Articles

Techniques of Making Public:

The Sensorium Through Eating and Walking

In this article, Doonan analyzes two performances presented by the SensoriuM, a collaborative participatory art platform in Montreal, Quebec. In doing so, she shows how the SensoriuM makes public through curatorial and dramaturgical practice. By making public, she refers to the active translation of materiality into representational forms, and also to the assembling of humans and non-humans in participatory performance. Doonan describes the concrete audiences bounded by the live events, as well as the more amorphous and immeasurable publics that are brought into being through the circulation of texts, including digital images, videos, and oral presentations. Drawing from science and technology studies and more-than-human geographies, she explores “epistemic publics,” or the animal, organic and machinic configurations that come into being in the process of creating (objects of) knowledge. Doonan analyzes two specific performances: Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour and Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor to show how these processes of making public are enacted. Both performances use food as a medium to complicate and undo binaries of public/private, self/other, domestic/wild, depressed/revitalized. The meanings and uses of particular places are brought into question through embodied and symbolic means. Doonan argues that these performances work to de-design the city by queering its dominant discourses and creating intimate spaces of exchange.

Dans cette contribution, Doonan analyse deux performances du SensoriuM, une plateforme collective d’art participatif à Montréal, afin de montrer comment le SensoriuM façonne son public au moyen de pratiques curatoriales et dramaturgiques. Pour Doonan, façonner son public signifie une traduction active de matérialités en formes représentationnelles et l’assemblage d’humains et de non-humains dans des spectacles participatifs. Doonan décrit les publics concrets que délimitent les événements en direct, de même que les publics plus amorphes et impossibles à mesurer qui naissent grâce à la circulation de textes, incluant les images numériques, les vidéos et les présentations orales. S’inspirant des sciences et des technologies ainsi que des géographies plus qu’humaines, elle explore le concept des « publics épistémiques », ces configurations animales, organiques ou machiniques issues du processus de création (d’objets) du savoir. Par l’analyse de deux productions, Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour et Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor, Doonan montre comment ces processus sont mis en œuvre. Les deux prestations se servent de la nourriture comme médium pour problématiser et détruire une série de binaires : public/privé, soi/autre, indigène/sauvage, en déclin/revitalisé. La signification et le recours à des lieux spécifiques sont remis en question par des moyens concrets et symboliques. Doonan fait valoir que ces prestations opèrent une dé-conception de la ville en injectant une dimension « queer » aux discours dominants et en créant des lieux d’échange intimes.

– Vito Acconci, “Public Space in a Private Time”

Being and Knowing Publics

1 Artist and writer Vito Acconci describes the operations of public art as “superfluous” as these “replicate what’s already there and make it proliferate like a disease” (915). His lush descriptions of public art building up “like a wart,” attaching itself “like a leech,” or digging out “like a wound” serve as rich depictions for an artistic–academic practice that aims to infect official narratives (915). His essay “Public Space in a Private Time” is best understood within its historical and geographic contexts, as written by a New York City artist, informed by the AIDS crisis, by the 1980s-1990s culture wars, and by emerging “Queer Theory.” In this manifesto on public art, Acconci advocates a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) aesthetic of taking “what’s already there”—that is, the planned elements of civic spaces—and remixing them. This mash-up process involves selecting, reframing, and recombining to make connections between seemingly disparate elements in order to undermine the strict use-values that have been ascribed to so-called “public” spaces. If cities are designed to produce docile subjects of capital, Acconci’s view of public art is to encourage dis-identification by disassembling and recomposing that design. Or, in Acconci’s words: “The function of public art is to de-design” (915).

2 “What’s already there” in civic space refers to what is taken for granted—what usually goes unnoticed and unchallenged. When I refer to a practice that aims to infect official narratives, I am talking about dismantling the fictions of ownership and appropriate behaviour that govern corporate civic space. It is not a stable built environment that structures behaviours in urban spaces. Subjectivities and spaces are co-produced through both performance and discourse. For the purposes of this article, I want to show that there are dominant corporate and municipal narrative forms (performed and symbolic representations) that structure experiences and understandings of Montreal, and that these can be appropriated for alternate ends. Perhaps the two most prominent forms are the tour and the tasting. These two narrative forms are part of “what’s already there”—programmed, corporate culture. To play on the double meaning of “sampling”—relevant for food and for DIY culture—it is possible to take from this culture and replicate unfaithfully in a way that offers “a rethinking of both the perverse and the normal” (Berlant and Warner, “What Does” 345). In keeping with Acconci’s manifesto, this article proposes that public art should work in opposition to the rational city plan, which assigns limited use values to each site and pre-determines relations between its users. I advocate for a public art that encourages intimacy, so Acconci’s use of skin metaphors to describe city surfaces is apt since it reveals these as porous, flexible, vulnerable, and lively.

3 I begin with this particular piece of writing by Acconci because in what follows, I draw similar affinities between the city and the body as contiguous, contingent, and contested sites. To do so, I describe a performance art project that mobilizes assemblages of human and non-human bodies through curatorial-dramaturgical practice,1with the effect of complicating holistic narratives of place—or discourse that represents people and places as unified, fixed, and homogeneous. In this piece, I am thinking about making public as a kind of queering in the sense of creating intimate connections where distance and abstraction predominate. Writing also in the wake of the AIDS crisis, critics Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner define queer commentary as that which challenges fictions of a heteronormative mainstream. They note that: “It is no accident that queer commentary—on mass media, on texts of all kinds, on discourse environments from science to camp—has emerged at a time when United States culture increasingly fetishizes the normal. A fantasized mainstream has been invested with normative force by leaders of both major political parties” (“What Does” 345). This kind of queering involves, in part, metabolizing the abject, bringing it back into what we call our own bodies. In the performances I discuss below, food is used as a medium to complicate and undo binaries of public/private, self/other, domestic/wild, depressed/revitalized. The meanings and uses of particular places are brought into question through embodied and symbolic means. The performances I describe are examples of public art that work to de-design the city by queering its dominant discourses.

