Articles

Ambivalent Pathways of Progress and Decline:

The Representation of Aging and Old Age in Joanna McClelland Glass’s Drama

In the last fifteen years, various projects and publications in the interconnected areas of theatre studies, theatrical pedagogy, and literary criticism have highlighted associations between theatrical creativity and constructions of age and aging. Despite a thriving “theatrical gerontology,” the work of contemporary dramatists, especially those outside European and American canons, remains scarcely analyzed. Núria Casado Gual looks at the dramatic work of Joanna McClelland Glass, a Canadian writer born in 1936 in Saskatoon, and who currently lives in Florida. Despite the recognition that McClelland Glass has received in North American academic and theatrical circles, her plays written between 1984 and the present remain unexamined and a more complete study of her playwriting career is yet to be developed. Through the double lens of cultural gerontology and dramatic criticism, Casado Gual offers an overview of McClelland Glass’s theatricalization of old age, based on the main characters and secondary figures that can be associated with this stage of the life course in her work. The composite characterization of McClelland Glass’s older figures ensures not only the complexity of the author’s portrayal of aging-intoold-age, but also its verisimilitude and, therefore, its meaningfulness. McClelland Glass combines notions of progress and decline in the dramatic depiction of her aged characters, generating an ambivalent narrative of aging that re-presents this essential human experience in a truthful and dignified way. Ultimately, McClelland Glass’s recreation of old age is shown to contain the main defining traits of her theatre, as well as the insights that it offers on the complexities and mysteries of the human life course.

Au cours des quinze dernières années, divers écrits et projets issus des champs connexes que sont les études théâtrales, la pédagogie du théâtre et la critique littéraire ont fait ressortir des associations variées entre la créativité théâtrale et les constructions liées à l’âge et au vieillissement. La « gérontologie théâtrale » se porte bien, certes, mais l’œuvre de dramaturges contemporains, notamment ceux qui sont hors des canons littéraires européens et américains, reste peu analysée. Dans cette étude, Núria Casado Gual examine les textes de théâtre de Joanna McClelland Glass, une écrivaine canadienne née à Saskatoon en 1936 qui habite aujourd’hui en Floride. Malgré la reconnaissance à laquelle McClelland Glass a eu droit dans les cercles universitaires et théâtraux en Amérique du Nord, les pièces qu’elle a écrites depuis 1984 n’ont jamais été examinées et l’étude complète de sa carrière de dramaturge reste à faire. En empruntant la double lentille de la gérontologie culturelle et de la critique théâtrale, Casado Gual analyse la théâtralisation de la vieillesse chez McClelland Glass à partir de personnages principaux et secondaires associés à ce stade de vie. La caractérisation composite des personnages plus âgés de McClelland Glass permet de voir non seulement la complexité du portrait que dresse l’auteure du passage à la vieillesse mais aussi sa vraisemblance et donc sa pertinence. Dans sa représentation dramatique de personnages âgés, McClelland Glass réunit les notions de progrès et de déclin, créant ainsi un récit ambivalent du vieillissement qui re-présente cette expérience humaine essentielle d’une manière véridique et empreinte de dignité. En fin de compte, la façon dont McClelland Glass reproduit la vieillesse contient les principaux traits marquants de son théâtre et offre une réflexion sur la complexité du parcours de vie humain et de ses mystères.

1 Since the late 1990s, the interconnected areas of theatre studies, drama in education, and dramatic criticism have highlighted relevant associations between theatrical creativity and constructions of age and aging. This work has clearly shown how, in the words of theatre and age-studies scholar Valerie Barnes Lipscomb, “the theatre can be a natural meeting place for various methods of age-studies inquiry.” Lipscomb made this statement in the context of the 2011 European Association in Aging Studies (ENAS) held in Maastricht, Netherlands, which reflected the good health not only of age and aging scholarship, but very especially of the hopeful intersection of critical gerontology and the humanities. In a subsequent article, Lipscomb emphasized how the theatre, as a “promising site” for humanities-oriented studies of age, offers “a multiplicity of approaches” through its multidisciplinary and integrative nature, and, as such, it can be interpreted as “a locus for various theoretical angles” that can shed light on our understanding of aging (“The Play’s” 118). The interdisciplinary relationship between age and theatre studies defended by Lipscomb and other theatre scholars like Anne Davis Basting has continued to bear fruit in successive conferences and research activities, and more particularly, in the recent creation of NANAS (2013), the North American Network in Aging Studies, which includes theatre experts amongst its members. Numerous projects and publications have also highlighted the important connections between gerontological and theatrical fields, especially with the consolidation of humanistic age studies in recent years.1

