Articles

Restaging Indigenous—Settler Relations:

Intercultural Theatre as Redress Rehearsal in Marie Clements’s and Rita Leistner’s The Edward Curtis Project

Sahtu Dene Metis theatre artist Marie Clements’s and settler photographer Rita Leistner’s intercultural and multi-media collaboration The Edward Curtis Project (TECP) explores the tense negotiations between settler and Indigenous characters who are brought together from different time frames through an Indigenous concept of fluidly intersecting temporalities (McVie). Clements re-appropriates the American photographer Edward Curtis’s strategy of asking his Indigenous subjects to re-enact banned rituals and ceremonies; she thus stages Curtis as a settler avatar re-enacting scenes from his past that often involve confrontations between himself and numerous historical and contemporary Indigenous subjects. In her discussion of the production, Brenda Vellino first establishes the broader theatre studies context for the conflict transformation possibilities presented by TECP. Its intercultural rehearsal of relationship renegotiation may be read as essential for substantive redress between settler and Indigenous subjects. She discusses Clements’s rehearsal of Indigenous confrontation and negotiation with the settler avatar Edward Curtis in light of a recent turn toward rereading the Curtis archive for Indigenous agency and cultural authority. She then explores Clements’s critique of a politics of mediated projection as central to both the stagecraft and questions of TECP. Finally, she considers the significance of Clements’s culminating Windigo exorcism ceremony as painful but necessary medicine for both settler and Indigenous subjects. Clements’s and Leistner’s project thus invites consideration of rehearsal as a process, practice, and trope of multi-layered relationship renegotiation between members of Indigenous and settler communities who seek active redress.

The Edward Curtis Project (TECP), une collaboration interculturelle et multimédia entre l’artiste de théâtre Sahtu déné métisse Marie Clements et la colonisatrice et photographe Rita Leistner, explore les négociations tendues entre des personnages colonisateurs et autochtones de différentes époques réunis grâce à un concept autochtone de temporalités à entrecroisement fluide (McVie). Clements se réapproprie une stratégie du photographe américain Edward Curtis, qui demandait à ses sujets autoch-tones de reconstituer des cérémonies et des rituels interdits. Ce faisant, elle met Curtis en scène comme une représentation du colon, qui rejoue des scènes de son passé reposant souvent sur des confrontations avec des figures autochtones historiques et contemporaines. Dans cet article, Brenda Vellino commence par présenter le contexte plus large en études théâtrales dans lequel s’inscrivent les possibilités de transformation du conflit que propose le TECP. Selon elle, l’exercice interculturel de renégociation des rapports peut être interprété comme étant essentiel à la réparation des inégalités importantes entre colons et Autochtones. Vellino examine ensuite la mise en scène que fait Clements de confrontations et de négociations par la personne d’Edward Curtis, la représentation du colon, eu égard à une tendance récente à vouloir relire les archives de Curtis en y cherchant des manifestations de la capacité d’agir et de l’autorité culturelle des Autochtones. Dans un troisième temps, Vellino aborde la critique que fait Clements de la politique de la projection médiatique qui serait essentielle à la fois à la mise en scène et aux questions que pose le TECP. Dans un dernier temps, elle considère l’importance de la cérémonie d’exorcisme windigo que présente Clements à la fin de sa pièce et conclut qu’il s’agit d’un remède douloureux mais nécessaire tant que le sujet autochtone. De cette façon, le projet de Clements et de Leistner nous invite à voir la répétition en tant que processus, pratique et trope d’une renégociation de rapports à facettes multiples entre membres de communautés autochtones et de colons qui cherchent à mettre en place des réparations concrètes.

(Marie Clements, Clements and Leistner 5)

1 For the past several decades, theatre has become an increasingly popular practice of cultural intervention into fractured and violent social realities. While most attention has been paid to conflict transformation theatre in transnational settings of mass violence—post-genocide, post-apartheid, and post-civil war—I wish to explore the contribution of intercultural theatre to reframing settler colonial impacts on Indigenous peoples in Canada. Sahtu Dene Métis theatre artist Marie Clements’s and settler photographer Rita Leistner’s intercultural and multi-media collaboration The Edward Curtis Project (TECP) explores the often tense negotiations between settler and Indigenous characters who are brought together from different time frames through an Indigenous concept of fluidly intersecting temporalities (McVie). Clements re-appropriates the American photographer Edward Curtis’s strategy of asking his Indigenous subjects to re-enact banned rituals and ceremonies; she thus stages Curtis re-enacting scenes from his past that often involve confrontations between him and numerous historical and contemporary Indigenous subjects. Through the device of re-enactment, Clements imbues TECP with an ethos of rehearsal. Rehearsal here works as a process in which time-intensive practice, risk, collaboration, conflict, and negotiation may contribute to a greater understanding of the difficult labour of active redress required on the part of settler subjects for rebalancing relationships with Indigenous peoples.2 Joanne Tompkins’s notion of “infinite rehearsal” further suggests that redress within settler-colonial states may require repeatedly practiced encounters, wherein consolidated identities may be unframed, renegotiated, and restaged through an ongoing process (157, 159). Clements’s and Leistner’s project thus invites consideration of rehearsal as a process, practice, and trope of multilayered relationship renegotiation between members of Indigenous and settler communities who seek active redress.

2 The Clements/Leistner project has many overlapping but distinct manifestations: the playtext written and directed by Clements; the Vancouver and Ottawa multimedia-heavy stage productions of the play; the Leistner photo exhibit accompanying each production in a gallery space in the theatre; and a Talonbooks print volume presenting Clements’s playtext alongside colour plates of the Leistner photos (2010). The play was first produced at Presentation House Theatre in Vancouver as part of the 2010 Cultural Olympiad and again in 2013 in a Great Canadian Theatre Company/National Arts Centre co-production in Ottawa. It also featured several phases of development. In preparation for the project, Clements invited Rita Leistner to join her on a fieldwork photo journey that geographically paralleled Curtis’s; together, they travelled to many North American Indigenous communities, from the Comanche First Nation in Apache, Oklahoma to Haida Gwaii to Aklavik in the North West Territories, among others (Clements and Leistner 158-159). In her published artist’s statement, Clements describes their sojourn as a process of intercultural “listening across” communities: “… we had to listen across lands and nations. So we moved across worlds in small cars, large trucks, planes, boats, and dog sled—a process of getting somewhere” (Clements and Leistner 5). “Somewhere,” as an indeterminate place, conveys a deferred arrival and suggests the ongoing nature of an unfinished journey. This process of “listening across” while also “moving across” is integral to the work of redress leading to reconfigurations of Indigenous and settler relations and power imbalances. It is important to note that while TECP is based on intercultural collaboration, the project is conceived and directed by Clements as lead Indigenous artist; this project thus demonstrates a core dynamic for rebalancing relationships—an essential component of substantive redress work.

