Articles

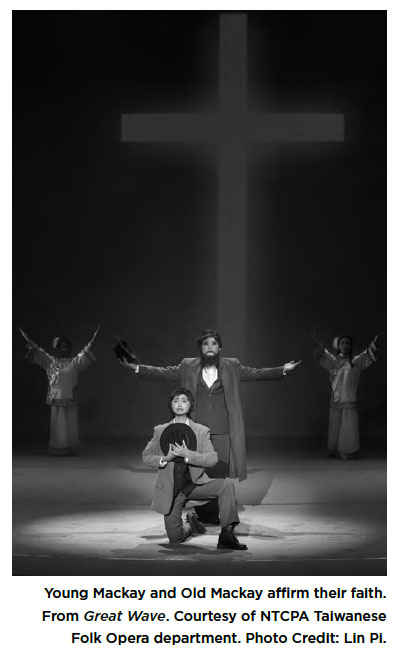

Staging the International Embrace:

George Leslie Mackay Narratives on Taiwanese Stages

Josh Stenberg considers three Taiwanese productions of the last ten years (puppetry, Western opera, xiqu), which have dramatized the life of nineteenth-century Presbyterian missionary George Leslie Mackay. The article connects the way in which a Canadian white foreigner is represented on stage with Taiwan’s anxiety surrounding its lack of international recognition, arguing that Mackay has been enlisted in Taiwanese nation-building theatre as a wish-fulfilling stand-in for desirable foreigner behaviour. Since the legitimacy and characteristics of an autonomous Taiwanese consciousness (like Canadian identity) are disputed and evolving, this case serves to examine theatre as a medium during an embryonic stage in the production of nationhood: the Mackay productions are theatre for a nation that—depending substantially on foreign attitudes—may or may not yet be produced. Furthermore, attention to this Canadian character abroad broadens the discussion of Canadian intercultural theatre by drawing attention to how, since identities are dialogic, Canadians are not the only ones who get to decide who we are or what we mean.

Dans cette contribution, Josh Stenberg examine trois productions taiwanaises des dix dernières années (théâtre de marionnettes, opéra occidental, xiqu) qui ont adapté pour la scène la vie de George Leslie Mackay, un missionnaire presbytérien du XIX e siècle. Dans son analyse, Stenberg établit un rapport entre la représentation dont fait l’objet sur scène un étranger canadien de race blanche et l’anxiété ressentie à Taïwan face au manque de reconnaissance de ce pays à l’échelle mondiale. Selon Stenberg, le théâtre taïwanais qui est au service de l’édification du pays se sert de Mackay pour représenter le comportement que l’on souhaite voir chez l’étranger. Puisque la légitimité et les caractéristiques d’une conscience taïwanaise autonome (comme l’identité canadienne) sont encore contestées et en pleine évolution, ce cas nous permet d’examiner le théâtre en tant que medium au cours du stade embryonnaire d’une nation en devenir, sachant que les pièces sur Mackay sont destinées à une nation qui—en grande partie selon les attitudes des étrangers—pourraient ne jamais voir le jour. Qui plus est, l’attention portée à ce personnage canadien à l’étranger sert à élargir la discussion sur le théâtre interculturel canadien en nous rappelant que puisque les identités sont dialogiques, les Canadiens ne sont pas les seuls à même de décider qui nous sommes et ce que nous signifions.

Introduction

1 On a stage in the Performance Hall of Lotong Township, on Taiwan’s east coast, two female college students are singing Taiwanese-language prayers. One of them wears a beard, the other a bowler hat. A projection of the crucifixion appears on the curtain behind them. Western spectators might need some time to get their bearings, especially as further young, ethnic Chinese women playing white men appear on stage, but for the Taiwanese audience, this is a familiar story: only one of several recent stage versions of the life of nineteenth-century Canadian Presbyterian missionary, George Leslie Mackay (1844-1901).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

2 According to the conventions of this particular genre, known as gezaixi,1 the principal male characters are played by women, in this case one beardless (the young Mackay), and the other sporting Mackay’s trademark black beard (the older Mackay); in this duet, the older Mackay is remembering his youthful vigour, while the younger Mackay is foreseeing his lifetime of missionary devotion.2 How did a Canadian Presbyterian missionary come to be a part of gezaixi, often considered the quintessential Taiwanese performing art, and branded in English as “Taiwanese opera”? Indeed, why has Mackay become a mainstay of the Taiwanese stage in the last decade? One point of entry into this question is to consider the instrumentality of white foreigners in Taiwanese consciousness and indeed throughout the Sinophone world.

3 Claire Conceison, a scholar on Chinese spoken theatre, has noted that she, as a white foreigner on the streets of China, is often “the object of persistent staring and pointing and of comments uttered with the assumption that I cannot understand them” (2), an experience to which many China-resident visible foreigners can relate. However, given the voluntary and privileged nature of most white foreigners’ presence in China, many will react to experiences that foreground their otherness by “internaliz[ing] ‘righteous anger’ as an unavailable, indefensible option” on account of “feelings of guilt due to recognition of this privileged status” (4). Conceison’s personal experience of the unequal (generally privileged) treatment of foreigners in China serves as her point of departure for her book-length examination of the way foreigners have been portrayed on the contemporary spoken-theatre stage in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

