Articles

Carmen Aguirre’s The Refugee Hotel and the Space Between Limited and Unlimited Hospitality

Rabillard considers Carmen Aguirre’s The Refugee Hotel in the light of Jacques Derrida’s “On Cosmopolitanism” and his Of Hospitality, focusing on Aguirre’s use of fictional place and presentational space. As Derrida teases out contradictions in the concept and practice of hospitality and the limitations of attempts to respond to the limitless demands of cosmopolitanism, understood as the right of anyone to dwell anywhere in the world, so Aguirre stages the limitations of the refuge Chileans find when they flee to Canada in the wake of Pinochet’s takeover. Much of the play’s power lies in its evocation of trauma and its presentation of the refugees’ stories of suffering, stories based upon the experiences of Aguirre, her family, and opponents of the Pinochet regime with whom she worked. But an important aspect of the play’s political significance emerges via comparison with Derrida. For The Refugee Hotel challenges the spectator to recognize both the difficulty and the necessity of welcoming refuge seekers without imposing boundaries and definitions or requiring them to assimilate. The limitations of the refuge offered are figured in the play’s single set: a shabby hotel in Vancouver; evoked via representation of linguistic barriers; and dramatized in the parochialism of the welcoming social worker, and in the pressure to assimilate experienced by the refugee children. The play intervenes in Canadian political discourse, dispelling myths of national generosity, and represents hospitality based upon the mutual responsiveness of guest and host. Rabillard argues in conclusion that the political challenge of The Refugee Hotel, its requirement that we apprehend the full demand of true borderless hospitality, extends to the cultural space of Canadian theatre, where immigrant authors such as Aguirre must find a place.

Rabillard propose dans cet article une lecture de la pièce The Refugee Hotel de Carmen Aguirre à la lumière des textes de Derrida « On Cosmopolitanism » (Cosmopolites de tous les pays, encore un effort !) et Of Hospitality ( De l’hospitalité ), s’attardant plus particulièrement à l’emploi par Aguirre de lieux fictifs et d’espaces de présentation. Derrida faisait ressortir les contradictions du concept et des usages de l’hospitalité et les limites des tentatives de répondre aux exigences illimitées du cosmopolitisme, compris comme étant le droit de quiconque de vivre n’importe où dans le monde. À l’instar de ce dernier, Aguirre met en scène les limites du refuge qu’ont trouvé les Chiliens s’étant enfui au Canada au lendemain du coup de Pinochet. La puissance de la pièce réside dans sa façon d’évoquer le traumatisme et de présenter les récits de souffrance des réfugiés, récits inspirés d’expériences vécues par Aguirre, sa famille, et des opposants au régime de Pinochet avec lesquels elle a travaillé. La comparaison avec les écrits de Derrida fait ressortir un aspect important de la portée politique de la pièce. The Refugee Hotel force le spectateur à reconnaître la difficulté et la nécessité d’accueillir les demandeurs d’asile sans leur imposer de frontières ou de définitions ni exiger d’eux qu’ils s’assimilent. Les limites du refuge offert sont évoquées par l’unique décor de la pièce—un hôtel miteux à Vancouver—, par la représentation des barrières linguistiques, par la théâtralisation de l’esprit borné du travailleur social et par la pression à s’assimiler que vivent les enfants réfugiés. La pièce fait une brèche dans le discours politique canadien en réfutant les mythes sur la générosité des Canadiens et offre une représentation de l’hospitalité fondée sur la réceptivité réciproque de l’invité et de l’hôte. Rabillard soutient que le défi politique posé par The Refugee Hotel, qui demande que nous saisissions pleinement ce qu’exige la véritable hospitalité sans frontières, s’étend à l’espace culturel du théâtre canadien, au sein duquel des auteurs immigrés comme Aguirre doivent se tailler une place.

1 This essay examines Carmen Aguirre’s The Refugee Hotel (premiere Alameda Theatre Company 2009, publication 2010) in the light of Jacques Derrida’s reflections on cosmopolitanism and hospitality. Aguirre’s play is loosely based on the experience of her family who came to Canada as political refugees when the Pinochet regime seized control in Chile. As such, it is centrally concerned with space and place: with refugees from one nation relocating in another, and with the political, ethical, and psychological tensions inherent in this process for asylum-seekers and those providing refuge. In a single-set space, The Refugee Hotel presents the arrival of eight Chilean political refugees at a Vancouver hotel in 1974, a scant five months after the coup overthrowing Allende, and their initial attempts to find a place in Canadian society. Like Aguirre’s parents, the central figures, Flaca and Fat Jorge, arrive with two children: a daughter, who is close in age to Aguirre when she came to Canada and another child, in Aguirre’s case a younger sister, but in the play an older brother.1

2 I use both “space” and “place” in describing my focus because I draw on several studies from the “spatial turn” of the past decades, including Una Chaudhuri’s Staging Place: The Geography of Modern Drama and Gay McAuley’s Space in Performance: Making Meaning in the Theatre. Following Chaudhuri, I use the language of geography to read place within the dramatic text as I examine Aguirre’s dramatization of struggles concerning exile, refuge, identity, and assimilation. In McAuley’s terms, I focus on the play’s thematic space principally via its presentational space (that is, the physical use made of the stage space in a performance) and fictional place (the place or places represented or evoked onstage and off) including the offstage spaces of the city of Vancouver, and the nation-states of Chile and Canada (29). I read both fictional and presentational spaces as these are implied by the play text but wherever possible my conclusions are also based upon the Alameda staging at Toronto’s Theatre Passe Muraille. This production, generously documented in a ten-part video, “Making The Refugee Hotel,” posted on a blog created by the Alameda Theatre Company, was directed by the playwright herself. Under Aguirre’s guidance, the production eloquently evoked the play’s symbolism of space on stage.

