Forum

The Tongue Play:

An Auto-Ethnography

When I made the decision to marry a Canadian and move to Toronto, the thought that I would be working with an accent did cross my mind. “It is a bilingual country and also a country of immigrants. Surely they are used to it,” was my reasoning. My future husband, a veteran of the TV industry, assured me that it would “be fine.” This was wishful thinking on both of our parts. I didn’t realize how naïve I was to think that my career depended only on Canadians being used to immigrants. I didn’t factor in that I was not used to being one!

The sudden change that occurred after that first transatlantic flight was not “fine.” On the negative side it resulted in a deep and lasting identity crisis, many bouts of depression, long periods of unemployment, and stress. It also resulted in a Ph.D., a successful teaching career, a directing career, and even a resurrection of my acting career, and becoming a published author. In this article, therefore, I want to share the implications of a transatlantic flight from the former Yugoslavia to Canada in the distant 1986, which instantly made me into an audible minority, a marginalized actor from a recognized and respected mainstream actor.

A great deal has happened in three decades, from my first meetings with casting agents and hearing but not understanding the phrase “an accent is a hard sell” in 1986, to acting the roles of immigrants, foreigners, and servants upon the stage, to acquiring the accented actor’s “Stockholm syndrome,” to teaching acting at Ryerson Theatre School for almost two decades and running the Acting Program for the last decade, to writing a play under the nom de plume of Lola Xenos in 2012, and being nominated for a Dora Award for outstanding performance in 2013. Every effort I made had a common denominator: a search for belonging inextricably linked to the way I speak.

I can compare this experience to the act of translation. If I was an “original” when I boarded the flight, when I landed I was a “translation.” My thoughts were formed in another language and then translated into an immigrant language and an immigrant identity. I was designated to be an “other” due to my accented speech, my origin, and my upbringing. The past twenty-five years of translation have been twenty-five years of meaning making.

My trouble with speech took me on a journey that began as a search to learn how to speak like “everyone else,” meaning Canadian. This impossible task led me to study many techniques until I finally found Michael Chekhov’s acting technique. The particular aspect of the technique, which has to do with the inner working of sound, led me to a new understanding of the relationship between speech, pronunciation, and identity. I am hoping that my account of the intensity of this theatrical exploration and experience may illuminate universal audible minority immigrant experiences. I take the liberty of using my acting experiences and my own personal experiences as an immigrant artist as a central point of reference.

≈

Recent studies by Boaz Keysar and Syuri Hayakawa have shown that a foreign accent makes one sound less believable. Prejudice is one of the reasons for this but, as Keysar and Hayakawa found out through their experiments and research, often:

When this effect of the “wet morning newspaper” is applied to the specific challenges of an actor immigrant, the impact of “sounding less true” is devastating. After all it is truthfulness and believability that we actors trade in.

Many subsequent shifts in how I sound, which occurred as my spoken language abilities evolved, have changed my identity over and over again. As a young actor I tried to imitate the standard Canadian sound and hoped that with time I would succeed. Later I learned that our tongue muscles are fully formed by the age of twelve, so to sound “Canadian” was not a possibility for me. I went from being ashamed of my sound to being proud of it: the wet newspaper slowly drying over the years.

Yet it was one moment—“but a lesbian with an accent”— that was decisive. I “nailed” my audition for a lesbian role in a Toronto production, but did not get the part. Weeks later I ran into the director and asked for feedback. She answered: “You did a wonderful job but we simply couldn’t cast you. Lesbian with an accent is just more than this play could take.” She also suggested I “get rid” of my accent.

This episode made me realize that for almost a decade it wasn’t my level of truthfulness or quality of acting that had anything to do with me not being cast. My “tongue” stood in my way. To belong was to sound “Canadian” and although I held a Canadian passport, nothing I could do would ever change this. My tongue muscles were fully formed and I could not sound native. When it came to acting opportunities I was reminded of an expression we used under the Soviet rule: “Everyone is equal. It is just that some are more equal than others.” I felt that my ten-year battle to act the parts other than the immigrant-exotic-foreign-servants was lost, and so I decided to put all my effort and energy into teaching acting.

