Articles

Liz Gorrie and the Kaleidoscope Alternative

The alternative theatre movement in Victoria tends to be associated with the tenure of Don Shipley at the Belfry Theatre (1975-80), but it was arguably by Liz Gorrie and the Kaleidoscope Theatre Company, a Theatre for Young Audiences, that the alternative theatre movement was first brought to the provincial capital. Starting in 1974 and during its first two decades under Gorrie’s artistic directorship, Kaleidoscope was as politically and aesthetically radical in its objectives and practices as such better-known 1970s companies as Tarragon, Tamahnous, Passe Muraille, and Toronto Free Theatre. Kaleidoscope not only created work that bears comparison with that of contemporary alternative theatre for adults, but thanks to the purity of Liz Gorrie’s theatrical vision, and her deep respect for young audiences, it developed a style of TYA that “changed the face of children’s theatre in Canada and around the world” (McLauchlin “Interview”). Recognizing Kaleidoscope’s contribution to the alternative theatre movement in this country will require a look at the many ways in which the company earned its alternative credentials—even while addressing audiences made up of children. Jennifer Wise and Lauren Jerke look first at the company’s genesis as a progressive alternative to the city’s mainstream regional theatre, then consider its indigenous and collectively created material, its Grotowskian and Brechtian objectives, its anti-illusionistic Asian aesthetic, and its use of masks, puppets, transformation, and abstraction. As Wise and Jerke show, Kaleidoscope in the 1970s and 1980s utilized a virtual encyclopedia of alternative theatre techniques, earning a national and international reputation within five years of its founding and, the authors argue, meriting a permanent place in the history of the alternative theatre movement in Canada.

Les débuts du théâtre alternatif à Victoria sont le plus souvent associés au mandat de Don Shipley au Belfry Theatre (1975-80), mais on peut soutenir que c’est grâce à Liz Gorrie et à la compagnie Kaleidoscope, un théâtre jeune public, que ce mouvement a vu ses débuts dans la capitale provinciale. À compter de 1974 et pendant les deux décennies au cours desquelles Gorrie a assuré la direction artistique de la compagnie, les visées et les pratiques de Kaleidoscope étaient aussi radicales sur les plans politique et esthétique que celles des compagnies mieux connues des années 1970 telles que le Tarragon, le Tamahnous, Passe Muraille, et le Toronto Free Theatre. Non seulement on créait à Kaleidoscope des spectacles dignes d’être comparés au théâtre alternatif pour adultes de l’époque, mais la vision théâtrale de Liz Gorrie et le grand respect qu’elle vouait à son jeune public ont permis à la compagnie de mettre au point un style de théâtre jeune public qui a « changé à jamais le théâtre pour enfants au Canada et dans le monde » (McLauchlin « Interview », traduction libre). Pour saisir à quel point la contribution de Kaleidoscope au théâtre alternatif canadien a été importante, il faut examiner les divers moyens par lesquels la compagnie a acquis sa renommée comme théâtre alternatif, et ce, tout en s’adressant à un jeune public. Dans cette étude, Jennifer Wise et Lauren Jerke se penchent d’abord sur la genèse du Kaleidoscope depuis ses débuts comme alternative progressiste au théâtre régional conventionnel de Victoria, pour ensuite examiner son répertoire local et ses créations collectives, ses objectifs grotowskiens et brechtiens, son esthétique asiatique et anti-illusionniste et son recours aux masques, aux marionnettes, aux transformations et à l’abstraction. Wise et Jerke montrent que le Kaleidoscope a employé, au cours des années 1970 et 1980, toute une panoplie de techniques associées au théâtre alternatif qui lui ont valu une renommée nationale et internationale dans les cinq années suivant sa fondation. Elles font également valoir que la compagnie s’est mérité une place permanente dans l’histoire du théâtre alternatif canadien.

1 Founded in 1973 with a $23,000 Trudeau-era employment grant, Kaleidoscope Theatre has for forty years served as Victoria’s premier producer of Theatre for Young Audiences.1 But despite, or more likely because of, the company’s success with its chosen viewers, its place in Canadian theatre history has never been properly acknowledged.2 In 1971, when director Liz Gorrie, her husband Colin, tour manager Barbara McLauchlin, and actor Paul Liittich pulled into town in a camperized yellow school bus stuffed with all their worldly possessions, a piano, some pets, the Gorries’ children, and a copy of Towards a Poor Theatre, Victoria, British Columbia was perhaps the most unapologetically colonial city in Canada. With its Royal London Wax Museum and double-decker buses, its afternoon high tea at the Empress and nightly curry at the Bengal Lounge, its cricket greens and thatched cottages—not to mention its newspaper, The Daily Colonist—Victoria was reputed in the early 1970s to be “more British than the British,” and proudly so. Gorrie, McLauchlin, and Liittich, however, had other ideas. Together they launched a de-colonizing sea-change in Victoria’s performing arts culture, offering a genuine alternative to the city’s prevailing theatrical aesthetic. And most remarkably of all, they did so in original, collectively created works intended not for adults but for children.

2 The alternative theatre movement in Victoria tends to be associated with the tenure of Don Shipley at the Belfry Theatre (1975-80),3 but it was arguably by Liz Gorrie and the Kaleidoscope Theatre Company, a Theatre for Young Audiences, that the alternative theatre movement was first brought to the provincial capital.4 Starting in 1974 and during its first two decades under Gorrie’s artistic directorship,5 Kaleidoscope was as politically and aesthetically radical in its objectives and practices as such better-known 1970s companies as Tarragon, Tamahnous, Passe Muraille, and Toronto Free Theatre. Thanks to the purity of Liz Gorrie’s theatrical vision, and her deep respect for young audiences, Kaleidoscope Theatre staged work that, in both form and content, bears comparison with the period’s most celebrated alternative theatre for adults.6 In what follows we’ll examine the company’s genesis as a progressive alternative to the city’s mainstream regional theatre, then consider its de-colonizing, indigenous, and collectively created material, its Grotowskian and Brechtian objectives, its anti-illusionistic Asian aesthetic, and its use of non-realistic masks, puppets, transformations, and abstraction. As we’ll see, Kaleidoscope in the 1970s and 1980s utilized a virtual encyclopedia of alternative theatre techniques, earning a national and international reputation within five years of its founding and, we would argue, meriting a permanent place in the history of the alternative theatre movement in Canada.

