Articles

Romulus and Ritual in the Beverly Swamp:

A Freemason Dreams of Theatre in Pre-confederation Ontario 1

During the 1820s and 1830s, Henry Lamb, a pioneer settler of Upper Canada (now Southern Ontario), mapped out a city called Romulus, which he intended to build in Beverly Township, a region best known for its dangerous swampland. In an advertisement calling for immigrant settlers, he promised a range of buildings, including “a first-class theatre.” This essay assesses the related documents: accounts of settlers identifying the location for un-built cathedrals; a description of an exaggerated town plan, laid out on a stump; and the newspaper advertisement. It places Lamb’s plans within the broader history of Ontario settlement, illustrated by comparison with fellow founder John Galt. The inclusion of a theatrical venue in a town plan was unusual for the time and region; there is a strong possibility that the plans for Romulus were informed by Lamb’s devotion to the secretive, and theatre-friendly, Freemasonic movement. The Freemasons were bastions of both enlightenment radicalism, and then of British imperialism; as such, they encouraged Lamb to build a prosperous life as a self-made man in a hostile environment, to dream of building a city in the wilderness—and to misjudge his intended community. Settlers at this time were more at ease with and in need of a popular performance culture, of outdoor rituals and kitchen parties, tavern songs and mechanics institute meetings, and not (or not yet) a theatre. This essay considers the plight of a man intent on the orderly, architectural administration of society in a world of improvised spaces.

Pendant les années 1820 et 1830, Henry Lamb, un des premiers colons à s’établir dans le Haut-Canada (aujourd’hui le sud de l’Ontario), a tracé la carte d’une cité modèle nommée Romulus qu’il comptait construire dans le canton de Beverly, une région reconnue pour ses marécages dangereux. Une publicité qui devait servir à attirer des immigrants désireux de s’y établir promettait la construction de tout un éventail d’édifices, dont un « théâtre de première classe ». Dans cet article, Johnson examine divers documents associés à cette annonce : des comptes rendus de colons qui indiquent le lieu prévu de cathédrales jamais construites; la description d’un plan de ville exagéré, exposé sur une souche; une annonce parue dans le journal. Il inscrit le projet de Lamb dans un contexte plus vaste, celui de l’histoire du peuplement de l’Ontario, et le compare à celui de John Galt, contemporain de Lamb. À l’époque, et dans cette région, le fait d’inclure un théâtre dans un plan de ville sortait de l’ordinaire; il n’est pas improbable que ce détail relève du dévouement de Lamb envers la franc-maçonnerie, un ordre secret qui valorisait le théâtre. Les francs-maçons ont été un bastion du radicalisme des Lumières et de l’impérialisme britannique; à ce titre, ils ont incité Lamb à prospérer par ses propres moyens dans un environnement hostile, à rêver de construire une cité dans un milieu sauvage—et à se méprendre sur sa communauté. Les colons de l’époque recherchaient encore des activités plus populaires—des rituels en plein air, des partys de cuisine, des airs entonnés à la taverne et des rassemblements de mécaniciens à la salle paroissiale—plutôt que des spectacles de théâtre. Dans cet article, Johnson examine le sort d’un homme résolu à administrer une société ordonnée et structurée dans un monde d’espaces improvisés.

Prologue: “...promised to erect a first-class theatre...” 2

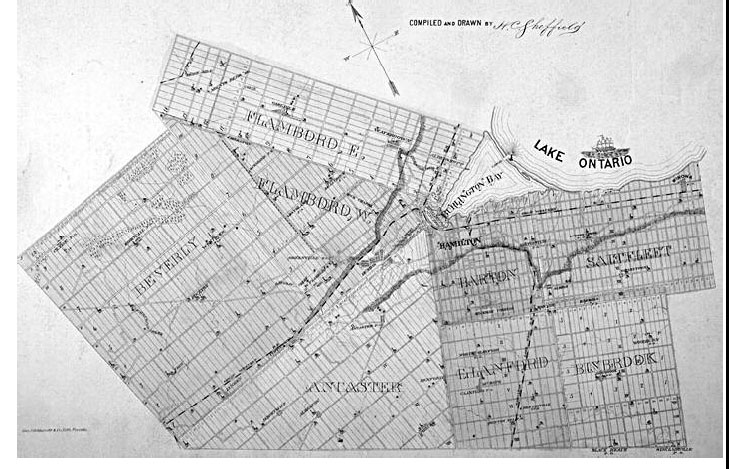

1 In the mid-1890s, the poet and local historian R. K. Kernaghan traveled the rural township of Beverly, half-way between Hamilton and Guelph in Southern Ontario, gathering local stories and legends. These included the tale of Henry Lamb, who during the early part of the nineteenth century mapped out a city he intended to build on his uncleared 2,000 acre property. According to local legend, he advertised in Britain for a ready-made immigrant population to embark on this great adventure in urban planning, which he called Romulus. Kernaghan writes:

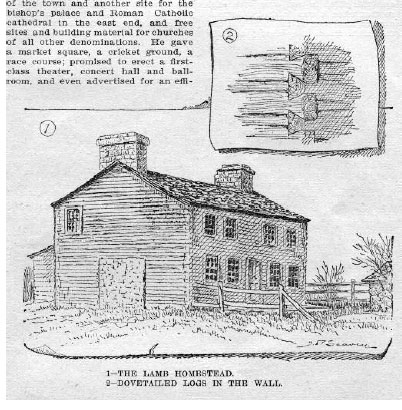

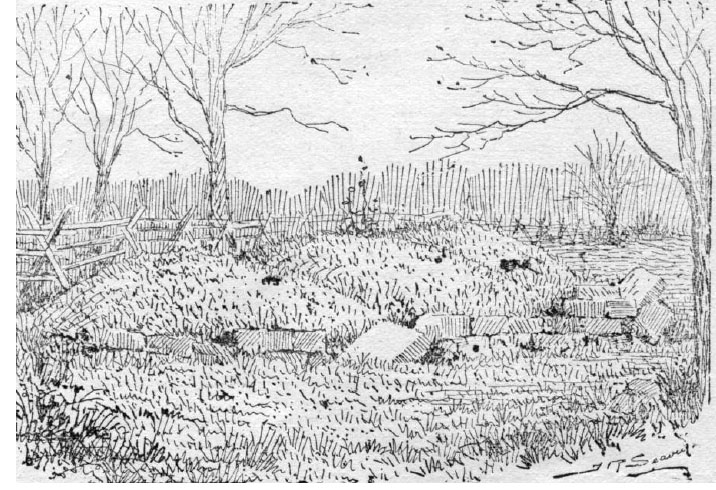

Kernaghan reports that this venture was a significant failure, and then takes readers on a tour of the ruins of Lamb’s house, tavern, and gristmill. He describes the hubris of someone who would plan such a place in Beverly—most famous for its swampland—and expresses nostalgia for a time when “there were giants” in the land (118). So fully conceived was the plan for Romulus that local residents still referred to “the site of the proposed Catholic cathedral” some seventy years later (123). Clearly Henry Lamb had left a mark on the community, though there were no architectural traces.

2 What did it mean to plan for and promise to build a “first-class theatre” in the middle of an old growth forest, in an area known primarily for its swamp, wolves, and rattlesnakes? Those two words—“first-class” and “theatre”—seem out of place in this environment, connoting a venue for professional touring performers, and a literate audience with a taste for narrative drama eager to fill a purpose-built venue. Can that have been thought possible at this time and in this place? Or did these words have a different meaning for prospective settlers in the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign? Why would the idea of building a “first class theatre” arise at all?

3 In this essay, I will first assess the documents recording this minor episode in Ontario’s history: accounts of settlers identifying the location for un-built cathedrals, written by memory into the landscape; a description of a comically exaggerated town plan, laid out on a stump, a bullet weighting it against the wind; and the newspaper advertisement quoted above, promising the impossible. The story of Henry Lamb and Romulus may seem at first to be an example of foolhardy over-reaching by an impractical dreamer. I suggest that this is a misreading of documents taken out of their original context, and that they are more trustworthy than they seem at first glance. Lamb’s scheme, indeed, is not out of place within the broader history of settlement in Ontario, illustrated in this essay by comparison with his neighbour and fellow “founder” John Galt. Admittedly, the inclusion of a theatrical venue in a town plan was unusual for the time and region; this essay will examine the prospect that the plans for Romulus were informed by Lamb’s devotion to the secretive—and theatre-friendly—freemasonic movement, first in its role as purveyor of enlightenment radicalism and social reform, and then as a bastion of British imperialism. It encouraged Lamb not only to build a prosperous life as a self-made man in a hostile environment, but also to dream of building an “enlightened” city in the wilderness. And finally, this essay will explore the prospect that freemasonry was among the reasons for Lamb’s failure as a town planner, because through it he misjudged his community—settlers more at ease with and in need of a popular performance culture, of outdoor rituals and kitchen parties, tavern songs and mechanics hall meetings, and not (or not yet) a theatre. This essay considers the plight of a man intent on the orderly, architectural administration of society in a world of improvised spaces. He arrived too soon to build his city and his theatre; but we can learn from his quixotic cause.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1“Why should he not build a city?” 3

4 Considering the primary source of information, the evidence for this city plan is surprisingly persuasive. R. M. Kernaghan, who went by the pen name “The Khan,” was a young poet who had just published his first volume through the local newspaper’s press. His writing was given to the overly rhetorical alliterative style and the mytho-symbolic substance of late-Victorian Romanticism, which found its way into this exercise in local travel writing (Bentley 18-22). “There were giants in those days,” he writes, and the “man who founded Romulus was one of them. A giant in courage, endurance and resource—he towered above his fellowmen as the great white pines of Beverly once towered above the black birches and the beeches that grew at their feet.” He “bore the brand, not of Cain, but of a loyal subject and a true man, on face and forehead. Why should he not build a city?” (Kernaghan 118). By “The Khan’s” account, Lamb was a frontier legend—a Daniel Boone of Beverly, a founding father of Upper Canada—who single-handedly cleared the land, built roads and shelter, and attracted settlers who “clustered round him.” Only the “hardships and terrors of the American revolution, the great hejira northward, the perils and dangers of the unknown woods [that] had sapped [his] strength” slowed him down, and he died before he could realize his dream city (119).

