Articles

Investigating Afghanada:

Situating the CBC Radio Drama in the Context and Politics of Canada and the War on Terror

In 2008, Globe and Mail theatre critic J. Kelly Nestruck made a significant remark about Canadian theatre and the War on Terror, noting a clear absence of stage plays that addressed Canada’s participation. There was, however, a long-running CBC radio drama series, Afghanada, which centred fully on the experiences of Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan. Because relatively little research has yet to be published about the radio series, Lindsay Thistle details Afghanada’s production history, major players, creative processes and goals. She also considers how the radio medium affected the objectives of the series and its ability to represent war, ultimately arguing that Afghanada was inescapably politicized through its relationship with national institutions, its interest in realistic and true-to-life stories, its focus on everyday soldiers, its casting choices and its inclusion of post-traumatic stress disorder. Throughout this investigation, Thistle raises important questions about the politics of dramatizing war while Canada itself was at war. She concludes by observing that while Afghanada avoids an explicit message in support of or against the Canada’s involvement in the War on Terror, it engaged with the political from its inception, through its creation, and in its reception.

En 2008, J. Kelly Nestruck, critique de théâtre au Globe and Mail , faisait une remarque importante au sujet du théâtre canadien et de la guerre contre le terrorisme en soulignant l’absence manifeste de pièces de théâtre traitant de la participation du Canada. Toutefois, la CBC a diffusé à l’époque un feuilleton radiophonique de longue durée intitulé Afghanada qui dramatisait des expériences vécues par des soldats canadiens en Afghanistan. Cette série radiophonique ayant fait l’objet de peu d’études, Lindsay Thistle retrace dans cet article l’historique de la production d’ Afghanada et décrit ses principaux intervenants, les processus créatifs employés et les objectifs de la série. Elle examine également de quelle façon le médium radio a pu affecter les objectifs de la série et sa capacité de représenter la guerre, faisant valoir, en fin de compte, qu’ Afghanada était inévitablement politisée à travers son rapport avec des institutions nationales, son intérêt pour les récits réalistes et véridiques portant sur de simples soldats, ses choix dans la distribution des rôles et sa décision d’aborder le trouble de stress post-traumatique. Au fil de son enquête, Thistle soulève des questions importantes sur la politique de la dramatisation de la guerre à une époque où le Canada participait lui-même au combat. Elle conclut en observant que, si Afghanada évite de communiquer un message explicite pour ou contre la participation du Canada à la guerre contre le terrorisme, la série a contribué au débat politique, depuis sa création jusqu’à sa réception.

1 In his 2008 article entitled “Where’s our war on our stages?” Globe and Mail theatre critic J. Kelly Nestruck identified a clear absence of plays that addressed Canada’s military involvement in Afghanistan. Referring to both plays by Canadian playwrights and plays by international artists that received production runs in Canada, he writes: “While the unpopular Iraq war—which we are not a part of—storms Canadian stages, the Middle East mission in which we have lost 82 soldiers has remained in the wings” (“Where’s”). In fact, prior to 2010 or 2011 and for the majority of Canada’s time in Afghanistan, Canadian playwrights tended to tell stories about the United States and the War on Terror, or Western politics and participation generally. Perhaps most recognized for this approach is Judith Thompson’s Palace of the End, but there is also Robert Fothergill’s The Dershowitz Protocol, Sharon Pollock’s Man Out of Joint, and Guillermo Verdecchia, Camyar Chai, and Marcus Youssef’s The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the Axes of Evil.

2 While Nestruck’s conclusion reflects much of what I’ve found in my own survey of Canadian plays in this period, his objective in 2008 was to point to the absence of stage representations addressing Canada’s participation in the war in Afghanistan. What Nestruck’s article did not acknowledge, however, was the long-running Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) radio drama series Afghanada, which centred fully on the experiences of Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan, and during the final season, their lives back in Canada. Afghanada not only addressed this subject thoroughly, but in so doing became remarkably popular and enjoyed critical acclaim. Given the success and unique position of the series in Canadian theatre and cultural history, it is surprising that Afghanada has not been the subject of more scholarship.1 To address this apparent gap, I will begin by reviewing the show’s production history, major players, creative processes, and goals. I will then examine the inescapable politics in and of the radio series through its relationship with national institutions, its interest in realistic and true-to-life stories, its focus on everyday soldiers, its casting choices, its inclusion of post-traumatic stress disorder, and its selection of radio to represent war. Throughout this investigation, I raise important questions about the politics of representing Canada and war while Canada itself was at war. I conclude that although Afghanada avoided making an explicit message in support of, or against, Canada’s involvement in the War on Terror, it was hardly apolitical; to the contrary, I demonstrate that the show engaged with the political from its inception, through its creation and in its reception.

Afghanada

3 Afghanada was initially intended as a four-part series commissioned by James Roy, an Executive Producer of radio drama at the CBC. It was so popular, however—attracting remarkably large audiences of 300,000 to 600,000 each week—that it was continuously renewed by the CBC for additional seasons (Quill “Afghanada”). The series ended up airing for over one hundred episodes from just prior to Remembrance Day in 2006 until the end of 2011 when Canadian combat forces withdrew from Afghanistan. Afghanada’s popularity among the Canadian public was clear. Toronto Star theatre critic Greg Quill suggests a few reasons for its success: The “writers created vivid internal narratives for the show’s principal characters and a real sense of intense battle conditions, camaraderie, and complex moral, political and personal issues that engaged audiences of all ages and backgrounds” (“Afghanada”). It was equally critically acclaimed, winning multiple national and international awards from the Writers Guild of Canada (“Past Awards”) and the International Radio Festival of New York (“2008 Broadcasting Awards”). Actor Billy McLellan also won the 2012 ACTRA award for Outstanding Voice Performance for his portrayal of Afghanada character Billy “Chucky” Manson.

4 Afghanada was created by four Canadian playwrights, all of whom write for Canadian film and television: Jason Sherman (Patience and The Listener), Adam Pettle (Saving Hope, Rookie Blue, Zadie’s Shoes), Andrew Moodie (Riot and Toronto the Good), and Greg Nelson (The Angel and Republic of Doyle). The creators took turns writing for Afghanada. Sherman, Pettle, and Nelson remained involved for the duration of the series, writing anywhere from one or two episodes a season to as many as ten episodes in some cases. Moodie co-wrote the first four episodes along with the other creators, but left to pursue an acting job shortly after. Nelson and Pettle frequently worked together co-writing episodes while Sherman more often wrote independently.

