This article uses the tools of intercultural and translation theory to explore the production and reception of La Reine de beauté de Leenane, the 2001 French language premiere of Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane, translated by Fanny Britt and produced by Théâtre La Licorne in Montreal. Creative team and critics alike understood the play as a realistic tragicomedy, and valued the production for the parallels it offered to real-life conditions of rural underdevelopment in contemporary Quebec, and for the ways in which the play’s depiction of Ireland was understood to resonate with Quebec’s own problematic postcoloniality. Such a reading does not take on board the strong current of exaggeration in McDonagh’s text nor the extent to which the play offers a satiric commentary on Irishness (and national identity more broadly) as commodity. The article weighs the positive effects of the sense of self-recognition and solidarity Quebecois artists and critics located in the play against the fact that inaccurate and misleading information about Ireland was disseminated via the production and its critical reception. Understanding this and other productions of plays in translation as intercultural encounters, the article advocates for the presence of interlocuters in such exchanges, who can speak on behalf the culture being represented.

Dans cet article, Karen Fricker puise aux études interculturelles et à la traductologie pour explorer la production et l’accueil de La Reine de beauté de Leenane, une traduction française par Fanny Britt de la pièce The Beauty Queen of Leenane de Martin McDonagh, mise en scène au Théâtre La Licorne de Montréal en 2001. L’équipe de création et la critique ont cru qu’il s’agissait d’une tragicomédie réaliste et ont mis en valeur les parallèles tracés dans la pièce entre les conditions de vie dans les régions sous-développées du Québec rural d’aujourd’hui et la façon dont la représentation de l’Irlande dans la pièce évoquait la postcolonialité problématique du Québec. Or, une telle lecture ne tient pas compte de l’exagération qui informe le texte de McDonagh ni de la satire dans le traitement du caractère irlandais (et, dans un sens plus large, de l’identité nationale) comme commodité. Fricker mesure les effets positifs de l’identification à la pièce et de la solidarité des artistes et des critiques québécois en regard du fait que des renseignements faux et trompeurs sur l’Irlande ont été propagés par la production et sa réception critique. Sachant qu’une pièce en traduction est une rencontre interculturelle, l’auteure fait valoir que la présence d’interlocuteurs capables de prendre le parti de la culture représentée serait souhaitable.

1 In 2001, only five years after the play had its world premiere in Ireland, Théâtre La Licorne in Montreal presented the French-language premiere of Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane, translated as La Reine de beauté de Leenane by Fanny Britt. The original production, directed by Garry Hynes in a co-production between Druid Theatre Company in Galway, Ireland, and London’s Royal Court, was an extraordinary success, transferring to the West End and then Broadway, where it won four Tony Awards. Beauty Queen has since been translated into more than forty languages, and productions of this and other of McDonagh’s plays, most of which are set in Ireland, now feature frequently in repertoires of theatres around the world.2 The Licorne’s production of Reine de beauté was also very successful: well received by critics, it returned for a multi-city tour of Quebec in autumn 2002 and winter 2003, ending with a reprise run at the Licorne in April 2003.