Twenty-five years later I am often told: “really you have such a mild accent it is not worth mentioning.” But of course that sentence is contradictory in that it mentions my accent. I am perceived as a foreigner, even after twenty-five years of my daily struggle to find the ways to contribute to the Canadian cultural milieu outside of my immigrant identity, something vital to an actor’s career. The following quotation from Hayakawa and Keysar’s study resonated with me by offering one explanation for why true integration has been so difficult:

While parts of the above statement might have been true for my acting career, it is not true of my teaching, which has been primarily steady, easy, and successful. I wonder if the secret is that for an acting teacher an accent and life in translation provides a kind of ability to perceive subtleties and differences that go beyond language. Consequently, these teachers (including Richard Boleslavsky, Maria Ouspenskaya, and Michael Chekhov) seem better suited to draw out their students’ “authentic” expression and congruence. Authentic in this context means the opposite of stereotypical and an original rather than an imitation (or a translation?). An authentic performance is true to its own personality, spirit, and character and relates to a sense of truth that is felt and experienced sincerely and honestly within a given context. And while casting often has to do with the type, an authentic performance finds originality within the parameters of the type. I followed in their footsteps and became an expert in Michael Chekhov’s acting technique, which among other things teaches students to become aware that sounds deeply affect their bodies. In my classes, students spend time developing the ease of speaking, the flow of breath, and an understanding of the sound as movement and as gesture. They learn how to put into practice “the idea that words travel on the breath” to the other person.

But language also forms identities through names: one of the common complaints immigrants make is how often their names get mispronounced. My name is pronounced differently in Croatian and English: Cintija Ašperger is pronounced Tzeent-ee-yah and Ashperger, with rolled r’s and voiced e’s sounding like “eh” Ahsh-pehrr-gerr, whereas in English Cynthia is pronounced Seen-thee-ah and Ashperger is spoken without rolled r’s and the e’s are silent: Ash-phr-ghr. These two names have independent lives within me through the sensations they produce. I experience the sensations of Cintija as quick and fiery; it rings in a major key. When the name is pronounced in English, a collection of sounds offer sensations that are softer, and the sound, as I hear it, is in a minor key. I experience my name as introspective and mellow. Hence, I became aware of the inner sensations produced by my name, and how they can instantly change my relationship to the outside world. Simply by hearing my name in Croatian or English, I can experience my memory, history, culture, intentions, and relationships as sensations. I can then connect these to the sounds of the two languages I speak. Both names cause a different interiority, and as a result, I express myself differently. This is the inner perspective.

Now let’s look at an outer perspective. Who hired me in my first three years of living in Canada? First, it was Banuta Rubess, a daughter of Latvian immigrants who later moved to Latvia for almost two decades. Then it was Damir Andrei, a son of Croatian immigrants; Sigrid Herzog who spoke English with a thick German accent; Tibor Feheregehazy, the 1956 Hungarian refugee, who also spoke English with the thick Hungarian accent; and finally Claude Guilmaine, a French Canadian. They seemed to have no issue with the way I sounded. Yet I decided to leave Canada for the very reason of my accent. I packed up my three-year old daughter and moved back to Croatia where I continued within the mainstream acting profession as if I had never left. Between 1989 and 1991, I had a large recurring role on a TV series, a lead in a TV movie, and was a member of an ensemble of an established theatre, playing in five productions in rep—all in the space of two years.

But then 1991 came and the civil war started; now I had no choice but to return to Canada. Upon my return, Damir Andrei and I produced a one-woman show about the priva- tions of Sarajevo titled Out of Spite: Tales of Survival from Sarajevo. While this story needed to be told and we spent 1992-1994 developing it, in retrospect I realize that this was the pivotal moment when I started looking for roles defined by my ethnicity and language. I thought that this was my only chance to work professionally in Canada. Today I refer to it as the actor’s “Stockholm syndrome.” Instead of saying “I am an actor capable of telling ANY STORY,” I started to typecast myself: a soul-destroying practice.

