This article examines how La Tempête, a 2011 collaboration between Robert Lepage’s theatre company, Ex Machina, and the Huron-Wendat Nation on the Wendake First Nations reserve, fostered moments of productive interculturalism both on stage and off through what I have termed scenographic dramaturgy. Lepage’s process of scenic re-“writing” responds to the evocative potential of individual performer bodies and a production’s given physical location to craft a postdramatic adaptation rooted in highly physical and visual performance text. This analysis draws on intercultural theory, scenographic dramaturgy, postcolonial theory, and postdramatic adaptation and includes a brief survey of Quebecois and First Nations Shakespeare productions in Canada, highlighting some of the potential traps of staging postcolonial interpretations, including power imbalances among intercultural collaborators and reductionist portrayals of difference. Ex Machina and the Huron-Wendat Nation’s ability to avoid many of these traps will be interrogated through examples illustrating how scenographic dramaturgy’s three central components—bodies in motion, architectonic scenography, and historical spatial mapping—function as both a process and product fostering progressive dialogue between cultures.

En 2011, la compagnie Ex Machina de Robert Lepage s’associait à la Première Nation huronne-wendat de Wendake pour une production de La Tempête. Cet article examine comment cette collaboration a donné lieu à des moments d’interculturalisme productifs tant sur scène qu’en coulisses grâce à ce que Melissa Poll appelle la « dramaturgie scénographique ». En effet, la ré-« écriture » scénique de Lepage met à profit le potentiel évocateur du corps de chaque interprète et l’emplacement du spectacle, afin de produire une adaptation postdramatique enracinée dans un texte scénique très visuel et physique. Puisant aux études interculturelles, à la dramaturgie scénique, aux études postcoloniales et à l’adaptation postdramatique, cette étude propose un bref survol des productions québécoises et autochtones de pièces shakespeariennes au Canada afin de mettre en évidence quelques pièges que pose la mise en scène d’interprétations postcoloniales, notamment un éventuel déséquilibre dans le rapport de force entre les collaborateurs interculturels et une représentation réductrice de la différence. Dans cet article, l’auteutre tentera de voir si Ex Machina et la Première Nation huronne-wendat ont su éviter ces écueils en examinant divers exemples qui illustrent le fonctionnement des trois composantes centrales à cette dramaturgie scénique—les corps en mouvement, la scénographie architectonique et la cartographie historico-spatiale—qui, en tant que procédés et produits, encouragent le dialogue entre cultures.

1 In 2009, Konrad Sioui, Grand Chief of the Huron-Wendat Nation in Wendake, Quebec, decided that the province’s recent 400th anniversary marked the right time to organize an event between First Nations peoples, Quebecois, and Canadians acknowledging the country’s colonial past. Initially, he proposed a re-enactment of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, the seminal conflict in which British forces defeated French and Indigenous soldiers to conquer New France. Due to threats of violence from extreme separatist groups in Quebec, though, the performance was cancelled. Undeterred, Sioui proposed a symbolic ceremony on the Plains of Abraham; he envisioned a diverse gathering of Canadians to literally bury hatchets and sign friendship treaties (Boivin). Parti Québécois leader Pauline Marois responded by calling on Ottawa to surrender the Plains to Quebec (Dougherty) and proposed a debate on the meaning of the historic battle instead. While independent artists eventually organized a twenty-four hour spoken-word festival on the Plains, a separatist doctrine read at the event caused tempers to flare.2 Ultimately, Sioui’s vision of a reconciliatory gathering failed to materialize. Two years later, however, through the pairing of the Huron-Wendat Nation and the Quebecois theatre company Ex Machina, helmed by director Robert Lepage,3 a French language production of The Tempest recognizing colonialism’s repercussions for Indigenous peoples took centre stage at the Wendake amphitheatre. Drawing from my experience attending La Tempête’s invited dress rehearsal on 1 July 2011, as well as interviews with members of the production team, reviews and scholarly assessments of the work, this article posits that the Wendake Tempêtefeatured instances of progressive interculturalism.

