Articles

Towards Reconciliation:

Immigration in Marty Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix and David Yee’s lady in the red dress

When Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a public announcement of redress to acknowledge the early mistreatment of Chinese immigrants, he turned a new chapter in Canada’s legislative history. Postcolonial theatre offers a window into the lives of late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries immigrants, many of whom were subjected to exclusionary policies while attempting to become Canadian citizens. This article offers a comparative analysis of two plays: The Forbidden Phoenix by Marty Chan and lady in the red dress by David Yee. Such plays actively encourage readers and audiences to move towards reconciliation, a term used to describe the process of featuring immigrant characters onstage in order to challenge the roots of stereotypes and race-based policies. These plays, though contrasting in style and tone, gesture towards the importance of immigrants to Canadian history, and, more specifically, how theatre artists are attempting to understand the legacy of race-based policies and prejudices on the cultural relations of the twenty-first century.

Quand le Premier ministre Stephen Harper a officiellement offert des excuses pour les mauvais traitements infligés aux premiers immigrés d’origine chinoise, un nouveau chapitre de l’histoire législative s’est ouvert au Canada. Le théâtre postcolonial jette un regard sur la vie des immigrants de la fin du XIXe et du début du XXe siècle, dont plusieurs ont été assujettis à des politiques d’exclusion au moment de demander la citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, Chang propose une analyse comparée de The Forbidden Phoenix de Marty Chan et de lady in the red dress de David Yee. Ces pièces participent à une mise en scène de la réconciliation, processus par lequel des personnages immigrants sont représentés sur scène dans le but de combattre les sources des stéréotypes et des politiques fondées sur la race. Bien que les deux pièces à l’étude contrastent autant par leur ton que par leur style, elles montrent l’importance des immigrants pour l’histoire du Canada et, plus spécifiquement, la façon dont les artistes de théâtre tentent de comprendre le legs des politiques et des préjugés raciaux et leurs effets sur les relations culturelles au XXIe siècle.

Reconcile: To bring (a person) again into friendly relations to or with (oneself or another) after an estrangement.1

1 Another chapter in Canada’s immigration history was written on June 22, 2006, when Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a public government apology to people of Chinese descent who suffered injustices during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His speech was widely seen on television and well documented for future references and generations:

The apology included an announcement of formal redress, which provided individuals who paid the Chinese Head Tax (or their living spouses) with $20,000 in compensation. Although few of these men were still alive to personally receive the payments, the declaration itself marked a key chapter in Canada’s legislative and cultural history. However, while it may seem that some level of settlement and closure has been achieved on this issue, theatre artist Guillermo Verdecchia has reflected on this public apology, declaring that, “while redress may be a done deal legally and politically, it’s far from over psychically.” Verdecchia’s observation points to the long-term effects that repressive legislative acts have on “an individual’s or a community’s psychic life,” acknowledging that events such as the government’s redress settlement “marks the beginning rather than the end of a process towards justice, healing and reconciliation” (“Foreword”).

2 At its most basic level, the term reconciliation often refers to an attempt at re-establishing trust and respect between groups, or improving relations with another individual or group, whereas the term redress often refers to an act of reparation, which may involve an apology, or payment, or symbolic compensation for a “wrong.” Other scholars writing about reconciliation concur with this idea. Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham espouse the idea that “the culture of redress does not simply amount to a dynamic of demand and response through which scores are settled, debts repaid and apologies delivered; it effects a much wider epistemological restructuring” (10). Taking these pressing issues to hand, a growing number of scholars over the past decade have begun to theorize reconciliation. In particular, theatre scholars have contributed to this conversation by examining postcolonial theatre’s potential to improve human relationships.2

3 This article argues that immigrant-themed plays such as David Yee’s lady in the red dress and Marty Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix actively encourage readers and audiences to move towards reconciliation.3 Such plays can be seen as part of a postcolonial critique advanced by playwrights interested in chronicling the history of social injustices and discrimination perpetrated against immigrants. Through their unique intercultural aesthetics and social commentary, these plays invite a renewed and critical view of Canadian history. The adjective “towards” suggests that reconciliatory processes are ongoing and incomplete when redress or financial payment has been achieved. Further, playwright Marjorie Chan suggests that plays written about Chinese Canadian history seem “compelled to reach back into our cultural heritage,” providing a self-reflection while simultaneously looking “forward to complete the picture of ourselves” (“Preface,” Love + Relasianships, Vol. 2, iv). The two plays under investigation offer a critical counterpoint to the commercially-oriented “attempt by mainstream theater companies to ‘multiculturalize’ their repertoires with the addition of works written and (sometimes) performed by minority artists” (Shimakawa 46), the concomitant practice of (re) appropriation, “and the vogue of intercultural productions of Western theater works” (46). It is interesting to observe the literary efforts of David Yee and Marty Chan as part of an ongoing trajectory of postcolonial theatre that includes plays such as Ric Shiomi’s Yellow Fever (1982). Working in a vein similar to Shiomi’s work, Yee’s lady in the red dress and Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix critique hegemonic cultural practices and “engage critically in the reconstruction of a Canada that embraces a fluid performance of cultures, histories, subjectivity, and diversity, rather than the tolerant and prescriptive version of multiculturalism that too often defines the nation” (Tompkins 299-300). In fact, it is worth noting that both Chan and Yee have recently captured the attention and accolades of theatre scholars, pointing to a growing interest in their work as postcolonial Canadian playwrights.4

4 Chan and Lee’s plays also add significant context to the polarized legal debates surrounding the legacy of the Chinese Head Tax and subsequent Exclusion Act, gesturing to the belief “that Canada’s immigration regime and anti-Chinese racism needed to be contextualized within this broader colonial period of nation-formation” (Mawani “Cleansing” 1356). Both lady in the red dress and The Forbidden Phoenix contain three basic features: first, the presence of a Chinese immigrant as protagonist or principle character, often portrayed within familial contexts; secondly, the recollection of social injustice and discrimination experienced by Chinese immigrants; and finally, a clear movement towards reconciliation itself through the reenacting of history and its connection to an evolving present condition. Before undertaking a comparative analysis of Yee’s lady in the red dress and Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix, this article surveys some of the current thinking about social injustice and reconciliation in Canada with a view to contextualizing the role of postcolonial theatre within the broader debate.

