Articles

Around the Backside:

Productive Disbelief in Burning Vision

The work of Vancouver-based Métis playwright Marie Clements has often been commended for its emphasis on the connections that inhere among people and places, times and spaces. The time-space conversations of Burning Vision , one of the most spatially and temporally diverse of Clements’s works, have thus far been explained in terms of their ecological and indigenizing effects. While revelations of connectivity and windows opened onto alternate conceptions of spatio-temporality are significant results of the intercultural moments where Clements brings discrete times and places into conversation, it is also useful to acknowledge another, more immediate result of such dialogues: audience confusion, alienation, and disbelief. Such confusion points to a significant but as-yet unaddressed aspect of the Burning Vision : the way the play’s materiality works against its fiction, impeding audience immersion in the story unfolded. This article draws out this conflict through a phenomenological approach that illuminates how the refusal of the work’s material reality to disappear behind its fiction—to slip around the backside of the frontside illusion—prompts a productive kind of disbelief that structurally underlines the work’s arguments for interconnectedness.

L’œuvre de Marie Clements, dramaturge métisse vivant à Vancouver, a souvent été louée pour l’importance qu’elle accorde aux liens entre personnes et lieux, époques et espaces. Les conversations sur le temps et l’espace dan Burning Vision , l’une des pièces de Clements les plus diversifiées sur le plan du temps et de l’espace, ont été explorées jusqu’ici en fonction de leurs qualités écologiques et indigènes. Si on a souligné l’importance des connexions et les conceptions différentes de la spacio-temporalité qui résultent des moments interculturels où Clements fait dialoguer les temps et les lieux, il faut aussi mentionner l’effet immédiat que créent ces échanges!: la confusion, l’aliénation et l’incrédulité du public. Cette confusion révèle un aspect important de Burning Vision dont l’étude a été jusqu’à présent négligée : la façon dont la matérialité de la pièce va à l’encontre de sa fiction et pose un obstacle à l’immersion du public dans le récit qui se déroule. Dans cet article, Alana Fletcher analyse ce conflit en adoptant une approche phénoménologique qui éclaire la façon dont la matérialité de l’œuvre refuse de disparaître derrière sa fiction—de passer derrière l’illusion qui est créée devant—et provoque une incrédulité qui mine le thème de l’interconnexion dans la structure même de l’œuvre.

1 The work of Vancouver-based Métis playwright Marie Clements has often been commended for its emphasis on the connections that inhere among people and places, times and spaces. In his introduction to Theatre Research in Canada’s dedicated issue on Clements (2010), Reid Gilbert foregrounds Clements’s propensity to treat “a number of overlapping themes at the same time, simultaneously locating both the differences and the links among the[m]”; to employ “dreamscapes moving through time and space”; and to reflect numerous “interconnected subjectivities” (v-vi).1 Similar sentiments have been expressed by a number of critics who laud the indigenizing effects of the playwright’s spatio-temporal combinations. In the context of Burning Vision, one of the most spatially and temporally diverse of Clements’s works, Robin Whittaker has explored at some length the ways in which the play’s “chronotopic dramaturgy” reorients expectations of how time and space structure the theatre around a model informed by Indigenous epistemologies. While revelations of connectivity and windows opened onto alternate conceptions of spatio-temporality are significant results of the intercultural “timespace” moments (Whittaker 129) whereby Clements brings different times and places into conversation, I am interested here in returning to another, more immediate result of such dialogues: audience confusion, alienation, and disbelief.

2 Although as critics we may be reticent to admit that there is anything confusing about a work (fearful, perhaps, that we missed the point), confusion in the face of Burning Vision is common enough that it must be addressed. My own experience of lecturing on the play to a wall of blank stares and furrowed brows is echoed in director Annie Smith’s observation that her production of the work was met by “confusion from students and faculty who expected a linear story and resisted multi-layered, circular storytelling” (55). Such confusion points to a significant but as-yet unaddressed aspect of the Burning Vision: the way the play’s materiality works against its fiction, preventing audiences from fully entering or believing the story unfolded. This article draws out the implications of this conflict through a phenomenological approach that illuminates how the refusal of the work’s materials to disappear behind its fiction—to slip around what theatre phenomenologist Bert O. States calls the “backside” of the onstage illusion (371)—prompts a productive kind of disbelief, one that structurally underlines the work’s arguments about the fictitious or illusory nature of spatio-temporal boundaries and separations. To this end, the first part of this article provides a substantial sketch of the phenomenological approach to theatre. This framework is then applied to readings of the unbelievable bodies, objects, and spaces of Burning Vision and to a discussion of how the play’s material intrusions ultimately enrich its fictional message. In addition to nuancing existing readings of Burning Vision that view its alternative times and spaces through a postcolonial lens, this article’s emphasis on the productive aspects of audience disbelief in the material-fiction transubstantiations usually considered central to theatre points the way to a more broadly applicable “disbelieving” approach to theatre. This politically-oriented materialism goes beyond Brechtian alienation to more specifically interrogate the aesthetic importance of dramaturgical choices that seem to disrupt aesthetic experience.

