Forum

Impact of the Immigrant Experience on My Theatre Career

1 When I arrived in Canada in 1976 as a Chilean immigrant, I wasn’t sure whether to continue my theatre career or leave it and try to get another job. I met actors from other countries who said: “We had to abandon that dream.” That scared me. And I did have to adapt the way I worked in theatre to the new reality. In my country of birth, I was a classically-trained actress, my teaching and directing were secondary activities. Here, to be able to continue to work in theatre, I had to take on all the responsibilities of running a company: administration, outreach, playwriting, directing, even training my future performers! This is how I founded PUENTE Theatre in 1988, in Victoria, B.C.

2 There were few immigrant actors in Canada at that time, and that concerned me. If immigrant stories were staged, somebody else acted in them: a Canadian-born actor, who seldom had any connection with the immigrant’s reality. My theatre was shaped by my interest in achieving authenticity on stage and also by a wish for equality and solidarity. I believed every human being had a right to artistic expression; everybody had an important story to tell. My own position as an immigrant made me aware of how privileged I was to have received an artistic education.

3 I attended the Escuela de Teatro at the Universidad de Chile in the 1960s. It was an exceptional institution, run and staffed by pioneer artists who were totally committed to creating a new, revolutionary Chilean theatre. They instilled in me a solid set of theatrical ethics, a deep love and respect for my actor’s craft, and a total commitment to my theatre work and all its ramifications. They made it clear that theatre was not just entertainment or a path to self-aggrandisement but a powerful tool for justice and social change, discovering life, and affirming humanistic principles. One of the important principles I learned from them was that I should always be open to learning, that I would never know it all, that my life in theatre would be a journey of discovery, of constant striving for elusive perfection.

4 In Canada, I found myself attempting to create theatre in a way that was still fairly unexplored: work with people who were not theatre professionals but with whom I shared the immigrant background. It was an extraordinary opportunity to learn experientially, from creating plays that communicated powerful, genuine, and aesthetically beautiful narratives of our difficult experiences as immigrants. My theatre education, with its strong ethical values, had prepared me for this challenge. I thank my teachers for giving me the necessary tools to face such a complicated task with equanimity.

I Wasn’t Born Here (1988) and Crossing Borders (1990)