2 Despite a thriving “theatrical gerontology,” that is, a blooming interconnection between diverse artistic and research fields related to the theatre and interdisciplinary approaches to studies of age and aging, the work of contemporary dramatists—especially those outside the European and American canons—remains scarcely analyzed as a source of critical reflection on the experience of aging. In an attempt to contribute to the fields of theatrical and literary gerontology, and also with the goal of expanding the critical study of a dramaturgical corpus that deserves broader academic attention, this article looks at the dramatic work of Joanna McClelland Glass, a Canadian-American writer who was born in 1936 in Saskatoon, and who currently lives in Florida. Even though McClelland Glass is also the author of two novels and several film and TV scripts,2 she has primarily devoted her literary career to writing for the stage. Her literary debut took place through the creation of a playscript, “Over the Mountain” (1966), which would be produced and published under the title Artichoke a few years later (1979). Spanning a period of forty-eight years to date, McClelland Glass’s dramaturgical oeuvre now includes twelve playtexts, most of which have been performed in mainstream and regional theatres from Canada and/or the United States, and some of which have also received productions in American university theatres and other commercial theatres in England, Ireland, Germany, and Australia. Bio-bibliographical references to McClelland Glass and her drama appear in studies of Canadian literature and in publications devoted to the work of women playwrights.3 More particularly, the writer was the object of a 1986 bio-critical essay by Diane Bessai that combined biographical information about the playwright with brief analyses of her works, and which looked at the narrative components of her drama and the dramatic structures of her fiction from a holistic perspective.4 Despite these signs of academic recognition, the plays that McClelland Glass has written between 1984 and the present remain unexamined and, consequently, a more complete study of her playwriting career is yet to be developed.5

3 A global consideration of McClelland Glass’s dramatic work highlights the pervasiveness of the theme of aging in her oeuvre, which the dramatist mainly conveys through the creation of middle-aged characters and older figures. Of the totality of her seventy-one dramatic characters, forty-five are between their early thirties and late fifties, and fifteen are between their early sixties and late eighties. The only two children and teenagers that appear in her plays are given secondary roles, with the single exception of Jean in Play Memory, a child-figure whose growth and access to maturity is, significantly, shown throughout the piece. Her nine young-adult characters are marginal, too, excepting for the twenty-five-year-old secretary of Trying, who is in fact a crucial counterpoint to the play’s older figure, around whom the play’s action evolves. The plots in which these characters are involved also render the topic of aging a salient trope in McClelland Glass’s drama. As I will explain further, the playwright foregrounds the passage of time and its effects through the dramatic structures and performative rhythms that she frequently resorts to, a feature that reflects the European influences—especially English, Scandinavian, and Russian—that she received in her formative years as a student and reader of drama (McClelland Glass, “Nuria’s”), and which makes her playtexts especially interesting for a study of theatrical representations of aging. Indeed, the playwright’s predominant representation of mid- and later-life stages and the importance that the passage of time receives in her work lend themselves to the study of the narratives of age that are either propagated or contested through the author’s dramatic worlds—a form of analysis that corresponds with the narrative angle of cultural gerontology, that is to say, the perspective through which “age” and “aging” are interpreted as cultural constructs and as bases of different social discourses and ideologies.6 At the same time, the dramatic nature of the texts I examine underlines the theatricalization of certain aspects of age, which, likewise may confirm or counteract social perceptions and cultural interpretations of aging—in which case the performative angle of cultural gerontology is also significant, namely, that which considers in particular the ways in which age is enacted on the stage, together with the connections between those enactments and behavioural norms associated with chronological age.7

4 Through narrative and performative viewpoints, then, this article provides an overview of McClelland Glass’s dramatization of old age, which will be based on an analysis of the main characters and secondary figures that can be associated with this stage of the life course in her work, and the seven plays in which those characters appear. As I demonstrate, McClelland Glass combines notions of progress and decline in the depiction of her aged characters, thus generating an ambivalent narrative of aging that represents the experience of growing older in a realistic and dignified way. The composite characterization of McClelland Glass’s older figures—which, in the light of Mick Wallis and Simon Shepherd’s classification of character-designs,8 is constructed on psychological, socio-cultural, formal, and discursive bases (19)—ensures not only the complexity of the author’s portrayal of aging-into-old-age, but also its verisimilitude and, therefore, its meaningfulness. Finally, I show that McClelland Glass’s recreation of old age contains the defining traits of her theatre and offers insights into the complexities of the human life course. As the final section outlines, McGlelland Glass’s dramatic oeuvre as a whole mirrors a consistently ambiguous attitude towards the aging process. At the same time, the playwright’s later production, which coincides with her own advancement towards old age, completes the writer's gallery of characters with more elaborate older figures. In the plays produced in her later years, therefore, McGlelland Glass attains a more nuanced depiction of the last phase of the life course, through which she enriches her overall theatrical narrative.

