Articles

May I have this dance?

Teaching, Performing, and Transforming in a University-Community Mixed-Ability Dance Theatre Project

Combining disability and dance may not be new, yet enacting inclusive dance/drama education in a university remains rare. This article reflects on the integration of people with developmental disabilities in dance theatre, particularly in institutions of higher education, and shares insights that emerged in the context of an inclusive dance-theatre project. Over two years, the project progressed from a community-based art for social change partnership, to a post-secondary drama course, to a large-scale, university-produced theatrical production. Drawing on qualitative, embodied, and quantitative data the authors critically reflect on the potential for integrated dance theatre work to contribute to training future professional artists with disabilities, to enrich curriculum for students without disabilities, to inform theory and practice in the field of art for social change, and to positively affect the perceptions and experiences of people living with disabilities.

Allier le handicap et la danse n’est peut-être pas nouveau, mais instituer des cours inclusifs de dansethéâtre dans un milieu universitaire demeure un événement rare. Cet article traite de l’inclusion de personnes ayant une déficience développementale dans une initiative de danse-théâtre en milieu universitaire et des réflexions qui en ont surgi. En deux ans, un projet de partenariat communautaire dans le domaine des arts pour le changement social a mené à la création d’un cours de théâtre postsecondaire et à une production théâtrale de grande envergure à l’université. À partir de données qualitatives, quantitatives, et incorporées, les auteurs livrent une réflexion critique sur l’apport de la danse-théâtre intégrée à la formation de futurs artistes professionnels ayant un handicap, à l’enrichissement du curriculum des étudiants sans handicap, au développement de la théorie et de la pratique dans le domaine des arts pour le changement social ainsi qu’à une meilleure perception et expérience des personnes vivant avec un handicap.

1 This article and the project it describes came about because the authors accepted an invitation to dance with disability. In 2013, the Lethbridge Association for Community Living (LACL)—a non-governmental organization supporting families of people with developmental disabilities—invited one of the authors, a theatre professor at a smaller comprehensive university in Western Canada, to bring the arts into their advocacy agenda. Accepting that invitation led to ongoing partnerships with many individuals, institutions, and communities. The first project was UpStart, community-based Dance Drama and Self Advocacy Workshops in partnership with LACL, the Southern Alberta Individualized Planning Association (SAIPA), and the South Region Self Advocates Network (SRSAN) (Doolittle and Harrowing). These partnerships continued into a for-credit topics course in Fall 2014 in the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Lethbridge (UL) entitled “All-abilities Dance Drama: Production Development,” the first course in this undergraduate theatre program to include a group of people with developmental disabilities. Several course participants, with additional cast members, went on to create and perform in a mixed abilities dance-drama production entitled Unlimited that was presented in the university’s 450-seat theatre over five nights in March 2015. All of these projects are the subject of research, partly funded through a multi-year SSHRC national research partnership investigating Arts for Social Change (ASC!).1

2 In this article we look backwards and forwards, assessing the impact of the university course and production on individuals and the local community, and hypothesizing about the contribution this experiment may make to the field of disability arts and pedagogy. “We,” the authors of this essay, include: Doolittle, Theatre Arts professor, course instructor, production co-director and the ASC! project teaching and learning research lead; Makoloski, a K-12 teacher and regional Special Education co-ordinator, graduate research assistant, and the production’s assistant choreographer; Chasse, Master of Social Work student, a course/research assistant and performer in the production; and Boyd, MoMo Dance Theatre’s Artistic Director (Calgary), visiting professional artist and teacher, and production co-director. “We” also includes Yassi, a professor who is a co-investigator on Arts-for-Social Change (ASC!) project, leading the efforts on evaluation of such endeavours.

Dancing into Disability Arts: Theory, Methods, Data, and Local context

3 Our title, “May I have this dance?,” evokes that moment of indecision, of sizing up the invitation, before agreeing to begin dancing. A community asked us, and we asked the university our drama department, to dance into inclusion. “May I?” also evokes questions of access, permission, and ownership: whose dance is this anyway, and why might I have it or not? As with many invitations to dance with strangers, our partnering has included moments of deep connection and brilliant improvisation along with many awkward missteps—who is supposed to be leading, or following? What kind of inclusion dance shall we perform together, and where will it take us?

4 With several newcomers to the field of disability studies on the project team, an orientation to the rapidly evolving debates and stakes around issues of identity and terminology was an important first step. In the Alberta social services, and among our community partners, the most widely accepted terminology is people-first, so we use “people with developmental disabilities” here. We also use “developmental disabilities” because this was suggested by our partner organization members and family members as the most common term used locally. Our research showed that “learning disabled” in the UK and “intellectually disabled” in Australia are more commonly used, and in this article we will use these terms as the authors do. During the Fall 2014 course the instructional team encountered Anna Hickey-Moody’s concept of reverse integration (2009), which is applied in the mixed ability context of Restless Dance Theatre in Australia, whose performance work she analyzes. Also, Pamela Boyd had interned with this company and her company’s work is influenced by their approach. Members of Restless refer to people with disabilities as people “with” and non-disabled people as people “without.” These terms are used “in order to challenge the idea of including people with a disability,” and are further supported “by means of constructing an environment for devising dance theatre, a supportive space in which ‘intellectual disability’ is known as an individual’s style of process and their unique performance quality” (Hickey-Moody xvi). Feeling a strong connection from our emerging pedagogical and dance-theatre creation experiences to the way that this terminology unsettled the medical, deficit approach to disability, we used Hickey-Moody’s terms in our reflective research process and analysis. We did not use them in any direct communications with student participants or families, instead using the people-first terms.

