Articles

An “Unmanly and Insidious Attack”:

Child Actress Jean Davenport and the Performance of Masculinity in 1840s Jamaica and Newfoundland 1

This essay examines how and in what way the movement of child performers along global theatrical circuits in the mid-nineteenth century served British imperial interests and aroused debate about colonial identity. It analyzes two politically charged controversies that surrounded child actress Jean Davenport: the first erupted in the island colony of Jamaica in September 1840, the second in the island colony of Newfoundland in August 1841. In both locations, colonial theatres and newspapers became the staging ground for heated debates about the actress’s proclaimed virtuosity, notably her portrayal of male characters and her supposed resemblance to Edmund Kean. These debates quickly extended beyond a consideration of Davenport’s acting abilities, however, to include discussions about the responsibilities of theatre audiences and critics, definitions of gentlemanly behaviour, and the relationship between colonial-settlers and strangers from the metropole. Central to the analysis of the controversy surrounding Jean Davenport’s appearances in Jamaica and Newfoundland, then, is a consideration of how theatrical representations of masculinity—in this case, male characters played by a young girl—provoked discussion of, and gave rise to, other performances of masculinity in two very different colonial settings.

Dans cet article, Schweitzer s’intéresse aux jeunes artistes de la scène dans les circuits de tournées théâtrales servant des intérêts impériaux britanniques au milieu du dix-neuvième siècle et aux débats sur l’identité coloniale qu’ils ont provoqués. Schweitzer se penche sur deux controverses lourdes d’implications politiques et émotives autour de la jeune comédienne Jean Davenport. La première a eu lieu dans la colonie insulaire de Jamaïque en septembre 1840, et la deuxième, dans la colonie insulaire de Terre-Neuve en août 1841. Dans les deux cas, des théâtres et des journaux coloniaux sont devenus le lieu d’un débat enflammé sur la virtuosité de la comédienne, notamment pour sa représentation de personnages masculins et sa soi-disant ressemblance avec Edmund Kean. Or, le débat a vite dépassé la question du talent de la comédienne Davenport pour susciter de vifs débats sur la responsabilité du public et de la critique, le comportement d’un gentleman et la relation entre colons et étrangers venus de la métropole. Au centre de cette analyse de la controverse suscitée par le passage de Jean Davenport en Jamaïque et à Terre-Neuve, s’inscrit une étude de la façon dont la représentation de la masculinité au théâtre—ici, de personnages masculins interprétés par une jeune fille—aurait provoqué un débat et entraîné la création d’autres représentations de la masculinité dans deux contextes coloniaux très différents.

1 On July 30, 1841, readers of the Newfoundland Ledger learned that Miss Jean Margaret Davenport, the “First Juvenile Actress of the Day,” would be making a brief visit to St. John’s before returning home to England. The announcement, likely written by Davenport’s manager/father Thomas, took pains to remind readers of the actress’s many international successes:

The subtext was clear: the forthcoming arrival of the “juvenile actress” would transform Newfoundland from a lonely island colony into a privileged member of an imagined community bound by imperial and affective ties. Through an explicit reference to the recently deceased Romantic actor Edmund Kean and an implicit promise that Davenport’s presence would unite the people of St. John’s with audiences in London, New York, and the West Indies, the announcement appealed to colonial desires for cultural achievement and cosmopolitan affiliation.

2 This essay examines how and in what way the movement of child performers along global theatrical circuits in the mid-nineteenth century served British imperial interests and aroused debate about colonial identity. In recent years literary and cultural historians have examined how British children were trained to behave and view themselves as imperial subjects during the Victorian era (Norica; Goodwin; Robb; Morrison). Yet while there has been a surge of scholarship on child performers in the last decade (Bernstein; J. Davis; Gubar; Varty), few studies have examined the extent to which the lengthy world tours undertaken by the most celebrated “Infant Phenomena” affirmed British cultural values and supported colonial hierarchies. 2 Following the lead of International Relations scholar Alison M.S. Watson, I argue that looking at children as “a site of knowledge” and instruments of culture may offer new insights into the workings of empire (239). As advances in steamship travel and the expansion of intercontinental railways made it economically feasible for British performers to undertake extensive tours of the colonies, cute, talented, and emotionally-engaging children like Jean Davenport became ambassadors of British culture, affective laborers who encouraged colonial audiences to see themselves as part of the Empire’s “imagined community” (Anderson). 3

3 For the most part, Jean Davenport benefited from her role in the performance and promotion of British hegemony; audiences in North America and the Caribbean were eager to see the child prodigy take on challenging roles from a theatrical repertoire increasingly marked as “English” (Klett 23). Critics praised her convincing portrayals of comic and tragic roles ranging from Juliet to Richard III and frequently drew comparisons to the celebrated Edmund Kean. But not all colonial subjects were receptive to the instrumentalization of small children for imperial objectives. Some outright refused to be coerced by the loudly proclaimed charms of “astonishing” children and accused their promoters of trying to dupe colonial audiences with clever words and other forms of puffery.

