In his work on discourse in the novel, Mikhail Bakhtin defines the aesthetic value of literature as arising from the dialogical interdependence of two equal and separate consciousness: that of the author and that of the character, each taking on a distinct spatial/temporal form (“Author” 87). The device of heteroglossia—a conflicted co-existence of distinct narrative voices within a unified literary utterance— makes this tension of author/character relationships visible. Characterized by “a diversity of social speech types” and “a diversity of individual voices, artistically organized,” heteroglossia defines the authorial utterance and the character`s speech as a territory for many voices to interfere and compete within (Bakthin, “Discourse” 262). By analogy, Meerzon argues, Bakhtin’s theory of heteroglossia and his view of the author/character interdependence can illuminate the complexity of an authorial utterance in the immigrant solo performance, in which the voice of the author, the voice of the performer, and the voice(s) of the character(s) are simultaneously diversified and intertwined. The product of a certain social and cultural environment, such performance reflects the “internal stratification present in every language at any given moment of its historical existence” (263); yet through the performative gesture of telling one’s personal story on stage, a delicate balance between the performer’s identity and her artistic work is suggested. As her example, Meerzon turns to the work of Mani Soleymanlou, a Quebecois theatre artist of Iranian origin, Trois. Un spectacle de Mani Soleymanlou, which traces the ontological and fictional difference between the immigrant author, character, and performer on stage.

Dans ses écrits sur le discours romanesque, Bakhtine conçoit la valeur esthétique de la littérature comme découlant de l’interdépendance dialogique de deux consciences égales et distinctes : celle de l’auteur et celle du personnage, chacune ayant une forme spatio-temporelle distincte (« Author and Hero » 87). L’hétéroglossie —la coexistence conflictuelle de voix narratives distinctes dans un énoncé littéraire unifié— rend visible cette tension entre l’auteur et ses personnages. Caractérisée par « une diversité de langages sociaux», et par « une diversité de voix individuelles littérairement organisée » l’hétéroglossie inscrit la parole de l’auteur et les propos des personnages dans un territoire au sein duquel plusieurs voix peuvent intervenir et rivaliser (« Discourse » 262). Par analogie, nous dit Meerzon, la théorie bakhtinienne de l’hétéroglossie et sa réflexion sur l’interdépendance de l’auteur et de ses personnages nous aide à mieux apprécier le caractère complexe de la parole de l’auteur dans le contexte d’une prestation solo par un immigrant, où la voix de l’auteur, celle de l’interprète et celle(s) des personnages sont à la fois diversifiées et étroitement liées. Produit d’un environnement social et culturel donné, une telle prestation donne à voir «la stratification interne présente dans chaque langage à tout moment de son existence historique » (263). Et pourtant, dans ce geste performatif qui consiste à raconter sur scène sa propre histoire, on devine un équilibre fragile entre l’identité de l’interprète et son travail artistique. Afin d’illustrer son propos, Meerzon se penche sur une pièce de Mani Soleymanlou, un artiste de théâtre québécois d’origine iranienne, intitulée Trois. Un spectacle de Mani Soleymanlou, laquelle trace la différence ontologique et fictive entre l’auteur, le personnage et l’interprète immigrants sur scène.

1 In his work on discourse in the novel, Mikhail Bakhtin defines the aesthetic value of literature as arising from the dialogical interdependence of two equal and separate consciousness: that of the author and that of the character, each taking on a distinct spatial/temporal form (“Author” 87). In literature the author occupies the place of the I, whereas the character takes the place of another, as determined by the author’s external position to it (14). The device of heteroglossia—a conflicted co-existence of distinct narrative voices within a unified literary utterance—makes this tension of author/character relationships visible. Characterized by “a diversity of social speech types” and “a diversity of individual voices, artistically organized,” heteroglossia defines the authorial utterance and the character’s speech as a territory for many voices to interfere and compete within (“Discourse” 262). By analogy, I argue, Bakhtin’s theory of heteroglossia and his view of the author/character interdependence can illuminate the complexity of an authorial utterance in autobiographical solo performance, in which the voice of the author, the voice of the performer, and the voice(s) of the character(s) are simultaneously diversified and intertwined. The product of a certain social and cultural environment, a performance text of an immigrant artist’s autobiography reflects the “internal stratification present in every language at any given moment of its historical existence” (“Discourse” 263); yet through the performative gesture of telling one’s personal story on stage, a delicate balance between the performer’s identity and her artistic work is suggested.

2 As my example, I turn to the work of Mani Soleymanlou, a Quebecois theatre artist of Iranian origin. I focus on his theatrical trilogy, Trois. Un spectacle de Mani Soleymanlou, which premiered at the Festival TransAmérique in June 2014 in Montreal.2 The published script (2014) documents the author/performer’s attempt to reconstruct the process of making and performing this solo on the page (hence subtitled “un spectacle de Mani Soleymanlou”). It also traces the ontological and fictional difference between the author, the character, and the performer on stage in order to reveal the fundamental devices of an autobiographical solo performance.3 In Trois, the actor appears in the multiplicity of the author/character/ performer relationships, as:

- Mani Soleymanlou—a Montreal based artist of Iranian origin;

- Mani Soleymanlou—a creator (Bakhtin’s author) and a performer of the immigrant solo play; and

- Mani Soleymanlou—a fictional narrator, who tells the story of Mani, le personnage principal.

Spoken in French, English, and Farsi, in its performative and dramatic heteroglossia, Trois reflects the translingual practices of immigration, based not necessarily, as linguist Suresh Canagarajah argues, on the interlocutors’ grammatical ability but rather on their “performative competence, that is, what helps achieve meaning and success in communication” (32). The translingual practice occurs in what Canagarajah calls contact zones of communication, which appear in those spaces of contact where “diverse social groups interact” (26). Such contact zones can be found both on the streets of the multicultural Montreal and on stage, when the languages that make up an immigrant artist’s lingo meet and interact in the performative gesture of communication: the communication that happens in the fictional world constructed by this artist and the communication that takes place between the stage, the multi-lingual performance space of the actor, and the audience.