3 Expanding McAuley’s “unlocalized fictional offstage” (31) to include realms of spatial discourse of the kind mapped by Chaudhuri (for example in her discussion of the figuration of America as heterotopic, 5), I situate Aguirre’s Vancouver refugee hotel within the virtual spaces of international debates about cosmopolitics and asylum (articulated with radical clarity by Derrida) and Canadian political discourse of hotel and hospitality, as analyzed by Carrie Dawson in her “Refugee Hotels: The Discourse of Hospitality and the Rise of Immigration Detention in Canada.” McAuley’s fictional “unlocalized off” includes those places that are part of the dramatic geography of the action but which are not placed in relation to the onstage, the contiguous offstage, or the audience space, for example, Moscow in Three Sisters (31). In Aguirre’s play “Canada” is an unlocalized offstage place because although the fictional hotel is located within Canada, the nation as a geopolitical entity is understood to extend far offstage beyond the place of the hotel and its contiguous offstage environs. In fact, the Canadian character of the hotel is unstable; some of Aguirre’s thematically interesting play with place occurs as the hotel’s status as a location within Canada is made more or less prominent at different moments in the drama.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

4 My central claim is that Aguirre, through dramatic action bound up with the fictive setting and physical set of her refugee hotel, presents conflicts concerning location and belonging whose full significance should be understood as part of larger political and philosophical conversations about the meaning of hospitality and the cosmopolitan ideal of the absolute right of the individual to go anywhere on earth. The problematics dramatized in and through Aguirre’s hotel space (for example, the tension between assimilation seen as adaptation to environment, or as renunciation of identity) affect the inner struggles of the characters in the hotel. These problematics play out topographically as various characters affect the hotel’s spaces, or are affected by the space; this creates a palimpsest of fictional places in the presentational space as abrupt shifts in temporal setting and tone alter the meanings of the hotel and layer past (Chilean) places and experiences upon the present (Canadian) setting. Characters evoking the offstage Canadian government or bearing trauma inflicted by the Pinochet regime imply the political dimension of Aguirre’s drama, as I will show; but in what sense does her play invite philosophical reflection? The tensions and contradictions within concepts of hospitality and cosmopolitanism that Derrida presents analytically, I argue, Aguirre allows her audiences to experience dramatically, to apprehend emotionally as well as intellectually. Audiences may be touched by the effects of such contradictions and tensions if they wonder, for example, how disparate individuals will find places for themselves in a new country; how their past tragedies and present comedies can coexist; and whether the inadequacies of the present asylum accord with the politicized image of an hospitable Canada (Dawson 827). In short Aguirre, like Derrida, opens for exploration a space between the contradictory imperatives of unconditional and conditional hospitality.

Cosmopolitics

5 “Cosmopolitanism” is a much-debated term. The concept has been criticized because it presumes a false universality based in Enlightenment thought, which excluded peoples not considered world citizens, and has been violently imposed upon others. More recently xenophobia, terrorism, and populist nationalisms along with financial crises have made the ideal of belonging to a harmonious global community of cosmopolitan citizens seem naive or futile (see Braidotti, Blaagaard, and Hanafin, “Introduction”). Helen Gilbert and Jacqueline Lo point out the dangers of “thin” cosmopolitanism that delights in cultural diversity without duly considering “the hierarchies of power subtending cross-cultural engagement or the economic and material conditions that enable it” (9). Both of the studies just mentioned are part of an ongoing attempt not simply to critique Kantian cosmopolitanism as an imperative to global commerce but to re-imagine cosmopolitan politics, sometimes in terms of plural loyalties; alternatives to nationalism; or via nations in cosmopolitan formations (7-8). Derrida’s reflections, as he teases out contradictions inherent in the concept and manifest in its historical variations, avoid both universalism and futile idealism. In his recent discussion of the role of cities of asylum, he considers a cosmopolitan space other than the nation state, although not necessarily in opposition to it and explores a cosmopolitics of refuge.

6 In 1996, Derrida was invited to address the International Parliament of Writers in Strasbourg “on the subject of cosmopolitan rights for asylum-seekers, refugees, and immigrants” (Critchley and Kearney viii). The IPW had been founded in 1993 in response to threats against writers, including the murder of Tahar Djaout and the fatwa against Salman Rushdie (Kelly 423). They now proposed that participating cities, operating independently of one another and of their nation states, provide asylum to all writers seeking refuge from oppression. As the invitation to the philosopher indicates, however, the IPW recognized that wider principles of refuge, hospitality, and cosmopolitan rights must underpin their efforts to provide asylum for writers. In his address to the IPW, later published as “On Cosmopolitanism” (“Cosmopolites de tous les pays, encore un effort!” 1997; translation 2001), Derrida picks out “a concept that a country like France has been keen to adopt in fashioning its self-image of tolerance, openness, and hospitality” (Critchley and Kearney x). He does so in a year “particularly dark [. . .] for France’s reputation as a place of hospitality and refuge from oppression, with the clumsy and violent imposition of the Debret laws on immigrants and those without rights of residence” (x). In his address, Derrida locates “a double or contradictory imperative within the concept of cosmopolitanism: on the one hand, there is an unconditional hospitality which should offer the right of refuge to all immigrants and newcomers. But on the other hand, hospitality has to be conditional: there has to be some limitation on rights of residence” (xi). Derrida discloses tensions essential to Aguirre’s play in part because he addresses concepts inherited from classical tradition and the Enlightenment, sources which underpin both Canadian and French law and politics; and he probes these concepts in the context of a “dark” year that tested as it revealed national investment in a self-image of hospitality, a self-image that has a Canadian counterpart in the “seductive myths of Canadian benevolence and hospitality” (Dawson 841).

7 Derrida’s address bears upon the themes, dramatic conflicts, and theatrical presentation of Aguirre’s play in many ways. My initial contention, however, is that Derrida’s discussion of the “new cosmopolitics of the cities of refuge” (“On Cosmopolitanism” 4) illuminates an asylum politics of present compromise and future possibility2 implicit in the limitation of Aguirre’s single set and setting. Derrida’s city, like a hotel, is a relatively limited place within larger geopolitical spaces. Aguirre’s fictional location is further limited in a figurative sense by its indeterminate status. The refugee hotel holds a tenuous place in hierarchies of power and maps of belonging. It is an ad hoc shelter: no longer a competitive business attracting travellers; not quite an official government-run residence; not yet a permanent place for the refugees to call home. At the same time, insofar as it offers refuge, the setting has a tentative hopefulness: in the play, the Gonzalez family members who had been separated in Chile because of the parents’ imprisonment cuddle together on one bed as soon as they find themselves in their hotel room (The Refugee Hotel 25).3

8 In his analysis Derrida implies that a city, while lacking the power of a nation state, may perhaps evade some of a nation’s political commitment to controlling borders and thus offer asylum more readily: “We have undertaken to bring about the proclamation and institution of numerous and, above all, autonomous ‘cities of refuge’, each as independent from the other and from the state as possible, but, nevertheless, allied to each other according to forms of solidarity yet to be invented” (“On Cosmopolitanism” 4). He makes clear, however, that the new cosmopolitics built upon the city has yet to be achieved, and that the task facing these cities of refuge is immense: “to reorient the politics of the state” and to “transform and reform the modalities of membership by which the city belongs to the state” (4). The nation state in its current condition polices its borders, offering inadequate refuge and then only to some; the more generous and flexible asylum provided by cities in alliance remains chiefly in the future, in the context of re-imagined state sovereignty. In keeping with Jacques Rancière’s contention that Derrida’s “democracy to come” is not a prediction of the future (274-88), I argue then that the futurity associated with Derrida’s articulation of hospitality between the absolute Law and the limiting laws should be understood not as a prediction of what will be inevitably, but as an exhortation to bring this about in actuality, in history; thus the original subtitle of his “On Cosmopolitanism” urges “encore un effort!”

