Forum: Beyond Borders

Words…Words…Words:

The Novel, the Play, the Production

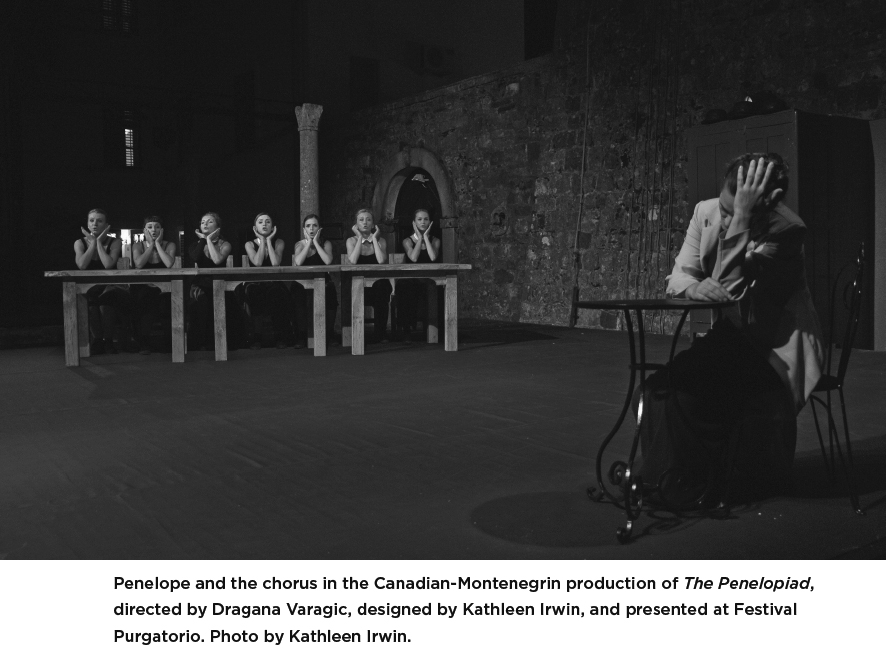

1 This paper looks, with two pairs of eyes, at a Montenegrin translation of Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad produced by Toronto-based April Productions for the Purgatorio Festival / 2012 in Tivat, Montenegro. The two perspectives are presented in turn by Dragana Varagic, the director and producer, followed by Kathleen Irwin, the set designer.

Dragana:

2 As Artistic Director of Toronto April Productions, I was invited to direct and co-produce a Canadian-Montenegrin co-production as part of the Canada Culture Days in Tivat under the patronage of the Embassy of Canada. The condition was that the play had to fit the Festival Purgatorio programming that produces and presents only plays related to Mediterranean theatre traditions. My first task was to suggest a Mediterranean play from Canada. I almost quit.

3 But, when I heard that the other Festival production would be an adaptation of Don Quixote with an almost entirely male cast, The Penelopiad, with an entirely female cast, immediately came to mind, even though the concept of a female cast playing both male and female characters is not very common in the Montenegro theatre tradition. Situated in Hades, The Penelopiad is written in a contemporary language and intersected with songs and dances. The play retells a part of the Odyssey from Penelope’s point of view, mixing references to the ancient myth with contemporary overtones. Odysseus’s killing of the maids upon his return from Troy is the event that spins Margaret Atwood’s play. It merges classical theatre traditions in its structure with modern theatre traditions in its style. In her introduction to The Penelopiad, Margaret Atwood states that “the chorus of Maids is in part a tribute to the use of the chorus in Greek tragedy, in which lowly characters comment on the main action” (vi). Her Penelope addresses the twenty-first-century audience from Hades, while her Maids sing songs ranging from ironic rope-jumping rhymes to ballads and Tennysonian Idylls. The Penelopiad’s postmodern approach opens up a space for an untold female perspective of the ancient story.

4 The play received very significant international theatre exposure through a co-production between the National Arts Centre and the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2007, combining Canadian and British talents. It was also performed in Calgary, Vancouver, and Toronto. All of these productions transported the English language audiences across time and space to ancient Greece. We took the opposite route, transporting the Canadian play based on a Mediterranean myth back to its original setting, surrounded by an audience from a culture firmly rooted in myths and legends. At the same time, we introduced a modern Canadian perspective by emphasizing the importance of women’s voices. It was the first production of the play in translation.

5 Montenegro is in every way a Mediterranean country, not only geographically with its seashores, ancient city-centres, hot and dry weather, but also traditionally with myths living at the core of its culture. Montenegro is well known for its epic poems from the past usually sung with the accompaniment of an ancient instrument called the gusle. Almost every citizen can quote from these epic poems that tell stories about heroic battles, beautiful women inspiring men’s heroic deeds, as well as philosophical thoughts about the purpose of life. In the past women were traditionally viewed as supporters, enablers of men’s heroic deeds, but did not play a prominent part as initiators and leaders. Montenegro has a long history of men leaving homes for wars, or working on transatlantic ships, while women stay home taking care of children and the land. I was certain that Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad would have a perfect audience there and that the play would resonate deeply.