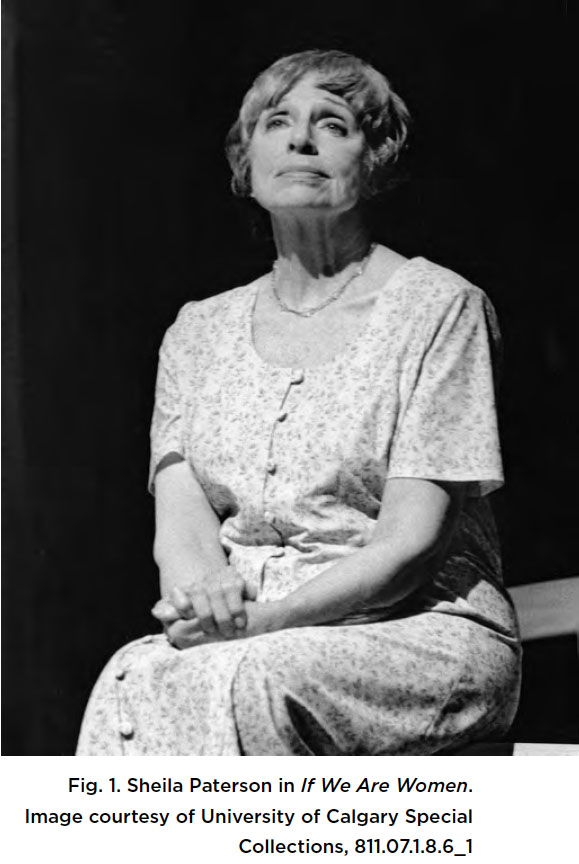

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 The so-called “longevity revolution”—the term used to describe the remarkable increase in life expectancy that has characterized our Western societies since 1900 and especially following the second half of the twentieth century, and which still presents some of the most important medical and social challenges of our modern world—has led to new conceptualizations and interpretations of the process of aging-into-old-age.9 This has especially been the case in the last four decades. As Gene D. Cohen contends, up until the last quarter of the twentieth century aging was largely equated with a process of inevitable decline, and all the changes that the passage of time brought with it were viewed as part of a natural order or biological destiny. By 1975, however, new hypotheses that tried to explain some of the negative changes accompanying the process of growing old began to present those decrements as age-associated “problems” (Cole et al.,A Guide 183). This important conceptual change was paramount not only in the scientific domain, but also in the social one. In Cohen’s words, the “new view of modifiable age-associated problems was a huge leap in itself,” the culmination of which “came with the concept of ‘successful aging,’ defined as aging that reflected the minimum number of problems,” that is, “the minimum degree of decline” (184). The notion of “successful aging” became synonymous with the new gerontology of the 1990s: this was reflected in John W. Rowe and Robert L. Kahn’s influential study (1998), which established the avoidance of disability and disease, together with the maintenance of high physical and cognitive functioning and a sustained “engagement with life,” as the three key components of this groundbreaking success.

6 The changing views of the scientific world around the process of growing old, together with the closely-related social changes that the prolonged life span originated in the second half of the twentieth century, gradually created a narrative of success that contrasted with the dominant narrative of decline whereby aging had exclusively been interpreted for centuries. Both age narratives continue to underlie contemporary interpretations and representations of aging. In this respect, cultural gerontologists and age critics have warned about the traps and dangers of the age ideologies they favour, especially when each narrative is regarded as an absolute model. Whereas the narrative of success has been denounced for its socio-cultural elitism and for ignoring the physical dimensions of aging, to the extent that, as observed by the philosopher Jan Baars, “the negative aspects of aging” could be “denied the dignity and careful attention they deserve” (Cole et al., A Guide 108), pioneer age scholars like Margaret Morganroth Gullette have enlightened our awareness of the master narrative of decline and the ensuing negative stereotypes of aging that it continues to create (7-10), which are so ingrained in the youth-oriented societies of the Western world that they often become invisible to older people themselves. As a cultural product, the theatre is not alien to these diametrically opposed views on aging and, as the drama scholar Michael Mangan sustains, it is in fact “more inextricably bound up with age ideology than is the case with most art forms” due to the human embodiment of its main artistic medium, which “is always of a specific age” (8). At the same time, playwrights and their dramatic worlds are never immune to narratives of age: in other words, plays and their authors can consciously or unconsciously propagate, reinforce, or contradict perceptions of age and aging through their theatrical creations. To name but a few famous examples, Shakespeare himself drew on the well-established Renaissance vision of old age as a phase of inevitable decrepitude through Jacques’s famous monologue in As You Like It, and his iconic King Lear could similarly be interpreted in this light. Contemporary playwrights have perpetuated the same narrative of decline or associated stereotypes of old age despite modern re-interpretations of old age and aging or their apparently positive intentions, as shown by Eric Gedeon’s musical play Forever Young (2010-12). By contrast, modern classics such as George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah (A Metabiological Pentateuch) or Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape subvert stereotypical images of old age through more complex, contradictory, and even provocative renderings of aging (Mangan 134, 175), thereby paving the way for contemporary re-workings of the same topic, even through a re-interpretation of Shakespearean classics: Sean O’Connor and Tom Morris’s Juliet and Her Romeo (A Geriatric Romeo and Juliet), produced in 2010, would be a case in point (212).