3 TECP uses an episodic structure, intercutting scenes from Edward Curtis’s field work journeys, as well as his “picture opera” lecture tour, with the story of contemporary Dene journalist Angeline (played by Musqueam First Nation actor Quelemia Sparrow). Angeline is in a crisis over her ethical responsibilities as an Indigenous journalist; she has just won an award for her story about several children who died in an Arctic Indigenous community, a circumstance she personally witnessed yet reported in a way that reinforced Western media stereotypes. The play unfolds as a series of confrontations between Angeline and a re-animated Edward Curtis (played by Todd Duckworth). He serves as an avatar for the well-intentioned yet invasive settler character who is challenged throughout the play by both Angeline and her boyfriend Yiska (played by N’lakap’mux First Nation actor Kevin Loring). He upholds traditional practices and language revitalization as paths to cultural resurgence (Keeptwo). Several of Curtis’s early photographic subjects are also re-animated to confront Curtis’s cultural arrogance at intervals throughout the play.3 To reinforce the intercultural collision of two worlds and time frames, Clements double-casts actors who play characters from Curtis’s world and Angeline’s world: in the Ottawa production, Quelemia Sparrow played both Angeline and Princess Angeline, daughter of Chief Seattle and Curtis’s first Indigenous photographic subject; Kevin Loring played both Yiska and Alexander Upshaw, one of Curtis’s main translators; Todd Duckworth played Angeline’s father and Edward Curtis; and Kathleen Duborg played Angeline’s sister Clara as well as Curtis’s wife Clara. In the multiple rehearsals of Curtis confrontation scenes within the production, Indigenous characters from the past and present assert their cultural endurance, as well as their ethical responsibility to their community within a contemporary world still dominated by settler media constructions and popular consumption of Indigenous realities.

4 In the following discussion, I first establish the broader theatre studies context for the conflict transformation possibilities presented by TECP. Its intercultural rehearsal of relationship renegotiation may be read as essential for substantive redress. I then consider Clements’s rehearsal of Indigenous confrontation and negotiation with the settler avatar Edward Curtis in light of a recent turn toward rereading the Curtis archive for Indigenous agency and cultural authority. Next I offer a discussion of Clements’s probing questions around a politic of mediated projection that I read as central to TECP. Finally, I consider the significance of Clements’s culminating Windigo exorcism ceremony as painful but necessary medicine for both settler and Indigenous subjects. Two penultimate scenes provide a ritual container within which to confront differently internalized Windigo elements—consuming hungers, passions, and fears. Ritual structures of echo and repetition invoke a rehearsal ethos that suggests the need to practice internal self-reckoning as another prerequisite for reclaiming ethical responsibility on the part of all of those caught in the uneven power dynamics of settler colonialism. Performances of intercultural theatre such as TECP, then, potentially serve as rehearsal “spaces of conciliation,” as theorized by Métis artist David Garneau: “neutral spaces” for Indigenous practices of cultural sovereignty and settler practices of relational respect, unlearning, and new learning (35, 37).