4 To date, there has been no corresponding study of depictions of foreigners on the stages of the Republic of China on Taiwan. Despite the political, social, and cultural distinctions between Taiwan and Mainland China, the reception history of Western people is not dissimilar, and in both territories Western presence or acts have often served to define, legitimize, authenticate, or challenge events, behaviours, and products.3 Despite their power, “images of the West have never evinced pure admiration or envy. Rather, they have always been laced with ambivalence about the other and the self, as well as the ambiguous power relations between the two” (Moskowitz 333). Moreover, Western historical figures on stages in the Chinese-speaking world are inscribed in a “cultural crisis, a conflicting inferiority/superiority crisis that Chinese society has faced since its earliest contacts with the technologically superior Western world in the nineteenth century” (Brady 26). This ambivalence about the East Asian self vis-à-vis the West is exacerbated in the Taiwanese case by the fact that the state (the Republic of China) exists in an international grey area, recognized at present by only a handful of countries with minimal international influence.4 The residents of Taiwan, aware that they live in an essentially unrecognized state and constantly confronted by debates about their national, ethnic, and cultural identities, are troubled by their absence from the international political system. A recent scholarly survey of popular views found that “all Taiwanese [prioritize] two goals: (1) trade and economics and (2) respect and international space, with only a very small preference for economics over respect” (Gries and Su 93-94).

5 Naturally, the Taiwanese government and its inhabitants look on international ignorance of, or indifference to, Taiwan with consternation.5 Because he can serve as a sociocultural ambassador to an indifferent and ill-informed West, a figure like Taiwanese-American basketball player Jeremy Lin has been consistently “portrayed and defended as a national hero who increased the nation’s global visibility” (Su 474), an observation which could be validly extended to golfer Yani Tseng or baseball player Chien-Ming Wang, or in the cultural field to figures such as Ang Lee or Jay Chou. Any evidence of international recognition, no matter how oblique, is seized upon by the Taiwanese media and government alike.6 As these examples indicate, cultural diplomacy is an element in the “government’s attempt to build legitimacy with its own people” (Alexander 21), and the failure of successive ROC governments to obtain membership in international organizations, or formal diplomatic relations with major or even middle powers, causes popular dissatisfaction and contributes to the instability of the population’s identity. In such an environment, the views and acts of foreigners, especially those assigned the cultural premium of the Western world, take on an exaggerated importance.

6 Theatre is one of many genres of cultural production that participates in the shaping of any national identity, and in Taiwan xiqu (Chinese opera) has been a particularly influential genre. Until at least the 1980s, Jingju (“Beijing opera”) formed an important plank in the Chinese Nationalist government’s program for projecting an international image of the Republic of China as the guardian of legitimate Chinese culture. With the rise of a distinct Taiwanese consciousness, indigenous7 Taiwanese forms have been enlisted in the creation of a distinct (and often autonomist) Taiwanese consciousness. Gezaixi has even been hailed as the “the embodiment of Taiwaneseness” (Hsieh 28), and modernized offshoots of the puppet genre budaixi “are associated in Taiwanese public discourse with both traditional Taiwanese culture and clever adaptation to the changing global economy” (Silvio 150). Xiqu in Taiwan, far from being the repository of an unchanging tradition, has repeatedly manifested its usefulness to competing sociopolitical agendas, and governmental support for troupes and training has been a constantly contested feature of Taiwanese culture policy (Stenberg and Tsai).

7 This article examines the intersection of a Canadian white foreigner represented on stage with Taiwan’s anxiety surrounding its lack of international recognition, arguing that the missionary George Leslie Mackay has been enlisted in Taiwanese nation-building theatre as a wish-fulfilling stand-in for desirable foreigner behaviour. Such productions are thus primarily funded, performed, and associated with those branches of Taiwanese political debate and action which are Taiwan-centred rather than China-centred. Taiwan is a complex postcolonial entity, and the political grey area that forms the background for this article also produces fraught terminology. Among several possibilities with currency in sociopolitical contemporary discourse, I am choosing “Taiwanese consciousness” to describe the growing reorientation of the Taiwanese population towards Taiwan as a social, cultural, and political whole, and a corresponding decrease in the proportion of the population that regard themselves as “Chinese people” (Zhongguoren), even as most acknowledge or embrace Chinese ethnicity (Huaren).8 Taiwanese consciousness versus Chinese consciousness is also a dynamic which dictates theatrical genre, with Taiwanese-language genres received as being “local” Taiwanese, while Mandarin-language genres must fight the perception that they were governmentally imposed.

8 Insights from Canadian scholarship can be usefully applied to aspects of Taiwan’s situation. If “Canadian literature as an international commodity depends upon the external validation of Canadian cultural products” (Roberts 5), the same is even truer of Taiwanese cultural products, which must navigate the international market without political recognition or use of a dominant international language. Alan Filewod’s observation that “Canadian nationhood is a constantly changing historical performance enacted in an imagined theatre” (Performing Canada x) could be equally applied to Taiwan, as can his observation elsewhere that a recent turn in theatre history as written in Canada has moved from “investigating how the nation produced theatre” to how “theatre produced the nation” (“Named in Passing” 123). Since the legitimacy and characteristics of an autonomous Taiwanese consciousness are highly disputed and constantly evolving, a case study such as this serves to apply this model to a more embryonic stage in the production of nationhood. The Mackay productions are theatre for a nation that— depending substantially on foreign attitudes—may or may not yet be produced.

