Forum

George Luscombe Directing Chicago ’70 at Toronto Workshop Productions:

an insider’s subjective account

This article is a revised and expanded version of a talk prepared for The Art of Directing symposium, “Celebrating Peter Stein” at the University of Toronto, 7 June 2014. “Director as Documentarist / Director as Activist” was the topic of the panel in which I participated.

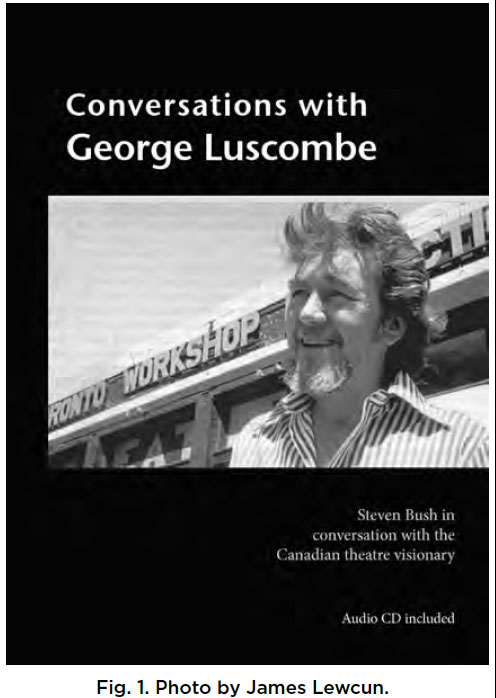

For this panel I talked about the creation of Chicago ’70 at Toronto Workshop Productions (aka: TWP), January to March 1970. This show was developed collaboratively by the ensemble with the direction of George Luscombe who, in many productions and especially this one, showed himself both a “documentarist” and an “activist.”

George’s importance in Toronto and in English Canadian theatre

1 Many readers already know a lot or a little bit about George. Here’s a brief backgrounder for those who might not.

2 The late theatre critic and artistic director Urjo Kareda called George “Our Father” (Bush 191). Why? Because George was on the scene first, developing new work from 1959 when the very few professional productions in Toronto were touring shows from elsewhere, reliable classics, and recent Broadway or West End hits. TWP was in operation some ten years before important companies like Factory, Passe Muraille, Tarragon, and Toronto Free appeared. Theatre-makers in other parts of Canada would acknowledge George’s influence. Besides Chicago ’70 his many innovating productions include Hey Rube!, The Mechanic, Che Guevara, Mr Bones, The Good Soldier Schweik, The Mac Paps, Olympics ’76, and of course Ten Lost Years.

3 George was committed to original creation, to new looks at old plays, to strong political content and to building a fulltime paid ensemble of actors who would train as well as perform together.

4 In her review of our book Conversations with George Luscombe: Steven Bush in conversation with the Canadian theatre visionary, veteran theatre practitioner Lib Spry wrote: “I was surprised to discover in these conversations that Luscombe was a fervent believer in Stanislavski. The shows I saw did not have anything in them that I then associated with Stanislavski—they were physical, lively, fun, thought-provoking and even in the most emotional of moments, it was the audience whose guts were being wrung, rather than the actor’s.” Indeed the eclectic mix that was George’s theatre included influences from Joan Littlewood’s understanding of Brecht & Epic Theatre; Rudolf von Laban’s “Efforts”; British Music Hall; Circus; Mime; Commedia; Chinese Opera; and Vakhtangov. And yet his foundation was always Stanislavski.

TWP and me

5 My role in the Chicago ’70 project—along with everybody else in the ensemble—was as Actor/ Researcher/Co-Creator. But I also functioned as informal Dramaturge. My tasks included (in close collaboration with George) editing transcripts, organizing units of dramatic material into a playable sequence, and (with fellow actor Mel Dixon) putting our work-script into readable form.

6 This was the last of the five shows I did as an actor with George and this was the project on which I worked most closely with him until, over a quarterof-a-century later, we recorded the conversations that eventually became our book.