4 To explore these tensions, I look at two politically charged controversies that erupted in response to Jean Davenport: the first in the island colony of Jamaica in September 1840, the second in the island colony of Newfoundland in August 1841. In both locations, colonial theatres and newspapers became the staging ground for heated debates about the actress’s proclaimed virtuosity, notably her portrayal of male characters and her supposed resemblance to Edmund Kean. These debates quickly extended beyond a consideration of Davenport’s acting abilities, however, to include discussions about the responsibilities of theatre audiences and critics, definitions of gentlemanly behaviour, and the relationship between settler-colonists and strangers from the metropole. Central to my analysis of the controversy surrounding Jean Davenport’s appearances in Jamaica and Newfoundland, then, is a consideration of how theatrical representations of masculinity—in this case, male characters played by a young girl—provoked discussion of, and gave rise to, other performances of masculinity in two very different colonial settings.

5 In White Civility, his study of white masculinity in nineteenth and early twentieth-century Canada, Daniel Coleman argues that for many settler-colonists, demonstrations of “cultivated, polite behaviour (most commonly modelled on the figure of the bourgeois gentleman)” were key to individual and collective performances of self. Derived largely from British models, civility was a critical component in the “production and education of the individual citizen” (10), yet was not something that an individual or culture could inherently claim; rather civility was “something that person or culture did” (12, emphasis in original). In other words, civility arose through performative acts and constituted a kind of “white cultural practice,” 4 functioning simultaneously as “a mode of internal management and self-definition” that allowed individuals to monitor their own behaviour and as a “mode of external management” that equipped settler-colonists with a rubric or “mandate” for assessing the behaviour of “those perceived as uncivil” (12-13). Policing the borders of civility was particularly important for settler-colonists who feared that geographic and social distance from the metropole would negatively influence their own social performances. “[C]aught in the time-space delay between the metropolitan place where civility is made and legislated and the colonial place where it is enacted and enforced,” settler-colonists felt the need to perform their civility as individuals and ensure that colonial society and its cultural output remained civilized (16; see also Hall 71).

6 Although the socio-political, economic, and geographic conditions shaping performances of masculinity in 1840s Jamaica differed considerably from those in 1840s Newfoundland, a comparison of critical responses to Jean Davenport shows that settler-colonists in both locations were deeply concerned with questions of civility as it related to masculinity and colonial identity. Indeed, one of the methodological advantages of tracing a theatrical performer or company’s movement from one colonial location to another is that it reveals such striking commonalities; these become even clearer when they emerge from Jean Davenport’s personal scrapbooks in newspaper articles separated by only a few pages. Set eleven months apart, the twinned debates over whether to accept the girl as a representative of British culture on par with the masculine acting of Edmund Kean illuminates the cultural significance of the child actress as a “site of knowledge” and ambassador of Empire.

7 To emphasize the complexity of Davenport’s colonial performances, I begin by situating her rise to celebrity within the broader context of nineteenth-century fascination with child prodigies, highlighting the Barnumesque interventions of her manager/father Thomas, who shaped her on- and offstage appearances. I then briefly discuss possible reasons for Davenport’s appeal to audiences on both sides of the Atlantic, including sexual titillation and her uncanny resemblance to Kean, before turning to a comparison of the controversies that arose in Jamaica and Newfoundland.

The Infant Phenomenon

8 Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Jean Margaret Davenport was one of the most successful child actresses on the British stage. As an adult, she would become the first actress in North America to play Camille, the archetypal “fallen woman,” but as a child she specialized in cross-dressed portrayals of Shakespearean villains and Romantic heroes. Davenport’s year of birth is unknown, though anecdotes from actors who worked with the family suggest that she was born in the mid-1820s, possibly as early as 1823 (McLean, “How” 133-4). Like Shirley Temple almost a century later, her childhood years were artificially extended in order to accentuate her prodigious abilities. 5 What is known is that by 1835, Jean Davenport was playing the Duke of York in Richard III and Rob Roy in a dramatic interpretation of the popular Sir Walter Scott novel; in the year that followed, her repertoire expanded to include comical male and female roles, from Sir Peter Teazle in The School for Scandal to the deliciously-named Little Pickle from The Spoiled Child (McLean 143-144; Jordan; Ford and Bickerstaff).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 Although she had yet to appear in London, Jean Davenport had graduated to full-fledged child prodigy by the fall of 1836, at least according to the publicity that surrounded her. With a flair that anticipated the promotional talents of P.T. Barnum, Thomas Davenport issued playbills characterizing his daughter as an “astonishing Juvenile Actress” who captivated audiences wherever she appeared (qtd. in McLean 146). Many of these playbills make explicit reference to earlier child stars, including Master Henry Betty, the first major child prodigy of the nineteenth century, and Clara Fisher, a child star in England and the United States in the 1820s who later trained American actress Charlotte Cushman (McLean 146; Mullenix 47-51). In fact, Thomas Davenport seems to have taken great pains to demonstrate that his daughter’s talents were just as great, if not greater than, Fisher’s. In addition to casting her in many of the same roles that Fisher had made her own—Little Pickle, Young Norval from the play Douglas, Richard III and Shylock among them 6 —, he commissioned new plays and cast her in “difficult and most arduous” parts that neither Master Betty or Clara Fisher had “[e]ver attempted” (qtd. in McLean, 146; Mullenix, 47). In The Manager’s Daughter, a metatheatrical afterpiece written especially for Jean Davenport by E. R. Lancaster (at her father’s request), the young girl delivered six rapid-fire character interpretations over the course of a fifteen-minute performance, one-upping Fisher, who had only played five characters in An Actress of All Work (Waters 81; Varty 118-124). The play further highlighted young Jean’s proclivity for masculine performance and ethnic impersonation; three of her six characters were stereotypes of male ethnicity/ nationality: the American Yankee, the Irish rogue, and the French minstrel (Varty 118; Lancaster).

