Interview

Indigenous Languages on Stage:

A Roundtable Conversation with Five Indigenous Theatre Artists

Introduction

1 Underneath the official languages of Canada and the languages brought here by numerous diasporas are the Indigenous languages of this land. These languages have been suppressed through legal assimilation measures, residential schools, and the social devaluing of Indigenous cultures and world views. Many languages and dialects are on the brink of extinction and yet Indigenous playwrights and artists are choosing to speak their languages on stage as an act of reclamation and resistance to assimilation into the colonial structures of western theatre and performance. Canada is at its root, an Indigenous country, made up of treaties and unceded territories. Many of our place names are Indigenous, including the name of our country.

2 As a student of Indigenous theatre, I asked five Indigenous theatre artists if they would be willing to be interviewed about their experiences presenting Indigenous languages on stage. What follows are excerpts from our individual conversations edited into a “roundtable” format. It is interesting to me that while the artists are diverse in their training and experiences, they have independently identified a number of common concerns and understandings. Chief among these is the understanding that Indigenous artist training needs to be culturally rooted in Indigenous bodies, stories, world views, and languages. There is an understanding that language is culture and that the meanings of words and phrases are complex. There is the understanding of the legacy of the language and of their work as artists.

3 Carol Greyeyes is a Cree actor and director and currently the Coordinator of wîcêhtowin, the Aboriginal Theatre Certificate Program at the University of Saskatchewan. Curtis Peeteetuce is a Cree actor, writer, and director, and is the former Artistic Director of the Gordon Tootoosis Nikawin Theatre in Saskatoon, formerly Saskatchewan Native Theatre. Joe Osawabine is Ojibway and the Artistic Director of Debajehmujig-Storytellers on Manitoulin Island, one of the oldest Indigenous theatre companies in Canada and the only one operating on a reserve. JP Longboat is a Mohawk dancer, choreographer, and artistic collaborator with Circadia Indigena, a collective of Indigenous artists in Ottawa dedicated to performing art rooted in Indigenous culture, languages, and relation to the land. Michael Lawrenchuk, writer and actor, is the Artistic Director of Red Roots Theatre in Winnipeg. I chose these Indigenous artists because I was aware of their work involving Indigenous languages and had the opportunity to speak to them personally at events in Regina and Vancouver. Carol Greyeyes suggested that I speak with Michael Lawrenchuk and, fortunately, I had met him many years ago at a Canada Council gathering for Indigenous theatre. It was important that they knew who I was and the work that I have done in relation to Indigenous theatre. I am grateful to them for sharing their experiences and perspectives.

4 I thank Carol, Joe, Curtis, JP, and Michael for sharing the wealth of their experience and their passion for their languages, cultures, theatre, and Indigenous performance.

5 Annie Smith: Can you talk about your training and experiences as an Indigenous theatre artist?

6 Carol Greyeyes: It took me a long time to screw up the courage to “come out” as an actor— although I’ve been a dancer from an early age. I started in a BFA at Concordia and studied filmmaking as a minor. But I needed another minor and I enrolled in an acting class. I had a fabulous teacher, Joe Cazalet, a well-known actor in Montreal, one of our Canadian gems, I think. It was in that class, when I was performing my final scene, I say that “I saw God”: I had that experience, you could say a noetic experience, where time just stopped. The words and everything were coming through me; I wasn’t in control of it; I was just kind of standing back and observing it as it was happening. It was a really powerful experience and something I’ve been chasing ever since. That happens in art—maybe there’s a religious experience— they are very similar.

7 But I was homesick and couldn’t handle the city, and I was running out of money, so I came home. I ended up going to Student Counseling to do an aptitude test. I told the counselor my whole story and she said, “I can’t tell if you have any talent and I understand that acting is very competitive and there’s a lot of luck involved, so I can’t tell you whether you can make it, but what I can tell you is that if you don’t pursue this and you don’t find out and you don’t follow your passion and your dream (because it was my secret dream to be an actor, to be a performer) you don’t want to be fifty years old and looking back and going, ‘I could have been an actor, I could have done theatre.’” So, I went into the Department of Drama at the University of Saskatchewan.

8 The training, although it was great training, was all British, American, or European. It was Western theatre. I have no recollection of any Canadian work. Forget about Indigenous. I ended up being the first Aboriginal woman to graduate from the department. It was very much, “Leave who you are at the door.” Because I was young and conflicted about my identity, I hated who I was. Part of the reason I wanted to get into acting was because I wanted to be anybody else but me. There was a lot of shame and there was a lot of confusion. I love my training; I think it was fantastic because I got to work with really talented people; I had really challenging roles—the masters of theatre—however, it took me a long time to come back to me. And it definitely was not encouraged. The university was a colonial institution and the mindset was that. But the reason I’ve been so driven to create alternate training programs is because I think it’s really important to value your stories and to value your perspective. And that doesn’t happen in the standard classroom where you are this empty thing and knowledge is stuffed into you, and you just parrot it back. That, in the creative process, is a creativity-stopper. It teaches you to distrust your own intuition and devalue your own perspective. I think we can be a lot more than that. We can bring something to the process.

9 Curtis Peeteetuce: I’ve been involved in the theatre now for sixteen years. I started in 2001 with the Circle of Voices Program which was run by Saskatchewan Native Theatre at the time—which is now Gordon Tootoosis Nikaniwin Theatre. I was twenty-six years old. I had no previous experience in theatre. I feel like one of the advantages of me being an Indigenous theatre artist in Canada is that I didn’t go through the regular cycle of training—any western or contemporary or mainstream model or paradigm. I believe it’s important for an Indigenous artist to have culture, language and history as a foundation as opposed to western or mainstream training. Everything I’ve gained in terms of experience and education in the world of theatre has come through hands-on experience, being immersed and working with wonderful mentors. Having started later in my life as a theatre artist, I think I was mature enough to be immersed right into the work.

