Forum: Link & Pin

“I Haven’t Got Time for the Pain”:

The State and Stakes of Performance Art 2.0

REPERFORMANCE

1 The last decade has seen a resurgence of interest in the not-so-new practice of “reperformance,”1 the act of re-enacting or re-staging apparently previously performed works. LINK & PIN wondered… why? Why reperform—or (re)perform? What are the disciplinary, ethical, authorial, contextual, and temporal dilemmas one faces in the process of reperforming? LINK & PIN’s third event took place on 8–9 February 2014.

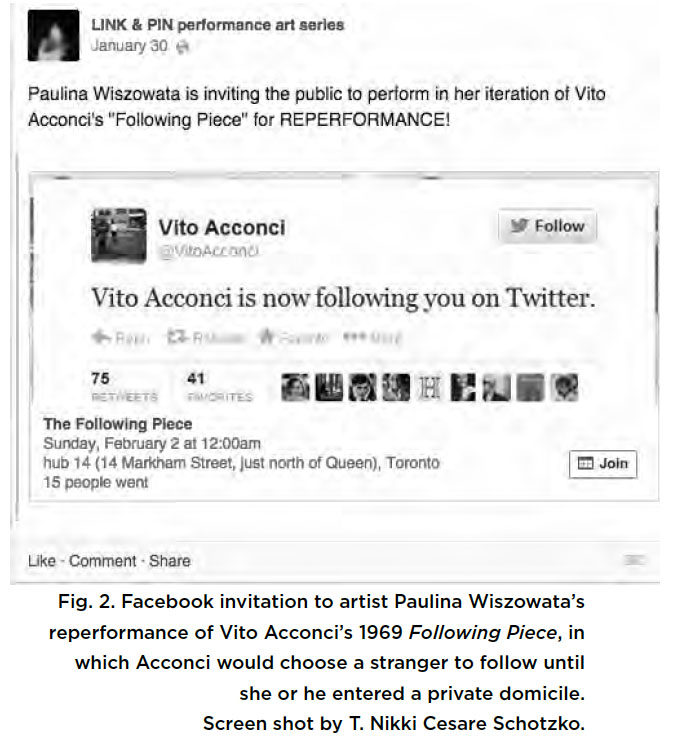

- Presenting Artists:

- SHANNON COCHRANE with

- FRANCESCO GAGLIARDI and MARCIN KEDZIOR

- LEE HENDERSON and BEE PALLOMINA

- HOLY JACKAL (hollyt and Jack Bride)

