Articles

Diamanda Galás and Amanda Todd:

Performing Trauma’s Sticky Connections

Though trauma transgresses borders and produces displacements, too often its study and the treatment of its harmful affects contain it historically, geographically, and institutionally. In the process, trauma becomes dislocated from the larger affective economies through which it is produced. Following the lead of feminist and queer studies scholars, Ann Cvetkovich and Sara Ahmed, Helene brings together two performances—Diamanda Galás’s Defixiones, Will and Testament: Orders from the Dead , and Amanda Todd’s My Story: Struggling, bullying, suicide and self harm —to illuminate sticky connections across the geopolitical particularities of violently produced trauma. She proposes that Galás’s and Todd’s performances of two radically disparate traumas—genocide and sexual assault—need to be understood as contemporary variations of traditional laments that use embodied affective expression to communicate the overwhelming and “inarticulate grief” associated with the trauma of loss and violation (Holst-Warhaft Cue 4). With this essay, Vosters aspires not only to bring Galás and Todd into dialogue, but also to join with them as part of an interdisciplinary and polyphonic chorus of lament against the forgetfulness of trauma’s production.

Même si le traumatisme transgresse les frontières et provoque des déplacements, l’étude et le traitement de ses effets nuisibles imposent trop souvent des limites historiques, géographiques et institutionnelles. Le traumatisme est ainsi décalé par rapport aux économies de l’affectivité qui le produisent. Suivant l’exemple d’Ann Cvetkovich et de Sara Ahmed, chercheures en études féministes et queer, Helene Vosters réunit deux performances— Defixiones, Will and Testament: Orders from the Dead de Diamanda Galás et My Story: Struggling, bullying, suicide and self harm d’Amanda Todd—pour jeter la lumière sur les liens qui traversent les particularités géopolitiques de traumatismes liés à la violence. Vosters fait valoir qu’il faut lire les performances de Galás et de Todd sur deux traumatismes radicalement différents—le génocide et l’agression sexuelle—comme des variations contemporaines de complaintes traditionnelles qui font appel à des expressions affectives similaires pour communiquer l’immense « deuil qui ne peut se faire jour » associé au traumatisme de la perte et de la violation (Holst-Warhaft Cue 4). Dans cette contribution, Vosters tente non seulement de créer un dialogue entre Galás et Todd, mais aussi de les rejoindre dans un chœur interdisciplinaire et polyphonique de complaintes contre l’oubli associé à la production de traumatismes.

In 2006, at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, I saw Defixiones, Will and Testament: Orders from the Dead, Diamanda Galás’s memorial lament for the millions of Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek victims of the Ottoman Turkish genocides of the early twentieth century. Six years later, in 2012, sitting in my Toronto apartment I watched My Story: Struggling, bullying, suicide and self harm, a YouTube video created and shared by Amanda Todd one month prior to her suicide.

1 In many ways, Diamanda Galás’s Defixiones and Amanda Todd’s My Story could not be more different from one another: Whereas the subject of Galás’s performance is the trauma and loss associated with the Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek genocides, Todd’s is the “insidious” day-to-day trauma of sexism, punctuated by her cyber-sexual abuse and peer bullying (Cvetkovich 32).1 Whereas Galás is a highly trained and virtuosic pianist, singer, and composer, it’s not clear if Todd had any formal artistic training, or even if she considered herself a performer (though I certainly call her one). Whereas Galás’s cacophonous acoustic delivery is informed by both years of musical training and her connection to a lineage of Greek lament, Todd’s silent composition is informed by a DIY YouTube aesthetic and her connection to cyber social media networks. Whereas Galás delivers an explosive extroversion of genocide’s horror, Todd “tells” her story with the tentative agency of someone courageously endeavouring to break the isolating and introverting spell of sexual abuse and bullying.

2 And just as Galás’s and Todd’s performances are worlds apart—in terms of both content and aesthetic approach—so too are Galás and Todd themselves. Galás, whose international performance career has spanned four decades, is a Greek-American of Anatolian and Spartan Greek descent. Todd, who created her YouTube testimonial lament in her home at the age of fifteen, was a mixed-race Canadian teenager of Chinese and European descent. But despite the apparent distance between Galás and Todd’s worlds, neither trauma nor its cultural transmission can be contained within particular temporal or geographic locations. Traumas travel across time and space. They traverse generational timespans, diasporic routes, and social— analog and digital—networks.

3 Though trauma transgresses borders and produces displacements, too often its study and the treatment of its harmful affects contain it historically, geographically, and institutionally. In the process, trauma becomes dislocated from the larger affective economies through which it is produced and through which it circulates. While human rights discourses contain the trauma associated with genocide within isolated historical events and geographic locations, legal structures for dealing with sexual assault position the state as the mediator of a traumatic exchange between isolated perpetrators and victims. In both cases, those whose bodies are not intimately impacted are situated as bystanders (empathetic or apathetic) not as participants in the day-to-day affective economies through which these traumas and violations are brought into being.