5 The show also featured numerous guest writers (particularly from season three on) with different experiences in film, television, and theatre; these writers included Paul Aitken (Murdoch Mysteries and Street Legal), Emil Sher (Hannah’s Suitcase), Nicholas Billon (The Elephant Song and The Measure of Love), Dave Carley (Writing with our Feet), and Hannah Moscovitch (This is War and East of Berlin), to name a few. From the outset, Afghanada was a very collaborative project with those involved assuming a variety of overlapping roles. James Roy produced the show in season one, Beverley Cooper produced it in season two, and Gregory J. Sinclair produced it for the remainder of the series, but these producers often acted as story editors and directors, while also featuring the directing talents of Bill Lane and Chris Abraham.

6 In part two of a 2007 “behind the scenes” documentary posted on YouTube by the Afghanada creative team, the creators explain how the idea for the series arose from their participation in a workshop called “Twelve Angry Playwrights.” Inspired by the gathering, Moodie, Sherman, Pettle, and Nelson expressed interest in working together, kept in touch after the workshop, and began to devise ideas including a story about Canada’s role in Afghanistan. Nelson thought it “seemed like a great idea to pitch a series to CBC, which had some really current, sort of newsy content in it” (“Part 2”). The creators were intrigued by the historic nature of Canada’s participation in the war, which represented the first combat mission for Canadian Forces since the Korean War. Part of the interest in this topic stemmed from the fact that although Canada had been involved in the War on Terror since late 2001, the year 2006 marked the start of its more extensive participation. Canadian soldiers moved into Kandahar province and led Operation Medusa, an offensive involving over 1000 members of the Canadian Armed Forces, which became the country’s largest combat mission in over fifty years (“The Canadian Arms Forces”). This expansion of Canada’s role intensified the media coverage of events and the Afghanada creators maintained their goal of engaging in topical and contemporary discussions.

7 The “behind the scenes” documentary also offers valuable insight into Afghanada’s production process (“Part 3”). Each episode began with a brainstorming session by the creators (primarily Pettle and Nelson) and any guest writers. Nelson and Pettle took on more leading roles in the creation and development of Afghanada by also working closely with guest writers to ensure a “unified voice” (Nelson) for the series—the nature of which will be discussed later in this article. In order to develop a general idea for an episode, they focused on two key components: a mission story that looked at the military experience in Afghanistan, and a relationship or narration story that focused more on the lives and thoughts of the characters. From here, the writers did what they called “breaking the story” by forming and shaping its major marks and big movements. The episode was then organized into a list of scenes with a short prose description outlining what happens in each one. This developed into the first draft when they added dialogue, and then to a second draft when parts and lines were cut, changed, or moved around. The actors typically received the script on Friday and moved to a full read-through on Monday when the playwrights made more edits as the episode began to move off the page.

8 Episodes were recorded one scene at a time at the CBC studios in Toronto, beginning with the scenes that required the most people. In some cases, a scene was broken down into multiple layers or overlapping segments. “Wild tracks,” which include crowd sounds, responses to explosions, background noises, etc., were recorded separately and put together with the dialogue later on in the process. Once all of the recordings were complete, the material was sent to the Recording Engineer, Greg DeClute, who edited and reordered the various scenes in accordance with the script. He then passed the recording on to Anton Szabo or Wayne Richards to add sound effects before the final stage where everything was then mixed together and the sound levels were balanced.

9 Afghanada focuses on the stories of three lead characters who each take turns narrating the episodes. Nineteen-year-old Lucas “Chucky” Manson is from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Played by Billy MacLellan, Chucky is the youngest of the group and a stereotypical “boy’s boy” who grows-up and comes into his own throughout the series. Private Dean “The Machine” Donaldson, played by Paul Fauteux, is defensive, rough around the edges and quick to anger, but also occasionally reveals a softer side. The sergeant of the section, Patricia “Coach” Kinsella, played by Jenny Young, hails from Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Coach is dedicated to her job and doing it well, but often finds herself overwhelmed, taking on too much responsibility. The decision to have these characters narrate episodes speaks to the primary goal of the series—telling detailed and realistic day-to-day stories of Canadian soldiers on the ground.

Dramatizing War over the Radio

10 There are a number of reasons—some practical, some artistic—why Moodie, Sherman, Pettle, and Nelson selected radio as the medium for Afghanada. First, radio drama, especially when dealing with complex action, extensive military equipment, and foreign locations, is cheap. The creators knew their idea would be too expensive to make into a TV show and that they would be unable to chronicle events on an ongoing basis as a stage production with a much shorter run. Nelson argues that radio is “a low budget format, but you can do absolutely anything so something that would cost millions of dollars in television or film you could do incredibly cheaply, so really the possibilities are limitless with radio” (“Part 9”). Second, because radio relies on sound, it lends itself more easily to representing what Canadian soldiers experienced broadly in the general mission and acutely, by facilitating the detailed recreation of their auditory environment. Nelson explains: “The fact that we are experiencing everything the way the character ‘hears’ it, and that we are hearing what they are thinking about it all makes us feel very closely connected to the character” (qtd. in Cummings). Third, a weekly radio series is well suited to following current events, and one of the creators’ fundamental goals was for Afghanada to run alongside and react to Canada’s combat mission in Afghanistan. Nelson expands upon this relationship: “the great thing about radio drama is the turnover is really quick. You can write a script and in two or three weeks it’s on the air. So if something big has happened in Afghanistan, you can incorporate that and still be within the so-called news cycle” (“Part 9”). He goes on to say: “We’re able to follow real events pretty closely and to respond very quickly to the mood of the country” (qtd. in Quill “Welcome”). Clearly, Afghanada’s material relied heavily on Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan so when the mission ended in late 2011, the radio series did as well.

11 In addition to the reasons noted by the Afghanada creative team, I see other important consequences of their choice to dramatize war through radio. As actor Billy MacLellan states: “you never get to visually know the people” (“Part 1”). For the actors and the production team, this meant that visual cues and reactions (facial expressions, body language, changes to the setting or environment) had to be communicated by emphasizing the actor’s voice and breathing, and capturing changes through sound only. This lack of visuals became most significant, however, when applied to telling stories of a particularly violent nature with a realistic intent—something Afghanada, with its focus on realism, did often.