From Transnational Conflict Transformation Theatre to the New Interculturalism

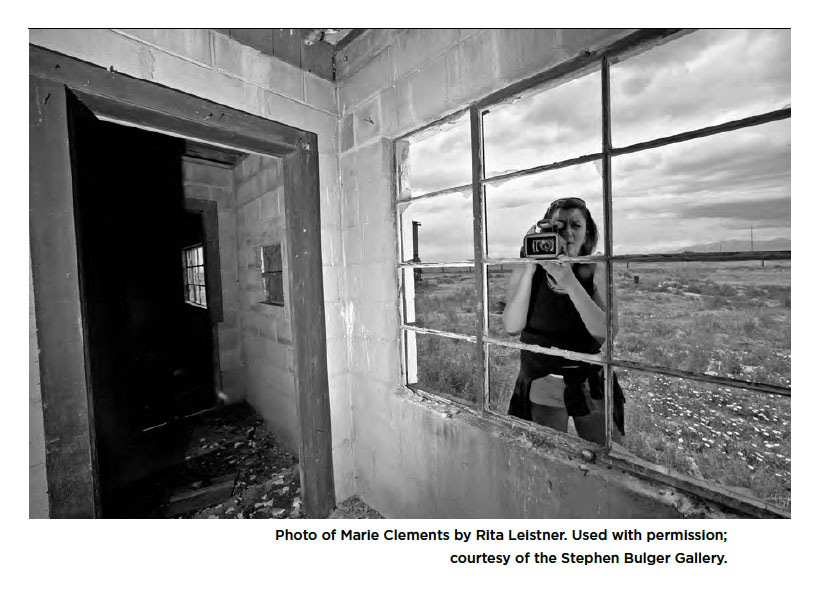

5 Two recent monographs investigate the promise of contemporary theatre as a vehicle for creative conflict transformation in transnational contexts. Thompson, Balfour, and Hughes’s Performance in Place of War (2009) examines theatrical intervention in seemingly intractable conflicts in locations like Israel/Palestine. Cynthia Cohen’s Acting Together: Performance and the Creative Transformation of Conflict, Vol 1: Resistance and Reconciliation in Regions of Conflict (2011) explores performances engaging the complex consequences of mass violence in locations like Argentina, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka. Discussion of ongoing settler-colonial violence against Indigenous peoples, however, is largely missing from human rights and conflict transformation conversations in theatre and performance contexts.4 Yet as public apologies, truth commissions, and calls for revised historical memory in settler-colonial contexts demonstrate, transitional justice initiatives are not only necessary as a response to overt contexts of mass violence such as civil war, genocide, apartheid, or dictatorships. They are also urgently required to redress the layered impacts of settler-colonial violence in societies like Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada. Moreover, much recent work in transitional justice reaches beyond official state-mandated initiatives to consider “transitional justice from below” (McEvoy and McGregor 2-3). This privileges the critical interventions, memorial practices, and alternative rituals generated by local grassroots community members, including survivors, relatives of victims, and other members of civil society. Intercultural theatre representing settler and Indigenous characters within a settler state context can be a significant mode of representing and rehearsing new transitional justice possibilities on the public stage. Because Canada as a settler state is only in the beginning stages of a long process of transforming conflicted relationships and impacts wrought by settler colonialism, such unofficial grassroots intervention by theatre artists will be essential for the many stages of redress yet to come.

6 While Indigenous playwrights like Tomson Highway, Kevin Loring, and Monique Mojica have brought complex Indigenous realities to Canadian stages for at least four decades, inter-cultural theatre work initiating Indigenous-settler conflict transformation work is less well known. Maria Campbell and Linda Griffith’s 1989 devised creation project The Book of Jessica: The Story of a Theatrical Transformation is the exception (Tompkins 147-150). Several other more recent regional plays also embody the promise and challenges of intercultural theatre for relationship transformation. Vancouver-based Headlines Theatre initiated a collaborative creation focused on land claims disputes with members of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en First Nations resulting in No`Xyà (Our Footprints) in 1987. This toured Canada and New Zealand in 1988 and 1990, suggesting the transnational reach of such plays. Ka’ma’mo’pi cik/The Gathering, another intercultural precursor, was a community play co-devised and directed by settler artist Rachael Von Fossen and Cree artist Darrel Wildcat, and mounted in Fort San, Saskatchewan in 1992 and 1993. This massive ensemble with seventy-one actors used an epic theatre style to create a narrative arc moving from settler invasion to Treaty Four negotiations to the contemporary period of Indigenous resistance and resurgence. More recently, Treaty Daze (2009) was developed with members of the Garden River First Nation near Sudbury, Ontario. It explores the impact of the Robinson-Huron Treaty and ensuing land struggles on Indigenous and settler peoples from the region (Francis).5 Each of these works explores what it might mean for settler Canadians to take seriously the process of redressing land disputes, one of the key areas requiring restitution in order to enable more just and equitable relationships between Indigenous and settler communities in Canada in the future.6

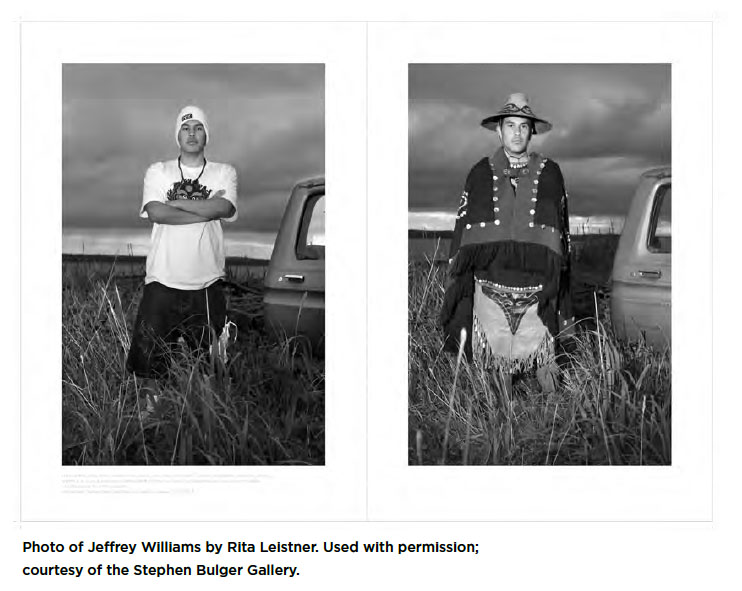

7 Clements’s and Leistner’s artistic collaboration began in 2007, one year after Prime Minister Harper’s Indian Residential Schools apology launched an official process of “reconciliation” between the state and Indigenous survivors and their families. This process included funding for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, payments to selected survivors who met government criteria, and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings process (2008-2015). While some Indigenous and settler respondents view these initiatives as positive first steps, many also regard reconciliation discourse as an “ongoing site of struggle” (3). Contributors to The Land We Are: Artists and Writers Unsettle the Politics of Reconciliation (2015) argue that artists have much to contribute to a “radical re-evaluation” of “reconciliation as contested terrain in relation to Canada as an ongoing settler colonial enterprise” (2). Redress, then, is an active verb that in tandem with Garneau’s notion of conciliation conveys the ongoing agency of survivors who make claims on the settler state for restitution.7 Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham observe that “reconciliation” and “redress” stand in “slippery relation to one another” as they get deployed in different contexts to mean different things (8-9). Yet, they also note that Indigenous and other minority communities such as Japanese Canadians are the instigators of redress initiatives; their activist demands for restitution are what compel the state to offer some measure of partial remediation for historic wrongs (5, 9). I thus wish to highlight grassroots redress as a form of political agency exercised by Indigenous peoples that calls for relational response-ability from settler respondents.8 In this context, rehearsed re-enactment of fraught intercultural relations may show promise for the substantive work of redressing the complex legacies of settler colonialism.9

8 Marie Clements’s mixed heritage identity is integral to her theatre practice of both unsettling and inviting intercultural negotiation. In her address to the 2013 CATR conference in Victoria, BC, Clements offered insight into how her Dene/Swiss/French/Irish ancestry enables her to see from multiple perspectives that “allow [her] to create across disciplines, boundaries, and genres.” Her experience of living in flux between cultural identities is formally embodied in her intermedial and inter-generic work. Clements further described her “fusion of Aboriginal and Western thought” as a “genetic structure” underpinning and forming the “bones” of her work. She is thus a leading innovator in what Ric Knowles refers to as “the new interculturalism,” a continuum of performance practices led by Indigenous, decolonial, critical race, and diasporic practitioners (Knowles, Theatre & Interculturalism 43). While the new interculturalism has promise because it involves “collaborations and solidarities across real and respected material differences” (59), as Knowles suggests elsewhere, interculturalism as a practice is complex, taking place in “the contested, unsettling, and often unequal spaces between cultures, spaces that can function as performative sites of negotiation” (“Introduction” viii). Clements’s and Leistner’s TECP instigates a practice of complex negotiation, conciliation, and redress by making visible the fracture lines and possible new modes of cultural negotiation emerging between Indigenous and settler subjects.