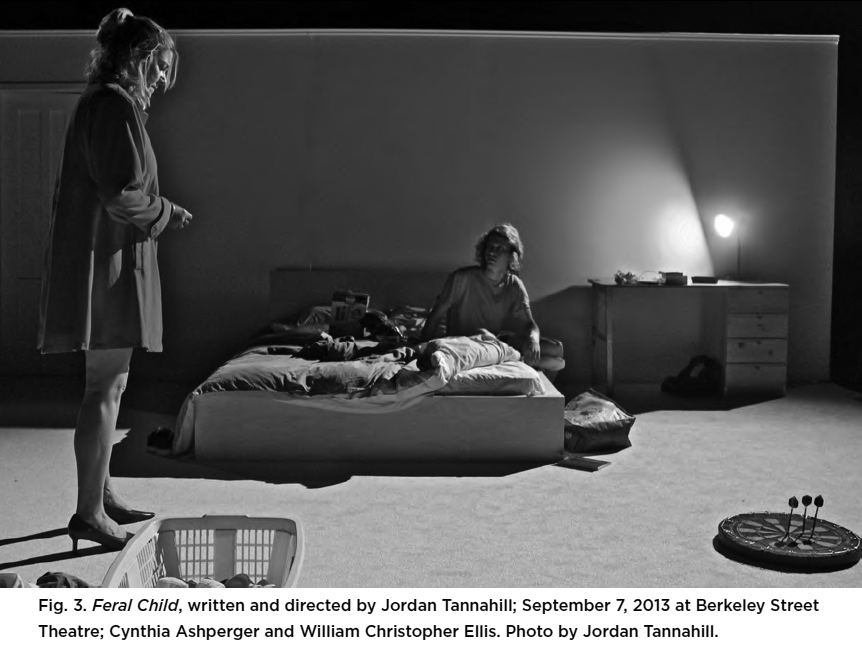

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Twenty-three years after the start of the civil war in former Yugoslavia, I was nominated for a Dora Award for my performance of a Bosnian war refugee in Feral Child by Jordan Tannahill, produced by Suburban Beast. Though marked by its “otherness,” the part I played in this two-hander was a three-dimensional one, and the relationship with the other character was complex and multi-leveled. Right before playing this role, I had played a German businesswoman in The Berlin Blues by Drew Hayden Taylor and a Bosnian Clytemnestra in Elektra in Bosnia by Judith Thompson. This production was a part of the Women and War Project that was conceived and directed by Ryerson’s Peggy Shannon and performed in Greece in 2012. In the same project I played Agamemnon in Ajax in Afghanistan, Timberlake Wertenbaker’s adaptation of Euripides’s Ajax.

Ramona in Who Killed Snow White, also by Judith Thompson, followed. In fact, Thompson changed Ramona’s history to fit my accent upon my request: my audible minority status had taught me to insist on having my presence upon the stage explained through my otherness, my foreign accent syndrome. Naturally Thompson used this change to strengthen the conflict between Ramona and her mother Babe. However, when I cast myself in A Summer’s Day by Jon Fosse, a production I directed and produced in 2009, I cast myself in a part and a play with a theme that had nothing to do with immigration. I played the roles of Woman and Old Woman who was masked. I managed to overcome the Stockholm syndrome by positioning the overall concept towards stylization through the use of masks when depicting the present time and realism for the scenes from the past. The production was successful and the otherness of my sound didn’t come up at all.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2There is a positive aspect of speaking in a second language: it facilitates “psychological distance,” which helps immigrants to make decisions more rationally. As Hayakava and Keysar write, “foreign words do not feel the same as words in your native language because they do not carry the same emotional weight [. . .] You speak the language more slowly and understand it more deliberately [. . .] It could distance you from your impulses and intuitions.” I experience this distance when writing in English. English gives me a freedom that I do not have when writing in Croatian. When I started to write my musical comedy The Tongue Play, I couldn’t write it under my name and so my nom de plume “Lola Xenos,” named after Ivo Lola Ribar, an antifascist fighter, appeared. This name stands apart from all of the women “Cynthia Ashperger” represents and so can be objective and free.

Lola Xenos, who is “me,” tells a story of Kathy Woodrough from Peterborough, who suffers from a foreign accent syndrome, a rare medical condition in which patients—survivors of strokes, comas, or head traumas—develop what sounds like a foreign accent. Her trusted guide and sidekick is a Bosnian-Canadian-hospital janitor/actor Visnja, both of whom are “me” as well. While Visnja’s sub-plot of an actor trying to work in Canada is most accurate in terms of actual events in my acting career and actor identity, which centres around the codes of art, skill, and language, Kathy’s story is most accurate in terms of my identity outside the profession, which centres around codes of gender, class, sexuality, relationships, and citizenship. In the following excerpt Kathy is trying to get to terms with the fact that she indeed is sentenced to sound like an immigrant for the rest of her life and Visnja describes to her what it is like to be different:

VisnjaYou know it means Sour Cherry in my language.

KathyThat’s unfortunate Veeshnja.

