Forum: Link & Pin

Thea Fitz-James: Gendered Boundaries, Durational Performance, and the Art of Holding It In

FEMINIST FIBRES

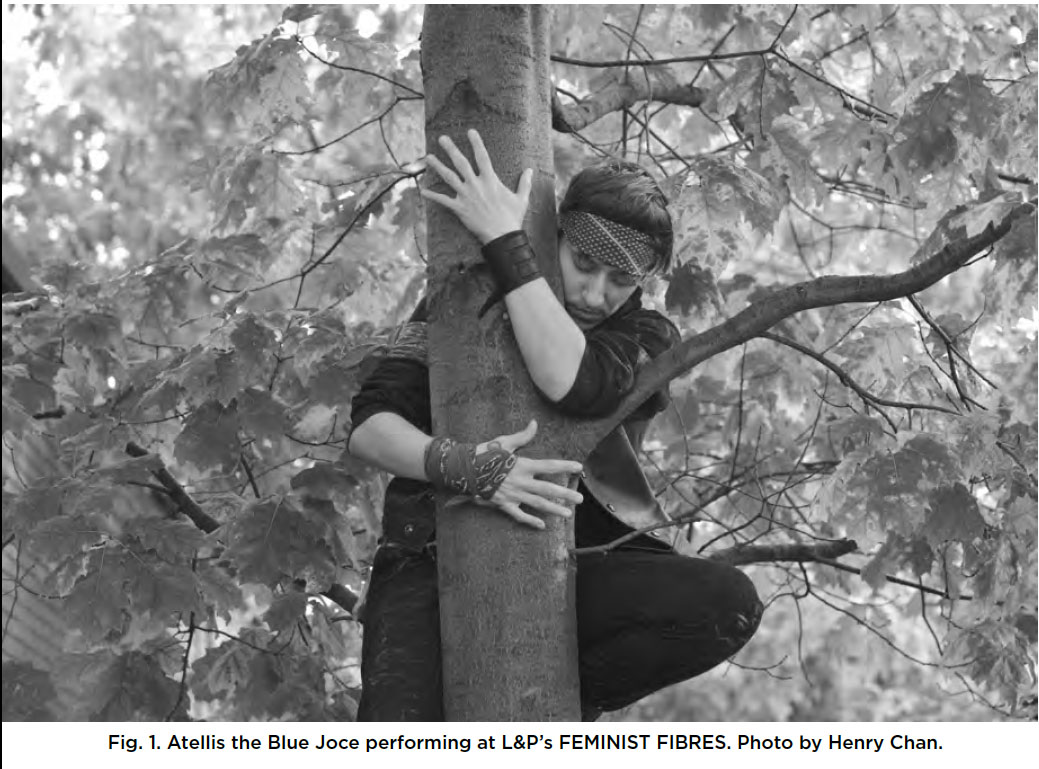

1 LINK & PIN’s first event on 20 October 2013 investigated the intersection of feminisms, textiles, and performance. FEMINIST FIBRES hoped to look more closely at recent trends in re-appropriating and politicizing craft and textile work that has, historically, maintained a gendered and marginalized status in the art world.

-

Presenting Artists:

ATELLIS THE BLUE JOCE

THEA FITZ-JAMES

MARYAM TAGHAVI

HELENE VOSTERSWriters:

ALLA MYZELEV

KELSY VIVASHBaker Artist:

BRETTE GABEL

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Thea Fitz-James: Gendered Boundaries, Durational Performance, and the Art of Holding It In

2 On 20 October 2013, the LINK & PIN performance art series was inaugurated with an event titled FEMINIST FIBRES, which hosted four artists in their embodied explorations of the intersections of feminism(s), textiles, and performance. The initial piece of the day was a durational undertaking by Toronto artist Thea Fitz-James, who sat naked in the centre of the intimate performance space of Toronto’s hub14 creating a pair of men’s pants using a traditional method and pattern. Of particular interest to my own research on the aestheticization of bodily fluids within the contemporary performative frame was my corporeal response not only to the performance itself, but also to the way in which the performance collaborated with the space. More specifically, because the performance began at 8:00 a.m. and continued, uninterrupted, for six hours, I found myself overwhelmed simultaneously with a need to use the washroom, with embarrassment and trepidation at the prospect of disturbing the silence of the space in order to do so, and with an insistent curiosity as to whether Fitz-James would ever break the stoicism of her performance to make her own trip to the washroom.

3 Further amplifying these feelings was the intimacy of the performance space and the proximity of the washroom to it: the washroom was simply a small room in the corner of hub14, and only separated from the rest of the space by the thickness of its meagre door. Any movement to approach this small room caused a stir as the performance was silent except for the muted sounds of sewing and, as such, audience trips to the washroom seemed to become—terrifyingly!—included in the performance itself. As I sat in the performance space, diligently and respectfully omitting these thoughts from my otherwise thorough notes, I found myself questioning why the topic of elimination is so frequently absent from conversations about durational performances. Indeed, being that it is a biological necessity for everyone to eliminate waste, it began to strike me as odd that this one element of durational art—an element that has such an inclusive potential—should be withheld and condemned as crass.