9 Aguirre’s presentation of her play on a single stage set, and for the most part (aside from trauma flashbacks and brief references to offstage errands) in one fictional location, the interior of a low-budget Vancouver hotel, chimes with the limited spatial expression (suggestive of limited political power), and the future orientation, of Derrida’s hopeful vision of asylum cities. The sense of change to come, of transience, associated with the hotel space arises from its usual social function as a temporary abode for travellers and from its specific use in the fictional action as a way-station for new arrivals who have been permitted into the country but not yet assigned housing and located in a community by the Canadian authorities. Within the hotel the various Chilean characters find refuge, but the concentration of the action in this single set makes what lies outside the hotel, in the implied offstage world of Canadian society, into a space of uncertainty. If refuge for the moment lies within the hotel for the Chileans, what lies without for them?

10 The most striking initial venture into the (contiguous) offstage space occurs when Manuel attempts suicide by leaping from an upper storey and is seen by a number of the others falling past a hotel bedroom window “in slow motion, free-falling” (The Refugee Hotel 76). Although he survives the fall by chance because he lands in a dumpster filled with pink insulation batting, this would-be suicidal exit associates the offstage fictional space with danger and despair. Limited access to any larger space of refuge is suggested as well by the night scene in which Manuelita and Joselito, hoping to escape from their unhappy parents, can’t manage to telephone from the hotel to the offstage Social Worker (94). Eventually, several of the characters make successful forays into the fictional offstage space of Vancouver’s streets and shops: Juan finds work wearing a chicken costume (107); Cristina, a.k.a. Cakehead, buys cake-mix at the supermarket (113). In the end, the Social Worker finds the refugees jobs, rental housing, and schools. But the uncertainty associated with the offstage, i.e., with Canadian society, is not dispelled by this apparently tidy dramatic resolution. As in Derrida’s speculation about a new cosmopolitics, the promise of refuge is to be fulfilled only in the future when the refugees perhaps might be truly at home. Calling for an ongoing effort, Derrida asks: How can the hosts and guests of cities of refuge “be helped to recreate, through work and creative activity, a living and durable network in new places and [. . .] in a new language?” (“On Cosmopolitanism” 12).

11 Aguirre indicates the limitations of the present hospitality and the precariousness of refuge in Canada still to be fully realized in several ways. Some of the characters rearrange the Social Worker’s housing assignments to accommodate newly-formed couples (The Refugee Hotel 123); some, like Juan and Isabel, a.k.a. Calladita, find employment on their own (106, 108). These small actions (chiefly engagements with the fictional offstage space, except in the case of Calladita who gains work within the hotel itself) indicate the insufficiency of the hospitality arrangements made for the various refugees.

12 At the same time, by demonstrating the ability of refugees to make a place for themselves in Vancouver, these actions evade what Julie Salverson in her discussion of community theatre work with refugees calls the “aesthetic of injury.” The tenuousness of the refuge the characters find, and the uncertainty of their making a home in Canadian society, is signaled as well by the epilogue in which the audience learns what happens after the refugees leave the hotel and move into the offstage world of “Canada”: some thrive, one dies as a result of a heart weakened by torture, one drinks himself to death. A theatre reviewer called the epilogue a “Where-AreThey-Now” dramatic cliché (Nestruck), but I argue that this dramatic convention is used with good reason. It marks the refuge of the hotel as limited in time as well as space: offering a temporary respite, in a circumscribed space, before the characters take up their real task of finding a way to belong, perhaps in more than one place, possibly with multiple allegiances both to Chile and to Canada in an emerging cosmopolitics.

13 In one respect, Aguirre’s refugee hotel considered as fictional space offers limited asylum simply because it is provisional housing: for practical reasons, it is barely adequate shelter and provides none of the permanency and secure belonging of a home. However, if the limitations of the presentational and fictive space are read in terms of Derrida’s meditation on the limits everywhere placed upon cosmopolitanism conceived in terms of the Law requiring unconditional hospitality to all comers (“On Cosmopolitanism” 19), then the limitations of the single set and the unvarying hotel setting can be understood as spatial expressions of the characters’ experience of a limited legal right to reside in a nation state, an experience of hospitality granted only in certain legally specified circumstances (17). To different degrees, several of the refugees demonstrate an awareness that they reside in the refugee hotel because of arrangements made between the governments of Chile and Canada, arrangements outside their control, and not because of any cosmopolitan right to dwell in Canada. The confusion several characters express about the process that brought them to the hotel underlines their lack of agency: Cristina is surprised to find herself in Vancouver because she “thought they were sending me to Toronto” (The Refugee Hotel 35); Flaca recalls “I was headed for the firing squad with nine others and then all of a sudden the blindfold gets taken off and I’m loaded into a Canadian embassy car, driven for eighteen hours straight to Santiago airport, taken to a plane and handcuffed” (61). Although no further mention is made of those left to face the firing squad, this brief speech not only recalls Flaca’s shock at her last-minute reprieve, but in understated fashion demonstrates the limits of asylum that is given to one in ten.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

14 Perhaps the clearest evidence of the legally limited and conditional asylum figured in the limited presentational and fictional space of the hotel comes with the arrival of Juan, who has stowed away on a Swedish freighter and claims to have escaped from a Chilean prison. Unlike the others who seem to have been transported from Chile already under the aegis of the Canadian government (the Social Worker comments, for example, that Manuel has “come directly from a concentration camp on Dawson Island, near Antarctica” [The Refugee Hotel 55]). Juan has not been officially designated a refugee and thus he is in danger of deportation. His refugee status is quickly granted (offstage), but Aguirre indicates clearly that those who flee to Canada on their own initiative are at the mercy of the authorities. The “hippy” Bill, in what we understand to be ungrammatical Spanish, vows to stage a sit-in protest if the decision goes the wrong way: “Me make sure you not fucking deportation. I sit on the Immigration Ministry with me friends” (67).