VisnjaVell it’s not unfortunate in my language. Vhat about callink your kid Apple? That would sound so stupid in my language. Yabuka. Everyone vould laugh at you. Just goes to show you...I talked to this Polish girl once. She said her boyfriend proposed and she asked herself if she should merry him in English and the answer vas yes. Then she asked herself in Polish and the answer vas NO.

KathyDid she marry him?

VisnjaShe still stallink. (Silence.)

VisnjaI vas auditioning for something. I don’t know what it vas but I do know that I practiced my diphtongues for a week. D. O. N. apostrophe T is not pronounced “dohn’t” it is pronounced “doun’t”. There is an O and a U in that letter O. That is a dipthongue in case you didn’t know. And I really wanted to master the soft Ts. They have almost a “ch” feel. “Try” almost sounds like “chry”. I finished audition and knew my “chrying” was irrelevant. Then I walked into first clothing store I saw. “Excuse me, I would like to chry this skirt in size medium please?” That’s all I said. The cute salesman answered with a Spanish accent shanking his head: Why are you trying so hard to sound English honey?” Chrue story.

Kathy Kathy (cries) Dr. Brook told me to go to an ESL class.

VisnjaDon’t cry. It’s not so bad. Like in restaurant when I ordered wheel I got a laugh.

KathyWheel? I don’t get it...

VisnjaInstead of veal. (Kathy cries even more.)

VisnjaAnd one time I said: “I’m not very hungry I’d just like some sneaks”...instead of snacks... Dat night after dat audition I was baby-sitting my most beautiful baby. My sweet, little, blond neighbour Ana. She caught me crying. “Why are you crying?” I said it vas because I have an eksent so nobody will play with me. “Oh Visnja, don’t cry”, she said “I will play with you. It’s not like you are an alien!”

Kathy(cries) That’s so nice!

VisnjaDon’t cry! I will play with you. Tell you vat. Come to my ESL with me. We love our teacher. She’s great!

KathyYou gotta be kidding.

VisnjaI’m serious. Look Kedi, already everyone is asking you were you from. Dis means you can never be Canadian anymore. But you can be a New Canadian. It’s not so bad. Here is my number. Call me. We go together.

Lola writes in a “borrowed tongue,” trying to “challenge cultural imperialism and the dominance of the standard English through the use of various local ‘englishes’” (Karpinski 2). Lola’s voice is present in the nine songs that are used as distancing effect throughout the play. Lola aims to enter into a dialogue with the dominant ideology and so she aims to “dismantle the master’s house” (2), when she also wants to teach and amuse. She delights in presenting the ways we think of each other in stereotypes and sends her protagonist to the Accent Reduction Class, which in itself is a forum for this multitude of “englishes” with Bosnian, Brazilian, Korean, Vietnamese, Russian, Saudi Arabian, and Filipino touch. Lola notices the difference in reception of transcribed accents by the immigrant and English native-speaking Canadian readers. The immigrant reader laughs at the crude transcripts, while the sensitive Canadian reader is uncomfortable and feels that the transcription might be inappropriate. In this act of stereotyping the standard Canadian play reader Lola pairs down the transcription and supplants it with a note to the reader: “I will not transcribe all of the mispronunciation for the ease of reading. But will include enough to give the reader a taste.” As Karpinski explains, on the one hand, by transcribing “englishes” she is performing an act of neocolonialism, she gives voice to the “other” (1-3). On the other hand, she is subversively working to speed up the collapse of the hierarchy of “first” and “second” languages and “mainstream” and “immigrant” cultures.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3At the same time, Lola’s Canada is a utopian setting. An egalitarian and fair society is how Canadian society often portrays and perceives itself despite the many forms of marginalization and discrimination that are woven into its fabric. The “fish out of water” situation is set against this romanticized landscape to paint a composite picture of urban Canadian society. “Real” Canadians and “new” Canadians learn from one another and in the happiest of happy endings tolerance prevails. Lola thinks of it as Trading Places or the Prince and the Pauper with a linguistic twist. She wants The Tongue Play to educate, enlighten, and entertain those in the mainstream, so they can imagine their experience speaking in a “borrowed tongue.” Lola wishes for the concepts of “mother tongue” and “borrowed tongue” to become unimportant, and she wants the play to be produced. Cynthia Ashperger wants this play to be produced too and writes a grant proposal.