12 When stories of war are staged in a realistic manner in a defined performance space (which creates a clearly defined frame), they run the risk of making a spectacle of the violence and horror, and of reducing real experiences of human trauma and violence to artistic products. In her article, “From Event to Extreme Reality: The Aesthetic of Shock,” Josette Féral observes a tendency in contemporary theatre and other performing arts, “where many directors and artists in all disciplines seek to move beyond representation by bringing reality onto the stage, by creating an event, by introducing the spectacular” (51). That is, artists frequently include real photos or video clips showing violent acts in the performance “as is” (52). Féral cautions that placing these “real” moments within a theatrical frame is problematic because “spectators forget the horror and the suffering and the broken lives evoked in the image they are looking at, and shift into observing it as a work of art” (61). Through this shift, “spectators find themselves integrating the event into an artistic process, transforming it into a scene of spectacle, an object of the gaze, protecting the theatricality…and thus necessarily a distance between the observer and the observed” (61). Féral analyzes the ethics of visual representations of violence in film, theatre, and performance art, emphasizing the process of transformation that takes a real violent experience and turns it into an “object of representation” (59). This minimalizing of the real experience is attributed to the visual, that is, to the creation of an image on stage, in film, etc. that is made viewable by the presence of the audience. However, I’d like to look at the flip-side of Féral’s theories and consider what happens when the visual image is absent, and the traditional audience body that witnesses, views, or watches the representation is removed or at least subverted, as was the case in Afghanada.

13 What impact does representing war through a non-visual medium have on the ethical concerns Féral identifies, especially with respect to spectacularizing violence? Listening to a radio drama now tends to be a solitary activity, while theatrical representations often play to a large group of people occupying the same space, watching the same show. This image of an audience collectively viewing a performance that represents violence on some form of a stage, in a defined performance space, showcases the violence in a more literal way than the image of a single listener in her own space unable to gaze upon the acts and images. A large audience not only means that there are physically more witnesses to the violence at a given time, but that the spectacularizing can be read in their reactions to the violence and horror. In Afghanada, the listener must create her own visual images; the details of the characters and scenes will inevitably be imagined differently. This means that the artistic work of Afghanada, which includes violent stories of war, is not commodified and presented in the same way that it is when violent acts are visually represented onstage. Instead, Afghanada ends up promoting a different and arguably more personal experience for each listener, who must actively imagine the violent scenes as they hear them. This intimate listening experience subverts the reductiveness and spectacularization of presenting the same visual image to a group of people simultaneously.

14 Afghanada differs in other ways from the productions Féral critiques, which integrate real images, videos, and so on into performance. While Afghanada was designed to tell realistic stories, it remained rooted in dramatic construction and did not incorporate “real” audio clips of soldiers in Afghanistan. What are the consequences of such a representation of violence? From one perspective, Afghanada’s dramatic construction diminishes these ethical concerns. Since it is not taking real stories of violence and representing them as art, it can be considered less likely to exploit victims of violence. However, the series also raises ethical questions. That is, in any dramatic representation of historical events, the creators must make choices about how to merge real events with invented ones. Inevitably, pieces are taken from different stories and moulded together with fictional details in order to create an entertaining product.

15 To bring these ideas together, the absence of visuals in radio drama can produce a tense and complicated effect. On the one hand, intimacy and closeness are created between the listener and the Afghanada characters (one can listen at home, in a car etc.). On the other hand, a distance also develops between what are clearly dramatized constructions and the “real” experiences of the soldiers. Representing war through radio is, in one way, a step away from spectacularizing violence. Yet a war drama like Afghanada, which takes real events and mixes them with fiction, might also be viewed as a manipulation of tragic and violent stories for entertainment ends. So although radio drama does not create a spectacle of violence, it interacts with the real to create an artistic product. When listening to the show, one senses that the violence, panic, and disorientation are close and real—we hear it as the characters hear it—but at the same time, these events seem abstract and far away because we do not see them. Addressing this intricate relationship between listeners and dramatic representations of war on the radio helps to illustrate how the political occupies a foundational space when dramatizing war simply through the consequences of the different mechanisms of presentation (stage, television, film, radio, literature, etc.).

Afghanada and Canadian Stage Plays about the War on Terror

16 Afghanada was a historic production, primarily because it was one of the only dramatic representations (on stage or otherwise) to chronicle Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan while the events were unfolding. The production took a remarkably different approach from stage representations of the War on Terror where, as Nestruck perceived, there was a noticeable lack of attention paid to Canada’s involvement.2 This is not to say that Canada is never mentioned in plays about the War on Terror from before 2010 or 2011. Sharon Pollock’s Man Out of Joint is about a Canadian lawyer contacted by a former member of the United States military claiming to have proof that the US knew about the 9/11 attacks before they happened. Guillermo Verdecchia, Camyar Chai, and Marcus Youssef’s The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the Axes of Evil references Canada, and takes recognizable societal markers, popular culture, and political figures, or events, and constructs a fictional story similar to the political satire and parody of shows like Royal Canadian Air Farce. However, in these plays, Canada’s participation is presented secondarily, and the leading story documents events in the United States or the Western world more broadly. Even in Don Hannah’s While We’re Young, where the focus is on Canadian stories of war from six different historical periods, Canada’s role in the War on Terror is marginal. James Forsythe’s Soldier Up (currently unpublished) is the only stage play I’ve found from this period that consistently and overtly depicts the experiences of Canadians. Soldier Up was produced by the Pet Projects Theatre Company and performed in 2008 at the Evans Theatre of Brandon University in Manitoba. It tells stories of soldiers that served in Afghanistan based on interviews that Forsythe conducted at Canadian Forces Base Shilo.3 It is important to make clear that the majority of these plays are highly critical of the War on Terror and Western governments, and they attempt to confuse and challenge the mainstream version of events. We see a negative representation of the West and/or the United States, creating a, perhaps, controversial final product that subverts the rhetoric of the War on Terror used by governments and in the media to generate public support.

17 What might we interpret from this short survey of plays produced alongside Afghanada? Historically, governments at war have been concerned with maintaining or gaining support and presenting what they deem to be a desirable narrative of events. Might a focus on the United States and Iraq, or general Western ideologies reflect pressures felt by artists to “toe the line” during times of war? Rather than directly expressing a strong anti-war critique of Canada’s involvement, might playwrights use Britain, the United States, and Iraq to metonymically address Canada’s participation in Afghanistan or what they perceive to be, its complicity in regards to Iraq? This implication grows stronger when two things are considered: the notable increase in the number of plays written about Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan after Canada’s combat mission ended,4 and the context and subject matter of Afghanada, which strives in a quite different way to shift the focus away from such politics and critiques.

An Emphasis on Realistic and True-to-Life Stories

18 While making Afghanada, the writers and the production team made a concerted and consistent effort to get the stories “right”—not to be confused with making them “real.” The series sought out two military consultants to review scripts and ensure that the language, military terms, character reactions, training techniques, and weaponry were detailed and representative of military experiences. As outlined in part six of the documentary, finding the military consultants was not easy; Nelson states: “the military is incredibly protective of their stories” (Nelson). They eventually found Scott Taylor, a former military commando, and the editor and publisher of a Canadian military magazine, Esprit De Corps. Taylor was able to provide information about terms, attacks, and types of weapons, but he could not fully relate to the experiences of the characters in Afghanada because he occupied a leadership position and hadn’t been involved in the war in Afghanistan. Because of this, and even more to their goal, the producers sought someone of a similar rank to the characters, who had been involved in Afghanistan. They were relieved to eventually find an individual who was willing to participate anonymously. Nelson speaks to the high degree of accuracy that they were looking to capture through the use of these consultants:

The military consultants, in their advisory and editorial roles, significantly impacted the material of each episode. Young explains that prior to a read-through, “usually there’s a gazillion changes because the military consultants will have looked at the script and decided what is TV speak and what’s actually accurate, we try to stay as accurate as possible” (“Part 3”).

