Articles

An Effigy of Empire:

A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Canadian Imperial Nationalism During the Second Boer War

On October 31, 1899, as a part of undergraduate University of Toronto Halloween celebrations, a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at The Princess of Wales Theatre on King Street West was interrupted by shouts from the gallery calling for the death of “Oom” Paul Kruger, the leader of the South African Republic, who had recently declared war on the British Empire. The student demonstration was not, in itself, seen as objectionable or surprising—a similar interruption by Trinity students at convocation on October 25 was lauded in The Globe as “Patriotic.” What was unusual to the Toronto newspapers that spent the next week decrying the demonstration was the students’ lack of decorum at a Shakespeare performance. In this contribution, Andrew Bretz looks at the tension between how paratextual signifiers such as costuming choices, lighting, and the theatre space itself constructed the Halloween 1899 performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as an imperial text, and how Shakespeare as “high culture” moderated the ways in which individuals could express imperial allegiances. This alignment of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with Canadian and British imperial projects may serve to explain why the students chose a performance of that particular play to enact their patriotic violence, yet the condemnation of the event by the daily newspapers troubles the relationship between imperial identity, partially predicated on a sanitized vision of Shakespeare, and the enacting of violence against the colonized other. For the newspapers, A Midsummer Night’s Dream , as a representation of paternalistic British culture and identity, ultimately could not be reconciled with the bald violence of a jingoistic imperialism.

Le 31 octobre 1899, pendant une fête d’Halloween pour les étudiants de premier cycle à l’Université de Toronto, une représentation du Songe d’une nuit d’été au théâtre Princess of Wales sur la rue King Ouest a été interrompue par des cris venant du balcon, d’où quelqu’un appelait à la mort de « Oom » Paul Kruger, le chef de la République sud-africaine, qui venait de déclarer la guerre à l’Empire britannique. La manifestation étudiante elle-même n’a pas été jugée répréhensible ni même surprenante ; une interruption semblable par des étudiants du collège Trinity lors d’une assemblée le 25 octobre avait été qualifiée par le Globe de « patriotique ». Ce qui sortait de l’ordinaire, selon les journaux de Toronto qui ont consacré la semaine suivante à décrier la manifestation, c’était le manque de décorum des étudiants pendant la représentation d’une pièce de Shakespeare. Dans cet article, Andrew Bretz examine comment des signifiants paratextuels tels que les costumes, l’éclairage et la salle de théâtre elle-même auront construit la représentation du Songe d’une nuit d’été le soir d’Halloween 1899 comme un texte impérial et voit comment la « haute culture » de Shakespeare aura modéré les moyens dont les gens disposaient pour exprimer leurs allégeances impériales. Cet alignement du Songe d’une nuit d’été avec les projets impériaux du Canada et de la Grande-Bretagne pourrait expliquer pourquoi les étudiants auront choisi de donner libre cours à leur violence patriotique lors d’une représentation de cette piècelà en particulier. La condamnation de l’événement par les quotidiens serait venue troubler le rapport entre l’identité impériale, qui repose en partie sur une vision aseptisée de Shakespeare, et le recours à la violence envers l’Autre colonisé. Pour les journaux, il n’était pas possible de concilier le Songe d’une nuit d’été en tant que représentation de la culture et de l’identité d’une Grande-Bretagne paternaliste et la violence brutale d’un impérialisme chauvin.

1 On October 31, 1899, as a part of undergraduate University of Toronto Halloween celebrations, a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at The Princess Theatre on King Street West was interrupted by shouts from the gallery calling for the death of “Oom” Paul Kruger, the leader of the South African Republic, who had recently declared war on the British Empire. Papers tossed from the balconies accompanied the shouts and eventually the students raised and mutilated an effigy of “Oom” Paul himself. The student demonstration was not, in itself, seen as objectionable or surprising in the newspapers of the time—a similar interruption by the students of Trinity College at their October 25 convocation was lauded in The Globe as “patriotic” (“Hung Oom Paul”). Rather, in the week that followed Toronto newspapers decried the demonstration because the students had failed to exhibit proper decorum at a Shakespeare performance. The events surrounding the Halloween performance and disturbance provide insight into Canada’s uncomfortable relationship with its own imperial inheritance and ambitions. Nineteenth-century British ideologies of empire and expansion developed alongside the rising popularity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream following its successful 1840 London revival by Madame Vestris. For British audiences, the play represented the civilized, the imperial, the possibilities of progress and technology (Griffiths 22ff.). In Canada, A Midsummer Night’s Dream was seen as a representation of paternalistic British culture and identity. In this production, two effigies were presented side-by-side—the literal effigy of Paul Kruger, representing a hated imperial enemy, whose destruction revealed the violence at the heart of “civilized” empire; and the performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which was itself an effigy of the very civilization that was supposedly at stake.

