Articles

An Autoethnographic Reading of Djanet Sears’s The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God

Djanet Sears’s play The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God offers a generous opportunity for the careful contemplation of the intersections between Christianity, motherhood, and blackness in Canada—a topic hitherto unexamined in scholarship about Sears’s plays. The protagonist’s search for God is a personal exploration of self in relation to each of these topics; similarly, Naila Keleta-Mae draws from the analysis of self through the article’s incorporation of methodologies employed in autobiographical performance and autoethnographic research. Specifically, the author maps her examination of Sears’s play through her own body and experiences of Christianity, motherhood, and blackness in Canada. One of the key ways that this article seeks to differ itself from traditional Canadian scholarship is by foregrounding the explicit ways the scholar’s topic of inquiry intersects with her/his/their personal lived experience. To some extent, this article is about visibility and transparency—it is an effort to make equally visible the preoccupations of the scholar in her/his/their analysis of a subject matter—in this specific case it is the unambiguous articulation of why Keleta-Mae cares about Sears’s play.

La pièce The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God de Djanet Sears nous invite généreusement à examiner les points de rencontre entre le christianisme, la maternité et la négritude au Canada, un sujet qui jusqu’ici n’a pas été étudié dans les recherches portant sur les pièces de Sears. Dans sa quête de Dieu, le personnage principal de cette pièce explore en elle-même chacune de ces facettes; de même, l’auteure de l’article, Naila Keleta-Mae, s’inspire de l’analyse du soi pour incorporer à sa contribution des méthodes employées dans la création de performances autobiographiques et dans la recherche autoethnographique. Keleta-Mae recense son examen de la pièce de Sears par l’intermédiaire de son propre corps et de ses expériences du christianisme, de la maternité et de la négritude au Canada. Elle cherche en outre dans cet article à se démarquer des recherches canadiennes traditionnelles en explicitant les façons dont son sujet d’enquête recoupe les expériences qu’elle a vécues. Dans une certaine mesure, l’article porte sur la visibilité et la transparence : il s’agit d’une tentative de rendre visibles les préoccupations de l’auteure à travers son analyse du sujet—dans ce cas-ci, elles sont de toute évidence ce qui porte Keleta-Mae à s’intéresser à la pièce de Sears.

1 The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God wrestles with a crisis in Black motherhood when the protagonist, Rainey’s, five-year-old daughter, Janie, dies of meningitis in her mother’s arms. Rainey, a medical doctor, has yet to forgive herself or God. She is the Black girl of the play’s title and her search for God marks the terrain of the play. Prior to Janie’s birth, Rainey and her husband, the local minister, had laid to rest at Negro Creek near their rural home in Holland Township, Ontario, Canada, the many tiny foetuses that they had conceived but who had never grown to full term. Inconsolable after Janie’s death, Rainey, now a childless mother, grapples with science and religion as she seeks to weave together an understanding of a Christian God that is constrained enough to appease her guilt and expansive enough to contain her sorrow. What emerges through these moments of condemnation and exploration is the verbal articulation of feelings in moments of spiritual crises; as I will show, these feelings are a critical site of meaning-making for Black women.1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

2 Sears’s play offers a generous opportunity for the careful contemplation of the intersections of Christianity, motherhood, and blackness in Canada—a topic hitherto unexamined in scholarship about Sears’s plays. Rainey’s search for God is a personal exploration of self in relation to each of these topics; similarly, this article draws from the analysis of self through the article’s incorporation of methodologies employed in autobiographical performance and autoethnographic research. Specifically, I map my examination of Sears’s play through my own body and experiences of Christianity, motherhood, and blackness in Canada. I do so in order to make visible Black cultural production2 and Black scholarship in Canada in ways that emphasize critical self-reflexivity and engender prose that is accessible to audiences within and beyond the academy. While this approach makes me not only the author of this article but also explicitly one of its primary subjects, it also complicates the distance between subject and researcher that traditionally exists in Canadian theatre scholarship.