10 As the title The Manager’s Daughter makes clear, Thomas Davenport was the driving force behind Jean’s celebrity. Educated as a lawyer at Dublin University—a career he later abandoned for a life on the stage—he possessed both the intelligence and the imagination to make the most of his daughter’s talents. Indeed, Davenport is widely thought to have inspired the larger-than-life character of Vincent Crummles in Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby, a connection first suggested by actor William Pleater Davidge and vehemently denied by Jean Davenport herself (McLean, “How” 133-52; Waters 78; Lander). 7 Like Vincent Crummles with the “Infant Phenomenon” Ninetta, Davenport excelled at “puffing” his daughter and played the part of doting father onstage (as the titular Manager) and off. One of his most successful strategies involved submitting editorials to local newspapers when the company was on tour. In October 1838, for example, he wrote to the Editor of the Boston Daily Advocate to address a false report that his daughter was American. “She is a Scotch Lassie—England, Ireland and Scotland bound her infant brow with laurel, with which America has entwined new wreaths,” he concluded, using the excuse of the minor correction to tout his daughter’s successes. More than free advertising, these letters gave Davenport the ideal platform for representing himself as a caring father and educated gentleman. At a time when many upstanding, middle-class men and women treated actors as social outcasts and looked upon the theatre as a site of immorality—anti-theatrical sentiment was especially strong in North America—Davenport’s public presence in the pages of local newspapers made him appear safe, familiar, and respectable.

11 Davenport also took great care in choreographing his daughter’s movements away from the theatre, deliberately juxtaposing her onstage performances of adult masculinity with meticulously staged performances of youthful femininity. As Davidge later recalled, when the company toured the British provinces, Thomas Davenport would select:

Davidge’s account indicates that much of the pleasure of watching child actresses came from observing the huge disparities—of gender, age, class, nationality—between the performers and their roles. Girl child by day, murderous king by night, Jean Davenport delighted audiences with her prodigious abilities.

12 But to what end? What does the popularity of child actresses reveal about early-nineteenth-century preoccupations? In Wearing the Breeches: Gender on the Antebellum Stage, Elizabeth Reitz Mullenix observes that while the craze for child prodigies began with Master Betty in the early 1800s, by the 1830s the North American market was dominated almost exclusively by young girls performing breeches roles. Rather than challenge gender norms, Mullenix argues, these juvenile performers gained popularity through their performative affirmation of the (apparent) relationship between childishness and femininity: “Cross-dressed actresses who played boys ultimately could not transcend their sex; their characters—like all fictional boys—lived in a theatrical Never Never Land; they would never grow up, both because the actress could not change her sex (or ‘evolve’ into a man), and because the dramatic boy was trapped within discourse” (155). Mullenix claims that in the case of Jean Davenport, it was her ability to appear simultaneously as “the perfect child and a potentially stimulating woman” in her onstage performances that made her so appealing to New York audiences on her 1838 tour. Whereas an adult woman playing male Shakespearean tragic roles threatened to undermine nineteenth century gender ideologies, the sight of a young girl “at play” was simply charming (159).

13 Anne Varty, Jim Davis, Marah Gubar, and Hazel Waters have all remarked on the erotic dynamic that often existed between child actors and adult audiences in the nineteenth century. Master Betty apparently “gratifi[ed] the female part of the audience,” with his portrayal of Richard III, a reaction that Jim Davis suggests may have arisen from the way “the implicit sexual ‘otherness’ of Richard [was] embodied and mediated through the ‘innocent’ child performer” (J. Davis 183). At a time when children were conceptualized within the Romantic imaginary as naïve, innocent, asexual, and close to nature, both Betty’s and Jean Davenport’s unexpected performances of passion may also have been strangely alluring. 8

14 Though I agree with Mullenix’s central argument about the popularity of cross-dressed girls, I want to complicate it by looking more closely at what else critics said about Jean Davenport’s performances, especially her portrayals of tragic male characters. Wherever she appeared—and she toured extensively throughout the British Empire—critics marveled at her ability to impersonate adult male behaviour and capture the emotional intensity of the characters. Commenting on her portrayal of Shylock when he “finds himself thwarted in his revenge,” a critic in Kingston, Jamaica claimed that “nothing could excel the haggard look, the horror stricken mind, depicted by Miss Davenport in the scene” (“Theatricals”). Another observed that, with the exception of Edmund Kean, the young girl’s Shylock “far surpassed those who have made it the study of their lives to excel in this great creation of the Poet.” For this writer, her depiction of Shylock’s “utter prostration, both mentally and bodily” in the trial scene and his despair upon realizing his ruin was “altogether astonishing in so young a person, and so inexperienced in those violent passions and emotions which rack so terribly the human mind” (“Theatre” 11 Sept. 1840).

15 Critics were equally impressed with Davenport’s Richard III, especially her enactment of Richard’s death and the wooing scene with Lady Anne, once again drawing comparisons to Kean (“Theatre” 8 Sept. 1840). In 1839, a writer for the Montreal Royal Gazette remarked that “It was, in truth, a surprising spectacle to behold a young girl, scarcely twelve years old, perform with credit and judgment, a character which has demanded the powers of the greatest genius that has ever attempted to depicture and realize the conception of Richard III” (“Last night”). Another writer, insisting that he was not writing “in slavish subserviency,” (i.e. as a paid puffer) described how she “looked and spoke like a Kean in miniature and displayed from her first appearance to her death by the sword of Richard, a perfect and familiar concep- tion of the crooked back tyrant” (“Miss Davenport”).

