Articles

Ryga, Miss Donohue, and Me:

Forty Years of The Ecstasy of Rita Joe in the University

While the seminal role that George Ryga’s 1967 classic, The Ecstasy of Rita Joe , played in igniting the modern Canadian theatre has often been acknowledged, the extent to which its success also constituted a concentrated attack on what Ryga termed the “complacent educator” in 1977, and helped revolutionize the publication and teaching of Canadian plays at the post-secondary level, may have been less well acknowledged. This article, which documents Moira Day’s own forty-year odyssey with the play in the (largely) prairie university classroom as both a student and an instructor, investigates the play’s initial impact on scholarship, publication, curriculum at the post-secondary level, and some of its ramifications on school and university production and actor training over the 1970 and 1980s. It also deals with the challenges of continuing to teach and interpret the play from the 1990s onward, as new practices and theories have continued to alter its meaning, and considers why this odd, iconoclastic text, despite its flaws, continues to fascinate us fifty years after its initial production.

On a souvent souligné le rôle essentiel qu’a joué The Ecstasy of Rita Joe , une pièce qu’a écrite George Ryga en 1967, dans la mouvance du théâtre canadien. Or, on a peut-être moins insisté sur la mesure dans laquelle son succès aura constitué une attaque concentrée sur ce que Ryga appelait en 1977 l’« éducateur complaisant », ni même sur le fait que la pièce aura servi à révolutionner la publication et l’enseignement de la dramaturgie canadienne au niveau post-secondaire. Dans cet article, Moira Day raconte son odyssée avec la pièce de Ryga, dont les débuts remontent à il y a quarante ans dans le milieu universitaire (principalement) des Prairies, d’abord comme étudiante, puis comme professeure. Elle explore ensuite l’impact initial de la pièce sur la recherche, l’édition et les programmes d’enseignement post-secondaires et examine certains de ses effets sur les productions scolaires et universitaires et la formation des comédiens pendant les années 1970 et 1980. Day traite également des défis posés par l’enseignement et l’interprétation de la pièce à partir des années 1990, à mesure que de nouvelles pratiques et théories commencé à en transformer le sens, et se demande pourquoi ce texte étrange et iconoclaste continue, malgré ses défauts, de nous fasciner cinquante ans après avoir été joué pour la première fois.

I

1 Snow, George Ryga once commented, was so central to our physical consciousness as Canadians that we seldom appreciated how our “just learning to live with” the bland white layers impeding our progress also predisposed us to accepting “snow” as an equally immutable reality in the landscape of our evolving national consciousness:

Any hope for the future lay with young people and educators brave enough to force “a reexamination of our history and […] who we are and how we got that way” (Ryga, “Need” 207-08). Sadly, for Ryga, a glacial resistance to change—“the awesome power of the complacent educator” to act as “censor rather than partisan and advocate of a deepening and more complex cultivation of a people for changing times” (209)—was most culpable for a “generation of youth” losing “access to a part of themselves and their land” (209).

2 While the catalytic role that Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe has played in igniting the Canadian theatre has often been acknowledged, its influence as a concentrated attack on Ryga’s “complacent educator” may have been less well noted. The Teacher, as a speaking character, makes only three appearances in the play, all of them brief and in Act One. This article argues that she is nonetheless a deceptively simple or minor character who spearheads much of Ryga’s multi-layered attack on “complacent educators” wherever he found them: at the front of Canadian classrooms on all levels; in the educational hierarchy that trained teachers in a questionable pedagogy to implement a suspect curriculum; in the overarching government and social structures that supported that hierarchy and relied on it to systemically perpetuate the necessary, agenda-driven “snow jobs” on their behalf. Nor did Ryga spare the publishing, academic, and theatrical institutions he considered complicit in supporting these “complacent educators” who were stripping the young and vulnerable of “part[s] of themselves” (209). In fact, the widespread production, publishing, and teaching of the play itself was arguably Ryga’s best revenge on the system.

3 For many of us who made our careers in the Canadian Theatre primarily as educators rather than practitioners, Rita Joe was a force that also helped revolutionize the Canadian university classroom. Yet, the tempest Rita Joe set blowing in 1967 soon outraced the play itself—and perhaps even us. Wrestling with the changing meaning of Ryga’s compelling, frustrating play within classrooms that were themselves being profoundly changed by new generations of students, and by radical new aesthetic, ideological, and critical revolutions, I ultimately found it impossible to chart my personal odyssey of almost forty years with Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe as a student and educator in the (largely) university classroom without simultaneously returning —again personally, profoundly, and often painfully—to the increasingly complicated question of the relationship between Ryga, Miss Donohue, and me.

4 Collingwood refers to loving something “so much” (334) that we could never conceive of destroying it. In 1967, when Ryga was “[c]rossing and recrossing the vastness of this country, riding, walking and resting beside fools, poets, students and transients in search of tomorrow” (Ryga, “Temporary” 175), I was making my own long cross-country trip from Edmonton to Expo ‘67, the World’s Fair in Montreal. During those summer days in Montreal and even more memorably on the train to and back, my callow 14-year-old self fell slowly and irrevocably in love with my country—with the size of everything it represented or promised to become. How easy it seemed to find oneself simply by touching that wonderfully vast land; to believe that Ryga’s “distinctive mythology” reflecting “a popularly agreed-on interpretation of who we are and how we got that way” (Ryga, “Need” 208) was only a tomorrow away.

