Articles

The Gallant Invalid:

The Stage Consumptive and the Making of a Canadian Myth

This essay explores theatrical and cultural performances of pivotal figures in Canada’s colonial history as they relate to a forgotten chapter of theatre history and an image of masculinity it helped to create. The “gallant invalid” of the nineteenth-century stage was a consumptive young man hopelessly in love with a woman he could not possess and forced to steel his ailing body for a battle against forces that threatened honour and virtue. His first major theatrical incarnation came in the guise of Henri Muller in Alexandre Dumas père and Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois’s drama Angèle (1833). A crosser of national, class, and gender boundaries, Muller experiences deep emotions that the audience glimpses via the performed symptoms of his disease. As English translations of plays influenced by Angèle crossed first the Channel and then the Atlantic, I argue, they helped to create an internationally recognizable male consumptive type who shared these characteristics. In Canada, performances of this type shaped both British imperial mythology and an emergent narrative of Canadian political heroism. They transformed the received image of one of the founding heroes of imperial Canadian history, General James Wolfe, and shaped the public persona of the ‘great conciliator’ of French and English Canada, Wilfrid Laurier. This operation helped to establish the agency of the bourgeois, politically liberal male subject within the new nation. Yet it also associated his power with an acknowledgement of its own transience, rooting imperial masculinity in a performance of mortality that destabilized the very mastery it sustained.

Cet article explore les performances théâtrales et culturelles de quelques grandes figures de l’histoire coloniale du Canada qui, participants d’un chapitre oublié de l’histoire du théâtre, auront aidé à créer une certaine image de la masculinité. Le « galant invalide » des scènes du dix-neuvième siècle était un tuberculeux éperdument amoureux d’une femme hors d’atteinte, qui devait rassembler toutes les forces de son corps malade pour contrer les forces menaçant l’honneur et la vertu. La première grande figure de ce genre au théâtre fut le personnage de Henri Muller, dans la pièce Angèle (1833) d’Alexandre Dumas père et Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois. Transgressant les frontières érigées entre les nations, les classes sociales et les sexes, Muller vit des émotions intenses que le public entrevoit dans la représentation des symptômes de sa maladie. Barker fait valoir que les traductions anglaises de pièces inspirées par Angèle, qui ont traversé La Manche puis l’Atlantique, ont contribué à créer le personnage-type du tuberculeux, doté des mêmes caractéristiques, identifiable sur les scènes du monde. Au Canada, de telles représentations ont façonné à la fois la mythologie impériale anglaise et le récit émergeant de l’héroïsme politique canadien. Elles ont transformé l’image reçue du général James Wolfe, un des grands pionniers de l’histoire impériale au Canada, et ont façonné le personnage public de Wilfrid Laurier, ce « grand conciliateur » des Canadas français et anglais. L’opération a permis d’établir la fonction d’agent du sujet mâle bourgeois et politiquement libéral au sein de la nouvelle nation. Toutefois, on associait ainsi son pouvoir à une reconnaissance de sa nature transitoire et on ancrait la masculinité impériale dans une performance de la mortalité qui déstabilise la domination qu’elle est censée entretenir.

[I]l passait et repassait au milieu de nous, calme, grave même, l’air mélancolique et maladif, mais toujours poli, affable, bienveillant. Nous avions pour lui un sentiment d’amitié mêlé de respect et de sympathie, car il nous semblait voir sur sa figure pâle et triste les ombres de la mort.

(He came and went amongst us, calm, even grave, looking melancholy and sickly, but always polite, affable, gracious. Towards him we had a feeling of friendship mixed with respect and with sympathy, for it seemed to us that we could see on his pale and sad face the shadows of death.) ––Laurent-Olivier David 1

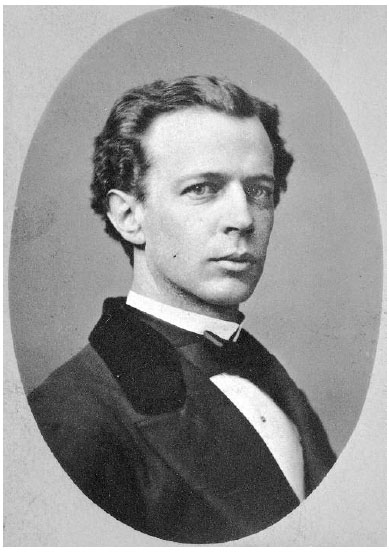

1 So Laurent-Olivier David, lifelong friend of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, described Laurier as he was when they met in 1864: a struggling young Montreal lawyer threatened by pulmonary tuberculosis, then usually referred to in English as ‘consumption’ or ‘phthisis’ and in French as ‘la phtisie.’ 2 Writing in 1905, when Laurier had been Prime Minister of Canada for nine years, David went on to devote three pages to the contrast between his subject’s physical weakness and his strength of character. Why should David so emphasize an aspect of Laurier’s experience that might handicap his political career? What were the potential advantages of such a representation, for David as a biographer and for Laurier as a prominent actor on the political stage? This essay strives to answer these questions by turning to a forgotten chapter of theatre history and an image of masculinity it helped to create: a figure that I, following the historian Francis Parkman, dub “the gallant invalid.”