5 Cross-sector and interdisciplinary partnerships, with their differing terminologies, practices, and theoretical frameworks, complicate engagement in social change research. This article describes and questions our project’s location on a continuum of ethical engagement, especially between community and university, in the context of disability arts and change research. First we situate our work within the larger context of disability arts, and within the pedagogy both of performing arts and community-engaged arts. Next, we analyze the effects of introducing mixed ability and inclusive artistic practices into teaching and learning in the post-secondary drama studio and in production creation and performance. Finally we consider the implications of our experiences for post-secondary arts education, community-university partnerships, and social action around issues of access for people with developmental disabilities.

6 Following Giles Perring, we acknowledge how our non-disabled subject positions may have created problematic power differentials, even as we consciously attempted to use our positions to support participants with and without disabilities to participate fully and contribute artistically to the project. Visiting artist Boyd often challenged university insider positions with insightful and provocative comments, pedagogical approaches, and artistic choices. Frequent consultations with our community partners—disability service and advocacy groups—in all phases of the project influenced the direction of the work. Our analysis does not claim objectivity. Radical community-based pedagogues Motta and Esteves argue that “new possibilities arise when we learn to cross, to blur, to undermine, or overflow the hierarchical and binary oppositions we have been taught […] (instead) nurturing critical intimacy” (5). Our encounters with developmental disability in the university compelled reconsideration of the disabled/non-disabled binary. We take our deep implication in the work to be an asset that gave us insights unavailable to those at a critical distance. Our research data include experiences, and documents of experiences, participant and project leader reflective journals, photographs, filmed rehearsals and performances, rehearsal notes, interviews and focus group discussions with disabled and non-disabled participants in the course and production, discussions with families and community organizations, and our own embodied experiences. We were able also to conduct quantitative evaluation, administering and analyzing an audience questionnaire. We adhered to a human subject research protocol approved by committees at UL, UBC and at the lead ASC! institution, Simon Fraser University. After participatory information sessions, we obtained written consent from students, parents, agency employees, UL Drama Department faculty and staff, ASC! Project team members, and filmmakers. Participants with disabilities who were not their own legal guardian signed consent forms, as did guardians. A small percentage of students and some participants with disabilities and their guardians did not agree to sign. The consents granted use for research of written, spoken, embodied, performed, and filmed contributions.2 The range of voices that spoke to us and that we share with their explicit permission here lends some validity to our findings and partially addresses the problem of our complicities.

7 While we reference various theoretical stances, the project, emerging out of a community partnership, did not begin from theory, and the authors dance cautiously as we absorb and combine theory from outside our respective disciplines.3 A key paradigm in the field of disability studies is the social model of disability and its many conceptual connections to disability arts (Titchkosky 25-6; Johnston 11).4 This conception of social identity as performative and malleable makes embodied performance a rich place from which to begin change agendas. Sandahl and Auslander advocate interdisciplinarity, connecting disability studies’ social model to Performance Studies’ concept of performativity: “[T]o think of disability not as a physical condition, but as a way of interacting with a world that is frequently inhospitable is to think of disability in performative terms —as something one does rather than something one is” (10; see also Johnston 12). Our analysis also draws on work about or by participatory or community-engaged arts scholars and practitioners,5 and it draws on radical and community-based pedagogy more generally.6 Our recent mixed-ability projects evolved out of our own community-engaged practices. Some politicized disabled artists resist the paradigm of participatory “applied” arts work, wishing to distance themselves from the prevalent and reductive idea that when disabled people “participate” in the arts the only purpose can be individualized therapy. Others feel that “the meeting of applied theatre and disability offers a productive area of discursive practice” (Conroy 11). Conceiving of arts pedagogy and performance as change, and rejecting binaries of professional/therapeutic, along with abled/disabled, the Unlimited teaching and performance attempted to do disability differently, in the studio, in the theatre, in the university, and in the lives of our project contributors.