The Activism of the Director

7 George had East Toronto working-class roots. He was an activist who “was on picket lines at 16” (Luscombe, qtd. in Bush 163). He remained on the side of Labour and the Left to the end of his days—though sometimes very critically. And he had five formative years acting with Joan Littlewood and Ewan MacColl at their politically committed Theatre Workshop in London. He was also the first director in Toronto—to my knowledge—to actively practice “colour-blind casting.”

8 George once said: “I don’t train actors. I train citizens” (qtd. in Bush ix).

The Activism of Chicago ’70’s Ensemble-of-the-Moment

9 Who were we? We were actors of diverse experience, training, and cultural backgrounds and most shared George’s artistic values as well as the desire to put our politics onstage. About half of us were Canadian-born and about half were immigrants—from Jamaica, Ireland, Australia, and war resisters/ dissidents from the United States. Most also had various histories of various activisms.

Some Political Background: The War, the Demo, the Trial

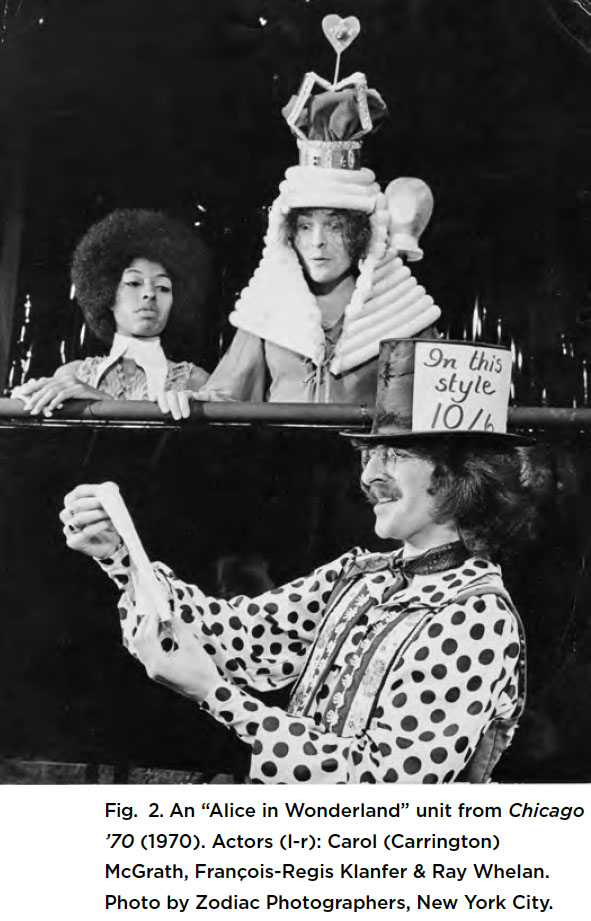

10 Once upon a time there was a war in Vietnam. As the carnage wore on and on, more and more people around the world objected to it. In August 1968 several thousand US citizens gathered in Chicago to protest the war policies of the Democratic Party that was convening to decide on its next Presidential candidate. Violence broke out. Police said the protestors started it, the protestors blamed the police and one investigator described the events as a “police riot” (Carson 107). Many demonstrators were injured and many were jailed. After Richard Nixon became President, charges of conspiracy “to incite riot” (Sadock and Okpaku 135) were laid against eight men affiliated with the Youth International Party (YIP) and other organizations. Their trial began 26 September 1969, continued until 20 February 1970 and became known as “the Trial of the Chicago 8” (9) or “The Chicago Conspiracy Trial” (Bush 52, 152).

11 Outside a judicial context, “to conspire” means, literally, “to breathe together” (Markson 1971).

The Process: Building a Play from Documents

12 A stalwart contributor to many TWP projects, Jack Boschulte returned to his hometown of Chicago at the time of the trial. He began sending us articles about the event, along with transcripts and his own observations from sitting in the courtroom.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 213 At TWP we were, in fact, already rehearsing another play. But then we started getting these dispatches from Jack. The play we were rehearsing kept failing to ignite us, but the news and the verbatim excerpts from the trial did. The testimony of poet Allen Ginsberg, Yippies Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, militant activist Linda Morse, Mayor Richard Daley, and others really got us going. The irreverent behaviour and imaginative wit of the defendants and their lawyers struck a chord. In the trial judge, we found a perfect villain: harsh, partisan, smirking, very smart and possessed himself of a wry sarcastic wit.