4 I bring Defixiones and My Story together because they haunt me. I propose that this haunting is a measure of their “success” and that the power of Defixiones and My Story extends beyond their efficacy as performance events to their role as epistemological vehicles for the ongoing, and transnational, transmission of social memory related to traumas produced through violence.2 To facilitate this reading of Galás’s and Todd’s performances I engage scholarship from the fields of psychoanalytic theory, performance studies, memory studies, and queer and feminist studies with an eye to how these theoretical frameworks shape our understanding of trauma and grief related to acts of violence and violation. Importantly, it is not my intent to produce a comparative analysis of two contrasting performances born of dissimilar circumstances. Rather, following the lead of feminist and queer studies scholars Sara Ahmed and Ann Cvetkovich, I bring Defixiones and My Story together in the hopes of making affectively palpable some of the sticky connections between the temporally and geographically disparate traumas that Galás’s and Todd’s performances address.

5 Ahmed uses the concept of “impressions” as a way of resisting the partitioning off of “bodily sensation, emotion and thought as if they could be ‘experienced’ as distinct realms of human ‘experience’” (6). She proposes that impressions are experienced not only corporeally, in the sticky connections made between and across bodies, but also temporally, across time, as histories remain alive through the impressions they leave and through the ways they mark bodies. Looking at how affective economies of hate produce some bodies that belong, while marking “other” bodies as abject, Ahmed draws attention to the way trauma discourse uses a vocabulary of pain that focuses attention on the injured bodies in a way that simultaneously conceals the “presence or ‘work’ of other bodies” (21). Ahmed’s provocation is that emotions circulate as part of a broad affective economy, one that both presupposes and reaches beyond perpetrator(s) and victim(s), and one that is an integral, though often unreflected upon, component of the political economies that constitute social relations of power.3

6 Like Ahmed, Cvetkovich argues that trauma should be treated “as a social and cultural discourse that emerges in response to the demands of grappling with the psychic consequences of historical events” (18). Challenging the “apparent gender divide within trauma discourse that allows sexual trauma to slip out of the picture,” Cvetkovich places “moments of extreme trauma alongside moments of everyday emotional distress” (3). One of Cvetkovich’s aims is to suggest that trauma discourse might help us draw connections between intimate and day-to-day violations and world historical events and in the process contribute to a “larger and interdisciplinary project of producing revisionist and critical counterhistories” (119). Such a project refuses the isolating effects of trauma discourse and of what cultural anthropologist Allen Feldman calls the “structural forgetfulness” of a dehistoricized past and a decontextualized present (172).

7 I propose that Defixiones and My Story need to be understood not simply as aesthetic performances or as personal trauma testimonials, but as contemporary variations of traditional laments. Like skilled lamenters who perform and conduct collectivized improvisations incorporating elements of sound, poetry, and embodied affective expression, Galás and Todd assist the traumatized—living and dead—in communicating their overwhelming and “inarticulate grief” associated with the trauma of violation and loss (Holst-Warhaft, Cue 4). With this article, I aspire not only to bring Galás and Todd together, but also to join with them as part of an interdisciplinary and polyphonic chorus of lament against the forgetfulness of trauma’s production.

8 In reading Defixiones and My Story together in this interdisciplinary, cross-temporal, and transnational way, I endeavour to illuminate some of the foreclosures produced through the containment of trauma discourses within disciplinary, theoretical, identitarian, geopolitical, and temporal boundaries. What possibilities exist beyond these foreclosures, beyond these boundaries? What is the relationship between the myriad of insidious and reiterative performances of racism and sexism we witness in our day-to-day lives and their eruptions into acts of violence, genocide, and sexual assault? How might performance serve as a vehicle towards the production of embodied languages that are capable of resisting trauma’s containment? How are we implicated in the economies of hate that constitute our political and social power relations? What is our role as witnesses to violence? And finally, how might we form polyvocal networks toward the production of counterhistories that refuse the structural forgetfulness of trauma’s dehistoricization and artificial containment?

We who have died shall never rest in peace

Remember me, I am unburied

I am screaming in the bloody furnace of hell…

There is no rest until the fighting’s done.

—Diamanda Galás, “Were You a Witness?”

Through her work, Diamanda Galás models the congruent fluidity of someone who recognizes that the affective economies of hate that produce trauma know no boundaries. As her website makes abundantly evident, Galás is not only a prolific performance (and visual) artist, who is politically engaged—on and off the stage—in the ongoing international struggle against the exile and erasure of Greek culture from the Turkish archives, but also a tireless artistic and political voice for multiple communities of exiled, cast out, and forgotten. For example, Galás wrote and performed Plague Mass, a performance liturgy dedicated to her brother and others who died of AIDS; she has addressed issues of mental illness in her work; and she has been active in bringing attention to the issue of femicide in Mexico and beyond.

