Forums

Solo Census:

A Numerical Analysis of One-Person Productions in English Canada

1 With less than 35 million people spread across a vast amount of terrain, Canada has one of the lowest population densities in the world. The nation includes an array of expansive spaces barely inhabited by people, such as the prairie steppes, maritime highlands, Arctic islands, and—at least according to ubiquitous accounts from scholars and critics—Canada’s theatrical stages. Consider the following comments:

form all its own. (Ouzounian E1)

leading theatres in increasing numbers. (Wallace 13)

that they would show a huge increase in solo-performer

theatre productions in the last ten years. (Knowles and Lane 3)

novelty, is rapidly becoming the norm. (Morrow B10)

The above quotations appear in sources dating from, in order, 2009, 2004, 1997, and 1992—a seventeen-year period that encompasses a number of artistic trends, as well as several distinct economic cycles. While the authors confidently describe solo productions as an increasingly popular component of the Canadian theatre landscape, the absence of specific evidence to support their statements prompts a number of questions. Are solo productions actually rising in number on Canada’s stages? Beyond simple numerical frequency, is the solo production form growing in artistic merit? If solo productions are, in fact, an expanding phenomenon, can a precise trajectory of years or regions be identified? In their editorial introduction to a 1997 Canadian Theatre Review issue on solo performance, Ric Knowles and Harry Lane acknowledge a lack of statistical basis for their perceptions (quoted above). This paper takes up that challenge, by first compiling a ‘solo census’ of theatre activity over the last two decades and then analyzing the results. Moreover, this paper scrutinizes the common claim that theatre companies are increasingly programming solo productions as a result of economic conditions. After a discussion of the survey results and an examination of the financial arguments, this paper briefly outlines some fertile topics for future scholarship on Canadian solo performance.

Solo Census Parameters

2 In this section, I outline the survey’s frames of reference, which I constructed not only to ensure a thorough investigation of theatre activity, but also to provide results that could be counted and compared in a reasonably consistent manner. In simplest terms, a solo production might be defined as a theatre production that includes only one person. In practice, though, basing a definition on the presence of a solitary artist is problematic, given the inherently collaborative nature of theatre; as Jenn Stephenson notes, “accompanied by musicians, assisted by a director, designers, stage manager, and crew, and always witnessed by an audience, the solo performer is enmeshed in relations with other people” (Stephenson xiii).

3 While the nebulous notion of what constitutes a solo production may provide rich discussion for scholarship, it also complicates the method of categorizing shows for this project’s solo census. As such, I established a few qualifying criteria in order to facilitate a consistent process for classifying productions. First, and most significantly, I defined a solo production as a theatre production where one human performer speaks all of the text; 1 the artist might portray one constant character, a multitude of characters, or even themselves in an autobiographical form. In addition, I expanded the definition to include productions like Billy Bishop Goes to War, where a solo actor is accompanied by one or more musicians; as well, I included productions where one human performer manipulates puppets or other inanimate objects, as in the creations of Ronnie Burkett. Though many of the shows were self-authored by the performers, I did not include this as a criterion for categorization as a solo production.

