Articles

PuShing Performance Brands in Vancouver 1

What happens when a performing arts institution’s and a producing partner’s mutual desire to attract audiences to intelligent work that speaks to the diverse urban community each claims to represent comes up against a competing corporate brand? I explore this question by investigating the evolving relationship between Vancouver’s PuSh International Performing Arts Festival and SFU Woodward’s, home to Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts and a lightning rod for public debate following a controversial corporate rebranding in the fall of 2010. That rebranding, I argue, also exposes some of the materialist faultlines (cultural, economic, urban) subtending both PuSh’s programming at SFU Woodward’s and the latter’s placed-based identity within Vancouver’s economically depressed and socially marginal Downtown Eastside. The paper is divided into three sections. First, I provide some contextual background on PuSh and SFU Woodward’s, and on the development of their respective performance brands. Next, I draw on interviews with PuSh Artistic and Executive Director Norman Armour and Woodward’s Director of Cultural Programming Michael Boucher to assess the benefits and challenges that have so far accrued as a result of their partnership. Finally, I conclude with readings of three productions staged by PuSh at Woodward’s, arguing that their content helps to foreground competing ideologies of urban sustainability versus gentrification, and the role of non-profits (cultural and educational) in the rebranding of inner-city neighbourhoods.

Que se passe-t-il quand un projet de collaboration entre une institution œuvrant dans le secteur des arts de la scène et un organisme partenaire qui veulent offrir des productions intelligentes à une communauté urbaine diversifiée se heurte à une image de marque concurrentielle ? C’est ce que cherche à savoir Dickinson dans cet article sur l’évolution des rapports entre le PuSh, un festival international des arts de la scène, et SFU Woodward’s, l’école d’arts contemporains de l’Université Simon Fraser, qui se sont attiré les critiques du public après une tentative d’adopter une nouvelle image de marque à l’automne 2010. Dickinson démontre que cette démarche a révélé certaines failles matérialistes (culturelles, économiques, urbaines) qui sous-tendaient à la fois la programmation du festival PuSh à SFU Woodward’s et l’identité même de SFU Woodward’s, inspirée de son emplacement dans le Downtown Eastside de Vancouver, un quartier défavorisé et marginalisé. L’article commence par une mise en contexte du festival PuSh et de SFU Woodward’s pour éclairer le processus qui a mené à la création de leurs images de marque respectives. Ensuite, l’auteur propose des extraits d’entretiens avec Norman Amour, directeur général du festival PuSh, et Michael Boucher, directeur de la programmation et des partenariats culturels à Woodward’s, dans lesquels ces derniers exposent les avantages et les défis résultant de leur partenariat. Pour conclure, Dickinson analyse trois pièces mises en scène au festival PuSh à Woodward’s et fait valoir que leur contenu met en relief le débat idéologique qui oppose le développement urbain durable et l’embourgeoisement et soulève la question du rôle que jouent les organismes sans but lucratif (culturels et éducatifs) dans la transformation de l’image associée aux quartiers du centre-ville.

1 In retail industry parlance, it was the equivalent of a soft opening. Two weeks before Robert Lepage would officially inaugurate the space with the Vancouver premiere of The Blue Dragon, the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival opened the new SFU Woodward’s Fei and Milton Wong Experimental Theatre to its first paying audience. On 20 January 2010, the sixth installment of the festival kicked off with Jérôme Bel’s The Show Must Go On, in many ways the antithesis of Lepage’s spectacular style. Hoarding partially obscured the main atrium entrance, the last of the theatre’s seats had just been installed, and crews were busy at work in other parts of the complex, which was slated to become the new home of Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts later that fall. Still, there was palpable excitement in the air as PuSh Executive Director Norman Armour and Woodward’s Director of Cultural Programming, Michael Boucher, took to the stage to welcome us not just to this new experimental theatre space, but to what those who had been following the progress of the Woodward’s development in Vancouver’s impoverished Downtown Eastside (DTES) hoped would be an equally successful experiment in community engagement and social action. Both had been key planks of the Woodward’s brand ever since the project was announced in 2003, and all the public and private stakeholders and funders—including the city, the province of British Columbia, SFU, developer Ian Gillespie, and individual businessmen and philanthropists like Milton Wong—had bought into it. Armour, a SFU Contemporary Arts alumnus, worked hard to ensure that PuSh was one of the first cultural organizations to get in on the ground floor. 2 And to hear Armour and Boucher tell it that night, it was going to be the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

2 Certainly from their first conversations, Armour and Boucher recognized what each could give the other in terms of brand identity. PuSh, whose mission is in part to present adventurous new work by international, national and local artists “in a spirit of innovation and dialogue” with the communities who inspire and receive it (PuSh, “Mission”), would gain access to SFU Woodward’s state-of-the-art facilities, and in so doing have a recognizable downtown anchor for an important strain of its programming that spoke to the social and cultural complexities of urban living. SFU Woodward’s, under immediate pressure to start paying for itself, could in turn tap into PuSh’s growing audience base, one that tends to be younger, “hipper,” and more receptive to interdisciplinary work—itself a key component of SFU Woodward’s marketability as the newest one-stop performance hub in the city. However, a year after Armour and Boucher stood side-by-side welcoming audiences to The Show Must Go On, their business relationship faced its first big test—at least from an outside perspective. I refer to the fact that in the interim SFU had accepted a $10,000,000 donation from mining corporation Goldcorp for naming rights to the Contemporary Arts complex. The resulting furor over Goldcorp’s less-than-stellar human rights record, combined with the inevitable chatter of gentrification that increased as residents and businesses moved into the complex’s condominium towers and retail spaces, might have meant that the glow around the Woodward’s—and by extension PuSh’s—brand would have been tarnished. By and large that has not happened. At the same time, the years since 2010 have brought other challenges for both organizations in terms of encouraging brand buy-in—from patrons, funders and area residents.