3 Simon Shepherd’s brief preface to Palgrave Macmillan’s “Readings in Theatre Practice” series, which appears in every series text, provides a succinct introduction to the phenomenological play of the theatre. Shepherd describes the coexistence of raw materials and the illusions they construct as the “tense relationship” at the heart of stagecraft. “On the one hand,” he writes, “there is the basic raw material that is worked—the wood, the light, the paint, the musculature. These have their own given identity—their weight, mechanical logics, smell, particle formation, feel. [. . .] And on the other hand there is theatre, wanting its effects and illusions, its distortions and impossibilities” (x). The common solution to this tension is to allow the reality of the theatrical fiction to emerge through audience “suspension of disbelief”—“that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, that constitutes poetic faith,” as Coleridge formulated the concept in Biographia Literaria. Suspension of disbelief entails suspending or putting on hold one’s perception of the immediate material realities of the stage—of its wood, light, paint, musculature—in order to perceive the fictional world these materials evoke; in this way a kind of doubled perception occurs wherein the object is simultaneously seen as itself and as that which it represents. In phenomenological terms, an epoché is being exercised.

4 Epoché, a term borrowed from ancient Greek Skepticism, implies a cessation or restraint of all preconceptions about the external world. To exercise the epoché, Edmund Husserl explains, is to “[set] out of action,” “disconnect,” or “bracket” theses arising from the interpretive frameworks of “all sciences which relate to this natural world” as well as of one’s own previous experiences, allowing for a “‘pure’ consciousness” or “conscious experience” of events (108, 111-114). Like Coleridge, Husserl applies the epoché in order to manage belief and doubt. While suspension of disbelief is at times simplified (as in undergraduate drama courses) as a bracketing purely of the material “stuff” of theatre that allows the “magic” of its signification to take effect, and while avant-garde playwrights like Antonin Artaud have advocated bracketing to the other extreme of seeing objects in the theatre “not for what they represent but for what they really are” (160), a full phenomenological understanding of the theatre demands that the epoché be applied in both directions. As aesthetician Mikel Dufrenne puts it, one must be “a dupe neither of the real—e.g., the actors, the sets, the hall itself—nor even of the unreal—i.e., the represented object” (9). That is: concern over the realness of either the materials of theatre or of their significations must be partially set aside to allow the work to emerge. States describes this complement of the real and unreal as the “double aspect” or two faces of any object in the theatre. To “treat one of these aspects to the exclusion of the other—it doesn’t matter which,” States argues, is to disavow a truly phenomenological attitude toward what is set on the stage. “Phenomenology occurs” in the theatre, he concludes, “in the ‘seam’ between these two faces of the object” (375). For the phenomenologist, then, theatre requires less of the temporary disavowal of materiality often connoted by suspension of disbelief and more of a perceptual doublethink, an ability to hold one’s awareness of the material objects, bodies, and spaces presented in tandem with one’s awareness of what they represent within a fictional world.

5 While a phenomenological approach advocates that both faces of objects in the theatre be held in perceptual tandem, however, both Dufrenne and States make distinctions that privilege the significative over the material as the frontal or audience-facing side of the coin. The material stuff of the theatre is linked to the significative magic it conjures in States’s terms “backside” and “frontside,” terms derived from the phenomenological concept of “frontality.” Frontality describes the inescapably partial and subjective perspective with which we see the world: no object can ever be understood in its totality, since only one side of an object—its “front”—is presented at any given time. States offers the example of “a sphere revolving in space” to exemplify the frontality of the perceived world: “[the sphere] may reveal different sides or features as it turns,” he explains, “but it always remains the same sphere, it always continues around ‘the backside’” (373). He summarizes the theatrical application of this interplay between frontside and backside with the observation that:

In this conception, the performance presented to the audience is constructed, supported, or enabled by materials that are continually turned away from, though never wholly unknown to, the audience.