2 In his study of performances at the University of Toronto in the early decades of the twentieth century, Robin Whittaker suggests that amateur companies and performances are “commonly dismissed by historians and practice-based scholars alike as sub-par, clumsy, superficial, imitative, hopelessly cliquish, wanting in talent, self-interested to the point of delusion and, therefore, without ‘value’ beyond the circles that practise them” (52). Such a reading, Whittaker argues, privileges the implicitly masculine, civilized, metropolitan professional company over the feminized, colonial, amateur company, even when such a company is composed of masculine imperial subjects in a place like Toronto. Rather than focus on the maturation myth of Canadian theatrical identity, which charts Canada’s “evolution” from amateur to professional theatre over the course of the twentieth century, this article draws on Whittaker’s understanding of Canadian theatre of the period as a “perform[ance of] the nation to itself” at a given historical moment (53). Further, this article seeks to build on Alan Filewod’s observation that “theatre that participates in radical politics tends to refuse the institutionalized theatre’s aesthetics and conventions. Local, unremarked, and artistically invisible, the theatre of political intervention is impossible to trace in any complete way” (5). The riot at the Halloween performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream has been almost completely forgotten, but it illustrates how local performance acts worked both to posit and to position the colonial subject vis-à-vis the empire. In the closing days of the nineteenth century, the lines between nation and empire were particularly blurred, such that theatre was not merely performing national identity, but negotiating the relationship between nation and empire. During the Boer War, when public rhetoric situated the conflict in terms of an existential crisis for the empire, the theatre (and Shakespeare in particular) provided a space for reinforcing national and imperial identities.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Imperial Effigy

3 In Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, Joseph Roach theorizes the effigy as

In this sense, there were two effigies at play in the Halloween production of Dream; two performances occurring side by side, commenting upon one another. On one hand, the literal effigy of “Oom” Paul Kruger served to supply a sacrificial lack, upon which the students of the University of Toronto could enact their community through violence. On the other hand, the conservative, romantic performance aesthetic of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was an effigy of the absent imperial centre, identification with which became increasingly important as Canadian imperial ambitions began to be understood as unique from those of the mother country (Dean 18ff.).

4 The effigy supplies an always-absent original; whether for the purpose of violent sacrifice or for the purpose of votive remembrance, the effigy always points to its own lack. It is through performance that the effigy troubles the borders between presence and absence. The performance of violence, which is often associated with the effigy, is “a performance of waste, the elimination of a monstrous double” yet that very act serves to sustain “the community with the comforting fiction that real borders exist and troubles it with the spectacle of their immolation” (Roach 41). Whereas actual lynchings of the kind commonly practiced in the United States and Canada during the 1890s were violent acts that sustained a white community’s sense of the impermeability of the racial boundaries within a larger national community, the hanging in Toronto of a national and imperial enemy from South Africa reinforced the terms of national and imperial identity and belonging that made one both Canadian and a member of the Empire. The hanging of “Oom” Paul Kruger reinforced the differences between the communities of combatants, which would explain why The Globe had characterized the earlier hanging at a University of Toronto convocation ceremony as “patriotic” (“Hung Oom Paul”). The young men in the crowd at the convocation were, in some cases, the same young men who were about to be called to serve in South Africa. For these men, as for those who watched, the violence of the effigial sacrifice both performed and reinforced imperial difference. 1

5 “Effigy,” however, is also a verb, and it is in this sense that the performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Toronto in the late Victorian period must be understood. The first physical effigy of “Oom” Paul Kruger defined a certain form of vigorous (if not vicious), patriotic (if not chauvinistic), imperial masculinity that revealed the technologies of imperial governance to be predicated upon violence. The second effigy was the production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which was aligned with civilization, moral rectitude, and technological progress/prowess, due to its long production history on the Victorian stage.

6 By 1899, the dominant performance aesthetic surrounding A Midsummer Night’s Dream had ossified around the romantic interpretations that had dominated the stages of London and elsewhere since the mid-1800s. This Victorian aesthetic infantilized and feminized the fairies, paradoxically rendering them as objects of sexual titillation on the one hand and as children on the other. The revival of the play in 1840, starring Madame Vestris, marked the first time the mostly-intact script had been performed on the London stage since the Restoration and it established the play as a synthetic work (Griffiths 24). Vestris’s Dream featured over seventy dancers in gossamer portraying the fairies, lavish choreography, elegant and gorgeous set pieces, and, for the first time, the music of Mendelssohn. Part of the success of Vestris’s production was the emphasis on spectacle and technology in the service of gendering the fairies. The sets were designed by J. R. Planché, the antiquarian who had worked with Charles Kemble on his groundbreaking “archaeological style” for King John in 1823 (Braunmuller 86), and were executed by Thomas Grieve, the scenic artist for Covent Garden Theatre, who had worked extensively with Charles Kean (Foulkes, Performing 13). Vestris herself had been a dancer and a singer prior to her taking on joint managership of the Covent Garden Theatre with her husband Charles James Matthews, thus the balletic and musical aspects of the production have been directly attributed to her. The movement of the female dancers and the technical ingenuity of the designers were subject to especial commendation. The Theatrical Journal critic on 1 May 1841 was particularly impressed by the apparent weightlessness and ethereal nature of the actresses playing the fairies, as they were lifted on newly created flying machines wearing revealing ballet costumes (Griffiths 23).

7 Vestris’s Dream provided a template for subsequent productions of the play, not just in England but elsewhere in Europe. By 1843, Ludwig Tieck had taken up this deeply romantic vision of the play for his Berlin revival, which was clearly influenced by Vestris’s success (Foulkes, Performing 14). By 1856, the actress-manager Laura Keene performed the previously uncommon play in San Francisco (Levine 19). The publication in 1859 of Keene’s arrangement included extensive costuming and setting notes as well as a preface that noted the presence of “the music of Mendelssohn” in the performance (vi). In the same preface, Keene noted her obligations to Charles Kean, who was himself influenced in his representation by Vestris’s production.