3 Using PuSh and SFU Woodward’s as case studies, I ask: what happens when a performing arts institution’s and a producing partner’s mutual desire to produce intelligent work that speaks to the diverse urban community each claims to represent comes up against a competing corporate brand? How does this expose some of the complexities and faultlines in the “materialist geography” (McKinnie 13) that necessarily—and constitutively—informs both PuSh’s programming at SFU Woodward’s and the latter’s placed-based identity within the DTES? I explore these and related questions by investigating the evolving relationship between PuSh, an annual curated showcase of theatre, dance, music, and multimedia performance, and SFU Woodward’s, not just as a flagship cultural venue that has hosted several of PuSh’s mainstage shows over the past four years, but as a lightning rod for public debate in Vancouver over social sustainability versus gentrification, and the role of non-profits (cultural and educational) in the re-branding of economically depressed and publicly marginal inner-city neighbourhoods. I do so over three inter-related sections. First, I provide some contextual background on each organization, and on the development of their respective performance brands in a city and province that, in addition to chronically underfunding culture, have long spun their wheels in relation to the issues of poverty, homelessness, and addiction facing the DTES. Next, I draw on interviews with Armour and Boucher to assess the benefits and challenges that have so far accrued as a result of the partnership between PuSh and SFU Woodward’s. Finally, I conclude with readings of three productions staged by PuSh on the Wong Theatre stage between 2010-2012, arguing that the content of these performances foregrounds—and frequently comments on—the ideologies and signifying systems (cultural, economic, urban) subsumed within as seemingly innocuous a tagline as “a PuSh presentation at the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts, SFU Woodward’s.” To that end, in each section I also attempt to frame and supplement my analysis of what it means for a PuSh show to play in this venue, in this part of Vancouver, with scholarship in materialist theatre criticism, performance and the city, and theories of cultural branding.

4 My motivation in writing this paper is far from disinterested, and so in the spirit of full disclosure I should clarify that as a Performance Studies scholar based in the English Department at SFU, I collaborate frequently with colleagues in Contemporary Arts and in January 2013 began teaching half-time in the School. My own creative work has also been staged at SFU Woodward’s. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, since 2009 I have served as a member of the Board of the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival Society, including a two-year term as President starting in July 2012. I mention this neither as an endorsement of authenticity for the “insider” knowledge that follows, nor as an apology for the undoubtedly subjective way that knowledge is presented. Rather, as I suggest in the brief coda to this essay, I want to acknowledge the extent to which my own performance “brand”—as a scholar, teacher, practitioner, advocate, donor, and spectator—converges in this nexus of theatrical, institutional, and civic space. Which is also to say that while I have many problems with how my university and city have implemented the social and cultural experiment that is the Woodward’s development, I make no bones about wanting it to work—for everyone.

The Organizations

5 PuSh began in 2003 as a modest theatre series co-presented by Rumble Productions and Touchstone Theatre, led by Armour and Katrina Dunn respectively. In 2005 it became a stand-alone festival, with registered charitable status, its own administrative operations, and Armour as sole Executive Director (the position title was amended to Artistic and Executive Director in 2013). From the beginning, PuSh sought to establish itself as a unique performance brand within the increasingly crowded landscape of regional festivals by being: 1) curated; 2) multidisciplinary; and 3) local, national, and global not just in terms of the scale and scope of the work and artists presented, but in terms of the critical conversations prompted in its audiences and the opportunities for creative exchange fostered among industry partners as a result. To this end, not only do PuSh audiences get to see new works by local companies alongside acclaimed Canadian and international touring shows, but sidebar events like the PuSh Attacks Lab, PuSh Off, and especially the PuSh Assembly provide cultural export and global networking opportunities for artists and producers looking to establish relationships with national and international presenters. Finally, like similar festivals across Canada (Festival TransAmériques in Montreal, High Performance Rodeo in Calgary), North America (Under the Radar in New York, TBA in Portland), and Europe (Avignon, Brighton), PuSh is more than just an animator of the live arts; it is also an incubator, actively commissioning new work from local and international artists and thus, in the words of Alex Ferguson, helping to shift “the Vancouver scene from bystander to participant in the international flow of performance innovation” (110). 3

6 Though no Luminato (and I will come back to the connection momentarily), since its beginnings, PuSh has grown steadily, with attendance at the 2013 festival surpassing 34,000, and with 18 mainstage shows from 11 different countries spread over 16 venues across the city, plus three full weeks of additional programming at Club PuSh, our licensed cabaret on Granville Island. With a total annual budget that since 2010 has hovered between $1.4 and $1.7 million, in 2013 our revenue was split fairly evenly between earned (30%), grant-based (35%), and contributed (35%, which includes foundations, individual donations, corporate and in-kind sponsorships, community partnerships, etc.) (PuSh, “2013 Annual Report”). This represents a substantial realignment since 2009 and 2010, when funding from granting agencies—supplemented by additional special monies related to the 2010 Olympics and Vancouver’s 135 th anniversary in 2011—accounted for more than 45% of PuSh’s income. It also reflects a parallel investment in our development and communications departments. I report this not simply as a self-congratulatory nod to how well the PuSh management and Board have balanced artistic innovation with fiscal responsibility. 4 Rather, I wish to lay bare the consensus reality affecting all not-for-profit arts organizations in Vancouver, one that underpins the larger narrative of the relationship between cultural and urban sustainability I am trying to tell in this paper: that, in the absence of a return to pre-2009 levels of funding for culture in the province, and in the wake of a number of high-profile institutional collapses (most notably that of the Vancouver Playhouse Theatre Company), the future of the performing arts in this city depends on growing not just individual donor bases, but also corporate ones.

7 The latter has involved a lot of soul searching and strategic thinking about the PuSh brand: first, in the summer of 2011, by engaging former Luminato director Chris Lorway to develop a new business plan; next, in the drafting of a Case for Support to help cultivate new donors; then, in the creation of a comprehensive sponsorship guide outlining advertising, marketing and other brand-building opportunities for potential sponsors; and, finally, by engaging the Toronto-based Arts & Communications experiential marketing and public relations firm to help us with both our short-term and long-term corporate sponsorship goals. Interestingly, this last strategy yielded the least return on PuSh’s investment, and the reasons for this are instructive not just in terms of the challenges faced by a multi-disciplinary arts festival with no single, identifiable product—beyond what B. Joseph Pine and James H. Gilmore would identify as the “economic output” of an experience (ix). First, the Vancouver market remains relatively small, meaning that large Toronto-based brands, for example, would likely think twice about the robustness of potential new consumer groups who could be targeted through a PuSh sponsorship. The corollary to this is that Vancouver is home to very few head offices, an exception being those in the mining industry, and prior to the Goldcorp announcement there were some very frank conversations around the PuSh Board table about targeting mining companies for sponsorship funding. However, of even greater consequence to PuSh’s difficulties in attracting a marquee national or even transnational presenting sponsor is the absence of a “civic performance economy” in Vancouver of the sort that McKinnie argues has contributed to the boom of Toronto’s Entertainment District, and in which theatre, especially, has been “appropriated [. . .] to make the consumption of entertainment commodities a civically virtuous, and historically necessary, form of urban development” (49).