6 Elaborating a more comprehensive system, Dufrenne explains how performance experience is created using the terms “work of art” and “aesthetic object” to distinguish physical artistic creations from the aesthetic experiences they conjure. In Dufrenne’s equation, a convergence of various visual, linguistic, and auditory expressions combines with the audience’s focused reception thereof to equal the aesthetic object, “the work of art as grasped in aesthetic experience” (13, 3). The suggestion here that the work of art becomes an aesthetic object only through audience interaction and the viewing conditions Dufrenne mentions as necessary (but not sufficient) to aesthetic experience are helpful for understanding how the materials of the theatre must remain muted if their significative faces are to show. Dufrenne notes that elements “marginal” to or “in the background of” the performance, including onstage phenomena like actors’ bodies, set pieces, props, and lighting, and offstage phenomena like theatre ushers and other audience members, enable perception of the aesthetic object and themselves disappear—unless, that is, an “incident” such as an off-key note or forgotten line from a performer or a power failure in the theatre directs attention to them (7, 8). The material elements of theatre must be “neutraliz[ed]” in order for aesthetic meaning to take effect; they must be kept around the back of the performance front or “face” that is “turned toward” the audience (11-12, 13).2 To relate these explications of the fictional face of the theatre to the common understanding of willing suspension of disbelief, then: both States and Dufrenne mark a point after which materiality ceases to provide supporting backside for, and becomes instead a detractor from or interruption to, the aesthetic or fictional frontside presented to the audience. Both note the potential for audience suspension of disbelief in the material realities of theatre halls, stage settings, and performers to falter and fail, and for belief in what these elements represent to fail by consequence.

7 A phenomenological approach prompts a much richer understanding of how Burning Vision conveys its message than is offered by a focus on either just the stuff of the play or— as is the tack taken by criticism so far— just its magic. Theatre phenomenology can be used to interrogate the reasons for and the import of audience reactions of disbelief to Burning Vision, revealing how and why the play’s material is emphasized to the detriment of its frontside fiction. In the play, staging choices and intertextual incorporations make the suspension of disbelief necessary for aesthetic experience very difficult. The bodies, objects, and spaces of the play’s material background are not muted or marginalized in support of, but consistently interrupt, aesthetic experience; these backside materials demand to be recognized not only in tandem with, but in contradiction of, their frontside fictions. Throughout the play, fictional scenarios relating to time and space are repeatedly presented to and conventionally accepted by the audience only to be disrupted by contradictory and obvious material presences. In this way, Burning Vision not only draws attention to but catches its audience believing in the broader fictions or social constructs it critiques: specifically, the fiction that different times, spaces, nations, and human and nonhuman beings are bounded and separate from each other.

8 There is no discernible plot to Burning Vision, as events lack clear cause and effect. Rather, events from disparate times and places are placed alongside each other in a way that suggests connections between them: two prospectors discover uranium; a widow speaks to her dead husband though a fire; a miner and a radium watch-dial painter fall in love; a Dene medicine man speaks a prophecy; a Japanese fisherman dreams of his grandmother; a boat pilot and two stevedores navigate Northern waterways; a Métis woman makes bread; a Japanese radio siren insists she is American; a dummy waits to be destroyed by the testing of a nuclear bomb; a bomb explodes. These jumbled events depict untold aspects of the history of wartime uranium production in Canada through the eyes of individuals affected by it. More specifically, they explore the ethics involved in the Canadian government’s extraction of over 220 tons of uranium ore from the shores of Great Bear Lake, Northwest Territories, in support of the Manhattan Project.3 The play takes up issues of community raised by this history, critiquing the short-sightedness of the conceptions of spatial, temporal, racial, and species isolation that underwrite it.

9 The clash of Indigenous/non-Indigenous worldviews central to this history and foregrounded in Burning Vision has justifiably prompted critical interpretations of the play’s nonlinearity as an indigenizing gesture. According to Theresa May, the play’s repeated juxtaposition of disparate settings is a function of “the indigenous viewpoint from which the play is written,” a viewpoint that “allows for simultaneity of past, present, and future” and stresses the “radical, familial connectivity” among people and between people and the land (7). Whittaker similarly argues that the way “specifically delineated spaces are allowed to fluidly and dialogically converse” in Clements’s play “reclaims one indigenous temporal and spatial logic, that of Dene peoples, displaced by European linear timekeeping and mapping systems during acts of colonization” (131). The connectivity among people, place, times, and events that the play highlights does reflect a Sahtu Dene epistemology, and certainly recommends the play as an “eco-drama,” as May stresses—a stage play whose dramatic structures, characters, themes, scenography, and production requirements “fire our ecological imaginations” (5). While these readings make important points about the contrast between dominant Western concepts of time, space, and ecology and those presented in Burning Vision, however, they move too quickly past the confusion this contrast causes to suggest that it can be resolved if the play is understood as arising from and embodying Indigenous epistemologies. It is important to linger longer than this on the play’s confusing or unbelievable aspects, as they signal the difficulty of suspending disbelief in the unfamiliar world Burning Vision presents. Paratextual materials and staging choices throughout the play deliberately compound this difficulty, insisting on the material realities of performance in a way that impedes viewer immersion in the fiction they construct. A reading of the play’s staging, extrapolated from Clements’s text and illustrated with reference to three performances, demonstrates the ways in which the play’s materiality consistently forces itself upon the fiction to promote a produc\tive kind of disbelief that structurally underlines the work’s advocacy of difficult-to-perceive interconnectivities.