10 The Circle of Voices is a youth theatre program. I saw a poster one day—I was working as an educational assistant at a school in Saskatoon—and the poster said, “Looking for First Nations youth ages 12 to 26.” And I thought, “Hey, I’m twenty-six. I’m right on the cusp of this.” So I sent in a resume and got an interview. The program is all about theatre, culture, and career development. It was initiated by Gordon Tootoosis, Tantoo Cardinal, and Kennetch Charlette, who were looking for opportunities for Indigenous youth in Saskatchewan in the Arts.

11 One of the statements or mantras I’ve received that I hang onto to this day is that theatre and culture are intertwined and part of the human makeup. I’ve never fully understood that statement, so there’s always something to hang on to and learn from that. It was shared with me by my mentor, who was the Artistic Director at the time, Kennetch Charlette. Those were his words. Another thing that he said that is important is, “The stage is a sacred place.” Having heard that, as someone who’d never been in theatre, who’d never been trained or experienced in theatre—I tilted my head to the side and thought—“There’s something intriguing in that—about the stage being a sacred place.” I don’t know what it is but it intrigues me and I’m going to hang on to that notion as part of my philosophy in the Arts.

12 AS: That idea of the stage as a sacred place has been bandied about for a long time going back to the ancient Greeks. More recently, in the English tradition, it came out of Peter Brook and people in the 1960’s. In the French tradition it was Artaud, then Victor Turner and Richard Schechner in the US. But I don’t know if it’s so easy, coming from a traditional Western theatre viewpoint, to fully appreciate this concept, as sacred is so often conflated with religion. An Indigenous understanding of a sacred place is different than a Western understanding of a sacred place.

13 CP: What’s intriguing about it too is that I want to know what the parallels are. What are the bridges; what are the connections; what are the access points? We shouldn’t be separate; our worlds shouldn’t be separate. We should find connections AND hang onto what is unique.