2 The gallant invalid of the nineteenth-century stage was a consumptive young man, hopelessly in love with a woman he could not possess and forced to steel his ailing body for a battle against forces that threatened his sense of honour and virtue. After establishing the social and literary contexts that informed his creation, this essay explores his first major theatrical incarnation: Henri Muller in Alexandre Dumas père and Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois’s drama Angèle (1833). Muller’s role exemplifies key aspects of the gallant invalid’s persona. A crosser of national, class, and gender boundaries, he experiences deep emotions that the audience glimpses via the performed symptoms of his disease. As English translations of plays influenced by Angèle crossed first the Channel and then the Atlantic, I argue, they helped to create an internationally recognizable male consumptive type who shared these characteristics. In Canada, cultural performances of this type proved useful both to British imperial mythology and to an emergent narrative of Canadian political heroism. They transformed the received image of one of the founding heroes of colonial Canadian history, General James Wolfe, and shaped the public persona of the ‘great conciliator’ of French and English Canada, Wilfrid Laurier. This operation helped to establish the agency of the bourgeois, politically liberal male subject within the new nation. Yet it also associated his power with an acknowledgment of its own transience, rooting imperial masculinity in a performance of mortality that quietly destabilized the very mastery it sustained.

3 If the human experience of disease is founded as much in “cultural performance” as in pathological processes (Frankenberg 622), then a traumatic social reality compelled the performance of powerful narratives about the consumptive patient in the nineteenth century. Pulmonary tuberculosis was one of the era’s most widely fatal illnesses, accounting for about one in five deaths in England in the century’s opening decades (Bryne 12) and as many as one in four deaths in France in its closing years (Barnes 4). The highest levels of mortality from the disease tended to be among patients in their twenties and thirties (Bewell 186), their deaths often drawn out over months or years of chronic suffering. The identification of the tubercle bacillus by Robert Koch in 1882 linked this suffering to infectious bacteria that may create lesions in many human organs but most frequently attack the lungs into which they are inhaled. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, however, most Northern European and North American doctors and patients viewed consumption primarily as the product of heredity (Dubos 33-43) or sometimes of environmental, nervous, or emotional factors (Lawlor 52-5). Thus, the nineteenth-century consumptive patient was less part of a mass “outbreak narrative” (Wald 2) than of a tale of individual doom to which s/he was condemned by personal history and temperament. The well-known symptoms of the illness—persistent coughing, fever, night sweats, breathlessness, chest pain, pallor, fatigue, weight loss—offered an index of that doom, with the dramatic spectacle of a hemorrhage from the lungs providing the classic signifier of a terminal prognosis (Grellet and Kruse 66). The cultural performance of tuberculosis thus hinged on the means by which the hidden destruction of the body forced its way into audibility and visibility. The “disease of the self” (Lawlor and Suzuki 461), consumption was also the disease that, more than any other, externalized that self’s inner secrets.

4 In her seminal 1978 work, Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag traced the ways in which literature and the arts have reflected such constructions of consumption, portraying it as an illness that “dissolved the gross body, etherealized the personality, expanded consciousness” (19-20) and that thus could serve as a metaphor both for entrapment within and for transcendence of the material realities of emergent modernity. To Sontag, such metaphorization was a “preposterous” rewriting of sufferers’ painful lived experience (35). More recent studies have complicated her condemnation, bringing nuance to our understanding of the ways in which tuberculosis was aestheticized and showing how they answered the needs of communities coping with an incurable and terrifying illness. 3 Most have cited Alexandre Dumas fils’ durably popular drama La Dame aux Camélias (1852) and its heroine, the courtesan redeemed by self-sacrificing love and a consumptive death, as an example of the process. 4 To date, however, none have given serious consideration to the wider range of theatrical representations of consumption in the nineteenth century. These representations complicate a number of common scholarly arguments about tuberculosis and the cultural imaginary. In particular, they qualify Byrne’s conclusion that “consumption was generally perceived to be a ‘female disease’ and that the consumptive in nineteenth-century literature and art was usually represented as a woman” (150). To be sure, many aspects of consumption—the languor it occasioned; the slenderness and transparent skin of sufferers; the patient’s inability to work consistently—squared with dominant nineteenth-century European conceptions of feminine fragility. Even so, a large proportion of the era’s theatrical consumptives were male.

5 That the early nineteenth-century stage should have linked masculinity and consumption is unsurprising, given the number of celebrated literary and artistic male sufferers. The German playwright Friedrich Schiller and poet Novalis; the Polish composer Frédéric Chopin; and the English poet John Keats rank among the best-known male consumptives of pre-Romantic and Romantic Europe. Perhaps the key figure in the development of the theatrical male consumptive, however, was the tubercular French poet Charles-Hubert Millevoye (1782-1816). Inspired by the Englishman Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751), Millevoye created the prototypical image of the doomed jeune malade, the young invalid who, “triste, et mourant à son aurore” (“sad, and dying in the dawn of his years”), wanders elegiacally amid an autumnal wood in his 1811 poem “La Chute des Feuilles” (“The Falling of the Leaves”; Millevoye 79). 5 Raging against his own mortality, longing for the beloved he cannot now marry, and melancholically contemplating the transience of life, Millevoye’s jeune malade is Faust, Werther, and Hamlet by turns. Like the Prince of Denmark’s black suit, his pallor and languor are indices of that within that passeth show, hinting at both his physical decay and his emotional agony. When he resigns himself to his fate with the words, “Tombe, tombe, feuille éphémère!” (“Fall, fall, ephemeral leaf!”; 81), he achieves Christ-like status, echoing the savior’s final note of acceptance: “it is finished” (John 19.30).