Towards Reconciliation: A Brief on Social (In)justice and Social Drama

5 Although the term reconciliation often evokes Aboriginal and settler relationships, Renisa Mawani claims that there has been “persistent and perilous contacts between Chinese, aboriginal peoples, and those of mixed-race ancestry” for hundreds of years (“Cross Racial” 166). Despite this fact, “genealogies of Indigenous-European relations and of Chinese migration to Canada’s west coast have, for the most part, been written as distinct and separate” (166). Taking this into consideration, any movement towards improving relationships between Anglo-Canadians and Chinese-Canadians would need to acknowledge the history of collaboration, the causes of discrimination, and the stereotypes that created false perceptions of Chinese during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). Even though migration from Asia predates the CPR (1881-1885) and continues to this day, the plays under investigation focus on the wave of immigrants who principally arrived during the midto late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As such, Chinese immigration must be seen as a key feature in Canada’s evolution as an emerging nation, and yet, it remains pertinent to understand contemporary redress for the Head Tax and Exclusion Act not simply as fait accompli. Speaking about the Japanese Canadian experience, Roy Miki suggests that, “redress awakened memories of a past that had not been put to rest. When their surfaces were rubbed, even in casual conversations, individuals relived the scenes of uprooting, confinement, and suffering; once again unable to mediate the violations they had endured” (314-16). Though immigrants from China were not forcibly removed, as Japanese Canadians were, it is now known that the Chinese were the most targeted cultural group in the country, facing over one hundred acts of legislation that contained or limited their rights in Canada.5

6 Renisa Mawani writes about the importance of a critical and nuanced historical record “that characterizes Canada as a colonial power built not only on the colonization of First Nations and the appropriation of Indigenous territory, but also the coercive labour exploitation of Chinese migrants (and other migrants of color)” (“Cleansing” 130-1). Further, Mawani describes the plight of immigrants and the characters who come to represent them: “Their struggle has centered on the resurrection or evocation of a particular history of racial injustice, or what Foucault has termed a ‘counterhistory’” (130). It could be said that any retelling of this “counterhistory” seeks to reverse the cultural erasure of trauma from contemporary Canadian thought. Noted poet, scholar, and activist Roy Miki outlines the importance and impacts of “counterhistory”:

The very fact that some North Americans experience cultural amnesia and refuse to accept culpability demonstrates the need for some attempt at reconciliation. Through a deliberate recollection of the past and reenactment of social injustices, theatre can provide a nuanced and documented history of early Chinese immigration. Arguably, the complexity of such lives has been absent from mainstream public discourse, until the 2006 “statement of apology” offered by Stephen Harper. Despite such gestures, the language surrounding the reconciliation still seems reluctant to admit harm resulting from policies such as the Chinese Head Tax and Chinese Exclusion Act. In Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation through the Lens of Cultural Diversity, playwright/filmmaker Mitch Miyagawa writes:

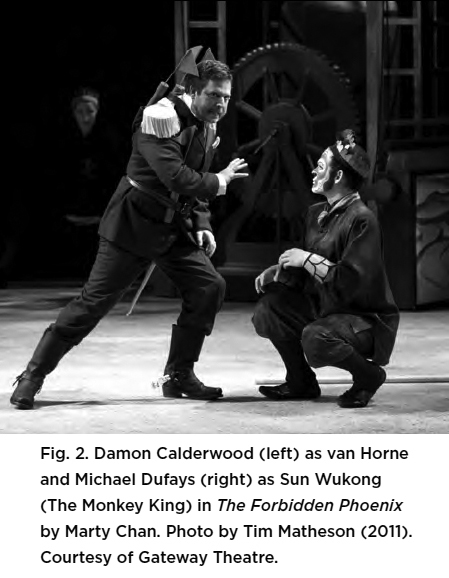

Other scholars working in the field of reconciliation have offered explanations that complement Miki and Miyagawa’s thinking about neoliberal language. Renisa Mawani speaks of the language of the courts, which tend to favour a positioning “that Chinese migrants ‘chose’ to come to Canada and voluntarily paid the head tax” (“Cleansing” 129), which provokes some members of the public to draw easy conclusions, resulting in a situation where “many have questioned whether Chinese Canadians have been ‘harmed’ and are ‘deserving’ or ‘worthy’ of financial compensation” (129).

7 If postcolonial theatre is to wrestle with social injustice, it must examine the violence perpetrated against immigrants during the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. As mentioned previously, scholars Miki, Miyagawa, and Mawani develop an argument that examines how neoliberal and legal discourses attempt to separate the past from the present, and immigrant choice from government responsibility. Canadian citizens of all cultural backgrounds can then distance themselves from historically rooted prejudice, foreclosing any sustained discussion around the complex legacies and cross-cultural impacts of state-sanctioned discrimination. By contrast, a reconfiguration of history as a fluid, two-way path between past and present seems necessary. As Andrew Dobson states: “Whereas affirmative recognition remedies tend to promote existing group differentiations, transformative recognition remedies tend, in the long run, to destabilize them so as to make room for future regroupments” (145). This article analyses two play texts that recollect historical injustices while reenacting alternative “regroupments” in hopes of making Canada a friendlier place for immigrants and citizens alike.

A Heroic Immigrant: Marty Chan and The Forbidden Phoenix

8 On his personal website, Marty Chan reflects on his childhood, recalling how his immigrant parents used to work long hours in business, leaving them little leisure time to spend with him as a child. Since they could not read to him in English, Chan discovered his own world by reading and writing his own stories (“Marty’s”). Chan’s writing crosses multiple genres and media, ranging from novels and youth fiction to scripts for television, radio, and theatre. Chan recalls that one of his earliest works, Weeping Moon (1997), had little Asian-themed content because he was conscientiously seeking to “avoid being stereotyped as the Chinesehyphen-Canadian writer” (“Ethnic” 112-13). This strategy was challenged when he penned the play for a decidedly all-Caucasian cast; one friend suggested that he should have written something more “Asian” or “close to his heart” instead (113). Soon thereafter the playwright began writing with more self-reflective, familial themes.