14 The actors’ impromptu reading of an article from an “underground paper” really excited George: “It was a satire of the court system, which I felt was not only American, but applied to the courts probably in all the world—certainly in this country” (qtd. in Bush 52). All of us loved the radically different personalities involved and the way the trial gave focus to “the most pressing issues of the day.” We soon stopped rehearsing the other play and charged fullspeed into making a theatre-piece grounded in the trial documents.

15 There seemed to be consensus that our political views should be onstage without apology and that the performance should be a strongly physicalized entertainment. What we didn’t have consensus on—yet—was the ‘How.’ In his excellent book Harlequin in Hogtown: George Luscombe and Toronto Workshop Productions, Neil Carson writes:

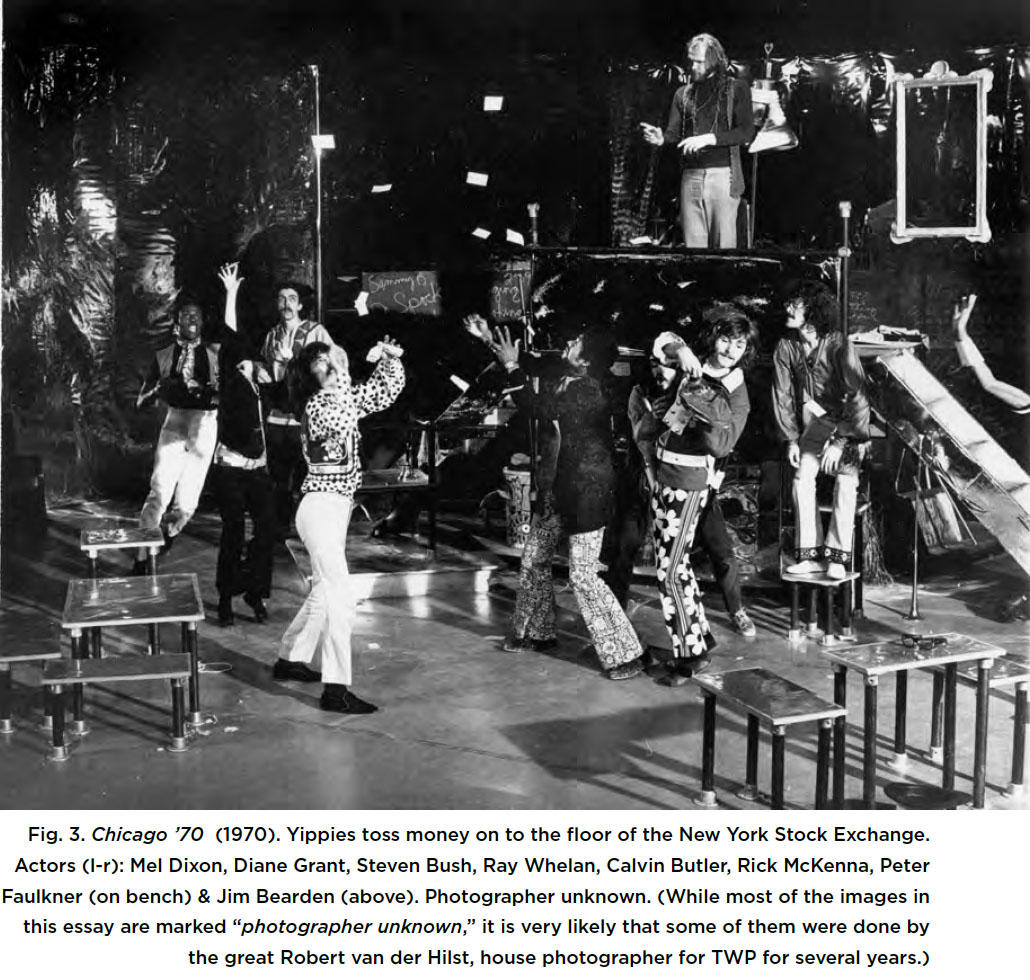

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 316 Memories differ considerably about how the creative process actually got jump-started. For example, Jim Bearden, who was a major contributor, wrote to me:

Here’s how George recalls an instance—the same or another?—when he abandoned the stage to the actors:

Ensemble, Autonomy, and Improvisation

17 However exactly we arrived at that point, we were finally free to contribute—indeed encouraged to contribute—with improvisations (spontaneous or “planned”), with staging images and impulses, with new lyrics for old pop songs.

18 Of course, having some six weeks’ research and development time helped. As most readers may know, rehearsal periods of this length are almost unheard-of in English Canadian theatre today, except for those few wonderful and adamant mavericks like Theatre SmithGilmour who insist upon them.

19 Chicago ’70 was built, primarily, from courtroom transcripts. It was, in this respect, what many now call “verbatim theatre.” (Nobody I knew employed that term at that time.) While the transcripts themselves were sometimes brilliantly theatrical, we wanted to extend the theatricality, not sit on it. So we began incorporating non-documentary sources—most notably from that “Absurd” trial scene in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, from other writers whose works seemed relevant (e.g., Fernando Arrabal, Marge Piercy, James Thurber) and from politically awake Rock’n Roll.

20 And also this particular ensemble was touched by Yippie-inspired anarchism and had a taste for the wild and crazy. Out of respect for academic rigour, I am obliged to mention the influence of marijuana (and other illegal substances that altered consciousness) on a great deal of theatre in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Certainly, as Jim Bearden reminded me, this was true with Chicago ’70. Which is not to say that the actors were stoned in performance. (I can verify no more than one instance when that occurred—and that was essentially accidental, or the result of bad timing!) What I am calling attention to is a ‘stoned’ perspective on life, art and theatrical possibility that many in the ensemble shared. And this came into play throughout the creation and rehearsal phases.

21 (Disclaimer: None of the above should be construed as advice to young academics or theatre-makers that use of cannabis is some surefire guarantee of artistic success!)

22 I must also mention that George believed deeply that theatre—even serious-minded political theatre!—should be “fun.” Even though he could be terrifically stern, nobody loved a good well-earned laugh—one that was in keeping with the Through-Line of Action—any more than George.