9 With Defixiones Galás communicates the horror of genocide by turning words to matter. She physicalizes them. With her virtuosic command of languages, her three-and-a-halfoctave vocal phonemic deconstructions, and her tactical use of electronic technologies, Galás fires, hammers, stretches, and squeezes every monstrous and bloody drop of meaning from them. Literary scholar Nicolas Chare argues that Galás’s “obliteration” of words “is the only way to undo the losses their very coming into existence has entailed” (Auschwitz 60). Extending Julia Kristeva’s theorizations of the abject to his analysis of visual and literary accounts of the Holocaust, Chare argues that for survivors of Auschwitz memory becomes a dangerous “threat to self,” that through the process of recollection, the self collapses into the abject horror of the experience producing a state of “semiotic excess” in which the experience overwhelms language’s symbolic capacities (107). Kristeva distinguishes between the symbolic and semiotic functions of language, with words, grammar, and their logical orderings making up language’s symbolic aspect, while the more material elements of voice, tone, and rhythm constitute language’s semiotic component (2). In literary texts the phenotext— the part “concerned with [. . .] efficient communication”—serves language’s symbolic function, while the genotext—“the style through which the communication is carried out”—comprises the semiotic aspect (2).

10 The genocides of Galás’s lament, like “The death-world of the Nazi concentration camps,” Chare writes, “constituted a gap in linguistic experience for those caught up within them because these events pulverised the self” (“Grain” 60). Extreme trauma, in this sense, casts people outside of the realm of interpretation as constituted through a symbolic order, and therefore the trauma becomes unrepresentable through language, unless, as Chare suggests, language is able to reach beyond symbolic representation to semiotically embody the horror of the abject in the words. Through her use of stylistic innovation, Chare argues, Galás transcends language’s limitation as a medium of purely symbolic or “efficient” communication and therefore facilitate the transmission of trauma’s abject horror:

11 Whereas Chare uses “semiotic excess” to refer to that which exceeds the symbolic, in her analysis of Galás’s vocalizations, queer studies and musicology scholar Freya Jarman-Ivens uses “semiotic” to reference the relationship of signs and signifiers in language’s production of rationalist meaning. Drawing upon French literary feminist theorists of the 1970s—most notably Hélène Cixous—who critique language as an inherently masculinist order, JarmanIvens looks at Galás’s use of glossolalia—“a kind of free-form phonemic vocalization,” literally defined as “speaking in tongues” (142). Though Jarman-Ivens resists an uncritically essentialist reading that suggests “that Galás’s glossolalia represents a simply radical feminist move in its rejection of semiotically structured language,” she nevertheless argues, “the trope of rational(ist) language as a male-dominated or masculinist realm must give us cause to wonder what the gendered politics are of [Galás’s] glossolalic speech” (145).

12 Galás herself is less ambivalent about laying claim to an essentializing gendered lineage that challenges not only language’s symbolic masculinist order, but also monotheism’s masculinist order: “From the Greeks onward [women’s] voice has always been a political instrument as well as a vehicle of occult knowledge or power” (qtd. in Juno and Vale 10-11). Most churches are places, Galás argues, “where the masses are placated, whilst robbing them of their money” (qtd. in Chare and Ferrett 72).4 Just as she viscerally dismembers language’s symbolic genderhierarchy, Galás also de-sacralizes and re-sacralizes the sacred texts of masculinist orthodoxies:

13 Though often used to refer to “meaningless” or nonsensical speech, glossolalia’s etymological roots poetically trace the word to its “echoic origins,” or its onomatopoeic representation of corporeal experience (Harper). With her glossolalic vocalizations Galás does not eradicate meaning—she liberates it from both the limiting logic of language’s symbolic orderings, and the placating logic of religious orthodoxies designed to serve a racialized and gendered status quo. Galás does not speak of genocide through a language of abstraction or pacification, she becomes its echo. As her audience, we do not simply witness a performance about genocide, we are penetrated by its horror. No longer entombed in the forgotten burial grounds of history’s then and there, the Armenian, Assyrian, and Anatolian Greek victims of the Turkish genocides haunt us in the sticky here and now. With her glossolalic deliverance Galás exhumes and gives flesh to their horror, pain, and rage.