Display large

image of Figure 1

Display large

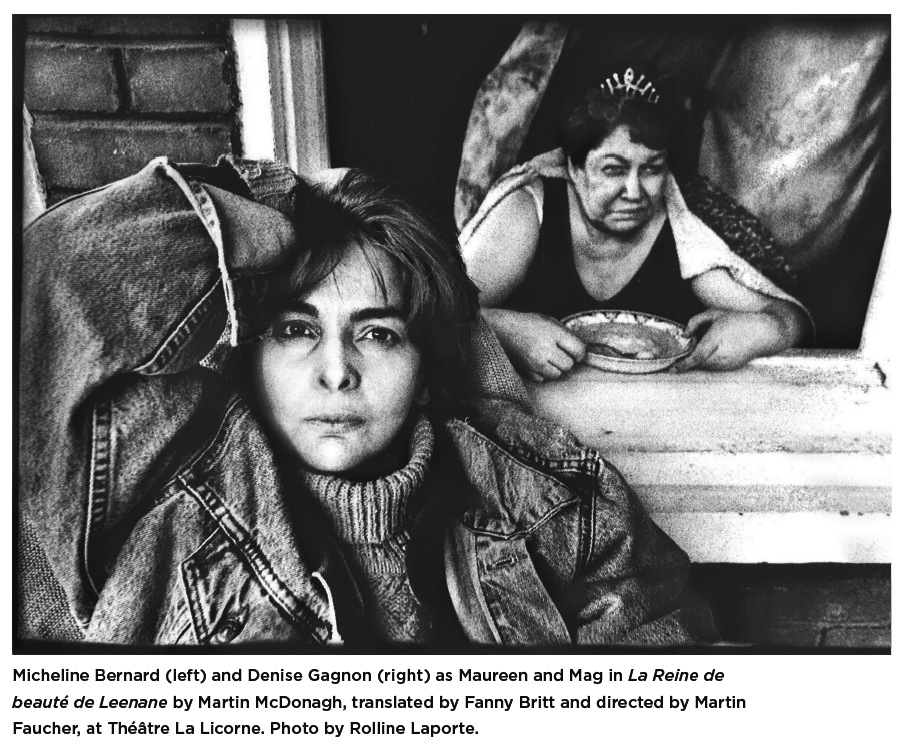

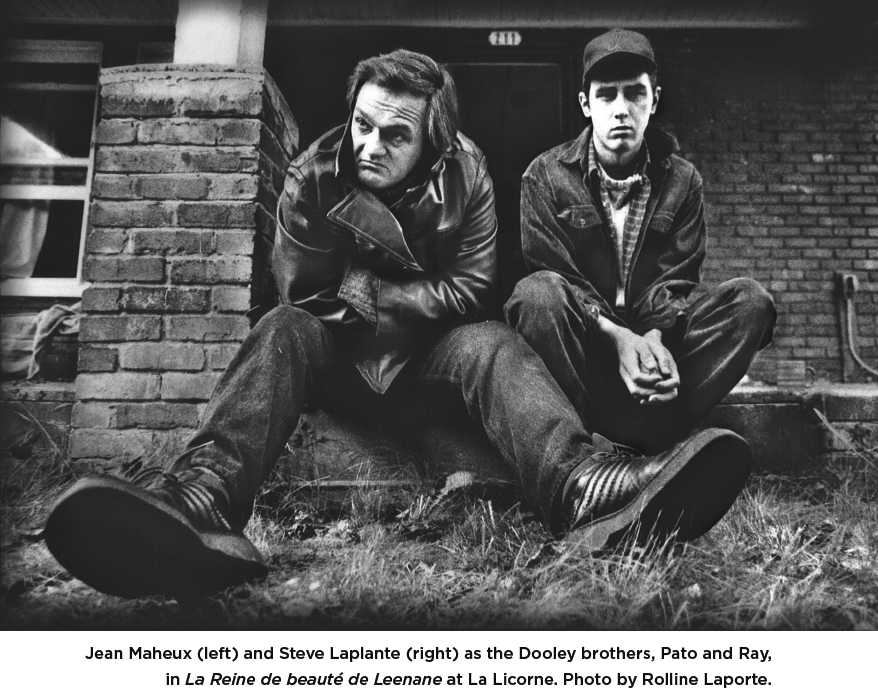

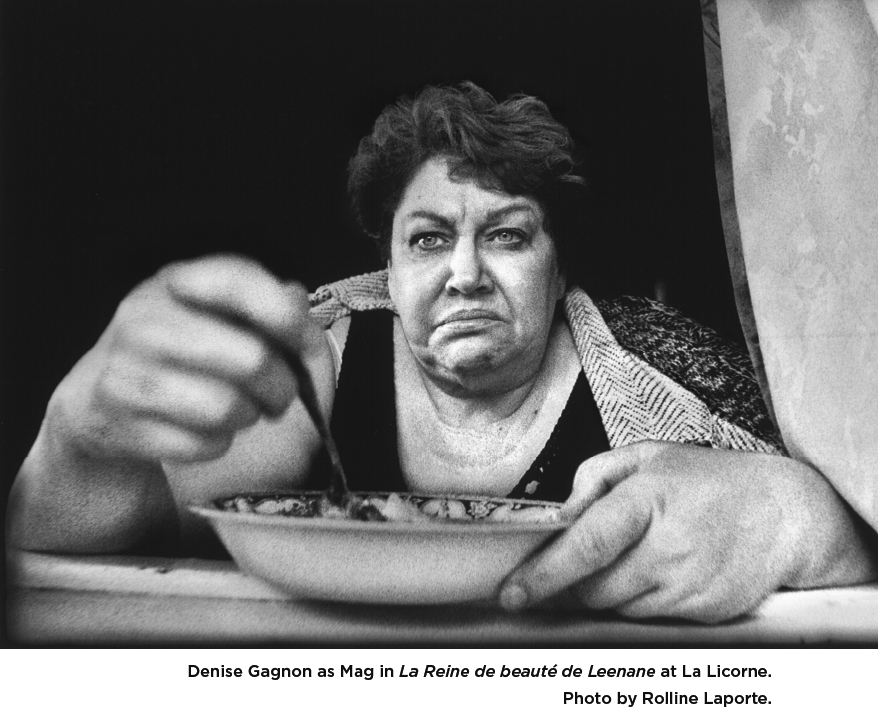

image of Figure 12 The play focuses on the stifling and highly dysfunctional relationship between a forty-something unmarried woman, Maureen Folan, and her mother Mag, who live together in economically depressed conditions in the real-life town of Leenane in Connemara, County Galway. Maureen gets a chance to escape when her old friend Pato Dooley returns home briefly from his work as a labourer in London; the two spend the night together, and Pato sends her a letter proposing that she move with him to America. The letter never reaches Maureen because Mag craftily coaxes Pato’s gormless younger brother Ray into giving it to her. When Maureen discovers this deception, she kills her mother and succumbs to mental and psychological illness.

3 By the time of the Licorne production, discussion had begun in Irish journalistic and academic circles about the particular representation of Ireland in Beauty Queen and other McDonagh’s plays, a debate which has continued since, fueled and rendered more complex by the plays’ international popularity. In the late 1990s, when Beauty Queen premiered in Galway, Ireland was emerging from a recession, and by 2003 it would be rated by Foreign Policy magazine as the most globalized country in the world, with a trade surplus of €32.2 billion (Lonergan, “Drama” 44). Under the conditions of what was dubbed the Celtic Tiger economy, thanks to the success of many of its artists in the realms of music, film, visual arts, and theatre (including McDonagh), Ireland asserted its presence on the global entertainment landscape, and Irishness became an indicator of cultural status and cool.3 The extended and sometimes ferocious debates about the “McDonagh enigma” (Lonergan, “The Laughter” 636) were symptomatic of an age in which questions of the commodity status and international market value of Irishness were at the centre of popular and scholarly consciousness.

4 Patrick Lonergan argues that McDonagh’s plays circulate well internationally because the Ireland they stage is not representative or mimetic, but rather offers up familiar signs and tropes of Irishness that allow the plays “to travel across international boundaries with ease” (Theatre 124). Lonergan offers McDonagh’s work as exemplar of a new kind of global culture, which “encourages audiences to respond to his plays’ universal qualities and dilemmas (desire to be elsewhere, inter-familial strife), while receiving his usage of Irish idiom and setting as markers of authenticity that ‘brand’ the experience” (127). As Lonergan further acknowledges, “[a] difficulty arises” when we move from an examination of how McDonagh’s plays and other globalized cultural products circulate through global circuits, to their effects: “once [the] works encounter an audience, they enter a social forum in which their use of idiom becomes problematic” (124). It is exactly such problematics that are my focus here, which can be usefully addressed by considering these encounters as intercultural, that is, as attempts, via theatre, to “bridge cultures through performance, to bring different cultures into productive dialogue with one another on the stage, in the space between the stage and the audience, and within the audience” (Knowles, Theatre 1). While it is the familiar and relatively ersatz Irishness of McDonagh’s plays that has enabled them to circulate globally, when these plays land in specific locations, this Irishness can become more than a brand. My study joins numerous scholarly accounts of international productions of McDonagh’s Ireland-set plays,4 exploring the particular meanings local artists, audiences, and critics derive from them, in an attempt to understand “what is actually transmitted in an act of global cultural exchange” (Powell 139).

5 In the case of the Licorne production, director Martin Faucher approached Reine de beauté as a piece of detailed realism, focusing in particular on the intense, stifling, and eventually murderous relationship between Mag and Maureen. Most of the critics reviewing the Licorne production read the play as reflecting problems of rural isolation and underdevelopment in Ireland, as well as the country’s continued strained relations with its former colonizer, Great Britain. They valued the production in particular for the parallels it offered to real-life conditions of rural underdevelopment in contemporary Quebec, which were at that time reaching a crisis point, and for resonances in the play with Quebec’s own problematic postcoloniality. As I will argue, such a reading of Beauty Queen as a reliable representation of contemporary Ireland misses out on the strong current of exaggeration in the text, and does not take into account the extent to which the play offers a satiric commentary on Irishness (and national identity more broadly) as commodity. We can locate some of the source of this interpretation in Britt’s translation, which, in moving the play into contemporary Quebecois French, flattened out many of its distinctive socio-linguistic features.

6 The strong affinity that Quebec artists and critics found with McDonagh’s play clearly stems from a sense of shared national identity struggle, in some ways similar to that which Kersti Tanen Powell identified as fueling successful Estonian productions of several of McDonagh’s Ireland-set plays including Beauty Queen. Like Ireland a small, peripheral European nation experiencing very rapid economic and cultural growth at the time McDonagh was produced there, Estonia is “carry[ing] the baggage of [its] oppressed past into [its] new, and newly rich, future” (Powell 147). As with the Quebec production, Estonian artists and critics valued the plays inasmuch as they provided a mirror onto their own situation; and as was the case in Quebec they grappled to make sense of the plays’ dark humour, with Estonian critics “[disparaging] the public for laughing ‘at the wrong places’” (148). The inability to fully grasp the plays as knowingly grotesque satire represents a “misreading” of McDonagh, Powell allows, but in it “can be detected a serious yearning for a less complex, a more straightforward present, where the need to ask questions never arises” (148). In Powell’s final analysis the Estonian case proves that “there is no need for a specialized knowledge of Ireland for the audience to enjoy and understand [McDonagh’s] drama” (149).