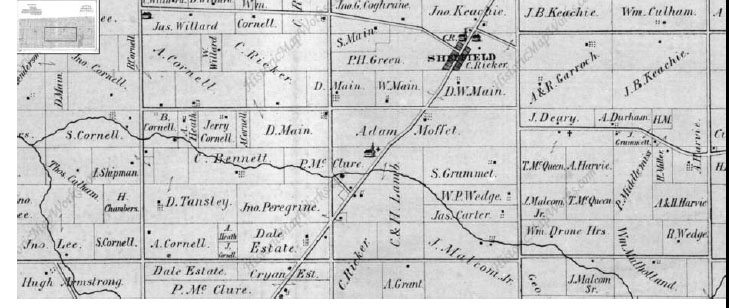

5 We should of course treat this narrative with suspicion. Documentation is missing, not least any sign of the advertisement Kernaghan describes, created to promote settlement. Nonetheless, there is circumstantial and corroborating eyewitness evidence for the story. Kernaghan was a local boy; he grew up on a farm close to the alleged site of Romulus, and was in part reporting on terrain and local lore that he knew well (Wentworth). Another work of local history, published in the late 1880s by John Cornell, includes his own reminiscences as well as letters from other, older residents. Their combined testimony suggests that there was indeed a plan for a city, and that people in the area knew about it and engaged with it imaginatively, if sometimes skeptically (Cornell 9, 12, 17, 34). And finally, local administrative records show the presence of Henry Lamb as an active citizen, acquisitive landowner, and lobbyist on behalf of this township (OA Assessment Rolls). On the basis of the evidence, a brief narrative can be constructed, which includes a plan to build a city. Here was someone whose powerful ideas carried weight in the local imagination, even when they went unrealized. Whether these plans included a “first-class theatre” is another matter.

6 Based on the evidence, here is the “story” of Henry Lamb (Kernaghan; Cornell; Bentley; Creighton, OA). He arrived in Upper Canada around 1799, of Scottish ancestry by way of Pennsylvania, a United Empire Loyalist of a later, less ideologically severe stripe. He was at first a part-time resident of the region, returning to the United States to live for part of the year while he bought and cleared land up north. He became a permanent settler in the 1810s, when he started a family on a homestead in Beverly Township (Cornell 12). 4 He was from all accounts a formidable presence in the area, someone who traded aggressively in cattle, lobbied the central authorities to build a road through the area, built a sawmill and a gristmill and, most importantly in these early days of settlement, built a large protected residence. This stockade—which will figure importantly later in this essay—was an impressive and significant presence in the region, because of its situation at the edge of the “Beverly Swamp.” Though today remembered as a small conservation area to the east of the site of the township, the Beverly Swamp was well known and “long a terror to travelers” (W. H. Smith 249) in the early nineteenth century. It covered a large territory separating the head of Lake Ontario and the rich farmland of Waterloo County, to which large numbers of German-American Mennonites were emigrating from Pennsylvania. The Swamp was a necessary rite of passage, known for its treacherous waterways, Massassagua rattlesnakes, and packs of wolves. Lamb usefully purchased land on its edge, and built what Kernaghan compared to “the rancherio of South America and the kraal of South Africa” (121), with a wooden stockade that protected domestic animals, both pigs and chickens, from the “ravenous” wildlife in the surrounding forests. This was a significant way station, where families coming from the United States and Britain (and also the German regions of Europe) could purchase fresh meat and eggs, comfortable and safe lodging, and instructions for further travel. It is possible that Lamb planned this venture, and indeed where he settled, based on knowledge of these immigration patterns.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 27 During the 1820s and 1830s, Lamb acquired a great deal of land, in local records adding up to over 1,000 acres, and in the later reminiscences to over 2,000 (OA Assessment Rolls; Wentworth; Cornell). Beverly, unlike the townships around it, had no urban centre; such acquisition argues for a settlement plan of some kind, since there would have been no means for Lamb to clear this land except with additional help from new settlers. He was, then, apparently preparing to create that “missing” town. One source, writing decades later, recalls that Lamb had a portion of his land divided up into lots for this urban development, their sale tied to the purchase of larger (100 acre) properties nearby; but, she notes, he only sold two (Cornell 34). Lamb died in 1841, and by the late 1840s almost all of the land had been sold off (OA Will, Assessment Rolls). It was subsequently cleared by individual settlers and developed as farmland with small villages springing up at crossroads (Sheffield, Rockton, etc). A “macadamized” (gravel) road was built, the swamp slowly filled in and drained, the old-growth forest cut down. Beverly Township was finally and thoroughly “civilized”—though to this day it has no town (W. H. Smith 248-9).

8 According to these later reminiscences, local residents remembered seeing two documents generated by this enterprise, which shaped the local Romulus “lore.” The first was a map of some kind, described by one older resident in the late 1880s: “...I once saw a plot of this expected city, from which radiated somewhat diverging lines to Behring Straits, Australia, Cape Cod, London, ‘Queen’s Bush,’ Patagonia, ‘Little York,’ Mt. Vesuvius, and other notable points” (Holcomb in Cornell 17). The comic absurdity of the description raises doubts about the existence of this document, but the same source goes on to describe time spent in the fields with Henry Lamb’s adult son, “he holding the plough and I driving the oxen, in breaking ground near the expected city” (17). The second document, described in detail by “The Khan,” is the (afore-mentioned) advertisement for settlers, distributed in England, which includes the promise of a theatre. 5 The comic tone of the first and the hyperbolic promises of the second are worth noting, and bear further examination in the larger context of colonial settlement.

“...the first effectual step in colonization is to plant a village...” 6

9 The “legend” of Romulus is not out of place in the more general history of settlement in Upper Canada. Despite accounts of swampland and old growth forest, the population of the entire region was growing very quickly, some towns doubling and even tripling in size in a few short years, just at the time Lamb would have been advertising for settlers (W. H. Smith 248; Wood xix). Toronto, Hamilton, and Dundas, as examples, were well placed on the water to receive settlers, and had left their “wilderness” roots behind. Such urban development notwithstanding, “settlement” could quickly turn into an impassable “bush.” Cornell notes that, though surrounding areas were better developed, in Beverly Township during the 1820s and 1830s, it could still take four days to travel a little over two miles (57). By one account, it took a month to clear one acre of land by cutting and burning (Wood 36-7); even then, the stumps remained a feature of the landscape and farmland for many years afterward. Roads, clearings, the cutting of the old growth forest, and the building of general amenities (like Lamb’s own stockade) provided an easier way into the bush for the settler. But in Upper Canada there was still a great deal of untouched land, even in the 1830s, due to government inaction and restriction: so-called “Reserve” lands were kept in abeyance by the Crown and the Clergy as a matter of speculation; and after early efforts, governments were slow in providing transportation infrastructure (Hodge 46-8; Craig 124-44; Cameron). Any successful settlement required strong-willed, entrepreneurial individuals.