8 Which is not to say that a similar pattern of performance-based appropriation isn’t belatedly emerging in Vancouver, and in ways that will not only affect PuSh and SFU Woodward’s, but can be mapped back to the doors of the Wong Theatre. I refer to the recent announcement by Vancouver’s City Hall that it has given the go-ahead for Larwill Park, between Cambie, Dunsmuir, Georgia and Beatty Streets, to be designated the site of a new purpose-built Vancouver Art Gallery (contingent on the Gallery raising $250 million dollars in construction costs over the next two years). With the plans for that development to include the creation of a public square across Cambie Street, between the Gallery and the outdoor plaza abutting the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, a downtown Vancouver cultural precinct is starting to take shape (see Bula). That precinct (see Figure 1) would include the new Gallery, the Queen E and its adjacent civic theatre, the Vancouver Playhouse, as well as the CBC Studios at Hamilton and Georgia Streets (where the PuSh offices will soon be moving), the central branch of the Vancouver Public Library, and a shopping, leisure, and entertainment development slated for the recently closed postal processing plant at Homer and Georgia. 5 Moving further west, the area can also be extended to include the Orpheum and Vogue Theatres on Granville Street and even the current home to the VAG on Robson and Howe (which the City has said it wants to retain as a cultural amenity). By the same token, at the north-easternmost edge of such a district we find the Woodward’s complex. Still something of an outlier geographically, Woodward’s successful integration into this zone arguably depends on it not just filling a consumer gap (in terms of programming, and, eventually, a subscription base) left by the demise of the Playhouse Theatre Company, but also sparking further commercial development between its location and the proposed new VAG. That this makes development virtually synonymous with gentrification means that the practice of civic virtuousness in the burnishing of the PuSh/Woodward’s performance brand is very fraught indeed.

9 It has not been lost on many of us in the organization that the local constraints placed on PuSh in the cultivation of potential corporate sponsors may be a blessing in disguise. Indeed, we have had the most success in attracting recognizable civic brands to PuSh’s programming with projects that combine community engagement with a visible urban presence. Thus, during the 2011 festival local financial co-op Vancity supported our Aboriginal Performance Series and its accompanying free community ticketing program (they returned in 2014 as a partner on our accessibility program). The same year Vancity also contributed to Rimini Protokoll’s demographic portrait of the city, 100% Vancouver (which I discuss below) and Telus Communications sponsored Eat the Street, a collaboration between PuSh and Darren O’Donnell’s Mammalian Diving Reflex that saw schoolchildren from Bridgeview Elementary in Surrey reviewing various Gastown restaurants. Shoe designer John Fluevog, whose flagship Gastown store was one of the local businesses in the 100 block of Water Street incorporated into Mariano Pensotti’s free site-specific La Marea in 2011, has been an event partner ever since. And in 2013 the Vancouver-based artisanal bakery Terra Breads made its first-ever corporate sponsorship in helping to finance Projet In Situ’s Do You See What I Mean?, a guided, blindfolded tour of the city that was also supported by the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. All of these partnerships fit with the SFU Woodward’s brand, and with the strategic vision of my university more generally, which has undergone two major rebrandings of its own in the past eight years—with current president Andrew Petter recently emending our former tagline, “Thinking of the world,” to “Engaging the world” to better reflect his goal of making SFU “Canada’s leading engaged university” via the intersection of “innovative education,” “cutting-edge research,” and perhaps most importantly, “community outreach” (“The Engaged University”). That such outreach, for SFU and PuSh, centres on Woodward’s points to the social capital it has quickly accrued in Vancouver’s urban symbolic, in many respects by trading on an older, more paternalistic economic capitalism the building, in its former incarnation, represented, and about which I will have more to say in the next section.

10 As with PuSh, the origins of the Woodward’s (re)development also date back to 2003. Following a high-profile squat of the building in 2002, Coalition of Progressive Electors councilor and deputy mayor Jim Green spearheaded a plan to make the old Woodward’s department store—once the vibrant retail hub anchoring two historic neighbourhoods, Gastown and Chinatown, and since its shuttering in 1993 a symbol of the larger decline of the DTES—the cornerstone of renewed human, cultural and business investment in the area. The complex as envisioned and ultimately realized, includes a mix of market and social housing, retail businesses, community outreach organizations like W2 Media, 6 and of course SFU’s School for the Contemporary Arts, whose performance facilities comprise, in addition to the Fei and Milton Wong Experimental Theatre, a smaller black box theatre, a dance studio, a 300-seat surround-sound cinema, and an art gallery. When, soon after opening, these facilities were collectively rebranded as the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts at SFU Woodward’s in September 2010, a debate erupted within the university about the ethics of corporate giving. This debate was symptomatic of the contradictions besetting the story of the surrounding area’s redevelopment, where pricey condos and trendy restaurants now abut dilapidated single-room occupancy (SROs) hotels and the country’s first and only safe injection site. Never mind that Goldcorp money contributes to the coffers of several arts organizations throughout Vancouver, nor that the University of British Columbia has similarly benefited from the company’s munificence (Werb). SFU Woodward’s location, combined with its mandate to be responsive (and responsible) to the needs of the many vulnerable communities who inhabit that location, meant that the university’s acceptance of Goldcorp’s gift faced added scrutiny. At the heart of this scrutiny is the question of how one distinguishes between cosmetic rehabilitation of one blackened brand and an ethically engaged assessment of the dirt and grit underneath another?