5 Little wonder that Ryga felt comfortable appealing to the power and idealism of youth to work miracles. At that time, the age differential separating the rising tide of baby boomers filling the classrooms and the new wave of young teachers and professors arriving to instruct them was often surprisingly thin. But then, as suggested by Rita Joe itself, there was also a terrifyingly thin line between the enormous potential of that “generation of youth” to move mountains, and the terrible vulnerability of its most disadvantaged members; even Rita Joe wishes “I was a teacher” (Ecstasy 64) and agonizes over the crossroads within and outside the classroom where the dream became lost (57, 77-82, 88-90).

6 On the page, the climactic murder and rape scene that leaves both young protagonists brutalized and dead made for almost unbearable reading. That graphic, disturbing image of violence and violation, apparently originally derived from a newspaper report about “a Native girl” left murdered and discarded, like so much disposable trash, near “a garbage-dump area on Cordova Street” (Hoffman 159), was, according to both Innes (29) and Hoffman, very close to the visceral core of the play; right from the earliest drafts, Ryga’s “Indian woman” protagonist (Ryga, qtd. in Hoffman 166) was either already dead or living the last minutes of her life as an “odyssey through hell […] in search of her name, her identity” (Ryga, qtd. in Innes 31).

7 However, if Ryga began his process with the documentary reality of a female aboriginal corpse on Cordova Street, he only chose to return to the physical reality of that body on the stage at the end of the play, and within the context of a flowing, expressionistic dramaturgy that presented the rape and murders largely as the metaphoric culmination of a far more damaging, insidious, and systemic process of physical, mental, spiritual, socio-economic, legal, and educational violation and destruction aimed at exploiting the young, the disadvantaged, and the marginal wherever they were found.

8 Those of us looking for a larger binding parable in the play found it quickly enough in a Cold War world, where the best interests of many small, impoverished, emerging nations were defined more by the political, military, and industrial imperatives of the Great Powers than by the compelling needs of the little people traditionally living close to the land. In that regard, Ryga asserted, there were many Rita Joes “in the Congo, Bolivia, Vietnam” (Ryga, qtd. in Hoffman 181). Ryga also explicitly tied his criticism of Canadian policies towards its Indigenous peoples at home to a condemnation of Canadian imperialism in Brazil; more specifically, he accused “the Canadian-based multi-national corporation, Brascan” of practicing “racial genocide” against “the Indians of the Amazon basin, a race of people who once numbered over 3,000,000 and have now been decimated to less than 80,000” (Ryga, “Theatre” 338).

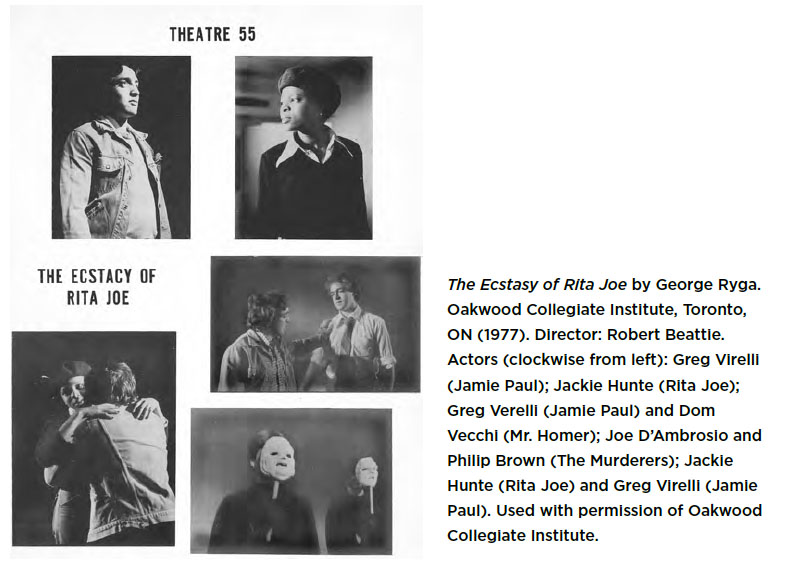

9 Closer to home, the young could see a microcosm of the same iconography of repression and revolt in the plight of the dispossessed young protagonists adrift in a hostile, violent world of rigid, irrelevant, or hypocritical white authority figures. Theatre scholar Aida Jordão, who served as assistant director on her Grade 13 production of Rita Joe in 1977-78, remembers the racially diverse production as a highlight of her Toronto high school years:

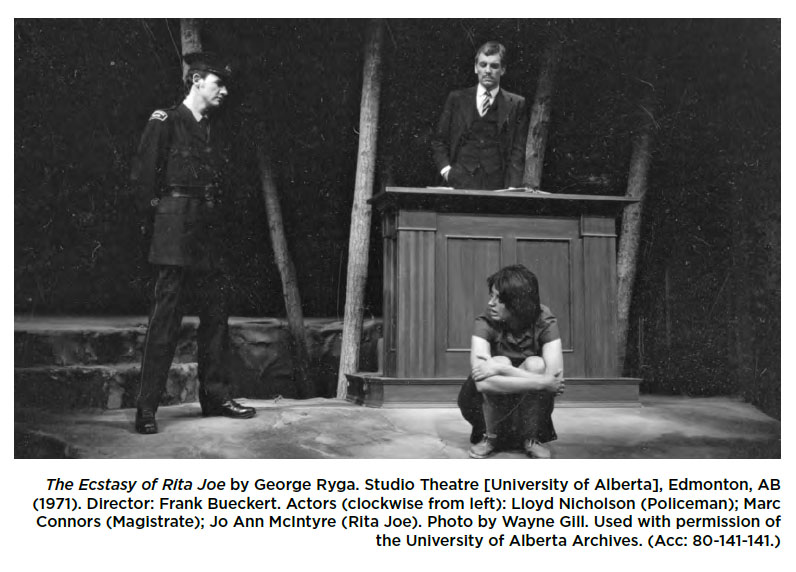

Riding the same tide of social and youthful protest at the university level, Edmonton’s first production of Rita Joe memorably opened the University of Alberta’s 1971-72 Studio Theatre season in the middle of a rapidly escalating provincial campaign of school boycotts that by mid-October had seen at least 1,600 aboriginal children withdrawn from reserve schools in Northeastern Alberta by the chiefs at Cold Lake, Kehewin, and Saddle Lake (“1,087” 1). On the same day that the Edmonton Journal review appeared, the paper again reported that “[t]he Indians are adamant that the reserve schools” include the “teaching of the Indian languages, and Canadian history shedding light upon the Indian people’s true role, to assure the resurgence and permanence of Indian culture in Canadian life” (“50” 3). Further, a University of Alberta “teach-in to enlighten students on provincial Indian problems,” held on the production’s opening day, had “developed into a verbal free-for-all” (“Indian” 33).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

10 As “complacent educators” on all levels scrambled for cover, Journal reviewer Barry Westgate commented wryly that Ryga’s play “has merely reminded us of a few things” we’ve all known for years: “in this case the Indian problem in Canada.” Nonetheless, mostly because of the production’s “terse and effective ensemble,” strong action choreography, and the utter “zeal and ardor” of the two leads, Jo Ann McIntyre and Allan Strachan, in characterizing the futility, frustration, and “hopeless antagonism” of being young and “caught in a social morass from which there seems to be no escape,” Westgate concluded that the young cast had so successfully “engender[ed] the kind of emotion, both present and implied in the script,” that Ryga himself would “very readily” admit that the production rang “very truly of the drama he created” (63).

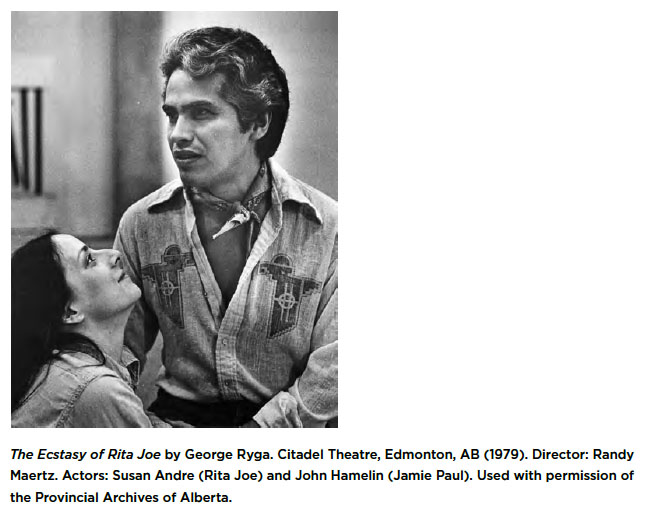

II

11 If Ryga saw youth rising as one pole of the coming revolution, he saw a new generation of educators as the other. For many of us entering university in the 1970s, the Ryga “villain” we loved to hate was Miss Donohue: “a shy, inadequate woman who moves and behaves jerkily, the product of an incomplete education and misplaced geography” (Ryga, Ecstasy 78), she attempts to drill, with growing frustration and shrillness, the lines of a Medieval Persian poet, in a questionable translation by a Victorian man-of-letters, into the heads of her bored, polyglot, twentieth-century Canadian class.

12 While Ryga knew “Miss Donohue” better than we did, his observation that the literary landscape within the Canadian classroom was often curiously disconnected from the geographical landscape outside was still surprisingly true even in my time.2 Margery Fee suggests the first Canadian Literature course taught at a postsecondary institution in Canada (and possibly, the world) was offered at the Macdonald Institute of the Ontario Agricultural College (now Guelph) in 1907, becoming a regular course in 1910 (20-21). At universities proper, however, full, regularly taught Canadian Literature courses did not become standard until after World War II (20-21).3 Starting with New Brunswick and Saskatchewan (1945-46), the movement gained momentum over the 1950s and 1960s (20-21). By the time I became an English major at the University of Alberta in the early 1970s, there were nine distinct Canadian Literature courses running from the first-year through to the graduate level, and by the mid-1970s additional half courses in Western Canadian Literature were being offered at the Universities of Alberta (1976-77) and Saskatchewan (1973-74).4

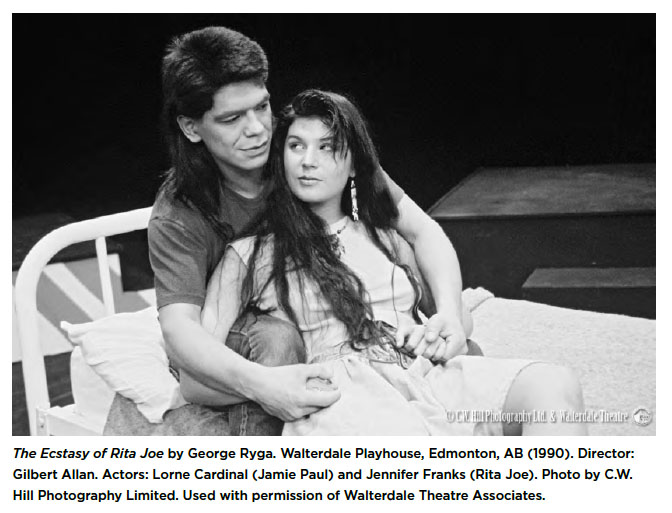

13 However, if Canadian Literature had taken big steps towards decolonizing itself from British, Commonwealth, and North American Literature by the time Ryga’s Miss Donohue appeared in Rita Joe, the same could not be said for Canadian Drama in the classroom. Ironically, it would have been nearly impossible for either Rita Joe or “The Teacher” to study, let alone teach, anything resembling the play they themselves were in. Drama was confined to examining Shakespeare and Modern (British, American, and European) Drama, and even Canadian Literature, with few exceptions, meant studying novels, short stories, and poetry. 5