7 If the signs that contribute to the representation of older people in McClelland Glass’s drama are taken into account, the narrative of decline seems to emerge, apparently, as the dominant age ideology. In a way, McClelland Glass’s older figures vividly signify the different forms of disempowerment that old age may provoke in the individual, including his/her physical deterioration. In fact, if we pay attention to corporeal aspects of characterization, a high number of bodily identifiers of biological aging related to disease or different disabilities seem to pathologize the age of McClelland Glass’s older characters. Indeed, ailments of various kinds are shown or said to affect the older figures in Artichoke (1979), To Grandmother’s House We Go (1981), Yesteryear (1998), If We Are Women (1994), and Classic Chaos (2006), which range from different degrees of arthritis to brief episodes of memory loss. More especially, the protagonists of Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily (2012) refer to the physical limits of their biological age throughout the play—for instance, Peggy states very early in the piece that she would “be one happy puppy if [she] could get from here to there without using [her] feet,”(6) claiming a little later that “[k]nees’re bad, shoulder’s bad, right ear’s gone deaf, teeth hurt, but the feet are worst” (7); whereas towards the end of the piece Mrs. Dexter claims to feel “so weak, so frail, so bewildered” in an imaginary dialogue with her best friend (52). Likewise, the extreme fragility of Judge Biddle’s body in Trying (2005), which becomes explicit by the older character’s statement in the first scene of the play that “[he’s] always ill. [He is] ill unrelievedly,” (11) announces the figure’s imminent death.10

8 The potential translation of the characters’ various infirmities into the languages of the stage leads to the observation of the performative dimension of a negative discourse of aging in McClelland Glass’s dramatic oeuvre. As noted by Anne Davis Basting, the performative approach to dramatic analysis elicits and expands the questions that may be asked about the production of a play, including the kind of movement quality or facial characterization through which the characters should be recreated (Cole et al., Handbook 262). In McClelland Glass’s drama, age-related decrements are signified through the figures’ bodily posture, gestures, and movements, all of which generate a decayed tableau of old age. The description of Biddle’s movements in Trying is again a clear case in point, especially when the opening stage directions indicate that “[i]t is a given that Biddle’s various ailments keep him in almost constant discomfort” (9). The author’s collective portrayal of the physical deficits of age, which is signified through the plays’ lines as well as through their stage directions, encompasses central figures of overtly distinct chronological ages: thus, whereas Mrs. Dexter and Peggy Randall from Mrs Dexter and Her Daily are both in their mid-sixties and, therefore, could be said to be just on the threshold of old age, Francis Biddle, the protagonist of Trying, is certain to be living the last year of his life at the age of eighty-one. From the viewpoint of the new gerontology that developed in the late 1990s, the two female characters should be regarded as “young old” insofar as they just approach the symbolic retirement age of sixtyfive, whereas the Judge ought to be perceived as having fully entered his “old age” which, after a seminal lecture given by the cultural demographer Patrice Bourdelais,11 has been considered to start at the age of seventy-five (Woodward 1999: xv). Despite the distinctive social ages that these characters represent—that is to say, despite the different social constructions of (old) age and kind of related behaviour they epitomize, and the distinctive expectations they generate as characters that are in their sixties and in their eighties; and in spite of the differentiated chronological ages of the actors that, accordingly, are likely to play them—Mrs. Dexter, Peggy, and Biddle exhibit a persistent awareness of their enfeebled corporealities and, consequently, embody the same narrative of decline. It is significant to note that the three characters are similarly conscious of their failing memory, as indicated, for instance, when Peggy says that both she and Mrs. Dexter have “[m]inds like sieves,” since they “[w]alk into a room, stand there like ninnies, don’t know what [they] went there for”; (Mrs Dexter 8) and when Biddle recalls, with nostalgia, that “[o]nce upon a time [he] had a mind like a steel trap” (Trying 25).

9 McClelland Glass consistently emphasizes biomarkers of old age in her plays, together with the homogenizing effect that these performative signs of aging have upon her older characters. However, the playwright’s representation of aged bodies cannot be separated from the dramatic function that her older figures play in their respective playtexts. Thus, it is significant to notice that physical signs of aging are enhanced through the character-design of leading roles rather than through secondary characters, which avoids stereotyped characterization in both cases.12 As Evvy Gunnarson contends, the experience of the aged body and the vision and interpretation of the world that emanates from it are inseparable (91-93). In this respect, the physical characterizations of McClelland Glass’s older protagonists become necessarily fused with the figures’ psychological construction; and their bodily representations can be regarded as both repositories and channels of expression of their own particularized corpo-realities, including their personal experience of old age. McClelland Glass’s aging figures tend to “feel old” and think of themselves as such. This is clearly illustrated by Winston, the butler in Classic Chaos, who has a special sense of urgency that the other characters lack because, as he says, he is “very far along the corridor of life,” (6) and he feels he “may not be alive tomorrow” (8); Grandie in To Grandmother’s House We Go, who asks her grandson not to smoke in bed because “[she]’ll be ashes soon enough” (38); and Francis Biddle, the older protagonist of Trying, who can refer to himself as “old,” (20) and even “ancient” (13), and frequently contrasts his “age” with that of his 25-year-old secretary, Sarah, in order to explain their discrepant views (11, 17, 20, 43, 48, 58, 60, 77).

