Forum: Link & Pin

Perception is Participation

PARTICIPATION

1 LINK & PIN’s second performance event, PARTICIPATION, took place on 15 December 2013 and was interested in pushing the boundaries of what participatory performance might usually look like. The event hoped to question notions of transformation, transmission, violation, boundaries, negotiation, exploitation, and labour in relation to participatory performance.

Or, is the more apt question: What isn’t “participation”?

- Presenting Artists: ANDRÉA DE KEIJZEREMMA WALTRAUD HOWESMICHELLE LACOMBEDARREN O’DONNELL

- Writers:NIOMI ANNA CHERNEYKAREN ELAINE SPENCER

- Baker Artist:NATALIE BOUSTEAD

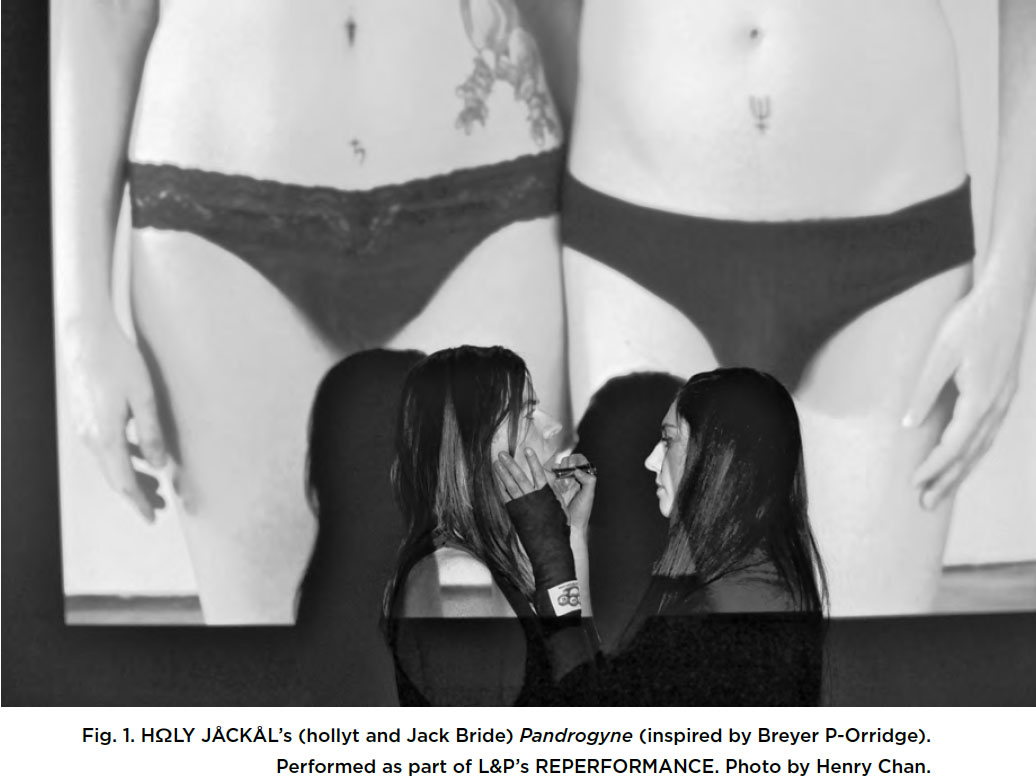

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Perception Is Participation

2 This is an essay about vulnerability. This is a vulnerable essay. This is a piece of writing that is tied to a particular event, though arbitrarily so because it is me—my voice, my words, my perspective—that does so: this writing could be a record of anything. I could tether my memory, and by extension the written record of this memory, to any event that I could think of. In this essay I want to describe the experience of performance in terms of empathy and sympathy but I might not get there. I have not watched that TedTalk that went viral by scholar Brené Brown on the subject, but I hear it is good.