14 Again, even in this regard Rita Joe was a game changer in a way that has not always been acknowledged. The play’s meteoric rise to national and arguably international consciousness not only opened doors to other English-Canadian plays being produced professionally, but to being published, read, and taught at a rate that would have been inconceivable even a decade earlier. The play also helped open a previously closed door in Quebec, argues Louise Ladouceur, to English-Canadian plays being translated, performed, and published in French.6

15 To teach a course one needed texts, and publishers committed to a sustained publishing of dramatic texts. Significantly, in 1970, Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe became only the second of an increasing stream of Canadian play texts issued by the newly-founded Talonbooks; other new, drama-friendly national and regional presses like Playwrights Co-op (now PLCN), NeWest, Cotteau, and Blizzard soon followed. The next classroom-friendly step was affordable anthologies, and Ryga again led the way. His one-act, Indian, which had already been anthologized no less than eight times between 1966 and 1975 (Hoffman 326), reached another milestone in 1984 by being included in Richard Plant’s Modern Canadian Drama anthology, while The Ecstasy of Rita Joe reached virtual publishing immortality for the university classroom with its inclusion in Jerry Wasserman’s Modern Canadian Plays, volume one, in 1985 and in all of its subsequent editions.

16 With texts came courses. Building on the momentum of the Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama (Toronto), founded in 1966 as the first institution in Canada to offer a drama Ph.D., Ann Saddlemyer recalls that she offered the first half course in Canadian Theatre at Victoria College, University of Toronto in 1972, and a graduate level course the year after, while Mavor Moore offered a course at York about the same time. The same revolution in Drama had also swept the University of Alberta by the time I became a graduate student in the mid-1970s. Two years after its own electrifying production of Rita Joe, Drama instituted Canadian Theatre classes at both the undergraduate and graduate levels; by the time I’d graduated with my master’s degree (1979-1980), two new undergraduate courses in Canadian Drama had been introduced respectively in both Drama and English.

17 A field almost non-existent when I first entered university now beckoned alluringly at the graduate level. “Training,” Ross Stuart noted in 1975, “is particularly vital in the area of Canadian theatre history because it is a young person’s field. Few of our more mature scholars have become involved in it, so the work of the young researchers must be taken very seriously” (14). Music indeed to the ears of a young scholar! And Ryga and Rita Joe were there every step of the way. I first read Rita Joe and Indian in the context of James DeFelice’s graduate level Research into Canadian Drama class at the University of Alberta, where we huddled excitedly over the seminar table with our small collection of published Canadian plays. We reviewed a 1979 production of Rita Joe at the Citadel Theatre as part of my Play Reviewing class with Frank Bueckert, the director of the 1971 university production. I even glimpsed Ryga himself when he returned to Edmonton for rehearsals of Seven Hours to Sundown, a play commissioned by Theatre Network and the University of Alberta in 1976. What a wonderful reminder that he was not just Canada’s George Ryga, but Alberta’s George Ryga, even Edmonton’s George Ryga. At the University of Toronto, Rita Joe returned again when I took Ann Saddlemyer’s Graduate level class in Canadian Theatre over 1981-82, and penultimately as part of my Ph.D. comprehensive exams.

18 It was a heady journey. A generation of us who came of age in the new discipline by the mid-1980s may have remained intimidated by most of the horrendous issues identified in Rita Joe, but there was one problem we felt eminently well-qualified now to solve personally: “Miss Donohue,” that worst of complacent educators, was out—and we were in.

III

19 My career as a university educator began as a sessional lecturer first in the Department of English (1983-85), and then in the Department of Drama (1984-91) at the University of Alberta, and then as a full-time faculty member in the Department of Drama at the University of Saskatchewan (1991-present). Ryga and Rita Joe continued to be companions along that journey, but neither remained the bright avatars of progress they had seemed in 1967. Neither were we: there were now disconcerting moments when we looked at Miss Donohue and saw our own eyes staring back at us. Privately, I wondered when the obnoxious whine of her voice had begun to surface in mine: “What is a noun?” “Did you hear what I asked?” “There’s a lot you don’t know.” “Try to remember.” “You are straying off the topic!” (a common one on term papers). And in my worst moments, though I pray I never actually said it out loud: “Arguing … always trying to upset me” (Ryga, Ecstasy 78-81).

20 Change, Collingwood suggests, should ideally work out of a holistic sense of balance and dispassion if it is to be true progress. In practice, he suggests, the temptation is strong to make a virtue of complacency and to effect no real change at all because we are so comfortable with, or at least tolerant of, what is already in place. Consequently, the momentum for revolution is often driven instead by those with enough hatred or intolerance for the existing system to justify its razing (334). Rita Joe itself made much of its initial impact by its uncompromising attack on the status quo. But it soon became grist to the same mills of change that it had initiated. motives, as white actors and a white director, for putting on a play written by a white playwright to tell a story that should properly be written, performed, and produced by indigenous peoples themselves. The company could say little in response except that they agreed in principle, but Rita Joe and themselves was essentially what they had to work with in 1971.7 Nonetheless, an awareness that artistic and personal integrity was all the ground they had to stand on did put pressure on the young cast to, as far as possible, get it right and to “thoroughly mak[e] themselves […] in mien and dialect and appearance” and characterization (Westgate 63) into as accurate an embodiment of indigenous “street-level Canada” as they could.