7 In focusing on the positive effects of a self-reflexive reception of McDonagh’s work, Powell offers a generous perspective. In my view, however, of concern in the Quebec case is the extent to which the sense of self-recognition and solidarity located in the plays was based on a misunderstanding of Ireland’s real-life socio-political realities, a knock-on effect of understanding the play as realism. As a result, inaccurate and misleading information about the source culture was disseminated via the production and its critical reception. The tools of intercultural theatre theory can help us explore these concerns. Following Emer O’Toole’s proposed ethics of intercultural theatrical encounter, it is my view that the right to represent another culture should not be an assumption or a universal given, but rather needs to be carefully considered and negotiated. Among O’Toole’s four criteria “for [. . .] thinking practically about the materialities surrounding intercultural productions and the ways in which these affect [their] rights of representation” is the presence of “a member of a represented culture” in the exchange (35). As I will suggest, in the case of the Licorne production, McDonagh’s play alone did not adequately serve as representative of Irish culture and because there was no expert or advocate present to speak on Ireland’s behalf, the result was misinterpretation and misunderstanding.5 By contrast, I will close the article by briefly discussing several translation initiatives in which Montreal’s playwrights’ centres, the Centre des Auteurs Dramatiques (CEAD) and Playwrights’ Workshop Montreal (PWM), and the Licorne have been involved, bringing Irish and Quebecois writers (amongst other nationalities) together and enabling intercultural exchange towards translations and productions that displayed a more robust engagement with representational issues.

Translation, Interculturalism, Quebec

8 My discussion draws on, and is intended to extend, existing scholarship on the production and reception of non-Francophone plays in Quebec, which until recently has been focused primarily on questions of translation and in particular on the “power struggle” between French- and English-language Canadian literatures (Ladouceur 1). In her landmark study of theatre translation between Canada’s two official languages, Louise Ladouceur identifies a key shift in theatre translation in Quebec. In the 1970s and 1980s, translation tended towards adaptation, “transposing the action into a Quebec setting and totally appropriating the initial play to the target context,” which included changing place and character names, as well as references to social and cultural markers and issues. Following Annie Brisset, Ladouceur classes this an “ethnocentric approach” requiring “any signs of alterity to be removed so that the translated text is able to reflect the reality of the Quebec society and thus contribute to the development of a repertoire claiming to be specifically Québécois” (18). These practices were part of the nationalist spirit of the time and played a role in the development of a distinctly Quebecois literature and culture. As Bernard Lavoie argues, “translation became a means for the community (Québec) to express and recognize itself through another community” (6).

9 By the end of the 1980s, however, there was a stronger sense of Quebecois national identity, including national literary and cultural identity, and “[a]daptation had begun to be frowned upon” (Ladouceur 199). The emphasis shifted from bringing the source text into the world of the target culture to “the textual novelty” that the source text (in the context of Ladouceur’s study, the Anglo-Canadian play) had to offer (199). In Lavoie’s reading, this shift also represented increased familiarity and comfort amongst Quebec theatre artists and audiences with their particular mode of verbal and linguistic self-expression, whereas previously “it was assumed that a person speaking Québécois could not portray a character from any geographic origin but Québec” (6). From the early 1990s forward, “Québécois became a language capable of transmitting complex realities [...] it too could express levels of social status and modes of reality drawn from any foreign culture”; consequently, “theatre translation has become a means of moving Québec towards other cultures, a tool to open Québécois culture to the world” (6, 7). Since that time, the dominant practice has become the translation of English-language plays into Quebecois French, with place and character names and other markers kept as in the original.

10 The Licorne’s relationship to theatre in translation adheres, broadly speaking, to this historical narrative.6 Its repertoire has always been international: Its first seasons in the late 1970 featured primarily new Quebec writing alongside existing translations of Chekhov’s The Three Sisters (1976-77), Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood (1976), and Shakespeare’s Macbeth in Michel Garneau’s Quebecois tradaptation (translation/adaptation) (1978-9). Its first production of new Anglophone writing in translation was David Mamet’s Sexual Perversity in Chicago, appropriated, as was the dominant practice of the time, into a local context as Quelques Curiosités Sexuelles Rue St-Denis, which played in 1983. The Licorne’s founding director Jean-Denis Leduc recalls that the company’s early methodology for bringing plays such as Sexual Perversity and Tom Walmsley’s Something Red (1985) into the French language was ad-hoc: “we didn’t really know [. . .] we did the translation at the same time as we were rehearsing...”7 After producing several English, American, and other international plays in translation in the 1980s, including Ashes (Cendres) by David Rudkin, and Free Fall (Chute Libre) by Laura Harrington, the company’s first Anglo-Canadian play in translation was Judith Thompson’s I am Yours (Je Suis à toi, translated by Robert Vézina) in 1990. Though well received by critics for its performances and direction, the production suffered from “incoherent translation choices,” according to Ladouceur: though “class conflict is a central theme in the play [. . .] all the characters [spoke] in a highly-accentuated joual” (21).

11 CEAD and its then-project director, the translator Linda Gaboriau, played a key role in bringing the Licorne into contact with new Anglophone playwriting in the late 1990s and 2000s. Leduc sat on a committee identifying texts and authors for exchanges between Quebec and Scotland, Ireland, and England; having a Montreal artistic director as part of this process was part of Gaboriau’s successful strategy, Leduc says, to see plays not just translated, but produced. The Licorne has since produced over a dozen new Anglophone plays in translation including plays by the Irish writers Hilary Fannin, Stacey Gregg, Deirdre Kinahan, and Mark O’Rowe, in addition to McDonagh. As Leduc explains, the Licorne’s international productions are driven by the identification of points of commonality between the worlds depicted in the play and Quebec realities, and underlain by a desire for cultural connection:

Leduc further comments that he gravitates towards plays in which a microcosmic, often domestic situation stands in for a larger socio-political milieu: it is “these kinds of texts that I’m always looking for, something that talks to us on a human level and on a societal level.”9

12 If we take as a baseline definition of intercultural theatre that it is a “theatrical fusing of two or more cultures” (E. O’Toole 1) that “attempts to bridge cultures through performance” (Knowles, Theatre 1), then the Licorne’s goals for its productions of non-Quebecois plays can clearly be understood as intercultural. By staging a Scottish or Irish play in Quebec, Leduc finds value in the similarities and parallels between the local and foreign cultures, and sees these as a point of connection for his audiences that will help Quebecers see their culture as not unique but rather as one of a community of small but culturally vibrant nations. As will become evident in the discussion of reviews below, critics too find considerable value in the comparison that Irish plays provide to their own national culture, which sometimes offers opportunities for cultural self-critique. Though considering such exchanges through an intercultural lens therefore seems a valid strategy, this approach has not frequently been taken in studies of international aspects of Quebec theatre, in part because of the predominant focus on questions of translation mentioned above.

13 Another likely reason is that, in its initial stages in the 1980s and 1990s, intercultural theatre scholarship tended to treat productions in which there was an asymmetry of material and power relations between the cultures involved in the exchange, most frequently in the form of Western theatre artists using non-Western source texts and theatrical forms and styles in their work. These relationships are often inflected by colonialism, in that the cultures doing the borrowing (or, as some would have it, appropriating) were often the present or former colonizers of the culture borrowed from. Increasingly, however, as the circulation of texts, artists, traditions, forms, and styles increases, we are seeing “intercultural exchange between nations whose relationship is not strictly that of imperial power to colony” (Harvie 11). As Jen Harvie has argued, such exchanges can nonetheless benefit from examination through an intercultural lens, as they can still be inflected by, and reflect, “imperial and other forms of cultural power” even if the exchanging nations are themselves both former colonies.