A Curatorial-Dramaturgical Public Art

4 Since 2011, a series of small project grants from Concordia University in Montreal has made it possible for me to create a collaborative performance art project called the SensoriuM. I founded the SensoriuM with the intention of activating publics in and around the city. As a newcomer to Montreal, this was a way for me to learn with others about the city through mapping its food landscapes, which are also socio–political scenes, or situations. Any situation that is organized around food brings near and distant actors (humans and non-humans) into uneven power relationships. One goal of this project is to encourage awareness of these relationships. I work collaboratively with an ongoing series of artists and community members to create participatory performance events in the form of tours and tastings. These performances always involve eating. The tone is provocative and playful, with the goal of appealing to audiences through the senses, thereby assembling groups that would likely not interact otherwise. Through tours and tastings led by artists, participants are engaged viscerally, meaning through their entire sensorium—mind and body. Examples of events include a human cheese tasting in a bar and a visit to a modern dairy farm, with the tour bus transformed into a mobile installation space. Sensorial engagement of audiences and discussion are equally emphasized. My role in the SensoriuM can be described as curatorial and dramaturgical. I am informed by my training in the visual arts, while I also draw from collaborative theatrical strategies. Each year, I select key actors (various types of performing and visual artists), research local contexts, and outline a series of performances for the upcoming season. I secure funding, arrange venues, and produce promotional materials. This is a relational practice, in which connections are made between organic and inorganic bodies—food, humans, computers, buildings, streets, trees, and so on.

5 Like the practice of “relational aesthetics” defined by curator Nicholas Bourriaud in his landmark 1998 book of that name, SensoriuM performances underscore relationships, but unlike much of the art he describes, the “social” here is understood as constituted through more-than-human networks.2This means taking into account complex configurations such as “neighbourhoods,” “canals,” “abandoned sites,” and “fallow land” that are mobilized in the creation of “participatory performance.” The works that Bourriaud curates have been critiqued for disregarding local conditions.3They operate within the circuits of global art markets such as high profile biennales and art institutions, thus contradicting his antiinstitutional claims. According to art critic Claire Bishop, within these circuits, so-called “immaterial” works are reified and the communities they purport to generate are restricted to “the in crowd.” Bishop stresses the importance of evaluating the kinds of publics being produced through relational art, and the quality of participation involved. Hence, she argues, simply creating convivial situations is not enough. The main point I would like to stress from her critique is that antagonism is essential to any democratic public. By “antagonism,” Bishop does not refer to aggression, resentment or violence, but rather (as others have also shown— see Deutsche; Mouffe; Laclau) divergence. The maintenance of conflicting perspectives on an issue is essential to any democracy, after all. According to this view, the measure of successful relational art should be its ability to preserve conflicting and incommensurable perspectives at once. Relationality also stresses contingency and flux. Berlant and Warner note that queer commentary “allows a lot of unpredictability in the culture it brings into being” (“What Does” 344). The assemblages I will discuss are partial and provisional examples—in no way am I trying to describe a public that is mobilized around the SensoriuM. Openness, unpredictability, and divergence are crucial for the possibility of what Acconci calls “minority reports” to emerge.

6 Furthermore, I would like to make a distinction here from Bourriaud’s notion of participation. While Bourriaud purportedly attempts to dis-identify participants from consumers, the SensoriuM takes consumption as its point of departure. It starts with the premise that we are all consumers. The proposal then is to consider together what it means to consume, and how to negotiate that consumption. Storytelling is central to this process. Representations of places structure our ideas and experiences of them. Advertisements, development campaigns, news articles, and city tours often encourage unreflexive consumption of places. Complicating these representations opens possibilities for creative, divergent uses of these places.

7 This article is an attempt to explain how, by putting into relation certain actors (both human and non-human) in particular places, the SensoriuM makes public. I mean “public” here in two of the senses described by literary critic and theorist Michael Warner in his “Publics and Counterpublics.” First, I refer to the concrete audiences bounded by the live events presented through this project. Second, I focus on the more amorphous and immeasurable publics that “come into being only in relation to texts and their circulation— like the public of this article” (“Publics” 413). “Texts” in this context can also take the form of digital images, videos, and oral presentations. Furthermore, drawing from science and technology studies and more-than-human geographies, I explore “epistemic publics,” meaning the animal, organic, and machinic configurations that come into being in the process of creating (objects of) knowledge. As scholars such as Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, and Sarah Whatmore point out, the processes of identifying, selecting, and editing objects of study are invested with power. Here, we can think about places too as “epistemic objects.” To put it simply: that one neighbourhood comes to be known as a hipster enclave while another is cast as a depressed post-industrial site is largely a result of interactions between materiality, groups of people, and the tools they use to create representations that depict the places in this way. Making public through performance art, then, is about manifesting the contested nature of places and divergent understandings of these places through embodied experience and symbolic means.

Epistemic Objects/Epistemic Publics: Weeds & Foragers

8 With these three understandings of “public”—as bounded by an event, as circulating through texts and intertextuality, and as constituted through epistemic objects—I will attempt to describe the work of the SensoriuM. At the time of writing, the SensoriuM has presented fourteen performances. I will focus on two here: Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour and Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor, performed in the summer and fall of 2013 respectively.