16 In remarking on her ability to capture the emotional complexity of Shakespeare’s tragic characters and other Romantic roles, these critics appear to have seen Jean Davenport as much more than a sweet, “pretty little girl” or a cute, sexualized object. 9 If their accounts are to be believed (and this, of course, is an important question given the proliferation of puff writing throughout much of the nineteenth century), Davenport excelled in expressions of “masculine” power, rage, grief, and despair, revealing an emotional depth that belied her years and gender. More than “playing at” Shylock, Rob Roy, and Richard III, as many of her juvenile contemporaries apparently did, she managed to convincingly portray the psychological turmoil of a man three or four times her age, delighting and astonishing audiences. The references to the way she bent her body into the shape of the “crooked back tyrant” Richard III or adopted Shylock’s haggard appearance further suggest that she possessed considerable physical as well as emotional skill. 10

17 The critics’ frequent comparisons between Jean Davenport and Edmund Kean, the celebrated Romantic actor best known for his feline physicality and passionate, explosive acting style, also raise challenging questions about the girl’s mimetic talents. Was her eerie “ghosting” (to use Marvin Carlson’s evocative term) of Kean’s Richard III and Shylock some kind of supernatural happenstance or a deliberate stunt arranged by her father? Intriguingly, the Davenports had more than a passing acquaintance with Kean. In an 1899 letter to the editor of the American journal Shakespeareana, Davenport explained that in 1836 her father had taken over the lease of the Richmond Theatre and the “dwelling house attached,” where Kean had died three years prior. “I was then seven years old,” she writes, “& many friends of the Kean were interested in a childish attempt to follow the Great actor & there I made my debut as a child actress” (Lander). This brief autobiographical account hints that Davenport may have been coached by Kean’s friends to imitate the actor’s characteristic style, both as entertainment and as an act of memorialization. Indeed, Davenport’s description of her acting debut recalls Joseph Roach’s discussion of “surrogation,” the process whereby a community attempts to replace—or find surrogates for—the recently deceased. In situations involving widely celebrated individuals such as Kean, “the doomed search for originals by continuously auditioning stand-ins” often results in a bizarre vacuum that pulls unexpected subjects into its vortex, in this case Jean Davenport (Roach 3, 6).

18 Thomas Davenport made the most of his daughter’s ability to conjure Kean, going so far as to claim that the actor had bestowed one of his own hats upon the young girl. As William Pleater Davidge later wrote, Davenport “impressed the public in every town he visited, with the belief that Edmund Kean had, in a burst of admiration for his daughter’s ability, presented her with what, in theatrical parlance, was called a battlefield hat” (qtd. in McLean, “How” 136). In fact, Davidge revealed, the “Kean hat” was not the original but rather a copy of the one worn by Kean, another kind of surrogate that Davenport or one of his cronies had found in the property room of the Richmond Theatre after Kean’s death and decided to put it to good use. Other records suggest that Davenport remained vague about who presented the hat to his daughter. In an 1837 announcement for a performance in Lynn, he claimed that the hat had been presented to Jean after her first appearance “before a Richmond Audience after the late Mr. Kean” (qtd. in McLean, “How” 136). For my purposes, I am less interested in whether the hat was real or fake—I expect the latter—than in the way it presumably heightened the emotional experience of watching a young girl with an uncanny resemblance to the dead actor in his most famous roles.

19 The concept of the uncanny, first discussed by German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch and later developed by Sigmund Freud, is useful for considering the affective dimension of Jean Davenport’s performances. 11 Often defined as “unfamiliar” or “unrecognized,” as a “‘peculiar kind of fear’ positioned between real terror and faint anxiety,” the notion of the uncanny describes moments when one is deeply disturbed or unsettled by an object or another human (Öztürk). “Someone to whom something uncanny happens is not quite ‘at home’ or ‘at ease’ in the situation concerned, that the thing is or at least seems to be foreign to him,” Jentsch wrote in 1906 (Jentsch qtd. in Güçbilmez 154). Judging by contemporary accounts, audiences experienced something like the uncanny when they saw Jean Davenport perform. In August 1839, a writer for the Montreal Royal Gazette described how “The various parts of Miss Davenport, were performed in a style and manner which not only elicited the admiration and applause of the audience, but excited their utmost astonishment” (“Last night”). Though cynical historians might well question the extent to which these musings echoed the actress’s advance publicity, Davenport’s lingering popularity throughout the Empire suggests that there was more than a modicum of truth in such descriptions of astonishment and surprise. Her mimetic talents unsettled audiences and raised difficult questions about talent, artistic inspiration, and the transmission of acting knowledge across gender, age, and experience.

20 Yet while many critics and audience members saw Jean Davenport as uncanny in her abilities, others saw nothing mysterious or eerie about her acting. 12 To them, she was no “phenomenon” but rather a cleverly promoted automaton trained to dance and sing before her adoring fans. In colonial settings, as the following section details, the Davenports’ dual status as strangers from the metropole and representatives of British culture only intensified such questions about Jean Davenport’s ‘uncanny’ abilities and her ghosting of Edmund Kean.