3 Both autobiographical performance and autoethnographic research encourage a heightened level of critical self-reflexivity combined with the goal of telling one’s own story (Duncan; Behar; Ellis; McClaurin; Reed-Danahay; Heddon). While autobiographical performance is primarily concerned with the telling of one’s own story on stage and based in personal memories, autoethnographic research is a qualitative research methodology that contemplates the personal in wider social, political, and cultural contexts. Jenn Stephenson identifies interplays of fact and fiction as a central marker of autobiographical performance: “The past experience of the autobiographical author-subject is enacted again in the present. Events and impressions are brought forward and relived in my own words and with my own body. Tracing again the contours of my life, I am powerful—a small god in the heavens hovering above my story” (4). While I concur with Stephenson’s ascription of “power” to the act of autobiographical writing, I would argue that an author-subject’s capacity to experience herself as a “small god” (4) presupposes that she consistently experiences herself as a human being in the social interactions that constitute her everyday life. However, Canada’s participation in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the many, well-documented ways in which Black people in Canada continue to experience institutionalized anti-Black racism in schools, workplaces, public spaces, and the legal system create the material conditions in which displays of Black humanness are perpetually “surprising” to the dominant culture. As Katherine McKittrick writes:

Within the context of “systemic blacklessness,” an author-subject’s inclusion of her Black self might be read as less an experience of god-like status and more one that is akin to an assertion and documentation of her humanity in the landscape of Canadian life.

4 I have located myself at the nexus of theatre studies scholarship and theoretical explorations of the formation of racialized and gendered subjectivity in an effort to join the work of countless scholars who push the boundaries of academic scholarship beyond its historical roots as an imperialist, patriarchal, white supremacist project. Like these others, I push against the underrepresentation of Black cultural production in Canadian scholarship, as evidenced by the paucity of scholarly publications and conference programs on the topic. In other words, when I write about Djanet Sears’s The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God I endeavour, of course, to engage in substantive, rigorous scholarship but, my choice is also unequivocally informed by a commitment to a larger project of writing against the systemic exclusion, occlusion, and dehumanization of Black people in Canada and beyond (Fanon; Razack; Sears). As a Black girl growing up in Canada I quickly learned that mainstream society treated Black people as just outside of the human “norm” and thus not always privy to the historical, present, and future conceptual space that middle and upper class white people enjoyed, without qualification. Furthermore, as a Black post-secondary student I learned that canonized academic scholarship underrepresented, misrepresented, and omitted Black people in ways that contrasted starkly with what I was informally taught outside of the academy. To be clear, my articulation of my personal experiences and purview cannot, nor is it meant to, represent the experiences or worldviews of all Black women in Canada. Certainly the experiences of Black girls and Black women are as disparate as those of any other people and therefore, to read my scholarship as authoritative and conclusive would be as irresponsible as reading any scholarship as such. One of the key ways that this article seeks to differ itself from traditional Canadian scholarship is by foregrounding the explicit ways the scholar’s topic of inquiry intersects with her/his/their personal lived experience. To some extent, this article is about visibility and transparency—it is an effort to make equally visible the preoccupations of the scholar in her/his/their analysis of a subject matter—in this specific case it is the unambiguous articulation of why I care about Sears’s play, The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God.

5 My use of first personal singular and narrative based on personal experience in/as academic prose is unequivocally political; it is an assertion of my presence, my humanity, my love of stories, and my commitment to story readers and story listeners. I use the word “experience” to describe my memories of the various situations that have shaped my life— from corporeal encounters to influential stories shared by others in my communities. When I use personal narrative-based experiences in this article, I mean to further critical analysis and not to provide an example of a point that was previously made using traditional academic prose. In other words, the personal narrative is intended as its own moment of critical engagement and not as a creative illustration of a previously made point. I have used autobiographical performance as the basis of my artistic practice as a poet, spoken word artist, playwright, speech writer, creative writer, performer, and recording artist for more than thirty years and I have used autoethnography as an academic methodology for the past eight years. Deirdre Heddon cautions that while personal narrative can “bring hidden, denied or marginalized experiences into the spotlight” it can also engage in “problematic essentialising gestures; the construction of limiting identities; the reiteration of normative narratives; the erasure of ‘difference’ and issues of structural inequality, ownership, appropriation and exploitation” (157). Indeed personal narrative, as used in autobiographical performance and autoethnographic research, is rife with potential pitfalls but in my experience it can also facilitate meaningful engagement with audiences within and beyond the academy. My decision to pursue these methodologies, despite their shortcomings, is also informed by Black scholars such as Zora Neale Hurston and Frantz Fanon, who created rigorous scholarship that was deeply intertwined with personal narratives long before autoethnography, as a qualitative research methodology, was established. In that regard, personal narrative is a wellestablished mode of Black scholarship and, as such, my use of first person singular, personal narrative, and reliance on personal experience is a continuation of that rich intellectual lineage. When used by author-subjects with care and read by readers who are versed in its limitations, I think an emphasis on the self in autobiographical performance and autoethnographic methodology can be what Stephenson described: “a uniquely powerful political act” (4). When these two modes of inquiry are combined with a close reading of a play, as is the case in this article, multiple forms of scholarly engagement (autobiographical performance, autoethnographic research, and play analysis) are illuminated.