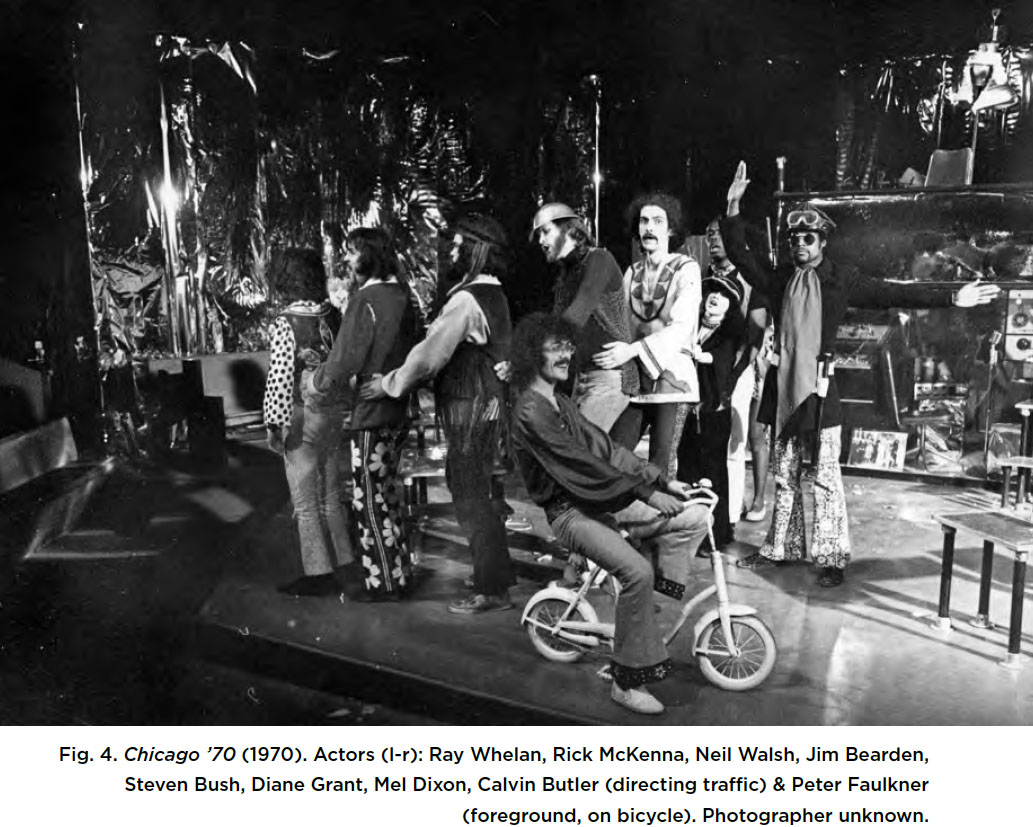

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 423 George was genuinely committed to the autonomy of the actor. He would never tell an actor what to do. Choice of Objectives was the domain of the actor, not the director. He would never dictate a “result”; he believed that crushed creativity and made the actor dependent. And in George’s theatre there was never any “blocking.”

24 “What? No blocking? How can that be?!!!” (While I have come to agree totally with George about this, I confess that in my first show with him, I was often, and very painfully, “lost in space.”)

25 About an earlier TWP production George recalled: “A woman said to us: ‘My goodness, who’s your choreographer? Those actors move so well!’ ‘There’s no choreographer, because we don’t ‘block.’’ But the actors had been working for months on [Laban’s] Efforts” (qtd. in Bush 63).

26 George’s sense of ensemble was not limited to actors: Lighting was improvised too! There were no cue-to-cue (Q2Q) technical rehearsals. As George explained: “Not only did we not have lighting plots, but we didn’t have a lighting rehearsal.” Why not? Because the actors “have to stand around being lit [. . .] and hating the play, defeating the purpose [. . .] because you’re only a moment from opening night and you kill the play!” (qtd. in Bush 57). And this “house practice” of no Q 2 Qs held on. At least as long as the virtuosic John Faulkner was lighting TWP shows. Which was the case with the five I acted in. For Chicago ’70 John was at every rehearsal and knew the emerging show as fully as George did.

27 The Resident Designer Nancy Jowsey was also very much a part of the ensemble —not a jobbed-in “outsider”—and her workroom was right next to the stage. She was there most days and so knew everything that was going on in rehearsal. She remained a close collaborator with George for several seasons.