Inclusive Teaching and Learning

8 Combining disability and dance may not be new, yet enacting inclusive dance/drama education in a university remains rare.7 As we grappled with diversity in the performance training classroom, strategies for inclusion emerged. Eighteen students completed the course, of which six were part-time, open studies students with developmental disabilities. Properly enrolling these six students to allow them full credit status in the class was a long voyage of discovery for us as we encountered financial, bureaucratic, and physical barriers, and administrative resistance that was new to us but all too familiar to our community partners. For example, here is one situation: our students “with” could not take on full course loads because of transportation inaccessibilities, their need to maintain scarce part-time employment, and the many ways that inflexible academic timetables do not accommodate non-normate health needs and varying levels of daily endurance. As bureaucratically designated part-time students, the disabled students who participated were therefore ineligible forany scholarships or student loans; the only way for them to get credit for their course participation was through a one-time generous donation from a private sponsor. Canadian disability studies scholar Tanya Titchkosky brilliantly exposes the “unanswers” to the question of access for the disabled to post-secondary education more generally by using a perspective she calls a “politics of wonder” (129-50). Wondering about why things are the way they are is a first step toward improving the way things are. Our inexperience made us wonder about why things are the way they are regarding developmental disability in post secondary environments and in the arts. The twelve full-time non-disabled students—a combination of drama performance majors and students taking the class as an elective—worked alongside the six part-timers in a large black-box studio for two hours, three mornings per week, for thirteen weeks. Familiar with the need for additional supports for people with developmental disabilities from our partnership with community agencies, we used research grants to bring into the classroom two graduate teaching assistants, one with experience in K-12 special needs education and another with experience in social work. LACL obtained funding for a Drama Education undergraduate to liaise with the instructional team and with the families of students with disabilities. Drama department visiting artist funds paid for some of Boyd’s work.

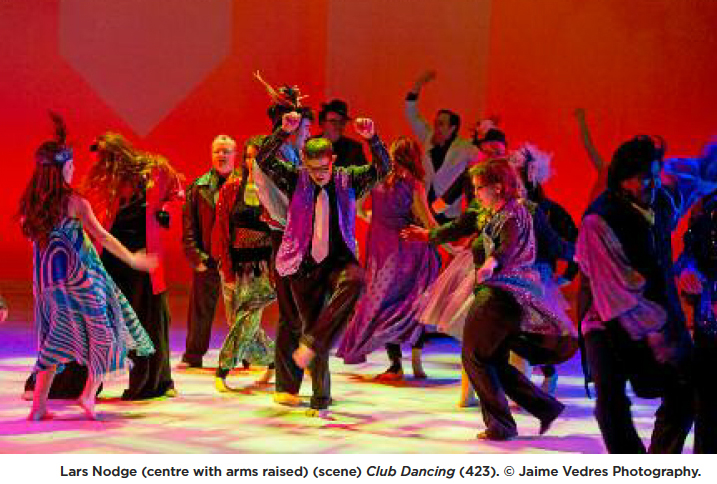

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 While mixing members of the disabilities community with full-time students was new to our department and university, the course objective—to create material for a production— was part of the department’s curricular mandate for training in theatre creation. In our mixed ability classroom, the drive for inclusion shaped both method and content. The mixture of students with and without disabilities presented parameters different from work that focuses exclusively on artists with disabilities. Moreover, the project aimed to include people “with” developmental disability in particular. Perring points out that arts work with people with learning disability frequently involves non-learning-disabled people in the production of the work, and thus raises ethical issues around power and the need for reflexivity. And yet “in the midst of the personal reflection is the need to move beyond questions of self, towards creating work that has ‘immediate relevance’” (175). Through sharing written reflections and regular conferencing, the teacher/learner team supported each other and the students, constantly revisiting methods, problem solving, and discussing new directions. Early reflections show that the teaching assistants undertook most of the work in class to include students “with” who were struggling. As we observed that doing so was preventing other students from also experiencing one-on-one inclusive work, the assistants gradually retreated from this role. Inclusion through peer-to-peer teaching and learning informed assignment design. Performance creation assignments ranged from duets, to small groups, to solos. In the duet creation process, each student told a personal story to their partner, then together embodied still images to express each narrative. They then combined these images with new ones to devise a story/dance that drew from both individual scenarios. Student reflections8 on mixed ability pairings help us glimpse the process both for those with and without disabilities. Cameron Brucker’s journal entry (29 Sept. 2014) describes working with Lars Nodge who, while a fantastic improviser, was unlikely to repeat exactly what they practiced together in performance: “It can be frustrating at times because I am such a perfectionist and it pushed me to be able to … just go with the flow when we have to perform together … all the trouble I felt … made me think about what he must adjust to be able to try and make it work. Lars and I built a strong connection throughout the practices and performance.” Scott Boomer was at first concerned at the way Randy Chandler, his duet partner, seemed unable or unwilling to initiate modifications to improve their work, but “In our last refinement Randy initiated a change in the routine. I was ecstatic that he made a new choice—his communication to change something was impressive … I list this as my number one feat; Randy expanding his creativity” (1 Oct. 2014).

10 In the solo creation process, students worked in mixed ability trios. Within each trio, students interviewed each other and improvised together to discover and develop potential content ideas, and performed and gave feedback on solos-in-progress. Instructors observed support and reinforcement, but also confusion and resistance in this process. While all participated, some drama students reverted to creating their own solos independently, mostly outside of class time. Some of the students “with” began by recreating excerpts from pieces of favorite popular culture, yet ended up with more personalized expressions. Bill Blair, who frequently appropriated character moves from Grease in improvisations, ended up dancing lyrically with a silk scarf to Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet, expressing “romance.” Lars, an accomplished painter, performed a movement dialogue with one of his art works, showing creative development beyond habitual expressive choice of improvised hip hop dance moves. The trio/solo process allowed students with and without disabilities not only to create their own work but also to experience peer-to-peer teaching as dramaturges and mentors for their colleagues, and to develop capacities in performance, creation, direction, and critical observation.