11 In the case of Goldcorp, whose open-pit Marlin mine in Guatemala has been the focus of claims that liquid waste has entered the river system, leading to clashes with the local Mayan population (see Law), the terms of its donation make it deliberately difficult to answer this question. While 5 of the 10 million dollars given were earmarked for SFU’s capital campaign and general upkeep of Contemporary Arts’ new performance facilities, the other half was to be placed in an endowment fund to support SFU Woodward’s Cultural and Community Program Unit, whose mandate is to partner with DTES community organizations, 7 other non-profit cultural organizations in the city, and SFU faculty, staff and students on social justice forums, artistic workshops, youth clinics, film screenings, free community ticketing programs, and other projects that speak directly to the unique challenges faced by their most vulnerable, marginalized and at-risk constituents (see Vancity Office of Community Engagement). As Slavoj Žižek has noted in his critique of the centralist logic of Naomi Klein’s anti-globalization position in No Logo, the modern corporation has learned to diversify, both in terms of the objects of its investment and the subjects of its philanthropy (185 and ff). 8 So too has the modern university learned to diversify its portfolio of gifts received—which is perhaps why no one in SFU’s senior administration thought twice about accepting the Goldcorp donation. After all, Goldcorp’s equivocal transnational naming rights on the outside of the building are balanced by unimpeachable local philanthropic brand names on the inside: the Audain Gallery; the Djavad Mowafaghian Cinema and World Art Centre; and of course the Fei and Milton Wong Experimental Theatre. At SFU Woodward’s art, performance, education, and urban development are quite materially intertwined, and if, in an era of diminishing public funding, it is difficult to conceive of arts organizations surviving without corporate sponsors (or neighbourhoods surviving without business entrepreneurs), dissent in such matters can provide opportunities to think through and ideally implement initiatives related to an academic institution’s acceptance of major gifts, an arts festival’s linking of its own financial sustainability to a city’s cultural one, a local government’s endorsement of a comprehensive housing strategy, or a national government’s legislation of ethical mining practices.

12 On all of these fronts, PuSh’s performance programming at SFU Woodward’s has had some insightful things to say. At the same time, the very place of those performances, to reference Marvin Carlson seminal study of theatre architecture, speaks to further contradictions in the “urban semiotics” of the location of Woodward’s that must condition our reception of the works we see there (10-12). But before I get to a more detailed analysis of the connections between theatrical content and urban geography, let me first outline the form of the institutional and financial relationship between PuSh and the Woodward’s Cultural Unit as it has so far been negotiated by Armour and Boucher—and how these negotiations have mostly circumvented or ignored the optics of the other brand partner within this ménage, Goldcorp. In the process, I hope to reveal aspects of the larger performance script of brand iconicity upon which these arrangements depend.

The Impresarios

13 In assessing the formidable performance programming duo that Armour and Boucher have become over the past four years, it bears underscoring the extent to which each represents his respective brand. While Armour works closely with different curatorial associates in planning each PuSh Festival, and with various staff and board members on operations and finance, promotion and marketing, development, and community partnerships, his high profile leadership role within the local performance scene more generally, combined with his international contacts, his ability to speak about current work across a range of disciplines, and his passion as a public advocate for the arts, means that Armour is the go-to person for any quote or sound-bite about PuSh. As for Boucher, who likewise has an extensive background in festival directorship, arts management, and creative development, the fact that he began his job during Vancouver’s Olympic year meant that along with the increased pressure to put bums in seats for luminaries like Lepage, he and his unit also received a higher-than-normal level of public exposure locally, nationally, and internationally.

14 The extra scrutiny was the perfect opportunity to establish SFU Woodward’s distinct cultural brand, but the university—to mix my performance metaphors—almost dropped the ball right out of the gate (Boucher). 9 Boucher credits the decision by former SFU President Michael Stevenson (now a member of the PuSh Festival Board) to endorse the School for the Contemporary Arts’ move from its dilapidated portables on Burnaby Mountain to the downtown Woodward’s site with giving the whole redevelopment project credibility; but Boucher was also critical of the initial plan to have the new teaching, administration, and rehearsal/exhibition spaces at Woodward’s absorbed under the larger umbrella of the SFU Vancouver label. 10 Boucher warned senior administrators that in adopting this strategy SFU was jettisoning its biggest brand asset, the Woodward’s name itself. As he suggested in conversation with me, for most Vancouverites the name carries with it not just the palimpsestic weight of a community’s history (past vibrancy, present decline, future recovery), but, via the legendary department store behind it, an equally important aspirational sense of how one might best serve that community: by, for example, keeping prices low and offering skills re-training for its employees during the Depression; by bringing together generations and cultures in its famous food court; and, yes, by sponsoring local cultural activities. Encapsulated within the Woodward’s brand, in other words, was everything that Boucher had been tasked to do as Director of the Cultural Programs Unit.

15 If we analyze the local Vancouver context of Woodward’s within the model of cultural branding outlined by branding guru Douglas B. Holt, it is striking the degree to which the narrative, as outlined by Boucher, conforms to Holt’s seven axioms of brand iconicity. First, the red neon “W” that perched atop the original Woodward’s retail tower, and that now sits, encased in glass, within the redevelopment’s Cordova Street courtyard, remains a potent symbol of “the collective anxieties and desires of a [community]” questioning its identity in response to profound economic, political, and social changes (6). At the same time, the shiny new “W” that has replaced the old one atop the mixed market and social housing residential tower performs an “identity myth that addresses these desires and anxieties,” in this case using the literal bricks and mortar fabrication of the Woodward’s building as the imaginative representation of that which will “stitch back together otherwise damaging tears in the cultural fabric of the [neighbourhood]” (7-8). 11 Residing, as Holt suggests—and, again, as the Woodward’s example quite literally demonstrates—“in the brand,” this myth is additionally experienced through shared “ritual action,” which in this case includes everything from a game of pick-up basketball in the Cordova courtyard to attending free community events and, not least, ticketed shows like those put on by PuSh (8; my emphasis). Moreover, such myths are “set in populist worlds,” from which the iconic brand draws as source material “to create credibility that the myth has authenticity, that it is grounded in the lives of real people” (9)—all of which more or less underpins the mandate of the Woodward’s Cultural Unit. In this respect, as Holt further argues, iconic brands can also be interpreted as performing an “activist role,” leading cultural change by example (9). Additionally, brands attain cultural iconicity not through sustained and consistent messaging, but rather through a few memorable “breakthrough performances” (10); in the case of Woodward’s this arguably pertains to the very opening and dedication of the complex itself, accompanied as it was not just by a cheeky performance from PuSh (discussed below), but also by the installation of Stan Douglas’s Abbott and Cordova, 7 August 1971, a 30 x 50-foot double-sided translucent photo mural on tempered glass, in the building’s outdoor atrium. A meticulous recreation of what is commonly referred to as the Gastown Riot, during which uniformed and undercover police officers attacked a peaceful “smoke-in” organized to protest narcotics agents’ attempts to infiltrate the city’s pot-smoking community, the mural can be read as commemorating the politics of urban conflict specific to the history of the DTES in a way that is consistent with a visual art tradition of institutional critique. Or it can be read as a glib aesthetic commodification of those politics. Either way, it made the site instantly memorable. Finally, Holt suggests that through the combination of these mythologizing principles, an iconic brand accrues a “cultural halo effect,” enhancing by association “the brand’s quality reputation, distinctive benefits, and status value” (10).