9 Parallels can also be found with Quebec. Autonomists in Taiwan and Quebec “share in a search for national identity in the face of global and regional pressures over which they both have limited control” and “see themselves on the political periphery in relation to central authorities […] and both are challenged by counter claims of the nation state” (Drover and Leung 206). Taiwanese consciousness is an identity that emerges in opposition to a historically hostile state, and with no international recognition of the nation existing or probable. In this, “Taiwanese consciousness” can be considered roughly analogous to québécité in that it is envisaged in opposition to an alternate, state-driven project (Létourneau 159). However, the stakes of Taiwanese nationalism are (arguably) higher, in that any move towards independence is met with threats of war from China, while closer integration with China is feared by autonomists to mean the extinction of Taiwanese consciousness under a one-party, anti-regionalist, illiberal state.

10 The discussion of “intercultural theatre” in Canada continues to focus on how incorporation of “foreign” or “minority” influences on theatre productions at home may be “cynically exploitative” or else “may finally be beginning, not only to reflect but performatively to help produce an emerging, multiplicitous and hybrid range of ways of being Canadian” (Knowles 5). Limiting the focus to theatre physically produced in Canada runs the risk of parochialism on the one hand, and underestimating the stature of Canada and Canadians abroad on the other. East Asian theatres adopt, adapt, and alter Western productions, themes, narratives, and genres in ways which foreground local agency. Taiwan’s Mackay productions, with their “whiteface,” romantic projections of the Rocky Mountains, and alterations to history, ought to remind the Canadian theatre scholar that Canada and Canadians can also be tailored for Asian consumption, be admired as an exotic object, or act as the Other by which to fulfill or project aspirations. The East Asian careers of Anne of Green Gables, Dashan (Mark Rowswell), or Norman Bethune as emblematic cultural figures pose interesting questions about representations and self-representations of Canada that await critical inquiry. Identities are dialogic, and Canadians, like any other people, are not the only ones who get to decide who we are or what we mean.

11 To explore Mackay’s deployment by Taiwanese theatre makers, I consider three recent dramatic productions about the life of Mackay, paying close attention to narrative content and production context. The first production, Mackay in Formosa, was performed for the Taiwanese glove puppet genre budaixi, and filmed in 2006 after a few years of live performances; the second, a gezaixi production calledA Great Wave Strikes against the Shore—Taiwan’s Son-in-Law, Mackay (Dayong lai pai an—Taiwan zixu Majie) was premiered in 2013 and has been in frequent performance since then; and the third is a Western opera called Mackay— the Black Bearded Bible Man (Heixu Majie), which was given a monumental production at the National Theatre in 2008. Though varying hugely in scale, venue, and target audience, the three productions in their myriad ways attempt to deploy this historical figure for broadly shared political purposes. Specifically, in the context of Taiwan’s uncertain political status and diplomatic isolation, Mackay’s biographical narrative becomes a formula for strengthening Taiwanese consciousness by staging international recognition of Taiwan.

Mackay in Taiwanese History and Memory

12 Born and raised in southwestern Ontario’s Oxford County, in a “community that had been transported virtually intact from Sutherlandshire, Scotland” (Austin), Mackay received his education at Presbyterian institutions in Toronto, Princeton (New Jersey), and Edinburgh, before embarking for Taiwan in 1871 as the first foreign missionary of the Canada Presbyterian Church. Over the thirty remaining years of his life, he worked as a medical missionary in Taiwan, pulling over 21,000 teeth, establishing sixty churches, conducting three thousand baptisms, and establishing Oxford College (now Aletheia University). He was famed for his command of the local language, Taiwanese9 (which he had learned, as all three productions narrate, from herdsboys), and his writings expressing love for Formosa10 are often quoted by church publications and in Taiwan histories. As an author, Mackay’s principal work was From Far Formosa, a report that helped begin to define the island for an English-speaking readership, and is a key text for historians working on Taiwanese Christianity and related subjects. Due in substantial part to Mackay’s efforts, the Canada Presbyterian Church was to have a formative influence on Taiwanese Protestantism, especially in the north of the island (English Presbyterians had begun missionary work in the south in 1865). The Presbyterian Church remains the island’s largest Christian denomination,11 and there is a growing consensus among historians that, despite relatively small numbers, “missionaries like Mackay, and certainly their native converts, are central components of the Taiwanese historical narrative, not merely exotics on the fringes of society” (Rohrer 45-46).

13 In the representation and imagination of late-nineteenth century Taiwan12 today, whether in museums, histories, cultural products, or institutions, Mackay remains probably the most famous Western individual. Mackay’s missionary and medical legacy is especially visible in the port of Tamsui, now a district of New Taipei City, through street names, statues, and museums. His name remains broadly recognizable to Taiwanese, not least on account of the Mackay Memorial Hospital (headquartered in Taipei with several branch hospitals and clinics throughout the island), the principal medical institution of the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan.

14 However, Mackay’s fame has ebbed and flowed. During the years of Martial Law (1949-87) in Taiwan, Mackay’s memory seems to have been principally tended within the Presbyterian Church, and through publication and commemoration in the Church’s medical and educational institutions.13 For one thing, Mackay’s comments on non-Christian Taiwanese society may not have been welcome to Nationalist authorities committed to representing themselves as guardians of a moral tradition.14 However, since the end of Martial Law and over the same period as Taiwanese consciousness has grown, Mackay’s memory has gained substantially in prominence (see Forsberg 112). A bibliography of Mackay materials shows twenty-two of thirty-one total books on the missionary were published in the period between 1997 and 2012, and all but twelve of eighty-seven articles since 1991 (Fang 56-62). In 2001, thirty Taiwanese, including government representatives, travelled to Mackay’s native Zorra Township, Ontario, for the unveiling of a plaque commemorating the centenary of this “national hero in Taiwan” (The Presbyterian Record), which Taiwan also marked by issuing a stamp (Loevy and Kowitz 77). Among creative works using the Mackay story in recent years are the anime series Legend of the Black-bearded Barbarian (Heixu fan chuanqi), a Christian musical script Mackay Musical (Majie yinyueju; both 2012), and the manga Love and Devotion: The Story of MacKay15 (Ai yu fengxian: Majie de gushi, 2015). The popularity of Mackay narratives and research is, not coincidentally, coeval with the post-Martial Law period, during which “Taiwanese consciousness increased in all social, political and cultural arenas” so that in the creative arts a “Taiwan-centered position” and the “independent originality” of Taiwanese work has been foregrounded (Tu 101).16