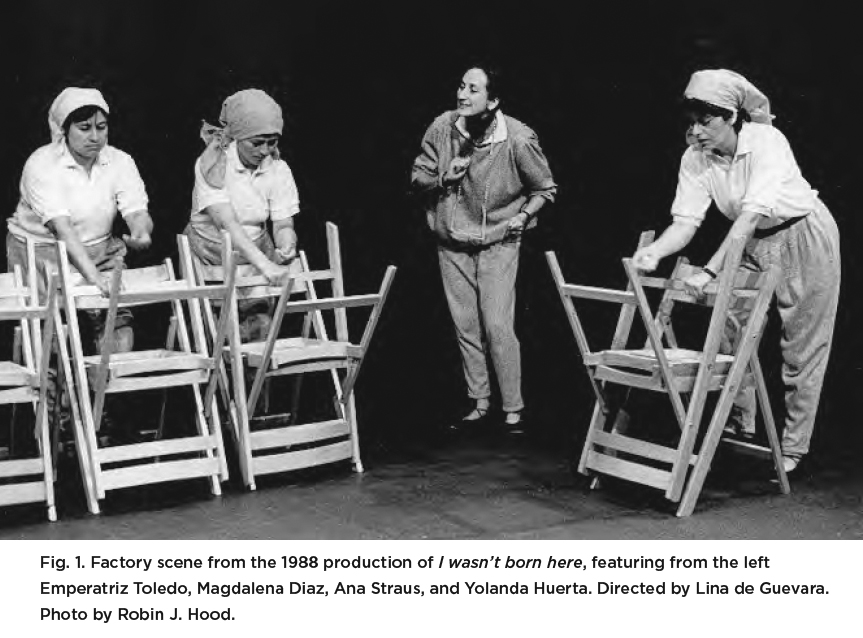

5 These were the first plays produced by PUENTE Theatre with performers who were non-actors and had limited knowledge of English. They were carried out with adequate five-month training grants from Manpower and Immigration, which provided a full-time salary for each participant and extra resources to pay for teachers, production materials, space rental, and other expenses. The main lesson here is that it is essential for the success of a project of this kind to be properly funded. These are demanding, life changing endeavours, and to succeed they need determination and talent from the performers and fair payment for their work that will allow them to invest the needed time and effort. These two plays were successful and unique in their scope because they had a strong financial basis. Unfortunately, Manpower and Immigration training grants no longer exist.

6 While directing I Wasn’t Born Here, I discovered that problems could become spurs. By overcoming apparent limitations such as lack of theatrical skills and English, we made discoveries, many of them artistic, expressive, and significant. The fact that we shared life experiences and backgrounds was essential: we were all immigrants from Latin America who spoke the same language. We presented a rich panorama of the diversity of the Latin American immigrant experience because we came from different countries and contributed different perspectives, customs, and traditions. We discussed extensively all aspects of the project and created a training program adapted to the needs and characteristics of the five participants. It included acting, improvisation, yoga, movement, voice, public speaking, ESL, immigrant issues, history of immigration in Canada, stagecraft, etc. We included other local Latin American immigrant women by interviewing ten women each, using a questionnaire that would elicit images, feelings, and anecdotes. These sixty interviews provided important material for the play.

7 The fact that the actors in I Wasn’t Born Here were really immigrants, talking with their own voices about their own lives, was something that truly touched our audiences. A door started to open for me. When I threw myself into this experiment, I was not at all sure how well it would succeed. As a theatre professional with years of training, I had to overcome my own prejudices about non-professional actors. I wondered how anyone could just come off the street and stand on stage with authority. I began to learn that a different approach was possible, and what seemed an obstacle could become an asset. I realized that with the help of an experienced director, a determined and courageous person, even without professional training, could create and perform in a show that would move, entertain, and enlighten an audience.

8 The women who took part in this project shared wonderful personal qualities: they had all gone through an ordeal to get to Canada, and were determined to tell their stories so that they could link themselves to their new environment, and be respected, not pitied. Their intuition was extraordinary; their sense of what was dramatic, poetic, and humorous, impeccable. For instance, they wrote several poems about their difficulties with English that lightened what was a harsh struggle; and their suggestion of including a Salvadorian traditional incantation against fear, as the sound background to a scene where a woman is contemplating suicide, was a poignant theatrical solution. I was constantly astonished about the truth and emotions they brought to the play.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 The Crossing Borders project told the stories of Latin American immigrant men. In it all the lessons from I Wasn’t Born Here were applied and were equally effective. The participants were members of Kumbia, a local Latin American band, and music was at the core of the project: singing, playing a diversity of instruments, composition, creation of lyrics, searching for appropriate Latin American songs and music, etc.

10 During the research and rehearsal of Crossing Borders, the differences between the experiences of Latin American men and women became clear. Women mostly came to Canada as part of a family; many had several children to care for. They discussed openly the problems in their family relationships, their feelings of homesickness, depression, and loss. Many of the men had come to Canada alone, some of them escaping from forcible conscription into the army, or because of political persecution. They were open to talking about most issues, but were reluctant to discuss their relationships with women, with their wives or girlfriends. They did not want to discuss this with me, a female director and an older woman. I realized that to push this topic would be counterproductive and would interfere with the positive relationship we had already established, but this became the inspiration for PUENTE’s third project.