“The Insidious Attack” and the Threat of British Hegemony

21 Following a successful stint in London in 1837, the Davenports embarked on several lucrative tours of the provinces and colonies. The family first traveled to North America in the late fall of 1838 and remained on the continent for close to a year, with stops in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, New Orleans, Kingston (Upper Canada), and Montreal. 13 The tour was well-received and so in the summer of 1840, the Davenports undertook a second lengthy tour of the colonies, this time with additional stops in the Caribbean and the Maritime colonies.

22 The company was originally scheduled to perform in Kingston, Jamaica in May 1840 at the new Kingston Theatre following a month in Barbados. But when they arrived, the theatre was still under construction. As a result (according to a handwritten note in Jean Davenport’s scrapbook), the company was “compelled first to, open at Spanishtown [sic], [Jamaica]” in June. Kingston newspapers took note of the Spanish Town opening with thinly veiled envy: “The Spanistonians ought to esteem themselves as highly fortunate in having the first ‘peep;’” a writer for the Kingston Dispatch wrote, “however, we are led to hope that our Theatre will be finished, and then we shall have the pleasure of seeing this ‘wondrous little lady’s’ performances.” (“We hope the people”).

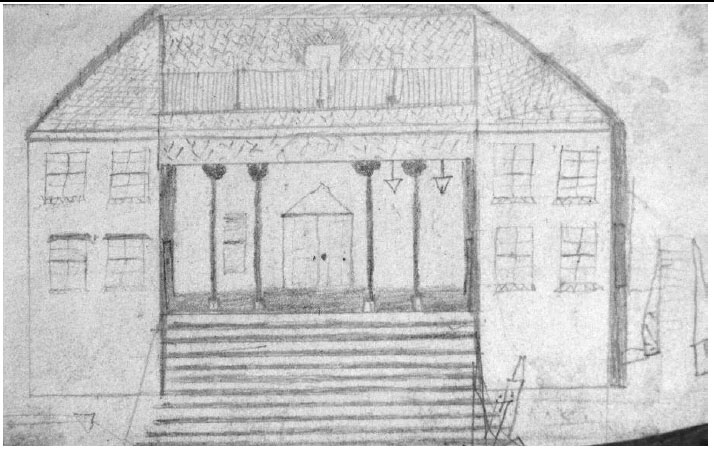

23 By late August, the Kingston Theatre was ready to open and local papers announced that Davenport would be the first actress to grace its stage (Figure 2). “It is gratifying to think, that the first impression the lovers of Drama will have, in the new Temple, will be that of this extraordinary Young Lady,” a columnist for the Dispatch remarked. “It would have been unfortunate indeed, if strollers, destitute of talent, had given the stamp of their buffoonery to the Kingston Theatre” (“We feel pleasure”). This disparaging reference to “strollers” and buffoons alludes to internal divisions within the Kingston community over who should have the honour of appearing first in the new theatre. Davenport’s scrapbook contains a brief note describing how “A cabal & ultimately riots” were “got up by a Mr. Dias & Amateurs who wish’d the [Kingston] Theatre (crush’d).” She identifies the Kingston Morning Journal as the “Organ” of the Amateurs, who were apparently outraged that a company of foreign professionals had usurped their place in the city.

24 In The Jamaican Stage, theatre historian Errol Hill identifies John T. Dias as an important figure in the Kingston theatre community throughout the 1840s and 1850s. A dentist by trade, he managed the Kingston Amateur Association and in late 1839 or early 1840 was entrusted with “serving as a building consultant and supervising both the construction and the interior arrangements” of the new Kingston Theatre (Hill 42). To Dias, as for many other citizens of Kingston, the construction of the new theatre symbolized an important turning point in the city’s history following the 1838 Emancipation of the slave population. As Hill observes, “Apart from local amateur productions, interest in the Kingston theatre had waned during the years of uncertainty preceding abolition” (40). In the Post-Emancipation period, the people of Kingston once again sought theatrical amusement, only to realize that the existing theatre was in a state beyond repair. In May 1838, a petition to build a new theatre was forwarded to the Kingston Town Council followed by public subscription to raise funds for the construction. However, Robert Hancock, the man first contracted to build the theatre, was ill equipped for the job—apparently he had never been in a theatre other than the dilapidated old one in Kingston; after his first failed attempt, Council decided that major renovations were needed to produce a functional theatre (41-2).

25 After the building fiasco, the Kingston Council tasked Dias with overseeing the theatre’s construction and raising money to cover the cost of interior decorations, a job that more appropriately suited his abilities. Nicknamed “John Kemble Macready Dias” after the famous English actor-managers John Kemble and William Charles Macready, Dias took his responsibilities seriously and reportedly viewed himself as an artist. Indeed, the reference to Dias in Davenport’s scrapbook suggests that the amateur manager was angered by the arrival of the Davenport company and the subsequent displacement of the Kingston Amateur Association. Although the new theatre opened with an amateur benefit performance in Dias’s honour, the Association was soon forced to make room for the professional Davenports (42, 86-7).