15 Mackay narratives also provide the opportunity for proponents of Taiwanese consciousness to perform warm international ties with a Western nation: Canada. The Canadian Trade Office in Taipei (the special diplomatic mission that manages informal Canadian relations) has not failed to recognize the potential for goodwill represented by such a figure, the most recent expression of which was an exhibition in its Mackay Room, running from December 15, 2014 to January 16, 2015. The exhibition flyer proclaimed in English and French that Mackay was “an extraordinary Canadian in Taiwan,” while in Chinese, the exhibit was called “Love makes a foreign land into a homeland: Dr. Mackay’s destined passion for Taiwan” (Ai zai taxiang bian guxiang: Majie boshi de Taiwan qingyuan). The executive director17 Kathleen Mackay (no relation to the missionary) wrote in the accompanying flyer that the Presbyterian missionary’s “contributions to Taiwan’s development in the late nineteenth century set a high standard which all Canadians—along with others who love Taiwan—continually strive to meet” and that “Taiwanese came to understand Canada [through] Dr. Mackay’s hard work and dedication to the people of Taiwan” (K. Mackay).

16 It is thus only a slight exaggeration to claim that Mackay is “regarded as a national hero of the Taiwanese independence movement[,] as a symbol of its own pre-Japanese history independent from the mainland” (Ion 186) partially a result having been credited, anachronistically, “with a kind of political prescience, defending Taiwanese independence long before it was fashionable or tenable” (Forsberg 112). Most Taiwanese accounts of Mackay today, many of them sponsored or published by Presbyterian institutions, present a wholly positive—often even a hagiographic— view of the man. As a result, they have no choice but to soften for the general public the severe Calvinism that fired his missionary zeal. Inevitably, he was a product of his time, harbouring “no reservations about the superiority of his Christian faith and British social, economic, and political traditions. He came to Formosa to elevate heathen one and all to a higher religious and material plane as he saw it” (Forsberg 114). As a consequence, frequent (and unsurprising) references in Mackay’s writing to the “dark, damning nightmare” of traditional Chinese religions (G. Mackay 125) or to the “cruel savages in the mountain [whose] orgies rose wildest into the night” (14) are wholly elided from popular Taiwanese representations of Mackay today.

Structure of Mackay Narratives on Stage

17 All three Mackay productions under examination here feature sufficiently similar outlines, treating the life of Mackay from his arrival in northern Taiwan to his death, that they can be presented as a joint overview. The similar narrative content shows the closely related sociopolitical goals of the productions.

18 Many episodes in these productions are apparently drawn directly from From Far Formosa, a work which, as its introduction stated, was intended to “stimulat[e] intelligent interest in the cause of world-wide missions” (Macdonald [Mackay 6]) and to “help [the] fulfilment” of “God’s purpose” for Formosa (G. Mackay 339), i.e. the conversion of the island. The various scripts are thus substantially and consciously generated from material that was pious, promotional, and autobiographical. Both Bible Man and Great Wave directly quote Mackay, with the text of the concluding aria in the former adapted entirely from the first paragraph of From Far Formosa. Each script features:

- Mackay’s arrival on the boat in Tamsui, the natural beauty of which overwhelms him;

- Mackay learning Taiwanese from initially frightened herdsboys. In both non-puppet versions he first elicits their interest with a watch, then an unknown technology in Taiwan;

- Mackay overcoming distrust through medical achievements, through first treating toothaches and then more serious ailments;

- Courtship and marriage with Mackay’s Taiwanese wife;18

- Physical attacks from local anti-Christians, some of whom are later converted;19

- Death or foreshadowing of death, coupled with statements of love for Taiwan, regret that his work remains unaccomplished, and assurances that his family will continue it.

19 All three plots are constructed as successions of episodes, a feature that critics of Bible Man (by far the most frequently reviewed production) cited as a central failing. For any one of these pieces, it would be fair to remark that “one can only have characters on stage extolling the glories of God, the virtues of Mackay and the natural beauty of Taiwan for so long before someone has to do something” (Smith). Similarly, the lack of character defects of Mackay, his family, or his associates in any of the three stories limits the dramatic possibilities, and often reduces his opponents to caricatures of benightedness or tyranny. In all three pieces, the ideological necessity of hagiographic treatment trumps dramatic or historic concerns. Mackay, motivated by his love for Taiwan and its people, performs the Christian narrative of overcoming persecution and benightedness, before dying with a certain hope of heaven, surrounded by the family members who will continue his good works.

20 The embrace of the West is not sufficient for the purposes of the narrative—in these productions Mackay actually acquires Taiwaneseness. The use of “son-in-law” in the title of the gezaixi narrative is one way of moving Mackay from friendship into kinship,20 but going even further is the final scene of Mackay in Formosa, when an ailing Mackay and his wife relax together and contemplate his life’s work:

Mackay: No, no, not yours, our Formosa.