3 According to the Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia, much of Canada’s alternative theatrical activity was fueled by federal government employment programs such as the Local Initiatives Program, or L.I.P. (also Plant 191; Johnston 7, 252; Benson and Connolly 85). Like Toronto Free Theatre, Alberta Theatre Projects, Victoria’s Belfry, and many other alternative theatrical enterprises in Canada, Kaleidoscope received crucial start-up funding under L.I.P.7 The company was born when journalist Barbara McLauchlin and actor Paul Liittich sat down together in Victoria in 1973, assisted by local actor Glynis Leyshon, to write up a L.I.P. application for assistance in offering free theatre workshops to children (“Free” 8). McLauchlin, Liittich, and the company’s soon-to-be artistic director, Liz Gorrie, had worked together in the past, in Brantford, Ontario, where they ran the avant-garde Total Theatre Company and developed the working relationship and division of labour that would carry them through the next twenty-seven years: McLauchlin as company manager, Liittich as performer/creator, and Gorrie as philosopher, visionary, playwright, choreographer, and director (Williams 3; McLauchlin Here 209-11; “Communication”).8

4 Like the founders of Toronto Free Theatre in 1971, Kaleidoscope’s creators, especially Liittich, wanted to make theatre available for free (McLauchlin “Interview”). Their first project, in 1973, was a free drama workshop, held at 1318 Broad Street, consisting of introductory classes for children in acting, set design, and costumes (“Free” 8). Later that year, they toured two short plays, The Pirate Show and The Magic Stone, to local schools, starting with the Girls’ Alternative Program, charging the schools fifty dollars a show (McLauchlin “Communication”).Liz Gorrie officially joined the company as artis- tic director toward the end of its first season, in 1974 (Chamberlain “Victoria Arts”); her husband Colin Gorrie—an architect whose teaching and administration job at Victoria’s regional Bastion Theatre had brought Kaleidoscope’s three founders to town in the first place—would also later join the company and assist in a variety of creative and management roles (Chamberlain “25 Years”; Williams 3). As recorded by McLauchlin in Here We Go Again, the first show Liz Gorrie directed for Kaleidoscope was her adaptation of The Musicians of Brementown (218).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

5 Beyond its genesis in the L.I.P., and its intention to offer theatre for free,9 Kaleidoscope derives much of its alternative pedigree from the contrast it provided to the city’s mainstream theatrical institution, the regional Bastion Theatre, which had been producing TYA for ten years. Established on an amateur basis in 1963 and professionalized in 1971, Bastion was a classic regional theatre offering a subscription season, theatre school, and touring schedule (Lawrence 46). With a mainstage repertoire (for adults) dominated by British and American classics and only slightly stale Broadway and West End hits,10 Bastion was an accurate reflection of Victoria’s colonial arts culture before the advent of Kaleidoscope. According to Bastion’s first prospectus, written by Peter Mannering in 1963, Victoria’s regional theatre would be defined by its dedication to “traditional standards,” and its avoidance of “new fad[s]” and new “Method[s]” (2). Rather than catering to “pseudo-intellectuals” who love “theorizing” and “‘significant’ theatre,” Bastion promised Victoria audiences “straightforward, entertaining theatre” (2). Twenty years later, in 1983, Bastion remained as committed to its imported repertoire as its founder was to “traditional standards.” In the very same year that an alternative company such as Tarragon, for example, had plays by Sharon Pollack, Erika Ritter, Jovette Marchessault, Mavis Gallant, David French, and George F. Walker on the docket, Bastion proudly offered Victorians a 100 percent imported season: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Real Inspector Hound, Gin Game, What the Butler Saw, and The Lion in Winter.11

6 Bastion’s offerings for children were, at least in one sense, more indigenous than its adult fare: they were inspired by the pioneering work of Joy Coghill, co-founder in 1953 of Canada’s first children’s theatre, Holiday Theatre of Vancouver (Doolittle 8). But by the early 1970s, Bastion’s borrowed approach to TYA had become as hidebound and traditional as its work for adults. According to Irene Barber in A History of Bastion Theatre, Bastion actually produced more theatre for children than for adults, and indeed relied on its TYA revenues to bankroll its mainstage season (10, 55). With its adult season booked into the McPherson Theatre, an 837-seat vaudeville house built by Alexander Pantages in 1914,12 Bastion’s costs were high for adult shows; TYA by contrast could be produced in school gymnasiums virtually for free (46, 10, 383-84). As fodder for the self-subsidy scheme, the company used existing fairytale scripts.13 A number of these, for example Marge Adelberg’s The Three Bears and Red Riding Hood, were created for Holiday Theatre in the 1950s.14 Bastion was still performing them in the 1970s. Out of a total of thirty-seven TYA shows staged by Bastion between 1963 and 1974, twenty-six were recycled fairytale plays of this type (117-343).

7 As former Bastion actors Barbara Poggemiller, Danny Costain, and Jim Leard recount,15 Victoria’s regional theatre took a strictly “traditional” approach to TYA. In shows like Treasure Island and Hansel and Gretel, “simple re-enactment[s] with lots of costumes” (Costain), Bastion told its stories with literal-minded realism and a well-stocked tickle-trunk of fairytale clichés (Costain; Leard; Poggemiller). Calculated primarily to “entertain” passive spectators, Bastion’s TYA work avoided “challenging” its viewers and required no imagination from them (McLauchlin “Interview”). Interaction between performers and audience was discouraged—except for after the show was over, when the children could have photos taken of themselves on stage with the actors (Costain; Leard). The failure of Bastion’s TYA shows to appeal to spectators’ imaginations was vividly captured by Gorrie, whom her associates fondly remember railing against the heaps of fairy tulle with which Bastion lost the attention of its young viewers: “Tulle? Children can’t relate to tulle!” (as qtd. by Poggemiller).

8 According to performers and reviewers alike, Bastion’s TYA lacked the elements of “surprise and tension” and left audiences bored (Barber 63, 97). In her review of The Enchanted Princess, theatre critic Audrey Johnson punningly lamented that the children were “not at all enchanted.” Barber blames a tired repertoire and a repetitive approach (96-97). Whatever the cause, the regional theatre’s unchanging approach to TYA does evince a certain lack of respect for its young audiences. As Barber recounts, the resulting succession of fairytale remounts impressed neither children nor funders: the Canada Council twice refused funding to Bastion, citing low artistic standards (50-55).

9 Kaleidoscope was founded on an alternate model that emphasized precisely the values neglected by Bastion, starting with a respect for young people as a worthy audience in their own right. Kaleidoscope’s artistic mandate, formulated in 1974 and faithfully upheld by Gorrie throughout her tenure, states that the company’s raison d’etre is to “provide innovative and exploratory drama for young people” (“Application” 15).16 Its goal was to make theatre that surprised, challenged, and engaged children, both intellectually and aesthetically (15). Above all, Kaleidoscope showed its respect for young audiences by holding itself to the same artistic standards expected of adult theatre. The company described its “prime concern” as the creation of “excellent, professional drama” regardless of the age of its audience (15).17 According to company members Poggemiller, Leard, Costain, and McLauchlin, Gorrie was fond of saying that the only difference between TYA and theatre for adults is that the former has to be “better.”

10 Gorrie charged Kaleidoscope performers to “share an experience” with their young audiences, never to condescend to them (Leard). Indeed, instead of conceiving of their spectators as “a children’s audience,” Kaleidoscope members were instructed to think and speak of them as “an audience [that happened to be] made up of children” (Costain). Costain explains that, by altering the language of TYA itself, Kaleidoscope was making it clear to the public that the company refused ever to “talk down to kids.” Poggemiller agrees: Gorrie’s shows were living proof that “children are not lesser beings. Children have incredible imaginations” and are capable of making all the same imaginative leaps as adults. According to her husband Colin, Liz Gorrie believed that children are even more capable of imaginative leaps than adults, whom she suspected of being hamstrung by linear thinking (“Notes” 7). As a result, and in contrast to the city’s mainstream TYA producer, Kaleidoscope quickly developed a reputation for fascinating audiences of all ages. In his review of The Musicians of Brementown (1974/75), Jim Gibson reported that, even by adult standards, it is a “highly witty” play, and that it used “an approach not much different from good adult theatre[;] adults love it just as much as the kids. It has…something to say and requires a bit of imagination on the part of both the audience and the actors” (“Grimm” 28). Gibson attributes the production’s success to its substantive content, to the fact that it had “something to say,” but also to the fact that its form made demands on its participants: like the rest of Gorrie’s work to follow, The Musicians of Brementown “require[d] …imagination” from spectators and actors alike (“Grimm” 28). A review of Steam, a play by Gorrie’s husband, similarly noted that the work’s “hilarious” treatment of British Columbia’s “politics, and power” will be enjoyed by children and adults equally (Gerhardt).