4 Validating the description of solo productions as a phenomenon requires some method of compiling and categorizing productions over a certain temporal period. As a result of our nation’s vast geographic size and diverse artistic practices, cataloguing all theatre activity in Canada would be an onerous, if not impossible, task. In an effort to construct a census with results that could be logically compared, I selected twenty English-language theatre companies and compiled a list of their theatre productions for four specific seasons: 1995-1996, 2000-2001, 2005-2006, and 2010-2011. I determined the pool of organizations by identifying the twenty members of the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres (PACT) with the largest average operating budgets over the fifteen-year span of the survey. 2 By restricting the scope of the survey to financial status, I have knowingly excluded the work of smaller companies, ad hoc productions, and Fringe Festivals—terrain where solo productions have often thrived, at least according to anecdotal accounts. For the purposes of tallying theatre productions over time, however, a focus on larger companies offers some clear advantages, most notably the existence and general accessibility of archival materials for this period. Moreover, whereas a smaller theatre organization might flourish for a brief phase of time, the sustainability of larger institutions allows for an examination of individual companies’ long-term trajectory of artistic programming. 3 All of the organizations included in this survey were in continuous operation throughout the project’s four specific seasons, with the exception of Soulpepper Theatre, which was founded in 1998 but has since grown to become one of Canada’s largest theatre companies. Additionally, despite the use of operating budgets as a filter, stark distinctions exist between the included companies. The twenty organizations span twelve cities across seven provinces. All of the companies occupy a physical home, with various rental or ownership arrangements; venue sizes range from studio theatres that seat around 100 to mainstage theatres with seating capacity for close to a thousand. A plethora of artistic mandates are represented, from companies that develop new work, to regional theatres that mostly produce iconic plays, to two companies with a focus on Theatre for Young Audiences. Thus, while this set of twenty companies in no way represents a comprehensive documentation of English-language Canadian theatre activity, it does provide a wide enough snapshot of programming decisions to draw informed conclusions about the frequency of solo productions.

5 In the listing of the twenty PACT companies with the largest average operating budgets, the following exclusions are noted, with a brief explanation in parentheses:

- Stratford Festival and Shaw Festival (repertory system of large-scale productions, with distinct financial models).

- National Arts Centre (unique funding sources and operational structure).

- commercial theatre companies like Mirvish Productions (inconsistent season structure from year to year).

- summer and/or outdoor theatre companies like Drayton Entertainment (variable season structures).

Solo Census Results, Part I

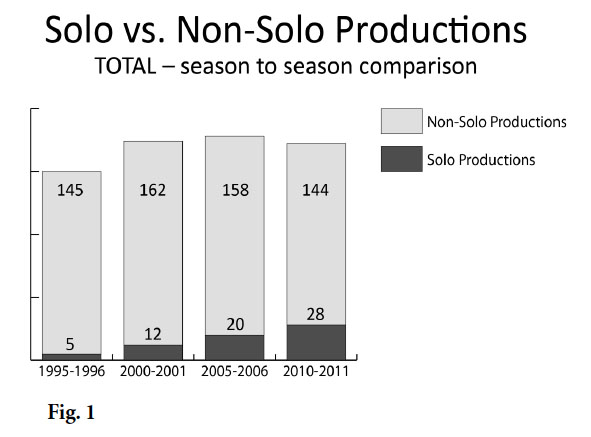

6 Methodologically, I enumerated all productions featured in the companies’ regular seasons and then categorized each one as a solo or non-solo production; I excluded additional artistic activities such as play readings or one-night performances. In the 1995-1996 season, nineteen of the theatre companies (Soulpepper did not yet exist) staged a total of 150 productions, of which only five were solo productions. Five years later, the twenty companies programmed seasons that featured 174 shows, including twelve solo productions. During the millennial season of 2000-2001, the companies mounted 178 productions, of which twenty could be categorized as solo productions. For the 2010-2011 season, the companies combined to stage 172 shows, including twenty-eight solo productions (Figure 1).

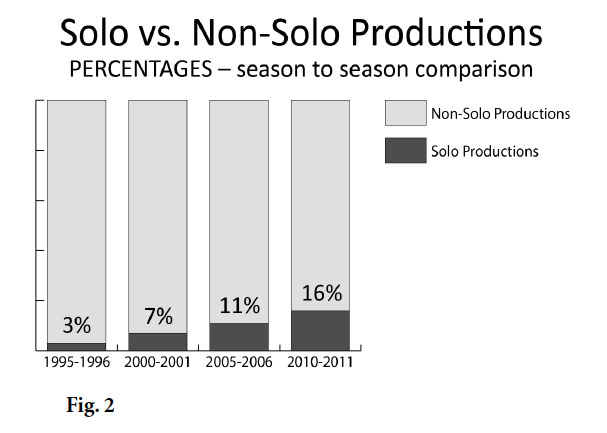

7 Given that the number of total productions fluctuated from season to season, a calculation of solo productions as a percentage of total productions provides a more stable frame for comparison. With this approach, the results are striking: solo productions in 1995-1996 accounted for a statistically insignificant 3% of the companies’ season offerings, whereas solo productions comprised 16%—approximately one in six—of the total productions in the 2010-2011 seasons (Figure 2).