15 If the limitation of the presentational and fictional space deserves to be read in terms of cosmopolitics, so too does movement within these spaces. Linking The Refugee Hotel to Derrida’s reflections on the state’s legal limitation of rights to visit or reside (“On Cosmopolitanism” 16-23) allows me to read a critique of the inhospitable exigencies of state border control in Aguirre’s scripting of her characters’ movements and their figurative language of fences and entrapment. She has elsewhere signaled her desire for a more humane approach to the control of borders; she contributed an excerpt from her play Chile Con Carne to an anthology, published under the auspices of the Institute for Anarchist Studies, titled Undoing Border Imperialism. The editor of the volume, Harsha Walia, introduces its purpose as follows: “The book is about undoing borders—undoing the physical borders that enforce a global system of apartheid, and undoing the conceptual borders that keep us separated from one another” (2). In a 2013 interview that links Chile Con Carne to The Refugee Hotel, and connects both plays to her sympathy with movements challenging state and corporate control, Aguirre comments: “Themes that are present in all of the plays—Refugee Hotel, Blue Box, Chile Con Carne—continue to be very timely, and not only in Chile but also in Canada with the Idle No More movement, with the Occupy movement, with the student movement in Quebec” (“Playwright Carmen Aguirre”). In Chile Con Carne tacit protest against “apartheid” (Walia 2) created by national borders is implied in the loneliness of the eight-year-old protagonist, a Chilean refugee at school in Vancouver; and the inimical control of spaces by corporate forces is expressed in the girl’s struggle to rescue a tree from destruction. In The Refugee Hotel, distrust of state and corporate powers is voiced in varied ways by different characters, in keeping with their individual experiences, but always in such fashion as to disclose their painful awareness of the limits on their movements and choices created by such powers. Cristina experienced economic apartheid in Chile and accuses Fat Jorge, Chilean bank employee, of not recognizing this division in the past:

Fat Jorge himself critiques capitalism emphatically: “Once the whole world is socialist, we will move towards communism and then towards anarchism” (46). Although his insistence is shown to be the product of his regret for having lived an apolitical “cushy life in downtown Santiago” (74) and most markedly from guilt at what he sees as his betrayal of the leftist cause by breaking under torture and by fleeing into exile, his extreme rhetoric nonetheless becomes part of the play’s thematic emphasis on restricted mobility. He is now “stuck” in the hotel, in Canada, due to the conditions of asylum agreed by the Chilean and Canadian governments:

16 The opening scene of the play uses movement more subtly but no less effectively to establish restriction as a key motif. In the first scene of The Refugee Hotel, the dialogue consists of a series of verbal miscommunications as the English- and French-speaking Social Worker invites the Spanish-only Gonzalez family to settle into their hotel, and the parents, Flaca and Fat Jorge, attempt to explain that they have no money for a room. The stage movement throughout this scene enacts a struggle to get the family upstairs from lobby to bedroom level, with the Social Worker urging the family with words and gestures to move upward and the parents staying where they are in the lobby, uncertain that it is appropriate for them to proceed to another space, to move from a place available to the general public to the (economically) controlled space of the room. Although we don’t learn this explicitly from the play, Chileans brought to Canada in the 1970s were not only controlled by the Canadian government’s legal determination of their refugee status, they were also barred from returning to Chile by the Pinochet regime.4 Reflecting the border sovereignty so affecting their lives, the extreme caution of Flaca and Fat Jorge regarding any unauthorized movement from space to space shows a telling anxiety, a caution made notable by the apparent openness of the wall-free presentation space in the Alameda Theatre production (“Making” episode 8).5.

17 Aguirre’s stage directions indicate that the presentation space is designed to give simultaneous glimpses of different lives and thus allow the playwright to showcase the individuality, and the varied experiences, of the refugees assembled in her play despite the uniform legal definition of their identity and their right to a place in the hotel:

Trevor Schwellnus, set designer for the Alameda production, created a three-level space: a lobby stretching across the width of the stage, with a reception area stage right, a lounge area on the left. A central ladder-like stairway led upward from the back of this main playing space giving access to the “hotel rooms” located on a second level upstage of the reception area and approximately five to six feet higher than the lobby, and on a third level, a few feet higher still, upstage from the lounge area of the lobby. The hotel space as a whole was not enclosed, and areas within the hotel were differentiated by the varied levels and by a few furnishings indicative of function: the reception desk, the lobby sofa in 1970s orange (“Making” episode 8). One result of the open, schematic design of the playing space was that it allowed the fictional “public” and “private” areas to be seen at the same time; when a doctor examines Manuel’s naked body to determine the extent of the injuries he suffered due to torture, we see that medical examination taking place in Manuel’s room at the same time as we see the Receptionist and Social Worker in the lobby, and all of the other refugees playing cards in Flaca and Fat Jorge’s room (The Refugee Hotel 55). Thus Aguirre’s particular staging of a hotel, with the common space of the lobby and the individual spaces of the refugees’ rooms on their different levels constantly visible, reminds the spectator of the many kinds of adjustments the refugees must make in their personal lives and bodies as well as in their public engagement with Canadian society.6 When Fat Jorge asks his TV-watching children “Where are the women?”, his daughter Manuelita answers matter-of-factly, “Crying in their rooms,” to which Jorge replies “Oh for fuck’s sake. Again?” (44). The weeping women Cristina and Isabel (by this point in the play nicknamed Calladita), like all of the characters, remain on stage once they enter the hotel presentation space. In this passage, the dialogue draws attention to their presence and invites the audience to consider what unknown particular sorrows might lie behind Calladita’s public silence and Cristina’s fierce articulacy.

18 The simultaneously visible spaces also highlight, via juxtaposition, the crucial differences in the characters’ experiences and reactions: these range from the Gonzalez children (Manuelita and Joselito) who remain deeply saddened and confused by their parents’ past imprisonment, to their heroic mother Flaca who kept her husband Fat Jorge ignorant of her work in the resistance, to the “martyr” Manuel (61) whose torture has rendered him almost a skeleton (55). In tension with these differences is the common experience of their flight from Chile, and the fact that all (eventually) are determined by the Canadian government to conform to the same legal category, refugee, and fall under the rule of the same laws and policies. The minimally differentiated anonymous spaces7—that is, the hotel rooms assigned to the vividly differentiated characters—make a silent point about the legally delimited, restricted nature of refugee status.8

The Law of Hospitality and the Laws of Hospitality

19 Thus far I have dwelt on the ways in which the spaces of The Refugee Hotel invite reflection on limits and limitations: national borders, refugee status, political, legal, and economic circumscriptions of space and freedom of movement. But the drama also creates spaces where negotiation between the contradictory demands of absolute and pragmatic hospitality plays out; and its hotel space is progressively redefined in ways that suggest the possibility of a new ethics of hospitality based on receptiveness and responsiveness as envisioned by Derrida (Gilbert and Lo 204).