10 By contrast, allegedly “successful” models of aging, which negate some of the changes that accompany old age—or that, in fact, deny negative aspects of life in general—are somehow mocked through the figure of Winnie Whitaker, Mrs. Dexter’s neighbour and old school friend (Mrs. Dexter, 22-23, 43). Winnie’s comic characterization as a hyperactive older woman who is always busy with her projects and never has “a hair out of place,” wears gleaming tennis shoes, and always looks “fit, trim [and] colour-coordinated” (43), is clearly opposed to Mrs. Dexter’s constant contemplation of her later-life losses in the privacy of her domestic space. The juxtaposition between Mrs. Dexter’s elaborate character-creation as one of the play’s protagonists—and, hence, as one of the two voices that are heard throughout the two long monologues into which the piece is divided—and, by contrast, Winnie’s flatter characterization as a secondary figure—whose presence is only felt through the noises that come from her house or the telephone conversation she has with Mrs. Dexter and, what is most significant, through Mrs. Dexter’s own opinions about her—clearly favours a narrative of aging that not only underlines late-life adversities but also endows them with significance. In fact, McClelland Glass herself perceives the acceptance of age-related tribulations as part of a more profound understanding of important aspects of life and, ultimately, the world. Referring to her ironic creation of Winnie as an apparently “successful older woman,” the playwright admits to find those kind of women “who seem so utterly proficient in everything to be lacking in a general knowledge, acceptance and understanding of universal weltschmerz” (McClelland Glass, “Third Group”).

11 Despite the aspects that have been analyzed so far, the master narrative of success also finds its place in McClelland Glass’s drama, albeit more subtly. This more optimistic view of aging is especially manifested through the various ways in which the dramatist’s older figures display their own “engagement with life” and resist the obstacles posed by their aging bodies. Hence, McClelland Glass’s older characters often overcome their deterioration through frequent or, at least, intermittent signs of vitality or curiosity, sturdiness or creative energy, and even a humorous disposition, thus modifying an essentialist narrative of decline that their aged corporealities could have suggested on a superficial level. These signs of resistance are manifested, for example, in the ways in which the two women protagonists of Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily force themselves to “keep going,” even though each of them has a different way of celebrating small achievements: in the case of Peggy, the cheerful housekeeper,13 she enacts theatrical salutations and repeats the word “progress” after completing each of her tasks; in the case of her employer, the expression “tread water” becomes a more self-contained mantra that enables her to get through the day (29, 42, 48).14 From a performative viewpoint, the repetition of these examples on the stage illustrates a more assertive form of “doing old age;” one through which a more realistic notion of late-life success is suggested and that is valid until the end of one’s lifetime. As observed in studies of older people’s everyday lives, the resolute wish to persist with one’s customs or duties is essential in advanced stages of the life course (Gunnarson 97). This form of late-life resilience is especially mirrored in the characterization of older figures like Grandie in To Grandmother’s House We Go and Biddle in Trying, who persevere in their daily rituals until the end of their days.

12 The plot structures of McClelland Glass’s plays also contain unexpected turns that force older characters to confront unanticipated conundrums, which enrich the psychological bases of their character-conceptions and the narrative of success they partially support. Important late-life challenges, such as facing the unplanned perpetuation of mother-roles into later life (To Grandmother’s House We Go, If We Are Women, and Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily), coping with late-life marriage failure or, conversely, adjusting to a problematic sentimental reconciliation (Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily), or having one’s sense of authority questioned by a member of a younger generation (Trying), undermine the older characters’ conception of late life as an uneventful, even “peaceful” or “secure,” final period of the life course, in which the older person seems to become a mere observer of the world and of the end of his/her own life. Grandie’s reaction towards her grandchildren’s intention to move in with her illustrates all these examples: “Oh, my. Oh, dear. [. . .] I didn’t expect this, so near the end” (To Grandmother’s 16). As shown by these cases, the later years—and even the last days—of some of McClelland Glass’s aging figures become unsettled and often surprisingly overturned by family and personal circumstances. Although difficult and puzzling, these late-life turning points lead to new lessons and discoveries which make the older figures remain the subject of their own life narrative. Beyond the realm of their dramatic worlds, the plot structures through which they may perform their age in a proactive way signify to what extent old age is, in Molly Andrews’ words, “replete with continued developmental possibilities” (301).

13 If, as has been shown, age narratives of decline and success are closely intertwined in the physical characterizations and psychological bases of McClelland Glass’s older figures as well as in the plot structures in which they are developed, they also co-exist in the social and discursive bases of the playwright’s character creations and in their resulting performative manifestations. In this case, the aspect of old age that should be considered is not so much the figures’ chronological, biological, or personal age, but their social age, by which several structural features underline further the complexities of the author’s portrayal of late-life aging. These structural factors are composed of markers of culture, social-class, and gender, all of which condition the figures’ individual experiences of aging in both positive and negative ways.