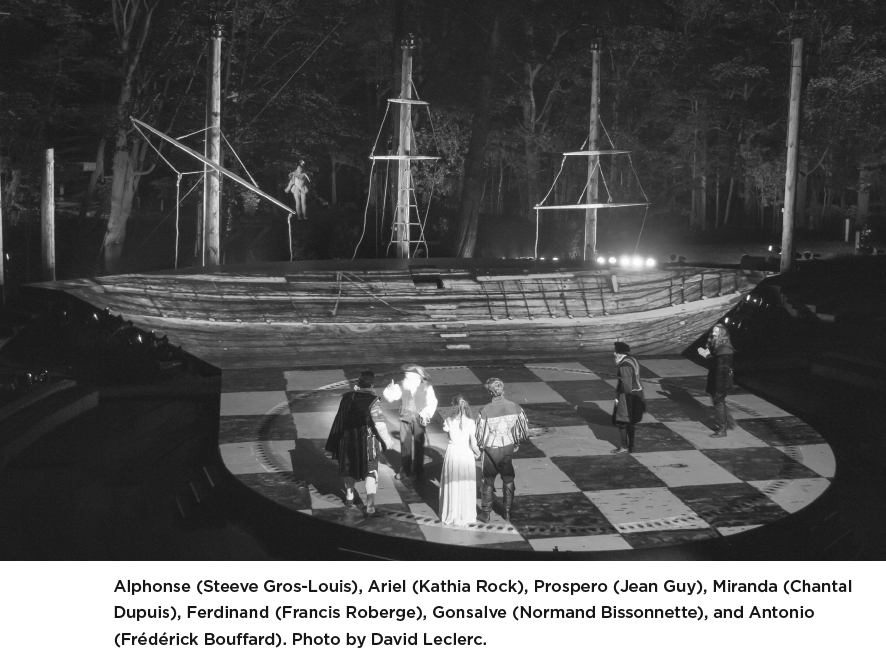

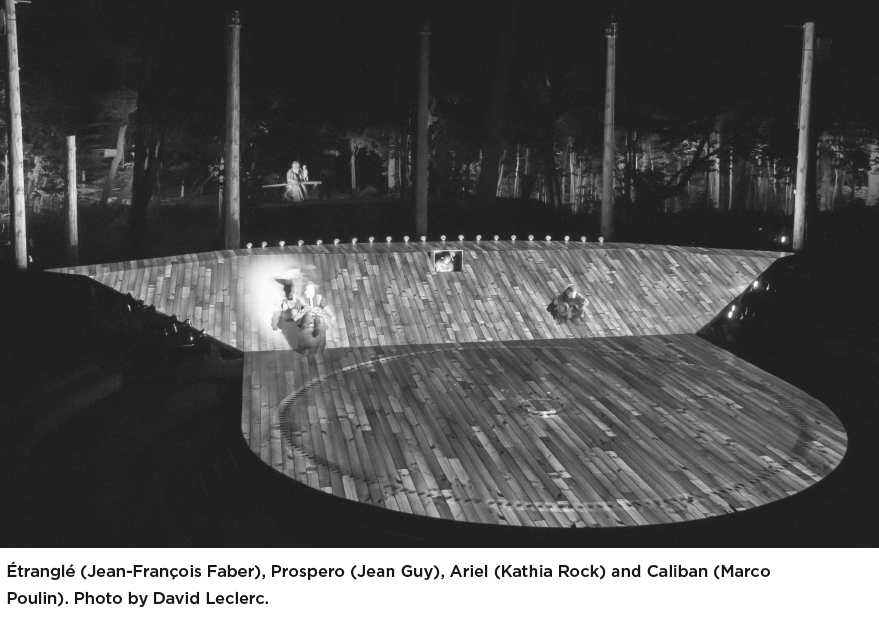

2 Inspired by Joseph Légaré’s painting of the English actor Edmund Kean performing Shakespeare soliloquys in nineteenth-century Wendake and the bond Kean subsequently formed with members of the Huron-Wendat Nation,4 the Ex Machina/Huron-Wendat production of La Tempête endeavoured to forge an alliance between First Nations people and Quebecois artists (Isabelle). Staged on the Huron-Wendat reserve outside Quebec City, the production brought together Ex Machina’s creative team and a group of ten First Nations artists, among them Innu singer Kathia Rock (Ariel), Métis actor Marco Poulin (Caliban) and the Sandokwa Dance Troupe,5 composed of seven Huron-Wendat adults and children, including the troupe leader Steeve Gros-Louis, who also played Alphonse.6 This article examines how La Tempêtefostered moments of productive interculturalism both on stage and off through what I have termed scenographic dramaturgy. By this I mean Robert Lepage’s process of scenic re-“writing” that responds to the evocative potential of individual performer bodies and a production’s given physical location to craft a postdramatic adaptation rooted in highly physical and visual performance text. By overwriting The Tempest’s island setting with the socio-political context of New France in 1608, La Tempêtereconfigured power structures to re-envision Shakespeare’s text. I recognize that the production’s use of a colonial setting was in no way a trailblazing strategy7 and that La Tempêtedid not entirely escape the problematic politics of representation that have marked Ex Machina’s past productions.8 However, my primary focus is on how Lepage responded to his First Nations partners and the surrounding environment to collaboratively craft scenographic dramaturgy that gestured towards recognizing the repercussions of colonialism. In a province where cultural protectionism has led to xenophobic policies,9La Tempête’s burgeoning yet flawed interculturalism merits investigation.

3 This essay begins with a brief outline of the central fields driving my analysis: intercultural theory, scenographic dramaturgy, postcolonial theory, and postdramatic adaptation. A survey of early contact-themed Shakespeare productions in Canada will follow, highlighting some of the potential traps of staging postcolonial interpretations, including power imbalances among intercultural collaborators and reductionist portrayals of difference. Lepage’s ability to avoid many of these traps by working collaboratively will be interrogated through examples illustrating how scenographic dramaturgy’s three central components—bodies in motion, architectonic scenography, and historical spatial mapping—function as both a process and product fostering progressive dialogue between cultures.

4 I have termed Lepage’s use of highly physical and visual performance texts scenographic dramaturgy10 as it re-envisions dramatic texts through the materials of scenography, including scenic environment, costumes, light, sound, space, and time. Because body texts are also central to crafting this visual score, there is a risk that physical performance texts will act as mere ornamentation fashioned for Western consumption, particularly if Indigenous performers are involved. When collaborating with performers on embodied scenography, Lepage works with an eye to the agency of individual performers, resulting in largely self-determined scores. In rehearsals for Wagner’s Ring cycle at the Metropolitan Opera, I witnessed first hand how he encouraged acrobats and dancers to co-author their own particular corporeal scores for performance, whether based in dance, circus tumbling or acrobatics. The second component of scenographic dramaturgy, historical-spatial mapping refers to the overwriting of a dramatic text’s given setting with one or more political-cultural contexts defining another time and/or place. This principle goes beyond a simple aesthetic transposition from one physical setting to another to invest in the zeitgeist of the new environment. For its part, architectonic scenography is based on Edward Gordon Craig’s concept of a living scenic environment that transforms, either independently or via a kinetic dialogue with the performer’s body, to evoke a series of different architectural and/or compositional configurations.11 Collectively, the tenets of scenographic dramaturgy reflect Bertolt Brecht’s understanding of the “importance of mise en scène not merely as a way of representing a text but as a language in its own right” (Whitton 243).

5 The upsurge in theatre hinging on physical performance texts, particularly as explored in Hans Thies-Lehmann’s Postdramatic Theatre,12 contextualizes this study’s understanding of adaptation. Because scenographic dramaturgy de-hierarchizes the dramatic text over its scenic counterpart and understands mise en scène as a language in its own right, it is presented here as a process of adaptation. As highlighted by Daniel Fischlin and Mark Fortier, adaptation occurs “not only between verbal [or dramatic] texts, but between singing and speaking bodies, lights, sounds, movements and all other cultural elements at work in theatrical production” (7). Though the Wendake staging of La Tempête uses Michel Garneau’s 1970s language-based “tradaptation,”13 this study focuses on the cultural and political repositioning resulting from the production’s scenographic dramaturgy. Adaptations and source texts are understood here as existing “laterally not vertically” (Hutcheon xv); spoken text is not privileged over other forms of performance text, including those that speak without words through physical, aural and/or architectural language.