8 The longstanding and wide-ranging influence of Madame Vestris’s Dream was felt across the decades and the Atlantic. Charles Phelps’s 1853 production augmented the dream-like qualities of the Vestris production by lowering a blue gauze curtain between the audience and the playing space during the fairy scenes, and deploying directional gas lighting, a recent innovation (Foulkes, “Phelps” 55-60). At least since the 1856 production starring Charles Kean, the mise-en-scène for the play drew from classical Greek models, with an Acropolis visible on stage (Cole 199). In other words, by the late 1800s, a dominant aesthetic governed most if not all productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This aesthetic culminated in the famous 1900 Herbert Beerbohm Tree A Midsummer Night’s Dream extravaganza with live rabbits on the stage. In Canada that same dominant aesthetic became a kind of effigy, as it was transported to a sometimes hostile nation by English and American actors.

9 As early as the first decade of the nineteenth century, Canadian theatre had been derided for its derivative and unprofessional nature, only to be relieved by the occasional professional actor from abroad. One hundred years on, J. M. Middleton, in 1914, famously concluded that “There is no Canadian Drama. It is merely a branch of the American Theatre” (8). This statement was nowhere more true than in the performance of Shakespeare. As John Ripley notes:

Throughout Canada, the local press as well as writers from the United States and Britain considered foreign actors and acting styles superior to local talent. As M. R. Booth notes, the London stage may have been the matrix of creation for the spectacular aesthetic, but “North America and the Empire also saw many splendid productions, for the dominant style of Shakespearean production in the bigger urban theatres and with the large touring companies was everywhere pictorial, historical, and archeological” (58). This attempt at replication of the London aesthetic was often supplied by British actors; for example, Frederick Brown, brother-in-law to Charles Kemble, was brought to Montreal to be leading man specifically because he could emulate his more famous relative so well. The newspapers of the day reported his performances in minute detail, as a remnant of the original experience (Ripley). Throughout this period, local talent was largely dismissed. The English diarist and travelogue writer John Lambert wrote disparagingly of the Canadian theatre during his travels through Quebec:

This attitude towards Canadian performances of Shakespeare predominated throughout the century. True Shakespeare, authentic Shakespeare, could only be performed by actors from abroad, while Canada itself was a desert of both performance talent and audience taste, underscoring Canada’s incomplete British identity. As Middleton, an early Canadian theatre historian, tells it:

Shakespeare was aligned with Canadian theatre’s lack—lack of experience staging this play, lack of experience with Shakespeare, and, ultimately, lack of authentic Britishness, with which Shakespeare was aligned. The performance aesthetics derived from Vestris and Kean were seen as authentically Shakespearean in Canada and thus mimicked throughout the century, especially at moments of imperial anxiety for the nation, yet those same foreign, British Shakespearean aesthetics were subject to a complicated negotiation of identity and taste, as the above quotation suggests. That is, Canadians were not merely passive consumers of a British aesthetic that was imposed from the imperial metropole; Canadians were actively engaged in the negotiation of what Shakespeare meant for Canada. The stakes of this negotiation between Canadian and British identities emerge in the multiple layers of performance at that Halloween theatrical. The student performances, both on and offstage, were an expression of anxiety regarding Canada’s national and imperial identity, as the nation and empire strode off to war.

Canadian Participation in the Imperial Project

10 The Second Boer War erupted at a transitional period in Canadian masculine self-identity as both “Briton” and “Canadian” stood side by side within the cultural imaginary as self-descriptors (Buckner 84ff.). Both Canada’s understanding of itself as a masculine entity, subject to the imperial centre, and Canadian men’s self-understanding as masculine subjects were in a state of flux as the Second Boer War reconfigured the terms of imperial masculinity. For instance, the chapbook Ottawa’s Heroes, produced in 1900 by E. J. Reynolds and Son in Ottawa, which provided “Portraits and Biographies of the Ottawa Volunteers killed in South Africa,” begins with a short introduction that blurs the lines between the two:

The slippage between Canadian identity and British identity is embedded in the grammar of the paragraph itself, but also in the frontispiece to the text, which literally situates the title beneath the Royal Union flag, rather than the Red Ensign. It was by this point traditional to fly the Royal Union flag (sometimes known as the Union Jack) beneath the Red Ensign, if one were to fly both flags at the same time. That this frontispiece eliminates the Red Ensign altogether is suggestive of an elimination of colonial difference and total identification with the imperial project. Any unique Canadian identity was, for the purposes of the war, subsumed under the imperial identity. This identification with the imperial project at the expense of Canadian difference/identity is found in a number of other texts published at the time. For example, Annie Elizabeth Mellish’s Our Boys Under Fire begins with an excerpt from “England’s Answer” by Kipling and a portrait of Queen Victoria.