26 Jean Davenport debuted in Kingston on 6 September, making a “great sensation” with Richard III and The Manager’s Daughter. “She fully proved that she was possessed of that genius which is inherent—not acquired,” the Dispatch rhapsodized (“Theatre” 8 Sept. 1840). Others disagreed. The day after Davenport’s Kingston opening, three “bachelor” men, identifying themselves only as “Trio Voces in Uno,” wrote a letter to the editor of the Kingston Morning Journal suggesting that Jean Davenport was something of a humbug. “[L]ead not the community to expect that a ‘Theatrical Star’ has visited our shores,” they advised Thomas Davenport, “when the talent brought forward is of a medium description; rather underrate than overdraw” (“Kingston Theatre” nd). Whereas audiences elsewhere had readily accepted Thomas Davenport’s flattering characterization of his daughter, Trio Voces in Uno refused to believe the hype, particularly the comparisons to Kean: “To us who have seen Kean [and] many of the first Actors of the age per[sonify] Richard, the consequence attached to the character was entirely lost” (“Kingston Theatre”). Positioning themselves as sophisticated, culturally aware theatre-goers who had in fact seen Kean (presumably in London), the Trio pointed up the deficiencies in the actress’s performance and accused her father of purposefully deluding the people of Kingston. 14

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 227 Thomas Davenport responded swiftly, reproaching his unidentified critics for their ungentlemanly behaviour and challenging them to make themselves known. When the company’s performance of The Silent Lady was interrupted by “a respectable portion of the audience” hissing at the young actress, Davenport declared that the reaction “emanated in male violence” and demanded that the “originators” stand forth. Recalling the event in a subsequent letter to the Journal, a writer using the pseudonym “Censor” (likely a member of the Trio) described Davenport as “assum[ing] the look with which tragedy heroes terrify tyrants” to “frow[n] down the unlucky victim” (Censor). The Trio and their supporters not only refused to heed Davenport’s warning but also insisted that they were fully within their rights to hiss at a performance that displeased them (Redcap).

28 Disgusted with this behaviour, Davenport wrote to the Morning Journal representing himself as a “humble servant” intent on protecting the public from insult. “If riotous persons are not aware,” he warned, “I will tell them, that any one ‘hissing causelessly, and creating thereby a nuisance in a Theatre,’ is liable by the Law of England to be punished.” He concluded by informing the Editor that in England and America, editors of esteemed journals refused to publish “‘ANONYMOUS attacks on Managers of Theatres.” The message was clear: the absence of such civil customs in Jamaica rendered it an uncivil colony (Davenport).

29 Perhaps fearing that the controversy would escalate further, other members of the Kingston community responded. In late September, a Mr. Miller, the manager of the Kingston Theatre, ejected a man named Joseph Hyman for hissing and other disorderly conduct, while a writer in the Dispatch demanded greater civility and reason from his fellow Jamaicans (Vindix). Writing under the pseudonym “Civis,” he called upon the public to reject “ill-grounded or ungenerous animadversion” at the theatre and to instead adopt a much more supportive outlook. “The stage may be said, to be as yet, in its very infancy here,” Civis reminded readers, “and will require the fostering care of a generous and enlightened public, and an absence from invidious criticisms, ere it can be expected to attain that degree of excellence to be wished.”

30 Civis’s peacemaking comments bring to mind Daniel Coleman’s argument about the pressure to enforce civil behaviour that many nineteenth century settler-colonists felt as they tried to secure their position within evolving colonial hierarchies. Civis implies that the men of Kingston have acted childishly and, like their ‘infant’ theatre, need to overcome “invidious criticisms” (or the temptation to make them) in order to reach maturity. That the debate should centre so directly on a child actress’s ability to convincingly portray masculine behaviour suggests that the citizens of Kingston were anxious about their own performances of masculinity, particularly as they reflected Jamaica’s place within the Empire so soon after Emancipation. This “anxiety of belatedness,” to use Coleman’s phrase, was likely compounded by the actual belatedness of the new theatre’s opening and by Davenport’s impressive mimetic talents (16). Unlike other child actresses, who remained convincingly feminine in their cross-dressed performances, Davenport’s ability to capture something of Kean’s iconicity threatened to expose the performativity of gender itself and to undermine the delicate equation of masculinity with civilization.

31 I dwell at length on the controversy that erupted over the child actress in Jamaica because it bears striking similarities to the controversy that erupted in Newfoundland the following year. Despite the vast distance separating the two British colonies, tensions over local cultural practices and the threat of foreign actors representing themselves as cultural authorities led to loud accusations of ungentlemanly actions in both locations. I turn now to the Newfoundland controversy to further explore how reactions to Jean Davenport’s uncanny performances of tragic male characters provoked lengthy discussions about what constituted a gentleman.

32 On 2 August 1841, a “brilliant assemblage” gathered for Jean Davenport’s opening night performances of Richard III and The Manager’s Daughter and “testified their feelings by loud and lengthened applause” (“Miss Davenport” 4 Aug. 1841). Tickets to see the juvenile actress had sold out an hour after the performances were announced and “not a box ticket [was] to be had for “love or money” (“Theatre” 19 Aug. 1841). Davenport’s visit marked the first time an actress of such an elevated stature had appeared in St. John’s and for many colonists it signaled the city’s elevation from cultural backwater into an attractive cultural centre. Historian Patrick O’Flaherty argues that “we can date Newfoundland’s entry into the modern world from the 1840s” when the first steamships arrived in the colony (1). Yet for many citizens of St. John’s, it was the 1841 appearance of Jean Davenport that secured its membership alongside other culturally mature settler-colonies.