In 1995 I became politically active by supporting the non-traditional casting cause initiated by actor Brenda Kamino, who wanted to help actors—visible minorities—on the Toronto’s scene. I raised my voice for the audible minority. Canadian Actors’ Equity Association published two of my letters in the Equity Quarterly Journal. One was a plea to allow the actors speaking with an accent to play other than stereotypical immigrant roles. The other was my reaction to Kate Taylor’s review of the Chalmers-nominated play Not Spain, in which I appeared in the role of a Montreal journalist. Taylor criticized the director’s decision to cast me as a Montreal journalist as unrealistic; while she had no issue with a South American actor playing a Bosnian part in this two hander: “Ashperger, who successfully played a Sarajevo survivor in the recent one-woman show Out of Spite, speaks English with a slight Eastern European accent. In most roles it wouldn’t matter, but here it contradicts the script by hinting she knows more of the world than Montreal” (2). Just imagine a reviewer criticizing a visible minority actor being cast as a journalist from Montreal yet approving of an actor from India being cast as (let’s say) a Korean. S/he would likely be rebuked for racism. Meanwhile when the same fate befell me, an audible minority actor, there was only silence and indifference. I wondered what was the reason to this? Walter Borden, a well-known Afro-Canadian actor from Halifax, offered this theory: “Child,” he said, “we black actors carry the fight of our parents and our children will carry our fight, but your child doesn’t have the same issues. Child you are alone.” It sounded plausible and depressing. Alone I tried to confront this absurd double standard in which a visible minority person was visible while an audible minority actor was not heard (pun intended). It dawned on me that the colonialism of the past has now increasingly been replaced by the colonialism of the present in the form of English-language colonialism.

Since the 1990s the plight of visible minority actors and colour-blind casting in Canada has been made public and resonated with many theatre producers. However, the audible minority cause has not had the same fate. I felt privileged to be a part of Volcano Theatre’s 2006 production of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler in an adaptation by Judith Thompson with two prominent Black actors, Yanna Macintosh and Nigel Shawn Williams, playing Hedda and Judge Brack. Subsequently there are many other examples of non-traditional casting of visible minority actors. Yet we have not seen the same kind of positive change when it comes to the audible minority; accented immigrant actors are still for the most part relegated to the immigrant parts and immigrant themes representing their ethnicity and geographic experiences of exile.

I loved playing Berthe, the servant girl, in the aforementioned Hedda Gabler. The part came to me after a few years of my absence from the stage. Accomplished theatre director Ross Manson dusted me off and put on stage, ironically, in the role that “worked” with my accent. At the end, Berthe was the quintessential European cleaning lady. Yet, these type of servant roles are the roles that contemporary visible minority actors avoid. The opportunity was artistically important, the experience was invigorating; I continued to work with Volcano as a teacher at Volcano’s Intensive for years to come, and getting to know Judith Thompson was a beautiful gift, but what this casting choice really meant for the actor as audible minority case? It was a generous and thoughtful step of inclusion and yet of “othering” as well.

As I’m finishing this little auto-ethnography, I am filled with a mixture of sadness, pride, and nostalgia. I am once again nostalgic for the good, old days of belonging in Croatia (former Yugoslavia), nostalgia I thought I had left behind a long time ago. I am also remembering with sadness those first days of being an immigrant, which were a mixture of hope, resolve, fear, and confusion. I am also proud of my accomplishments, which allowed me to beat the impossible odds and raise twenty generations of actors at the Ryerson Theatre School and develop a theatre career in Toronto. I remind myself that this kind of experience would have been impossible had I stayed in Croatia. But as much as I’ve accepted the reality of being an eternal foreigner I am resentful and I am also regretful about my life as an accented actor in Canada. I wish I had spent less time assimilating and more time communicating, telling stories other than immigrant-themed ones. I wish that I didn’t have to negotiate my identity through so many complex and multiple dis/identifications. I wish I didn’t have the Stockholm syndrome, I wish I were fully accepted as a Canadian not Croatian-Canadian actor, and I wish that there was a much stronger attitude of embracing translation, accents, and multi-culturalism in the theatre of my country of Canada.

The audible minority in Canada is 6.6 million strong and growing. The time has come for the Canadian theatrical scene to see the truth of this statistic. One-third of Torontonians and one-fifth of Canadians speak a language other than English or French at home! Many accented actors with rich acting backgrounds live in Canada. While accented people play all sorts of roles in our daily lives, these actors do not experience the same fate upon the stage. The time has come to examine the colonial mentality in theatrical casting, criticism, and reception in regards to it. Canadian theatre owes this to one-fifth of Canada’s people!