8 Thus, the presence of solo productions grew steadily, in both total numbers and as a percentage of all productions, throughout each of the selected time periods. As such, this survey compellingly confirms the notion that solo productions hold an increasingly pervasive place in the contemporary Canadian theatre landscape, at least for the companies included in the project.

Solo Census Results, Part II

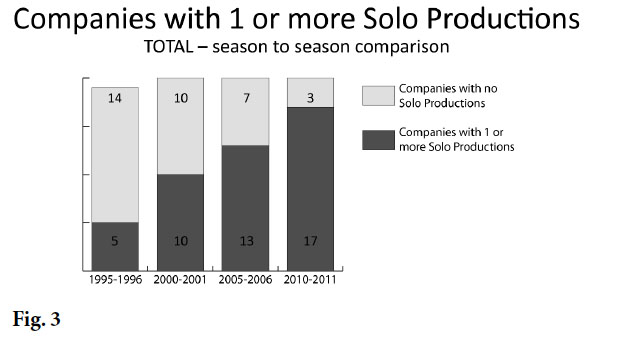

9 The above results quantifiably demonstrate the rising number of solo productions on Canadian stages. Hypothetically, though, the solo productions could have been clustered within a small number of the theatre companies, thereby limiting the notion of solo productions as a distinctly national phenomenon. An enumeration and analysis of how many theatre companies included at least one solo production in their season provides an additionally authoritative measurement of the influence of this type of show. The results of this ‘companies with one or more solo production per season’ investigation closely mirror the results of the ‘solo productions as a percentage of total productions’ comparison. In 1995-1996, only five companies included a solo production in their season. Five years later, that number doubled to ten. After steady growth to 2005- 2006, the number continued to rise for the 2010-2011 season, with seventeen of the twenty companies including at least one solo production in their season (Figure 3). Consequently, patrons who purchase subscriptions for almost any of Canada’s major theatres are apt to experience a solo production during the season. As a reminder, the cohort of twenty companies includes venues of greatly varying sizes and artistic mandates that range from Theatre for Young Audiences to regional theatres to alternative theatres.

10 This section of the survey confirms that solo productions are not only increasing in frequency across the country, but also appearing on the stages of a growing number of Canada’s theatre companies. A format that barely registered in the seasons of these organizations sixteen years ago has rapidly become a ubiquitous component of artistic programming decisions.

Additional Influence of Solo Productions

11 Beyond numerical occurrence, the influence of solo productions in Canada can also be assessed by looking at trophy cases. For instance, I surveyed the Dora Mavor Moore Awards, which recognize theatre excellence in the Toronto professional theatre community. Over the last decade, performers from fourteen solo productions have earned a Dora Award for Outstanding Performance in a Principal Role (for any of the female/male and general/independent/TYA categories). 4 The Governor General’s Literary Awards, which consider the published scripts without association to any specific theatrical productions, provide a stark contrast in terms of solo success. Since the Governor General’s Literary Awards introduced a Drama- specific category in 1981, only two solo performer plays have received that honour: Billy Bishop Goes to War (John Gray with Eric Peterson, 1982) and Fronteras Americanas (Guillermo Verdecchia, 1993). Tellingly, Daniel MacIvor, an artist famous for electric performances of his self-written solo scripts, won a Governor General’s Literary Award for his collection of non-solo scripts. Thus, solo productions lack consistent critical acclaim for their literary merit but do provide performers with vibrant opportunities to demonstrate virtuosity on stage. This distinction is particularly interesting when one considers that many of the productions that earned a Dora for outstanding performance were also written by the performers themselves. Overall, between the frequency of inclusion in theatre companies’ seasons and the rate of collecting acting awards, solo productions could reasonably be described as holding an increasingly present, and often noteworthy, place in the Canadian theatre community.