Performance as a vocabulary for telling the untellable

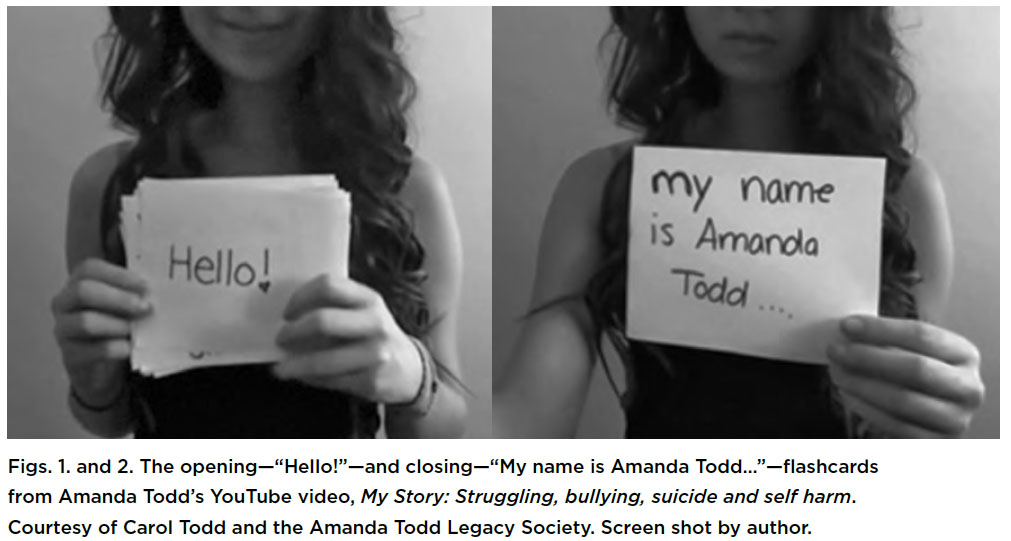

14 On 10 October 2012, fifteen-year-old Amanda Todd of Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, killed herself. One month prior to her death, Todd posted My Story: Struggling, bullying, suicide and self harm, a nine-minute YouTube video in which she used flashcards to narrate her three years of cyber-sexual abuse, cyber-stalking, and bullying. In the aftermath of Todd’s suicide My Story went viral and in the process brought issues of cyber-sexual assault and bullying out of the isolating arenas of the privatized home or the interiorized individual psyche and back into the public sphere in which and through which sexual and social violence operate.

15 Just as the locations of Galás’s and Todd’s subject matter differ radically, so too do their approaches of reaching beyond language’s symbolic representation to express the abject horror of the traumas of genocide and sexual abuse. Whereas Galás uses her highly trained virtuosity as a performer—composer, singer, pianist—to transcend the limits of language’s symbolic capacity to communicate genocide’s semiotic excess, Todd draws upon aesthetic and communicative mediums—webcam and YouTube flashcard narration—that have deep resonance for her, and her peers, to communicate the semiotic excess associated with cybersexual abuse and bullying. Todd’s use of flashcards in her YouTube performance is a stylistic mechanism through which she is able to tell the untellable.

16 While the rich history of flashcard narration in popular culture is beyond the scope of this article, one highly relevant example of its usage is in the 2010 teen comedy—Easy A. Using the combined spoken and flashcard webcam narration of protagonist Olive Penderghast (Emma Stone) as a framing devise, Easy A tells the story of how a lie about losing her virginity quickly turns Olive into a contemporary Hester Prynne.5 Unable to shut down, or extricate herself from, the rumour mill, Olive sews scarlet “A”s onto a vamped-up wardrobe and puts her newfound notoriety into service to rescue male peers who are being bullied— for being gay, nerdy, “fat,” or otherwise outcast—by pretending to have sex with them.6 The film ends with Olive coming clean with a webcam confession.

17 Because of Easy A’s popularity, it’s likely that Todd and her peers were familiar with the film and that My Story’s use of the reiterative and citational dynamics of flashcard narration is reflective of its growing currency as a communicative agent among youth. Moreover, as Christine Pullin argues, because YouTube has become an increasingly popular as a site that “offers digital space to millions of performers,” it has come to serve as a important mechanism for the formation of counterpublics wherein “groups who are aware of their subordinate status [can] claim public space and enter public debate” (146). In posting My Story on YouTube, I propose that Todd was endeavouring not only to share her personal struggle, but also to hail a community of support—perhaps even one of resistance.

18 Todd’s story—as told through her seventy-seven flashcard narrative—goes something like this.7 In seventh grade Todd and some friends were hanging out in a chatroom where twelve-year-old Todd, as pubescent object of a masculine desiring gaze, is told that she’s “stunning, beautiful, perfect.” One of her “admirers” asks her to “flash” her breasts. She does. A year later Todd receives a Facebook message from “him.” She doesn’t know how he found her but now he’s telling her that she has to “put on a show,” for him or he’ll send her “boobs.” She doesn’t. He does. He sends her “boobs” to her friends, family, and teachers. He uses them as his Facebook profile picture. She changes schools. He tracks her down. Over and over, from school-to-school, city-to-city, he cyber-stalks her. Todd’s bullying progresses beyond cyberspace to verbal and physical bullying at school and within the community. Todd descends into a state of anxiety and despair, she attempts suicide (twice), she begins cutting, she stops leaving the house. And she makes My Story.