16 Which is why, as Boucher additionally told me, he and other staff negotiated with the same administrators not just to keep news of the Goldcorp donation under wraps during the first eight months of SFU Woodward’s operation, but also—despite the very terms of that donation, cited above—to reserve the Woodward’s brand for the cultural programming and community partnership projects emanating from his office. And by and large this has worked. Publicity about the various performances, community forums, and public lectures in which Boucher’s unit has a stake is careful to phrase the sponsorship and hosting roles as follows: SFU Woodward’s at the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts. The vision or philosophy of what might be done and what relationships animated within this cultural space are kept separate from whatever name appears on the physical building itself.

17 As for Armour, he likewise made it clear that PuSh was buying into the Woodward’s philosophy, and not the Goldcorp building (Armour). 12 While, as he admitted, it was nice to gain a physical downtown site for a core section of the Festival’s programming, of greater value in Armour’s mind was, again, the sense of history and cultural and community engagement already embedded within the SFU Woodward’s brand. However, for Armour this burnishing by association extends as much to the SFU part of the equation as it does to the Woodward’s one. Part of the attraction in PuSh partnering with SFU Woodward’s, according to Armour, was that the Festival shared a set of core values with the School for Contemporary Arts that would take up residence within its walls. Granted, as an alumnus of the School, Armour is far from unbiased on this issue. Nevertheless it goes without saying that what he cites as some of the key principles he learned during his time at the SCA—a lack of dogma and ideological hierarchies around performance aesthetics, fostering collaboration and partnerships inside and outside the studio, understanding the relationship between one’s practice and the overall social and cultural sustainability of one’s city (a point I take up below)—are all cornerstones of PuSh’s own performance brand.

18 Armour, who prefers to think of branding as a form of messaging, also made it clear that he does not see programming choices and artistic and curatorial planning as separate from audience relations, outreach and advocacy, sound human resources investment, and fiscal accountability. He is as concerned with ensuring that in the general public’s and private funders’ minds the Festival is both responsibly run and responsive to its various constituencies as he is with the quality of the work shown. As such, he felt that the blank slate offered by SFU Woodward’s in a cultural landscape riddled with the corpses of past festival partnerships presented a unique opportunity to reproduce key aspects of PuSh’s mission, vision, and values in a partner organization’s own evolving mandate. And here, PuSh’s relationship with Woodward’s extends the partnership model it has cultivated over the years with other co-presenters in the city, including the Arts Club, the Vancouver East Cultural Centre, the Dance Centre, Music on Main, and, more recently, a reinvigorated Ballet BC and the upstart DanceHouse Vancouver. All these organizations tell a much different story about the depth and robustness of the performance ecology in Vancouver than do more common headline-grabbing stories like the Playhouse Theatre Company’s demise, a point Armour emphasized during his televised speech at the gala opening to the 2013 PuSh Festival, held only weeks after it was announced that the iconic Waldorf Hotel on East Hastings Street, former home to an eclectic mix of cultural programming, had been sold and was slated for redevelopment. This is the narrative the Vancouver live art community should start telling to stakeholders and funders, according to Armour, along with the fact that much of the success of the above-listed companies comes from their conscious mix of local and global programming.

19 PuSh’s relationship with SFU Woodward’s is key not least because, unlike the other companies, it does not have a dedicated performance space, and thus its ongoing tenancy helps to cement a shared brand iconicity between venue and festival programming equivalent to Harbourfront Centre’s annual hosting of the World Stage Performance Series in Toronto. Coincidentally, Boucher headed the World Stage Festival (as it was formerly known) in the early 1990s, and from the outset he has stated that his own biggest branding goal has been to make it clear (to artistic organizations and the general public) that SFU Woodward’s is not interested in being known solely as a production venue, but rather as an active cultural programmer with a requisite degree of curatorial influence in the presentation and community engagement of the work on which it partners.

20 With these goals in mind, Boucher has recently overseen the establishment of the 149 Arts Society, a non-profit organization with registered charitable status that can fundraise independent of both SFU’s Advancement Office and the Vancity Office of Community Engagement at Woodward’s. The shows on which SFU Woodward’s partners with PuSh— including 149’s first co-presentation, Seattle-based zoe|juniper’s A Crack in Everything, which opened the 2013 festival—were the direct impetus for this move. To put things bluntly, Boucher wanted more say in PuSh’s programming at Woodward’s, and in return Armour wanted Woodward’s to shoulder more of this programming’s financial risk, particularly in the 440-seat Wong Theatre, which remains a challenge to fill. Indeed, from their very first conversations, Armour has felt free to push back on some of the financial terms of PuSh’s relationship with SFU Woodward’s (whose facilities are expensive to rent), counting on Boucher, as a former festival director, to educate university bean-counters about the nature of investment in the performing arts at this time in this part of the city, where a break-even (let alone profit) model is unrealistic for anything other than a Lepage show during an Olympics year. As both men suggested, SFU Woodward’s investment in PuSh (and vice-versa) involves an entirely different sort of capital, one that is about the narrative of a community that can be told in part through the shows on its stages.

The Shows

21 As materialist theatre semioticians such as Carlson, Susan Bennett, Gay McAuley, and Ric Knowles have consistently pointed out, the experience of live performance begins long before one enters the auditorium, takes one’s seat, and awaits the dimming of the house lights. Everything from the building’s external façade and signage to its interior front of house areas is coded with meaning and, as such, conditions and influences what we see. This extends, as well, to the performance space’s physical location within a larger urban geography, both in terms of how, as Knowles suggests, that location is “read” ideologically and the phenomenological “experience of the spectator in getting there,” including “the degree of physical or psychological difficulty involved in traversing familiar or unfamiliar, comfortable or uncomfortable districts, the distance between the theatre and its community (or ‘target audience’), the proximity and cost of public transportation and parking, and so on” (80). In the case of SFU Woodward’s, the material ways in which the DTES neighbourhood contextualizes the building’s performance spaces and, vice versa, the ways in which these spaces decontextualize the neighbourhood, are instructive. Referring back to the emerging downtown cultural/performance precinct on whose periphery I have suggested Woodward’s now sits, there can be no doubt that, in relation to the two side-by-side civic theatres, the Queen E and the Playhouse, that front onto Hamilton Street between Georgia and Dunsmuir, making the trek to Woodward’s—at least in the first couple of years after it opened—involved a conscious acknowledgement that one was leaving behind the trend of Yaletown for the tat of the DTES. PuSh, in aligning itself aesthetically and politically with Woodward’s, was likewise positioning its more avant-garde and experimental offerings on the complex’s stages in counter-distinction to the more canonical/“high art” repertory work of the resident companies at the Queen E and the Playhouse. 13