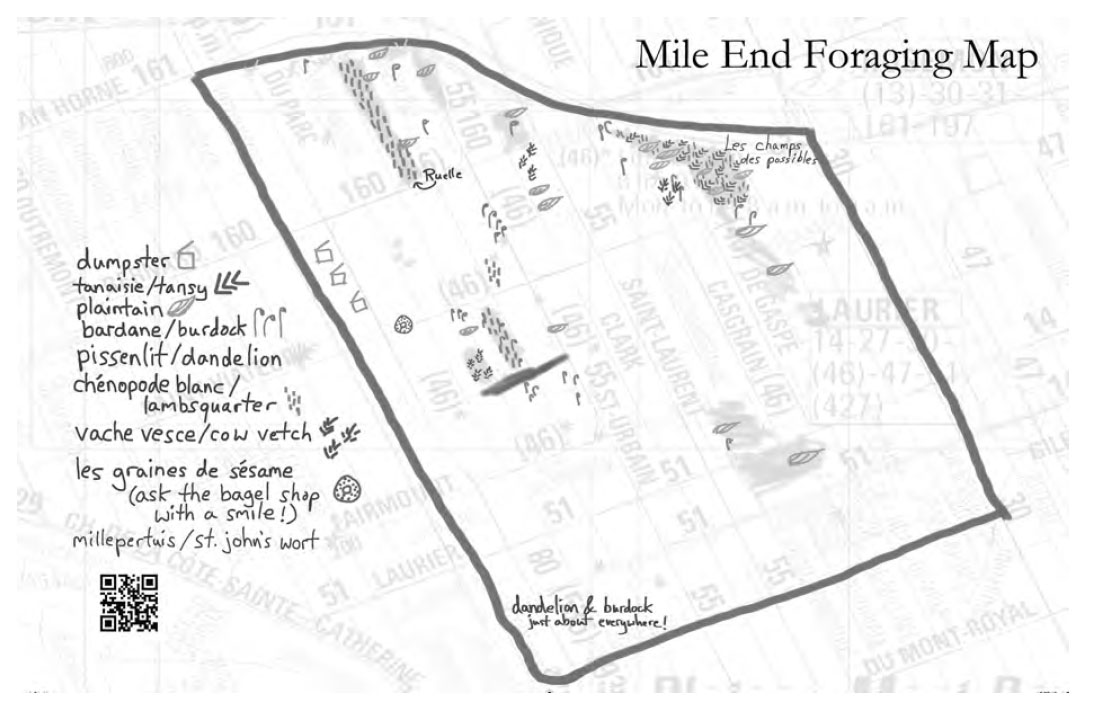

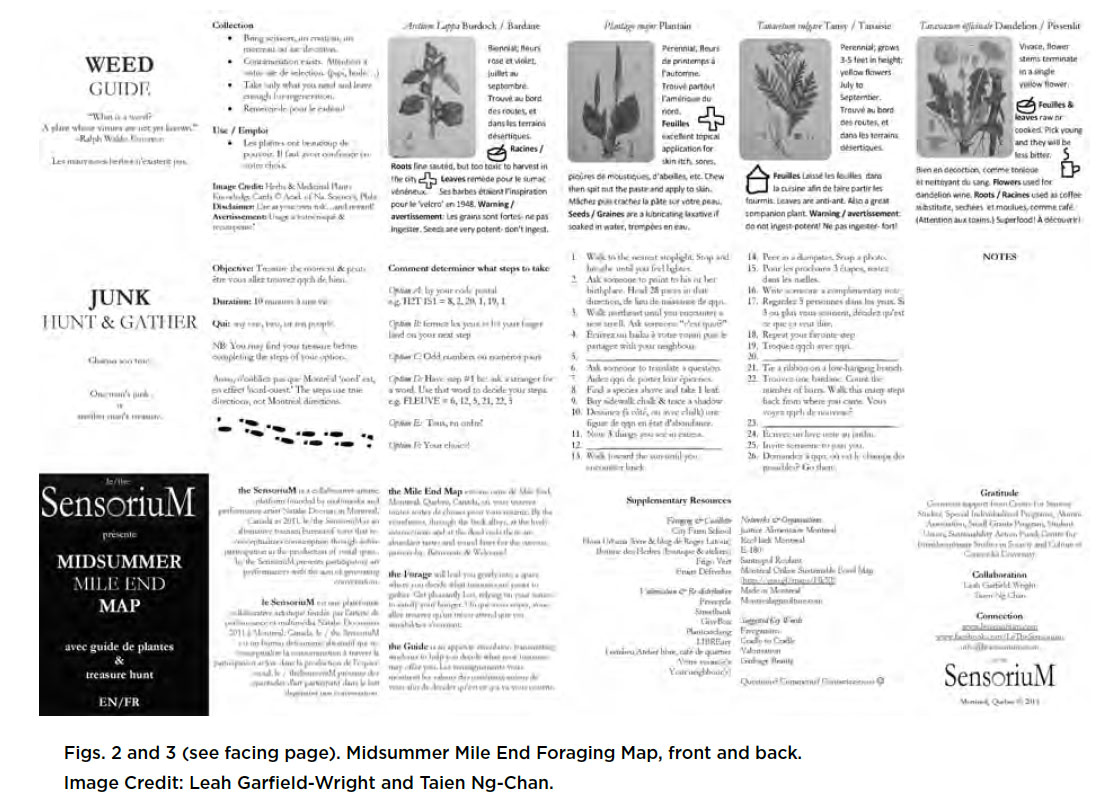

9 Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour was pragmatically named for its scheduling in the middle of summer, on 20 July, in the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal, and for its focus on foraging or finding food that is available at that time of year. Its aim was to investigate ways of eating for free in one of the city’s more affluent areas. The tour itself took people to back alley weeds and gardens, to a famous bagel shop, to private cherry trees and Saskatoon berry bushes, to a series of well-stocked dumpsters, and to Les Champs des Possibles—a fallow field that is a contested site filled with guerrilla gardens, science experiments and temporary artworks. During the tour, participants were also provided with “Midsummer Mile End Foraging Maps,” which include the locations of various free foods, a weed guide, a series of walking games, and supplementary resources for further research.

10 Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour, was led by artist Taien Ng-Chan and urban forager Leah Garfield–Wright and was developed through a series of research walks. This tour and its accompanying publication were offered to the public free of charge and advertised through the SensoriuM’s mailing list, Facebook, website, and Twitter, as well as the Concordia Greenhouse newsletter, posters, and postcards distributed within the neighbourhood. The research phase of the tour was open to the public at large. This involved a series of exploratory walks through the neighbourhood. In advance of meeting, optional readings were circulated through Facebook by Garfield-Wright, Ng-Chan, and myself. These included: “Theory of the Dérive,” by post-WWII socialist artist Guy Debord; “Freegan Philosophy” by freegan.info—an initiative of the Activism Center at Wetlands Preserve in New York City; “Get out of the groove,” by reporter Catherine De Lange for New Scientist; and “Hashish in Marseille,” by Marxist philosopher and critical theorist Walter Benjamin. The topics covered in these texts include: “the drift” in walking—an art historical technique used to resist consumerist tendencies to move productively and efficiently through space; smartphone apps that generate inefficient paths and serendipitous moments in navigating from one place to another; and freeganism, or consuming without spending money.