9 One of Chan’s most enduring and widely produced works from this period is Mom, Dad, I’m Living with a White Girl (1995), his first breakthrough success in North America. Joanne Tompkins infers that the play “deliberately misrepresents both the ChineseCanadian experience and the stereotypical, dominant Anglo-Celtic Canadian experience” and offers audiences a “challenge [to] uncritical multiculturalism” (296). Tompkins further notes that Chan uses signifiers of “Chineseness” to achieve a level of humour while simultaneously suggesting the “impossibility of inhabiting these stereotypes” (298). Indeed, the issue of stereotypes bleeding from the world of theatre into real life, and vice versa, seem to have particular resonance for Chan. Even after a sold-out run of Mom, Dad, I’m Living with a White Girl in Toronto by Cahoots Theatre Projects, and a successful run in Vancouver at Firehall Arts Centre, he remembers one producer remarking that “the play only worked in those cities because they had a large Asian population” (Chan 114). However, when the play was produced in cities without significant numbers of Asian Canadians or Asian audiences, Chan soon discovered that it held a wider appeal than the producer had assumed, especially after the show toured successfully to Nanaimo, Kamloops, Edmonton, and Saskatoon (114).

10 The most recent production of Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix was produced by the Gateway Theatre in Richmond, BC, and was reviewed by The Georgia Straight weekly. Colin Thomas praised the show, suggesting that “western theatre is seldom so robustly and accessibly symbolic, so the broad strokes of this entertainment is refreshing,” further illuminating “a score that blends the intervals and ornamentations of Peking Opera with the show-biz sensibilities of Broadway.” The critic concluded with the observation that “very little theatre reflects the Lower Mainland’s cultural diversity. The Forbidden Phoenix does, and that part is exciting” (Thomas “The Forbidden Phoenix”). Given Chan’s success, it is becoming clear that he plays a unique role within Canada’s theatre culture, standing as a socially-responsive interlocutor who uses drama to “intervene publicly in social organization” through a retelling of Asian Canadian histories which offer a “critique of political structures” (Gilbert and Tompkins 3). The aforementioned context illuminates Chan’s desire to speak from a decidedly postcolonial perspective, one that has captured the interests of wide-ranging audiences and critics alike. Compared to contemporaries such as Guillermo Verdecchia, Marie Clements, or Carmen Aguirre—who also write from particular regional, intercultural, and linguistic perspectives—Chan’s success may seem understated upon first glance. Nonetheless, his steadfast contribution to the aesthetic diversity and political discourses within the Canadian theatre milieu spans the course of two decades. The playwright’s most recent foray into uncovering the roots of social injustice and the portrayal of immigrant characters as leading protagonists seem especially pertinent in 2015 given the Conservative government’s approach to immigration policy and the ongoing legacy of fear and misunderstanding associated with immigration “post-9/11.”

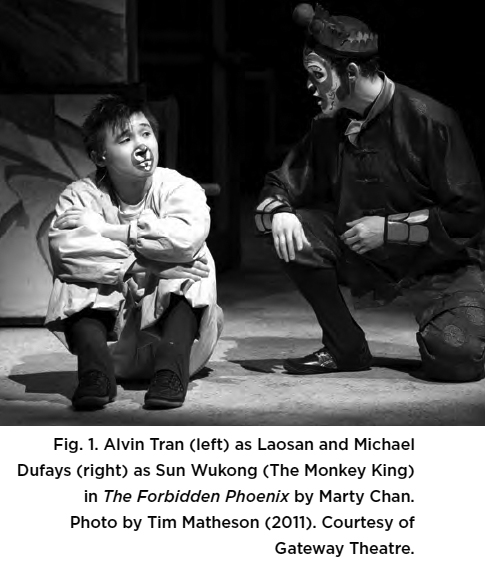

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 The storyline of Marty Chan’s play, The Forbidden Phoenix, is quite straightforward. Loosely adapted from the sixteenth century classic Chinese novel by Wu Cheng’en, widely known as Journey to the West, the play features the same protagonist, Sun Wukong, who leaves his son behind in order to find opportunities elsewhere. He walks through a waterfall, acting as a portal between China and Canada, only to be faced with the likes of “van Horne”, an overly ambitious industrialist who wants to enter a place called “Forbidden Mountain”; this particular locale is a symbolic reference to Gumshan or “Gold Mountain,” the name Chinese immigrants gave to the West Coast of British Columbia and the mountainous Sierra Nevada region of California, US, as the lure of the gold rush was widely known locally and abroad. Throughout the play, Sun Wukong is tested morally and physically, pitted against enemies who want him to sacrifice his own safety and integrity in exchange for the assumed riches of the Forbidden Mountain. The play alludes to moments in Canada’s history—the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway and its use of labour, replete with characters based on real individuals—while providing an allegory for the plight of early Chinese immigrants. The narrative unfolds episodically, signalling to readers and audiences that the play references an actual moment in Canada’s immigration history and formation.

12 A careful reading of The Forbidden Phoenix, with its fantasy-driven plot, reveals that Chan has embedded a strong dimension of critical commentary within the storyline itself. As a postcolonial play, it “tell [s] the other side of the conquering whites’ story in order to contest the official version of history that is preserved in imperialist texts” (Gilbert and Tompkins 12). In the actual play text, the protagonist begins with a self-declaration: “I am Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, and this is my story” (Chan 3). The presence of a mythic protagonist based on a Chinese hero allows the play to move towards reconciliation by drawing attention to “the other side” of Canadian history as seen through the eyes of a Chinese immigrant. Those aware of Sun Wukong’s history as it is told in the famous novel, Journey to the West, would know that in the original story the folkloric hero travels alongside his master, a monk, and the pilgrimage was clearly a collective experience.6 Chan takes great liberty in transplanting Sun Wukong into a new context, and by representing him as a lone figure, he gestures towards the journey of Chinese men who often came to Canada in the nineteenth century, often without friends or family. As such Sun Wukong (Monkey King) occupies a “paradoxical status” of representing “a quintessential icon of mutability” as well as “a paradigm of cultural continuity” (Rojas 334).