6 “La Chute des Feuilles” gained huge popularity. In 1839, more than a quarter century after its first publication, the great critic Sainte-Beuve described it as “la pièce dont tous se souviennent” (“the piece all remember”), noting the many translations, imitations, and citations it had inspired in European literature (649-50). Real-life young men imitated its hero; in his Memoirs, Alexandre Dumas père recalls wryly that in 1820s Paris, “la mode était à la maladie de poitrine; tout le monde était poitrinaire, les poètes surtout; il était de bon ton de cracher le sang à chaque émotion un peu vive, et de mourir avant trente ans” (“the fashion was for consumption; everyone was consumptive, especially poets; it was in good taste to spit blood after every somewhat lively emotion, and to die before reaching thirty”; 9.179). Across Europe, eighteenth-century developments in medical theory and social practice had fed into a close discursive association between consumption, emotional sensibility, and refinement (Porter 67-8; Lawlor, Consumption 43-58). In this context, consumptive suffering became one means by which members of the rising middle classes could perform a quasi-aristocratic distinction (Porter 67). In the France of the 1820s and 30s, embroiled in ongoing social struggle after the failure of revolutionary republicanism and of Napoléon’s empire, the modish disease with its connotations of spiritual and social superiority took on particular political significance: a point that emerged clearly when Angèle, ou l’Échelle des Femmes (Angèle, or the Ladder of Women) premiered at Paris’ Théâtre Porte-Saint-Martin in December 1833.

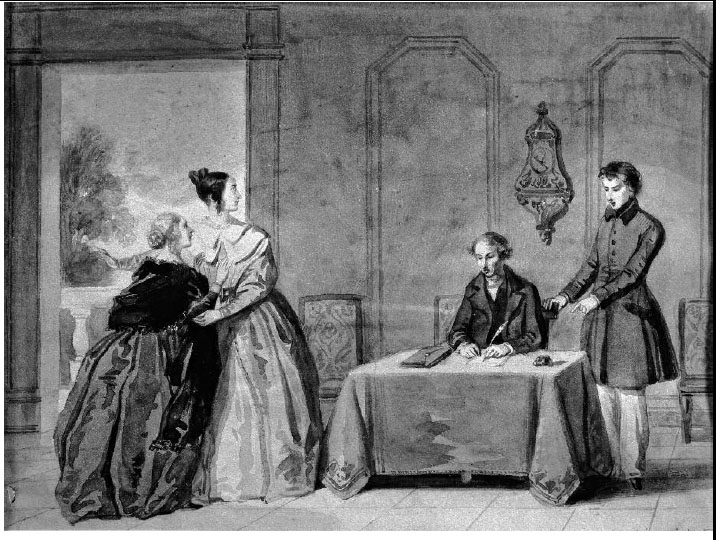

7 In Angèle, Alexandre Dumas père and his collaborator Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois made theatrical gold from the jeune malade of “La Chute des Feuilles.” 6 One of Dumas’ innovative drames modernes, or Romantic dramas of modern life, the play is set during and reflects upon the social significance of the revolution of July 1830, which saw the abdication of the last Bourbon king, Charles X, and the ascent of the so-called “roi bourgeois” Louis-Philippe. Its eponymous, aristocratic heroine is seduced by a nobly born but impecunious and disillusioned Don Juan, the Baron Alfred d’Alvimar, who makes his way in the world by linking himself romantically to women of influence. When he realizes that her mother, a widow close to the inner circle of the new King, is sexually attracted to him, he dumps the daughter (now pregnant with his child) for maman. Fortunately for Angèle, both her baby and her reputation are saved by Henri Muller, a young country doctor who adores her but who has never told his love because he knows that he is mortally ill with the consumption that has already killed his mother, brother, and sister. Muller delivers Angèle’s baby and strives to force Alfred to marry her. When that fails, he kills him in a duel and weds Angèle himself, claiming the paternity of her child.

8 The success of Angèle—which was not only reviewed extensively in France, England, and North America, but also parodied onstage and in print, 7 transformed into a novel by the English writer G.W.M. Reynolds, 8 and translated into multiple languages 9 —shows how effectively Dumas’ and Bourgeois’ inspiration spoke to the needs of the age. Critics saw Henri Muller as the drama’s beau rôle or plum part (Romand 152) and his illness as one of its major points of interest. In the Revue de Paris, Amédée Pichot went so far as to remark that the appearance of “un malade atteint de phthisie pulmonaire” (“an invalid suffering from pulmonary phthisis”) was the play’s only truly original element (47). The critic of La France Littéraire praised “Muller le poitrinaire” as “une belle création” (“Muller the consumptive: a beautiful creation”; “Théâtres” 217). Some years later, when the play’s initial success had subsided, Auguste Bourjot asserted that its key legacy would be its evocation of “les enfants de l’époque, maladifs et incomplets, tels que le poitrinaire Henri Muller” (“the children of our age, sickly and incomplete, like the consumptive Henri Muller”; 90).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 It was precisely as a poitrinaire that Henri Muller personified the artistically and politically turbulent age of the French Romantic theatre. In the 1827 preface to his play Cromwell, Victor Hugo had described the “new” French drama as bringing together the sublime and the grotesque, the body and the soul (11-12). In this spirit, Henri Muller’s potentially grotesque, ailing body acts throughout Angèle as an index of his deeply felt inner life. Soon after he is introduced in the play’s first act, he is left alone at the window to watch Angèle flirt with d’Alvimar:

t-il donc besoin de l’accompagner sans cesse?

Il tousse, et porte sa main avec douleur à sa poitrine.

Cette chaleur me tue.

with her this way; why does he have to follow her about all the time?

He coughs, and brings his hand to his chest in pain.

This heat is killing me.)