19 Afghanada’s production style aimed to offer an accurate depiction of the soldiers’ environment and experiences. For example, Quill refers to the “geekily accurate” sound effects (“Afghanada hits”), some of which include an array of guns and weapons (C6 general purpose machine gun, C7 assault rifle, C9 machine gun, etc.), different military vehicles and equipment, and multiple types of bombs and explosives depending on the details of the situation. This was done to maintain what Quill calls, Afghanada’s “radio vérité” (“Welcome”), presumably a playful extension of cinema vérité, a naturalistic French film movement in the 1960s that “showed people in everyday situations with authentic dialogue and naturalness of action” (“Cinema Vérité”). Radio vérité audiences hear the speaker’s personal ideas and reactions, and an intimacy is created between the listener and speaker—something also developed in Afghanada through the characters’ narrations. Rather than including unrealistic dialogue, particularly during action scenes, the voiceovers allow the characters to “think aloud” and let “the listener in on their impressions, movements and feelings” (Quill “Welcome”). Although this technique is obviously not realistic in itself (we cannot hear what people think in real life), it creates a sense of realism as we both experience events through the soldier’s point of view and hear their inner thoughts.

20 The cast and creators argue that Afghanada’s soldier characters are so true-to-life that they parallel actual Canadian soldiers fighting overseas. Sinclair states: “Our audience has developed very, very close relationships with the soldiers, with the characters and again, by extension, with the real soldiers whom most Canadians would actually never meet” (“Afghanada ends”). Even the creative choices made for different episodes were conceivable situations that soldiers might encounter. Notably, the series recorded one episode where a private shoots a man who he suspects is a suicide bomber, and just prior to the episode airing, a Canadian soldier in Afghanistan had experienced the same situation. Roy concludes: “we kind of intersect with the real world in some funny ways with this series” (“Part 9”).

21 Through its reflection of the experiences of the soldiers, Afghanada also aimed to educate the listening public. Roy wanted to share perspectives about the soldiers’ daily lives that were missing in the news coverage. He says: “One of the hooks we felt we had was that nobody actually knows what happens at the grunt level in the armed forces” (“Part 7”). The news, he explains, gives “no real sense of the day-to-day, moment-to-moment operation, and that’s really one of the main points of the series” (“Part 7”). Furthering its earlier goal of achieving a high degree of accuracy in its representations, the series integrated a great deal of military terminology that is spoken quickly in combat or action scenes, with which most Canadians would be unfamiliar. A few examples include BAT (big ass tent), ETT (embedded training team), LAAGER (vehicles pulled into a circular defensive position to form an encampment) and pencil neck (a type of C8 machine gun for shorter range fire) (“Glossary”). Breaking down the terms, including a definition or providing an explanation in the episode itself would detract from the show’s realism by disrupting the listeners’ intended observational position. In order to combat this challenge and still speak to the educational goal, the Afghanada website (which is still active online) includes a glossary of over seventy technical, code, slang, and military terms (“Glossary”). This allowed the writers to maintain accurate dialogue, while still giving audience members an opportunity to learn about Canada’s involvement.

Realism and Politics

22 Earlier in the article I spoke of Nelson and Pettle’s involvement with guest writers to ensure a unified voice for the series and its characters. In tandem with this emphasis on representing the conflict realistically, they also sought to reflect an apolitical stance as they developed the show’s voice. Nelson writes:

Those involved with Afghanada distanced the series from the politics of the mission. Roy states: “We haven’t set out to get in the faces of politicians” and instead, we want to “tell the story of the people who are actually doing the work [. . .] without getting into policy issues and the bigger picture” (qtd. in Quill “Welcome”). Jenny Young agrees: “It [Afghanada] didn’t try to take any sides. I think it just stayed down the middle, showing us not the politics of it as much as what it means for Canadian soldiers to be there” (“Afghanada ends”). Nelson echoes this sentiment: Afghanada is about “soldiers that didn’t have any of the policy angle, any of the big picture, they didn’t care about the politics. Just a very human story about these young guys that Canada was sending over to Afghanistan to all of a sudden, fight a war” (“Part 2”). With statements like these, the creators suggest that Afghanada starts to replace political positioning with realism and education.

23 This distancing from politics, however, is not so clear cut. In their introduction to the volume New Canadian Realisms, Roberta Barker and Kim Solga challenge the idea that realism negates or is removed from politics and instead show how realism in Canadian theatre has an important political history. They caution against a polarized approach that suggests that dedication to realism means disengagement from politics and invite readers “to think in fresh ways about the multi-faceted dynamics of stage realism and its ongoing aesthetic and political potential for Canadian performance” (xi). In the second half of this article I respond to Barker and Solga’s revisionist call by investigating the politics in and of Afghanada alongside its commitment to realism.

24 On the one hand, the creators’ decision to abstain from a clear pro- or anti-war view can be read as pragmatic. Canada’s role in the War on Terror remained an emotional and highly contentious issue throughout the show’s run. The first Canadian public opinion poll taken mid-September 2001 reported that seventy-three percent of Canadians “were strongly prepared to join the U.S. and declare war on international terrorism” (Kirton and Guebert 14). However, despite this initial support, the first Canadian casualties in 2002 quickly called the mission into question, and by 2006, when Afghanada began airing, support for the war was split (16). In 2010, public opinion was still deadlocked; forty-seven percent of Canadians supported the mission in Afghanistan while forty-nine percent opposed it (“2/24/10”). Furthermore, late in 2010, as the war neared its end, headlines read: “Canadians Divided on Assuming Non-Combat Role in Afghanistan” (“12/13/10”). Given this ideological split, the creators’ efforts to distance the show from politics might be viewed as a politically correct and cautionary attempt to avoid alienating half the listening public. Roy may also have been correct when he spoke of Afghanada’s hook being its ability to show what happens on the ground level—a perspective that was missing from the coverage of events in traditional news media. I also wonder if the support for Afghanada and its popularity reflects a separation, on the part of the Canadian public, between their opinions of the mission and their support for the soldiers. That is, Canadians were clearly and consistently split on the politics of the mission and its value, but perhaps less so on recognizing the soldiers and their difficult experience. Although I’ve yet to find a poll or statistic that takes into account such a distinction, I do think it is worth mentioning that eighty-two percent supported the decision to bring Canadian troops home when the mission ended (Leung).