11 In student journals, one of the most talked about aspects of the class was the creation of trust, expressed in acts of reciprocity and mutuality. This was developed gradually through overt trust-building games. In one game, an eyes-closed partner travels freely through space, while an eyes-open partner prevents collisions using tactile nonverbal signals. Variations on this game to better include a sight-impaired student created not only trust but also new awareness of disability. In “trust falls,” where the group must collectively catch a free falling student, it was interesting that levels of fear and confidence did not align with levels of dis/ability. Trust-building was also embedded in warm-ups (such as partner assisted stretching) and in improvisation structures (especially contact improvisation). Literal and figurative support among all members of this class was a particularly strong realization of the sense of ensemble that is a desired outcome in most drama training.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Anna Hickey-Moody’s discussion of Restless training and creation methods, which mix people with intellectual disabilities and non-disabled dancers, was particularly resonant for us. Our pedagogical approach leaned heavily on her concept of reverse integration, “the practice of people without intellectual disabilities ‘integrating’ to fit in with the styles of people with intellectual disabilities” (xv), rather than on the more prevalent medical-therapeutic model of helping people with disabilities become more like people without. Familiar dance and theatre creation techniques were reinvented and energized by this approach. For some non-disabled students to move from an attitude of accommodating people with disabilities into their standard ways of working and toward the realization that art created from the processes and perspectives of the students with disabilities could be innovative and powerful was an unattainable paradigm shift. Still, change happened in and through the body. Given that many students were not steeped in academic and disciplinary-specific discourses or practiced in its related verbal pedagogy, activities focused on nonverbal expression: exercises in touch, partner-triggered impulses, sculpting, making group images. In one assignment, small groups of students created and performed image-theatre-based scenes on the emotion-laden theme of being included or excluded from a group. As they embodied relationships while creating these scenarios, avenues to both staged and real empathy opened up. During this creation process, one student “without” said that being sculpted by a student “with” into a position expressing “sadness” that was new to him opened up creative possibilities he had not previously contemplated. Nicole MacDonald reflected: “This assignment is definitely helping everybody get closer together and working more as a team and get a lot of support from one another” (journal entry #5).

13 Another reverse integration strategy was to work improvisationally. Freed from memorization and precise repetition, some students “with’” contributed spontaneously and created movement alongside others in wordless but physically articulate artistic exchanges. Some students, both “with” and “without,” inexperienced in improvisational approaches to creation, complained about “not knowing what we are doing.” Some students with disabilities had experienced so much oppressive control in their lives in the form of “guidance” and “help” that it took time for them to open up to improvisation. Our open-ended approach led some students “with” to seek significant validation about whether they were doing exercises correctly or not. Others became more distracted in the absence of set text.

14 For the instructional team, reverse integration invited broader questioning of course demands and the tenets of standard professional behaviours. For example, the course team at first mistakenly linked disruptive behaviours like distractability or the sudden outbursts of anger of some students “with” to disability diagnoses, reverting to the “medical model” of disability and locating problems within the individual, non-conformist body. After reflecting further on the context and on past teaching experiences in non-integrated courses, however, where learning is also affected by lack of clarity in instructions, insufficient time, or interpersonal tensions, and where students often suppress their frustrations, the course team began to understand these behaviours as more intense embodiments of learning disconnects and struggles against coercion that are typical in any group of learners. We therefore slowed down, added more physical demonstrations, and provided more direct group mentorship to make instruction better for all students, not just those “with.” Finding activities that allow for many different learning styles is not just better mixed-ability pedagogy, it is better pedagogy period.

15 Innovating the learning through a focus on inclusion was hampered by entrenched ableist perceptions of excellence, skill, and technical and creative “challenge.” Disability performance theorist Carrie Sandahl has examined ways that actor training presumes a naturalistic “neutral” body (259-62), an ableist construction which she points out makes inclusion of people with obvious disabilities in actor training programs virtually unthinkable. Viewing the body and embodiment as socially constructed “corporealities,” Dance Studies scholar Susan Leigh Foster critiques the unexamined practices of traditional dance training that “emphasize(s) the development of bodily control and aesthetic virtuosity (and) can easily negate the presence of the individual, creating a ‘multipurpose hired body [that] subsumes and smooths over differences’” (256). Disability dance contests this “vision of professional dance that equates physical ability with aesthetic quality” (Cooper Albright 57), proposing inclusive training and integrated performances that disrupt normative corporealities (Whatley 23). Complaints about lack of challenge indicated that some students “without,” immersed in normate conceptions of art and arts training, never fully embraced the inclusion mandate. While such attitudes may have negatively affected the learning of the people with disabilities, adaptations that some resisted others found enabling: “Learning in a group is so much easier because if you don’t understand something then there is always someone to explain it to you” (Nicole MacDonald, n.d, journal entry #6). This brief exposure to inclusive teaching and learning may spark the beginnings of ethical consciousness and changing subjectivities. If never confronted with difference, how can students “without” develop an ethical sense of the Other? The students that fully embraced inclusion felt they had valuable artistic learning experiences. Experienced dancer Scott Boomer reflected: “The (students ‘with’) have so much to offer […] I wonder if I learned more from them, or they learned more from the class” (3 Dec. 2014). Also, if always required to meet arbitrary ableist “standards” and never allowed to work in open-ended ways, how can students “with” experience agency and find their own voice? Lars Nodge, whose kinesthetic inventiveness was perceived as odd outside of the class, discovered that it was an asset inside. The intimate acts of shared improvisation and creation allowed some new creative possibilities to arise and opened a way for some learners to perceive and experience disability differently.