(Dumas, Angèle 48)

Henri’s cough and wincing gesture immediately identify the seat of his complaint for the theatrical audience. Their placement after his glimpse of Angèle, however, suggests that his symptoms are exacerbated as much by emotional turmoil as by the weather. In a manner that prefigures the theatrical language of realism codified by Constantin Stanislavsky, the actions of his body illuminate the secrets of his individual subjectivity.

10 The depth of Henri’s sensibility relates closely to his second typically Romantic characteristic: his hybrid national identity. Dumas and his peers had taken much of their dramatic inspiration from German models, especially from the plays of Friedrich Schiller (Falconnet 32). With his French Christian name and German surname, Henri Muller embodies the French appropriation of German Romanticism. He also exemplifies the French construction of Germans, popularized by Germaine de Staël’s 1813 study De l’Allemagne (Of Germany), as an intensely emotional people for whom “l’amour est une religion” (“love is a religion”; De Staël 29). Dumas’s contemporary Ernest Falconnet underlined these points when he applauded Dumas for being “le premier qui ait essayé, par le Muller d’Angèle, la personnification d’un caractère allemand” (“the first to try, in the Muller of Angèle, the portrayal of a German character”; 32). Hippolyte Romand, meanwhile, tied Henri’s illness directly to German Romanticism when he praised the character as “une des plus touchantes inventions de l’auteur, […] poitrinaire comme Novalis” (“one of the author’s most touching creations, […] consumptive like Novalis”; 151). Muller crossed national lines, challenging d’Alvimar’s ancien régime French cynicism with the idealistic passion of the German poet whose illness he shared.

11 Finally, the triumph of the young doctor whose physical weakness figured both his social inferiority and his spiritual superiority to his noble adversary quietly affirmed liberal, or even radical, political principles. For the feminist Saint-Simoniste Suzanne Voilquin, Angèle was a revolutionary critique of the sexual double standard. With his strong soul in a feeble body, Henri struck her as the very incarnation of the young men of her time who strove against formidable opposition to “changer les rapports des sexes, à les baser sur la justice, sur l’égalité, sur l’amour” (“to change relations between the sexes, to base them on justice, on equality, on love”; 101). If Muller’s illness feminized him by rendering him physically frail and emotionally sensitive, implied Voilquin, this simply allowed him to share more fully in the experience of the victimized woman, Angèle. For the young leftist Hippolyte Fortoul, meanwhile, Muller’s victory in the final duel figured the triumph of the disenfranchised but virtuous lower half of society against “la partie pourrie de la nation française, [le] débris de la vieille aristocratie” (“the rotten part of the French nation, the debris of the old aristocracy”) embodied by d’Alvimar (528). Muller’s selfless adoption of Angèle’s blue-blooded child trumpeted a new social order in which corrupt old privilege ceded to the power of a bourgeoisie that (quite literally) assumed the Name of the Father.

12 More conservative critics objected to this use of the pathologized masculine body to disrupt time-honoured hierarchies. The nobly-born Englishman Henry Lytton Bulwer complained that Dumas went too far in making heroes of “sickly-faced apothecaries in the frontispiece attitude of Lord Byron” (326), rejecting the pretensions of the phthisic bourgeois either to the audience’s admiration or to the aristocratic Byron’s glamour. Bulwer implied that only the French would think of such risible conceptions and distanced his own Britishness from them, forcefully reasserting the national boundaries that Muller’s hybrid identity had blurred. In the Revue de Paris, meanwhile, Pichot deprecated the very idea of representing consumption onstage, especially in a man: “Je ne sache pas que les maladies, en général, soient du domaine de l’art, et celle-ci moins qu’une autre” (“I am not sure that illnesses, in general, form part of art’s domain, and this one less than any other”), he complained, clearly viewing the onstage representation of disease as a violation of aesthetic decorum (49). When Henri challenged Alfred to duel despite his own frailty, he admitted, “M. Alexandre Dumas a su tirer une belle scène de la débilité physique de ce personnage” (“M. Alexandre Dumas was able to make an effective scene out of the character’s physical weakness”), but he added that “j’eusse mieux aimé que cette débilité fut le produit d’une tout autre cause, des suites de quelque honorable blessure, par exemple” (“I would have preferred that weakness to be the product of quite another cause: of the effects of some honorable wound, for example”) (49). Pichot’s words imply discomfort with the very feminization that had pleased Voilquin. In place of Muller’s vulnerable and domesticated masculinity, he longed for a more martial version of male heroism.

13 The performance of Lockroy, the jeune premier who created the role of Henri Muller, appears partially to have mitigated such concerns. Lockroy clearly brought a certain melancholy elegance to his performance of Muller’s ailment; writing in 1861, the critic Jules Janin recalled that “il était ce qui s’appelle un beau ténébreux, et toussait avec autant de grâce que la Dame aux camélias plus tard” (“He was what’s called a beau ténébreux [a dark and broodingly handsome man], and coughed as gracefully as the Lady of the Camellias would later”) (2). Given that the disapproving Pichot thanked him “de s’être au moins dispensé de la toux” (“for having at least dispensed with the cough”; 49), Lockroy likely not only aestheticized the consumptive’s most painfully conspicuous symptom, but actually minimized its appearance in performance. In place of an indecorously clinical mimesis of tubercular agony, sources hint that he used a gestural language that countered the helpless (feminizing) lassitude of illness with a fiercely willed (masculinizing) energy. The play text frequently notes Muller’s tendency to lean heavily on furniture as if determinedly holding himself upright (Dumas, Angèle 81, 103, 252). Pichot, too, described Lockroy’s Henri as challenging Alfred to a duel “debout contre une table comme une apparition” (“supporting himself against a table, looking like a ghost”; 54). The dialectical relationship thus created between the character’s physical debility and his steadfast courage impressed even the censorious critic, who commented with approbation that “sa faiblesse [devient] sa force” (“his weakness [becomes] his strength”; Pichot 54).