11 While Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour invited an open, undetermined public to participate in its research phase, it is evident from the choice of readings (even though these were optional) that its public was to some extent inferred. The readings are leftist, deviant, marginal, artistic, technological, and political in nature. Therefore, as much as the SensoriuM may attempt to mobilize a diverse and heterogeneous public, this attempt is constrained discursively. As Warner argues:

In other words, every speech, text or performance addresses particular demographics implicitly. Accessibility and appeal are constrained by the language and aesthetics employed to advertise the event, and the places where these notices are distributed. The notion of opening a performance and its production to diverse audiences is necessarily limited by all of the choices listed by Warner, and more. In the case of Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour, I acknowledge that as much as participation from a heterogeneous public was the goal, the various aesthetic and pragmatic choices made along the way limited the composition of this public. Presumably the selection of articles appeals to an arty, intellectual, lefty, activist audience. We displayed and circulated posters and postcard invitations for the final tour in cafes within a few blocks of the group’s meeting spot—the trendy Monastiraki boutique-gallery. The Mile End neighbourhood is known as a young, artistic, hipster enclave, making it more likely that this demographic would become involved. Although this is not typical of all SensoriuM performances, it is probably not surprising, given this staging and framing, that the research walks drew a crowd of mainly twenty to forty year old university students. The group that assembled for the final tour was more diverse. I can only speculate about the reasons for this, but it could be that the advertising for the final event reached more people, since the research walks were only advertised on the project website and through its Facebook page and through Twitter, while posters were hung in the neighbourhood for the final event. It could also be that people tend to be more interested in consuming a final product rather than becoming involved in its making.

12 It should be noted that online audiences generated through Facebook, Twitter, and Blogger were distinct from the groups that coalesced from 2:00-4:00 p.m. during the tour. According to Facebook, SensoriuM posts on average tend to reach the twenty-five to thirtyfour year-old demographic. The page is reaching sixty-one percent women and thirty-five percent men, mostly in Canada with the biggest numbers made up of Anglophones in Montreal. And according to blogger.com statistics, the SensoriuM website is popular with a predominantly Ukrainian audience, followed by people in the US and Canada, using Internet Explorer on Windows. The project website has attracted 31,486 pageviews at the time of writing. This website is used as an archive and contains video, photo and textual documentation of all past events, as well as information about upcoming performances. It was set up as a blog to allow users to post comments, although it does not tend to be used in this way. The SensoriuM Facebook page also allows comments from everyone, and these have never been edited or removed. This page is used to create invitations to upcoming performances and to post links to related materials. In addition, the SensoriuM mailing list includes nearly 600 people, and is used to send invitations to events and to distribute a newsletter before each event with articles and information related to the given topic.

13 The somewhat surprising statistics for the project’s online users give some indication of the demographics of the SensoriuM’s publics. But what is the nature of their participation? This is a difficult question, and impossible to account for in the case of its virtual constituents, especially those all the way in Ukraine! However, it is possible to evaluate participation to some degree during the live performances and through their video documentation.4For instance, the third of four videos for the “Midsummer Mile End Tour,” posted on the project website on 18 June 2013 begins with participant Susanne Schmitt, a social and cultural anthropologist, defining “freeganism” based on the optional reading for that walk. Schmitt is followed by Michal Waldfogel, a singer/songwriter and student of naturopathic medicine, who voices her concerns about freegan practices. Then scientist and dancer Geneviève Metson chimes in with her views on urban agriculture. The camera follows this unplanned, ambulatory exploration across three research walks. These routes and conversations, directed by the participants, are the raw “data” from which the final tour was composed. Thus, while I mobilized the initial actors—in this case Taien Ng-Chan and Leah Garfield-Wright, a strip of sidewalk outside Monastiraki, a video camera, audio recorder and mapping apps, loud vehicular traffic, unspecified free food (to be located by participants during the walks), readings—the various members of the assemblage took responsibility for the unfolding of the performance once it had begun. This unscripted, exploratory research helps us to collectively discover our city’s abundant eateries anew—and evolves into a fluid script that we co–author as we walk.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 114 During the final Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour, a group of approximately forty-five people gathered at Monastiraki—the same gallery/curiosity shop that served as the meeting point for the previous exploratory walks. The expertise held by members of this particular group ranged from food activism, psychology, and ethnography to literature and green-roofing. The richness of this exchange of expertise was captured in the video documentation, in which diverse voices express views on urban foraging. During the tour, a debate broke out around the question of toxicity and edibility of urban plants.5In this segment of the video, we hear Garfield-Wright describe the properties of the biennial, flowering burdock, while the camera zooms in on a patch of this leafy bee-magnet, which is growing between an alley and a fenced yard. A tour participant contests Garfield-Wright’s assertion that the plant is unsafe to eat since it is growing in contaminated land. The participant points out that a vegetable garden is growing in the yard right beside the burdock, and its plants are surely eaten. A third participant counters this statement by arguing that many sites in the city are former land-fills and care should be taken before consuming any urban plants.

15 The identification of this plant as “burdock,” which is commonly known as a “weed,” and its re-signification as an epistemic object imbued with edible and medicinal uses, brings its value into question. Furthermore, its consideration in relation to bees and landfills and vegetable gardens represents a constellation of alimentary sites that are quite different from the usual food and drink “sights” promoted in the neighbourhood, a point to which I will return. Thus, this tour focused on the backstage—both support and detritus—of the cafes and bagel shops for which the Mile End is known. The debate about land toxicity—as well as others that emerged around the values, safety and ethics of harvesting, eating and sharing urban plants—arose from participants’ direct contact with the plants, and the invitation to eat. The intimacy of touching and tasting what would commonly be considered abject thickened the plot of “dining out” in Montreal. If the function of public art is to de-design, then it could be said that Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour undoes the corporate-civic work of producing the good consumer. It queers public space by encouraging non-normative unions between humans and non-humans and by re-valuing/re-evaluating the recuperation of waste.

16 In addition to identifying “weeds,” participants investigated the dumpsters behind Mile End shops, and learned how to recuperate sesame seeds that would otherwise be thrown away at a famous bagel store. The tour encouraged participants to consider the systems that sustain this neighbourhood’s hip, artistic, and touristy façade. It did so by highlighting what tourists and many locals would usually deem to be outside the sphere of “public” concern as “polluted,” “contaminated,” “garbage.” Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour celebrated that which is usually cast in opposition to the “social,” or in excess of that which has (rational) purpose. Productive antagonism was fomented through debate about what constitutes appropriate “food” in the places we visit. Again, it was through sensuous encounters with unconventional and lively urban fare that marginal stories about how to consume in Montreal began to emerge. And it was through sharing these tacit experiences that participants felt intimate enough to ask questions or to challenge what other participants were saying.