- JULIE LASSONDE

- BRIANNA MACLELLAN

- VICTORIA STANTON

- PAULINA WISZOWATA

- Writer: T. NIKKI CESARE SCHOTZKO

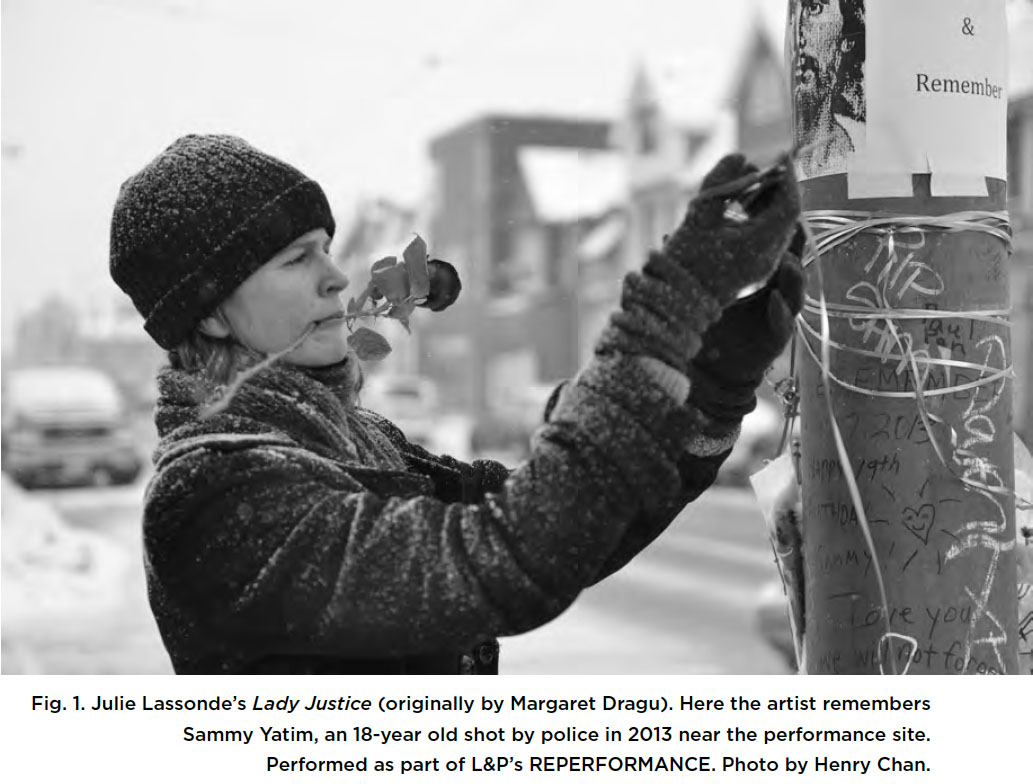

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1“I Haven’t Got Time for the Pain”: The State and Stakes of Performance Art 2.0

I’ve got a surprise for you. Last night at the bar you asked me… what performance art was; I answered it was pure presence, in real time, without artifice… taking necessary risks. And I wonder how one can take risks in front of a video camera. /

Well, I’ve got a real gun. /

And it’s loaded.

[Screen goes black.]

—Guillermo Gómez-Peña, A muerte (Segundo duelo; performance)

2 When Carrie Lambert-Beatty says she “want[s] to believe” in her 2010 Artforum review “Against Performance Art,” she is saying that she wants to believe that art might offer an efficacious alternative to political rhetoric, that “what the world of politics won’t give us, the art world will.” She wants to believe that Marina Abramović’s durational performance The Artist is Present, concurrent with the simultaneously (re)performed and embodied (and samenamed) exhibition of the archive of her four-plus-decade long career, might make clear that performance art can be both cognizant of itself as a “spectacle and personality cult” and (still) afford an authentic and intersubjective exchange between performance and audience; and that, though Abramović is the only “Artist” invoked in the performance-retrospective’s title, the role itself will not be inhibited by such iconic singularity. Lambert-Beatty, though, has some doubts (208).2

3 For Lambert-Beatty, the anxiety-ridden debate that erupted in 2005 over Abramović’s Seven Easy Pieces3 is no longer so concerned with the now-anachronistic matter of liveness. In the intervening years, the ensuing conversation has become less about performance’s ontology than about its temporality:

4 Performance, across disciplinary and historical categorizations, is in itself predicated upon a certain conceptual and even structural overlap: a temporal stutter that allows for the possibility of many nows within new possibilities of the encounter between performance and its widely strewn audiences. “To disappear into memory is the first step to remain in the present,” as André Lepecki writes (127). But who or what is it that disappears?

5 The “new” in work that is reconstructed, re-invoked, and re-enacted, that is, work that falls under the rubric of “(re)performance,” may be “new” only within the facet of immediate spectatorial engagement; encumbered by history, imagination, and memory, any ongoing conceptualization of such performance is necessarily burdened by the prefix, the “re-,” the already-imagined-not-quite-newness-at-all. But any work at all, no matter how original and no matter how compelling it may seem, is always already and always ever burdened by the prefix of that which has come before. Or, as Susan Sontag wrote in 1969, “Whatever the artist does is in (usually conscious) alignment with something else already done, producing a compulsion to be continually checking his situation, his own stance against those of his predecessors and contemporaries” (15). It is almost as if the (performance) artist must keep glancing over her shoulder—a twitchy, Vito Acconci-like gesture.4 Careful, you never know who might be following you.

6 Trapped somewhere in this uncomfortable in-between of the stutter (through time) and the twitch (through memory), performance art in the twenty-first century, or at least the scholarship and criticism that accumulates around it, has moved beyond the art form’s material and theoretical conditions—has moved beyond, according to Lambert-Beatty, even the concern about whether it is an art form or not (209). Yet as it navigates a relatively recent entry into mainstream and institutional consciousness, accruing both street cred through its sidling up to the likes of Jay Z and Lady Gaga (and James Franco) as well as university credits as it increasingly becomes part of theatre and performance studies curricula in both studio and survey courses, performance art is entering uncharted if not also dangerous territory. The risks of what I am considering here to comprise “performance art 2.0”—an iteration of the genre caught between a history of marginalized spaces and a present of mainstream consciousness—are not as entwined with notions of presence in the moment of performance’s enactment as they are in a sense of authorship and authority enacted by the performer in that moment. Moving beyond the concern of representation, and therefore a concern with whether or not what is performed is “real”—and thus also moving beyond a consideration of what the consequences, or stakes, might be in such “realness” for audience and performer alike—performance art 2.0 instead asks what it means to be “authentic.”