13 The transformation of this mythic hero into an immigrant protagonist is a feature that also connects the history of Canada to China, much like other postcolonial plays that “[incorporate] indigenous material into a Western dramaturgical framework,” even if the content is somewhat “modified by the fusion process” (Lo and Gilbert 36). It is worth noting that “West” in the original Journey to the West novel refers to Sun Wukong’s travels from China (East) to India (West), where the Buddhists scriptures were to be found. Chan’s ingenious replacement of India with Canada complicates and undermines the notion of the “West” from a centralized North American or European perspective. By drawing upon the original text in order to tell the story of a Chinese immigrant’s journey to Canada, Chan slyly reminds readers that there are other definitions of “West,” and by essentially reconfiguring geographic borders and boundaries his plays seems “driven by a political imperative to interrogate the cultural hegemony that underlies imperial systems of governance, education, social and economic organization, and representation” (35). Even though the play is performed almost wholly in English—the postcolonial lingua franca of English Canada—the presence of Sun Wukong onstage begins to unsettle cultural hegemony as he comes to represent the thousands of Chinese immigrants who worked on the CPR between 1881-1885. Chan makes this connection explicit on the first page of the published play, where he includes a dedication: “To the Chinese immigrants who helped build Canada’s railroad” (The Forbidden Phoenix). The immigrant character, then, carries within him the “value of cultural fragments as they are moved from their traditional [Asian] contexts” (Lo and Gilbert 36).

14 As a translator who specializes in the Monkey King, Anthony Yu describes the figure of Sun Wukong as an “animal-attendant who was also endowed with enormous intelligence and magical powers” (x). As such, Sun Wukong fulfills a dual function as both hero-protagonist and ordinary or “common man” who finds himself somewhat compromised as he navigates his way through foreign land, proving that “the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were” (Miller 3). To see Chan’s dramatic character, Sun Wukong, embrace a tragic role is refreshing for it gestures towards the plight not only of immigrants, but the average person who might not otherwise make his or her way into the history books. In his article, “Death of a Salesman: A Modern Tragedy?” (1958) Arthur Miller shared his ideas about the tragic hero, stating:

By drawing attention to the extraordinary and heroic trials and tribulations of Sun Wukong, Chan positions his story’s protagonist as having magnitude and depth. As a noble representative of the early migrants from China, Sun Wukong takes on a role that begs for further attention, quite arguably, inviting critical empathy and a renewed understanding of Canada’s immigration history, writ large.

15 Ironically, Sun Wukong holds both an esteemed place as “Monkey King” in his native land of China and the burden of a working-class or “common man” in his adopted land of Canada. In keeping with his status as a heroic figure, Sun Wukong’s journey must include challenges along the way, including battles with over-protective guards, soldiers, the Empress Dowager, and the “van Horne” character, a self-serving engineer who seeks to break Forbidden Mountain for his own benefit. The latter character is based on the real-life William van Horne, the American-turned-Canadian railroad magnate who provided leadership to the CPR as General Manager, Vice-President, and President, overseeing its operations and completion. Chan uses this collapsing of reality and fiction in The Forbidden Phoenix as an effective metatheatrical device that encourages readers and audiences towards reconciliation by re-imagining the nuances of historical relationships. In the play, the van Horne character fulfills the antagonist’s role, espousing false promises to his opponent Sun Wukong, who hopes of a better life. “Sun Wukong, let me welcome you to Terminal City” (Chan 20), van Horne booms, calling Vancouver by a nickname still used today, which references its placement on the most western or last “terminal” point of the CPR line. Of course, the West Coast of British Columbia is also where the great English explorer Captain George Vancouver first established a port. In real life, William van Horne once told real estate agent Arthur Wellington Ross: “The name Vancouver strikes everybody in Ottawa and elsewhere most favourably in approximately locating the point at once” (van Horne, qtd. in Berton 305).

16 Even though Chan changes the facts so that ku li in his play lose their lives to the creature known as Iron Dragon instead of dying in dynamite blasts as real-life Chinese railroad workers did, the irony is not lost. The “van Horne” character, based on the real-life charismatic figure, is portrayed as possessing false empathy and endless ambition and determination. In the same act he says: “Light this wick and this zha yao becomes a powerful weapon. With it, you can avenge all the ku li who lost their lives to the creature” (Chan 22). In response, Sun Wukong sings, “So I’ll lay tracks to your dream, I’ll blast through the creature’s shield” and closes the scene with “Remember our deal, Horne” (25). Clearly, the van Horne character represents greed and unbridled capitalism, serving as the primary antagonist to Sun Wukong. In this sense, Sun Wukong, as immigrant, fulfills what Arthur Miller has described as a “character who is ready to lay down his life,” if not for his own “sense of personal dignity” then in order to “gain his ‘rightful’ position in his society” (4). Though Miller espoused this theory to coincide with and rationalize the play structure and protagonist in Death of a Salesman, the issues of building self-dignity and a rightful position in society can be readily applied to Chan’s play.