4 Days after witnessing Fitz-James’s performance, I was researching Marina Abramović and came across a serendipitous article from The Huffington Post. The piece, written by Jane Levere in 2010, was entitled, “Marina Abramovic [sic] Answers the $64,000 Question: ‘How Did I Pee?’” The article cites an interview that Abramović had given at MoMA, in which she addressed the issue of elimination during what is arguably her most famous durational piece—The Artist is Present. There have been widespread speculations as to how Abramović urinated during the performance: sketched renderings imagine adult diapers, a catheter attached to a bag hidden under her dress, or a potty concealed in the thick seat of the chair and made available by a small hole. When Abramović responded to this question, however, her answer was almost disappointing: “Abramovic said her chair had a ‘little hole.’ After three days of sitting on it, she said it became ‘so clear to me I will never use it. I never have the urge to pee, I sat on a pillow’” (Levere).

5 My fascination with this article—following my initial reaction, which was to assume that Abramović must be lying—centered on the article’s title. The title 1 is intentionally hyperbolic—presumably, no one is paying Abramović $64,000 to speak about urine—however, the hyperbole in the title does point to the fact that this question has been broadly pondered. Indeed, I would go as far as to suggest that it is one that is likely raised by a number of spectators whenever a performer undertakes durational work of this kind, if for no other reason than that spectators themselves may need to urinate and must wonder—in the same way one often questions their own capabilities in relation to any virtuosic performance—how on earth this durational containment is accomplished. And yet the apparent sarcasm that punctuates the hyperbole in the article’s title simultaneously gestures towards another issue: that is, that this question is imagined as being quite cheeky and trivial. While Abramović has brought countless visitors to tears with her presence, has inspired numerous tributary performances, and arguably shoulders much of the responsibility for shifting performance art itself into the mainstream public eye… how dare we be so base as to ask her about piss?

6 And yet, is it not—at least in part—the issue of piss that implicates many spectators in this performance? While enthusiastic participants in, and spectators to, The Artist is Present hold it in for fear of missing out, does their interrogation of how Abramović can possibly be doing the same for seven straight hours, daily, and for seventy-eight days, not corporeally align Abramović with those observing her?

7 To return to Fitz-James’s performance at FEMINIST FIBRES, I found that the washroom and its relationship to the space and to the performance—that is, as a simultaneously conspicuous and invisible space, that hosted simultaneously conspicuous and invisible activity—was particularly fitting in a performance that was ostensibly about gendered boundaries. The pulling of the phallic needle through the slight resistance of the fabric; the intervention of the naked female body in a public performance space; the donning of a traditionally male garment by the female subject who had spent hours creating it; and the challenging of the power differential that was initiated by Fitz-James’s ability to look back at her spectators all contributed to an overtone of gendered transgressions within this piece. Indeed, it is perhaps the profundity of this tenor that led me to question the containment of Fitz-James’s own body. Surely, surely, she had to use the washroom as badly as I did. And so, surely, I found myself thinking as I watched her stitch, there must be some significance in the act of maintaining the containment of her bodily envelope.

8 In her incredibly insightful 1992 book, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality, Lynda Nead surveys the image of the female nude within Western art history, pointing to the cultural status that this image has accrued as veritably metonymic for the very notion of “high art.” Invoking an image of the female body that finds its roots with Aristotle, Galen, and Hippocrates, she writes:

Over the last several decades, this artistic frame has arguably been reclaimed by female-identified performance artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Valie Export, Yoko Ono, and, closer to home, Jess Dobkin (to name only a few), who not only infuse the frame with embodied explorations of their own corporeal experience, but have also re-moulded it into a vehicle from which they can return the gaze of the spectator.2 In the case of Fitz-James, however, this “looking back” is elevated even more acutely. While Fitz-James ostensibly positions herself as a contemporary (although self-conscious and often satirical) iteration of the female nude, she displaces the physical imperative for decontainment—here, for urination—onto her onlooking audience. Not only does Fitz-James return the gaze, she also returns the enclosure: by creating an environment where using the washroom is all of necessary, disruptive, and slightly embarrassing, she reflects the constrictive, historical artistic frame back to the spectators, binding them in a frame of her own making in which the expectation of containment is not the responsibility of the performer, but of the audience. Moreover, Fitz-James makes the decontainment enacted by audience members an implicit facet of her own performance, and in doing so, she subverts the very structure that demands the containment of the framed female nude by calling into question the observers’ own capacity for containment.

9 The relationship between the performer, the space, and the audience initiated by this subversion was palpable. The discomfort of disrupting the space was not only evident during my own single trip to the washroom, but was available second-hand any time a spectator stepped across the wooden floor, shut the clunky door, relieved themselves and flushed the toilet behind its thin veneer, and re-emerged into the performance space. If these interludes drew attention to the spectators initiating them, then they certainly drew equal attention to Fitz-James, who glanced up, noticed, and continued her work. Throughout this stoic performance, Fitz-James certainly maintained the contained image of the female nude via her own restraint—a state made more and more conspicuous every time another of the room’s occupants made obvious their own release. But her displacement of the biological need for decontainment—the way in which her repression of this impulse became self-reflexive via the bodies of her spectators—radically undermined the historical artistic frame that so casually, and yet with such rigour, hermetically seals the porousness of the female form. Fitz-James, as it turned out, did not need to leave the table in order to remark on this historical enclosure of the female body. Instead, all the while, she perched atop a table in the middle of the room, methodically puncturing fabric to create long seams, eventually putting on and taking off the garment to ensure its proper fit, and occasionally, quietly, pricking her fingers.