*

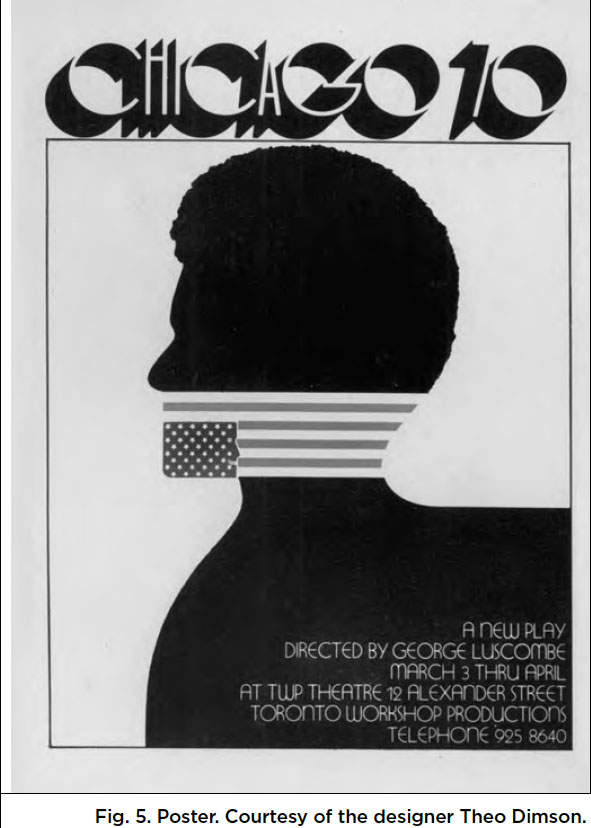

28 Improvisation and Laban’s Efforts sometimes led to scenes having double or layered meanings. An example: During the trial, defendant and Black Panther Party cofounder Bobby Seale was bound to a chair and gagged by order of the judge. In Chicago ’70 this played out in slow-motion mime as the massacre of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai was described. “So,” George noted, “it became—it meant—both things…” (qtd. in Bush 152). And the great Theo Dimson carried forward more than one meaning into his brilliant poster for the show.

29 George’s commitment to autonomy was, I now believe, a political as much as an artistic principle. And without this fundamental respect for the actor—and indeed for everybody who contributed to the show— Chicago ’70 would have been a much more conventional stage-piece. Coupled with a practical theatre man’s understanding that “twelve brains on the stage are better than one” (Luscombe, qtd. inBush 161), this respect was a big part of George’s genius as a director.

30 Years later, as George and I talked about directors who are over-prescriptive with actors, he said: “The director mustn’t be frightened of taking time to allow the actors to discover their truth” (qtd. in Bush 103).

31 With Chicago ’70 George actually “took the time” and even displayed some surprisingly “anarchist” tendencies. Or so it seems to me now. He opened up the theatre for many of us. He, Nancy and John definitely gave a cohesive aesthetic to the rampant and often chaotic creativity of the actors. And, in the process, I believe that we may have opened some doors for him.

The Product

32 Chicago ’70 still stands, in my experience, as a (mostly) successful example of collaborative/collective process and as a model for making engaging theatre from documentation of real events. It was an ultimately productive creative meeting between “generations,” between a director (age forty-three to forty-four) self-described as a terrible disciplinarian (Bush 2)—and much more harshly described by some who worked with him—and a group of actors (age-range nineteen to thirty-five), many of whom identified with the loosely anarchist politics of the Yippies—two of whom were, even as we were developing the play, on trial for “breathing together.”

33 This was at a time, as some readers will remember, when a (partly media-fed) “generation gap” was at its height and the tensions between Old Left and New Left, between Socialism and Anarchism and Liberal Democracy were being lived-out in the anti-war movement and in our personal lives, often resulting in huge conflicts and schisms.

34 And the Chicago ’70 process was not immune. It was not always “fun.” Indeed there were bitter collisions, a mini-rebellion and subsequent suppression, and a near-walkout over an actor being fired. Nonetheless, with all this struggle, we managed to collaborate and for a brief several months the ensemble did, at times, “breathe together.”

*

35 Chicago ’70 was theatre as quick-response “Living Newspaper”: As the event was still happening—and making news internationally—we researched, created, rehearsed and then performed a whimsical and dynamic theatrical spectacle that provided verbatim content with context and interpretation. The sentences were given out to the defendants less than three weeks before we opened (Sadock and Okpaku 136).

36 Though not all reviewers loved the show, by the standards of English Canadian theatre in that era it had a long run: two months at TWP (10 March-9 May 1970); plus four weeks at the Martinique Theatre in New York City; a week at the International Festival of Theatre Arts in Wolfeville, Nova Scotia; and another week at St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts (now the Bluma Appel Theatre, part of Canadian Stage) (Carson 211-12).

37 Thus, ironically, this energetic “circus” overtly espousing radical politics became one of the most commercially successful TWP shows up until that time.

38 At a moment when few, if any, in English Canada were taking on similar missions, Chicago ’70 was a “living newspaper” and also a “living editorial.”