Zhang: You’re right, our Formosa.

In this show, as in the other two, Mackay calls himself Taiwanese, so that Western recognition taken to its extreme is transformed into actual identification. At the same time, titles such as Black-Bearded Bible Man stress rather than erase racial difference; Mackay’s love for Taiwan is stageworthy specifically because as a visible foreigner his allegiance is exceptional. This has the effect of fortifying Taiwanese consciousness in the audience: if even a foreigner loves Taiwan and has fought so hard for Taiwan, how much greater ought to be the commitment of native-born Taiwanese? Or, if even “an adopted Canadian native son” (Scott 94) can commit to an autonomous Taiwanese consciousness, how can Taiwanese viewers fail to do so? Llyn Scott’s contention that Bible Man’s nature imagery might turn Mackay into a “Taiwanese animistic deity” (107) may be an overstatement, but that this interpretation is at all feasible shows how evident the “Taiwanese consciousness” of these Mackay treatments has been to observers.

21 If the text and subtext of the narrative provide ample evidence for the sociopolitical purpose of Mackay productions, the genesis and production materials of each demonstrate how sociopolitical symbolism is the principal motivation for staging Mackay. In the next section, I will examine each show in turn.

Great Wave

22 Great Wave originated in 2012 as a small, ten-minute production, commissioned by the Mackay Memorial Hospital for private performance on site. Performers were student members of the gezaixi department of the National Taiwan College of the Performing Arts (NTCPA), Taiwan’s principal institution for actor training in xiqu (“Chinese opera”); the creative staff was largely faculty.21

23 This sketch was subsequently transformed into a full-length play for performance on outdoor stages in Tamsui’s Mackay days in 2013 and in Taipei’s “old town” (and more Taiwanese-speaking) quarter of Dadaocheng (2014). Also in 2014, the production was invited to participate in Changhua’s Traditional Music and Theatre Festival. Positive feedback surrounding these simpler outdoor productions motivated the Hospital to commission the full-length indoor-theatre version, which premiered in 2014 and toured six venues in Taiwan for twelve performances in 2015.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

24 Gezaixi has long been regarded as a theatre embodying “Taiwaneseness,” a claim founded ultimately on its history and ongoing practice as a temple performance art, and the further association between Taiwanese culture and local temples.22 For this reason, the Christian Mackay narrative did not strike everyone as a natural fit. At the Lotong performance, the co-producer of the show remarked to me that she thought the Hospital had perhaps been initially reluctant to use gezaixi as a vehicle for its messages, since the genre is associated in the public mind with Buddhism and Taoism. Indeed, the use of any genre of xiqu to promote Christianity is highly unusual and points to the thorough indigenization of Taiwanese Presbyterianism. From the perspective of the NTCPA’s president, Jui-pin Chang, the production, with its novel subject matter, constituted a welcome “infusion of new blood for traditional xiqu” (Great Wave 9). In the event program, the Mackay Memorial Hospital superintendent Dr. Yang Yu-cheng remarked that gezaixi was “indigenous” and “the closest to the hearts of Taiwanese people” and therefore it was “no wonder” that he “keeps hearing that Christians and non-Christians are deeply moved and have learned the tidings of the gospel through Mackay’s story” (Great Wave 5). Yang’s comments show how dramatizing the Mackay narrative was intended as a vehicle to attract more Taiwanese to Christianity as well as to underline its legitimacy as a national religion and a bearer of Taiwanese consciousness.

25 To further rationalise the cooperation between Mackay Memorial Hospital and the gezaixi troupe, hospital officials quoted in Christian newspapers and writing in the performance program made an effort to substantiate a connection between Mackay and gezaixi. Several such sources repeat an account by which the historical Mackay, happening upon a gezaixi performance,

Given that any such gezaixi performance would have had ritual aspects and likely a temple venue, and Mackay’s abhorrence of the “dark, damning nightmare” and “demonolatry” (G. Mackay 125) of Chinese religions, the story is likely apocryphal, not to mention that the emergence of gezaixi itself is usually dated to the 1920s (B. Chang 112). However, the insertion of this anecdote in the context of a performance program is a good example of how Presbyterian officials aimed to legitimate gezaixi as a medium for telling the Mackay story.