20 The contradictory demands associated with hospitality I refer to above are entwined with cosmopolitical issues concerning national sovereignty and global freedom of movement, but distinct in their concern with the roles of guest and host. In analyzing hospitality, as in his discussions of cosmopolitics, Derrida articulates a similar contradiction between concept and practice, between the concept of hospitality as unconditional and the practical limits historically placed on the kind and duration of the welcome offered to an outsider. Distinctively, however, his account emphasizes the deep tradition in which the ideal of an obligation to hospitality is rooted, far older than the Enlightenment notion of cosmopolitanism, and deems hospitality “culture itself and not simply one ethic among others” (“On Cosmopolitanism” 19). In effect, he urges us to seek “an historical space which takes place between the Law of an unconditional hospitality, offered a priori to every other, to all newcomers, whoever they may be, and the conditional laws of a right to hospitality” without which the unconditional Law of hospitality is merely an impossible dream (22). Derrida is particularly helpful in defining the pressures and tensions encountered in creating a hospitable “between” space. In Of Hospitality, he points out the tendency of the host offering conditional hospitality to define and even alter the identity of the other—that is, the danger of assimilation experienced as identity loss. The “other” is defined according to a legally recognized identity as “foreign”, and perhaps even required to understand the host and to “speak our language in all the senses of this term” (15). Further, Derrida defines the opposite challenge faced by the host who ventures unlimited hospitality: “I open up my home [. . .] to the absolute, unknown, anonymous other.” In an intriguing statement, he says also: “I let them arrive, and take place in the place that I offer them” (25). This locution suggests that the new arrivals, the guests, will perhaps exert power over the space into which they are welcomed (“take place”) and will be themselves unmodified, taking place (in the sense of occurring) in their unique personhood and cultural identities.

21 Aguirre’s drama explores the space between these contradictory imperatives, between absolute hospitality and the legal exercise of hospitality that limits or prohibits it. I propose that the difficult negotiation between absolute hospitality and hospitality that defines and controls the foreign is dramatized in the arc of action concerning the well-meaning social worker, Pat Kemelmen, an action counter-pointed by a poignant scene concerning Joselito’s desire for assimilation. In analyzing Kemelmen’s development, I suggest a parallel between Derrida’s analysis of true hospitality and his discussion of friendship. While for the most part in Rogues and Politics of Friendship Derrida deconstructs the figure of the brother in ethics, law, and politics—analyzing fraternal privilege and masculine authority bound up with concepts of nationhood and national citizenship—, he also reads Cicero and Blanchot where the friend is radically other, not a version of oneself (Cheah and Guerlac 9). This reflection on friendship that does not require fraternal likeness provides a useful analogue to hospitality that does not require the refugee to “speak our language, in all the senses of this term” (Of Hospitality 15).

22 An aside on language: Aguirre amusingly gives articulate English dialogue to her Spanishspeaking characters and assigns broken English to the Canadian speakers when they are trying to communicate in inadequate (or in the case of Kemelmen virtually non-existent) Spanish. This linguistic reversal accommodates the dominant language of the Toronto audience of the Alameda production, of course, but the aesthetic choice also puts the Canadian English-speaking characters at a comic disadvantage, making them slightly ridiculous.9 The implication is that Bill O’Neill and Pat Kemelmen need to improve their linguistic skills rather than the new arrivals. Absolute hospitality invites the guest to “come as you are.”

23 Pat Kemelmen allows us to see the limitations of hospitality based upon recognizing (or enforcing) likeness in the other. As a public employee in officially bilingual Canada, she speaks English and some French but no Spanish (aside from a few stray phrases, offered with dubious appropriateness). When we first meet Pat at the beginning of the play she speaks to the Chilean refugees in a mixture of English and French, perhaps hoping that she will stumble upon enough cognate words to communicate the gist of her meaning. This comically unsuccessful strategy suggests Pat’s unpreparedness for the otherness of the Chileans, her inability to escape the literal limits of her linguistic knowledge and perhaps of her cultural perspective as well. Here she introduces to the hotel the Gonzalez family on whom the play centers: “Ici! Uh ... le hotel! Tu stay ici until moi can place tu in a casa! Comprendez?” (The Refugee Hotel 22). Due to her lack of Spanish, she literally does not understand the family members, doesn’t succeed in reassuring them that they don’t need to pay for the hotel, and even at times seems puzzled that they don’t understand her: “Well, pourquoi we not go arriba to your room, now, comprendez?” (23). At the close of this scene she accounts for the family’s failure to respond readily not in terms of her lack of Spanish but their psychological state: “(to R ECEPTIONIST ) I think they’re in trauma” (25). As we discover in the following scene they have indeed suffered trauma due to their treatment by the Pinochet regime, but it isn’t trauma that prevents them from understanding Pat Kemelmen. In scene four of the first act, however, when Pat comments kindly on the arrival of two more Chileans who are welcomed by the Gonzalez family, she has begun to take into account the differences between herself and the refugees and when she attempts to compare their experiences to her own she does so with a degree of hesitation. “Je ne sais pas if this means anything to you, my family and moi arrived from Hungary, in 1956. [. . .] No. No. NOT Cristianos. Jews. Anyway. And it meant a lot to have fellow Jews waiting for us when we landed—” (37). Her arc of action, with its linguistic emphasis, reaches its full development when she relinquishes her attempts to make the Chileans understand her speech, and finds a way to express hospitality that goes beyond claims to likeness. In the play’s final scene, she brings toys for the children, Manuelita and Joselito, and explicitly asks Bill not to translate what she says to them (this time, in straightforward English rather than a mash-up of English, French, and Spanglish). Pat depends, instead, on the children’s emotional understanding of her tone and her actions: “They’re kids. They understand the heart of what I just said” (122). She has not undergone an unrealistic transformation—she still phrases her kindly feelings in terms of recognizing likeness to herself: “I really wanted to express to you two how much you remind me of myself when I was a small child and we first arrived in this country” (122). But remarkably, she asks to be included as an honorary member of their family: “Even though I don’t speak your language, I want to be considered your auntie too” (122). With these words, Pat puts herself in the vulnerable position of petitioner who could be misunderstood, or refused entry; she requests inclusion in their familial and cultural structure, thus implicitly accepting others as they are, rather than as like her. A few lines later, she once again claims to comprehend because of likeness but the assertion here sounds different because in fact she has understood correctly that four of the young Chilean refugees have paired romantically; and she has understood without being told. “Oh please, Bill. I’m not blind. Same thing happened with us Hungarians when we first arrived” (123).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