10 In this context, Henry Lamb emerges as one of the individuals who led the development of the region, with little assistance and by force of will. In this he was like John Talbot in the south west of the colony, and closer to home, John Galt, the Scottish poet and novelist who came to Canada to manage the activities of the Canada Company, a British consortium that organized the settlement of the undeveloped land north and west of Beverly. Though the process of settlement differed because of the additional financial backing of a “company,” Galt’s strong personality, vision, and intervention were still essential to any possible success. He remained only three years, founded two towns at opposite ends of the lands under contract (the “Huron tract”)—Guelph and Goderich—had a falling out with the government and the investors, and returned home to write two novels and a memoir about the experience.

11 Aspects of Galt’s experience help to illuminate Lamb’s goals for Romulus. Galt strongly believed that it was important to create a so-called “planted” town in any area prior to settlement, first of all to welcome and disperse the new citizenry, and then to organize their industriousness into commercial gain. He argued the case on more than one occasion, notably in his novel Bogle Corbet, where he contrasts “planting” with the way “Americans” settled the land:

Though some vigorously defended the American way as a more “natural” evolutionary settlement, resulting in a more stable agricultural environment, Galt dismissed it out of hand; as the result of “scattering yourselves abroad in the forest,” he wrote, “you become, as it were, banished men” (66; see Hamer 106-7). The significant example of the “planted” town was Guelph, which Galt founded (according to his theory) in previously uncleared land chosen for its terrain and suitable waterway (Galt, Autobiography 60). He invented and then executed a simple tree-felling on St George’s Day as an official founding event for his “city,” in the hope of impressing “the first class of settlers” who would later arrive (54). 7 A part of the ceremony involved placing a fan on the stump of the tree to indicate the plan of the new town (Hamer 66-7). Galt laid out the town according to that plan, with radiating streets leading to a market square where produce from the newly-cleared land could be redistributed. The first building he designed and built, called “The Priory”, acted as both the Company headquarters for the entire region under its control (Guelph was at the edge of this region—a true “frontier town”), and a place where new families could stay before re-settlement to their assigned land-holdings.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 The story of Romulus echoes the story of the founding of Guelph—which was close by, and a near contemporary—in a number of ways. Kernaghan recounts how Lamb “spread his rude map of British North America out on the top of a stump and laid a two-ounce bullet on the spot” (118) where he intended to build this city, something like Guelph’s founding ritual, complete with fallen tree. He created a detailed design or “plot” (Cornell) in advance of any settlement, or even the clearing of land. His plan also included a market square, so important to Galt’s insistence on commercial development through good city “planting.” Lamb even had a “Priory” of sorts with his stockade, a safe temporary respite for new settlers.

13 Indeed, the two documents remembered by those who talked and wrote about Romulus— the town plan and the advertisement—were common creations of town “planting.” The plan outlined how an urban area would be laid out, including lots for houses, streets, squares, the separation of public and private space, and the location of institutional buildings. Such plans, perhaps surprisingly, were characterized by their impractical exaggeration. David Hamer, in his excellent study of colonial urban development, New Towns in the New World, suggests that such documents were really maps of the future, created for a population and infrastructure that would not exist for many years. “In many ways,” he writes, “these plans manipulated perceptions because, being future-oriented and making little sense in the present, they forced people to ‘see’ and indeed to live in the future” (178). John Galt says the same thing with typical pragmatism: “In planning the city I had, like the lawyers in establishing their fees, an eye to futurity in the magnitude of the parts” (Galt, Autobiography 60-1). Not drawn for present needs, such plans were quite impractical, as well as a misrepresentation of what awaited a settler, should any prospective settler see them.

14 Advertising complemented these futuristic plans by indulging in a kind of “boosterism” that exaggerated future prospects and present conditions (Hamer 61, 77-8, 176-7; Cameron 153). A useful example is the literature advertising Cincinnati, reported by Frances Trollope in her classic travelogue, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832). She quotes advertisements describing the town as a “prophet’s gourd of magic growth,” a “wonder of the west” and “infant Hercules,” among other phrases, which set her up for disappointment, since the reality could not possibly live up to the hyperbolic prose (39). Such prose could, of course, be perceived as misleading, but it also invited an amused skepticism after the manner of P. T. Barnum, who coined the term “humbug” to describe an advertising lie so bold, obvious, and entertaining that the customer can acknowledge it without dismissing the attractions of the product. Settlers were not expected to believe that “Paris,” “London,” “Rome,” or “Berlin” truly awaited them in the new world, and they were unlikely to believe that the spires and streets described in the advertisements had been built. They were, however, invited to imagine what might be. This kind of “boosterism” was much parodied at the time; 8 but for those emigrating, the hyperbolic advertisement, as well as the forward-looking town plan, may have served as positive reinforcement, an imagined end result of all their hard work, and a necessary fortification against the cold reality of those first few years clearing the land. This was hyperbole with a purpose (Hamer).