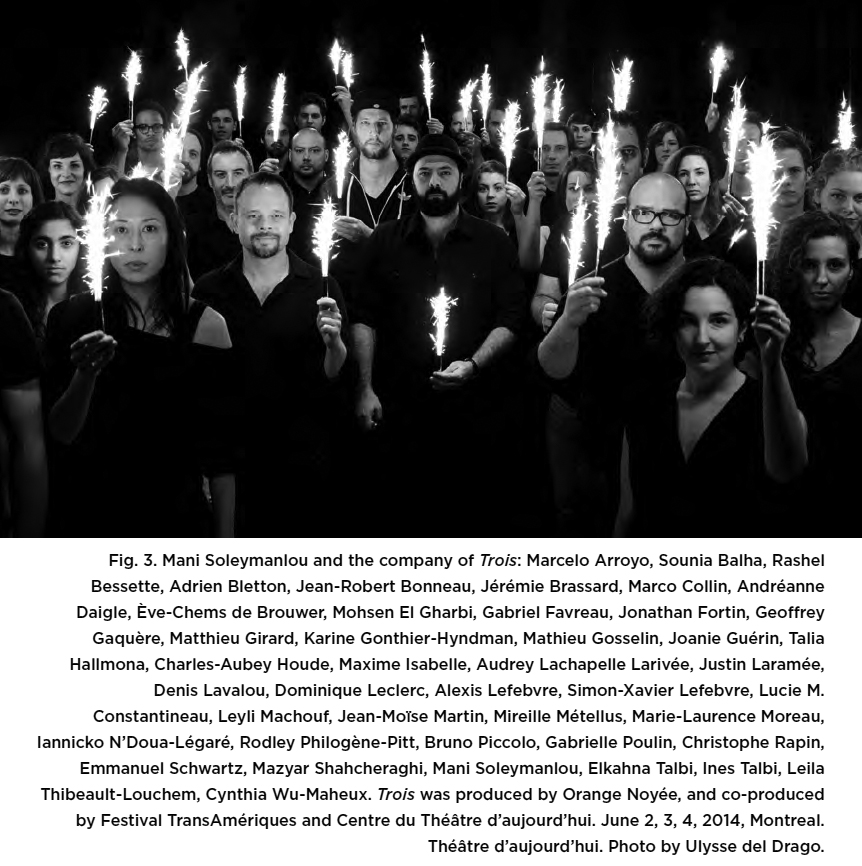

3 As a political and artistic manifesto, Trois. Un spectacle de Mani Soleymanlou demonstrates how the translingual practices of immigration determine the artistic, the political, and the interpersonal contact zones of communication, in which this immigrant artist functions. The trilogy opens with the play Un, in which the author/narrator Soleymanlou tells a story of the character Mani, who grew up in a multiplicity of cultural and linguistic settings in Tehran, Paris, Toronto, and Montreal.The second part, Deux, features an encounter between the Iranian-Canadian-Quebecois Mani Soleymanlou and the Quebecois Emmanuel Schwartz (Manu), whose father is an Anglophone Jew and mother is a Francophone Christian. The trilogy closes with the symptomatically-named part Trois, a manifesto performance created by forty-three immigrant theatre artists living in Quebec. The trilogy’s closing monologue is spoken by Marco Collin, an indigenous person, who proposes his own scenario of immigration, now in one of the Inuit languages:

In the Canadian context, this monologue reminds us: immigration, displacement, losing home, and seeking a new one condition every voice. Together with Soleymanlou, Collin insists that recognizing and accepting the interpersonal heteroglossia of our cultural and linguistic performances is the only way to reconcile our differences.

4 Although in this article I can only touch on the significance of Soleymanlou’s project of staging alterity, I wish to demonstrate that immigrant performative practices can serve as a binding element in Canadian and Quebecois theatres of the future. A powerful institute of culture and education, able to speak to the country’s multi-lingual and multi-ethnic spectatorship, immigrant theatre describes a dialogue arising at the boundaries of the culture of the dominant and that of the immigrant, across languages, theatrical genres, and generations. Soleymanlou’s work demonstrates that the immigrant’s experiences of displacement and linguistic othering mark a new Canadian and Quebecois dramaturgy and theatre. This article argues, therefore, that in today’s climate of political shifts, it is time to seriously rethink the position of an immigrant theatre artist as a richly symbiotic, cosmopolitan subject able to challenge the administrative and financial governing structures of the country by practicing “mimesis of appropriation” (Imbert 25).

5 I use Bakthin’s theory of the author/character interdependence, Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the gesture of becoming, and Lise Gauvin’s notion of la surconscience linguistique, to define the act of émigré writing as the “act of language” (Gauvin 8-9), the gesture of identity reassertion in performance. Gauvin’s theory becomes indispensable in my analysis of Soleymanlou’s many-lingual performative utterance, which he constructs as he ponders political, social, and artistic debates in Quebec concerning the position of French in North America, surrounded by other languages and other cultural contexts. In Quebecois literature, as Gauvin explains, “the proximity of other languages, a diglossic situation in which a writer often finds himself immersed, the first deterritorialization constituted by the passage from the oral to the written form, and another, a more insidious kind, created by readers close by and those far away, separated by different histories and by different linguistic and cultural baggage” creates a particular cultural and linguistic context, which “forces the writer to resort to detour strategies” (9). These strategies manifest themselves in the processes of translating and adapting vernacular French to the new literary idiom, “often referred to under the title of multilingualism and textual heterolingualism” (Gauvin 9). These processes also create the situation of linguistic estrangement, a condition familiar to many writers (Sartre, qtd. in Gauvin 11), but very specific to the Francophone author residing in North America:

This quest results in creating l’esthétique du divers (11), rooted in what Derrida identifies as the writer’s imagining or dreaming in the language of the other (qtd. in Gauvin 13). The same search characterizes the historical and contemporary quest of Quebec literature, including the work of its immigrant writers. Although I recognize that Soleymanlou’s artistic pursuit is less about seeking the new French, the language of immigration, and more about performing it, aiming at providing the artist-immigrants with a theatre stage to speak their mind on (Personal interview), I find Gauvin’s concept useful, specifically when applied to the stories he tells, the historical references he makes, and the performative devices he chooses.4 In its structure, the article follows Bakthin’s categories of author/character interrelationships. First, I discuss the genre of the autobiographical solo performance in relation to Soleymanlou’s work. Then, I examine the author/character performative and aesthetic activities in the trilogy. In the concluding section, I analyze how Soleymanlou’s onstage heteroglossia is echoed in the multi-lingual and multi-cultural auditorium of today’s theatregoers.