Canadian Tango (1991)

11 My experience with the performers in I Wasn’t Born Here and Crossing Borders taught me that if you demand that non-actors go over their comfort limit, the project will become stilted and insincere or the participants will abandon it altogether. I learned that the director has to be sensitive: know how to expect results, but understand and recognize which are the limits that mustn’t be crossed. Therefore, in Canadian Tango, which deals with the touchy subject of how immigration affected the relationships of Latin American couples, I decided to work with trained actors. In Victoria, a small city with little diversity, there were no Latin American actors so I did this project in Vancouver. We followed the methodologies discov- ered during the first two projects: research in the community and appropriate training to create an ensemble and learn the dances required by the theme: i.e. tango (little known in Canada in 1991), mapalé, bolero, rumba, and other Latin American ballroom dances.

12 The research we did during this project uncovered the issue of family violence in the Latin American community: spousal abuse was a serious problem. We explored it in the play but decided to create another project specifically addressing the issue of family violence prevention, to raise awareness about the problem, understand it in depth, and propose solutions. This was one of the main ideas Canadian Tango brought us, and it signalled another direction for our work: using Theatre of the Oppressed techniques to address social issues. To complete my training I attended workshops conducted by Augusto Boal in Canada, US, and Brazil, learned from watching Headlines Theatre productions and in conversations with David Diamond and other practitioners. With time I would call my approach to Theatre of the Oppressed, Transformational Theatre: an integration of several techniques. I used this approach in other PUENTE projects: Vida Project and Familya, on family issues; Of Roots and Racism, Act Now Against Racism, Theatre Against Racism, Story Mosaic, etc.

13 As a theatre group that intended to show the experiences of immigrants to Canada, we could not ignore the many social issues that immigrants faced; we had to address them and develop our potential as a tool for positive change.

Familya (1992)

14 This play was about the relationship between Latin American immigrant parents and their adolescent children. To complete the research we organized image theatre and playback workshops. Over eighty interviews were compiled, and a play was created showing the many issues troubling immigrant families. We provided the community with a tool to discuss their own perspectives and opinions about issues that affected them deeply. I realized once again how influential our role could be, as catalysts for community discussion, consideration, and action.

Sisters/Strangers (1996)

15 In the 1970s and 1980s many immigrants came to Canada from Chile, El Salvador, Argentina, Nicaragua, Guatemala, etc. It was a time of great upheaval in that part of the world, and stories from Latin America, which PUENTE staged during its first years, needed to be told urgently, as the new immigrants sought solidarity and understanding. Later on, the immigrant population changed: immigrants and refugees were coming from Asia, Africa, the former Yugoslavia, the former Soviet Union, and other countries. It was time for PUENTE to present immigrants’ stories from all over the world.

16 All immigrant women living in Canada formed a community bound by location, gender, and situation. Directing and producing the community play Sisters/Strangers taught me much about diversity, adaptability, inclusion, and the benefits and perils of mixing theatre professionals and non-actors in the same production. I had to make a variety of artistic choices: using visual arts, music, and movement to include as many participants as possible and showcase the diverse cultural talents and practices they brought to the project. Finally, I learnt about the need to create a structure of support to facilitate participation: providing food, child care, travel money, translators, etc.

17 Applying the lessons of Sisters/Strangers we later produced three different versions of Storytelling Our Lives (1997, 2003, 2006), another community play that included a core of professional actors and choruses of immigrant women that changed in every city we toured.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2One-Person Shows

18 Something that introduced a change in our repertoire was the fact that, as time went by, children of immigrants started having careers in theatre, dance, music, etc. The issue for them was their identity. These young theatre people, mostly trained in Canada, demanded openness from the establishment; they wanted to see a clear picture of Canada as a multicultural society and the inclusion of other cultures. This is a theatre no longer about the immigrant experience, but about the experience of living in a society that encompasses so many cultures, an environment that is rich, but also confusing. Questions of identity become foremost. As immigrants we know very well who we are, but for the children and grandchildren of immigrants, identity is less clear.

19 For PUENTE, one-person shows proved to be an excellent way to showcase these young actors, eager to tell stories about living in two or more cultures. To date I’ve directed seven one-person shows. They were easy to move around and made it easier for us to participate in festivals and conferences. Five of them were written by the performers and I was the dramaturge.