17 The conjunction of food and the places in which we encountered it had visible and tangible effects on participants and their interactions. This can be heard and observed in the video footage for the final tour,6for example in the exuberant thrusting up of a pineapple discovered in a dumpster by one participant, followed by the rushing in of others who dug for more while exclaiming in awe over beautiful broccoli. Political theorist Jane Bennett might attribute the affect generated in this encounter to “thing power” or “the curious ability of inanimate things to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle” (351). Bennett writes: “The relevant point for thinking about thing-power is this: a material body always resides within some assemblage or other, and its thing-power is a function of that grouping. A thing has power by virtue of its operating in conjunction with other things” (353-54). Furthermore, challenging what might otherwise be conceived as a subject-object relationship: “the particular matter-energy formation that is a human is always engaged in a working relationship with other formations, some human and some not” (354). The pineapple, the broccoli, the dumpsters, the alley, the sun that was shining that day, the participants on the tour, converged in that moment to produce an affective assemblage. The food, which until moments before was trash, was reconfigured in a way that dissolved dichotomies of subject-object, internalexternal, familiar-foreign. This is thing power. Its ecological potential is to provoke a reconceptualization of human—non-human relationships that leads to relational thinking-acting and ultimately a caring for what was previously understood as other.

18 In addition to the bounded audiences that gather for such events, the SensoriuM works with other community organizations in an effort to build food-art networks. Midway through Midsummer Mile End Tour, the group stopped at a cherry tree in a private front yard that was being harvested by Les Fruits Défendus. Organizer Thibaud Liné interrupted his picking to introduce our group to their work. Garfield-Wright had arranged this encounter in advance. As Liné explained, Les Fruits Défendus offers a service to tree owners who don’t have time to harvest their fruits. Volunteers harvest the trees, dividing the fruits in three, with a third going to the owner, a third to the volunteer fruit picker, and another third to an organization that promotes food security. No one on the tour was familiar with Les Fruits Défendus, but after this introduction, some expressed an interest in becoming volunteers. Others asked to work with the SensoriuM on future events. The cherries themselves surely had a role to play in this enthusiastic support. They were passed from tree to hand to mouth as participants excitedly commented on their sweet flavour. New communities thus continue to form as a result of this performance. Through a curatorial-dramaturgical practice I set the stage, putting various human and non-human entities into relation. Various alliances formed from there.

19 While my collaborating artists and I initiate these interactions, the agency of all entities involved allow multiple and divergent, unpredictable narratives to unfold. This is contrary to the effect of the designed city, in which relations between human and non-human actors are rendered abstract. For example, this walking tour and food tasting could be compared with another one that is offered by Local Montreal Tours in the same neighbourhood. Their tour is billed in this way: “The Mile End Montreal Food Tour: The Mile-End is famed for it’s [sic] gastronomic diversity. It also happens to be the best place to eat Montreal food specialties and discover the fine products of Québec’s terroir” (“Mile End”). The charge is $49+ tax and the tour is the same duration as the “Midsummer Mile End Tour”: three hours. It is the winner of the Regional Laureate for Les Grands Prix du Tourisme Québécois 2013. The details of this tour are also described on the company’s website:

Tours and tastings like this one render relationships abstract through a narrow interpretation of value in economic terms. This narrative presents the Mile End as “trendy,” and it is so for those who are able to pay. Those who can’t afford the admission, though, might not describe their experience of the neighbourhood as an “elegant,” “gastronomic,” “trip around the Mediterranean.” Using the narrative forms of the tour and the tasting to create such a representation of the Mile End renders the more complex relationships that sustain this fantasy abstract, or indeed makes these disappear. One disappearance, for instance, is the wasted food, some of which we recovered from dumpsters and a bagel shop on our alternative tour.

20 According to Local Montreal Tours, it would appear that the only topic of debate relevant to this gastronomic odyssey is where to find the best bagel. There is no real space for antagonism here, for the terms of the debate are limited by the question of where to spend one’s money. To reiterate Berlant and Warner: “A fantasized mainstream has been invested with normative force” (“What Does” 345). The notion of diversity is limited to a caricature of multicultural culinary delights that masks the low pay, long hours, and lack of job security for most people working in the restaurant industry, especially those without documentation, a subject incidentally, that will be the focus of another upcoming SensoriuM event.

21 In addition to the SensoriuM tour, a divergent textual representation of the Mile End was created through the “Midsummer Mile End Map,” which was produced by GarfieldWright and Ng-Chan in conjunction with this tour. The map measures 3.5” x 2.75” and unfolds to 11” x 17”. It is designed to fit the dimensions of miniature artworks that circulate through Montreal’s Distriboto—a network of former cigarette machines located in bars that have been retrofitted to dispense two-dollar artworks by local artists. One side of the map depicts the Mile End, indicating the tour stops and the sites where free foods have been identified. The other side includes botanical illustrations and information about five local plants, followed by playful instructions for navigating the neighbourhood, then a section of “supplemental resources” and information about the project, the collaborators and funders (see Figs. 2 and 3). We distributed these maps to participants during the tour on 20 July, and since then I have shared them with attendees at various conferences where I have presented this project. For instance, at the first annual symposium for the Arts Curators Association of Québec, I passed out maps, to which I attached origami envelopes containing tomato seeds that I had purchased from Greta’s Organic Gardens during the “Seedy Exchange” at Montreal’s Botanical Gardens. Through networks of cigarette machines, seed-saving, and international curation, the textual publics assembled through this map are also growing. I have been promised photos of Greta’s tomato plants growing in Tuscany and Berlin. Unlike the sanitized circuits of mainstream tours and tastings, these distribution networks spread through intimate exchange and along with the threat of contagion. The seeds after all were smuggled through customs and the maps circulate through dispensers with traces of carcinogenic products that are located in dingy bars. As Acconci implies in his writing, DIY culture “replicates what’s already there and makes it proliferate like a disease” (915). Appropriation is a tactic for taking advantage of marginal positions, and intimacy presents a risk to the sterility of dominant civic-corporate culture.