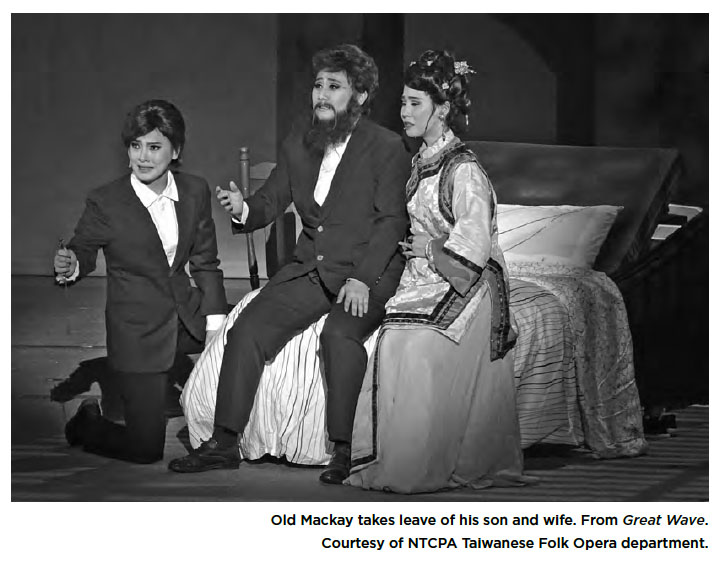

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

26 Of the three productions under consideration, Great Wave was the only one I saw in person, on March 28, 2015 in Lotong Township of Ilan County. This event was evidently a church affair, and most tickets had been distributed through the local congregation. Several Presbyterian ministers in clerical shirts and collars were present, chatting to members of their congregation before the show and in the break, as were Mackay Memorial Hospital officials and volunteers who had made the trip from Taipei for the occasion. Before the performance, the chairman of the board of directors of Mackay Medical College and the Lotong mayor were introduced by the student actress playing the first aboriginal convert. The Canadian Trade Office in Taipei had also contributed reproductions of pictures from the Mackay Room exhibit and a message in the program from Kathleen Mackay. Mackay Memorial Hospital publications, including a translation of Mackay’s diary, and a comic-book version of his life, were for sale in the lobby, as were T-shirts with his image printed in the alphabetical orthography of Taiwanese known as Church Romanization, a writing system closely associated with Taiwan nationalism.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

27 The choice of genre, as much as the choice of narrative material, carries sociopolitical messages. For the Presbyterian church and hospital officials who commissioned the play, the weight of gezaixi as a marker of Taiwaneseness outstripped its once-fundamental association with non-Christian religions, and also caused them to subscribe to a substantially rewritten history.23 Furthermore, casting Taiwanese actors as young Mackay, old Mackay, his son, and another missionary, visibly embodies the desired foreign embrace of Taiwan and the adoption of Taiwanese nationality.

Mackay in Formosa

28 Cultural heritage researcher Louise Aragon has argued that “intangible cultural expressions are re-scripted as national intellectual and cultural property in postcolonial nations such as Indonesia,” a statement which includes wayang puppetry as one of its central elements of intangible culture (269). Her observation is equally true of Taiwanese puppetry, which was “chosen as the most representative symbol of Taiwan in a national opinion poll” organized by the Taiwanese government (Ruizendaal 13). The inscription of a grassroots genre into a national project shows the ideological burden of Mackay glove puppetry productions. My contention that the Mackay narrative specifically has been used as a vehicle in glove puppetry to promote Taiwanese consciousness can be substantiated through narrative, discursive, musical, and linguistic evidence.

29 The Taiwanese-language glove puppet theatre known as budaixi (or, using Taiwanese pronunciation, potehi) is performed in various Hokkien-speaking regions, including Taiwan. Very popular in the earliest twentieth century, it has undergone substantial adaptation over the last half century. Considered “an expression of Taiwanese grassroots culture” (Ruizendaal 13), budaixi is now “intertwined with the ‘Taiwanese’ movement, which advocates an increased awareness and promotion of Taiwanese language, popular culture, and folk religion” (Wu 100), while in popular culture, the television version called Pili budaixi is considered an “icon of indigenous Taiwanese culture” (Hsieh 202). Several budaixi troupes have found it appropriate to use Mackay to promote Taiwanese consciousness. At least one of these is a Taiwanese student association abroad, which shows how Mackay can be deployed as a symbol of Taiwaneseness in the West as well as domestically.24

30 The best-known Mackay budaixi narrative is a ninety-minute show called Mackay in Formosa, produced in 2006 by Lim Chun-iok, a Boston-based Taiwanese Presbyterian well known for his advocacy of Taiwanese language in written and spoken forms. Having toured American Taiwanese associations with his own specially-formed Yam Garden Troupe (Fanshu yuan), using his own script, he engaged I Wan Jan, one of Taiwan’s best-known groups of budaixi, founded in 1933 by patriarch Lee Tien-lu (1910-98) and at that time managed by his son Lee Chuan-tsan. The show was filmed by the Pili International Multimedia (the corporate entity which produces the abovementioned television puppetry), with one of Lee Tienlu’s last disciples acting as puppeteer. It could thus boast considerable budaixi pedigree, although the subject matter was as unusual for the puppets as it was for gezaixi. A journal report suggests that the production has met with considerable success: 5000 DVDs were sold in the first two weeks, and the recording was broadcast on television; by 2009, 23,500 DVDs had been sold or distributed (Zhu 78).

31 The agenda of the production was upfront. One Taiwanese-American Mackay enthusiast remarked that the puppet performance “promoted Taiwanese language and literature, helped developed Taiwanese local culture, blazed a new trail for traditional budaixi and fervently proselytized” (Zhu 77). Such an interpretation is readily sustained through material on the DVD’s “Preface,” consisting essentially of an extended interview with Lim about the genesis of the show. Lim, who has spoken in academic settings about “Taiwanese language and budaixi” as well as issues in Taiwanese-language computer input and dictionary projects involving Taiwanese and Hakka, resolved to create a Mackay budaixi narrative because “one might well use budaixi, which is relaxing and funny, beloved by young and old, to make people fall naturally in love with the Taiwanese language. Education through entertainment.”25 By promoting the story of “How much [Mackay] love[d] Taiwan and how much he identified with the Taiwanese” Lim was hopeful that “the audience will feel how much love Jesus Christ has for Taiwanese through Dr. Mackay’s love for the land and its people. Above all Taiwanese will identify as Taiwanese and love this country, Taiwan, our motherland” (Majie). There can be little doubt that when Lim refers to “education” he is referring to the inculcation of a Taiwanese consciousness.