16 At first, course work did not involve in-class discussions about social inequity and privilege, although students were invited to confront and reflect on any discomforts directly in the studio and/or in their journals. Rather than focus on the inequities that the “social model” of disability so clearly identifies, we chose to embody equity in our methods. It became clear that unrecognized inequity and privilege got in the way of learning and hampered artistic innovation. Some guests, UpStart Workshop alumni, and the LACL director were invited to dialogue with the class about self-advocacy, the history of institutionalization, the evolution towards community living, and persistent barriers for people with developmental disabilities. Some classwork more directly addressed disability issues. In “Cross the line if … ,” an exercise where differences can be instantly made visible, a revelation came in response to the seemingly innocuous question “cross the line if you have a driver’s license.” None of the people “with” crossed the line, sparking a lively dialogue about the barriers such a deficit posed. One student reflected that this “let us understand our classmates more and at times changed our minds about certain matters.” These interventions aimed to move students away from the stereotypical charitable model of support for disabled people, where pity and sympathy are the operational emotions, and towards feelings of empathy that are more conducive to reciprocity and lasting social change (Goodman 123). Working as we did on an ad hoc, short-term basis within a non-inclusive educational and social context, it is unrealistic to suppose that such a lofty goal was understood or embraced by all students. Seeing, and improvising with, the different dialects of different bodies may have created empathies that are not easily articulated. One observable arc of growth involved students “without” increasingly using less oppressive and more respectful ways of supporting the students “with,” possibly learned by observing the course team’s interactions with them. Over time we saw less pulling/pushing/hand-over-hand manipulating, and more invitational language, provision of choice, and embracing of difference. Most students demonstrated increased group awareness, evidenced in journal entries that progressed from “I” statements to “we” statements over the semester. Nicole MacDonald moves from basic documentation, “We got to know one another and we got to learn the rules” (12 Sept. 2014), to complex connections between feeling and thinking: “This class is all about drama and dance for mixed abilities, and it shows that people with disabilities can be accepted into a regular class and not being left out or feeling excluded from the mainstream classes. I also thought we were becoming a family” (journal entry #3). Jeffrey Charlton moved from curiosity to commitment in his reflections:

On the teaching side, adapting methodologies was not difficult. With little previous experience in mixed abilities arts or pedagogy, the course team echoed other drama teachers who have tried it for the first time: “One of the essential learning achievements was that teachers were clear in their feedback that adjusting their teaching methods or finding ways to make lessons inclusive was not an issue” (Dacre and Bulmer 136). The adaptations spur pedagogical innovation: “I have witnessed tutors do a complete about-face in their thinking about how they teach their subject. We have shifted perspectives with this work” (138). The drama/dance classroom, with its focus on embodied learning, can be a rich environment not just for pedagogical change but also for social change. Motta and Esteves claim that “Pedagogy is central in both how we learn hegemonic forms of life, social relationships and subjectivities, but also [in] practices of unlearning these and learning new ones” (1). Our course methods and content invited participants to enact change in the ways that non-disabled and disabled people could/can work together, even beyond the classroom. Working side by side in physical and creative intimacy, and confronted by the lifelong implications of restricted incomes, insufficient services, and limits on the freedoms experienced by students “with,” the course may have begun to develop an “empathy muscle,” particularly in the students “without,” that may flex wherever they confront social injustice. Makoloski reflected that, in his prior experiences with university special education teacher preparation courses and in the K-12 system as both teacher and special needs coordinator, he had never seen the theories of inclusive pedagogy fully enacted in this way. “We are no longer just talking about students with disability but instead are working with them in a reciprocal learning environment”(3 Dec. 2014). In inclusive embodied learning experiences, the potential for unlearning stereotypes and learning empathy becomes available.