The Validity of the Economic Explanation?

12 As Jenn Stephenson notes, “the growth of solo performance in Canada has been persistently attributed to economic pressures and decreasing resources” (vii). When discussing solo productions, in both the academic world and the theatre community, people regularly rely upon economic arguments to explain the form’s growing popularity, though they infrequently present specific budgetary evidence. In the introduction to a 1994 anthology of plays in monologue form, Tony Hamill writes: “It’s been said there was a rash of one-man shows as a result of the recent recession—they were simpler and cheaper to produce” (4). With these remarks, Hamill perpetuates the notion that solo productions require less resources than multi-character productions, and are therefore more financially viable for theatre companies. Drawing upon experiences during my 2008-2012 term as the Artistic Director of Lethbridge- based New West Theatre, I can refute the myth that solo productions are consistently more affordable to create than non-solo shows. By means of context, New West Theatre was founded in 1990, is an affiliate member of PACT, and produces a broad season of artistic programming with an annual operating budget of about $600,000 (for comparison’s sake, the annual operating budgets of the twenty companies included in the census range from approximately $1.3 million to $12 million). Throughout my four seasons as AD, the company produced a series of Canadian plays in a studio theatre of 180 seats, using a fairly standard model of three rehearsal weeks and two performance weeks. A typical production in this series cost approximately $30,000; most of the expenses stemmed from expenses that remained fixed regardless of cast size, such as rehearsal venues, promotional campaigns, and ticketing fees. The difference between artist fees for a one-performer show and a two-performer show amounted to around $3500; that said, if the one-performer show involved an out-of-town artist, then the combined total for travel, accommodation, and per diem costs could easily exceed the artist fees for two local performers. In other words, producing a one- performer show usually required similar resources as a two- performer show; as such, artistic considerations—rather than economic imperatives—guided my programming decisions. Of course, a large-cast production, such as the fifteen-actor Les Belles Soeurs, would have outstripped the resources allocated for this series of Canadian plays. Thus, while economic factors might explain companies’ reliance on shows with modest cast sizes, they do not sufficiently justify the proliferation of solo productions.

13 In some contexts, a solo production could actually represent a lower-cost option for theatre companies’ seasons. Back in 1980, Bruce McDougall provided specific information related to the budgetary appeal of solo productions:

Thirty years later, the figures may have increased, but McDougall’s reasoning still holds true: a solo production could typically tour for a more affordable sum than a multi-character production. Nevertheless, such information fails to account for the fact that most of the solo productions on this project’s census were not touring works, but shows developed by the companies themselves. The tendency for companies to create productions in-house existed even when multiple companies programmed the same script in the same year. In 2010, for instance, while Saskatoon’s Persephone Theatre and Vancouver’s Arts Club Theatre co-produced a version of Billy Bishop Goes to War, the Citadel Theatre in Edmonton and Soulpepper Theatre in Toronto both created their own distinct productions.