Re-Claiming Indigenous Cultural Agency from the Curtis Archive

9 On one level, TECP interrogates the politics of early twentieth-century photo-documentation of the “vanishing Indians” of North America by the settler photographer Edward Curtis, and through him, the impacts of settler-colonial misrepresentation and knowledge domination of Indigenous peoples. Even more importantly, TECP unsettles a reading of Curtis’s Indigenous photographic subjects as “passive victims of representational violence” (Evans and Glass, “Introduction” 10). Curtis’s historical story is shaped by his rise from poverty to fame through personal sacrifice, huge talent, and bold vision that won him the patronage of J.P. Morgan and the respect of President Theodore Roosevelt (Gidley, Edward S. Curtis 15-21, 60-63). Like TECP, Curtis’s work was produced and disseminated in many forms. He is, of course, most well known for his epic masterwork: twenty volumes of published photographs documenting over eighty nations, and titled definitively The North American Indian. This project involved nearly thirty years of demanding fieldwork; Curtis journeyed vast distances, carrying heavy photographic equipment across the southern US, Canada, and Alaska (Clements and Leistner 10; Cardozo n.p.). While Curtis’s work and reputation fell into critical neglect, his marriage failed, and he died in poverty (Cardozo), in the twenty-first century we have witnessed a “Curtis revival” (Upham and Zappia 15). This includes exhibits at the Peabody Essex Museum in 2001 (Crump), the Gilcrease Museum in 2006 (Upham and Zappia), Northwestern University, and most recently at Calgary’s Glenbow museum in 2016. Yet contemporary responses to Curtis are riven by contradictions; he is simultaneously acclaimed for his work’s artistry and contribution to the ethnographic record (Clements and Leistner 10; Upham and Zappia 40-41) and challenged for his participation in “salvage-ethnography” through practices of “photo-colonialism” (Racette 79).

10 Self-taught as a portrait and landscape artist, Curtis also experimented in emerging media; his film, In the Land of the Head Hunters, was developed in conjunction with the Kwakwakwa’wakw First Nation in British Columbia, while his 1911 “picture opera” lecture toured to Carnegie Hall and other locations to raise funds for his continuing fieldwork (Gidley, Edward S. Curtis 200, 202, 215). Marie Clements re-appropriates the multi-media method of Curtis’s “spectacular extravaganza,” comprised of “monochrome and tinted slides […] atmospheric dissolves,” movie footage, and musical accompaniment (Gidley, “Edward Curtis” 52-54). When we first meet Curtis in TECP, it is in a scene re-enacting his delivery of this “picture opera” at Carnegie Hall. Here Clements highlights his role as salvage ethnographer: a large image of his most notorious photo, titled “Vanishing Race, Navaho, 1904,” is projected behind him as he directly addresses the theatre audience, resituating them as contemporary consumers of this image (Clements and Leistner 17). In Curtis’s program notes, he writes that “this is the favorite picture of the whole series, wonderfully full of sentiment, and conveying the thought of the race […] going into the darkness of the unknown future” (Gidley, Edward S. Curtis 226). Curtis’s focus on the presumptive “vanishing” status of his Indian subjects became a defining trope for contemporary critiques of ethnographic “salvage” projects and is the focus of sustained critical parody and intervention on the part of contemporary Indigenous artists. Most extensively, urban Iroquois artist Jeff Thomas challenges Curtis’s “photo-colonialism” while seeking to recover forms of subjective agency from Curtis’s Indigenous sitters (Thomas, “Emergence” 216; “At the Kitchen Table” 128-44).

11 Rather than reading Curtis’s photographic and cinematic projects as uni-directional flows of power and cultural authority, such recent studies as Return to the Land of the Head Hunters (2014) invites a further re-evaluation of the Curtis archive. Here scholars emphasize that Kwakwaka’wakw actors in Curtis’s film In the Land of the Head Hunters should be understood as part of a “long history of theatrical self-representation to anthropologists, tourists, missionaries, and colonial agents—an aggressive and strategic form of cultural brokerage.” The Kwakwaka’wakw sought to “use the emerging market for culturally inscribed goods as a form of self-preservation in a moment made precarious by colonialist expansion” (Evans and Glass, “Introduction” 6-7). This argument shifts critique away from a disempowerment narrative to one of intercultural encounter in which savvy Indigenous subjects used the modernist means available to them to preserve their cultural identity. Like this study, TECP also pushes for “a recovery and recognition of Indigenous agency within colonial contexts of exchange” (Evans and Glass, “Introduction” 10). Clements and Leistner suggest that even Curtis’s controversial practice of staged photographic reenactments of “authentic” cultural practices such as dances and ceremonies may be re-situated as tactical strategies of cultural preservation on the part of Indigenous collaborators in a period when the state banned ceremonies, dances, and regalia (Evans and Glass, “Introduction” 17). Similarly, in a playfully self-reflexive stance, Clements looks through the double frame of camera lens and window at exhibit-goers and readers in the cover photo of the book version of TECP, as if she is about to snap our picture. Seizing the means of production and the power of self-representation, Clements stands within a continuum of Indigenous artists who seek to reclaim agency and cultural sovereignty.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

