Forums: Theatre? Research? In? Canada?

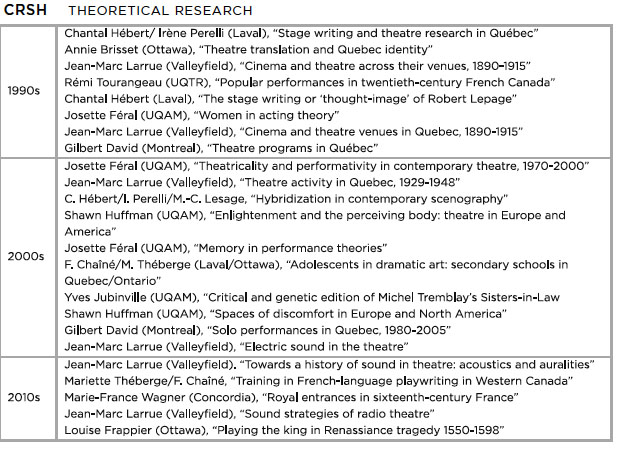

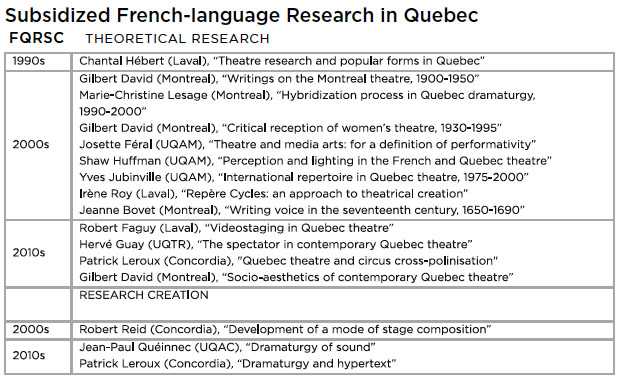

Chart of Subsidized French-Language Theatre Research in Quebec Since 1990

1 It is impossible to provide a credible overview of French-language theatre research in Quebec during the last few years. However, this did not prevent my colleague Patrick Leroux and me from organizing a session on the subject at the conference of the Canadian Association for Theatre Research in Victoria in June 2013 and bringing together researchers to profile current Quebec research in the stage arts. Although there are researchers who work in English and in French, those who write or publish in both languages are few and far between. Our initiative was an attempt to overcome this language barrier. Our first objective was to provide information on the Quebec research network and the areas of research driven by francophone researchers since 1990; the second was to improve the existing—and inadequate—exchanges between francophone and anglophone universities. As president of the Quebec Society of Theatre Studies, the francophone equivalent of the Canadian Association for Theatre Research, I felt it my duty to reach out and inform you of what’s being done in Quebec, a sign, moreover, of our interest in learning about similar activity elsewhere in Canada. 1

2 The following paragraphs discuss the main fields of research subsidized since 1990. The focus is on research in French only, as this is generally less accessible to those with no knowledge of the language. Clearly, excellent research is being done in English and other languages in Quebec; such work, however, is not covered in this brief survey, which also omits to mention unsubsidized work and research conducted outside the university context. Likewise, student dissertations and theses are not discussed for reasons of space. That will be for another time.

3 This text is followed by a chart of the major French-language research subsidized since 1990 by the Fonds de la recherche du Québec sur la société et la culture (FQRSC) (Quebec Fund for Research on Society and Culture) and by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). 2 The chart is not exhaustive and focuses on work mainly relating to theatre. Owing to space constraints, I did not always record the official titles of the projects, but summarized them at times for the purposes of this inquiry. I apologize in advance for any oversights and errors I may have made in listing and outlining the projects. In light of these data, I will attempt to briefly describe today’s main research trends.

4 Eight Quebec researchers were subsidized during the 1990s, a single one of them by both levels of government. All projects except one dealt with the Quebec theatre, either past or present. 3 In the 2000s, eight subsidized researchers joined the list. Most new researchers entered via the FQRSC, with the exception of two persons who had first been funded by SSHRC. Slightly over one-third of the work did not deal with Quebec theatre in particular. Certain researchers, in fact, focused on the Quebec corpus only in part. In the 2010s, six other francophone researchers, including two in research-creation, were added. During this period, half of the researchers were working on a Quebec corpus exclusively. Broadly speaking, the three most heavily studied areas were hybridization of forms, theatre history, and research-creation.

5 The documents I obtained from the subsidizing authorities allow for a brief summary of the approaches privileged by francophone researchers. In the 1990s, a tension between popular forms and experimental theatre and by the interpenetration of forms dominated research on Quebec theatre. Those focused on said issues included Jean-Marc Larrue, who examined the links between cinema and theatre in the early twentieth century; Chantal Hébert, who began research on Robert Lepage during the course of the decade; and Rémi Tourangeau, who developed the notion of jeux scéniques for the purpose of studying pageants. Somewhat on the sidelines of the movement were Gilbert David, who undertook the analysis of theatre programs; Annie Brisset, who focused on the links between theatre translation and identity; and, in particular, Josette Féral, who sought to examine the role of women in the development of acting theory.