14 Nevertheless, Lockroy was very far from eschewing the pathos attendant upon the performance of phthisis. If he played down the cough, he played up the consumptive’s pallor. In Roberge’s pamphlet parody of the play, a provincial bourgeoise, Mme Gibou, replays the experience of watching Angèle for her friends’ benefit. She rarely mentions Henri without commenting on his paleness, informing her companions that Henri’s stout father resembles his frail son “comme un pain à cacheter rouge à un pain à cacheter blanc” (“as red sealing wax does white”; 30) and vividly evoking the latter’s appearance after the final duel: “pâle, tout défait, coiffé en coup de vent” (“pale, all disheveled, his hair standing on end”; 54). Another critic described Muller at the same moment as “pâle également et de la mort qu’il vient de donner et de celle qui l’attend bientôt” (“as pale as the death he has just given and the death that will soon be his”; “R” 3). At the very point of Henri’s triumph, Lockroy’s makeup reminded the audience that his doom would follow hard upon d’Alvimar’s. In his much-lauded performance, the power of the young bourgeois went hand in hand with its own precariousness.

15 Henri Muller was so popular with audiences in the 1830s that a Parisian fashion magazine later ascribed the tendency of elegant young men to affect “des airs de poitrinaire” to the influence of “un drame d’Alexandre Dumas” (“Premier Lorgnon” 409). Angèle was followed by a string of plays in which a similarly pale and lovelorn young consumptive played a pivotal role. Among them, Barrière and Thiboust’s Les Filles de Marbre (1853) and Octave Feuillet’s Dalila (1857) proved particularly influential. In both plays, the phthisic hero is a middle-class crosser of national boundaries: in Dalila, André Roswein is a German composer in Naples, while in Les Filles de Marbre Raphael Didier is a French sculptor who has studied in Italy. Dalila, which eventually served as a vehicle for Sarah Bernhardt, features a moment that exemplifies the manner in which the consumptive’s disease renders visible his turbulent emotions. When the seductive villainess, Leonora, demands that he prove he is dying for her love, Roswein throws down his blood-stained handkerchief as evidence. The prop represents a new step in the mimesis of tubercular symptoms onstage, externalizing the consuming inner violence of the disease far more directly than Henri Muller’s pallor and tendency to lean on furniture. But Leonora merely scoffs: “Qu’est-ce que cela prouve? Tous les artistes crachent le sang!” (“What does that prove? All artists spit blood!”; Feuillet 63). Clearly, the consumptive hero had assumed the status of a type. Indeed, by the 1850s his popularity in the French theatre was so well-known that an English critic could quip that the actor Charles Fechter, “who made a great success in the Filles de Marbres [sic],— dying of a deep decline during one hundred nights—afterwards refused the principle part in a new comedy because the hero was not consumptive” (“Paris” 1110).

16 Les Filles de Marbre marked the moment of the consumptive hero’s full acceptance on English-speaking stages. The play, in which Raphael Didier’s illness is precipitated by his hopeless love for a heartless coquette, formed a riposte to the highly successful La Dame aux Camélias: “[i]n the first the lady dies for love of the man; in the other, the man for the lady,” wrote the English diplomat Henry Greville (243). Translated into English by Charles Selby as The Marble Heart in 1854, it played to great applause across England, the United States and Canada well into the 1870s. The pathos of its hero was a crucial factor in this transatlantic success. One critic commented that Selby’s adaptation “would most certainly have been damned” in England had it not been for the actor Leigh Murray, “who had the power of making the heart of his audience vibrate to his emotions” in the role (“A Leap”). Edwin Booth, celebrated for his melancholy and intellectual Hamlet, achieved a triumph in the play’s American premiere in Sacramento when, “after muddling dully through the early passages, [he sprung] the grand tear-jerking scene with all stops out” (Shattuck 8). In Canada, one Halifax reviewer ascribed the feat of bridging the gap between English and French tastes solely to the “tragic power” of E. A. Sothern as Raphael:

Derided by Lytton Bulwer as a sign of French decadence and emasculation, the consumptive hero, his torments, and the virtuoso acting they invited now sold The Marble Heart to an English-speaking audience. This theatrical success contributed in turn to the larger transatlantic process by which Romantic notions of consumption as the ennobling disease of the “Western middle class” spread from Europe to North America (Bewell 186). 10

17 As works like The Marble Heart moved across the Atlantic, the constructions of emotional, national, class, and gender identity that had shaped the consumptive heroes of Europe became available for the representation of North American cultural idols. In some cases, they remodeled established reputations. One such refashioning appears in William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Virginians (1857-9), a ‘novel of the last century’ that tells the story of the stalwart Warrington brothers. Their friend James Wolfe, though just over thirty, is already one of the leading military men of his generation. When Harry Warrington depicts all soldiers as strapping specimens of healthy manhood, his beloved Hetty Lambert uses Wolfe as a counterexample: “James Wolfe is not a strong man. He seems quite weakly and ill. When he was here last he was coughing the whole time, and as pale as if he had seen a ghost” (498). Later, as Wolfe and Harry prepare to set off for war, Hetty’s father sighs that:

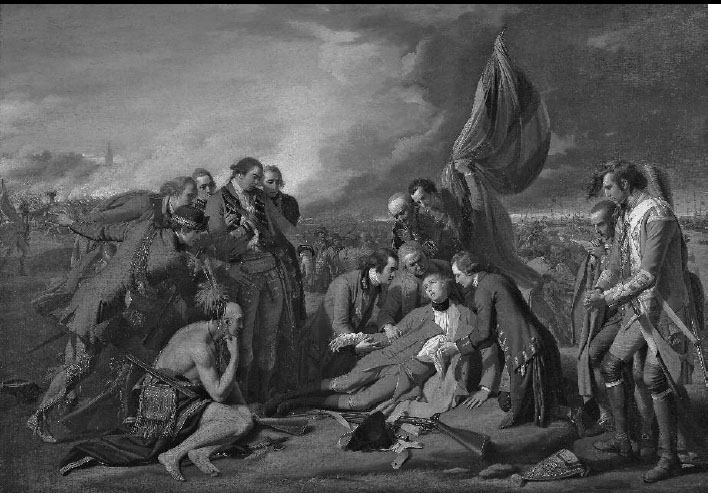

The lineaments of the consumptive hero of Dumas and Bourgeois, bracing his disintegrating body and adoring soul for a final struggle, are clear in Thackeray’s representation of the man who will lead the successful British assault on the French army at the Plains of Abraham and die in the process. 11

18 Thanks to his role in the siege of Québec, the historical General James Wolfe (1727-59) had by 1859 enjoyed a century near the head of the pantheon of British imperial heroes. As the title of George Cockings’s 1766 play The Conquest of Canada; or The Siege of Quebec suggests, British citizens on both sides of the Atlantic saw the victory at the Plains of Abraham as the decisive one in the struggle between France and England for possession of the North American colonies. Because Wolfe had died gloriously in action immediately after formulating the battle strategy, he enjoyed the lion’s share of credit for Britain’s success. In his survey of the resulting glut of eighteenth-century portrayals of Wolfe, Alan McNairn notes that the first wave of them focused primarily upon his bravery and his Britishness. In Cockings’s play, for example, Wolfe responds with disdain to pleas that he stay safely at home:

In such representations, Wolfe’s strength and courage appear inseparable from his chauvinistic patriotism (NcNairn 19).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 219 Already, however, fissures in this martial persona prepared Wolfe for his later assumption of the consumptive hero’s mantle. The General was a scion of the prosperous middle classes whose clashes with his aristocratic fellow officers in the English army occasioned considerable gossip after his death (McNairn 22). When he departed England for the last time in 1759, he left behind a fiancée, Katherine Lowther, whom he was destined never to marry (Coutu 112). Moreover, he suffered throughout his short life from a range of ailments, including chronic seasickness and what he called “rheumatism and the gravel” (Wilson 403). Painful bladder or kidney stones caused Wolfe particular agony during the siege of Québec, when he was also attacked by fever (Brumwell 247-8). With all these maladies, declared one writer shortly after his death, “providence seemed not to promise that he should remain long among us” (qtd. in McNairn 21). From the first, Wolfe’s valour was tinged with pathos in the public imagination.

20 The softer side of Wolfe’s persona came increasingly to the fore as the eighteenth century waned. On its first exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1771, Benjamin West’s painting The Death of General Wolfe became an immediate icon; among the factors in its success were its use of modern dress, which flagged Wolfe sartorially as a figure with whom the contemporary middle classes could identify, and its emotionally potent positioning of Wolfe as Christ in a military pieta (McNairn 125, 165-6). Even more crucially, near the end of the eigh-teenth century John Robison, who had been a young midshipman at the siege of Québec, began to tell the tale of Wolfe reading Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” to his troops on the eve of his final battle (McNairn 235-6). The “Elegy,” with its mournful reminder that “the paths of glory lead but to the grave” (l.36), soon became as closely linked to Wolfe in English imaginations as it was in France to the jeune malade of Millevoye’s “Chute des Feuilles.” Add to this the fact that Wolfe himself had once alluded satirically to his own “meagre, consumptive, decaying figure” (Wilson 246), and he was clearly prime material for consumptive hero status. 12

21 Strikingly, Wolfe seems to have gained that status only in the late 1850s, at about the same time that Henri Muller’s descendants were becoming popular attractions on transatlantic stages. Thackeray’s pale and coughing Wolfe in The Virginians, published serially in both England and North America in 1857-9, appears to be the first mass-market instance of the notion. 13 Soon, however, the image of Wolfe struggling up from his sickbed to die gloriously on the Plains of Abraham had become canonical. In 1884, Francis Parkman immortalized it in his influential history Montcalm and Wolfe. “Once and again,” writes Parkman as he surveys Wolfe’s letters, “he calmly counts the chances whether or not he can compel his feeble body to bear him on till the work is done” (308). Parkman memorably contrasts Wolfe’s fragility with the strength of the English war machine:

The doughty Briton lionized in eighteenth-century representations now stands isolated from the imperium for which he fights, every brave but tottering inch the brother of Henri Muller. 14

22 Why did this image of Wolfe gain such cultural purchase at this particular point in the General’s posthumous life? Vital aspects of Wolfe’s biography undoubtedly fitted the lineaments of the consumptive hero, and a century after his death he was ripe for rebranding via this chic new persona. But the transformation of Wolfe into the gallant invalid also offered deeper socio-political benefits at this moment in history. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the pressure of increasing unrest in Lower Canada created discomfort around the eighteenth-century conception of Wolfe as a triumphant Briton. As early as 1804, English writers expressed concerns that a monument to Wolfe at the Anglican Cathedral in Quebec City might cause “hurt feelings” among the French (qtd. in McNairn 237). By 1860, the English poet Barry Cornwall was coupling Montcalm and Wolfe in shared glory as “the only men whom death could not divide, / A monument indeed for earthly pride” (qtd. in McNairn 238). In his persona as the gallant invalid, Wolfe became a symbol of the fragility of human power rather than of the triumph of one nation over another. The transnationalism that had long been associated with the consumptive hero could only aid in this process of transformation. The dying man who realized that “the paths of glory lead but to the grave” was more Montcalm’s brother than his enemy.