14 Harvie made early moves towards thinking Quebec theatre interculturally in her 1995 essay in this journal, “The Real Nation? Michel Tremblay, Scotland, and Cultural Translatability,” in which she raised important questions about the celebrated translations into a Scottish idiom of Michel Tremblay’s plays. Harvie argues that early 1990s productions of The Guid Sisters, Hosanna, The Real Wurld?, The House Among the Stars, and Forever Yours, Marie-Lou, plays which had been highly significant in “Québécois cultural expression and even, emancipation” in their original language and context, came “to signify Scottish identity” in their translated versions. It was the extent to which Scottish artists, critics, and audiences could see their own small culture and its struggles reflected in Martin Bowman and Bill Findlay’s translations that was consistently underlined as their primary value, as encapsulated in Scotland-based critic Mark Fisher’s much-quoted epithet that Tremblay is “the best playwright Scotland never had” (Fisher 10). While Bowman and Findlay argue that the fact that the situations represented in Tremblay’s plays resonated in Scotland was proof of the “universal significance” of his work, Harvie worries that the cultural specificities of the Quebec situation may be lost or downplayed in the translated versions; that differences between the two cultures might be “potentially diminished or even erased” along the way; and that both cultures might be objectified or limited by paralleling them. These translations adhered to the above-mentioned paradigm of retaining Quebec names and references, so that Bowman and Findlay’s Germaine Lauzon speaks working-class Glaswegian, leading Harvie to wonder “[w]here and when, precisely [. . .] this [places] the characters in the translations” (13). One could argue that the fact that the plays inhabit two cultures simultaneously renders them “intratextually incoherent”; but, following Homi Bhabha, it is also possible that this “incoherence [fosters] a productive tension between the source and target locations,” which might encourage audiences “to problematize their assumptions about how place determines identity” (14). In Harvie’s final assessment, however, it is difficult to find evidence that the Scottish translations of Tremblay prompted such self-reflexive questioning of received knowledge about place-identity relationships.

15 The practices of translation and production of the Tremblay texts gained considerable media and academic attention because they were, at the time, a new and newsworthy departure. These days, bringing new theatrical writing into a different language and culture has become a more familiar practice, but one, I am arguing, whose intercultural repercussions have not yet been sufficiently interrogated. Like O’Toole, my interest in questions of intercultural engagement goes beyond the finished productions to the material processes of translation and production, and the effects these have on what ends up on the stage. In addition to 1) the involvement of members of all cultures represented in a production, O’Toole’s criteria for ethical intercultural exchange include 2) creative agency and equality granted to all collaborators; 3) advantage given to the least privileged individuals or cultures in the process; and 4) positive socio-political effects of a production within its performance contexts, understanding a positive socio-political effect as one “that challenges rather than re-inscribes hegemonic assumptions about [. . .] Othered cultures and people” (E. O’Toole 44). These criteria were developed as part of a study of collaborative processes in which new work was developed for production, as opposed to the translation and staging of pre-existing plays, as is the case at the Licorne. As such the middle two of O’Toole’s criteria are less relevant here, but the first and last are useful in thinking through a contemporary ethics of translation and production. With all this in mind, we now turn to a consideration of the Licorne’s production of La Reine de beauté de Leenane.

Deep Ireland, deep Quebec

16 As indicated above, the Licorne production team’s treatment of La Reine de beauté focused on the claustrophobic, unhealthy relationship between Mag and Maureen, and understood the play as a realist dramatic comedy. In an interview Faucher said the play was about “aborted dreams and disillusion, and how people get revenge on others when they have suffered a big wound” (qtd. in Perron);10 he observed too that McDonagh “has a sense of characters. In just a few exchanges, he embodies complex and mysterious beings, by putting them in strong and exciting dramatic situations” (qtd. in Giguère).11 Faucher was at the time not known for “by-the-book naturalism” (Guay)12 in his mises en scène; in an interview he explains that his approach to La Reine de beauté was predicated by the text: “The writer brings something very traditional; the direction should reflect the same spirit. There is a realist theatre quality” (qtd. in Perron).13 The Licorne at that point was a rectangular-shaped 180-seat theatre noted for the intimacy between stage and viewers its small size and particular configuration afforded.14 In this case, however, Faucher set the playing area back from the audience and placed a physical frame around the action, saying, “I didn’t want [the spectators] to be able to reach out and touch the objects or the actors. I wished them placed in a voyeuristic position vis-à-vis these women” (qtd. in Giguère).15 The creative team’s commitment to verisimilitude extended to props designer Patricia Ruel travelling to Ireland to shop for set dressings and to “get to know the country a bit better” (Perron).16 Other creative choices denoting the Irish setting included traditional Irish music played during blackouts between scenes (see St-Hilare).

17 Critics responded positively to the production’s realism and the invitation it afforded to invest in the play’s central relationship.17 In his review for Le Devoir, Hervé Guay notes “significant details” such as “porridge, songs on the radio, Australian shows on the TV, the chamber pot, the poker as well as the boiling oil,” which “all contribute to weaving an obsessive microcosm as well as a complex and frightening reality.”18 Marie Labreque in Voir complimented Faucher’s “attentive” direction which “restores [an] atmosphere of oppression” and “presents a powerful duel”19 between Mag and Maureen, while Jean St-Hilaire in Le Soleil praised the actresses’ “strident and incessant truthfulness.”20 Christian St.-Pierre in Jeu described Faucher’s production as having a “blunt naturalism”21 that underlines the sense of claustrophobia and inescapability in the mother/daughter relationship(21).

18 Many of those involved in the production, and most major reviewers, read the play’s central situation as synecdochal of socio-political realities in Ireland—in particular a perceived situation of uneven rural/urban development—and identified parallels to similar socio-economic problems in Quebec. Leduc, reflecting on the production in 2013, said:

19 Guay opens his review by noting that he had been hoping to see a French-language production of Beauty Queen in Montreal, not just because of its dramatic qualities but also for “its possible resonances in a Québec context.” He describes the play’s setting as “deep Ireland” where there is an “atavism that is difficult to deracinate” and where people with small lives, like Maureen, dream ineffectually of escape.23 St-Pierre, reflecting on La Reine de beauté and the Licorne production of Mark O’Rowe’s Howie le Rookie, which has a contemporary urban Irish setting, says that the two plays offer a “city/country frame... [revealing] a dichotomy at the heart of Irish identity, which can’t help but evoke our own.” Rural Ireland as depicted by McDonagh is a “social and cultural context that kills a person’s aspirations at birth [... revealing] troubling similarities between the sociopolitical situation in Québec and that in Ireland.”24 For Labreque, La Reine de beauté, “better than any socio-geographical treatise [. . .] reveals the ravages of acculturation and isolation. Alienation, loneliness, loss of hope, madness, the holding of grudges, the transmission of unhappiness,” themes that are “familiar, but that have rarely resonated with such cruel force.”25

20 The problem of the decline of rural communities in Quebec, and Canada more broadly, had been ongoing for decades at the time La Reine de beauté was staged, and was becoming a cultural talking point: in 2003 the Canadian edition of Time magazine made the “slow death” of Canadian small towns its cover story (see Catto). A 2004 Quebec public health document reported that 21% of all Quebecers lived in rural areas, but that these numbers were dwindling: rural areas lost 1% of their population between 1996-2001, while cities grew 2% at the same time (Martinez et al. iv). Rural areas suffer from lower economic conditions, income levels, and poorer education provision than urban ones, resulting in the interlocking problems of “fragmentation, disaggregation, and marginalization” (3). While the urban/rural relationship clearly represents an important set of social, economic and cultural concerns in Quebec, the subject had not yet become a featured subject of Quebec dramaturgy; it was not until 2011, with the premiere of Michel-Marc Bouchard’s Tom à la ferme at Théâtre d’Aujourd’hui in Montreal, that the relationship between urban and rural Quebec was broached by a leading playwright on an important national stage, within the context of a drama about homosexuality, homophobia, and psychological entrapment.26 Clearly, the themes of uneven development and the psychological and emotional effects of rural isolation in Reine de beauté struck the Licorne and critics alike as original and relevant, and were celebrated in these terms.