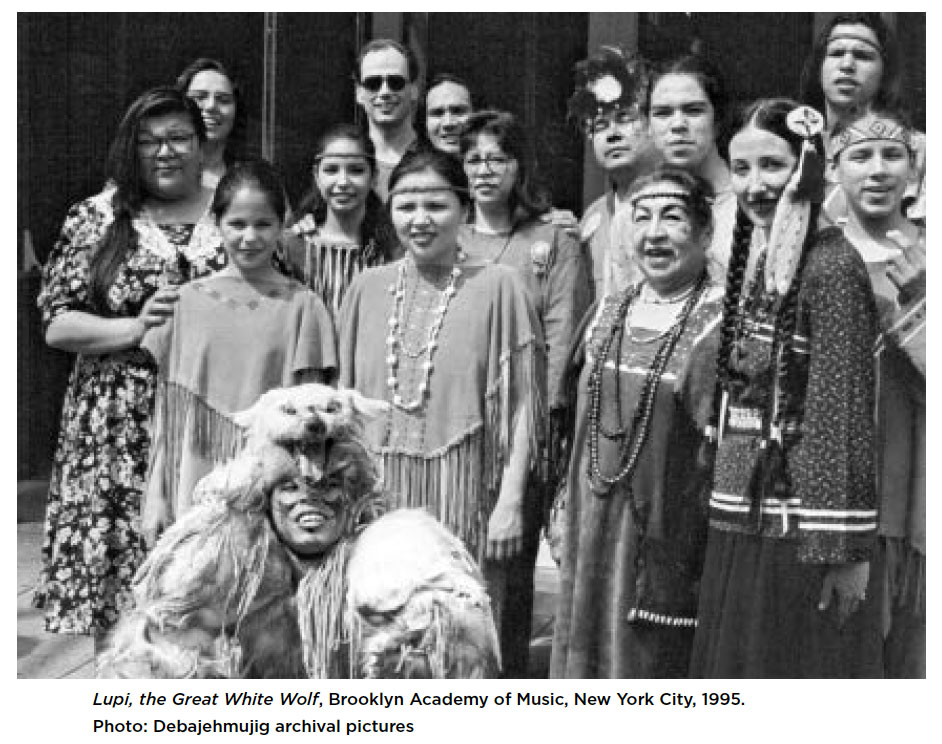

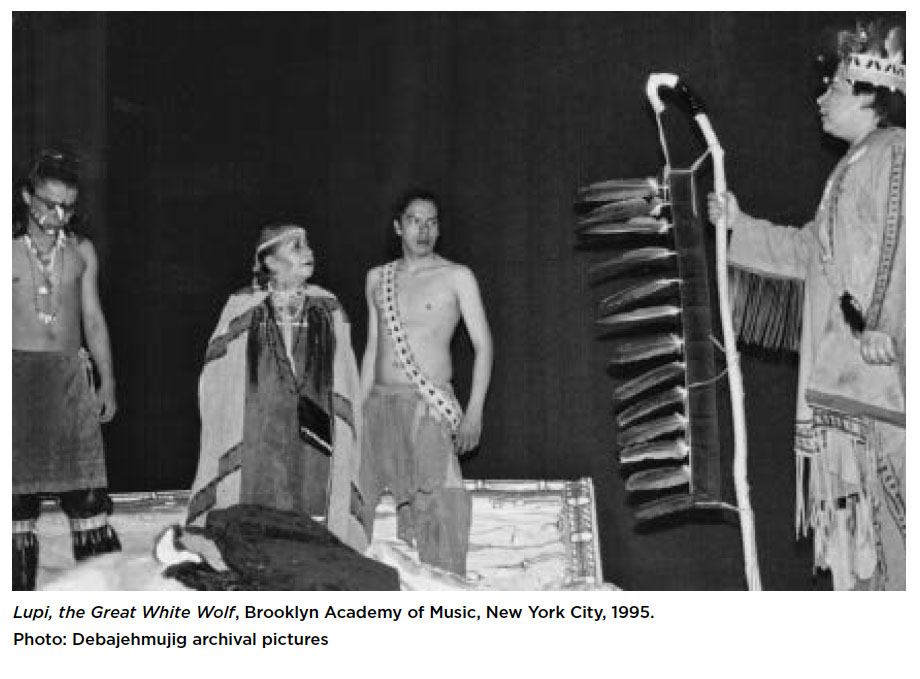

14 Joe Osawabine: My training began in the 1990s when I performed my first play, which was called Lupi, the Great White Wolf. It was the first play to be professionally produced anywhere that was all in the Anishinaabe or Ojibway language. That was my very first experience with theatre. My mother and uncle were involved in the theatre so I grew up in a theatre family. Most of my training has been provided through Debajehmujig. All of my early training was centered around the Debajehmujig production at the time. Lupi, the Great White Wolf was my first production and it was remounted the following year and we toured it around Ontario. The next year there was another show all in the language called New Voices Woman and after that was The Manitoulin Incident which was perhaps the first trilingual performance in Ojibway, French, and English. Every summer we would begin with two weeks of whatever training and skills we needed to get us ready for the production at the time. Debajehmujig would bring in a specialist or somebody who could deliver that training. We learned mask, baby clown with Ian Wallace, stilt walking, dance, movement, vocalizing, stage projection, music, singing. That’s how the training went on for years and years.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

15 AS: What is baby clown training?

16 JO: That is when your clown is born. It’s based on Pochinko style clowning or Canadian clowning, you can call it. It was based on creating masks for each of the four directions: North, East, South, West—and we also included above, below and within. So you have seven masks that you create. You work through the colours of each mask—seven colours in each direction. You are creating this world, essentially, and your baby clown is the culmination of all of these masks and all of these worlds put together. That’s when you put the red nose on and your baby clown is born. One of the folks who is renowned for it now is John Turner, who is Smoot of the acclaimed clown duo Mump and Smoot. He runs the Manitoulin Centre for Creation and Performance, formerly the Clown Farm. We’ve been working together quite a bit over the past few years.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

17 JP Longboat: My theatre training began after university. I received a BFA in graphic design and photography. I came to Toronto and worked within the corporate world for about three years. I came to a point where I realized it was not very fulfilling so I quit. I moved home to the Six Nations and started doing my own art work, mostly carving, mask making, regalia building. I realized that what I was doing had some sort of story to it. There was a narrative that was attached and that included many different levels of information, knowledge, and tradition. I got really curious about that. From there, I was getting much more interested in storytelling and, as a result, language, coming from an oral culture. Those are early foundations that I began to explore as an artist.

18 When I was probably twenty-four, twenty-five, there was the resurrection of the Native Theatre School, which is now the Centre for Indigenous Theatre. That was profound: starting to work with our cultural narrative. At that early time, Floyd Favel was the artistic director and he talked about Indigenous performance culture and how we work in the circle, that everything is connected. You don’t separate theatre from dance or music or digital arts. I felt like I was at the right place at the right time and I went right into it.

19 After that summer of theatre training I started working in and around Toronto doing theatre, mainly with Native Earth and other Toronto theatre companies at that time. The training that I was getting was about physicality, about memory in the body. We talked about old memory and how we could access that. How do we connect with our past, with our line-age? I got a lot out of trainings that sourced the body for emotional work that you could put into the theatre performance.

20 I did that for about seven years. After that, I felt like there was more than just storytelling through the English language. In my own professional development I became more engaged in sourcing the body. I did roles in plays that were entirely gestural. The Aboriginal Dance Training Program at Banff came into being in 1996. It was an easy transition. There was incredible training that was a mix of traditional and contemporary. It was a six-week program with a variety of activities that brought us into cultural awareness and process. I did that from 1996 to 2002. The last couple of years I was a choreographic intern working with established choreographers who were the trainers for that specific year. I had the chance to create work and put it on stage. It was a wonderful opportunity: to learn the whole experience from training to creative process to staging to production.

21 After that I stayed in dance. I went to Vancouver and danced with Karen Jamieson Dance Company from 1996-99. At the same time as I was dancing with the company I was also creating my own solo work. Then I transitioned to Kokoro Dance. I came into contact with James Barber and I started going to the training they did at Harbour Dance and I was invited into the company. This was profound for me because a lot of their work is rooted in ritual. I’m very interested in what ritual space is in a contemporary performance context. What kind of ritual energy you can play with and also aspects of transformation, shape shifting, and trickster. Those are the elements I began to work with and still work with today.

22 Michael Lawrenchuk: My theatre training is from a traditional Western school or tradition, steeped in Greek, Roman, English influence. An undergrad in theatre from the University of Winnipeg; post grad study at a small conservatory, the London Theatre School, in England,

23 Staging Shakespeare at the University of Exeter and a Fellowship at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London, England. Stanislavsky and Brecht are the backbone of my acting method. I’ve explored theatre as ritual, entertainment, propaganda, story, etc. I believe theatre is one of the most powerful ways of expressing the search for who we are. At its best it can show us what is best in our humanity, at its worst it perpetuates the status quo.

24 When I was younger I found and was part of an incredibly vibrant Indigenous theatre community, a community alive with telling stories of identity and struggle. There seemed also to be some interest in mainstream theatres in collaborating with us and telling our stories. I don’t see much of either anymore. Being an Indigenous artist in Indigenous theatre has always provided for me a safe place to be Indigenous, a place where I am accepted, the pain and joy of my Indigenous struggle was affirmed by those similar to me. There is great capacity and power in Indigenous theatre when working with an Indigenous ensemble.