33 This is not to suggest that St. John’s audiences were strangers to theatrical entertainment. By the 1840s, Newfoundlanders were well accustomed to theatrical performance. As Eugene Benson and L.W. Connolly observe, “formal theatrical activity” in the form of the community concert, which featured a diverse bill of entertainment consisting mainly of songs, recitations, and playlets, was “widespread and produced in all communities throughout the island” (376). Amateur companies also staged melodramas and other popular plays for charity purposes (O’Neil 246). However, before 1841 very few professional players had traveled to the colony, certainly none as young or as celebrated as Jean Davenport; in fact, some historians maintain that Davenport was one of the first female performers to grace any stage in Newfoundland (Anspach 354).

34 Most St. John’s newspapers were unequivocal in their praise of Davenport, calling her “highly accomplished and astonishingly gifted,” “extraordinary,” and “inimitable in the extreme” (Newfoundland clippings). “Her elocution was distinct and clear, and her expression of the different passions, even in repose, highly finished,” the Ledger praised after her second performance of Shylock (“The Theatre”). But the Newfoundland Patriot was not impressed. In a lengthy editorial published two weeks after Davenport’s arrival, Patriot editor Robert J. Parsons expressed serious doubts about Davenport’s abilities, questioning whether it was possible to compare such a young girl to the likes of Kean. “[T]he press have given by far two [sic] high an estimate of the dramatic talents of this young lady,” Parsons insisted, “and have led people into the erroneous conclusion that hers is the ne plus ultra of tragic acting!...The masculine acting of a Kean in Richard the Third at Drury-lane, London, has been excelled in the little Amateur Theatre of St. John!” (Editorial).

35 Parsons refused to believe that a girl of thirteen or fourteen could possess the same skill and talent of Kean and was clearly frustrated by the apparent eagerness with which many of his fellow citizens accepted the comparison between the two. In fact, what bothered Parsons most about Davenport’s reception was that the citizens of St. John’s had “no notion of having their senses puffed away by the most outrageous descriptions of things in themselves very ordinary and common place” (Editorial). Echoing centuries of anti-theatrical writers, he implied that the charming young girl in her masculine impersonations was turning grown men into sniveling, love-struck schoolboys devoid of reason and decorum. In other words, through their association with the little girl and her vain attempts to capture masculine behaviour, these men were slipping on the great chain of civilization, becoming young, immature, and effeminate themselves.

36 As the editor of the Newfoundland Patriot, Parsons was known for his provocative statements. He had founded the paper in 1833—the same year as the establishment of the colonial legislature—as a watchdog publication that promised “terror to evil doers” (Memorial). A Liberal Protestant, Parsons sympathized with the colony’s rapidly growing Irish Catholic population—well over half of the colony’s inhabitants were Irish—and railed against those who feared Catholic “ascendancy” (O’Flaherty 15-6). In attacking Jean Davenport, then, Parsons likely aimed to ruffle his rivals’ feathers and provoke a larger debate about the effect of British cultural hegemony on the people of Newfoundland, most notably its Irish settlers.

37 Thomas Davenport’s response to Parsons’s attack was immediate and public. In an open letter published in the Newfoundland Public Ledger, he declared that as the “Father of Miss Davenport,” it was his “duty to repel the unmanly and insidious attack” upon his daughter:

Accusing Parsons of cowardice and behaviour unfitting not only a gentleman but any man, Davenport went on to question the editor’s intelligence and education, pointing out that he had misspelled the name of celebrated British actress Sarah Siddons. In his estimation, Parsons was an illiterate boor who owed his daughter an apology.

38 The rest of the Newfoundland press—six journals in total led by the Ledger and its powerful editor Henry Winton—rallied in support of Jean Davenport and her father. Winton explained that while he generally preferred to keep any correspondence to do with the Patriot out of his own publication, he had agreed to publish Davenport’s letter “for the vindication of needless and unfounded aspersions” (Winton). In the 1830s and 1840s the Ledger was the leading journal in Newfoundland, the “standard bearer’ for many of the colony’s English, Protestant conservatives and an “outspoken opponent of the Irish-dominated reform (or liberal) party” (O’Flaherty 3). Given his political perspective, then, Winton’s support of the British Davenports is hardly surprising. In his editorial, he explained to his readers that although Davenport was a stranger to the citizens of St. John’s, he wore “the outward appearance of a gentleman, and [. . .] the internal deportment of one” (Winton). Compared with Parsons’s “defiance of every principle of public and private decorum” in the Patriot, Davenport struck Winton as an upstanding gentleman fully deserving the respect and support of the St. John’s community.

39 Winton’s willingness to attest to Davenport’s gentlemanliness on the basis of his appearance is curious given the actor’s brief time in St. John’s and the nature of his profession. Like many contemporaries, Winton appears to have subscribed to the belief that an individual’s external appearance corresponded with his internal demeanor and that one could therefore judge a man by his appearance. As dissemblers by trade, actors notoriously challenged this view by assuming multiple guises and perfecting a wide repertoire; indeed, behind many of the virulent attacks against actors in the eighteenth and nineteenth century lay deep anxieties about the nature of human character. 15 Therefore, in light of the debate between Davenport and Parsons, the conservative Winton’s insistence that Thomas Davenport was what he appeared is certainly ironic. Nevertheless, in declaring his support for the Davenports and his disgust with Parsons, Winton found a convenient opportunity to show up one of his most bitter rivals.