14 As far as signifiers of culture are concerned, McClelland Glass’s aging characters predominantly represent American and Canadian citizens of mostly Christian and, to a lesserextent, Jewish backgrounds, and they also include two secondary migrant-figures of English and Irish origins. Significantly, Glass highlights national and ethnic roots as a sign of difference for some of the older characters when their sense of finitude is intensified by the presence of death or its premonition in their respective dramatic contexts. For instance, when Grandie dies towards the end of To Grandmother’s House We Go, her aging housekeeper announces that she wants to go back to Ireland to finish her days there, claiming that there is no stronger tie than “the tie of the land that bore [her]” and that, as a Catholic, she wants to “meet [her] maker in Skibbereen” (72). In Trying, Biddle takes pride in his belonging to an old, Main Line Philadelphia family throughout the play, up to, precisely, his last appearance on the stage (7, 14, 27, 78). Similarly, in If We Are Women Ruth and Rachel contrast their Christian and Jewish backgrounds during their stay at Jessica’s house, their daughter and ex-daughter-in-law, who they are supporting after her partner’s death. When Ruth asks Rachel if, as an agnostic, she is “Jewish at all,” Rachel claims that traditions are, nevertheless, “ingrained, and the antennae are always out,” and that, still today, she receives anti-Semitic terms like “daggers to [her] heart” (26). As these examples show, cultural roots endow some of McClelland Glass’s older figures with a strong sense of identity that provides coherence to their fictional lives; a quality that becomes particularly relevant when the end of their life course is felt to be near.

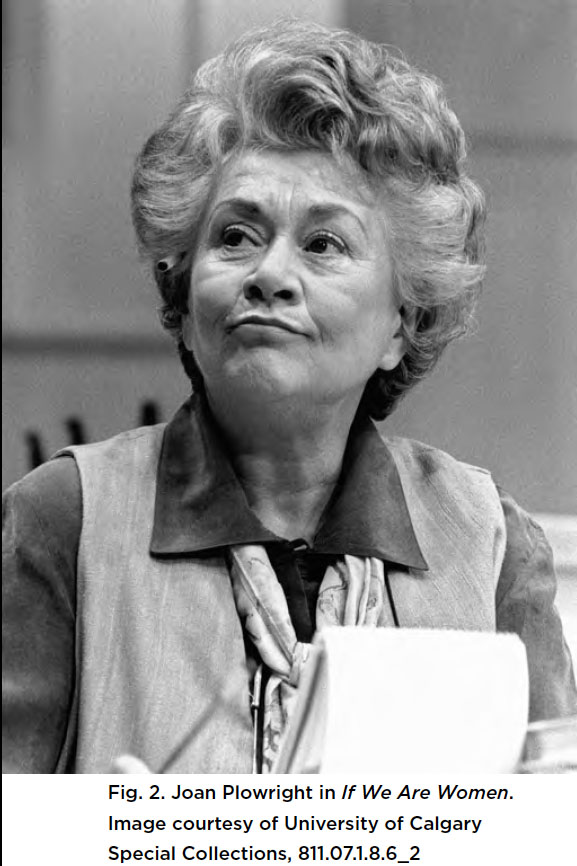

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 215 On the other hand, socio-economic differences amongst older characters bring to the fore the diverse qualities of life that may be encountered within the broad social spectrum of late adulthood, especially when markers of (old) age intersect with those of class. In her depiction of this facet of social age, McClelland Glass seems to confirm Margaret Cruikshank’s belief that class may be the most important determining factor in an individual’s process of aging (115). Thus, although the entrance to later life entails a certain reduction of income for even Mrs. Dexter and Biddle, the most privileged of the older characters in the dramatist’s plays, it poses a clear disadvantage to figures such as Archie and Jake, the two aging farmers in Artichoke, or Peggy Randall in Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily, who have to share their homes in their later years and live with austerity. More extreme cases are alluded to in Yesteryear—albeit through the predominantly comic lens of this piece—every time that Emma, an older Madam, tries to guarantee a better future for the aging prostitutes of her brothel (43, 80, 81). The rural or urban origin of the playwright’s older figures also has a direct effect on their experiences of aging: whereas the older characters that are depicted in the farming and small-town contexts of Artichoke, Yesteryear, and To Grandmother’s House We Go are integrated in their multi-generational communities and/or households, a greater sense of isolation—and in some cases, even despair—is conveyed through Mrs. Dexter and her housekeeper, whose monologues underscore the two women’s loneliness in the city of Toronto. Although the context of Biddle’s characterization is also urban, the form of solitude that this figure signifies is completely different, mainly because it is based on Judge Biddle, Roosevelt’s Attorney General and Truman’s Chief American Judge in the Nuremberg Trials. The high public profile that this older character maintains at the end of his life, which is shown in the play through the attention he constantly receives from historians, journalists, and publishers, contrasts with the sense of quietness he seeks in his secluded office, in which he revises and dictates episodes of his life and, hence, leaves his valuable testimony for posterity. On the whole, McClelland Glass’s socially-diverse portraits of old age signify the extent to which aging individuals and their self-conceptions are conditioned by circumstances that may broaden or constrict their possibilities of growth, integration and cooperation in their private and public spheres, thereby accentuating visions of decline or of development along the spectrum of the forms of aging they dramatize.