17 Although Chan’s play dramatizes the actual struggles of Chinese immigrants, the playwright also takes great liberty in fictionalizing and re-imagining the broader historical record. It is now known that many Chinese labourers risked their lives during the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In many instances, the Chinese were made to accept extremely unsafe working conditions.7 To recollect this moment, the Sun Wukong character in the play enters Forbidden Mountain and battles the site’s principle protector, Forbidden Phoenix. Sun Wukong states: “Horne said you had no respect for any life but your own,” (Chan 28) and Phoenix responds: “He’s the one who doesn’t care for life. He’s been sending those poor ku li here. Their zha yao exploded in their hands as they climbed the mountain” (28). While the railroad workers or ku li are never seen dying or suffering in the play, the text alludes to particular real-life instances and details that have been negated in narratives of Canadian history that promote the benefits of having built the Canadian Pacific Railway. The latter approach tends to focus on issues of economic growth and nation building while simultaneously forgetting the lost lives and discrimination that plague the memory of the CPR’s actual construction. By referencing the dangerous working conditions of Chinese immigrants, the playwright’s work reenacts a “cross cultural negotiation at the dramaturgical and aesthetic levels,” one that “frequently assumes some kind of interpretive encounter between differently empowered cultural groups” (Lo and Gilbert 13).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 218 As the play closes the main protagonist is seen reunited with his son, Laosan, who says “I love you, Father.” Sun Wukong simply responds, “I love you” (Chan 66). This simple exchange of affection between family members begins “working towards a politically conservative empathy that includes difference” (Rogers 426), and one that encourages audiences to “read emotions from the body” (429). Chan ensures that immigrant characters are portrayed in love, and capable of love, countering hegemonic portrayals of love, which often “became the preserve of the dominant racial group,” socially constructed “such that love is also a whitened emotion in mainstream representation” (429). One way to read the play’s uplifting closing would be as an homage to, not negation of, the tragic fates of most real-life Chinese labourers in Canada, or those who were never reunited with their wives due to the impacts of the Chinese Head Tax and Chinese Immigration (Exclusion) Act.

19 Marty Chan eschews any specific mention of race-based policies that separated Chinese immigrant men from their families and excluded them from public affairs simply because of their place of origin. It should be noted that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and Canada’s Multiculturalism Act, introduced decades later, deem such acts of discrimination as unlawful and unacceptable. That said, the play does provide an interrogation of van Horne’s hyper-capitalist mindset that fuelled the building of the CPR. Further, the play gestures towards reconciliation by having the “common man” or Chinese immigrant portrayed at the centre of the action, asking readers and audiences to empathize with his trials and tribulations. By placing the character of Sun Wukong (Monkey King) from the epic novel Journey to the West within the narrative of the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway, Chan attempts to create a nuanced representation of Chinese immigrants through “discourses of resistance (which) speak primarily to the colonizing projects of Western imperial centers” (Lo and Gilbert 35). Finally, Chan’s postcolonial theatre challenges texts that erase immigrant stories and characters, bringing nuanced views of Canadian history to stages for public consideration.

Immigrants’ Policies and Plight: David Yee and lady in the red dress

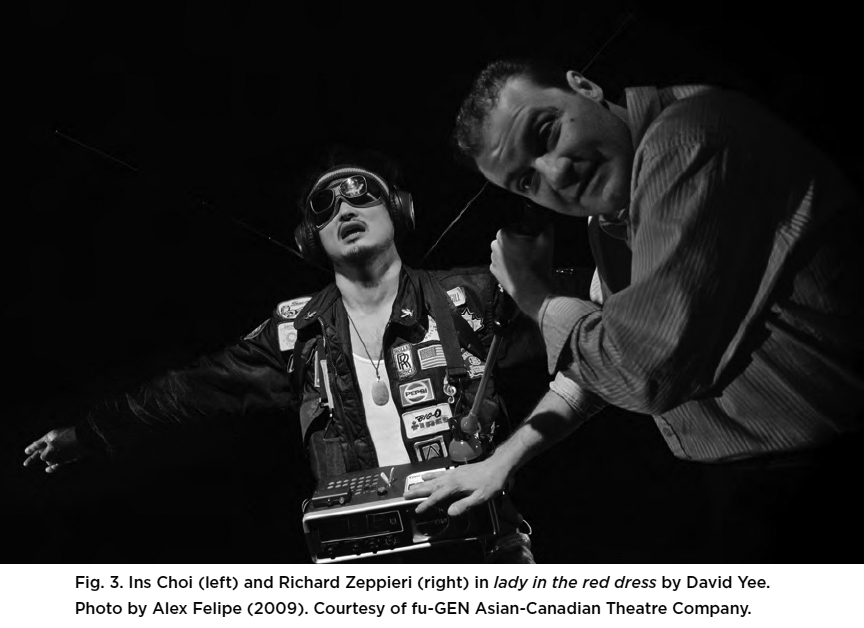

20 While Chan works across literary genres, balancing his time between playwriting and book-length fiction writing, David Yee is known primarily as a theatre artist based in Toronto, where he was born and raised. In 2002, he co-founded fu-GEN Asian Canadian Theatre, and in 2003, the company produced filial, his earliest work.8 When Yee began writing plays, he also eschewed his cultural heritage in a manner similar to Chan’s. In an interview with Glenn Sumi of Now Magazine, the playwright revealed that he was “naive” when he left York University. Reflecting back, he says he would “distance myself from Asian-Canadian theatre” in order to “show everyone I was different.” He has since come to embrace, not deny, his Asian heritage (“Hey”). If filial, Yee’s debut play, was tinged with a certain level of naive earnestness, lady in the red dress (2009) showed his artistic maturation, catapulting the playwright into the professional milieu with seven Dora nominations and a spot on the shortlist for the 2010 Governor General’s Literary Awards for Drama. In another interview in Ricepaper magazine, Yee admits to the arduous process of research: “when you’re writing a play based on historical events [. . .] you really need to know the legitimate history of it all before you can start making it up” (“Future”). lady in the red dress was taken through an inaugural week-long developmental process with Don Hannah at Playwrights Theatre Centre in Vancouver, followed by ongoing feedback from his essential collaborators, such as Guillermo Verdecchia. While Yee continues to create a thoughtfully varied body of work, quite arguably lady in the red dress stands as his most lauded and critical postcolonial theatre project to date.