40 But the debate over Jean Davenport was about more than personal rivalries. Implicit in the war of words over the young actress’s talent was an acute awareness of the performativity of masculinity itself, accompanied by anxiety that the male citizens of St. John’s were behaving in an uncivilized manner. At a time when the masculinity or manliness exhibited by male citizens was considered an index of a culture’s civilization, as Gail Bederman and others have shown, the ungentlemanly men of St. John’s threatened Newfoundland’s position within the imperial hierarchy by confirming stereotypes of the uncouth, savage, or effeminate colonialist. Yet the competing definitions of gentlemanly behaviour suggest that the very concepts of the gentleman and civility were themselves in flux. Robert J. Parsons accused his fellow journalists of displaying unmanly behaviour in their emotionally overwrought declarations of love for the juvenile star. Winton and Davenport rebuked him in turn for his ungentlemanly critique of the young girl, for his lack of education, and for failing to show the Davenports the courtesy and respect they deserved as strangers in St. John’s. By contrast, Winton judged Thomas Davenport an appropriate recipient for public sympathy because his performance of masculinity—presumably his appearance, education, and manners—was consistent with conceptions of gentlemanly behaviour. Rejecting the long-standing critique of actors as immoral dissemblers, Winton reassured his readers that Davenport was an honourable and trustworthy gentleman.

41 In his subsequent response to Davenport’s letter, Parsons poked fun at Winton’s testimonial to the actor’s character, cheekily suggesting that Davenport must have left his gentlemanly “outward appearance” and “internal deportment” in the “wardrobe! for certainly they are neither discoverable in the sentiment nor in the language of the letter signed ‘Thomas Davenport.’” (“Remarks”). Pursuing The Patriot’s mandate to “be a terror to evil doers,” Parsons went on to characterize Davenport as a charlatan deceiving the people of St. John’s with his puffery. “It is new to us in Newfoundland to be ‘dared’ by actors and mountebanks,” Parsons observed, before concluding: “Mr. Davenport is mistaken if he fancies that he can bully us. He shall not do that, nor shall he GULL 16 the public while we are cognizant of the fact” (“Remarks”). He went on to point out that, contrary to the Davenports’ glowing press, the people of Halifax had been less than impressed with the juvenile actress’s talents. If Davenport thought that he could count on Newfoundland’s geographic isolation to fool its people, he was simply wrong (“Remarks”). Firm in his belief that the citizens of St. John’s were being duped, taken for their apparent lack of exposure to art and culture, Parsons countered Davenport’s accusations of ungentlemanly behaviour by presenting himself as a guardian of the community, a rational gentleman unwilling to be puffed. 17

42 This strand of Parsons’s argument echoes the concerns articulated by the Trio Voces in Uno, namely that the Davenports viewed colonial audiences as culturally inferior, uncivilized dupes who could be easily fooled by childishly feminine imitations of Edmund Kean. Ironically, though, in condemning Thomas Davenport and his daughter as cultural colonialists, both Parsons and the Trio affirmed London’s importance as the imperial capital—the centre of culture, masculinity, and civilization—and revealed their dependency on that capital for their own performances of masculinity. 18 Already anxious about their place within the imperial hierarchy, these men were understandably outraged by their fellow colonists’ acceptance of Jean Davenport’s portrayals of Shakespeare’s tragic men, for it implied that they were everything she was: juvenile, feminine dissemblers stuck on a much lower strand of humanity’s great chain of being.

43 Controversy and public debate continued to dog the Davenports throughout their time in Newfoundland. After a forced retreat to Conception Bay and Harbour Grace in September 1841 when a family living in an apartment in the Amateur Theatre became ill, the company returned to St. John’s in October for what Thomas Davenport hoped would be a final triumphant performance. What resulted was a struggle over the reopening of the Amateur Theatre; Davenport insisted that he had a right to resume his engagement in the theatre for a sold-out farewell performance but Mr. Richard Clapp, secretary of the theatre, refused to grant his request. This time, none other than Patriot editor Robert J. Parsons came to the Davenports’ defense. “Whatever may be our expressed views of Theatrical performances,” he wrote, “we cannot but characterize the proceedings of this “respectable” clique as the most dishonourable…—it is not only dishonourable and uncourteous to Mr. Davenport and his family, but it has the effect of diminishing his character and reputation in the eyes of the public who may be ignorant of the true state of the case.” Parsons went on to berate his fellow journalists for remaining silent on the issue and for failing to come to the “defense of a friend thus treated and the female uncourteously assailed” (Parsons). Ironically, the man accused by Thomas Davenport for failing to perform civility offered an olive branch to the theatre manager, which he in turn used to continue berating his fellow citizens for failing, once again, to behave like gentleman. The Davenports went home, the settler-colonists continued to pursue a coherent identity…with mixed results.

44 The controversies that surrounded Jean Davenport in Jamaica and Newfoundland attest to the affective power of the child performer positioned as an ambassador of British culture. For some settler-colonists, the child’s arrival signaled the colony’s metaphorical enfolding within imperial culture, a maternal embrace that tightened affective bonds across the Atlantic and supported colonial performances of civility. To applaud Jean Davenport was therefore to mark one’s membership in a global community bounded by Empire. For others, however, the precocious child’s ability to delight colonial audiences by leaping in and out of masculine roles merely exposed the lie of colonial civility, revealing instead the vast distances separating the metropole, with its ‘authentic’ masculine culture, from the feminized mimicry of the settler colony. To these colonists, applauding Jean Davenport was tantamount to showcasing one’s failure to achieve cultural maturity and to proving oneself an unwitting fool. Far better, then, to boo and hiss than to celebrate the “Infant Phenomenon.”