20 Performers brought special skills to the show: singer and dancer Dana Hunter wrote about her multiple ancestry in Heinz 57 (2002); Raji Basi in Uthe/Athe (2004) is a dancer born in India; Grace Chan in Patriot In Search Of a Country (2006) is an opera singer of Chinese/Philippine parents; First Nation’s poet Krystal Cook wrote and performed in Emergence (2007); and Metis musician Rob Hunter created The Good Story(2008). With these last two shows we started including First Nations themes and performers in our repertoire. They added another dimension to PUENTE’s work and made me aware of Latin American immigrants’ complex relationships with indigenous people in Canada, which we explored in the “Journey to Mapu” projects.

Plays by Latin American or Spanish Authors Staged by PUENTE During the Time I was its Artistic Director (1988 to 2011)

21 These plays are still seldom included in Canadian repertoires. I felt the need to share their quality and interest. In our annual Worldplay program of staged readings from all over the world, we frequently included Latin American plays and I looked for those we could fully stage with our limited resources: Pastorela de Juan Tierra and The Pilgrimage of the Nuns of Concepción by Chilean Jaime Silva, Letters for Tomas by Chilean Malucha Pinto, The House of Bernarda Alba by Spaniard Federico García Lorca (co-produced with Full Spectrum Productions), Evita and Victoria by Argentinean Monica Ottino, and The Woman Who Fell From the Sky, by Mexican Victor Hugo Rascón Banda.

22 I learned how important it was to revise translations carefully, to update them and make sure they were correct. In many cases adaptations were essential for making the plays understandable in Canada. I was lucky to work with authors willing to accept my suggestions.

23 Each production brought many rewards, but I’ll just mention one of personal significance: The House of Bernarda Alba (1996) by Federico García Lorca. I revised the translation and workshopped and directed the play. It was an important experience for me. By concentrating exclusively on creating PUENTE’s original plays based on immigrant stories, I was not using my own knowledge and experience of great works created in other times and cultures, works that were so different from the mostly Anglo Saxon theatre that prevailed here. The House of Bernarda Alba gave me the opportunity to work with an author I knew well and loved, and introducing him to my actors. It was challenging to deal with a language, a temperament, and a history different from the one that surrounded me. Doing this work I experienced a surge of energy and creativity, a widening of our horizons. This project taught me that it was important to leave space in my work to attend to my own needs as an artist.