6 A collaborative project between the Huron-Wendat Nation and Ex Machina employing an implicitly imperial dramatic text to engage with Quebec’s colonizing/colonized past and the Huron-Wendat Nation’s position within this history, La Tempête lends itself to a reading employing both intercultural and postcolonial theory. Following the definition of intercultural theatre, the production stages a point of contact between cultures, a site “for the continuing renegotiation of cultural values and the reconstitution of individual and community identities and subject positions” (Knowles 5). As seen in the work of Antonin Artaud and Peter Brook, however, intercultural theatre tends to hinge on the aesthetics of the exchange without engaging a culture’s attendant historical, political or geographical context. “With its insistent stress on historicity and specificity, postcolonial theory offers ways of relocating the dynamics of intercultural theatre within identifiable fields of sociopolitical and historical relations” (Lo and Gilbert 44). By employing postcolonial theory in my analysis, I am able to explore how La Tempête creates opportunities for Quebecois and First Nations performers to talk back to Shakespeare, known in Quebec as “le grand Will” due to his simultaneously revered and imperially-thorny position (Lieblein 178). Whether through physical performance text or the decentring of Shakespeare to question Aboriginal and Quebecois relations within the nation-state of Quebec, La Tempête is a clear site of intercultural contact interwoven with postcolonial theory’s historicizing context. My questions of this collaboration include: Who benefits? Who has agency?

Contextualizing La Tempête

7 Broadly speaking, La Tempête has a number of Canadian forerunners. In terms of Quebecois productions relying on scenography to interrogate intercultural politics, Robert Gurik’s Hamlet, Prince du Québec satirized prominent Anglo and Quebecois politicians via caricature-style masks in 1968. In the 1990s, a number of provincial immigrés, including Oleg Kisseliov, Alexandre Marine, and Paula de Vasconcelos began to stage highly visual, postmodern Shakespeare adaptations in response to their personal experiences of alienation and Quebec’s cultural protectionism (Lieblein 184-88). Various First Nations companies have also employed Shakespeare as a vehicle to examine contemporary struggles within their communities. Shakespeare in The Red, a Winnipeg-based touring company, and the Manitoulin Island group De-ba-jeh-mu-jig Theatre, whose work has served as outreach for at risk Aboriginal youths, have employed Shakespeare’s texts to positively assert Aboriginal identity. For his part, Yves Sioui Durand runs the only francophone Aboriginal theatre company in Canada, Ondinnok, and wrote Hamlet le Malécite about a young First Nations man struggling with his racial identity. Toronto’s Native Earth Performing Arts, a company dedicated to Aboriginal performance, has also adapted Shakespeare. Yvette Nolan and Kennedy C. MacKinnon’s Death of A Chief offers an all-Aboriginal adaptation of Julius Caesar that explores gender roles and band politics.

8 As the first early-contact themed Shakespeare adaptation driven by a francophone Quebecois company, the Wendake Tempête can also be contextualized via productions that demonstrate the potential challenges of setting a Shakespeare text in colonial Canada. Created for the Canadian Players in 1961, David Gardner’s touring production of King Lear presented Shakespeare’s narrative through portrayals of Inuit people struggling with French. colonization. Characters were played by white actors clad in “mukluks and snow goggles” (Grace 143), trafficking in reductive and essentialist portrayals. In the late 1980s, a more progressive early-contact themed production appeared—Lewis Baumander’s postcolonial Tempest in Toronto’s Earl Bales Park. Set on the Queen Charlotte Islands at the time of Captain James Cook’s arrival, Baumander’s Tempest cast Ariel and Caliban as Haida, played by Monique Mojica of the Kuna and Rappahannock Nation and Cree performer Billy Merasty (Peters 197). This production has been critiqued for failing to include Aboriginal designers, reinforcing imperialist ideology, and subjugating First Nations characters (Buntin); nonetheless, Mojica’s defiant Ariel highlighted Prospero’s “otherwise uncontested assumptions of symbolic legitimacy” (Bennett 140) and the masque scene was effectively interventionist, portraying a potlatch in which European guests “from hell… initiated the death of native peoples and the destruction of their culture” (Gilbert and Tompkins 27).14

Display large

image of Figure 1

Display large

image of Figure 19 As posited by Lo and Gilbert, the actual ground occupied by an intercultural performance speaks, in part, to the power dynamics at work within the collaboration:

10 Having spent a good deal of time in Wendake when he was a child, thanks to an aunt’s home bordering the reserve (Desloges), Lepage had envisioned collaborating with the Huron-Wendat Nation for years (P. White). Since inheriting this home in the last decade, the Quebecois director has taken up residence there whenever possible (Desloges), attending pow-wows and participating in local events.15 Out of respect for the Huron-Wendat people, La Tempête was expressly crafted and framed as a site-specific performance that would not tour internationally, a marked departure from Ex Machina’s usual production model.

11 The conceptual framework for La Tempête also demonstrated a shift in Lepage and Ex Machina’s focus, featuring a level of political consciousness and provocative questioning sometimes apparent in Ex Machina’s Quebecois-centered narratives but never before featured in their engagement with a minority group outside the francophone Quebecois. Given Lepage’s problematic past with the politics of representation, including various instances of marked Orientalism and the strident use of blackface in Zulu Time, his staging of an interventionist Tempest on the Wendake First Nations reserve signals a politically progressive step in Ex Machina’s work. The often fraught history of Quebecois/Aboriginal land disputes, punctuated by events such as the Oka crisis,16 further contextualizes La Tempête as produced on Huron-Wendat ground; not only did the performance challenge Ex Machina’s ways of working but it also confronted long-standing cultural tensions surrounding land ownership in Quebec.