On Author and Character in the Aesthetic Activity of an Immigrant Solo Performance

6 Deborah R. Geis argues that “postmodernism has theorized a fragmented and dislocated speaking subject that is more open to replication and dissemination [. . .] than it is to the dynamic of response inherent in dialogue” (2). As a result, contemporary dramatists “have turned toward the monologue as a way of ‘speaking’ about the attempt to enter subjectivity” (3). Similarly, a voyage of immigration stimulates one’s dialogue with one’s self and reinforces heteroglossia as the traveler’s subjectivity. Based on a constant remapping and refashioning of self, the condition of immigration drives one’s performative behavior. It forces an immigrant artist to seek newer means of artistic expression and often acts as this artist’s therapeutic tool. The trauma of displacement and identity crisis frequently become the subjects of such artistic investigation, the feature, as Jenn Stephenson tells us, common to any type of autobiographical solo show, in which “crisis is featured frequently [. . .] yielding stories of disaster” (“Portrait” 51). At the same time, “crisis can also manifest as a dramaturgical strategy. With regard to the dramaturgy of solo performance, the dual identity of the performer as both actual writer/performer and fictional narrator/protagonist allows for potential interaction between these two subject positions” (51). Specifically, an immigrant solo performance relies on the rhetorical features of a dramatic monologue, including the effects of natural speech, repetitions, interruptions, and everyday vocabulary. It presupposes one voice multiplied by many, reflecting the cognitive and performing processes that make up an immigrant artist’s self. The “I speak therefore I am” principle functions as an act of personal re-assertion; so the distance between the author and the speaker is challenged, whereas the identity of the author is collapsed with that of the character.

7 Characterized by Bakhtin’s understanding of double-voicedness as simultaneity (“Author” 9-10, 22), an immigrant solo performance functions as an expression of the author’s deeply “subjective situation” (Howe 15); and it emphasizes the dramatic qualities of a monologue, when “the speaker is in conflict not [only] with the external world but with himself” (13). Solitude, the foundation of the monologic speech, conditions the author’s voice, the characters’ voices, and those of the (in)visible addressee, fused together and diversified at the same time. Thus, the monologicity of the authorial consciousness turns into a dialectical, heteroglossic structure, characterized by temporal and cognitive simultaneities. Here, the stratified utterance of the narrator reflects the fragmented experiences and mobile identity of an immigrant subject. The exilic artist’s voice reproduces the familiar to her tones of the languages, the cultures, the traditions, and the histories.

8 Adramatic monologue is also characterized by an intricate temporal framework of storytelling (Benjamin 83-85). In immigrant solo performances, the past experience of the narrator, the “experiential time of the journey,” is reflected in her present, the time of the narration or the performance itself. Such performance insists on the value of performative encounter, the peoples’ “ability to exchange experiences” (83). The audience witnesses the personal time of the narrator collapsing into the personal time of the character, so the solo can spotlight the bio aspects in the autobiography. However, unlike autobiographical theatre, in which the auto “signals the sameness of the subject and object of that story—that is, the ‘author’ and ‘performer’ collapse into one another as the performing ‘I’ is also the represented ‘I’” (Heddon 8), the work of an immigrant artist casts its gaze not necessarily on the artist herself but on her cultural heritage. As Attarian suggests, “the autobiographical act is essentially one of memory reconstruction. By reconnecting ourselves with our pasts, we literally reconstruct layers of our lives. The re/membering carries with it not only a sense of recreating the past, but also, consciously and unconsciously, creating a new past in the present” (185). An immigrant artist often finds herself, much like Lot’s wife, gazing back at what has been left behind. This search for the lost past and the artist’s process of remapping herself in the present produces another layer of onstage heteroglossia, which then functions as an immigrant theatre artist’s affirmation of her professional and cultural difference. By asserting a sense of professional dignity and pride, this artist insists on synechism as the stylistic idiosyncrasy of her work, so the productions she makes appear as a result of amalgamation of one’s inherited cultural traditions and those of a new world. These productions stage the tension between continuity and difference. They present an immigrant artist’s search for a professional homeland, which “transcends cultural specificity and encourages the development of an identity that is formed from living in the theatre rather than a society” (Turner 23).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 In Soleymanlou’s Trois, all basic features of an immigrant solo performance are brought together by the unifying power of his artistic utterance, the heteroglossia of the author’s voice. It stages “a coming-of-age and a coming-to-terms story where Mani Soleymanlou seeks an answer to a question that’s been on his mind all his life: ‘How can you feel Canadian and still be one with where you come from?’” (“Playwright’s Note”). In the first part of the trilogy, he investigates how the hybrid Self of an immigrant artist is constructed: in 2009, Théâtre de Quat’sous and its cultural initiative “Les lundis découvertes” invited a group of immigrant theatre artists to create plays about their home countries. Without hesitation, as the play tells us, Soleymanlou accepted this task, only to very quickly discover that he had no proper memory or knowledge of Iran (Trois 19-20)—a conundrum familiar to that faced by second generation Holocaust survivors and many immigrant children who grew up in the country of their parents’ migration (Hirsch). When he attempts to share the complexity of Iran’s history with his Quebecois audiences, Mani quickly realizes that he does not own his story. The only tale he can share is the meltdown of his ascribed linguistic identity, a story of his own uprooting and his multiple cultural identities. The disorderly heteroglossia of his immigrant self takes over the stylistic unity of the solo. The final monologue is a mix of French, English, and Farsi, which illustrates how the heteroglossia of immigration prepares and characterizes Soleymanlou’s artistic statement. As a result, the hybrid Self of the artist, Mani Soleymanlou, “a Torontonian/Arab/Iranian who has lived in France and Ottawa” (Trois 18), and his performative presence appear heteroglossic too.