Inclusive Creating and Performing

17 Twenty-two people were cast from open auditions for the Spring 2015 production; eight of these had not been in the class and most were relatively inexperienced performers. We could not have created Unlimited without the experience of teaching inclusively, nor could we have accomplished much without the subtle inclusive skills that students from the course brought into rehearsals. Having observed how co-creation wonderfully jumbled up the complex binary between students with and without disability, the co-directors decided that the show’s content need not focus directly on disability issues. Rather, inclusive methods of performance creation that focused on developing creative agency through individual character development and on ensemble improvisation could blur distinctions, and embody rather than preach inclusion. Dramaturgical choices furthered the inclusion agenda. The co-directors set a loose framework or storyline of: preparations, going to, being at, and leaving a grand party. The party setting would offer all characters a chance to transform, to break free of everyday limitations. The working title of the show had been Inclusion, but tellingly, we felt compelled to change it to Unlimited as an indication of our expanding perceptions around disability.9

18 Aiming to draw out each person’s performance strengths, we began with workshops where cast members created and physicalized their own characters. Perring proposes that “ (i)f art can act as a means of constructing the self, then the subjectification, rather than objectification, of all the artists in an arts-and-disabilities project must be facilitated” (186). Physicality is key for this kind of subjectification to occur in a mixed abilities process including intellectually disabled people. Indeed, argues Hickey-Moody, “the process of devising and performing integrated dance theatre texts kinesthetically reconfigures dancers’ embodied subjectivities. Such corporeal change alters the ways in which people with intellectual disability know themselves” (73). In creating physicalized characters, all cast members infused their respective characters with aspects of themselves. Everyone could contribute equitably to the show, and everyone could feel a sense of efficacy.

19 Challenges arose for all ensemble members as they worked to give depth and purpose to their character’s journey. Nicole MacDonald noted: “It felt difficult forming my character … (but) I knew that everybody that was there helped me express my character even more—so it helped a lot” (Focus group). Randy Chandler expressed not only personal commitment, but also the reciprocity within the ensemble: “My solo part? Well that took a lot of practice […] It took time to practice especially with all the choreography. All that hard work that I did with being part of a group and being there to support each other and it’s sort of like teamwork” (Focus group). The mutuality of the shared challenge to create meaningful characterizations may have contributed to increased understanding of all the ensemble members’ subjectivities and contributions. Marshall Vielle reflected: “Onstage it looks like we’re all just having a blast, but what the audience (doesn’t) know is about the process … the long, long hours and the hard times, […] doing it together is what made the process really nice,” while Gerry Campbell-Greer told us “I was just concerned for other people instead of just myself. I was just really trying to be really caring about others” (Focus group).

20 Ensemble improvisational processes that had supported the inclusive classwork also provided a foundation for performers to generate material in our production process. Hickey-Moody argues that dancing together is uniquely empowering for people with intellectual disabilities: “… processes of identity re-negotiation are facilitated by ensemble process and are inextricably linked to the production of movement aesthetics. As such, part of the subjective labour of dancers’ creating original performance material is the enmeshment of self with a movement aesthetic developed in relation to the ensemble” (58). Further, and importantly, Hickey-Moody argues that movement improvisation in creation and performance is key to producing an “affective force,” a force that allows participants and viewers to perceive intellectual disability differently. One cast member “with,” Lars Nodge, created unbridled and brilliant dance improvisations. While imposed dance steps or rigid structures caused confusion and frustration, when he improvised in the midst of a crowd (in both rehearsals and performances) he moved more assuredly and seemed to become more profoundly expressive. His immersive and self-realizing dancing created an affective force, and this is the force, that according to Hickey-Moody, not only transforms him, but also has potential to transform those who watch him.

21 Mixing identities and abilities happened not only in the improvised sections; the strictly choreographed full cast waltz leveled the playing field in a different way—some performers “with” were much better social dancers than some performers “without.” Peer to peer coaching—working together on getting the steps and formations exactly right—furthered collaboration within the cast. Unison sequences enacted and expressed inclusion differently. Also, set choreography supported some cast members “with” more than others. Maggie Mackay, our youngest cast member “with,” often declined participation in the seeming chaos of improvised work but flourished in a choreographed duet and in the waltz’s precision. Near the end of the rehearsal period, she became more open to joining improvised scenes. Given more time, the support of the ensemble may have enabled her to join all scenes both choreographed and improvised.

22 As the party scene moved from formal waltz to chaotic revelry, characters morphed into their alter egos. Even the room itself was transformed as cast members ripped off giant swaths of the paper set that mimicked formal drapery to create fanciful and uncontrollable objects–like paper hearts that could throb, fly or could be torn apart in romantic encounters and tragedies. Animated objects combined in bizarre vignettes, such as a giant wave that became a fashion runway, and finally an ominous “people changing” machine that alluded to the role eugenics and institutionalization has played in the history of people with developmental disabilities. A party is what Victor Turner calls a liminal zone: “liminality is […] a time and place of withdrawal from normal modes of social action, [and] it can be seen as potentially a period of scrutinization of the central values and axioms of the culture in which it occurs” (qtd. in Hickey-Moody 70). A wild party as anchor for our project’s objective of confronting and overcoming limits may seem frivolous, but in the Unlimited party, perceptions of disability could be challenged. Characters deconstructed the limiting social environment of the high-class ballroom and, together, explored what “limitless” might look and feel like. The rather vague, implied, Pollyanna-ish message—you can be anyone you choose to be—was mitigated by the more precise, diverse, and mixed results that the casting-off of various limitations produced for each character.