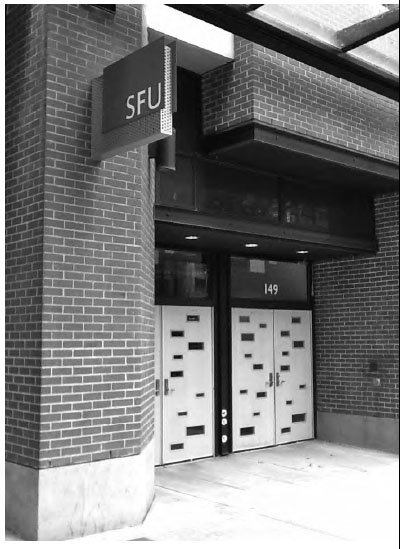

22 At the same time, in one fundamental way SFU Woodward’s literally turns its back on the neighbourhood in which it is located, and, by extension, its residents—who are meant to be constituent partners in rather than mere “target audiences” for many of its programs. I refer to the fact that while the official address of the building is 149 West Hastings Street, and while the layout of the ground floor reception areas—from the position of the box office to the streetfront window of the Audain Gallery—is oriented toward these doors, the main entrance has become the far grander approach from the Cordova Street courtyard (see Figure 2). In addition to emphasizing monumentality and scale (from Douglas’s mural to the glass-encased old department store “W” to the angular sign proclaiming SFU’s logo and, underneath, the “Goldcorp Centre for the Arts”), this entrance also encloses and shields patrons from their immediate urban environment. Consider, as well, that Cordova Street shuttles audience members not only more directly to and from the safe harbour of the Waterfront Station terminus to the new Canada Line subway, but also to Gastown, with its mix of tourist shops, designer clothing stores, and upscale restaurants. Finally, if one drives to see a show at Woodward’s, and if one parks in the carpark off Cordova, it is actually possible to access the building’s courtyard entrance without setting foot on a DTES street: via an overhead walkway across Cordova Street that was memorably exploited by Adrienne Wong in her contribution to PodPlays, a quartet of audio-dramas-cum-walking-tours presented by PuSh as part of its 2011 festival. By contrast, accessing SFU Woodward’s via the West Hastings entrance (see Figure 3), which until recently was signed almost invisibly, and whose doors were frequently locked by security guards during the early days of building operation as a deterrent to local street traffic, requires that patrons confront other, more immediately visible, signs of this community’s material reality. The story of SFU Woodward’s two front doors also opens up additional vantage points on PuSh’s programming at the venue, which has from the very beginning deliberately risked “affronting” its various audiences.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 323 Since its opening at the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris in 2001, where scandalized audience members walked out, hissed and hurled epithets, and even attempted to hijack the stage (D’Amelio 92), Jérôme Bel’s The Show Must Go On has become a global performance brand in its own right, a concept piece that has travelled to hundreds of festivals and venues around the world, letting local audiences—including at PuSh in 2010—in on the ruse. The Show begins with a DJ sitting at a makeshift console downstage centre, a stack of CDs on the table beside him. One by one, the songs he plays illustrate the action (or non-action) on stage. And vice versa. Thus, during the first song— “Tonight” from West Side Story—the audience remains in the dark, in mute anticipation and then, as the song plays out and the stage stays black, increasingly apprehensive expectation of what the evening portends. Those expectations are confounded further during the second song, the Hair anthem “Let the Sunshine In,” which is apparently the cue for the stage lights to slowly be upped to full illumination. Only halfway through the third song, The Beatles’s “Come Together,” does the cast actually assemble on stage. And only during the fourth song, David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance,” do they start to move, busting into a mix of goofy club grooves during each chorus. Indeed, to the extent that dance takes place at all in The Show, it is mostly in the form of quotation, gestural repetition, or, again, mere illustration: the parody of ballet steps the women in the cast launch into during Lionel Ritchie’s “Ballerina Girl”; the exhaustive—and exhausting—display of the choreography from the “Macarena” wedding song; the mimicking of the Winslet/DiCaprio Titanic pose to Céline Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On.”

24 In its exploration of a clichéd musical canvas, its thwarting of expectations regarding “dance as dance” in favour of what Bel calls “a theatre of dance” (Bel), and in the imperative of its title, The Show insists that for it to go on the active participation of the audience is required. In Bel’s case, audience interaction is facilitated by stillness, and by what Tim Etchells refers to as the work’s many “voids” (10, 16- 17). When the theatre is suddenly plunged into darkness, or when the cast abruptly abandons the stage, or when they stand motionless before us, we in the audience must produce the drama. In this regard, while the familiar musical selections may help to facilitate our collective affective bonding, it is arguably what Etchells describes as the “sculptural” quality of the performers’ (non)movement (12) that incites the release of that emotion. Thus, for me, the most powerful moment came when the cast stares out at the audience for the duration of The Police’s “Every Breath You Take” and George Michael’s “I Want Your Sex.” Instead of separately reacting to the lyrics of the songs, performers and audience are now additionally reacting to each other, a transmission of affect that, as per Teresa Brennan, also establishes the terms of the relationship between the others in each group (51). Lined up next to each other on stage, the performers are connected physically, and by the common purpose of their look. ‘How are you connected to the people beside you?’ that look asks. Show us.

25 But it is precisely the qualitative difference in the way audiences show these connections (by dancing together, or hurling abuse together, or staring back in stony silence together) that prompts Toni D’Amelio to insist on the importance of contextualizing the “climate of feeling” specific to a given performance’s local production (92-3). While the soundtrack of The Show might constitute a shared lingua franca of pop schmaltz, the affective politics of its reception cannot be predetermined. As D’Amelio recounts, the outrage that greeted The Show’s French premiere was culturally specific not just to Paris, but to the Théâtre de la Ville venue, whose audiences tend disproportionately to be comprised of other dancers and artists, and who enjoy “assisting the spectacle” by loudly declaring their pleasure, and more often than not their displeasure, for a piece (92). By contrast, The Show has been received quite warmly in other cities. Partly this has to do with Bel’s insistence that the work be cast locally, and ideally with a mix of recognizable community figures, not all of whom may be professional performers.