Participation

3 The first thing to notice about participating is that we are always doing it. In the deepest layer of how we are towards the world, being-with-others conditions the ground of all possible appearances of a self-contained and autonomous moving body. On the level of motor development, it can be helpful to make this point by drawing on an example of an infant acquiring or learning movement. This phenomenon is often described as “imitation”: the baby copies the movements of adults or older children, repeating them in their1 own body. First, I’ll just say a few things about why this is a superficial understanding of how movement habits are acquired throughout the process of development. After I’ve finished that, I will draw out the ways in which this example of motor learning can help us think about participation in general, and participation in performance work more specifically. Then I will go on to talk a little bit about the issue of vulnerability specifically in the LINK & PIN performance event, PARTICIPATION.

4 I’ll borrow an example from French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, because he is the person I go to for all my examples. He writes about this in the Phenomenology of Perception briefly, but more extensively in his lectures on child psychology and pedagogy and also in an essay called “The Child’s Relation With Others.” He describes an infant “copying” an adult’s action of biting. The adult playfully gnaws on the baby’s fingers: when the infant feels this, they too perform a similar movement. To say that this is imitation, however, misses the point. The infant experiences their body as already bound up with that of their parent. They don’t understand themselves as autonomously generating movement patterns, and thus open to the possibility of “copying” actions performed by others. Merleau-Ponty’s assertion here is precisely that you cannot understand this example of the baby’s movement by assuming that the child has lined up comparable parts of their body with that of the adult, and then mobilized their possibilities for action as a consequence of their likeness. The baby has hardly at this point seen their face in the mirror, nor does the baby necessarily have the sense that their teeth resemble the adult’s teeth. When the infant feels their fingers being bitten, senses the adult’s biting action, they too perform this action. The first appearance of movement patterns is possible only because their nascent movement development, as infants, takes up the movements of the adult as already internally related in the baby’s perceptual system. Though in early development we already have the motor capacity to perform this action of biting (in fact, in early infancy babies primarily experience the possibilities of their worlds through one of few available actions to them, that of opening and closing their mouths), it is only through the joint structure of the bodies of infant and adult, that this movement shows up as having a kind of determinacy. When infants go to imitate an action perceived in the bodies of adults—for instance by biting—they are in fact taking up a solicitation or an invitation for a way of moving in the world that belongs already to the sphere of their bodily possibilities.

5 What I have unpacked above, via Merleau-Ponty, is useful insofar as we are making note of the basic structure of intersubjectivity. Intersubjectivity is our most fundamental way of accessing the world through bodily movement and action. Making sense of our own movement and action is possible only in the context of a primordial belonging together with the bodies of others, which opens us onto a world of shared meaning. This is important in the context of performance work because it is not from autonomous, separate, or self-contained centres of bodily action (i.e. “selves”) that we experience the actions of others in a performance context. In the most profound way, the bodies and movements of other people shape our discovery of movement and action, uncover to us ways of making meaning that resonate in layers of selfhood.