6 I am a Serbian-Canadian theatre maker. I was born in Yugoslavia, a country that dissolved during the civil war into six independent states. Yugoslavia was one quarter the size of Ontario. The language understood in most parts of the country then was called SerboCroatian. Now, we have several separate languages: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin. Without getting into complex and painful political and language issues that ensued after the separation, I want to state that I perfectly understand all of these languages. Therefore, working in the Montenegrin language was not foreign to me at all. I formed my intercultural theatre family. I just hoped it would not be dysfunctional.

7 By May 1, 2012, the City of Tivat Grant and the Porto Montenegro Sponsorship were already confirmed (the Canada Council Grant came at a later date), but we still did not have the translation or the music, let alone set and costume design and the cast. On July 28 we opened the play.

8 As it usually happens, our doubts started creeping in towards the opening night: will the production communicate enough with the local audience? Is playback singing more appropriate for an open-air stage? Is the directorial concept clear enough? We stayed on course and true to the concept. Opening night standing ovations and rave reviews were the testimony that our The Penelopiad ship had come safely to the shore.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 “The play you hold in your hands is an echo of an echo of an echo of an echo of an echo of an echo”(v), says Margaret Atwood in her author’s introduction. “Down here everyone arrives with a sack [. . .]—words you’ve spoken, words you’ve heard, words that have been said about you” (3). “I’ll spin a thread of my own” (5), promises Penelope, the play’s storyteller. While Atwood questions the credibility of Homer’s account, she also provoked me to investigate the credibility of her Penelope’s story.

10 Who is Penelope? Penelope has become a well-known example of a humble and faithful wife. She is also a woman who runs the state and who, under her twenty-year-long rule, made Ithaca better than ever, hence her many suitors. But she is remembered as the one who waits and weaves. Society is still powerful in silencing women by projecting onto them false identities that sound nice but tend to dissolve and erase their agency. As a pragmatic woman, a mother of a teenage son, and a wife of a husband who is never home, Penelope is responsible for the survival of her home and family through difficult times. And then, in a moment that promises relief, she makes a mistake, a big mistake. I am interested in that moment of weakness that does not come with pressure and danger but with hope and the promise of relief. I am not only interested in a limited-choice situation but in personal responsibility when passivity takes on the role of complicity, as well.

11 In the novel’s introduction, Atwood mentions that the Maids’ chorus is focused on two questions: what is the reason for the hanging of the Maids and what were Penelope’s real intentions (xv)? In the play’s introduction Atwood states: “the play could be done with as few as seven-all female [cast members], mixed, or even all male. In this respect, the play retains the fluidity of the original mythical material” (vii). She also suggests that “it would be possible to envisage a different adaptation, in which … other scenes would be preserved. The ancient myths remain fertile ground” (viii).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 I took my inspiration both from the play and the novel’s two major chapters that were omitted from the play: the anthropological lecture by the Maids and the court trial—a video recording shot by the Maids. I liked the sudden incorporation of modern references within a play situated in Hades, and the urgency this juxtaposition created. My chorus of only seven Maids reconstructed the event in order to make Penelope reveal the truth in front of the audience. I cut the props. I cut entrances and exits. Everyone had to be on stage all the time. The Maids interchanged their roles of victims and perpetrators rapidly in front of Penelope and the witnessing audience. The roles echoed each other as the play progressed, while victims become victimizers, and victimizers heroes.

13 Our Maids became an active force that made Penelope change the course of her storytelling from family anecdotes to more pressing matters. The Lament Song, a ballad about the life of servants from the beginning of the play, turned to a protest rap song (Alexander Gajic) against Penelope, which warned that the rebellious Maids might take to the streets.

14 Small costume changes indicated when the Maids change roles, while allowing them to retain their servants’ identity at all times. The suitors who rape the Maids became a dangerous, almost military-trained group that moves in strict lines and speaks as one. They were dressed the same, but with bowler hats and worn-out tuxedos borrowed from the Theatre of the Absurd music-hall clowning. I also added some Theatre of the Absurd comic routines (e.g. the hat-passing game). The set and costume designers (Kathleen Irwin and Jelisaveta Tatic-Cuturilo) embraced the complex journey of our production: from comedy to tragicomedy and tragedy at the end. The production became fluid while crossing the boundaries of roles, genres and styles, the world of the living and the world of the dead, truths and lies.The production began and ended with motionless, statuesque Penelope covered with a cloth. The story comes from and goes back to the past. The beautiful ancient tower at the back of the open-air stage had one window as the only opening on the solid, stone surface, apart from the door. The production opened and closed with the light focusing on the window and with the music that we later identified as music for the hanging scene as well.