11 In Canadian magazines and newspapers, the Boers were represented as ungrateful as they rejected the benevolent paternalism of British imperial governance. This representation had its roots in the Boer Great Trek of the 1830s and 1840s. Prior to the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Cape Colony had been administered by the Dutch East India Company and settled by Dutch and German colonists. The tensions between those colonists and local aboriginal groups resulted in a colonial economy that was predicated on land rights (for the grazing of vast cattle herds) and slave or indentured labour. A number of administrative changes followed the permanent British take over of the colony in 1814, including conducting all government business in English, the abolition of slavery, and the negotiation between Boer interests with the local tribes such as the Xhosa. When major British settlement began after the 1820s, many Boers chose to move inland, leaving behind British governance for their own messianic vision of a chosen land to the north. Eventually founding the Orange Free State and the Transvaal or Boer Republic, the Boers were seen by the British as a unique failure in colonial governance. By the 1890s, tensions between the Boer republics and the British Empire were again coming to a head, as the British extended their power north (Judd and Surridge 32ff.).

12 For British colonial subjects, the struggle with the Boer Republic and the Orange Free State was one that raised particular anxieties regarding the boundaries of empire and community. The Boers could be thought of as both indigenous and settler-colonists by the British. As Itala Vivan writes, “the European gaze contemplating Africa in colonial times created stereotypes of immobility and primitivism that ideologically contributed to justify the ‘civilizing mission’” (53), yet this gaze and this mission could not logically be extended to the European descended Boer peoples. The Boers may have been European by descent, but they refused all the “civilizing” power of the British Empire. Indeed, the relationship of the British Empire (especially in Canada and Australia) to European (i.e. non-British, European) colonists had often been marked by “benevolent” paternalism, so long as those colonists recognized the supremacy of British civilization, represented in the Common Law, Parliamentary democracy, and cultural products like Shakespeare (Buckner 83). As the descendants of Europeans who refused to assimilate within a British dominion, the Boers were an existential threat to the Empire in that they troubled the imaginative boundaries that defined the empire. Both civilized and uncivilized, both European and African, the Boers were a locus of imperial anxiety for the imperial subject because they slipped so easily between the boundaries that created and defined communities.

13 In Canada, the anxieties regarding the imperial project that emerged from the Boer War resulted in a surge of popular flag-waving imperial patriotism that contrasted with the reticence of Wilfrid Laurier’s government to respond to British requests for help. Leading up to the conflict, in July 1899 the British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain requested aid from the Governors of Canada and the Australian colonies of New South Wales and Victoria. Laurier, however, refused to spontaneously offer troops to reinforce the colonial army in South Africa as he was “more concerned about current problems with America and the reaction of French-Canadians to involvement in an imperial, rather than a Canadian, dispute” (Judd and Surridge 76). The Militia Department of Laurier’s government, however, began drawing up plans as early as July 1899 for the deployment of troops, if and when hostilities came to pass. As war loomed closer in the late summer and early fall of 1899, Laurier was pressured by the British to release Canadian volunteers, yet seems to have resisted doing so on the grounds that Kruger would eventually back down from his demands. When war broke out in October 1899, Laurier authorized an official expeditionary force, staffed largely by volunteers. As Sir Frederick William Borden, Minister of Militia, would later describe, volunteers were not hard to find: “A much larger force could have been recruited and my chief difficulty was to restrain those who seemed determined to force their services upon one and would scarcely take no for an answer” (qtd. in Judd and Surridge 77).

14 This volunteer spirit can perhaps be traced to the popular rhetoric in newpapers, periodicals, and even official dispatches that posited the war as a threat to the continuation of British imperial power. The war was not figured, however, as merely a fight between an over-poweringly puissant imperial power and a small group of white settlers in Africa. As Phillip Buckner describes:

The battle was often figured as one for the very existence of the empire. The Trinity University Review for October 1899 even posited an existential debt to the British Empire, which had negotiated the interests of the Boers against the aboriginal peoples such as the Zulu and the Xhosa: “The Boers seem to forget that they owe their very existence as a people to the British, as it is not so very long ago that the latter stepped in and saved them from extermination at the hands of the natives” (86).

15 In diplomatic cables between Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary for South Africa, and Alfred, Viscount Milner, Governor of Cape Colony, Chamberlain argued that the stakes of the war were simple: “Our supremacy in South Africa, and our existence as a great power in the world” (qtd. in Maris 318). In the opening phase of the war, between October 1899 and January 1900, Boer victories bore out this vision of the conflict. Cardinal Vaughan, Archbishop of Westminster, wrote an open letter published in The Northwest Review on January 23, 1900, suggesting that the war was primarily one of defense of the Empire:

Of course, Canada itself had (and has) ongoing internal tensions, negotiating its own identity vis-à-vis its own pre-existing, non-British, French-European colonists who rejected major aspects of British civilization. This is perhaps one of the reasons why Canadians participated so willingly and passionately in an imperial war that ostensibly had little or nothing to do with Canada. The war allowed Canada to assert its own national identity, with unique imperial goals, separate from those of Britain.

16 The performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream from Halloween 1899 shows that Canada was not merely a country divided along ethnic, religious, and national lines—for that has been long established—but that even within an audience of patriotic British imperial subjects who were working to establish and police an imperial community of identity, the meaning of empire was subject to debate. For some in the crowd that night, imperial identity meant ventriloquizing the aesthetics of the London stage, rendering Canada forever subject to the imperial centre. For others, imperial identity was predicated on unsophisticated, adolescent violence and bald jingoism.