6 Maybe it’s enough to just say that perception is participation.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

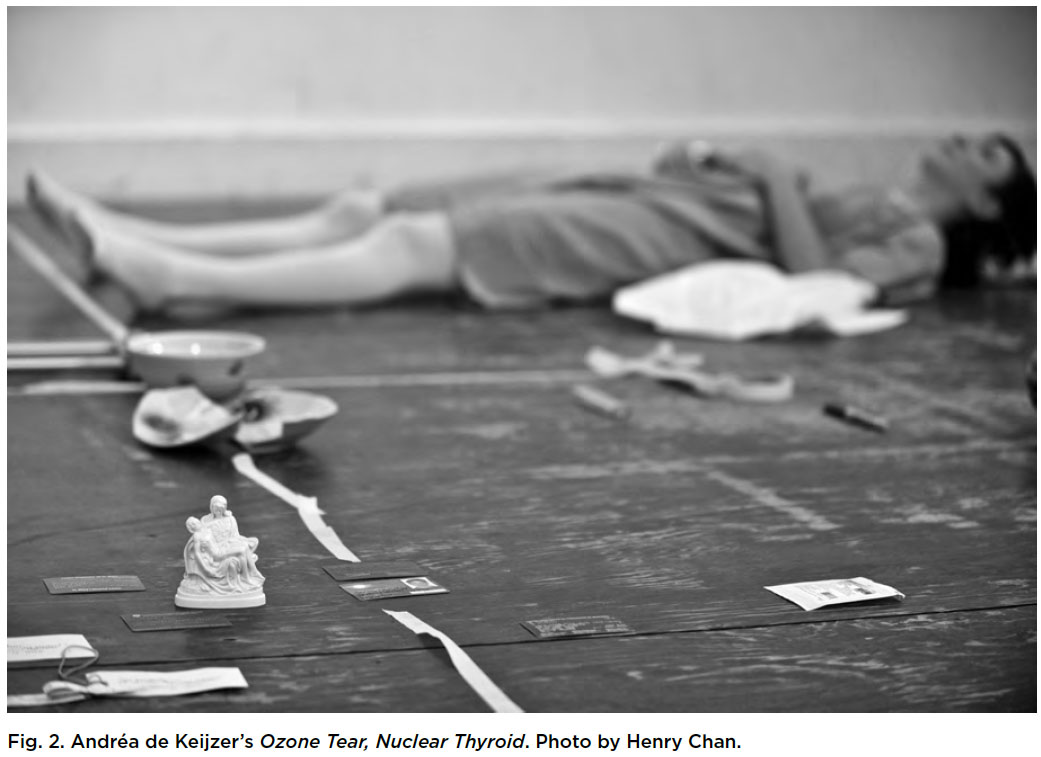

Display large image of Figure 37 In Andréa de Keijzer’s work, Ozone Tear/Nuclear Thyroid, the currency of the participation rests on her recalling, in part through ritual act and speech, her body’s experience of surgery, illness, and healing. Participation is about exchange. It’s about a trade between your body and the world. In moving through the world, we are always enacting this exchange called “participation.” We move in order to perceive, and also perceive by way of moving. Thus we can say that perception, too, is an exchange. Experience necessarily tosses us forward into the world while at the same time demands that the world find its counterpart in our bodies. Andréa’s work is hard for me to write about. She is a treasured friend, one with whom I have spent many hours, both in and out of the studio. I feel her movement and action resonate in my body, much like the way the infant activates a circuit of movement that already ties its nascent development to that of its caregiver. Though her performance calls for participation in the form of remembering and giving voice to the experiences her body has undergone, for me it is as if she is telling me the story of my own body’s trauma. Though it is Andréa’s body that is “staged” in the performance as vulnerable, it is through an exchange of perception as I receive this work, that my corporeality opens onto its own fragility.

8 I cannot write about any of the other work in the PARTICIPATION edition of LINK & PIN in the same way I can write about Andréa’s.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 49 The basic point to make: if one must perceive in order to participate, and one by virtue of the other calls for an exchange, then performance will always call forth a kind of recognition of my own corporeal vulnerability. All of the artists showing work in this event play with this to varying degree. Darren O’Donnell’s piece—in which we all pass around a cell phone and speak with him—brings the audience members into relief against each other. We are both perceiving the work and being perceived as part of it. Standing against the walls of the square room housing the performance space, we pass the phone between us. The soundscape is full of nervous giggles and the hunger of anticipation as we each wait our turn for the phone. When I get passed the phone (or maybe I volunteer to go next, I can’t remember), O’Donnell asks if I’m an artist. I answer “yes” and I recognize the audible yes’s and no’s that have so far been uttered in response to this question. When I pass the phone off to someone else, the piece now has the glimmer of understanding. I’m in on the joke.