15 The sound of the vacuum cleaner confronted the opening music and took the audience’s focus from the ancient tower window to the stage, revealing an ordinary domestic set with a big wooden table with seven chairs on one side, a small table with a chair on the other, and a wardrobe at the back attached to the entrance of the tower. The blue colour of the wardrobe that spilled onto the blue colour of the floor, and the red ropes hanging from the window that connected the inside of the ancient tower to the contemporary set on the open air stage, were the only signs indicating that there was more to be expected than an ordinary life story.

16 “Now that I’m dead I know everything” (3), says Penelope in the opening line of the play. Penelope promises but never delivers the truth. Truth and reconciliation are not themes only in Hades, or the Balkans, or even Canada, but the play definitely touches on the most recent history of wars in this region. “It’s dark here … the gloomy halls of Hades …. Every once in a while the fogs part and we get a glimpse of the world of the living …. Sometimes the barrier dissolves” (11), says Penelope in her second monologue. In our production, Penelope and the Maids entered the world of the living to confront their stories in search of the truth, thanks to the courtesy of theatre.

Kathleen:

17 The unique material location (an outdoor stage abutting the seventeenth-century tower of the Tivat Cultural Centre, overlooking the Bay of Kotor on the Adriatic coast) and the political contingencies of this part of the world framed this production in interesting and diverse ways. Obviously, the conceptualizing of the production was—both for Dragana, who originally comes from that general part of the world, and for me, a Canadian who does not—an absorbing process of melding our ideas and, to a degree, our cultural differences. I want to speak about the production, the satisfaction I felt in working with Dragana on this exciting play and, very briefly, the strange experience of being in Montegnegro—a country of unbelievable beauty, rich history, complex politics, and strong women.

18 Of course,The Penelopiad, Atwood’s feminist retelling of the legend of Odysseus’s leavetaking for the Trojan Wars and his eventual homecoming is, itself, full of complexities. In it, Atwood underscores the victimization, villianization, and disempowerment of the woman who waited for him—even at the hands of her own maidservants and her eventual hand in their cruel death. One might say that the play’s message is both “be careful who you marry” and “women, beware women.” Given that this production was undertaken with a cast and design team of women, one may well have entered in to the process with a few trepidations. However, I hasten to add, among these talented and gracious women, I felt no need for anxiety—always, they made me feel welcome. What I would like to briefly recount is a tapestry of experiences that reflects my time in Montenegro and how the experience of working with Dragana and the other women made this a compelling and intense period of creativity.

19 To go back a step, what initially intrigued me when Dragana asked me to work with her on this production was her impulse to take this contemporary Canadian retelling of The Odyssey and return the classic narrative back to the story’s geographic roots and to an audience firmly grounded in epic tradition. I liked how this transposition productively disoriented what is Canadian and contemporary about it—that is to say, the voices of the women and their way of being in the world—by emphasizing the particularity of these thoroughly modern individuals within the antiquity and universality of the story.

20 To the intercultural mix I added my Canadian voice, or rather scenographic vision. A scenographer tells stories through images: like any other storyteller, I add things and I leave things out. I express the world of the play through a lens that recognizes the subjectivity of both the creative and interpretive acts of framing visual symbols. I see in my role a limitless potential to engage the senses and affect responses, emotions, and outcomes. This is my part of the story—to create the visual text of a production and to communicate it on a visceral level to produce a surfeit of feeling. I am most successful when my work is not noticed but felt.

21 While I had been to Belgrade on three occasions during and after the period of Slobodan Milosovic, I had never been to neighbouring Montenegro. Dragana’s invitation to work with her was an opportunity to expand my knowledge of this politically volatile, ethnically contested, and achingly beautiful region and I immediately accepted her invitation to design The Penelopiad, a play that profoundly touches her part of the world but comes, in Atwood’s iteration at least, from mine. Our challenge was to remain truthful to the author’s Canadian lens, feminist sensibility, and aim to contemporize the narrative, while also finding a way to bring the story of the Odyssey, a narrative of intrigue, betrayal, and violence, back to an audience who, given recent history, understand it fully.