La Tempête’s Historical-Spatial Mapping

12 New France’s founding of North American colonies in the seventeenth century, which coincides with Shakespeare’s writing of The Tempest, was aesthetically layered onto La Tempête’s actual setting on the Huron-Wendat reserve in 2011. As confirmed in La Tempête’s program, to establish a fairytale aesthetic in production (Ex Machina), the production turned to the utopic images of New France created in the nineteenth century by the nationalist Quebecois painter Joseph Légaré. The results were significantly interventionist; La Tempête substituted Shakespeare’s vision of colonial Britain with an idyllic view of New France, set prior to the British invasion. In this way, Lepage knowingly romanticized the entire visual world of the production, not just the Aboriginal characters, giving spectators more to consider than the aesthetic “traditions” of one group fetishized for the Western gaze. By emulating the visual world of Légaré’s colonial paintings in production, which cast First Nations people and the inhabitants of New France as the period’s principal protagonists (S. Garon 54), La Tempête visually edified a mythology, albeit a Western one, which speaks to an alliance between First Nations People and the Quebecois.

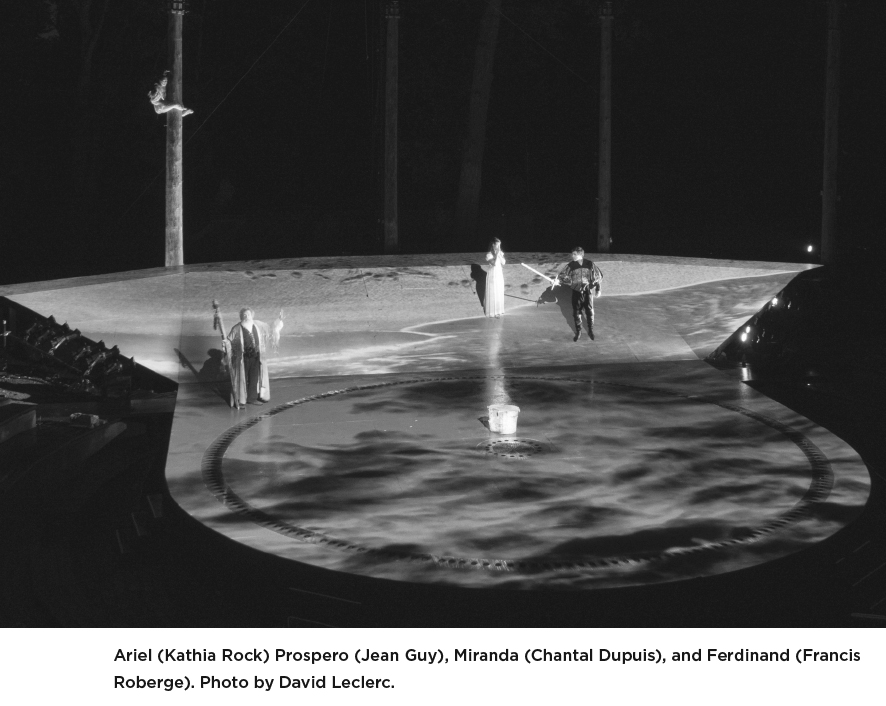

13 Nowhere was the Wendake Tempête’s material representation of this alliance more evident than in its costumes. Légaré’s painting “Josephte Ourné” (which appeared in La Tempête’s program) offers a clear example of how the artist aligned Europeans and Aboriginals through an aesthetic hybridity. Referred to by Légaré as the daughter of an unknown First Nations chief, Ourné wears an elaborate coat echoing seventeenth-century Western fashion, while her accessories, including glass beads and a feather, signal First Nations iconography. Ariel’s costume features a similar interweaving of First Nations and European aesthetics. By counterbalancing a doublet and Renaissance pumpkin pants with a leather corset and feathers, costume designer Mara Gottler married European fashion with iconic “Indian” accessories, purposely suggesting an essentialist European perspective. Prospero and Miranda’s costumes also follow on Légaré’s worldview, appearing as if filtered through Prospero’s nostalgic gaze, meant to mythically unite the old world and the new. In an email exchange, Gottler commented: “We were trying to evoke what Prospero remembered of his past court life as reinterpreted through his present life experience.” Clothed in an immaculate white shift that in no way indicated the wear and tear of island life, Miranda wore feathers in her hair and a European-style suede corset. Prospero’s costume also amalgamated a romanticized version of his past and present lives; his European shirt and breeches appeared beneath an elaborate cape-coat, in the tradition of the ceremonial garb worn by a shaman.