Questioning God

6 Rainey’s encounters with death deeply inform her relationship with God: she was a second year seminary college student when her stepmother, Martha, became ill. “I told God, bring her out of this please, and I’ll do anything. Anything! And when she…. When she died, I thought…. I thought, fine…. Fine…. You’re just going to have to do it yourself” (Sears 85). For Rainey that meant a transfer out of Seminary College and into medical school because a doctor “could really do something…. Could really save souls” (25). But when her daughter died in her arms from a bout of meningitis that Rainey was unable to diagnose or treat, despite her medical training, Rainey subsequently left her practice and entered graduate studies as a Master’s student in the Department of Science and Religion. In the present tense of the world of the play, Rainey is in the midst of applying to do her doctoral studies in the afore-mentioned department where she intends to write a thesis called “The Death of God and Angels,” which she describes as a “challenge to the supposition of a JudeoChristian God” (28). What is remarkable in Sears’s construction of Rainey is not so much her profound questioning of the relationship between death and an omniscient being but more so the lengths to which Rainey goes in pursuit of satisfactory answers, particularly in light of the central conundrum she identifies: “It’s not that I don’t believe in God. The problem is... I do” (73).

7 Rainey’s relentless pursuit of the reconciliation of her “problem” with her lived experiences parallels efforts waged by some feminist and womanist Christians in their attempts to reconcile a historically androcentric religion with feminism and/or womanism (Daly; Schüssler; Cannon; Johnson; Carr; Wiggins; West). Feminist and womanist theologians have long been invested in the deep interrogation of the history and future possibilities of Christianity. This field of inquiry and praxis is vast: from arguments citing Christianity’s inherent inability to be a feminist project (Daly), to explorations of feminist spiritual nomenclature (Johnson), to the capacity of lay women to influence Christian faith (Wiggins), to womanist strategies for feminist interventions in Black churches (Cannon). The vastness of the field suggests, to me, the robust effort required to recuperate Christianity from its historical political agendas.

8 I come to The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God full of my own stuff, mostly my own search for God. I was a Black girl in Canada raised by Christians to be a Christian; but, I was never confirmed, never accepted the vows my parents’ took on my behalf at my baptism. I felt conflicted by dominant culture’s ascription of whiteness and maleness to God. I was also deeply concerned by the various historical points at which Christianity and the Transatlantic Slave Trade intersect—the former, of course, used to sustain the latter by beneficiaries of the slave trade and used to rebel against it by those oppressed by it. I was raised to believe in God and most days I think I do. I have long used the words God, Yahweh, Yemoya, universe, energy, life force, Jah, and Allah interchangeably, under the premise that all are gateways into a deepened experience of self in relation with all aspects of the world. My faith practice, while based in Christianity, aspires to be flexible. I am fascinated by The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God in part because Sears creates a protagonist in search of what she already believes—that God exists (73)—and so the search then is not so much for God as it is for the acceptance of the painful and debilitating feelings that life’s harsh realities can evoke.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Black Mothering

9 In 2010, for the first time, what I had long cherished as my fluid Black feminist faith began to feel reckless and unstable. I was pregnant with the first child I intended to carry to term. I felt pressure to not only play the role of Black mother well, but to excel at it. In “The Meaning of Motherhood in Black Culture and Black Mother-Daughter Relationships,” Patricia Collins identifies key issues in Black mothering specifically for African-American women, but with resonance for Black Canadian women as well:

As my pregnancy advanced and my status of Black mother came closer into view, the responsibility of shaping the formative years of my child’s cosmology weighed on me like the kilos affixing themselves to my body. I thought that pending Black motherhood signalled a need to bring about the culmination of my decades of spiritual exploration into a preferably religious and ideally Christian practice that I could clearly articulate in words and deeds. I felt that my questioning of self suggested weakness and ineptitude. As Shirley A. Hill notes:

With uterus extended far enough to render the sight of toes impossible I thought, “If ever there was a moment to be confirmed as a Christian, surely, this is it.” But, I knew I could not say the vows and perform the ritual, despite my growing anxieties or the important theoretical and practical work that Black and/or feminist theologians have done to re-historicize and re-imagine God (Daly; Schüssler; Johnson; Carr; Wiggins). My faith was firmly tested when confronted with a profound shift in the relationship between my self and Black mothering and similarly, the death of Rainey’s stepmother profoundly tests Rainey’s faith as she finds herself confronted with a profound shift in her sense of self vis a vis Black mothering.