10 The first indications that the play will dismantle disparate conceptions of people, places, and times appear in its paratextual materials, which first construct and then debunk the fiction that the characters within the play exist in discrete times and spaces. A catalogue of character descriptions and a cast list corresponding to the play’s Rumble Productions premiere directed by Peter Hinton and performed at Vancouver’s Firehall Arts Centre in April 2002 is included in the print version of Burning Vision (published in 2003). The character descriptions given here clearly place characters within specific time periods and geographic areas. The Dene See-er, for example, is placed in the “Late 1880s,” Fat Man is described as “An American bomb test dummy manning his house in the late 1940s and 50s,” Koji is “A Japanese fisherman just before the blast of the atomic bomb,” and the Labine brothers are “prospectors that discove[r] uranium at the base of Great Bear Lake in the 1930s” (Clements 13-14). The spatial and temporal disparities of these character descriptions are reinforced by the inclusion of a timeline of events (16-17) spanning from the late 1880s “Forbidden Rock” prophecy to the 2002 premiere of Burning Vision and including such events as the LaBines’ discovery of pitchblende in 1930, the hiring of Dene men as ore carriers in 1932, the dropping of Fat Man and Little Boy on Japan in 1945, the testing of nuclear weapons in New Mexico from 1945 through the 1950s, and the death of the first Dene ore carrier in 1960. The timeline in the print version of the play was, according to its copyright page, “modified from one created by Rumble Productions for the original production of Burning Vision,” and was included in the performance-night program distributed to the audience (see Figure 1). The temporal and spatial coordinates provided in the character descriptions mentioned above allow the text reader or performance viewer to place characters along this timeline, visually concretizing their separation from one another: the Dene See-er, for instance, would be placed to the extreme left of the timeline, while Little Boy, who interacts with and eventually becomes the Dene See-er, is on the far right.

11 The temporal and spatial markers provided in the character descriptions and visualized in the timeline are intentionally duplicitous: they exploit assumptions about time and space commonly held in non-Indigenous North America to implicate audiences in the kind of narrow thinking that gives rise to ecological and racial violence within Burning Vision. These paratexts present official or accepted versions of history and model linear, boundaried timespace organizations in order to critique and complicate them; the audience accepts the information these materials provide only to be made aware, when the people, places, and times they define as discrete are brought together throughout the play, of the constructed and conventional nature of this information.

12 Even before action begins, other paratexts cause the audience to question and partially withdraw belief in the spatio-temporal world the timeline and character list together construct. The cast list included in the text, for example (which again refers to the premiere and was also included in the performance-night program), reveals that a number of the play’s actors are double- or triple-cast. Marcus Hondro and Kevin Loring are both triple-cast: Hondro plays Brother Labine 2 as well as The Miner and one of the two Stevedores; and Loring plays Brother Labine 1, the Dene Ore Carrier, and the other Stevedore. Margo Kane is double-cast as both the Japanese Grandmother and the Widow, while Allan Morgan is double-cast as Captain Mike and Fat Man; Julia Tamako Manning plays both Tokyo Rose and the older version of Tokyo Rose, Round Rose (Clements 10). While casting actors in multiple roles is an economically determined reality across Canadian professional theatre productions, in this case an important structural reinforcement of the play’s cautions about isolationism is provided when the cast list reveals, in direct contradiction to the scenarios of separateness introduced by other paratexts, that multiple characters cohabit in a single actor’s body. People are not separate from one another, the cast list suggests, but are quite literally made of the same flesh. The cross-racializations involved in these multiple castings, which would be apparent from the actor profiles usually included in the program and certainly visible onstage, deepen the play’s critique of believing that people are separated by racial lines. In all cases but Manning’s, at least one of the racial identities played by the actor departs from that of his or her other role(s) and from that of the actor him or herself. Hondro, a Euro-Canadian actor, plays a white Canadian in his roles as Brother Labine 2 and The Miner but plays a Native in his role as the Stevedore; Loring, a member of the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) First Nation, plays Native characters as the Dene Ore Carrier and as the Stevedore but a white man as Brother Labine 1. Kane, a Cree-Saulteaux performing artist, plays a Dene character in her role as the Widow and a Japanese character as the Grandmother; and Morgan, a white Euro-Canadian, plays a racially nondescript American as Fat Man but a racialized Icelandic immigrant as Captain Mike. The various racial identities represented by a single actor make material realities of bodily sameness difficult to deny in favour of a fiction of difference.