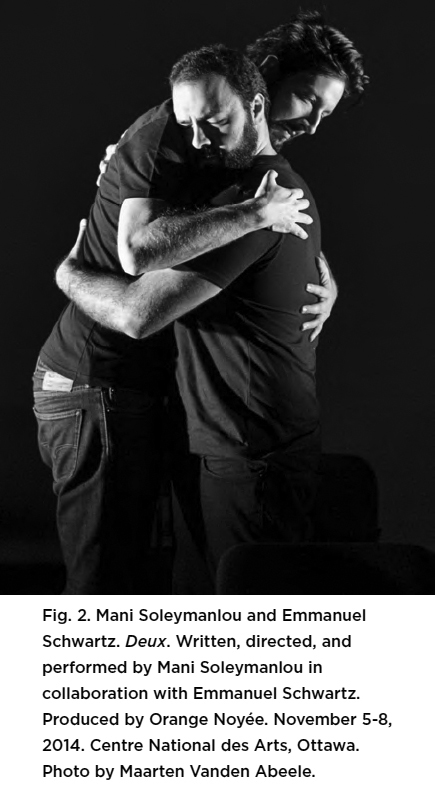

10 In the second part of the trilogy, Deux,

11 Soleymanlou takes this idea further, to artistically investigate the interpersonal heteroglossia of the new friendships an immigrant subject creates. Deux meticulously follows Un in its performative structure, this time with Emmanuel Schwartz picking up Soleymanlou’s lines, trying to tell the story. The task proves to be impossible. When Mani invites Emmanuel to recognize his own identity as Other and to tell his own tale of difference, Emmanuel declines the offer and explains that instead of cultivating another show in the “identity theatre” genre, he aspires to work with Mani as his friend and creative ally on such subjects as love, death, and friendship (Trois 106-7). Neither one dares to pick up the pathos of this statement, and so the play ends with a joke, another immigrant name is evoked and another comment on the process of performance making is made. The audience is invited to witness the onstage heteroglossia, with each character/performer reasserting himself as Canadian and as Other, evoking the childhood memories of estrangement and humiliation, the moments of realization of one’s own difference. Such a device indicates that each character possesses the mechanisms of resistance to alienation; however, neither is prepared to share them with others. “The two solitudes” move alongside one another, ready for but never embarking on a truly creative dialogue.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

12 The concluding part, Trois, takes the device of heteroglossia even further. By featuring forty-three artists of different cultural and linguistic origins, ready to share their experiences and stories, this show evokes the social heteroglossia of the cultural and linguistic mosaic that marks today’s Quebec. Soleymanlou’s raison d’être with this show was to give an opportunity to the Montreal actors of diverse origins to express their points of view and to engage with the form of monologue. He asked future participants to fill out a questionnaire on identity politics, language rights, and culture in Quebec, the texts that became the core of Trois’s performance.5 As a result, each utterance featured in Trois refers to multiple realities and oscillates between several languages. Together, as Soleymanlou explains, these artists “summon chaos, arguments, discord. There’s no happy ending with everyone holding hands [. . .] We are alone together. What unites us is our feeling of solitude, especially in an era that makes a virtue of the ego and the self” (“Interview”). Together, the forty-three characters evoke another paradox of today’s world: the chorus of immigrant solitudes creates a theatrical tableau of new globalized citizens locked up in their personal stories and seclusions, whether they wish to be such citizens or not.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3On the Author’s Dialogic Self in Soleymanlou’s Immigrant Solo Performance

13 Constructing the Other—an immigrant—begins with giving her a name. “Mani Soleymanlou” is an unusual and difficult name to make out, something that the director of the National Theatre School in Montreal points at, to then proudly tell her new student that “we have received the federal government’s grant for newcomers” (Trois 17), suggesting that he should profit from the generosity of his new country. “Newcomer…,” Mani reacts, “it has been 14 years since I moved to Canada… And since then, since that first day at the National Theatre School of Canada, since my arrival in Quebec, I’ve never been anything else, but a guy from elsewhere, a stranger, an exile, lost, an immigrant” (Trois 18). Thus begins the story of a young theatre maker forced to become a “professional immigrant”; it is a story of humiliation and pride, of fashioning self as other.

14 To Lise Gauvin, the term professional immigrant (207) refers to the work of an immigrant writer, whose career has been unfolding in proximity to a new language, and whose choice of writing in one language or another has been conditioned by displacement. In this article, I take the term further to define the work of theatre professionals forced to seek refuge and professional employment in a new land. In the professional immigrant scenario, the relationships between a newcomer and her adopted country are simultaneously “destructive and creative” (Memmi 89); so some artists accept the label and work within it, often opting for such popular theatre forms as comedy and melodrama. In such theatre practices, a character “immigrant” might be presented as different but familiar: this character can function as comic relief, in situations where actions, beliefs, and accent emerge as automatized and rigid follies, and hence the source of laughter (Bergson 5). Thematically, such plays often rely on presenting the intergenerational father/son conflict, so the situation is made even more familiar to the average theatregoer.6

15 One can recognize a clear “anti-immigration” project, similar in its political and artistic quest to the post-colonial one (Memmi 88-89), in the work of Alexandre Marine, Teo Spychalski, and Wajdi Mouawad in Montreal, or Soheil Parsa in Toronto, to name a few, refusing to subject their projects to the professional immigrant theatre stereotype. These artists do not very eagerly embrace their audiences’ popular tastes, seeking to direct and act canonical repertoire, from Shakespeare to Beckett. They rely more deeply on the dramaturgical principles of tragedy and they insist on creating theatre in immigration as a form of highbrow culture.

16 Genre-wise, Mani Soleymanlou’s work falls somewhere in between. On the one hand, he tells a sadly familiar story of immigration, with the protagonist—a theatre-maker immigrant—who has a clearly identifiable Middle Eastern name and looks, sounds different, and refuses to do anything but theatre. He questions national history and heritage, the issues of political and social identity, and the problems of language loss and acquisition, hence taking his audience beyond easily detectible tropes of an immigrant family problematic. On the other hand, his work builds on the devices of comedy. Un, the first part of the trilogy, opens with a comic account of the character Mani’s personal story to unfold as the author Soleymanlou’s serious engagement with the history of Iran and with his task to convey it artistically. The character grows angry and anxious in his frustration with human-made evil. When it comes to the history of warfare or religious practices in Iran, he holds no romantic illusions. When he is subjected to cultural and racial stereotypes in the professional milieu of Montreal theatre, he has no idealistic misapprehensions either, so he opts for the devices of irony and humour to push the angst away. In Soleymanlou’s work, humour becomes “therapeutic, incisive, democratic and provides [the artist] with the vision of the world as a great opening, great adventure” (Ruprecht). Between bursts of laughter, the show introduces us to the ethical and emotional turbulence many immigrants experience, torn between the necessity to negotiate their places in a new country and the need to keep a memory of home. Indeed, Soleymanlou uses laughter to bring the pain of immigration closer to his audiences. The scenario the trilogy stages rejects the paradigms of nostalgia and suffering. It rehearses Soleymanlou’s artistic and political strategies to shake the stereotype. Creating new theatre spaces to feature the multitude of voices that make up the Montreal’s social mosaic, challenging the canons of Quebecois dramaturgy, and questioning the practices of typecasting7 is the focus of Soleymanlou’s project.