10 Rainey’s beloved stepmother was unable to have children biologically, became Rainey’s stepmother when Rainey was two years old and, according to Rainey, raised her “like a vain woman tends her best feature” (52). Rainey was well mothered. The death of her stepmother signalled a change in Rainey’s relationship with Christianity—she no longer viewed theological training in a monotheistic religion as the most effective way to use her talents in service of others. She shifted her focus to the possibilities of science. Years later, with Janie dying in her arms, Rainey returned fervently to Judeo-Christian prayer, promising her God that she would do anything and imploring her God to take her instead (6). Rainey’s life has been shaped by the death of loved ones—her biological mother, her stepmother, her daughter Janie, her numerous lost foetuses and, as she discovers in the play, the imminent death of her father Abendigo.

11 I use the word “lost” to describe the relationship between Rainey and the foetuses that were not born alive, with much hesitation. I use “lost” in an effort to be attentive to Rainey’s articulation of her own experiences. In The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God Rainey says to her, at that point estranged, husband, “You know how much I wanted babies, our babies. And when we kept losing.... I kept losing.... Then Janie.... She stayed” (87). Though mindful of Rainey’s perspective, I will also register my own. I find the use of the words “lost” and “losing” to describe foetuses that do not make it to the world alive a hurtful assignment of blame to women who are forced to face the fact that the foetus they carried will not become a living human being. The Black and non-Black women I know and know of who have gone through the experience of a foetus dying in their uterus or a baby dying upon delivery did not misplace the contents of their wombs. Quite the contrary, in most instances these women were hyperaware and attentive to the foetus attempting to come to life in their bodies. To suggest that they lost these foetuses is to imply that these women were careless and to assign blame to them for biological and societal factors that are often beyond their control. My concerns with the popular nomenclature of women losing or even miscarrying babies is not meant to minimize the tremendous sense of loss that many of these women experience. I raise my concerns in an effort to be attentive to the painful ways that these women not only have to cope with unfulfilled expectations of the arrival of new life, but are also held linguistically accountable for the unrealized life of foetuses and babies they had hoped to bring into the world. However, it is not only the personal experience of death that Rainey grapples with, but also society’s increasing inability to adequately prepare for and deal with death, as evidenced by the individual decisions of Rainey’s father and husband to speak little of Janie’s death in Rainey’s presence. Howard M. Spiro argues that “Death is as common as birth, but it went into hiding in our twentieth-century hospitals [. . .]. Death is no longer destiny, but the failure of doctors, written nowhere in God’s plan. Death can be repelled, repulsed almost forever—a disease that doctors should be able to cure” (xv).

12 During my pregnancy in 2010 I was terrified of being unable to carry a child to term, having a stillborn, having a miscarriage, or having a child who was born outside of the narrow scope of what is accepted as normal and healthy. I prayed, lit candles, and meditated. And as I grappled fearfully with all of the seemingly disastrous ways my pregnancy could conclude, healer and midwife Dawn Bramadat told me, “Every birth is perfect.” Within Bramadat’s worldview, whatever form a foetus takes upon coming to this world is its perfect manifestation. In the case of my child, Bramadat’s worldview shifted the responsibility I felt from needing to bring a foetus to full-term and produce a healthy, normal baby to needing to identify the sources of my expectations and re-imagine my notions of perfection.