13 Program text does not help to build the fictional world onstage in the same direct way as do the physical materials of actors’ bodies and stage spaces, but paratextual materials do serve, as Dufrenne points out, as preparation for and guide to the fiction created: these and any other pre-performance information made available to the audience “clear the way for [one’s] perception of the aesthetic object” (12n5). In Burning Vision, however, paratexts act not as preparation for but as impediments to perception of the aesthetic object: the viewer is given a significant moment of pause in which his or her belief in the spatio-temporal information provided in the timeline and character descriptions must be qualified and revised in light of the racial, spatial, and temporal collocations indicated by the cast list—and, subsequently, presented onstage. This paratextual solicitation and rejection of belief sets in motion the pattern of belief disruption that shapes the play’s staging.

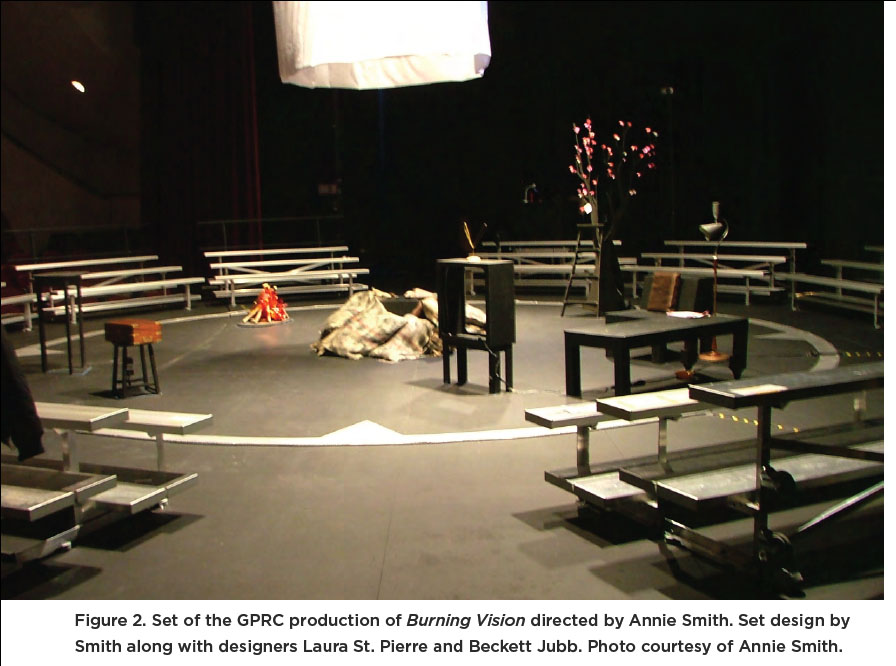

14 Staging choices construct a fiction of separation that is contradicted and, eventually, totally undermined by the intrusion of material realities into fictional stage spaces. Throughout Movement One, the characters—who, as we may or may not believe from the paratexts, are separated by space and time—are all onstage at the same time. Their interconnectivity is obliquely suggested by their spatial proximity to one another, but they cannot see each other. In the Grande Prairie Regional College (GPRC) production of the play directed by Smith in 2009, the design of the Douglas Cardinal Theatre set included divisions into separate playing spaces for characters from different time-spaces. The circular stage space of this performance, meant to represent a medicine wheel as well as a compass, was made of quarter-inch Masonite painted silver and screwed into the floor; small arrows pointed inwards at each of the four cardinal compass points (see Figure 2). “The lines of the compass were not physically drawn,” explains Smith, “but were denoted by four light beams that intersected on stage like target cross-hairs” (56). Four playing spaces were created by these intersections, and a fifth was placed in the centre of the circle. Characters separated in space and time occupied different segments of the circle (or medicine wheel):