Display large

image of Figure 2

Display large

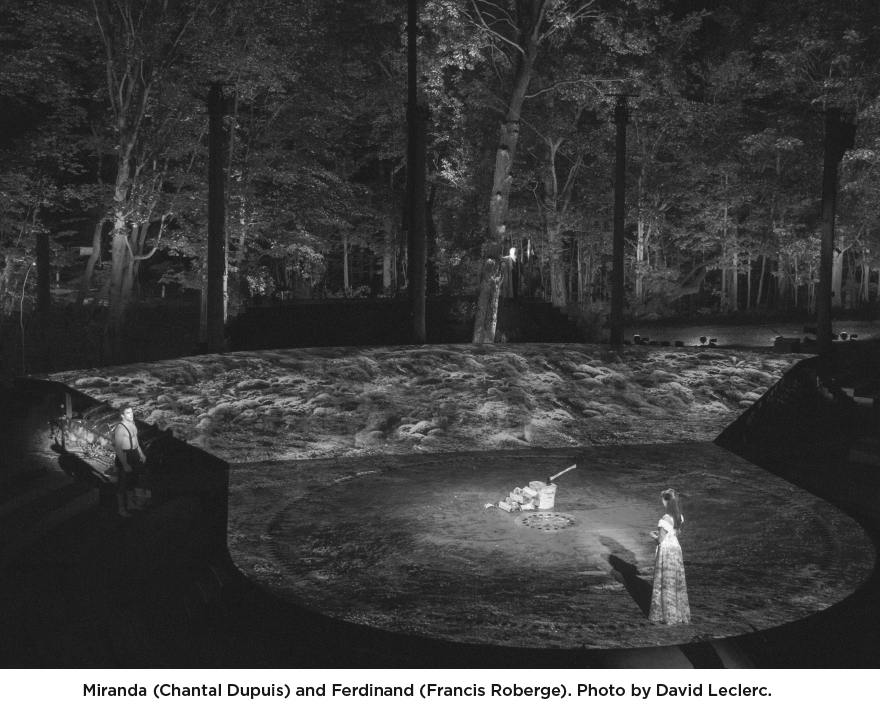

image of Figure 214 The theatre space and set also made significant contributions to La Tempête’s worldview. Responsible not only for directing La Tempête but for designing the set,17 Lepage brought Prospero’s island milieu to life via scenography that made the site central to the Wendake adaptation and honoured First Nations peoples’ connection with the land. A Greek-style open-air amphitheatre surrounded on three sides by audience members, the Wendake playing space opens onto the woods and backs the Saint Charles River. In the Wendake Tempête, as theatre critic J. Kelly Nestruck describes it:

Here, the production’s performance text intervened in the imperialist ideology of Shakespeare’s Tempest. Though Prospero may be the central player in Shakespeare’s text, La Tempête re-envisioned this hierarchy with the natural world occupying a vital position. Because the Wendake amphitheatre has no walls or ceiling, nature (whether embellished by light and sound or not) was the lynchpin in Lepage’s scenographic dramaturgy. In an email exchange, La Tempête’s assistant director Christian Garon commented:

In this, scenographic dramaturgy incorporates the always-already charged state of Indigenous land for its people. Since the forest figures as an important character in La Tempête (as detailed in the examples below), the production can be read as espousing the Huron-Wendat’s spiritual ideology, in which humans occupy a position in the great chain of relationships “that is no more and no less important than other lifeforms” (G. Sioui 114), among them plants, water, air, fire and earth. La Tempête’s natural aesthetic connects to the Huron-Wendat belief surrounding the importance of “consciously and frequently acknowledg[ing] these other peoples who, directly or indirectly, contribute to [. . .] subsistence, education, well-being, and happiness” (G. Sioui 28).

Display large

image of Figure 3

Display large

image of Figure 3Architectonic Scenography

15 Through ever-shifting projections, light, and sound, architectonic scenography contributed to La Tempête’s romanticized aesthetic while also establishing an underlying tension that complicated the production’s idyllic re-envisioning of New France. Covering the circular stage, various lush, kinetic projections appeared and functioned as extensions of the world created in Légaré’s paintings, among them a verdant meadow and a sandy beach complete with turquoise waves. These images were juxtaposed with aspects of the scenography underlining the realities of contemporary Wendake and the land’s colonial history. The gorgeous blue waves gently lapping at Miranda and Prospero’s feet during their first scene were thrown into high relief by the real sounds of the Saint Charles River. Running directly into the Saint Lawrence, this river was first mapped by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and its shores later became the site of New France’s first village. When aurally foregrounded by the real thing, La Tempête’s pristine water projections served as a reminder that prior to colonization and industrialization, the Saint Charles had yet to endure the extreme contamination that would lead to its long held twentieth-century status as Canada’s most polluted river (Quebec).18 A similar juxtaposition occurred in the cacophonous tempest scene as violent streaming rain was projected on the stage floor-cum-dark and brooding ocean, which ultimately caused the Europeans to wash ashore. Bathed in early evening light, the calm Wendake forest seemed to contain the furious storm scene like a sage, old witness, watching the moment of first contact unfold from a position entrenched in the last four hundred years of Wendake history.

Display large

image of Figure 4

Display large

image of Figure 4Embodied Texts

16 Also central to my reading of La Tempête is the marked shift made to the production’s blocking during the lead-up to opening night. At the invited dress on 1 July 2011, Caliban appeared empty-handed as Prospero addressed him during the play’s final monologue, a speech that is often directed to the house. For all but one of the preview performances and from opening night on, however, Caliban held Ferdinand’s axe—lowered, at his side—in this scene (Gottler).19 Through these two different stagings, the production offered striking revisions that centred on the silent moments following the play’s epilogue, spoken by Prospero.

17 The first interpretation saw Prospero waiting for a reaction after speaking the text to Caliban as an apology. The stage was otherwise empty and still, featuring no sound and low lighting. The lights went to black as the men continued to stare silently at one another in what could read as mutual acknowledgement. Support for this reading can be found in Lepage’s comment: “Encounters take place in La Tempête itself, a play that will bring these human exchanges to the stage in a rich and symbolic way” (qtd. in Isabelle). Moreover, given the production’s central historical-spatial mapping, beginning with Samuel de Champlain’s conquest in 1608, this concluding moment summoned the period following Britain’s acquisition of New France wherein the descendants of French colonials and Aboriginals found their “charms all o’erthrown” (5.1.1); they had been reduced to minority status by the British, who were eager to eradicate French and First Nations culture from Britain’s newest colony. Unlike Shakespeare’s conclusion, the Wendake Tempête saw Prospero remaining on the island, facing his own subjugation at the next colonizer’s hands. In this, Caliban and Prospero were aligned, a potentially insensitive proposition given that First Nations people were initially colonized by New France. As represented in the Wendake production, however, this final moment saw a marked shift in The Tempest’s extant power structures. The blocking put the men on equal planes and equal terms both literally and metaphorically. How Prospero and Caliban move forward and if they do so together was left as a question for the audience to grapple with.

18 The axe-less staging of the final moment between Prospero and Caliban also had contemporary significance, reverberating in Quebec’s real time setting of 2011—the men simultaneously faced each other as well as the uncertain future ahead. The spring and summer of 2011 saw marked upheaval for Quebecois and Aboriginal nationalists, including the Bloc Québécois’s loss of official party status and the collapse of various bills, including the Kelowna Accord, dedicated to improving the standard of living for Aboriginals. This evocative staging of mutual acknowledgment between Prospero and Caliban, therefore, resonated through the present as well as the past;20 Canada’s two longest standing, sovereignty-seeking federal minorities were yet again encountering individual challenges to their self-determinism. As depicted by La Tempête’s bodies in motion, the production seemed to promise that they could face these challenges together.