23 Following the journey of one key character, invented by Randy Chandler, a performer “with,” may give a better sense of how improvisational methods and dramaturgical choices worked together. In the first solo character improvisation work, he chose (like many others) to embody positive traits: compassionate and loving. At our request for everyone to find “the dark side” of their characters, he chose to become Captain Hook, full of bravado and tinged with anger. Ultimately, these characteristics combined to become what we called the Forgotten Person. Developed in sustained one-on-one interactions with Boyd, and through Randy’s guided research on homeless people, the Forgotten Person/Randy became the first character to be introduced in the show. He begins alone, curled up against a graffitied wall under a ragged blanket. His wordless pleas for spare change ignored by preoccupied passersby, he enters a fantasy world, sword-fighting imaginary foes with a cardboard tube. In group improvisations like “Round Robin,” which put his character into unplanned interaction with others, he deepened his embodied understanding of the person he chose to portray. Codirectors saw synergies between the Forgotten Person and a female character with a similar tendency to escape to an imaginary world. A scene developed where these two find kinship in an improvised, mirroring duo. She discovers a tattered Captain Hook frock coat for him in a pile of discarded clothes along with some party bling for herself. Together they are emboldened to sneak into the fancy ball. When the start of formal waltzing is announced, the entire cast freezes in embarrassment as a Rich Patroness character finds herself without a dance partner. Randy, who showed himself to be a good social dancer in waltz choreography rehearsals, steps out of the shadows to utter the only words in the entire production: “May I have this dance?” He is clearly and unacceptably her social inferior, but the public setting means that she must accept his offer; nevertheless, in an aside, improvised in a rehearsal, she conspicuously grimaces and wipes her hands as they part at the end of the waltz. The scene would have had further layers of meaning for the disability community insiders in the audience, many of whom knew Randy as a leader in the self-advocacy community. Randy continues to push at apparent limits to his character’s participation, joining the ensemble enthusiastically in increasingly uncontrolled festivities. At the end of the party the Forgotten Person is back where he started, alone in the alley. The Patroness, transformed into an unfettered party animal, runs into him as she staggers home. In her inebriated embrace, somehow her fur coat transfers, unremarked, to Randy, and she carelessly continues on. As the Forgotten Person heads back to his grubby wall, wrapped in inadvertent largesse in the form of a fur coat blanket, the audience can imagine how his new comfort is likely temporary. Just as the community established in the party community breaks apart, the promise of his integration disintegrates.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 324 We began to see how this character’s journey mirrored the temporary ways in which disability enters and leaves the world of the privileged. The interactions with the Patroness were an embodiment of “careless caring”: while current culture compels most to profess caring about disability, “… ‘careless caring’ is an ordinary way for people to achieve an ordinary relation to disability. […] worrying about how we care about disability would not be an ordinary way to do the job of addressing what is otherwise barely relevant” (Titchkosky 88). As a lead character in this show, Randy was able to experience being centre stage, dancing in an integrated ensemble and creating a character from his own perspective. While he is highly motivated to train further in theatre, the opportunity to do so, or to earn a living in the theatre world, is not available to him locally, or really anywhere in Canada. He has returned to his job, his Special Olympics championship curling team, and his separate community. So, was Unlimited, a time and resources-limited project, just another act of careless caring?

Inclusion Behind the Scenes and Beyond the Stage

25 In response to that legitimate question, we rally personal participant testimonies and evidence from the audience, trying to tease out tactics that may counter carelessness with more enduring and committed engagement. Communications from families of cast members “with” confirmed transformations occurring beyond the stage. Gerry Campbell-Greer’s mother’s emotional opening night letter to the cast is typical of the responses to the project of many families of cast members “with”:

Is it only coincidental that Gerry is currently enrolled in academic upgrading at the community college, had full time summer work for the first time ever (employed in the show’s lighting designer’s landscaping business), and became a member of the college student association? Maggie MacKay’s parents reported lasting effects of her participation, seeing more confidence and risk-taking during and after this production. Individual character development, along with both the set and improvised choreography, offered many ways for both actors “with” and “without” to develop deeper expressive skills, a different sense of self, and a strong ensemble. Above all, Unlimited gave participants “with” an all too rare chance to innovate, create, and perform in a high-stakes but inclusive environment. Frequent social interaction, networking possibilities with peers and educators, connections to support organizations, and purposeful participation in directed research about issues in their lives increased a sense of belonging and value, and widened the lens through which cast members “with” viewed their out-of-studio and offstage experiences. We also need to acknowledge and assess our missteps, however. Right after the closing party, we received a devastating email from another parent: “The drama students go on. They continue with the arts or not. It is their choice but now what’s there for the people with disabilities that experienced it [?] […] The follow up is never there” (Westling). As partial, and inadequate, response to this compelling cri de coeur, we present a summary of audience questionnaire results, and describe some institutional and community developments that unfolded after the project finished.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 426 Two of the most frequent comments heard from audience members were that they really wanted to join that super fun onstage party, and that they could not differentiate between the “withs” and “withouts.” A blurring of perceptions of difference perhaps indicates that our dramaturgical choices worked to dismantle the binary of disabled and non-disabled (Perring 186). Audiences and their perceptions are unruly, however, and consensus unlikely.