23 These potentially conciliatory implications of the consumptive hero’s persona bring us closer to answering the question that began this essay: why Wilfrid Laurier, a successful politician in late nineteenth-century Canada, might consent to be portrayed as a poitrinaire in the Romantic mold. Laurier (1841-1919) fit the theatrical model of the consumptive hero even more neatly than Wolfe. The son of a small-town, middle-class family, he lost his mother to tuberculosis when he was six years old and his sister to the same illness when he was fourteen. He himself suffered chronic lung trouble throughout his life. In his twenties, his blood-spitting terrified his friends (Bélanger 48), and he wrote melancholy verses meditating à la Millevoye on the brevity of life: “poussés du destin qui nous tient enchaînés, / Nos jours fuient du berceau vers la tombe entraînés” (“propelled by the destiny that holds us in chains, / Our days rush from the cradle toward the tomb”; qtd. in Bélanger 27). For years, Laurier gave his ill-health as the main reason for his failure to marry his beloved Zoë Lafontaine, writing to her, “Malheureusement je crains de porter dans ma poitrine un germe de mort qu’aucune puissance au monde ne pourra arracher” (“Sadly, I fear that I carry a germ of death in my chest that no power on earth can root out”; qtd. in Bélanger 60). Henri Muller, concealing his love from Angèle so as not to tie her to “un amant déjà fiancé à la tombe” (“a lover already engaged to the tomb”; Romand 151), could hardly have put it better.

24 Doctors eventually convinced Laurier that he suffered from chronic bronchitis, rather than from tuberculosis, and he went on to marry Zoë and to begin his political career. Still, he never quite abandoned the aura of the consumptive hero. On his first election trail in 1871 he hemorrhaged repeatedly but stalwartly kept campaigning (Skelton 27). Far from viewing his frailty as a political deficit, his supporters treated it as something of an asset. David, for instance, emphasized it in an 1874 description he wrote for Le Courrier de Montréal that later formed the introductory sentence of an 1890 collection of Laurier’s speeches published in both French and English. David’s Laurier is “[t]all, thin, and straight as an arrow, with the pale, sickly face of the student, hair chestnut, thick and inclined to curl; countenance mild, serious, and rendered sympathetic by an air of melancholy” (Barthe iii). In 1889, J.S. Willison reminisced in a similar vein in the Toronto Globe about the politician’s behaviour at his “famous address on Liberalism, delivered in the city of Quebec in the summer of 1877”:

In such passages, Laurier’s precarious health, his pallor, his melancholy, and even his nerves signify the sincerity and passion hidden beneath the young lawyer’s “calm and measured” exterior. They suggest, too, that he engages in politics not from crass personal ambition but from a self-sacrificing desire to serve his country. This construction from his youth clung about Laurier to the end. After he died, a parliamentary colleague recalled admiringly that when he was invited to take on the leadership of the Liberal party, “the answer of this man who, beneath a stolid exterior hid very deep emotions, his answer was a sob” (Right Honorable 30).

25 As a strategy through which to convey the politically valuable commodity of “deep emotion,” Laurier’s air de poitrinaire had its risks, not least because of its links to theatrical performance. By the late nineteenth century, the notion that consumptive symptoms were actions that a man might play had become widespread. An 1880 issue of the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro featured a satirical column entitled “Le Manuel du Poitrinaire” (“The Consumptive’s Manual”) that offered to teach young men how to “tousser avec charmet [. . .] râler avec delicatesse” (“cough which charm and groan with delicacy”) (121). The “Manual” guided the would-be consumptive through the performances he could undertake to convince others of his impending doom, including stifling his imaginary cough into an elegant handkerchief and spending the month of September wrapped in his dressing gown re-reading “La Chute des Feuilles.” Laurier’s critics sometimes found his Romantic persona similarly phony. In The Masques of Ottawa (1921), his exposé of the “great show” of the Canadian parliament in which “politicians are the actors” (2),“Domino” (the critic Augustus Bridle) portrayed Laurier as a performer whose arsenal of “obvious tricks” included his delicate health:

Such scenes, Bridle implies, were effective theatre, but one would do ill to mistake them for evidence of the sincerity the public might desire in a leader.

26 Bridle maintained that an aura of emotional depth and inwardness was, finally, only the means and not the end of Laurier’s performances on the political stage. He believed that the leader sought first of all to satisfy the very parvenu ambition the consumptive pose had helped him to deny; “the son of the village surveyor from the tin-spired parish of St. Lin,” he remarked, “made himself very nearly monarch of all he surveyed” (31). Yet behind this power-grab Bridle saw another, deeper goal: the reshaping of a nation. “Laurier made a second conquest of Canada,” he wrote:

For Bridle, Laurier’s greatest achievement was the creation of a hybrid French and English Canada that loyally served the British Empire even as its policies of tolerance quietly contradicted the more exclusionary side of British patriotism. Laurier’s air de poitrinaire can be seen as one of the means by which he performed this marriage of French and English Canada, of “Wolfe and Montcalm.” Thanks to its French theatrical roots and to the rebirth of Wolfe as the gallant invalid, the role of the consumptive hero enjoyed associations in Canada both with French culture and with English valour. As a gallant invalid, the “picturesque” Laurier personified an ideal of Canada emergent in his time: a nation middle-class, domestic, bilingual, brave but gentle, invested in its colonial past but not chauvinistically or exclusively British. The romance of the gallant invalid may thus be seen as one of the foundation stones of the romance of liberal Canada itself.