12 In TECP, Clements uses Curtis’s own re-enactment strategy to introduce a larger-than-life version of his former self on the lecture tour stage, exhibiting an unquestioned sense of cultural authority over interpretation of his “Indian” images. Curtis’s opening monologue, using text taken verbatim from the historical Curtis’s lecture tour notes, refers repeatedly to “primitive man” situated in “strange” and “mysterious” lands (Clements and Leistner 16-17; Gidley, Edward S. Curtis 219-221).10 While these are familiar tropes of romantic primitivism, his strategy of transporting audience members “in a flash of time” to a “far away enchanted realm” via the “magic” of modernist media and interpretive oration serves to highlight the theatricalized nature of his “authentic” representations (Clements and Leistner 17; Gidley, Edward S. Curtis 219). Clements’s restaging of Curtis’s performance within her play, as well as her projections of photographic and cinematic images on screens surrounding the stage, thus highlights the ways characters and audience members alike must negotiate a complexly mediated world. Such self-reflexive attention to mediation not only heightens a contemporary audience’s awareness of the ways in which Indigenous and settler peoples’ power relations are scripted and framed, but also reminds us that they are subject to re-negotiation through the mode of rehearsed re-enactment.

13 Rita Leistner’s photographic contribution to TECP also attends to the politics of mediation. In contrast to Curtis, Leistner was self-reflective about the power of her medium: “How could I photograph Aboriginal Peoples […] without repeating the appropriations and objectifications of colonial photographers and ethnographers?” (McBride n.p.). As a non-Indigenous artist photographing Indigenous community members, her method was to develop a collaborative practice in which Indigenous subjects were invited to present themselves in a manner that explicitly foregrounds their control of the image-making process. When a Haida youth actor asked to be photographed in both his cultural regalia and his “street clothes” and then posted these paired images on Facebook, Leistner notes: “so began the diptych series that became a central motif […] a photographic exploration of past and present, traditional and modern, as presented by the subjects themselves” (Clements and Leistner 73).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

14 Leistner explains that the diptych format demonstrates an “increasing integration of modern and traditional dress that shows that the long fight for survival is being won” (Davidson n.p.). The diptychs, as she further explains, speak back to Curtis’s projections of Indigenous disappearance to address the question, “what happens when a vanishing race doesn’t vanish?” (Clements and Leistner 71). During the Ottawa production of TECP, a number of Leistner’s colour prints were displayed in a parallel exhibit in a mezzanine gallery in the Great Canadian Theatre Company building, reminding theatre goers of the layered complexity of contemporary Indigenous subjects who embrace both ceremonial regalia and motorcycles, prom dresses, and hip-hop culture; they further disrupted contemporary audience expectations for cultural authenticity as that which resides in the past. That Leistner’s Indigenous subjects adopt the diptych form suggests their intrinsic awareness of the rehearsed nature of presentations of the self, fluid realities that are subject to interpretative negotiation between Indigenous artists and non-Indigenous respondents.

Shattering the Frames of Projection11

15 In the Ottawa production of TECP, Marie Clements’s use of large-scale screen projections self-reflexively emphasized the politics of projection, mediation, and spectacular staging central to the epic scale of Edward Curtis’s own project.12 In a demanding, immersive, two-hour performance, audience members were compelled simultaneously to decode multiple screen images while attending to the unfolding dialogue and narrative arc.13 Theatrical space was established by a minimalist set of wedge-shaped risers that functioned as couches, beds, tables, chairs, and podium platforms in a variety of domestic and public settings: Angeline’s family home, Carnegie Hall, Angeline’s apartment, and her sister Clara’s office. The rest of the scenography was created via the complex image choreography of the projection designers, Jamie Griffiths and Tim Matheson, working with 4 projectors and 17 variably sized screens (McVie). Upstage, multiple rectangular smaller screens topped a panoramic wide screen, while the playing area at centre stage was framed by angled stacked screens on stage left and right. Images of Angeline’s family photos, Curtis’s own photos, photo animations, and film footage were variously intercut with, superimposed upon, and directly engaged by character action and dialogue. This busy projection choreography emphasized Clements’s re-appropriation of such mediation in order to wrest artistic, subjective, and political agency from past and present misrepresentations. “Projection” as theatrical device also works to augment Clements’s challenge to the limits of settler colonial subjects’ futuristic predictions (of the vanishing of an entire peoples) and mapping of expectations, views, and ideologies onto Indigenous others.

16 Clements’s use of photographic projections and framing devices unsettles contemporary audience assumptions about the uni-directional flows of power and cultural agency in settler-colonial spaces. In the Ottawa production, characters often stepped in and out of photo frames, a strategy that evoked Clements’s layering of space, time, and character. In the stage directions in the published volume, Clements uses the trope of photographic development to indicate how Curtis’s “portrait develops up” as it is re-animated when the Todd Duckworth character steps out of the frame of a projection of Curtis’s self-portrait (16). At later moments in the play, the main Indigenous characters Angeline and Yiska have an early Edward Curtis photo projected directly onto a wrap-around blanket or shawl; they “breath into” the projected images and appear to re-animate them. Angeline’s character transforms in this way into “Princess” Angeline, the daughter of Chief Seattle and Curtis’s first photographic subject. Yiska’s character transforms into Edward Curtis’s Crow Nation translator, Alexander Upshaw. This re-animation of Indigenous photos is most critical at moments in the play in which Edward Curtis is put on trial not only by his contemporary interlocutors Angeline and Yiska, but also by his past subjects, who haunt the stage. For instance, Clements disrupts one of Curtis’s Carnegie Hall lecture scenes as the eyes of his photographic subjects stare back at him interrogatively. Disturbed, Curtis is compelled to stop his show: “They are looking at me . . . stop looking at me . . . […] I’m sorry we seem to be having technical difficulties . . . let us take a short break” (47). Clements’s strategy of animating still photos through cinematic screen projections or actor inhabitation of a projected image opens up a central tension in TECP: photography is treated as both a medium that frames, fixes, and freezes its subjects in time, and a medium whose images are subject to performative reinterpretation so that their meanings across time, space, and subject position do not remain static. As Wanda Nanabush notes, “in Clements’s re-examination of Curtis, the constructed and performative nature of the photograph is deployed for narrative depth. […] The photo as document or testament to a past then must be conceived as a performative re-presentation and not a reproduction of reality.”