32 Relative to the other Mackay production, Mackay in Formosa’s use of linguistic tactics to disseminate its nationalistic agenda is especially prominent. For Lim, Taiwanese consciousness, Taiwanese arts (such as budaixi), Taiwanese Christianity, and Taiwanese language are inextricably linked. In addition to genre choice and narrative, Lim’s Taiwanese consciousness agenda shows clearly in his choice of subtitle settings, of which there were five: English, Japanese, Church Romanization, mixed Church Romanization with Chinese characters, and Hakka. Especially notable is Lim’s exclusion of an option for standard written Chinese, a fact that makes the recording difficult for Mandarin-speakers to comprehend, except perhaps through English.26 In any event, use of any Taiwanese-language written system is limited to a small minority outside the church. Subtitles are thus being used by Lim, a Taiwanese-American, as a deliberate way of promoting a local (two Taiwanese and one Hakka subtitle settings) and global (Japanese and English subtitle settings) Taiwanese consciousness to the exclusion of a Chinese element. The use of entirely Romanized characters (also known as peh-oe-ji) is furthermore particularly associated with Protestant missionaries (Chiung 505), situating Lim’s project at the intersection of religious Taiwanese consciousness with puppetry as an emblem of grassroots culture.

33 The production makes a further connection to other genres of “Taiwaneseness,” for instance through the insertion, in the last scene, of a Western-style choral song “My final home” (Wo zui hou de zhujia) written by well-known Taiwanese-language composer Li Kuiran to a text adapted by Lin Hong-hsin from Mackay’s writings.27 This and other Mackay settings have been especially favored by choirs, such as the Formosa Singers, which demonstrate a distinct bent toward Taiwanese consciousness in their choice of repertoire. However, the use of a Western-idiom choral song in budaixi is in considerable contrast to the usual beiguan-style28 music one might expect from a relatively traditional Taiwanese puppet theatre company such as I Wan Jan, and it shows that in this case the emphasis on Taiwanese consciousness trumps generic convention.

34 At the same time that budaixi projects such as Lim’s operated within a relatively constrained sphere of influence, generating little publicity outside of already-sympathetic circles, another Mackay project was being prepared on an international scale.

Mackay—The Black-Bearded Bible Man

35 Opening in Taiwan’s premier performing arts venue, Taipei’s National Theatre, in November 2008 as a big-budget, high-stakes “flagship production,” Bible Man was widely promoted as “the first large Western opera in Taiwanese and English.”29 Western opera “has always been intimately linked with issues of national identity” and also in Canadian opera history “the centenary of Confederation marked a moment of high English-Canadian nationalism, so it is perhaps not surprising that opera flourished” (Hutcheon and Hutcheon 5). Taiwan does not have a particularly distinguished history of Western-type opera production, and the government’s cultural authorities clearly saw mounting an original Taiwanese opera as a way to put Taiwan on the world opera map while investing in Taiwanese consciousness. This position was articulated by the artistic director of the Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre, Chung-shu Liu, who wrote in the performance program:

36 As the head of the CKSCC, to which the National Theatre then belonged, the producer ex officio was Yu-Chiou Tchen, who remarked that “in this new twenty-first century it’s so important to present a newly-created opera that belongs to Taiwan” (Heixu Majie DVD), and that Mackay “demonstrates the life and soul of Taiwan” (Scott 94). As head of the Council for Cultural Affairs, Tchen was effectively Taiwan’s minister of culture in the first term of Democratic People’s Party president Chen Shui-bian (2000-04), whose policies laid out a program for Taiwanese cultural autonomy, a way of “progress toward the goal of international recognition without taking any direct steps that might incite China to take action against Taiwan” (Bedford and Hwang 15). Her public pronouncements on the show revolved around its ability to express the homeland (yuanxiang) and stylishness (shishang). The production was part of her program to “make Taiwan a ‘brand’ on the international culture market” (Heixu Majie DVD), and an element of the Chen presidency’s attempt to “create a ‘cultural Taiwan,’ breaking away from the KMT creation of ‘Chinese Taiwan’” (Chang Bi-yu, “Constructing” 188).

37 Previous Western-style operas (i.e. in the Western classical musical idiom, rather than xiqu) about Taiwan had seldom been set in Taiwan and never in the Taiwanese language. Nor had they generated substantial interest outside of Taiwan.30 Since the policy goal consisted of combining internationalism with Taiwanese consciousness, Mackay was an obvious choice of subject. As a major product of a national institution, Bible Man received domestic media attention from the beginning, not least on account of its sheer budget (reportedly 10-30 million New Taiwan dollars; Scott 107, Zhou 9) and scale. As the technical director Austin M. C. Wang explained, the scale of European operas they had seen while travelling had previously seemed “unimaginable for Taiwan,” and so the successful execution of this project was deemed all the more important (Heixu Majie DVD). If the narrative material was, as with other Mackay narratives, designed to showcase a Western love for Taiwan, the execution of a grand opera was meant to demonstrate Taiwan’s international cultural can-do and its arrival as a major cultural nation in Western terms.

38 Efforts to position Taiwan as a legitimate national culture on the international scene also extended to the recruitment of foreign professionals, notably German Lukas Hemleb, mostly active in France, and already known to Taiwanese audiences for his collaborations with Han-Tang Yuefu, a Taiwanese music and dance ensemble. On Bible Man, Hemleb was engaged for the direction, set design, and lighting design, while two of the three principal roles were also given to foreigners. Even among Taiwanese artists, preference was given to those with international reputations, such as Chien Wen-pin, a principal conductor at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein, and composer Gordon Chin, a Japan-raised, US-educated Taiwanese Presbyterian.