Display large

image of Figure 2

Display large

image of Figure 221 Critics struggled, however, to make full sense of the play’s tone and genre. While Guay classed it a “dramatic comedy,” he found some of the instances of humour overplayed, a questionable choice for a play that depicts a situation of subliminal battles and long-simmering rage: “the lines with their very black humour seem intended to briefly lift the lid on the pressure cooker, in my view, not to make us laugh out loud.”27 Labreque praised the play for at once containing “realist tragedy and horrifying comedy,” but found that the character of Ray, as played by Steve Laplante, did not fit with the rest of the play and production because it fell “a bit too much on the side of comedy.”28 Less critically, Blais called the play an “implacable tragedy” that “sometimes makes us roar with laughter” and St-Hilaire called it a “black comedy” that is “cruel and atrociously funny.”29 For St-Pierre, the piece is a “dark comedy”; thanks to the quality of Bernard and Gagnon’s performances it was able to avoid “melodrama or parody.”30

Demythologizing Ireland

22 Such difficulties in making sense of the relationship between comedic and serious elements in the play are an effect of the limitations of reading it as realism. For those familiar with Irish drama and other cultural forms, many aspects of the Leenane plays are extremely familiar to the point of being “clichés of Irishness” (Fitzpatrick 142). The use of a sparsely furnished rural kitchen as setting is “one of the most familiar images from the Irish dramatic tradition” (Lonergan, “Introduction” v), against which an older generation of playwrights including Brian Friel, Thomas Kilroy, Hugh Leonard, and Tom Murphy reacted in their work as early as the 1960s (see Kilroy). The stage directions in the published version of Beauty Queen include detailed instructions about interior decoration: in addition to kitchen furniture and small appliances (radio, TV), they call for a crucifix, a framed portrait of John and Robert Kennedy (revered by older Irish generations as emigrant native sons whose success reflects back positively on the home place), and a “touristy looking embroidered tea towel” hanging on the wall (McDonagh 5). These images, “suggestive of Catholicism, emigration, and impoverishment” help create the “sense,” according to Lonergan, “that everything on stage is overfamiliar” (“Introduction” v). (Significantly, these stage directions are not included in Britt’s translation, perhaps because they were understood as being specific to the Druid Theatre production.) Another key element of the creation of an archetypically Irish scenario is the characters’ use of a “distinctively constructed Hiberno-English dialect” (Pilný 228), to which I will return in my discussion of the Licorne production.

23 Because of these aspects of setting and language, and because McDonagh’s Ireland-set plays treat “constituent themes of Irish culture,” such as “corruption in the Catholic church and religious disillusionment, family violence, miscommunication and loneliness, and obsessive intrusion and lack of privacy in a small rural community” (Powell 138), they insert themselves into a history of Irish plays and other cultural works exploring and interrogating these and other aspects of Irish identity. Many commentators argue that McDonagh’s agenda is knowingly critical, that his plays underline and satirize the extent to which, in Nicholas Grene’s words, representations of “an archaic West of Ireland, sexually unfulfilled, depleted, and demoralised, has remained imaginatively live and theatrically viable well past its period sell-by date” (52). OndȈrej Pilný takes this line of argument further, arguing that McDonagh is not just poking fun at outdated images of Irish culture, but at the critique of these: “McDonagh’s plays progressively satirize the pervasive concern of Irish theatre discourse with the issue of Irish identity, simply by offering an absurd, degenerated picture as a version of ‘what the Irish are like’” (228).

24 This satire is delivered, in Lonergan’s analysis, by the insertion of strange and unexpected elements into this hyper-familiar dramatic world, as when Mag idly comments at the end of the play’s first scene about a man who “up and murdered the poor oul woman in Dublin and he didn’t even know her” (McDonagh 10). More surprising than the random violence of such an event is Mag’s assumption that an intimate would be more likely to kill someone than a stranger. Not only does this foreshadow the end of the play, when Mag dies by Maureen’s hand; it “establishes a clash between the familiar and the strange that persists throughout the play” (Lonergan, “Introduction” vii), which encourages audiences to take a step back from McDonagh’s representations to query the values and veracity of the dramatic world it represents. For Grene, McDonagh’s satire is signalled in the play’s extreme violence (though the audience does not see the act, Maureen kills Mag by clobbering her over the head with a poker) and the exaggeration of its “dystopic [view] of the small Irish town” (45), as when Pato comments that “You can’t kick a cow in Leenane without some bastard holding a grudge twenty year” (McDonagh 27). Grene notes a “cartoon-like gleefulness” and a “grotesque excess in the language that actually reduces its shock value by taking it out of the realm of the real” towards the overall end of “demythologizing Ireland” (46, 45).

Display large

image of Figure 3

Display large

image of Figure 325 The play’s setting and content also nod to a continuum of Irish melodramas set in country kitchens by writers including John McGahern, Louis d’Alton, and John B. Keane (see Wilson 25). As Rebecca Wilson argues, McDonagh “both upholds and inverts the tenets of traditional melodrama” in Beauty Queen, in the presentation of a situation of emotional extremes, with life-changing romantic intrigue revolving around “that archetypal generic device, the letter,” which is stolen in an act of “archetypal treacherous villainy” (33) by the juvenile, conniving, vow-breaking anti-heroine Mag. Comic elements, located in classic melodrama in a “benevolent clown figure” (27), are here woven into the fabric of the dramaturgy. Inversions come in the form of the heroine-as-anti-heroine, Maureen, who, though at points empathetic, is not a figure of goodness to be rescued out of a corrupt world, but rather has been subsumed by her environment and becomes a torturer and murderer. Pato, too, inverts expectations of the romantic hero as saviour: rather, he is “a normal, ordinary man who, unwittingly, is the catalyst that will ignite the catastrophe” (29).

26 Much scholarly and critical attention has also been paid to the Leenane plays’ less-than-straightforward temporality. The Ireland that Beauty Queen depicts seems in many ways archaic; yet other elements, such as reference to significant sporting events, seem to place it in the time of McDonagh’s writing, the mid-1990s. Indeed Shaun Richards, by tracing interconnected references throughout the three plays, definitively states that “the whole Trilogy is set across a matter of months from the summer of 1995 to that of 1996” (203). There is a strong focus in the play on outward migration: Maureen, we discover, suffered a breakdown in her twenties when she was working as a cleaner in Leeds and was verbally bullied by her English co-workers. Pato is, in the play’s real time, a similarly disenfranchised building site worker in London who, in the course of the play, embraces enthusiastically an opportunity to take work in Boston. In the context of early-1990s Ireland, this depiction of Ireland as a country of forced emigration, and of Irish workers in England as subjected to ethnic prejudice, was becoming anachronistic. The transition into the Celtic Tiger period was swift and disorienting, however, and not experienced on equal terms across Ireland. Rural populations lived with active memories of the relative deprivation and isolation that was the sociocultural norm across the country well into the 1980s; and traveling across Ireland from boomtime Dublin into the lagging hinterlands was to experience a sense of time warp. Influentially, the cultural critic Fintan O’Toole characterized early 1990s Ireland as seeming “pre-modern and postmodern at the same time” (279), and championed McDonagh’s plays as a pastiche of 1950s and 1990s references that captured this particular quality of temporal and developmental disconnection.