Performances of Empire

17 Very few records survive of productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Canada during the late 1800s. In October 1888, the correspondent for German culture reported in the Dominion Illustrated that from 1881-7, German and Austrian troupes performed A Midsummer Night’s Dream 330 times (“Red and Blue Pencils”), and the article infers that a similar popularity of the play should be expected in Canada. By contrast, The Globe and Mail in 1904 stated that the play “has been but rarely performed” (“Music and the Drama”). The discrepancy between the number of productions suggested by the Dominion Illustrated and The Globe can perhaps be traced to what kind of performance each was talking about: amateur versus professional. 2 It is only in the mid- to late-1880s that records of public professional performances start to appear in newspapers and journals (Bretz xxii); this is a suggestive date, given the westward and northward turn in the Canadian political project in that same period.

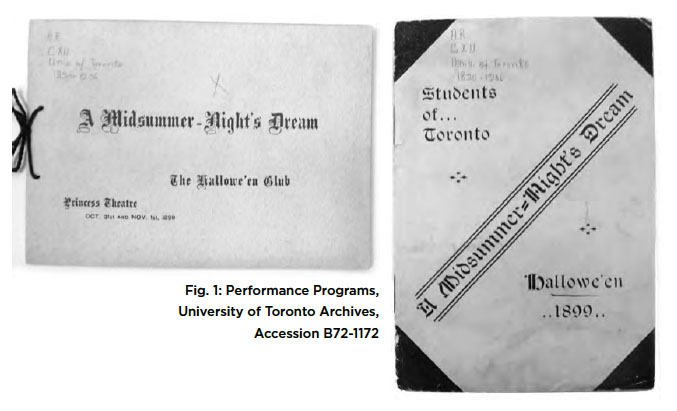

18 Though students put on the production of Dream on Halloween night 1899 as a part of a student celebration (and the production can therefore be understood as “amateur”), both student and national newspapers treated it as a semi-professional production. Indeed, its location at the Princess Theatre, Toronto’s largest and most prestigious theatre in the late 1800s, suggests that the production achieved an impressive level of professionalism. Incidentally, though there is some newspaper evidence of Toronto productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream between 1888 and 1899, these are limited to passing references. Players in opera or other Shakespeare plays are mentioned as having played Bottom, for instance, in the past year, yet there are no reviews of the performances. Only the 1899 production sees reviews from most of the major dailies and weeklies.

19 Dream’s professional location and the amount of effort spent on the production stood in stark contrast to the general state of the Canadian theatre industry of the time. As Makaryk notes, the nineteenth century was marked by a “lack of facilities to produce Shakespeare. […] most early theatres were extensions of drinking parlours, with the stage usually upstairs. […] Plays were also produced in hotels, ballrooms and other venues, such as in the rear of a store.” Well into the twentieth century, when Robertson Davies described the conditions of Canadian theatres to an aspiring playwright, Apollo Fishhorn, Canadian theatres were often, literally, little more than the schoolhouse:

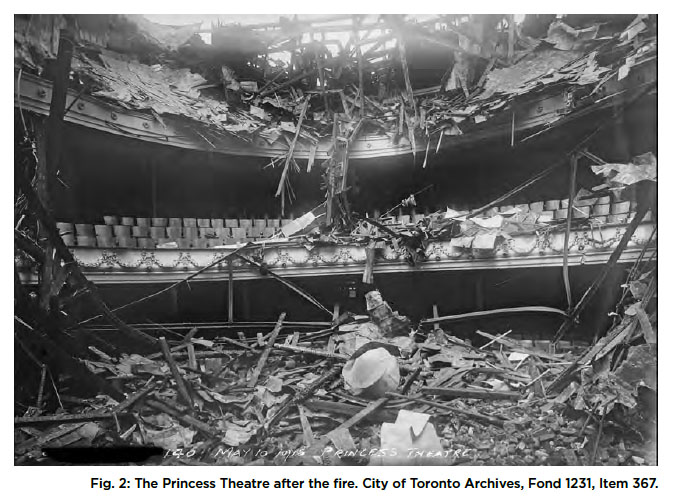

Instead of a schoolhouse, larger centres such as Montreal and Toronto created “opera houses” throughout the nineteenth century, though even these stages were subject to a kind of “Wild West” spirit that lingered long after Confederation (Makaryk). The Princess Theatre was one of these so-called opera houses; a stage fit for the Canadian performances of British stage stars Ellen Terry and Henry Irving. Originally opened in 1890, the building was the first in the city to have electricity alone rather than gas lighting. Although it was opened as the Academy of Music, it soon changed its name and became a part of the circuit of the Theatrical Syndicate, a theatrical booking agency centred in New York City. It had two balconies and a large pit that could seat approximately 1000 people. The only pictures of it that survive are held in the City of Toronto Archives and were taken following its destruction by fire in 1915—even then one can get a sense of its scope as an entertainment venue (see Fig. 2). Immediately before the Halloween production was a short run of the opera Faust by Charles Gounod in rep with Bizet’s Carmen, which points to the theatre’s association with high art and professionalism (“Music and Drama (a)”). Perhaps capitalizing on the new war, the final performance of Faust was given as a “soldier’s night” in honour of the men who were being sent to the Transvaal (“Music and Drama (b)”). Immediately following the Halloween performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was a revival of the Victorian melodrama East Lynne (“Music and Drama (f)”), which points to the theatre’s association with popular melodrama as well as high art. The Princess was a home for high opera, low melodrama, and student Shakespeare all at once.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