11 Under Gorrie’s artistic direction, and in keeping with her conviction that theatre for children should be the same as adult theatre “only better,” Kaleidoscope provided Victoria audiences with a radical alternative to the Bastion, and one that was soon recognized far beyond the confines of the city. At the end of its 1976/77 season, Kaleidoscope was invited to perform at the annual conference of the Canadian Child and Youth Drama Association in Ottawa (Williams 3).18 There its work was seen by hundreds of delegates of the International Association of Theatre for Children and Young People/Association du théâtre pour l’enfance et la jeunesse, or ASSITEJ, then the world’s leading association of TYA practitioners (Williams 3; Doolittle, Barnieh, and Beauchamp 9-11). Kaleidoscope performed Gorrie’s adaptation of The Snow Goose, from a story by Paul Gallico. The event sounds as nail-bitingly tense—and ultimately triumphant—as the opening night of The Seagull at the Moscow Art Theatre:

As Moses Goldberg explains in Children’s Theatre: A Philosophy and a Method, Russia has one of the oldest traditions of TYA in the world (65); that the Russian “grandmother” of TYA had embraced Gorrie’s work served as a powerful endorsement and put Kaleidoscope on the world map. As a result of the show’s success in Ottawa, Gorrie was invited to direct the play in Tel Aviv (Williams 3), and returned to Israel again to direct The Snow Goose and Unicorns at the National Children’s Theatre in 1981 and 1984 (Chamberlain “25 Years”).

12 In 1979, UNESCO’s “Year of the Child,” Kaleidoscope was chosen to represent Canada at an international TYA festival in Wales, the most high-profile the profession had yet seen (Williams 3; Johnson “Earns International” 6).19 Over the next twenty years, Kaleidoscope would perform in Japan, Singapore, Israel, New York, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., and Washington State; the company toured across Canada twice, performing in Toronto, Ottawa (including the NAC), London, Winnipeg, Montreal, Vancouver, and, according to Colin Gorrie, every city and town in British Columbia (“Notes” 12). Though Kaleidoscope’s tour to Singapore exceeds the scope of this paper, details of the show it took there in 2001 give a vivid sense of the impression this company made on the international stage: in the courtyard of an ancient monastery, Gorrie’s musical The Ant and the Grasshopper was performed inside a giant transparent box occupied by an 8-foot-high anthill swarming with actors in armyhelmets and military fatigues, surrounded by gigantic glass flowers made by world-famous glass-artist Dale Chihuly (Costain; Leard).

13 Near the end of its 1977 season, Kaleidoscope successfully applied for funding to the Canada Council (Williams 3), receiving less than requested, but significant verbal acknowledgement of the high aesthetic standards achieved by the troupe within its first four years:

The following year, Kaleidoscope performed for George Ryga, who was inspired to provide the company with a new work (Gibson “Playwright” 27).20 The result was Jeremiah’s Place, an analysis of “the roots of intolerance through the disintegration of a farm family” (27). Ryga’s stature in the adult theatre, built on his groundbreaking treatment of the systematic persecution of Canada’s aboriginal population in The Ecstasy of Rita Joe (1967), made his work for Kaleidoscope another endorsement of national scope. That same year, Kaleidoscope conceived and hosted Canada’s first International Theatre Festival for Young People in Vancouver (Williams 3).21 According to TYA experts Joyce Doolittle, Zina Barnieh, and Hélène Beauchamp, Kaleidoscope’s performance of Mon Pays—My Country was one of the highlights of the entire international festival (184). The National Arts Centre’s Youth Programme Coordinator for French Theatre, Magda Rundle, described Kaleidoscope in that year as “the most exciting theatre company for young people I have ever seen in this country” (Season Brochure). In a twelve-page essay on the state of TYA in English Canada a few years later, Dennis Foon devoted a page and a half to the “remarkable success” of Liz Gorrie’s “magical” international festival, detailing its positive effects on TYA across the country (12- 13). Discussing trends in TYA in Germany and England as well, Foon speaks of the “international reputation” that Liz Gorrie has achieved for her highly “experimental” art, which he contrasts with the safe, controversy-free “chestnuts for the younger set” favoured by mainstream TYA companies such as Young People’s Theatre of Toronto (6).22

14 Gorrie’s alternative approach to TYA can first be seen in her choice of material, which by any standard was sophisticated and wide-ranging, a strong contrast to Bastion’s parade of tulle-frosted chestnuts. Poggemiller emphasizes that Gorrie “always chose the best material.” In a 1978 interview with The Daily Colonist, Gorrie explained that “material [is] chosen which challenges the children and appeals to their emotions” (Williams 3). Even a very partial list of Kaleidoscope’s plays reveals this clearly: a 45-minute version of Peer Gynt for grades three to seven; adaptations of Moby-Dick and Gulliver’s Travels; a script based on the life of the Bronte sisters (The Brontes); a physical-theatre piece based on the myth of the Minotaur; multi-media works based on the stories of Carl Sandburg (Rutabega Country), and the poems of T.S. Eliot and e.e. cummings (Kaleidophonics); a Christmas story told through the poetry of Anne Sexton and Rainer Maria Rilke (Noel); adaptations of Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, and P.K. Page’s Brazilian Diaries. Kaleidoscope created TYA based on literature like Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, which Gorrie combined into a single play (Alice), on Marilyn Bowering’s Morganna LeFay story, Temple of the Stars, and on serious modernist music like that of Claude Debussy, Eric Satie, and Igor Stravinsky.23