15 In this context, the descriptions of Lamb’s Romulus are not out of place at all. The advertisement greatly exaggerated what any settler could possibly experience, either on arrival or for some decades afterwards; a “first-class theatre, concert hall and ballroom,” a “cricket ground, a race course,” even the “cathedrals,” might have been outrageous, but they also constituted a promise for the future. The “plot” seen by J. W. Holcomb in John Cornell’s memoir is likewise greatly exaggerated, including arrows from Romulus to destinations around the world; but this could be seen as an amusing example of Barnumesque “humbug” that encouraged exuberant confidence in the new settlement. Even the name Romulus is not much exaggerated compared with other place names scattered across North America. The peculiar specificity of these descriptions offers further evidence of their authenticity. At this time the promise of a cricket ground or a chief of police represented “cutting edge” urban planning. Cricket grounds were seldom stand-alone venues (Birley); and, more important, the metropolitan police force had only recently been created in London itself (in 1829; see Smith), the centre of the empire, and was not yet a normal part of imperial export. It has been suggested of this very precise promise in Lamb’s advertisement that the identity of the city he wanted to create in his wilderness was clear—outrageous, perhaps, but clear. He dreamed of London. 9 Though the intended tone of these documents could not survive the passage of time, by this argument, then, they were nevertheless manifestations of a forward-looking and optimistic plan of action.

“...too young for regular theatrical entertainments...” 10

16 Allowing for the common use of hyperbole in such documents, Lamb still seems to have been over-reaching in one respect. The word “theatre” does not appear in other documentation related to local Ontario town planning. John Galt was an inveterate theatregoer, a writer about the theatre, and a playwright. His plans for Guelph called for churches of all denominations, taverns, and a well-used market square, but no theatre (Galt, Autobiography 61). At a more basic level, the practical development of any settlement depended on a sawmill and a gristmill, and eventually a school. Perhaps Lamb was too idealistic, or too impractical; except that he clearly shows himself to be a pragmatic and accomplished individual. Like Galt, he called for a range of church buildings and was likely instrumental in building Beverly Township’s first (OA Assessment Rolls; correspondence). He likewise called for a market square; and though not mentioned in the plans, he was behind the establishment of a gristmill and a sawmill in Beverly, and generally seems to have been a resourceful community builder—except, apparently, with respect to Romulus (OA Assessment Rolls).

Display large image of Figure 4

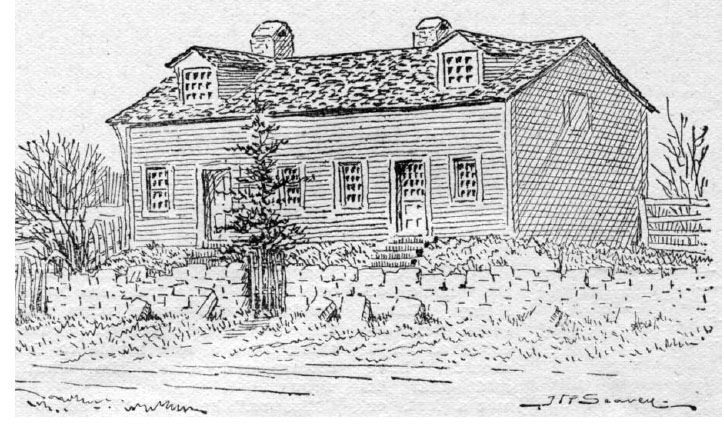

Display large image of Figure 417 Purpose-built theatrical venues were not unheard of in some regions of colonial America at this time. Odai Johnson clearly establishes that from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, settlers along the eastern seaboard felt a deep-seated need for both the building and the performances it would contain (100-20, passim). But the swamps and forests of Beverly Township were a long way from the accessible and long-settled eastern seaboard (including Halifax). Upper Canada, as described above, was poorly developed, even in comparison with neighbouring communities in upper New York State (O’Neill 4- 22; Shortt 9-30). There were no purpose-built theatrical or other performance venues in neighbouring, established towns, and contemporary writers in newspapers and journals describe a region inaccessible to traveling performances and with inadequate resources, populations, or leisure time for sustained amateur gatherings. One contemporary, writing about York, says that “The country is too young for regular theatrical entertainments, and those delicacies and refinements of luxury, which are the usual attendants of wealth” (1822)(Gourlay 250). In her survey of Toronto’s theatre during this period, Mary Shortt suggests that “the lack of entertainment [in 1834, the year Toronto was incorporated as a city] was a minor affliction compared to the lack of paved streets, a safe water supply, sanitary drainage, street lighting, garbage collection and inadequate police or fire protection” (30- 1). She quotes a letter to the editor that provides an indication of the state of the arts at the time: “neglected—nay, even condemned—the necessaries of life forming the only reward for toil; all taste being extraneous, except as it tends to produce” (Canadian Correspondent, 24 May 1834; qtd. in Shortt 31). Things changed quickly during the 1840s, with improved transportation and a rapidly increasing population; but even so, theatres were housed in buildings converted from other uses, and remained multi-purpose facilities, legal, political, religious, even agricultural. If this was the state of theatrical culture (and building) in York, what hope had Romulus? It was as if Henry Lamb was planning for a far more distant future than his contemporaries.

“...the unlettered, such as that first class of settlers were likely to be...” 11

18 It has been suggested that these hyperbolic plans and advertisements represent Lamb’s wish to attract “a better class of settler” (Creighton). If so, that intention went against other descriptions of the ideal Upper Canadian settler. Catherine Parr Traill calls for “the poor hardworking sober labourers, who have industrious habits, a large family to provide for, and a laudable horror of the workhouse and parish-overseers: this will bear them through the hardships and privations of a first settlement in the backwoods....” (146). Tiger Dunlop turns to “Mechanics and artizans of almost all descriptions—millwrights, blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, bricklayers, tailors, shoemakers, tanners, millers, and all the ordinary trades” (148). The “best” immigrants, to these writers, were the “working poor.” They clearly advise against anyone with pretensions to a sophisticated cultural education. 12 John Galt’s novel Bogle Corbet is largely about what happens when a “genteeler class of person” emigrates (208); the experiment is not a success.

