Forums: Theatre? Research? In? Canada?

Contemporary Circus Research in Quebec:

Building and Negotiating and Emerging Interdisciplinary Field

1 Describing an emerging field of research, one that is fundamentally interdisciplinary and heuristic in its phenomenological approach, can be overwhelming. In one sense, everything has yet to be done, but to state even this would be to negate precursory forays into the study of contemporary circus as practiced in Quebec and disseminated throughout the world from an unexpected new circus capital. In this short essay, I give a first-hand account of the creation of the Montreal Working Group for Circus Research, its rapid growth and integration into Montreal’s vibrant cosmopolitan circus scene. The Working Group and its ongoing collaboration with National Circus School of Montreal have served as a nexus for developing research strategies and a vocabulary for the new field of contemporary circus studies in North America.

2 In thirty short years, circus—in its contemporary narrative-driven, animal-free form— has blossomed in Quebec to the extent that it has become a potent cultural and economic symbol of the successful marriage of creativity and entrepreneurship. Circus is both performing art and business, fundamentally global and multinational in its traditions and the provenance of its artists and, in the case of Quebec, very much presented as a distinctive hybrid model for creativity emerging from a distinct society.

3 The impact of Quebec circus on the Montreal economy is well over one billion dollars in direct revenue, not counting the trickle-down effect and impact on secondary and tertiary industries, which rely on circus activity locally and abroad. Cirque du Soleil’s annual gross revenues have been, alone, roughly one billion dollars, with over 85% coming from the US, through its touring shows, product sales, and—mostly—its eight permanent Las Vegas productions, with the remainder from its ten touring productions throughout the world. 11

4 Its administrative and creative headquarters are situated in Montreal, as are its costumes, properties, sets, and multimedia workshops, production and touring offices, and many of its creative partners such as Sid Lee Marketing (with whom Cirque has created the joint venture Sid Lee Entertainment), and Geodézik. Before the recent wave of job cuts (30 in Fall 2012, 400 in Winter 2013, and depending on sources, another couple hundred over the past year), 2 Quebec-based expenses accounted, before the recent wave of job cuts, for roughly 85% of its expenses on a one billion dollar operating budget. Cirque’s impact, locally, is phenomenal. The next category of Montreal-based circus companies, Cirque Éloize (in which Cirque du Soleil reportedly a 50% stake) and the independently-run 7 doigts de la main (known in the US as 7 Fingers) and their subsidiary companies reportedly have operating budgets of around 10-12 million dollars each. 3 Most of their revenue comes from international touring. Another forty smaller circus companies make up for roughly a million dollars of direct economic activity. I’m not including the five circus for social change organizations, the National Circus School of Montreal (the only government-funded elite-level school in North America), the twenty “feeder schools” and studios, Montréal Complètement Cirque, Montreal’s annual international circus festival, or la TOHU, North America’s only permanent theatre- in-the round devoted to contemporary circus which offers a complete subscription season. Quebec schools now regularly offer circus activities as par of their physical education curriculum or as part of extra-curricular activities. Finally, the province of Quebec, since 2001, has recognized circus as a legitimate art form and has ensured steady provincial funding for its more experimental productions through a program exclusively devoted to circus arts. 4 Contemporary circus with its combination of artistic activity and sports ethos has permeated Quebec society in ways that cannot be ignored by the academy.

5 Following Cirque du Soleil’s quick and phenomenal success worldwide, its spectacular success in the US and effective infiltration into American pop culture (Cirque presence twice at the Oscars, twice at the Super Bowl, and filtered through musical stars such as Madonna and Pink as they integrate circus in their acts), with the resulting economic consequences, the very term “cirque” has come to differentiate the high value artistic brand from the traditional family-oriented circus. Cirque has become a buzzword to the point where many American companies and circuses have sought to distinguish themselves from traditional circus—and perhaps share some of Soleil’s lexical magic—by integrating the French term into their names. 5