17 At every turn, Clements rehearses this tension for readers and audience members. While the episodic playtext offers no formal subdivisions into numbered acts and scenes, segment breaks signaled by the stage direction “Frame Shift” indicate temporal and locational transitions, as well as character exits and entrances. Clements defines “Frame Shifts” as “a matter of focus and perspective that is both physical choreography and photo-manipulation incorporating close up, long shot, wide shot, studio, landscape, and cultural ranges of seeing” (Clements and Leistner 9). There are more than twenty-eight “Frame Shift” stage directions in TECP, choreographing a dynamic interaction between character encounters and photo and film projections throughout the piece. Clements explicitly uses the disjunctive structure of “Frame Shifts” to convey “cultural ranges of seeing” (9)—suggesting how critical reframing that instigates the ability to see from different perspectives must be repeatedly rehearsed for meaningful renegotiation of relationships to take hold.

18 The narrative arc of the play unfolds through a series of confrontations and negotiations between paired characters; rehearsal of negotiation reminds the audience that this is a process requiring repeated practice in order for redress based in reimagined relationships to be possible. In a number of linked scenes Angeline confronts Curtis, who appears in lucid dream sequences in her contemporary living room. In their first encounter, Curtis wants to project his assumptions onto her just as he did with so many of his photographic subjects: “I’m going to call you/SLIDE CAPTION: “Primitive Indian Wo . . .” (19). Angeline interrupts his assumed ethnographic authority with a tongue-in-cheek counter-representation: “/Aren’t you going to ask me what I call myself? […] I call myself “Most Beautiful Woman You’ve Ever Met” (19-20). She builds from this comic moment to instruct Curtis that his name for her is as presumptuous as his pet name for himself, “Chief” (he claims this as a term of respect awarded by Indigenous friends). Here Clements instigates a take-down of settler self-importance via Indigenous humour, a strategy that maintains relationships even as it corrects and instructs. In several other linked scenes where Yiska confronts Curtis, settler unsettlement takes place partly though Yiska’s speaking of several Indigenous languages. As the play progresses, Yiska speaks variously in Piegan (or Blackfoot) and Squamish when his character doubles as Curtis’s translator Upshaw. In this way, rehearsal of Indigenous languages on stage both unsettles the listening experience of all non-speakers and asserts the need for Indigenous language reclamation.

19 Throughout TECP, Clements critically re-animates Curtis to rehearse moments of confrontation in which Indigenous subjects exercised forms of agency to block, deter, or forbid his access to their culture. In one crucial encounter, Yiska steps out of the frame of a 1904 Curtis photo, animating the image of an Indigenous subject in a Buffalo robe, to interrupt another re-enacted scene from the “picture opera” lecture wherein Curtis claims to answer the presumptuous question: “What is an Indian?” (Clements and Leistner 26). Yiska challenges the settler avatar, asserting: “(in Peigan) I am not for your eyes . . . lower your need to see what is not for you. I am not for your eyes […] Step backwards one clumsy foot at a time, backwards toward your own knowing. I am not for your eyes” (27). While the historical Curtis lamented the “secretiveness so characteristic of primitive people, who are ever loath to afford a glimpse of their inner life to those who were not their own” (“General” xiv), Yiska’s denial of cultural access is re-enacted as a sign of Indigenous agency through a refusal of a settler-colonial politics of projection and consumption. At several other moments in the play, Yiska and a re-animated Alexander Upshaw signal their resistance to other Curtis intrusions (39, 51-53). Later, Curtis acknowledges that such moments where he is challenged are familiar (“I’ve been in this situation before […] my very presence was a curse”; 52, 56), yet this is not enough to overcome his cultural entitlement. Multiple interventions by Indigenous subjects past and present suggest that part of the ethical work of rebalancing relations on the part of settler subjects will mean “stepping away” from a presumptuous politics of projection. Clements suggests through the Curtis avatar that settler subjects need to learn respect for “irreconcilable spaces of aboriginality,” theorized by David Garneau as “separate discursive spaces” where Indigenous peoples exercise cultural practices that are situated “beyond trade” (32-34).

20 Breaking culturally conditioned interpretive frames is central to Clements’s critique of the politics of projection in both Curtis’s time and our own. Yiska’s reference to Curtis’s Indians being “frozen in time without the possibility of seeing what survival looks like” (53) is echoed by Angeline’s reference to the dead Arctic children from her news report as “frozen in time,” tragically beautiful images framed by social and media projections (57). Clements traces a genealogical continuum between the nostalgic ethnographic gaze and the contemporary elegiac gaze of the liberal settler subject who may see such reserve fatalities as a tragic inevitability. The play opens with an intimate spotlight on Angeline, who introduces the audience to an album of portraits of her mixed-heritage family projected on multiple screens above and behind her, as well as to stage right and left. Her own portrait depicts her holding a journalism award for her story on the Arctic children’s deaths, while her voiceover newscast of the story interrupts the family narrative and signals the beginning of her personal crisis. The “facts” of her news story—three Aboriginal children dead from hypothermia in the Arctic due to neglect by a young father who accidentally left them outside—have parallels with a January 2008 incident on the Yellow Quill Reserve in Saskatchewan and its problematic mainstream media coverage. Several stories focused on the alcoholism of the father and the criminal charges laid against him, without addressing social contexts.14 As the play shifts frames from introducing Angeline’s ethical crisis to Edward Curtis delivering his “Vanishing Indians” lecture, Clements establishes a continuum between early ethnographic salvage projects and contemporary media distortions of twenty-first century Indigenous social realities. These function as a “national curriculum” that situates settler readers as empathic consumers of “Indigenous tragedy read as pathology” (Anderson and Robertson 8; Henderson n.p.). Clements’s twinned critique of the social harms of Curtis’s photo-colonial project and of contemporary mainstream media representations intersects with the work of contemporary Indigenous journalists such as Duncan McCue (Chippewa First Nation). Similarly, Angeline awakens to the possibilities of journalism practices grounded in an Indigenous ethics of responsibility to community through deepening awareness of the social contexts that need to be redressed (McCue, “Seeing Each Other”).15