16 Gender is the other structural element that stands out in McClelland Glass’s ambivalent dramatization of old age. On the one hand, gender difference is presented as a complicating factor for the older women’s experience of aging, insofar as the inequities that had oppressed them in previous stages of their life course become perpetuated or enhanced in the last phase of their lives. For instance, the sexist discrimination that provoked Rachel’s second-rate professional development in her middle years becomes an important source of frustration that continues to affect this character’s life review in If We Are Women (35). In the family domain, the prolonged motherhood of most of McClelland Glass’s mother- and grandmother-figures becomes an often contradictory late-life experience that makes these characters feel useful or exploited, or both, thus generating a particular life review through which lifelong commitments and personal sacrifices are understood as a form of life. Thus, realizing that the umbilical cord is never cut, that “[i]t hangs there, forever, like a ball and chain,” Grandie wonders: “Is there life after children? [. . .] Is there life after marriage? Is there life after any kind of commitment?”; and concludes: “I suppose if one understands life as ongoing compromise, there is” (To Grandmother's 59-60). Lastly, in the field of personal relationships, old-age, social-class, and gender inequities intersect with each other in Edith Dexter’s and Peggy Randall’s characterizations: whereas the former feels stigmatized as a woman who has been abandoned by her husband “in the last lap of [her] life” (Mrs. Dexter 41), Peggy’s desperate return to an unfaithful ex-partner in order to gain security in her later years potentially reinitiates the cycle of abuse of which she had been a victim. Through McClelland Glass’s aged female figures, old age is represented as a phase of old and new challenges that are contingent on gender-related inequalities. At the same time, the sense of resilience and even capacity for resistance that these women characters possess are also dramatized in their respective plotlines. This is reflected in the selfassuring, rebellious, and finally introspective attitudes that Edith Dexter exhibits towards the end of Act 2—that is, at the end of her long monologue—which express the older woman’s confrontation with the personal and social demons of her later life, and clearly contrast with her husband’s fear of aging and escapist stance (Mrs. Dexter 9-10, 60-61). Mrs. Dexter’s intimate, imaginary reconciliation with her best friend—who has become her ex-husband’s lover—and, ultimately, with herself, mirrors the character’s difficult but brave disposition: “Jess, let’s put a coda on this. I want to, I yearn to believe that I’m not doomed to these frayed days and daily rants. And even though I’m in the last lap of the race, I need to believe that there’s still time to recover. [. . .] I want so badly to be, eventually, sanguine” (Mrs. Dexter 64). In a way, these forms of gendered, latelife resistance could be aligned with the “progress narrative” that Gullette has detected and defined in her analyses of cultural constructions of old age (1988, 2004), and which regards older people as possible subjects of the same narrative of positive change with which children and young people have been associated much more frequently.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 317 Having observed the individual and structural characterizations of McClelland Glass’s older figures, as well as the ways in which they disclose aspects of the narratives of decline and success whereby old age may be interpreted, the playwright’s theatricalization of “time” should also be taken into account in order to comprehend the complexity of her depiction of late-life aging. McClelland Glass’s theatrical treatment of time is attained through a dynamic recreation of the older figures’ “life-narratives” and self-conceptions, which unfold in parallel to their own process of aging. In her drama, McClelland Glass often unites the past and the present of the older figures’ lives through dramaturgical structures that are predominantly sustained and rendered dynamic by a central dramatic conflict, but which also allow for meditative monologues and dialogues to emerge, thereby leading to a fine equilibrium between “actional” and “contemplative” tempos or, in other words, to a delicate balance between theatrical rhythms that either stress change or, alternatively, underline an apparent sense of stasis.

18 Within these composite temporal and rhythmic patterns, chronological time is often fused with the personal time of the figures’ life narrative. When this happens, the characters’ old age becomes a polyphonic standpoint through which all the different ages, age-roles, and significant life-transitions that constitute the character’s identity can be expressed. This multi-layered presentation of the aged self is enhanced by the sequence that closes If We Are Women, which defies the principle of sequentiality that characterizes naturalistic drama through a symbolic cycle of repetitions whereby the most important turning points of the characters’ past lives are evoked simultaneously. The effect of temporal and individual amplification that McClelland Glass attains through the composite tempo of most of her plays, allows for the intermittent dramatization of a “lived” time that is superimposed on a purely chronological, progressive, Newtonian time. This “experienced time,” which is related to the Greek concept of “kairós” and Jan Baars denominates “eminent moment” (113)—enables older figures to express and revise passages of their life narratives in an episodic and open way, without enclosing them in an “act of emplotment”—in Ricoeu’s terms (113)—that would be artificial to their fluent theatrical existence. Moreover, it also prevents them from being encapsulated in one-dimensional presentations of their age, including the poles of decline or success through which they could be interpreted as older figures: for the “eminent moment” that is mostly favoured by McClelland Glass’s theatrical scores encompasses both regrets about late-life losses and past mistakes, as well as hopes about the future, while at the same time enhancing the full value of the present. When the aging protagonists of If We Are Women finish their collective litany about past mistakes and hardships and get ready to welcome their daughter’s/ granddaughter’s boyfriend—and, with him, the future—this eminent, composite moment, which is loaded with experience and at the same time is open to new changes, is finally attained (56-57). The predominantly open-ended dramatic structures of McClelland Glass’s plays reaffirm the author’s dynamic representation of time and its associated constructs. The ending of Trying, in which the recorded voice of Biddle is heard through a tape that his secretary listens to after his death, illustrates the composition of temporal levels, age roles, and notions of finitude and continuity that McClelland Glass depicts in her drama. Using an expression—and referring to a philosophical attitude—for which the female character had been mocked at the beginning of the play, Biddle’s voice says: “Sarah? I doubt that I’ll see you again. I want you to know that I applaud your journey thus far, my dear. Lace the skates, and hit the ice, and stay the course” (82).