Planet Circus

6 French circus scholar Pascal Jacob, in a keynote address at “The State of Circus Research in Quebec” a workshop session held at Concordia, McGill, and the National Circus School in September 2012, spoke of Quebec’s place in the circus nations. He felt that there had been six ‘circus eras,’ which could be associated with countries. England, with its equestrian and military culture reintroduced the circus in its modern form (1768-1830); while France had its first heyday in refining equestrian acrobatics and introducing the clown (1830-80). The following period (1880-1930) was polarized between Germany with its introduction of exotic animals and extreme acrobatics and the United States, with its freak shows and dime museums, and especially its three-ringed extravaganzas. The Soviet-Union (1930-1980) introduced elite training and focused on artistic expression; France pursued this artistic project and sought to give social significance to circus from the 1970s to the 2000s with its nouveau cirque. Now Quebec, on the coat-tails of Cirque du Soleil’s globalized success and 7 doigts de la main’s circus of individualized ethos has become the Western circus nation to emulate or to react against.

7 Quebec’s brand of theatrical, mostly animal-free contemporary circus 6 born out of French nouveau cirque, Soviet-inspired elite acrobatic training, and American entrepreneurship and showmanship, has emerged from a burgeoning nation preoccupied with its own singularity and distinctiveness. Paradoxically, however, its circus sometimes comes across as blandly “global” and audiences find themselves before assumed cultural neutrality or, as Karen Fricker put it, a “purposeful cultural blankness” (“Cultural” 130).

8 In spite of this domination of the circus world—and perhaps because of the triumphalist recuperation by the local media and the State (see Harvie and Hurley; Lavoie; Leroux “Le Québec” and “Cirque in Space!”; Hurley)—scholarship on circus in Quebec has been slow to develop, save for a smattering of articles and a handful of theses and dissertations—usually descriptive appreciations of the world-beat aesthetic and ‘reinvention’ of circus by Cirque du Soleil—, and written very much from a safe distance from the scene they were describing. A few pioneering exceptions include Julie Boudreault’s MA and PhD theses (1996 and 1999) as well as Isabelle Mahy’s PhD dissertation and later book (2008) in the sense that their authors did research from within the structures they were investigating. Recently, however, a gradual legitimizing of circus research with the creation of a research centre and the funding of an Industrial Research Chair at National Circus School of Montreal, a few scholarly issues devoted to contemporary circus in Quebec in L’Annuaire théâtral (2002 and 2009), Spirale (2009), and, forthcoming, in Québec Studies (2014), in addition to an incremental understanding by circus companies and artists of the nature, limits, and advantages of research on their own practices has recently allowed for more extensive experiential research allowing students and researchers new access to their objects of study.

9 Theatre and dance have traditionally allowed student observers without incident, yet circus had resisted academic scrutiny for cultural and economic reasons. Circus culture has traditionally relied on hard-earned apprenticeship and oral transmission of its trade secrets. What has tended to distinguish (and to find position for marketability) one artist over another isn’t general aptitude, but rather the specificity of their trade—their ‘trick,’ very rarely described or broken down to outsiders. Add to this the very secretive nature of a highly successful commercial environment known for poaching audience-drawing acts and you have the makings of a rather protective milieu, bent on developing its own research and development capabilities, independent of academic outsiders. For years, researchers came through with their preconceptions, gathering data, occasionally misreading signs, and pursued their route elsewhere, to work on other topics. Only recently has the contemporary circus world in Quebec produced emerging scholars who have an intimate knowledge of that world's training, practices, and culture and who also possess the analytical tools and broader understanding of research needs and practices. 7