21 Early in the play, when Angeline finds herself emotionally unable to join a family dinner convened to celebrate her journalism award, the projected image of this family riven by mixed race tensions literally breaks apart, through a series of photo poses caught in the repeated staccato glare of a camera flash bulb. (Repeated “Shutter, Flash. Frame” stage directions mark this in the text for readers.) Angeline sums up her desperate urge to break free of twinned social expectations and media projections: “I looked at them—and all I wanted to do was get out. Get out of the picture that was made for me—get out of the picture I had made for myself. Get out of all the lies that had framed me” (13). In the Ottawa production, this moment culminated with Angeline shattering the family dinner portrait as she broke the fourth wall by slamming a high-heeled shoe in the direction of the audience. Simultaneously, a projected image of breaking glass covered the entire stage, while shattering sounds filled the space. When the proscenium arch of the stage was temporarily made visible as a wall of glass that had just been shattered, the audience was directly implicated in the politics of projection. While her sister Clara assumes she is having a breakdown, Angeline feels she is “having a . . . break . . . through . . . I am breaking through . . .” (15). One of Angeline’s principal struggles in the play centres on breaking the frame of her complicity with the mainstream media as an Indigenous reporter. When Clements orchestrates four moments in which Angeline relives her initial discovery of the children’s bodies in the Arctic snow, this traumatic replay emphasizes the context for her deep despair as she wrestles with her responsibility to the children, their father, the community, and ethical representation of their realities. Here, repetition rehearses the difficult work of reckoning with the primary trauma, as well as with the struggle to break through the politics of projection that inform conventional modes of seeing Indigenous subjects.

22 In a climactic scene near the play’s end, Angeline awakens to an Indigenous ethics of responsibility that might reframe future journalistic endeavours:

YISKA: You wrote the facts. You wrote what you were expected to write.

ANGELINE: Did I? I didn’t write the real story […] I wrote that an Indian father was drunk and dropped his three kids in the snow . . .

YISKA: He did . . .

ANGELINE: Did he? Or did we drop him a long time ago? I should have written that the father of those children was so young, so poor . . . living in a house that was so contaminated it should have been torn down . . . Living between cardboard walls with no food, no clean water, no phone, no heat, and the only reason he decided to go out into minus-thirty-eight weather was because one of his kids was sick . . . He went to get help . . . Do you think it was all his fault? Or maybe we all should own a little piece of it? (45-46)

In this scene, Angeline challenges her complicity in writing the story from the perspective of the mainstream media, rather than from her place of community responsibility as a Métis woman with a deep understanding of the contexts surrounding this painful loss of young Indigenous lives. Clements via Angeline politicizes intersecting practices of ethnographic and media projections of Indigenous peoples in order to create new possibilities for ethical representation and response-ability essential to redress. Angeline’s collective challenge to herself and the audience members—“maybe we all should own a little piece of it?”—is a summative statement that reflects back on each of the confrontation scenes between paired characters throughout the play, asserting that co-responsibility is essential to any future redress. Clements thus evokes a rehearsal ethos of repeated practices of relationship renegotiation. Over time, this might unsettle, disturb, and even shatter frames of projection that maintain unequal social divisions between settler and Indigenous peoples.16

An Intercultural Windigo Confrontation Ceremony

23 Métis scholars Jo-Anne Episkenew and Michelle LaFlamme both offer a model of Indigenous theatre as ceremony, offering “good medicine” for “the release of historical and racialized trauma” (108). Similarly, Clements invests her penultimate scenes with the power of ceremony so that both settler and Indigenous characters are immersed in a ritual of confrontation with their (differently experienced) haunting and consuming hungers. Clements foregrounds Indigenous hunger as a central preoccupation of TECP. When she recreates an exchange between Curtis and his first photographic subject, Princess Angeline, she emphasizes that Angeline trades her photographic image for money to buy food, initiating a recognition of food scarcity among turn of the century Indigenous peoples. In an exchange that takes place in Coast Salish with projected English translations appearing on a stage left screen, Alexander Upshaw (Curtis’s translator) insists on a fair exchange of wage for portrait—“For this she agrees that a dollar would be an equitable trade between artists” (58). Angeline then confronts Curtis with the starvation politics of settler colonialism: “Diggin’ … diggin’ … diggin’ … for food that used to be a feast and now is nothing but leftovers. … You have made me hungry” (59). Elsewhere in TECP, Curtis is as obsessed with cooking for the contemporary Angeline as he was with feeding his historic Indigenous subjects: “I couldn’t stand watching them starve to death over and over and over… everywhere I went … starvation, death, incarceration, hunger … They were so hungry I would cook for them every chance I got … every goddam chance I got … Goddamn it!” (54). As well-intentioned bearer of liberal settler guilt, Curtis cannot make the connection between his own hunger to capture and consume images of a “vanishing race” and his implication in the genocidal politics of the settler state.

24 Clements orchestrates a final charged confrontation and conciliation ceremony in TECP’s two penultimate scenes through the creation of a fictional “Curtis Indian” character symbolically named “The Hunger Chief.” Through a ceremonial setting that the Hunger Chief instigates, Clements deepens her exploration of hunger by invoking a Windigo figure, the all-consuming, cannibalistic, supernatural being from several Indigenous oral traditions (Dene, Ojibway, and Cree, among others) whose cultural meanings shift across regions, contexts, and time frames (McKinley). The Hunger Chief confronts Curtis by creating a Windigo purging ritual for him (as he will also do in the next scene for Angeline). Gerald McKinley offers a contemporary understanding of Windigo stories as teaching stories regarding the “starvation Weetigo,” a symbolic embodiment of the conditions of extreme hunger and deprivation induced by settler colonialism, such as that experienced by Princess Angeline (36). For McKinley, as for other thinkers like Ojibway elder Basil Johnston, physical starvation is linked with “cultural starvation,” while those prominent settlers such as Indian Affairs agents, priests, or cultural ethnographers may be read as “conspirators with cultural starvation” and therefore manifestations of “Modern Windigo” figures (McKinley 51; Episkenew 176).