13 In “Moon Woman,” Afua Cooper describes her three experiences of childbirth in Canada. The first, in the early 1980s when she was a twenty-three year-old newly arrived Black immigrant from Jamaica, the second and third in the mid-1990s when she was a doctoral student at the University of Toronto studying Canadian history. Cooper makes interesting comparisons between the space children occupy in Jamaican society and Canadian society. In the Jamaica of Cooper’s childhood and early adulthood, children were seen as natural additions to the community, they were “gifts from God” (68) that people loved and folded into the fabric of everyday life. Canada felt different to Cooper: “I detected that people did not like children. They tolerated them,” waited until mortgages were almost paid, money saved and careers firmly established before having them, and then checked the birth of each child off of their to do list (68). Certainly Cooper’s assessments are not true for all Jamaicans or Canadians, but her description of the latter resonates deeply with my own experience and arguably Rainey’s as well. Her father is a judge who started out as a porter on the railways, she comes from a middle to upper-middle class family in Canada, she is a professional who pursues post-secondary education when she decides to change careers. I strongly suspect that she would have paid some attention to her career trajectory when she and her husband were attempting to conceive. Granted, their numerous unsuccessful attempts to bring a foetus to full term may have shifted the extent of their planning, I still think it is likely that Rainey would have been cognizant of the implications of the timing of the birth of a child.

14 Rainey was born in the urban centre of Toronto and raised about 140 km north of the city in the bush land of Holland Township. Her father’s people are from there and own land near Negro Creek. Her paternal great-great-great-grandfather Juma Moore was deeded the land, Ojibway territory, for fighting for the British in the war of 1812. Her great grandmother Lorraine Johnson, for whom Rainey is named, died performing the annual ritual of cleansing Juma Moore’s uniform in Negro Creek. Unlike many of us in the African Diaspora, Rainey’s lineage on her father’s side can be traced with certainty across multiple generations, which may very well have exacerbated the feelings she describes of her lineage dying with each foetus lost and most certainly with her five-year-old daughter’s death (65).

15 In her afore-mentioned article, Collins describes the particularities of Black motherdaughter relationships, especially the dilemma that Black mothers’ of daughters face:

Rainey describes the sensation of being hugged around her waist by her daughter who held her so tightly that Rainey thought she was trying to get back inside of her: “She was mine,” Rainey says (87). Christianity teaches that all people belong to God. Rainey’s experience taught her something different. Indeed, the intersections of Black mother-daughter relationships, and Christianity are numerous.

16 In 2010 I stood in the kitchen of a friend of the family’s home talking about Christianity while my three-month-old daughter slept in a room nearby. When my friend asked me if I was a Christian and I said “No” our conversation shifted and deepened. She is a Christian, her husband is a Christian, and they are raising their children as Christians. She asked me a slew of reasonable questions: “What will you teach your daughter without a creation story or scripture to guide her life? How will you communicate your beliefs to her?” And I thought “That’s the problem. That’s the challenge. I don’t have a spiritual community that gathers routinely, that performs rituals or that shares a wide range of beliefs about spirituality.” I grew up with all of that. I grew up in a Protestant Christian denomination called the United Church of Canada, in a liberal, progressive, multi-ethnic church that was the site of much community organizing. My answer to my friend’s questions felt painfully inadequate that evening. I felt like I had failed, yet again, to reach a benchmark of Black motherhood and though Collins’s article does not link the role of religion or spirituality to one’s status as Black mother, experience has taught me that they are powerfully linked. It is not a coincidence that the pews, chairs, and benches of Black churches in North America are filled with Black women, Black mothers, and their Black children. As a Black mother, I feel that the unspoken community expectation is that I will teach my child about God and at the very least instil the fear of God in her.

17 In the months that followed that kitchen conversation I wished I had had some lucid answer that thoughtfully articulated some great theory, theology, or spirituality that I had already begun to teach my daughter. Instead, I was left with more unanswered questions: How do I teach my daughter that religion is a worldview? How do I teach her that each religion has its own worldview? How do I teach her about atheism and its worldview? How do I teach her my own faith practice—one that is undeniably deeply underpinned by JudeoChristianity? How do I teach her the conundrum that I face and that Rainey verbalizes with such clarity, “Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that I don’t believe in God. The problem is... I do” (73). The problem is that I do too. Be it God, Yemoya, Jah, Allah, Yahweh, universe, energy, life force... most days I believe and feel the presence of some kind of connection with others, with nature, with life beyond the material.

Blackness

18 The epigraph of Sears’s The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God is comprised of three quotes that appear in the published texts and on rehearsal scripts, but are unspoken in stage productions. The first quote asserts that the combination of natural elements (earth, soil, wind, and rain) and a human-made item (the drum) are central to African Diasporic experiences in the Americas, while the second is a brief and powerful reminder of the JudeoChristian story of Job and the immense suffering he endured. Meanwhile the third quote engages in a philosophical debate about some of the contradictions inherent in the JudeoChristian belief system.