21 In lady in the red dress,Yee tackles the very structures that oppressed Chinese immigrants who came to Canada at the turn of the century, seeking a direct “engagement with and contestation of colonialism’s discourses, power structures, and social hierarchies” (Gilbert and Tompkins 2). Yee wrote the play as a direct response to the race-based policies that sought to contain, label, and ostracize members of the Chinese community, and the subsequent efforts that took place in the years preceding the 2006 redress. On the first blank page of the published play text, Yee offers a dedication similar to the one penned by Marty Chan. He writes: “This play is dedicated to the 81,000 Chinese who paid the Head Tax, to the countless number who were kept from their families and loved ones during the Exclusion, to those who died building the foundation of this country only to be disavowed and forgotten” (lady). This immigrant-themed narrative reflects the playwright’s own close engagement with the redress for Chinese-Canadians; in 2006, Yee was commissioned to design a media presentation to be used before the Toronto broadcast of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s parliamentary apology. In the introduction to his published play, Yee recalls the government wanted “a happy collage” representing the Chinese experience in Canada, but instead he decided to provide “close-up images sourced from old photographs of the 1907 anti-Asian riots in Vancouver” (vii).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 322 In contrast to Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix, Yee’s play does not feature any character working directly on the railroad, nor is the railroad mentioned anywhere in dialogue. Instead, the playwright situates his characters in various time periods—namely the years 1923, 1943, and 2006—, each corresponding to a key era in Canada’s historical timeline of immigration policies. On July 1, 1923, for example, The Chinese Exclusion Act was implemented, ironically coinciding with (Dominion) Canada Day. For the next two decades, immigrants faced other forms of discrimination but the mood had changed when China’s “role in the world war against the aggressor began to register in the minds of white Vancouver society” (Anderson 172). The voices of antagonists and those who espoused anti-Asian sentiment subsided as Vancouver’s Mayor Cornett joined the Chinese War Relief Fund in 1943, the same year that union co-operation was high as three thousand Chinese workers in the shingle and shipyard industries threatened to strike (172). In 1946, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed, and in 2006, the Government of Canada offered an acknowledgement for discriminatory policies enacted during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. David Yee’s references to 1923, 1943, and 2006, then, are not arbitrary; rather, they provide cues by connecting the play’s characters and narratives with the progress of actual events in Canada’s broader immigration history.

23 A protagonist in lady in the red dress is Max Lochran, a negotiator working at the Department of Justice. Through the course of the play, Lochran meets a cast of characters— his own grandmother and grandfather, Willy, Biff and Happy, and Tommy Jade—who collectively reveal familial secrets from his past, provoking him by turns, gently and violently, towards a deeper sense of empathy. Near the beginning, Max is speaking on the phone with Linda, a representative of the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC). As the two characters debate over the issue of redress, Max says:

The character’s informal tone sets the mood for what will transpire in the following scenes. Lochran seems less than objective, siding with the government and revealing concerns around “inference around liability.” This scene reiterates similar terminology used by Prime Minister Stephen Harper on June 22, 2006: “For over six decades, these malicious measures, aimed solely at the Chinese, were implemented with deliberation by the Canadian state [. . .] This was a grave injustice, and one we are morally obligated to acknowledge” (“Address,” emphasis added). Shortly afterwards, in a flashback that returns to 1923, readers are introduced to Tommy Jade, the secondary protagonist and immigrant whose troubled story comprises the backbone of the play. Jade is seen talking to Mr. Coogan, an immigration official.9 Tommy inquires about his wife. He asks “I tell Cho-swan to come?” at which point Coogan responds:

In the above scene, Coogan has taken $600 from Tommy Jade: $500 as Head Tax for his wife and another $100 for a supposed “intercontinental relocation fee.” By introducing a government official into the scene, the play reminds readers about the subtle and overt kinds of discrimination that Chinese immigrants faced. In this reiteration, Yee seeks to create a space in which readers and audiences may begin to understand cultural dynamics by evoking “acts that interrogate the hegemony that underlies imperial representation” (Gilbert and Tompkins 11). Such representation has often portrayed the Chinese who entered during the exclusion years as “illegal immigrants,” but has often negated the fact that “Chinese prospects depended on officials who wielded absolute power over their futures and who had little accountability” (Mar 20). Lisa Rose Mar explains how Canadian-born citizens and immigrants alike remember the times when Chinese experienced detainment as they arrived by sea or rail (20). This is not to say that the system of discrimination imposed by the Head Tax and Exclusion Act was never questioned. Mar notes that “the general lack of strict enforcement of anti-Chinese immigration laws revealed that the public was of two minds about immigration” (22). Historical testimony reveals that illegal immigrants received support from non-Chinese foremen as well as their co-workers and business partners, who expressed a certain level of sympathy, cooperation, and alliance (22).

24 In addition to the Head Tax and Exclusion Act, playwright David Yee tackles the stereotypes of Asian immigrants as model minorities. In the play, the protagonist Max Lochran is seen speaking to his boss, Hatch, and both men are portrayed as equally prejudiced and misogynistic:

Lochran’s crass statements reveal a heavily self-justified tolerance that seems woefully inadequate and “based on a patronizing and begrudging acceptance of otherness” (Gilbert and Tompkins 289). In his statement, Lochran imagines his wife’s brother as a racial stereotype. Such derogatory comments highlight the racial double-bind that typically is experienced by immigrants. By suggesting that “they’re taking over,” Lochran seems to be justifying his hatred and distrust of others. By exclaiming that “they study harder in school, they work harder” (emphasis added), the character attempts to stereotype the immigrant as a “model minority,” a tactic often used by members of the dominant culture to essentialize or neutralize this particular group. As suggested by Karen Shimakawa, “the popular depiction of Asian Americans as ‘model minority’ illustrates the very contradictions that characterize abjection [. . .] Asian Americans were singled out for their aptitude for conforming to dominant models of ‘proper’ American citizenly values and practices” (13). Although the “model minority” is construed slightly different in Canada, the broad-based myth still persists in media and institutions of higher education. In 2010, an article published in Maclean’s magazine, originally titled “Too Asian?”, was criticized for perpetuating such stereotypes, claiming that Asian students were prone to “hard-working” behaviour, avoiding social life in order to succeed in school and beyond. In reaction to the article, scholars and writers contributed to the anthology, “Too Asian?” Racism, Privilege, and Post-Secondary Education.10 At first, the model minority myth seems harmless because it is presented as praise, but in actuality, it is used to scapegoat people and create foundations for fear and distancing. As such, the dialogue in lady in the red dress acts as a satirical prompt, questioning the validity of claims such as they work harder, or they study harder. Yee’s writing unpacks the “model minority” stereotype through a dialogic deconstruction of the roots of an assumed “fixity, as the sign of cultural/historical/racial difference in the discourse of colonialism” (Bhabha, qtd. in Shimakawa 15).

