The scene becomes a space for the two actors to literally both play and meet. The two would otherwise be unlikely to perform together as they are generally cast as ethnic stereotypes, or rarely cast at all. Indeed, the play’s prologue features a comical audition featuring Yury being instructed on how to do a Russian accent. Both Mario and Yury had similar experiences as actors moving to Canada. However, Yury is relatively pessimistic in his new life, while Mario feels he has more freedom. In rehearsal, Mario gave the analogy that language learning is like becoming a child again—an experience of rejuvenation. In meeting together in rehearsal, the performers are able to understand the many positive and negative shades in traversing new cultural territory.

8 “In Sundry Languages” thus works on multiple levels: as a venue for personal and linguistic exchange between the performers, as a means for artistic discovery in playing with different multilingual performance styles, and as a tool for raising awareness of cultural and multilingual issues in theatre, in Toronto and beyond. The new, multilingual theatre language that emerges is rich in dramaturgical possibilities, both in its use of verbal languages and in its examination of language in the body, another major point of exploration in the piece. Gestures are part of the cultural context of a language, but they may also be the primary means of communication when first attempting conversation in a second language. In the workshop stages of “In Sundry Languages”, the performers taught each other various cultural gestures they were familiar with, linked with a sound if needed. According to Babayants, it quickly became evident that even though one can mimic a gesture physically, the movements were often structurally complex. It is not sufficient to simply learn the physical shape of a gesture, but one must also learn its nuances—how large a movement is, as well as its weight, speed and rhythm—never mind understanding the contexts in which it is appropriate. Gestures can be genuinely culturally specific, but, like verbal language, they can also be a source of stereotype. This idea is toyed with in a movement sequence of the performance titled ‘Body.’ In the sequence, two female performers—Gloria and Joy Lee-Ryan (the former a Chinese exchange student and the latter a Chinese Canadian)—perform various exaggerated cultural gestures for words and actions such as “Hello,” “Come here,” “laughing,” and “thank you.” Gloria performs the actions in a calm, subdued “Chinese” manner, while Joy performs “English Canadian” gestures in boisterous or lackadaisical contrast. The scene presents a clear questioning of gesture, culture, and the body, as both performers are female and Asian, yet each moves quite distinctly. The juxtaposition is made even more ridiculous when two male actors, Mario and Clayton Gray, join them in performing the same gestures. At the conclusion of the scene, one is not only more aware of the cultural stereotypes, but also of gestures that are so ingrained in our bodies through enculturation that they are taken for granted.

9 When I spoke with Babayants in our interview about rhythm in the performance—my own research interest—he pinpointed two noteworthy elements in the piece: the rhythm of word and gesture, and the musical rhythm of the play. Babayants states that linguistic rhythm, including stress and syntax, is embodied. A person’s body language—hand movements, head gesturing, or otherwise—will often follow the beats in a spoken sentence. This would explain the added difficulty for the performers to break the rhythm of their first languages. They must break not only verbal habits, but bodily habits as well. Second language learning is a full-bodied experience and bouncing back and forth between bodies is no easy feat. The performers of “In Sundry Languages” multiply this effort by playing across eight differently languaged bodies. The result is the development of hybrid bodies, informed not by a single set of linguistic and cultural codes, but by a mixture of codes. This is further convoluted by the heightened self-consciousness or awareness of one’s first language that arises in learning a second one. With each development phase of the piece bringing with it new languages and explorations, the performers’ bodies are further complicated, reflecting the challenge that the performers’ personal identities experienced in Toronto.

10 The second rhythmic element in the piece that Babayants points to is music. In scene transitions, and throughout most scenes, Babayants plays piano to accompany the actors. The music serves not only to establish an overall rhythm for a scene and the whole play, but also works in counterpoint to the actors on stage. In an early scene titled “Where are you from,” “French Gibberish” from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times plays to give the scene a slapstick feel, playing up the clichéd questioning of Yury, who asks Joy where she’s “really” from. The accents of the piano work to punctuate the rhythm and stereotypical punchlines in the dialogue. Several other musical pieces similarly reinforce the playful stereotypes in the play, such as a modified version of “O Canada” or “pseudo-Chinese” music in the “Body” scene, which features “Chinese” gestures. They play up the possibility that certain languages and cultures are tied to particular musical scores. The result is a continuous setting up and tearing down of linguistic and cultural preconceptions in word, body, and music that leaves the audience with more questions about language, culture, and identity than answers.