24 Punctuating this rather optimistic arc of action, in which we receive a hint that the refugees may take places in the host country without any requirement to conform to the host’s norms and categories of understanding (Of Hospitality 15), is a disturbing scene in which Joselito responds to the pressure to assimilate, to accept a kind of hospitality conditional upon becoming just like the hosts. In Act two, scene five, Joselito and Manuelita attempt to defect from their family. They sneak down to the lobby at night when the adults are asleep, with a suitcase and Pat Kemelmen’s business card, intending to call her for help. They have no coins for the pay phone, and they can’t manage to steal any from the reception desk, so they never make the call and thus what kind of help they would ask for remains unclear. I suggest that they want to assimilate (hence the call to Kemelmen, representative of the Canadian system rather than dissident Bill); but the longing to fit in—a longing that Aguirre evokes and mocks so well in Chile Con Carne and Something Fierce—is heightened by a fiercer desire to escape the exceptional stresses and suffering that have come with the parents’ participation in the Chilean resistance. As any immigrant child might want to be accepted, so much more does ten-year-old Joselito, refugee from a terrorist regime, want to ally himself with the normal, the law-abiding, the safe, even when that desire leads him to reject his own parents. Joselito tells his sister Manuelita, “If they [his parents] just minded their own business then none of this would have happened and we wouldn’t have been left alone with Grandma for all those months and now we wouldn’t be here with even more crazy people” (The Refugee Hotel 96). He refuses to hear about his mother’s rape; and he insists that “they had her handcuffed to the airplane seat ‘cause she’s bad’” (97). The scene ends unresolved, with the children staring ahead into the rainy night. Aguirre here shows the multi-generational effects of the trauma caused by the Pinochet regime; the scene also implies how crucial it is to offer hospitality as unconditionally as possible to those who could be so vulnerable to draconian pressures to assimilate by rejecting past allegiances and experiences.

25 For Aguirre’s refugee characters, finding a metaphorical space between the Law of Hospitality and the laws of hospitality—between intransigent otherness and draconian assimilation—means adapting each in her or his own way to a new place without losing identity, remembering a traumatic past without being overwhelmed or conforming to an “aesthetic of injury,” which reduces the refugee to merely a victim grateful for the help of the host country (Salverson). This is the burden of the refrain repeated by Adult Manuelita in the Prologue and Epilogue: “It takes courage to remember, it takes courage to forget, it takes a hero to do both” (The Refugee Hotel 18, 126). In spatial terms, this feat requires negotiation of the relationship between individual and environment, guest and hotel, refugee and host nation.

26 In many respects this negotiation is accomplished by the play as a whole, via its progressive transformation of the hotel as presentation space and fictional place. The actors affect the way in which the presentation space is read rather than simply taking their places against a given backdrop: for example, once introduced into the presentation space the actors remain on stage. When not actively engaged in a scene, actors in the presentation space thus form part of the hotel environment, a set comprised of bodies as well as built structures and props. In the fictive action of the play, the hotel is altered progressively by its guests, the characters affecting their fictional setting. The Receptionist, local controller of the hotel space, is initially associated with a very conservative notion of hotels as places upholding a traditional, Anglophilic version of Canadian culture; in the opening scene he pays scant attention to the Gonzalez family and the Social Worker (The Refugee Hotel 21- 23) because he is on the telephone arranging to take his mother to English-style tea at Victoria’s famed Empress Hotel. Aguirre subsequently shows him reacting to the changes in “his” hotel. (As the sole hotel worker seen on stage he stands for the entire hotel staff and management. By extension, as the person in charge of the space in which the action of the play occurs, he represents Canadian authority figures in general.) He serves as a measure of the subtle changes taking place, and his own gradual appreciation of the influence of the guests on the space suggests a larger theme of host country and refugee guests in mutual adaptation. For example, by Act Two, although he still ignores his refugee guests when he is preoccupied with tasks such as vacuuming, and at first doesn’t understand when Spanish-speaking Fat Jorge requests a record player, he gathers what is wanted, delivers it, and even comments appreciatively when the record is played: “That’s remarkable music! Thank you for letting me listen to it! We’ll keep the record player here now, by the lava lamp. You can listen to your records all you want. All you want. Remarkable music. Remarkable” (86). The sounds associated with the hotel have thus been enhanced, and the set modified slightly by the addition of a prop. Somewhat later in Act Two, when the Receptionist explains to Isabel (“Calladita”) that the cleaning lady has left, he comments indirectly on such negotiations: “The lady quit after you guys got here, but I wouldn’t take it personally” (99). He intends to be polite; he invites Isabel to take the post herself if she wishes, and save the trouble of waiting for the Social Worker to find her a job. But the implication of his ameliorating comment (“I wouldn’t take it personally”) is that collectively the refugees who occupy the entire hotel10 have made it too different, too Chilean, for the former cleaner. In this sense the hotel becomes an in-between locus—foreign to the refugees in its Canadian-ness, and for some Canadians such as the cleaner foreign also (too much so) but for opposite reasons. Thus a necessary process of mutual modification unfolds.

27 In a different sense, the guests modify the hotel (and vice versa, contiguity having its effect) as romantic relationships develop between the disparate characters thrown together by chance in the limited hotel space. This may seem an obvious plot development, that couples should come together and transform the anonymous, foreign space of a Canadian hotel room into something approaching a home. But Aguirre gives her characters lines of great beauty, and lifts such potentially place-transforming unions out of the realm of cliché. She shows that the characters themselves, very different in their individual persons and backgrounds, are drawn to one another not so much by the usual forces of common interests and compatibility, but by the consequences of oppression and torture, and by longing for the country from which they are exiled. So she stages a love scene between Manuel and Cristina (Condor Passes and Cakehead), two characters who are associated because they attempted suicide separately but simultaneously, wherein Cakehead seduces Manuel by talking about the most evocative and elusive sensory experience—scent: “Like home. Your poncho, your sheets, the armpit of your shirt, it all smells like the house where I was born, with the kelp and the seaweed drying on the sill ... You smell like our roots, you smell so good, so good, so good, I could burst from the smell of it all” (The Refugee Hotel 115). Language makes a seascented Chilean home of the Vancouver hotel room. The scent, of course, is something the audience can appreciate only in imagination, although it surely alters the affective associations of the hotel space on view, associations tinged by the emotional warmth of the scene just enacted and (for those who might know the south coast of Chile) by recollected smells.