21 Nonetheless, a catch-22 had been identified that was beyond the capability of any one student actor, however talented, to solve. School and university drama programs have different priorities than the professional theatre; rightly so, the casting for their own productions is dictated first by the training and educational needs of their students. However, if aboriginal students remained absent from the classrooms of the newly founded university conservatory programs that were meant to train the rising generation of professionals to fill the new Canadian theatre, then the cycle of exclusion became self-perpetuating. As for the play itself, University of Alberta professor emeritus, playwright, and director Jim DeFelice comments that the enormous euphoria that had met Rita Joe upon its initial success had given way to a more critical period of questioning, especially on matters of cultural appropriation, by the time he began teaching the play at the University of Alberta in the mid-1970s. Both issues were to problematize the remaining productions in Edmonton in 1979 and 1990.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

22 Knowing what the alchemy of the original cast had done for the 1967 production, I very much looked forward, with the rest of my graduate-level play-reviewing class, to seeing what the full resources of the professional theatre could bring to the play. Unfortunately, the 1979 production of Rita Joe at the Citadel Theatre, despite its attempts at interracial casting, simply stoked the growing fires of doubt about the play’s long-term viability. Kudos were bestowed on many of the actors (with Ashwell particularly praising Tanya Ryga, Ryga’s daughter, as “The Singer,” and American Nez Perce actor John Kauffman as “David Joe”), but both mainstream media reviewers struggled with the play itself. Ashwell felt that the enfant terrible of 1967 had entered a state of “uninteresting adolescence” by 1979. While he hoped it might yet mature into a “contemporary classic” (C5), Edmonton Sun reviewer Dave Billington was more doubtful, suggesting that while “[Ryga’s] emotions are correct and his intellectual understanding of the terrible cultural conflict is acute” the fact that he was not indigenous himself meant that he “puts words in the mouths of his Indian characters, and stimulates emotional responses which are, at best, dubious and at worst downright specious” (17).

23 Still, he conceded, “Ryga’s passion is so great that something could have been salvaged from the work” if director Randy Maertz had not made the “catastrophic” decision to cast white actors John Hamelin and Susan Andre as Jamie Paul and Rita Joe (Billington 17). Ashwell concurred: not only did the leads come off as gratingly inauthentic in comparison to the aboriginal cast, but the disjunction reinforced the places in the text where Ryga’s “Indians” themselves sometimes came uncomfortably close to being white characters in brown face: “The renegade Indian, the Indian who won’t be tamed, is for the most part a white man playing an Indian” (C5).

24 Maertz, who had acted the role of “The Priest” in the 1971 Studio Theatre production, felt that as a director he too had been caught in a catch-22 situation not entirely of his making. He had chosen the play, at least in part, because of its opportunities for local indigenous actors to either make their professional debut [as Jamie Paul’s friends] or first professional appearance [as Eileen Joe] on the Citadel mainstage. Nonetheless, he claimed to have found very few Canadian indigenous actors of either gender to audition, and none whom he felt had the experience, training, or presence to “command the space” and carry the demanding lead roles on the imposing Shoctor Theatre stage. Nor, with the exception of the crucial David Joe role, had he been willing to pass over capable, local actors for American imports with superior cultural and training credentials (Ashwell, “Director’s” C 12). Nonetheless, as a class, our reviews had a common thread: the casting anomaly seemed all the stranger because the person who should have been cast as Rita Joe was both local and already in the show. Like Ashwell, we felt that “Margo Kane, playing the role of the sister Eileen Joe would have been better cast for the lead role in this production” (C5).8

25 Similar issues arose with the 1990 amateur performance by the Walterdale Playhouse, which had first introduced Edmonton to Ryga in 1967 with his early play Nothing But a Man (Hoffman 149). Opening on virtually the same day that the Mulroney government slashed “9.6 million from the constructive programs created to encourage native self-sufficiency” (“Silencing” A10), the play’s excoriating “indictment of Canadian society for its failure of humanity” was, commented Journal reviewer Liz Nicholls, as “live” now as it was in 1967 (C3). Sun reviewer John Charles agreed: “this story unfolds on the streets of Edmonton every year” and was “nowhere more alive than in Alberta” (36). However, Nicholls continued, the flowing, expressionistic dramaturgy which had been in 1967 “a radical departure for a theatre up to the elbow in the kitchen sink and counting time by the clock” was in danger now of becoming “clichés of another sort,” especially in inexperienced hands (C3). Charles, like Billington, also faulted as “especially disappointing” the production’s inability to catch fire from Ryga’s saving grace of passion and anger—except in one striking regard (36). Like Nicholls, he strongly praised the young Cree actor who, as “Rita’s playful boyfriend,” crackled “with the sheer fury of his defiance and self-mockery” (Nicholls C3) and who was “not only the largest presence on stage in style and spirit, but also add[ed] a badly needed note of integrity” (Charles 36). The actor, a young Lorne Cardinal, was to graduate three years later as the first self-identified aboriginal alumnus of the University of Alberta B.F.A. Acting program.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

26 According to DeFelice, the arrival of the first indigenous students in the B.F.A. acting program did bring a fresh perspective to Rita Joe. They felt Ryga’s representation of life on the reserve reflected more of pastoral idealism than reality, and that he had misunderstood indigenous spirituality. Nonetheless they felt, as actors, that they could in some measure re-appropriate the play by coming up through Ryga’s text and completing, correcting, and filling in the spaces in its structure. The emergence of a new professionally-trained generation of indigenous actors, like Cardinal and Kane (who went on to train at the Grant McEwan College performing arts program in Edmonton), indisputably played a crucial role in revitalizing Ryga’s tough, problematic play onstage over the 1980s.