20 Leading up to the performance, student newspapers such as College Topics reviewed the preparations for the play, which was the first effort of the Halloween Committee, arguing for the appropriateness of the piece in a manner that hearkened back to a romantic performance tradition that echoed the aesthetics of the London stage: “There is the heroic magnificence of the princely loves of Theseus and his Amazon bride, dazzling with the strangely gorgeous mixture of classical allusion and fable, with the taste, feelings and manners of chivalry” (“Students Play Halloween Night”). The Halloween Committee had been established two years previously with the intent that the inaugural performance would tour across southern Ontario, though there is no evidence that this ever occurred. Indeed, this first production of the committee was primarily a musical extravaganza in the tradition of Madame Vestris, Charles Kean, and Samuel Phelps. The actors were drawn from across the university, from Osgoode Hall to the Medical School, yet the fairies were all to be played by women who were students of the College of Music. A faculty member, Professor Torrington of the College of Music, led the orchestra while a theatre professional, Rory Cummings of the Princess Theatre, handled the special and scenic effects (which had become a hallmark of the London performance aesthetic over the course of the Victorian period). The Halloween committee decorated the auditorium in banners of red and black (“Pharmacy Halloween”) specifically for the Trinity Arts students, whose school colours are still red and black. Faculty sat in the proscenium box, also festooned with the red and black, “as well as the big college Union Jack with the Trinity arms upon it” (“Halloween at the Princess”). The Halloween committee seems to have anticipated that the student audience might be rowdy and granted special permission to the Trinity students to sing “Met’Agona” between acts four and five. 3 “Met’Agona” is a martial song associated with the military and imperial history of the college, as well as the Greek motto on the college’s coat of arms. The song was a victory ode, traditionally sung following the annual steeplechase on the feast day of Saints Simon and Jude, the patron saints of students, on October 28. Though the song is in Greek, additional admonitory Latin verses had been added to the song in the last decade of the nineteenth century by a faculty member, Professor Huntingford, to the effect that “too much spirits intoxicate the freshman” (Reed 244). Given the patriotic fervour of the time, perhaps the singing of the song seemed like an attempt to provide an outlet for patriotic and puerile energies. As The Globe noted on 26 October 1899, the text of the song would be printed in the programs and all were encouraged to participate in entr’acte entertainment, where the song was to be sung between acts four and five (“Music and Drama (d)”).