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 27 I was thinking about this, and about what we talk about now when we talk about performance art, as I entered, late, to Victoria Stanton’s Sharpshooter (top five hits: 3.33 RPH version) as part of LINK & PIN’s Sunday Series—this installment engaging “reperformance.” I walked into the raw space of hub14, filled with people sitting silently and reverently on the bare floor around an unassuming yet unquestionably present woman—“present” as in there then, but also still there now, disappearing into memory—sitting in a simple metal chair in front of them. Carly Simon’s 1974 hit “I Haven’t Got Time for the Pain” was in mid-play. The song shifted, from Simon to Danielson Famile (“The Wheel-Made Man,” 2001); to Erik Satie (Gymnopédie No. 1, 1888); the Beatles (“Here Comes the Sun,” 1969); something about an alligator (David Bowie, “Moonage Daydream,” 1971); and back to Carly. As I watched Stanton over the three hours that the performance lasted, it almost felt like I was watching her age.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3Stanton describes the sound track for Sharpshooter as the sound track of her life:

We were experiencing Stanton age—as in experiencing an age or to be of an age; as in experiencing her (and ourselves) age. It was an aging that moved us back in time through Stanton’s life, but an aging that moved us forward as well—toward and through the ongoing-ness of time that accompanies, in its own strange counterpoint, any durational performance.

8 I was late to Stanton’s performance because I had stayed too long at the University of Toronto’s annual Festival of Original Theatre conference, where vomit-artist Millie Brown was talking about having puked energetically onto a blank canvas on the stage of the Robert Gill Theatre the night before. (It was an exceptionally good weekend in Toronto for performance art.) I felt like an interloper to the hushed and intimate atmosphere of Stanton’s performance, my own lack of time in uncomfortable juxtaposition to this meditation on time she was offering. As Stanton leaned forward over her crossed legs on that uncomfortable chair, her forehead meeting her knee, and began to sob, I wondered, with concern but also with curiosity, what it was about these songs that made her so very sad. (And because, ultimately, we can’t seem to help but make every performance about ourselves, I wondered, too, What would be on my own playlist?)

9 What, or where, was the (re)performance, exactly, in Stanton’s work? The looping of the songs as metaphor for the looping of events and sentiments in her own life? The reenactment of a prior version of Sharpshooter? (Certainly not just that.) The resonance of these songs, with which I had a passing familiarity, from our lives through Stanton’s—or vice versa? The re in this “(re)performance” was properly parenthetical—subtle though essential, challenging but deliberately, or at least it seemed, undefined as to its origin. I haven’t got time for the pain… Stanton’s performance was in fact making time for the pain, and as she began to sing along to Carly’s last iteration, I thought, Shouldn’t we sing, too? It felt wrong—dare I say, it felt inauthentic—not to, so I hummed along quietly, to myself.

10 In 1993, Peggy Phelan wrote against representation in performance, arguing that it “functions to make gender, and sexual difference more generally, secure and securely singular [. . .]. The common desire to look to representation to confirm one’s reality is never satisfied; for representation cannot reproduce the Real” (172). Similarly, Gilles Deleuze writes that representation:

11 Repetition, however, as he notes:

12 Representation marks the object as always already in the past, alluding to something defined through its unattainability. Repetition, however, is about the moment of allusion. It refers, it suggests, it might re-present (it might even re-perform), but it remains within the present and looks toward the future, even as it recalls and recollects the past.

13 Brianna MacLellan’s reconstruction of Judy Radul’s 25 Entrances and Exits from 1998 traipsed lightly along the more playful lines of repetition and representation. Radul’s original, or at least the documentation that exists of it, involves only one score, one photograph, and one statement: “Changing the composition of a room by entering and exiting.” This singular gesture both stands in for and creates an illusion of (or allusion to) the other, missing twentyfour entrances and exits, which MacLellan then realized in her performative reenactmentas-invention. MacLellan, as I quickly jotted down during the performance, “spun awkwardly into the room,” walked as if “on the catwalk,” “crawled/slid” across the floor, and executed an “‘I was here’ shuffle.”