10

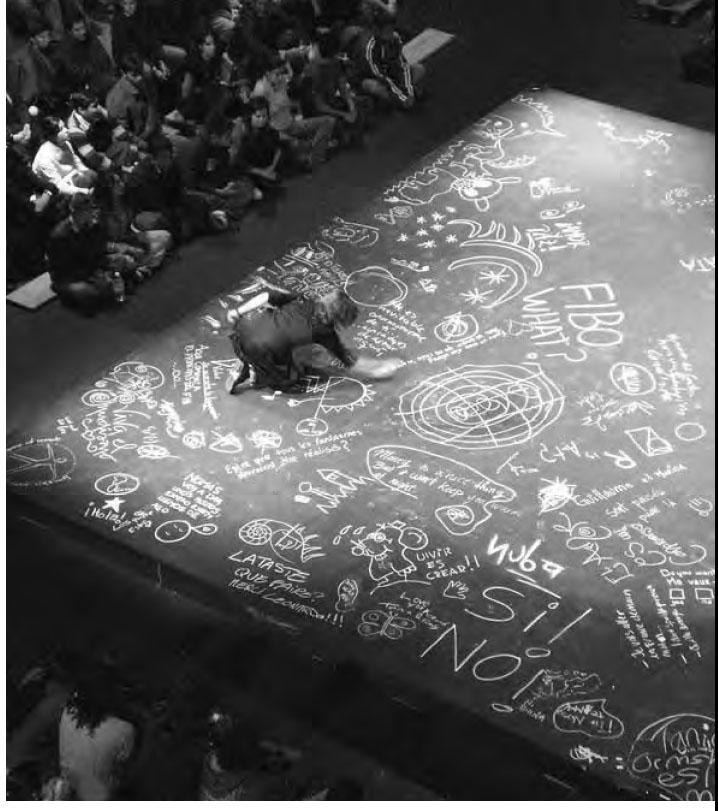

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 When I first started working on circus, I had to address concerns about my goals as a researcher. Before anyone talked, before I was allowed ‘in,’ they needed to know whether I was coming in as a tourist or making a long-term commitment. Though concerned with objectivity and appropriate scholarly distance, I quickly understood that I had to truly engage with the milieu, to be present. But to offer an honest non-complacent reading of it, I first needed to experience it up close, through on-going discussion, through panel-discussions, open forums involving practitioners, scholars, and policy-makers on topics that were of vital interest to the community and, interestingly, which hadn’t yet fully appeared in scholars’ areas of inquiry. These topics included “contractual ethics” (Achard et al.,), “international recruitment of Chinese Artists at Cirque du Soleil” (Zhang), “managing pain in training and in performance” (Leclerc, Holmes, and Aubertin), “archiving circus production” (Barlati and Zummo), “circus as community-building” (Wall). Only then was I able to gain the practitioners’ respect and confidence and draw them into a discussion of scholarly concerns. A number research projects have bridged academic pursuits, pedagogical concerns, and circus’ growing interest in understanding its own processes and impact. These include in-depth exploration of decision training in a high performance setting (Lavoie, Burtt, and Aubertin), “evaluating the socio-cultural impact of social circus” (Spiegel “Singular” and “Evaluating”), “physical literacy and high performance training” (Kriellaars), “thinking and writing about contemporary circus” (Fricker et al.), “creativity and urban regeneration” (Rantisi and Leslie), the “political body—embodied protest in contemporary circus” (Lavers, “Political” and “Animals”), to name but a few recent talks at Montreal’s Working Group on Circus Research. My own research into circus dramaturgy (2013), which combines a study of the vocabulary of circus disciplines with the aesthetic choices made through the narrativisation of contemporary productions, emerges from ongoing concerns with non-verbal theatrical dramaturgy but connects with the National Circus School’s preoccupation with developing a coherent vocabulary and eventual program in circus directing and its ongoing commitment to pursue research into new interactive and immersive technologies in the circus arts.

Montreal Working Group on Circus Research

12 The Working Group began in 2010 as an informal gathering of academics interested in the aesthetics, economics, and ethics of Cirque du Soleil as both a force in renewing circus arts in Quebec and as a major cultural force promoting Quebecois creativity and commercial innovation. Erin Hurley, Karen Fricker, and I, after having worked on a special issue on “Le Québec à Las Vegas” for the scholarly journal L’Annuaire théâtral (2009), combined forces with economic geographers Norma Rantisi and Deborah Leslie who were already engaged in Cirque-related research. We soon invited colleagues such as Patrice Aubertin and Anna- Karyna Barlati from the National Circus School to participate in the ongoing discussion and it was the most important decision we would make. The first year’s activities focused around a model of seminar presentations of ongoing research where colleagues openly discussed issues, challenges, and outcomes.