19 The second staging of the play’s conclusion, which would be retained for the production’s run, featured Prospero speaking the epilogue to Caliban as an apology; however, in this version, Caliban was carrying Ferdinand’s axe. As recounted by J. Kelly Nestruck:

Caliban was not poised and ready to strike Prospero in this moment, which would amount to a re-inscription of the violent savage stereotype, but instead, he held the axe in a lowered position. As noted by Barry Freeman, the presence of Caliban’s axe attempts to “interrupt a reading of the play as purely imperialist” by drawing attention to Prospero’s oppression of Caliban through this “unexpected moment of political and moral judgment [with] the audience cast as jury” (7). Here Prospero was the French and English colonizer writ large, representing colonialism’s devastating legacy, including the loss of First Nations land, the decimation of Aboriginal populations caused by war and European diseases, the abuse endured in residential schools, and the consequent cycle of alcoholism and mistreatment faced by many Indigenous Canadians today.

20 In light of this history and the substandard conditions faced on contemporary reserves, La Tempête’s second conclusion served to remind non-Indigenous spectators of the very real potential for a First Nations uprising—a concluding image that was simultaneously prescient and problematic. Considering Canada’s subsequent nation-wide Idle No More and Sovereignty Summer movements, both of which are protests advocating for Indigenous sovereignty in response to poor living conditions, racial intolerance and a lack of agency over ancestral lands, this ending would prove more fact than fiction in the months and years following the Wendake Tempête. As Caliban pondered First Nations retribution or reconciliation with axe in hand, (a moment championed by Poulin when it was first incorporated into the production [Gottler]), La Tempête’s performance text highlighted the plight of Indigenous Canadians as its concluding image. Though I cannot speak directly to Lepage’s reasons for re-blocking the conclusion, his choice to opt for a final image that emphasized Caliban’s right to retribution without drawing parallels with the struggles of the Quebecois demonstrates that the production’s primary focus was centred on the repercussions of colonization for First Nations peoples, not the Quebecois. Of course, by crafting such a final image, Lepage and Ex Machina ran the risk of appearing to speak for First Nations people and, despite Poulin’s enthusiasm over a conclusion that empowered Caliban, it is unclear if the final scene’s blocking was discussed with other collaborators beyond Poulin.

21 Above and beyond the interventions created by physical texts in La Tempête’s dual conclusions, embodied practices also acted as agents of cultural decolonization in the production. This further demonstrates that resistance is not exclusively crafted through the dramatic text but is also legible through “the performer’s body as a cultural and artistic text” (Balme 167). The production’s treatment of the masque scene, in which Prospero consents to Ferdinand and Miranda’s marriage and instructs Ariel to arrange a celebratory dance, offers a clear example of embodied imperial resistance. As employed in Shakespeare’s text, the masque is an assertion of Prospero’s power. He fears that Miranda will lose her virginity before the marriage ceremony is performed, warning Ferdinand that if this is the case “barren hate/Sour-eyed disdain and discord shall bestrew/The union of your bed with weeds so loathly/That you shall hate it both” (4.1.20-23). In light of Prospero’s emphatic warning, the masque functions not only as an assertion of his control over his daughter’s sexuality but as a moment in which he uses his magic to subdue any carnal rumblings felt by Ferdinand and his bride to be. Of the spirits gathered for the performance, Venus and Cupid are conspicuously absent, and, consequently, so are the dynamics of passion and desire that they represent (Magnusson 64). When Ferdinand and Miranda are finally left alone, waiting to be reunited with the other Europeans, they fail to capitalize on a rare opportunity for intimacy and, instead, settle on a decidedly unsexy game of chess (64).

22 In contrast to Shakespeare’s narrative, the Ex Machina/Huron-Wendat staging of the masque was imbued with a dangerous sexuality that Prospero could not control. Sent off to gather the “rabble” (4.1.37), Ariel returned with the Sandokwa Dance Troupe, the aforementioned Wendake group who perform their own choreography. The dance performed by the Sandowka troupe features two male performers bedecked with deer antlers, battling one another in an evocative and dangerous mating ritual. Given Prospero’s assumed control of his daughter’s sexuality and Lepage’s decision with the dance troupe to present one deer dancer as older than the other (via a slightly more limited range of movement), this conceit read as a metaphor for Prospero’s conflict with Ferdinand, who represents an impending threat to Miranda’s virginity. As the male dancers circled each other in a tension-building, opponent-assessing ritual, the female dancers formed a circle around them. Prospero, Ferdinand and Miranda were excluded from the circle, reinforcing their lack of agency and emphasizing the fact that control resides with the First Nations spirit world. After the circling had built significant tension on stage and in the audience, the deer dancers charged simultaneously, locking antlers in a climatic moment highlighted by the defeated performer’s piercing cry. Considering the charged sexuality of the dance and Prospero’s fear for his daughter, this painful exclamation foreshadowed the piercing of the “virgin-knot” (4.1.15) and Prospero’s loss of control over Miranda. This scene represented a reconfiguration of power as Ariel not only subverted Prospero’s wishes by titillating the young couple but forced Prospero to confront his ultimate powerlessness over his daughter’s virginity.