14 At one point, near the end of her 25 Entrances and Exits, MacLellan walked over to a man sitting in the audience and knelt before him. He took her hand and placed it, gently over his heart. Thank you, one of them whispered.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 415 MacLellan took “giant steps,” she “ran away,” she “fell,” and she, at last, stood. She was not standing in for something else; she may have been standing for something there.

16 Regarding her 2005 (re)performance of VALIE EXPORT’s Action Pants: Genital Panic (c.1969), which Abramović based not on EXPORT’s performance per se but rather on a photograph somewhat tangentially related to it, Abramović commented:

Maybe it is better, too, to “create an image” when trying to talk about performance art; even, perhaps, when trying to write about it. By refusing to ascribe a narrative to the performances we encounter, we might refuse, too, the preposition upon which meaning hinges. That is, we might—just—talk, or write, unburdened by the necessity of legitimating—as in to authorize, as in to render legitimate, to render genuine or real (OED)—what it is we are talking or writing about. What do we talk (about), now then, when we talk (about) performance art?

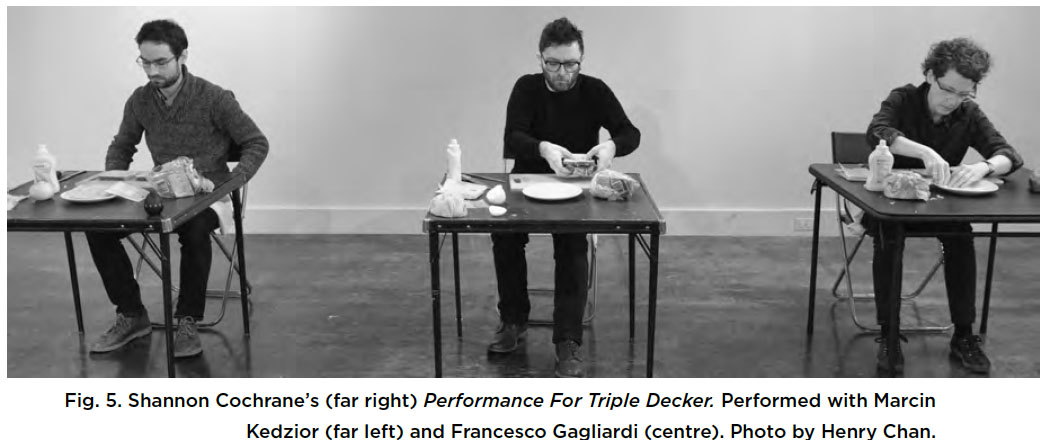

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 517 I am left with an unexpected nostalgia for the smell of deli meat.

18 Shannon Cochrane, with Marcin Kedzior and Franceso Gagliardi, each made and unmade individual sandwiches from sliced whole-wheat sandwich bread, yellow mustard, deli ham, American cheese, iceberg lettuce, and red tomato. The performance, whose duration I remain as unsure of now as I was at hub14 (somewhere between fifteen and forty-five minutes, but I honestly could not tell), consisted of three basic acts: set egg timer; assemble ingredients in order listed above; disassemble ingredients in reverse order. Repeat.

19 The deli meat was unnaturally shiny. This was one of the details that stood out to me as I watched Cochrane, Kedzior, and Gagliardi perform these most banal of actions, with the most ordinary of materials, while seated at three smallish, portable tables. I became fascinated, became consumed by these objects of mundane consumption: by the intricacy with which Cochrane reconstructed the tomato—stem intact, sticker realigned—with each remaking; by the general deconstruction of the processed cheese in Kadzior’s sandwich, which put into question the stability expected of any material at all; by the fascistic nature of the egg timer. And, of course, by the smell, which was in equal measure evocative and revolting. The performance—like Stanton’s, confounding the (re) of it and beautifully so—was sublime.

20 Deleuze writes, “If exchange is the criterion of generality, theft and gift are those of repetition” (1). “Theft and gift,” then, might be the terms by which to consider the notion not only of (re)performance in its act of repetition, but also performance in general. Performance “saves nothing; it only spends,” as Phelan writes, and in doing so, it “clogs the smooth machinery of reproductive representation necessary to the circulation of capital” (148). It spends, but, like the gift of which Jacques Derrida, too, writes, it also “gives, demands, and takes time” (41). It takes time, it makes time, it’s got time, it seems, for the pain.