26 In this regard, SFU Woodward’s as venue was also an important mediating factor in the emotions circulating between performers and audience, not to mention within the audience itself—but to completely different affective ends than in Paris. Purposefully comprised of several key figures representing various community outreach, arts advocacy, and civic planning constituencies, PuSh’s cast for The Show was in part meant to brand not just the grand social aspirations of this new building, but of those it might most usefully serve. And it is worth noting that the most represented constituency in the cast was that of current SFU Contemporary Arts students and recent graduates. This is significant to the mutually reinforcing brand politics of PuSh and SFU Woodward’s in a number of ways. For while PuSh has successfully collaborated with students, graduates, and faculty from UBC’s Department of Theatre and Film, Langara College’s Studio 58, and Capilano University’s performing arts program on several projects, the largely SFU cast for The Show reflected not just the primary theoretical purpose of the Woodward’s space—to train and exhibit the work of Contemporary Arts students—but also the impact many of those students (starting with Armour himself) have made on the cultural landscape of Vancouver in founding or co-founding companies like Theatre Replacement, Neworld Theatre, and Boca del Lupo, all of whom have performed at PuSh. Needless to say, I have a stake in leveraging, here and elsewhere, the SFU-specific institutional connotations of PuSh’s performance brand, both in terms of advocating for arts education’s contributions to the sustainability of the city and as a way of explaining the role PuSh has come to play in my pedagogy.

27 PuSh arrives early in Vancouver’s arts calendar and, as such, an added benefit of the Festival’s 2011 January launch was that it coincided with the kickoff of year-long celebrations of the 125 th anniversary of the city’s incorporation. Several shows in the Festival had been planned around the theme of “cityness,” securing additional special monies from City Hall that went some distance toward offsetting the gap in our programming budget from the previous Olympic year, when all arts organizations in the city were atypically flush. One such show was 100% Vancouver, the lead-off piece at the Fei and Milton Wong Theatre. The piece was developed by the Berlin-based Rimini Protokoll, who the year before had brought PuSh audiences an original commission called Best Before, a theatrical rumination on conflict and consensus in the democratic process by way of an interactive video game. 100% Vancouver was locally produced (in this case by Theatre Replacement, in conjunction with PuSh and SFU Woodward’s Cultural Programming Office), a version of similar performances previously staged in Berlin and Vienna. Using Rimini’s trademark theatrical protocol of having “everyday experts” (i.e. non-professional actors) reflect back to audiences a version of the communities from which they come, the show gathers on stage 100 Vancouverites who each represent 1% of the city’s total population, and who have been selected according to the following demographic criteria: gender, age, marital status, ethnicity/mother tongue, and neighbourhood. As Tim Carlson, dramaturge for the piece, notes in an essay included in the publication booklet accompanying the production, whereas in Best Before’s video-game format audience members were invited to create—via their on-screen avatars—virtual versions of themselves, in 100% Vancouver “flesh-and-bone citizens” literally stand in for the abstract virtuality of numerical statistics (“Matters of Protokoll”).

28 Theoretically this process of statistical embodiment is supposed to unfold as a daisy chain of once-removed relationships; each individual selected is in turn responsible for finding someone they know who matches the requisite demographic profile of the next link in the chain, and so on. However, as expert number 1 of 100, statistics librarian Patti Wotherspoon, tells us at the top of the show, in the case of 100% Vancouver, the producers had to step in on several occasions to shore up gaps in the chain by calling on their own acquaintances and by putting out an open call for participants matching the statistical data they hadn’t yet humanized in a participating expert. And even with these measures, Wotherspoon also let us know that three Vancouver neighbourhoods—including, most interestingly, upscale Shaughnessy—were unrepresented on stage.

29 Given her professional expertise, Wotherspoon also had something to say about the creative use and interpretation of statistics, as well as the politics of the Canadian long-form census, whose 2011 application was poised to be its last, thanks to the Conservative Party’s highly controversial decision to jettison it. One of the questions asked of the participants in 100% Vancouver is how many of them support the long form census; the overwhelming major- ity respond in the affirmative. And expert number 69, Patricia Morris, offers a compelling account of administering the 2006 census door-to-door in her (and SFU Woodward’s) neighbourhood of the DTES, visiting SROs and asking the occupants if, among other things, they had ever operated heavy farm machinery.

30 One would think that all of this would make for some pretty lifeless theatre, but from the opening roll-call of names and proffering of special objects, I was hooked. Based on video interviews with each participant, Carlson and director Amiel Gladstone put together a portrait of the city that affectingly spotlights individual stories through oral testimony: such as that of number 86, Joan Symons, who moved to Vancouver to escape memories of her first husband, who died in WW II, only to lose her eight-year old daughter a few years later, and who subsequently became a real estate agent and now has 22 grandchildren; or number 70, Minh Thai Nguyen, who came to Vancouver from Vietnam only five months prior to the start of rehearsals of 100% in order to provide better educational opportunities for his children, and who was hilarious on the social similarities between Vietnamese and Canadians. At the same time, the creative team was equally adept at corralling their experts in a series of simple yet striking visual tableaux. Indeed, the massings of bodies into ME and NOT ME categories in response to a series of questions (“Were you born in Canada?” “Do you recycle?” “Do you smoke pot?” “Have you been in prison?” “Do you know someone First Nations?” “Are you happy?,” etc.) offers a revealing profile of Vancouver, as George Pendle suggests in his essay in the accompanying publication, “not just demographically, but temperamentally and morally as well” (“Colour by numbers”).

31 In marketing terms, such a profile is a psychographic one, segmenting potential consumers according to personality, interests, activities, attitudes, values, lifestyle, and so on, rather than aggregating them by age or gender or race (Gunter and Furnham). By such data, companies such as Amazon or iTunes are able to recommend products for you, and not just by tracking the brands you have bought in the past, but, even more crucially, by developing an algorithm capable of listing what additional brands users “like you” have bought. The lure of such information is especially strong in the creative sector, where for many performing arts organizations (PuSh included) it can often mark the difference between a successful and unsuccessful year in terms of programming and attendance, and where it can be used to solicit corporate sponsors. Then, too, developers and city planners increasingly look to such data when deciding where and what to build, and how to sell it. And yet, while an indigent creative class might be, according to Richard Florida, a crucial measure of a city’s vitality, 14 it is also often the first wave of the same neighbourhood’s gentrification. It is no accident that the DTES, in addition to having the highest percentage of street homeless in Vancouver also has, along with adjacent neighbourhoods like Strathcona and Mount Pleasant, one of the highest proportions of working artists in North America (Brown). But arguably the fact that Gastown is currently the hottest district in the city has less to do with the artists who have made it cool to live and play there than with a city-sponsored incentive program launched the same year as the Woodward’s redevelopment, which encouraged investors and entrepreneurs to renovate and open businesses in the area’s previously abandoned historic buildings (Woo).