25 In another scene, Yee presents an interesting encounter between the primary protagonist, Max Lochran, and an equally important, secondary protagonist, Tommy Jade. Lochran is seen making his way through Chinatown, a cultural portal where he meets “Happy Chan, the one-man radio station” (Yee 44). Hearing his last name, Lochran assumes he knows the DJ’s cultural heritage. Lochran says: “Chan. Good, you’re Chinese—that’s good,” at which point Happy exclaims: “Bitch, I’m 1/5 Chinese, 1/7 Japanese, 3/8 Korean, 1/10 Filipino, 2/5 Taiwanese, 1/9 Laotian, 5/16 Mongolian and 3/4 Vietnamese. Chinese ... I’m the whole goddamn Pacific Rim” (44). The dialogue in this scene fractures the notion of a monolithic cultural heritage while “point[ing] away from that over-determined history and towards possibilities for self-definition and invention” (Verdecchia). Happy Chan’s response to Max’s simplified “you’re Chinese” seeks to remedy the homogenizing effects of labels thrust upon the Chinese or Asian cultures, writ large. It could be said that Happy Chan fulfills the role of an idealized postcolonial immigrant whose bold self-identification “provide[s] ways of reacting to the imperial hegemonies that continue to be manifest throughout the world” (Gilbert and Tompkins 13).

26 Stylistically, Yee’s play takes its inspiration from the film noir genre, often eschewing the traits of a typical well-made play in favour of a more episodic format that uses characterization and intercultural aesthetics in order to achieve its intended postcolonial critique. While much of the characterization attempts to portray the lives of actual immigrants living in the early twentieth century, the potential of suspended disbelief is often truncated by a self-reflexive and critical tone. In scene nineteen, for example, two characters are seen playing cards: Danny, the protagonist’s son, and Sylvia, otherwise known as the lady in the red dress. Danny says: “My half-and-half card. My Queen of Sparts. Half-and-half. Like me. Just like me” (Yee 84). Of course, Danny speaks of his dual heritage: his father, Lochran, is a Caucasian man and his mother comes from an Asian lineage. The intercultural aesthetics are further represented by the visual metaphor in the word “sparts,” which signifies both card suits: hearts and spades. This visual metaphor supports a post-Brechtian moment of learning about intercultural relations, particularly, the fear of miscegenation and “race-based” policies such as the Head Tax and Exclusion Act.

27 While lady in the red dress works within an episodic format highly influenced by cinema, the play’s complex relationship to realism should not be totally negated. As stated by Parie Leung, “lady in the red dress is fundamentally about family reconciliation, a core theme of classical realism” (174-5). Leung’s term “operative realism” expands upon the ideas of Richard Hornby, who believes that “no plays, however ‘realistic,’ reflect life directly; all plays, however ‘unrealistic,’ are semiological devices for categorizing and measuring life indirectly” (Hornby, qtd. in Leung 166). Indeed, the characters in the Yee’s play seem imbued with agency, able to move beyond their own perceptions and prejudices, while challenging stereotypical representation. Yee seems to be consciously, if not subliminally, aware of the importance of relating dates in the play to actual dates in Canada’s immigration history; by doing so, he grounds the dramatic material with undeniable facts and social injustices. Perhaps more ingeniously, Yee draws broad parallels to Western theatre culture by naming his characters—Happy, Biff, and Willy, respectively—after those found in Arthur Miller’s Pulitzer and Tony-Award winning play, Death of a Salesman. By bringing those iconic characters to life in a different context, giving them the surname of “Chan” instead of “Loman,” Yee reconfigures their worldview and dramatic purpose. In lady in the red dress, these three characters are related as father and two sons, similar to the filial relationship found in Miller’s play. Additionally, Yee’s characters are given relative importance as key mediators to the protagonist, Max Lochran, helping him in turn to discover his own family history. In many ways, this transformative gesture unfolds as a case of art imitating art. Changing the well-known characters in Miller’s play into Asian Canadian characters involves literary subversion and symbolic mimicry. On the one hand, Yee seems to be honouring the dramatic history and genres that contain his work, and, on the other hand, the gesture seems fully intent on challenging stereotypes or misunderstandings about Asian Canadians. By figuratively removing Happy, Biff, and Willy from their original Death of a Salesman setting, Yee uses a process of defamiliarization, exposing audiences to familiar characters, in name, but asking them to witness the lives of different yet equally worthy, estranged characters. Drawing parallels to Marty Chan’s use of an immigrant character as a hero-protagonist cannot be overstated in this regard; Yee’s writing, like his predecessors, offers glimpses into the trials, tribulations, and tragedies of the “common man.”

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 428 To be clear, lady in the red dress borrows from multiple genres, allowing the play to gravitate among the seemingly incompatible but mutually constitutive categories of “realistic” and “unrealistic.” It could be said that the intercultural style of the play, and its self-reflexive treatment of content, provokes audiences to consider the need for reconciliation through alternate perceptions and worldview. As stated by Leung:

As such, the characters found within lady in the red dress attempt to remember and honour the lived realities of early Chinese-Canadian immigrants, revisiting Canada’s social injustice through fictional worlds informed by multiple genres: operative realism, film noir, memory play, and family-based drama.