27 Not all commentators have agreed, however, that McDonagh’s portrayal of Irish culture, including this quality of temporal delay, is sufficiently knowing and self-critical. Vic Merriman, for example, condemns McDonagh’s plays and those of his contemporary Marina Carr as “amoral travesties of contemporary Ireland that have no currency in an urbane present” and which serve as the means for neo-colonial urban Irish audiences to offer “a cathartic roar of relief that all of this is past—‘we’ have left it all behind” (314). Susan Conley critiques Beauty Queen's portrait of Ireland as “simplistic, violent, and dated” (374), while Kevin Barry calls McDonagh’s work “nostalgic viciousness” (qtd. in Fricker, “Ireland” 377). Sara Keating contests these negative assessments, arguing that they insert McDonagh’s work into a “post-colonial discourse of national authenticity completely inappropriate to the postmodern politics of [the] plays” (281). In identifying “the grotesquery, the intertextuality, the parody and pastiche” (289) of the Leenane plays as their defining characteristics, Keating follows in the interpretative path forged by Fintan O’Toole, and argues for globalization as a relevant context for interpreting the plays:

Lonergan extends this assertion, arguing that a broader scope of reference beyond the national is required to appreciate McDonagh’s work and analyse its meanings and effects. Taking the lead from McDonagh’s statements about his influences, Lonergan identifies the work of playwrights including David Mamet, Harold Pinter, Sam Shepard, and Tracy Letts; narrative structures adapted from soap opera; fiction by Borges and Nabokov; popular music including that of the Pogues; and contemporary cinema by auteurs including Tarantino, Scorsese, Woo, Peckinpah, and Malick as the appropriate creative and evaluative context for McDonagh’s work (see Theatre 106-107). Lonergan makes the case that the plays, on one level, are themselves about the struggle to find appropriate models to interpret cultural products in the global age, and that they contain multiple, self-conscious references to “audiences’ willingness to accept [clichéd representations of Irishness] uncritically,” thus “offering a tutorial of sorts on how culture might be understood” (Theatre 121).

Hiberno-English into joual

28 To return to the production of and response to La Reine de beauté in Montreal, however, it becomes clear that knowing interpretation is required to appreciate the complexities of McDonagh’s representations and their potential for meta-cultural critique. The extent to which the artistic direction and production team at the Licorne appear to have accepted the play as a relatively documentary account of contemporary Ireland, without recognizing its exaggerated, satirical, and postmodern qualities is striking. Evidence of this is reflected in the translation, which transfers the play into contemporary, vernacular Quebecois. Translator Britt’s primary tool for localising the play’s language is the frequent use of distinctly Quebecois expressions, contractions, and phrases, such as “y” for “il,” “ben” for “bien,” “pis” for “puis,” “c’est-tu” for “Est-ce que,” “astheur” for “now,” and “coudonc” for “Écoute, donc” amongst others (see Britt 3-14).31 She frequently inserts English words and Anglicisms into the dialogue, for example translating the word “feck” (an Irish euphemism for “fuck”) as “shit,” retaining the word “job” in English, and calling a second-hand car a “seconde-main” (Britt 3-14). This combination of Anglicisms and “expressions drawn from a French Canadian lexicon” (Beddows 13) identifies Britt’s language as a contemporary, less heightened version of joual, the French “spoken in Montreal, which is very urban and very influenced by the presence of the majority of the English population that lives in and around Montreal” (Gaboriou qtd. in Beauchamp and Knowles 46).32 The urban associations of the language of translation distance the play from the rural setting that was otherwise communicated through the play’s content and physical setting.

29 A close reading of the opening passage against McDonagh’s original demonstrates some further qualities of Britt’s translation:

| MAG: Es-tu mouillée, Maureen? | MAG: Wet, Maureen? |

| MAUREEN: Ben oui, je suis mouillée. | MAUREEN: Of course wet. |

| MAG: Oh-h. | MAG: Oh-h. |

| Maureen enlève son manteau en soupirant et commence à ranger l’épicerie. | Maureen takes her coat off, sighing, and starts putting the shopping away. |

| MAG: J’ai pris mon Complan. | MAG: I did take me Complan. |

| MAUREEN: T’es capable d’en faire toute seule! | MAUREEN: So you can get it yourself so. |

| MAG: Ben oui. (Temps) Mais y était plein de grumeaux, par exemple, Maureen. | MAG: I can. (Pause.) Although lumpy it was, Maureen. |

| MAUREEN: C’est-tu de ma faute, si y a des grumeaux? | MAUREEN: Well, can I help lumpy? |

| MAG: Non. | MAG: No. |

| MAUREEN: Écris-leur, à Complan, si t’es pas contente. | MAUREEN: Write to the Complan people so, if it’s lumpy. |

| MAG: (Temps) Y es tellement meilleur quand c’est toi qui le fait. (Temps). Pas de grumeaux, même pas l’ombre d’un grumeau. | MAG (pause): You do make me Complan nice and smooth. (Pause.) Not a lump at all, nor the comrade of a lump. |

| MAUREEN: C’est parce que tu le brasses pas assez. | MAUREEN: You don’t give it a good enough stir is what you don’t do. |

| MAG: Je l’ai brassé en masse pis y avait encore des grumeaux. | MAG: I gave it a good enough stir and there was still lumps. |

| MAUREEN: Tu verses probablement l’eau trop vite aussi. Y le disent sur la boite, y faut y aller au fur et à mesure. | MAUREEN: You probably put the water in too fast so. What it says on the box, you’re supposed to ease it in. |

| MAG: Mm. | MAG: Mm. |

| MAUREEN: C’est ça que tu fais pas correct. Essaies encore, ce soir, tu vas voir. | MAUREEN: That’s where you do go wrong. Have another go tonight for yourself and you’ll see. |

| MAG: Mm. (Temps). Pis j’ai peur de l’eau chaude aussi. Peur de m’ébouillanter. | MAG: Mm. (Pause.) And the hot water too I do be scared of. Scared I may scould meself. |

In the original, Mag and Maureen’s dialogue is written in exaggerated Hiberno-English, which is a “macaronic dialect, a mixture of Irish and English, sometimes in the same word” (Dolan xxi), and sometimes communicated via the adoption of Irish grammatical patterns using English words.33 Mag’s unusual word ordering (“lumpy it was”, “the hot water too I do be scared of”) reflect Irish sentence construction, which does not observe the same subject-verb ordering rules as in English; and the use of the habitual form of the present tense (“do be scared”) is characteristic of the Irish language. Both characters employ the Hiberno-English tactic of “clefting,” that is, placing a key word or phrase “in the ‘hinge’ position of a sentence” (Filppula 52), as in Maureen’s “You don’t give it a good enough stir is what you don’t do” and Mag’s “And the hot water too I do be scared of.” We can also observe McDonagh’s frequent use of other Hiberno-English tropes such as the insertion of “so” as a “distinctive intensifier” (Dean 32) and the replacement of “my” and “myself” with “me” and “meself,” and later in the play the addition of the Irish suffix “een” onto English words, transforming “bit” into “biteen,” for example (8). As Terence P. Dolan notes, such features of Hiberno-English are particularly associated with “the older generation, particularly those from rural areas,” while younger, urban Irish populations tend towards “newly cast words and adaptations” (xxi). While everyday speech in contemporary rural Ireland might feature some of these linguistic elements, the amount and frequency of them here is extreme, almost relentless, and seems clearly part of McDonagh’s strategy to defamiliarize this dramatic world and to communicate humour and satire. In almost every instance, however, Britt’s translation normalizes these linguistic particularities into standard sentence order and conjugation: subject-verb constructions are straightforward, clefting is not observed, and no equivalents are attempted for “so” and “me/meself.”