25 On the other hand, the politics surrounding Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan ran deeper than pro- or anti-war views. Although the CBC and the Afghanada creative team avoided a firm pro- or anti-war stance, it was impossible for the series to stand outside of politics and I argue that exploring the ways in which Afghanada engaged with and was engaged by the political offers the most productive lines of inquiry into the series, and helps to illustrate its unique interaction with Canada and the War on Terror. When looking at the content of Afghanada and moving passed a simplified pro- or anti-war expression, the foundational politics of the series become clear largely because of its focus on realism. In fact, this close integration of politics and realism distinguished the series from staged representations of the War on Terror during Canada’s involvement.

26 In times of war, the soldiers on the ground embody and enact, in a very physical, tangible, and palpable way, the larger conceptual, ideological, and policy-based ideas of the mission. Their collective day-to-day actions and responses ultimately form the war, even if not every action is outwardly political. In her essay, “Affect Management and Militarism in Alberta’s Mock Afghan Villages: Training the ‘Strategic Corporal,’” Natalie Alvarez expands upon this idea of the everyday soldier as a political player as she shares her experience of observing simulated military training exercises intended to prepare soldiers for their time in Afghanistan. Alvarez introduces the notion of the “Strategic Corporal,” highlighting precisely how the everyday Canadian soldier in Afghanistan is highly political. Soldiers learn complex “Rules of Engagement” that “govern[…] his or her relations with local nationals in this counter insurgency mission” (18). The Rules of Engagement prepare the soldier for a diverse range of situations including “high-intensity counter-guerilla warfare,” “humanitarian aid and trust building with location nationals,” and “arbitration between warring factions” (20). Therefore, with its interest in showing soldiers’ day-to-day, minute-to-minute experiences, Afghanada can be read as an acute performance of these politics. In soldiers’ frontline role, “they hold the power to influence not only the ‘immediate tactical situation,’ but the larger operational, strategic and geopolitical situation as well” (20). Alvarez goes on to note that training does not exist outside of politics and “the modulation of affect in military training is historically contingent and inextricably tied to shifting geopolitical forces” (19). Soldiers make decisions that are reported on and scrutinized, condemned or celebrated, and which serve as concrete examples of the politics of the mission—even if they were not intended as such.

27 Afghanada engages with the challenging and complicated dynamic that Alvarez details. For example, in episode 24, Dean and Lucas make friends with Samir, a soldier in the Afghan National Army (ANA)—a friendship that developed out of the political circumstance, but one that is based on individual human-to-human emotion and connection, and one that could exist outside of the war. The Canadian troops work with Samir’s ANA unit, led by Lieutenant Khalid, to provide security for a Jirga (a meeting of village elders). During the Jirga, however, it is revealed that Samir has been working with the Taliban and providing them with important information. Lieutenant Khalid interrogates Samir violently, trying to get information from him. Dean and Lucas intervene as they struggle to come to terms with the truth about Samir. In this situation, we see how the friendship affected/influenced the Canadians’ approach to the treatment of Samir, and by extension made a very political statement about how Canadians expect suspected terrorists to be interrogated. Had the suspect been someone other than Samir, someone with whom Dean and Lucas did not have an emotional connection, they may not have felt the need to intervene or perhaps might have tried to get information from the terrorist themselves.

28 The notion of seeing the political in the everyday soldier is also telling when applied to Afghanada’s extensive depictions of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related emotional challenges throughout the series, but especially during the final season when the soldiers return home. In episode 89, for example, Sergeant Casper Jakes begins seeing a psychiatrist after a woman with whom he was having a relationship, Sergeant Hannah Crowe, dies because of an IED (improvised explosive device). Later on in episode 97, Casper develops an addiction to Ativan and alcohol, and suffers from anxiety. Still, in episode 92, after the unit travels to Cyprus for a post-mission debriefing, Dean experiences insomnia and anger issues. Chucky, too, resists getting back into his normal life in episode 96, and jeopardizes a new romantic relationship.6 If the soldiers are an enactment of the politics of the mission, I would argue that the issues addressed in the depiction of their PTSD, including guilt, responsibility, exhaustion, anger, fear, panic, etc., symbolically represent and parallel larger political, ethical and moral concerns of Canada’s involvement in the War on Terror.

29 These concerns can be seen in the depiction of PTSD in a Remembrance Day Special in season two, which was taped live at the Canadian War Museum—an event that I will return to later. In this episode, Sergeant Pat Kinsella receives the Medal of Military Valour after saving the life of Private Dean Donaldson. Pat begins to act out of character, snapping at those around her, and avoiding questions about the event that led to her medal. Suspected of having a stress injury and PTSD, she is sent to talk to the armed forces’ psychologist. The episode intersperses the therapy session with Pat’s own flashbacks of the events. Initially, she refuses to answer the psychologist’s questions and eventually we learn that Pat’s PTSD stems from a situation that involved a young Afghan soldier, Wahid. Wahid was part of a group from the Afghan National Army who arrive for training with the Canadians. Pat takes a particular liking to him; after hearing about his difficult childhood, she is impressed by his sense of humour. She remarks that he seems to be “full of hope.” He accompanies the group on what should be, a routine patrol, but instead, they end up under fire after the Taliban surround the Canadians in a farmhouse. Dean gets separated from the group, and Pat devises a quick plan that puts herself in danger, but ultimately saves his life. Pat initially lies to the psychologist about the second half of the event, but goes on to confess that when leaving the farmhouse, Wahid fell behind. Still under fire and with a shrapnel wound to her face, she was forced to leave him and he was killed. Her guilt is at the centre of her PTSD and she struggles to come to terms with the way she abandoned Wahid. She argues that she should have turned back to get him, that she could have dragged him, thrown him over her shoulder, and makes numerous references to the last look of terror she remembers on his face.