27 However, this new vitality did not automatically transfer to the academic classroom. Students rushing through the text in a large, general survey course often found Ryga’s lyrical 1970s dreamscape confusing; those preparing to enter the leaner, meaner job market of the late 1980s frequently found his signature didacticism and idealism alienating. For the first time, I began to feel a certain sneaking sympathy for Miss Donohue’s own struggles to teach nineteenth-century English poetry to a class struggling, in turn, to see its relevance to their lives. The argument that “It is good for you to study the classics” only went so far. The argument that the play remained powerful and relevant in production with good casting and direction went somewhat further. However, the performances were not happening in my classroom, the stellar productions I cited were past and far away, and any recent Edmonton ones students might have seen were problematic.

28 Some students regarded the play as being guilty of the same “melting pot” philosophy that Ryga himself ridiculed and condemned. This claim that Rita Joe’s experience had larger universal reverberations because her odyssey as an indigenous woman was also a metaphor for sweeping human oppression at home and abroad led them to ask: was Ryga not also putting “copper and tin into a melting pot” with the purpose of eventually rendering us all down as “people” to a kind of bland liberal humanist “bronze”? (Ryga, Ecstasy 79). A further, major sea-change was indicated by the comment of one student who felt Ryga’s “hippie flower-child” paled in comparison to the powerful and authentic female indigenous voice of Maria Campbell’s memoir, Half-Breed (1973). By the late 1980s, as significant new indigenous dramas, like Tomson Highway’s The Rez Sisters (1986) and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing (1989), became accessible as texts following nationally-acclaimed productions, it became increasingly tempting not to teach Rita Joe at all.

29 In the 1990s, I joined the faculty of the University of Saskatchewan Department of Drama in Saskatoon, and over 1992-93 taught the first formal half-course in Canadian Theatre to be offered by that department. It was a new start for both me and Rita Joe to the extent that the richness of the province’s indigenous artistic, cultural, and academic life readily invited new connections to older material. Not only did Saskatchewan boast some of the earliest Native Studies departments or university colleges in Canada, 9 but my first self-identified indigenous students began to appear at the undergraduate level. Over 1994-95, I taught the play as a module that explored Western Canadian white-indigenous collaborations in the theatre; Rita Joe was taught in conjunction with two Saskatchewan works, the Book of Jessica (by Linda Griffiths and Maria Campbell) and The Calling Lake Community Play (by Rachael Van Fossen and Darrel Wildcat). Over 1997-98, with a new millennium approaching, Rita Joe became part of an even more ambitious, term-length study in my full-year 200-level Modern Theatre course, which compared and contrasted theatrical treatments of the marginalized (children, women, and non-Europeans) mostly in Canada, America, and Britain at the end of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Viewing Ryga within the context of a historical range that included everything from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Belasco’s stage-play, Madame Butterfly, and Charles Mair’s 1886 neo-Shakespearean tragedy Tecumseh at one end of the spectrum, to Tomson Highway, Northern Delights, Native Earth, De-ba-jeh-mu-jig, and Weesageechak Begins to Dance at the other, invited some of the most delightfully original and varied comments on Ryga I have ever received at the undergraduate level. They ranged from the thoughtful:

To the critical:

To the whimsical:

The 1997-98 experience was probably the best undergraduate teaching experience I had with the play, and the larger historical sweep undoubtedly contextualized it better and more kindly. Still, I was discontent with essentially reducing Rita Joe to a single issue, and continuing to dialectically situate it in an evolutionary progression where it was inevitably doomed to fail. I once asked on a quiz: “Ryga’s play has sometimes been condemned as a heavy-handed political tract that reduces the ‘Indian problem’ to a series of stereotyped situations and characters. Do you feel that this is a fair assessment of the play and its effectiveness?” While intended to spark the kind of debate Ryga himself might have valued, the question, to paraphrase Collingwood, eventually struck me as essentially just asking if Ryga was trying to be Tomson Highway and failing. This was about as fair as Ryga’s own trick of reducing Omar Khayyam to fragments of absurdity in Miss Donohue’s classroom to make a valid point about the deficiencies of the system that had produced her. Khayyam deserved better—and so did Ryga. It was to be over a decade before I taught Rita Joe at the undergraduate level again.

IV

30 My journey with Ryga and Rita Joe did not end in 1998. However, I found my teaching at the graduate level probably got me closer to understanding why I remained haunted by Ryga’s comment about official mythologies and “definitions of ourselves which have succeeded in making near strangers of each of us to the other—and by so-called resolutions to these problems which are oftentimes worse than the original problems themselves” (Ryga, “Theatre” 337).