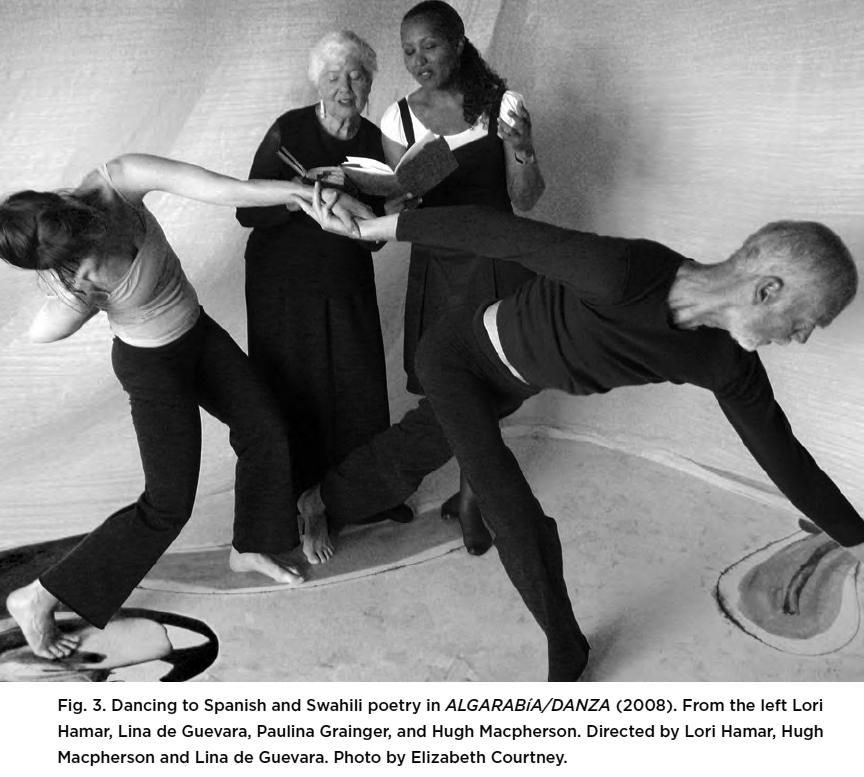

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Experimenting with the Use of Language in PUENTE Productions

24 Since the beginning I realized how important it was to include participants’ native languages in our productions. A few sentences, a poem, a song in Spanish gave a boost to the actors and to the audience, a taste of one of the most powerful challenges of the immigrant experience.

25 This interest in languages led us to the creation of Algarabía/Danza (2008) directed by Hugh McPherson, Lori Hamar, and myself. It was a dance/poetry spectacle that addressed in an unusual way the issue of the different languages present now in Canadian society. This production had dancers improvise movement to the sound of poetry read in a variety of languages: Japanese, Swahili, Russian, Spanish, Chinese, Cree, Old English, French, Tamil, etc. The dancers did not know the meaning of the poems. We agreed that the important thing was the sound of the words and the feelings vocalized by the readers. Language became like music, separated from factual meaning.

26 We discovered that the audience, which at the beginning was taken aback by not being offered translation, became exhilarated by the freedom from analytical thought they experienced when they yielded to enjoying their senses: seeing the movements, hearing the sounds, and experiencing the mystery. Multilingualism on stage offers exciting possibilities. We are barely starting to explore them. Algarabía/Dance was one of these explorations.

How I Told My Immigrant Story in Theatre

27 During the thirty-eight years I have lived in Canada, I have seen “immigrant theatre” go from being a marginalized curiosity to a vibrant, complex movement that involves many excellent theatre people. Aspects of it are extensively discussed, among them the question of how to tell these stories, what forms and styles are to be preferred. We are seeing plays about diverse cultures, non-traditional themes, an acceptance and enjoyment of other theatrical forms and traditions. It is a positive trend, but one that can lead to confusion and dissension.

28 I believe we must welcome and support a variety of theatrical expressions. Not only the formal Eurocentric style of theatre presented in an adequate building, with classically-trained performers and a three-week run, but also community events and festivals; projects that use theatrical tools to achieve the transformation of individuals and organizations, such as theatre in prisons, hospitals, and community centres; theatre that happens in parks, in abandoned buildings, in buses, or on street corners. There is much richness there. These types of projects have suffered discrimination, and organizations that supported and encouraged them such as the Canadian Popular Theatre Alliance, or the Women in View Festival, have disappeared. This is a great loss.

29 By definition immigrant theatre is about people who are yearning for better times, who have had to leave their homelands, because of war, poverty, and turmoil. My work has been about the dispossessed: a theatre of denunciation, of renovation, of change. I believe that theatre for elites ends up being anemic, disconnected with reality, without energy. And even though sometimes there’s exquisite expertise in it, it becomes pointless when the content is vacuous.

30 Every project I engaged in suggested its own style. I experimented with a variety of forms: plays that asked for audience participation, physical theatre, image theatre, theatre-forum, storytelling, storytelling and film, playback, improvisation, parades, giant puppets, solo shows, plays with large casts, and plays with traditional Western style staging.

31 Going over the many lessons received from PUENTE projects, I realize that my teachers were absolutely right: It has been a never-ending journey of discovery that continues to this day. My personal journey of learning through theatre is not over and I look forward to the new chapters. I will also continue to review the old ones and reflect on their many facets. Sharing this experience with other theatre practitioners and scholars has been extremely valuable to me.