19 As queer studies scholar Ann Cvetkovich argues, “Trauma puts pressure on conventional forms of documentation, representation, and commemoration, giving rise to new genres of expression, [. . .] that can call into being collective witnesses and publics” (7). Through her use of the social media vehicle of YouTube, Todd not only confronts her cyber-stalker and cyber-bullies, she also refuses to maintain the socially prescribed boundary that partitions her interiorized pain from the publics it affects, and is affected by. In staking her claim to the cyber-public sphere Todd rejects the mandate of fear produced by the affective economy of sexual violence, which “works to contain some bodies such that they take up less space” (Ahmed 69). With My Story, Todd hails a witnessing polyphonic cyber-chorus.

20 Through her embodied use of flashcards and YouTube video Todd also tells her narrative of sexual abuse in and through a medium that has become increasingly renowned for its ability to sexualize and eroticize women and ever-younger girls, without falling prey (not this time) to its eroticizing gaze. No longer given-to-be-seen, Todd returns the gaze through her combined presence and absence. Despite her eyes being positioned just outside the video’s frame she remains a witnessing presence as she enacts her agency through another gesture of reversal— using her flashcards to simultaneously reveal and conceal her “body/self” (Jones 1998).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 121 Whereas Amelia Jones uses the concepts of body/self and “body art” to distinguish feminist artist’s deployment of an embodied subjectivity from that of an objectified or universalized body, Rebecca Schneider uses the term “explosive literality” to describe how, through the use of the explicit or sexualized body in performance, feminist artists collapse the symbolic and the literal (Explicit 2). Extending Vivian Patraka’s notion of binary terror as the “dissolution of binary habits of sense-making and self-fashioning” (13), Schneider argues that feminist explicit body performances explode the “lexical imaginary” that is constructed around women’s bodies through the collapse of art and pornography (16). The explicit body performances that Schneider examines, like that of Annie Sprinkle’s Post Porn Modernism, explode or terrorize the normative binary subject/object relationship between man as active subject, and woman as passive (art/sex) object.

22 With My Story, Todd performs an uncanny inversion of the kind of explicit body performances Schneider writes of. The placards that shield Todd’s breasts gesture not only towards the trauma of her abuse, they act as literal signs of her agency—her choice—to cover or uncover. Like the burlesque artist’s use of plumes, the power of Todd’s placards, in part, is in how they draw attention both to the breasts that are concealed and to the possibility of their revelation.8 This time, Todd is the one literally holding all the cards. Agency, the decision to reveal, or not reveal, is in her hands. In an inverted gesture of explosive literality, instead of revealing her breasts, Todd constructs a frame that places her subjective voice, or body/self, in place of her objectified breasts, thereby collapsing the space between her subjectivity and her objectification.

23 Since I only learned of My Story after Todd’s suicide, I realize that it’s impossible to separate its affective impact as a “performance” from its impact as a memorial. I do not, however, read My Story as a suicide note—nor do I believe that Todd intended it as one.9 I read My Story as Todd’s testimonial lament against the annihilation of her subjectivity and as a contrapuntal shout-out to others struggling to survive while under the siege of the hateful economies of sexual assault and peer bullying. In a statement accompanying My Story Todd writes:

24 While some might argue that Todd’s suicide is what has made My Story most compelling, I vehemently disagree. Todd’s tragic death may well have been a significant factor in My Story’s going viral, but I propose that the video’s potency is born equally of Todd’s audacious hope (for herself and others) in the face of ongoing violation, and of her capacity to communicate her experience through the artful deployment of compositional choices. Like Galás, Todd found the formalistic mechanisms to convey the semiotic excess of her trauma. Through her fragmented flashcard narrative Todd tells the untellable, while simultaneously, through her silence, she conveys its untellability. The flashcards of her making, the cards that carry her unspeakable words, shield her breasts, the “boobs” that she had been coerced into flashing, and that have in turn been flashed again, and again, and again, against her will for years. And like Galás, with her testimonial lament, Todd hails a community of survivors and witnesses in resistance to sexual abuse and bullying. For me, the tragic fact that Todd herself did not survive does not in any way diminish her artistry, her efforts, or My Story’s ongoing significance.

Beyond the eroticization of violence: Lament as a call to conscience

25 As feminists and anti-rape activists have long argued, sexual assault is an act of violence, domination and control perpetrated through sexualized means. But the sexualization and feminization of violence are not limited to acts of sexual assault. As performance studies scholar Diana Taylor argues, the sexualized feminization of the other is a familiar trope of violent nationalisms. During Argentina’s Dirty War, Taylor notes that the military junta’s torture scenarios were “organized as [. . .] sexual encounter[s], usually entailing motifs associated with foreplay, coupling, and penetration” in which both “[m]ale- and female-sexed bodies were turned into the penetrable, ‘feminine’ ones that coincided with the military’s idea of a docile social and political body” (152).