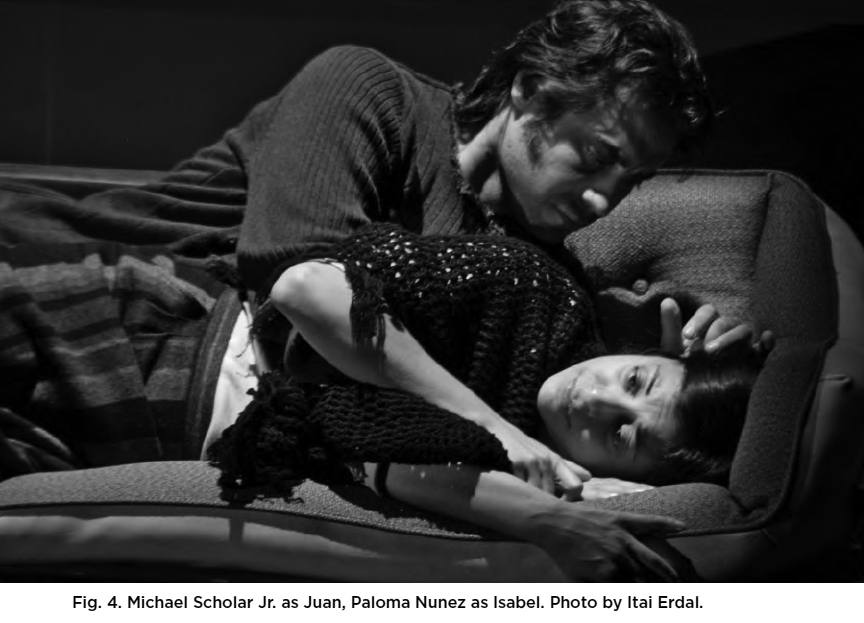

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

28 At certain junctures punctuating the play, the presentation space is also altered by lighting changes (in the Alameda production) and by changes in the soundscape (according to the play text), which mark the appearances of a male Cueca Dancer and nighttime flashbacks to scenes of torture. These changes intermittently redefine the appearance and mood of the visible space and cumulatively create a palimpsest effect. In these moments, the Chilean past history of the characters remains like a partly erased trace upon the presentation space as the audience watches daylight events unfold in the 1970s of the Canadian hotel. The Cueca Dancer, for instance, usually appears in association with a time-shift. He dances at the close of the prologue, like a mythic “pomp” character introducing the transition from the contemporary Prologue spoken by Adult Manuelita back in time to 1974, and the “bean bag” and “lava lamp” of the hotel (The Refugee Hotel 17); and dances again during the conclusion of the Epilogue, as Adult Manuelita recounts what happened to the refugees and to subsequent occupants of the refugee hotel after the end of the events of the play. He also dances at the beginning of Scene Two, as Fat Jorge screams during a nightmare of his past torture so wrenching he wakes to vomit (27), and again at the moment when Manuel tells the doctor about the torments inflicted on his body in Pinochet’s prisons (56). The Cueca Dancer marks just one passage in the play that seems focused on the 1970s time of the hotel, but this is the scene of Manuel and Cristina’s love-making, a scene which commingles the hotel with a scent-evoked past Chilean home. As one reviewer comments, the Cueca Dancer seems to be a mythic figure, “at once a symbol of the (highly gendered) national and political identity that Aguirre’s characters have lost upon their exile to Canada, and also a representation of the collective incorporation of the trauma they experienced in their now distant country” (Etcheverry). Though associated strongly with the past, as I have noted, each appearance of this figure leaves the audience with a powerful impression that affects their perception of the performance space and of the events enacted there in the 1970s present of the play. I suggest that the Dancer indicates thematically that the refugees sheltered within the fictional hotel, different as they are, collectively alter the meaning of the place because they bring the cultural and political experiences he represents with them into their present. The Dancer literally transforms the presentation space via the percussive sound of his dance in hard-heeled boots and spurs (“Making” episode 7). The lighting, likewise, reshapes the presentation space whenever he appears: the designer Itai Erdal created a distinctive sculptural effect (very different from the usual lighting used in the production) by lighting the Dancer’s body from the side (“Making” episode 8). This dynamic figure would dominate the playing space and linger in the mind.

29 In the nighttime episodes, in which characters experience traumatic flashbacks to scenes of their torture in Chile, the presentation space is likewise transformed by lighting in the Alameda production. Designer Erdal commented that for these scenes he employed a second form of lighting distinct from that used in the rest of the play. He illuminated the figures involved in these scenes from directly above, so as to produce harsh shadows on their faces. While the special lighting helped to transport the action to a past prison or concentration camp, a location of torture in Chile, the participation of other refugee characters in the hotel (characters not directly involved in the action of the scene) made the thematic point that trauma is not left in the past. In a real sense, the hotel and its 1970s present is also the Chilean past. During these nighttime episodes, that is, when Fat Jorge and Flaca, and Manuel the martyr, assume the positions in which they once were tortured and relive their torment, the rest of the cast moan, cough, pray, and weep, helping to “create the soundscape” (The Refugee Hotel 87) of Chilean prisons. By their collective vocalization they indicate that many more than those who were physically tortured bear witness and suffer. Participating from their dimly-lit but still visible hotel rooms (on the same level as audience members seated in the mezzanine at Theatre Passe Muraille), they bring the past into the present of the hotel.

30 If the hotel as fictive location and presentation space is altered in bold and subtle ways, and the host characters who represent Canadian authority (the Social Worker, the Receptionist) allow themselves to be changed by their guests without demanding that they “speak our language in all the senses of this term” (Of Hospitality 15), the refugee characters also adapt. For individual characters, the psychological struggle to find a “between” space (where the individual is informed by both Chilean and Canadian environments) is expressed partly through rapid oscillation between tragic and comic tones. One might venture that the past tragic violence of imprisonment and torture (recalled in flashbacks) repeats as comedy when two simultaneous suicide attempts fail: Cristina tries to gas herself in an electric oven, Manuel plunges several stories into a dumpster filled with fluffy insulation. The fortuitous and absurd failures of suicides produced by past trauma suggest that life in Canada is safer, less extreme, perhaps even less significant: a martyr, the plot implies, can adapt to surviving. Juan’s job advertising a restaurant while wearing a ridiculous chicken costume implies a similar adaptation to a safer and less heroic life. Marking the transition from tragedy to comedy, Fat Jorge gives Manuel and Cristina jokey nicknames based on the methods of their attempted suicides: Manuel who jumped from the hotel and flew by the window “like the King of the Andes” becomes “Condor Passes” and Cristina, who put her head in an oven, becomes “Cakehead” (The Refugee Hotel 80). Perhaps such names are designed to help keep them in the present realm of comedy: “You lonely fuckers. You lonely fuckers,” Fat Jorge says after everyone laughs at the new names (80).

Theatres, Blogs, and Hospitality

31 As a theatrical event, The Alameda Theatre Company production also contributed to the exploration of a “between” space of hospitality in its theatre and audience spaces, and in Toronto’s figurative cultural map. The theatre space became a place of reciprocal exchange between hosts and guests: Theatre Passe Muraille, long a mainstay of the Toronto theatre scene, as part of an ongoing program to foster new theatre welcomed the first production of the Alameda Theatre Company, newly founded by Marilo Núñez to be a vehicle for Latino/Latina theatre (“Making” episodes 1, 2, 6, 10). In an auditorium that holds approximately 180 people, and places all of the spectators quite close to the stage due to mezzanine seating, audiences (figuratively guests of the Alameda company) were encouraged by the intimate space to appreciate the skills of an unusual cast. This cast was predominantly Latino/Latina, with the exception of Cheri Maracle, a First Nations actor playing Cristina, an Indigenous Mapuche Chilean, and the three actors who took the roles of the Social Worker, Receptionist, and hippy activist Bill O’Neill. As noted earlier, the mezzanine seating placed many spectators on the same level as the personal spaces of the hotel bedrooms, adding to the actors’ opportunities to create subtle communicative connections. Thanks to the video blog, “Making The Refugee Hotel,” the potential intimacy between the audience and the theatre company was enhanced; audiences gained virtual access to behind-the-scenes spaces where costume, set, lighting, and sound designers worked and discussed their plans, actors rehearsed, and the playwright and artistic director spoke about their goals. Cast members in the light-filled Ossington rehearsal space (“Making” episode 5) seemed remarkably collegial and collaborative.