22 Visually, there is no more apt a location to stage this play than overlooking the historic Bay of Kotor. A protected winding inlet, the area has attracted sea trade and wayfaring since antiquity. Archeological discoveries show evidence of old Greek harbour settlements everywhere around Tivat, as well as tombs and markers from the Roman period. The location of the unique outdoor stage where the show was to be mounted represented a fascinating piece of this long history. The five metre by four metre platform surrounded on three sides by audience was erected in the former garden of the aristocratic Buća family’s renaissance summer house. The hand-hewn rock tower looking out past the rocky coastline forms the upstage wall of the outdoor theatre. Indeed, standing at the top of the historic edifice, as Dragana and I did when I first arrived, it does not take a great leap of imagination to recognize the Odysseus legend in the intense blue of the sea and the looming coastal mountains that form the theatre’s backdrop. While the natural location did much of the work of visually framing the production, the challenge was to find a scenographic metaphor that reflected Atwood’s classic story rendered for the twenty-first century—a design for a play that, with its use of the chorus’s stroph and antistrophe,1 borrows from the dramatic form of early Greek tragedy as much as it pastiches theatrical genres as diverse as melodrama, vaudeville, epic theatre, and contemporary TV soap opera.

23 While a portion of the design concept was accomplished in Canada through a number of Skype conversations with the director (the size and layout of the stage, some of the scenic elements), my arrival in Montenegro urged reconsiderations. There is no shortage of sensory stimulation in this historically textured and vivid part of the world. These were exemplified by the water of the Adriatic dotted with white caps and crisp sails, the turbulent weather patterns seen in the dramatic expanse of sky, the black shadows of the hills, the brilliant flowers. In small sure ways, the colour and patina of the place seeped into the look of the show through palette and surface quality.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 324 Frequently, my design starts as a purely visual exercise expressed through line, balance, colour, texture, scale, and so forth—sketched and resketched. Naturally attuned to the visual, in Tivat I found myself dependent on my eyes to understand and interpret what was going on around me. With no Montenegrin language skills, beyond having copies of Atwood’s play in English and in translation, I operated in a fascinating space beyond words. Although people did speak to me from time to time in English, I felt, as one can imagine, somewhat untethered. I pondered what it meant to be abroad, adrift and awash in cultural nuances that I could barely comprehend—a Canadian on foreign shores. Penelope-like, although surrounded by other women, I felt cut off and ungrounded. At the same time, my senses were fully dilated, absorbing information through every possible means.

25 Stumbling through the language and local culture in this manner, I distilled the visual elements of the play and talked them through with the director. The immensity of the sea and the opacity of history gave us the key visual metaphors. Through frequent conversations and thumbnail drawings (our preferred way of working), she and I narrowed in on the azure of the water and made it the pervading colour of the stage. The scenographic elements were the ancient tower with its one window facing seaward (a given), a rough, sun-bleached table and seven chairs, the wardrobe that formed the sole exit and entrance, a vivid blue floor cloth, and seven red ropes representing the hanging of the maids at the play’s conclusion. The simplicity of these choices focused the fluid action that spanned places, crossed times, and moved rapidly between the few actors representing the many characters needed to tell the story.

26 My role as a designer is to provide a visual text that supports the ideas of the playwright and sustains the complexities of the director’s approach. When things are working as they should, I add another voice to the performance, sometimes in harmony and sometimes providing interesting dissonances and counter-rhythms. Here, the simple visual symbols, at first comforting in their familiar domesticity, underscored the violence that infuses the story as Penelope’s maidservants recount their rape by the suitors and then brutal murder at the hands of Odysseus. This is the narrative that haunts Penelope in the underworld where the maids repeatedly call for justice and a reconsideration of the legend. At the end of this production, Penelope is isolated at the front of the stage, cut off from the others, while the maids, grouped upstaged and overshadowed by the phallic symbol of the tower, draw the red ropes around their own necks. In this way, the scenography accentuated the culpability of everyone on stage.

27 Indeed, traditional feminists have had their difficulties with Atwood on the issue of power imbalances between genders and the construction of gender through family, school and other institutions still with us today that she explores in this writing (Shaistra and Banerji). Much as she demonstrates that men dominate and abuse women, she will not discount the fact that women are answerable in their abuse of each other. As in all things, the truth if it exists is unknowable or most certainly unspeakable. How was this visualized in this particular production? On our stage, the action begins when the maids enter from the tower through the wardrobe and the play ends when they disappear in the same way. The wardrobe exemplifies the unutterable essence of things—secrets partially revealed but never fully explained—uncovered momentarily but, just as quickly, covered up again. It suggests the infinite capacity of women to endure and to be heard.

28 Working with Dragana and her remarkable cast, whose ages and experience spanned a couple of generations, it was fascinating to see how each addressed their individual and collective histories and their current situation in relation to the European economic crisis that has hit Montenegro with considerable impact. Many of these skilled young actresses will have a very rough go of it, regardless of whether they stay in their chosen profession. Yet, I often heard them say that it was the beauty and culture of this part of the world that held them there. It made me reconsider my own few generations of history on Canadian soil and how important it is to understand where one comes from and to speak with strength and clarity from that spot.