Postcolonial Discourse, Theatre, and Citizenship: Past-PresentFuture

29 The hegemonies that Gilbert and Tompkins describe can greatly impact immigrants living within Canada, and their influence has been addressed by a previous generation of Canadian writers of Chinese descent. Roy Miki has noted:

Other contributions in this vein include Denise Chong’s The Concubine’s Children: Portrait of a Family Divided (1995), Wayson Choy’s award-winning debut novel, Jade Peony (1995), and Judy Fong Bates’ family history in The Year of Finding Memory (2010). In some ways, the issues tackled by playwrights Yee and Chan—race-based policies, state-sanctioned discrimination against immigrants, exclusion and stereotypes—are not new, and yet their importance is heightened at a time of pro- and post-redress, when “there is the apparent gain in visibility for Asian Canadian literature, as it finds a niche in the broader transnational spheres of cultural representation” (Miki 273). Books such as those mentioned above have contributed to a flourishing body of postcolonial literature that engages with issues of social injustice, citizenship, border-crossing history, and the privileges accrued (or not) to immigrants depending on their country of birth and cultural heritage. And yet it is possible to imagine the works of playwrights achieving something decidedly complementary and unique to the movement towards reconciliation. For unlike postcolonial novels, poems, or non-fiction books, which are typically experienced alone and within the privacy of one’s home, away from the socio-political domain, play texts can exist as both literature and performance. The latter offers readers a unique vantage point as spectators and participants. Performance assumes that audiences convene in public spaces to share in affective moments over a particular duration. It is the public aspect of dramatic texts that separates it from literature; such as live setting and social context, quite arguably, intensifies the experience of text while bringing bodies together to listen, feel, and experience a shared event. The performances of immigrant-themed texts conflate moments of the past with the present through a conscientious, albeit fictional, recollection, and reenactment of historical discrimination. Chan’s The Forbidden Phoenix and Yee’s lady in the red dress contribute significantly to the public record and understanding of the need for reconciliation by operating within a “performance ecosystem” (Knowles 78).

30 As discussed earlier, The Forbidden Phoenix takes the form of a musical anchored by the heroic journey of protagonist Sun Wukong. By contrast, lady in the red dress operates in many realities, oscillating between film noir and family drama. Further, the function of both plays is inextricably bound with the movement towards reconciliation. Chan and Yee’s plays feature an immigrant-themed narrative that aligns closely with Ric Knowles’s notion of a “transformative, border-crossing, intercultural memory” (79). Arguably, such memory relies heavily upon an intercultural aesthetic grounded in postcolonial critique. Indeed, any performance of both plays requires a considered approach to casting actors of Caucasian, Asian, and “mixed” descent, inviting a nuanced characterization that attempts to recollect and reenact moments of social injustice and their legacies today. Staging of such historical, contemporary, embodied, or intercultural memories, then, becomes the foundational precursor for considering dialogue and reconciliatory efforts.

31 While the arrival of Chinese migration is often conflated and equated with the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad (CPR), settlements are traced back as early as the year 1788, when “Chinese carpenters and labourers encountered Nuu-chah-nulth peoples as they helped build a trading post led by Captain John Meares in Nootka Sound” (Yu “Refracting” 5). This historically documented earlier arrival provides a more nuanced perspective of Canadian history, and as noted by Henry Yu, “the fact that people of Chinese descent have been in British Columbia as long as have people of British descent is probably a curiosity at best” (5). Yu illuminates this point by suggesting that “an Atlantic-centred national history tends to give primacy to [. . .] particular colonies that turned into Ontario and Quebec” (6), resulting in a past which “favours some genealogies more than others, displacing First Nations peoples at the same time that it erases our Pacific Past” (“Refracting” 6).

32 Postcolonial theatre seems well positioned to react to this rather limited view of history by unveiling and challenging imperialism and historical erasure. Some one hundred and fifty years after anti-Chinese legislation was implemented in British Columbia, a number of artistic initiatives followed the spirit of Trudeau’s original multicultural policy of 1971 and the subsequent Royal Assent of the Multiculturalism Act in 1988.11 For example, the establishment of an Equity Office at the Canada Council in 1991 enabled theatre artists such as Marty Chan and David Yee to professionally develop and produce their postcolonial plays. The Equity Office was mandated to provide “a strategic focus on supporting Canadian artists of African, Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American or mixed racial heritage” as well as “policy development for official language minority communities” (“About”), arising at a time when postcolonial critique in Canada was gaining momentum. Surely, the plays of Chan and Yee are part of this ongoing and necessary discussion about postcolonial legacies in Canada. Andrew Dobson reminds us about the precursor to civic participation: “when it comes to political subjecthood, the Aristotelian criterion for recognition is the capacity for reasoned speech” (167). By unpacking the representation of immigrant characters in both The Forbidden Phoenix and lady in the red dress, this article has attempted to provoke a critical dialogue between unreasonable discrimination and reasoned speech.

33 This article has sought to answer two questions. First, what does postcolonial theatre have to say about Chinese immigration history? Second, and more specifically, how does the work of playwrights like Chan and Yee gesture towards reconciliation, unveiling the roots of discriminatory policies implemented during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? The representations in lady in the red dress and The Forbidden Phoenix can debunk and reimagine racial stereotypes through a dialogic function, recognizing that “audience members, too, are agents and actors [. . .] And a common view is that understanding between political actors requires either shared interests or a pre-existing social bond of some kind” (Dobson 98). In this case, the “pre-existing social bond” assumes a number of possible relationships: proximity to the cities and countries mentioned in the play texts; knowledge of the Canadian Pacific Railway; personal or familial experience with Canada’s immigration system; or the bond that simply results from experiencing the performances in a shared, public space. In closing, the plays of David Yee and Marty Chan have provided a voice for those who have been historically mistreated, racialized, or excluded from public affairs. What if Andrew Dobson’s claim that “listening out for previously unheard voices requires a particular sort of attention” (177) was seen in relation to Gayatri Spivak’s question, “Can the subaltern speak?”12 Surely, “immigrant” voices deserve to be seen widely and heard consistently onstage, for their rights and freedoms are bound up with the democratic principles that citizens and scholars have come to espouse in twenty-first century.13 If Chan and Yee’s plays have revealed what Canada’s history of discrimination may have been like, perhaps postcolonial theatre of the future will provide imaginative visions of what immigration and reconciliation may become— considering ways to improve relationships between, and for, Canada’s heterogeneous citizenry living in the twenty-first century and beyond.