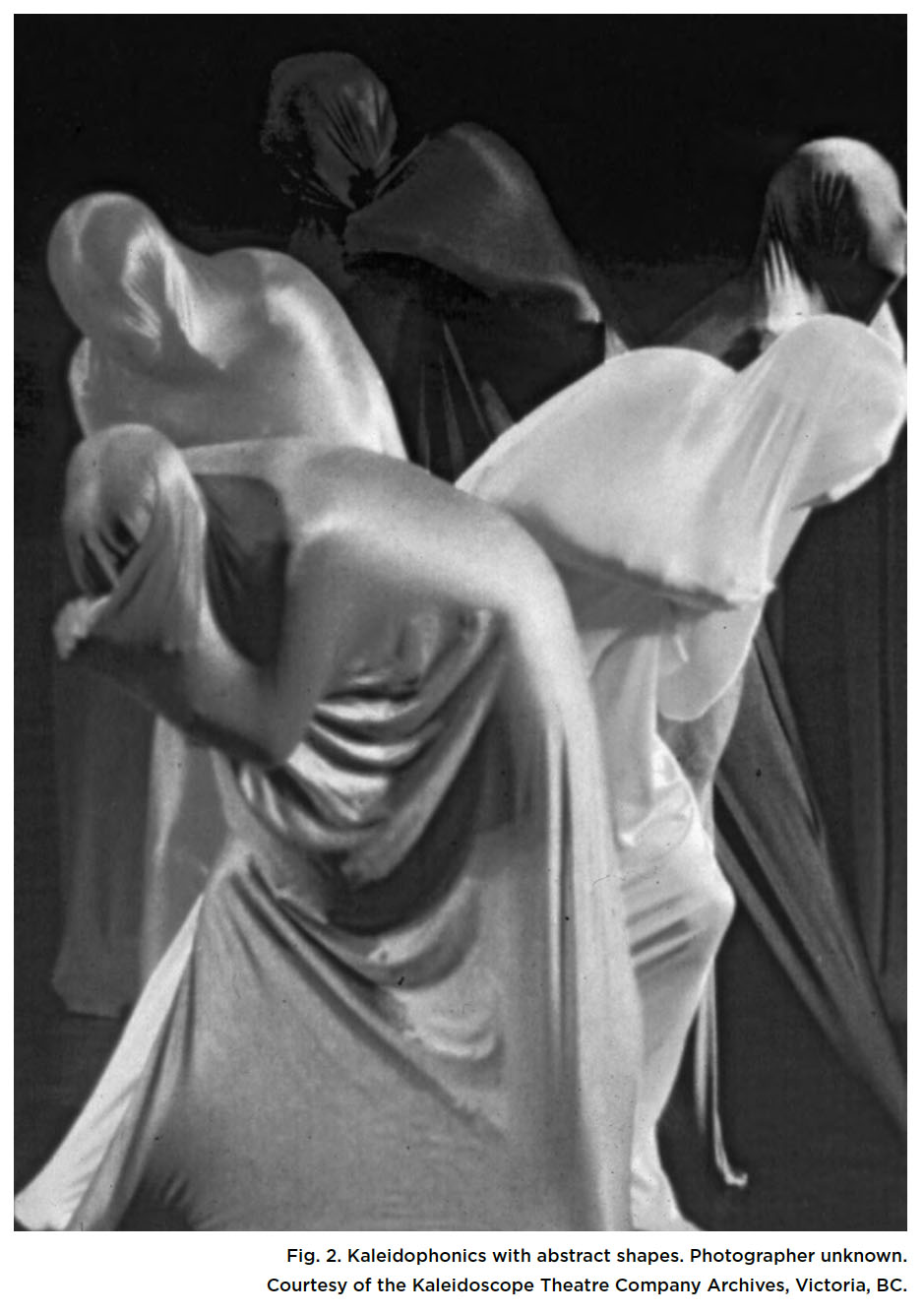

15 In contrast to the “sentimental,” “bunny-rabbit and pink-apron theatre” staged by Bastion (McLauchlin, “Interview”), Kaleidoscope offered its young audiences politically and emotionally challenging material that was “not afraid to show the dark side” (Poggemiller).24 Gorrie’s adaptation of The Snow Goose (1975), about the battle of Dunkirk, made no concessions to the protests of “aghast” Victoria teachers who thought that “children shouldn’t cry” or see death in a play (McLauchlin “Interview”). Her dramatization of the history of the seal hunt in The Selchie Song (1976) is a hard-hitting Marxist critique of the industry’s “brutality and greed” (1); the play was boycotted by local fishermen when it toured to Campbell River in 1976/77, and still makes difficult reading today.25Sumidagawa (1978/79) depicts a grief-stricken mother who goes in search of, finds, and mourns her dead son.26The Legend of the Minotaur (1975/76) ends with the killing of the bull.27About Free Lands, commissioned from Gorrie by Winnipeg’s Museum of Man and Nature in 1979, is a Brechtian analysis of the suffering of Ukrainian immigrants during the prairie settlement of the late 1800s and the labour movements of the 1930s. Gorrie’s Mon Pays—My Country28 is a piece of epic theatre about the destruction of the French-Canadian “way of life” replete with “images of dead and broken bodies” on stage (15). An Oriental Legend (1975) ends with the Nightingale and her lover dancing “a gentle dance of death” as the sun rises (7).29 With her Joseph Campbell-inspired view of the transformative power of myths and archetypes, Gorrie dared to take her young audiences across the river of death and into the darkest forests of history, for she was convinced that children are empowered by imaginatively overcoming the darkness and emerging back into the light (Poggemiller).30

16 Kaleidoscope’s preference for freshly-minted Canadian material, a stark contrast to Bastion’s repertoire, of course characterized virtually all alternative theatre in this country (Johnston 11, 75, 140; Filewod, “Alternate” 17; Usmiani 30; “Alternative and Experimental Theatre”; Plant 19).31 Of the forty-seven TYA shows performed by Kaleidoscope in the 1970s and 1980s, at least forty were original scripts.32 Some of these, furthermore, were indigenous not only in the sense of being created locally: Kaleidoscope was also on the cutting edge of the Canadian alternative movement in producing work inspired by First Nations material.33The Selchie Song is based on an Inuit story and champions the ecological wisdom of native elders (1-3).34How the Raven Stole the Sun, Moon, and Stars (1986; poetry and lyrics by Marilyn Bowering, music by Susan Ellenton) is based on a Haida West Coast indigenous legend (Hajimari program). Noel contains a Nootka poem. Other works based on explicitly Canadian material include Mon Pays—My Country, an epic of Quebec nationalism; Steam, a documentary play about B.C.’s transportation history;35 Ryga’s Jeremiah’s Place, which treats issues of Canadian citizenship and xenophobia (Gibson “Playwright” 27), and About Free Lands (1979), which dramatizes the hardships endured by Ukrainian-Canadians. Even toward the end of her career with Kaleidoscope, in the late 1990s, Gorrie was still at it, adapting Julie Lawson’s White Jade Tiger (1996), a novel about Victoria’s opium-laced Chinatown and the abuse and death of Chinese railway workers.

17 Kaleidoscope not only emphasized new Canadian work but also created its plays collectively. Collective creation, as Johnston and others have noted, was widely used by leading alternative theatre companies across the country (Johnston 23, 107, 109; Usmiani 46, 47; Filewod, “Collective” 24, 80; Benson and Connolly 86).36 Even when Gorrie based her plays on poetic and prose literature from Japan, Denmark, the US, or England, the resulting show was co-created-in-Canada by the company as a whole. Like such canonical plays of the alternative theatre as 1837: The Farmers’ Revolt—a play that, as its writer Rick Salutin explains, was generated by the research, improvisation, and on-stage creative problem-solving of many company members (164-75)—Kaleidoscope’s shows throughout the 1970s and 1980s were the products of the collective creation process. Kaleidoscope’s performers, directors, writers, musicians, and administrative staff formed a multi-tasking creative ensemble. They wrote music and songs together, conceived and constructed their masks and costumes together, problem-solved on stage together, toured as an ensemble, and sometimes lived together (McLauchlin “Interview”; Poggemiller; Costain; Leard). For The Snow Goose, they even invented new musical instruments together.