30 The psychologist encourages Pat to forgive herself and let go of her guilt. Alluding to the immense political weight and consequence of her day-to-day life in Afghanistan, Pat responds: “You want me to let go? I’m sorry but that is the friggin’ funniest thing I have ever heard. Lady, since the day I got here, I’ve been doing everything I can to not let go, to friggin’ hold on, to somehow keep it together.” Her emotional outburst continues: “Let me ask you something. What do you think would happen if the next time I’m out there in the shit, I’m mean in the shit, getting shot at with the lives of how many friggin’ people depending on me, what would happen if I let go, if I burst into tears and felt something, what do you think would happen?” The psychologist once again tells Pat that it would be healthy for her to let go and work through her feelings. Pat’s response acts as the emotional climax: “It is not good, it is not friggin’ good, cause I have to go back out there, do you get that? I have to go be a friggin’ soldier out there and soldiers don’t get to feel, you understand me? We do not get to feel.” After the session, Pat receives her medal and imagines Wahid in the crowd. By the end of the episode, she’s begun to move past her guilt with the help of the psychologist and her fellow soldiers. In this example, the complications of personal and professional roles are once again blurred. That is, the political events of fighting the Taliban and working with the Afghan National Army are impacted by the individual relationship Pat forms with Wahid. Pat’s affection for Wahid (and his positive and optimistic personality) might be read as a parallel to the Canadian mission as a whole, initially hopeful to bring positive change to Afghanistan—a sentiment that is replaced by a much more complicated reality in Pat’s inability to save Wahid. Though both Dean and Wahid were her friends, her ability to save Dean’s life but not Wahid’s has important political consequences as it relates more broadly to Canada’s potential to help Afghanistan. These overlapping and embroiled personal struggles and political events create depth and complexity in Afghanada.

Casting and Politics

31 Politics and realism also intersect in the representation of the Afghan characters. Nelson writes: “We always knew that we would require Pashto and Dari speaking Afghans (primarily Pashto since the series is set in Kandahar province).” They believed that “hearing the language would be crucial to giving the series a sense of authenticity. So it was very much an obvious choice” (Nelson). To this end, the series included Afghan-Canadian actor Khan Soroor, who reportedly assumed the role as the “official consultant on Afghanistan, its people, customs and language. He speaks Hindi, Urdu, Dari and Pashto” (Quill “Welcome”). From the start, the radio series also used non-actors from Canada’s Afghan community including members of Soroor’s family “to give authenticity to the voices of non-military characters” (Quill “Afghanada”). Hearing native speakers of the language spoke to Quill’s early praise of Afghanada’s radio vérité.

32 Yet there are aspects of the series’ casting that raise questions about how “authentic” representation functions politically. Pakistani-Canadian actor Ali Rizvi and IranianCanadian actor Anousha Alamian each played a variety of roles throughout the series from villagers to soldiers to storekeepers. Ali Rizvi jokes that he’s “the token brown guy” and plays “eight different Afghan guys” (“Intro”). This “close enough” casting of Pakistani and Iranian actors conflates identities, dilutes ideas of authenticity, and presents a broad Middle Eastern “Other.” Questions of authenticity are also raised in the diverse set of characters that each actor is asked to play, with the only qualifier being the actor’s (sort of) Afghan-ness.

33 These concerns, however, are not new, nor are they unique to Afghanada. The concept of authenticity in dramatic work, which at its base is a form of creative representation, becomes highly problematic. What makes a portrayal authentic? How can concerns of authenticity (defined as true and accurate, real and genuine) be reconciled in drama and theatre, which are constructed by antonyms of authentic (imitation, representation, portrayal, pretend, artificial, illusion)? Furthermore, who and/or what determine whether a portrayal is authentic? Is it based on similarities between the characters and the actors that play them? And if so, does a necessary contextual match subvert the art of acting? Is it a wellresearched script that leads to an authentic portrayal? Is it a script written from first-hand and personal experience? And if so, does that limit the creative possibilities for writers? Where and to what end is authenticity even important in drama? How does it influence the representation of issues of social-justice and traditionally othered perspectives? How might Afghanada’s attempts at authenticity diversify (to an extent) the stories told and the people who tell them, while simultaneously raising these concerning issues of “close enough” casting? What are ethical alternatives when “authentic” voices are not an option?

34 These complex questions are difficult to answer and taking up all of them would require much more space than I have here; however, in the interest of continuing to explore how the political operated through ideas of realism in Afghanada, I will offer some preliminary thoughts on the series’ casting choices and ideas of “authentic voices.” Afghanada appears to take neither a colour-blind nor an authentic casting approach, but rather mixes the two, and perhaps this is where the real crux of the issue lies. Afghanada cites realism as a founding idea of its presentation, and within this declaration it sometimes makes non-realistic production choices like the decision to use Pakistani actors to play Afghan characters. How can we read and understand this decision? Can it be viewed as a best effort attempt to find and include authentic voices based on what was available to the creators? Or, is it simply a problematic conflation of traditionally othered identities?

35 To expand upon these ideas, I refer to Natalie Alvarez’s “Realisms of Redress: Alameda Theatre and the Formation of a Latina/o-Canadian Theatre and Politics,” in which she discusses ideas of authentic casting and colour-blind casting as they relate to realism and performance, and to broader politics of the theatre industry in Canada. She cites a particular example where Marilo Nuñez, a Chilean-Canadian, created Alameda Theatre to foster opportunities for Latina/o-Canadian artists after she was the only non-white actor cast in Factory Theatre’s 2003 production of Carmen Aguirre’s Refugee Hotel (which tells the stories of Chilean refugees) (146). Yet years later in Alameda’s own 2009 production of Refugee Hotel, actors from Columbia, Argentina, and Mexico were cast to play the Chilean characters (156). Alvarez discusses the convoluted and contradictory approaches to and outcomes of such casting politics largely through ideas of iconicity, which she defines as “a sign vehicle that denotes an object…it is like that thing and used as a sign of it. Its likeness serves to summon into the onlooker’s imagination the idea of a similar object” (154). For Alvarez and in this discussion of Afghanada, the “catch-22” of iconicity and ideas of authentic casting is significant. For “minoritized subjects, iconicity provides a vocabulary for identifying what is wrong when, for example, a heterosexual woman plays a lesbian or a white actors plays a Latino” (155). However, “the appeal for continuity between actor and character in the logic of iconicity runs the risk of re-entrenching essentializing representations and obfuscating difference” (155). Ideas of iconicity and the similarities between the conflation of countries, cultures, and ethnicities from Latin America in the Alameda example, and those of the Middle East, in the case of Afghanada, are clear. This generalization is not ideal, yet it appears that the creators considered it more acceptable than casting white actors, as was made clear in the controversy that arose from Factory’s production. These examples suggest measurements of authenticity or degrees of authentic representation. This implied ranking system is problematic to me for a number of reasons, but primarily because it seems to create a scale for authentic cultural/ethnic representations wherein some cultures are considered “closer” to authentic than others. Furthermore, with an emphasis on this scale of ethnic authenticity, there appears to be a ranking of types of authenticity. In Afghanada and in the Alameda example, ethnicity trumps authenticity of age, class, gender, physical body, religion, education, life experience and so on.