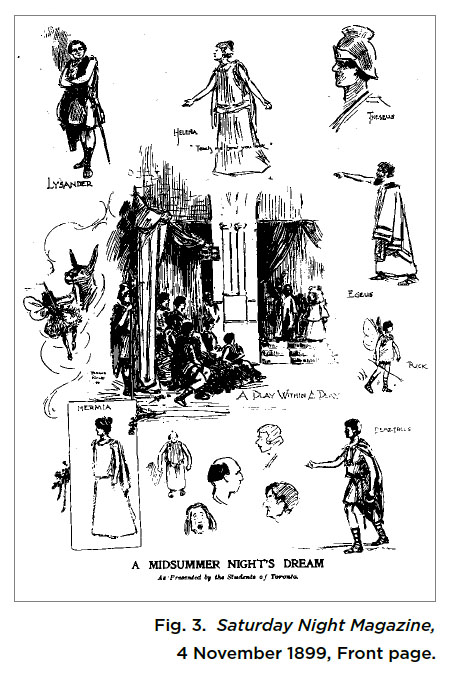

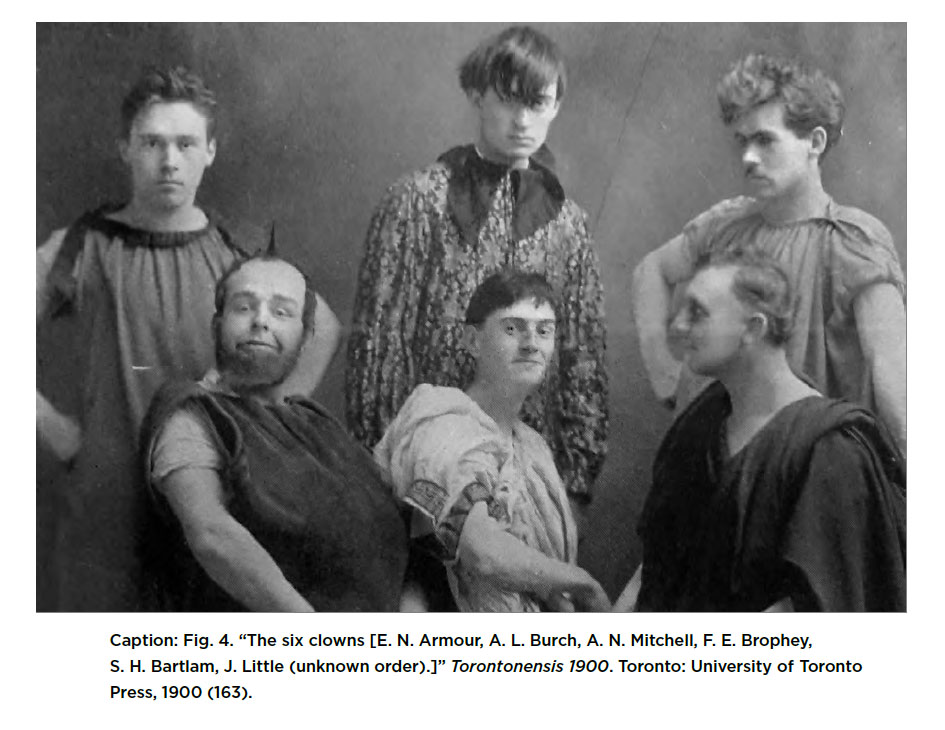

21 The play was universally considered unremarkable in the press. Indeed, it is somewhat difficult to get a sense of what the play looked like because, first, the production offered what had come to be the normative aesthetic model, and, second, the raucous cries of the students dominated accounts in the following weeks. As noted above, the production presented a romantic vision of the play, in keeping with the Victorian performance aesthetic that had been established in London. The costumes and set were Graeco-Roman in orientation, suggesting Kean’s 1856 performance and Laura Keene’s 1859 “arrangement,” which had been explicitly based on Kean’s work. For instance, the image from Saturday Night Magazine shown here, as well as the only surviving photograph of the cast in costume, could be an illustration of Keene’s description of the costumes from decades before:

The same kinds of costume are in evidence, even down to Quince’s brown shirt. The aural nature of the production proudly situated itself in the tradition that had been established by Vestris. The program for the performance notes first that “The whole of MENDELSSOHN’S music will be rendered by a carefully selected orchestra” (7) and only then lists the director, costume designer, choreographers, and properties manager. In another section of the program, the audience was advised that “The curtain does not fall between Acts II and III, or III and IV. The audience is requested to note the beauty of the intermezzo and nocturne rendered by the orchestra during these intervals” (University of Toronto Archives (b)). Even the clockwork wings of the fairies suggested the innovations of Phelps’s 1854 performance.

22 As the Trinity University Review described it:

As such comments suggest, this performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was an effigy, supplying the absent imperial centre. It emulated and mimicked the terms of a performance aesthetic that was developed and created for a completely different theatrical ecology. Though The Princess was one of the few theatres in Canada that could theoretically mimic elements of the London theatrical ecology through its deployment of flying machines, dioramas, complex sets, and other scenic effects, the one thing Toronto didn’t have was a London audience. The performance was, by virtue of its location and aesthetics, always necessarily an effigy of the imperial centre, representing civilization, technological prowess, and English exceptionality. As an effigy, performance works to create a community, to devise and define communal interests. Here, the performance hailed the Canadian audience as members of a larger imperial community, subject to the civilizing force and power of Shakespeare’s language.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

23 As for the real, physical effigy, its presence was felt throughout the performance. The Globe notes on November 1 (“Music and Drama (e)”) that the effigy of Paul Kruger appeared between the first and second acts. The timing of this is suggestive insofar as the program indicates that between these acts “Mr. Edward Clark will sing THE SOLDIERS OF THE QUEEN” with all in attendance asked to join in the choruses (13). The song, not to be confused with the Gilbert and Sullivan song of the same name, is a military march whose lyrics echo the percieved existential threat to the empire:

Our flag is threaten’d east and west; —

Nations that we’ve shaken by the hand

Our bold resources try to test

They thought they found us sleeping, thought us unprepared

Because we have our party wars

But Englishmen unite. (University of Toronto Archives (b))

It was during this song, if in fact the song was performed at all amid the confusion, that the students strung up the effigy of Paul Kruger. The physical effigy was:

Here, the effigy was creating another kind of community, one martial in orientation and tone. The shredding of the effigy is a literalization of what Roach calls “the performance of waste” wherein a “monstrous double” is eliminated to sustain the community with the “comforting fiction that real borders exist and troubles it with the spectacle of their immolation” (41). Whereas the performance of Dream supplied the imperial centre for the colonial audience, hailing them as imperial subjects, the physical effigy of Paul Kruger supplied the enemy of the empire, and through rending his “body” to pieces, the imperial subjects were rendered into one community in opposition to the Boer other.

24 The audience, as might be suspected, was deeply divided. On the one hand, the public, who had paid full price and occupied the orchestra section of the theatre, was receptive to the production’s hailing of them as a certain genus of civilized imperial subject. On the other hand, the students, who had paid reduced prices and were seated in the galleries, were themselves articulating a different kind of imperial subjectivity. A Trinity Arts student defended the actions of the students in College Topics a week later, blaming the perception of chaos on the sullen reactions of the non-student audience in the pit:

The Trinity student represents his brash, almost belligerent, chauvinistic school spirit as not a dual point of focus for those in the audience who “rubbered” or craned their heads around to look at the balcony, because, he insists, “we interrupted no part of the play” (“Trinity Meds”). Instead, the raucous noise and songs during the performance were the fault of “some others” whom he pointedly refuses to name. There seems to be some confusion in the papers as to whether the performance actually ended due to the student interruptions or whether the actors and singers were allowed to finish after the entre’acte singing by the Trinity students (“Halloween at the Princess”). Though the audience was divided, not all students approved of, or shared, the patriotic fervour of the Trinity Arts students that Halloween. Sesame, an annual publication by the “Women Graduates and Undergraduates of University College,” published an article entitled “Sans Teeth, Sans Eyes, Sans Taste, Sans Everything” by “A Lady of Ninety-Five” that negatively alluded to the Halloween performance in the most highly romantic manner. In an essay overladen with poetic imagery drawn from the fairyland of Shakespeare’s play and Victorian poetry such as “Goblin Market,” the author turns to the reader and appealed to the title: “That’s what you’ll be some day, a day far off, when the importance of examinations will be a thing to be smiled over and the walls of old Varsity will be as grey in memory as the mists of Halloween” (49).

25 Following the performance, the students marched up Yonge Street. As they marched, the students pulled fire alarms and when the fire engines arrived the students “jeer[ed] at the firemen” (The Toronto Daily Star) before “the thousands dispersed in all directions” (“Music and Drama (e)”). Along Yonge, at least nine policemen lined up along their route who were “obeying orders” (“Students Play”), yet a search of the Toronto Police Services records for that period shows no official orders given to allow the students to march. Indeed, a number of complaints in the days leading up to Halloween show that the Chief Constable was taking special care to maintain order in the face of rising student vandalism and disturbances of the peace (Toronto Police Services). Though the reporter for The Toronto Daily Star noted that several students were detained by police (four on Yonge and another group of young men at College detained by “Inspector Stephen”), no record of any fracas, detainment, or disturbances related to the students appear in the precinct reports of that night for the whole of the city of Toronto. This complete absence is itself suggestive of a laissez-faire attitude on the part of the police towards the students.

26 The students either recreated the effigy of Kruger or had another one ready when they went into the streets as they eventually set another effigy ablaze in front of the College of Pharmacy near Gerrard Street and reduced it to ashes. The repetition of the destruction of the effigy of Kruger, first in the theatre and then in the streets, suggests a particularly Canadian anxiety regarding the establishment of clear borders between the imperial subject and the colonized other. The University of Toronto students used violence to insist upon their identity with the imperial centre, and in so doing they revealed that the community of empire was only sustained through violence itself. The effigy, after all, is a performance of waste that reveals the tenuous nature of communal governance through its own violence. Following the burning, the students then proceeded north towards Bloor Street, “several ladies’ colleges being serenaded along the way” (“Music and Drama (e)”). In the opinion of the dailies, the fact that the demonstrations petered out at this point could be attributed to the cold weather and late hour (after midnight).

27 The following day, The Toronto Daily Star printed two reviews of the performance. They buried their initial eight-line review of the performance in a list of epigrammatic observations about the war:

The second, longer review was mostly devoted to the actions of the students and only gave cursory notice to the production itself, which was:

For the audience and critics, the meaning of the play had become fixed, taken for granted, so much so that there was nothing to say about it in a review of the production, yet lack of comment is its own critique. For these critics, a production either worked, meaning that it was appropriately spectacular and fairy-centred, with an emphasis on costume and set design that hailed the London aesthetic, or it didn’t work because it would not or could not conform to that aesthetic mode. In this case, the production worked, simply because it suggested the London aesthetic in a semi-amateur, Canadian production, yet in that adherence to the London aesthetic, it meant there was nothing noteworthy to say about the production itself. The spectacle and light romance of the production hailed the imperial centre and thus themselves were aspects of the most salient aspect of the production—the ways in which national/imperial pride was articulated.

Conclusion

28 Perhaps unsurprisingly, the audience’s ambivalence to the events of that night spilled over into the papers’ conclusions regarding the success of the evening. For the Trinity University Review, the evening was something of a failure: “It is most unfortunate for the Halloween club that their enterprise was not as successful financially as in other ways; the idea is a good one and should not be allowed to fall through” (“Halloween at the Princess”). On the other hand, The Globe saw the evening as a financial windfall: “The event was, however, a great success, the theatre being packed to the doors” (“Music and Drama (e)”). Certainly, it would be easy to dismiss the events of that Halloween as merely undergraduates behaving badly, yet to do so would be to ignore the interplay between the two performances of imperial power on display in the Princess Theatre that evening. The performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was an effigy of the empire, establishing a certain vision of the location of the imperial centre and Canada’s relation to that centre. It hailed the audience as a British community, able to consume, if not to create, on their own, the central elements of British civilization. That effigy held open a memorial space in which Canadian identity could blur with the explicitly British past such that the audience could identify with both. The other performances, the hanging in effigy of “Oom” Paul Kruger and the songs, marches, and disturbances that accompanied it, were also creating an imperial community, yet this one was predicated upon violence. Here, in the tattered shreds of the many bodies of Kruger, imperial power was not the emergent property of the morally upright products of British civilization. Instead, imperial power was articulated and instantiated through violence and the policing of national and ethnic boundaries. The two visions of empire, one predicated on the power of literature to conquer, the other predicated on the persuasive nature of violence, were brought face to face. The fact that they could not be resolved shows the flexibility of imperial identity in the late nineteenth century in Canada and perhaps suggests something of the enduring appeal of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Canadian theatre history. 4