18 According to McLauchlin, an important early influence on the company’s collaborative approach was actor Paul Liittich, whose “special way” with improvisation helped to establish the troupe as a co-creative one from the start (“Interview”). The Magic Stone, for example, from 1973, featured a clown-character named Snod created through Liittich’s improvisations; though the play was eventually credited to writer Carolyn Stevenson and adaptor/director Jim Netherton, it was collectively created out of improv (Leard; Costain). The company’s first big success, The Snow Goose, is credited on its title page to “Elizabeth Gorrie and the Kaleidoscope Theatre Company.” By the late 1980s, the company’s methods had hardly changed. The house-program for Hajimari-no-Hajimari likewise credits individuals with specific creative functions, but adds, “NOTE: In Kaleidoscope productions, members of the ensemble not only perform, but also participate in the creative process.” Many of the most striking moments in Kaleidoscope shows were invented by the performers. For example, to depict a bed of oysters in Alice, five actors danced a clacking Spanish castanet dance wearing pairs of glove-puppets designed by Liittich and made out of plastic dinner-plates. In The Selchie Song, actors collectively created a rookery of seals with their vocal improvisations. For The Musicians of Brementown, Salt the Seas, Pepper Your Mints, and The Allihipporhinocrocodiligator, they wrote all the music together (Poggemiller; Gorrie et al.). Among Kaleidoscope’s performers at this time were African-Americans Ralph Cole—who had sung with the Lyric Opera of Chicago and left Kaleidoscope in 1979 to join The Nylons— and, on at least one occasion, Gospel choir leader Louise Rose. Cole wrote the music and lyrics for The Snow Goose; Liittich wrote the lyrics for the theme song of Unicorns (1982). Kaleidoscope actors were multi-talented inventors, singers, writers, and improvisers, and were chosen by Gorrie specifically for their willingness and ability to co-create the shows they performed in. In Colin Gorrie’s words, they “shared the creative process in all its aspects” (“Notes” 15, 19), and there were no prima donnas: an actor with a leading role in one play would take a supporting role in the next (McLauchlin “Interview”).

19 According to McLauchlin, Gorrie would bring her actors “the bare bones” of an idea, and then say, “let’s build [this] person. She always collaborated” (“Interview”). In creating their shows the company used what Poggemiller calls “the experimental method,” sometimes spending what felt like “a million hours” finding collective solutions to theatrical problems; and such was the precision of Gorrie’s vision and depth of her commitment that she “wouldn’t think anything of working on [a show] for months” before opening it (Poggemiller). And sometimes more: Kaleidoscope’s Pan-Pacific myth cycle Hajimari was collectively created over a period of two years (Program). Conceived and researched by Gorrie and in its first outing directed by visiting Japanese director Yukio Sekyia, Hajimari was then completely reworked, redesigned, and restaged by Gorrie and all the cast in a later version (Bowering “Interview”).

20 As art critic Robert Moyes wrote in Monday Magazine, Gorrie “always favoured avantgarde theatre over the safe, and improvisation over stale role; her central credo is that a production has to be ‘theatrical’ regardless of what it’s trying to say” (12). Gorrie’s concept of theatricality required the actors to create, and the audience to create right along with them. As McLauchlin puts it, “she wanted kids to see how they can create from nothing” (“Interview”). Like Robert Lepage, who believes that his audiences are intelligent, and want to help create the show rather than just passively consuming something that’s “already masticated and organized” by others (Lepage 242), Gorrie always strove to put the audience in an actively creative state. With extremely simple means, usually “an empty stage” (Mon Pays 4), a parachute silk, voice and movement collages, and richly evocative live sound effects, Kaleidoscope actors created scenery, weather, animals, and atmosphere right along with their viewers. For example, in The Snow Goose, Paul Liittich, a talented painter, enlisted the imaginative participation of audiences every night by magically creating a lighthouse scene on stage, from nothing, by merely painting one on an easel before their eyes; the rest of the cast, meanwhile, “create[d] the environment” of the surrounding marshes with a “sound collage” of rustling reeds, water, and bird cries with pipes, flutes, grasses, and voices (Gorrie, The Snow Goose 5-6). While Bastion’s practice was to keep performers and spectators cordoned off in their separate spheres, with the prefab sets and costumes producing all the effects and the children passively consuming the results, Gorrie’s perpetual injunction to her actors was to “break the fourth wall” and make the play along with the spectators (Costain; Leard).

21 Kaleidoscope did this through a non-literal, highly visual approach to storytelling. As Gorrie believed, “the less literal” theatre is, “the more magical” it can be (Poggemiller). Unlike Bastion’s Victorian-style plays, which aimed for nineteenth-century realism through a maximal use of illustrative sets and costumes, Gorrie’s work achieved the kind of abstract theatricality called for by modernists such as Enrico Prampolini, whose manifesto of 1915 demanded a theatre of visual artists: “Let us be artists too, and no longer merely executors. Let us create the stage, give life to the text with all the evocative power of our art” (23). At a time when a leading TYA company such as Green Thumb was making its reputation with TV-style realism “à la Degrassi High” (Prokash 14)—what Artistic Director Dennis Foon called “honest, earnest, kitchen-sink plays for kids” (11)—Gorrie used visual components that were abstract and evocative rather than representational. As Poggemiller explains, Gorrie believed that young audiences could “transport themselves into the world of the play with the help of the aesthetic.” Gorrie sometimes hired artists and set-designers such as Carol Sabiston, Mary Kerr, and Miles Lowry, but she always functioned as a visual artist herself in conceiving the company’s work. In a 1999 interview with Times-Colonist theatre critic Adrian Chamberlain, Gorrie spoke of “Kaleidoscope’s trademark ‘theatre of imagery’ techniques,” in which the emphasis is on the abstract and “the visual: colour, shapes, dance, and movement” (“25 Years”). In Poggemiller’s words, “Liz’s visual sense made it so that any production that she did was like a painting—or moving paintings.” Liz Gorrie had a genius for the “aesthetically pleasing, [the] beautiful and [the] transformable” (Poggemiller).

22 Transformation was Liz’s “watchword” (McLauchlin “Interview”). Always making things seem to “appear out of nothing,” Gorrie was, in Poggemiller’s words, “an alchemist” as a director. In Where Umbrellas Bloom, umbrellas and coloured parachute silks were used to create a year’s worth of seasonal imagery: a white silk evoked a snow storm, a frozen skating pond, mists, the moon, spider webs, bed-linens, a toboggan ride, moguls on a ski hill, and a cocoon for the first butterfly of spring, with her unfolding wings; another silk was transformed from a skipping rope to a kite to a blind-man’s-bluff mask to a hatching egg from which a baby bird is born (Gorrie, Where Umbrellas 2-11). Selchie Song used expanses of blue, green, and white fabric to create different moods and weather conditions at sea (Poggemiller). Kaleidophonics was a multimedia fusion of music, theatre, and visual art cocreated with the Victoria Symphony Orchestra and co-performed with them, as a standalone show, every two years between 1976 and 1989. While the musicians tuned their instruments, the actors’ movements were gradually transformed from dissonant chaos to ordered harmony. A toilet plunger became a stethoscope for diagnosing sick instruments; a clothesline became a musical staff, which in turn was transformed into a badminton net. During Grieg’s “Hall of the Mountain King,” six actors moved around inside stretchy black fabric bags to make abstract shapes; these were later shed to reveal brightly coloured shapes within, expressing a different phase of the music (see Fig. 2). In The Snow Goose, the white cloth shapes used to evoke the “wings” of a flying goose came apart to make clouds, and back together to make the sails of a boat. The various worlds of Peer Gynt were imaginatively evoked on a set that was “stark to the bone” (Poggemiller); with one large parachute silk of approximately sixty by thirty feet, the actors created everything: mountain, sleigh ride, Troll Palace, ocean, house, clouds, the desert.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

23 In the Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre, Joyce Doolittle describes the spectacular abstract aesthetics that Kaleidoscope achieved on a minimal budget:

In addition to using abstract shapes and minimal materials to stimulate the audience into acts of creative imagining, Kaleidoscope also involved its young audience more directly. The company was an early proponent of the post-show “talkback,” something that is standard almost everywhere today but was still unknown to many professional actors and audiences in Canada in the early 1970s (Costain; Leard).