27 We sought to more accurately measure whether that audience engagement with the onstage blurring of identities and transformations of spaces might lead to change in perception and/or action around disability. The ASC! Partnership’s Evaluation team helped to administer and analyze an audience survey.10 Over five nights, 1025 people sat down together to witness the Unlimited version of an inclusive society, 512 of whom took time to fill out and submit the four-page audience questionnaire. Here are some of the findings. Of the respondents, 70.5% were female, with the largest age groups overall reported as 19-24 and 55+ (142 [28.5%], 111 [22.2%] respectively). Some were people with disabilities (6.8%), many had a friend or family member with disability (46.7%), 28.9% worked with someone with a disability, and only 64 participants (12.5%) stated that they did not currently know anyone with a disability. The vast majority of respondents (86.9%) indicated that they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I was completely absorbed by what was happening”; 89.2% of those surveyed stated that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statement “I was gripped by the sights and sounds of the performance.”11 430 said, “I found the whole experience really worthwhile” (agree or strongly agree; 84.3%). These results were similar across age groups, genders, and closeness to a person with a disability.

28 In the second part of the survey, individuals were asked to comment on their social engagement with people with disabilities before the play, and if any change occurred as a result of their viewing Unlimited. For example, to the question “Consider involvement in activities with people with disabilities,” 51 respondents stated that for them this was “unlikely” or “definitely not” before viewing the performance. Of these, 21 noted that seeing the play had moved them to a “maybe”; 13 moved to “likely” and two said it was now “very likely” post-performance. This is a highly statistically significant result. 12 Another question asked about the likeliness to “Participate in organizations, community projects, or social activism concerned with the rights of people with disabilities,” with many participants again indicating a shift in perception and agency.

29 The questionnaire also invited audience members to share their thoughts on inclusion of people with disabilities in the university world. Many respondents articulated their feelings on this topic: “Inclusion is a must. It improves the quality of life for the disabled and also improves the university experience for the non-disabled students.” Others mused on the role of the university in broader society: “The possibility of inclusive education on campus is a worthwhile one. The campus should model a better world”; “Everyone should be allowed to pursue their dreams with whatever accommodation is necessary.”

30 To expand the potential for new perceptions and new actions, we facilitated talkbacks after each performance of Unlimited with cast members, the audience, and guest speakers, including key stakeholders important to regional disabilities policies. Constructive conversations between policy makers, community organizers, artists, and educators occurred that could move local action on inclusion forward. The large theatre setting, the presence of the public, and the university “brand” all played a part in legitimizing the work and its messages. Inclusion in professional theatre training programs on or off campus faces very real if unspoken resistance from inside the theatre profession (Dacre; Johnston). Doing this work in a university “demonstrates respectability and acceptance and has the possibility of making faster inroads into changing attitudes” (Boyd). Being embedded in a university program also assured us a better balance of participants. While our university training attracted a student mix of two thirds “without” and one third “with,” many community-based arts training programs attract few people without disabilities: “[Unlimited] more closely mirrored the demographic of the general population. This significantly impacts the progress, level and proficiency of the work” (Boyd).

31 It would be convenient to pronounce that Unlimited had prompted moves toward better access for people with developmental disabilities at the University of Lethbridge, but that is a claim we cannot substantiate. Doolittle initiated a campus-wide working group to instigate better access to university education for people with developmental disabilities which has since been dissolved. It appears that a new program for this population at this university is in the works; its objectives may or may not resemble this project’s integration goals and may or may not include access to theatre courses. A twelve-week series of twice-weekly accessible dance classes at the city’s arts centre, which has attracted over forty mixed ability participants, was initiated by Unlimited’s community partners. A documentary film, Making Change, Making Unlimited, is in production and will be widely distributed. But barriers of perception still combine with very real societally and bureaucratically imposed barriers. Assistant director Makoloski felt the course and production were less about making social change and more about raising awareness; making more people ‘wonder’ about disability may be the first step for creating change (30 Mar. 2015). Unlimited’s impact on real change seems limited, yet our experiences reinforced for us the conviction that the ‘affective force’ of the arts has a role to play in the process of dismantling ableist hegemony.

32 Our analysis has offered perspectives on the inclusion of people with developmental disabilities in university arts training programs and explored connections between pedagogy, performance, and social change. In a meeting with university gatekeepers at the start of this project, one administrator remarked that even the temporary inclusion we were proposing was just too difficult. Unlimited “without” cast member Mary Chisholm has something to say about that: “What I learned about inclusion? I learned that it’s really, really easy. …Look what we did with twenty-two people of mixed abilities … and with only a couple of months … imagine what we could do in a year … ” (Focus group). We agree with Mary. Anyone can do this, actually. And more should. In providing an example of a mixed ability arts and activism initiative within a university, we invite institutions and communities to dance together towards action.