19 This “Canadian” piece of advice that the American Judge accepts and returns as a final gift to his young secretary from Saskatoon clearly reproduces the metaphor of the journey of life, through which the lives of individuals and the meanings of aging are often explained. The Judeo-Christian vision of life as a pilgrimage informs the dramatic world of Joanna McClelland Glass as a whole, as demonstrated by plays that feature middle-aged characters in the leading roles and that also enhance this life conception, such as Canadian Gothic (1977), Play Memory (1984), or Amsterdam to Budapest (2014). As I have shown, the composite character-designs, plot structures, and temporal frameworks through which old age is represented in McClelland Glass’s drama signify the last phase of the life cycle as a period of ongoing development, in which the idea of “progress” is not complicit with superficial aspects of the age narrative of success, but rather refers to the capacity to sustain or generate attitudes of resistance against the various challenges that affect the characters’ later years. These challenges include adjusting to new scenarios of increased physical, emotional, and social vulnerability, which can certainly be related to the omnipresent ideology of decline and, hence, to a negative vision of aging. However, the playwright reproduces this dimension of human life through individualized character-creations that voice both personal and socio-cultural visions of old age and which, consequently, overcome superficial representations. In fact, it is through the combination of a narrative of progress and a narrative of decline, or at least through the interconnection and performance of aspects of both constructs, that McClelland Glass re-presents the experience of aging with honesty, depth, and even hope. As Baars maintains, the polarized themes of progress and decline are nothing but “the culmination of fears caused by the insecurities of future life in which an uncertain future of aging is not looked in the eye, but subjected to positive and negative stylization” (108). McClelland Glass not only explores the theme of aging and, in particular, aging-into-old-age with sincerity, but also generates a theatrical discourse that constantly inquires about its meanings and complications.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 420 McClelland Glass’s plays are replete with reflections on the life course, be they on the lessons that are learnt throughout the different stages of our life, on the wounds that are inflicted or received in the way and the significance they acquire, or on the confusion that often substitutes the expected wisdom at the end of the journey and that becomes, in a way, a new form of knowledge. But it is through her older figures, especially those in the leading roles, that is, Grandie, Ruth, Rachel, Biddle, Mrs Dexter, and Peggy Randall, that her process of vital and theatrical inquiry is truly manifested. The older characters’ acute sense of finitude, which is conveyed through their character-designs, plot structures, and temporal representations, enables the playwright to express her recurrent interest in making sense of the dramatic lives she creates and, by extension, of the manifestations of human life to which she alludes in her plays. The same search for meaning and coherence is mirrored in the last scene between Sarah and Francis Biddle in Trying, when Biddle tells his secretary his favourite book titles, through which his own life narrative could perfectly be framed (78). If a title could encompass Joanna McClelland Glass’s dramatic oeuvre, the phrase “Life Happens,” through which one of her characters in If We Are Women defines Chekhov’s theatre (9), would probably do justice to her vivid and ambivalent depiction of human pathways. Yet, to be coherent with the playwright’s dramatic structures, composite forms of characterization and ongoing creativity, this choice cannot be conclusive.

21 As her current projects demonstrate, McClelland Glass’s interests as a writer remain with the theatre and with her constant dramatization of the human quest for meaning, which can lead to new developments in the playwright’s creativity. Very significantly, two of the playwright’s most recent plays—namely, Trying and Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily—tend to make older figures the agents of this quintessential search more prominently than in her previous works. In fact, McClelland Glass’s late-life drama bestows more complex character bases on older figures, thereby suggesting a more defined, personalized, and open gaze towards this phase of the life course. Thus, in her more recent creations McClelland Glass not only underlines negative and positive aspects of later life that were already observed in her midlife plays, but also redefines their interconnection, especially by providing older figures with a more textured existence—one that gives more prominence to their voice and also underscores the structural factors that condition their distinctive process of aging.15 The contrast between Grandie’s character development in To Grandmother’s House We Go (1981)—which is interrupted by the character’s death at the end of the second act—and that of the protagonists of Trying (2005) and Mrs. Dexter and Her Daily (2012), which constitute the centre of both plays, clearly proves this point. Ultimately, the ambivalent portrayal of old age that McClelland Glass continues to generate through her drama, together with the playwright’s persistent engagement with theatrical creation, offer a more authentic and inspiring narrative of progress whereby the diversity and complexities of aging may be contemplated and re-imagined.