When read together, these quotes articulate the contradictory and complimentary modes of theology that Rainey experiences—a theology that Leslie Sanders describes as “complex” “ambivalent,” and “deeply spiritual” (121). A theology that is deeply tied to, and informed by Rainey’s: seminary college studies and graduate research; gendered and racialized experiences of Black mothering as a both a child and mother; and ancestral ties to the land of Holland Township and the water that courses through Negro Creek. Like the biblical character Job, Rainey has undoubtedly experienced suffering but, unlike him, her faith has waivered, faltered, and shifted.

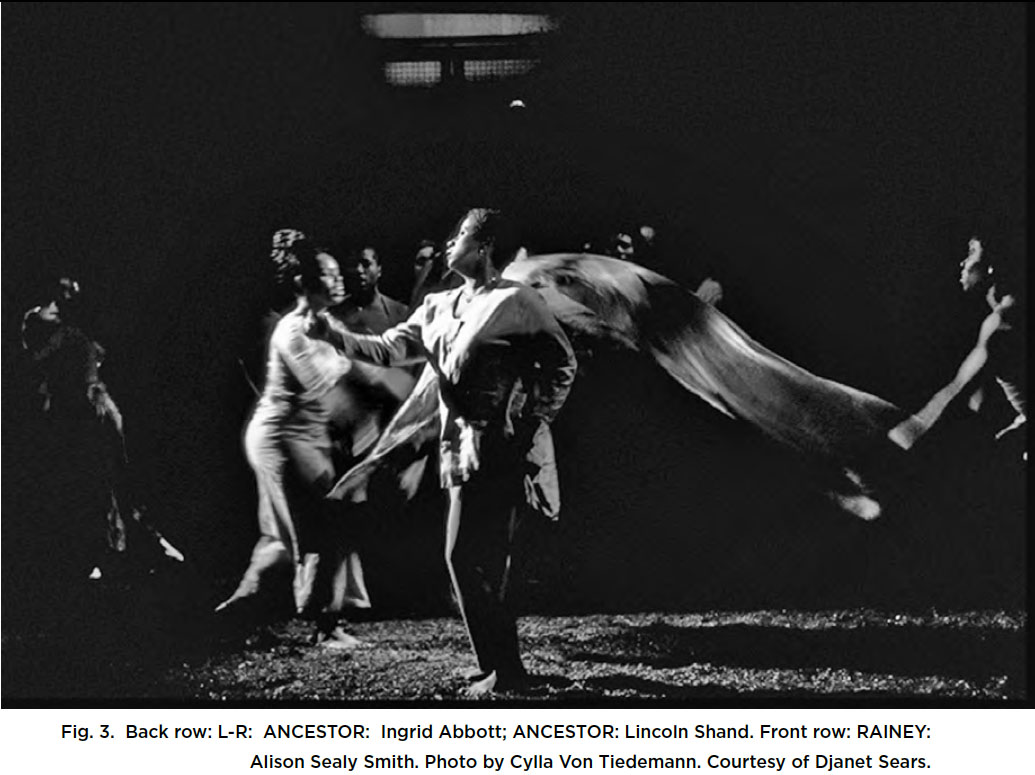

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

19 In a conversation with Djanet Sears I asked her about the above quotes and the juxtaposition of the spectrum of beliefs that they each cover within the context of The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God. Sears describes the first quote as an embodiment of humanity, the second as a signaling of God as emotive, and the third as the thoughtful articulation of a struggle for and with God (2011):

The theological trilogy that is most often accepted and rehearsed in North American contexts is that of mind, body, and spirit. The definition of spirit that I am signalling here is that of a “being or intelligence conceived as distinct from, or independent of, anything physical or material” (“spirit”). In the theology that Sears articulates above, however, not only is spirit separated from mind and body, but it is replaced by feelings. Sears’s emphasis on feelings as integral to a robust articulation of humanity occurs not only through her prominent placement of the three quotes in the epigraph, but also through Rainey’s lived experience of mothering and being mothered. Rainey’s verbal articulation of her feelings—even when incomplete—permits them to function as critical sites of knowledge and wisdom born of her experience. Certainly, one of the many important things that Black feminist literature has asserted is that experience is central to understanding Black womanhood (Lorde; Collins; Madison; Dicker/sun).

RAINEY pulls her hand away.

MICHAEL Janie died almost three years ago, Rain. It’s time. We’ll do it together.