36 In the examples addressed, I would argue that there is more to authentic ideas of casting than ethnicity alone, although ethnicity is the category that seems to preoccupy theatre makers and scholars the most. Perhaps the emphasis on ethnicity has to do with the visual performance of theatre and the embodied presentation of such ideas in the actors. Perhaps radio’s lack of visuals and its auditory presentation is why Afghanada’s emphasis was placed on a linguistic realism rather than an ethnic one. In my research on Afghanada, I’ve found numerous discussions by the creators and actors about the show’s interest in realism and the particular languages of the different regions in Afghanistan, but I have not found any comments that speak to the casting decisions from the point of view of the actors’ ethnicity.

37 Both these examples illustrate that authentic casting cannot be as simple as saying one must be the “same” (age, ethnicity, gender, etc.) as the character they play. These examples also illustrate how Afghanada’s casting choices, although very much rooted in dramatizing events realistically, raise important, controversial, and political questions about what it means to represent something or someone realistically and/or authentically. This ethnic and/or cultural conflation of actors from different countries in the Middle East parallels larger concerns about the conflation of such countries in the dominant rhetoric of the War on Terror used by Western governments and connects “real” politics to the fictional representations in the radio series.

Afghanada and National Institutions

38 The politics of Afghanada continue to be felt through its connections to national institutions, most notably through its close relationship with Canada’s national public broadcaster, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Outlined in the 1991 Broadcasting Act, the CBC must incorporate “a wide range of programming that informs, enlightens and entertains.” This programming should be “predominantly and distinctively Canadian, reflect Canada and its regions to national and regional audiences, while serving the special needs of those regions.” It should also “reflect the multicultural and multiracial nature of Canada” and “be made available throughout Canada by the most appropriate and efficient means.” Even still, it must “contribute to a shared national consciousness and identity.” Programming as whole must also “be in English and in French, reflecting the different needs and circumstances of each official language community, including the particular needs and circumstances of English and French linguistic minorities.” (“Mandate”).

39 In theory, Afghanada’s association with Canada’s national public broadcaster appears to bring with it a sense of authority, as in attempting to fulfill its challenging mandate, the CBC has built its biggest successes around news programming, documentaries, live sports, special events, and historical programming. In practice, however, this sense of authority is complicated by a variety of factors, most notably the CBC’s reliance on changing federal governments for much of its funding and its inability to attract consistently large audiences. In this juxtaposition of its intended role with its dependence on government funding lies political consequences for the shows it makes.

40 Is it conceivable to imagine a regular series on CBC radio or television that was highly critical of Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan while the events were unfolding (in a manner similar to Canadian stage plays about the United States and Iraq), given that much of its funding comes from the subject of its critique? Equally so, is it plausible to envision a show that depicts only sensationalized and glamourized merits of the war in an attempt to drum up support while so openly subverting the CBC’s attempt at responsible national broadcasting? These questions are not rhetorical, but allude to some important complications. Did the Afghanada creative team strive to be apolitical because it made smart fiscal sense? From an abstract perspective, one can answer yes to this question. But in reality, the CBC has often struggled with the expectations and pressures associated with its status as a national public broadcaster, as well as with the execution of its mandate. For example, the CBC faced challenging questions about its treatment of Canadian history and politics when it aired Canada: A People’s History (2000), a seventeen-part historical series chronicling Canadian history from 15,000 BC until the present day. The series was criticized for recasting events to fit a nationalized narrative.7 The CBC was also questioned about The Greatest Canadian (2004), a live reality TV series wherein current Canadian celebrities made the case for naming a particular historic figure The Greatest Canadian. One of the show’s most critiqued aspects was its lack of diversity in the top ten candidates, which contained no women and only one non-Caucasian in David Suzuki. So although, at first-glance, the CBC seems to strengthen Afghanada’s ties to accurate, realistic and true-to-life stories, upon closer examination, it is clear that the CBC equally suffers from positioning and bias. In its desire to offer a nonpartisan presentation of events, Afghanada capitalizes on the superficial association of the CBC with truth and accuracy, and the weight it carries in Canada. When looking closer, however, the context of the show’s production at the CBC carries with it the history of these politicized representations and situates Afghanada among them.

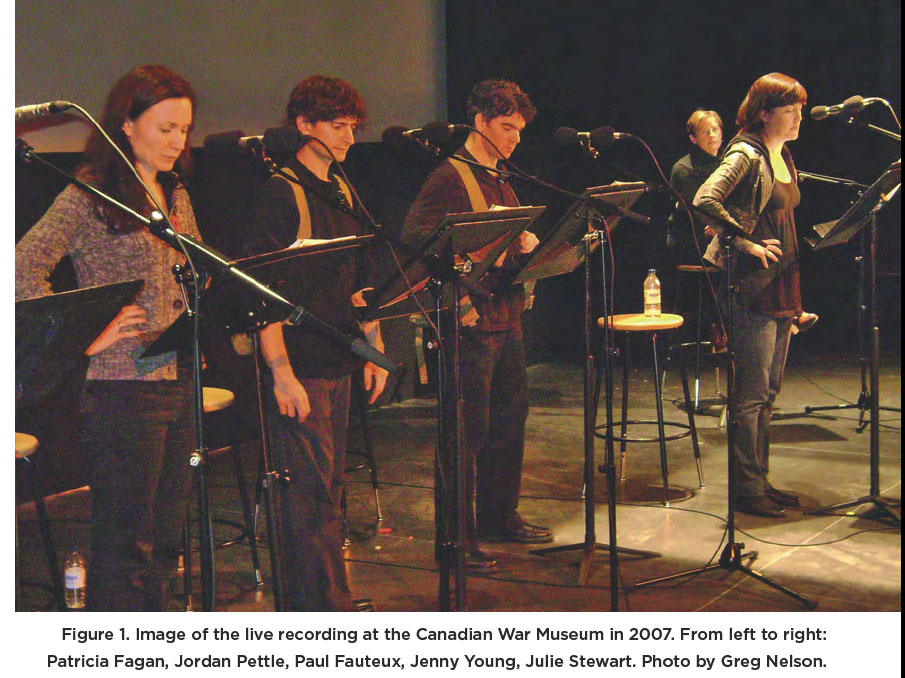

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 141 The issues raised about the CBC, Afghanada, and the treatment of history continued to be felt through the series’ relationship with another national institution, the Canadian War Museum, when it recorded a Remembrance Day special live at the museum in 2007. The live taping was presented together with a special historical exhibition called Afghanistan: A Glimpse of War, which included news clips, personal stories from Canadian soldiers, military equipment, wreckage from the 9/11 attacks, photographs of war and material from recent elections in Afghanistan.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 242 In the summer of 2007, the museum approached the creators of Afghanada with the livetaping idea and the CBC asked Gregory Sinclair to produce the event, which is how he became involved with the series. Nelson remarks that “the challenge we faced was the live nature of the event” (Nelson). Afghanada had an elaborate production process for its immersive soundscapes that was difficult to reproduce outside of a studio. To address this, the combat scenes of the episode were recorded prior to the taping and then played during the event with some sound effects for the other scenes created live (Nelson). It was necessary to create a script that could move back and forth (Nelson)—something the series accomplished with Pat’s session at the psychologist and her memories of the events. Members of the public were able to attend a rehearsal earlier in the day and the live taping, and both performances sold out.