13 By the end of the first year, and into the second year, the Working Group began to widen its scope onto circus practices in Quebec and abroad. Both Concordia University and National Circus School, through the Working Group, formed a research partnership with three objectives: 1) developing specialized knowledge retention in circus arts training and practice for performers and pedagogues; 2) disseminating of circus-related knowledge through academic and industry channels; 3) widening the scope and encouraging dynamic academic approaches to studying the circus arts (through research-creation, experiential practices, economic geography, sociology, and other complementary disciplines).

14 To fulfill these objectives, the Working Group initially focused on three thematic axes that correspond to its ongoing work and anticipated fields of investigation: 1) circus pedagogy; 2) historical traditions and current stakes of circus practices, including discourse, aesthetics, ethics, and economics; 3) circus dramaturgy, including a series of hands-on experiential explorations between academics and circus artists.

15 From five or six scholars sharing emerging research at ad hoc meetings at Concordia University to an active list of over one hundred scholars, students, practitioners, pedagogues, and industry players, the Working Group has grown into something of an essential hub for critical thinking on contemporary circus and cultural discourse, branding, and issues of training and pedagogy in both high performance programs and applied creativity. Our meetings, held at Concordia University, the National Circus School of Montreal, and occasionally at McGill, now regularly attract between twenty and forty people every six to eight weeks. These meetings and the research emerging from them have also prompted invitations to American universities and by American circus community, Circus Now, to share our insights and research methods.

An emerging field in an interdisciplinary research landscape

16 The ad hoc discussion group has grown very quickly, and unexpectedly, into a community of scholars and practitioners building a field that departs from theatre and performance studies, as well as existing American studies into circus history or European heuristic studies of nouveau and contemporary circus. This new field, North American contemporary circus studies, is arising from the initial impetus of studying and understanding the contemporary circus emerging from Quebec, a hybrid form of European circus aesthetic and ethos and American commercial and industrial creativity and practices. In parallel to the Working Group’s emergence from sideshow to partner, the National Circus School in Montreal has structured its own research activities under a new research centre, establishing university and industry collaborations. It has applied for, and obtained, a five-year SSHRC-managed (but NSRC-funded) Canada Industrial Research Chair for Colleges in Circus Arts. 8

17 The National Circus School has been involved in training much of the talent hired by the most selective circuses worldwide. It has a high performance program at the high school level, the collegial level, as well as a professional program that includes instructor and circus trainer programs. Just over half of its students are from Quebec, while, depending on years, 10-15% are from the US, 10-15% from France, 10-15% from other Canadian provinces, and there is a consistent representation of the world’s nations, from Australia to Germany, Norway to Chile, Russia to Palestine. In 2012-13, there were 184 students enrolled in six programs. 9 Needless to say, the principal focus at the school has been circus training, pedagogy and promoting its students through its high-value end of year productions at la TOHU.

18 The arrival of the Industrial Chair in Circus Arts in 2012-13 and the School’s growing and active interest in research and innovation has opened up circus culture to formalized research and has encouraged that very community to ask for agency over the research. The funding structure of the Chair, part governmental, part industry-driven, has allowed for a rapprochement between the school, the Montreal-based partner industries (Cirque du Soleil, Cirque Éloize, 7 doigts de la main, and Geodézik) and university researchers. In-depth, experiential research that hadn’t been possible a few years ago is slowly developing to everyone’s advantage. For instance, I was able to work on circus dramaturgy and technological integration in circus over the past year by assisting director Samuel Tétreault on a number of focused week-long workshops with circus performers from the National Circus School and 7 doigts de la main, and an extensive design and tech team from Geodézik. He may have initially resisted the scholar’s observational stance, as did the circus artists and technicians, but from the moment I began actively directing, writing scenes, bringing research and exercises for them to engage with—in other words, from the moment I was actively involved in experiential research and learning alongside the circus artists—I ceased to become an “expert” in order to truly understand what was before me. Circus imposes a keen sense of physicality, an overcoming of physical limits and obstacles. Observation is not sufficient; one has to accept the fundamental risk of failure and ridicule.