Display large image of Figure 2

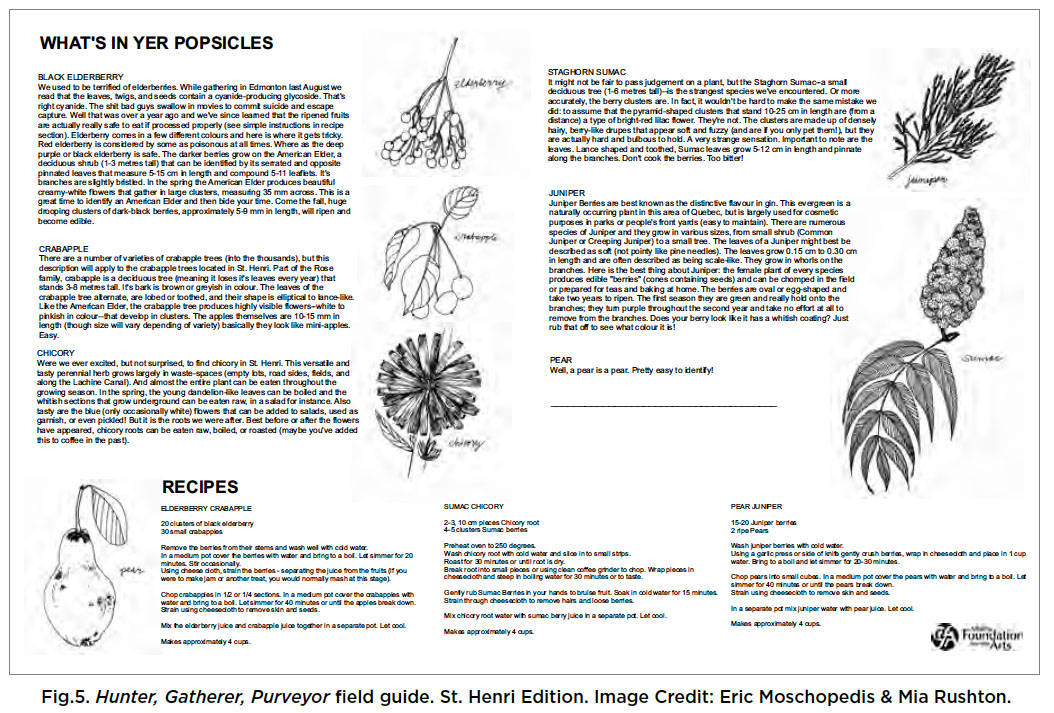

Display large image of Figure 222 Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor is another foraging performance. This time, artists Eric Moschopedis and Mia Rushton led a group of thirty to forty participants on a tour, pushing a mobile popsicle cart alongside the Lachine Canal, gathering local greens. The meeting spot was La Ruche d’Art St-Henri, a free community art studio and science shop that uses art to strengthen links between community members through dialogue, art making, and gardening (La Ruche). Partnering with La Ruche for this performance was a strategy to introduce people to this space, as well as to encourage neighourhood residents to join the tour/tasting. There was informal gathering and conversation in the studio before the tour began, and in the community garden at the end.

23 As in the Midsummer Mile End tour, the artists created a map/field guide for the neighbourhood of St–Henri, depicting the locations of wild plants, their nutritional and medicinal properties and recipes for use. They distributed these amongst participants and stopped at the identified locations to discuss what they have learned about the neighbourhood through its vegetation. Throughout the tour, people munched on various plants, including black elderberry and conifer cones. The artists imparted botanical identification skills using visual, olfactory, and tactile cues. This was an exercise in the development of what cultural anthropologist and chef Amy Trubek might call “sensory attunement,” through which people achieve a deeper connection to place (“The Map”). This activity engenders a collective caring for these public goods through learning about their properties and benefits.

24 Of course, the use of food in social practice and performance art is nothing new. Writing about her experience at “Points of Contact: Performance, Food and Cookery,” a conference organized in 1994 by the Centre for Performance Research in Cardiff, performance studies guru Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett remarks that: “Foraging for wild greens, traditionally a woman’s role, is part of ‘alternative, rural economy that enables survival outside the mainstream’ and that includes gardening, bartering, and other tactics for making do” (“Playing”). In this passage, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett links several “unmarked” terms: wild, woman, alternative, rural. The meanings of these words are informed by their unspoken/unwritten others: tame, man, mainstream, urban.

25 While Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor aims to develop aesthetic sensibilities that attune participants to their surroundings, it also undoes dichotomies such as wild/tame and rural/urban. The title of the piece refers to pre-industrial practices of hunting and gathering, and to a capitalist practice of purveying, meaning to sell goods. Living from the land and within a market economy are thus not set at odds within this work. The artists take on each of these roles simultaneously. They explain the roles this way on their website:

The “hunting” takes place in the year leading up to the walk, during which time Moschopedis and Rushton search for plants that grow in urban settings. They begin in their hometown, Calgary, then expand their search to other Canadian cities during a cross-country tour of the work, which is tailored to specific sites. Like wild mushroom-hunters, the artists locate varieties of local plants that have become familiar to them through talking with residents of the neighbourhood, and through identification research online and in guidebooks. Next, the artists “gather” this information, which has been made available to them through public resources. It is notable that Rushton is employed at the Calgary Public Library, while Moschopedis works across the street at the Bow Valley College Library, making literary research central to their process. While the passage above describes the “purveying” component as the distribution of free popsicles, I would argue that they work as “sellers” and “vendors” of their project also in the year leading up to the tour, when they are busy securing funding to bring the project to fruition. According to this interpretation, the so-called prehistoric or “savage” practices of hunting and gathering are entangled with regimens defined by advanced-capitalist, Canadian artistic funding processes. The park warden-naturalisthuckster is an oddity in contemporary city space and the appearance of this figure with a popsicle cart and group of would-be foragers in tow is a queering of the rational urban plan. It is also a tongue-in-cheek re-enactment of the colonial explorer, pointing to the artists’ own uncomfortable relationship to this place.

26 Furthermore, as in Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour, the now trendy custom of urban foraging that is played out thoroughly disrupts nature/human and associated dichotomies by collecting food in socially and chemically “contaminated” sites. Popular use of the term “foraging,” as exemplified on Wikipedia or About.com refers to “hunting, harvesting, grazing or fishing” for “wild foods”. By bringing participants to (post)industrial sites to gather food ingredients, Moschopedis and Rushton eradicate categories of nature and culture, while troubling notions of “safe” and “unsafe” foods and places. For instance, the artists lead the group to a “waste space on St. Ambroise” (see Fig. 4) to gather chicory, which they use in one of their frozen treat concoctions. Collecting plants from abandoned lots and urban waste sites and remixing them into an iconic form of juvenile leisure could be a way of taking responsibility for this contaminated world. This can be read as an illustration of what philosopher Timothy Morton dubs “dark ecology.” In his book Ecology Without Nature, Morton writes, “The ecological thought, the thinking of interconnectedness, has a dark side embodied not in a hippie aesthetic of life over death, or a sadistic-sentimental Bambification of sentient beings, but in a ‘goth’ assertion of the contingent and necessarily queer idea that we want to stay with a dying world: dark ecology” (184-85). In a certain way, the artists re-value the “dying world” of weeds and waste by processing plants into popsicles and by otherwise aestheticizing the experience of moving through derelict spaces. By assembling a group, led by a handcrafted popsicle cart attached to a bicycle, these spaces become accessible (come to feel safe) to a diverse group of people, ranging from infants to young people on first dates, to seniors. This is significant because it is a process that enables new relations between humans and non-humans to form, as participants come into intimate contact with untended plants and interstitial spaces.