25 I’ve always struggled to some extent about training as an Indigenous theatre artist because as an Indigenous person it is, as if at times, I am once removed from what I would call the traditional Indigenous lived experience. The Indigenous influence that I bring to theatre is from my lived experience with my grandmother and grandfather who raised me since I was two weeks old. They raised me on a trap line. Cree is my first language, stories in Cree were everywhere.

26 AS: Can you talk about a theatre production you were involved with where Indigenous language played an important role?

27 CG: I had an experience at Saskatchewan Native Theatre Company, and what they did was they took Shakespeare and they got somebody to put it into everyday English, and then they sent it to Cree translators. I was directing the play. My Cree is not great, but I knew enough of Shakespeare and I knew enough of Cree to know that there was a complete disconnect. The language experts were in the room to help the actors because the actors were not Cree speakers either. I had a Dakota, a Dene, and a Saulteaux, which is like Ojibway. So they were expected to speak Shakespeare in Cree. It was painful. Suddenly both of the translators broke into laughter, hysterically. It was in Romeo and Juliet, and Juliet goes “Ah me!” And Romeo goes, “Oh would that I were a glove upon that hand.” When the translator could get himself off the floor, he asked, “Do you know what you just said? You just said, ‘Oh, I wish that my hand could masturbate you.’” That was probably underneath that thought but … we changed it. It was hard slogging.

28 CP: The first play I was in was the Circle of Voices production, Love Songs from a War Drum, written by Mark Deiter. The concept of that play was to have an Indigenous perspective and response to Romeo and Juliet. I played Juliet’s older brother and one of the first things I learned in that production was that we can actually use our words on stage. My first Cree word in performance was [kinanâskomitin] “kin-an-as-kom-it-in,” which means “gratitude.” It is often used in prayer. I’d never spoken a word of Cree before and I was always very embarrassed and shy. I thought that the Cree language would never be in our world of theatre because no one’s going to know what we’re saying. I always thought that theatre was very Western, very colonial. So having learned my language in the first production—learned words and expressions and thoughts and values—I thought, “Wow. This is a whole new world of learning and I really love it.” Having been raised partially in my own home community, and having the Cree language in the home from time to time, I was able to make reference to that. And saying, “I want to learn my language; I want to incorporate it into my art. I want to learn how valuable it is to use these words of expression in the world of storytelling.”

29 JO: I will have to speak about Lupi, the Great White Wolf. I was twelve years old when I acted in Lupi. None of us younger cast members were fluent in the language, but we worked with the older cast members who were all fluent. The older cast members would work with us young ones until we could not only pronounce the line properly but they made sure that we in fact knew exactly what we were saying, when we were saying it. This was the first time, probably in my life, that I had ever had the experience of being able to use my own language in a conversational context. In school we were taught our language but they pretty much only ever taught us words, they never taught us how to string the words together into a complete thought. So that was a very empowering experience for me as a young person and I have been pursuing my language ever since. Today I still would not say that I am fluent but I have a pretty good grasp of the language and I can usually pick up on enough of what people are saying when speaking in the language to get the gist of what they are speaking about.

30 The play was based on the oral story that explains some of the history here on Manitoulin Island and how certain things came to be. We received the story from Esther Osche in the traditional format. It was a story she had got from her grandmother, Annie Migwanabi. Larry Lewis, who was the Artistic Director at the time, worked with Esther to change it into a theatrical production and brought in language speakers to translate the work back into Ojibway. So essentially it was a traditional story that originates in the Anishinaabe language that was translated into English and shared with us. Larry Lewis took the story as he heard it in English and wrote the play in English. At that point, language speakers were again brought in to translate the story, now in an English language play form, back into Anishinaabemowin.

31 When we remounted Lupi, the Great White Wolf this past year [2016] we again went back to the original story as opposed to going back to the scripted play form. We retold the story that way, as we as a company are constantly going deeper and deeper into our traditional storytelling roots and examining what it means to be a storyteller in today’s society, as well as what our roles and responsibilities are. So we went back and received the story again from Esther and went from there. It was told in both English and Anishinaabe, using as much Anishinaabe as we could. Again, we used fluent speakers to help us figure that part out. Again, there were younger cast members, storytellers who were for the first time ever speaking their language. I guess we have come full circle this time around. Bruce Naokwegijig and I were the older members of the cast who were helping the younger members of the cast in delivering the lines properly and making sure that they knew exactly what they were saying.