26 Violence’s feminized sexualization makes its aesthetic representation risky. As Taylor notes, in their efforts to represent the eroticized and feminized violence perpetrated by the Argentinean military junta some post-junta theatrical productions problematically reproduced the violent narratives they sought to critically expose. For example, in her account of Paso de dos, written by playwright Eduardo Pavlovsky—a confirmed “enemy of the military regime”—and performed by the playwright and (his wife) Susan Evans, Taylor argues that while the production exposed the junta’s eroticized and feminized perpetrations of violence, it did so by staging “torture as a love story” (5) and a “fantasy of reciprocal desire” (20).10 Pointing to a limitation of Elaine Scarry’s assertion that physical pain resists representation, performance and Holocaust studies scholar Vivian Patraka also suggests that far from having “no language for representing the body in pain [. . .] we have parceled out pain, humiliation, and atrocity into mass culture forms for spectatorial pleasure” (87).11 Patraka notes, for example, that since World War II Nazi S/M has become one of pornography’s central tropes: “A trope that [not only] sexualizes violations to a gendered female body by confusing damage and pain with the sexual and thereby eroticizing the imposition of violence [but one that also posits] a contractual relationship between victim and perpetrator” (90). In addition to the challenges of finding a vocabulary to communicate extreme trauma’s semiotic excess, aesthetic representations of horror also risk reproducing the eroticization and feminization of violence’s perpetration.

27 Despite Galás’s explicit use of her body in many of her performances—for example, she delivers much of Plague Mass, the performance liturgy she wrote for her brother and others who died of AIDS, with her breasts bared—there is nothing seductive about Galás’s representations of violence and genocide. Hers is not an eroticized or beautified horror. Galás becomes horror, in all its monstrosity, becomes “the sound of the plague, the sound of the emotions involved” (Galás qtd. in Chare, “Grain” 61). Nor does Galás permit her audiences a position of voyeuristic or spectatorial distance. Just as Todd, in an act of explosive literality, collapses the space between her subjectivity and the objectifying gaze of sexual abuse, Galás transmits her damning lament through a quadriphonic sound system that surrounds the audience, placing us “in [her] cage,” invading our space, our bodies, with the sounds of genocide, and subjecting us to “the rack of conscience” (57).

28 While internationally acclaimed for its artistry, Defixiones is not simply entertainment. Nor is it lament expressed as a melancholic longing for a past beloved or a beloved past. Defixiones takes its name from the warning curses against desecrating the dead that are inscribed onto the metal plaques placed on the graves of Greeks killed in Turkey. These curses, Galás explains, are “the recourse of someone without any power at all—the last recourse” (Galás, “Diamanda Galas”). As a Greek-American—Galás’s father is of TurkishGreek-Anatolian heritage, and her mother, of Spartan-Greek heritage—Galás draws directly from traditional Greek women’s lament songs.

29 While Chare discusses some of the formal elements of the traditional Greek lament that Galás integrates into her performances, he pays only minimal attention to their social and political significance. Feminist historian Gail Holst-Warhaft, on the other hand, sheds light on the relationship between the aesthetic, affective, and political characteristics of traditional Greek lament. For example, she argues that counterpoint, or polyphony—a central compositional component of lament in most pre-industrial societies—needs to be viewed not merely as a formal or aesthetic aspect of lament but also as reflective of lament’s role as a communal art and of its context within the social sphere. Holst-Warhaft argues that the potential of lament as a social and political force was not lost on those in positions of power. Interdicts against women’s lament in ancient Greece began as early as the sixthcentury B.C.E. when laws introduced by Solon restricted the practice of “lamenting the dead” to those directly related to the deceased (Cue 34). Similarly, Parita Mukta writes of controls placed over women’s lament in colonial India, that the real significance of the shift in mourning towards more privatized, state, and institutionally mediated practices lies in containing the “transgressive, public nature of mourning” (44). Despite the near disappearance of traditional lament and funerary practices throughout much of the contemporary West, HolstWarhaft notes that remnants of women’s traditional lament have survived in practice, and through oral history and collective memory, in remote regions throughout the West, like the Mani region of Greece.

30 Moirolóighia—the lament songs of the Maniot—translates to mean “foretelling one’s fate” (Freman-Ivens 152). The fate being spoken does not belong to the singer alone. It is the fate of the dead brought into an antiphonic dialogue with the living. “The [contemporary] moirologists,” Galás explains, “speak directly to the dead and in strange voices, after waiting for the priest to finish incarnating the dead into a nameless Christ yet again” (“Mouth” n. pag.). Unlike Western conceptions of lament, the moirológhia is more than an expression of grief by mourners: it is also an affective and sonically complex improvisational conversation with the dead. Nor is there a clear distinction between expressions of grief and expressions of vengeance in the moirológhia (Holst-Warhaft, Dangerous 6). But as Jarman-Ivens argues, the vengeance that Galás enacts, is on the listener: “If moirológhia means ‘to tell one’s fate,’ she is not only telling her fate, or only telling the fate of the dead, but also the fate of all of us based on our silences, our ignorances, and hence our complicity with the hatefulness of the events with which she is concerned” (159).12