24 Gorrie’s work also reveals its kinship with that of Canada’s recognized alternative theatre artists in its reliance on Grotowskian and Brechtian methods. As Johnston notes, Grotowski’s manifesto Towards a Poor Theatre (1968) served as a “bible” for many alternative theatre artists during the 1970s (30). Conceiving of the actor as an almost religiously dedicated creator, and emphasizing the deep spiritual relationship between actor and spectator, Grotowski inspired alternative theatre-makers across the country, from Tamahnous to Toronto Free Theatre (Filewod, “Alternate” 19; Usmiani 66, 67).37 As Colin Gorrie attests, “Liz was influenced by Grotowski’s work and the theatre that was coming out of the European laboratories of the 1970s. Her goal was to have a year-round ensemble” of the theatre-lab type (“Notes” 15).38 McLauchlin confirms that the writings of Grotowski shaped Gorrie’s aesthetic deeply, as had her experience seeing such 1960s shows as Marat/Sade, Dionysus in 69, and Hair (“Interview”). Gorrie’s first Grotowski-inspired work was her History of the Theatre (1970), a survey of human performance practices from ritual fire dances to the happenings of the 1960s, created and staged by Total Theatre in Brantford (Here We Go Again 73-74). Like the many adult alternatives working throughout the 1970s and 1980s to “break down traditional barriers between actors and audience” (Johnston 202), Kaleidoscope sought to unite the two in acts of spiritual communion where they created together (McLauchlin “Interview”; Costain; Leard). In detailed stage directions throughout her scripts—which she saw as not engraved in stone but always just a “starting point” for the collective creation of each cast (Mon Pays “Directing Notes”)—Gorrie repeatedly invokes Grotowskian concepts, calling for intense “ritual” concentration from her actors, total emotional commitment, and “direct confrontation” with the audience (Mon Pays 24). Her use of “estranging” epic techniques for raising the audience’s political consciousness is equally explicit. The “Directing Notes” for Mon Pays stipulate that the “style of presentation is similar to a Brechtian epic.” During one bloody battle, “the actor with the drum relates the events to the audience with total objectivity” (24). About Free Lands instructs the actor playing a father destroyed by “foreign masters,” “heavy taxes,” and “corrupt priests” to perform “a very personal dance of sorrow…with no expression on his face” (8). Sumidagawa features Brechtian techniques in abundance: white face, epic narration, actors repeating each other’s lines, and coolly describing emotional scenes in advance of their enactment (16-19). As Usmiani among others has noted, Brecht “exercised an enormous influence on the alternative theatre movement” in Canada ( 13, 29, 44, 45, 73-4, 80; also Benson and Connelly 106). Gorrie’s use of the stage for both Grotowskian soul therapy and Brechtian political awakening makes her a textbook alternative theatre artist.

25 According to Benson and Connolly, alternative theatre artists in Canada also shared the goal of making theatre in unconventional spaces (86). Kaleidoscope did likewise, and often. Gorrie’s alternative “theatre without walls” performed in such non-traditional venues as the rotunda at Carleton University (Snow Goose), the swimming pool at Crystal Garden (Alice), the Royal B.C. Museum (Steam), public parks (The Book Show), and local shopping malls (McLauchlin, “Communication”). Colin Gorrie remembers performances in libraries, art galleries, and an empty store-front on Douglas Street (“Notes” 20). Unlike Bastion, which imported its fourth-wall realism even into school gymnasiums, Kaleidoscope rejected all such “Victorian” traditions and sat its audiences on three and four sides of the actors (Leard; McLauchlin, “Communication”).

26 Another key feature of the Kaleidoscope alternative was its preference for non-Western performance styles and narratives. The non-naturalistic theatre traditions of China, Japan, and Bali were of course highly influential in shaping the modernist, avant-garde theatre in general (Usmiani 5); in Canada they were widely adopted by alternative artists from Luscombe to Salutin to Lepage. Artaud’s praise for the power of the Balinese theatre is well known, as is Brecht’s appreciation of the virtuosity and “defamiliarization effects” of Chinese actors such as Mei Lan Fang—who stopped in Victoria in 1930 on his way to New York (Chuang 6). Kaleidoscope’s first Asian-inspired work, An Oriental Legend (1975), was performed in slow motion, in a formal, defamiliarizing Chinese acting style, with accurately researched costumes (Costain; Leard).Next came Sumidagawa (1978), based on the fifteenthcentury Japanese Noh play. Performed for children in grades four to seven, Sumidagawa is described in Gorrie’s stage directions as an “Eastern” “theatre piece” that requires “an almost yoga-like muscular and mental control” from its actors; in performance, it must accurately evoke the “simplicity, philosophy, and mood” of the “Japanese art[s]” (1). In the opening sequence, an actor is lifted and carried downstage in a frozen pose in the manner of a Bunraku puppet (2). The play features prominent narrative punctuation by woodblocks, slow motion movement and gestures, “solemn” dressing and undressing rituals, and white-face (5-20).39 Hajimari-no-Hajimari was comprised of four creation myths from the Pacific Rim: “The Beginning of Heaven and Earth” (New Zealand), “The Beginning of Life and Death” (Japan), “A New Beginning” (China), and “In the Beginning” (Canada). During their collaboration with Japanese director Ukio Sekiya, Gorrie and her company spent two years mastering stylized Japanese movement and breathing techniques. The production toured Japan, the United States, and Canada in 1986/87.40

27 The Asian influence would remain strong in Kaleidoscope works through the following decade. Gorrie’s adaptation of The Nightingale gave prominence to Chinese percussion instruments, bamboo poles, and paper-cut-out shadow-puppets (36). White Jade Tiger would similarly call for enactment in “Chinese style” (1). Indeed, even in plays without Asian subjectmatter, Gorrie’s preference for a non-Western, non-realistic performance style is attested throughout her stage-directions, which repeatedly caution actors against “mere mimicry” and “precise mime,” and toward “stylized, slow-motion movement” instead (Peer Gynt 1, 5, 14; About Free Lands 16).41