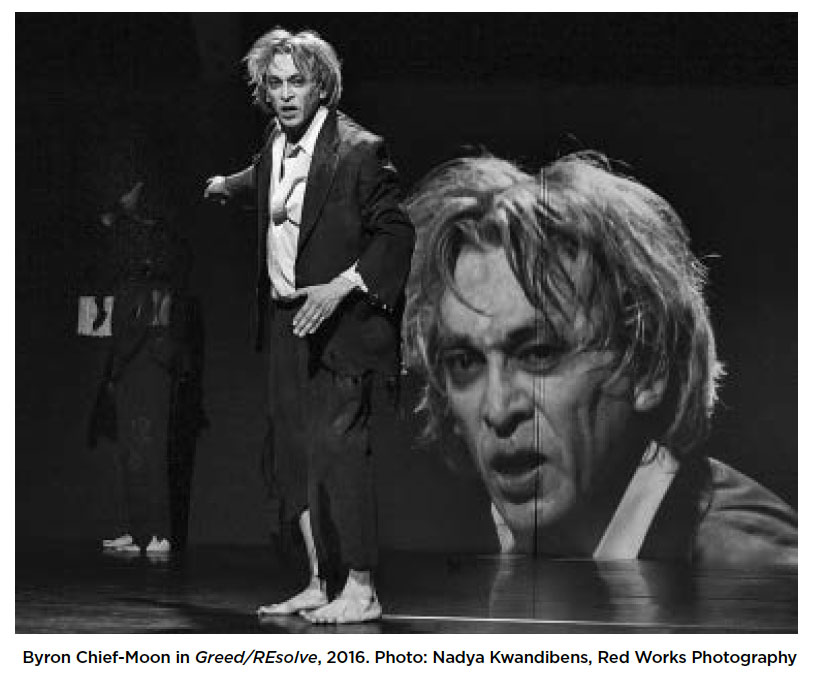

32 JPL: Greed/REsolve is a wonderful piece to speak about. I feel that the language is a part of that—our oral legacy, our stories are the foundation of Greed/REsolve. For each of the Blackfoot words we use I draw on my own concept in Mohawk. Kutoyis is the great spiritual being that came to the Blackfoot people. We’re working with pieces of these traditional stories that talk about the journeys of Kutoyis. He comes and helps the people to rid themselves of the forces that oppress them. Many of the metaphors are in the Blackfoot stories but I can bring my Mohawk cultural knowledge and relate it to that theme. We have the coming of the Peacemaker who brought the great law of peace, which is similar in many ways: a man brings peace to communities in conflict, to human beings in conflict. These are stories that teach and inform and guide us.

33 The other collaborators bring their own languages into the creation process to different degrees. Some people are more culturally rooted. Luis is from Mexico so he brings his stories to his material. I think, inherently, what’s exciting me as part of the collective, is that we make space for other Indigenous bodies. It’s not necessarily that you know your culture but that you have your connection to memory and to your ancestors; that’s what we want to work with. That’s what we want to have on stage.

34 We started with the themes and then we accessed the other layer of the stories that were told over hundreds of years. We accessed the thought that is in the language and how that affects our bodies. We choose certain phrases. We continue to speak it over and over—Byron Chief Moon corrects us but we all invest in speaking it and feeling the vibration in our bodies. We try to include it in the creative process. We bring in fluent speakers to help us. And I do that in the other creative projects I’m working on.

35 ML: The first professional production was my own The Trial of Kicking Bear, a one person show about a real life Lakota warrior and shaman during the time of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Next was Ian Ross’s fareWel. I played the role of Teddy and he addressed the characters in Ojibway. Then the production of Shakespeare on the Saskatchewan’s Othello, where I played the title role. Othello spoke a lot of Cree in this production. My one-person show The Gravedigger which I performed last year had Cree and English. In all of the productions I was the only one who spoke an Indigenous language.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

36 AS: How do actors learn to speak Indigenous languages for performance when it is not a language they know?

37 CG: I’ll give you an example: with the wîcêhtowin program we’ve included a class called Indigenous Performance Methods, which is essentially an immersion course in Indigenous language. They learn songs, they have elders coming in, so it’s all within a cultural context. They can learn the worldview. In this [most recent] cohort, they were all Cree with some Cree-Saulteaux mixed people, but the dominant language was Cree. Only one or two of them had no Cree. Some of them weren’t fluent, but they knew prayers or songs in Cree or they were taking Cree classes. We chose Cree because we are in the northern plains and Cree “Y” dialect is the most common. We have a lot of resources to do “Y” dialect.

38 They learn the language and then they learn songs, they do movement, they use performance training to learn and incorporate the language. And at the end of the class they perform for about forty minutes entirely in Cree. When we were designing the course, it was hoped that the language would make it into the final show. They take Aboriginal playwriting and they all have short scripts, and it was my hope that some of the language would find their way into these scripts. And that has happened in this iteration of the certificate.

39 When I was at university, Peter Brook was very big [with] Conference of the Birds,1 and I have to say that that was a great influence for me because of the nature of what he was doing, taking his troupe and inventing the language. The lightbulb for me was when he said, “We had this language that nobody spoke except for us, but people got the stories.” I think it’s not the way, but it is another way to advance the language, and integrate the values. We talk now about Indigenization, that’s the big buzz word. But really, the only place you can get that is in the language.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

40 CP: In Love Songs from a War Drum, our director, Kennetch Charlette, had the Cree language so he shared that and adapted it into the “Y” dialect which is the Plains Cree. He comes from northern Saskatchewan so he has the “TH” dialect. That transition is an easier one, when you’re going from the Treaty Six dialects. I had it in my upbringing so I’d heard Cree in the home and it was easy for me to pick up. We just did it one-on-one in rehearsal.

41 AS: In the work that has been done since those years, how often has the Cree language been used in productions?

42 CP: For me, it’s in every production now. I try to incorporate it everywhere I go. I think the Cree language is only alive or only believed to be alive in the classroom. I took “university Cree.” You only get three hours a week. I call it the “university dialect.” I have a seven-year-old son and he goes to a Cree immersion school. One of the benefits, I think, of the resurgence of language is that it’s alive in the community and it’s a part of our collective history in Canada.

43 AS: In terms of your productions, and the actors that you’re working with, do you have any specific training that you do with the actors for learning Cree?

44 CP: No, I don’t. What I do now is if I’m working with actors who are not Cree speakers, or if they’re not Cree at all, is bring in language coaches or keepers. We call them “language keepers” and they’re fluent in the language. Most of the time they’re educators so they know how to teach and they have that patience to share the language. People make different expressions with different words—the way words shape our faces and how we respond to that visually is something I’m very interested in.