25 In this penultimate scene, The Hunger Chief’s confrontation of Curtis is infused with ritual tone and structure through Clements’s use of incantatory, choral, and repeated lines. Here both Curtis and the Hunger Chief take on aspects of “Windigo” figures. While the stage directions call for animated photos of Curtis Indians to have a spectral presence on stage, in the Ottawa production Clements established the dream-like, ritualized mood with a panoramic projection of a misty early morning on the upstage screen, augmented by dryice fog rolling in from stage left. A soundtrack of murmuring voices conveyed the spectral effect of numerous Indigenous subjects haunting the stage and standing with The Hunger Chief in this final confrontation: “The only way a white man can become an Indian is to starve. You want to come inside . . . You want to live with the Indians, then you must die with us. Come inside . . . Come inside. Come inside our belly” (59-60). In Clements’s stage directions, the Hunger Chief symbolically compels the Curtis character to experience divestment from his settler-colonial assumptions by cutting away his clothing until he is “left standing almost naked,” an “action of becoming bare” (60). In the Ottawa production, The Hunger Chief physically confronted Curtis with huge silhouetted gestures suggesting he was ripping out Curtis’s guts and ingesting them, a startling symbolic violence implying Curtis’s urgent need to become aware of settler-induced physical, cultural, and spiritual starvation. The stylized and ritualized nature of this encounter rehearses the painful process of ripping away settler projections in the journey toward redress.

26 The Hunger Chief repeats key lines backed up by a multi-voiced chorus to remind Curtis of the genocidal context underpinning the ethnographic salvage project: “I am and remain thin. I want to eat. We want to eat. I don’t want to be sick. I want to eat well” (60). Curtis then echoes these lines in a call-and-response fashion. Repetition here, as elsewhere, evokes the rehearsal ethos of the play as Curtis is compelled to practice what it might mean to learn to see from an Indigenous perspective. The Hunger’s Chief’s focus on starvation in this scene recalls the material devastation of settler colonialism: forced removal from hunting grounds, forced marches and relocations to reservations, decimation of subsistence animals like the buffalo, forced dependency on inadequate government food rations—all resulting in malnutrition, slow starvation, and illness. Physical starvation was matched by cultural and spiritual starvation generated by settler state prohibition of the very ceremonies that Curtis and others sought to preserve for the ethnographic archives. Here Clements stages a retroactive human rights claim by restoring missing context to the Curtis archive and demanding recognition of the genocidal politics that underpinned his and others’ salvage anthropology (Keeptwo). Clements further suggests that Curtis’s insatiable passion for projecting and consuming images of Indians is a Windigo-like urge that is eating him from the inside out: “There are teeth inside me, inside the pit of me gnawing nothing because there is nothing to consume. Eating flesh that is mine to get out. Eating me from the pit of my belly, from the pit of my being” (61). Here Curtis manifests as a “Modern Windigo” who perpetrates the “cultural starvation” of settler colonialism, as well as suffering from spiritual “gnawing” and existential emptiness (McKinley 44, 5-51).

27 Directly after The Hunger Chief compels Curtis to submerge in water as the culminating moment of his ritual confrontation with his consuming hunger, he initiates a second Windigo exorcism ritual for Angeline. In the Ottawa production, he called up a snowstorm, suggested by a projected panoramic image of falling snow to make the visual and spatial transition to the Arctic tundra. As Angeline again returns to the scene of her discovery of the frozen children’s bodies, she echoes Curtis’s internalized Windigo language: “I am cold …so cold. They are inside of me, inside the pit of me gnawing, gnawing until there is nothing […] Eating me from the pit of my belly, from the pit of my being” (62). Angeline, as a Metis woman struggling with her Indigenous identity and the responsibility attending it, experiences cultural and spiritual starvation as a Windigo that consumes from within. Possible healing for this inner gnawing, Clements suggests, is both communal and ritual. The Hunger Chief asserts four times that “We eat together,” implying that collective feasting has a ceremonial and a curative function. After feasting, he compels Angeline to re-enter the winter storm that embodies her fears of contemporary vanishing (63). Here, however, she is not alone; she is joined by Yiska, by her sister, and by Curtis, who all take turns at narrating the traumatic moment of her discovery of the Arctic children’s bodies in the snow. Collective re-narration by both settler and Indigenous subjects ultimately signals that each must take up interconnected responsibilities to ensure cultural survival is possible and ongoing. Together Angeline and Yiska assert, “We have survived despite what you can, or cannot, see […] We have survived despite what has or hasn’t been said […] We have survived across time, across place […]” (66-67). During this closing scene, all screens in the Ottawa production were populated with projections of Leistner’s contemporary photos of tiny reserve homes in the Arctic. These suggested resilience and endurance, as well as the ongoing work that needs to be done to ensure adequate housing for First Nations peoples in the future. Despite the somewhat abruptly optimistic ending, the play leaves the audience with the haunting communal narration of the children’s deaths and a challenge to take up collective responsibility for addressing the myriad conditions that contribute to such deaths.

28 In these last scenes, orchestrated by the Hunger Chief, Clements constructs an inter-cultural redress ceremony. The labour of redress for the settler subject involves being confronted, stripped, and gutted, and thus made accountable. For the Indigenous subject, Angeline’s journey suggests the way forward for a community-based ethics of representation. In turn, the possibilities of a relational ethics underpinning Indigenous self-representation and settler response-ability provide grounds for asserting contemporary Indigenous continuance and resurgence. As both an intercultural and interdisciplinary undertaking, The Edward Curtis Project disrupts the politics of settler projections for Indigenous peoples and provides numerous ways (both on the page and on the stage) to rehearse the complex labour of rebalancing relationships. This is a key component of redressing settler colonialism’s impacts. It is thus important to consider how, after the stage lights dim and the actors and audiences go home, this play, and others like it, might keep instigating redress rehearsals. In the classroom we can make space for such work, animating theatre’s potential to create “spaces of conciliation” where grassroots redress processes may continue to be engaged by both Indigenous and settler subjects.