27 The tour opens alternatives to the usual dichotomous depictions of this neighbourhood as either “depressed” or undergoing “revitalization.” St-Henri is commonly imagined as a working-class neighbourhood suffering from economic depression due to factory closures and massive layoffs that took place from the late 1960s through the 1980s. This “depression” is depicted in films such as St-Henri, the 26thof August, directed by Shannon Walsh in homage to the 1962 Hubert Aquin classic À Saint-Henri le cinq septembre and in walking tours such as Walking the Post-Industrial Lachine Canal, produced by Concordia’s Centre for Oral History. On the other hand, “revitalization” discourse shapes a revised imaginary for this place. For instance, Château St-Ambroise is a commercial loft complex in the neighbourhood, housing over 200 businesses, primarily within the “creative” sector (cinema, publicity, animation, etc.) (Château).Advertising for the complex exploits its history as a cluster of textile and toy factories that employed thousands of workers. In its romanticized version of the story, there is no mention of what happened to those workers. What I am arguing is that Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor creates an uncomfortable tension between these dichotomous narratives of urban decline, decay, and renewal.

28 First, the tour positions participants in intimate proximity to the neighbourhood. Detachment is not possible, as bodies crouch and reach and crowd together to assimilate parts of this living place into their own bodies. Is this a kind of “poverty tourism,” or exploitative tourism that involves visiting impoverished neighbourhoods? Artists’ complex imbrications with processes of gentrification have been analyzed from a range of perspectives (see Bishop; Deutsche; Harvey; Ley; Lowe). Some feel that it is best for middle-class artists to steer clear of such areas entirely, but I believe that a site-specific performance like this one can work affectively to complicate simple binary representations such as the depressed/revitalized neighbourhood narrative described above. Affective (or aesthetic) work is about creating new relations between humans and non-humans that expose our entanglements with so-called others, thus complicating the very notion of keeping out. Second, the artists depict the liveliness of St-Henri through its plants and demonstrate their use value through descriptions and recipes. Furthermore, they re-signify the “fallow” areas of the neighbourhood aesthetically— through their map/guide and their performance, each of which I discuss further below.

29 A challenge for this performance is the limited engagement of the artists in this particular neighbourhood. While they spent at least a year preparing for the performance, Moschopedis and Rushton had only one week to engage in direct fieldwork before leading the tour. This is a limitation posed by the small scale, independent nature of the SensoriuM. On the other hand, I do not see Hunter, Gather, Purveyor as an isolated event, but as part of a larger, ongoing project that aims to engage in meaningful, intimate ways with various parts of the city over time. Again, it is a learning process for all involved.

30 This neighbourhood tour mobilizes publics in multiple ways. As sociologist of science Bruno Latour argues in We Have Never Been Modern, the work of “purifying” nature/culture or nonhuman/human dichotomies paradoxically instigates the “proliferation of hybrids” (1). This happens through the process of translating the world into objects of knowledge. In this case, for instance, in translating plants onto the two-dimensional surface of a map and into recipes, popsicles, written and verbal descriptions, drawings, and a digital file, Moschopedis and Rushton produce “wild” plants and make these available for foraging. It is through these translation processes that living (plant) bodies are transformed into food or medicine, thus attributing social value to the natural world. By highlighting the “social” value of “nature,” the artists prove that this neighbourhood is always already vital.

31 The propagation of heterogeneous human-non-human communities is implicated within each of the multiple translation processes involved. For example, making flowers, berries, roots and leaves available to people as objects of knowledge for aesthetic, medicinal and nutritive functions involves their translation from growing things into assemblages of text and drawings (see Fig. 4). On the front of their handout, the artists create a hand-drawn map depicting the section of St-Henri covered by the tour. They adopt an imaginary aerial vantage point, presumably arrived at through observation of Google maps or similar online resource. This bird’s-eye view allows the artists to bring together the various stops on their tour within an easily readable two-dimensional surface. At a glance, it is possible to quickly imagine how to get from one location to the next, since the spatial relationships between each site are charted according to streets and a dotted line connecting them. Following common mapping conventions, the artists make use of a legend, numbering each stop on the map and indexing its precise street address and/or visual markers, as well as indicating the plant that grows there. Negotiating between this map and the terrain, a pedestrian will be able to retrace the path taken during the live performance and locate each of the plants visited, provided the site has not been transformed (indeed, the map and legend are markers of relationships in a particular moment, as the area is undergoing rapid change).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

32 The backside of the handout (see Fig. 5) includes a description and possible uses for each plant identified, accompanied by delicate botanical line drawings, followed by the three recipes used by Moschopedis and Rushton to make the popsicles. On this side of the page, the six plants used in the tasting (known as black elderberry, crabapple, chicory, staghorn sumac, juniper, and pear) are translated in several ways. First, through careful observation in situ and in comparison with field guides, Rushton has produced tender studies in pen, following conventions in botany. She has handwritten the name of each plant in cursive beside its image. These have then been scanned and imported into a digital file, allowing the drawings to be combined with other forms of representation. The plant descriptions and medicinal/culinary uses have been typed on a computer. The compiled information is a synthesis of research from various sources, the result of months of research outside, online, and in libraries, and condensed after a week of expeditions in St-Henri. Through direct observation of plants in “the field”, the artists identified each with the help of iPhones and a trusty plant guide, and later expanded their knowledge through further reading. They also harvested plant specimens and brought these home to conduct culinary experiments that eventually led to the pairings detailed in the three recipes, which can be prepared as hot or cold drinks, or frozen as they were for the tour. Once this data was compiled into a single document and formatted as a PDF document, it was printed for tour participants and disseminated online through the SensoriuM website.