45 JO: One summer we did a whole show that was based on improvisational theatre. We called it The Best Medicine Show because laughter is the best medicine. It was our summer theatre offering on the Island that year. We were working with a group of older community members who were fluent speakers along with the younger improvisers. We basically taught them the skills and the handles and how the Improv games worked. Once they learned the games and the handles they would perform in the language. You’d have a mixed audience—some folks would be fluent and you’d know who the fluent speakers were because you’d hear them laughing in the show. That went on for a little bit, working with that group of fluent speakers in improvisational theatre performance.

46 With all that said, our method, I suppose, has been to always put fluent speakers on stage along side non-fluent speakers. That seems to be the way that has developed for us over the years. By immersing non-fluent speakers into a space alongside fluent speakers, I think an actor can more easily pick up on the rhythm and subtleties of the language in their own performance. It is included in our mandate: “The revitalization of the Anishinaabe language, culture, and heritage.”

47 We’ve worked with a lot of young people. In the new production of Lupi there were a lot of first time speakers as well. So it served the same purpose as the very first production in bringing language back to our young people. We all learned basic vocabulary because we have Ojibway classes in our schools—but it’s not taught conversationally. You’re just taught words and names of things: pabwin = chair, doopwin = table, msin = rock, mtig = tree, mshii-mnehbaash-min-si-gan-bii-tonh-jiis-kwe-gi-na-gan = apple pie. Whereas, with the play, it was a dialogue, it was a conversation. The older performers in the show were all fluent speakers so they worked with the younger folks to get them speaking the language properly and getting comfortable with it. I know for some of us in the original play it was a foreign language.

48 AS: I think that the language is so specific to the place that you’re from. To tell the stories of Manitoulin Island, from the oral tradition, would it work to have somebody who was fluent in a different Indigenous language? Would they be able to act effectively or do they need to be from your area?

49 JO: Yes and no, I think it all comes down to intent. What is the intent of the work and who are you telling the story for? When you’re working with language I think there is a strong connection to the land and place. It’s where the stories and the language come from. If the idea is to authentically convey the stories that come from that land then yes, it should be somebody who speaks that language. If somebody’s speaking a different language from a different land, then it is not received in the same way, it doesn’t have the authenticity. With somebody who speaks Cree it might be possible because Cree and Ojibway are both Algonquin languages and we have similar stories. When you get outside of your own territory then the languages are just too different.

50 AS: What, for you, is the importance of speaking and hearing Indigenous languages on stage?

51 CG: It isn’t just about hiring Indigenous actors at Stratford. “Let’s hire diverse actors and bring them to Stratford and then we’ll just do the same old, same old—stick with the status quo.” And I think it is more than just us writing our own plays. I’ve had to really push to include the Indigenous voice and the Indigenous perspective.

52 They used to talk about the Indians who hung around the forts as “Big House Indians.” In a lot of ways, that’s what I feel like I was—hanging around the big house for the handouts and I had no influence. Now, with our wîcêhtowin program I feel we are inviting people to our house and saying, “You’re welcome to come in—you non-Indigenous students—you’re welcome to join us, but you’re coming to our house and in our house, this is how we do things.” This is how we start our class, this is how we treat each other. Wîcêhtowin means “we support each other, we work together.” Theatre is collaborative so I feel like it’s a natural fit.

53 When you put a bunch of acting students, creative students together, they’re stuck together for a period of time and they go through all these intense experiences. They do become like family but like all families, there can be that tension and little squabbles. It was starting to happen a year and a half in and the Cree teacher said, “This is the law of wîcêhtowin: in nature, things have to work together, they have to support, so you’ve got to put wîcêhtowin into practice.” But just in that one word, when we’re taking the class, you start drilling down because it means so much more. It’s not like translation; it isn’t about translation. If you think about the word, the concept, that’s a symbol of a symbol of a symbol, very removed from reality. It’s the tip of the iceberg. By using art, using theatre, performing arts, to drill down into these concepts not only can you understand the full meaning of the word— you drill down to get beyond the surface. “Theatre is just telescoping time.” Our job as artists is to unpack that, to discover all the variations that are possible and what the thoughts and images and ideas are that the character’s expression is sitting on. It’s not enough to just translate—but that’s where we’re at right now. A lot of people in theatre are trying to reintegrate language back into their performances because the people who can do theatre are not necessarily the people who know the language.

54 ML: For the most part, being Indigenous in the Canadian mainstream theatre world, I have felt unwelcome, felt the outsider. After decades of analyzing my life in theatre I’ve come to believe it is this way because, in the mainstream theatre world, being Indigenous is not the same as being human. In mainstream theatre an Indigenous artist is only allowed to play the Indigenous role, and the Indigenous role is always some form of outsider. The Indigenous artist is not allowed to play the “human” roles that make up a mainstream story. Mainstream theatre is still heavily influenced by the colonial infrastructure and mentality that permeates Canada. It is safe to say the mainstream theatre is a microcosm of Canadian society in how Indigenous people are seen and treated. Unlike British theatre that has embraced multicultural casting in mainstream productions for decades, in Canada an Indigenous artist will play an Indigenous role and nothing else, an Indigenous artist is seen as Indigenous and nothing else. Mainstream theatre has not taken the lead to humanize and therefore normalize the Indigenous artist. A tragic example of this is when Winnipeg was identified as the most racist city in Canada by Maclean’s magazine [See MacDonald]. Winnipeg’s mainstream theatre had the perfect opportunity lead the way in what is better in all of us and to embrace Indigenous artists into their mainstream productions. It chose instead to perpetuate the status quo, affirming the worst of theatre and Canadian society which it reflects.

55 CP: I’m not a fluent Cree speaker. I was just somebody who saw an opportunity and wanted to enrich my own experience with my own language. So I brought the worlds of theatre, performance, storytelling, and Cree language together. If I can do it, I think, then anybody can do it. I’m not a language expert, I’m not a fluent speaker, but I have a passion for culture, language, and history. I’ve found ways to bring my visions to life.