RAINEY I can’t. She’s there…. It’s because…. I can’t, it’s—

(Sears 85)

(Sears 87)

In The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God, Rainey constantly works to verbalize her feelings to the audience, to herself, to God, to her husband, to her father, and to her larger community. With this dramatic choice, Sears disrupts the role of the strong Black woman, bearer of all things whose personal pains are seldom voiced in public. Rainey does not protect her family—quite the opposite—Rainey is a female Black protagonist who is not strong in conventional ways and does not portray conventional images of the strong Black woman. We learn from Michael (her estranged husband) that she did not look at their daughter’s body in the casket at the funeral, that she did not attend her burial, and that Rainey had never visited the gravesite. She subsequently has an affair, leaves her medical practice, and files for a divorce. While each of these individual acts are understandable within the context of arresting grief that the death of a child can cause a parent, it is nonetheless remarkable, within the context of the canon of Black theatre in North America, that Sears ascribes each of these acts to the Black female protagonist. We, the readers and viewers of the play, find out that Rainey’s family has protected her—her father, her estranged husband, her estranged church community—all of these people have protected Rainey ever since Janie’s death. For example, Rainey’s father, Abendigo, only tells her that he is terminally ill with heart complications and on the verge of dying after he collapses in front of her. She then learns that Michael and all of her father’s friends had known all along of his illness but, Michael tells Rainey, “[Your dad] didn’t tell you because he’s so busy protecting you. We’re all so busy protecting you” (Sears 64).

20 When I read the play, prior to becoming a mother, I was frustrated by Sears’s portrayal of Rainey on the page in ways that I was not when I watched it as a live performance. Reading the play, I found myself wanting Rainey to stop repeating words and indulging in incomplete sentences.

RAINEY And I am a doctor, Michael. She had all the symptoms. It was textbook. It was textbook. It’s why, it’s why…. It’s why I…. When Martha got sick… I prayed. I really prayed, Michael. I told him. I told God, bring her out of this please, and I’ll do anything. Anything! And when she…. When she died, I thought…. I thought, fine…. Fine….

(Sears 85)

I wanted Rainey to say what she had to say. Janie’s death occurs in the first scene of the play and soon thereafter we learn that three years have passed and still Rainey’s feelings are raw. To be clear, it is not the visceral nature of Rainey’s articulation of her grief-stricken feelings that unearthed me but the fact that she repeated her feelings about her daughter’s death, loss, and her personal responsibility to the audience and Michael often, as though she were stuck. I was frustrated by Rainey’s insistence on verbalizing her feelings and taking up the necessary space to do so. I wanted her to be high functioning, to present to her community a composed and self-possessed Black woman who could manage the reality of death better. But Sears gives Rainey space. Ample room to feel numb, frustrated, empty, lost… to feel whatever the moment evokes and Sears gives Rainey ample time to verbalize her feelings in fragmented or lucid form. Sears creates space for Rainey to experience the wanderings of her mind, space to describe what her body experiences in its efforts to become and remain a mother, and space to feel the nuances of her experiences. This is a powerful intervention; one that I could only begin to grasp upon reading the play numerous times. It was then that I slowly began to feel refreshed by Rainey’s unapologetic insistence on taking up space to feel and to piece together language that verbalized her feelings—space that is rarely allotted to Black woman in general and Black mothers in particular.

21 The tradition of “feelings” as a prominent mode of meaning-making in Black mothering is perhaps no more evident than in the scholarship of Black, lesbian, feminist, poet, and mother Audre Lorde:

In this passage, Lorde identifies women’s attentiveness to and cultivation of “feelings” as radical interventions in an oppressive society. Lorde then, informatively, links “feelings” with the practice of experiencing the minutiae of everyday life and thus she indicates that feelings and reality are deeply intertwined. Writing within the context of female African American theatre and film practitioners, with relevance for Black Canadian female artists as well, Lisa M. Anderson asserts that realism in theatre and film can confront mainstream iconographies of blackness. In particular, Anderson argues that, “these women [artists] formulate images that more accurately depict blacks, particularly black women. These artists pave the way for the development of the black woman warrior, the quintessential image of visual resistance” (119). Upon further reflections on the play and on myself, I understood that what I had first identified as feelings of frustration with Rainey where feelings that were far more akin to envy—I was jealous, I too wanted space. I too wanted to feel that I could continue to explore theology without absorbing external pressures to solidify my ideas because I had entered the new role of Black mother. I wanted to be the “black woman warrior” that Sears makes possible through the character of Rainey.