6 The decade of the 2000s witnessed diversity in the research questions, approaches, bodies of work, and historic periods privileged. While interest in the hybridization of forms continued to drive research by Josette Féral, Chantal Hébert, Marie-Christine Lesage, and Irène Perreli-Contos, and while Jean-Marc Larrue, Gilbert David, and Yves Jubinville investigated the more or less recent history of Quebec theatre, researchers such as Shawn Huffman and Irène Roy opened up new avenues. The former explored the role of light in theatre and the aesthetics of discomfort. In this he demonstrates his sensitivity to the issue of audience response and a comparative approach (to contemporary theatre in Quebec and Europe), while the latter, at the other end of the spectrum, studied the creative process of the Repère Cycles. Francine Chaîné and Mariette Théberge discussed theatre in secondary school, and Jeanne Bovet examined voice in seventeenth-century French theatre. Gilbert David began to focus on the aesthetics of solo performance, previously having organized symposiums centred on Quebec dramaturgy (Carole Fréchette, Daniel Danis, Larry Tremblay). Josette Féral also pursued research on acting theory during this period while debating, for example, whether theatre acting could be taught. At the end of the decade, Robert Reid became the first researcher to receive support for studying research-creation.

7 Our own decade, the 2010s, henceforth accords importance to the research-creation engaged in by Robert Faguy and by Patrick Leroux in the manner of Jean-Paul Quéinnec, who obtained a Canada Research Chair in the Creation of a Dramaturgy of Sound. Indeed, sound is the topic of the day, conveyed, among other things, by the concept of intermediality, which Jean-Marc Larrue helps to refine while conducting research on radio theatre and electric sound. New technologies are likewise gaining favour: Robert Faguy examines the use of videostaging and I, for my part, note its role in audience response to contemporary Quebec theatre. Studies of the theatre of the Ancien Régime are also expanding, focusing on the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods. Thus, Marie-France Wagner considers the phenom- enon of royal entrances in France, while Louise Frappier, with a similar interest in royalty, examines tragedy in the same era. Nor is playwriting overlooked, with Francine Chaîné and Mariette Théberge analyzing this aspect of the francophone theatre model in Western Canada. Archives and theatre genetics also draw the attention of Yves Jubinville. Finally, a first team of researchers under the direction of Gilbert David has received funding to undertake a review of contemporary theatre practices in Quebec from a socio-aesthetic approach.

8 From the 1990s onward, theatre also occupied a place of importance in large-scale research dealing with literary establishment and history. These included: La vie littéraire au Québec (Literary Life in Quebec) on which Lucie Robert collaborated; the Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec (Dictionary of Quebec Literary Works), which mobilized virtually all stakeholders in the field; and Penser l’histoire de la vie culturelle au Québec (Reflections on the History of Cultural Life in Quebec), the work of a team within the Centre de recherche interuniversitaire sur la littérature et la culture québécoise (CRILCQ), which, as its name indicates, incorporates researchers from every field of art, including the performing arts. 4

9 What can we retain from this rather brief survey of the key orientations of French- language theatre research in Quebec? If such research was driven at the start by historic concerns with a special focus on Quebec theatre, the inclination nowadays is to opt for a larger variety of subjects and to concentrate on contemporary theatre. In addition, the theatrical phenomenon is no longer viewed as a finished product only and from the perspective of audience response: the creative process now attracts the attention of researchers whether their interest lies in theory alone or in both theory and creation. The quest for a balance between aesthetic and social dimensions appears to be a constant in theatre studies in Quebec, as if the two were somehow inextricable. Similarly, there is an over-representation of large-scale projects as opposed to those that require a certain selection or are concerned with limited corpuses. As regards theory, France continues to be the main influence on Quebec theatre studies, even if a few researchers draw inspiration from the United States or other parts of Europe. What’s more, the linguistic divide is obvious, in that one examines francophone research in vain for projects devoted to geographic areas outside French-speaking countries. 5

10 Continuing this discussion of the blind spots in Quebec theatre research, we note the following as well. The influence of cultural studies remains weak within the Quebec community studying the performing arts, with the exception of the feminist perspective of gender studies seen in the work of Josette Féral and Gilbert David. Performance Studies scholarship is recognized but little-used, again demonstrating the persisting rift in French and Anglo-Saxon theory. All this may explain the limited attention given to performance practices outside the legitimate or popular theatre, although exceptions exist. Still more surprising is the absence of the postcolonial perspective per se on the part of specialists whose debates are often framed within a national context. As well, it is unusual for researchers to focus on the work of a single author or director. Michel Tremblay and Robert Lepage are the only two figures in Quebec theatre to have earned this honour, as if artistic practices were most often a collective adventure devoid of leadership or major figures. Finally, the aspect of theatrical practice no doubt most neglected is scenography: in thirty years it has merited no more than a single mention.

11 This last observation leads me to another: as there are few francophone professors teaching theatre studies in Quebec, there is correspondingly little possibility that they will concentrate on more specific issues, adopt less consensual perspectives, or choose highly marginalized corpuses. Yet such work does exist: one has only to consult L’Annuaire théâtral, which publishes research of this nature, which is however, unsupported by funding. This example shows why a more in-depth study of Quebec research calls for consideration of projects that have been turned down by SSHRC and other funding agencies (the community is so small that Quebec scholars are almost never called on to evaluate requests by their colleagues), keeping in mind that Quebec research in languages other than French must also be taken into account. But this should be the goal of a more complete and ambitious assessment than what I propose here. 6

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1