31 The liturgies of Galás’s making are not petitions to a conventional God, they are “cries to a god invented by Despair—by a person about to be executed” (Galás qtd. in Juno and Vale 8). With Defixiones, her ninety-minute lament-curse, Galás calls upon a chorus of voices, living and dead, who speak in many tongues and across multiple genres—sacred masses from the Armenian Orthodox church; biblical extracts (Psalms 22, 34, and 88); blues songs (“See That My Grave is Kept Clean”); and the work of poet-authors (Paul Celan, Todesfuge; Henri Michaux, Je Rame), whose writings are themselves examples of language deployed to reach beyond the symbolic to communicate experiences of violently imposed exile, alterity and abjection. She then applies the same deliberation and care she takes in selecting her texts, to mining and reworking them. Of her artistic practice Galás writes:

32 Through her extra-linguistic vocal manipulations Galás wields her painstakingly researched and carefully selected texts like weapons: “I [want] to produce an immediate extroversion of sound, to deliver a pointed, focused message—like a gun” (Galás qtd. in Juno and Vale 8).13 Galás further manipulates her voice with the aid of technology. Using a tone control—“a specialized high-pass EQ [that bypasses] mid- and low-frequencies”—Galás produces “high frequencies [that] really fuck people up” (Galás qtd. Chare, Auschwitz 60). Layering her live multi-octave and glossolalic vocal deconstructions with a technologically distorted echo and pre-recorded taped-over vocalizations Galás casts her audience into a sensorial maelstrom where past and present tumultuously “inter(in)animate” one another (Schneider Performing).14 Following Schneider I propose that, with her soundscape, Galás “moves meaning off of the discrete site of the material [the present of Galás’s performance], and off of the discrete site of temporal event [the Armenian genocide], and onto not only the ‘spectator’ [. . .] but into chiasmatic reverberation across media and across time in a network of ongoing response-ability” (Schneider 164-65).15 The remembering that Galás calls for is not a passive or nostalgic act. It is a weighty responsibility.

33 In Defixiones, as in the traditional moirológhia, meaning and affect are not bifurcated, nor are grief and rage. Through her use of multiple languages, and an extra-linguistic vocabulary of horror’s affect materialized as sound, Galás becomes a contemporary one-woman polyphonic chorus annulling the divide between the living and dead. Like the moirológhia from which it draws much of its formal power, Defixiones is a political act that is part of an ongoing struggle against erasure and a “push for a redefinition of the nature of our relationship to death” (Jarman-Ivens 160). Coming as it did from the proscenium stage, Defixiones did not function in the sense of traditional lament’s polyphonic “call and response,” in which there is a literal joining in of the community as chorus. But like the traditional Greek moiroloyistres, through the “art of speaking, cursing and singing grief” Galás makes her audiences prisoners of conscience, demanding that they feel, remember and think—perhaps even act—on behalf of the violated dead (Holst-Warhaft, Cue 23).

Performing trauma as a means of mobilizing counterpublics

34 Todd received both psychological counseling and psycho-pharmaceutical treatments for “her” trauma. But as Cvetkovich points out, framed by an individualizing psychoanalytic lens, trauma discourses, and their associated treatment plans, have a limiting and depoliticizing effect.16 Cvetkovich suggests that “Thinking about trauma from [a] depathologizing perspective [. . .] opens up possibilities for understanding traumatic feelings not as a medical problem in search of a cure but as felt experiences that can be mobilized in a range of directions, including the construction of cultures and publics” (47). With My Story Todd counters the individualization, interiorization, and pathologization of trauma’s affects by taking trauma out of the therapist’s office and placing it back in the psycho-social sphere of the cyber-world in which her original assault was experienced and through which her now-multiplied abusers continued their torment.

35 Tracing trauma’s social dimension resituates it not only beyond a pathologizing medical discourse but also beyond the “juridical [model of the] monadic subject of the West” which individualizes and depoliticizes both trauma’s victim (or survivor) and its perpetrator (Feldman 179). Just as Todd received psychological care, her case was also under the “care” of the police. It was not until Todd’s testimonial performance that her actions (what she, in a gesture of internalized victim-blaming, calls “her mistakes”) and the actions of her perpetrators, are placed back into a social context, one that reveals the larger systemic problems of how sexism operates through social media sites and how its operation intersects with, exacerbates, and is productive of the insidious trauma of peer bullying.

36 On 7 April 2014 police in the Netherlands arrested a thirty-five year old Dutch man on charges related to Todd’s case (White and Tabor). While I’m pleased to learn that his cyber assaults and coercions of young women (and, according to the Globe and Mail’s report, men as well) have been stopped, I do not consider either Todd or her sole identified perpetrator to be isolated individuals. Todd and her perpetrator(s) are part of a larger affective political economy to which we all belong. With My Story, Todd de-privatized her assault and left an impression on an ever-growing chorus of witnesses. My Story has become a vehicle through which the affective connections between the everyday “insidious” trauma of sexism; the more “punctual traumatic” experience of cyber sexual abuse; and the everyday trauma of peer bullying are being made palpable (Cvetkovich 32-3). Whether or not Todd realized it at the time of her death, My Story has mobilized a host of online cultures and publics.