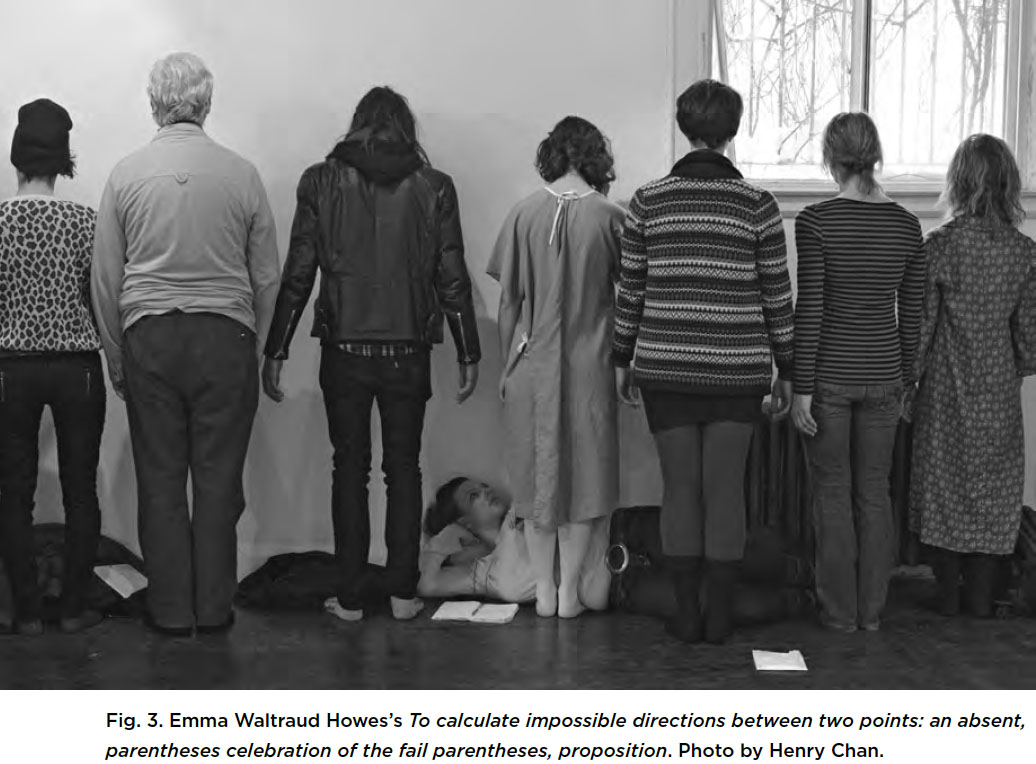

10 Similarly, Emma Waltraud Howes’s piece calls for us to act together: to carry out a set of instructions to the soundtrack of her recorded voice, which plays from the speakers in the performance space. The sound comes from the stereo located next to the sink and kitchen, the bathroom door just visible to the right. When Howes’s voice comes through the speakers, I turn and look but don’t move. I do not follow the instructions, but instead lie on the floor. I can’t remember how people move around the room. I close my eyes, lay still, letting her voice wash the room in sound as I feel the cool hardness of the floor cradling my back. The piece culminates with a line of audience members walking together from west to east across the square space of hub14. I lie on my side, head propped on my elbow and feel the force of their action as they move towards me; become sensitive to their moving mass advancing on the stillness of my body. I am once more dropped into the fragility of my body. I regret having chosen not to move with the collective mass.

11 Michelle Lacombe’s work is private. If Andréa’s piece functions through recounting, through memory and ritual, Michelle’s seems to recount nothing. I participate by virtue of perception, but these exchanges yield no direction. My memory is filled by vignettes and images. It is the freeze frame of moments making up a trajectory, rather than the condensation of motion into the narrative of movement. Lacombe’s piece is a pure vehicle on which the immediacy of perception, as participation, travels. We watch her remove her clothing, untie her boots, take off her underwear, and re-dress—a silhouette of her body curved and bent as she finishes the act of relacing. We wait. The piece is full of waiting. Each moment is pregnant with its own energy rather than gathering together a cohesion of what has come before. She fills a glass of water in the bathroom. We cannot see inside the bathroom but hear the sound of running water. She drinks the glass. We wait again. The room is bare save only for the sound of water running followed by the thirsty sound of drinking. I can’t remember whether we saw her drink the glass of water or whether I only felt and heard the action so deeply I imagined that I also saw it.

12 Andréa’s body is staged and situated by time and memory, Michelle’s body is of the pure present and of a secret narrative that we are not invited into. Perception, as the only way I am able to “participate” in this work, gets me nowhere. Except the here and now time of this performance: sound, light, rhythm. Bodily fragility. And also, resilience. If participation throws me out into the world through perception, it also returns me to myself, to my own experience, to both the vulnerability and security of my own body.