23 Of course, in staging the wedding masque with First Nations performers, La Tempêterisked playing into reductive and exoticized notions of Aboriginal others. In examining the implications of the masque as performed by the Jagera Jarjum Aboriginal Dance Group in the Queensland Theatre Company’s 1999 production of The Tempest, Elizabeth Schafer notes:

This same critique cannot be leveled at La Tempête’s use of the Sandokwa dancers. Positioned within Lepage’s scenographic dramaturgy as physically and culturally authoritative figures, the First Nations performers in this production reinforced Aboriginal power. As described above, the deer dance featured in the Wendake production’s masque was by no means a tedious, decorative moment; instead, this physical battle was charged with danger and sexuality, controlled entirely by Ariel and the Sandokwa dancers, not Prospero. In fact, the Sandokwa dancers offered a significant counterpoint to the production’s otherwise highly glossed, picturesque aesthetic. In scenes where they appeared alongside the bright and ornately dressed court characters, the Sandokwa dancers undercut the fantasy. Dressed in realistic, seventeenth-century Aboriginal costumes, marked by simple shapes and subtle beige tones, the dancers’ arrival and performance of traditional Huron-Wendat songs created a tension highlighting the fact that the fairytale world inspired by Légaré’s romanticized vision of New France was just that, a fantasy.

Display large

image of Figure 5

Display large

image of Figure 524 The agency of First Nations characters and the anxiety they incite among the Europeans also features in the Wendake production’s rendering of the Act 3, Scene 2, banquet scene. As described by Freeman, Ariel’s appearance, marked by her thundering, mediated voice and the stage’s flash of crimson, was arresting:

Again, scenographic dramaturgy demonstrated the agency and strength of First Nations characters in this production. Here Ariel claimed justifiable revenge on the Europeans, who, much like the hellish guests in Baumander’s Tempest, were having an uproarious time appropriating a First Nations celebratory feast. As in La Tempête’s second concluding scene featuring an axe-wielding Caliban, Quebecois, Anglo-Canadian and First Nations spectators were confronted with Canada’s problematic colonial history and the suggestion of warranted retribution by First Nations people.

Imperial Resistance through Body Texts

25 The highly physical performance texts featured in La Tempête also come to figure in two broader discussions. Because my definition of scenographic dramaturgy hinges on the visual and aural score crafted by performing bodies in action, as considered here, scenography is always-already political in its use of physical bodies, particularly when Indigenous performers are involved. Does La Tempête’s scenographic dramaturgy adhere to the Western theatrical tradition that has “relegated or restricted indigenous [. . .] performers to the realm of folklore” (Balme 168)? In this section, I argue that scenographic dramaturgy resists this tradition in that performers worked with Lepage to create physical texts defined by their respective strengths and ideas. These physical performance texts also speak to the often-contentious landscape of acting Shakespeare in Canada. Canadian Shakespeare training assumes indoctrination in formal Eurocentric acting traditions and body cultures.21 Much like in opera, this tradition privileges the voice over all else and, though the actor’s physicality remains important to characterization, any movement that compromises the voice or text will not survive beyond the rehearsal hall. Denis Salter problematizes the limits of such “natural acting” as defined by British training legacies, when he writes:

Given that “natural” acting is privileged at Canada’s Stratford Festival, the largest classical repertory theatre in North America, this style is therefore seen by many Canadian artists as the gold standard of acting aesthetics, limiting opportunities for actors performing outside this aesthetic paradigm nation-wide. In the case of his Wendake Tempête, Lepage resisted the hegemony of a British model meant to keep distinctly postcolonial performances off the stage and, instead, welcomed what might be considered “unnatural” acting by working with Indigenous performers to craft embodied texts that decolonize the stage.22

Display large

image of Figure 6

Display large

image of Figure 626 Among Ex Machina’s collaborators for La Tempête were the seven First Nations dancers in the Sandokwa troupe, including Steeve Gros-Louis who also played Alphonse; the axe-juggling acrobat, Francis Roberge as Ferdinand who literally split an offstage tree in two by throwing his axe from centre stage; and circus acrobat Jean-François Faber as Trinculo, known in Garneau’s translation as Étranglé. Roberge and Gros-Louis were tentative with the text, both unintentionally slipping into monotone deliveries at points; nonetheless, these performers’ unique physical talents became the primary mode of communication as embodied sequences from their own work, whether with the Sandokwa Dance Troupe (Gros-Louis) or The Lumberjack Acrobats, a company consisting of Roberge and Faber (Faber), were incorporated into the production. For his part, Faber also struggled with aspects of the humour in Étranglé’s spoken text but the liveliness of his kinetic performance text, which featured increasingly difficult gymnastic feats including back flips, high-speed tree-scaling, and barrel-rolling, became essential to Wendake’s visually-driven re-“writing” of La Tempête. A Wendat performer trained at École Cirque in Quebec, Faber had experience incorporating his specific physical strengths into productions, having been directly recruited by Cirque du Soleil to bring his self-styled acrobatics and cube juggling routine into Les Chemins invisibles and Wintruk (Nadeau). Many of the stunts and pratfalls performed by Faber in La Tempête can be seen in an online video of his work with The Lumberjack Acrobats (Faber). A collaboration that clearly suited both artists involved, La Tempête led Lepage to hire Faber as an acrobatic consultant for his 2013 remount of Needles & Opium with the Toronto theatre company, Canadian Stage. In this way, even after La Tempête had closed, Lepage’s efforts to recolonize the stage continued, productively manifesting themselves in an anglophone Canadian theatre.

27 When La Tempête’s physically adept performers united to embody scenes featuring pronounced performance texts, they joined their director in collectively talking back to Eurocentric performance models that privilege dramatic text at the expense of embodied performance. This was exemplified at the outset of La Tempête. As the production began, many of the performers descended from above the stage, harnessed and relying on their acrobatic training to violently embody the storm scene as they thrashed through the air. In this frantic, thundering scene consisting of competing cries of “yare!” and “down with the topmast” (1.1.34), Lepage and the performers overwrote Shakespeare’s authorship and subverted what Salter might call the “natural” Eurocentric tradition of over-enunciating dialogue. As the performers’ bodies crashed through the air and they cried out, physical performance text took a more essential position than Shakespeare’s dramatic text while the scene’s central event and meaning remained intact. By refusing to adhere to established Western codes surrounding what it means to “act Shakespeare” and, instead, opening the production to a variety of physical performance vocabularies that de-privilege Shakespeare’s written text, La Tempête offered embodied forms of intervention.