37 Reactions to Todd’s story have been varied and are ongoing. There has been an outpouring of public empathy that has brought to the fore issues of predatory cyber-sexual assault and stalking; of peer bullying and its traumatic and sometimes fatal reality effects; and, of the failure of contemporary educational, legal, and psychological institutions and discourses to adequately address issues of cyber-stalking, sexual assault and bullying. For some who, like Todd, have experienced bullying, My Story has become a “how-to” model to tell their own stories. There has also been a significant backlash to the outpouring of empathy in response to Todd’s video. Some argue that Todd brought her suffering upon herself; some point out the cynicism of responses from a public who are largely complicit, if not directly in Todd’s bullying, in the production of a culture that turns a blind eye. Others, echoing Judith Butler’s (2004) critique of the differential grievability of lives, suggest that the post-mortem outpouring of empathy towards Todd is because she’s “a pretty white girl”—a mistaken and problematic assumption that, in addition to invisibilizing Todd’s mixed-race heritage (she is of Chinese and European descent), masks the extent to which Todd’s “harassment was motivated by sexism, misogyny and racist exclusion” (Lee and Chatterjee).

38 However, the sheer volume of responses to My Story is a testament not only to the power of Todd’s performance, and to the pervasiveness of an affective economy of sexual violence, but also to the fact that Todd’s story did not, and does not, reside in Todd alone. As Ahmed argues, “emotions do not positively inhabit anybody or anything, meaning that ‘the subject’ is simply one nodal point in the economy, rather than its origin and destination” (46). In placing her performance in the online public sphere, Todd is not isolated (at least not in death). With My Story Todd has left an impression and called forth a polyvocal chorus who have taken up Todd’s story as their story, as our story, as a story that did not begin with Todd’s abuse, or end with her death, as a story that needs to be grappled with at a social level.17

Conclusion: Haunted and hailed

39 In juxtaposing Defixiones with My Story it is not my intent to deny the privilege of Todd’s location relative to either more marginalized communities that suffer the violence of genocide, or those who suffer from the large scale violence of indifference to their suffering. Needless to say, Todd’s trauma differs radically from the experience of victims of genocide. Though I feel a somewhat queasy reluctance in situating My Story within the context of narratives of the collectively experienced traumas of genocide, torture and war, like Cvetkovich, I also consider this reluctance to be reflective of socially constructed biases in trauma discourse. These biases serve to marginalize and privatize not only the trauma associated with sexual assault, but also the insidious traumas produced through acts of day-today racism, sexism, homophobia, and capitalism. Moreover, by treating sexual assault as a separate issue and one that primarily affects individual women, trauma discourse’s gender bias helps mask the extent to which violence on a global scale operates through tropes of feminized sexualization.

40 Defixiones and My Story are similar in the work they do. Both performances bridge the border between trauma’s internal and social location to forge “overt connections between politics and emotions,” and both performances, in their own way, have left lasting impressions on the publics they’ve hailed and the choruses they continue to constitute (Cvetkovich 3). Through their radically disparate performances Galás and Todd eradicate the innocence of spectatorship. The genocide of Galás’s lament-curse cannot be conveniently ensconced in a dehistoricized time and place, a then and there. As a Greek-American, of Anatolian and Spartan Greek descent, Galás is part of a Greek Diaspora produced through trauma.

41 Likewise, Todd’s trauma while intimately focused, is neither local nor temporally contained. The man charged with circulating her cyber-sexual assault is from the Netherlands and her YouTube response extends beyond any fixed geographic location, and even beyond the precarious temporality of her too-short life. Neither genocide nor sexual assault happens in a vacuum. They are not isolated occurrences. They do not come without warning, they could not happen if we were able to apprehend their horror in the making, and our place as part of the affective political economies through which they operate.

42 Taken together, Defixiones and My Story—performances of two seemingly disparate and disconnected traumas—illustrate the integral role of performance (staged, ritual, or DIY) in the ongoing transmission of knowledge of and about trauma. Through their performative testimonials of grief, rage, trauma, and despair Galás and Todd have hailed me as one in a chorus of witnesses called to turn toward, rather than away from, suffering. Like Galás and Todd I endeavour to implicate my audience (readers) as a witnessing public: To what extent is Galás directing her lament-curse not only at those directly responsible for the genocides, or their erasure from the historical archive, but at the world of bystanders of which we all belong? And, to what extent is Todd’s story of cyber-sexual abuse and bullying really “our” story?—a story of the daily toleration of a hateful affective economy of sexual violence. In juxtaposing Galás and Todd, I am not suggesting an equation: Genocide = Sexual trauma. Rather, I propose sticky connections across the geopolitical particularities of violently produced trauma and the broader social structures in and through which they are consummated.