30 Britt is more successful in her apprehension and duplication of McDonagh’s use of the “the verbal tic of repetition,” which “[slows] down the dialogue, creating these largely meaningless, ludicrous, and banal exchanges that may, nonetheless, be charged with rage and hatred and bitterness” (Fitzpatrick 149). We see this in this passage in the repetition of “lump” and “lumpy” six times, “Complan” three times, and “good enough stir” two times, nearly all of which Britt replicates. McDonagh has identified the work of Harold Pinter as a key inspiration and stylistic influence, which we see reflected in these frequent passages of “small talk” that “[undermine] the traditional expectations of external action moved forwards through speech acts” (Aston and Savona 66). While McDonagh deftly introduces key points about plot and character even in this brief passage—by the final line he is already setting up, for example, the backstory that Maureen has previously scalded Mag’s hand with hot water—he does so in the context of repetitive, looping exchanges that communicate the tedium and banality of the characters’ life together.

31 In other places, however, Britt’s translation shows signs of lack of comprehension, for example in her misunderstanding of the very first exchange as being about Maureen’s physical state as a result of the weather, not the weather itself. In Ireland, a rainy day can be called a “wet” day, and a truism about the Irish climate, particularly that in the West of Ireland, is that it is very wet indeed; in the real-life Leenane, it rains two out of three days a year (Lonergan, “Introduction” vi). This is humorously reflected in the abbreviated nature of Mag’s query, to which Maureen responds equally briefly and fatalistically, neither even bothering to include subject and verb. Lonergan argues that the exchange further establishes character, theme, and tone in that Mag’s question “instantly reminds Maureen of an almost unbearable truth. Her life has fallen into a pattern in which one day is exactly like the next: wet, dull, grey—hopeless” (“Introduction” vi). Because, it seems, of the omission of the subject-verb construction, Britt misunderstands the exchange and not only misrepresents its meaning, but misses out on both the establishment of theme and tone as well as on the joke.

32 The translation, then, while capturing the circular and repetitious nature of the characters’ exchanges, presented the play in urban-tinged contemporary language, hinting little at the satirically exaggerated qualities of McDonagh’s original script. What might have seemed a disconnect between the rural setting and the somewhat urban linguistic world had the effect of making the material feel familiar to critics, which St-Pierre identifies as a particular value: “We have the strange impression of being in known territory, right in the heart of the Republic of Ireland.” Similarly Blais admires the translation for achieving an “equilibrium between a very Québécois language and a very Irish universe,” while St-Hilare compliments it for being full of “Québécois irony.” The next interpretative step for several critics was to understand the play as offering information about Ireland’s relationship to Britain, and to liken this to Quebec’s own postcolonial situation. Such readings are cued, it seems likely, by the Licorne’s particular interest in plays that offer domestic situations as synecdoche for larger cultural/national ones, and enabled by an interpretation of the play that does not acknowledge its generic precedents in melodrama, its parodic and satiric elements, nor its knowing invocation and deconstruction of familiar aspects of Irish culture. Missing these interpretative cues, critics attached significance to the central characters as stand-ins for postcolonial national relationships.

33 St-Pierre argues that the play’s depiction of “the syndrome of isolated regions cultivating the myth of the big city is superimposed with a sentiment of inferiority and cultural invasion from Great Britain.”34 As do several other commentators, Labreque directly connects her understanding of McDonagh’s Ireland to Michel Tremblay’s Quebec:

By drawing comparison to Tremblay’s Quiet Revolution-era drama À toi pour toujours, ta Marie-Lou, whose profoundly unhappy parental characters Leopold and Marie-Louise are widely understood as “a metaphor for a Québec of the past” (Siag),36 Labreque makes clear her understanding of La Reine de beauté as representing Ireland’s relationship to its colonial history. In this reading, Mag is the oppressive, seemingly inescapable past, while Maureen is representative of the new Ireland, struggling to move forward. The title of a La Presse feature article by Éve Dumas—“Maureen, l’enfant martyre”—makes another telling comparison, by likening Maureen’s situation to that of Aurore Gagnon, the abused girl whose story, dramatised in a 1928 play and a 1951 film, became emblematic of the repressiveness and corruption of pre-Quiet Revolution Quebec. Similar to Labrèque, Dumas invites potential viewers to see La Reine de beautéas a “metaphor for the Irish people’s quest for identity and freedom,”37 a reading that, pushed to its limits, casts Mag as a stand-in for British dominance of Ireland.

34 Labreque and Dumas thus communicate understandings of Ireland as in a relatively early stage of national articulation, actively struggling to assert itself against the still-looming intimidation of its former colonizer and neighbour. However, as the preceding discussion has explicated, Ireland’s political, socio-cultural, and economic situations are more advanced than such readings imply. While Ireland’s postcoloniality remains a factor in national identity formation, particularly as regards the Northern Irish situation, these readings understand Ireland as locked in an agonistic struggle with Britain when modern and contemporary realities under the conditions of globalization are considerably more complex. The play itself expresses these complexities in its presentation of the United States as another site of identity construction and projection for Ireland (via, in particular, Pato’s eventual move to Boston), and in its layering of references to Australian soap operas and international sporting events onto the seemingly dated and anachronistic country kitchen setting. Further concerns about a grasp of current Irish realities are raised by Dumas’s assertion that plays by McDonagh and O’Rowe represent “the new dramaturgy of a minority population in revolt,”38 a statement that reunites Great Britain and Ireland as a single political entity, or at least understands them as part of the same culture, nearly eighty years after Ireland achieved independence.

35 A result of this critical reception, then, was that dated and inaccurate information about the source culture was disseminated into the Quebecois public sphere. Returning to Emer O’Toole’s criteria for materially and ethically engaged interculturalism, this can be considered a negative socio-political effect of the production in that it re-inscribes rather than challenges “hegemonic assumptions about [. . .] Othered cultures and people” (44). Ireland is constructed in this critical response as a nation still abject and under the thumb of Britain, a response apparently intended as one of solidarity but which has the effect of representing Ireland as considerably less empowered and developed than is the case. This inability to fulfill one criteria is a direct effect of not fulfilling another, that being the inclusion of “members of all cultures represented” in a production. McDonagh’s text was understood as reliably representative of Irish culture when it required knowing gloss and interpretation. Consultation with expert/s on Irish culture could have provided the Licorne with a clearer understanding of the rapidly changing Irish milieu and the not-straightforward ways in which it provides a context for McDonagh’s plays. This could have informed creative and production choices as well as provided useful content for materials such as programme notes and an education dossier. In a discussion of the production and reception of McDonagh’s plays in Japan, Hiroko Mikami argues against providing such context, arguing that “this kind of information on the ‘Irish’ background deludes the audience into thinking they have seen and experienced the ‘real Ireland,’ when they haven’t” (22). But surely there are multiple levels of “reality” at play in these exchanges, and audiences can be credited with sufficient interpretative ability to process an intelligent presentation of the Irish background and context while appreciating that what is presented on stage is not intended as documentary.