27 The consumptive hero’s continued appearances in representations of Canada’s past attest to the staying power of this romance. Even today, General James Wolfe remains the gallant invalid in popular performance. The multi-media presentation Odyssey at the Plains of Abraham National Historical Site features a deathly pale Wolfe stifling a nagging cough. The 2004 film Nouvelle-France, a French/Canadian co-production set during the siege of Quebec, portrays Wolfe in only two scenes; but during those scenes English actor Jason Isaacs as the General manages to cough, lean heavily against a table, gasp for breath, shed a few melancholy tears, and pull himself together to toast the King, all in a few minutes. And in 2010, Ottawa playwright Louis Lemire represented Wolfe in his bilingual play Inséparable as “the young[,] idealistic, but arrogant and inexperienced British general who goes fearlessly into battle with his tubercular cough—a true romantic hero” (Ruprecht). A modern middleclass Canadian spectator is more likely to perceive this “romantic hero” as an object of nostalgia or a sentimental cliché than as a combatant in a struggle for social ascendency. Such representations may thus work to undermine a sense of the power and destructiveness of the British colonial project of which Wolfe formed a part. In the new millennium, a tubercular Wolfe still represents the kinder, gentler face of Canada’s imperial history.

28 Laurier, too, is often the noble sufferer in contemporary performance. Louis-Georges Carrier’s 1986 CBC miniseries, Laurier, for instance, played young Laurier’s racking cough and longing for Zoë Lafontaine as the attributes of a political saint in the making. More complex is the approach of Michael Hollingsworth’s Laurier play in his cycle, The History of the Village of Small Huts. In this gleeful spoof of a Victorian society melodrama, the youthful Laurier appears as a parody of the Romantic gallant invalid: a young man with “a weak chest but a strong heart” (219) who answers “yes” to virtually every question—less, it appears, to conciliate than to avoid committing himself. Early in his career, the very idea of confederation exacerbates both Laurier’s illness and his political zeal:

LAURIER: They can’t do that. We demand a referendum, a plebiscite, call it what you will, at least an election. [. . .]

(Laurier puts a handkerchief to his mouth and coughs blood.)

LAURIER: We must protest, we must organize. We must protest. (224)

Soon, however, anti-confederationism and consumption go together by the wayside as Laurier ascends the political ladder. True, his image of a Canada simultaneously French and English, colonial and independent, remains as defiantly hybridized as the identity of the consumptive hero. “To be and not to be,” he declares as he surveys his political career near play’s end; “that is the question. The answer too. We have become a nation without breaking the colonial tie” (249). Yet the dream fails; Laurier’s waffling is eventually rejected by the electorate and alienates most of the people who love him. The pathos that surrounds him at the play’s end is not the noble pathos of the gallant invalid, but the pathos of age that has outlived—and perhaps even betrayed—the ideals of its youth. Such pathos encourages critical reflection on Laurier’s liberal vision of Canada rather than nostalgia for or sentimental acceptance of it.

29 Hollingsworth’s ironic distance from the metaphors of the gallant invalid may prove salutary in today’s context. The consumptive hero created on the French stage, exported to England and North America, and appropriated into the historical and political imaginary of the emergent Canadian confederation contributed to the articulation of some of the nine-teenth century’s key social struggles: between aristocratic and bourgeois rule, between nationalism and transnationalism, between martial and domestic constructions of masculinity. These struggles have, in turn, helped to shape certain dominant contemporary notions of Canadian identity—as middle-class, as multicultural, as grounded in heterosexual family ties—that often exclude or oppress those who do not conform to them. Nostalgia for the nation’s colonial past can have a similar effect. Thus, the figure of the gallant invalid, initially associated with social transformation, may all too easily be co-opted into the service of the status quo.

30 Still, the line of descent I have explored here suggests that the power associated with Euro-North American masculine identities in the age of Empire was far from absolute. Consumptive heroes both imagined and real assert mastery over their worlds: witness Henri Muller giving his name to Angèle’s child, Wolfe planting Britannia’s flag on Canada’s fair domain, and Laurier co-opting the young nation into his vision of liberal compromise. Yet the future to which these men lay claim is opened to their control by the possibility of their impending absence from it. The Wolfe who conquers Quebec is already doomed; the Laurier who wins the hearts of the electorate has one foot in the grave. If the mythology of the gallant invalid functions as a smokescreen concealing the brutal reality of the bourgeois male power that has dominated much of Canada’s history, it also underlines the impermanence of all regimes of dominance. Even at the height of their control, these prototypical “dead white men” are always on the verge of being just that—dead. In the final lines of Angèle Henri Muller tells Angèle that he has killed d’Alvimar so that she will never have to blush before a man. She reminds him that he has effectively assumed d’Alvimar’s power: “Vous oubliez, Henri, qu’il y a encore un autre qui sait tout, et devant lequel j’aurai à rougir” (“You forget, Henri, that there is another who knows everything, and before whom I will have to blush”). “Oh!,” he sighs as the curtain falls, “celui-là a si peu de temps à vivre!”: “Oh! But he has so short a time to live!” (Dumas, Angèle 254).

My sincere thanks to Marlis Schweitzer, to the other members of the “Men of the Empire” team (Heather Davis-Fisch and Stephen Johnson), and to TRiC’s readers for their invaluable suggestions during this paper’s development.