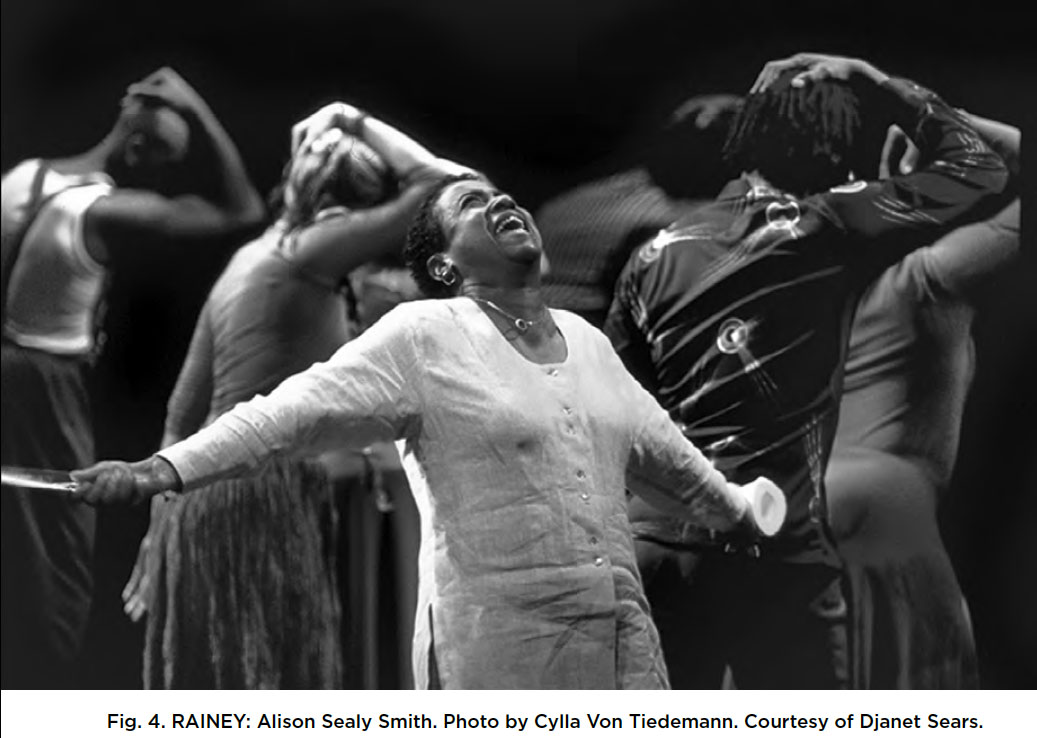

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

22 Sears’s emphasis on the articulation of difficult feelings permeates The Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God. This article contends that the assertion of these feelings as equal to mind and body is a Black feminist intervention that locates spirit elsewhere—not intrinsically tied to the mind and the body, nor bound by their constraints. This is a particularly important intervention given the still-lingering insistence within dominant Western discourse on using the mind-body-spirit paradigm to ascribe value to human beings. For those of us who inhabit minds and bodies subjected to various forms of violence that seek to simultaneously commodify and devalue us, the insertion of feelings and the displacement of spirit in the mind-body-spirit paradigm is a Black feminist and womanist theology that facilitates the capacity to imagine spirituality, religion, and cosmology in productive ways.

Conclusion: piecing together possibilities

23 Elizabeth Brown-Guillory concludes that:

Sears’s play makes abundantly clear that this “struggle” is not only about land, anti-black racism, sexism, and societal constraints on Black mothering. The “struggle” is also about the creation of space for Rainey, a Black Canadian woman “warrior,” to feel the breadth of her “complex,” “ambivalent,” and “deeply spiritual” theology.

24 I held a blessing ceremony at my home when my daughter was four months old. There was water, a candle, a bell, a book, an orchid blossom, a rock, rose-of-sharon seeds, and no religious vows. Instead my community promised to: support my first born on her spiritual journey, encourage her to fulfill her life’s purpose, and guide her towards a life of integrity. I thanked my daughter for choosing me to be one of her parents and then I promised to do my best. In my Black feminist, womanist theology, “my best” is a spiritual practice in which I strive to give myself, daily, space to feel and to verbalize my feelings especially about what it means to inhabit a body read as female and Black in Canada with a mind enriched by the nuances of that and other factors that comprise my individual experience.