17 By no means am I suggesting that Soleymanlou is deprived of working in established Quebecois companies.8 Still, it is only in the framework of his own authorial utterance and hence in the productions of his own company Orange Noyée /Drowned Orange (established in 2011), where Soleymanlou can put forward his artistic and ideological project, namely challenging the exoticism and the stereotyping that the word “immigrant” carries.9 In Trois, he openly capitalizes on the “professional immigrant” scenario. Despite consciously rejecting his Iranian identity (“I left it behind at the airport”) and after ten years of living in Quebec, Soleymanlou knows he is still often perceived as an outsider (Trois 103). In response to this situation and also reacting to the 2013 Charte des valeurs québécoises,10 he declares: “I take advantage of [this perceived difference], I fill the houses, people come to see me [. . .]; [I say] ‘my duty as an artist, as an Iranian, as a citizen’. A phrase from my grant application for Un” (103-4). In this aside, Trois exemplifies the immigrant artist’s commentary on the personal mechanisms of becoming that mark the immigrant self, as well as on the social, cultural, economic, and performative strategies of making the figure of “immigrant.” As Soleymanlou explains,

Certainly, seeking its own reassertion as an independent nation with its own cultural and linguistic traditions, Quebec remains—in life and on stage—less open to accepting new faces and new sounds as its own. So the trilogy presents Soleymanlou’s response to the realization of his perceived difference as an enforced identity. It reveals that immigration remains one’s highly personal endeavour, a lesson about one’s self, language, and culture. In the article “Rajoutons des souches, ‘Profession : Immigrant’,” Soleymanlou explains his position further:

It is not surprising that Soleymanlou concludes this article with the description of the 2012 student manifestations in Quebec, the time and place when he for the first time in many years felt “at home” in Montreal, since nobody in this crowd of differences asked him the symptomatic question: who he was and where he belonged (“Rajoutons” 28-29).

18 In the structural make-up of a solo performance, “this separation of personae permits dialogue between inside and outside views of self, between subjectivity and alterity” (“Portrait” 51). Soleymanlou’s project rests on these narrative separations. It consists of three identically structured parts, alternatively situating the narrator within and outside the story. The voices of the fictional characters from the author’s past and present, the historical figures of Iran, and the people of Montreal make this narrative multi-layered and multiperspectival. In the referential simultaneity of these voices and narratives, the project suggests the paradigm of an immigrant identity found in the processes of multiplication, in the gesture of becoming (Deleuze 39-41), and in the act of difference, as a form of mediation stemming from “the fourfold root of identity, opposition, analogy, and resemblance” (29). Without necessarily referencing Deleuze, Soleymanlou arrives at a similar conclusion: in Un, he juxtaposes the recent revolutionary upheavals in Iran with people protesting on the streets, a young girl killed, and many others fleeing the country, with his own experiences of driving his father’s car in the streets of Toronto (Trois 22). The play ends with the author/narrator refusing the geopolitical concept of nation state as the time/place of his belonging. Mani accepts his ethnicity—Persian—as the marker of his personal nation state, with the heteroglossia of his speech taking over the idiosyncrasy of his Self (38). This sentiment is echoed in the second part of the trilogy, Deux, as well:

Hence, in Soleymanlou’s immigrant solo performance, the voices of the actual and implied addressees mix with the voice of the author/narrator and with the voice of the character/performer. This fusion creates the play’s special authorial heteroglossia.

On Stratification of Character’s Self in Immigrant Solo Performances

19 An immigrant, much like a colonial subject, recognizes the language of an adopted country as the attribute of a new (to her) cultural, symbolic, and economic power (Derrida 42-43). Mastering this new language is a quest that all immigrants share. Despite the fact that Soleymanlou is well acquainted with this formula, he challenges it in Trois, demonstrating that many immigrant children destabilize the immigrant language/power paradigm. Early geographical and linguistic traveling grants these children mobile identity (Bauman 21), which allows them to eventually occupy what Bhabha calls the third space of enunciation, “which makes the structure of meaning and reference an ambivalent process” (37). These children grow up in close proximity to the language of the master by learning it at school and in the streets; and maintain complex relationships with the language of their family. Depending on how a child sees this condition of linguistic flux, the language of power can be accepted, rejected, or negotiated. Thus, for people of multilingual and multicultural backgrounds, the power and the centre are constantly floating. The more languages and cultural codes one masters and the earlier an immigrant subject begins to move from one culture to another, to experience shifts in linguistic and symbolic power, the more scenarios of negotiation she acquires. Such a transnational subject breaks the immigrant binary of here/elsewhere and bypasses the dichotomy past/present of those who change the country of habitat as fullyformed adults. For someone like Soleymanlou, whose identity is always fluctuating, the binaries turn into simultaneities marked by the inner heteroglossia of the artist’s self and by the outer heteroglossia of different present[s] that make his artistic and everyday milieu. As Edward Said explained, “in our age of vast population transfers, of refugees, exiles, expatriates and immigrants, it can also be identified in the diasporic, wandering, unresolved, cosmopolitan consciousness of someone who is both inside and outside his or her community” (53- 54). As if jumping off Said’s argument, Soleymanlou states that traveling makes it possible to see oneself and one’s work from a new perspective, in the estranged mirror of other cultures: “They say I’m Iranian, but is that what I really am, compared to them? I wonder why sometimes I feel really, really more like a Montrealer—how I can ‘forget’ that I’m Iranian? [. . .] I leave the personal in order to speak about the universal, or at least speak about this state of floating identity that ultimately can touch people of all origins” (“Playwright’s Note”). Such a scenario exercises the uncertainty principle of heteroglossic being, illustrated in the multitude of voices that “furnish” Soleymanlou’s artistic utterance. For Soleymanlou, as for many children who grew up as immigrants, the idea of hegemonic, singular identity does not exist. The artist easily switches from French to English, to Farsi and back, every time choosing the linguistic idiom most suitable to the given fictional situation or the dramaturgical needs of the action. The work of trilogy, Mani explains, is “the amalgam of different cultures and cities where I have lived that make me the human being I am, instead of the colour of my skin, my accent, or the sound of my name” (“Playwright’s Note”).