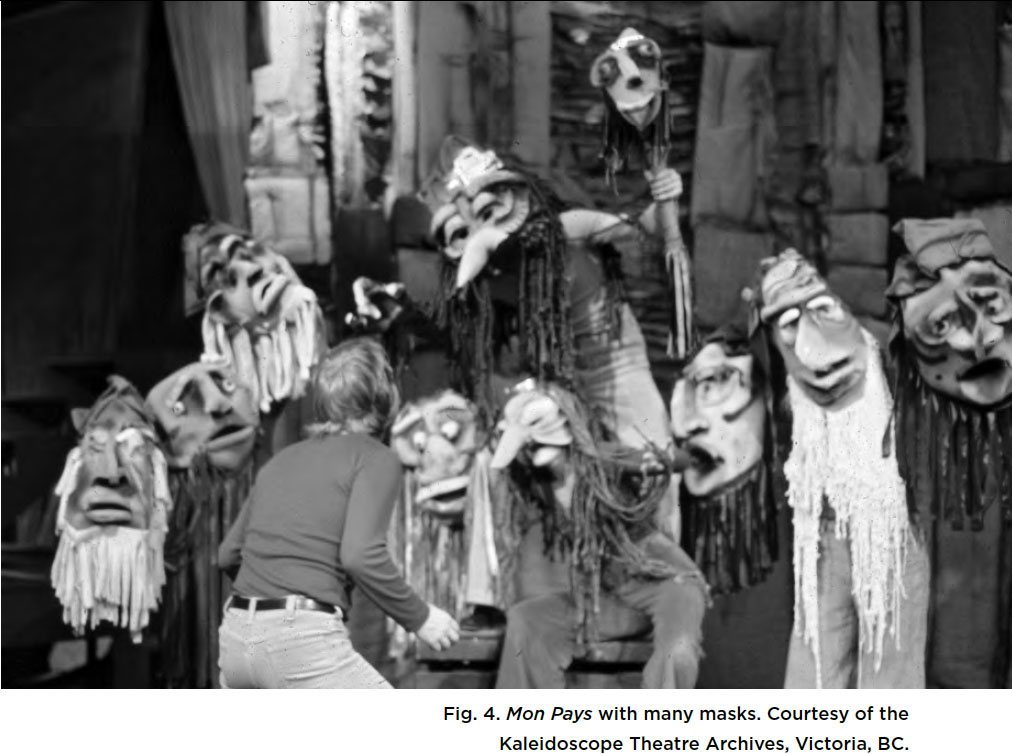

28 As an adjunct to its Asian-inflected, presentational approach, Kaleidoscope made extensive use of non-realistic puppets. In keeping with Artaud’s arch-modernist call for the use of “giant puppets” for spiritual awakening (“Cruelty” 270), and with Peter Schumann’s activist call for the use of oversized puppets for political protest (Schumann 196-97; Drain 159), Kaleidoscope gave such puppets a significant storytelling role alongside and in intense relationships with the human actors, whose skill in operating and relating to the puppets was foregrounded, not hidden. Seeming to anticipate the Arianne Mnouchkine of Tambours sur la Digue (1999), Gorrie demanded throughout the 1970s and 1980s that Kaleidoscope performers “create a relationship…where you brought your heart and soul to breathe life into the puppet, and there was no compromise on that” (Poggemiller). Costain and Leard also emphasize the importance that Gorrie attached to a full-body engagement when operating puppets and puppet-like objects. For example, The Snow Goose featured a giant goose puppet that was nothing more than three separate wire armatures covered in fabric, each about four feet long and attached to a plexiglass rod; depending on how they were manipulated by the actors, these abstract white shapes could be made to move together and suggest a bird in flight, when the actors achieved a synchronized, dance-like movement with them; at other times, the pieces came apart to become clouds, or the sails of a boat.42 In Sumidagawa, the little boy found at last by his mother beyond the river of death was portrayed by a life-sized rod-puppet operated by two actors in full view of the audience (McLauchlin “Interview”). InAn Oriental Tale, giant insects on poles whirred above the lovers’ heads whenever they met (Costain; Leard). Alice’s cat in Alice (1983) was a rod puppet (3). Kaleidophonics was full of massive puppets, from human-sized mushrooms to a female willow-tree made from an oversized Chinese parasol hung with vines. To embody the nature of a fugue, a team of giant notepuppets played a ball game; at another point, separate puppets representing an oversized arm, a leg, and a head came together to make a single puppet body. During Stravinsky’s Firebird, giant puppets fought. These included a firebird, a red serpent, and a fire witch, each equipped with hundreds of strips of red-painted foamy fabric that danced like fire when they moved. For Mon Pays, Carol Sabiston created twelve quilted doll-puppets to represent the burgeoning population of New France. And congruent with Grotowski’s thinking about theatre as a “poor” art-form made out of little more than the spiritual commitment of its actors, a Kaleidoscope puppet was not much in itself, coming alive, as Grotowski would say, “only through the actors’ use of it” (21). According to Poggemiller, Costain, and Leard, Gorrie’s directions for animating the snow goose applied to all of Kaleidoscope’s puppets: “it is essential that the actors manipulating the [puppet] extend its movements and feelings with their bodies and faces”; “the actors must provide” the puppet’s “physical actions and reactions…as well as its emotional being” (11, 1).43