28 The Tempest’s inherent imperialism was further undercut by the decision to make Caliban’s body a site of resistance. Played by Métis actor Marco Poulin, Caliban was at no point the “puppy-headed monster” (2.2.154-155) described by the inebriated Étranglé and Stéphano. Instead, Poulin’s Caliban was a powerful, physically assuming presence. Throughout the Wendake production, Poulin literally carried twenty-five feet of chain on his compact muscular figure, largely unconstrained by its weight. Clamoring against the stage wherever he wandered, Caliban’s shackles served as an aural reminder of the physical power at his disposal. Moreover, in the drinking scenes with Étranglé and Stéphano, Poulin’s Caliban was at no point the compliant servant; instead, even when kissing feet, he maintained his dignity through strong, upright posture. Unlike Étranglé and Stéphano’s drunkenness, Caliban’s inebriation served to heighten his anger, making the threat of his plotting against Prospero real. This rendering of Caliban subverted the noble and ignoble savage stereotypes. Nestruck describes Poulin’s characterization as “no noble savage cliché” and, despite Freeman’s overall reading of the production as essentializing, he concedes that at times Poulin’s Caliban strikes “a lucid determined figure” (5). This Caliban does not approach the Europeans’ offer of alcohol with initial awe and trepidation. He is self-possessed, shrewd and always keenly planning the re-appropriation of his land from Prospero. In this, La Tempête demonstrated resistance to reductive portrayals of Indigenous culture, crafting a powerful, show-stealing Caliban.

29 La Tempête’s intercultural considerations extended not only to characterizations but also to the performance modes and performing bodies incorporated into the production. At first glance, the casting of local Huron-Wendat dancers as the fairies/spirits could be viewed as tokenistic or as an aesthetics-driven attempt to present “traditional” performance forms; nonetheless, further research demonstrates that there is a culturally layered history behind the Sandokwa performances. Of the folkloric dances presented by the Sandokwa troupe founded in 1976 (Gros-Louis), Wendat historian, anthropologist and curator, Louis-Karl Picard-Sioui comments:

Because the dances are an appropriation of a Western form reconfigured since the mid-twentieth century by Huron-Wendat people, their inclusion in the Wendake Tempête demonstrated a willingness to dispense with discourses of authenticity and include hybridized Indigenous performance modes. Authenticating discourses were further subverted through casting choices including Lepage’s decision to have Huron performers Steeve Gros-Louis and Jean-François Faber play Shakespeare’s shipwrecked Europeans. Kathia Rock’s performance also contributed to the production’s non-essentializing interculturalism; she is a Maliotenam-born, Innu singer-songwriter, playing Ariel as a Huron and performing her own Innu translations of Michel Garneau’s previously “tradapted” Shakespeare songs. Collectively, the hybridity of La Tempête’s performers and performances demonstrates the “rhizomatic potential of interculturalism [. . .] to create representations that are unbounded and open, and potentially resistant to imperialist forms of closure” (Lo and Gilbert 47).23

30 Forms of closure did, however, play out in the assembly of La Tempête’s design team, which was exclusively composed of people of European descent.24 Because the production’s distinctive scenographic dramaturgy took centre stage in the adaptation and focused largely on representing Wendake’s people, land and culture, Lepage and his company ran the risk of appearing to speak for the Huron-Wendat, not with them. An official collaborative platform was not in place for La Tempête, making Lepage and his team (unsurprisingly) the dominant force in the equation. Ex Machina’s production practices in Wendake, however, reflect a step towards empowering its collaborators and lessening power imbalances. Referring to both her “bible” (a binder containing all costume and hair designs, a scene breakdown, and a quick change plot), and Ex Machina’s show “bible” (a binder including La Tempête’s script, scene breakdown, blocking, props, set placement, and all lighting and sounds cues) costume designer Mara Gottler comments:

Essentially, Steeve Gros-Louis and the Sandokwa dancers had access and an invitation to give feedback on the complete score plotting out La Tempête’s scenographic dramaturgy. By making show bibles available, Lepage and his team demonstrated an awareness of the importance of their collaborators’ comfort levels and an openness to negotiating any shifts deemed necessary by Steeve Gros-Louis and/or the Sandokwa dancers. Reflecting a greater movement in contemporary theatre, which is fed by the growing understanding that “dispersed power is not necessarily democratic power” (Harvie 4), Ex Machina and Lepage experimented with the negotiation of control within a director-led model.

31 With its early contact-themed setting and casting of First Nations performers as Ariel, Caliban, and the fairies, La Tempête could initially be read as a return to a well-worn post-colonial interpretation of the play. Yet, as re-“written” by scenographic dramaturgy, the production demonstrated a significant shift from Ex Machina’s previously essentialist portrayals of others. By engaging with the Huron-Wendat community for a site-specific production in Wendake, empowering Aboriginal bodies in performance, and shifting The Tempest’s conclusion to give a First Nations Caliban agency over Prospero, Ex Machina offered a progressive treatment of a federal minority group outside the white, francophone Quebecois. Beyond the material signs of this new politics on stage, a closer look at the company’s off-stage approach to crafting the production’s scenographic dramaturgy further demonstrates an effort to facilitate intercultural exchange—be it the availability of show “bibles” to members of the cast and/or the invitation to collaborators to give feedback. Moreover, La Tempête had a significant impact on Wendake’s previously underperforming tourist economy with what vendors called the “Lepage effect,” which brought a “financial windfall” to the community thanks to the director’s international reputation (“L’effet”). Though by no means a collaboration where both parties had equal artistic control, the Wendake Tempête avoided authenticating discourses, integrated hybrid performance modes, and provided its Huron-Wendat collaborators with access to all aspects of the production, encouraging creative input. Chief Konrad Sioui, whose thwarted quest for reconciliation between First Nations peoples and the francophone Quebecois in 2009 introduced this essay, recently referred to Robert Lepage as a friend and neighbour of the Huron-Wendat community (Desloges). My question now is whether this meeting of cultures will remain an isolated occurrence or will signal an increasingly progressive intercultural politics in the future work of Robert Lepage and Ex Machina.