39 Like Mackay himself, Hemleb could be counted on to voice and enact foreign support for Taiwanese consciousness in interviews and other publicity. At times he states the viewpoint even more directly than Taiwanese cultural bureaucrats, claiming that in this libretto “half-savage yet half-civilized Formosa is transformed into a modern Taiwan, which builds its identity on the best of all its ingredients” (Hemleb, “Birth” 9), and writing elsewhere that as “a small island, facing an empire as big as a continent, with immigrants and other settlers arriving pell-mell, Taiwan has always known how to make its differences compatible, turning them into vitality and wealth of knowledge and culture” (Hemleb, “Qiji” 73).

40 A Taiwanese national agenda was also expressed in linguistic terms, as in Mackay in Formosa. Much was made in the media of the use of Taiwanese, since acceptance of Taiwanese language in formal public sphere settings remains an arena of the cultural wars. Use of Taiwanese occurs in a context of its historical suppression by the KMT as a language of education, entertainment, or public affairs, and its revival post-martial law as a badge of Taiwanese consciousness. The use of Mandarin or Taiwanese in official speeches, political rallies, education, entertainment, and literature is regularly scrutinized by the media. Unsurprisingly, the status of the Taiwanese language rose (though falling short of becoming an official language) after the 2000 defeat of the KMT, causing one Western commentator to call use of the Taiwanese language as “virtually synonymous” with the Chen Presidency’s “tacit independence-from-China stance” and therefore “divisive from the start, as well as rendering the opera unsuitable for export” (Winterton 330). The pairing of Taiwanese language use (a product of Taiwanese consciousness) and the international cast (the product of a desire for international prestige) generated the peculiar circumstance that none of the leading performers—playing Mackay (American baritone Meglioranza31 ), his wife (Taiwanese soprano Chen Meiling, a Mandarin speaker), or Mackay’s chief disciple Yan Qinghua (Korean tenor Seung-Jin Choi)—sang in a language they knew. Furthermore, the libretto was written by Joyce Y. Chiou (Qiu Yuan),32 the executive director of the National Symphony Orchestra and known for her work as an author of Chinese-language accounts of Broadway, who had never before written lyrics in Taiwanese. As a result, the production team must have felt considerable pressure to get the Taiwanese right, which was no doubt one reason why they engaged gezaixi divas Liao Chiung-chih and Tang Mei-yun as linguistic advisors. The choice of Taiwanese, despite the language limitations of the performers, librettist, and director, points beyond doubt to the ideological underpinnings of the production.

41 The only consistent English-language reviewer of Western opera productions in East Asia, Ken Smith of the Financial Times, remarked that Mackay “cast a revealing light on Taiwan today” (Smith). However, his verdict was not the kind of arrival on the international opera scene Tchen and others must have been hoping for. Rather, Smith thought the opera showed that “Taiwan is still trying to find its own particular balance. Why else, long after most western countries have passed through their nationalist phase, would it place so much stock on validation from abroad?” Smith’s lukewarm judgment was echoed by well-known Hong Kong music critic, Chow Fan Fu, who remarked similarly that the piece “lacked direction,” while its most obvious motive was to “construct local culture and strengthen the identity of Taiwanese people” (Zhou 9). It must also be noted that Bible Man never toured. In the view of most observers, in the rush to foreground Taiwaneseness, Taiwanese language, and Taiwanese internationalism, the creative staff failed to give the show a sufficient dramatic arc or musical distinction. It may well be that the state-led directives for the project were too constraining for the creative process to generate a work of artistic conviction, or that “Taiwanese consciousness” was being applied to a genre ill-suited to associated ideological goals.

Conclusion

42 Almost thirty years ago, Filewod made these observations about political theatre in Canada:

At every point, Filewod’s statement could be applied to Taiwan: a history of Japanese (and, some would say, Mainland Chinese) colonialism, its Taiwanese (Hokkien)/ Mandarin language wars, its history of suppression of Taiwanese-language theatre, and its once-heavy support of Mainland-derived forms. The early twenty-first century has seen the sustained development of a distinct Taiwanese consciousness just as economic pressures generated by Mainland China’s ascendance threaten Taiwan’s political independence. One result has been the constant renegotiation of Taiwanese identity in the cultural arena, a process during which theatre has been prominent. Waning governmental support for Jingju and the incorporation of Taiwanese “indigenous” xiqu into funding structures and tours has traced a sea change in the position of “Taiwanese consciousness” on the stage. In the cases examined above, budaixi and gezaixi have been adopted as important signifiers of Taiwaneseness, while Western opera—with its (hoped-for) association with international prestige—has been used to project an image of Taiwanese culture and identity as Western-oriented and modern.

43 Mackay’s historical Taiwanese “credentials”—Taiwanese-speaking, aboriginal-engaged, conceptually unrelated to Mainland China—have made him the perfect historical object with which to perform a foreign recognition of Taiwan. Indeed, in a sense, not only budaixi but all the Mackay productions consist of puppetry or ventriloquism, subjecting a historical figure to anachronistic treatment for contemporary domestic ideological purposes. By performing on stage a Western embrace, recognition, and an allegiance to Taiwan as an autonomous entity, international and indigenous genres of Taiwanese theatre enact a process desirable for, but unlikely anytime soon to be reproduced in, the diplomatic arena.