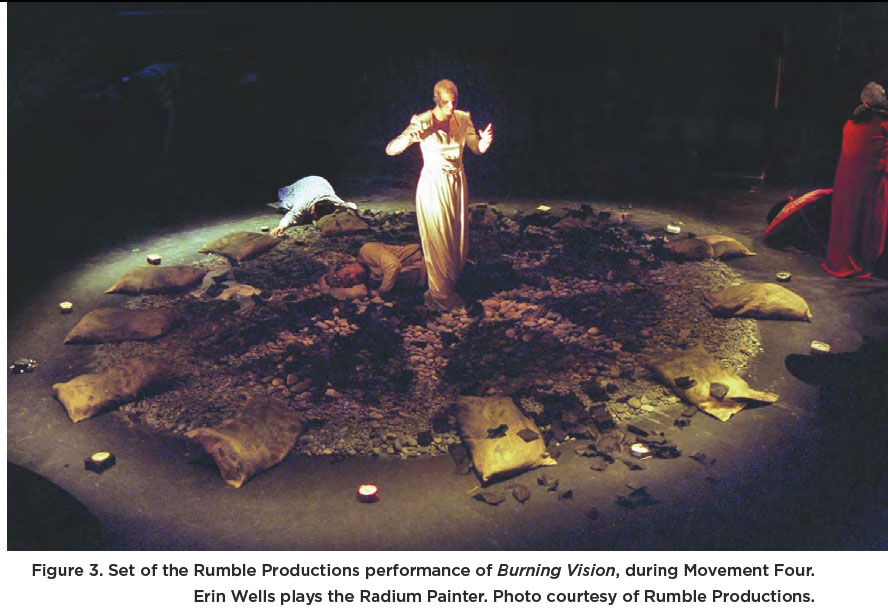

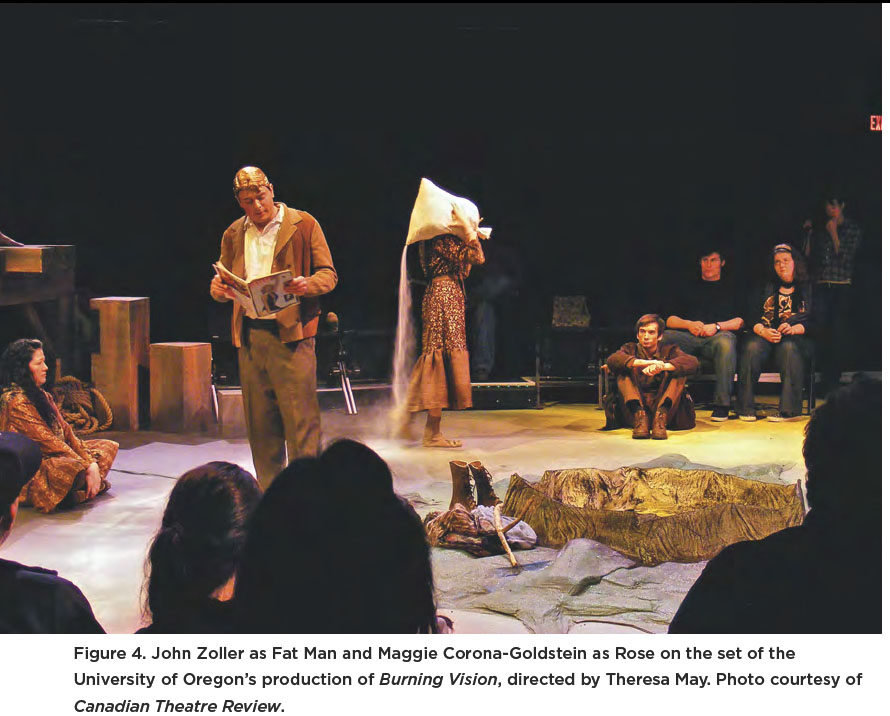

The Rumble Productions stage used a similar compass shape, created in this case by the placement of light and dark gravel (see Figure 3); this set, however, was not divided as cleanly as Smith’s stage into the four-directional compass or medicine wheel, and its players were not totally confined to specific spaces. The University of Oregon’s production of the play, directed by Theresa May, did not use any lines—drawn or lit—to separate its stage into different playing spaces (see Figure 4). Though the fiction of separate times and spaces was supported to varying degrees by the stage divisions made in each performance, the small size of each stage dictated that, in all three performances, the bodies of the various actors would be in very close proximity to one another. And, in each production, the fiction that characters occupy separate times and spaces depended on audience suspension of disbelief in this obvious material proximity.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 115 While the compass arrows in the GPRC production and the gravel markings of the Rumble Productions set facilitated audience recognition of spatio-temporal separations, lighting was the primary element in the creation of this fiction across all three productions. As the text of the play indicates, lights are up on only one spatio-temporal location and its characters at any given time. Light is produced locally and can be understood as part of the fictional world rather than an extra-diegetic effect: the Labines’ space is lit by the flashlights they carry, Fat Man turns his side-table lamp on and off to light his space, and the “tunnel light” of Koji’s dream illuminates Koji and his grandmother. Stage directions call for lights to go down on one character when he or she is no longer part of the fiction to indicate that his or her scene has ended and another one, removed in time and space, is beginning. For example, in a transition between Koji’s dream of his grandmother and Fat Man’s meditation on being “part of the cultural revolution,” the stage directions read: “The tunnel light disappears. FAT MAN turns his side table lamp on” (Clements 33). The way material realities intrude upon fictional ones is obvious here. Given the closeness of the actors to one another and of the audience to the actors (especially in the GPRC production, which is staged in the round [see Figure 2]), the audience is aware that characters who are unlit are still onstage: the actors’ bodies and the objects that populate their playing spaces are visible in the light cast by the other characters’ spaces. This obvious material reality is difficult to hold in tandem with the fiction that lights down on a character excises them momentarily from the action. The choice to stage the separate times and spaces of the characters through lighting foregrounds the conflict between the play’s material reality and its fiction: actors who represent various characters are materially present all along, while their fictional characters are by turns invited into and dismissed from the action through lighting. This staging decision makes the fiction of separate times and spaces much more difficult to believe than would, for example, alternating exits and entrances of characters, where the staged distance between one actor’s action and another’s would support the fiction of their characters’ separation in time and space.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 216 The audience’s attempted bracketing of the material presence of actors not currently involved in the fiction is echoed by the actors’ own bracketing of the spaces and bodies outside their respective fictional worlds. Throughout Movement One characters are unaware of one another, even when stage directions indicate that one character’s playingspace light falls on another—for instance, although Brother Labine 2’s flashlight “momentarily lights ROSE’s face” (Clements 21), he cannot see her. As the spaces of the different characters begin to collide in subsequent movements, however, they begin to hear, see, and interact with one another in a way that redefines the spatio-temporal separations previously established as illusory. At first, only the sounds of other characters