19 Even if Lamb’s proposed theatre is among the structures planned for the far future, when Romulus is finally completed and with a population sufficient to support it, the fact is that those who would most want to frequent such a venue are exactly the wrong people to clear the land and navigate the swamp. The promise of a future theatre was unlikely to have been a strong argument for emigration to Beverly Township. He was advertising too soon for a second wave of settler. Lamb’s call for buildings dedicated to public performance in his original plans for Romulus appears, then, to have been unusual, and perhaps unique.

“...they went upstairs to that secret room” 13

20 Another aspect of Lamb’s personal history helps to explain the peculiar nature of his proposal—his connection to freemasonry. This is described to colourful effect in “Legends of Romulus,” the chapter of Wentworth Landmarks that follows the description of Lamb’s city plan. “The Khan” recounts how Lamb had a room on the second storey of his stockaded log house that was reserved for him alone, with a padlock on the door. Men regularly appeared at the gate and were taken in by Lamb, up to the room, where they would disappear for hours:

When they came out, “Lamb at their head,” they “would come down stairs and eat and eat and eat, and drink and drink and drink just like common folks” (122). They were treated as honoured guests, stayed the night, and moved on. Some of these men were known to local residents (including a regional judge) but many were strangers. When Lamb died, a group of these men went into the upper room (the fact that they had a key to the padlock is of interest) and stripped it bare. Though he revels in the mystery, “The Khan” concludes that Henry Lamb was a freemason, who housed a lodge in his log home.

21 The Order of Freemasons was a secret fraternal society with roots purportedly extending back to the building of Solomon’s temple and the pyramids. In fact it developed during the early eighteenth century, probably out of an older still-extant stonemason guild. The idea of the guild, its exclusivity, “secret” knowledge of skills, and sense of special status and authority—the stonemasons were the builders of castles and of cities, in effect the engineers of their day—were adapted by a broader population into a fraternal and philosophical society. A hybrid institution, the Order looked at once to the future in a utopian manner influenced by Enlightenment rationalism and to a past that involved traditions of alchemy and mysticism, including elaborate initiation rituals that charted members’ advancement through “degrees” of knowledge. Although it retained common characteristics, the movement was “malleable” (Dumenil 54), changing with time and geography, adapting to the prejudices and needs of the local population. It could be a radical enclave vilified by the status quo: in pre-revolutionary Paris, freemasons were arrested because they encouraged the society of aristocrats and servants, and had elections. Or it could be an instrument of hegemony: in the nineteenth century, the Order became a significant tool in the dissemination of British “values” across the burgeoning empire. The movement’s written tenets welcomed all religions, races, and national and cultural groups; and yet, depending on time and place, lodges maintained exclusivity according to local prejudice. Despite or because of these conflicting characterizations, freemasonry became ubiquitous throughout Europe and North America, and a kind of international cultural phenomenon, where it held no small influence because its membership included successful capitalists, landowners and aristocracy, as well as upwardly mobile artisans (Jacob; Bullock; Carnes; Dumenil).

22 There were many Masonic lodges in Upper Canada, primarily founded and populated by United Empire Loyalists. Prior to a mid-nineteenth century movement to reform, consolidate, and centralize ritual practices, freemasons often met in bars, where drink was involved (hence the epithet “merry masons”), songs were sung, and rituals were carried out (Robertson; Whence Come We). 14 What Kernaghan described was almost certainly a lodge, though no written record of it exists. The name “Henry Lamb” is listed in the log books for a lodge in Toronto in 1799, where he earned the standard three Masonic degrees (or ranks) over the course of a month (Robertson 330-1). 15 In 1803 he is again listed as “unworthy” of inclusion in the lodge for reasons unknown, though it may have been because he was not a resident or in regular attendance, or had not paid his dues (331). There were certainly lodges relatively close to Beverly Township, in Barton (Hamilton) and West Flamborough. 16 The absence of further records of Lamb’s Masonic activities or lodge is not unusual; there were many informal lodges in existence, created ad hoc or in contravention of central authorities. It was, after all, a secret society.

23 Kernaghan’s description of Lamb’s Masonic cohort illustrates the character of this secret subculture in nineteenth-century Upper Canada. They were much better educated than the typical first settler to this region, and in many cases they were not settlers themselves, but passing through. They were not only capable of long rote recitation of the classics, but also group choral work, which indicates that some had a classical education. One was a local judge, suggesting a membership with some authority and social stature, though much is made of the strangers who arrived at Lamb’s door. The assembled “brethren” retreated to a carefully secured room, which by tradition and mandate had to be separate from all non-members, never seen by “the profane” (Jacob 120). Though we cannot know the appearance of the room or the rituals performed, a typical lodge of this time would have included two pillars and a floor or wall covering emblazoned with the masons’ established symbols (the compass, square, eye). The room might have been separated into representative areas for movement during rituals, with candles for light (Curl esp. 55; Whence Come We). As a part of the meetings, all masons owned and wore aprons decorated with similarly symbolic markings. The fact that the room was padlocked, and that members cleared it out after Lamb died, speaks to a permanent and dedicated membership. Finally, there was a clear fraternal bond among these men, based on the noises from the room upstairs, the group recitation, and the convivial drinking and eating that went on after they came downstairs.