20 This circumstantial heteroglossia is also contextual or macaronic (Gauvin 199). The voices that make up the narrative tapestry of the trilogy multiply not only within Mani’s personal speech, but also by referring to the events of Iran’s recent history and its major players: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919-1980), the Shah of Iran (1941 -1979), overpowered by the 1979 Islamic Revolution; and Ruhollah Khomeini (1902-1989), the leader of the 1979 Revolution. In Deux, Mani and Emmanuel evoke the multitude of Montreal’s voices. In Trois, the fortythree performers bring on board the echoing of forty-three immigrant stories, the device that makes this narrative not only heteroglossic but almost mythical. In the trilogy’s performance text, however, these historical voices appear distorted. Engaging with the onomatopoetic potentials of the French language, in Un, for example, Soleymanlou turns the Shah of Iran into le chat/the cat; and Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, into le chien/the dog, to mimic their political disagreements through a symptomatic exchange of meows and woofs. In this grotesque distortion of the Iranian leaders, Mani presents himself as an angry commentator on the country’s recent history, joining with Iranian dissidents and political activists, some of whom, like Mani’s family, had to flee Iran during the early 1980s. Hence, in its multilayered structure of meanings, the trilogy also explores political exile, if not from the perspective of the exilic subject then as a mediated experience, i.e., from the perspective of the child of a political exile. Mani’s depiction of Iran’s leaders as bickering domestic animals is an example of this child’s inherited anger with and disengagement from the land of the ancestors. Part One “Moi” finishes with Mani’s ironic observation: the war that followed the 1979 revolution killed and forced many people to flee. Seventy percent of today’s population of Iran is younger than thirty years old—all because of that war’s casualties. But those who escaped remain grateful: “children, replacements of those who died for them. For us. Men and women, who one day will claim what is rightfully theirs” (Trois 30). This apprehension of the inherited survivor guilt—those who died will claim one day what is theirs— marks the artist’s inability to emotionally connect to the country of his origins. This emotional disconnectedness and self-directed anger forces Soleymanlou to use the devices of meta-theatricality. To continue working with these historical images and contexts would lead him to theatricalization of collective memory, as well as objectification, fictionalization, and stereotyping of a communal history. Mani refuses to take this road and declares that he is not Iranian but Persian. His appearance and knowledge of the language, Farsi, remain the only indicators of his ethnic identity.

21 In Deux and Trois, Mani’s anger is redirected at cultural politics in Quebec. Unlike Un, which sought a coherent story as its unifying dramaturgical gesture, Deux does not aim for monologicity. It insists that onstage “erasing all the conflicts and failures with a unifying tone holds no interest, and it kills theatre” (“Interview”). In Deux, irony, fragmentation, selfcommentary, faking accents, and making jokes about local customs and quirks function as a form of estrangement. The objective is to reveal the hypocritical tendencies in a society, which simultaneously creates individuals of multiple identities and refuses to acknowledge them. Trois continues with the same logic but suggests that collective identity is never monolithic, specifically if the majority of immigrants identifies, as Soleymanlou does, with the country of their residence as the country of their belonging—the statement made in French, English, Farsi and other languages, the forty three performers speak (Trois 151-62).

22 This separation of the author/character’s consciousness within Soleymanlou’s performative utterance serves as a convincing example of Bakhtin’s narrative logic. In literature, he writes, the building material belongs to the dual sphere of linguistic expressions and an author’s consciousness (“Author” 196). A writer presents an ontological totality made of her outer body/voice and her consciousness, which includes “a human being’s possible and actual self-consciousness” (100). In theatre, the processes are different. Located outside her stage character, a performer turns into a contemplator/commentator of the action and so becomes its author as well: “The actor is aesthetically creative only when he produces and shapes from outside the image of the hero whom he will later ‘reincarnate’ himself [. . .] the actor is aesthetically creative only when he is an author—or to be exact: a co-author, a stage director, and an active spectator of the portrayed hero and of the whole play” (76). Bakhtin recognizes the process of the actor’s transformation into a character within her consciousness and simultaneously taking place “before a mirror, before a director” (77), so the actor would see herself as the character. “The actor ‘reincarnates’ himself in the hero, then all constituents of forming the hero outside become transgredient to the actor’s consciousness and experiencing as the hero. The form of the body as shaped from outside, its movements and positions,—all these constituents will have artistic validity only for the consciousness of a contemplator” (77). In Soleymanlou’s work, the author-autobiographer-narrator also assumes the role of another. He sacrifices his ego and tries to cope with the past in the light of the present; he does this by building his new relationships with the character, Mani, a representation of himself. This process is revealed in the trilogy’s increasingly self-reflective stage directions, in which Soleymanlou acknowledges the gap between the I of the author and the I of the character, and reveals the process of making the show.