are heard from other spaces, with no understanding of the source; for example, Brother Labine 2 perceives a “sheeek sound” when the Widow strikes a match (22). Such aural connections occur with increasing frequency throughout the first two movements and begin to involve multiple characters. By Movement Two, stage directions indicate that Rose’s sack “falling to the ground with a thud” can be heard “in FAT MAN’s space,” upon which the Miner, who has also apparently heard the sound, calls out from his playing space “Hello? Is anyone there?” and from his space Fat Man responds “Who’s there?” (45). Soon, objects begin to fall from space to space: Rose discovers the note left on the ground for Koji by his grandmother and Koji catches a loaf of bread Rose throws into the air (59). In Movement Three, characters begin to interact with one another more fully. Fat Man “looks directly at [Round Rose] for the first time” (86), seeing her character in the actor’s body rather than merely imagining her as Tokyo Rose. With confusion, the Stevedores “catch” the Japanese Koji and haul his body into their boat like a trout (88). The way the boundaries between characters collapse over the course of the play directs critical attention to the conventional, fictional, or frontside nature of the boundaries established onstage in the first place. The audience can see all along that each actor hears and sees everything the other actors are saying and doing—that something dropped on stage or thrown in the air by one actor, for example, is easily visible to and within reach of another. When the characters break through the fictional separations of the stage and acknowledge this proximity, the audience’s own denial, bracketing, or suspension of disbelief regarding their closeness is critiqued. As with audience acceptance of the separations defined by the timeline and character descriptions, the audience is here made complicit in the construction of conventional boundaries that enable the kind of ignorance expressed in Brother Labine 1’s insistence, upon the detonation of the nuclear bomb, that he “didn’t know” (118).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 317 The inclusion of contradictory spatio-temporal information in the play’s paratexts and its overturning of established stage conventions draw attention to performance backsides—actors’ bodies, stage space, and onstage objects—that are physically apparent but could be bracketed or suspended from recognition by the viewer. The material backside does not easily disappear here in favour of the fictional frontside. Rather, the unyielding material reality of the backside formally undergirds the message of the frontside fiction that connections exist among people, places, extraction, production, and consumption even where they are hard to perceive across racial lines and through large expanses of time and space. Whittaker’s view of Burning Vision as offering a “scripted magic [. . .] with which audiences and readers are encouraged to allow the normally divisive elements of time and space to fade behind an interest in fictional combinations of performance time and performance space” (137-8) now appears insufficient. The play’s amalgamation of diverse times and spaces into a shared playing space does recall a Dene worldview in which past, present, and future, multiple places and spaces, and human and nonhuman life forms are connected, but it also does much more than simply present this alternate configuration.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 418 The audience’s inability to allow expectations about the “divisive” nature of time and space to completely fade, as Whittaker and May suggest they might, is in fact central to the play’s message. This difficulty is cleverly exploited through staging, casting, and paratexts that set visible spatio-temporal connections against the fiction of their division. The play’s positioning of its audience in the difficult situation of disavowing obvious spatio-temporal coincidences of bodies and objects onstage in order to believe in their fictional separation underwrites the play’s message that separateness is itself constructed, fictitious, or illusory—that multiple, often unapparent connections exist among times and spaces that appear physically and temporally disconnected.