36 As Harvie has argued, intercultural exchanges may be motivated by, amongst other factors, the desire for “cultural reassurance and empowerment through identification” and “the potential destabilization of national identity as a defining, and potentially isolating, cultural institution” (19). This is certainly the case with the Licorne’s translations of Irish and other international plays. Such exchanges also run risks, including the “reinforcement of assumptions about [both cultures’] cultural oppression” and the “depoliticization” of the source culture as focus shifts to the resonances of plays in the target environment. The Licorne production of La Reine de beauté fell prey to such risks. Cued by the Licorne’s produc- tion history and this production’s representational strategies, these critics took as their interpretative crux point an understanding and celebration of similarities between the source and target cultures. Many Quebecois critics’ comments imply that the situation of continued socio-cultural domination and cultural insecurity perceived in McDonagh’s Ireland is also present in today’s Quebec, and that part of the play’s value resides in the mirroring effect it offers to Quebec audiences. Solidarity or reinforcement was seen to reside in its offer of evidence that conditions of postcolonial identity struggle in Quebec were being experienced elsewhere. Certainly, as we have seen, questions of uneven urban/rural development in Quebec were topical at the time of production. But is Quebec still the “land of Marie-Lou”? Such self-description brackets out Quebec’s own complex, ongoing experience of globalization and diversification as well as the exceptional performance of its artists and companies in the global cultural arena (See Harvie and Hurley; Fricker “Tourism”; Schryburt “Quebec Theatre”). Not only does the particular interpretation of McDonagh’s play rest on, and perpetuate, a limited and dated understanding of Irish culture and Ireland’s socio-political realities, then, it risks reinforcing a sense of socio-political disenchantment in Quebec by locating solidarity in the position of still-victimized postcolonial subject-nation.

Conclusion: Ireland and Quebec in intercultural dialogue

37 Several initiatives undertaken in the past fifteen years have created occasions for direct exchange between Quebecois playwrights, translators, and producers and artists from English Canada and other cultures. Since 1998, Playwrights Workshop Montréal (PWM) has run a translation workshop in Tadoussac, a town in the Côte-Nord Manicouagan region of Eastern Quebec, in the home of the late translator Bill Glassco. At these sessions, translators (who are, in the PWM and CEAD model, usually active and produced playwrights themselves) work face-to-face with playwrights in what the initiative’s director, Gaboriau, calls a “cultural exchange experience” (qtd. in Beauchamp and Knowles 44). In its second incarnation the PWM translation workshops at Tadoussac included two Irish writers whose work was translated into French;39 since that time the focus has been primarily on bringing Quebecois texts into Anglo-Canadian translation and vice versa (see Playwrights’ Workshop Montreal).

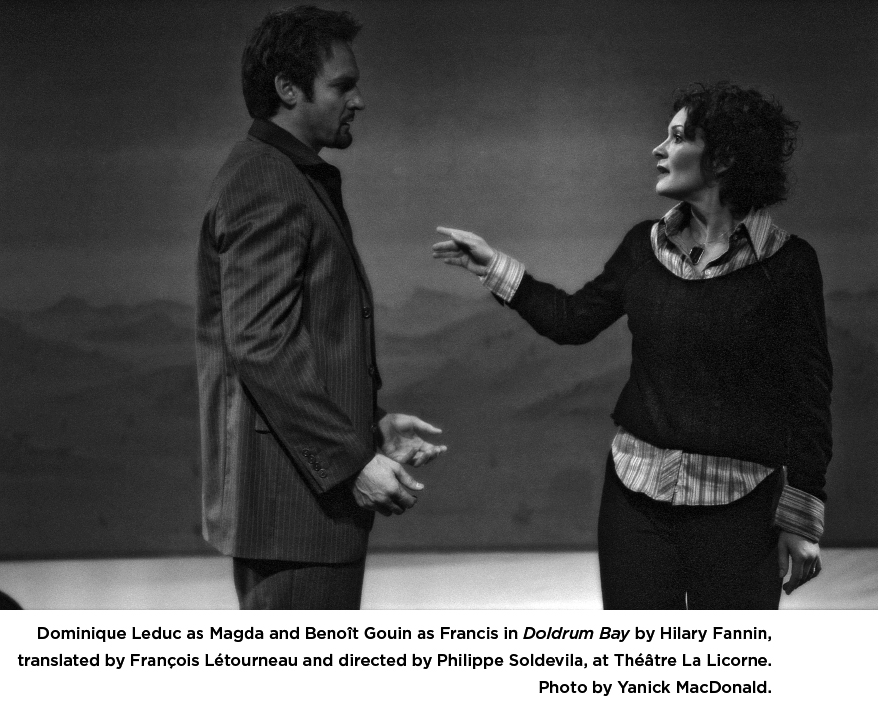

38 Since 1998, CEAD has run frequent residence-based writing and translation workshops which assemble “six to eight writers and/or translators with personal projects who wish to benefit from the support of dramaturgs” (Centre des Auteurs Dramatiques). In 2003 as part of this initiative, CEAD joined with Ireland’s Abbey Theatre to enable the translation of several Irish and Quebecois plays, with each project involving dialogue between the writer, translator, and two dramaturgs, one from each side of the exchange. Jean-Denis Leduc was part of the committee that selected Hilary Fannin’s Doldrum Bay for translation, and the Licorne produced the play in 2004. The dialogue enabled by the CEAD/Abbey residency allowed discussion of both the resonances of Doldrum Bay in a Quebec context, and recognition of significant differences between the Quebec and Irish situations. A central plot point in the play is an opportunity dangled before two struggling forty-something Irish advertising executives to devise a campaign to resuscitate the reputation of the Christian Brothers, a darkly satiric reference on Fannin’s part to the ongoing crisis of confidence in the Catholic Church following revelations of clerical sexual and other abuses. Translator François Létourneau comments that while this element of the play resonates in Quebec, it does so at something of a temporal distance:

Display large

image of Figure 4

Display large

image of Figure 439 Fannin’s play, quite unlike McDonagh’s, is notable for its lack of specific references to Ireland beyond the central plot point of the Christian Brothers campaign. It is never overtly acknowledged that the play takes place in Ireland; most of the characters’ names (which were retained in Létourneau’s translation) do not sound particularly Irish; and there are few cultural references that identify it as being connected to any particular place. The characters speak in fast-paced, overlapping dialogue, which, while peppered with the odd Hiberno-English phraseology, feels almost parodically North American; Létourneau’s translation into contemporary colloquial Quebecois (not dissimilar to that of Britt’s translation of Reine de beauté) suitably captures the dialogue’s urban, internationalized feel. The context of the play, then, and one of its key themes is globalization itself, that is, the sense of loss of identity (national and personal) and rootlessness that can be a by-product of our globalized times. Nearly every Montreal reviewer understood the play as being about very relevant, but culturally unspecific themes, primarily forty-something life crises and the predominance of consumer culture in contemporary society. Only two reviewers of the Licorne production made mention of connections they noted between the Ireland of Fannin’s play and today’s Quebec, and used them as opportunity for reflexive contemplation, as with David Lefebvre’s review on montheatre.qc.ca:

The example of Doldrum Bay reflects the positive ways, then, in which intercultural exchange between source culture and target culture can lead to translations that transmit the particular qualities and meanings of the original text. Following on from the exchanges between playwright, translator, and dramaturgs, Létourneau’s translation transmitted key qualities (urbanity, lack of cultural specificity, satire) of Fannin’s original, which were further communicated in Philippe Soldevila’s production. Cued by the production, critics did not dwell on the play as a mimetic reflection of contemporary Ireland but rather as offering a “portrait of a generation” in general terms.41 The presence of representatives of all implicated cultures led to the positive socio-political effect of a translation and production that reflected a rapidly changing Ireland in terms that appeared to be understood and appreciated. Such translation exchanges represent a positive practice that might productively be modeled in other intercultural exchanges on Quebec’s, and other, stages.