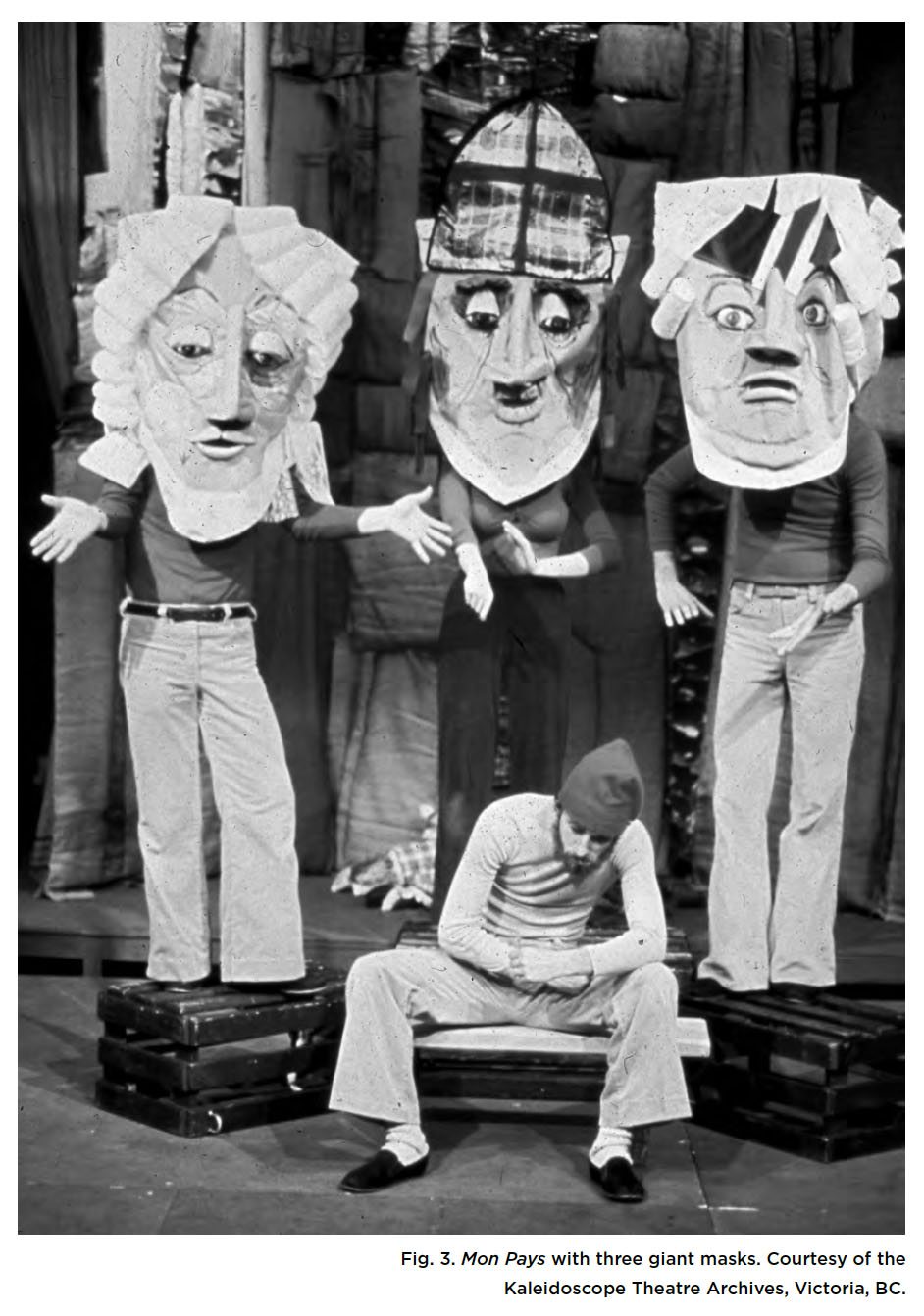

29 Along with puppets, most Kaleidoscope shows also featured non-realistic masks. At least from the time of Meyerhold’s The Fairground Booth (1912), many European modernists championed the use of masks as a way of clearing out the cobwebs of nineteenth-century realism. Meyerhold called for the emergence of a “new theatre of masks” (167-8), and Artaud did likewise in his seminal Theatre of Cruelty Manifesto of 1932 (268-70; Drain 274). Like other alternative theatres in Canada, Kaleidoscope preferred the primitivism of the mask to the illusionism of greasepaint. As Costain and Leard recount, the company created and used bull masks and a mask for Theseus in The Legend of the Minotaur; in The Musicians of Brementown, cast members made donkey, rooster, and other animal masks. For Peer Gynt, Liittich designed masks for all the characters Peer meets on his journeys, and the whole cast built them together (Poggemiller); for the Trolls, actors wore one mask on top of their head, and carried four more, two in each hand (6). Sumidagawa featured a white mask for the Fiddler (2), a white headdress that becomes a “grotesque” mask for the Queen of Forgetfulness (12), and a Raven mask of despair (15). In Mon Pays, oversized bobble-heads were worn to represent the English Elite, French Elite, and French Clergy (see Fig. 3) the three monstrous mask-heads then play a dice game, with giant foam cubes, for the people of Quebec.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

30 Finally, Kaleidoscope in the 1970s and 1980s shows its kinship with alternative theatres like Toronto Workshop Productions, Theatre Passe Muraille, and Global Village in Gorrie’s prominent use of dance-like, repetitious, abstract movement for its own sake (Johnston 1720, 206-8; Usmiani 50, 59; Filewod Collective 39, 43, 52). Like the Theatre Passe Muraille actors who became chickens, trees, and tractors in The Farm Show, or the separate facial features of Francis Bond Head’s head in 1837: The Farmers’ Revolt, Kaleidoscope actors created the world of their plays with inventive movements of their bodies. Gorrie in fact first worked professionally in the theatre as a choreographer (McLauchlin “Interview”). Like her fellow alt-theatre directors across the country, Gorrie relied on what she called “movement collages.” Nearly every Gorrie play of the 1970s and 1980s contains extended sequences of non-human physical embodiment. Together with their lips, tongues, voices, and instruments, Kaleidoscope actors used their bodies to create seals, horses, reindeer, marsh-birds, flowers, bees, waves, winds, forests, plows, sleighs, wars, and cityscapes. The Legend of the Minotaur featured a climactic bull-leaping contest achieved through carefully synchronized cartwheels and counter-cartwheels (Poggemiller). In Steam, the performers embodied paddle-wheel steamboats and trains (McLauchlin “Interview”). In Rutabega Country, actors moved over the stage on stilts, harvesting balloons. In About Free Lands, actors used rhythmic sounds and movements to represent the inner workings of an immigration official’s brain, and the dehumanizing “red tape” of the Canadian government (1, 2).

31 Kaleidoscope’s work in the 1970s and 1980s fits the category of “alternative theatre” on every count, and does so regardless of whose definition one chooses to apply. In the Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre, Alan Filewod distinguishes between “alternate theatre as a phase of post-colonial consolidation in the arts [. . .] linked to international currents of theatrical innovation in the 1960s and 1970s,” and an ongoing “tradition of experimental and popular theatre [. . .] that defines itself by its opposition to mainstream theatre [as] represented by such regional theatres as the Manitoba Theatre Centre and Halifax’s Neptune Theatre” (17). Kaleidoscope’s TYA was alternative in both senses: the company functioned as a powerful de-colonizing, re-indigenizing artistic force in Victoria in the early 1970s; and Kaleidoscope’s narrative material, creative method, and theatrical aesthetic stood in stark opposition to Bastion, the region’s mainstream producer of TYA. Ken Gass sees alternative theatre in essentially the same way:

Like Filewod, Gass equates the movement with the 1970s and with an opposition to the traditionalist regional theatre of the period. The definition of “Alternative and Experimental Theatre” provided by The Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia also stresses a re-enlivening opposition to mainstream theatre. This CTE article further defines alternative theatre as that which was “created in this country to advance theatre itself, to evolve it away from what was seen as ‘conservative,’ ‘traditional’ or ‘reactionary’.” Although the other two leading scholars of the subject, Renate Usmiani and Denis Johnston, provide no single definition, both stress that alternative theatre companies began in the 1960s and 1970s in opposition to regional theatres like Bastion, which were producing mainly British colonial and otherwise imported plays. Both Usmiani and Johnston also make the point that alternative theatres strove to create and develop a more indigenous Canadian theatre, while reimagining the possibilities for interaction between actors and spectators. As we have seen, Kaleidoscope’s TYA shows during the company’s first two decades exemplify all of these aims and objectives.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

32 Gorrie’s respect for young people as a worthy, perhaps even a superior, audience in their own right led her and her company to create a radical alternative to the Bastion—for Victoria audiences of all ages. Nevertheless, and despite clearly exhibiting all of the features identified by Canadian scholars for alternate or alternative theatre, Kaleidoscope has not been acknowledged anywhere in print to our knowledge as an exemplar of this category of Canadian theatre art.44 Kaleidoscope is named in the Oxford Companion to Canadian Theatre, but only under the category “Children’s Drama and Theatre in English” (93). Kaleidoscope is not given its own entry, nor is it considered or even mentioned as an alternative theatre or practitioner of alternative techniques. In their discussions of Canadian alternative theatre, Filewod, Gass, Johnston, and Usmiani fail to mention Kaleidoscope, as do Benson and Connolly; the latter’s English-Canadian Theatre merely adds the company’s name to a list of professional producers of TYA (108). The Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia provides no coverage of Kaleidoscope whatsoever, neither as a TYA company nor as an example of “Alternative and Experimental” theatre.

33 As should be amply clear, Kaleidoscope was an alternative theatre company, born out of the same conditions, reflecting the same aims, and employing the same methods and techniques as the many Canadian companies for adults that have since been classed as “alternative.” Rejecting the “traditional” approach of the regional Bastion, Kaleidoscope emphasized highly politicized national and native content, used stylized, ritually-inspired masks, puppets, and movements, favoured minimalist and self-transforming visual imagery, preferred suggestive abstraction to realism, and created its work collectively. Given these impeccable alternative credentials, it’s high time for Kaleidoscope Theatre to be admitted into the “mainstream” history of the alternative theatre movement in Canada.