32 Because the company as a whole welcomed virtual visitors to their work spaces so openly and generously, audiences who visited the video blog, I speculate, were prepared to feel welcome when they went to the theatre, and to give their attention to the production in a generous and respectful spirit. Alameda enjoyed access to Theatre Passe Muraille’s space, and its mentorship. Seasoned Passe Muraille theatregoers, in turn, might have been instructively surprised by the characterization in the play: only the roles for the Canadian characters (Social Worker, Receptionist, and Bill O’Neill) are relatively two-dimensional. Terence Bryant, who played the Receptionist, expressed pleasure in seeing a common pattern reversed: minority actors inhabited complexly-written roles while in contrast he had to work hard to expand his thin character (“Making” episode 7). One reviewer likewise noted the two-dimensionality of the Receptionist, but did so disapprovingly because he perceived this as gay stereotyping rather than a reversal of patterns in the portrayal of majority versus minority ethnicities (Nestruck). On particular nights, the audience space was populated by invited groups for whom the play had special significance; there was an evening for members of Toronto’s Chilean community, and at other performances audiences included groups from several different centres that housed refugees (“Making” episode 10). The play enjoyed good attendance especially toward the end of the run, despite advertising only through word of mouth, Facebook, and the production video blog; favourable reviews undoubtedly helped (Kaplan, WBG, Mooney, Etcheverry). In effect, the production, and the Alameda Theatre Company, created a place for itself in the cultural space of the Toronto theatre scene, subtly altering the host place, presenting ethnic minority actors in uncommon roles, bringing new audiences to Theatre Passe Muraille, and in general making itself at home without allowing the “guest” young company to become completely absorbed into the “host.”

Coda: Canadian Hospitality

33 The spaces of Aguirre’s play speak thematically of a place between absolute and limited hospitality; in so doing, The Refugee Hotel contributes to a national political discussion about hospitality expressed in terms of hotels. The redefinition of the hotel (as fictive place and presentation space) analyzed in this essay, and indeed the use of a hotel to explore refugee experience, gains particular resonance when the play’s negotiation of a responsive and receptive version of hospitality is considered in the light of recent Canadian political discourse of hotels and national hospitality.

34 Carrie Dawson has analyzed references to hotels by Jason Kenney during his service as Canada’s Minister of Citizenship and Immigration between 2008 and 2013. On the one hand, Kenney likened the detention facilities used to house an increasing number of asylum seekers and non-status migrants to hotels. “It’s basically like a two- or three-star hotel with a fence around it” Kenney said, characterizing immigration detention facilities in Canada (qtd. in Dawson 826). He added that the detention facilities “are not jails” (826), even though the inmates in these facilities could leave only if they immediately exited Canada, abandoning their claims. And yet, Dawson points out, when addressing the responsibilities of citizenship, “Kenney argued that ‘Canada is not a hotel’.” Dawson uses discourse analysis to explore the tension between the Canadian ideal of hospitality and the realities of an expanding immigration detention system. The idealized national self-image of Canada as inherently hospitable is evident in both of the (contradictory) references to hotels above. The first attempts to obscure the harshness of the detention system, and the jail-like conditions in which detainees are held, by suggesting that they are not harsh but hospitable, in keeping with Canada’s ideal self-image, and thus that detainees are treated like hotel guests. The second usage assumes that Canada is hospitable and thus is vulnerable to exploitation, for example by those who seek asylum under false pretenses. To protect Canada from its own idealistic hospitality, the Minister must insist that Canada is not a hotel, not in other words welcoming to all. “Hotel” in the second usage also connotes luxury and pleasure, suggesting that outsiders who expect Canada to be a hotel are asking for more than they need or deserve.11 Dawson comments on the implications of this complicated use of hotel references in terms reminiscent of Derrida’s reflections: “hospitality is a deeply ambivalent concept that mobilizes assumptions about proprietariness and belonging while simultaneously emphasizing generosity and altruism” (827).

35 Hospitality, as an ambivalent concept, is entangled in Canada’s self-image, and in its immigration policies. In light of Dawson’s analysis of politicized hotel discourse, Aguirre’s Vancouver refugee hotel begins to look a lot like Canada. Dawson urges Canadians to let go of the myth of national generosity because it obscures our shortcomings (842). Aguirre likewise helps to dispel such mythology by showing that hospitality may be sorely limited. But also, by presenting refugees as agents who transform the space of the hotel, by demonstrating that the host gains as well as gives, that adaptations are mutual, that hospitality may be receptive in many senses, she—like Derrida—inspires commitment to a new cosmopolitics, and an ethics of hospitality based on mutual responsiveness and an evolving engagement of guest and host.

36 Una Chaudhuri, considering the past role played by the hotel in dramatic modernism, as well as the place of the hotel in recent drama, charts historic changes in cultural discourse. She argues that the hotel of modernism played a role within a poetics of exile in which home is coded as both the cause of exile and its goal; in modernist exilic poetics, the hotel “functioned as a surrogate home, as a stable container for the identity of the deterritorialized self” (244). It was a “haven for expatriate artists and writers” (244). After the midcentury, however, the figure of exile is “decisively qualified by the actual and widespread experiences of immigration and refugeehood” (173). The modernist poetics of exile has thus faded and no longer codes the hotel. Chaudhuri argues one of the main reflections of the change from a metaphoric to a literal understanding of displacement is in an altered model of subjectivity visible in the (mostly American) contemporary dramas she examines, dramas that trace “the difficulty of constituting identities on the slippery ground of immigrant experiences” (173). What of the hotel now? One possibility suggested by Chaudhuri is that the hotel may become coded as a “nightmarish abstraction,” the chronotope of the antipalatial (245). The Refugee Hotel is but one instance of current, Canadian, dramatic discourse of place, yet it may suggest new possibilities for an altered, more fluidly bounded model of place (comparable to the altered subjectivity Chaudhuri postulates) in which the hotel is coded neither as “stable container” nor as abstract anti-place. In emphasizing the ongoing, interactive adaptation of guest and host, refugee and place, I propose that a mutually constructed place and subjectivity may be figured by Aguirre’s hotel.