19 Circus research requires interdisciplinarity in a way that I haven’t seen in theatre or dance research, at least not in an ongoing open discussion between researchers in such a variety of disciplines and theoretical frameworks. One can always anchor research within the disciplinary confines of a particular analysis or reading, but Quebec circus—as a global phenomenon, as a billion-dollar industry, as emblematic representation of national know- how and innovation—remains steeped in many converging fields: aesthetics, dramaturgy and creative process, cultural politics, discourse of nationhood and paradiplomacy, circus training and pedagogy (from high performance training to physical literacy), ethics, philanthropy, social circus, engineering (massive structures, complex rigging), sports medicine (epistemiology), branding and commerce, urbanism and social spaces, and hand’s-on research and development stemming from individual companies and through the newly-developed research and pedagogy nexus at the National Circus School.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 220 Looking ahead, the Working Group and other circus researchers face a number of challenges. These include a concern for: 1) time and resources for extensive immersive research allowing a multidirectional flow of knowledge (knowledge which can be both published in peer-reviewed journals and made useful, in concrete terms, for the studied milieu); 2) building a sense of legitimacy from colleagues in disciplinary fields baffled by the study of circus, but also maintaining an interdisciplinary spirit or collaboration; 3) working towards a clearly defined inter-institutional research center through which funnel and make available to other researchers and students the incredible amount of research emerging from our individual and collective projects. 10 The scope of the field is so large that it cannot be contained by a single Chair, a single institution, or a single working group, for that matter. We’ll need to start thinking in terms of a multiplication of relatively specialized research poles and methods that can nevertheless share research, resources, and a commitment to a growing and complex field. Finally, 4) negotiating the complexities associated the challenge of doing research within a multi-layered commercial, artistic, and pedagogical context brings a fascinating convergence of ethics issues and non-disclosure agreements, all of which underline the materiality and significance of the process and its understanding.

21 A portrait of current research into Quebec circus must be more than a list of research projects, papers, and publications. 11 It must be the ongoing tale of an emerging field, pulled in every direction by disciplinary and professional concerns, yet brought together by a fundamental engagement in the interdisciplinary nature of a commercially-successful performing art, which resonates deeply with Quebec’s aspirations and its ever-present sense of its own becoming. To date, the Group’s work has touched upon aesthetics, criticism, and dramaturgy; invested practice and pedagogy; examined economy, commerce, and branding; explored ethics, social circus, and community-building; and contributed to the first “contemporary circus reader” in English, Cirque Global: the Expanding Boundaries of Québec Circus (edited by Charles Batson and myself, currently under peer-review with an academic press). 12 Now members from the Working Group have decided to tackle the little-known history of Quebec circus, from its first touring productions of Rickett’s travelling circus in the late 1790s to its unexpected place, today, amongst the circus nations of the world. Reflecting the current circus scene’s resistance to antiquated models of nostalgic faded-glory circuses of yore, we initially sought to look forward at emerging trends. But we all know that circus wasn’t suddenly “reinvented” in 1984 by stilt-walkers and fire-throwers from Baie-St-Paul to quickly become a global phenomenon. Its roots are multiple and complex and they burrow through many terroirs and little-told histories: those of street theatre, clowning, acrobatics, gymnastics, strong-men, burlesque, pantomime, North American touring networks, assumed exoticism, cultural avatarism, and social mobility. Perhaps by recognizing these complex origins and understanding its long-standing relationship with these international scenes and practices, Quebec circus will be able to imagine its way out of a potentially destructive contentedness in having reinvented an art form that will invariably morph into something new and different within a generation.