33 This brief summary gestures toward the multiplicity of cultural forms that enable the translation of “nature” into an “epistemic object”—a cultural product that can be shared, reproduced, remixed, analyzed, experienced, and known. Without the aid of Google maps, a field guide, Wikipedia, Sharpies, word processing and design software, printers and blogs, as well as the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, the SensoriuM and its small project funding from Concordia University (not to mention all of the networks that contribute to each of those cultural products), this combination of plants in St-Henri could not have been made. Nor would any group of people have assembled around sour sumac chicory popsicles on 14 September 2013. And of course, no one would be downloading this map or reproducing the tour on their own. Thus, it is through the proliferation of nature-culture hybrids instigated by the proposal of hunting, gathering, and purveying in an artist-led tour of St-Henri that various communities—dispersed online, reading this article, gathered as a distinct group for two hours—are formed and set in motion.

34 In addition to the map/guide, intertextual publics continue to proliferate online and in print. Before the tour, journalist Jake Russell published an article for The Link Newspaper featuring Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor. Several participants found out about the tour this way. And later, one participant blogged about the performance on his site “Oopsmark.” Links to both articles can be found under the “Press” section of the SensoriuM website.

35 Again, food items are prominent actors in this performance. Throughout Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor, participants consumed a series of “terroir” products. In her book The Taste of Place: A Cultural Journey Into Terroir, Amy Trubek investigates the meaning of “terroir.” She defines it as “taste [. . .] produced by a locality rather than by a technique” (8) or the “idea that quality of flavor is linked to certain origins” (11). In the context of Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor, the concept of terroir is relevant because it points to the fact that participants taste the flavor of a particular place on their tongues. In this performance, bits of St-Henri are ingested and incorporated into participants’ bodies. The term “terroir” is most often used in reference to wine, coming from French traditions in viticulture and viniculture. The valuation of place that is signalled by “terroir” is now extending globally to other foodstuffs and marks a pride in local agricultures. To appropriate the term in the context of this postindustrial working class neighbourhood is thus to take pride in its bounty. Furthermore, it is an argument for the value of independent community life (human and non-human) in the face of encroaching condos and grocery chains. Trubek argues that “Placing or localizing food and drink is our bulwark against the incredible (and increasingly menacing) unknowns of our interdependent global food system” (12). Just how “menacing” the changes taking place in St-Henri are is complex and open to debate. My hope is that Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor will provoke just that.

36 This provocation happens largely through taste. I discussed the translation of plants into signs above, but their transformation into forms that can be consumed through the digestive system is also crucial to the aesthetic appraisal of the performance. Plants during this tour are also directly ingested or gathered to take home, so that the natural-cultural hybrids known as “elderberries,” “rose hips,” and “juniper berries” are important actors in “making public” here. The sensuality of the tastings is engaging, opening participants to conversations about land toxicity or gentrification that might feel alienating if everyone were not sucking on popsicles. Thus the tasting and discussion are mutually inflected. Distributed to participants in neon green, orange, and pink plastic sheaths, the frozen pops must be grasped in both hands and held until they are warm enough to be dislodged from their casings. The flavours jar expectations for these usually sweet summer treats. The sumac is sour, the chicory bitter, but the initial aversion is quickly replaced with curiosity over the strangeness of the taste, which becomes engrossing.7The artists transform abject weeds into objects of desire, creating uncanny encounters with these strange substances, which act in unpredictable ways on the taste buds.

37 Listening to Moschopedis talk about “tasting class and geography”8while licking a pear– juniper popsicle creates an unhomely or uneasy sensation. The video documentation of the last stop on the tour depicts twenty to thirty participants absorbed in the activity of consuming their treats while Moschopedis describes the recipe. This popsicle is created from a combination of a “working–class,” utilitarian plant—the pear—and the “middle–class,” beautifying juniper. The human body becomes the point of convergence for the two—this is a tasty strategy for facilitating a discussion about vegetation as a socio–spatial divider, while literally digesting it. In this experience, the pleasure of consuming St–Henri both physically and symbolically is complicated through discussion.

Maintenance Art9Today: Ethics and Aesthetics

38

39 In their article “Taking back taste: feminism, food and visceral politics,” Allison and Jessica Hayes–Conroy explore the effects of food ethics on the embodied experience of tasting. They attempt to specify “the link between the materialities of food and ideologies of food and eating” (461). The authors argue that destabilizing the boundaries between mind and body helps “to appreciate the ambiguity of embodied political agency” and stresses the importance of “rethinking everyday actions—including food actions—as unfixed outcomes of social–biological existence within discursive regimes that have political and ontological salience” (469). This argument complicates the notion that it is somehow possible to dissociate ethics and aesthetics. It is through the aesthetic choices made by Moschopedis and Rushton—in the creation of popsicles and the staging of their distribution—that pleasurable embodied consumption is troubled by class critique. The gentrification of St-Henri becomes felt. Performance artists are particularly skilled in bringing participants into their bodies and siting critique in that experience. Socio–political analysis of the connections between taste and place is an aesthetic practice, making artists suitable facilitators.

40 Cultural historian Constance Classen stresses the role of pleasure and sensual stimulation in creating a socially just city. In her essay “Green Pleasures,” she argues for an alternative to common urban design that emphasizes the “visual spectacle of the cityscape,” hiding sewage and electrical systems and massive waste behind shiny façades (177). Classen imagines a “tactile city” that would instead “increase opportunities for social interaction, such as the participation of the public in communal events” (178). According to her, this tactile city values “smaller, more intimate beauties rather than grand visual effects” (179). It seems to me that Classen’s hope for the future of urban design happens organically in un-designed or interstitial spaces, and sometimes through public art.

41 In my estimation, the Midsummer Mile End Foraging Tour and Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor both unveil “smaller, more intimate beauties” through participatory performance practice. Also, both performances employ a collaborative model of authorship that can be helpful in deconstructing the complex support systems required in any artistic production. Performance studies scholar Shannon Jackson uses the term “prop” to describe the material, social, and economic supports that are coordinated to bring a work into the world. My hope is to have revealed some of the props that sustain the SensoriuM as a project. Further, my intention has been to show how two specific performances worked to disclose the props that nourish local neighbourhoods. In this article, I have tried to analyze the SensoriuM as a curatorial-dramaturgical project in which assemblages of organic and inorganic actors are mobilized. Its events are breeding grounds where connections are made and begin to incubate. These convergences lead to cross-fertilization of material and digital varieties, gradually contributing to the infection of smooth official discourse that would shine its cosmetic veneer over the rough and sensuous edges of the city.10As connections like these continue to grow, so too do counter-cultural urban food-art movements. Inconspicuous, harmless, slipping in through the back door, these assemblages exist to thicken the plot.