31 In 1990-91, I taught my first graduate level class in Canadian Drama at the University of Alberta: an extraordinarily gifted group of people including Sara Stanley, a visiting director/professor from the University of Lethbridge; Vern Thiessen, a future governor-general’s award-winning playwright and current artistic director of Workshop West Theatre in Edmonton; Kenneth T. Williams, the first indigenous M.F.A. graduate of the Playwriting program, whose work is now well-published and produced across the country; and Shawna Cunningham, a Métis of Cree descent from southern Alberta and current Director of the Native Centre at the University of Calgary. The discussions about all the plays 10 were provocative, but the ones centered on Rita Joe were particularly revealing. Sara Stanley, who directed the successful University of Lethbridge production in 1989, acknowledged Ryga’s shortcomings as a playwright, but nonetheless spoke eloquently of her faith in the play’s continuing power, provided the production arose out of a close collaboration between the local white and indigenous communities. Shawna and Ken, however, voiced deep-rooted concerns with the play itself. Looking back, Ken notes:

Shawna brought an equally penetrating insight to the issue. Whatever their good intentions, she suggested, many non-native playwrights structured their plays in ways that simply opened the wounds and left them bleeding; they didn’t close the circle in a way that allowed for healing. The figure of David Joe, however positively realized on stage, was not enough to balance the fact that the only character onstage that an indigenous woman could identify with went straight down the crapper and never came back.11

32 Who was Ryga actually writing the play for? Why was it structured the way it was? Those questions continued to dog me on the two other occasions that I taught the play as part of special topics graduate courses at the University of Saskatchewan: one, in 2007, surveyed the development of Canadian Theatre from 1606 through to 2007 with a particular emphasis on the evolution of the pastoral and urban vision, and also included an examination of the work of Saskatchewan film-pioneer Evelyn Spice Cherry (1904-1990). The second course, taught in 2005 in the context of an Interdisciplinary M.A. program involving Drama, History, and Native Studies, was even more germane to the issue. Entitled “North American Theatrical and Dramatic Representations of ‘The Other’: 1606-2005,” the course saw myself and student Alan Long reading over forty plays, some British and American, but mostly Canadian, that looked at how white-European playwrights constructed women and non-Europeans on the stage during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—and how women and non-Europeans, either independently or in collaboration with European writers, constructed themselves in theatre over the same period.

33 It was no surprise that published and produced white male playwrights vastly outnumbered both women and non-European playwrights in the nineteenth century; it was also perhaps no surprise that even sympathetic portrayals of First Nations characters in both American and Canadian plays of that era largely involved white actors portraying noble, tragic victims inevitably being swept away by nationalism, industrialism, and urbanization— forces that appeared to be as inexorable as Fate, even when they were being condemned as inhuman. What was surprising was how little those basic patterns had altered by the 1960s and 1970s that saw the first significant burst of contemporary Canadian playwriting.12 The white male voices that still dominated were definitely more sensitive, educated, and idealistic; they also genuinely felt theatre could change the world for the better through education, enlightenment, and activism, and that with hard work and good will the necessary revolutions were not that far away. Nonetheless, in play after play, the figure of the non-European as tragic victim emerged again and again.

34 Even women writers with a more acute sense of how the hidden class, gender, and socioeconomic imperatives of the medium could distort the message could not wholly avoid the same trap. In 1973, Evelyn Cherry, a disciple of documentary filmmaker John Grierson, shot a 30-minute film, Alcohol in My Land, in Frobisher Bay for the Territorial Government’s Alcohol Education program; true to the Grierson method, it was filmed in both Inuktitut and English, and used completely local residents, acting in their own environment and using dialogue as close to their own speech as possible, to tell their own stories and show how the community could “use its own resources to help relieve alcohol problems” (“New Film”).

35 Despite official enthusiasm for the film, however, the one letter on file from the Inuit Chairman of the Alcohol Committee, who was asked by Cherry to assess the effectiveness of the film, was far more guarded:

Was it possible that Cherry could not wholly escape the charge of situating indigenous peoples as victims in a white government-subsidized art form because her mentor, John Grierson, first Commissioner of the National Film Board, also failed to wholly resolve the anomaly of the same power structures he critiqued, simultaneously manipulating the vision and the form of his work?

36 The theatre and reading audience Ryga and his contemporaries constructed was also largely white, and middle-class. And while their vision did not exclude women and youth, their voice hailed men most forcefully as the authors of the power, military, and money structures that were causing oppression, and therefore as the only people with the real power, control, and authority to rewrite them. Yet, in shaming his target audience into a sense of their social responsibility, Ryga ended up stressing the plight of his indigenous characters as something that could only be fixed by those in power since only the people who had created the victimization could end it. But in doing so, he unwittingly continued the project of the nineteenth century mythologizers he deplored by objectifying the very people he was trying to help. As my former student Ken Williams argues, “Sure, Ryga is sympathetic to Indigenous people but we were merely a tool for him to condemn white people.”

37 Finally, to the extent that the politics of canonization—of who gets produced, then published so they can be taught in the university classroom—tend to be driven by similar biases, Rita Joe’s triumph in sweeping Canadian plays into the classroom may have been more pyrrhic than it initially looked.A Doll’s House may have revolutionized the nineteenth-century realist stage, brought the “woman question” powerfully to the attention of a massive reading and theatre-going public, and created strong roles for contemporary actresses, but few ask what doors it opened for struggling nineteenth-century women playwrights. To the extent that publishers, anthologists, scholars, and theatre managers were inclined to privilege the authoritative, familiar, and accessible to their audiences over the untested and unknown, “Nora” may have paradoxically slammed as many doors as she opened. The similar canonization of Rita Joe, Ken suggests again, had a deleterious effect on indigenous playwrights trying to get into production and print at the same time:

Long suggests that at the same time (the 1950s and 1960s) that white liberals “eager to educate a mainstream audience about the plight of Aboriginal people” were creating the first wave of professionally-produced Canadian plays to deal sympathetically with indigenous characters and issues, original indigenous theatre “also existed” but because it was happening “beyond the formal theatre structures” (140) it went largely unseen and unknown—on the stage, on the page, and on the curriculum.