56 AS: Do you have traditional stories from your culture that you would like to bring forward using Cree?

57 CP: I’m more interested in stories of our history—one being Almighty Voice. I’m a great-great-great-grandnephew of Almighty Voice so that is a story I’d love to take on and share and bring to life through the Cree language. Those are the kinds of stories I’m interested in—the things we know but don’t have an in-depth knowledge of. Like the historical figures: Big Bear, Poundmaker, Little Pine … I want to know what those oral stories are and try to bring them to life. So I’m very interested in these things but the only way we can get there, to get to what means what, we have to go pre-contact. So for me, Shakespeare, Socrates, all these writings that exist serve as maps to our own past. People like Shakespeare were essentially just writing about the human condition and the human condition is universal. So we can use these as a map, to get to our own path, to try to understand our own world through the expression of written texts. And language can help us.

58 JO: For audiences that are outside the community, these are the first languages from this land. These are the voices that come from the land, the languages that have been spoken throughout this land for thousands and thousands of years. I think it’s important for the mainstream of Canada to have that opportunity to hear them as well, to recognize that these are Indigenous stories, the stories that were here before the settlers came. They’ve been pushed aside and taken away, stolen, beaten out of us, raped from our generations. It’s a small step towards reclamation of our own voice after having our languages and stories and cultures taken away from us, all those years of residential school, everything that’s been done to us. Theatre’s always been our storytelling; it’s always been a good way for us to get a glimpse into the world of the other. Especially as we’re in this time of truth and reconciliation. It’s the history that’s been hidden from most of Canada. The more we can get our own stories on stages, it’s one of the steps towards understanding, an accessible way for someone who might want to try and make that connection but doesn’t know where to go or how. It starts the conversation. It’s a way of breaking down those perceived barriers.

59 It’s important for our young people in our communities to hear the language that comes from their people, so that they hear their own stories, they see their own lives reflected on stage. I think it’s important for our young people to have a good experience with their language. Up until using it in theatre performances it was just learning words. But putting them into conversation and having that opportunity to work with the elders and the elders really making sure that we know what we’re saying and how the sentences are broken down put me on a better understanding of the language. We’re mandated to produce works that contribute towards the revitalization of the language and culture.

60 ML: I find it very rewarding as it is the language of this land. Older than any other language brought from the old country. Some of the same words were used hundreds of generations ago, and I find incredible connection through that.

61 JPL: It’s the importance of telling and retelling the stories. That’s lineage that’s foundational to the oral culture. And not only do you hear the story but you try to add to its richness in some way. Perhaps furthering its metaphors or learning. Our approach is because we work with the language and include it in our process—I include all the meaning of my words. I think that in some way the audience gets to experience that. Our approach to language is vibration: the word, the language itself has a vibration to it. All of what we’re doing on stage is interpretive so hopefully you can bring your language and knowledge and experience into that.

62 I remember, as a young person, being with the old people and those who had the language talking about direct communication with creation. I think that’s part of working with language, trying to traverse it all the way back. In the work with my mother and traditional medicine, she’d show me, in the area that we were going to harvest, a plant that was a queen, a leader. So we’d take some time to find the leader. For example, in a family of trees, if you were taking sap, you wouldn’t tap every tree. You’d understand that there were older trees that spawned the younger trees. As Mohawk people, we have our original instructions as human beings to maintain narrative and harmony. You always make an offering before you take. You have that conversation—that’s part of our original instructions.

63 I think theatre opened for me that there are memories that you can draw on in the body. You can open an emotional connection to those memories and dance has taken me through that landscape. People say that we’ve lost a lot. At the same time, something inside me says that we haven’t lost it. It’s still there but we have to find a way to remember it. To me, that’s what dance is; that’s what the kind of work I’m doing is. It’s a way to remember, to reconstruct the memory if possible, to bring it forward. In combination with that, language is so important because the culture is in the language so you start to work with the language. That’s a big piece for me going forward even if we’re not necessarily speaking the language in performance.

64 AS: What are the challenges in presenting Indigenous languages in performance?

65 CG: Cree has its own rhythm and its own expression. It’s called the “exact-speaking language” because it is so precise. That’s why some of the words are so long. That Shakespearean experiment was a really good example; it was an interesting lesson for me. When we performed it, some of it had to change. The actor who was doing King Lear was a Dakota elder. At the end of it, where he’s holding Cordelia and saying, “I’ll never see you again. Never. Never. Never,” they had this really long Cree expression and it wasn’t working. So I said, “John, in your language, in Dakota, what is the word for ‘never’?” It was perfect: “Tahk shni, Tahk shni, Tahk shni” [written as it sounds]. For the audience, even though they don’t speak Cree or Dakota, they were thrilled and excited because of the stories.

66 If you’re translating you have to make the whole journey. You have to go back, go back, get down to the reality and the worldview and allow that to inform the text, and then it comes back up. The audience just hears that top part. But for that elder to say those words holding his dead child, all the resonance came right out for him, as a parent, as an actor. And so, as a director I have to figure out how to connect the text to the actors’ world so that they can endow that text with their experience and their emotional truth so that they aren’t just skimming the surface, saying the words. They are sitting on this bedrock, this foundation of symbols. Because the word symbols are representing that telescoping of time. The symbols are sitting on top of all of those experiences and feelings, and relationships and connections. They are built not just over our lifetimes but over many lifetimes. Which is why I think it is so important that the language still be used. I think that theatre is one of the right mediums for this because, as Lee Maracle once said, “Theatre is a spirit to spirit connection.” You’re connecting with your audience and we’re all going on that journey at that specific moment in time and space.