24 Many have tried to articulate the wants and needs fulfilled by membership in fraternal organizations such as freemasonry. Some mark the political nature of the movement and in particular its subversion of traditional hierarchies and championing of social mobility. Some argue for the increased freedom that resulted from its (early) religious and political tolerance. Others focus on the male fraternity of the movement, and its investment in ritual as a means for men to “take back” homosocial emotional and spiritual relationships, from a society that disallowed such fellow-feeling, that had become “feminized” (Jacob; Bullock; Carnes). Still others argue that freemasonry proved an outstanding purveyor of a homogenized culture and set of ethical and aesthetic standards on behalf of the British Empire (Harland-Jacobs). Whether these interpretations apply to Lamb’s case remains an open question. Clearing land, building a farm, a family, and a regional community all at once was time-consuming and demanding. Based on the brief description we have, Lamb appears to have spent time at his “lodge” with a group of men with whom he would otherwise not have associated, discoursing on matters (of art, culture and politics) that he otherwise would not have had the opportunity to discuss. What he talked about, and with what predisposition, cannot be known; but the act of meeting in a freemason’s lodge does have a vibrant history in the region, and some conjectures can be made.

25 First of all, though never noted in official town plans, it was not unheard of for the masonic lodge to be the first public building in a community, a result of the strong influence of military fraternities. Such buildings might include a tavern and other public and commercial spaces, as well as the lodge room. Niagara is an instructive example: founded in 1791 by the governor John Graves Simcoe (a freemason), Niagara was located close to Beverly Township, and was the seat of colonial power for some years. The town’s first building was a masonic temple, though this was not in the official town plan. The next year, when the governor opened his first parliament in the new capital, he used the lodge room for the public ceremony, making use of all the masonic furniture and trappings, the signs and symbols of the order (Harland-Jacobs 53-4). This identification could not have gone unnoticed. A government was admitting its ties to a secret, well-connected brotherhood at the heart of power in the new colony. And a secret fraternity was providing public space for new settlers to use for purposes other than its own rituals. It took authority from an imperial centre and disseminated it to those uninitiated, thus allying itself to the orderly, civilized spread of empire (Harland-Jacobs).

26 By comparison Lamb’s stockade, built no more than twenty years later, may seem rough-hewn and a long way from the centre of power; but it shared basic attributes with other early masonic venues, including the one in Niagara. A part of the building was open to the public for commercial and public use (a tavern, inn, and probably a commercial store in Lamb’s case), with one room set aside for private use. 17 The lodge members mingled in “public” before and after the meetings, and even performed in those public spaces. Their social status and good education exhibited a set of standards, of education, deportment, and sophistication. Perhaps Lamb’s call for a theatre was in fact for this kind of early multi-use public facility, inclusive of and containing, though unspoken because secret, the local masonic lodge. The fact that Lamb’s stockade was also his home complicates matters, as we shall see.

27 Lamb’s call for a theatre also follows the call of freemasonry to serve the community; there was always a strong association and mutual support between freemasonry and theatrical culture, a connection often forgotten (Johnson; Harland-Jacobs; Jacob). Masons in European and American cities attended the theatre as groups in full regalia, subsidized and sponsored theatrical groups and venues. They championed public performances often in the face of official anti-theatrical opposition. They made room in the fraternity for travelling performers, whose status was thus immediately altered in the larger community from a disreputable “vagrant” to an acceptable “traveler.” They provided venues for both travelling professional and local amateur performance, either in ad hoc conversions of commercial or domestic spaces, or rooms in their own lodges. And they themselves were inveterate performers, publicly in processions and ceremonies, and privately in their various rituals. The international character of freemasonry benefited the theatrical touring professional, and the expertise of the professional performer could be put to use by freemasonic lodges (see also Brockman; Pedicord; Burke).

28 In general, the freemasonic movement was an important part of the dissemination of theatrical culture, and had a hand more generally in the creation of public performance venues in North America. This identification of public performance space supported imperial power, seen in the example of Niagara, just as the establishment of church, school, and market reinforced the institutional structures of religion, education and commerce. If Lamb proposed his version of this kind of venue too soon, and not for the first settlers, then perhaps he was hopeful that it would all be ready for the second wave. Or perhaps he intended for his outsized Romulan plans to inspire and encourage the “lowly” pioneers surrounding him to civilize themselves into the fine specimens of imperial citizenry that would define Britain in that part of the world for the next century. Certainly they remembered where the buildings were supposed to have been.

“...unholy laughter...” 18

29 The theatre was never built and the city barely begun. I have already proposed a number of reasons for the failure of this planned community, none having to do with freemasonry. Lamb died in 1841, and his brother and two of his sons reportedly within a few years. The geography was against him; the swamp that made his services so valuable on a small and temporary scale worked against his larger project. Without the backing of a commercial enterprise like John Galt’s Canada Company, or the infrastructure provided by a forward-looking government, he had no way to provide adequate service to his settlers. To add to these troubles, there was an economic downturn in the late 1830s. His planned city seems an extreme miscalculation, for someone so capable in other respects.

30 But his freemasonic ways may also have been a factor in the failed venture. The anecdotes accumulated and recorded by Kernaghan indicate that more than fifty years after his death Lamb was still associated with freemasonry, but in a way he surely did not intend: in rumours of strange rituals, devil worship, political plots, of men up to no good. Kernaghan writes:

As a matter of record, the years before Lamb’s death were difficult ones for the brotherhood. In 1826 a group of freemasons in upper New York State were accused of murdering a man who was going to expose their rituals. Whatever the truth of the report, the incident initiated an extraordinary backlash against freemasonry across the region. In the United States, it was the catalyst for a political movement based on the belief in its conspiratorial control of government, leading to the first third-party presidential candidate in that country’s history (Bullock 277ff; Whence; Berlet). In Ontario, eighteen of twenty-six lodges stopped meeting and the general public turned against freemasonry (Whence 53). Though secret societies often stirred suspicion and reprisal, by the early nineteenth century freemasons had largely become a benign social institution involving a good deal of “convivial” public activity. And yet this is not the description that has come down to us through “The Khan,” with its expressions of fear, accusations of witchcraft, folk remedies to ward off evil. Such accounts may be attributable to the author’s purple prose, but he surely took his tone from the stories with which he grew up, told by those excluded from the freemasons—homesteaders lacking the annual fees to join, landless artisans and servants, non-British immigrants, Indigenous populations, and women. Perhaps as he plotted Romulus, Lamb was not the much-admired community leader he had been or wanted to be.