38 In 1974, in the first issue of Canadian Theatre Review, Rubin dated “the emergence of the Canadian playwright from the appearance on November 23, 1967 of George Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe at the Vancouver Playhouse” (313). Instead of speaking of one monolithic Canadian Theatre that can be represented by a single play, it is more accurate today to talk about a series of Canadian theatre communities. Within that, it could be fairly said that Ryga did talk clearly, authentically, and powerfully to his own community, with all he had at his disposal, about the corrosive power of privilege and complacency, as fed by official evasions, distortions, and mythologies, to create terrible new versions of “the normal” that would eventually destroy us all in their profound dysfunction. Yet, he also had a profound faith in the future, provided people had the courage to interrogate with passion, anger, honesty, and intelligence “who we are and how we got that way” as a means of progressing to better, new, “popularly agreed-on” interpretations and versions of ourselves as a human community (Ryga, “Need” 208). Of all the forms of “misplaced geography” (Ryga, Ecstasy 78) that could result in a “generation of youth” losing “access to a part of themselves and their land” (Ryga, “Need” 209), misplacing the landscape of the past, and silencing voices that told us “how we got that way” (209), was one of the worst. It was, in Ryga’s words, one of those “so-called resolutions […] which are often-times worse than the original problems themselves” (Ryga, “Theatre” 337).

V

39 In 2011, for the first time in over two decades, I returned to teaching Rita Joe in the undergraduate classroom. Perhaps I now believe with Ryga that I am less of a “complacent educator” when I avoid “the posture of censor” and aim instead at being “partisan and advocate of a deepening and more complex cultivation of a people equipped for changing times” (Ryga, “Need” 209). That means, in Collingwood’s terms (and, in an odd way, in Miss Donohue’s), understanding the way our “knowledge of the past condition[s] our creation of the future” (334).

40 The final assignment of my Canadian drama course requires students to rank all the plays we have taken over the term, indicating the top three that they would include in an anthology of modern Canadian theatre intended to appeal to an international audience that knows little about us. I also ask them to rank the remaining runners-up and justify their rankings. In four years, Rita Joe has never been ranked lower than seventh (2015-16) in a field of 10-11 candidates, and often higher, finishing fifth (2013-14), fourth (2014-15), and, in one year, even third (2011-12). Some still consider its poetic expressionism and Brechtian elements intriguing; others find its dramaturgy confusing, fragmented, and irritating. However, the play’s historical status in the Canadian theatre as “one of the first to examine Aboriginal rights and issues, a major marker in Canadian nationhood” (Grummett), is almost always mentioned as a reason for ranking it fairly highly. However, many students quickly add their own variation of the qualifier that “Ryga’s depiction of Rita Joe as simply a victim of her circumstances unable to escape the cycle of oppression” turns the play into “a way of looking back in theatre history not forward” (Grummett).

41 For many, that is reason enough to exclude the play from the anthology—though never from consideration altogether. The voice of an outsider speaking its own rage and truth from the margins, if properly understood and contextualized as such, may still have an integrity of its own to share:

Just as importantly, Ryga bears witness, as outsider, to what never should have happened, never been “snowed under,” never be forgotten. In the midst of special remembrance days and anniversary years honouring Canada’s war dead, Ryga also reminds us that “[it] is of the utmost importance that the generations of Aboriginal sacrifice and hurt be recognized as a very real and essential part of Canadian History” (Zacharias). I am sure that I am not the only teacher who is now haunted by the face of a student among the murdered and vanished.

42 In 1977, when I first read Ryga’s comments about the “awesome power of the complacent educator” (209), I considered the phrase an arch, ironic attack on dogmatic incompetents like “The Teacher” and the educational establishment that produced them. Re-reading the same passages again, almost forty years later, after parenthood and almost three decades of teaching, it now seems to me that beneath the wit, Ryga was also speaking not just about enlightened youth and educators as a remedy to the problem, but even more profoundly and passionately about children, the terrifyingly vulnerable and valuable roots from which all else grows, as the only reality that counts in a deeply flawed world:

Where the play still resonates for me on the eve of its fiftieth anniversary is in its concern for the fate of children: not only the fate of the lost child in the classroom (“I’m scared, Miss Donohue. I’ve been a long time moving about . . . trying to find something I . . . I must’ve lost . . .” [Ryga, Ecstasy 80]), but even more profoundly the lost child in the woods. In that constantly shifting, ambiguous, reoccurring image of despair and hope, Ryga queries the future not just of the children that are and may be, but those that have been lost and forgotten along the way.

43 Fifty years later, Ryga’s image of “the generations to come” (“Need” 209) as a dragonfly breaking its “shell to get its wings” so it can fly “up. . .up. . .up. . .into the white sun. . .to the green sky. . .faster an’ faster. . .Higher. . .Higher!” (Ecstasy 121-22) is also more unspeakably poignant for me now than it was when I first read it. Realizing the extent to which the play may have been complicit in the very system it urged us to “set out to supersede” (Collingwood 334)—part of the “snow” it was trying to melt—may have been a necessary part of our “work of superseding it” (334). But I have also come to feel that if we do not retain its unique vision as an ongoing part of that work, “there will once more as so often in the past, be change but no progress” and “no kindly law of nature will save us from the fruits of our ignorance” (334).