32 The perceived links between this program and Woodward’s have led several DTES activists and organizations to brand the latter as the most visible symbol of the area’s economic dysfunction. Indeed a 2010 report prepared by the Carnegie Community Action Project called Pushed Out: Escalating Rents in the Downtown Eastside states that “Gentrification of the DTES, spurred by Woodward’s and market housing development is a major cause of the rent increases, which will also help push low-income residents out of their DTES community” (4). This debate was renewed in the spring of 2013 when area residents and anti-gentrification activists picketed the upscale restaurant Pidgin soon after its opening at Carrall and Hastings Streets. Similar protests of other establishments soon followed, prompting owners to defend the ethics of their business practices, including the employment many provide to local residents in their kitchens, the free community meals they sponsor, and so on. It sounded a lot like the mandate SFU Woodward’s Vancity Office of Community Engagement, the link to which on the Woodward’s website sits just below a tab labeled “Where to Eat.” All of which is to say that if, in its demographic and psychographic portrait of the city, a piece like 100% arguably reveals the DTES as the nexus from which all other civic relationships radiate in Vancouver, it also leaves unprobed the full complexity of the obligations that attend those relationships.

33 The opening show at SFU Woodward’s during the 2012 PuSh Festival was Amarillo, by Mexico’s Teatro Linea de Sombra. Amarillo is a mid-size city in the Texas panhandle, a long way from the Mexican border. But it is the destination of our nameless, faceless, ageless protagonist in this piece, who departs his native Mexico for its unknown horizons, only to come up against the physical wall the United States has erected to bar his entry, as well as the wall of silence surrounding his disappearance. And, in fact, we learn that there are many names, with many different faces, and of many different ages who have so disappeared, with performer Raúl Mendoza at one particularly mesmerizing moment donning a series of sweatshirts to signify the thousands of Mexican citizens who yearly risk their lives for a better life across the border. In this sequence, and elsewhere in the production, Jesús Cuevas’ haunting throat-singing accompanies the physical action. Cuevas plays a sort of Trickster/seer/sheriff character, the basso profundo of his vocalizations variously a lure, a warning, a dirge.

34 Structurally, Amarillo is comprised of a series of monologues (translated via English surtitles) that are visually enhanced by recorded and live video projections on the giant white wall that serves as the monumental backdrop to the set. The live feeds result in several stunning effects, as when Mendoza climbs some ladder-like steps jutting out of the stage-right side of the wall, eventually hanging off of the top one while the image of a train is projected behind him. The creators even rigged cameras up in the rafters, which resulted in equally arresting images of the various patterns created by the objects and material substances strewn across the stage over the course of the production. Two of the most prominent of those substances are water and sand. When, for example, Mendoza recounts the dangers of dying from dehydration in the desert, performers Alicia Laguna, María Luna, and Antígona González set out 40-50 gallon size plastic jugs, some of them already filled, others with a smaller container emptying its contents into them—which, when illuminated with a small flashlight and captured via the overhead video, creates a projected image that is at once magical and threatening. Ditto the sand—mostly white, but occasionally coloured red—that empties out of bags attached to cables that are lowered and raised at different points, or that the performers spill from shoes and bottles and their own hands to create lines and borders and compasses on the stage. At once the impassable desert that sucks dry all that moisture in those water bottles and that literally swallows up so many Mexican bodies, the bags of sand also neatly telegraph the image of illegal drugs being conveyed across the border, whether in the minds of American law enforcement officers or very materially in the backpacks of desperate Mexican immigrants corralled into becoming mules for drug lords who promise them money and safe passage across the border. Then, too, the suspended and slowly emptying bags of sand also convey an image of the hourglass, time slowly but surely slipping away from all who find themselves in this no man’s land of the border.

35 In the context of the Conservative government’s wholesale overhaul of Canada’s citizenship, immigration and refugee policies since 2009, which has included tightening the conditions of the government’s Skilled and Temporary Foreign Worker Programs and, most controversially, imposing new visa requirements for all Mexican travelers to Canada, the national significance of Amarillo was likely not lost on many in PuSh’s audience. However, on opening night Amarillo also tellingly theatricalized some more immediately local political connections to the show’s content when at one point Mendoza interrupted the action to read a letter to the “citizens of Vancouver.” The letter urged members of the audience (including SFU President Andrew Petter, who sat in the front row) to protest the damage wrought upon the environment and local indigenous populations by mining companies operating in Mexico. One such company is, of course, Goldcorp. While its name, affixed over the entrance to the SFU Woodward’s complex, and duly acknowledged in PuSh’s program guide, has yet to eclipse either brand in terms of public recognition and iconicity, its indexical relationship to each is likewise key, as I hope I have also explained, to any performative evaluation—and economic valuation—of what those brands do symbolically and materially. 15

The Author

36 I have never been conscious of having an academic brand, let alone needing to manage one in the way Queens of All Media such as Oprah Winfrey or Martha Stewart must. Yet, in the course of revising this paper, I have become increasingly aware of just how much of my professional and extra-professional identity has recently come to be located in what both theatre semioticians and business brand analysts would identify as the various connotative indices that accrue, separately and together, to the PuSh/Woodward’s/SFU troika (Elam 8-10; Danesi 36-8). In the space between introducing a PuSh show on a given night at Woodward’s (and stumping for donations), reviewing it the next day on a blog called “Performance, Place, and Politics,” and talking about it later that week with my students (whom I likely would have conscripted into attending), I am participating in what Roland Barthes would call a “second-order” cultural myth that has as much to do with my own compensatory anxieties about the value of what I do as a performance patron, critic, and teacher as it does with my belief in the mutually constitutive purposes of PuSh and SFU Woodward’s. Locating the inside and the outside of those anxieties within the larger cultural, urban, and economic framework of Vancouver’s historical present is a fundamental part of this essay’s project—and its politics.