On the Narrator/Character Dichotomy of the Immigrant Solo Performance

23 Immigration as a childhood trauma affects the artist’s experience of integration in the new land and subsequently the themes and the form of the work she produces. A child-immigrant “loses the very definition of ‘home’” because “the act of immigration deconstruct[s] it”; for this child, the tragedy of the lost home is immediate. Stronger than any adult, an immigrant child feels the “urge to have [home] again” (Rokosz-Piejko 179). However, this immigrant child’s quest for home, unlike that of the Prodigal Son, remains suspended: this child is destined to be in a state of constant arrival, conditioning through this gesture the act of deferral and the state of difference. The journey does not always unfold in the real space and time of the home country: it often remains the immigrant child’s fantasy. These fantasies take the forms of a secondary witness (Levine 4–6), the immigrant children’s creative narratives, which shape the imagined geography, culture, and history of immigration as imagined community or imagined nation. Trois reveals this phenomenon. As Soleymanlou explains, during his childhood neither his father, a businessman, nor his mother, a painter, talked to their children about their country: “Our parents explained nothing to us. I left Iran when I was two or three years old, but I was going back there at least two times a year. It was a firstclass immigration, not like fleeing in trucks with camels. Much later, my parents explained to me that they had to flee because of the Revolution that was followed by the war against Iraq (1980-1988) but without much details” (qtd. in Trouillard). Part Two “Ils et Elles” of Un, for example, presents the author’s attempt to reconstruct the image of an unfamiliar (to him) Iran and connect with it emotionally. It contains Mani’s account of a young Iranian man— Il/He—of his age, who grew up in the instability of the 1980 and 1990s Iran. Il dares to participate in the 2009 presidential elections but becomes disillusioned as soon as he realizes that his personal pursuit has been nullified by the elections’ contested results. This realization leaves the narrator, Mani, devastated, and the story takes on a conditional format. The narrative makes a detour to 1987, to a close-up on Mani’s childhood experience, when once during his summer visit to Iran a bomb hit his grandfather’s house, and the child was quickly returned to the safety of his home in Paris. This temporal digression is followed by a flashforward to Iran of June 2009. It brushes over the murder of a young girl, Neda Agha-Soltan, who participated in the political protests against the newly elected president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The journey now not only collapses the temporal frames of Iran’s past and present, but also disrupts the performative continuum of Mani’s speech act, as well as the fictional and actual memories that make it. This multilayered account of the times and stories creates the offstage heteroglossia evoked in Mani’s onstage utterance. The character and subsequently the audience discover that for Mani, an immigrant artist who grew up in his adopted country, the country of his cultural and linguistic origin is only an imaginary construct. This tension between the artist’s desire to belong to this culture and the geographical, temporal, and emotional distance that confounds this desire is irresolvable. The play Un thus becomes an account of the ethical difficulties the artist Mani Soleymanlou encounters when he tries to talk about Iran, to live through the processes of homecoming. As he explains, the 2009 events in Iran, the images of violence in the streets of Tehran “made me realize that [. . .] I am supposed to be there too. But would I have courage to be out on the streets? I went to a demonstration in Montreal and after half an hour, I did not feel it to be my place. People began to sing Iranian songs that I did not know. I thought, ‘Oh my god, even here among the Iranian Canadian diaspora, I do not feel I am in the right place’” (qtd. in Trouillard).

24 The artist’s response to this experience is his solo performance: Un presents Mani’s stages of homecoming from the character’s immersion in the literature and history of Iran to remembering his travels back home to meet the family. It also allows the artist Soleymanlou to comment on his own and his audience’s superficial knowledge of Iran, often limited to “la bouffe Iranianne”—its spices, fruits, and teas (Trois 40). At the same time, as he explains, after four years of touring worldwide (from Yukon to Great Britain) and performing Un now in English too, the performer Soleymanlou realizes that the character Mani and the country Iran are only the pretext for him and his audiences to think about something more profound, something that concerns people around the world in the times of mobile identities (Personal interview).

25 Un insists on maintaining the gap between the author Mani and the protagonist Mani, so it is curious how the pronoun Je/I gradually disappears from the play, to give space to “the character of this story” (Trois 22). Here, the author, the narrator, the protagonist, and the performer become the mirroring images of each other, the four of them making up the figure of Soleymanlou—an immigrant theatre artist. The play’s closing monologue presents the quintessence of this logic: spoken in French, English, and Farsi, it points at the immigrant subject’s inability to determine his identity. Mani’s choice to return to his multiple linguistic roots serves as the ultimate definition of the artist’s self and of the place he belongs to. Soleymanlou does not see himself as a product of a single cultural make-up but rather as the product of cultural heteroglossia and linguistic simultaneity. He insists that, “before others tell me or give me permission to be one thing, I must know it for myself. This task is much more complex than just to know the country where you come from; the identity is forged 1000 ways, and one must discover it for oneself” (qtd. in Trouillard). Thus, it is the therapeutic function of immigrants’ art that informs its authorship and leads to the self-reflexivity of the form, something that makes the process of narration visible.

26 Soleymanlou’s trilogy exemplifies the immigrant children’s need for linguistic, cultural, political, and generational adjustments, when they simultaneously seek family narratives as the discourse of their national and cultural completeness, and strive to participate in shaping the discourse of their adopted land. Exposed to the existential in-betweenness, these artists experience the nostalgia of return, whereas the artistic discourse they produce balances between the authenticity of testimony and its performative mediation. Such narrative is bound to appear stylized, fragmented, and narcissistic (Hutcheon 6). Paradoxically, it can provide an immigrant child with an opportunity to come closer to the language, culture, and history of her native country. In such a narrative, the characters are never explicitly autobiographical, nor are the events and the places evoked on stage ever fully accurate to the historical facts or the geography. Everybody and everything in the theatre of immigrant children takes on the quality of a fiction. The fictional “else-where” and “back-home” that these artists conceive serve as examples of imagined exilic communities, the signifier of the authors’ personalized exilic nation (Meerzon).11

On the “Addressable You” of Immigrant Solo Performances

27 To conclude, I would like to return to the premise of the article, which stipulates that in theatre the ontological separation of the actual and constructed selves, the central feature of any solo performance, functions as Bakhtinian author/character dialogicity. In Trois we see the separation of narrative voices as 1) the voice of the author/narrator/protagonist, 2) the voices of other characters, and 3) the voice of the performer, whose identity is often collapsed with that of an author/narrator/protagonist. This dramaturgy suggests an increasing tendency for stratification in Soleymanlou’s stage-presence. Here, the identity of the performer is collapsed with the identity of the character, the process producing an effect of singularity, “achieved by blending the actual and fictional so that they become virtually indistinguishable” (“Portrait” 50). In Trois, this effect is attained through several dramatic devices. First, the play insists on multiple layers of Self that make an immigrant solo performance: the author-autobiographer-narrator (historical Mani) assumes the role of another (fictional Mani). The historical Mani, the author, tries to cope with his past in the light of the present, doing this by building new relationships with the character, a representation of himself, in a manner reminiscent to Bakhtin’s dialectics of the author/hero relationships. On stage, we see the author Soleymanlou “occupying an intently maintained position outside the hero,” Mani, observing the image by “supplying all those moments which are inaccessible to the hero himself from within himself” (“Author” 14). The play comments on the separation and the distance between the speaker and the author. The power of storytelling as a form of autobiography is in this confessional mode, so the I of the author appears paradoxically separate and indistinguishable from the I of the character. The solo speech is addressed to the speaker’s Self in several temporal dimensions. They are the past self, a self that is still developing, the present and the future selves, and the projected or ideal self of the character. The narrator Mani, reflecting on the process of writing his monologue, and the character Mani, expressing his growing frustration with the cultural clichés he is subjected to both in Montreal and Iran, force the author Soleymanlou to rethink the structure of a solo piece as the mechanism of Brechtian alienation. This device allows the performer Soleymanlou to confront the storyteller’s task of facing the audience, when a spectator functions as the speaker’s universal source of appeal, an absent, disappeared, or imaginary Other, in front of whom an immigrant recounts her life journey. As Soleymanlou tells us:

28 Performing the trilogy, Soleymanlou becomes a hyper-historian (Rokem) of his own creative process and turns the performative encounter between the stage and the audience into homecoming. In the end all theatre artists (immigrants or not) identify theatre as “home”, other theatre makers as “nation”, their onstage partners as “family”, and their onstage work as “roots”. By addressing its new audiences and taking their own semantic context into consideration, the solo performer creates a dynamic exchange between the stage and the auditorium, so the autobiographical narration concludes with “a subtle act of holding mirrors for self and other, [. . .] the act of ‘holding mirrors’ as a means of critical engagement with autobiographical inquiry is what imbues the process with a sense of accountability that translates into a transformative experience” (Attarian 187). The use of the autobiographical material organized into monologic speech becomes the device of truth. The act of public speaking presupposes an actor’s solitary presence in front of the audience; so “the dual notion of detachment and involvement becomes an important dramatic and existential category in this framework. The self analysis provides the detaching principle, while the awareness of the multiple layers of subjectivities in constant flux is the underlying involvement” (185). This recognition of postmodern subjectivity as an expression of existential loneliness is never better rehearsed and staged in today’s theatre than in the multicultural and multilingual audience facing the immigrant artist. As Soleymanlou’s show unfolds, the languages that claim him as “theirs” crop into it. The more confused the character becomes, the more heteroglossic his utterance grows. The audience witnesses Mani descending into linguistic chaos, the environment in which the subject of globalization is created and the new catharsis as compassion is to be experienced. The second and third parts of the trilogy are made to expand on this experience. In Deux Emmanuel Schwartz brings the multitude of today’s Montreal voices on stage, so by ostension the dialogue between Mani and Manu grows multivocal. Trois features forty-three, similar to Soleymanlou’s, accented and diversified voices; and it finishes with Marco Collin’s monologue as an attempt of bringing this onstage heteroglossia into reconciliation, an effort to hold this linguistic mirror to contemporary Quebec.

29 However, most of the trilogy’s spectators cannot share such linguistic or cultural experience. It is unrealistic to expect that the Quebecois or even international theatre circuits on which this show plays would feature trilingual or multilingual audiences of Iranian or other descents. Still Soleymanlou manages to turn the issue back to his spectators, many of whom live through the experience of continuously shattered and reassembled identities. Like the performer, these spectators find themselves marching on the roads of utopia, searching for places and communities to belong. The time-place of a theatre show, the experience of storytelling as such, turns into a utopian community (Dolan). As long as the show goes on, an immigrant artist can control the heteroglossia of voices that make her Self; as soon as it stops, the anxiety, the chaos, and the self-doubt of Deleuzian difference-in-itself (41) take over.

30 The performativity of this position finds its reflection in one more framing device: Trois stages the theatrical conditions of storytelling. Every part of the trilogy opens with several false starts with the actor missing cues and addressing his stage manager, a fictional “standin” for the actual spectators. The rows of identical black chairs that make up Trois’s set visually reinforce the linguistic concept of heteroglossia. In its rich semiotic symbiosis, the empty chairs suggest multiple meanings. One of them—referencing absentia—evokes silence and points at many other immigrant off-stage subjects, whose (in)visible presence makes the population of today’s Quebec in general. Indexical signs, the chairs also stand for the absent voices of Iran’s historical past and its present; they refer to Mani’s childhood and current encounters. By ostension, in Deux, the chairs signify the figures from Schwartz’s memory and imagination; and in Trois, they point at the multitude of histories and geographies that make up the heteroglossia of the forty-three immigrant voices. The same empty chairs serve Soleymanlou as an invitation to his audiences to join him on stage: so in the mirror image of the society he evokes on stage, the Bakhtinian dialectics of the author /character relationships is suggested. The voices in absentia—the empty chairs on stage—become the trilogy’s central image and the metaphor for heteroglossia. This way, in its aural and visual semiosis, Soleymanlou’s trilogy stages the logic of alterity and the logic of the immigrant autobiographical solo performance. In her artistic endeavours, an immigrant artist is bound to become autobiographical and to search for wider audiences. This quest for universalities remains utopian but suggests a model of multiple modernities: a process of reconstruction or filling the gaps of personal memory and experience. Soleymanlou’s trilogy unfolds almost in mythical dimensions with the character’s recognition of his in-between-ness as privilege and punishment. The character Mani, alone in Part One, together with Manu in Part Two, and collectively with other immigrant performers in Part Three, willingly takes on the Sisyphean task of reconciling his divided Self and cultural experience, as well as social expectations and artistic expression, whereas the audience participates in this dancing madness by dancing themselves (Barba).

31 The audience’s sympathy, however, is less prompted by the artist’s political project. We all know: the personal is political. It is rather instigated by our own experience of disembodied and questioned subjectivities, by the emotional stupor we bear facing the paradox of today’s world stretched between the heteroglossia of transnational citizenships, mobile identities, and the monoglossia of rising nationalisms, the danger to which Trois is a witness too. Thus, by telling a story of difference—the difference between what Soleymanlou intended to make and what he created; the difference between what Mani thought he knew about himself and what he discovered in the process of making this show; and the difference between his childhood impressions of Iran and the historical Iran of the 1979 and 2009 revolutions—, Trois helps Soleymanlou, and after him his spectators, to discover that the differences create unities. They are the unity of a theatrical performance (its spatial and temporal continuum); the unity of a split identity (stretched between the artist’s memory of his country of origin and his life experience in a new home); and the unity of a performative encounter, when the artist and the audience come together to laugh, to be amused and amazed, and to feel compassion and empathy.