67 ML: The only challenging production was Othello as I had to do the translation. I had to honour the rhythm of Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter and meaning. Once I found the right phrasing, I found the words and the sounds incredibly powerful and satisfying. Audience members would tell me that although they didn’t understand the words per se, the meaning was not lost to them. They found the sounds beautiful.

68 CP: We don’t have enough speakers. That’s a big challenge. I think the effects of residential schools and colonialism have made us very shy and/or embarrassed to speak our own languages. When I tried to translate a play into one hundred percent Cree the number one response I got was, “It can’t be done.” That was very discouraging. I ended up translating that play into seventy five percent Cree, which I feel is remarkable. I’m hoping that stories like that can serve as inspiration to continue and get over those hurdles and challenges and doubts that people might have.

69 AS: When you present a play in seventy five percent Cree how does the audience respond?

70 CP: Some audience members repel it because it’s not English and they don’t have the language. What we’ve done is we’ve presented surtitles above the stage. I know it presents a split focus but at least we’re providing some access to the words and their meaning. The other response is we took a Christmas show to a community of elders and there were about ten elders there who were fluent speakers. When they heard the young actors, who were under thirty, speaking Cree in the play (or at least attempting to speak Cree) they were overjoyed. They lined up after the show and they gave all of our actors roses. They were so happy and so thankful. The number one thing they felt was hope—hope and pride. One of the tricks is sharing a story that is familiar. The play that I translated and worked with other language speakers on is called How the Chief Stole Christmas. Everybody knows the Grinch story so you don’t have to educate your audience on what’s going to happen. So you can throw in the Cree expressions and words for significant parts of the story that the audiences will get.

71 JO: We are in a unique position here on Manitoulin. We are operating directly within our own cultural context and there are many things we must take into consideration, the very first being, “Who is this work for, in other words, who is our audience? And what is our intent with the work? Is language the key component?” Often times the people seeing the work is our home audience and we know many of them are fluent Anishinaabemowin speakers. So, then we have to think, “Okay, do we put the ‘professional’ actor on stage who perhaps can not speak the language but can act pretty good, or do we put the community member on stage in that role who perhaps is not a ‘professional’ actor but who can already speak the language? Where do our values lie?” If we choose the professional actor who cannot speak the language but has the acting chops, the audience will know that this person cannot speak the language and is only acting. So most often we will choose the language speaker first because we do not want to lose our audience when language is the most important thing. You can always teach the language speaker to act and occupy that space on stage but you cannot always teach the actor the language.

72 When we are touring outside our language area I think that’s where it becomes even more important, when you’re conveying the story with your whole body. It’s not just words but the gesturing and everything. “I don’t really understand what they’re saying but I feel something here. I know that they’re connected to their story. So that allows me to be connected to their story.” They can still connect on some level with a visceral response to having those words coming across with the conviction of a fluent speaker.

73 AS: Are there any other ideas that you want to bring forward about Indigenous languages in performance?

74 CG: When I became a professional [actor], many times I would get a role—for example I once played a Mohawk woman in a historical film. And, of course, she spoke her language. So I had to learn the language and make it my own. I felt that I got really good at that. For me to have that language was to be able to really get the character. Just the feeling of the words in my mouth. I played Marie Adele in The Rez Sisters, and Marie Adele has a whole speech in Cree. I acted as if I spoke Cree fluently because Marie Adele did. That, for me, is a real gift because the language takes you into the world that the character inhabits. An actor is a translator or interpreter of the text. I can tell the rhythm, like with Daniel David Moses’s work, Tomson Highway’s work, you can feel how the language, even though it’s in English, has the rhythm; it has that poetic essence. And poetry, if you think about it, is distilled language, distilled symbols. I’m going to take each of these symbols and each one unlocks a kind of perfume. There are all those notes: there’s the wood note and there’s the floral note and there’s the amber note, and I think that’s what happens in the language.

75 CP: Because children are like sponges, they soak up everything, I’d like to see more fun stuff for children in the Cree language. St. Francis School in Saskatoon commissioned me to write a short play using the Cree language. I borrowed from the Jumanji concept, of two children who are in care, who find a board game, and the board game can only be played in Cree. Once they do that, they get to go home. They get to work with the audience, interactively, to work on the Cree expressions in the play. So the audiences get to learn Cree and share their knowledge of Cree. It’s a comedy so there’s lots of laughing. The show is called Kiwek which means “go home.”

76 JO: In 2003, that’s when I took over as Artistic Director, and in 2008 we opened the Debajehmujig Creation Centre. With the Creation Centre here, this is something we never had when we were growing up. Every generation paves the way forward for the next generation. Veteran actors like Shirley Cheechoo performed with the company back in the 1980s. Their struggles were a lot more than the struggles of Bruce and myself. Now that we have the Creation Centre here there will be a whole new generation of youth who will never know what it was like to not have this. You pay it forward to the next generation.

77 JPL: The other critical point is the connection between the younger generations and the culture. Cultural transmission is very important. We feel that art is a way to do that. That is something that, to some degree, we are working with, bringing younger people into the process through mentorships and workshops. They see how we work with the stories and interpret them in this particular art form. They can see how we work in a contemporary way and all the layers within that.

78 ML: We need to embrace the language because it holds so much of what we once were. Theatre is my preferred form of storytelling. I’ve explored theatre as ritual, entertainment, propaganda, or story. What I have always found beautiful about it, regardless of which theatrical form or method the story put in front of me [is in], when it really works for me, when it really touches me, is when the presentation allows me to see past the story and the experience takes me to that special place of communing with something greater than myself, allowing me to experience the human struggle elevated to Sacred. I believe that is the commonality that all theatre potentially shares. Theatre, at its best, can be our temple, our lodge, where we are given the opportunity to commune, to experience catharsis.