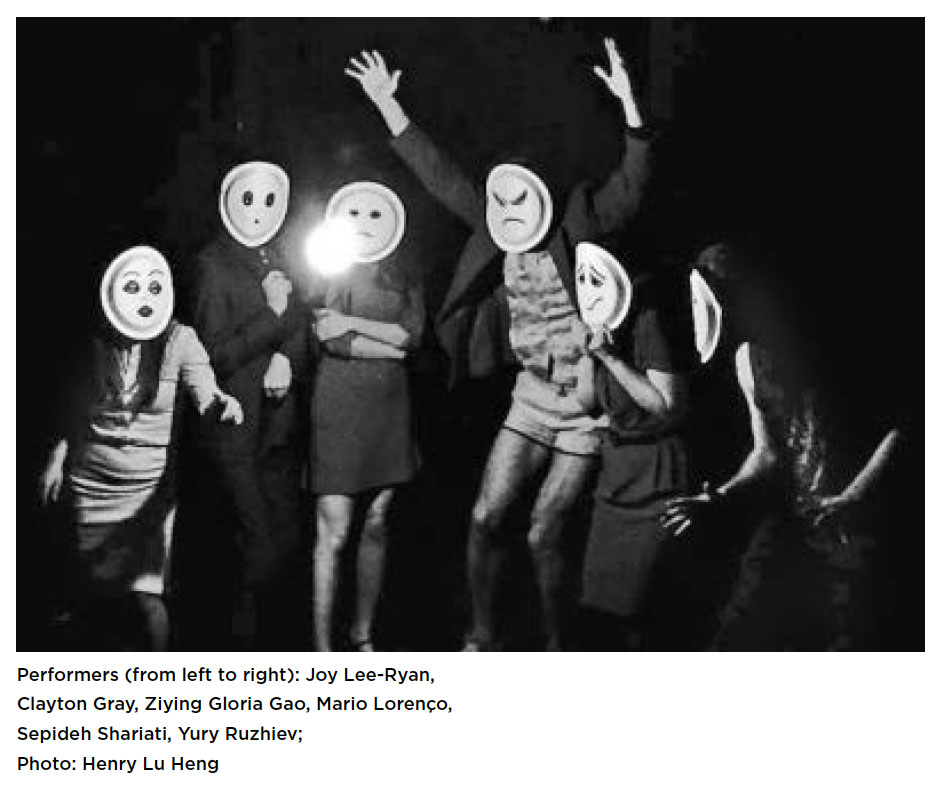

11 In the second presentation of “In Sundry Languages”, in March 2016, a mask scene that was not present in the original version was added to the production. During a party setting, paper plates become simple full-face masks for the actors, each with its own facial expression. Various abridged piano segments, such as romantic interludes or Sergei Prokofiev’s Montagues and Capulets, accompany the performers as they embody each mask. Throughout the scene, the masks are exchanged and the performers’ identities intermingle before they gradually exit, signalling the conclusion of the play. The scene was received with a different sort of confusion by a number of audience members, as it did not quite fit with the previous scenes in the play. Babayants concedes that the scene still needs more work to better clarify its place in the piece, but it is perhaps the scene that best represents the performers’ experiences in workshopping “In Sundry Languages”; it offers a microcosm of the exchange of identities that has taken place over the long-term development of the play. Each actor tries on the mask of another, and gives their own for others to discover. Body, not verbal, language becomes the predominant means of communication. The result is a hodgepodge of interactions—some entertaining, some touching, some perplexing—and while the result remains ambiguous, the confusion is a fundamental step in the performers’ journeys, as they continue to expand their individual and linguistic worlds by communicating with each other.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1