14 Ultimately, Hamill’s comment that solo productions are “simpler and cheaper to produce” reveals a common conflation of two distinct financial issues: the amount of capital required to fund a theatre production versus the potential profitability of a theatre production. Mounting a show usually requires that a theatre company possesses the resources to cover all production costs and artists’ fees before any revenue from ticket sales is received. For smaller theatre organizations, producing a show with a large cast may very well be economically impossible, because they may lack the funds to pay multiple artists throughout the rehearsal process; this situation would be exacerbated if the company contracted professional performers affiliated with Canadian Actors’ Equity Association, due to CAEA’s strict policies requiring prepaid bonds for actors’ fees. This survey, though, examined many of the largest professional theatre organizations in Canada. Some of the major regional theatres retain financial assets in the millions; these companies could theoretically bankroll a production with one hundred performers. Even so, Canadian audiences rarely experience shows with one-hundred performers, because professional theatre companies recognize that their fiscal stability depends not simply on the costs required for theatrical production, but on their shows’ overall profitability, determined by evaluating expenses subtracted from revenues. For instance, a solo production with a modest budget could still be a financially ruinous endeavour if audiences stayed away in droves. Conversely, the spectacular Broadway production of Wicked cost an astonishing $14 million to mount in 2003, but after selling almost seven million tickets over the last decade, the New York City production has grossed more than $685 million (Broadway League). In the commercial world of Broadway, investors can risk their money on productions that might lose significant sums; the twenty theatres included in this census, on the other hand, all operate as not-for-profit organizations, which requires them to emphasize long-term sustainability in their artistic plans. They are, therefore, cognizant of the larger financial picture, which considers not only the expenses required for a production, but also the possible revenue that it might generate via ticket sales, donations, or government support.

15 Without question, financial factors influence the programming decisions of professional theatre companies in Canada, especially during times of economic uncertainty. Overall, though, the commonly circulated arguments relating to solo productions’ perceived affordability are predicated upon understandings that are at best overly simplistic, and at worst, downright erroneous.

Beyond Economics

16 If economics cannot justify the programming of solo productions, how can we rationalize the growing phenomenon that I have clearly highlighted in this survey? I suggest three ideas that might benefit from further scholarly investigation. First of all, John Gray, the primary author of iconic Billy Bishop Goes to War (original performer Eric Peterson also contributed to the script), has suggested that:

Potentially, as Louis Catron notes, solo productions offer the “sense of close sharing of the human experience, unhampered by the ornate production machinery that often distances multi-character plays from the audience;” in other words, in the absence of other actors, a solo performer develops a particularly rich relationship with spectators (109). Perhaps the current Canadian solo phenomenon follows the trajectory of traditional storytelling by placing one speaker into a personal relationship with audience members; on the other hand, perhaps an analysis of contemporary solo performance through the lens of “traditional” Canadian storytelling risks mythologizing our rural history. On a related note, the second platform for continued research relates to the prevalence of solo productions performed by members of minoritized (and other marginalized) communities; prominent recent examples include Waawaate Fobister’s Agokwe, Anusree Roy’s Pyaasa, and Nina Arsenault’s Silicone Diaries. In many cases (including all three of the examples above), the performers also created the text; through such means of self-expression, artists from marginalized communities are not only creating theatrical opportunities for themselves, but also shaping the representation of their experiences for audiences. Future research might consider the audience reception for these shows; no matter how specific the experiences reflected in a particular solo production may be, do mainstream audiences readily view the characters’ experiences as representative of an entire community? A final suggestion for extended exploration relates to contemporary technologies like blogs and YouTube, which make it possible for individuals to easily communicate their ideas and opinions, no matter how pedestrian, to a broader audience. Perhaps the popularity of personal webcams, along with the dominance of the reality television genre, has made the ‘individual confessional’ a type of entertainment aesthetic that audiences have come to embrace and expect, even on theatrical stages.

17 In conclusion, I have demonstrated through empirical data that solo productions are indeed a rising phenomenon in the Canadian theatre scene. Moreover, I have attempted to debunk the pervasive notion that financial concerns are the primary cause for the widespread popularity of solo productions on the stages of English Canada’s largest theatre companies. In search of more fruitful discussions, we should turn our attention to investigating the factors that make solo productions so compelling for contemporary audiences. As Christopher, the precocious protagonist of Doug Curtis’s Confessions of a Paperboy says, “I like being alone. What I like is having the world all to myself ” (5).