19 This directing of audience attention to the backside of performance is reminiscent of the self-reflexive constructedness of the alienating theatre for which Bertolt Brecht is most well-known. As TRIC readers will be aware, Brecht advocates the creation of an alienation effect (verfremdungseffekt or V-effekt4 ) through “playing in such a way that the audience [i]s hindered from simply identifying itself with the characters in the play” (Brecht 91); this is achieved through such convention-disrupting “effort[s] to make the incidents represented appear strange to the public” as extreme stylization of gesture and breaking the fourth wall (92-3, 91). Alienation of an audience from the story presented was seen by Brecht as providing escape from theatrical naturalizations of historically contingent ideological and institutional constructions (98); foregrounding the constructedness of the theatre and exposing its conventions was thought to denormalize not only theatre but the social conventions it mirrored. I have delayed introducing Brecht in favour of interpreting Burning Vision through a phenomenological lens because I see the disbelief manufactured in this play as different, deeper, and more directly related to the diegesis, than Brecht’s theatre of alienation. The staging effects in Burning Vision do evince a common trait of Brecht’s V-effekt: a spatial flexibility in which the audience is asked to participate in the fiction that wide expanses of time and space exist between simultaneously-present playing spaces separated by mere feet and inches of stage.5 In Burning Vision, however, the audience is not merely alienated from the fiction presented by the play’s foregrounding of its material staging. In a way that echoes but exceeds Brecht’s conception of self-reflexive theatre, the materials of Burning Vision disrupt belief in its fiction in order to reinforce its message about the dangers of conventional beliefs about separateness—beliefs, for example, in the separation of past, present, and future, of national boundaries, and of humans from each other and the nonhuman world. Separateness is presented in the timeline, the character list, and stage spaces as a fiction that the audience is asked to accept, to which end the material realities of proximate actors’ bodies onstage and the cohabitation of various characters within a single actor’s body must be bracketed out. The audience’s belief in the separation of the times, spaces, and people represented is then hindered by paratexts and staging choices that insist on the material realities of closeness in order to expose separateness as a fiction. In this way, performances of Burning Vision exemplify what States refers to as the phenomenological “backside become frontside” (372): the performance’s backside materials are illuminated in order to strengthen the frontside fiction, in such a way that the backside itself becomes part of the frontside—its “absence become[s] presence” (372).

20 The message of Burning Vision appears more powerfully when we address—rather than sweep aside or corral into coherence—the moments of confusion, disbelief, and disorientation it engenders. A phenomenological approach that interrogates the interplay of the play’s backside materiality with its frontside fiction illuminates how the material intrusions that make the fiction difficult to believe are in fact part and parcel of its message. The play must be looked at in its doubleness to recognize its full effects, and to realize the care with which even its non-fictional stuff has been made magic. While Burning Vision provides an apt example of the way a backside can invade a frontside in order to reinforce its message, this reading models a disbelieving approach that could be equally applied to much contemporary theatre not easily interpretable through conventional parameters. Such an approach wields phenomenology to discover how and why audiences are made to resist immersion in the fiction presented. This approach is akin to but more powerful than Brecht’s more general aims for alienation in that it asks the critic to identify the import of disbelief in specific relation to a performance’s message. Just as an unexpected metaphor presents an apparent mismatch of tenor and vehicle that impedes belief in the depiction, prompting questions about how, exactly, the thing described is like that to which it is compared, explicit mismatches between material and fiction in the theatre prompt disbelief that leads to inquiry. When disbelieving, audiences ask what the relationship between an object and what it represents might be, why the fact that they are not one and the same is being made obvious, and what purpose this forfeit of belief might serve for the work’s main message. In Burning Vision, the answers to these disbelieving questions speak to the dangers of uncritically accepting fictions of time as discontinuous, space as discrete and divided by national borders, and people as bounded by bodies and racial identities. More broadly, answers to questions asked in disbelief might concern the inadequacy of the theatre to represent certain types of events as well as the asymptotal nature of representation itself, in which the line of the word, image, or object approaches but never becomes one with the idea, person, or event it represents.