“...tripping the light fantastic toe...” 19

31 The tone of these reactions to Lamb’s freemasonry suggest that he was at odds with the surrounding community in this respect; and perhaps, in similar manner, he misjudged its immediate needs with respect to his city planning. But if Romulus, with its theatre, concert hall, ballroom, racecourse, and cricket ground, was not going to serve the cultural needs of early settlers, whether for leisure or for self-improvement, then what would? What was the performance culture surrounding Henry Lamb? To read Catherine Traill and Tiger Dunlop, the natural and primary forms of recreation for settlers in “the bush” were those of practical sportsmanship (hunting and fishing) for men, and those of the amateur naturalist for women. But these are conclusions drawn by that “genteeler class.” The settlers themselves, on the other hand, brought with them a range of activities that included a vibrant performance culture, if not (by a narrower definition) theatre. Even a cursory review of settler literature from this period in Ontario’s history frequently locates such events. These careen from the “chivaree” (Cornell 18; see also Davis-Fisch in this issue) to the “bee”—one the “rough music” of public humiliation and the other a celebratory community work party, generally held with food and drink, and “a variety of games and gymnastics” (Strickland 37). There are references to debating societies (Cornell 18) and an improvised “Mechanics institute” called “The Fool’s College,” a self-organized self-improvement society named in the spirit of self-deprecation (Kernaghan 103-4). There is reference to a local preference for fiery sermons: “a backwoods-man,” says Gerald Craig, “liked a man to preach as if he were fighting bees” (169). Taverns commonly indulged in entertainments with “two fiddles and a tambourine” (Strickland 289). And there are anecdotes of log house kitchen dances.

32 An early settler, a woman who remembered “Mayor Lamb” well, and lived very close to his property, records two winter entertainments that illustrate the nature of community, and of the use of performance as a part of that community, in the absence of the kind of purpose built institutional venues called for by Lamb. The first, at the home of a Mr. and Mrs. Roberts of “Little Scotland,” describes a concert and dance “proposed in the kitchen, the orchestra being composed of poker and tongs, tin covers and vocal music,” improvised not without danger:

This same source describes a memorable New Year’s Eve:

The narrator of these two stories describes a private space turned temporarily into a public space. This was accomplished with some difficulty (there were no musical instruments, for example) and not without danger—an injury with a hot poker, a collapsing wall, the destruction of precious objects that no doubt had been transported a long distance. She describes just how cold and dark it was to travel to and from such events, and how significant they were to the community. In all respects, these early settlers worked against the isolation into which they had moved, and in the absence of a purpose-built gathering place, they made their own private space public. The idea of a “first-class theatre” was entirely alien to this settlement.

33 The freemasonic movement did not always segregate itself from such popular performance idioms. They had often met in taverns, and had a strong public and even rowdy profile at odds with the culture of authority. “The Khan’s” description of Lamb and his freemasonic brothers descending the staircase after their rituals to join his wife for food and drink, in a venue that is all of tavern, inn, fortress, and home, resembles the house parties described above in their use of space and sense of permitted excess: they “eat and eat and eat and drink and drink and drink, just like common folks” (Kernaghan 122). This image looks backward to a more open, populist, and radical freemasonry. Over the course of Henry Lamb’s life, this freemasonry was discredited, reconstructing itself as a part of the support system for imperial expansion represented by Romulus, with its call for a “first-class theatre.”

Epilogue:

The Tombstone and the Clearing “...built his city on a rock...” 20

34 Kernaghan ends his tale of Henry Lamb with a description of his tomb:

Kernaghan creates a sense of primitive grandeur in his description of this stone cairn, and invokes the vestiges of a great civilization with his reference to Egyptian tombs. He suggests both the battle to tame and civilize “Nature” and “the Swamp,” and Man’s final defeat by the elements, in a nostalgic paean to the triumph of the wolves. Though in part this is “The Khan” indulging in the style he knew best, his interpretation of events resonates with the story of Lamb. His city plan and his freemasonic ways fought against a wilderness that he could not defeat, at best holding the beasts at bay; and just so his tomb, which, while impressive, was also built the way it was because he had “built his city on a rock,” and the land would not allow him to dig a grave.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 535 Henry Lamb’s plans for Romulus, and his promise of a theatre in Beverly Township, were part of a complex effort to confront and tame a harsh environment. It was a utopian, progressive, rational, and heavy-handed approach, ultimately interested in domination without compromise, a kind of segregation and institutionalization of space (and time, and character), all encouraged by his fraternal lodge. This can be seen as a part of, and at odds with, a much more broadly based performance culture, imported and generated by the surrounding population. These other performances constituted just as complex an effort to come to terms with that environment. They shared some ritual, vocal and theatrical characteristics with the freemasons, to be sure; but they were more improvisatory, informal, and integrative, their activities emphasizing the erasing of distinctions between public and private, interior and exterior, urban and rural, “bush” and “clearing,” men and women.