43 The CBC and Afghanada’s decision to record live at the museum, combined with the choice of the museum as the host for the dramatic recording, facilitated complex discussions of this event. Using the museum as the performance site played upon its associations with the archival, the real, and the historical, and sought to tie Afghanada to these ideas and to the successes of the CBC. The pairing of the exhibit with the live taping also emphasized Afghanada’s desire to educate the public; the press release for the event suggests that the radio series was “mirroring events” (“Afghanada, a radio drama”). However, museums generally are not removed from ideas of narrative and construction. They equally rely on a staging, a selection, and a performance of a chosen, created, and persuasive narrative supported by the materials of the exhibits that in this case, was presented to Canadians young and old, and immigrants and tourists. As Susan Bennett argues, theatres and museums have significant similarities. They provide “entertaining and educational experiences that draw people to a district, a city, a region, and even a nation. As components of the cultural landscape, theatres and museums alike play a role in creating and enacting place-based identity” (3). For the Canadian War Museum, hosting a live taping of Afghanada opened up an opportunity to participate in contemporary debates and discussions where it was able to generate interest in Canada’s war history by capitalizing on the popularity of the radio series. For Afghanada, the live taping pushed the series towards historical docudrama, as the actors literally performed among “real” pieces of history. As a CBC production, Afghanada had a clear interest in national discussions and recording an episode at a national museum located in the nation’s capital drew attention to the series in such a light. This joining of Canada’s national broadcaster with the country’s national war museum also pushed Afghanada (as a product of the CBC) towards a passive complicity in state-sponsored representations of war—a complicity that becomes clearer when the context of this event is addressed.

44 The special exhibition and live taping of Afghanada came not long after the controversial parliamentary decision in May 2006, where by a count of 149-145 Members of Parliament voted in favour of extending the mission in Afghanistan until early 2009. The Canadian War Museum exhibition was part of a series of public programs intended to “bring greater understanding to Canadians of the war in Afghanistan” (“Afghanada, a radio drama”). At a time when the Canadian public was so divided in their support of the war, Afghanada’s ability to present dynamic images of soldiers appears to have influenced members of the Canadian public. This type of influential and emotional representation seen in Afghanada is enhanced by the series’ relationship with the Canadian War Museum, and the national narratives that the museum produces and participates in. Fans of Afghanada most frequently complimented the series overall for its engaging storylines and lifelike characters with whom they could connect and identify. On his blog, fan Andy McNab says he’s “addicted” because “it’s like you’re there. It [sic] also got a very human approach and once you get to know the characters you feel you live through the events with them.” Another fan writes that “it’s the human drama that really grabs me. This ain’t Melrose Place, folks. This is a drama about people with actual real world problems, people who get themselves stuck in very bad situations over and over again because it’s their job, and not a job that they can quit” (Squirrel). Might such a compelling portrayal have the potential to engage the public in the worth of the war? Or, at least limit those undecided from outwardly opposing the war? It appears for some fans, this is the case. One reviewer writes: “I am anti-military, well I was. Listening to this has humanized the whole Afghanistan experience” (“Best Radio Drama”). Another reviewer confesses: “I’m not a militaristic kind of guy. But this program is amazing in the way it makes the military experience in Afghanistan very real, very human” (“Afghanada Season 1”). Even still, one blogger writes: “I can say that the power of this show has made me feel more compassion for the individuals in our armed forces than all of the traditional news reporting put together” (McQ).

45 The persuasive impact of Afghanada (intended or not) speaks to the power and influence of creative and cultural representations of war, especially during times of war. In The Militarization of Inner Space, Jackie Orr discusses the use of language and rhetoric by the Bush administration, and its subsequent dissemination in media, politics and culture in the United States. She notes a particular moment where at the start of the War on Terror, Bush referred to Americans as soldiers (452). This verbal and linguistic proclamation militarized the lives of every day civilians, integrated all Americans into the war effort and positioned them as the target of terrorist attacks, which in turn, Orr argues, justified American military action and the “production of violence” (456).

46 To be clear, I use Orr’s example not to suggest that Afghanada was explicit propaganda, but rather to highlight the way that language (in the Bush example it was one short sentence) can affect a society, particularly one involved in a war. If Bush’s statement was able to so drastically shift the average American’s position on the War on Terror, then compelling dramatic portrayals and representations, which are more in-depth, detailed, and consistently connecting emotionally with listeners, must also have such an ability (even if it is not a goal of the creators). In fact, although Afghanada’s affective potential was something that many fans celebrated, it was also the most critiqued aspect of the show. A blogger complains it’s “an appalling insult to Canadians, particularly those (like me) who don’t think we should be in Afghanistan” (“Sick of”). Another writes: “The bombs, the killing, the narrator letting out messages on how wonderful being in the military is? It’s too much propaganda” (Mispon).

47 The involvement of the series in these discussions of the representation of violence, posttraumatic stress disorder, authentic ideas of casting, and so on highlights how its emphasis on and interest in realism was inevitably political. Politics were interwoven in the series’ creative choices, its focus on education and realism, and its connections to Canadian national institutions. I might also suggest that politics were embedded in the decision to use radio to tell these stories as well. Radio possesses an ability to intervene in questions of war and violence in ways that visual media like television, stage, and film cannot (because of the concerns addressed earlier in this article whereby violent stories are reduced to an artistic product). As demonstrated in the blog posts by both fans and critics, Afghanada involved Canadians in discussions of Canada and the War on Terror for much of the conflict’s duration.

48 Although Afghanada’s creators could not have predicted the extent of its immense popularity, I believe that radio as a medium was a significant factor in its long-term success. Radio opened up the opportunity for consistent engagement with Canada’s combat mission, once again in ways that other media could not for a variety of practical (high costs of TV and film, and short runs of plays) and artistic (intimate experience of the listener and ongoing reaction to Canada’s involvement) reasons. Afghanada was certainly unique in its timing, format, and subject matter. It was examining Canada and the War on Terror explicitly and in detail, while stage representations dealt with Western involvement generally. If anything, the success of the series illustrates the interest Canadians have in discussions of Canada, identity, and war. As Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan and the War on Terror continues to move further away from a current event to become a more historical one, it will be interesting to see what new interventions artists make. Such work will no longer be about reacting directly to news events, policy decisions, public opinion, or Canada’s changing role, but will instead be about addressing how the events might (or might not) be understood, remembered, mythologized, and integrated into Canada’s national narrative.